94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Food Syst. , 14 March 2024

Sec. Agricultural and Food Economics

Volume 8 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2024.1367362

This article is part of the Research Topic Strategies Of Digitalization And Sustainability In Agrifood Value Chains View all 23 articles

Alessandro Petrontino1

Alessandro Petrontino1 Michel Frem2*

Michel Frem2* Vincenzo Fucilli1

Vincenzo Fucilli1 Emanuela Tria1

Emanuela Tria1 Adele Annarita Campobasso1

Adele Annarita Campobasso1 Francesco Bozzo1

Francesco Bozzo1Introduction: Pasta is a key product in Italy’s agri-food industry, consumed due to its ease of preparation, nutritional richness, and cultural importance. Evolving consumer awareness has prompted adaptations in the pasta market, to address concerns about social, environmental, quality, and food safety issues. This study examines Italian consumers’ willingness to pay (WTP) for pasta in local markets, analysing their behaviours and preferences.

Methods: For this purpose, we used a discrete choice experiment (DCE) technique combined with a latent variable model. We also collected 397 valid online questionnaires.

Results and Discussion: The results reveal an interest utility among all respondents to pay a price premium of €1.16, €0.82, €0.62, €0.41, and €0.36 for 500 g of pasta, for the use of blockchain/QR code (BC) technology on the label, providing data on credence attributes such as safety, environmental and social sustainability as well as business innovative practices, respectively. As such, this research has private and public implications. On one hand, this research may bridge the scarcity in studies regarding consumer preferences and WTP for BC in the pasta value chain, preventing agricultural frauds, ensuring the sustainability and quality of agri-food products like pasta, and protecting and educating consumers through clear and transparent information. On the other hand, this research may incentivise pasta businesses to meet social and environmental consumers’ demands while simultaneously enhancing their financial performance.

Pasta value chain constitutes a strategic Italian agri-food sector. With an average of 23 kg/capita/year, Italy is the universal leading country in pasta consumption in 2022 and has the first worldwide position in pasta production which is estimated near to 4 million tonnes in 2021 as depicted in Tables 1, 2. Furthermore, Italy holds a share of 28.3% of the global dried pasta export, generating an export value of this category of foods of approximately 4 billion euro in 2022. In addition, Italy produces 3.8 million tonnes of durum wheat from 1.24 million hectares, mostly located in Apulia and Sicily regions (southern Italy), representing approximately 28 and 21% of the total cultivated area in durum wheat, respectively. Despite, it is important to spotlight how the country cannot meet the growing national demand. Thereby, Italy imports pasta and derivatives, with a total of 40.1 thousand tonnes, especially from China and Germany as presented in Table 3 (Statista, 2023). Consumed on a daily based in Italy, dried pasta and similar substances are considered as easy-to-cook, convenient, nutritious, and affordable food category items. However, their relative high carbohydrate contents may cause a barrier for their market growth, mainly for consumers overs 50 years old (Pounis et al., 2016). In this direction, to attract and satisfy consumers, a wide variety of pasta is evolving, integrating different ingredients (i.e., carrots, herbs, beet, and legumes), and including innovative production processes such as organic, gluten-free, and vegan. However, the rising of environmental and social sustainability issues, the food frauds, the food quality and safety, and the impact of innovative technologies constitute continuously the major consumer concerns in the developed countries such Italy. As a result, all economical actors are joining their efforts to satisfy this increasing aware of consumers’ requirements toward more traceable, sustainable, innovative, safe, and high-quality Italian pasta products, inducing a greater consumer willingness to pay (WTP) (Rossi et al., 2023). On the contrary, a lower WTP to them may occur if they have modest information and awareness about safety and healthy features of pasta (Altamore et al., 2017). Thus, there is a need for new research to explore these consumers’ requirements toward as well as their consumption of pasta.

In this direction, many studies have looked at food traceability, sustainability, innovation, and safety from a consumer behaviour perspective. Regarding the traceability issues, several research studies have explored the consumers’ acceptability of blockchain traceability system (BT) as an innovative digital tracking food. Since 2008, the concept of the Internet of Things (IoT) was applied, to become a reality the application of electronic and real-time information sharing (Qian et al., 2020). Consumers’ purchasing behaviour toward traceable food could change according to their perception of these technologies. In their studies, Spence et al. (2018), Yeh et al. (2019), and Lin et al. (2021) analysed consumers’ intention to adopt BT toward the traceability of organic food products, indicating that BT influences positively and significantly their purchase decision. Therefore, BT is considered an important aspect in our research. In terms of sustainability issues, the determinants of consumer behaviour toward environmental and social sustainable pasta production were relatively less addressed in the literature review. In their study, Altamore et al. (2017) assessed consumers’ preferences and opinions toward environmental issues associated with pasta in Sicily, in which the participants, evaluated very interesting the absence of toxins, related to climate conditions in Sicily. This could, therefore, be considered as an ecosystem service that would be useful to evaluate the adoption of sustainable and healthy agricultural models, as suggested by Mediterranean diet. Furthermore, it is crucial to inform consumers how the food traceability system works to gain consumers’ trust in food safety and to build their confidence in it. This consideration was also exposed by Bandinelli et al. (2023), who considered that BT can constitute an important tool, but the mechanism that regulates it must be correctly communicated, so that the consumers can understand its effectiveness in guaranteeing transparency and accountability. Practically, the use of IoT sensors gathers both field and meteorological information about durum wheat production and uploads them into Hyperledger Fabric (Fiore et al., 2023, 2024). An edge computing unit is responsible of converting this huge amount of data into valuable information; then, it uploads the output of the processing to Ethereum. Growers also upload some information about the wheat production (i.e., where it is produced and how it is transported from the field to the cooperative). A consumer, looking at the pasta package in a supermarket, decides to know more about this food. He may open the web app and scans the QR code that he finds on the pasta label. He then retrieves all relevant information about a lot of pasta product, at different stages of the value chain (Galvez et al., 2018), such as: stage of production (i.e., gathering information on but not limited to: varieties, agricultural practices such as the use of the pesticides, fertilisers, or any other agricultural practices that have been applied during the cultivation process, timing, production area, and working conditions); stage of processing (i.e., gathering data on but not limited to: operations conditions, packaging, process of fabrication, safety, and quality assurance); stage of storage (i.e., retrieving data on but not limited to: the quantity, temperature, and humidity); and stage of distribution (i.e., getting data on real-time environmental data of transport and storage, location of the distribution vehicles, transportation timing, and quality control). Consequently, the advantages that the application of BT in a food supply such pasta value chain can bring are many and involve both consumers and producers in terms of: transparency and authenticity of data; security, as the problem of fraud is kept under control; decentralisation; automation and consequent reduction of administrative costs and bureaucratic practices; recognition of goods that do not comply with safety standards and consequent withdrawal of goods from the market; and identification of the true origin of the products as well as the reduction of counterfeiting and falsification of pasta products. In addition, the use of BT technology implements the social sustainability of the pasta, emerging many social elements. In fact, the social sustainability encompasses a series of manoeuvres that aim mainly to ensure a comfortable and dignified life for workers without any distinction between them. In this direction, the social sustainability of pasta products will involve a significant commitment on the part of agricultural households, especially in terms of enhancing human capital through carrying out professional and extra-professional training activities for workers as well as transparency toward illegal work and fair retribution. Furthermore, other potential elements may emerge through this sustainability dimension in terms of: (i) occupational safety, leading to personnel safety training activities, controls, and certifications; (ii) health insurance, prevention, and assistance services; (iii) potential pension funds and insurance policies for workers; (iv) initiatives for the reconciliation of work with personal needs such as leave and flexibility of hours, support for parents for the management of children, facilitations for meals, transport, and accommodation; and (v) initiatives to support immigrant workers for housing facilities, bureaucratic facilitations, and language training.

With respect to innovation issues, numerous scientific studies have addressed the determinants that affect consumers’ perception and estimated the WTP by type of pasta toward this attribute. To examine whether increased vegetable variety enhances healthy food choices and improves meal composition, Bucher et al. (2011) have used a randomised experiment, in which participants tend to select an assortment of pasta and vegetables, inducing a balance meal and improving their food selection. In their studies, Foschia et al. (2014) explored the variation in the preparation processes of pasta made by durum wheat pasta (as a control) and pasta made with durum wheat semolina and pea flour combinations, to assess the quality and to identify the best predictive in vitro glycaemic response in terms of starch degradation. Based on WTP, Pappalardo et al. (2017) have evaluated the economic feasibility of high heat treatments, a physical eco-friendly method for pest control in industrial plants that produce pasta in Sicily (Italy), increasing the factory’s turnover and reducing the environmental impact. In their research, Pasdar et al. (2017) elucidated the compliance between information presented in food labelling of widely consumed foods such as pasta and their true values, inducing misleading effects on food choice and leading to public unhealthy eating. In addition, Predieri et al. (2018) explored the Italian older adults’ consumers toward the development of innovative and healthy pasta sauces. Van der Stricht et al. (2023) studied WTP for front-of-pack labels on microalgae protein pulps. In their studies, Stasi and Baino (2023) assessed consumers’ desires and willingness to purchase five frozen gnocchi formulations, while Palmieri et al. (2021) analysed consumers’ WTP for a novel functional pasta based on Opuntia Ficus Indica. Furthermore, a small number of studies have looked at consumer preferences for the characteristics of pasta as it is. In this direction, Cavallo et al. (2014) conducted a real-world choice experiment considering 10 main intrinsic and extrinsic attributes (i.e., local origin, labelling, organic certification, and branding) of pasta. Finally, Castellini et al. (2022) stated that the acceptance of new food traceability technologies has shown that individual factors are the ones that most influence acceptability.

