94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Food Syst. , 07 March 2025

Sec. Crop Biology and Sustainability

Volume 9 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2025.1499224

The application of exogenous heating as a physical method to improve soil quality has a significant impact on agricultural ecosystems. In this study, we conducted surface soil heating treatments at two temperatures (80 °C and 210 °C) and four time scales (2 s, 6 s, 10 s, and 15 s) using natural temperature as a control. The aim was to evaluate the multiple effects on soil nutrients, wheat growth, and microorganisms. This study mainly consisted of a pot experiment, which was conducted from October 2022 to January 2023. The loess used in the experiment was taken from degraded farmland in Baqiao District, Shaanxi, and the experiment was carried out in the core experimental area of soil organic reconstruction in Shaanxi. The results showed that compared to 210 °C treatment, soil organic matter, available potassium, and active organic carbon increased by 3.14%, 1.42%, and 5.88%, respectively, under the 80 °C treatment, altering the soil nutrient status. The combined effects of temperature and time enhanced both above-ground and root growth characteristics of wheat. The 210 °C treatment also facilitated a reduction in soil clay content. The relative abundance of Acidobacteriota and Chloroflexi generally increased across all treatments. Long-duration treatment at 80 °C significantly increased microbial richness. The clay content and available phosphorus had a substantial impact on microbial communities, with a significant negative correlation between clay content and Chloroflexi. Short-duration treatment at 210 °C significantly enhanced bacterial amino acid transport and ribosome structural function abundance. These findings suggest that exploring the application of exogenous heating methods can promote the development of green agriculture and the health of soil ecosystems.

Soil is a crucial component of the ecosystem, and factors such as its nutrient content and temperature directly affect plant growth and development and microbial activity (Balser and Wixon, 2009). In arid and semi-arid areas, soil barriers such as pathogenic bacteria, poor nutrients, and low biological activity often threaten the normal growth of wheat and other crops, bringing a series of problems to agricultural production (Lobell et al., 2011). Therefore, finding an effective soil management method to promote the green development of agriculture and activate soil nutrients has become one of the urgent problems in the current agricultural field. As an anthropogenic means, soil high-temperature treatment is widely used in the agricultural production system, which has the advantages of being environmentally friendly, sustainable, and producing no residue, and is important for the green sustainable development and healthy development of agroecosystems (Zhang et al., 2018).

Soil high temperature treatments have significant effects on soil physical, chemical, and biological properties. Soil particle structure may changed under high temperature conditions, soil porosity increases, soil aeration and permeability may be affected (Sinsabaugh et al., 2013). At the same time, the decomposition rate of organic matter in the soil may be accelerated, leading to the loss and transformation of soil nutrients. These changes directly affect soil fertility and water holding capacity, which in turn affects crop growth and development (Davidson and Janssens, 2006). Zhang et al. (2019) applied cotton stalk-based biochar into soil to study the effect of carbonization temperature on the physicochemical properties of sandy soil, and the results showed that with the increase of carbonization temperature, soil pH increased, total porosity decreased, and fluctuation of capillary porosity and field water holding capacity occurred, and both of them had the same trend. Zhou et al. (2017) studied the soil surface heating and moisture content interactions, and the results showed that moderate moisture helps to slow down the heating-induced soil drying effect and maintain the stability of soil structure. Barros et al. (2021) studied the decomposition and release process of soil organic matter by surface heating through pyrolysis experiments, and the results showed that heating can significantly affect the composition and stability of soil organic matter, and then affect the soil carbon cycle process. Ana et al. (2020) showed that soil surface heating had a significant effect on microbial activity, and that heating can affect microbial diversity and community structure in soil, with increased temperatures promoting increased abundance of heat-tolerant microorganisms, which in turn affects nutrient transformations in soil. Under high temperature conditions, crop physiological and metabolic processes may be abnormal, including photosynthesis, respiration, and other key biochemical reactions, and these physiological and metabolic abnormalities may lead to growth restriction, shortened fertility, and yield reduction (Zhang et al., 2015). Zhang (2016) showed that simulated warming increased soil respiration rate and enzyme activities in the root zone of spring wheat, and both showed highly significant exponential relationship with soil temperature. It can be seen that soil high-temperature treatments have uncertain effects on both soil properties and plant growth, and finding the right temperature and heating time becomes especially important.

Despite the fact that soil surface heating is widely used in agricultural production systems, its effects on the physical, chemical, and biological properties of soils are still a complex and worthwhile subject for in-depth research (Khan et al., 2019). With the increase in soil diseases, soil impoverishment and extreme weather events, there is an urgent need to better adapt and respond to these changes to ensure agricultural sustainability and food security (Horita et al., 2023). Therefore, this study selected loess from soil degradation areas as the research subject and employed a series of controlled surface heating treatments with varying time gradients prior to crop planting. This approach aimed to further investigate the influence mechanisms of different temperature gradients on soil properties, crop growth, and microbial communities. The results of this study can be applied to arid and semi-arid areas and areas with poor soil nutrients to solve problems such as soil diseases, poor soil, and nutrient deficiency, which is of great significance for improving agricultural productivity and soil health, especially for those agricultural production areas that need to rapidly improve soil conditions.

The loess required for the test was taken from Xiangyang Village, Baqiao District, Xi'an City, Shaanxi Province, with the geographic coordinates of 109°5′25.35″E and 34°20′37.26″N, which is in the Loess Plateau zone of China. The terrain of the region is mostly low to medium hills and plains, with mountainous and hilly terrain dominating, but there are also some plain areas. The relief has an impact on water movement and soil erosion. The region has a temperate continental climate with hot and humid summers and cold, dry winters. The average annual temperature is about 13 °C, the average annual precipitation is 620 mm, the sunshine duration is 2020 h, and the frost-free period is up to 205 d. The soil type is predominantly loess, rich in minerals but generally lacking in organic matter and nutrients, with relatively low soil fertility and a soil pH that is usually alkaline.

