- 1Graduate School of Agriculture Natural Resource Economics, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan

- 2Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan

Introduction: Japan’s teikei movement, recognized as a source of inspiration for Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) in Western countries, is now entering its fifth decade. Built upon trust and shared values, teikei has continued to rely on mutually supportive relationships between organic producers and consumers. The movement’s commitments were originally articulated through the ten principles of teikei, which offer a roadmap to create food systems based on solidarity principles going beyond market transactions. Despite a decline in numbers, teikei groups continue to operate in the midst of societal shifts that are altering food practices and consumption patterns. These changes have had an impact on the implementation of the ten principles and on the power dynamics between producers and consumers.

Methods: This research investigates how such shifts have affected the development of alternative food systems in Japan, the evolution of teikei as a social movement, and the tensions that arise from contrasting notions of agri-food system alterity rooted in decommodified relationships versus market-based transactions. We employ the ten principles as a framework to investigate the transformations of some representative teikei groups over time, and identify three types of shifts: relational, operational, and ideological. These shifts show how different teikei actors have been engaging in realizing the vision of building sustainable agri-food systems through alternative market relations.

Results: The shifts also underscore the fluid and situated nature of agri-food system alterity within historical, geographical, and cultural relational spaces. The current variations of teikei configurations and the progressive diversification of approaches to address the challenges of upholding the original principles demonstrate the movement’s adaptability over time. However, they also demonstrate the necessity to strike a compromise between conflicting needs.

Discussion: The development of the teikei movement is not only important from an historical and geographically-situated perspective, but also as a dynamic and evolving experiment in the potential and challenges of active food citizenship. The democratic decision-making processes embedded within teikei principles and practices offer a valuable model for understanding how individuals enact their food citizenship and contribute to ongoing transformation of the agri-food system. Simultaneously, these shifts also serve as a warning against how democratic principles can be eroded by conventionalization and neoliberalization, and about the assumptions that arise during the process of building alternative agri-food systems, such as gendered labor.

Introduction

In 2021, the Japan Organic Agriculture Association (JOAA) celebrated the 50th anniversary of its establishment. JOAA was founded as a national-level platform where concerned farmers, doctors, scholars, consumers, and other parties involved in agri-food research and policy came together to promote organic agriculture and challenge the industrialization of the Japanese agri-food system. The founding of this organization represents a key historical marker in Japan’s organic agriculture movement. Notably, the JOAA also played an important role in the development and spread of alternative systems of production and consumption, as it served as an informal networking structure for direct producer-consumer partnerships known as sansho-teikei (literally “producer-consumer cooperation”; hereafter teikei). Although teikei is often cited as the inspiration behind Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) in western countries (Hatano, 2008), teikei practices cannot be directly equated to CSAs or other Alternative Food Network (AFN) models found in western literature. Teikei first emerged as a cooperative-oriented social movement committed to addressing various concerns within the agri-food system, and emphasized the collective, ethical, and de-commodified dimension of producer-consumer relations, which sets it apart from more market-oriented arrangements.

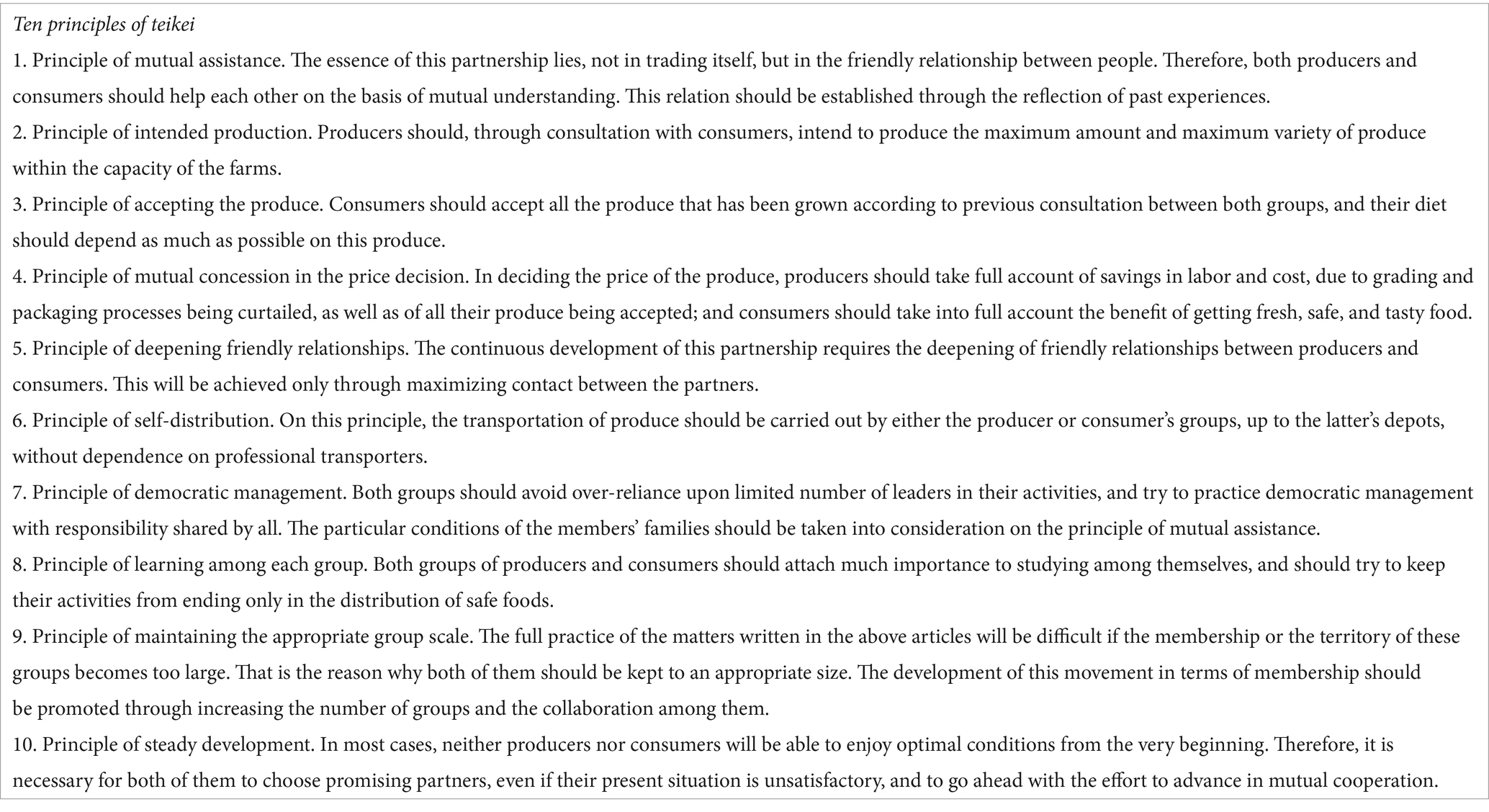

In its original conceptualization, teikei served as the actualized practice of the organic farming movement and its ideals. For instance, teikei put into practice the belief that relationships between producers and consumers should not be based on market transactions but rather on trust, democracy, mutual support, and co-participation in shaping an alternative food system (Masugata, 2008). The commitments underpinning teikei’s practice were eventually enshrined as the “ten principles of teikei,” established by JOAA in 1978 (see Table 1). These principles were distilled from the experiences of the initial teikei groups and subsequently used by teikei members as a blueprint to define the terms of their partnership and logistical operations. As hundreds of grassroots teikei groups emerged throughout Japan, these principles also helped to connect and unify the groups as a social movement.

As with other social movements that flourished in the 1970s in Japan,1 teikei groups saw a gradual decline in their membership and participation over the following decades (Hatano, 2008). Deep socio-economic and demographic structural shifts, such as the rise of neoliberal policies, the erosion of the breadwinner model—resulting in the increased participation of women in the workforce—along with the overall burst of the bubble economy in the 1990s, caused increased precarity and the shift away from social activism, contributing to the decline of the teikei movement. However, even though many of the original teikei groups terminated their activities, some underwent deep transformations to adapt to an increasingly individual-based and convenience-oriented society (Kondo, 2021).

Although the evolution of teikei has been partly addressed in previous works (most notably Kondoh, 2015), publications on teikei’s recent developments are scarce, not only in English but also in Japanese. This research therefore contributes to the literature on the movement, but also, more broadly, to scholarly works on AFN transformation. In the paper, we first outline the historical development of the teikei movement and situate it within the international literature by examining how its principles relate to other conceptualizations of AFNs. We then employ the ten principles as a framework to examine the organizational and structural changes experienced by four major teikei groups that have remained in operation, showing how they have evolved into distinct models and how the ten principles have been variously compromised, replaced, or maintained in the process. We also explore newly emerging teikei-like practices initiated by a new generation of organic farmers to assess the continued relevance of the teikei principles.