In this context, the present study will explore the behaviour, preferences, and purchasing decisions of Italian consumers and estimate their WTP toward pasta sold in the Italian markets. Precisely, this research focussed on dried pasta and aimed to answer to the following scientific questions: (i) What are Italian consumers’ attitude and propensity toward consuming dried pasta? (ii) What are their WTP for the presence of the blockchain technology/QR code (hereafter, BC) on the pasta label as an implemented digital tool of traceability? (iii) What are their WTP toward the provision of additional labelling information associated to the environmental sustainability conditions (hereafter, IE), social sustainability issues (hereafter, IS), quality, and safety aspects (hereafter, IQ), and to the innovation business practices (hereafter, IN) used to produce pasta in Italy? (iv) How do their beliefs on food traceability and attention to credence food attributes such pasta, influence their consumption behaviour and purchase decision?

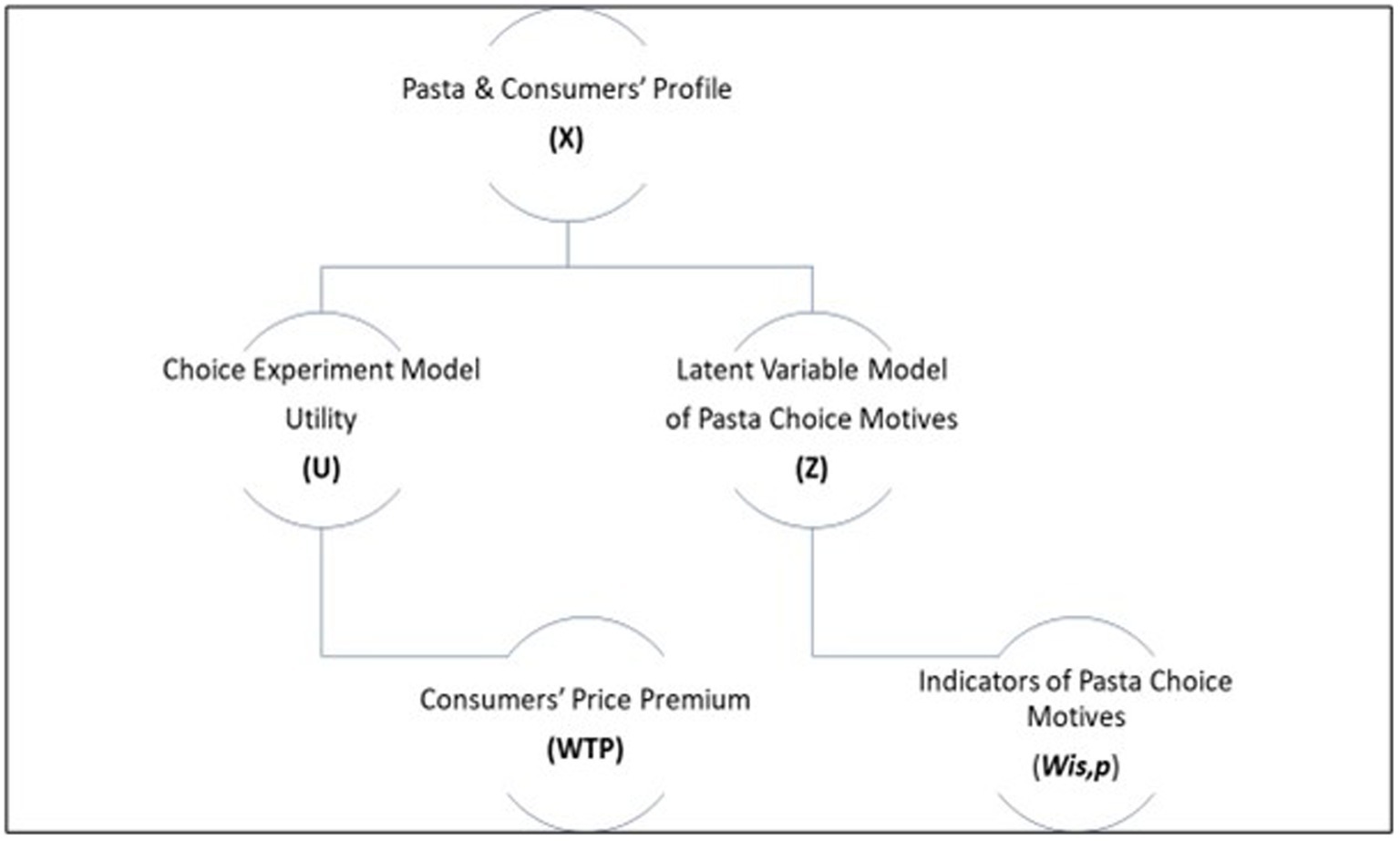

In summary, the originality and relevance of this research might be envisaged in different dimensions. First, there is a dearth of research that have explored the Italian consumer behaviour, propensity, and WTP toward the concerned attributes associated with pasta among the most internationally traded food products, as synthetised in Table 3. For these purposes, we used simultaneously a discrete choice experiment (DCE) approach by means of a mixed logit model (MXL), and a latent variable model estimated within the structural equation model (Ali et al., 2021; Figure 1). Therefore, the remainder of the study is structured into six sections. The next section provides a brief outline of the econometric conceptual framework used for pasta choice. The subsequent section describes the DCE, MXL, and SEM models, in which the choice variables and the data collection survey are also stressed. The results are presented in section four and are followed by the discussion and limitations of the research in section 5. The concluding remarks are highlighted in the final section.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework used in the analysis based on Ali et al. (2021).

The DCE is commonly applied to (i) explore decision choices in economy (Friedel et al., 2022), (ii) elicit consumers’ preferences in marketing research, and (iii) estimate their WTP toward food product characteristics (Petrontino et al., 2022). DCE has also been adequately used in the literature in different contexts to explore pasta consumption. The DCE model involves the following stages: (i) selection of the attributes and the assignment of levels, (ii) experimental design and construction of choice sets, (iii) elaboration of a social questionnaire, (iv) sampling of respondents and survey, (v) econometric data analysis and estimation of the WTP, as described below. Furthermore, the DCE is based on the random utility maximisation (McFadden, 1974), assuming that a consumer would gain a utility from (Equation 1) a food product such as pasta. As such, the utility (Unj) is modelled as follows:

where “No buy” is an alternative specific constant (ASC) representing the no-purchase option, Xj denotes the vector for each alternative j, containing different attributes (BC, IE, IS, IQ, IN) coded as dummy variables, β is a vector of the coefficients associated with each attribute, price is the price vector, and λ is the effect of price on utility (Equation 2). The εnj is the unobserved error term. Heterogeneity in preferences can be considered in the choice model including interaction terms representing the attitudes and beliefs of the consumers as latent variables.

where Zn is the vector of the latent variables scores of n-th respondent, and γ is the effect of this characteristic on the utility function.

Assuming that utility function is individually determined and that psychographic variables are determinants in the behaviour of each respondent, a structural equation model (SEM) was structured to test the relationships between “closeness to blockchain technology” and the psychographic consumers’ latent variables, namely, “attention to credence attributes” and “beliefs on traceability” (Rungie et al., 2012). SEM comprises a system of linear equations that concurrently assess the connections between observable variables, which are measurable items, and the unobservable constructs evaluated by these items. An essential practical benefit of employing SEM for data analysis is its capability to unveil relationships between latent variables that remain unobservable but can be deduced from observable variables. In this direction, the main underlying hypothesis is that the latent constructs of opinion and beliefs can explain the differences in preferences across respondents, resulting in a more efficient and parsimonious model. Since the latent characteristics are not directly observed, a set of k responses to the questions (items) are functions of the latent variables. Zn scores are then estimated through a measurement model that implies the weights of the single items contributing to the latent variables, according to the set of equations where the values of the Ikn indicators (Equation 3) are dependent on the value of the related latent variable:

where δIk is a constant for the k-th indicator, ζIk is the estimated effect of the latent variable Zn on this indicator, and υkn is a disturbance term that is assumed to be normally distributed.