In this study, the collected loess was used as the test material to set up the potting test, and three heating temperature gradients were set up, respectively indoor temperature, 80 °C and 210 °C. The heating time was set up as four gradients, respectively 2 s, 6 s, 10 s, and 15 s. Three replications were made for each treatment, and a total of 27 potting treatments were set up. The study was carried out in a potting experiment, and a small potting bowl with a diameter of 10 cm and a height of 15 cm was used as the potting container. The loess was used as the test soil, which was placed in a backlit and ventilated area, dried in the shade, and then ground and sieved through a 2 mm sieve. When the pots were filled, the height of the soil was flush with the mouth of the pots, and then a thermostatic heating device (K-25A, CN) was used to heat the surface layer of each pot, and after the temperature cooled down, wheat seeds were placed in each pot in the form of hole sowing, and then the potting trays were filled with water to make them rise up by water suction until the top layer of the potting surface layer was uniformly wetted. During the growing period of wheat, ternary compound fertilizer (N-P-K=15-15-15) was applied, watered once in 30 days, and 1 g of fertilizer dissolved in 200 mL of water was weighed and used to irrigate one potted plant each time, for a total of three fertilizer applications and three irrigations. The specific experimental design is shown in Table 1.

Plant roots and rhizosphere soil samples were collected at the mature stage of wheat growth. When the root sample was collected, the large soil clods around the roots were stripped away, and the roots were then placed in water for multiple rinses. The rhizosphere soil samples were divided into three groups: one group was air-dried at room temperature for the determination of soil physical and chemical properties, one group was stored in cold storage at 4 °C for enzyme activity determination, and the other group was stored at −80 °C for DNA high-throughput sequencing analysis.

The determination of soil organic matter (SOM) involved external heating of potassium bichromate, total nitrogen (TN) was determined using the Kjeldahl method, pH was measured with a pH meter (using a soil-water ratio of 2.5:1), available phosphorus (AP) was determined through sodium bicarbonate extraction-molybdenum antimony resistance colorimetric method, and available potassium (AK) was assessed via ammonium acid ethanol extraction-flame photometer method (Manoj et al., 2020; Crepin and Johnson, 1993; Banin and Amiel, 1970). Soil readily organic carbon (ROC) was quantified using the potassium permanganate oxidation technique (Strobel et al., 2005). Soil particles were analyzed using a laser particle size analyzer (Mastersizer 3000, UK), and catalase activity was measured utilizing an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (Inoue et al., 2007; Feyissa et al., 2022).

The crops with consistent markings were consistently selected for monitoring in order to ensure the uniformity and accuracy of wheat index determination. Vernier calipers (Mitutoyo 514-106, JPN) were used to measure the plant height (WH) and leaf length (LL) of wheat, while a root scanning system (WinRHIZO, LA2400, CAN) was employed to measure various parameters including total root length (TRL), average root diameter (ARD), and total root volume (TRV) of maize roots.

Microbial community total genomic DNA extraction was conducted following the instructions of the E.Z.N.A.® soil DNA kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, U.S.). The quality of the extracted genomic DNA was evaluated using 1% agar gel electrophoresis. The concentration and purity of DNA were determined using NanoDrop2000 (Thermo Scientific, USA) (Douglas et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2016). The primers used for PCR amplification of bacterial 16S rRNA were 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′). PCR products were recovered using a 2% agarose gel and purified with the DNA gel recovery and purification Kit (PCR Cleanup Kit, China). The quantification of the purified products was done using Qubit 4.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) (Barberán et al., 2012; Edgar, 2013). Purified amplicons were pooled in equimolar amounts and paired-end sequenced on an Illumina PE300 platform (Illumina, San Diego, USA) according to the standard protocols by Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

The data statistics and analysis were processed using Excel 2019 software and plotting was done using Origin 9.0 software. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using LSD method. Soil microbial community composition was based on the data table in the tax_summary_a folder and plotted using R language tool. Diversity analysis was done using Mothur 1.30.2 software. The β diversity distance matrix was calculated using Qiime (2020.2.0), the clustering analysis was performed using the R language (version 3.3.1) for graphing and tree drawing. The NMDS (non-metric multidimensional scaling) and RDA (redundancy analysis) was performed using the vegan software package (Vsesion 2.4.3) for analysis and graphing. The correlation Heatmap analysis was performed using R (version 3.3.1) (pheatmap package). Functional predictions were made using PICRUSt2 (http://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/galaxy).

Different heating temperature and heating time promoted the increase of soil physicochemical properties. The average contents of SOM, AK, and ROC in low temperature treatment (L1-L4) were increased by 3.14%, 1.42% and 5.88%, respectively, compared with high temperature treatment (H1-H4). Compared with CK treatment, both low and high temperature treatment increased soil nutrient content. Under low temperature treatment, the average contents of SOM, TN, AP, AK, ROC, and catalase increased by 60.08%, 54.45%, 426.27%, 4.34%, 160.52%, and 6.36% compared with CK. Under high temperature treatment, the average contents of SOM, TN, AP, AK, ROC, and catalase increased by 55.24%, 53.07%, 429.78%, 2.90%, 151.78%, and 8.06% compared with CK. Under the combined treatment of temperature and time, the contents of SOM, TN, AP, and ROC were significantly increased compared with CK. SOM content in L4 and H1 was significantly increased by 33.52% and 34.29% compared with H2 (P < 0.05). ROC content of L4 was significantly increased by 32.68% compared with H2 (P < 0.05) (Table 2). It can be seen that L4 and H1 treatment was superior in improving the soil physicochemical properties.