In the discussion, we reflect on what the changes in teikei represent for the development of more fair, resilient and sustainable agri-food systems in Japan and elsewhere. In particular, we discuss how the changes in the application of the ten principles reflect tensions between social-movement-oriented and market-based AFNs, tensions that have been driving the transformation of teikei groups over time. The changes within teikei also resonate with contemporary debates on how AFNs can be truly transformative, and on the importance of strengthening the social role of alternative agrifood arrangements by foregrounding principles such as food democracy or food citizenship (Hatanaka, 2020). A critical reflection on teikei’s history and evolution therefore provides valuable lessons for AFNs around the world that are struggling to come to terms with similar tensions and vulnerabilities in their mission to transform food systems. Through our analysis, we hope to offer new perspectives on the opportunities and challenges faced by AFNs in the current landscape of corporatization of organic agriculture and neoliberal capitalism (Johnston et al., 2009).

The historical evolution of teikei

Japan’s rapid ascent to becoming the world’s second largest economy between the 1960s and 1980s was accompanied by rapid urbanization and industrial sector growth, leading to a decline in the agricultural sector and rural economies. At the same time, in an effort to meet the escalating demand for food production and alleviate income disparity in rural areas, the Japanese government promoted land consolidation, specialization and agricultural industrialization. This led to a steep increase in the use of inputs such as synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. At the same time, environmental and food pollution scandals associated with industrial development and industrial food processing became a major source of concern, prompting the mobilization of concerned consumers, farmers, and other stakeholders around the effort to build safer and more equitable systems of food provision (Kondoh, 2015; Hatanaka, 2020). This mobilization gave rise to the first teikei arrangements, initially formed as collective purchasing groups; Kondoh (2015) provides a detailed account of how these first groups were formed and how they operated.

In most cases, it was consumers—particularly female homemakers—who initiated contact with farmers, asking them to transition to organic production methods. In exchange, they committed to purchasing the farm’s entire harvest and providing volunteer labor for harvest and distribution (Masugata, 2008). Although producer-led teikei groups exist, the teikei movement was predominantly developed through consumer-led initiatives, with female homemakers self-organizing into groups and reaching out to farmers, encouraging them to adopt organic farming practices (Kimura and Nishiyama, 2008). This presents an interesting counterpoint to the rise of AFNs in Western contexts, where consumers—and women specifically—were not initially foregrounded as key players in the development of alternative agri-food systems (Goodman, 2004).

To understand teikei’s development, it is important to highlight the critical role played by female consumers in the movement and contextualize it within the broader context of Japan’s economic boom. The 1960s–1980s witnessed both high economic growth and increased social awareness of environmental issues. This era saw the emergence of an expanding urban middle class, comprising urban-based, highly educated, and relatively affluent female homemakers, who played a vital role in the rise of the teikei movement. Despite the overall increase in women’s educational attainments, in this period only a relatively small number of educated women fully entered the workforce, with many leaving the labor market after marriage or childbirth, or participating only as part-time workers (Shimada and Higuchi, 1985). Consequently, the 1960s–1980s became a period in which many educated female homemakers engaged in social activism and movement building activities, such as the consumer cooperative movement and parent-teacher associations (PTA) (Hatanaka, 2020).

In parallel, the increase in environmental scandals and resulting pollution-related diseases also spurred many of these consumers, together with farmers and scholars, to organize and address the costs of industrial growth (Takagi, 1999 Germer et al., 2014). As interest in organic agriculture grew, its proponents felt the need for theoretical and practical guidelines for both producers and consumers. In this regard, the establishment of JOAA provided an organizational foundation to structure the nascent teikei groups. Importantly, the JOAA was predominantly male dominated, being a farmer-centric group, whereas many of the consumer groups involved in the teikei movement were led by women. Thus, the formation of the teikei movement and its principles emerged as the result of producers and consumers coming together.

The founder of JOAA, Teruo Ichiraku, later distilled the discussions, experiences and practices of the early teikei groups he was involved in into a set of principles, codified as the “ten principles of teikei,” in 1978 (JOAA, 2015; see Table 1), which came to represent the foundational philosophy behind teikei’s activities. The main motivation behind codifying the experiences of teikei groups into the ten principles was the desire to highlight how the movement’s activities went beyond the mere marketing of organic produce. Teikei aimed to be an alternative distribution system of organic products based on mutual trust and support between producers and consumers, distinct from conventional economic transactions based on a “commercial relationship of buying and selling goods” (Masugata, 2008, p. 7). The ten principles detailed how to create an alternative food system based on decommodified food system relationships. Furthermore, the structure and functioning of teikei groups were based on democratic deliberation and shared decision-making. In this sense, they represented early experimentations in food citizenship, with citizen-consumers and citizen-producers engaging in meaningful participation over decisions related to the production and consumption of food (Hatanaka, 2020).

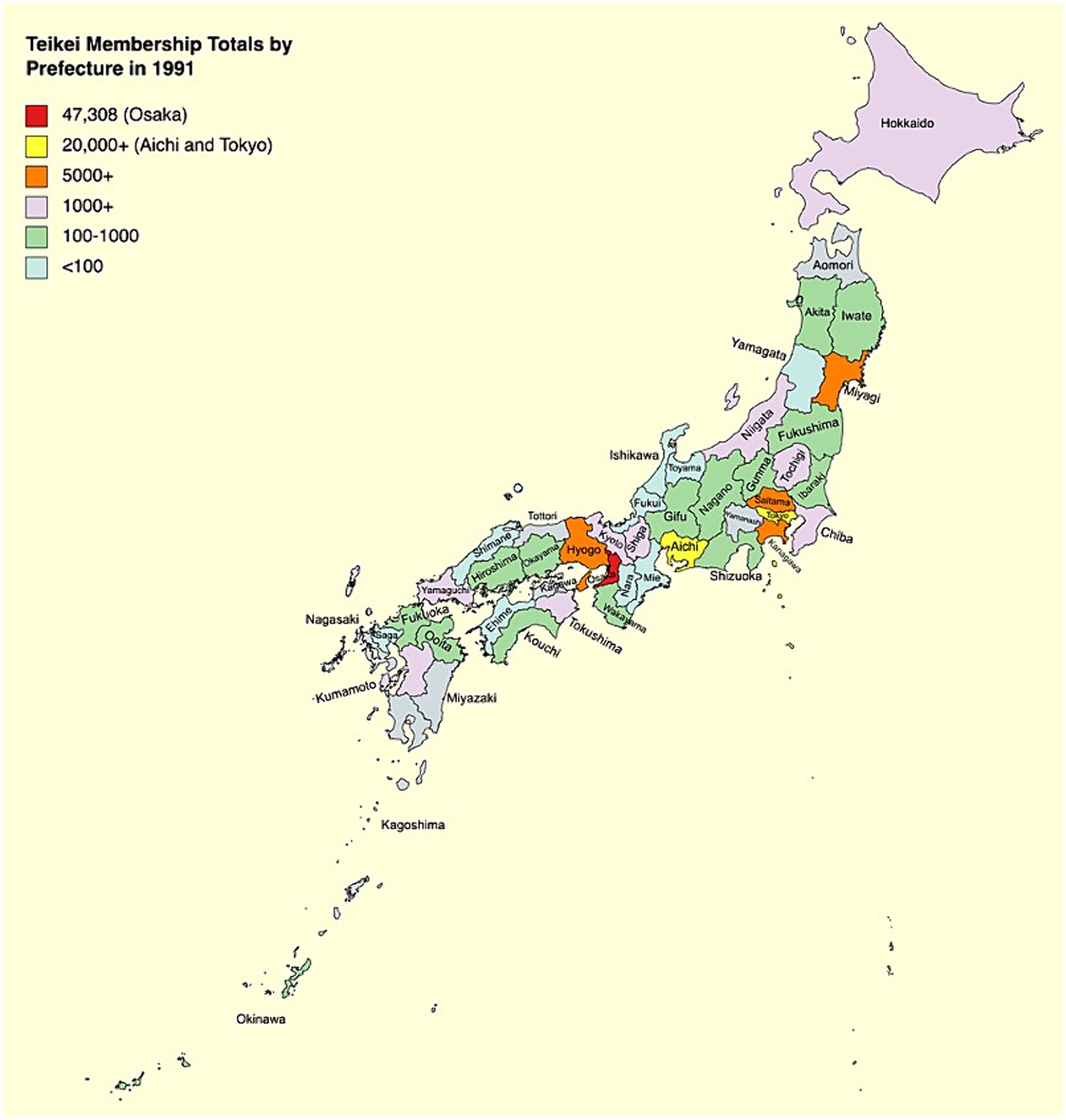

The number of teikei groups peaked in the early 1990s, with about 300 groups throughout the country (Hatano, 2013). While most groups were concentrated in urban areas such as Tokyo and the surrounding region, most prefectures had at least one teikei group (see Figure 1). Based on data collected on teikei groups in 1991, the median group size was around 110 members. Figure 2 provides a geographic breakdown of where teikei activity was strongest. Despite there being the greatest number of groups in Tokyo, Osaka Prefecture had the highest number of members participating in teikei.

