- 1Department of Sociology and Rural Development, Khulna Agricultural University, Khulna, Bangladesh

- 2Department of Agroforestry and Environmental Science, Sylhet Agricultural University, Sylhet, Bangladesh

- 3Institute of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science, Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, Kiel, Germany

- 4Open School, Bangladesh Open University, Gazipur, Bangladesh

- 5Department of Community Medicine and Global Health, Institute of Health and Society, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Introduction: Women play an important role in maintaining household food security; unfortunately, their food security is frequently neglected. This type of phenomenon has become common in developing nations such as Bangladesh, particularly in its rural areas. The objective of this study is to investigate the variables that lead to the empowerment of rural women and its impact on their food security. In acknowledging women's significant contribution to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 2 (SDG-2)- Zero Hunger, this study investigates how access to resources, social support, and policy perceptions impact women's empowerment and food security.

Methods: A total of 480 rural women from the southern part of Bangladesh were questioned, and their responses were analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modeling.

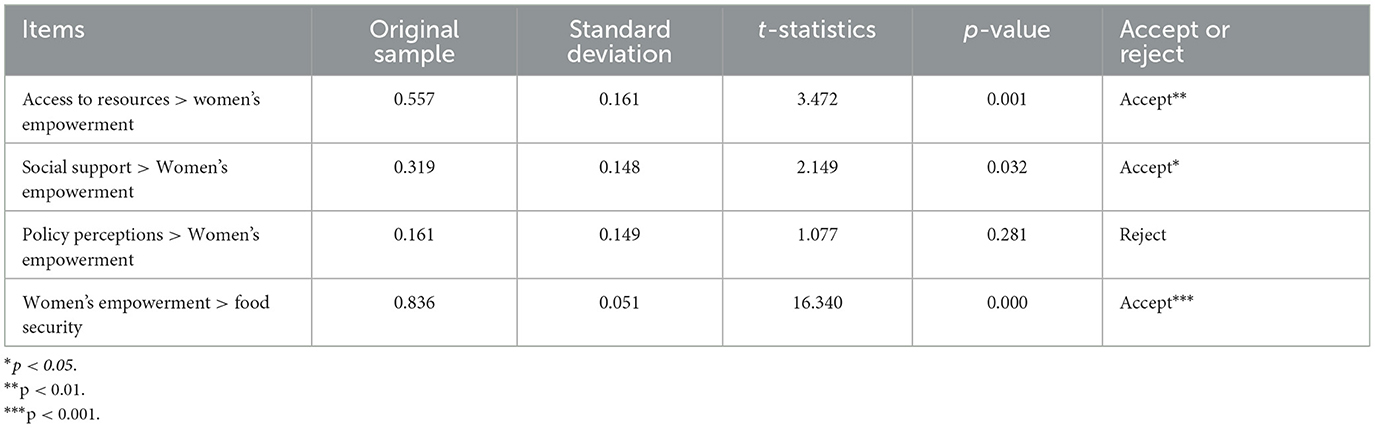

Results: We found that access to resources, social support, and policy perceptions explain 74% of women's empowerment variance and women's empowerment explains 70% variance of women's food security. Access to resources and social support has significant positive impacts on women's empowerment. However, policy perceptions have a positive but not significant impact on women's empowerment. We also observed that women's empowerment significantly improved their food security.

Practical implications: To empower women and improve their food security, the accessibility of resources and support from social networks must be improved. The study emphasizes the importance of strengthening the government's policies, which aim to improve the livelihood conditions of vulnerable people through regular monitoring to overcome underlying obstacles. Our study offers empirical data that policymakers can use to address complex food affordability and security challenges during global crises, enabling the achievement of SDG-2 in rural areas of Bangladesh and similar societies.

1 Introduction

Food security is a prominent concern in the rural regions of Bangladesh, particularly for women who face poverty and societal exclusion (Tariqujjaman et al., 2023). The sustainable development goals (SDGs) seek to address the most significant challenges in human development. These objectives are grouped into 15 categories and include specific targets and indicators to measure progress. The first and second goals are to: (1) eradicate poverty in all of its forms on a global scale; and (2) eradicate hunger, achieve food security, enhance nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture (United Nations, 2015). However, the degree of food insecurity has often been above the levels required to achieve the SDGs about hunger and nutrition (United Nations, 2020). Household food insecurity refers to a situation when there is inadequate availability of food that is both nutritionally safe and meets the dietary needs for sustaining an active and healthy lifestyle. Food insecurity significantly contributes to world hunger and malnutrition (Chowdhury et al., 2016). In 2018, almost 26.4% of the global population experienced severe or moderate food insecurity (United Nations, 2020). Due to financial constraints or limitations to resources, people often face moderate food insecurity that prevents them from buying nutritious and adequate meals regularly (United Nations, 2021).

Food insecurity and chronic child malnutrition are two issues in South Asia that are caused by gender inequalities in health and education, as well as women's low status (von Grebmer et al., 2014). South Asian nations possess the second-largest disadvantaged and malnourished populations globally, and they suffer significant health problems since the majority of their citizens experience acute hunger (FAO et al., 2019). Food insecurity is an important health concern in Bangladesh, especially for women and children (Akhtar, 2016; Wei et al., 2021a). Women in Bangladesh with children are prone to encounter food insecurity and inadequate food consumption due to financial constraints (Shannon et al., 2008). Rural women in Bangladesh experience food insecurity due of low women's empowerment status within their communities (Wei et al., 2021a).

Empowering women has been recognized as an effective way to improve family food security and nutrition (Sraboni et al., 2014). Empowerment refers way by which a person gains the capacity to make independent choices to lead a life that they consider precious (Kabeer, 1999; Galiè et al., 2017). The sustainable development agenda targets gender equality and women's empowerment with the goal to increase women's opportunities and reduce the gender gap (Agarwal, 2018). SDG-5 is a component of the 17 SDGs which specifically aims to achieve gender equality and empower women. Attaining this SDG may promote the establishment of sustainable economies, a harmonious society, and comprehensive advancement. Gender equality and the women's empowerment are crucial factors in attaining SDG 2 in the rural regions of Bangladesh. Scholars and development practitioners are still working to understand what defines this ability for self-determination and to identify the important dimensions of empowerment that may be assessed. The selection of domains to give preference to, such as economic, psychological, or political, may be influenced by factors such as the specific local environment or the subject matter being studied (Bayissa et al., 2018). Research has shown that in the context of empowerment and nutrition, when women contribute money to their families, there is a greater chance of improving child and household nutrition compared to when males contribute money (Smith et al., 2003). Nevertheless, a complex and comprehensive understanding of the ways in which women's empowerment impacts household nutrition and food security remains elusive. For instance, research carried out in Ghana showed that the empowerment of women had a significant correlation with the quality of breastfeeding practices, but only weakly positively associated with child nutrition status (Malapit and Quisumbing, 2015). Research conducted in South Africa discovered that some aspects of women's empowerment, which were impacted by socio-cultural variables that directly impeded agricultural productivity, had an obvious effect on food security (Sharaunga et al., 2015).

In addition to poverty and economic difficulties, there are other variables in people's lives that could impact their ability to fulfill their dietary needs and make them more susceptible to food insecurity like social network issues (Miller et al., 2015; Sseguya et al., 2018). Social support comprises emotional and informational cooperation provided by those within one's social network, including spouses, family members, relatives, neighbors, and other community members (Brummett et al., 2005; Sharifi et al., 2017). Research demonstrated that social support programs have a significant impact on empowering women and addressing issues related to food security and reducing vulnerability (Devereux, 2016). However, different results were also obtained by Walker J. L. et al. (2007) that there is a negative correlation between social support and food insecurity, which has a direct impact on health status. The nature of social support varies depending on cultural, ethnic, and socioeconomic factors (Miller et al., 2015).