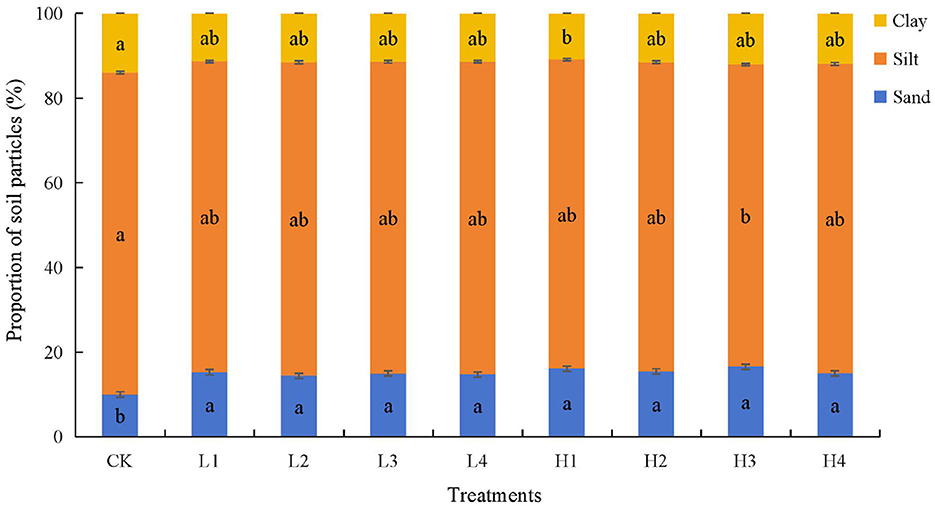

Soil particle composition changed significantly under the combined high temperature and time treatments, but the texture remained a silt loam. Sandy grain content increased significantly (P < 0.05) in all other treatments by 44.30% to 65.63% compared to the CK treatment (Figure 1). There was no significant difference in the content of both silt and clay grains under the low temperature treatment compared to the CK treatment. Under high temperature treatment, the silt content of H3 treatment was significantly reduced by 6.09% compared with CK, and the clay content of H1 treatment was significantly reduced by 18.68% compared with CK.

Figure 1. Soil particle composition under different treatments. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences between different treatment (P < 0.05).

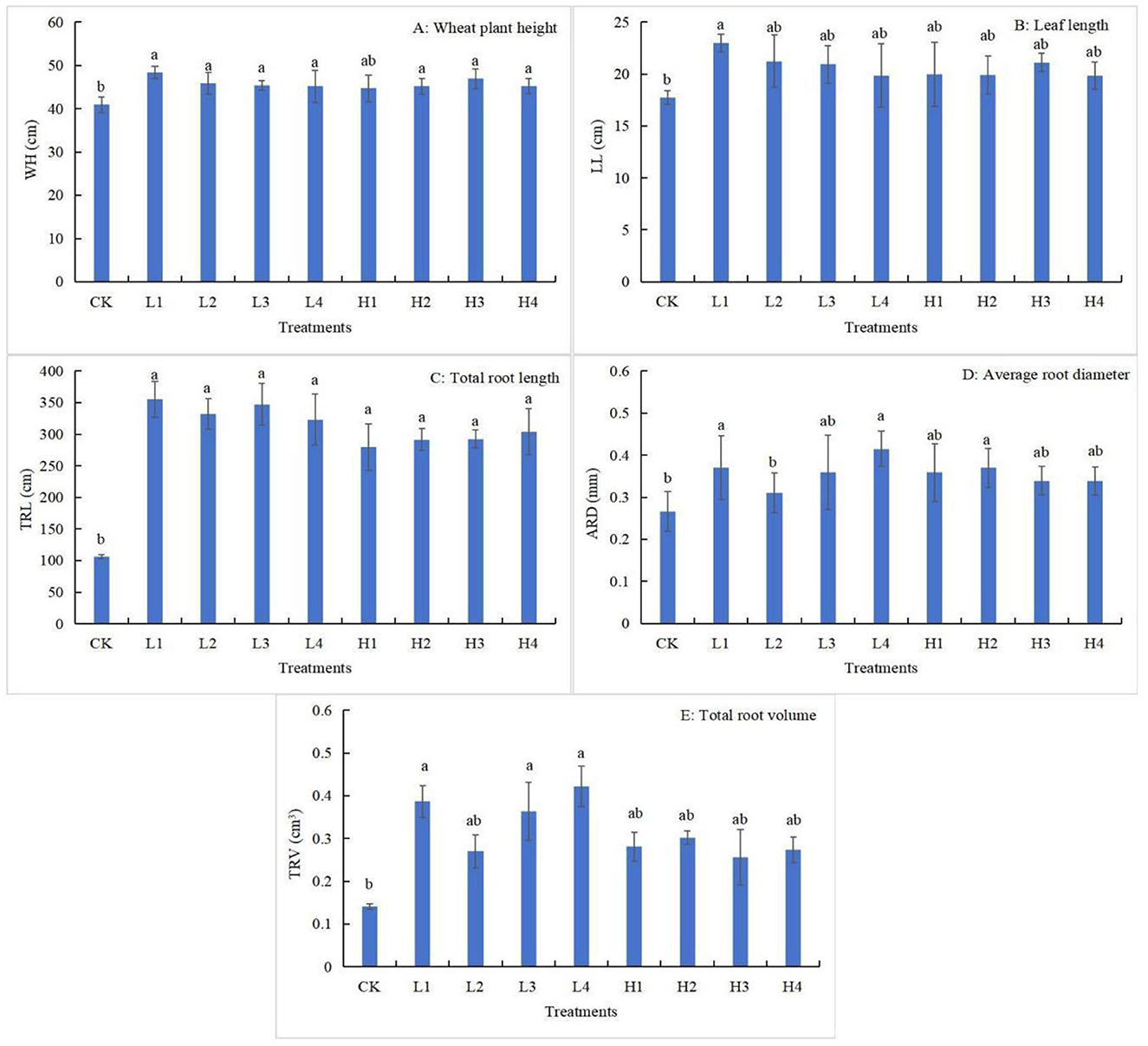

All the different temperature heating treatments increased the growth characteristics of aboveground indexes and underground root system of wheat (Figure 2). All treatments except H1 treatment significantly increased WH by 10.34% to 18.16% (P < 0.05) compared to CK treatment (Figure 2A). L1 treatment significantly increased LL by 29.70% compared to CK (Figure 2B). Low temperature treatments promoted TRL indicators better than high temperature treatments, and all treatments significantly increased the TRL values by 163.26% to 234.21% compared with CK (Figure 2C). Compared with CK, ARD indexes were significantly increased only in L1, L4 and H2 treatments, and the L4 treatment had the largest increase of 55.65% (Figure 2D). The trend of TRV changes was similar to that of TRL, which showed that the low-temperature treatments were superior to the high-temperature treatments, and the TRV values of L1, L3 and L4 treatments were significantly increased by 174.23%, 157.45%, and 199.06%, compared with that of CK (Figure 2E). It can be seen that wheat growth indexes were better under L4 treatment.