Over time, teikei groups evolved into three main types (Hatano, 1998). The first type consisted of organized farmer groups connected to organized consumer groups. The second type was characterized by non-organized farmers selling to organized consumer groups, and the third consisted of non-organized farmers selling to non-organized consumers. The terms “organized” and “non-organized” refer to whether farmers and consumers are associated into a formal group or a cooperative. The first and second types, common among teikei groups formed in the initial stages of the movement, are now in decline (Akitsu and Aminaka, 2010). The third type, which started emerging in the 1980s and is closer in structure to a vegetable box delivery service, has now become more dominant, especially among the younger generations of producers and consumers (McGreevy and Akitsu, 2016; Zollet and Maharjan, 2021a,b).

The decline of teikei groups, especially after the burst of Japan’s economic bubble in 1992, has been attributed to three main factors. The first is market diversification within the organic sector, with retailers expanding their services to offer door-to-door delivery (Hatano, 2008). The increased availability of convenient and reliable direct household delivery services for organic produce made consumer group initiatives less essential (Moen, 2000). Unlike the beginnings of the organic and teikei movements, organic agricultural products today can be purchased through a wider variety of channels, although they remain less widespread compared to western Europe and the US. The second factor is a shift in perception regarding organic consumption. Products labeled “organic” have also partly come to be associated with desirable and affluent lifestyles for health-and environmentally-conscious—and primarily urban—consumers. Evidence of this trend is the proliferation of popular magazines portraying sustainable farming and countryside living as fashionable, as well as the increase of boutique shops, restaurants, and organic corners in department stores in larger cities (Osawa, 2014). The factors driving organic consumption also vary; a recent survey by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery (MAFF) shows that the purchase of organic food is mostly connected to health concerns (22.6%) and effective marketing (20.3%), while environmental protection (7.6%) and animal welfare (3%) rank significantly lower (MAFF, 2019).

The third major factor that contributed to the decline of teikei groups was the increase of women entering the workforce, as teikei consumer groups heavily relied on the volunteer labor of female homemakers (Kondoh, 2015), coupled with increased work precarity and an aging population (Matanle, 2016). As a result, teikei groups are experiencing a lack of generational renewal, particularly among consumer members (Hatano, 2008). Similar changes have also been observed in other social movements, such as consumer cooperatives, where younger members prefer to avoid commitment to solidarity-oriented activism (Nishikido and Kado, 2009). Additionally, the decline of Japanese social movements and their failure to institutionalize their movements can be partly attributed to their fragmentation into small, localized organizations that lack professional staff, a phenomenon described by Pekkanen (2006) as “members without advocates” (p. 178).

Situating teikei within current AFN debates

As described in the previous section, teikei emerged as a social movement with a vision to build alternative market relations to address the negative externalities caused by the rapid industrialization and neoliberalization of Japan’s agri-food system. In this sense, teikei is similar to what are described as AFNs in Western European and North American contexts, insofar as “AFN” is used as an umbrella term to describe initiatives positioned as alternatives to various negative aspects of industrial agri-food systems (Seyfang and Smith, 2007; Tregear, 2011 Goodman et al., 2012). While AFNs may stand theoretically as forms of resistance to the dominant food system, however, the diversity of initiatives that fall under this concept embody a spectrum of practices often riddled with contradictions (DuPuis and Goodman, 2005; Guthman, 2008; Forssell and Lankoski, 2014; Zoll et al., 2021). At the core of many contemporary debates on AFNs is the tension between often-polarized conceptualizations of AFNs either as market-based arrangements or as social movements (Johnston et al., 2009; Misleh, 2022). This tension is also evident in the analysis of processes of commodification/decommodification of both the concrete acts of food production, provisioning and consumption, but also of the relationships accompanying them (Matacena and Corvo, 2019). Given that AFNs operate mostly within capitalist configurations and structures, they are also constantly exposed to the risk of co-optation and appropriation by conventional actors (Galt et al., 2016; Matacena and Corvo, 2019; Zollet, 2023). Much of the current AFN literature therefore questions how alternative agri-food initiatives can “avoid ‘selling out’ to capitalist conformity and yet [provide] the economic security to perform and propagate these ethical values effectively” (Goodman et al., 2012, p. 245).

The tension generated by the need to “sell out” to survive is evident in the evolution of the teikei movement as well. Although teikei was born with a strong social movement orientation at its core, several of the original teikei principles and operational structures are increasingly difficult to uphold for the current generations of producers and consumers, who show declining interest in this aspect of teikei. In the next section, we examine the ten principles through the lenses of these debates, highlighting similarities and differences between the teikei movement and its Western counterparts. This exercise also responds to the call for more multidimensional and multidisciplinary approaches to understanding AFNs, their evolution and their diversity (Blumberg et al., 2020).

The ten principles as a framework to understand alterity and transformation in Japanese AFNs

The ten principles were written both as practical guidelines for producers and consumers engaged in teikei activities, but also as ethical principles aiming to communicate the moral values of the movement to all stakeholders. At the core of the ten principles lies the notion of mutual support, which distinguished teikei from short food supply chains and direct market arrangements that solely sought to eliminate intermediaries in order to maximize profits for farmers. While exchanges in the teikei movement still involve money, they are viewed as a means for people to connect with one another as individuals2 with a common goal—the preservation of social and ecological health and well-being for a better future (Ichiraku, 1984). Accordingly, Principle 1 (Table 1) states that “the essence of the partnership [teikei] lies not in monetary exchanges, but in the friendly relationship [between producers and eaters],” founded upon equality, mutual understanding and assistance. Mutual support is central to teikei principles, and face-to-face interaction (e.g., by participating in meetings, or organizing volunteer work on teikei farms) was seen as crucial to the operation of early teikei groups (Akitsu and Aminaka, 2010). Although this practice reflects concepts such as proximity and resocialization (Dubois, 2018, 2019; Matacena and Corvo, 2019), there has been a tendency among Western AFN scholars to put considerably more emphasis on food (re-)localization and spatial reconnection as precursors of social reconnection (Feenstra, 1997; Hinrichs, 2003; Bowen and Mutersbaugh, 2014). Teikei principles, on the other hand, are more relationally- (rather than geographically-) focused in their approach, as they put little to no emphasis on food provenance and geographical boundaries (“local” food), and instead emphasize social reconnection through meaningful interaction (see also Principle 5). This choice, however, was also partly due to circumstance. Some of the first farmers who decided to collectively switch to organic farming, for example, were located far—sometimes hundreds of kilometers away—from major cities where the urban consumer groups were located. In order to sell their produce, as their rural neighbors grew most of their own food, they had no choice but to send their produce to more distant cities (Kondoh, 2015).

The ten principles of teikei also highlight the importance of going beyond purely capitalist considerations in the production and consumption of food, while AFN literature has only recently started to explicitly engage with these aspects. Principles 2 (planned production), 3 (accepting all harvest) and 4 (mutual concession in setting prices), for example, arose out of the understanding that, in order for farmers to be willing to make the switch from conventional to organic, external support (in this case from consumers, as there was no institutional support) was needed (Kondoh, 2015), and encouraged both producers and consumers to consider the multidimensional (more-than-monetary) benefits arising from their partnership (Emery et al., 2017; Blumberg et al., 2020). In this regard, teikei principles spelled out from the beginning the importance of post-capitalist values such as solidarity and de-commodification of food production and consumption. Interest in these aspects has emerged within AFN literature relatively recently, as a result of the growing interest in new economic models and approaches and their application to agri-food issues. For instance, Rosol (2020) examines the alterity of AFNs through the post-structuralist diverse economies frameworks to explore the complex co-existence of capitalist and non-capitalist elements.

The teikei principles also emphasize aspects such as diversity, self-sufficiency, and autonomy, which are less commonly discussed in Western AFN scholarship, but find common ground with food sovereignty, agroecology, and peasant movement literatures (van der Ploeg, 2008; Matacena and Corvo, 2019). Principle 2, for example, encourages farmers to produce a “sufficient amount and variety of produce within the capacity of the farm,” and to think of consumers’ everyday food needs as an extension of the farmer’s own needs. Simultaneously, Principle 3 encourages consumers to structure their diet around what is produced by the teikei farms. Ultimately, the aim is to create a highly self-sufficient and relatively autonomous agri-food system. Self-sufficiency and autonomy are also highlighted by Principle 6 (self-distribution), which states that teikei groups should not rely on third parties for product distribution. While the AFN literature does focus on reducing intermediaries, this concept is mainly presented from the perspective of increasing sustainability (economic sustainability by removing costs along the supply chain; environmental sustainability by reducing transportation or excess packaging; and social sustainability by encouraging reconnection between food system actors) (Renting et al., 2003; Dubois, 2019). In the teikei principles, on the other hand, the lack of intermediaries reflects the orientation of the organic agriculture movement toward creating an autonomous, solidarity-based distribution system located outside the capitalist market (Kondoh, 2015) and supported by the labor and capital of all involved parties, according to their specific means and abilities.