Micro-credit initiatives are widely acknowledged as a potent means of empowering women, particularly in rural regions of poor nations such as Bangladesh. These initiatives offer microcredit to women who are unable to use conventional banking services, allowing them to initiate or grow small enterprises, invest in agricultural resources, and enhance their household's financial security (Khandker et al., 2016). The Grameen Bank, founded by Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, is a leading institution in the field of micro-credit. It has shown that micro-credit may greatly improve women's economic activity and empowerment (Yunus, 2006). Micro-credit enables women to achieve financial autonomy and enhance their authority in making decisions both at home and in the community (Khursheed, 2022). Women's financial independence enables them to make more impactful contributions to household food security and nutrition through investments in higher quality food, healthcare, and education for their families (Sinclair et al., 2022). Micro-credit also promotes women's engagement in income-generating endeavors, which can result in enhanced self-confidence, social standing, and influence (Khursheed, 2022). Nevertheless, the effectiveness of micro-credit schemes relies on the manner in which they are structured and executed. Programs that demonstrate sensitivity to the specific socio-cultural environment of a given locality and offer supplementary assistance, such as training and access to markets, have a higher likelihood of achieving success in empowering women and enhancing food security. Although there have been some concerns regarding the high interest rates and payback pressures associated with micro-credit, the overall effect on women's empowerment and food security in rural Bangladesh is favorable (Nawaz, 2019). Therefore, micro-credit is considered a crucial element of development initiatives aimed at meeting the SDGs.

Furthermore, the government of Bangladesh has taken numerous initiatives to enhance women's empowerment level by acknowledging the role of women in the agricultural sector and their impact on family nutrition (USAID, 2023; WFP, 2023). The objective of the Vulnerable Group Development (VGD) initiative is to enhance the capabilities of impoverished women via the supply of food and training (Dhaka Ahsania Mission, 2023; RUPSA Bangladesh, 2023). Furthermore, the objective of the National Women Development Policy is to improve women's access to land and money within their households, so promoting their empowerment and enhancing food security.

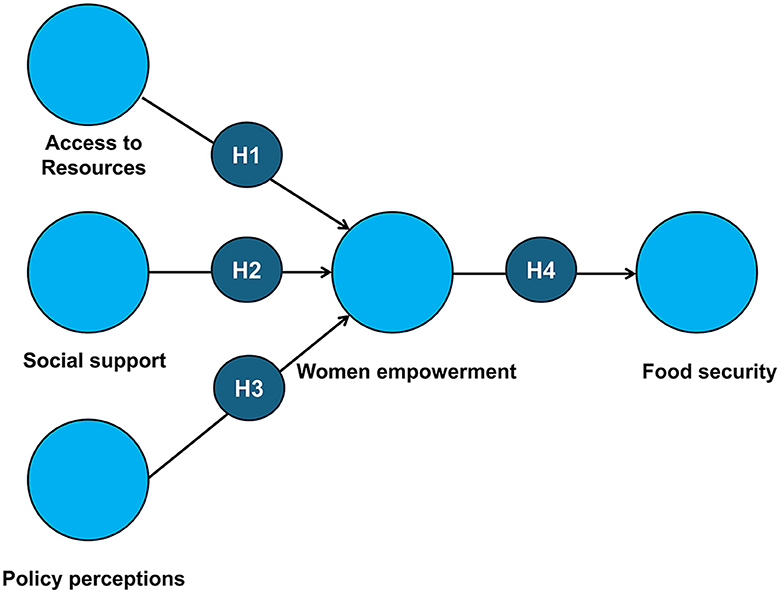

Several investigations have examined the relationship between women's empowerment and food security by considering different variables (Galiè et al., 2019; Aziz et al., 2020; Wei et al., 2021a; Haque et al., 2024). However, to date none of the studies specifically focuses on the influence of social support networks and government initiatives on the improvement of women's food security in the rural areas of Bangladesh. To fulfill this gap, this study seeks to systematically explain how access to resources, social support networks and government programs influence women's empowerment and enhance their food security in rural areas of Bangladesh. To fulfill our research objectives, we set our hypothesis (H) as follows:

• H1: Access to resources positively impacts women's empowerment in rural areas of Bangladesh.

• H2: Social Support positively impacts women's empowerment in rural areas of Bangladesh.

• H3: Policy perceptions positively impact women's empowerment in rural areas of Bangladesh.

• H4: The women's empowerment positively impacts women own's food security.

1.1 Literature review

1.1.1 Relationship between women's empowerment and food security

There is strong evidence from a number of research that shows how empowering women may lead to food security (Aziz et al., 2020, 2021b; Wei et al., 2021a). The importance of women's empowerment in improving nutrition and food security was first highlighted by Upadhyay and Palanivel (2011). A study conducted by Taukobong et al. (2016) corroborated similar findings, indicating that empowering women positively affects several areas of development, including improved food security. According to Vir (2011), women and children in South Asia suffer from poor nutrition because of socio-cultural factors such early marriage, low levels of education, and lack of decision-making power. Htwe (2021) found similar trends in Myanmar, where socioeconomic factors such poverty and lack of access to healthcare had a negative impact on children's nutrition. According to these results, one of the most effective ways to combat their own and their child malnutrition is to raise women's social status and provide them with employment opportunities.

1.1.2 Accessibility to resources and empowerment of women

Empowering women mostly depends on their availability of resources (Aziz et al., 2021a). More chances for women to own property, have financial resources, and have an education have been shown by research to significantly increase their levels of empowerment, which improves food security. As noted by Mohammad Shahan and Jahan (2017), government initiatives in Bangladesh, including the National Food and Nutrition Policy, have successfully increased women's access to resources, which has improved nutritional security. The relevance of education and the dissemination of information is something that cannot be overstated. Higher educated women are more prone to make informed decisions regarding health and nutrition, which benefits food security (Rudolph et al., 2024). Moreover, it is shown that giving women access to financial resources and microcredit schemes improves their economic empowerment and allows them to use the money for better family healthcare and nutrition (Mengstie, 2022).

1.1.3 Social support networks are essential for the empowerment of women

Social support networks are critical for fostering women's empowerment and maintaining food security. Strong social networks provide women with access to information and resources that may improve their level of food security as well as practical help and emotional support (Lemke et al., 2003). Studies have demonstrated the critical contribution that social support plays in empowering women and improving food security (Kuada, 2009; Sharifi et al., 2017; Aziz et al., 2022). Women who engage in social networks and community groups are better positioned to improve their food security (Nosratabadi et al., 2020). These networks may give women more power by letting them bargain as a group, give them access to resources they can share, and give them places to talk about their problems and wants.

1.1.4 The influence of policies on the advancement of women's empowerment

Perceptions of policies have an impact on women's empowerment, albeit the level of their influence varies. Effective policies that promote women's rights, education, and economic opportunities are essential for enhancing their empowerment and guaranteeing their access to an adequate food supply. However, the manner in which these policies are viewed and implemented might influence their efficacy. Hossain et al. (2019) found that female participation in agriculture has a dual impact: it enhances food security and empowers women. Many social protection schemes still give more importance to traditional gender roles of women. This requires deliberate design to redefine women's roles as both producers and decision-makers (Jones et al., 2014). Furthermore, Anderson et al. (2021) emphasized the imperative of bestowing onto women greater authority in several domains, including the business and politics. Enabling women to have decision-making authority can have a significant impact on food security since it enables them to directly affect the nutritional outcomes in their households (Aziz et al., 2024).

1.1.5 Other issues that impact the empowerment of women and the security of food

Aside from access to resources and social support, there are additional factors that influence food security via the empowerment of women. Studies indicate that legal entitlements, societal customs, and economic opportunities are essential factors in influencing the state of food security (Kuada, 2009; Sharifi et al., 2017; Aziz et al., 2020, 2022). Legal rights, such as property ownership and inheritance laws, can empower women by giving them control over important resources. Schleifer and Sun (2020) found empirical evidence supporting the link between land certification and food security, which may be linked to improved land utilization and gender equality. However, the impact of legal rights on the capacity to assume control and guarantee access to an adequate amount of food can be complex and dependent on the particular circumstances (Wei et al., 2021a). Cultural norms and social expectations also have a crucial role. Alonso et al. (2018) have demonstrated that the impact of gender equality within families on food security is diverse, emphasizing the need to address deeply rooted cultural norms to achieve substantial empowerment. The advancement of women is greatly dependent on economic possibilities, including employment options and the capacity to initiate and manage enterprises. Enhancing women's access to markets, fair compensation, and financial services can enable them to significantly contribute to household income, hence improving food security (Wei et al., 2021b). Studies have shown that when women have control over their income, they tend to prioritize spending on nutrition and health, which has a good effect on the well-being of their family (Smith et al., 2003; Wei et al., 2021a).

