- 1Department of Life Sciences, Faculty of Sciences, University Ibn Tofail, Kenitra, Morocco

- 2International Centre for Advanced Mediterranean Agronomic Studies (CIHEAM-Bari), Bari, Italy

- 3Department of Nutrition, Exercise and Sports, University of Copenhagen, Frederiksberg, Denmark

- 4Department of Functional and Organic Food, Institute of Human Nutrition Sciences, Warsaw University of Life Sciences, Warsaw, Poland

- 5Faculty of Home Economics and Nutritional Sciences, Facility Management, Münster, Germany

- 6Council for Agricultural Research and Economics, Research Centre for Food and Nutrition (CREA—Food and Nutrition), Rome, Italy

- 7Department Organic Food Quality, Faculty Organic Agricultural Sciences, University of Kassel, Kassel, Germany

Introduction: Morocco is currently witnessing a growing interest in organic food as awareness of health and environmental benefits rises.

Objective: This study aims to evaluate organic food consumption as well as to understand the underlying factors influencing the consumption patterns, including consumers’ preferences and motivations as well as the challenges they face in Kenitra (Morocco).

Method: Data was collected through an anonymous household survey involving 442 respondents, aged 18 and above targeting the population of Kenitra.

Results: The findings reveal that in 60% of the Kenitra households organic foods comprise 1-25% of all the foods consumed, highlighting a growing interest in these products. However, several barriers were identified, including insufficient availability and accessibility of organic products, as well as limited product variety at local shopping places, and the perceived high prices of organic foods, which continue to hinder organic food consumption. Moreover, consumers expressed a need for better access to organic products and emphasized the importance of reasonable pricing, considering it as a significant factor in their decision-making process.

Conclusion: Understanding the dynamics of organic food consumption in Kenitra and the eating attitudes and behaviors of its residents will provide valuable insights that can be employed to reshape future local policies, strategies, and market developments, in response to the changing demands and preferences of the population while promoting the adoption of organic food in the region and the whole country.

1 Introduction

In recent years, the global food industry has witnessed a substantial shift in consumer preferences towards healthier and more sustainable food choices (Lindgren et al., 2018). One prominent manifestation of this trend is organic food that has gained popularity as a healthier and more environmentally conscious alternative to conventionally produced food items (Boobalan and Nachimuthu, 2020; Suciu et al., 2019). Organic food is characterized by its adherence to environmentally friendly farming practices and the absence of synthetic chemicals, fertilizers and pesticides, or any use of growth hormones, genetic modification with limited use of antibiotics (Olson, 2017). Morocco, as a North African country and with its diverse agricultural landscape and burgeoning food market, due to its location at the crossroads of Africa and Europe, has not remained immune to this global movement. In this context, Morocco started multiple action plans and programs to support its organic agricultural sector—starting from the Green Morocco Plan (launched in 2008 and lasting 12 years) to the Green Generation Plan (2020–2030)—which had the general objective to improve the organic agricultural production of the country (Ministry of Economy and Finance, 2019). In 2020, the total cultivated organic area reached 310,303 ha. In terms of production, the sector generated a volume of 120,000 tonnes in 2019 against 40,000 tonnes in 2010 (Ministère de l’agriculture, 2023). Furthermore, 83% of the organically cultivated area is located in five main key regions, namely Fes-Meknes, Marrakech-Safi, Sous-Massa, Casablanca-Settat and Rabat-Salé-Kenitra. The primary crops grown organically in Morocco are olives, almonds, medicinal and aromatic plants (MAP), fruits and vegetables. In addition, there are wild collections such as argan, carob, aromatic plants, prickly pear and capers (Ministère de l’agriculture, 2023). Notably, the majority of these organic agricultural products are intended for export, with export volumes rising significantly from 7,230 tonnes in 2007 to 18,000 tonnes in 2019. This includes 8,000 tonnes of fresh products and 10,000 tonnes of processed products. Most exports consist of fruits, fresh vegetables, and processed products, particularly frozen orange juice, argan oil and its derivatives (e.g., cosmetics), canned green beans, products from medicinal and aromatic plants, frozen strawberries, and capers in brine. The main destination markets for these exports are France, Spain, Italy, Germany, Netherlands, Scandinavia, Lithuania, the USA, Canada, and certain Asian countries such as Japan and South Korea (AgriMaroc, 2020a,b).

Organic food has gained substantial popularity in the country and a significant portion of Moroccan consumers increasingly turned to organic options (AgriMaroc, 2020a,b), especially since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and its gravest effect on public health, economy, quality of life, and food security around the world (Naseer et al., 2023; Azizi et al., 2020; Kakaei et al., 2022). This surge can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, the pandemic raised awareness about the importance of health and well-being, prompting individuals to seek out foods that are perceived as healthier and safer. For this reason, organic products, known for their focus on natural and chemical-free cultivation methods, became an appealing choice for those looking to bolster their immune systems and reduce exposure to potentially harmful substances, considering them as the main weapon to fight SARS-CoV-2 virus. This is due to the quarantine and the media influence (Ben Khadda et al., 2022).

Additionally, the disruption of global supply chains during the pandemic led to a renewed interest in locally-sourced and sustainable Moroccan food options, further boosting the demand for organic produce within Morocco. In the same context, a Moroccan study (El Bilali et al., 2021) found that the COVID-19 pandemic’s effects on food safety and the ensuing concern over virus transmission have increased the consumption of locally produced Moroccan food items. As a result, Moroccan consumers are becoming more inquisitive about the origins of the food they buy (El Bilali et al., 2021). As health consciousness continues to grow and the preference for organic practices becomes more ingrained, the consumption of organic food in Morocco continued its growth even beyond the pandemic (AgriMaroc, 2020a,b).

Despite this, organic food consumption in Morocco is still very limited and concentrated in the big cities such as Casablanca, Marrakech, Rabat, etc. (ConsoNews, 2023; L’agriculture bio dans le monde, 2020). The data concerning the different aspects of organic products consumption as well as Moroccan consumers’ food attitudes are very limited and not fully understood. To our knowledge, no study has discussed the consumption of organic food in Kenitra province (north-western Morocco) or consumer’s perception toward these products.

In this context, the present study aims to assess the consumption level of organic food in Kenitra province by determining the percentage of organic food consumption and identifying the most commonly consumed organic foods in this region. The study also aims to understand consumers’ attitudes, behavior and perception towards these products, and uncover their motivations for choosing organic food as well as the challenges faced in its adoption. Additionally, this article examines the status of organic food purchases by households in Kenitra over the past 5 years and pinpoints the key factors contributing to the increase in purchases.

2 Materials and methods

This study is part of SysOrg project titled “Organic agro-food systems as models for sustainable food systems in Europe and northern Africa.” It was conducted in 2021 by Ibn Tofail University (Faculty of Sciences) in collaboration with partners from Copenhagen University, Warsaw University of Life Sciences, Council for Agricultural Research and Economics, Munster University of Applied Sciences, University of Kassel and International Centre for Advanced Mediterranean Agronomic Studies (CI-HEAM-Bari).

Data was collected through a comprehensive survey “Household Survey of Diet, Organic Food Consumption and Food Waste” that covers three different perspectives: diet, organic and food waste perspective. The survey was structured into five parts, the first part focusing on socio-demographic information, while the subsequent parts cover various aspects related to the three aforementioned perspectives. However, for the purpose of this study, our focus is on the Socio-demographic and the organic aspects only. These parts of the questionnaire consisted of a range of various variables including age, gender, education level, household income, etc. as well as the frequency of consumption of 24 organic food groups utilizing the following frequency categories: always, often, sometimes, never, I do not know, in addition to questions related to eating habits, attitudes and preferences towards organic products.

Prior to the main data collection, the survey instrument underwent a rigorous validation process to ensure its reliability and effectiveness. This included pretesting with a small subset of participants (20 respondents) to identify and address any ambiguities, inconsistencies, or potential issues with the survey questions.

The survey was initially conducted with a sample of 663 households over a three-month period (January–April 2022). After processing, cleaning, and removing incomplete or incorrectly filled responses, the dataset was refined to 442, representing the final sample size. All the participants were adults aged 18 years or older and living in Kenitra.

The survey employed a variety of methods, including face-to-face interviews (streets, beaches, parks, etc.), telephone interviews, and online surveys using all social media platforms, depending on the convenience of the participants. This multi-modal approach was chosen to maximize participation and representation. The participants were selected based on two criteria: being adults and residing in Kenitra. Before analysis, the data was coded and collected in Excel sheets. The SPSS package version 26 was used to analyse the collected data. In this research, we used descriptive analysis by means of descriptive statistics such as frequencies and percentages.

2.1 Ethical aspects

The study was conducted with proper authorization from the Regional Directorate of Health in the Rabat-Salé-Kénitra region and approved by the regional Ethics Committee (CERB05/22). The participants provided their consent freely and with full knowledge of the study’s details.

To generalize the findings of this study, a larger and more diverse sample should be performed to increase the conclusions and reliability.

3 Results

3.1 Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants

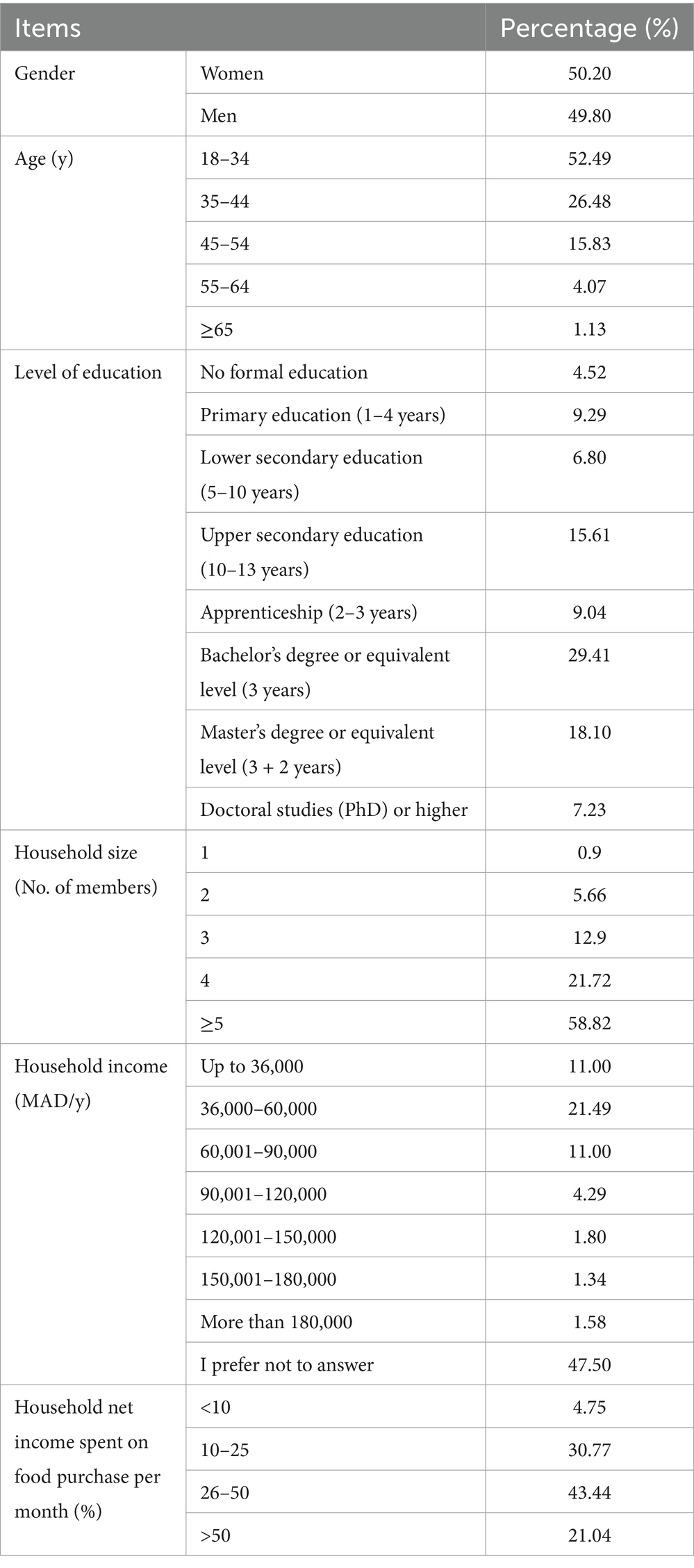

A total of 442 respondents took part in this survey, including 50.20% women and 49.80% men. The full socio-demographic breakdown is shown in Table 1. The major participation recorded was within the age group 18–34 years old (52.49%). This reflects that the majority of the participants were young people. Regarding the level of education, a large portion (47.51%) had a university level, either bachelor’s or master’s degree, 15.61% had a high school education, and only 4.52% had no formal education or had a primary level (9.2%). For the disposable net household income, 21.49% announced that they get from 36,001 to 60,000 Moroccan dirhams per year (MAD; 10 MAD ≈ 1 USD), while most of the participants (47.50%) preferred not to answer this question. Almost 64% of the participants spent 26–50% or more of their net household income on food purchases per month; while 30.7% spent between 10–25%; the remaining respondents (4.75%) spent less than 10% on food purchases per month.