Principle 7 focuses on the democratic management of teikei groups, which echoes later discourses around democratic participation in food systems, food citizenship, and civic food networks (Renting et al., 2012 Hatanaka, 2020). The emphasis on democratic management suggests ways for citizen-consumers and citizen-producers to work together to co-create a more robust and sustainable food system (Hatanaka, 2020). The focus on collective management is explained both by the history of Japan’s strong cooperative movement, which predates the emergence of the teikei movement, and more generally by Japan’s collectivist culture; unlike CSAs, most of the early teikei arrangements were formed by organized groups of farmers interacting with consumer groups (Parker, 2005).

Participation and democracy are also connected to learning (Principle 8). Recent AFN literature reflects an increased interest around the role of social learning and knowledge co-production in fostering more active participation in the food system (Andree et al., 2019). The emphasis on “learning” within teikei groups similarly reflects the aspiration of turning food-related exchanges into opportunities for education aimed at deeper social engagement and social change. However, while some early teikei groups were connected to other political movements (such as the antinuclear movement) (Masugata, 1995), the Japanese organic agriculture movement as a whole did not engage in social demonstrations and lobbying, but rather aimed at building an alternative system, encouraging its supporters to change their way of life as the most effective way to achieve social change toward a more life-affirming society (Kondoh, 2015). As such, no explicit roadmap was shared as a collective movement on how to lobby for and engender wider processes of societal change.

Finally, Principles 9 and 10 speak directly to issues of conventionalization and co-optation that, in recent years, have been rising to the forefront of both AFN-and organic farming-related debates (e.g., Johnston et al., 2009; Galt et al., 2016). Those who helped draft the teikei principles foresaw the risks inherent in allowing teikei groups to become too large, and the multiple disconnections associated with an overgrown membership. Specifically, Principle 9 suggests that the development of the movement should occur “through increasing the number of groups and the collaboration between them,” rather than by consolidating and increasing the size of each group. Therefore, teikei founders envisioned the scaling of AFNs through “scaling out” of individual networks and connections, rather than through “scaling up” in size. The dilemma of scale has recently been problematized in the international AFN and CSA literature, as they advocate for the growth and expansion of AFNs but also point out the dangers of conventionalization inherent in scaling-up processes (Nost, 2014; Connelly and Beckie, 2016; Milestad et al., 2017).

To summarize, compared to other conceptualizations of AFNs, the teikei principles lack an explicit spatial focus (in terms of the geographical provenance of food and of the centrality of “local” food), but rather emphasize the relational aspects of food exchanges. They also favor a collective rather than individual approach, as shown by the cooperative-inspired structure of teikei groups and the emphasis placed on democratic management and decision-making between consumers and producers, as well as on social learning processes. Furthermore, they are forthright in their post-capitalist orientation, as shown by their emphasis on decommodified exchanges and their caution against cooptation.

At the same time, some key elements addressed by AFNs outside of Japan are not explicitly addressed by the teikei principles. The two most prominent aspects are the engagement with policy-making and advocacy (Andree et al., 2019; Candel, 2022), and the focus on the social and economic accessibility of sustainably-grown food in society as a whole, which is often discussed in food justice and food democracy scholarship, including in relation to CSA (Andreatta et al., 2008; Verfuerth et al., 2023). The apparent contradiction between the democratic orientation of teikei groups and the lack of direct political action may be explained by Japan’s robust tradition of cooperative initiatives (which prohibited association with any political party), along with a strong group-oriented culture, which facilitates collective decisions within groups; in contrast, Japan’s political landscape has been characterized by elitism and a somewhat authoritarian approach to public policy (Parker, 2005).

The lack of attention given to the accessibility of organic food to low-income households can be attributed to the period of rapid economic growth in postwar Japan. During this time, the perception of Japanese society as egalitarian, with the entire population belonging to the middle class (referred to as ichioku sōchūryū, lit. “a middle class nation of 100 million [people]”) became firmly established and widely accepted (Chiavacci, 2008). Consequently, issues such as poverty and food democracy were not seen as priorities even among teikei groups. Although research in the 1970s revealed the existence of a significant population living in poverty, this was overlooked by mainstream research and society (Asai et al., 2008). Moreover, the belief that no one could go hungry in Japan due to its wealth and abundance of food was widespread under the concept ichioku sōchūryū (Abe et al., 2018). Teikei groups, to some extent, continued to adhere to this belief, placing more emphasis on making better (or wiser) food choices for you and your family than on food justice or food security for us all (Yamamoto, 2023). Furthermore, until recently policy discourses about food (in)security in Japan predominantly centered on national level food self-sufficiency, which has been steadily declining and has raised concerns about increasing dependency on food imports and food safety (Assmann, 2010; Kimura, 2018). These narratives appeared more pressing to teikei groups and to the JOAA as well, leading to a stronger focus on revitalizing Japanese agriculture and rural communities through organic farming and teikei partnerships.

After situating teikei and its principles in the broader context of global AFN literature, in the following sections we employ the ten principles as a framework to assess the organizational and structural changes of teikei groups over multiple decades and to explore the evolutionary trajectory of the teikei movement in Japan. In the results, we highlight relational, operational, and ideological shifts in the understanding of the ten principles and in their practical application. In the discussion and conclusions, we return to the points highlighted in this section to outline and discuss the broader implications of teikei’s evolution in relation to AFNs’ transformational role, both in Japan and elsewhere. We also highlight the way in which micro-scale processes within AFNs interact with macro-scale dynamics of social and economic transformation (Misleh, 2022).