Figure 2. The changes of wheat above-ground index and root index under different treatments (A–E). Lowercase letters indicate significant differences between different treatment (P < 0.05).

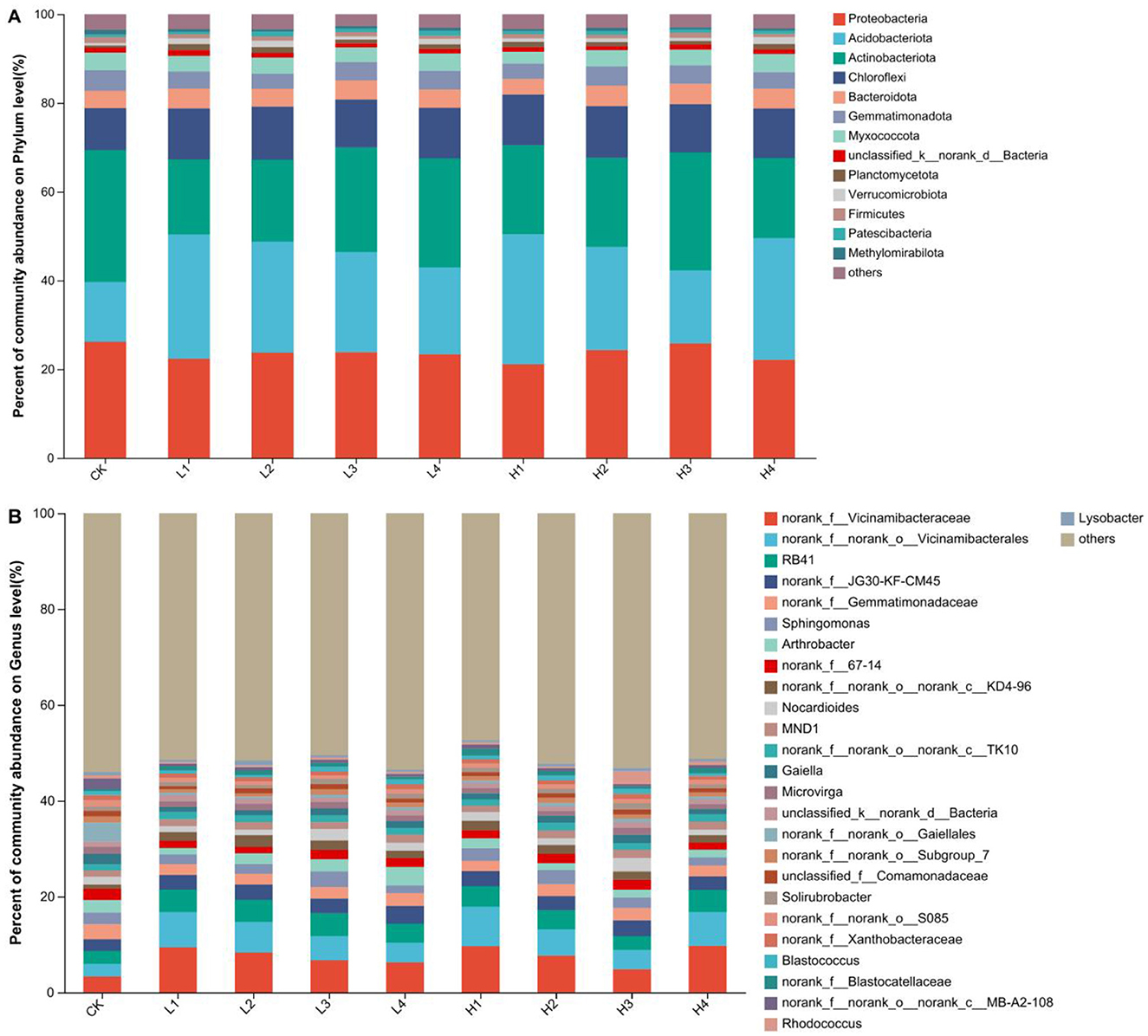

Based on the level of bacterial phylum classification, the structure of the bacterial community was basically the same in the different treatments, but the bacterial abundance varied greatly. The top five bacterial classes with high abundance were Proteobacteria, Acidobacteriota, Actinobacteriota, Chloroflexi, and Bacteroidota, which accounted for about 85% of the total bacterial community (Figure 3A). Compared with CK, the relative abundance of Proteobacteria and Actinobacteriota showed a decreasing trend under all other treatments, with the largest decreases of 19.42% and 43.19% in the H1 and L1 treatments, respectively. However, the relative abundance of Acidobacteriota and Chloroflexi showed an increasing trend, with an increase of 22.47%~118.08% and 15.59%~26.83%, respectively, compared with that of CK. The relative abundance of Bacteroidota decreased only under H1 treatment, while the abundance of other treatments increased.

Figure 3. The community composition at the level of phyla (A) and genus (B) under different treatments.

Based on the classification level of bacterial genera, there are many unnamed bacterial classes. The accumulative abundance of the top 10 species accounted for 23.54%~37.50% of the total bacterial community (Figure 3B). Compared to CK, the relative abundances of the first four species norank_f__Vicinamibacteraceae, norank_f__norank_o__Vicinamibacterales, RB41 and norank_f__JG30-KF-CM45 showed an increasing trend in all treatments. Under low temperature treatment, the abundance of the first three species decreased with the increase of heating time. The abundance of H3 treatment was lower under high temperature treatment.