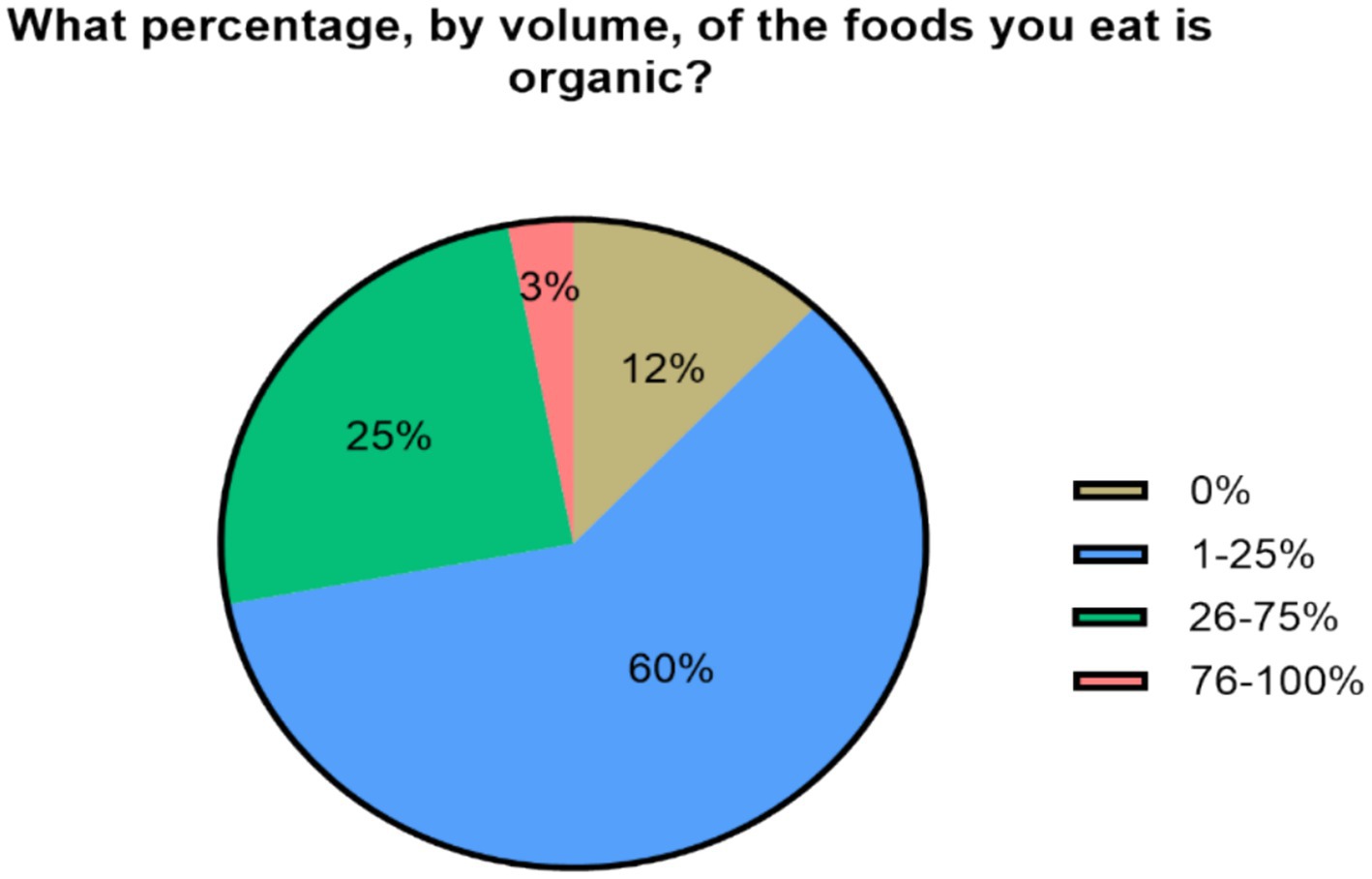

Figure 1 presents the declared share (percentage) of organic food in all the food consumed by the surveyed population. According to the results, the majority of the participants exhibit restrained or limited engagement with organic food consumption. Specifically, 60% of the respondents declare 1–25% share of organic food in their diet, while in the diet of 25% of consumers organic food constituted 26–75% of all foods consumed. The percentage of respondents declaring organic food share of more than 75% is only 3%. The remaining respondents (12%) reported that they do not eat any organic food at all.

Figure 1. Percentage of organic food in all the foods consumed by the surveyed population (n = 442).

3.2 Insights into the organic consumption patterns among the participants

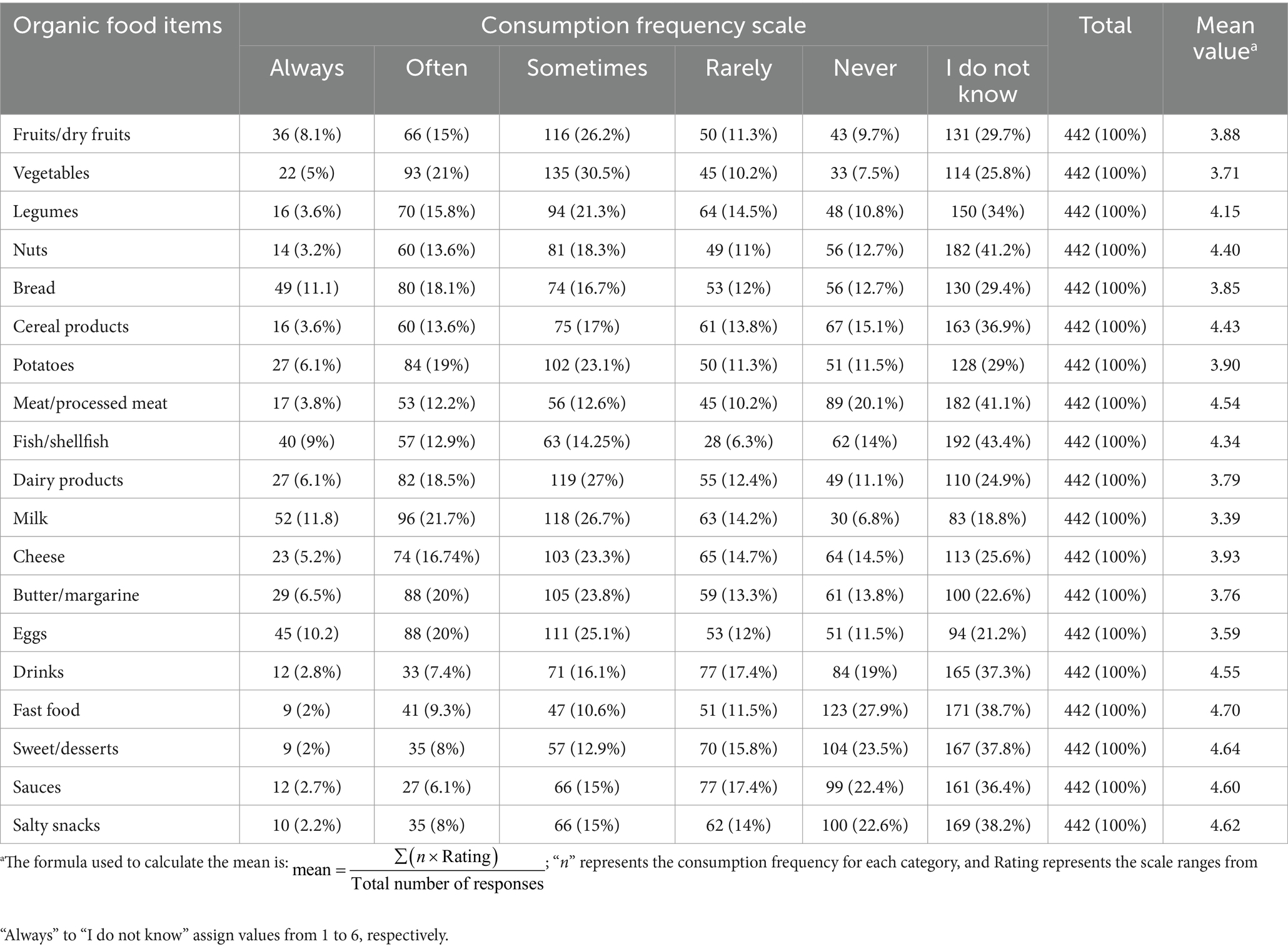

Among the diverse food groups presented in Table 2, organic fruits and vegetables were declared to be consumed “Often” or “Sometimes” by almost 50% of the respondents and only less than 10% of the respondents never consumed them at all. While more than 26% of the respondents stated that they are unsure whether they consume organic or non-organic fruits/vegetables.

Organic cereal products, including bread as one of the prominent food staples in Morocco, were consumed “Sometimes” or “Often” by more than 30% of the respondents, while less than 15% of them never consumed them at all; and more than 30% of respondents remain uncertain about the organic status of the cereal products/bread they consume.

Organic meat and processed meats were consumed “Sometimes” by nearly 13%, and “Never” by over 20%, while a substantial portion of the respondents (41%) admitted uncertainty about their stance on organic or non-organic consumption of meat and processed meat selecting the “I do not know” option.

For organic milk and dairy products, “Often” emerged as the most prevalent category, with approximately 27% of the participants indicating that they frequently opt for organic milk; the “Never” category, encompassed approximately 11% of the respondents.

Organic eggs were consumed “Sometimes” by 25%, “Often” by 20%, and “Never” by 11% of the interrogated population.

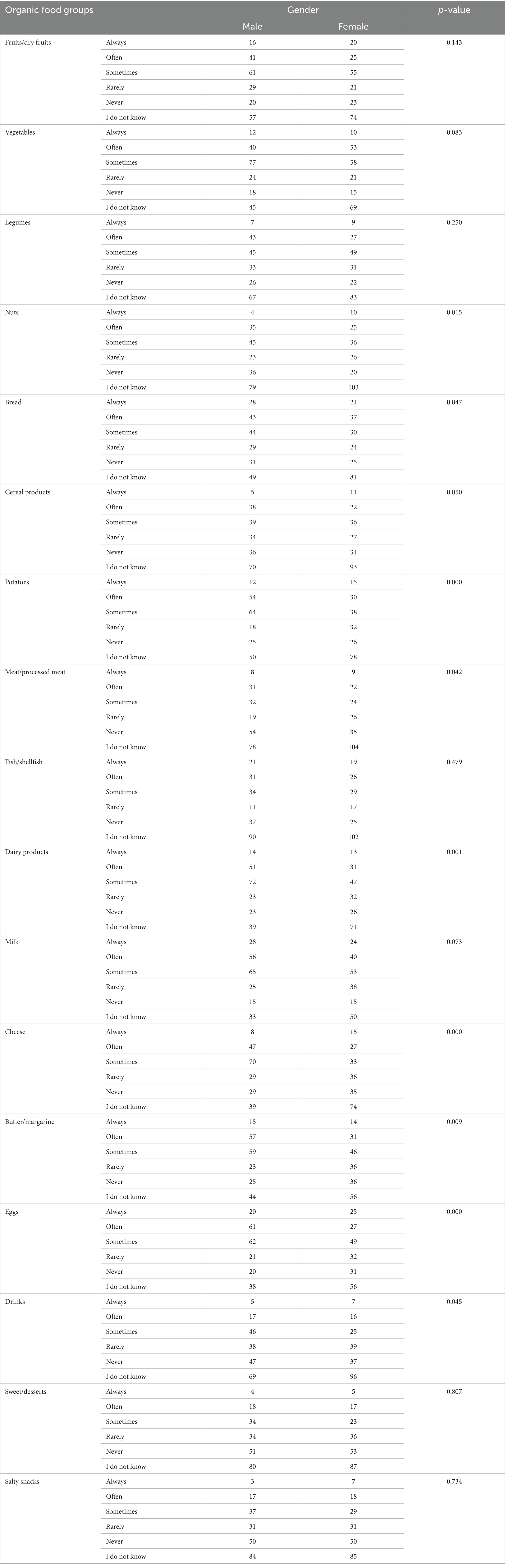

The associations between the consumption of organic food groups and gender, obtained using the chi-square test. As shown in Table 3, a significant association was revealed between potatoes, bread, nuts, eggs, meats/processed meats, dairy products, cheese, butters, drinks, and gender (p ≤ 0.05). However, no significant association are observed between gender and the other variables such as fruits, vegetables, legumes, fish/shellfish, milk, sweet/desserts and salty snacks.