Methodology and research sites

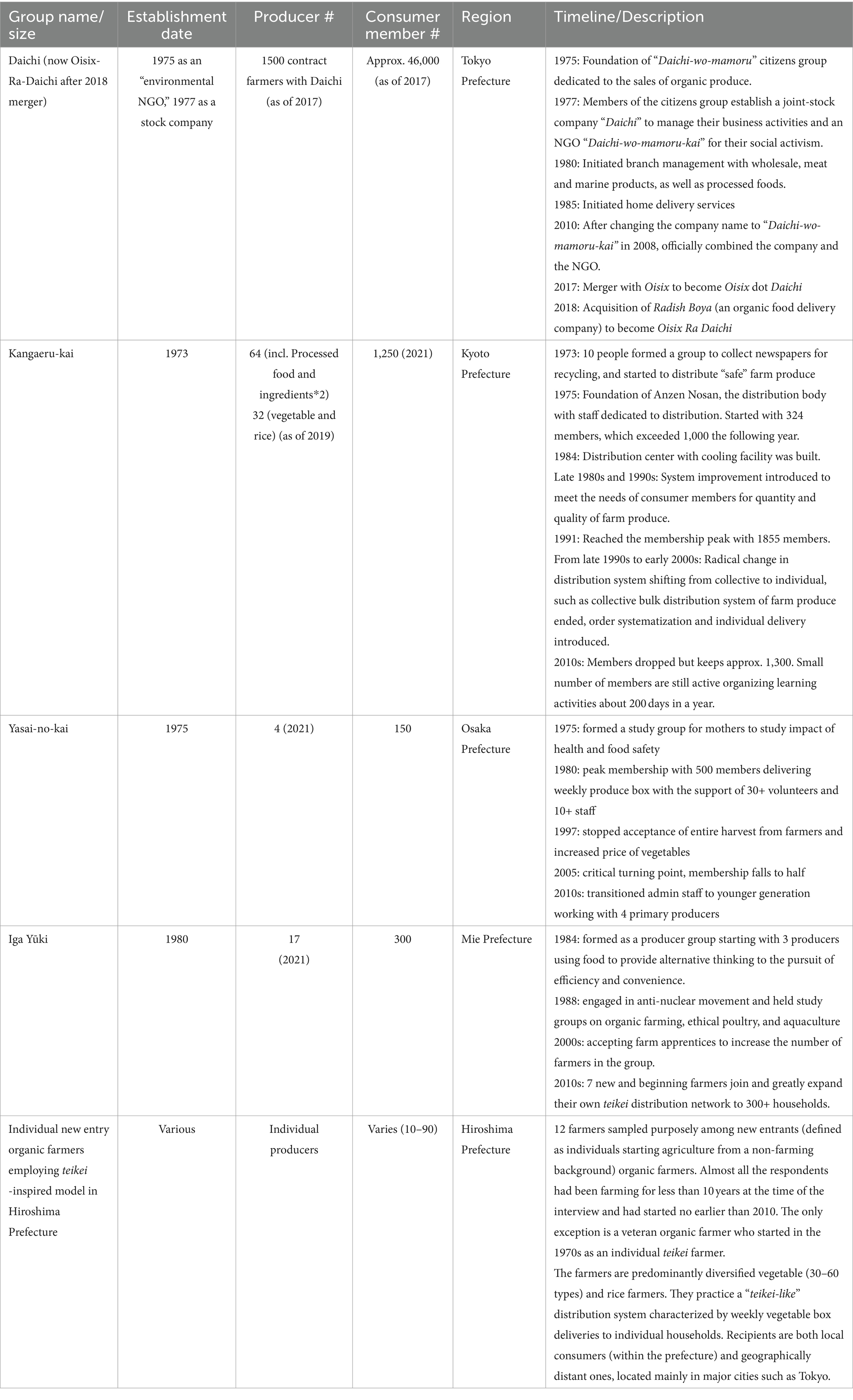

This paper employs multiple sets of data on both teikei groups and farms that operate with practices similar to teikei. Data was collected through four different research projects conducted separately by the authors in Kyoto prefecture (2017–2021), Mie and Osaka Prefectures (2020–2021), and Hiroshima Prefecture (2016–2020), as well as through online interviews conducted in 2021 (Table 2). Although the research projects employed various research designs, they collectively provide insight into the dynamic evolution of alternative food movements in Japan, with a particular focus on teikei and teikei-like organizations. In order to ensure coherence and relevance to the objectives of this paper, we utilized a methodological approach inspired by theory building from case studies (Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007). Our careful selection process within our dataset led us to focus on four teikei groups, chosen for their potential to offer valuable insights for theory development.

These groups were selected because they (a) originated during the early stages of the teikei movement and have since maintained continuity, and (b) illustrate diverse trajectories of evolution and adaptation resulting in various outcomes. This methodological emphasis highlights the strength of our research approach while still acknowledging the limitations inherent in the diversity of research designs utilized. We also added a fifth case study, which is not an organized group, but rather a selection of individual organic farmers with a teikei-like operational structure. These farmers belong to the third typology described in Hatano (1998) classification and were included because they represent an increasingly common form of consumer-producer relationship. Taken together, the five case studies represent different typologies of teikei styles (consumer-led, producer-led, larger versus smaller, as well as organized versus non-organized groups).

Below we describe each case study in detail, and for the four teikei groups we briefly outline key shifts in their organizational and operational structure (see also Table 2).

(1) Tsukaisute-Jidai-wo-Kangaeru-Kai (“Association to Collectively Reflect on the Disposable Society”), hereinafter “Kangaeru-kai.”

Kangaeru-kai, a non-profit organization (hereafter NPO) and consumer-led teikei organization based in Kyoto City, was established in 1973 as a response and critique of mass production and mass consumption trends in contemporary society. The NPO oversees teikei activities such as farm visits, study meetings, and cooking workshops. Kangaeru-kai established its own internal distribution company in 1975, known as Anzen Nosan Kyokyu Center (translated as “Safe Agricultural Produce Supply Center”) (hereinafter “Anzen-nosan”), which operates as a socially responsible business. Members of Kangaeru-kai become members of Anzen-nosan and place their food orders each week in addition to the weekly vegetable set. Membership reached its peak in 1991 with 1,855 members. Today, Kangaeru-kai has approximately 1,300 members, maintaining solidarity-oriented activities based on daily food practices and skill-and relationship-building.

(2) Daichi-wo-mamoru-kai (“Association for the Protection of the Land”) hereinafter “Daichi.”

Daichi was first established in 1975 as a citizen-led group that organized a pop-up market to sell organic vegetables in Tokyo, aiming to “transform society through food.” After its initial success, in 1977 Daichi became a joint-stock company, despite significant protests against its transformation into a for-profit entity. The group, however, maintained its social activism by establishing the NPO Daichi-wo-mamoru-kai. In 1985, Daichi started Japan’s first door-to-door delivery service of organic produce, which led to an exponential increase in their membership. Throughout the 80s and 90s, as the company grew it expanded its produce lineup to include meat (including fish), dairy, and processed foods. In 2017, Daichi merged with Oisix, an online organic produce delivery company. Today they are a part of a conglomerate business called Oisix-Ra-Daichi, offering a range of services such as kit meals, organic produce delivery, and prepared foods. Current membership stands at 45,196 (as of December 2021).

(3) Hirakata Shokuhin Kōgai to Kenkō wo Kangaeru Kai (Hirakata Thinking about Food Contamination and Health) also referred to Yasai-no-kai (Vegetable Club), hereinafter “Yasai-no-kai.”

Yasai-no-kai is a consumer-led teikei group, established in 1975 by 72 housewives concerned about food scandals and health issues. It is located in Hirakata City, a suburb of Osaka. Teikei activities are carried out by consumer and producer members who organize the collection of harvests, processing of weekly boxes, and distribution. They have their own newsletter that is sent out with the vegetable boxes, and the group carries out regular meetings to discuss organizational affairs. Currently, Yasai-no-kai is a smaller group with approximately 50 members and four primary producers. The group also organizes its own social activity circles to continue community building efforts and provide spaces for deeper relationship building.

(4) Iga Yūki-nousanbutsu-kyōkyū-center (Iga Organic Produce Supply Center), hereinafter “Iga Yūki.”

Iga Yūki was established as a producer-led organization with three farms in 1984. Their founder initially served as the head farmer for Kangaeru-kai before starting a localized distribution network for farmers in Iga City, located in Mie Prefecture. The group currently includes 17 farmers, for whom the group coordinates the distribution of produce to several markets. These include their own teikei network of over 300 households located in Iga and Nabari City (the neighboring city), as well as Kangaeru-kai, some consumer cooperatives in the Kansai region, and a few organic supermarkets.

(5) Individual new entry organic farmers employing teikei-inspired practices.

Although most young and new entry organic farmers tend not to explicitly label themselves as teikei farmers, many of them did apprenticeships with older farmers who were themselves part of the teikei system, and their operations are often shaped by the teikei model (McGreevy et al., 2021; Zollet and Maharjan, 2021a). Unlike the early teikei pioneers, however, the new generation of organic farmers tend to have more diversified sales outlets (ibid) and to be influenced by ideas and models from abroad (such as CSA), as many have experienced traveling or living overseas. In this paper we use a sample of farmers from Hiroshima prefecture, but the authors’ field experience, as well as previous literature (see, e.g., McGreevy et al., 2019) suggest that these characteristics and practices are common among new organic farmers throughout Japan.

The data sources used in this paper are primarily qualitative, and include interviews, participant observation (during events, community meetings, processing and farm work assistance), and the analysis of supporting documentation. To address gaps in our data about teikei typologies and their evolution, we also conducted additional fieldwork in 2021. The sample for the first case study (Kangaeru-kai) includes interviews with 34 members (23 consumers, three producers, five board members, and three full-time staff). Additional data was collected through a questionnaire survey (N = 586) for all group members. Data for the second case study (Daichi) was collected through an online semi-structured interview with a Daichi employee who has been with the company since 1991, as well as through detailed accounts of Daichi’s history documented by the founders (Ebisudani, 2015). The third case study (Yasai no kai) is based on semi-structured interviews carried out with 14 members, including both founders and recently joined members. In addition, interviews were also carried out with 3 of the 4 farmer members, together with shadowing on distribution routes. In the fourth case study (Iga Yūki) interviews were carried out with 8 consumer members and with 5 out of their 15 farmer members. The fifth case study includes 11 interviews with new entry organic farmers from different parts of Hiroshima Prefecture, selected because of their adoption of a teikei-like model based on the sale of weekly vegetable boxes to regular customers.

As the original data was collected without a shared research design, rather than attempting a direct comparative analysis this paper focuses on how each teikei organization transformed itself over time and how this reflects on the application of the ten principles. We used a grounded theory approach to examine the pooled corpus of qualitative data and identify commonalities regarding the evolutions of teikei groups through shared discussion based on field notes, experiences, and direct engagement with some of the groups explored in this paper. To strengthen our analysis of primary data, we also analyzed a variety of formal and informal publications produced by teikei groups (newsletters, activity reports) as well as policies related to organic agriculture and teikei. Two of the organized teikei groups are part of a regional organic agriculture consortium (Yuukinougyou Kansai group) that used to meet regularly and organize collective publications dedicated to sharing their thoughts and opinions regarding the direction of the teikei movement. Several of the individual farmers interviewed in Hiroshima Prefecture are members of the prefectural organic farming association (Hiroshima ken Yuuki Nougyou Kenkyuukai), which is active in organizing events and meetings.

Through the combined re-analysis of existing data, we show how teikei groups have changed since the emergence of the movement. We also show different dynamics in the evolution of teikei and its principles through time, dynamics that can be observed among other teikei groups and organic farmers across Japan, as suggested by previous research (Hatano, 2008 McGreevy, 2012 Kondoh, 2015; Yamamoto, 2020; Kondo, 2021; Zollet and Maharjan, 2021a). While we do not claim these case studies to be representative of all teikei typologies and possible evolution pathways, we hope they provide rich material to contextualize discourses and practices, opening up spaces for further theoretical development.