1.2 Theoretical framework

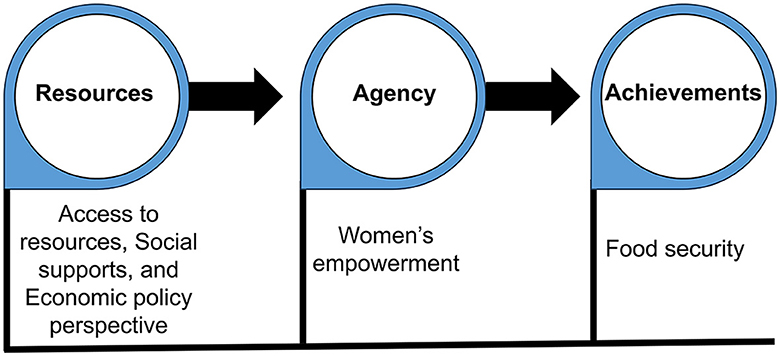

The women's empowerment is a multifaceted process that enables individuals to make purposeful decisions and take control over their lives (Morrison et al., 2007). This paradigm examines interconnected resources, agency, and achievements to understand and empower women (Kabeer, 1999). Analyzing each of these features could assist us in fulfilling our objectives in understanding how women's empowerment improves their food security.

Resources include several assets which can be used by the people to achieve their aims. Resources refer to a wide range of assets, which include financial assets (like cash and capital), social assets (like social supports and social relationships), and human assets (like education and skills) (Kabeer, 1999). Women in South Asia often encounter restricted access to resources as a result of structural and institutional limitations (Hossain et al., 2021; Quisumbing et al., 2022). The accessibility of resources influences the capability of households to buy an adequate amount of food. This is because it improves the money available to purchase food and lessens the possibility of food insecurity (Quisumbing and Meinzen-Dick, 2001).

Agency is the ability to make conscious choices and effectively turn them into desired outcomes. The concept encompasses the use of power in the process of making decisions, the management of financial assets, and having the mobility freedom (Yount, 2006; Clement et al., 2019). The concept of “agency” is associated with the developmental process of people, wherein transformations in their thoughts and self-esteem empower women to make choices and engage in actions based on their own desires (Kabeer, 1999). Nevertheless, the degree of individual independence varies depending upon different social norms and cultural circumstances, hence influencing women's capacity to exercise their freedom in decision-making and choice (Mahmud et al., 2012).

Achievements are the positive outcomes that happen when resources and agencies work together successfully. The effects cover enhanced food security, personal development, and overall welfare of the household (Kabeer, 1999). Sen (1985) states that the integration of resources and agency results in the formation of capabilities, which refer to the numerous techniques people use to achieve fulfillment. These systems encompass the processes of obtaining food security and mitigating potential risks. Women who have been offered authority and control are more capable of ensuring that their households have enough food and may make important contributions to their own personal development and the progress of their communities (Moyo et al., 2012).

Women in Bangladesh, especially women in rural areas often face numerous obstacles in accessing resources and exercising decision-making power because of cultural, sociological, and religious customs. The existence of such barriers obstructs the improvement of women's empowerment and the attainment of food security (Kabeer, 2011; Quisumbing et al., 2022). To overcome these obstacles, it is essential to identify particular elements of women's empowerment in each situation and execute focused interventions to improve their availability of resources and their ability to take action. Women who are empowered possess the capacity to challenge and defy traditional gender expectations, exercise power over resources, and efficiently use them to enhance food security in their households (Cornwall, 2016).

1.3 Conceptual framework

To conceptualize women's empowerment in rural settings, we used Kabeer (1999) empowerment framework (Figure 1). Kabeer (1999) identifies three elements of empowerment: (1) resources, (2) agency, and (3) achievements. The primary aspect of empowerment is the acquisition and management of resources, including material, human, social resources, and economic policy assistance, that women can obtain through their many connections in all areas of family, relatives, friends, society, and community (Mahmud et al., 2012). Resources are essential for enabling empowerment and facilitating the pursuit of goals and improvement of living situations for women. The resources encompassed in this category can comprise of educational opportunities, financial deposits, availability of healthcare services, and relationships with other people. According to Kabeer (1999), resources are a prerequisite that can foster agency. Agency refers to the “ability to define one's goals and act upon them” (Kabeer, 1999). It encapsulates the capacity to gain control over one's own life (Kishor and Gupta, 2004). Agency involves the power to make decisions and to act upon them, reflecting an individual's autonomy and capacity to influence their own circumstances. Sen (1999) defines “agency is the ability to use opportunities to expand the choices to control their own destiny.” In our study, women's empowerment was particularly defined as agency, emphasizing the importance of personal autonomy and decision-making capacity in the empowering process. Agency encompasses more than just having a range of choices; it also involves the ability to make significant decisions and take action based on those choices. This is essential for trustworthy empowerment. Achievement refers to the potential outcomes that result from individual agency, as described by Kabeer (1999). It is a representation of the tangible and ineffable outcomes that are attained when individuals effectively exercise their agency. These accomplishments may encompass enhanced social status, increased participation in community and political activities, economic stability, and improved wellbeing. The capacity to accomplish desired outcomes is a critical metric of empowerment, as it reflects the efficacy of resource utilization and the exercise of agency. We demonstrated a correlation between three measures of resources (access to resources, social supports, and policy perspective), one measure of agency (women's empowerment), and achievement (food security; Figure 2). The present study aimed to evaluate the extent to which factors related to women's empowerment contributed to improving food security.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study site, participants selection, and data collection

The data was obtained through a well-designed survey with questionnaires carried out in the rural areas in the southern part of Bangladesh. Due to its high susceptibility to climate change, periodic natural disasters, and huge levels of poverty, which all have an impact on agricultural output and livelihoods, the southern region of Bangladesh is essential for collecting data on women's empowerment and food security (Alam and Rahman, 2014). Women in this area hold vital responsibilities in the production and management of food, but they often have restricted access to resources, which impedes their ability to achieve economic empowerment and resilience (Nasreen et al., 2023). Moreover, the region serves as a central location for numerous government and non-governmental initiatives targeting enhancing food security and empowering women (Islam and Walkerden, 2015). This makes it a significant subject for evaluating the efficacy of these programmes and creating adaptable solutions. An in-depth comprehension of the distinct socio-economic and environmental obstacles encountered by women in southern Bangladesh can offer significant perspectives for formulating specific strategies to improve food security and promote gender equality in similar situations.