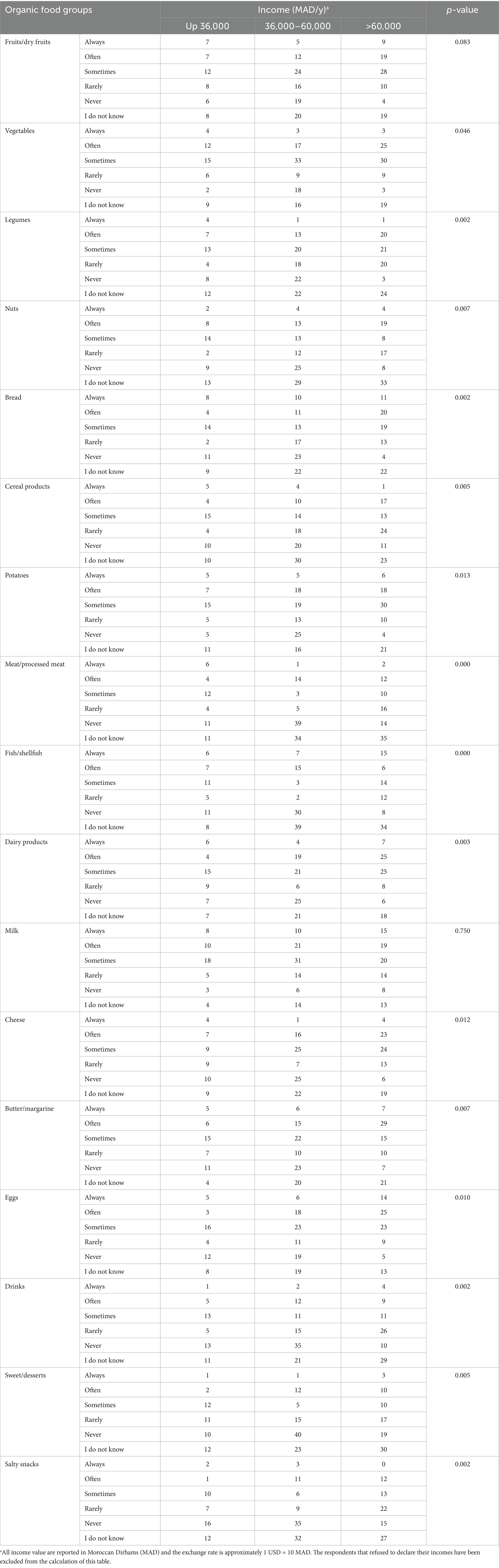

Table 4 shows the associations between organic food consumption and disposable net household income. A significant association (p ≤ 0.05) was revealed between vegetables, legumes, nuts, cheese, meat/processed meat, fish/shellfish, eggs, cereal products, bread, potatoes, dairy products, butter/margarine and income. However, there is no significant association between income and the other variables such as fruits/dry fruits, milk, sweets/desserts, and salty snacks.

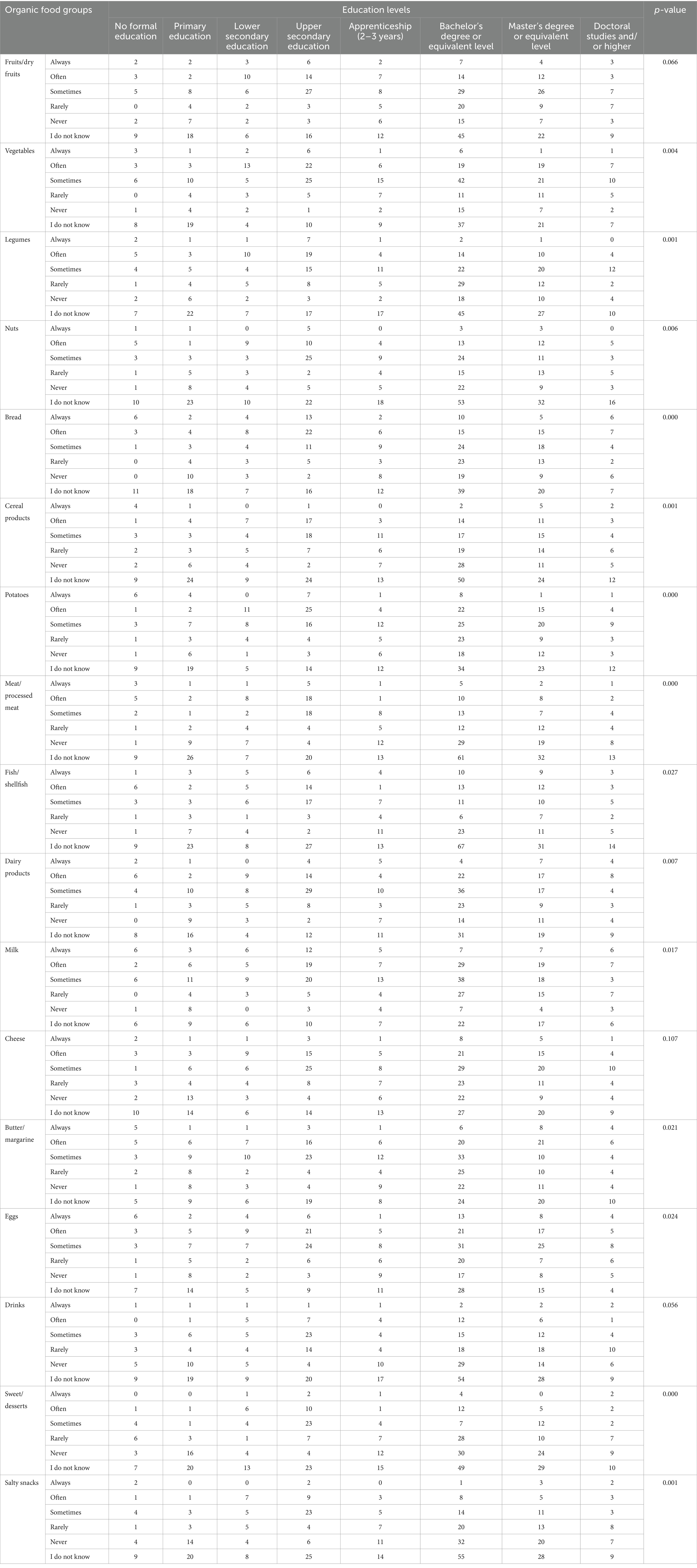

The associations between organic food consumption and education level are presented in Table 5. A significant association (p ≤ 0.05) was revealed between vegetables, legumes, nuts, meat/processed meat, fish/shellfish, eggs, cereal products, bread, potatoes, milk, dairy products, butter/margarine, desserts/sweets, salty snacks and level of education. However, there is no significant association between the level of education and the other variables such as fruits/dry fruits, cheese, and drinks.

Table 5. Organic food consumption patterns by different education levels of the surveyed population (n = 442).

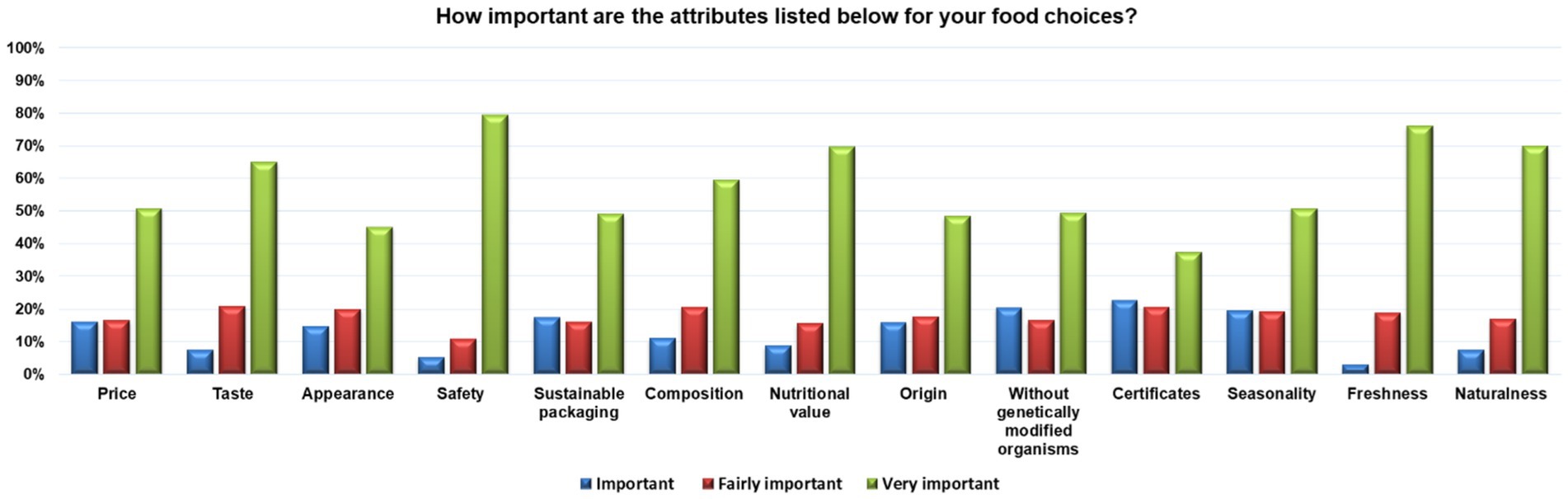

Figure 2 presents the findings on the factors affecting food choices among the surveyed population. The results indicate that “safety” is highly prioritized by households (over 75%) when making food choices, followed by “freshness,” “naturalness,” “nutritional value,” “taste,” “composition,” “price” and “seasonality” (50% or more).

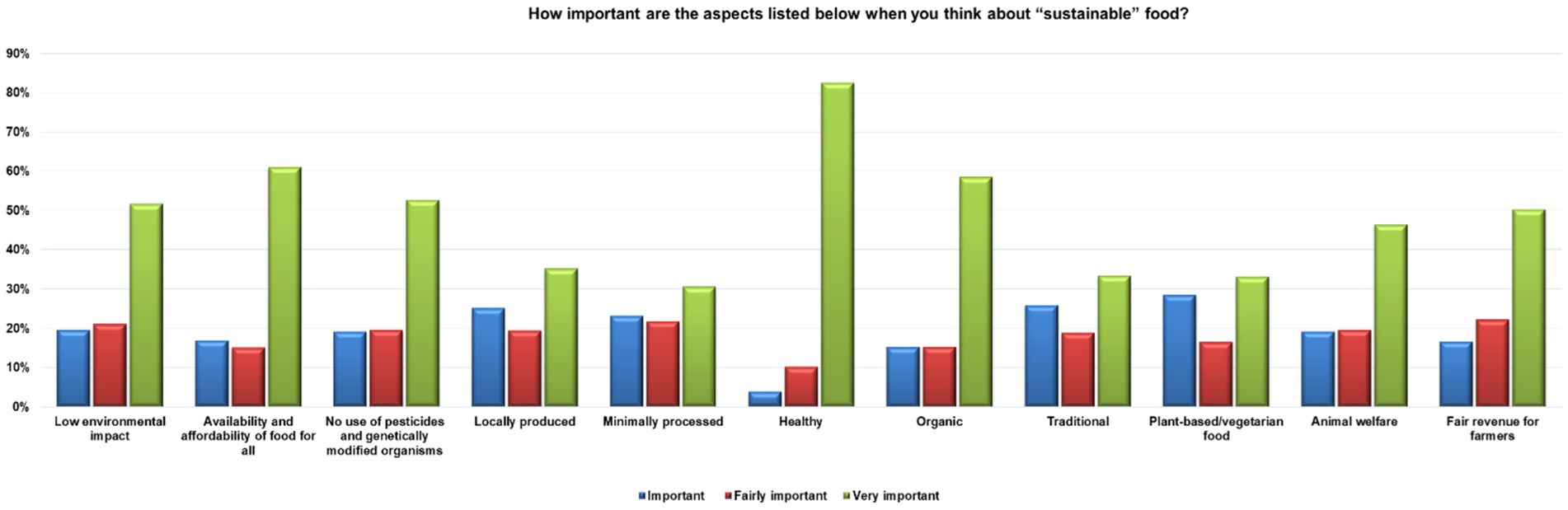

Figure 3 presents the results of the important aspects for the surveyed population when considering the concept of “sustainability.” The results indicate that “healthy,” “availability and affordability of food for all,” “organic,” “low environment impact,” and “no use of pesticides and GMOs” are very important aspects for households when they think of sustainable food (over 50%), followed by “fair revenue for farmers” and “animal welfare.”