Results

Using the empirical data collected for the five case studies, in this section we outline the challenges that have emerged during teikei’s history and evolution over the last half century and how they reflect on the ten principles. The analysis of the changes occurring within teikei groups, as well as their current configuration, revealed three major “shifts”: (1) relational; (2) operational; and (3) ideological, which are discussed in the following sections.

Relational shift (principles 1, 2, 3, and 5)

A common theme shared across the case studies was the impact of individualized behavior, especially—but not limited to—among consumers. The rise in individualistic thinking was often described by interviewees as one of the reasons for changes in producer-consumer relationships. This relational shift is especially consequential to principles 1, 3 and 5, which clearly spell out the centrality of solidarity and mutual support in de-commodified relationships and the importance of engaging in direct interactions to nurture these relationships. The rise of individualistic behaviors is reflected in the changing organization of teikei groups, especially through the emergence of a more clear-cut division between consumers and producers. Over the years, a stronger emphasis on satisfying consumer needs has also emerged, shifting the focus away from the idea that consumers should be actively involved in production, processing, and distribution activities. Teikei relations between consumers and producers have become increasingly commodified over the last few decades to accommodate shifting needs and decreasing capacity to commit to de-commodified practices.

Consumer struggles

The shift away from solidarity toward a clearer divide between producers and consumers can be seen in the evolution of Principle 2 (intended production) and 3 (accepting all harvest). In the original teikei arrangements, these two principles were put into practice in two different ways. One was more farmer-centric, with farmers deciding what to put into the weekly vegetable deliveries—taking into account consumer’s skills and needs—and consumers accepting what was provided. The other was based on more participatory and democratic decision-making, with farmers and consumers meeting before the start of the growing season to collectively decide what and how much to grow. Subsequently, all the harvest was delivered to consumers. In both cases, consumer members were generally expected to accept what they received without question, in line with Principle 3. Accepting all harvest is an essential component in teikei’s overall philosophy of providing food security for consumers and economic security for the producers. This principle, however, was one of the most contentious, even in the early stages of teikei. For consumers, it was often a burden to receive excessive amounts of one type of produce during peak seasons. The practice of “accepting all harvest” has been discontinued by all teikei groups involved in this study. For groups such as Kangaeru-kai, there is a committee of members consisting of both producers and consumers that meets to coordinate planting schedules, and this committee collectively made the decision to limit the quantity of the same type of produce received by consumers. To deal with excess harvest, the organization now runs a small operation to process surplus crops through canning and pickling.

Another point of contention in accepting all harvest relates to blemished or misshapen produce. Initially, “imperfect” produce was considered a symbol of organic production—as opposed to the flawless appearance of conventionally grown produce sold in the supermarkets. Consumers were expected to accept all produce regardless of appearance, as this was considered a sign of solidarity with farmers in their efforts to produce organically (Yamamoto, 2021). However, with the overall mainstreaming of organic production and the improvement in farmers growing skills, leading to the increased availability of standardized, blemish-free organic produce in the market, consumers’ stance toward the appearance of produce has shifted, with teikei members becoming more reluctant to receive “substandard” vegetables, in turn significantly influencing how the teikei system operates.

Producer struggles

Changes in Principle 1 (mutual assistance) are best exemplified by the decline of volunteer work within teikei arrangements. An older organic farming couple interviewed as part of the Hiroshima case study, for example, used to sell produce exclusively through a locally-based teikei group, and some of the farm operations (such as harvesting and distribution) were carried out with the help of local volunteers, primarily female homemakers. In recent years, however, the number of volunteers has dwindled, mainly due to long-term members getting older and to younger ones having full time jobs and no time to help on the farm. As a result, the farming household has shifted to relying on trainees for help on the farm, and distribution is now partially done through mainstream delivery services.

A decrease in the time to devote to volunteer activities has made upholding principle 5 (deepening friendly relationships through direct interaction) difficult, for both consumers and producers. In the past, both events and volunteer activities were organized by consumer groups so as not to further burden farmers. Among our case studies, the only teikei farm that has maintained the capacity to regularly host volunteer workers is Kangaeru-kai’s teikei farm “Konoyubitomare-nojo.” This is a collectively owned farm operated by producer members of Kangaeru-kai which regularly hosts volunteers and an apprenticeship program to train young organic farmers. Other producer members of Kangaeru-kai, however, expressed that hosting consumer volunteers—who often lack basic farming knowledge and skills—is time and energy intensive and therefore difficult to sustain, both from a practical and personal standpoint. Another farmer mentioned: “I stopped hosting consumers, as I felt like I’d rather spend time working on my own. I was raising my children, my wife was sick, and work needed to get done quickly.” In addition, many Japanese farmers (including organic) now have the option of hosting aspiring farmers through formal training and apprenticeship programs financially supported by the Japanese government (McGreevy et al., 2019), thus making the labor of consumer volunteers less essential.

Regular volunteer activities have partly or entirely been replaced by occasional farm events organized by the farmers, who host friendly educational experiences for visitors, often families with young children. Although most teikei groups in our sample were struggling to find the time and capacity to host and organize activities to maintain and strengthen relationships between producers and consumers, many teikei groups and individual farmers have remained committed to organizing farm events several times a year. While the emphasis has shifted away from providing volunteer labor toward more celebratory or educational purposes, these events still play an important role to reconnect consumers and producers. This is especially important for teikei-like arrangements initiated by new entry organic farmers, where the consumer’s physical involvement in the farm’s activities and face-to-face interaction have become relatively limited. These days, communication is maintained mainly through newsletters or online social networks, which, according to several of the farmers interviewed, are sufficient to establish personal trust between the two parties despite the physical distance. Despite this, however, in-person interaction is still considered essential to embed relationships not only within the social fabric of an alternative food network, but also through embedding the consumers within the farm environment. Furthermore, several of the new-entry organic farmers involved in this study noted that building and maintaining a network on one’s own remains challenging, as it requires each farmer to possess enough social skills and charisma to attract consumers and catalyze their active participation.

Operational shift (principles 4, 6, 7, and 9)

Supporting producer livelihood

Since the late 1980s and early 90s, the members of teikei groups have declined, making it harder for producers to support their livelihoods only through teikei and forcing them to secure additional markets. For younger farmers, in particular, market diversification has become a necessity to earn sufficient income. One of Yasai-no-kai’s producers, a new entry organic farmer, sells to a variety of markets including the Yasai-no-kai teikei group and his own weekly vegetable box scheme, where he distributes produce to a group of families in the same area connected to an alternative pre-school in Osaka. In addition, he also sells through an online organic produce distribution company which has become an important market channel for many organic farmers in the Kansai region. This company is not a teikei group, but aggregates produce from a large network of organic farmers and distributes via customized vegetable boxes and other markets such as supermarkets, boutique grocers, and restaurants.

An additional consequence of market diversification outside of teikei groups is a shift in production practices. Teikei farmers—and organic farmers more broadly—have emphasized from the beginning the importance of shoryo-tahinmoku (diversified farming), growing anywhere from 50 to 100 varieties of produce a year to supply their consumer members with a diversity of products. To meet the demands of multiple new markets, however, over time production and management efficiency have been prioritized. While many teikei farmers continue to grow a variety of crops, many have had to compromise their ideal of having highly biodiverse farms in favor of a more streamlined model able to meet expected production and market demands.

These changes in production and market practices have also impacted Principle 4 (mutual concession in price decision) as declining membership has made it difficult to balance production costs and consumer needs. As a producer-led teikei group, Iga Yūki represents an interesting case study on how to address challenges related to Principles 4 and 7 (democratic management) through their unique engagement with aggregation and market diversification. Iga Yūki has deliberately chosen to operate as a producer-led organization where producers coordinate and manage the production, and consumers are not as active. Producer members cooperate so that, collectively, they can ensure stable production in terms of both quantity and variety, without individual producers having to grow the full array of crops required by consumers. Farmer members of Iga Yūki decide which varieties to grow and are paid according to their harvest amounts at the price point collectively established by farmers themselves. The farmers then aggregate their produce and distribute it via multiple market channels, including their own teikei group, farm stand, consumer cooperatives, and supermarkets. Through managing diversified sales outlets, they can negotiate different sales prices, allowing them to provide more affordable products to their teikei members. Although this model has been successful, there have also been internal coordination difficulties among producers, as the need to have a diversity of produce at the group level means that not all farmers can choose to grow the highest value crops to increase their income. For instance, even though daikon radish is considered a labor-intensive low value crop in comparison to lettuce, which is a low-intensive, high value crop, farmers will be required to grow daikon radish to meet customer demand for diverse produce (Field notes, October 2020).