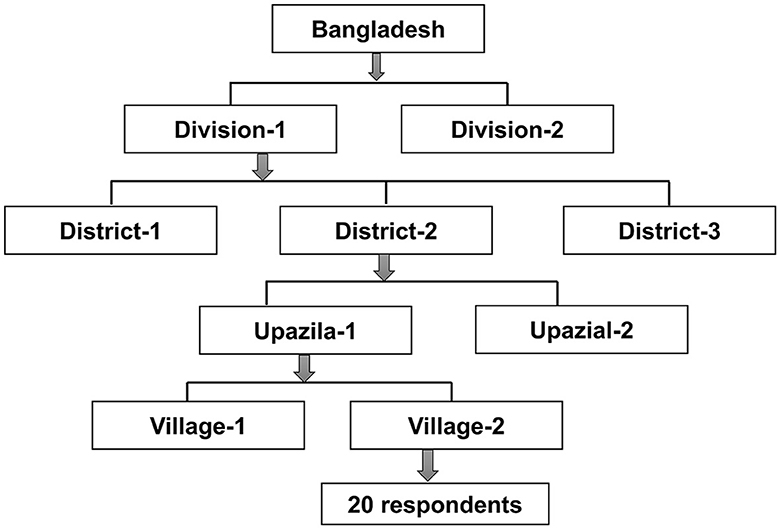

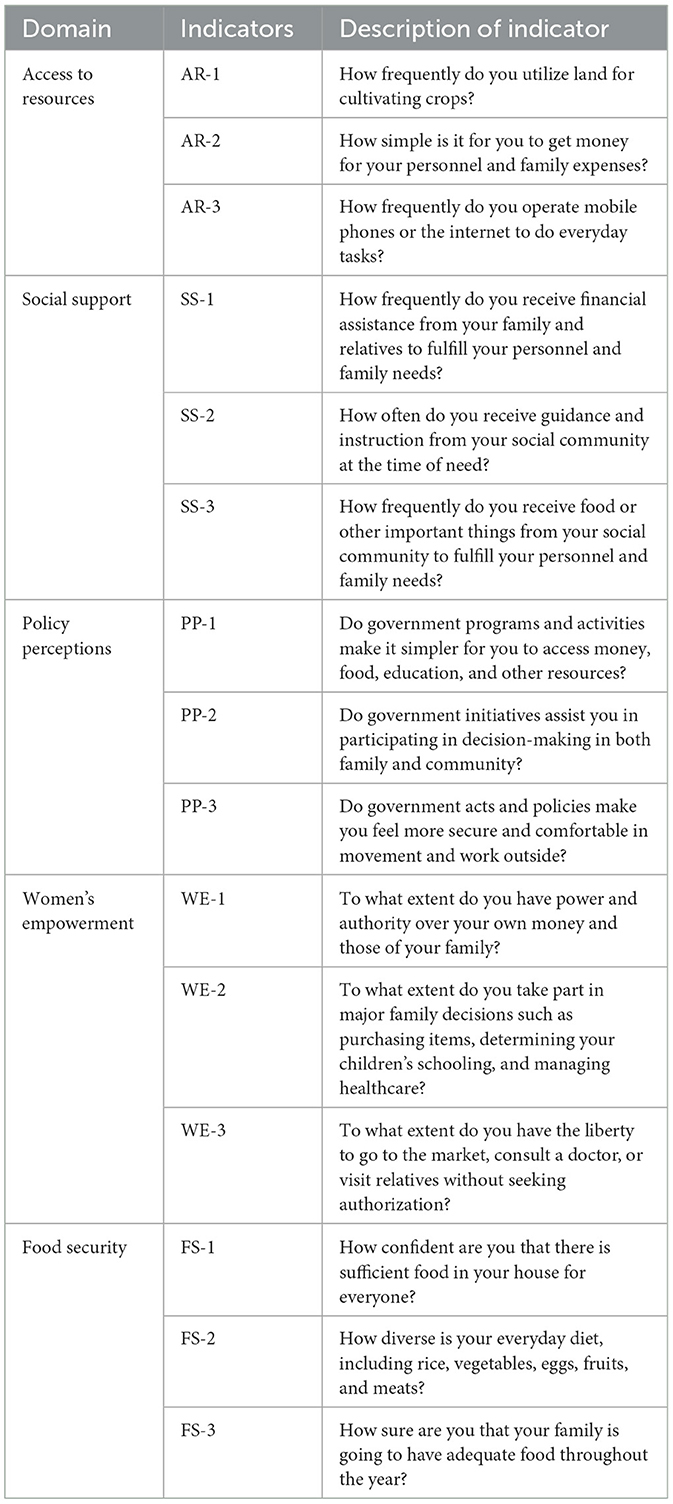

The data for this study was gathered via a meticulously planned survey utilizing structured questionnaires. The study was carried out for a duration of 5 months, spanning from January to May 2023. In order to find and fix any questionnaire design flaws, a small sample of 10 women were interviewed in order to review the questionnaire. First, two divisions, Khulna and Barisal, were purposefully chosen to start the sampling process. Three districts were picked at random from each division. Subsequently, two Upazilas were selected from each district using a comparable random selection method. From the entire list of villages maintained by the Upazila administration, two villages were selected at random within each Upazila. Ultimately, a sample size of 20 houses was chosen at random from each village, with a specific emphasis on women as the participants of the study. This multistage random sampling procedure provided a representative and diversified sample of 480 women (Figure 3). This approach enabled the collection of comprehensive and unbiased data pertinent to the study on women's empowerment and food security in the targeted rural areas. The questionnaire contains validated scales and items that are particularly designed to evaluate different important features, such as the accessibility of resources, the level of social support, evaluations of economic policies, the women's empowerment, and views of food security (Table 1). Questions are intended to collect both quantitative data (such as answers on a 5-point Likert scale) and qualitative data (such as open-ended responses). Before collecting data, participants were provided with comprehensive details on the objectives of the research and provided with the choice to withdraw from their involvement.

2.2 Data analysis

All the raw data were compiled in Excel. The data is then transformed into SPSS 22.0 version for statistical analysis. The partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) technique was used to construct a comprehensive statistical model encompassing all dimensions. We employed Smart-PLS (version 4) to conduct data analysis, accomplishing the primary objective of elucidating the variation in the dependent variables. According to Sarstedt (2008), it is suitable for understanding the mechanism of causal linkages and developing theories. Furthermore, we used the formative model in our study which is more manageable to employ the formative measurement models in PLS-SEM compared to Co-Variance based SEM (Afthanorhan, 2014). The PLS model consists of two stages: the measurement model and the structural model. The measurement model assesses the connection between observable variables (sub-factors) and underlying variables (factors), while simultaneously evaluating the accuracy and consistency of the constructs. The structural model calculates the path coefficients among the constructions. Path coefficients serve as indicators for predicting the model's overall effectiveness. The independent factors in our study consist of access to resources, social support, and economic policy perception, while the dependent variables are women's empowerment and food security.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Demographic analysis

Our study included a total of 480 married women from the rural area of Bangladesh. The majority of respondents in our study were in the 30- to 45-year-old age range (52.7%), which was followed by those in the 18–29 age range (26.7%) and age group over 45 (20.6%; Table 2). The women and their partners were classified into six groups according to their educational level: (a) illiterate (4.4% for women and 3.3% for husbands); (b) primary (13.5% for women and 11.3% for husbands); (c) secondary (46.7% for women and 16.3% for husbands); (d) higher secondary (13.1% for women and 23.8% for husbands); (e) graduate (12.1% for women and 29.8% for husbands); and (f) postgraduate (10.2% for women and 15.6% for husbands). The vast majority of women in rural regions (78.8%) worked for no pay (Table 2).

3.2 Measurement model analysis

The measurement model data presented in Table 3 elucidates the relationship between each latent variable and the observable variables. Formative measurement models are evaluated considering convergent validity, collinearity, and statistical significance and relevance of each indicator (Hair et al., 2013). Table 3 summarizes the findings from the verification of the internal consistency of each construct's indicators, t-statistics, p-value, VIF, and R2 value. Most of them are well-established criteria for evaluating formative measurement models (Kwong-Kay Wong, 2013). The R2 values of 0.744 and 0.699 indicate that access to resources, social support and policy perceptions can interpret 74% of the variance of the women's empowerment, and women's empowerment can interpret 70% of the variance of the food security (Figure 4). Moreover, the VIF values of most of the indicators were within acceptable levels, indicating low multicollinearity (Hair et al., 2013). The measurement model shows that the selected indicators accurately measure the underlying components they aim to measure. This suggests that the survey techniques employed in this study can assess variables reliably and consistently.

3.3 Structural model analysis

For the purpose of testing the hypothesized relationships between latent constructs, the structural model was analyzed. The t-statistics, p-values, standardized path coefficients, and conclusions concerning the acceptance or rejection of each path in the structural model are displayed in Table 4.

Access to resources (β = 0.557, t = 3.472, p = 0.001), has a positive and significant effect on women's empowerment, indicating that women's empowerment can be increased by 56%, with the women's access to resources (Table 4; Figure 4). Access to resources was assessed by questioning the respondents about their accessibility to cultivating agricultural land, cash and adoption of ICT in their farming and daily life. We also observed that women's empowerment positively enhanced their food security. The results are consistent with previous research, which emphasizes the significance of women's access to resources in affecting their ability to reduce, adapt to, and recover from unexpected occurrences and stressful situations (Bryan et al., 2013; Fisher and Carr, 2015; Murray et al., 2016; de Pinto et al., 2020). This study expands the comprehension of these dynamics by demonstrating that the availability of land, financial assets, and the use of ICTs greatly enhances women's empowerment, which, in turn, has a beneficial impact on their sense of food security. The key reason behind these findings is that women's access to resources provides them with the essential means and chances to engage more actively in economic activities, make well-informed choices, and have more influence over family and agricultural productivity (CARE-USA, 2020). When women are given the opportunity to own land, they are able to participate in agricultural activities that enhance the availability and variety of food within their households (Hoddinott et al., 2015; Sibhatu et al., 2015; Mulmi et al., 2016). Financial resources empower women to distribute a higher amount of funds toward valuable assets, acquire high-quality resources, and engage in market activities, therefore augmenting their financial status and influence within their home and society. Furthermore, the availability of ICTs enables women to acquire crucial knowledge about agricultural techniques, market rates, and weather predictions, all of which are necessary for maximizing their agricultural output and reducing potential hazards (Tambo and Abdoulaye, 2012; Bryan et al., 2013; Twyman et al., 2014). Access to information can help close the knowledge gap and enable women to adopt enhanced agricultural practices and expand their sources of income, resulting in improved food security results. The pathways via which women's empowerment leads to enhanced food security are complex and varied. Women who have been given authority are more inclined to make choices that give priority to the nutrition of their home, such as using money to buy healthy food and investing in the child education (Eissler et al., 2020). Empowerment also amplifies women's involvement in community groups and cooperatives, hence facilitating the establishment of supplementary support networks and access to resources (Meier zu Selhausen, 2015; Yokying and Lambrecht, 2020).