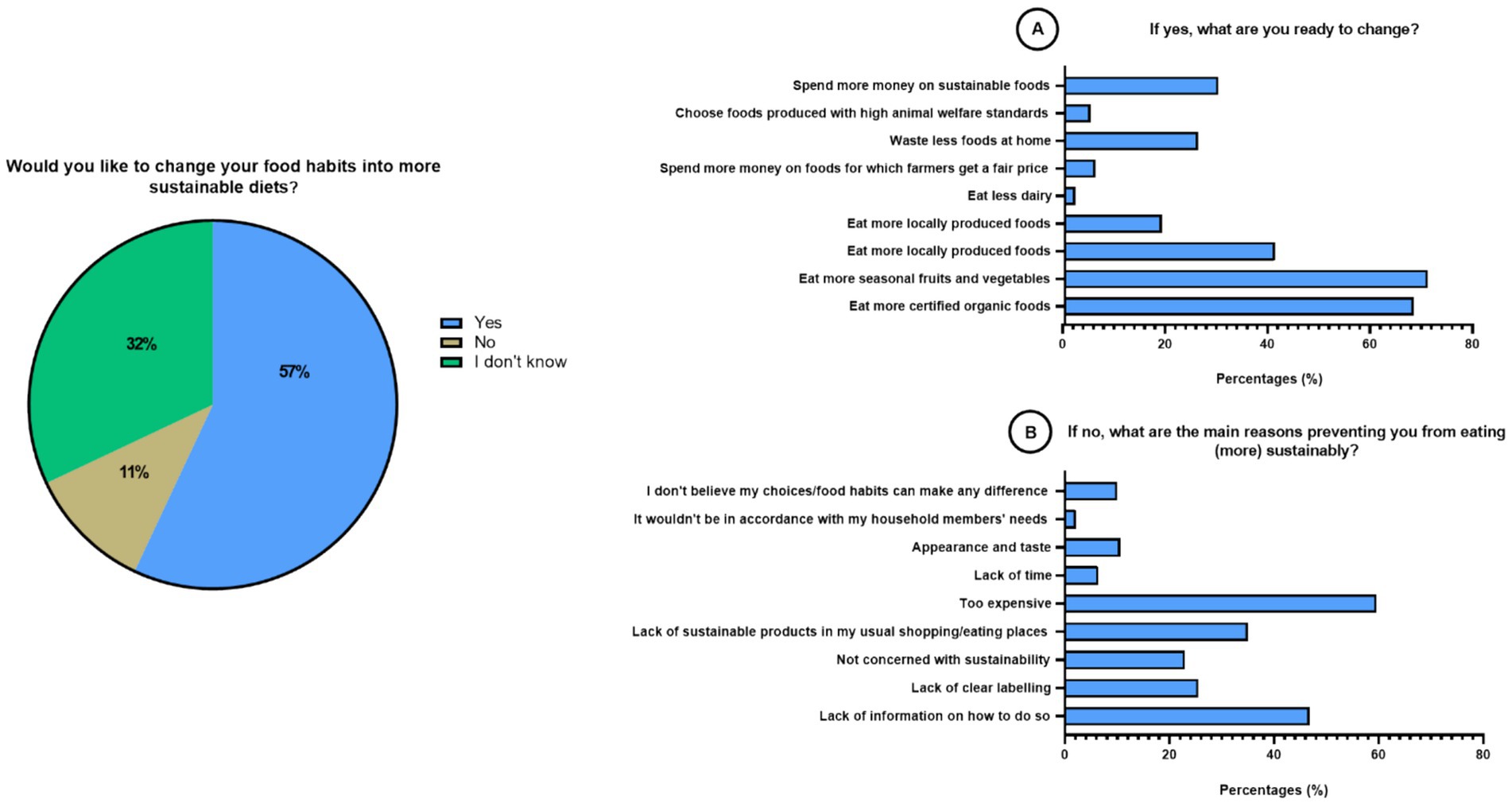

Figure 4 shows the respondents’ attitude towards changing their food habits into more sustainable diet.

Figure 4. The attitude of Kenitra’s population toward adopting more sustainable food habits (n = 442). (A) Responses from participants willing to change their food habits, indicating the specific actions they are ready to take. (B) Responses from participants unwilling to adopt sustainable food habits, highlighting the main barriers preventing such changes.

Out of all respondents, 57% expressed their willingness to change their food habits towards a more sustainable diet. However, 11% of the respondents reported that they were not interested in changing their food habits, indicating a resistance to change. Additionally, 32% of the respondents were unsure about their willingness to change their food habits, showing a lack of clarity or information about sustainable eating practices.

Figure 4A shows that 60% of the respondents who are willing to change to a more sustainable diet mentioned that they are ready to change food habits into eating more certified food, incorporating seasonal fruits and vegetables into their diets, prioritizing more locally produced food (41%), spending more on sustainable food (30%), and wasting less food at their home (26%).

As shown in Figure 4B, for the ones who do not want to change; more than 50% of households mentioned that the main reason preventing them from eating sustainably is the price (60% responded with “too expensive”), and the lack of sustainable products in their shopping/eating places (35%).

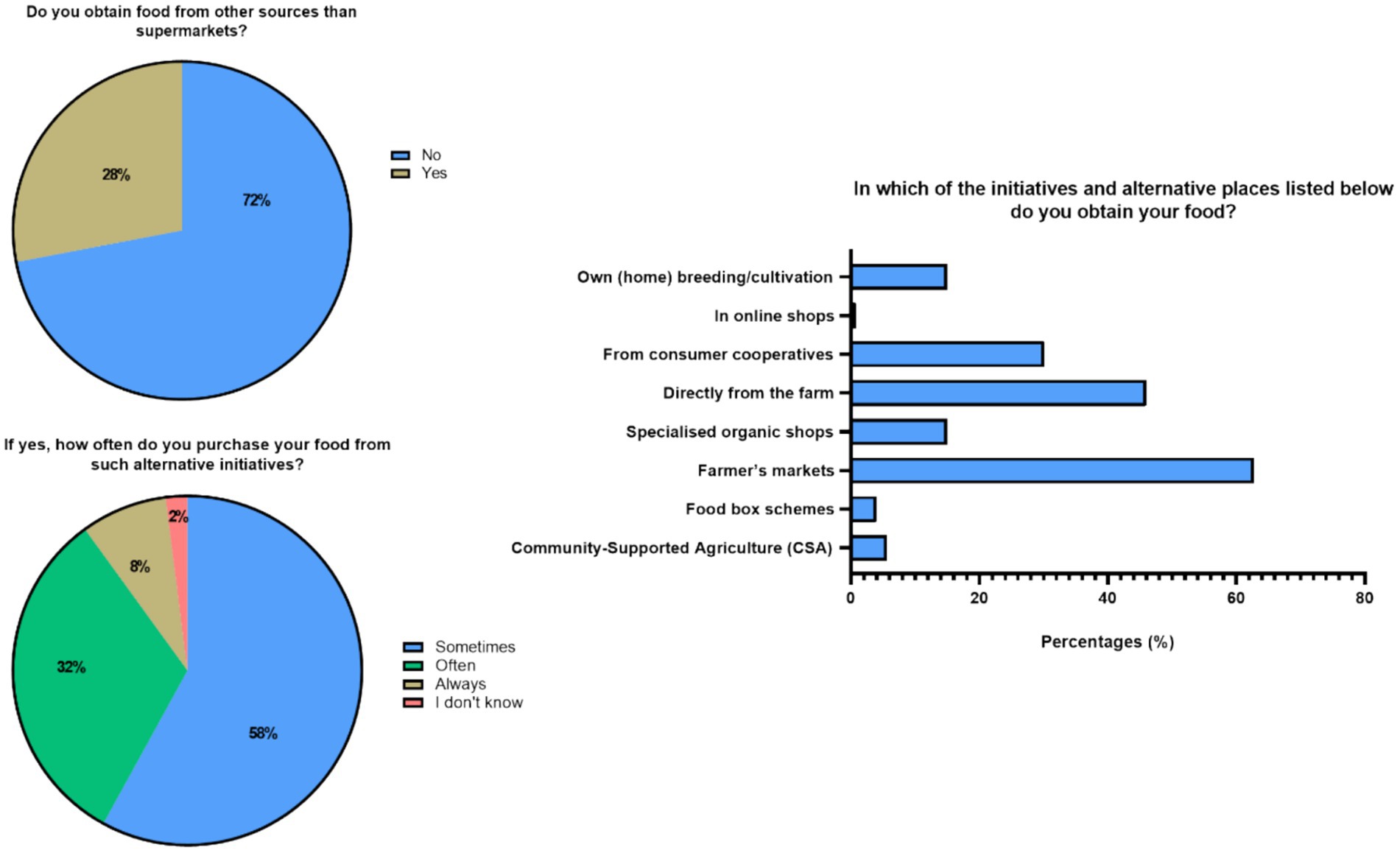

Figure 5 reveal that only 28% of the respondents indicated that they procure their food from alternative outlets beyond traditional supermarkets. While the majority of the respondents (72%) indicated that they exclusively rely on supermarkets for their food supply. Among those who partake in these alternative approaches, 58% indicated that they do so on an intermittent basis “Sometimes,” while 32% reported frequent engagements “Often.” A smaller fraction of 8% expressed a consistent commitment by claiming to “always” purchase their food from such initiatives. While only 2% confessed uncertainty regarding their purchasing patterns in this context.

Based on the findings “farmers’ markets” are the most popular choice for 60% of the respondents indicating that they obtain their food from these markets. “Directly purchasing from farms” is also a significant option, with 40% of the respondents choosing this method. “Specialized organic shops” and “consumer cooperatives” have moderate levels of participation at 15 and 30%, respectively. “Owning or cultivating food at home” has limited adoption, with only 17% of the respondents engaging in this practice. Moreover, “Online shops” are the least preferred option, with only 0.9% of the respondents utilizing them to source their food.

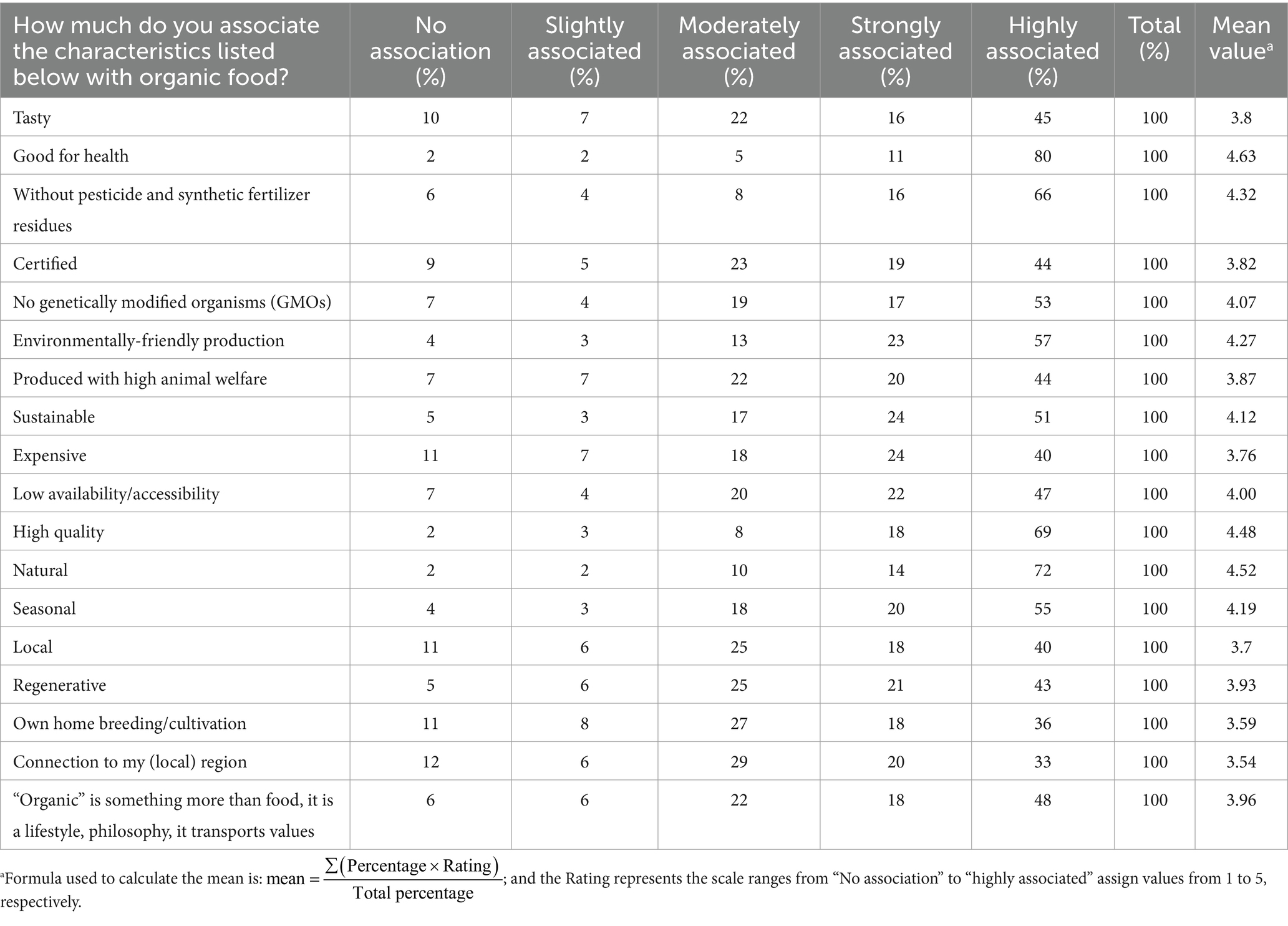

Based on the results (Table 6) more than 50% of the respondents indicated that “Good for health,” “Natural,” “High quality,” “without pesticide and synthetic fertilizer residues,” “Environmentally-friendly production,” “Seasonal,” “No genetically modified organisms (GMOs),” “Sustainable” are the characteristics most associated with organic food.