There was no significant difference in the number of OTUs among different treatments. Compared with CK, the number of Sequences in all treatments except H2 was significantly increased, and the greater increase in H1 was 21.90% (P < 0.05). Coverage represents the coverage of sequencing, with values above 96%, which can cover most bacterial communities, and the sequencing data was reasonable (Table 3). Shannon and Simpsoneven represented the diversity index and evenness index, respectively, and there was no significant difference compared with CK. Ace represented the abundance index, and the Ace index was significantly increased after the temperature treatment compared with CK, and the largest increase was observed in the L4 treatment, which was 19.96%.

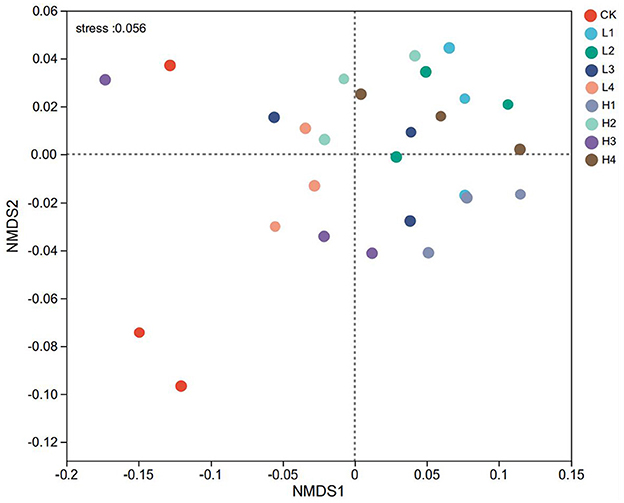

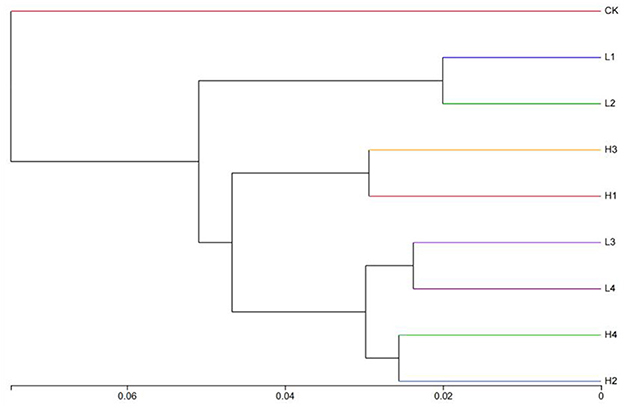

The NMDS (non-metric multidimensional scaling) analysis showed that the STRESS value was 0.056, which was < 0.1, indicating that the results had a high degree of interpretation. Overall, different temperature treatments had a significant effect on the bacterial community. The H3 treatment had a localized crossover with CK, and other treatments have no intersection with CK. Taking the position of −0.1 distance from the NMDS1 axis as the boundary, the CK was on the left side of the boundary, and the other treatments were basically on the right side (Figure 4). The results of the cluster analysis showed that when the distance was 0.04, the bacterial community could be classified into four categories, CK as one category, L1 and L2 as one category, H1 and H3 as one category, and L3, L4, H2, and H4 as one category (Figure 5).

Figure 4. The NMDS analysis of bacterial community based on phylum level. When stress < 0.1, it can be considered a good sort.

Figure 5. The cluster analysis of sample strata under different treatments. The length between the branches represents the distance between the samples, and different groups are presented in different colors.