Social networks may play a crucial role in expanding women's access to knowledge, financing, and markets, so further improving their food security. We observed that social support (β = 0.319, t = 2.149, p = 0.032), have a positive and significant effect on women's empowerment, suggesting that women's empowerment can be increased by 32%, with the social supports (Table 4; Figure 4). Social support was assessed by questioning the women about how they receive financial support from their surrounding relatives to fulfill their dietary requirements and family needs, and how active they are in their social support network when it comes to sharing information and learning new skills. We also observed that women's empowerment positively enhanced their food security. The study's findings indicate that social support has a positive effect on women's empowerment, leading to an improvement in women's food security. This aligns with other studies suggesting that social support may enhance women's understanding, emotional welfare, and exchange of resources, all of which lead to enhanced nutritional security and health results (Na et al., 2019; Mokari-Yamchi et al., 2020). Studies have demonstrated that social support mechanisms, such as offering information on nutrition and childcare, providing emotional support for mental wellbeing, and giving practical assistance by sharing resources, have a substantial positive impact on the health of women and their kids (Walker S. P. et al., 2007; Miller et al., 2015). In rural areas of Bangladesh, where women's educational attainment may be limited, social support plays a crucial role in obtaining vital information and skills about health and nutrition. For example, social networks may offer women valuable information on the best strategies for feeding and maintaining sanitation for children. This immediately enhances the nutritional wellbeing of children and mitigates the issue of food poverty (Hadley et al., 2007). Maternal mental health is improved by receiving psychological assistance from family and community members. This, in turn, is associated with better care practices and the growth of the child (Bryan et al., 2013; de Pinto et al., 2020). Moreover, social capital, which refers to the connections, shared values, and confidence that enable effective collaboration and cooperation for mutual advantage, has been linked to a decreased likelihood of experiencing hunger and food insecurity at the household level (Martin et al., 2004). The impacts of food insecurity are lessened in robust, cohesive communities where people frequently exchange knowledge, seeds, and even food, especially during hard times (Nagata et al., 2015). The ways in which social support improves women's empowerment and food security are complex and varied. Providing instrumental help, such as financial aid or assistance with routine tasks, might enable women to allocate more time and resources toward income-generating activities. This, in turn, enhances their economic autonomy and empowerment (Kabir et al., 2019). Providing emotional support to women can enhance their overall well-being and self-assurance, enabling empowering them in their homes and societies (Martin et al., 2004).

We observed that policy perceptions (β = 0.161, t = 1.077, p = 0.281) have a positive but not significant effect on women's empowerment (Table 4; Figure 4). Evidence reveals that intermediaries and corruption often impede government projects that aim to help vulnerable individuals, especially women. Research shows that intermediaries and unscrupulous leaders may seize money referred to for the poor, reducing government effectiveness (Anderson, 2023). Corruption and inefficiency hindered Ugandan agricultural output and food security measures from reaching their intended users (Wakaabu, 2023). Inadequate supervision and accountability may reduce help and resource allocation. Hussein and Suttie (2016) indicate that intermediaries in Tanzanian agricultural initiatives drain an enormous amount of resources before they reach their intended recipients. Lack of immediate assistance decreases the impact of these activities on women's empowerment and food security. Women face institutional and systemic barriers such as gender stereotypes and limited land and financing, which might damage these initiatives. Even with good legislation, socio-cultural norms often prevent women from fully benefiting (Meinzen-Dick et al., 2019). The VGD project and the National Women Development Policy in Bangladesh aim to improve women's resource access. Goals are sometimes hampered by social and organizational obstacles (Kabir et al., 2019). However, effective programme design and execution can significantly improve outcomes. Programming without local context and community stakeholders throughout design and execution is unlikely to succeed. Studies show that inclusive solutions that include local communities and consider gender-specific needs and restrictions improve women's food security (Sharifi et al., 2017; Kassie et al., 2020).

The women's empowerment (β = 0.836, t = 16.34, p < 0.000), has a positive and significant effect on food security perception, suggesting that women's food security can be improved by 84%, with the women's empowerment (Table 4; Figure 4). Women's empowerment is being increasingly seen as crucial for family food security and nutrition. Empowerment—the ability to make decisions—has a major impact on women and their families. Several authors emphasize the need to understand empowerment's key areas to properly evaluate its impact, which can vary from place to place and situation to situation (Sraboni et al., 2014; Bayissa et al., 2018; Aziz et al., 2020). They found that empowered women who contribute financially to the household, try to spend more budget on food for the household compared to men (Aziz et al., 2020; Wei et al., 2021a). This underlines the importance of women's empowerment in household nutrition. Within their families, empowered women in rural Bangladesh are more likely to make decisions about food production, consumption, and expenditure (Wei et al., 2021b). Doss et al. (2018) observed that women's engagement in decision-making improves household resource allocation to nutrition and food security. This is especially important in rural Bangladesh, where gender norms constrain women's decision-making (Wei et al., 2021b). Encouraging women to participate in family decisions can improve food distribution and diet diversity, addressing food security. Access to land, funds, and agricultural inputs is vital to empowering women. According to Malapit et al. (2015), women who have access to these resources are more likely to invest in agriculture, which boosts food production and household food security. The women's empowerment also improves nutrition and health. Empowered women can make better food, nutrition, and healthcare decisions for themselves and their families. Research shows that empowered women value healthy food more, which improves health and reduces food insecurity (Smith et al., 2003). In rural Bangladesh, the empowerment of women is the key to achieve SGD-2.

4 Conclusion

The present research emphasizes the importance of various resources and social support networks for women's empowerment and food security in rural areas in Bangladesh. We found that access to land for cultivating purposes, financial resources, and various ICT tools empowers women and improves food security. Various social supports from relatives and neighborhoods also play a significant role in strengthening women's empowerment by providing money, information, and emotional support during crisis periods which also positively improves women's food security at the household level. However, intermediaries and systemic flaws occasionally hinder the projected benefits of women's empowerment through economic policy viewpoints, requiring stronger and comprehensive policy execution. The results demonstrate that giving women access to resources and strong social networks improves women's empowerment and their food security. Empowered women actively participate in household decision-making, use money wisely, and give more emphasis on household nutritional security. The study's findings suggest that a comprehensive approach should be taken to ensure better food security among women in rural Bangladesh. Efforts should primarily concentrate on enhancing access to resources like income, land, financial assets, and ICTs. This is because there is a noticeable positive impact on women's empowerment when these resources are made more accessible. This involves establishing laws and initiatives that promote women's access to land ownership, customizing financial services to meet their specific requirements, and provide training on the application of ICT for agricultural and everyday life activities. Furthermore, it is crucial to enhance social support networks through community-based interventions and support programs, given the significant influence of social support on well-being. Establishing resilient social networks, which include women's organizations and cooperatives, can create possibilities for the exchange of knowledge, resources, and emotional assistance, thereby strengthening empowerment and improving results related to food security. To optimize the efficacy of government initiatives that aim to empower women and enhance food security, it is crucial to eliminate societal obstacles and enhance policy execution, specifically in addressing corruption and gender stereotypes. In addition, by encouraging women to actively participate in decision-making processes and defying societal expectations on gender roles, we may greatly improve the ability of households in rural Bangladesh to have enough food and maintain good nutrition. This, in turn, will contribute to the achievement of SDG-2. These comprehensive solutions emphasize the significance of holistic interventions that tackle the various complex difficulties experienced by rural women, ultimately promoting sustained food security and empowerment outcomes.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval were not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants was obtained to participate in this study. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

TS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Visualization, Writing—original draft. RR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. SY: Funding acquisition, Visualization, Writing— review & editing. MA: Funding acquisition, Resources, Validation, Writing—review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Open access funding was provided by the University of Oslo.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Afthanorhan, W. M. A. B. W. (2014). Hierarchical component using reflective-formative measurement model in Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Int. J. Math. Stat. Invent. 2, 55–71.