Table 6. The association of organic food with listed characteristics by the surveyed population (n = 442).

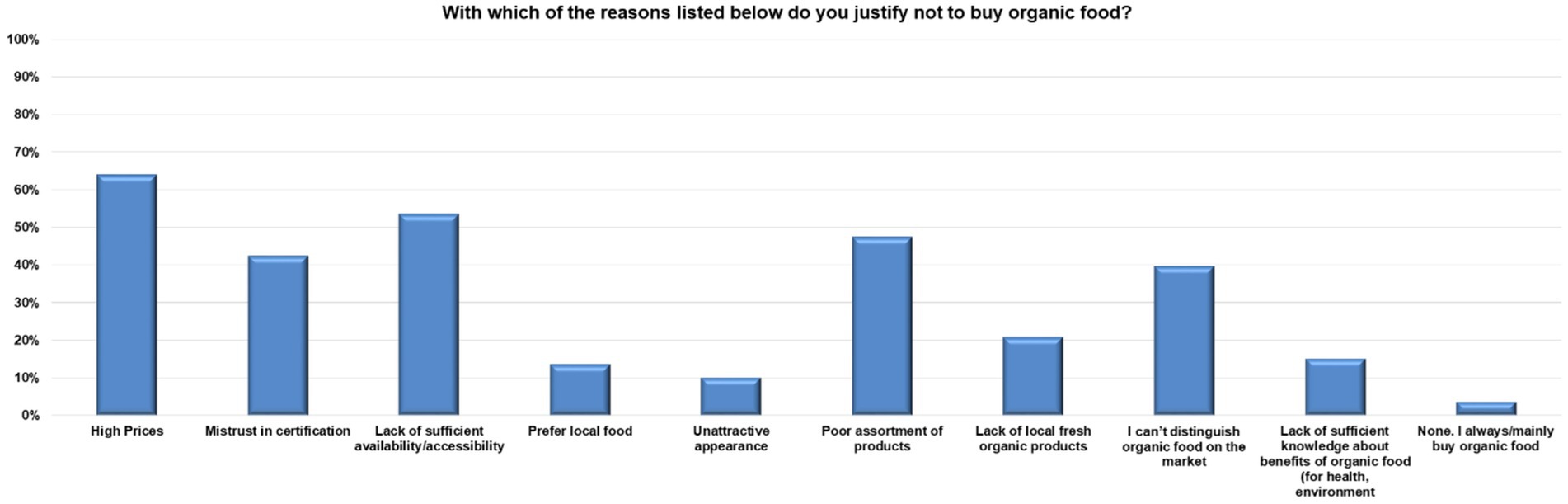

The survey results reveal several factors that influence consumers’ decisions regarding the purchase of organic food (Figure 6). The most prominent reason for not purchasing organic food appears to be “the high prices,” with 64% of the respondents justifying their choice for not buying organic food based on cost considerations. Additionally, a significant percentage (53%) indicate “availability and accessibility” as a barrier to purchasing organic food. “Mistrust in certification” (42%) and “poor assortment of products” also play a role in dissuading consumers from opting for organic options. Interestingly, the “inability to distinguish organic products in the market” (39%) and a “lack of knowledge about the benefits of organic food” (15%) contribute to the reasons for not choosing organic. However, it’s worth noting that a small minority (3%) of the respondents express unwavering commitment to buying organic food, regardless of these factors.

Figure 6. Factors that influence Kenitra consumers’ decisions regarding the non-purchase of organic food (n = 442).

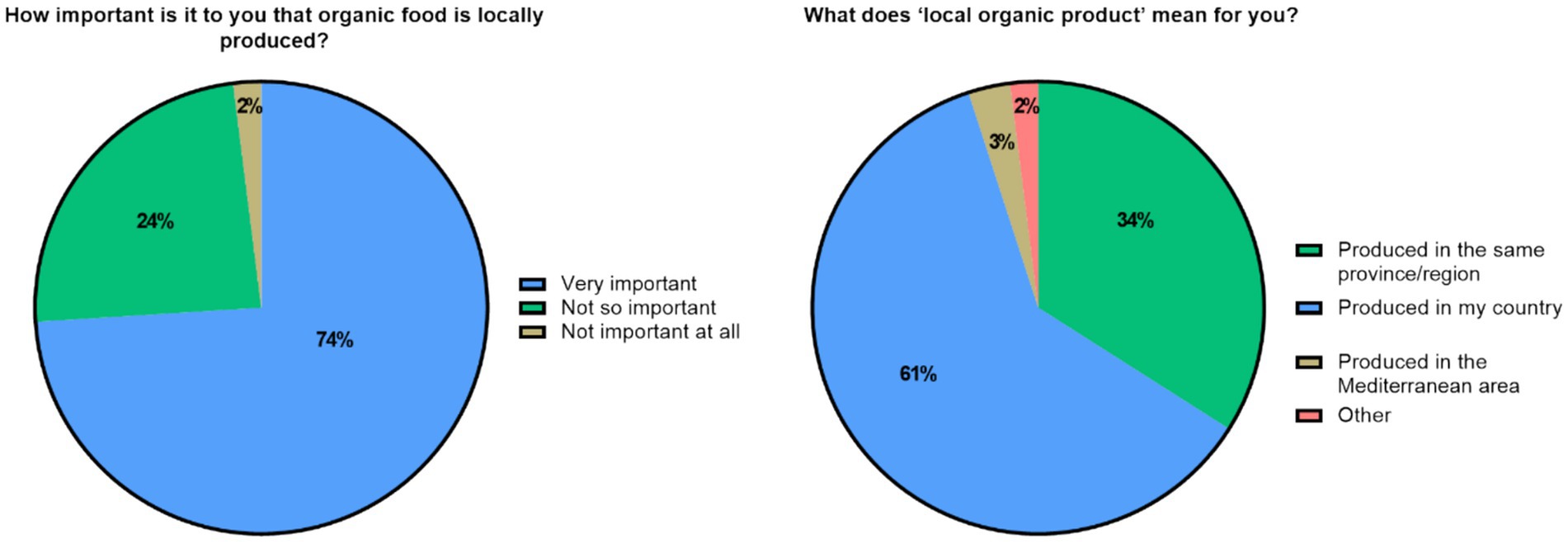

Among the participants, a significant majority corresponding to 74% indicated that it is very important to them that organic food is locally produced. Meanwhile, only a small percentage (2%) reported that it is not important at all to them that organic food is locally produced (Figure 7). For the meaning of the term “local organic product,” 61% of the participants closely associated this term with national identity. Conversely, 34% of the participants consider the term synonymous with products originating from their respective provinces or regions. A smaller percentage (3%) links “local organic product” to the Mediterranean area. The remaining 2% selected the “Other” category, indicating a variety of interpretations that extend beyond the provided options (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Importance and the meaning of “locally produced organic food” for the surveyed population (n = 442).

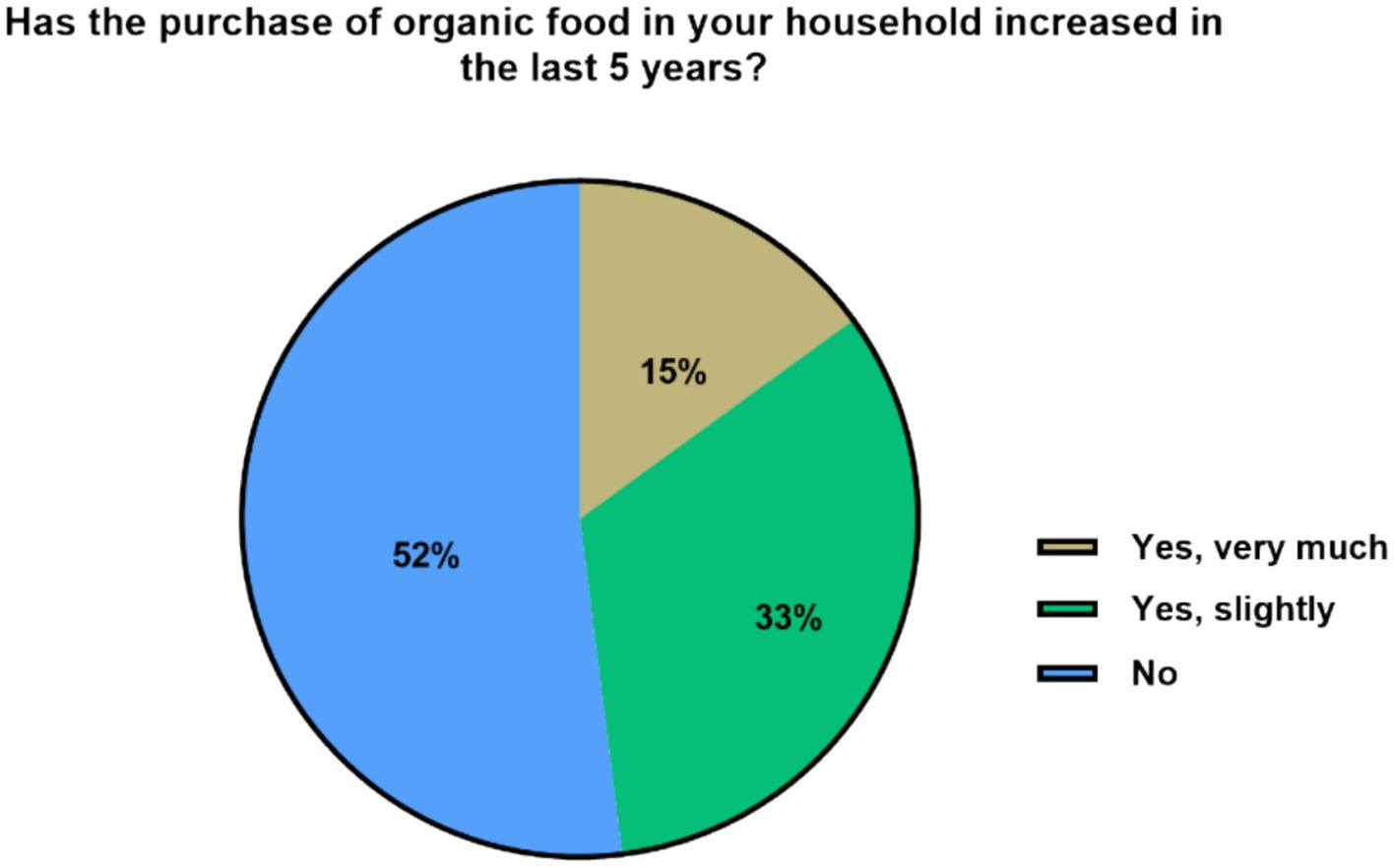

Among the respondents, only 15% reported a significant increase in the purchase of organic food in their households over the past 5 years (Figure 8). Meanwhile, 33% of the respondents reported a slight increase in the purchase of organic food over the same period. Although not as substantial as the first group, this still demonstrates a positive trend towards incorporating more organic food into their diets/shopping habits. However, the majority of the respondents, comprising nearly 52%, indicated that the purchase of organic food in their household has not increased at all over the last 5 years.

Figure 8. Status of organic food purchases in the Kenitra households over the past 5 years (n = 442).