In the DCE approach, attributes are referred to as choice variables, factors, or features used by scientists to describe adequately the consumer’s decision outcome in a hypothetical situation (Friedel et al., 2022). Within each choice attribute, a few numbers of levels are assigned that could be qualitative or quantitative. In our DCE, we choose six attributes (i.e., BC, IE, IS, IQ, IN with 2 levels each, and Price with 3 levels as depicted in Table 4), using a focus group of technical experts, and considering their importance and negligence in terms of traceability for Italian consumers (Petrontino et al., 2023a). In fact, the traceability was often analysed with respect to the food safety and security issues and is considered relatively decisive in marketing strategies that may help to improve the performance of the pasta market. Regarding the social sustainability, we also considered that this attribute is often neglected compared to environmental sustainability and business innovation practices and could influence consumers’ purchase decision and their WTP. The price was considered in this study as discrete variable (Petrontino et al., 2022), and its levels were assigned to cover the current different retail selling prices of the most popular Italian pasta packs of 500 g.

A combination of levels for each attribute (Table 5) is presented to each respondent. Given the excessive number of combinations (i.e., 25 *31 = 96 alternatives), a D-efficient optimal design has been implemented, resulting in 2 blocks with 6 choice sets and 2 alternatives. Accordingly, we elaborated and divided the questionnaire into three different sections. The first section explored respondents’ attitudes and propensity toward the consumption and purchase of pasta, along with 9 questions such as the following: “What is your frequency of pasta purchase? (i.e., once a day; more than once a week; once a week; more than once a month; once a month; less than once a month; never)” (Q1); “Where do you habitually purchase dried pasta? (i.e., hypermarkets, supermarkets, discount shops, pasta factories, local shops, online (e-commerce), other)” (Q2); “When purchasing dried pasta, how much attention (low, medium, and high) do you pay for the following features: price, information labelling, nutritional facts, brand, presence of organic certification, presence of origin certification, and mode of packaging” (Q3); “According to your personal experience, how much (high, medium, or low) of the following characteristics affect the price of dried pasta: origin, purchase site, promotion strategy, qualitative characteristics of the product and characteristics related to the process of production” (Q4); “Which of the following sentences identifies better your behaviour in relation to the purchase of dried pasta: I am willing to buy a larger amount of pasta if the price is low; I am willing to pay a price premium if the pasta is safe and certified; I prefer an adequate quality/price, without caring about the safety of the product” (Q5); Express your level of consent (Strongly disagree; disagree; neither agree nor disagree; agree; strongly agree) related to the transparency of operations along the pasta value chain such a greater transparency of operations along the pasta value chain offer: a guarantee on the quality of the product; social benefits (i.e., respect of the job contract, undeclared work, reduction of labour exploitation, etc.); Environmental benefits (i.e., reduction of gas emissions, better efficiency in the use of water and energy, reduction of food waste, etc.); Benefits in terms of traceability of the production and food safety; An increase of innovation in the agricultural sector (i.e., use of sensors IoT, GPS, drones, etc.), offering benefits in terms of food security” (Q6); “Have you heard about the blockchain technology?” (Q7). “Are you aware (not all; a little, enough; a lot; very much) about blockchain technology associated to agri-food products?” (Q8); “What is your frequency (not all; a little, enough; a lot; very much) of agri-food purchase tracked with the blockchain technology?” (Q9).

The second section of the questionnaire was introduced by a chip talk scripts (Tonsor and Shupp, 2011; Van Loo et al., 2011; Dahlhausen et al., 2018; Jürkenbeck, 2023) describing the selected attributes and providing an example of a set choice (Table 4) to help the respondent in his decision process. Consequently, we presented an adequate number of 6 purchase simulations (i.e., set choice/task choice, Table 4) to prevent respondent fatigue (Hess et al., 2012; Dahlhausen et al., 2018; Petrontino et al., 2023b) and in which each respondent had to select between 2 alternatives (A, B) among each task choice that differed in the presence or absence on the label of the studied product the following: (i) QR code that reflects the blockchain technology, (ii) information on the environmental sustainability issues associated with the production of dried pasta, (iii) information on the social sustainability conditions associated with the production of dried pasta, (iv) information on the quality and safety production, (v) information of the innovation process of dried pasta production, and (vi) price. In addition, the set choice included a no buy option (C) in which we used pictograms reflecting the presence of the concerned attributes (Petrontino et al., 2023a).

The third section revealed the socio-demographic and economic profile of the respondents (i.e., gender, age, residence, civil status, family composition, level of education, work position, work sector, and annual household income).

We carried out an online survey (Survey Monkey, 2023), from June to September 2023, covering the population living in Italy, and engaging 397 valid pasta respondents, considering the Italian population age, gender repartition, and annual household income, in which the sample was in a similar range to the main statistics of Italian population (Istituto Nazionale di Statistica – ISTAT, 2023) as reported in Table 6. Thus, the respondents in the survey were the main responsible for shopping for food for household consumption. For this purpose, we used the Equation 4 considering a margin of error 5%, and a confidence level of 95%, in which we calculated a sample size of 384 respondents and then we decided to increase this value to 400, and finally, we retained 397 valid respondents. Furthermore, the data collected through the online questionnaire were used exclusively for statistical purposes and for this study. They will not be disclosed to third parties or used for private interests, own or others, according to Regulation (EU) 2016/679 on the protection of individuals regarding the processing of personal data. The acquired information was exclusively used in an aggregate way, thus guaranteeing the most complete anonymity of the respondent. Furthermore, the consent from the participants was requested, at the beginning of the survey, to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Where n is the sample size, N is the population size over 18 years old (N = 48,021,983 in the first of January 2023 based on ISTAT 2023), e is the margin of error (percentage in decimal form: 5%), z is the z-score (z = 1.96 for a desired confidence level of 95%), and p is the standard deviation (p = 0.5).