Agarwal, B. (2018). Gender equality, food security and the sustainable development goals. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 34, 2–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2018.07.002

Akhtar, S. (2016). Malnutrition in South Asia—a critical reappraisal. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 56, 2320–2330. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2013.832143

Alam, K., and Rahman, M. H. (2014). Women in natural disasters: a case study from southern coastal region of Bangladesh. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 8, 68–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2014.01.003

Alonso, B. E., Cockx, L., and Swinnen, J. (2018). Culture and food security. Glob. Food Secur. 17, 113–127. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2018.02.002

Anderson, C. L., Reynolds, T. W., Biscaye, P., Patwardhan, V., and Schmidt, C. (2021). Economic benefits of empowering women in agriculture: assumptions and evidence. J. Dev. Stud. 57, 193–208. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2020.1769071

Anderson, P. (2023). Cobalt and corruption: the influence of multinational firms and foreign states on the democratic Republic of the Congo. J. Glob. Bus. Community 14. doi: 10.56020/001c.72664

Aziz, N., He, J., Raza, A., and Sui, H. (2022). A systematic review of review studies on women's empowerment and food security literature. Glob. Food Secur. 34:100647. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2022.100647

Aziz, N., Khan, I., Nadahrajan, D., and He, J. (2021a). A mixed-method (quantitative and qualitative) approach to measure women's empowerment in agriculture: evidence from Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan. Community Work Fam. 26, 21–44. doi: 10.1080/13668803.2021.2014783

Aziz, N., Nisar, Q. A., Koondhar, M. A., Meo, M. S., and Rong, K. (2020). Analyzing the women's empowerment and food security nexus in rural areas of Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan: by giving consideration to sense of land entitlement and infrastructural facilities. Land Use Policy 94:104529. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104529

Aziz, N., Raza, A., Sui, H., and Zhang, Z. (2024). Empowering women for embracing energy-efficient appliances: unraveling factors and driving change in Pakistan's residential sector. Appl. Energy 353:122156. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2023.122156

Aziz, N., Ren, Y., Rong, K., and Zhou, J. (2021b). Women's empowerment in agriculture and household food insecurity: evidence from Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK), Pakistan. Land Use Policy 102:105249. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105249

Bayissa, F. W., Smits, J., and Ruben, R. (2018). The multidimensional nature of women's empowerment: beyond the economic approach. J. Int. Dev. 30, 661–690. doi: 10.1002/jid.3268

Brummett, B. H., Mark, D. B., Siegler, I. C., Williams, R. B., Babyak, M. A., Clapp-Channing, N. E., et al. (2005). Perceived social support as a predictor of mortality in coronary patients: Effects of smoking, sedentary behavior, and depressive symptoms. Psychosom. Med. 67, 40–45. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000149257.74854.b7

Bryan, E., Ringler, C., Okoba, B., Roncoli, C., Silvestri, S., and Herrero, M. (2013). Adapting agriculture to climate change in Kenya: household strategies and determinants. J. Environ. Manage. 114, 26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.10.036

CARE-USA (2020). “Gender equality and women's empowerment in the context of food security and nutrition,” in CFS Forum on Women's Empowerment in the context of Food Security and Nutrition,Rome, 2017 (CFS 2017/Inf 21), 1–48. Available online at: http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/cfs/Docs1920/Gender/GEWE_Scoping_Paper-FINAL040ct.pdf%0A3 (accessed June 18, 2024).

Chowdhury, M. R. K., Khan, M., Rafiqul Islam, M., Perera, N. K. P., Shumack, M. K., and Kader, M. (2016). Low maternal education and socio-economic status were associated with household food insecurity in children under five with diarrhoea in Bangladesh. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 105, 555–561. doi: 10.1111/apa.13325

Clement, F., Buisson, M. C., Leder, S., Balasubramanya, S., Saikia, P., Bastakoti, R., et al. (2019). From women's empowerment to food security: revisiting global discourses through a cross-country analysis. Glob. Food Secur. 23, 160–172. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2019.05.003

Cornwall, A. (2016). Women's empowerment: what works. J. Int. Dev. 28, 342–359. doi: 10.1002/jid.3210

de Pinto, A., Cenacchi, N., Kwon, H. Y., Koo, J., and Dunston, S. (2020). Climate smart agriculture and global food-crop production. PLoS ONE 15, 1–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231764

Devereux, S. (2016). Social protection for enhanced food security in sub-Saharan Africa. Food Policy 60, 52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2015.03.009

Dhaka Ahsania Mission (2023). Dhaka Ahsania Mission. Vulnerable Group Development Programme. Available online at: https://www.ahsaniamission.org.bd/vulnerable-group-development-programme/ (accessed May 20, 2024).

Doss, C., Meinzen-Dick, R., Quisumbing, A., and Theis, S. (2018). Women in agriculture: four myths. Glob. Food Secur. 16, 69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2017.10.001

Eissler, Y., Dorador, C., Kieft, B., Molina, V., and Hengst, M. (2020). Virus and potential host microbes from viral-enriched metagenomic characterization in the high-altitude wetland, Salar de Huasco, Chile. Microorganisms 8:1077. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8071077

FAO IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO. (2019). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2019. Rome: FAO.

Fisher, M., and Carr, E. R. (2015). The influence of gendered roles and responsibilities on the adoption of technologies that mitigate drought risk: the case of drought-tolerant maize seed in eastern Uganda. Glob. Environ. Change 35, 82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.08.009

Galiè, A., Jiggins, J., Struik, P. C., Grando, S., and Ceccarelli, S. (2017). “Women's empowerment through seed improvement and seed governance: evidence from participatory barley breeding in pre-war Syria.” NJAS - Wageningen J. Life Sci. 81, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.njas.2017.01.002

Galiè, A., Teufel, N., Girard, A. W., Baltenweck, I., Dominguez-Salas, P., Price, M. J., et al. (2019). Women's empowerment, food security and nutrition of pastoral communities in Tanzania. Glob. Food Secur. 23, 125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2019.04.005

Hadley, C., Zodhiates, A., and Sellen, D. W. (2007). Acculturation, economics and food insecurity among refugees resettled in the USA: a case study of West African refugees. Public Health Nutr. 10, 405–412. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007222943

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2013). PLS-SEM: rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Plann. 47, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2013.01.001

Haque, S., Salman, M., Hasan, M. M., Prithi, A. A., and Hossain, M. E. (2024). Women's empowerment and its role in household food security to achieve SDGs: empirical evidence from rural Bangladesh. Sustain. Dev. 1−18. doi: 10.1002/sd.2893

Hoddinott, J., Headey, D., and Dereje, M. (2015). Cows, missing milk markets, and nutrition in rural Ethiopia. J. Dev. Stud. 51, 958–975. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2015.1018903

Hossain, M., Asadullah, M. N., and Kambhampati, U. (2019). Empowerment and life satisfaction: evidence from Bangladesh. World Dev. 122, 170–183. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.05.013

Hossain, M., Asadullah, M. N., and Kambhampati, U. (2021). Women's empowerment and gender-differentiated food allocation in Bangladesh. Rev. Econ. Househ. 19, 739–767. doi: 10.1007/s11150-021-09546-x

Htwe, K. M. (2021). Social determinants of undernutrition among under-5 children in rural areas of Myanmar: a narrative review. Asia-Pacific J. Public Health 33, 23–29. doi: 10.1177/1010539520962974

Hussein, K., and Suttie, D. (2016). “Rural-urban linkages and food systems in sub-Saharan Africa, The rural dimension,” in IFAD Research Series 5 (Rome).