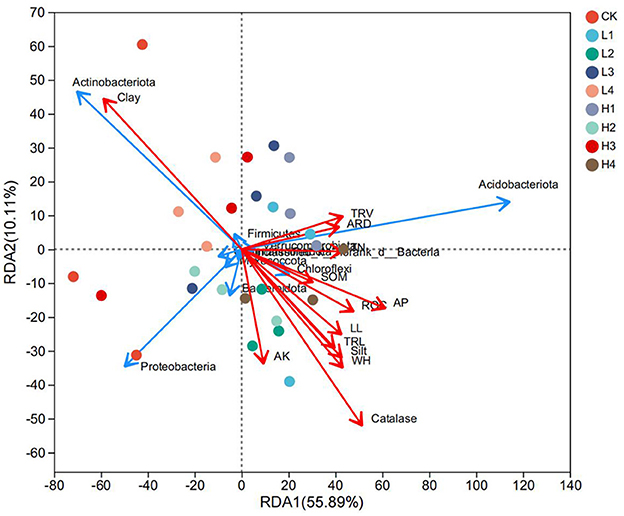

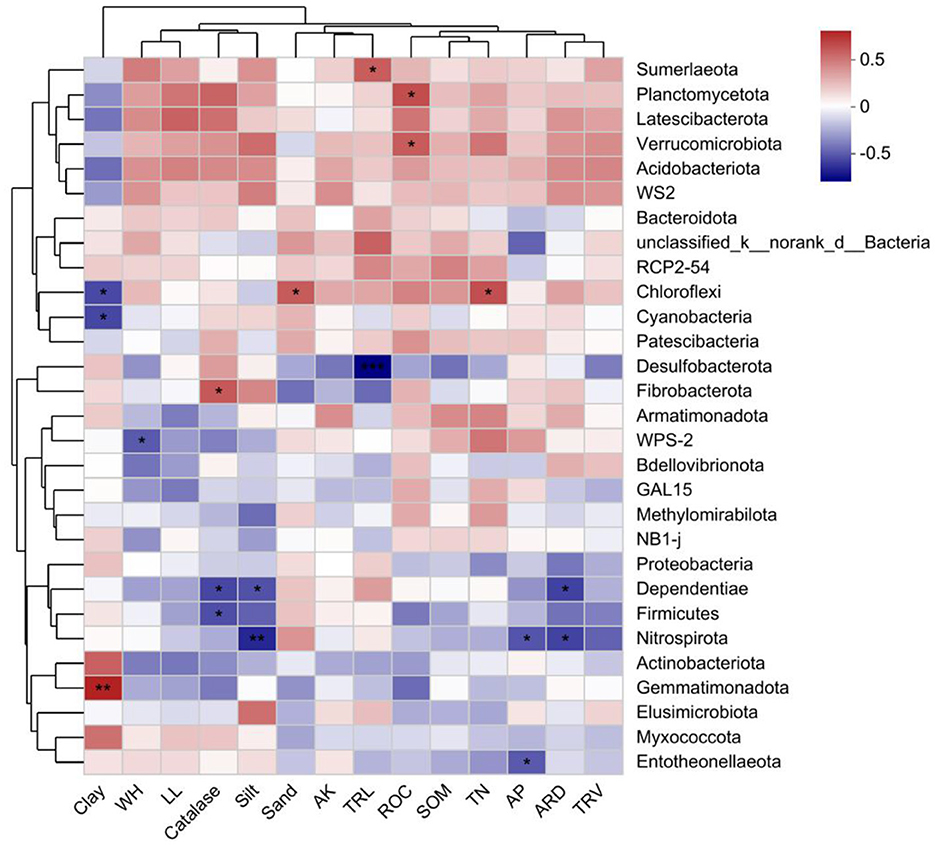

The degree of explanation for the RDA1 and RDA2 axes was 55.89% and 10.11%, respectively, and the sum of the two was 66%. The degree of influence of each environmental factor on the composition of the sample bacterial community was the greatest for clay, catalase and AP; and the least for SOM (Figure 6). Further correlation Heatmap showed that clay was highly significantly positively correlated with Gemmatimonadota (P < 0.01), and clay was significantly negatively correlated with both Chloroflexi and Cyanobacteria (P < 0.05) (Figure 7). WH was significantly negatively correlated with WPS-2. Entotheonellaeota was significantly negatively correlated with AP. Nitrospirota was significantly negatively correlated with silt, AP and ARD. Firmicutes was significantly negatively correlated with only catalase. Dependentiae was significantly negatively correlated with catalase, silt and ARD. Fibrobacterota was significantly positively correlated with catalase only. Planctomycetota and Verrucomicrobiota were both significantly positively correlated with ROC.

Figure 6. The redundancy analysis (RDA) between soil and wheat indices and bacterial communities. SOM stands for soil organic matter, TN stands for soil total nitrogen, AP stands for soil available phosphorus, AK stands for soil available potassium, ROC stands for soil readily organic carbon. WH stands for wheat plant height, LL stands for leaf length, TRL stands for total root length, ARD stands for average root diameter, and TRV stands for total root volume.

Figure 7. A correlation heatmap of soil bacteria and soil, wheat properties at the phylum level. SOM stands for soil organic matter, TN stands for soil total nitrogen, AP stands for soil available phosphorus, AK stands for soil available potassium, ROC stands for soil readily organic carbon. WH stands for wheat plant height, LL stands for leaf length, TRL stands for total root length, ARD stands for average root diameter, and TRV stands for total root volume. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

The function distribution map showed that S function (function unknown) was the most abundant at present. Moreover, in the classification of known functional gradients, functional abundance can be divided into three levels. The first was the E function (amino acid transport and metabolism) as a category with the greatest abundance among known functions. The second was J(translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis), C(energy production and conversion), M(cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis), G(carbohydrate transport and metabolism), P(inorganic ion transport and metabolism), K(transcription), L(replication, recombination and repair), O(posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones), H(coenzyme transport and metabolism), I(lipid transport and metabolism), T(signal transduction mechanisms), F(nucleotide transport and metabolism), Q(secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism), U(Intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport), V(defense mechanisms), D(cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning), and N(cell motility) as a category, showing a trend of decreasing functional abundance. The third category was B(chromatin structure and dynamics), Z(cytoskeleton), A(RNA processing and modification), and W(extracellular structures), with the smallest abundance and no significant change (Figure 8). The E function showed an increasing trend in all treatments except H2 treatment compared to CK treatment, with increases ranging from 0.04% to 1.46%, with the largest increase in H1. The J function was increased in abundance in all treatments except H3 treatment compared to CK, also H1 increased the most (Figure 9).

The short-term high-temperature heating significantly impacts the physical and chemical properties of soil. This process enhances the decomposition of SOM and the transformation of immobilized nutrients, leading to a substantial increase in the availability of phosphorus and potassium (Barros et al., 2021). Consequently, this treatment provides an ample supply of essential nutrients for plant growth. This is consistent with the research results in the literature, indicating that high-temperature treatment contributes to the release and cycling of soil nutrients (Santos et al., 2019). It is important to note that these effects vary across temperature and time conditions, highlighting the importance of optimizing these parameters to achieve the desired effect. The observed increase in sand content following temperature and time treatments indicates a shift in soil particle composition. However, the overall soil texture remained silty loam without any fundamental alteration. This is attributed to high-temperature treatment leading to the decomposition of organic matter, particularly humus, which promotes the breakdown or loss of finer particles (such as clay and silt), while relatively increasing the proportion of sand particles (Chen et al., 2023). Nonetheless, significant changes in soil texture require time for accumulation; hence, no essential modifications occur within a short period. Elevated temperatures also enhance the activity of heat-resistant microorganisms, resulting in increased nutrient availability in the soil. Consequently, this boosts microbial nutrient sources, aligning with findings by Chen et al. (2023). Previous studies have suggested that changes in soil structure constrained by nutrient availability, thereby impacting plant growth (Clemente and Thomsen, 2023; Kamei and Jun-Ichi, 2010). The sensitivity of soil physical properties to temperature change was highlighted.

The application of short-term high-temperature treatment to the soil markedly stimulated the growth of wheat. The wheat plants exhibited enhanced growth dynamics, characterized by substantial increases in WH, LL, and root development, which suggests that the enhancement of the soil environment directly improved the nutrient uptake capacity of wheat (Zhang et al., 2015). Especially in the L4 treatment, compared to CK, WH, LL, and root diameter all significantly increased, indicating that moderate heating temperature has a positive impact on the normal growth of wheat. The positive effects of surface heating treatment on wheat growth indicators may involve multiple factors. Firstly, it improved the physical and chemical properties of the soil, increased soil aeration and nutrient content, and provided a more favorable environment for the growth of wheat roots (Agboola, 1981; Hou et al., 2012). Secondly, heating treatment may affect the activity of microorganisms in the soil, promoting the transformation and provision of soil nutrients (Zhang et al., 2018). In addition, moderate temperature may stimulate plant physiological and metabolic processes, promoting normal growth of wheat (Ma et al., 2022). Compared to previous studies, these findings emphasize the multi-level effects of surface heating treatment on plant growth.