Distribution challenges

From a logistics perspective, the current practices of teikei groups have diverged from Principle 6 (self-distribution by teikei members), mostly as a result of the decline of volunteer work. Self-distribution is still practiced by small groups such as Yasai-no-kai and Iga Yūki, where the producers themselves carry out distribution activities. For new entry organic farmers using teikei-like operations, deliveries are done either directly by the farmer or by express courier, depending on the customers’ location. Furthermore, in the case of surveyed Hiroshima farmers, although the majority of sales occur within the prefecture, a significant portion of produce is shipped to large cities outside of the prefecture, such as Tokyo and Osaka (see also Zollet and Maharjan, 2021a,b). In 2018, farmers had to face an increase in shipping costs across three major private Japanese shipping companies, leading to significant concerns among those farmers who rely on more distant markets. Furthermore, despite respondents’ stated desire to serve local markets, the continued dependence on urban areas for vegetable sales represents a bottleneck, with consumers in smaller town and rural areas still growing their own food and/or being less interested in purchasing organic produce (Zollet and Maharjan, 2020).

Teikei groups that have expanded, such as Kangaeru-kai and Daichi, have restructured their distribution operations to accommodate a growing membership and multiple product sourcing, completely abandoning the principle of self-distribution. Kangaeru-kai established its own internal distribution company, Anzen-nosan, whose paid staff handles distribution logistics, alongside administrative tasks such as managing orders and payments. In this way, distribution is coordinated separately from the other teikei group activities. However, because Anzen-nosan is not a third-party distribution company but a part of Kangaeru-kai itself, it still operates in line with many teikei principles. For example, Anzen-nosan publishes a newsletter, organizes farm schools for children, and coordinates farm visits with members of Kangaeru-kai.

In the case of Daichi, the effort to reach more people and expand their services nationwide drove the group’s transformation into a more market-oriented company, which in turn led to a more pronounced diversion from principle 6. The group initiated a home delivery service in 1985, but when the group faced difficulties with the overall aging of their membership, it merged with other online delivery service companies, namely Oisix (vegetable delivery service which later expanded to meal preparation) and Radish Boya (organic produce delivery service). Oisix and Radish Boya cater to younger working families, who are attracted by the convenience of online home delivery of organic produce. As their operations grew, Daichi/Radish Boya were able to purchase much higher volumes of produce from organic farmers. The increased scale of their operations, however, also include aspects that contradict teikei principles. For example, their distribution system has fundamental inefficiencies. Daichi’s main distribution hub is in Tokyo, where all fresh produce and other food products are first aggregated and then distributed to their various delivery locations. In other words, it is common for an order of vegetables produced in Hokkaido, the northernmost island of Japan, to first go to Tokyo before being shipped back to a consumer in Hokkaido. Both this issue and the lack of face-to-face interaction among Daichi’s consumers can be ultimately seen as violating teikei’s 9th principle (maintaining the appropriate group scale). At a nation-wide scale, it is difficult to achieve the kind of distribution system envisioned by the teikei movement as trust is articulated through convenience and economic efficiency, essentially replacing solidarity between farmers and consumers.

Ideological shift (principles 8 and 10)

The founders and leaders of the teikei groups in our case studies established their respective organizations to engage in collective action, rooted in a philosophy where agriculture, health and the well-being of people and nature were intrinsically tied together. These groups were often connected through networking organizations, such as JOAA, but they also established additional coalitions to further promote Principle 8 (learning among each group). In the Kansai region, where many of our case studies are located, several teikei groups, including Kangaeru-kai and Yasai-no-kai, formed a regional coalition known as the Yuki-nogyo-kansai-gurupu (Organic Agriculture Kansai Group) to expand their collective action and engage in knowledge sharing and community building. The group self-published3 several magazines, which function as a tool for social learning and education around food citizenship. These publications are a legacy of the group’s opinions and concerns about the current and future direction of the organic movement and help trace the evolution of thoughts and shifting ideology around organic farming and teikei.

An 1988 publication by the group, for instance, discussed the growing divide between “conventionalized” AFNs and the original organic agriculture movement, with reference to a popular slogan used within the movement, “kao-no-mieru-kankei” (relationship between producer and consumer where you can see each other’s face) (Hatano, 2008). This slogan refers to the notion of trust through personally knowing who grew the food, but is now used as a marketing strategy for selling local produce—usually not organic—distributed in conventional supermarkets, where the producer’s face is visible to the buyer via a picture of the farmer (McGreevy and Akitsu, 2016 Zollet, 2023). For many organic agriculture movement activists, back then, this was a form of co-optation—a dilution of their movement’s efforts for marketing purposes, which still persists today (Zollet, 2023).

A similar dilution process has occurred in relation to Japanese government policy around organic farming. In 2014, the MAFF approved the Basic Policy for the Promotion of Organic Agriculture, which included a definition of teikei. In this law, the definition and understanding of teikei was limited to the direct sale of agricultural products between farmers and consumers on a contract basis. Concepts stemming from the teikei principles, such as mutual trust, reciprocity, and shared understanding, on the other hand, were disregarded. Despite the contention this caused, many teikei groups did not advocate for stronger policy and for emphasizing mutual trust and cooperation, which relates to Principle 10. Daichi, for instance, opted to merge with organic online distribution companies that practice the superficial promotion of “kao-no-mieru-kankei,” mentioned above.

Even within the same teikei group, however, there can be contradictions and conflicts. According to the interview with an Oisix-Ra-Daichi employee, in the wake of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, the Oisix arm of the company terminated contracts with farmers in the Tohoku region, while the Daichi arm chose to continue buying from farmers in the region, in the spirit of mutual cooperation with those long-term partners.

Finally, across all surveyed groups we also witnessed a generational gap. The founding farmer and consumer members of teikei groups, now in their 70s and 80s, still feel a strong sense of urgency toward agri-food system transformation, and focus on how their participation contributes to organic farming as a social movement. Many of the younger generation members, on the other hand, especially consumers, express a lack of interest or a lack of time and energy to engage beyond consumption, also shown by the declining participation in an array of teikei activities, from volunteer work to education seminars (Yamamoto, 2020; Kondo, 2021). Less participation in learning activities (Principle 8) further drives members’ lack of awareness about agrifood system issues and promotes de-skilling (for example around food preparation). At the same time, although there has been a decline in the sense of urgency toward agri-food system transformation and in social participation in teikei activities, the idea of building trust and reconnecting eaters with food production and producers is still prominent in the activities of contemporary teikei groups and new entry organic farmers. In addition, among new farmers there is a higher awareness of, and interest around, different ways to organize organic farms and to interact with consumers. This is partly a result of the introduction of “imported” AFN models, such as CSAs and farmers’ markets, which have recently gained popularity, also contributing to the growing recognition of organic produce among consumers (Zollet and Maharjan, 2020). Many new entry organic farmers interviewed in our fieldwork, for example, were familiar with the term CSA and were interested in establishing one for their farm, but did not have a deep knowledge of the teikei movement and its history, a fact that reflects this generational gap but also the continued search for models suitable for each individual farm(er) and their circumstances.

Discussion: the challenges of sustaining efforts toward the creation of a self-sufficient, sustainable food system

The teikei movement represents one of the oldest and longest-lived examples of an alternative agri-food system, predating most AFNs in western contexts. However, over the last 50 years, teikei groups have undergone profound transformations to adapt to a changing economy and society, navigating the tension between commodification and decommodification of alternative farmer-eater relational spaces. Through our analysis, we have identified three types of shifts—relational, operational, and ideological—that have taken place within teikei movements, and reflected on these shifts through the original framework of the movement represented by teikei’s ten principles. Although teikei still emphasizes the role of active food citizenship among its consumers and producers4 (Hatanaka, 2020), the capacity of teikei groups to practice mutual support and democratic decision-making between producers and consumers have been compromised and less evident. Specifically, there has been an expansion from a model centered around active citizen-consumers, toward being inclusive of different models of participation, most notable of which being the more passive consumer. Our field observations for the most part reveal a departure from initial intimate teikei experiences, where consumers shared risks in food production, participated in price decisions and produce distribution. In this discussion section, we summarize the key points that have characterized teikei’s evolution, and what they imply for the development of AFNs both in Japan and elsewhere.

One crucial aspect emerging from our analysis is the gendered dimension of food citizenship. Participation in teikei arrangements demands additional skills and time for sharing, preparing, and consuming the weekly delivered produce, which were tasks predominantly fulfilled by women, who have traditionally been the cornerstone of teikei groups. Despite Japan now having one of the highest populations of working women among developed countries, women are still considered the primary caretakers and food providers in a household. The sharing the burden of domestic responsibilities remains unequal, with the time required for food preparation disproportionately falling on women (Kimura, 2011). Despite these changing pressures, teikei groups have not effectively engaged with the creation of convenient avenues for distributing, preparing and consuming the weekly produce for time-constrained members. Similarly, there has been little emphasis on shifting away from a gendered perspective on food purchase and preparation. The under-acknowledgement of the care work required to be a “food citizen” weakens the capacity to uphold teikei principles in the face of societal change.