Islam, R., and Walkerden, G. (2015). How do links between households and NGOs promote disaster resilience and recovery?: a case study of linking social networks on the Bangladeshi coast. Nat. Hazards 78, 1707–1727. doi: 10.1007/s11069-015-1797-4

Jones, A. D., Shrinivas, A., and Bezner-Kerr, R. (2014). Farm production diversity is associated with greater household dietary diversity in Malawi: findings from nationally representative data. Food Policy 46, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.02.001

Kabeer, N. (1999). Resources, agency, achievements: reflections on the measurement of women's empowerment. Dev. Change 30, 435–464. doi: 10.1111/1467-7660.00125

Kabeer, N. (2011). Between affiliation and autonomy: navigating pathways of women's empowerment and gender justice in rural Bangladesh. Dev. Change 42, 499–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7660.2011.01703.x

Kabir, K. A., Verdegem, M. C. J., Verreth, J. A. J., Phillips, M. J., and Schrama, J. W. (2019). Effect of dietary protein to energy ratio, stocking density and feeding level on performance of Nile tilapia in pond aquaculture. Aquaculture 511:634200. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.06.014

Kassie, M., Fisher, M., Muricho, G., and Diiro, G. (2020). Women's empowerment boosts the gains in dietary diversity from agricultural technology adoption in rural Kenya. Food Policy 95:101957. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101957

Khandker, S. R., Khalily, M. A. B., and Samad, H. A. (2016). Beyond Ending Poverty: The Dynamics of Microfinance in Bangladesh. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications. doi: 10.1596/978-1-4648-0894-4

Khursheed, A. (2022). Exploring the role of microfinance in women's empowerment and entrepreneurial development: a qualitative study. Futur. Bus. J. 8:57. doi: 10.1186/s43093-022-00172-2

Kishor, S., and Gupta, K. (2004). Women's empowerment in India and its states: evidence from the NFHS. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 39, 694–712. doi: 10.2307/4414645

Kuada, J. (2009). Gender, social networks, and entrepreneurship in Ghana. J. Afr. Bus. 1, 85–103. doi: 10.1080/15228910802701445

Kwong-Kay Wong, K. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) techniques using SmartPLS. Mark. Bull. 24, 1–32. Available online at: https://docslib.org/doc/12171658/partial-least-squares-structural-equation-modeling-pls-sem-techniques-using-smartpls (accessed June 18, 2024).

Lemke, S., Vorster, H., van Rensburg, N. J., and Ziche, J. (2003). Empowered women, social networks and the contribution of qualitative research: broadening our understanding of underlying causes for food and nutrition insecurity. Public Health Nutr. 6, 759–64. doi: 10.1079/PHN2003491

Mahmud, S., Shah, N. M., and Becker, S. (2012). Measurement of women's empowerment in rural Bangladesh. World Dev. 40, 610–619. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.08.003

Malapit, H., Sraboni, E., Quisumbing, A., and Akhter, A. (2015). “Gender empowerment gaps in agriculture and children's well-being in Bangladesh,” in IFPRI Discussion Paper (Washington, DC).

Malapit, H. J. L., and Quisumbing, A. R. (2015). What dimensions of women's empowerment in agriculture matter for nutrition in Ghana? Food Policy 52, 54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2015.02.003

Martin, K. S., Rogers, B. L., Cook, J. T., and Joseph, H. M. (2004). Social capital is associated with decreased risk of hunger. Soc. Sci. Med. 58, 2645–2654. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.09.026

Meier zu Selhausen, F. (2015). Women's empowerment in Uganda: colonial roots and contemporary efforts, 1894-2012 (Thesis). University of Sussex. Available online at: https://hdl.handle.net/10779/uos.23427932.v1 (accessed June 18, 2024).

Meinzen-Dick, R., Quisumbing, A., Doss, C., and Theis, S. (2019). Women's land rights as a pathway to poverty reduction: framework and review of available evidence. Agric. Syst. 172, 72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2017.10.009

Mengstie, B. (2022). Impact of microfinance on women's economic empowerment. J. Innov. Entrep. 11, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13731-022-00250-3

Miller, M., Melgar-Quiñonez, H., Dallmann, D., and Ballard, T. (2015). Trends in the contribution of perceived, received, and integrative social support to food security. FASEB J. 29:585.20. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.29.1_supplement.585.20

Mohammad Shahan, A., and Jahan, F. (2017). Opening the Policy Space: the Dynamics of Nutrition Policymaking in Bangladesh Development Research Initiative (dRi). Available online at: http://www.nipn-nutrition-platforms.org/IMG/pdf/nutrition-policy-making-bangladesh.pdf (accessed June 18, 2024).

Mokari-Yamchi, A., Faramarzi, A., Salehi-Sahlabadi, A., Barati, M., Ghodsi, D., Jabbari, M., et al. (2020). Food security and its association with social support in the rural households a cross sectional study. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 25, 146–152. doi: 10.3746/pnf.2020.25.2.146

Morrison, A., Raju, D., and Sinha, N. (2007). Gender Equality, Poverty and Economic Growth. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Moyo, C., Francis, J., and Ndlovu, P. (2012). Community-perceived state of women empowerment in some rural areas of Limpopo Province, South Africa. Gend. Behav. 10, 4418–4431. Available online at: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/gab/article/view/76738 (accessed June 18, 2024).

Mulmi, P., Block, S. A., Shively, G. E., and Masters, W. A. (2016). Climatic conditions and child height: sex-specific vulnerability and the protective effects of sanitation and food markets in Nepal. Econ. Hum. Biol. 23, 63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2016.07.002

Murray, S. B., Griffiths, S., Mond, J. M., Kean, J., and Blashill, A. J. (2016). Anabolic steroid use and body image psychopathology in men: delineating between appearance- versus performance-driven motivations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 165, 198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.06.008

Na, M., Miller, M., Ballard, T., Mitchell, D. C., Hung, Y. W., and Melgar-Quinõnez, H. (2019). Does social support modify the relationship between food insecurity and poor mental health? Evidence from thirty-nine sub-Saharan African countries. Public Health Nutr. 22, 874–881. doi: 10.1017/S136898001800277X

Nagata, Y., Hiraoka, M., Shibata, T., Onishi, H., Kokubo, M., Karasawa, K., et al. (2015). Prospective trial of stereotactic body radiation therapy for both operable and inoperable T1N0M0 non-small cell lung cancer: Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG0403. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 93, 989–996. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.07.2278

Nasreen, M., Mallick, D., and Neelormi, S. (2023). “Empowering women to enhance social equity and disaster resilience in coastal bangladesh through climate change adaptation knowledge and technologies,” in Coastal Disaster Risk Management in Bangladesh: Vulnerability and Resilience, eds. M. Nasreen, K. Mokaddem Hossain, M. Moniruzzaman Khan (London: Routledge), 39. doi: 10.4324/9781003253495-14

Nawaz, F. (2019). Microfinance and Women's Empowerment in Bangladesh: Unpacking the Untold Narratives. Cham: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-13539-3

Nosratabadi, S., Khazami, N., Ben Abdallah, M., Lackner, Z., Band, S. S., Mosavi, A., et al. (2020). Social capital contributions to food security: a comprehensive literature review. Foods 9:165. doi: 10.31220/agriRxiv.2020.00021

Quisumbing, A., Meinzen-Dick, R., and Malapit, H. (2022). Women's empowerment and gender equality in South Asian agriculture: measuring progress using the project-level Women's Empowerment in Agriculture Index (pro-WEAI) in Bangladesh and India. World Dev. 151:105396. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105396

Quisumbing, A. R., and Meinzen-Dick, R. S. (2001). Empowering Women to Achieve Food Security. Available online at: https://www.iatp.org/sites/default/files/Empowering_Women_to_Achieve_Food_Security.htm (accessed June 18, 2024).

Rudolph, M., Muchesa, E., and Sibanda, C. (2024). The Influence of education on women and food security. S. Afr. Agric. Ext. 52, 91–106. doi: 10.17159/2413-3221/2024/v52n2a15734

RUPSA Bangladesh (2023). RUPSA Bangladesh. Vulnerable Groups Development (VGD). Available online at: https://rupsabd.org/blog/vulnerable-groups-development-vgd/ (accessed May 20, 2024).