The number and community structure of soil microorganisms were significantly affected by short-term high temperature heating. Although high temperature can kill some heat-sensitive microorganisms, the overall increase of soil microorganisms was found in the experiment, which may be related to the expansion of heat-resistant microorganisms and the rich nutrient supply generated by the decomposition of organic matter (Zhu et al., 2022). Under high temperature conditions, there is no significant change in microbial diversity and evenness, while relative abundance increases. This is consistent with previous research findings, indicating that high temperature can promote the growth of heat-resistant microorganisms (Li et al., 2012). At the same time, the structure of microbial community was obviously adjusted, and the proportion of functional flora was increased, which had positive effects on soil nutrient cycling and wheat growth promotion. The increase in Acidobacteriota and Chloroflexi, both known for their role in nutrient cycling, may indicate a positive response to surface heating treatment. The positive correlation between some bacteria and soil parameters revealed by RDA analysis suggests the potential effects of these microorganisms on soil health under surface heating conditions. In addition, the increase of TN, AP, ROC and other nutrients in soil also affected the structure of microbial communities. In terms of functional prediction, The AATM (Amino acid transport and metabolism) function and TRSB (Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis) function of bacteria were significantly increased under H1 treatment. Amino acids are important organic molecules that not only participate in protein synthesis, but also play a key role in energy metabolism and signal transduction (Wang et al., 2022). The transport and metabolic functions of amino acids significantly increased under H1 treatment, which may be an adaptive response of microorganisms to high temperature stress. Due to the accelerated decomposition of organic matter in soil caused by high temperature conditions, microorganisms may require more amino acids to maintain their metabolic activity and survival (Rodrigues et al., 2017).

Although this experiment used a pot experiment to study the effects of short periods of high temperature heating on soil and crop growth, we believe that these results have some potential for field application. We have verified the effectiveness of this method under controlled conditions through pot experiments, and we plan to conduct further studies in the field to evaluate the feasibility and applicability of this method in actual agricultural production. Considering that short-term high temperature heating can significantly improve the availability of soil nutrients and promote crop growth, and does not require large-scale equipment investment, this method has good economic prospects and wide application prospects. If the effect can be further proved in the field experiment, it will provide an efficient and low-cost soil improvement scheme for farmers, which has strong popularization value. In addition, combined with modern agricultural technology, this method represents an innovation and breakthrough to the traditional soil improvement means, and helps to promote the modernization of agricultural production methods.

This study investigated the effects of surface heating at different temperatures and durations on soil-crop-microbial interactions. Low-temperature treatments significantly increased soil organic matter, available potassium, and active organic carbon, while all temperature treatments enhanced the sand particle content. Wheat growth, including plant height, leaf length, and root development, was positively affected by low-temperature treatment. Additionally, high-temperature treatments adjusted the bacterial community structure, promoting bacterial abundance and amino acid metabolism. These findings offer practical insights for soil management and agricultural production, particularly in loess regions, and contribute to soil ecosystem research globally.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=PRJNA1045834.

ZG: Data curation, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JH: Formal analysis, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. HZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Thanks to the support of outstanding talents project of Shaanxi Province “Special Support Plan for High-level Talents.”

ZG, JH, YZ, and HZ are employed by Shaanxi Provincial Land Engineering Construction Group Co., Ltd.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Agboola, A. A. (1981). The effects of different soil tillage and management practices on the physical and chemical properties of soil and maize yield in a rainforest zone of western nigeria. Agr. J. 73, 247–251. doi: 10.2134/agronj1981.00021962007300020001x

Ana, B., Alba, L., Angela, M., and Javier, C. G. (2020). Soil heating at high temperatures and different water content: effects on the soil microorganisms. Geosciences 10:355. doi: 10.3390/geosciences10090355

Balser, T. C., and Wixon, D. L. (2009). Investigating biological control over soil carbon temperature sensitivity. Global Change Biol. 15, 2935–2949. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01946.x

Banin, A., and Amiel, A. (1970). A correlative study of the chemical and physical properties of a group of natural soils of Israel. Geoderma 3, 185–198. doi: 10.1016/0016-7061(70)90018-2

Barberán, A., Bates, S. T., Casamayor, E. O., and Fierer, N. (2012). Using network analysis to explore co-occurrence patterns in soil microbial communities. ISME J. 6, 343–351. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.119

Barros, N., Rodríguez-Añon, J. A., Proupín, J., and Pérez-Cruzado, C. (2021). The effect of extreme temperatures on soil organic matter decomposition from Atlantic oak forest ecosystems. iScience 24:103527. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.103527

Chen, X. Q., Li, F., Tang, J. M., Shi, H., Xie, J., and Jiao, Y. (2023). Temperature uniformity of frozen pork with various combinations of fat and lean portions tempered in radio frequency. J. Food Eng. 344:111396. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2022.111396

Clemente, K. J., and Thomsen, M. (2023). High temperature frequently increases facilitation between aquatic foundation species: a global meta-analysis of interaction experiments between angiosperms, seaweeds and bivalves. J. Ecol. 111, 1340–1361. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.14101

Crepin, J., and Johnson, L. R. (1993). Soil sampling and methods of analysis. J. Environ. Qual. 38, 15–24. doi: 10.2134/jeq2008.0018br

Davidson, E. A., and Janssens, I. A. (2006). Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature 440, 165–173. doi: 10.1038/nature04514

Douglas, G. M., Maffei, V. J., Zaneveld, J. R., Yurgel, S. N., Brown, J. R., Taylor, C. M., et al. (2020). PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 685–688. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0548-6

Edgar, R. C. (2013). UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 10, 996–998. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604