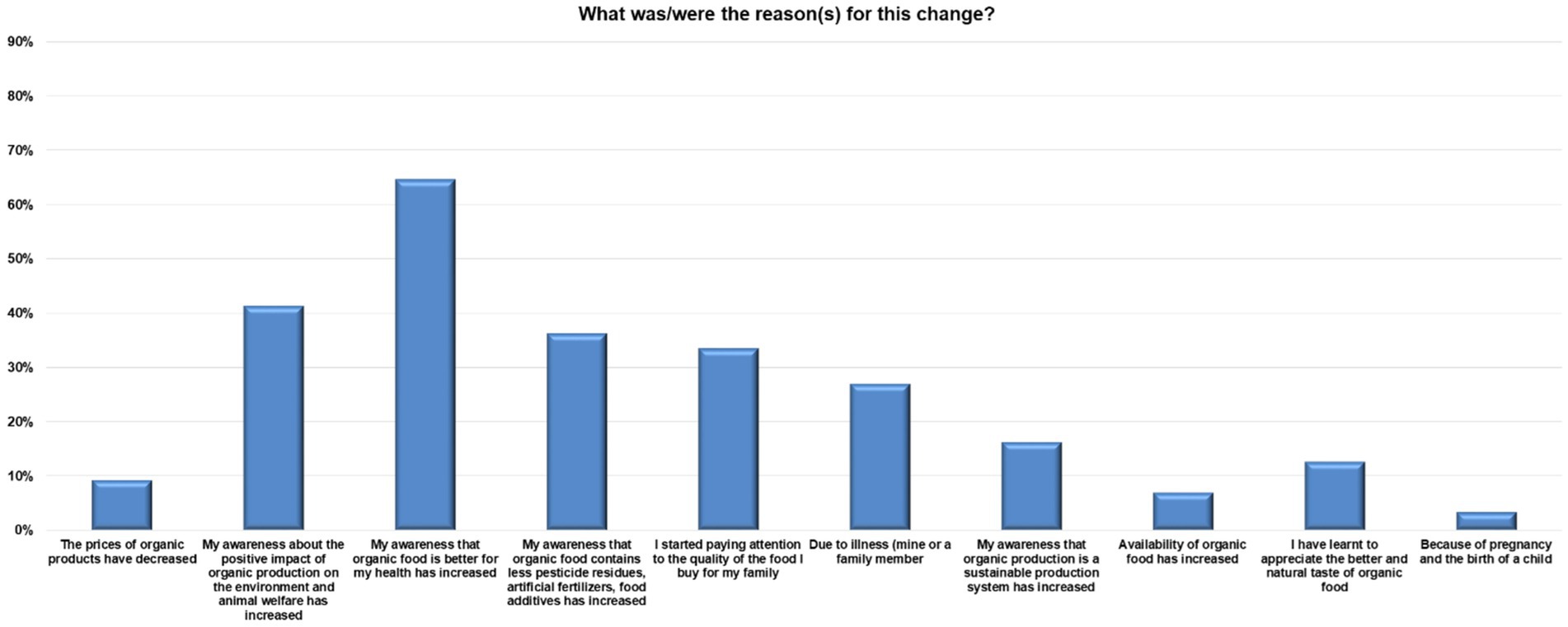

Those households who reported increased consumption of organic food over the past 5 years were further asked about the reasons behind this increase. Based on the results, 64% of the respondents stated that their awareness of the health benefits of organic food has increased (Figure 9). Other respondents have become more aware of the positive impact of organic production on the environment and animal welfare (41%). Furthermore, 36% of the respondents consider the reduced presence of pesticide residues, artificial fertilizers, and food additives as motivating factors for purchasing organic food. Another 33.5% of the respondents have started paying more attention to the quality of the food they buy for their households, making it a significant reason for the rise in organic food purchases among the majority of Kenitra households. In contrast, only 27% of the respondents cited personal or family illnesses as a reason for the increase in organic food purchases in their households.

Figure 9. Reasons contributing to the increase of organic food purchases by households in Kenitra (n = 442).

4 Discussion

The limited consumption of organic food is still a big challenge, especially for developing countries such as Morocco.

Starting from demographic characteristics and their relationship with organic food consumption, when considering the income combined with “how much of the participants’ monthly income is spent on food purchases,” a significant portion of the surveyed population falls into the 36,001–60,000 MAD/year income bracket (10 MAD ≈ 1USD), and the majority of the respondents dedicating a substantial portion of their earnings/income to food purchases (spent between 26–50% or more). This reflects the importance of food in their overall household budget and suggests that meeting basic nutritional needs is a significant financial commitment for this group. Additionally, a noteworthy 31% of the respondents allocate 10–25% of their income to food, reinforcing the idea that a reasonable portion of their financial resources is directed towards sustaining their nutritional requirements. These findings underscore the financial challenges faced by a significant segment of the surveyed population, in ensuring access to an adequate and balanced diet. Furthermore, another study carried out in Morocco (Abouabdillah et al., 2015) highlighted that the monthly food budget exceeds the level of 900 MAD in more than 65% of households composed of 4–6 members and more.

According to our findings, household income appears to have a significant association with the consumption of organic food, particularly, vegetables, legumes, nuts, cereal products, meat, fish, eggs, bread, potatoes, dairy products, butter (p ≤ 0.05). However, there was no significant associations between income and consumption of organic fruits, milk, sweets/desserts, and salty snacks. These results align with previous studies (Mohamed et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2009), which suggest that higher income significantly affect /influence organic food consumption, thinking that consumers with more financial resources often had the urge to change their food consumption pattern toward safe and more natural food options. In contrast, a study conducted in Saudi Arabia (Khattab et al., 2020) found no effect of income on organic food consumption, noting that the majority of their respondents who consumed organic foods were nutritionally educated and aware of the nutritional and health benefits of these foods, and their consumption decision were based on their belief about the health benefits and the nutritional value of these type of food rather than their income level.

Regarding the level of education, a significant associations was revealed between the consumption of various organic food groups such as vegetables, legumes, nuts, meat, fish, eggs, cereal products, bread, potatoes, milk, dairy products, butter, desserts/sweets, and salty snacks (p < 0.05) and educational level of the surveyed population. This can be explained to the fact that there is a potential link between education and organic food purchase/consumption (Dettmann and Dimitri, 2007; Gundala and Singh, 2021) found that education level affects organic food consumption and that individuals with higher levels of education are more likely to buy organic products than others. This correlation can be attributed to the fact that those with more education often have a greater understanding of the potential health and environmental benefits of organic food which can influence their consumption choices and lead to a higher likelihood of choosing organic foods over conventional alternatives.

Focusing on organic products consumption, out of 442 households, 60% consume 1–25% organic food, while 12% reported that they do not eat any organic food at all. In comparison with a study in Egypt (Mohamed et al., 2012), approximately 32% of their respondents purchase organic foods, whereas 68% of them never do. Another study in Spain (Urena et al., 2008) found that only 12% of their participants purchased organic at least twice a week and identified them as regular consumers, 42% were occasional consumers, while 46% were non-consumers. A cross-sectional Danish study (Andersen et al., 2022) found that 15% of their survey participants reported never consuming organic food, 37% exhibited a moderate level of organic food consumption, whereas just 10% displayed a high level of organic food consumption. A recent study con-ducted in three North African countries (viz. Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia) (Ben Khadda et al., 2022) found that organic products were consumed occasionally by 42.2%, regularly by 28.7%, while 5.1% of their interrogated population never consumed them at all. Only 6.1% were able to consume these products in a daily basis (Ben Khadda et al., 2022). The same study (Ben Khadda et al., 2022) mentioned that the answer to the question “How many people around you consumes organic products?” was 17.6% of respondents said they knew 1 to 3 people who consume organic products, 9.7% said they knew 3 to 5 people, while 7.4% said they knew more than 9 people.

The results of our study showed that among the households surveyed, 60% reported “milk” as their most consumed organic food, followed by vegetables, eggs, dairy products, fruits and bread. In this context, fruits and vegetables account for the largest share of organic food sales in the United States, constituting nearly 15% of fresh pro-duce sales, with milk and dairy products following as the second largest category (Willer and Lernoud, 2018; Greene et al., 2017). Not only in the U.S., many studies (Radman, 2005; Padel and Foster, 2005; Tsakiridou et al., 2008) showed organic “fruits and vegetables” as the main frequently consumed product category. This trend is mirrored in France where “fruits and vegetables” have consistently held the top spot from 2015 to 2022 among the five most consumed organic food product categories, followed by “dairy products” (Statista, 2022). However, in contrast, a study conducted in Egypt (Mohamed et al., 2012) asked purchasers to determine their most frequently consumed product categories: 36% reported that they consume medicinal and aromatic plants most often, followed by milk, dairy products, fresh vegetables and fruits; organic eggs had the lowest consumption rate in the study (Mohamed et al., 2012).

Conversely, organic sauces, sweets/desserts, fast food, salty snacks, and drinks appear to be less popular choices among the surveyed households. This result is not surprising, firstly because “organic fast food” is relatively rare in Morocco, similarly as for these food categories aforementioned (sauces, sweets, desserts, salty snacks, and drinks) most respondents are not convinced that they exist. In addition, organic food is often associated with natural and sustainable farming practices (Giri and Pokhrel, 2022; Niggli, 2015), which may not align with the fast food industry’s business model because the concept of “fast food” typically involves mass production and processed ingredients. Secondly, organic sweets, desserts and drinks are less commonly consumed because in general, these products tend to be high in sugar and unhealthy ingredients. Moreover, due to rising obesity rates and associated health risks like diabetes, some consumers are increasingly choosing lower-sugar options.

Moreover, the present study identified four categories of organic food consumers, in purpose to understand their behavior and also to take into account the gap between consumers’ behavior and their actual consumption.

These include the regular consumers, occasional consumers, non-consumers and unaware consumers. A substantial portion of the respondents integrates organic products into their consumption routine “on occasion.” This suggests a degree of flexibility in their choices, where they might alternate between organic and conventional based on availability or personal preferences. The occasional consumers category, “rarely” consuming organic products, reveals a smaller but still noteworthy segment of the population who sporadically opt for organic. This group might be influenced by factors such as cost, convenience, or limited access to organic products.

The non-consumers category, stating “never” consuming organic products, indicates a minority of individuals who consciously abstain from consuming organic altogether, potentially due to personal beliefs, taste preferences, or other considerations. The unaware consumers category, which includes those who chose the answer option “I do not know,” representing a substantial portion of this survey, suggests a lack of awareness or attention to whether the products they consume are organic or not. This could reflect a need for greater education increasing awareness and transparency regarding organic food choices.

The current study found that “safety” is highly prioritized by households (over 75%) when making food choices, followed by freshness, naturalness, nutritional value, taste, price and seasonality. Safety is a paramount concern for many consumers, especially families. When it comes to organic food, one of the key reasons people choose it is because they believe it is “safer.” Multiple studies (Bhavsar et al., 2018; Mie et al., 2017; Gomiero, 2018; Rizzo et al., 2020; Tomás-Barberán and Gil, 2008; Drewnowski and Monsivais, 2020) confirmed that consumers’ food choice is based on the assertion that food produced organically is healthier than conventionally produced one. In the same vein, consumers perceive organic food as a safer alternative due to their belief that its consumption lessens the chances of being exposed to illnesses associated with pesticide residues (Bhavsar et al., 2018). On the opposite, a study conducted in Morocco about factors influencing the choice to buy food products (Gharbi et al., 2021) found that 66.5% of consumers prioritize product quality, while 22% prioritize the price at the different points of purchase; in the same study they found that 69.7% of the respondents are interested in purchasing products bearing the “ISO certified” label (Gharbi et al., 2021). Another study (Drewnowski and Monsivais, 2020) considers taste, cost, and convenience the main drivers of food choice and food consumption patterns.

The survey results reveal that “healthy,” “availability and affordability of food for all,” “organic,” “low environment impact” and “no use of pesticides and GMOs” are highly important to Kenitra households when they think of sustainable food. These results emphasize the multi-faceted nature of sustainability in the eyes of the Kenitra households, viewing it as a multidimensional concept, extending beyond environmental considerations and encompassing health, accessibility, equitable distribution, organic farming, and ethical food production.

The current study results revealed that 57% of the participants expressed their willingness to change to more sustainable diet, by incorporating seasonal fruits and vegetables into their diets (70% of households), eating more organically certified food (68%), prioritizing more locally produced food (41%), spending more on sustainable food (30%), and wasting less food at their home (26%). These results remain positive because what concerns changing dietary consumption may be a real challenge in the whole world (Joyce et al., 2014; Macdiarmid, 2013). The definition of a sustainable diet is complex and encompasses multi-faceted (Whittall et al., 2023), and this complexity may be confusing and hard to implement. As a result, willingness to change in some consumers and resistance in others has been reported (Hartmann and Siegrist, 2017; Vanhonacker et al., 2013). A recent research in the UK (Whittall et al., 2023) showed that participants are willing to make changes to more sustainable diet, but there was uncertainty about the actions they could take. In the same study (Whittall et al., 2023), participants expressed a greater interest in minor changes that could be implemented with limited cost or effort. Another survey of 3,000 adults in the UK (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 2011) unveiled that only 15% of individuals would change their diet for the benefit of the environment while other studies (van Bussel et al., 2022) revealed that consumers stated their intent to alter towards a more environmentally sustainable diet only for benefiting their own personal health.

However, 10.5% of our respondents reported that they are not interested in changing their food habits, indicating a resistance to change; they mentioned that the main reason preventing them from eating sustainably is the price (60% responded by “too expensive”). In accordance with the present result, a recent research conducted in Malaysia (Cheah and Aigbogun, 2022), revealed that “the high price” is the biggest barrier for eco-conscious consumers. The same reasoning was announced by many studies (Torres-Ruiz et al., 2018; Petrescu et al., 2017; Bryla, 2016; Hamzaoui and Zahaf, 2008; Padel and Foster, 2005; Marian et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2010; Aygen, 2012), carried out across various countries including European and non-European countries which have consistently identified “the high price” as a main obstacle to organic food consumption. The second reason was the lack of sustainable products in their shopping/eating places (35% of respondents). That makes sense because if respondents believe that a specific organic food item is hard to locate and purchase, chances that they will lose interest are high, as they may not be willing to make the required efforts to acquire the food (Cheah and Aigbogun, 2022).