Sarstedt, M. (2008). A review of recent approaches for capturing heterogeneity in partial least squares path modelling. J. Model. Manag. 3, 140–161. doi: 10.1108/17465660810890126

Schleifer, P., and Sun, Y. (2020). Reviewing the impact of sustainability certification on food security in developing countries. Glob. Food Secur. 24:100337. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2019.100337

Sen, A. (1985). Well-Being, agency and freedom: the dewey lectures 1984. J. Philos. 82, 169–221. doi: 10.2307/2026184

Sen, A. (1999). Development as Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available online at: http://www.c3l.uni-oldenburg.de/cde/OMDE625/Sen/Sen-intro.pdf (accessed June 18, 2024).

Shannon, K., Mahmud, Z., Asfia, A., and Ali, M. (2008). The social and environmental factors underlying maternal malnutrition in rural Bangladesh: implications for reproductive health and nutrition programs. Health Care Women Int. 29, 826–40. doi: 10.1080/07399330802269493

Sharaunga, S., Mudhara, M., and Bogale, A. (2015). The impact of “women's empowerment in agriculture” on household vulnerability to food insecurity in the KwaZulu-Natal province. Forum Dev. Stud. 9410, 1–29. doi: 10.1080/08039410.2014.997792

Sharifi, N., Dolatian, M., Mahmoodi, Z., Abadi, F. M. N., and Mehrabi, Y. (2017). The relationship between social support and food insecurity in pregnant women: a cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Diagnostic Res. 11, IC01–IC06. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/29987.10858

Sibhatu, K. T., Krishna, V. V., and Qaim, M. (2015). Production diversity and dietary diversity in smallholder farm households. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112, 10657–10662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510982112

Sinclair, K., Thompson-Colón, T., Bastidas-Granja, A. M., Del Castillo Matamoros, S. E., Olaya, E., and Melgar-Quiñonez, H. (2022). Women's autonomy and food security: connecting the dots from the perspective of Indigenous women in rural Colombia. SSM - Qual. Res. Heal. 2:100078. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmqr.2022.100078

Smith, L. C., Ramakrishnan, U., Ndiaye, A., Haddad, L., and Martorell, R. (2003). The importance of women's status for child nutrition in developing countries. Res. Rep. Int. Food Policy Res. Inst. 131, 41–51. doi: 10.1177/156482650302400309

Sraboni, E., Malapit, H. J., Quisumbing, A. R., and Ahmed, A. U. (2014). Women's empowerment in agriculture: what role for food security in Bangladesh? World Dev. 61, 11–52. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.03.025

Sseguya, H., Mazur, R. E., and Flora, C. B. (2018). Social capital dimensions in household food security interventions: implications for rural Uganda. Agric. Human Values 35, 117–129. doi: 10.1007/s10460-017-9805-9

Tambo, J. A., and Abdoulaye, T. (2012). Climate change and agricultural technology adoption: the case of drought tolerant maize in rural Nigeria. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change. 17, 277–292. doi: 10.1007/s11027-011-9325-7

Tariqujjaman, M., Rahman, M., Wangdi, K., Karmakar, G., Ahmed, T., and Sarma, H. (2023). Geographical variations of food insecurity and its associated factors in Bangladesh: evidence from pooled data of seven cross-sectional surveys. PLoS ONE 18:e0280157. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0280157

Taukobong, H. F. G., Kincaid, M. M., Levy, J. K., Bloom, S. S., Platt, J. L., Henry, S. K., et al. (2016). Does addressing gender inequalities and empowering women and girls improve health and development programme outcomes? Health Policy Plan. 31, 1492–1514. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czw074

Twyman, L., Bonevski, B., Paul, C., and Bryant, J. (2014). Perceived barriers to smoking cessation in selected vulnerable groups: a systematic review of the qualitative and quantitative literature. BMJ Open 4:e006414. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006414

United Nations (2015). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed May 20, 2024).

United Nations (2020). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. End Hunger, Achieve Food Security and Improved Nutrition and Promote Sustainable Agriculture. Available online at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal2 (accessed May 20, 2024).

United Nations (2021). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. End Hunger, Achieve Food Security and Improved Nutrition and Promote Sustainable Agriculture. Statistics Division. Available online at: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2020/goal-02/ (accessed June 18, 2024).

Upadhyay, R. P., and Palanivel, C. (2011). Challenges in achieving food security in India. Iran. J. Public Health 40, 31–36.

USAID (2023). U.S. Agency for International Development. Agriculture and Food Security | Bangladesh. Available online at: https://www.usaid.gov/bangladesh/agriculture-and-food-security (accessed May 20, 2024).

Vir, S. C. (2011). Public Health Nutrition in Developing Countries: Part 1 and 2, 1st Edn. New York, NY: Woodhead Publishing India in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition. doi: 10.1201/b18288

von Grebmer, K., Saltzman, A., Birol, E., Wiesmann, D., Prasai, N., Yin, S., et al. (2014). Global Hunger Index: The Challenge of Hidden Hunger. Bonn; Washington, DC; Dublin: Welthungerhilfe; International Food Policy Research Institute; Concern Worldwide. doi: 10.2499/9780896299580

Wakaabu, D. (2023). The sensitivity of food security to agricultural input subsidies in Uganda. Int. J. Agric. Sci. Food Technol. 9, 010–015. doi: 10.17352/2455-815X.000184

Walker, J. L., Holben, D. H., Kropf, M. L., Holcomb, J. P., and Anderson, H. (2007). Household food insecurity is inversely associated with social capital and health in females from special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children households in Appalachian Ohio. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 107, 1989–1993. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.08.004

Walker, S. P., Wachs, T. D., Meeks Gardner, J., Lozoff, B., Wasserman, G. A., Pollitt, E., et al. (2007). Child development: risk factors for adverse outcomes in developing countries. Lancet 369, 145–157. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60076-2

Wei, W., Sarker, T., Żukiewicz-Sobczak, W., Roy, R., Monirul Alam, G. M., Rabbany, M. G., et al. (2021b). The influence of women's empowerment on poverty reduction in the rural areas of Bangladesh: focus on health, education and living standard. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:6909. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18136909

Wei, W., Sarker, T., Roy, R., Sarkar, A., and Ghulam Rabbany, M. (2021a). Women's empowerment and their experience to food security in rural Bangladesh. Sociol. Health Illn. 43, 971–994. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.13273

WFP (2023). World Food Programme. Food Security and Nutrition in Bangladesh. Available online at: https://www.wfp.org/operations/bd02-bangladesh-country-strategic-plan-2022-2026 (accessed May 20, 2024).

Yokying, P., and Lambrecht, I. (2020). Landownership and the gender gap in agriculture: Insights from northern Ghana. Land Use Policy 99:105012. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105012

Yount, W. R. (2006). Research Design and Statistical Analysis in Christian Ministry, 4th Edn, 79–102.

Yunus, M. (2006). Interview - Poverty Is a Threat to Peace. Extreme Poverty Destabilizes Societies. Microcredit Helps Reduce That Threat. Available online at: https://www.democracynow.org/2006/12/13/poverty_is_a_threat_to_peace (accessed June 18, 2024).

Keywords: food security, policy perceptions, resources, rural Bangladesh, social support, sustainable development goal 2, women's empowerment

Citation: Sarker T, Roy R, Yeasmin S and Asaduzzaman M (2024) Enhancing women's empowerment as an effective strategy to improve food security in rural Bangladesh: a pathway to achieving SDG-2. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8:1436949. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2024.1436949

Received: 22 May 2024; Accepted: 18 June 2024;

Published: 01 July 2024.

Edited by:

Noshaba Aziz, Shandong University of Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Md. Shakhawat Hossain, Northwest A&F University, ChinaZobia Noreen, Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Pakistan

Copyright © 2024 Sarker, Roy, Yeasmin and Asaduzzaman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rana Roy, cmFuYXJveS5hZXNAc2F1LmFjLmJk; Muhammad Asaduzzaman, bXVoYW1tYWQuYXNhZHV6emFtYW5AbWVkaXNpbi51aW8ubm8=

Tanwne Sarker

Tanwne Sarker Rana Roy

Rana Roy Sabina Yeasmin

Sabina Yeasmin Muhammad Asaduzzaman

Muhammad Asaduzzaman