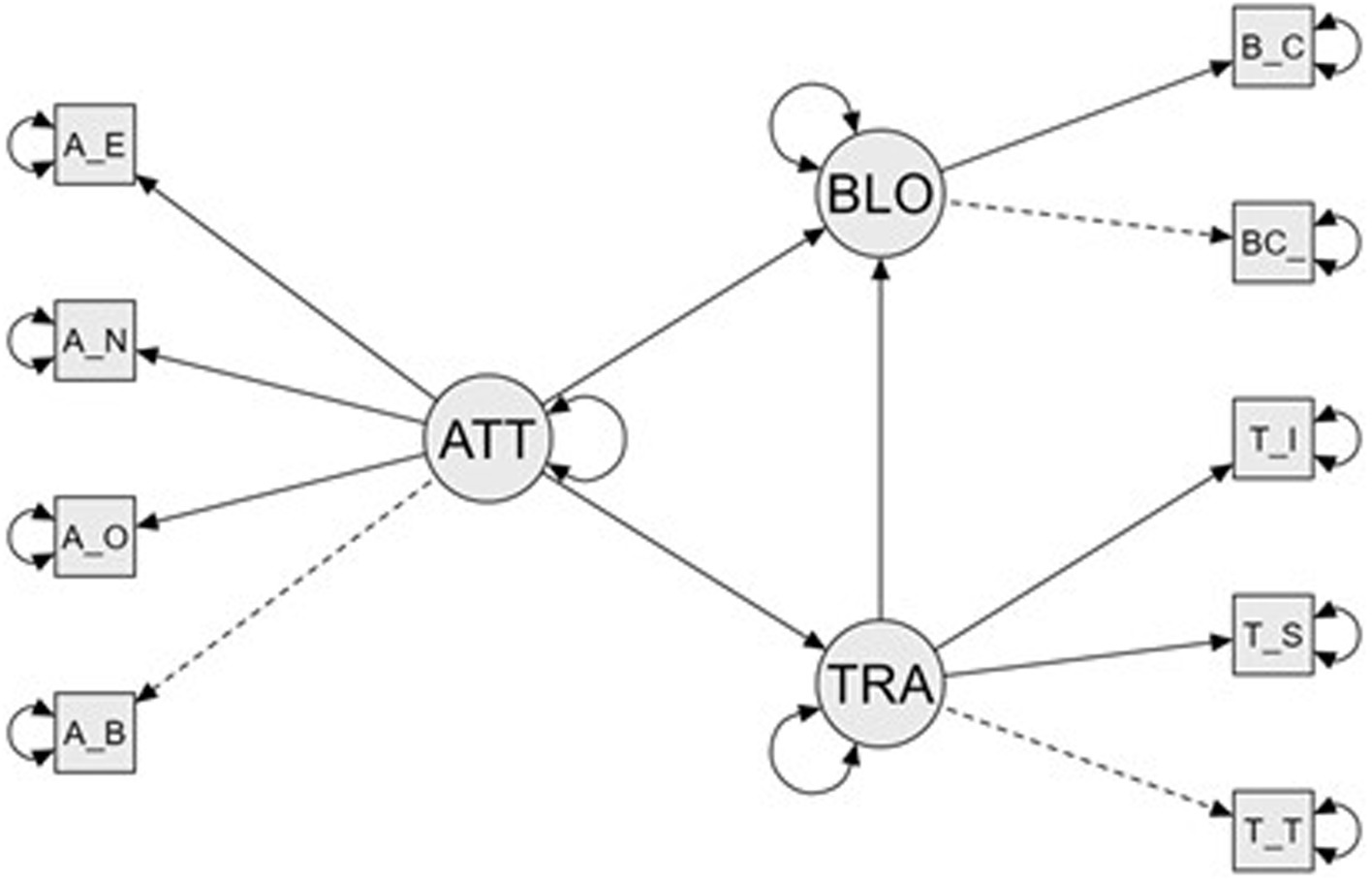

On the one hand, DCE was analysed with the econometric software Nlogit version 5, and Krinsky-Robb method with 500 draws has been utilised to estimate the WTP for each attributes according to their coefficients obtained in MXL model. The weights and the standard deviation of the items belonging to the respective latent variables contributed to calculate the scores to be used in the MXL model as interaction terms with the attributes of DCE. On the other hand, SEM was analysed using the partial least square structural equation modelling tool of the software JASP version 0.17.1.0. The latent variable “closeness to blockchain technology” (BLO) has been putted in relation with the following two latent variables “attention to credence attributes” (ATT) and “beliefs on traceability” (TRA), assuming that BLO is influenced by TRA and ATT while TRA is also influenced by ATT as shown in the Figure 2. After an accurate analysis of the model fit indexes, internal and external reliability, and significance of the settled relations, the composition of the latent construct has been defined as follows. BLO latent variable comprises the two items derived from the question Q7 and Q9. ATT latent variable comprises the four items derived from the question Q3, namely, the presence of organic certification (A_Organic), the presence of origin certification (A_Origin), nutritional facts (A_Nutrition), and information labelling (A_label). TRA latent variable comprises the three items derived from the question Q6, namely, benefits in terms of traceability of the production and food safety (T_Trace), social benefits (T_Social), and an increase of innovation in the agricultural sector (T_innovation).

Figure 2. Relation between the latent variable “closeness to blockchain technology” (BLO) and the two latent variables “Attention to credence attributes” (ATT) and “Beliefs on traceability” (TRA).