Regarding the source of food purchase, the present research, found that 72% of the respondents rely on supermarkets for their food supply, while only 28% of them indicated that they procure their food from alternatives such as farmers’ markets, food box schemes and community-supported-agriculture; 32% of them reported frequent engagements “Often,” and 58% indicated that they do it “Sometimes.” This inclination towards diversifying food procurement methods signifies a growing awareness and preference for sustainable and locally-sourced options.

Moreover, the present study revealed that “Farmers’ markets” are the most popular alternative choice to obtain food for 60% of those who stated “alternatives” as a source of their food purchase. This reflects a strong preference for fresh, locally-sourced produce from the population and a growing desire among consumers to connect with the source of their food, support local farmers, and access seasonal, fresh products. Furthermore, “farmers’ markets” often offer a wide variety of products, including fruits, vegetables, meats, etc. which makes them an attractive choice for many consumers. In the same context, a study conducted in Morocco (Abouabdillah et al., 2015) confirmed that the “Souk” or traditional market occupies the first rank in shopping places with a percentage of 37% due to the fact that the majority of consumers search for good quality products with low prices.

Souks/traditional markets are followed by purchasing food “directly from farms” that reinforces the appeal of farm-to-table practices. This method allows consumers to establish a direct relationship with producers, potentially ensuring product quality and traceability. It’s likely that individuals who prefer this option value transparency and trust in their food sources. On the opposite, the same precedent study revealed that only 2% of the participants opt for farms as a place for food shopping, explaining it by the fact that it is an unusual habit, especially for people from big cities (Abouabdillah et al., 2015). In the same context, a study carried out in Egypt (Mohamed et al., 2012) found that only 6% of their participants purchase organic food directly from farms, while the majority buy it either from super-markets (58%) or from hypermarkets (36%) (Mohamed et al., 2012).

The reason behind the lower adoption of “Organic shops” as a choice to obtain food is due to the fact that these shops typically offer a range of certified organic and ecofriendly products, which can be more expensive, according to the beliefs of some consumers.

In the same context, low usage of “online shops” could be attributed to several factors such as product quality, shipping costs, and computer illiteracy (especially among elders) and a preference for in-person shopping, especially when it comes to selecting fresh produce. Mistrust in online food shopping platforms and logistical challenges may also be contributing factors.

In this research, we found that organic food is strongly associated with positive attributes like tastiness, health benefits, environmental friendliness, and high quality. However, it is also associated with higher costs and limited accessibility.

Generally, most studies reported that the majority of consumers believe that organic food is more sustainable, healthier, safer, eco-friendlier, of higher quality, cleaner, tastier, and more nutritious (Bryla, 2016; Mkhize and Ellis, 2020; Hughner et al., 2007; Magistris and Gracia, 2008; Bezawada and Pauwels, 2013).

The current study showed that, “high prices,” “availability/accessibility,” “poor assortment of products in shopping place” and “mistrust in certifications” emerged as the main barriers hindering households from purchasing organic products. They are followed by the “inability to distinguish organic products in the market,” while only 15% of the participants mentioned the lack of knowledge about the benefits of organic food as an obstacle to buying it. Similarly, a recent study carried out in Morocco (Ben Khadda et al., 2022) confirmed that the higher price and the non-availability of organic products were the major criteria that have a negative impact on organic purchases in Morocco with almost 55% of their respondents tending to agree (Ben Khadda et al., 2022). These results align with another study conducted in Poland (Bryla, 2016) that also defines the high price as the main critical barrier to the development of organic food purchases, followed by insufficient consumer aware-ness, low availability of organic products, short expiry dates and low visibility in the shop (Bryla, 2016). Price was and still is a worldwide major deterrent for a considerable portion of consumers, potentially limiting the adoption of organic products (Mohamed et al., 2012; Tandon et al., 2020; Buder et al., 2014). On the opposite, a study conducted in Bangladesh (Iqbal, 2015) showed that 60% of their organic buyers do not see the price as a limiting factor, while only 29% mention it as a barrier to not purchasing organic (Iqbal, 2015). Another study carried out in Eastern Croatia (Ham et al., 2016) represented “The negative attitudes toward organic food” as the biggest barrier that largely prevents people’s intention to purchase organic food; such as “organic food tastes worse,” “organic food also contains artificial tastes and additives” and “organic food does not seem attractive to me” (Ham et al., 2016). Availability is another factor that encourages the purchase of organic foods; consumers do not want to spend time searching for organic products, and they prefer readily available products (Caldwell et al., 2009).

It is worth noting that a significant portion of the participants in this study willing to pay more for organic food products. For this category, the price is not a hurdle. This can be attributed to the fact that health concern is the first motivation for those who are willing to pay an extra, premium price for organic food (Mohamed et al., 2012). A study conducted in Kathmandu Valley (Nepal) (Aryal et al., 2009) found that 39% of their respondents perceive that the extra cost for organic products is reasonable, whereas 27% considered it too high. The same study found that 58% of the consumers are willing to pay 6–20% price premium for organic products (Aryal et al., 2009).

Regarding the importance of locally produced organic food, our study revealed that 74% of the respondents indicate that it is very important to them that organic food is locally produced. This reflects a strong preference of Kenitra consumers for sup-porting local farmers and reducing the environmental impact associated with long-distance food transportation, as well as valuing the freshness and sustainability associated with locally sourced organic products. It was also noted that Moroccans are ready to support their country’s economy by leaning more towards the purchase of local products rather than imported ones (Morocco World News, 2021). According to a recent study concerning the consumption of local products in Morocco (Bouallala, 2018), olive oil and dates rank as the most frequently consumed local products. Another research conducted in Morocco (Raif and Abdellatif, 2021) confirmed that the majority of the participants clearly prefer national and regional products; these products are not only consumed for their concrete benefits but also due to hedonistic values, by purchasing or consuming regional products, consumers identify with the region of these products (Raif and Abdellatif, 2021).

However, 2% of the survey participants reported that it is not important at all to them that organic food is locally produced. This group may have different priorities or fewer considerations when it comes to locality and sourcing of their food; this could be due to the fact that Moroccan consumers have abundant options of food products, whereby they have to select between too many types of foreign or local ones (Raif and Abdellatif, 2021) or perhaps consumers’ scepticism of these products. According to the president of the Professional Association of Moroccan Brands, there is a certain mistrust towards local products: “The negative perception of Made in Morocco products comes from several misconceptions, for example, premium merchandise is intended for export with low prices while the second choice would be reserved for the local market with high prices” (AgriMaroc, 2020a,b).

Concerning the current state of organic food purchases in Kenitra households, we found that 15% of the respondents increased the purchase of organic food in their household over the past 5 years, while 33% cited a slight increase in the purchase of organic food. Although the growth rate is still not that big, but still demonstrates a positive trend toward incorporating more organic food into diets.

Based on the results, the rise in organic food purchases in Kenitra households appears slow but still positive. This increase is primarily due to the fact that 64% of the respondents are more aware of the health benefits and positive environmental impact of organic food. The reduced presence of pesticide residues, artificial fertilizers, and food additives also serve as motivating factors for many of consumers. Furthermore, personal or family illnesses have prompted many Kenitra households to opt for organic food, contributing to the overall increase in its consumption in the past 5 years.

However, 52% of the respondents indicated that the purchase of organic food in their household has not increased at all over the 5 years. This suggests that organic food consumption has remained relatively stable or unchanged for this group for various reasons that could be budget constraints, limited availability, etc. as mentioned before.

The main limitations of the study relate to the study’s sample size and representativeness as well as the potential for response bias. As for the sample size, the study would be more valuable if a broader survey takes place, considering a larger and more diverse sample. This could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the community’s attitudes and behaviors toward organic food. It is like this study caught a glimpse of a bigger picture but needs a broader survey, encompassing more places, and more people from various socioeconomic backgrounds (ranging from affluent urban areas to rural regions) in order to find patterns for various socioeconomic groups and settings. The potential for response bias, wherein participants may offer socially desirable answers influenced by current trends or public opinion, could have impacted the accuracy of the results regarding the levels of interest and consumption of organic products in the region, and also other aspects like important sustainability characteristics, food attributes etc. These limitations highlight the need for more extensive and diverse research approaches in future studies.

5 Conclusion

To summarize, the findings from this article shed light on the evolving landscape of organic food consumption in Kenitra (north-western Morocco).

The study has unveiled a significant interest in organic products, with the majority of the respondents demonstrating a willingness to embrace healthier dietary choices. Safety, freshness, and naturalness are top priorities for consumers when making food decisions, emphasizing their concern for quality and health.

More than half of the Kenitra households consume organic food in the range of 1–25%; milk emerges as the leading organic food choice, with a substantial percentage of the population opting for it, followed by vegetables, eggs, dairy products, fruits, and bread. However, it is worth noting that some food categories (e.g., sauces, sweets, and fast food) appear to be less popular in their organic variants.

The preference for locally produced organic food is strong among the surveyed population, underlining the importance of supporting local agriculture and organic farming practices. Despite this growing trend, challenges, such as the perceived high price of organic products, and the limited availability and variety of organic products in shopping places, remain hurdles for households to adopt organic food.

Overall, the results indicate an encouraging shift towards healthier food choices in Kenitra. But the study also emphasizes the importance of raising more awareness regarding organic food within this population. Stakeholders and policymakers in the organic food industry have an opportunity to address challenges and work towards making organic locally-sourced food more accessible, convenient and affordable with more suitable prices, thus further promoting its consumption not only in the region but in the entire country.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The study was conducted with proper authorization from the Regional Directorate of Health in the Rabat-Salé-Kénitra region and approved by the regional Ethics Committee (CERB05/22). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. CB: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. ZH: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. SaB: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Software, Data curation. AB: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. HB: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. SuB: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology. DŚ-T: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology. PP: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology. CS: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology. LR: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology. LS-n: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Project administration, Methodology. YA: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. These results have been achieved within the SysOrg project “Organic agro-food systems as models for sustainable food systems in Europe and Northern Africa”. The authors acknowledge the financial support for this project provided by transnational funding bodies, partners of the H2020 ERA-NETs SUSFOOD2 and CORE Organic Cofunds, under the Joint SUSFOOD2/CORE Organic Call 2019, with national funding from Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture, Federal Organic Farming Program (Funding Reference No. 2819OE153)—Germany, the Italian Ministry of Agriculture, Food Sovereignty and Forests (Grant No. 9386854 dated 17.12.2020), the Ministry of Higher Education, Scientific Research and Innovation—Morocco (Grant Convention No. 4 dated 03.11.2020), the National Centre for Research and Development—NCBR, Poland (Grant No. SF-CO/SysOrg/6/2021), the Green Development and Demonstration Programme (GUDP) under the Danish Ministry of Environment and Food (Grant No. 34009-20-1694).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2024.1413498/full#supplementary-material

References

Abouabdillah, A., Capone, R., El Youssfi, L., Debs, P., Harraq, A., El Bilali, H., et al. (2015). Household food waste in Morocco: an exploratory survey. Proceedings of the VI International Scientific Agriculture Symposium “Agrosym 2015”. 1353–1360.

AgriMaroc . (2020a). La consommation alimentaire locale est désormais plus pertinente que jamais. Available at: https://www.agrimaroc.ma/consommation-alimentaire-locale/. (Accessed March 15, 2024)

AgriMaroc . (2020b). Maroc: La Consommation de Produits Bio Gagne du terrain. Available at: https://www.agrimaroc.ma/maroc-consommation-produits-bio. (Accessed March 10, 2024)

Andersen, J. L. M., Frederiksen, K., Raaschou-Nielsen, O., Hansen, J., Kyrø, C., Tjønneland, A., et al. (2022). Organic food consumption is associated with a healthy lifestyle, socio-demographics and dietary habits: a cross-sectional study based on the Danish diet, cancer and health cohort. Public Health Nutr. 25, 1543–1551. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021001270

Aryal, K., Chaudhary, P., Pandit, S., and Sharma, G. (2009). Consumers’ willingness to pay for organic products: a case from Kathmandu Valley. J. Agric. Environ. 10, 15–26. doi: 10.3126/aej.v10i0.2126

Aygen, F. G. (2012). Attitudes and behavior of Turkish consumers with respect to organic foods. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 3, 262–273.

Azizi, A., Achak, D., Aboudi, K., Saad, E., Nejjari, C., Nouira, Y., et al. (2020). Health-related quality of life and behavior-related lifestyle changes due to the COVID-19 home confinement: dataset from a Moroccan sample. Data Brief 32:106239. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2020.106239

Ben Khadda, Z., Ezrari, S., Radouane, N., Boutagayout, A., El Housni, Z., Lahmamsi, H., et al. (2022). Organic food consumption and eating habit in Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. Open Agric. 7, 21–29. doi: 10.1515/opag-2022-0064

Bezawada, R., and Pauwels, K. (2013). What is special about marketing organic products? How organic assortment, price, and promotions drive retailer performance. J. Mark. 77, 31–51. doi: 10.1509/jm.10.0229

Bhavsar, H., Tegegne, F., Baryeh, K., and Illukpitiya, P. (2018). Attitudes and willingness to pay more for organic foods by Tennessee consumers. J. Agric. Sci. 10, 33–37. doi: 10.5539/jas.v10n6p33

Boobalan, K., and Nachimuthu, G. S. (2020). Organic consumerism: a comparison between India and the USA. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 53:101988. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101988

Bouallala, Y. (2018). “L’attitude du consommateur marocain vis-à-vis des produits de terroir: Par approche des valeurs personnelles” in Thèse (Maroc: Université Abdelmalek Essaâdi).