Furthermore, despite the significant contributions made by women leaders of teikei groups in formulating the teikei principles, their contribution did not translate into leadership within the JOAA. The predominance of male farmer leadership may have contributed to a lack of effective coordination among teikei groups, keeping cooperation at the level of information exchange rather than engaging in more deliberate movement building. Finally, few convincing alternatives have emerged to replace the unpaid female labor that scaffolded much of teikei’s activities, but which also served as a key relationship-building activity and a bridge between producers and eaters. Nevertheless, Kondo (2021) describes the emergence of paid part-time work opportunities on some teikei farms, where working days are flexible and mothers are allowed to bring their children, creating a working environment that enables women to engage with (paid) work on farms in ways that better suit their needs. If such creative engagements had been introduced earlier in the 1990s, we might have witnessed a higher number of teikei groups in existence today.

Due to declining membership and the expansion of market channels for organic produce, teikei farmers have also had to increase specialization and market diversification, resulting in a partial compromise of ideals such as sustained engagement with consumer members and the maintenance of highly diversified and autonomous farms. The increased availability of organic produce in the market has also compelled producers to prioritize better service and blemish-free produce, resulting in a partial shift from co-production to a more consumer-centered approach. This shift has led to unbalanced power dynamics between producers and consumers, with farmers reverting to assuming most of the risks of production (Galt, 2013). Teikei groups have addressed these challenges in various ways, reflecting different degrees of commodification. For instance, Daichi embraced scale enlargement to reach a broader consumer base, becoming dependent on third-party distribution services. Kangaeru-kai, in contrast, established its own small distribution company and found ways to manage excess produce through processing. Iga Yūki, committed to democratic management principles within its producer group, strengthened collective practices by aggregating farmers’ produce to meet diversified and larger scale demand.

In addition, the co-optation of concepts associated with the organic movement, such as kao-no-mieru-kankei, has made it challenging for the average consumer to distinguish organic teikei farmers from a variety of food localization initiatives and value-adding strategies with weaker environmental and social sustainability claims (Zollet, 2023). Divergent opinions among teikei members reflect the fact that the organic and teikei movements are at a crossroads, with some considering the growing popularity of concepts emerging from the teikei movement as positive, and others condemning the co-optation of their movement. This divergence often also reflects a generational gap as well, with younger farmers and consumers being more willing to accept new arrangements and compromises. It could be argued, however, that advocating primarily for personal lifestyle changes within closed networks of like-minded people has hindered the development and spread of teikei ideals and practices, especially in the face of neoliberalism-driven societal changes that have removed societal safety nets and made lifestyles more precarious. At the same time, the insularity of the teikei movement, its sometimes overly strict ideology, and its attempts to remain outside of the mainstream market have in some instances been detrimental, leading to a lack of generational renewal.

Teikei’s historical distancing from political activism can also be seen as a “missed opportunity” within the movement to organize and institutionalize enough to be able to effectively lobby for better support toward sustainable farming, leaving the door open to a series of concepts, better supported through policy measures, that have diluted the organic movement’s idea of agri-food system sustainability (Kimura and Nishiyama, 2008 Zollet, 2023). The recently approved (2021) Strategy for Sustainable Food Systems has similarly drawn criticism from the organic farming movement for its superficial understanding of organic farming and the teikei movement (Matsudaira, 2021; Taniguchi, 2022).

An open question arises about the extent to which values such as the ones promoted by the ten principles can accommodate more market-oriented arrangements. The boundary between cooptation of alternative models by the industrialized food system and adaptation to people’s emerging needs—while still pursuing radical food system change—appears blurred and is continuously shifting. From this perspective, the concept of hybridity and hybrid food systems offers insights into the challenges of cooperating with mainstream actors while avoiding cooptation (Martens et al., 2022; Zollet, 2023). A connected and newly emerging aspect, especially post-COVID, is digitalization and the use of technology, especially in its role to facilitate consumer-producer exchanges (Lichten and Kondo, 2020). Although our studies did not specifically focus on its role within teikei, the convenience derived from technology often provides greater accessibility and flexibility. These characteristics might be desirable for traditional teikei groups to reach more consumers, even as the perception of technology—especially among older members—remains ambivalent. Intergenerational disagreements on how to adapt existing structures of operation remain a sticky point for several teikei groups, especially those still relying on paper order forms, which can deter new member recruitment.

The results of our analysis, however, also show the successes of teikei groups in perpetuating many of the ten principles. First, due in great part to the existence of teikei, which served as a blueprint for the development of the entire organic movement, Japan is still far from embracing the “corporate organic” model now predominant in other contexts (Johnston et al., 2009). The Japanese organic food sector remains, to a considerable extent, organized around teikei-like relationships, diversified agroecological farming and small-scale distribution (Zollet and Maharjan, 2020; McGreevy et al., 2021), and even teikei groups that have taken a corporate form, such as Oisix-Ra-Daichi, remain committed to core teikei values. In addition, the new generation of organic farmers continues to value small-scale food production, ecological integrity, and community engagement. This is true even for farmers who do not belong to teikei groups or explicitly identify with the teikei movement, which shows the continued influence of the movement’s ideals. On the other hand, the use of the “teikei farm model” as a blueprint for organic farming in Japan has caused a relative uniformity in terms of organic farm management and production. Supporting a diversity of organic production models, while remaining committed to ideals of solidarity and relationship-building, might help in addressing new needs both among farmers and consumers.

The persistence of solidarity practices between producers and consumers is also evident from the groups’ focus on relationship-building and by the resilience of their decade-spanning networks (Norito, 2015). As noted by Kondo (2021), some teikei groups that were founded on non-capitalist ideals, such as the decommodification of food, have successfully adapted to younger generations. These younger members have found ways to sustain engagement with non-capitalist imaginaries through paid work on farms and shared conversation spaces to engage in further dialogue about food safety, food democracy, and food citizenship. For many of these members, the teikei space was not only an entry point to understanding the rationale behind alternative food networks, but also continues to be the only space where they can freely discuss their ongoing concerns about living in an industrialized global food system.

Finally, in a context such as Japan, where trust is derived from being part of social networks (Pekkanen, 2006), teikei groups and the ten principles have been fundamental to laying out the groundwork to develop and sustain social capital and facilitate relationship-building between producers and consumers. Linking trust to individuals being part of a network further emphasizes the importance of local groups in the creation of a more sustainable food system. The benefits arising from being part of a network with high degrees of social capital could serve as a glimmer of hope for the remaining teikei groups, especially as people increasingly reject consumerism and seek reconnection with others and with the land (Rosenberger, 2017 Kondo, 2021; Zollet and Maharjan, 2021a). The continued shared interest in building relationships and networks therefore may reflect a different kind of movement building, not expressed through direct political activism. Rather than choosing to protest the industrialized food system, current teikei practices focus more on the importance of the social connectedness and conviviality that comes from producing and sharing food, including through informal practices such as home-growing, bartering, and gifting (Orito, 2014). Research on contemporary Japan and similar post-growth country contexts also suggests a growing interest in rural living, food self-sufficiency and downshifted lifestyles among the younger generations, which include new approaches to viewing food production, for example as active prosumers (Osawa, 2014). These manifestations of “quiet sustainability” (Jehlička and Daněk, 2017) hold promise in changing food systems, at least at the local level.

At the same time, a renewed focus on collective action is necessary, as demonstrated by the growing engagement of international AFN literature with social movements and policy engagement (Andree et al., 2019; Zollet and Maharjan, 2021b). Some emerging examples in Japan include the development of municipal-level food policy councils and the development of organic school lunch programs. Both are promising entry points for policy and advocacy around agri-food system transformation, as these initiatives seek to work with municipal governments to institutionalize alternative food system approaches (Tsuru and Taniguchi, 2023). Such initiatives would also support more equitable access to organic food, especially for children. Finally, and perhaps more importantly, the divergent evolution and the fragmentation of teikei groups over time suggest the need for stronger and more active coordination among groups, in order to strengthen relationships among AFN advocates. This includes supporting organic farming at the territorial and level through community-level organic conversion and the clustering of new organic farmers (McGreevy et al., 2021; Zollet, 2024).

Conclusion

This paper has examined the evolution of teikei groups from the 1970s to the present day, analyzing their relational, operational, and ideological shifts in alignment with teikei’s foundational ten principles and shedding light on the lived experiences of teikei members. Exploring the historical arc of how farmers and eaters committed to democratic decision-making processes and how they actively shaped their alternative food system provides valuable insights in both the resilience, weakness, and adaptability of the teikei model. By delving into the nuanced changes made by teikei groups, we explored how the changes they made both diverge from, and strive to support, the essence of the ten principles set forth at the beginning of the movement amidst shifting socio-economic conditions in Japanese society.