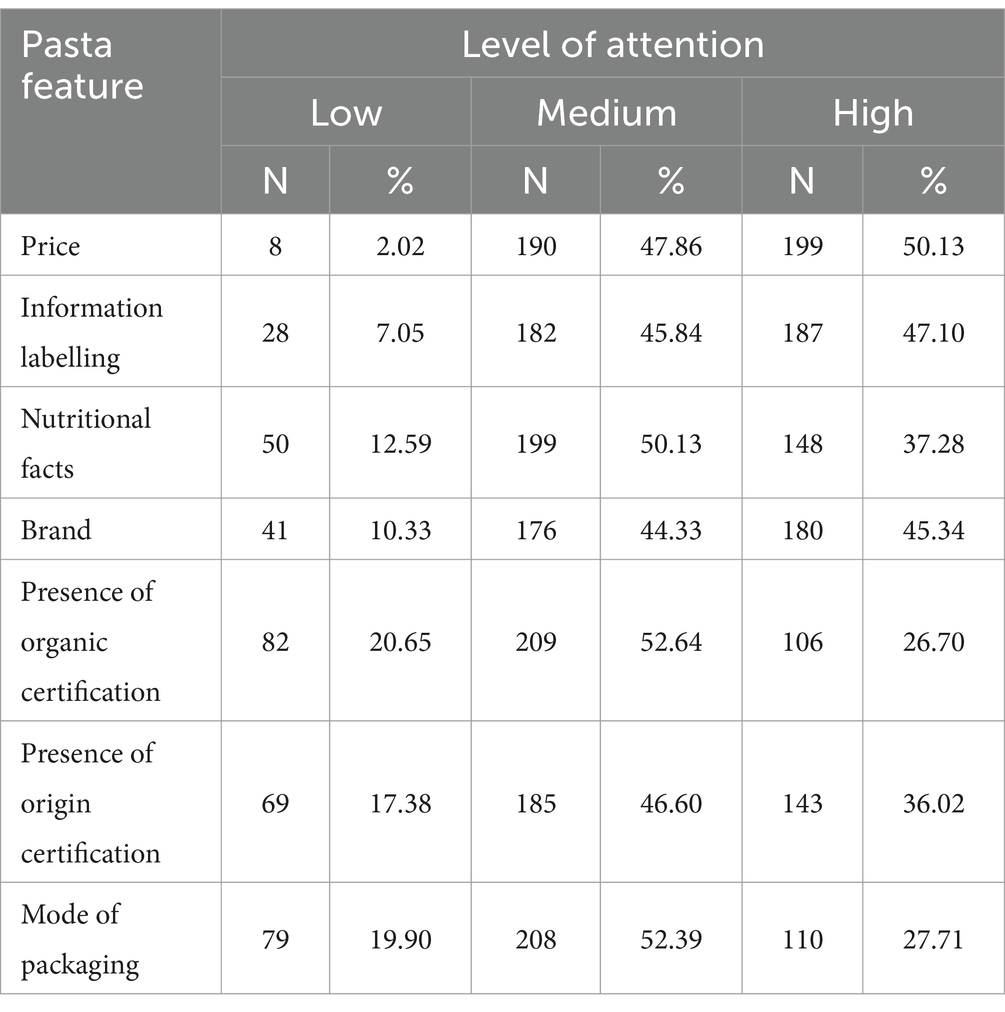

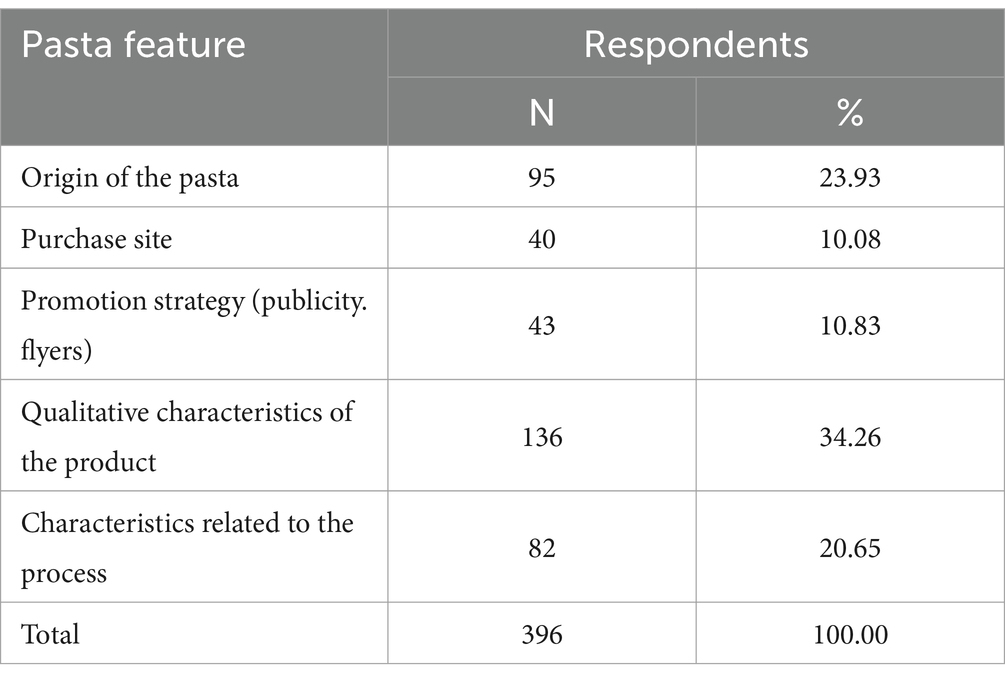

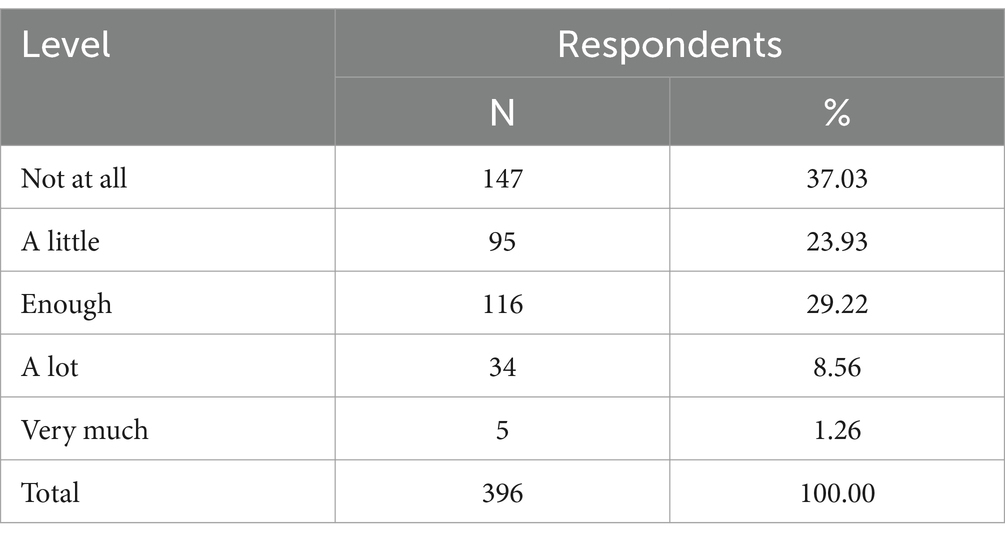

This section presents the main descriptive statistics results related to the parts 1 and 2 of the online questionnaire survey toward the respondents’ attitudes and propensity to purchase food such as dried pasta as well as their socio-economic profile. As a result, supermarkets were the most popular places of purchase of such category of food (28.72%), followed by hypermarkets (19.40%) and discount markets (11.59%), more than once a week as depicted in Table 7. Moreover, approximately 50% of the respondents in this survey conferred a high self-level of attention toward the price of the products and the importance of labelling information, nutritional facts, a medium self-level of attention regarding the nutritional facts, the presence of the origin certification, and the mode of packaging, which indicates that their purchase behaviour was mainly influenced by these product attributes as illustrated in Table 8. With respect to their self-level of experience with the level of influence of pasta features on its purchase price (Table 9), 34.26% of the respondents believed that the aspect of this food category influenced its purchase price, but approximately 10% of them were convinced that the purchase site or the promotional strategy presented relatively a low level of influence on its purchase price. In addition, most of respondents were willing to pay a “price premium” if the dried pasta was safe and certified, followed sequentially by its other attributes, such as its adequate quality/price report, and its relative lower price as revealed in Table 10. The research was also explored into Italian consumer awareness and purchase frequency of agri-food tracked with BC, adopting a five-point Likert scale range, with 1 representing “not at all” or “never” and 5 “very much” or “always” as illustrated in Tables 10, 11. Consequently, very few respondents were very much (3.53%) or a lot (9.57%) aware about blockchain technology and were always (1.26%) or often (8.56%) purchased agri-food products tracked with digital BC as depicted in Tables 11, 12.

Table 8. Respondents’ self-level attention on the characteristics of pasta (in number N and % of respondents).

Table 9. Respondents’ self-level experience with the level of influence of pasta features on its purchase price (in number N and % of respondents).

Table 12. Respondents’ purchase frequency of agri-food products tracked with the blockchain technology (in number N and % of respondents).

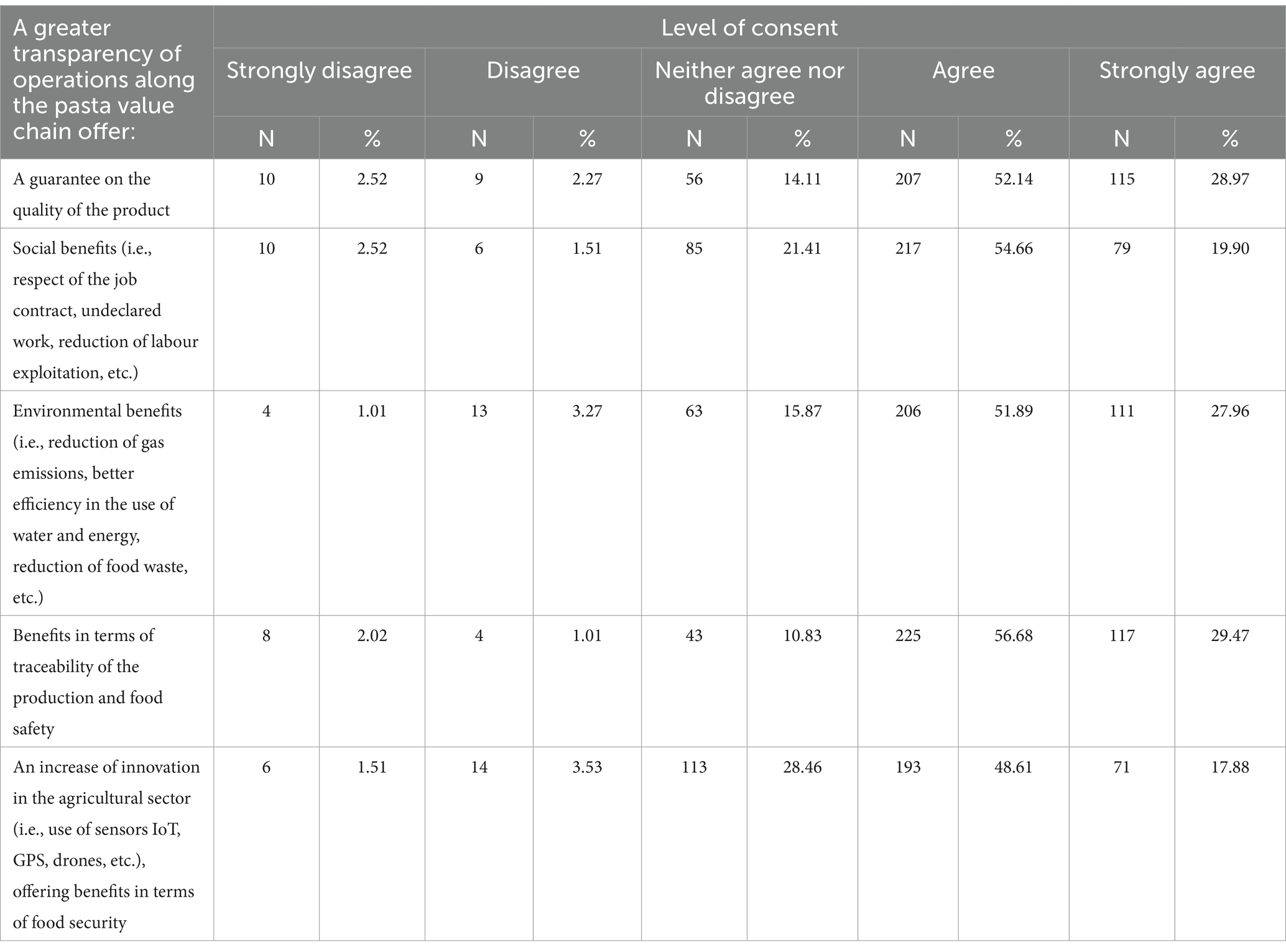

Despite these results, most of respondents agreed that a greater transparency of operations along the value chain, through the use of BC, offered the following: (i) a guarantee on the quality of the product such as dried pasta (52.14% of respondents), (ii) social benefits in terms of the respect of the job contract, undeclared work, and reduction of labour abuse (54.66% of respondents), (iii) environmental benefits in terms of reduction of gas emissions, a better efficiency in the use of water and energy, reduction of food waste, etc. (51.89% of respondents), (iv) benefits in terms of traceability of the production and food safety (56.68% of respondents), and (v) an increase of innovation within the agriculture sector, offering more benefits in terms of food security (48.61% of respondents). For this issue, we also adopted a five-point Likert scale range, with 1 representing “not at all” or “never” and 5 “very much” or “always” as depicted in Table 13.

Table 13. Respondents’ consent related to the transparency of operations along the pasta value chain (in number N and % of respondents).

The latent construct settled to produce the interaction terms to be used in the econometric model as resulted in the following paragraphs has been preliminarily verified in terms of internal consistency, reliability, and discriminant validity (Table 14). Factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE) values show a satisfactory convergent validity of the items used in the construct. In addition, the reliability of the construct, as shown in Table 15, is high.