Bryla, P. (2016). Organic food consumption in Poland: motives and barriers. Appetite 105, 737–746. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.07.012

Buder, F., Feldmann, C., and Hamm, U. (2014). Why regular buyers of organic food still buy many conventional products: product-specific purchase barriers for organic food consumers. Br. Food J. 116, 390–404. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-04-2012-0087

Caldwell, E. M., Kobayashi, M. M., Dubow, W., and Wytinck, S. (2009). Perceived access to fruits and vegetables associated with increased consumption. Public Health Nutr. 12, 1743–1750. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008004308

Cheah, W. K., and Aigbogun, O. (2022). Exploring attitude-behavior inconsistencies in organic food consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Klang Valley, Malaysia. Clean. Responsible Consum. 7:100077. doi: 10.1016/j.clrc.2022.100077

ConsoNews . (2023). Trouver du bio, c’est encore une galère !. Available at: https://consonews.ma/48650.html. (Accessed February 10, 2024)

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (2011). “Attitudes and behaviors around sustainable food purchasing” in Report (SERP 1011/10) (London: Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs).

Dettmann, R., and Dimitri, C. (2007). Who’s buying organic vegetables? Demographic characteristics of US consumers. J. Food Distrib. Res. 16, 49–62. doi: 10.1080/10454440903415709

Drewnowski, A., and Monsivais, P. (2020). “Taste, cost, convenience, and food choices” in Present knowledge in nutrition. 11th ed (London: Academic Press), 185–200.

El Bilali, H., Ben Hassen, T., Baya Chatti, C., Abouabdillah, A., and Alaoui, S. B. (2021). Exploring household food dynamics during the COVID-19 pandemic in Morocco. Front. Nutr. 8:724803. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.724803

Gharbi, L., Guennouni, M., and Aouane, M. (2021). Factors influencing the choice to buy food products in Morocco. E3S Web Conf. 234:00035. doi: 10.1051/e3sconf/202123400035

Giri, D., and Pokhrel, S. (2022). Organic farming for sustainable agriculture: a review. Russ. J. Agric. Socio-Econ. Sci. 130, 23–32. doi: 10.18551/rjoas.2022-10.03

Gomiero, T. (2018). Food quality assessment in organic vs. conventional agricultural produce: findings and issues. Appl. Soil Ecol. 123, 714–728. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2017.10.014

Greene, C., Ferreira, G., Carlson, A., Cooke, B., and Hita, C. (2017). Growing organic demand provides high-value opportunities for many types of producers. USDA ERS Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2017/january-february/growing-organic-demand-provides-high-value-opportunities-for-many-types-of-producers/#. (Accessed February 6, 2017)

Gundala, R. R., and Singh, A. (2021). What motivates consumers to buy organic foods? Results of an empirical study in the United States. PLoS One 16:e0257288. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257288

Ham, M., Pap Vorkapić, A., and Bilandžić, K. (2016). Perceived barriers for buying organic food products. 18th International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development –“Building Resilient Society”. Zagreb, Croatia: 9–10 December, 2016. 162–174.

Hamzaoui, L., and Zahaf, M. (2008). Decision-making process of community organic food consumers: an exploratory study. J. Consum. Mark. 25, 95–104. doi: 10.1108/07363760810858837

Hartmann, C., and Siegrist, M. (2017). Consumer perception and behavior regarding sustainable protein consumption: a systematic review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 61, 11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2016.12.006

Hughner, R. S., McDonagh, P., Prothero, A., Shultz, C. J., and Stanton, J. (2007). Who are organic food consumers? A compilation and review of why people purchase organic food. J. Consum. Behav. 6, 94–110. doi: 10.1002/cb.210

Iqbal, M. (2015). Consumer behavior of organic food: a developing country perspective. Int. J. Mark. Bus. Commun. 4, 59–68. doi: 10.21863/ijmbc/2015.4.4.024

Joyce, A., Hallett, J., Hannelly, T., and Carey, G. (2014). The impact of nutritional choices on global warming and policy implications: examining the link between dietary choices and greenhouse gas emissions. Energy Emiss. Control Technol. 2, 33–43. doi: 10.2147/EECT.S58518

Kakaei, H., Nourmoradi, H., Bakhtiyari, S., Jalilian, M., and Mirzaei, A. (2022). “Effect of COVID-19 on food security, hunger, and food crisis” in COVID-19 and the Sustainable Development Goals (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 3–29.

Khattab, R. Y., Al Ammar, W. A., and Purayidathil, T. S. (2020). Consumers’ knowledge and perception towards organic foods: a cross-sectional study. European J. Nutr. Food saf. 12, 112–124. doi: 10.9734/ejnfs/2020/v12i1030308

L’agriculture bio dans le monde . (2020). Available at: https://www.agencebio.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Carnet_Monde_2020-1.pdf. (Accessed February 10, 2024)

Lindgren, E., Harris, F., and Dangour, A. D. (2018). Sustainable food systems—a health perspective. Sustain. Sci. 13, 1505–1517. doi: 10.1007/s11625-018-0586-x

Macdiarmid, J. (2013). Is a healthy diet an environmentally sustainable diet? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 72, 13–20. doi: 10.1017/S0029665112002893

Magistris, T., and Gracia, A. (2008). The decision to buy organic food products in southern Italy. Br. Food J. 110, 929–947. doi: 10.1108/00070700810900620

Marian, L., Chrysochou, P., Krystallis, A., and Thogersen, J. (2014). The role of price as a product attribute in organic food context: an exploration based on actual purchase data. Food Qual. Prefer. 37, 52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2014.05.001

Mie, A., Andersen, H. R., Gunnarsson, S., Kahl, J., Kesse-Guyot, E., Rembiałkowska, E., et al. (2017). Human health implications of organic food and organic agriculture: a comprehensive review. Environ. Health 16:111. doi: 10.1186/s12940-017-0315-4

Ministère de l’agriculture . (2023). Agriculture Biologique: 2023. Available at: https://www.agriculture.gov.ma/fr/filiere/le-bio#block_text_media-0. (Accessed November 10, 2023)

Ministry of Economy and Finance (2019). Le Secteur Agricole Marocain: Tendances Structurelles, Enjeux et Perspectives de Développement. Rabat, Morocco: Ministry of Economy and Finance, Direction des Etudes et des Prévisions Financières.

Mkhize, S., and Ellis, D. (2020). Creativity in marketing communication to overcome barriers to organic produce purchases: the case of a developing nation. J. Clean. Prod. 242:118415. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118415

Mohamed, M. A., Chymis, A., and Shelaby, A. A. (2012). Determinants of organic food consumption in Egypt. Int. J. Econ. Bus. Model. 3, 183–191.

Morocco World News . (2021). Study reveals Moroccans are ready to support local brands. Available at: https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2021/09/344648/study-reveals-moroccans-are-ready-to-support-local-brands. (Accessed March 12, 2024)

Naseer, S., Khalid, S., Parveen, S., Abbass, K., Song, H., and Achim, M. V. (2023). COVID-19 outbreak: impact on global economy. Front. Public Health 10:1009393. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1009393

Niggli, U. (2015). Sustainability of organic food production: challenges and innovations. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 74, 83–88. doi: 10.1017/S0029665114001438

Olson, E. L. (2017). The rationalization and persistence of organic food beliefs in the face of contrary evidence. J. Clean. Prod. 140, 1007–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.005

Padel, S., and Foster, C. (2005). Exploring the gap between attitudes and behavior: understanding why consumers buy or do not buy organic food. Br. Food J. 107, 606–625. doi: 10.1108/00070700510611002

Petrescu, D. C., Petrescu-Mag, R. M., Burny, P., and Azadi, H. (2017). A new wave in Romania: organic food. Consumers’ motivations, perceptions, and habits. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 41, 46–75. doi: 10.1080/21683565.2016.1243602

Radman, M. (2005). Consumer consumption and perception of organic products in Croatia. Br. Food J. 107, 263–273. doi: 10.1108/00070700510589530

Raif, M., and Abdellatif, A. (2021). The factors influencing the consumption of local products in Morocco. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Res. 1. Available at: https://revues.imist.ma/index.php/IJEMARE/article/view/20680/12895

Rizzo, G., Borrello, M., Dara Guccione, G., Schifani, G., and Cembalo, L. (2020). Organic food consumption: the relevance of the health attribute. Sustainability 12:595. doi: 10.3390/su12020595

Smith, T. A., Huang, C. L., and Lin, B. H. (2009). Does Price or income affect organic choice? Analysis of U.S. fresh produce users. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 41, 731–744. doi: 10.1017/S1074070800003187

Statista (2022). The most consumed organic products in France 2022. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/777003/categories-products-biological-the-more-consumed-france/. (Accessed November 9, 2023)

Suciu, N. A., Ferrari, F., and Trevisan, M. (2019). Organic and conventional food: comparison and future research. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 84, 49–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2018.12.008

Tandon, A., Dhir, A., Kaur, P., Kushwah, S., and Salo, J. (2020). Why do people buy organic food? The moderating role of environmental concerns and trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 57:102247. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102247

Tomás-Barberán, F. A., and Gil, M. I. (2008). Improving the health-promoting properties of fruit and vegetable products. Sawston: Woodhead Publishing.

Torres-Ruiz, F. J., Vega-Zamora, M., and Parras-Rosa, M. (2018). False barriers in the purchase of organic foods: the case of extra virgin olive oil in Spain. Sustainability 10:461. doi: 10.3390/su10020461

Tsakiridou, E., Boutsouki, C., Zotos, Y., and Mattas, K. (2008). Attitudes and behavior towards organic products: an exploratory study. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 36, 158–175. doi: 10.1108/09590550810853093

Urena, F., Bernabeu, R., and Olmeda, M. (2008). Women, men and organic food: differences in their attitudes and willingness to pay. A Spanish case study. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 32, 18–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-6431.2007.00637.x

van Bussel, L. M., Kuijsten, A., Mars, M., and van‘t Veer, P. (2022). Consumers’ perceptions on food-related sustainability: a systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 341:130904. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130904

Vanhonacker, F., Van Loo, E. J., Gellynck, X., and Verbeke, W. (2013). Flemish consumer attitudes towards more sustainable food choices. Appetite 62, 7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.11.003

Wang, Q., Sun, J., and Parsons, R. (2010). Consumer preferences and willingness to pay for locally grown organic apples: evidence from a conjoint study. HortScience 45, 376–381. doi: 10.21273/HORTSCI.45.3.376

Whittall, B., Warwick, S. M., Guy, D. J., and Appleton, K. M. (2023). Public understanding of sustainable diets and changes towards sustainability: a qualitative study in a UK population sample. Appetite 181:106388. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2022.106388

Keywords: organic agriculture, organic food consumption, Morocco, consumer perceptions, consumer behavior, SysOrg

Citation: Lafram A, Belfakira C, Hindi Z, Bikri S, Benayad A, El Bilali H, Bügel SG, Średnicka-Tober D, Pugliese P, Strassner C, Rossi L, Stefa-novic L and Aboussaleh Y (2024) Organic food consumption in Kenitra, Morocco: attitudes, motivations, and barriers. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8:1413498. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2024.1413498

Edited by:

Iulia Muresan, University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine of Cluj-Napoca, RomaniaReviewed by:

Gil Fraqueza, University of Algarve, PortugalChristian Grovermann, Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL), Switzerland

Claudia Meier, Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL), Switzerland, in collaboration with reviewer CG

Copyright © 2024 Lafram, Belfakira, Hindi, Bikri, Benayad, El Bilali, Bügel, Średnicka-Tober, Pugliese, Strassner, Rossi, Stefa-novic and Aboussaleh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Youssef Aboussaleh, eW91c3NlZi5hYm91c3NhbGVoQHVpdC5hYy5tYQ==

Amina Lafram

Amina Lafram Chaimaa Belfakira

Chaimaa Belfakira Zakia Hindi

Zakia Hindi Samir Bikri

Samir Bikri Asmaa Benayad

Asmaa Benayad Hamid El Bilali

Hamid El Bilali Susanne Gjedsted Bügel

Susanne Gjedsted Bügel Dominika Średnicka-Tober

Dominika Średnicka-Tober Patrizia Pugliese

Patrizia Pugliese Carola Strassner

Carola Strassner Laura Rossi

Laura Rossi Lilliana Stefa-novic

Lilliana Stefa-novic Youssef Aboussaleh

Youssef Aboussaleh