Feyissa, A., Gurmesa, G. A., Yang, F., Long, C., Zhang, Q., and Cheng, X. (2022). Soil enzyme activity and stoichiometry in secondary grasslands along a climatic gradient of subtropical china. Sci. Total Environ. 825:54019. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154019

Horita, M., Kobara, Y., Yano, K., Hayashi, K., Nakamura, Y., Iiyama, K., et al. (2023). Comprehensive control system for ginger bacterial wilt disease based on anaerobic soil disinfestation. Agronomy 13:1791. doi: 10.3390/agronomy13071791

Hou, X. Q., Li, R., Jia, Z. K., Han, Q. F., Wang, W., and Yang, B. P. (2012). Effects of rotational tillage practices on soil properties, winter wheat yields and water-use efficiency in semi-arid areas of north-west china. Field Crop. Res. 129, 7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2011.12.021

Inoue, Y., Shimada, K., and Katayama, A. (2007). Correlation between bacteria and soil particles transported from packed river sand. P. Int. Sym. Eco. Sci. 2007, 1182–1185.

Kamei, T., and Jun-Ichi, T. (2010). Effects of high temperature curing histories on unconfined compressive strength of foamed mixture lightweight soil and its soil structure. J. JPN Soc. Eng. Geol. 47, 208–217. doi: 10.5110/jjseg.47.208

Khan, M. J., Brodie, G., Cheng, L., Liu, W., and Jhajj, R. (2019). Impact of microwave soil heating on the yield and nutritive value of rice crop. Agriculture 9:134. doi: 10.3390/agriculture9070134

Li, H. T., Xu, X. H., and Liu, J. (2012). Effect of microbiological additive on the diversity of microbial community and the dynamic distribution during high-temperature composting process. Appl. Mech. Mater. 214, 366–369. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.214.366

Liu, C. S., Zhao, D. F., Ma, W. J., Guo, Y. D., Wang, A. J., Wang, Q. L., et al. (2016). Denitrifying sulfide removal process on high-salinity wastewaters in the presence of Halomonas sp. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 100, 1421–1426. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-7039-6

Lobell, D. B., Burke, M. B., Tebaldi, C., Mastrandrea, M. D., Falcon, W. P., and Naylor, R. L. (2011). Prioritizing climate change adaptation needs for food security in 2030. Science 319, 607–610. doi: 10.1126/science.1152339

Ma, L. W., Liu, L., Lu, Y. S., Chen, L., Zhang, Z. C., Zhang, H. W., et al. (2022). When microclimates meet soil microbes: temperature controls soil microbial diversity along an elevational gradient in subtropical forests. Soil Biol. Biochem. 166:108566. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2022.108566

Manoj, S., Thirumurugan, M., and Elango, L. (2020). Determination of distribution coefficient of uranium from physical and chemical properties of soil. Chemosphere 244:125411. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125411

Rodrigues, R. R., Moon, J., Zhao, B. Y., and Williams, M. A. (2017). Microbial communities and diazotrophic activity differ in the root-zone of alamo and dacotah switchgrass feedstocks. GCB Bioenergy 9, 1057–1070. doi: 10.1111/gcbb.12396

Santos, H. O. D., Vasconcellos, R. C. C., Pauli, B. D., Pires, R. M. O., and Pinho, D. V. R. V. (2019). Effect of soil temperature in the emergence of maize seeds. J. Agr. Sci. 11, 479–484. doi: 10.5539/jas.v11n1p479

Sinsabaugh, R. L., Manzoni, S., Moorhead, D. L., and Richter, A. (2013). Carbon use efficiency of microbial communities: stoichiometry, methodology and modelling. Ecol. Lett. 16, 930–939. doi: 10.1111/ele.12113

Strobel, B. W., Borggaard, O. K., Hansen, H. C. B., Andersen, M. K., and Raulund-Rasmussen, K. (2005). Dissolved organic carbon and decreasing ph mobilize cadmium and copper in soil. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 56, 189–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2389.2004.00661.x

Wang, Z., Liu, Z. T., Hu, W., Bai, H., Ma, L. J., Lv, X. B., Zhou, Z. G., and Meng, Y. L. (2022). Crop residue return improved soil nitrogen availability by increasing amino acid and mineralization under appropriate n fertilization. Land Degrad. Dev. 33, 2197–2207. doi: 10.1002/ldr.4241

Zhang, H., Liu, Z., and Wu, T. (2015). Responses of soil microbial community structure and diversity to environmental changes in the Baixing natural reserve, China. Geoderma 245, 56–62.

Zhang, H. M., Li, K., Chen, M. G., Zhou, L., Yang, Y., and Kong, D. G. (2019). Effect of carbonization temperature on physicochemical properties of sandy soil in southern Xinjiang. Sci. Tech. Eng. 19, 123–127.

Zhang, J., Yu, Z., Zhao, Q., and Wang, J. (2018). Effects of soil temperature and moisture on soil respiration, microbial biomass, and enzyme activities in black and cinnamon soils. Ecol. Evol. 8, 8881–8890.

Zhang, P. L. (2016). Effects of simulated warming on growth and development, root zone soil respiration rate and enzyme activity of spring wheat. Henan Agr. Sci. 45, 55–59.

Zhou, W. P., Shen, W. J., Li, Y. E., and Hui, D. F. (2017). Interactive effects of temperature and moisture on composition of the soil microbial community. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 68:12488. doi: 10.1111/ejss.12488

Keywords: soil nutrients, wheat growth, bacterial function, temperature treatment, ecosystems

Citation: Guo Z, Han J, Zhang Y and Zhuang H (2025) Effects of temperature and time treatment on soil characteristics and wheat growth. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1499224. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1499224

Received: 20 September 2024; Accepted: 17 February 2025;

Published: 07 March 2025.

Edited by:

Weicong Qi, Jiangsu Academy of Agricultural Sciences (JAAS), ChinaReviewed by:

Amit Anil Shahane, Central Agricultural University, IndiaCopyright © 2025 Guo, Han, Zhang and Zhuang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jichang Han, aGFuamNfc3hkakAxMjYuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.