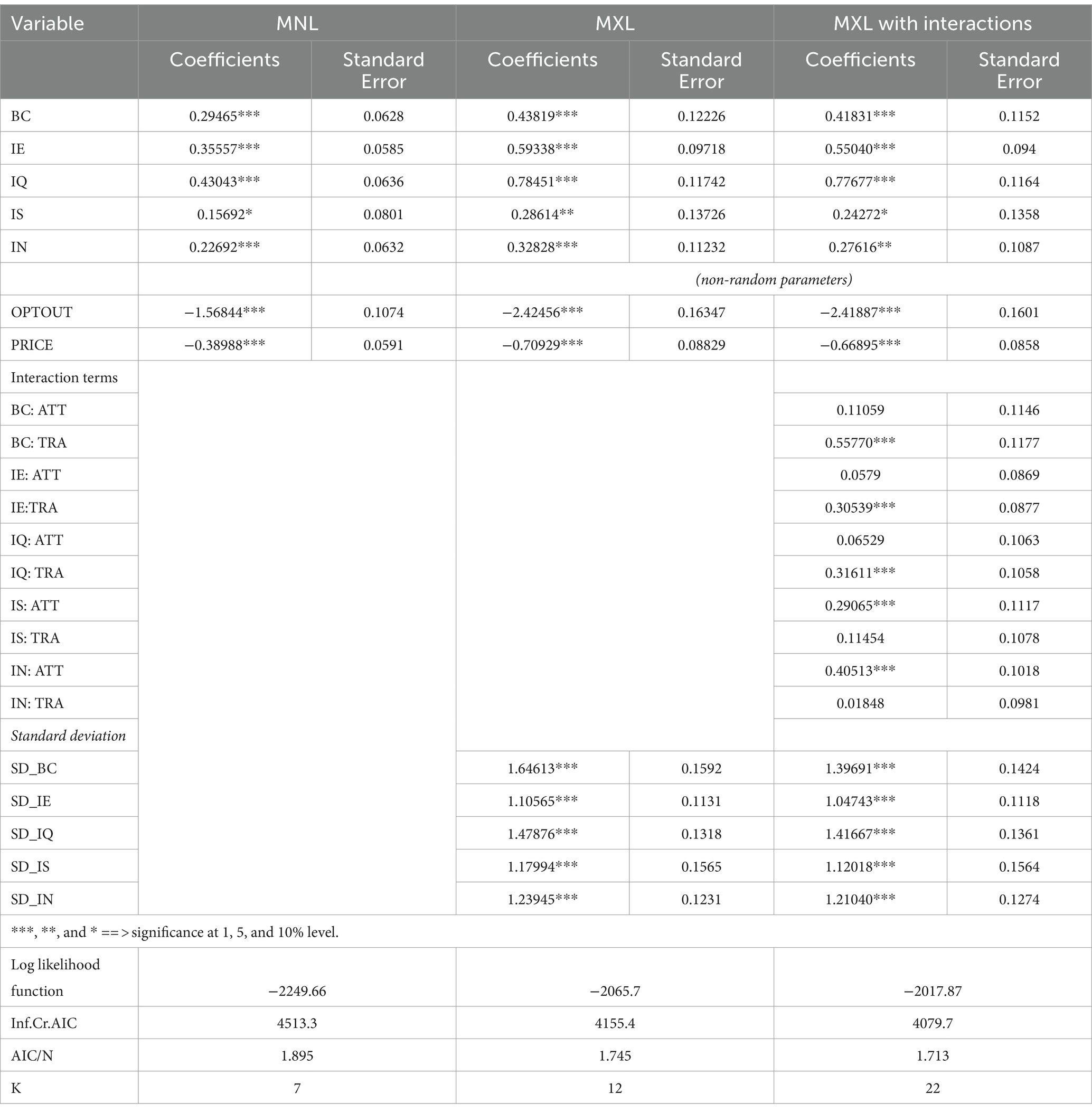

The estimation results from the multinomial logit model (MNL), MXL model, and MXL model including interaction with psychographic terms are reported in Table 16. MXL model with interactions looks to be the more adequate model to explain the consumer choices because it shows improvements in terms of likelihood and information criterion. The coefficient for the price is both negative and statistically significant in all the elaborations, mirroring a discernible impact on consumer choice. Similarly, the no buy option exhibits a noteworthy negative coefficient. Furthermore, the estimated standard deviations for all attributes markedly differ from zero, signifying substantial heterogeneity in consumer preferences for blockchain technology, alongside information pertaining to the environment, social factors, quality, and innovation. The attributes related to blockchain technology and information on pasta production have always positive and significant coefficients, meaning that consumers retrieve utility form this kind of information. The most appreciated attribute is IQ letting believe that consumers are interested mostly in quality information on the food product. The effect of “attention to credence attributes” and “beliefs on traceability” on consumer preferences for all the attributes is included by interaction terms. Looking at the results that come from the interaction between MXL model attributes and the scores of the latent construct, it looks that those consumers that have a stronger belief on benefits of traceability show a greater preference for blockchain technology and the information on environment and quality of pasta. On the contrary, those consumers that pay more attention to credence attributes have a greater preference for social information and innovation of production.

Table 16. Multinomial logit model, mixed logit model, and mixed logit model with interaction with psychographic terms.

Table 16 summarises the consumer’s WTP per attribute type, in which respondents are willing to pay extra EUR 1.16, 0.82, 0.62, 0.41, and 0.36 per 500 g of pasta for a complete information of pasta safety, environmental sustainability, blockchain technology/QR code, innovation business, and social sustainability, respectively. As such, the highest WTP is determined by the “food safety” attribute (average price premium of EUR 1.16/500 g), while the least WTP is determined by the “social sustainability information” (average price premium of EUR 0.36/500 g), indicating that food safety appears to be the most critical consumers’ concerns among the concerned attributes. However, these WTP differences across pasta attributes and consumers are statistically significant as depicted in Table 17.

In this study, we applied and extended the DCE model to explore the influence of a set of attributes (BC, IE, IS, IQ, IN) toward consumers’ purchase propensity for pasta in Italy. As such, we estimated the preferences of respondents through MXL where attributes of the product were interacted with latent variables that proved significant interactions with respect to “behaviour” related to blockchain technology in food choice. Regarding the BC technology for pasta, our results are in line with Contò et al. (2016), who stated that when simulating a pasta buying process through CE, consumers seemed likely to choose products characterised by credibility attributes such as the origin of the wheat, for which they were also willing to pay a premium price. This certainly reflects that the application of a traceability system, through BC, on pasta would positively influence consumer purchasing behaviour, indicating that consumers are willing to pay a premium for the traceability of products. However, digital transformation process could stimulate the innovation in the agri-food sector too. In fact, the technology 4.0 can offer the agri-food companies to create new opportunities for success and gain competitive benefits. In addition, in this context, it is crucial consumer orientation as core competencies in dynamic market environments. Among others industry 4.0 technology, BC represents an innovative voluntary certification system that can improve efficiency, security, safety, and transparency even in food supply chains (Galvez et al., 2018). In addition, Chen et al. (2021) demonstrated that Chinese utility can benefit from both the application of blockchain technology and traditional traceability technologies, and consumers are more inclined to buy ecological agricultural products that use blockchain technology than those that use traditional traceability technologies. In this context, Bandinelli et al. (2023) also evaluated the consumers’ interest in buying a package of ancient wheat pasta that includes all the information about its origin and processing methods. Their results highlighted the importance of the construct “perceived security,” corresponding to “a threat that creates a circumstance, condition, or event with the potential to cause economic hardship in the form of destruction, disclosure, modification of data, fraud, waste, and abuse.”

With respect to the safety and environmental sustainability of the pasta, these issues prevail for Italian consumers, reflecting their concern regarding the food safety information and the sustainable conditions of harvesting and processing, as well as antifraud issues related to pasta. This result is consistent with Altamore et al. (2019), who found that more than 90% of the sample wanted information on the healthiness of pasta or how it is produced, the origin of the raw material, and the absence of elements potentially harmful to human health, confirming the importance of labelling on purchasing choices. In addition, they found that health and origin are characteristics that consumers consider the most important in purchasing choices. Therefore, information and communication on the identity characteristics of pasta seem to play an important role in building consumer awareness and thus influencing the purchase decision (Neuninger et al., 2017). In fact, more informed consumers are more likely to improve preferences for locally grown wheat and local pasta production. Moreover, since a traceability system can become a guarantee for the end user of the purchase of a sustainable product, the results produced by Defrancesco et al. (2017), which tested consumer preferences for the environmental attitudes of pasta, can be considered relevant for the research hypothesis presented. However, they found that, overall, consumers were not only unwilling to pay more for pasta products with beneficial environmental attributes and, to a lesser extent, health effects, but they firmly preferred traditional pasta. Similarly, Rossi et al. (2023) evaluated the WTP of Italian consumers for pasta from sustainable agriculture and the drivers that determine this WTP, but they arrived at more moderate results: Consumers recognised a higher WTP for sustainable pasta, but this value was influenced by drivers such as purchasing habits, personal characteristics, and environmental attitudes. In addition, our findings are consistent with Bandinelli et al. (2023), who reported that consumers are becoming more sceptical of the degree to which information reported on labels matches the actual product (Profeta et al., 2008; Sodano et al., 2008).

In addition, Wang and Scrimgeour (2023) determined that the product origin, quality control, food safety information, hygienic conditions, and scarcity management are the key features of blockchain food traceability that consumers considered to be crucial. Regarding the social sustainability information, our findings are more or less consistent with Nayal et al. (2023) and Kamilaris et al. (2019), who found that BC contributed to social sustainability, helping small farmers in insurance programmes, promoting smart contracts to protect labour from exploitation, and ensuring fairness in payments and taxation. However, our results are less consistent with Rana and Paul (2017), who found that consumers were willing to pay more for socially responsible products. In terms of innovation business, our results are less consistent with Basarir and Dayan (2022), who investigated on how innovative food products are perceived by consumers in United Arab Emirates, and how that perception affects their perceived risk and uncertainty, perceived cost/benefit, and attitude strengths toward the innovations. Moreover, Nazzaro et al. (2019) found that consumers were willing to pay higher price levels for the innovative product rather than for the traditional one. They also found a broad correlation between the innovative product attributes and the psychographic characteristics of consumers in two of the three consumer groups that were identified (i.e., rational adopters and pro-innovation), indicating the existence of many potential consumers. Moreover, as reported by Nazzaro et al. (2019), innovation in the agri-food sector is a tool for addressing the consumer-citizen’s needs (Capitanio et al., 2012) and growing societal issues (Roucan-Kane et al., 2011). In fact it needs to be consider closely social and environmental changes too (Earle, 1997), contrary to the prevalent notion that innovation is primarily a technological process. For these reasons, academic and business attention in food innovations has increased, with a focus on the drivers that could guide consumer acceptance of innovation. In fact, for food firms to succeed in the food market, consumer perceptions of food innovations and their willingness to adopt or adapt them are crucial (Siegrist, 2008).

The obtained findings induce here public and private implications. In fact, this research contributes to the scientific literature by exploring new insights into Italian consumption in pasta preferences utility. Third, the current econometric exploration is primordial to set up market outreach strategies by pasta industrials that would meet Italian consumers’ expectations and, consequently, enhance their financial performances. Fourth, examining consumers’ attitudes and propensity toward the selected attributes has also public implications in terms of protecting and informing the consumer through clear and transparent information, preventing the problem of agri-frauds, permitting to obtain continuous monitoring of the production processes to guarantee the sustainability and quality of the agri-food products such pasta, and providing added services to the consumers. However, the research does not verify spatial variability in consumers’ preferences among Italian regions for the concerned pasta attributes. In this direction, we suggest an extension on examining Italian consumer needs regarding pasta in each region of the country through a face-to-face field social survey and including all species of pasta. In addition, we may allow for extending the research of the consumer segmentation between communities and different socio-demographic and psycho-variables classes.

The analysis conducted revealed, among others, a particularly significant element with respect to the impact of BC on the pasta market. The consumer was willing to pay a price premium toward the guarantee of purchasing a safe product, in terms of the quality and safety, and that was traceable in relation to all the links in its value chain. Meanwhile, studies on consumer preferences and willingness to pay for blockchain technology in agri-food supply chain are limited, and academic research studies investigating supply chain of pasta are rare. In this context, our study aimed to fill this research gap regarding the WTP of consumers for food such as pasta traced through BC, encouraging consumers to make knowledgeable decisions and to take a proactive approach to achieving the goals of social and environmental sustainability as well as public health. In this direction, BC appears to support green practices contributing to achieve environmental targets and can give more benefits for the society. Italian consumers’ preferences may push companies to achieve environmental sustainability and increase demands related to social issues by providing authentic product feedback. All these issues enhance consumers’ environmental and social awareness and improve sustainable performance of the pasta supply chain. Moreover, BC pasta traceability system could overcome the problematic nature of traditional food traceability systems and will reduce the chances of food adulteration and frauds, ensuring that the information on products’ labels is adherence. These capabilities can improve consumers’ awareness in terms of assurance of quality, real-time tracking, safety along the food chain, healthy, and chain clarity. At the same time, BC can be used by stakeholders to promote consumer loyalty, enhance the product’s reputation, and draw in new clients.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The data collected through the online questionnaire were used exclusively for statistical purposes and for this study. They will not be disclosed to third parties or used for private interests, own or others, according to Regulation (EU) 2016/679 on the protection of individuals regarding the processing of personal data. The acquired information was exclusively used in an aggregate way, thus guaranteeing the most complete anonymity of the respondent. Furthermore, the consent from the participants was requested, at the beginning of the survey, to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

AP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. MF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. VF: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. ET: Data curation, Writing – original draft. AC: Data curation, Writing – original draft. FB: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was carried out within the Agritech National Research Center and received funding from the European Union Next-Generation EU (Piano nazionale di ripresa e resilienza (pnrr)-missione 4 componente 2, investimento 1. 4-d.d. 1032 17/06/2022, cn00000022). This manuscript reflects only the authors’ views and opinions, neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be considered responsible for them.

The authors would like to thank Enza Campanella and Daniela Cuppone for their administrative support.

MF was employed by Sinagri S.r.l.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ali, B. M., Ang, F., and van der Fels-Klerx, H. J. (2021). Consumer willingness to pay for plant-based foods produced using microbial applications to replace synthetic chemical inputs. PLoS One 16:e0260488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0260488

Altamore, L., Bacarella, S., Columba, P., Chironi, S., and Ingrassia, M. (2017). The Italian consumers’ preferences for pasta: does environment matter? Chem. Eng. Trans. 58, 859–864. doi: 10.3303/CET1758144

Altamore, L., Ingrassia, M., Columba, P., Chironi, S., and Bacarella, S. (2019). Italian consumer preferences for pasta and consumption trends: tradition or innovation? J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 32, 1–24. doi: 10.1080/08974438.2019.1650865

Bandinelli, R., Scozzafava, G., Bindi, B., and Fani, V. (2023). Blockchain and consumer behaviour: results of a technology acceptance model in the ancient wheat sector. CLSCN 8:100117. doi: 10.1016/j.clscn.2023.100117

Basarir, A., and Dayan, M. (2022). The consumer’s perceptions and attitudes toward innovative foods in United Arab Emirates. EJFA 34:6. doi: 10.9755/ejfa.2022.v34.i6.2895

Bucher, T., Van der Horst, K., and Siegrist, M. (2011). Improvement of meal composition by vegetable variety. Public Health Nutr. 14, 1357–1363. doi: 10.1017/S136898001100067X

Capitanio, F., Coppola, A., and Pascucci, S. (2012). Product and process innovation in the Italian food industry. Agribusiness 26, 503–518. doi: 10.1002/agr.20239

Castellini, G., Lucini, L., Rocchetti, G., Lorenzo, J. M., and Graffigna, G. (2022). Determinants of consumer acceptance of new technologies used to trace and certify sustainable food products: a mini-review on blockchain technology. Curr Opin Environ Sci Health 30:100403. doi: 10.1016/j.coesh.2022.100403

Cavallo, C., Del Giudice, T., Cicia, G., Di Monaco, R., and Caracciolo, F. (2014). Revealed preference approach for analysing consumer preferences: a choice experiment with a real-life setting. Int. Agric. Policy Edizioni L'Informatore Agrario 2014, 44–50. doi: 10.22004/ag.econ.329127

Chen, X., Shang, J., Zada, M., Zada, S., Ji, X., Han, H., et al. (2021). Health is wealth: study on consumer preferences and the willingness to pay for ecological agricultural product traceability technology: evidence from Jiangxi Province China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:11761. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182211761

Contò, F., Antonazzo, A. P., Conte, A., and Cafarelli, B. (2016). Consumers' perception of traditional sustainable food: an exploratory study on pasta produced with ancient native varieties of durum wheat. J. Agric. Econ. 71, 325–337. doi: 10.13128/REA-18651

Dahlhausen, J. L., Rungie, C., and Roosen, J. (2018). Value of labeling credence attributes-common structures and individual preferences. Agric. Econ. 49, 741–751. doi: 10.1111/agec.12456

Defrancesco, E., Perito, M. A., Bozzolan, I., Cei, L., and Stefani, G. (2017). Testing consumers’ preferences for environmental attributes of pasta. Insights from an ABR Approach. Sustainability 9:1701. doi: 10.3390/su9101701

Earle, M. D. (1997). Innovation in the food industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 8, 166–175. doi: 10.1016/S0924-2244(97)01026-1

Fiore, M., Frem, M., Mongiello, M., Bozzo, F., Montemurro, C., Tricarico, G., et al. (2024). Blockchain-based food traceability in Apulian marketplace: improving sustainable Agri-food consumers perception and trust. Internet Technol. Lett. e503, 1–6. doi: 10.1002/itl2.503

Fiore, M., Mongiello, M., and Tricarico, G. (2023). “Blockchain-based food traceability system for Apulian marketplace: enhancing transparency and accountability in the food supply chain” in 35th international conference on software engineering and knowledge engineering (SEKE) (IEEE), Ed. Wiley-Blackwell. New Jersey, USA: Hoboken. 1–4.

Foschia, M., Peressini, D., Sensidoni, A., Brennan, M. A., and Brennan, C. S. (2014). Mastication or masceration: does the preparation of sample affect the predictive in vitro glycemic response of pasta? Star 66, 1096–1102. doi: 10.1002/star.201300156

Friedel, J. E., Foreman, A. M., and Wirth, O. (2022). An introduction to “discrete choice experiments” for behavior analysts. Behav. Process. 198:104628. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2022.104628

Galvez, J. F., Mejuto, J. C., and Simal-Gandara, J. (2018). Future challenges on the use of blockchain for food traceability analysis. Trends Anal. Chem. 107, 222–232. doi: 10.1016/J.TRAC.2018.08.011

Hess, S., Hensher, D., and Daly, A. J. (2012). Not bored yet – revisiting respondent fatigue in stated choice experiments. Trans. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 46, 626–644. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2011.11.008

Istituto Nazionale di Statistica – ISTAT (2023). Italian population in 2022. Available at: https://dati.istat.it/ (Accessed May 5, 2023).

Jürkenbeck, K. (2023). Consumer trust in organic food producers and its influence on consumers’ attitudes toward food reformulation and its sensory consequences. Food Human. 1, 793–799. doi: 10.1016/j.foohum.2023.07.031

Kamilaris, A., Fonts, A., and Prenafeta-Boldύ, F. X. (2019). The rise of blockchain technology in agriculture and food supply chains. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 91, 640–652. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2019.07.034

Lin, X., Chang, S.-C., Chou, T.-H., Chen, S.-C., and Ruangkanjanases, A. (2021). Consumers’ intention to adopt Blockchain food traceability technology towards organic food products. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:912. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18030912

McFadden, D. (1974). “Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior” in Frontiers in econometrics. ed. P. Zarembka (New York: Academic Press)

Nayal, K., Raut, R. D., Narkhede, B. E., Priyadarshinee, P., and Panchal, G. B. (2023). Antecedents for blockchain technology-enabled sustainable agriculture supply chain. Ann. Oper. Res. 327, 293–337. doi: 10.1007/s10479-021-04423-3

Nazzaro, C., Lerro, M., Stanco, M., and Marotta, G. (2019). Do consumers like food product innovation? An analysis of willingness to pay for innovative food attributes. Br. Food J. 121, 1413–1427. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-06-2018-0389

Neuninger, R., Mather, D., and Duncan, T. (2017). Consumer's scepticism of wine awards: a study of consumers’ use of wine awards. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 35, 98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.12.003

Palmieri, N., Stefanoni, W., Latterini, F., and Pari, L. (2021). An Italian explorative study of willingness to pay for a new functional pasta featuring Opuntia ficus indica. Agriculture 11:701. doi: 10.3390/agriculture11080701

Pappalardo, G., Chinnici, G., and Pecorino, B. (2017). Assessing the economic feasibility of high heat treatment, using evidence obtained from pasta factories in Sicily (Italy). J. Clean. Prod. 142, 2435–2445. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.11.032

Pasdar, Y., Darbandi, M., Azandaryani, H., and Hooshmand, A. S. (2017). Macronutrients compliance between foods labels and marketing package content values. ATMPH 10, 999–1003. doi: 10.4103/ATMPH.ATMPH_309_17

Petrontino, A., Frem, M., Fucilli, V., Labbate, A., Tria, E., and Bozzo, F. (2023a). Ready-to-eat innovative legumes snack: the influence of nutritional ingredients and labelling claims in Italian consumers’ choice and willingness-to-pay. Nutrients 15:1799. doi: 10.3390/nu15071799

Petrontino, A., Frem, M., Fucilli, V., Tricarico, G., and Bozzo, F. (2022). Health-nutrients and origin awareness: implications for regional wine market-segmentation strategies using a latent analysis. Nutrients 14:1385. doi: 10.3390/nu14071385

Petrontino, A., Madau, F., Frem, M., Fucilli, V., Bianchi, R., Campobasso, A. A., et al. (2023b). Seafood choice and consumption behavior: assessing the willingness to pay for an edible sea urchin. Food Secur. 12:418. doi: 10.3390/foods12020418

Pounis, G., Castelnuovo, A., and Costanzo, S. (2016). Association of pasta consumption with body mass index and waist-to-hip ratio: results from Moli-sani and INHES studies. Nutr. Diabetes 6:e218. doi: 10.1038/nutd.2016.20

Predieri, S., Sotis, G., Rodinò, P., Gatti, E., Magli, M., Rossi, F., et al. (2018). Older adults’ involvement in developing satisfactory pasta sauces with healthy ingredients. Br. Food J. 120, 804–814. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-06-2017-0358

Profeta, A., Enneking, U., and Balling, R. (2008). Interactions between brands and CO labels: the case of “Bavarian beer” and “Munich beer”–application of a conditional logit model. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 20, 73–89. doi: 10.1080/08974430802157655

Qian, J., Garcia, L. R., Fan, B., Villalba, J. I. R., McCarthy, U., Zhang, B., et al. (2020). Food traceability system from governmental, corporate, and consumer perspectives in the European Union and China: a comparative review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 99, 402–412. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2020.03.025

Rana, J., and Paul, J. (2017). Consumer behavior and purchase intention for organic food: a review and research agenda. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 38, 157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.06.004

Rossi, E. S., Zabala, J. A., Caracciolo, F., and Blasi, E. (2023). The value of crop diversification: understanding the factors influencing consumers’ WTP for pasta from sustainable agriculture. Agriculture 13:585. doi: 10.3390/agriculture13030585

Roucan-Kane, M., Gray, A. W., and Boehlje, M. D. (2011). Approaches for selecting product innovation projects in U.S. food and agribusiness companies. Int. Food Agribusin. Manag. Rev. 14, 51–68. doi: 10.22004/ag.econ.117599

Rungie, C. M., Coote, L. V., and Louviere, J. J. (2012). Latent variables in discrete choice experiments. J. Choice Model. 5, 145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jocm.2013.03.002

Siegrist, M. (2008). Factors influencing public acceptance of innovative food technologies and products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 19, 603–608. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2008.01.017

Sodano, V., Hingley, M., and Lindgreen, A. (2008). The usefulness of social capital in assessing the welfare effects of private and third-party certification food safety policy standards: trust and networks. Br. Food J. 110, 493–513. doi: 10.1108/00070700810868988

Spence, M., Stancu, V., Elliott, C. T., and Dean, M. (2018). Exploring consumer purchase intentions towards traceable minced beef and beef steak using the theory of planned behavior. Food Control 91, 138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2018.03.035

Stasi, A., and Baino, A. (2023). A pre-competitive research on frozen gnocchi: quality evaluation and market survey. Ital J Food Sci. 35, 98–114. doi: 10.15586/ijfs.v35i2.2269

Statista (2023). Leading suppliers of Italy’s imports of pasta in 2022. Available at: http://www.statista.com/topics/10934/pasta-market-in-italy/#topicOverview/ (Accessed November 7, 2023).

Survey Monkey (2023). Available at: https://www.surveymonkey.com/mp/sample-size-calculator/ (Accessed May 9, 2023).

Tonsor, G. T., and Shupp, R. S. (2011). Cheap talk scripts and online choice experiments: “looking beyond the mean”. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 93, 1015–1031. doi: 10.1093/ajae/aar036

Van der Stricht, H., Prophet, A., Hung, Y., and Verbeke, W. (2023). Consumers’ willingness to buy microalgae protein pasta: which label can drive sales? Food Qual. Saf. 110:104948. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2023.104948

Van Loo, E. J., Caputo, V., Nayga, R. M., Meullenet, J.-F., and Ricke, S. C. (2011). Consumers’ willingness to pay for organic chicken breast: evidence from choice experiment. Food Qual. Prefer. 22, 603–613. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2011.02.003

Wang, O., and Scrimgeour, F. (2023). Consumer adoption of blockchain food traceability: effects of innovation-adoption characteristics, expertise in food traceability and blockchain technology, and segmentation. Br. Food J. 125, 2493–2513. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-06-2022-0466

Keywords: blockchain technology, choice behaviour, food innovation, food safety and quality, food sustainability, food traceability information, willingness to pay (WTP)

Citation: Petrontino A, Frem M, Fucilli V, Tria E, Campobasso AA and Bozzo F (2024) Consumers’ purchase propensity for pasta tracked with blockchain technology and labelled with sustainable credence attributes. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8:1367362. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2024.1367362

Received: 08 January 2024; Accepted: 19 February 2024;

Published: 14 March 2024.

Edited by:

Isabelle Piot-Lepetit, INRAE Occitanie Montpellier, FranceReviewed by:

Zlati Monica Laura, Dunarea de Jos University, RomaniaCopyright © 2024 Petrontino, Frem, Fucilli, Tria, Campobasso and Bozzo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michel Frem, bWVmcmVtQHNpbmFncmlzcGlub2ZmLml0

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.