- 1Bloodvein First Nation, Bloodvein, MB, Canada

- 2Department of Indigenous Studies, University of Winnipeg, Winnipeg, MB, Canada

In recent years, changing environmental, developmental activity, government policies and laws, lifestyle changes and affordability dynamics have continued to threaten the self determination and food sovereignty of Indigenous peoples in the community. Their perspectives, teachings, and voices are rarely present in any scholarly work. Despite food security being a significant challenge among many First Nations communities on Turtle Island, there needs to be more empirical, community-based research that underscores the role of traditional food systems and associated values and teachings in Manitoban communities through an Indigenous lens. This research addresses that gap by building upon Indigenous perspectives and knowledges on the status and future directions of food security and sovereignty in Misko-ziibiing (Bloodvein River First Nation). Guided by Indigenous research protocol and using a qualitative research approach, ten in-depth interviews with Bloodvein River First Nation (BVR) and Winnipeg Elders were conducted. Data was also sourced through discussions with local council members, participant observation, and field visits during 2017. The fundamental values and traditional teachings associated with food sovereignty within the community are aligned with the spirit of sharing, including sharing ethics and protocols, social learning within the community, and intergenerational transmission. Enhanced intergenerational transmission of traditional teachings, education and language revitalization, and local leadership involvement can strengthen these social and cultural values to enhance Indigenous food security and sovereignty in Misko-ziibiing. This research identifies the knowledge and views of Elders, hunters, trappers and fishers, contributing to the current studies associated with traditional food systems and teachings. Strengthening social and cultural traditions and values is vital in working toward Indigenous food governance, sovereignty, and revitalization of their Indigenous food systems.

1 Introduction

Prior to colonization, Indigenous peoples had a strong relationship to their food systems which was necessary for the ongoing survival of their communities and cultural practices. Colonial systems in Canada have negatively impacted this relationship such as connections to land, food, and knowledge. Despite colonization, there is an ongoing resurgence of Indigenous food systems and connection to traditional territory through processes of engaging in traditional knowledges and spiritual and cultural values (Wendimu et al., 2018). It is important to acknowledge the role that traditional food systems and strengthening cultural values plays in the revitalization of Indigenous food sovereignty (IFS). The Indigenous Food Systems Network identified four principles of food sovereignty: (1) food is sacred; (2) participation in land-based activities is essential; (3) self-determination is critical; (4) and policy reform is a necessary component to achieving food sovereignty (Morrison, 2011). Traditional food systems are building cultural knowledge and practices, satisfying holistic health, and connecting community through active production, consumption, processing, and distribution of foods. These systems and traditional knowledges are passed down through land-based experiential teachings across generations which is central to Indigenous food systems and food sovereignty (Settee and Shukla, 2020). Additionally, traditional food systems “encompass practices which govern the processing and community distribution of harvested animals, as guided by elder oral traditions and cultural values” (Shukla et al., 2019, p. 75). Eating well goes beyond the food itself and every community has distinct food cultures that play important roles in strengthening well-being and connectedness across generations and reinforcing values key to the survival of their cultural heritages (Tamang et al., 2016; Vernon, 2016).

In a study by Haman et al. (2010), it was found that participants in Miskoziibiing (Bloodvein River First Nation) believed that traditional food consumption was a challenge, and declining, due to lack of knowledge of traditional practices for youth, the high costs of harvesting traditional foods, and the growing challenges in accessing traditional foods due to development projects and climate change. These sentiments were shared among Miskoziibiing Elders in this study. There are four factors that have been identified as playing a role in hindering or enhancing Indigenous food systems: (1) the knowledge of traditional food harvesting practices; (2) economics of hunting, trapping, and fishing, (3) the availability and access to traditional foods: and (4) access to traditional territories (Haman et al., 2010). Using these four factors, Miskoziibiing Elders stress that in order to enhance the food system in Miskoziibiing there needs to be active engagement in intergenerational transmission of food teachings and cultural values. When cultural values are cherished and taught, communities – especially youth, acquire resilience and cultural identity. In addition, doing this in ways that use Indigenous languages and ways of learning, we can build upon the foundations of Indigenous values, worldviews, and acknowledgement of the sacredness of food to develop comprehensive and culturally relevant food education (Michnik et al., 2021).

This case study aims to examine the Indigenous food knowledge values and perspectives of Miskoziibiing Elders, hunters, trappers, and fishers in in enhancing food security and Indigenous food sovereignty (self-determined food systems governance). Specific questions addressed in this research were:

1. How are Indigenous food systems (including associated values) understood in Miskoziibiing?

2. What are the challenges for Indigenous food systems in Miskoziibiing?

3. What are the ways in which IFS can be strengthened in Miskoziibiing through engaging in Indigenous food systems?

The processes and knowledges around the interplay between Indigenous food systems and cultural values from Indigenous residents on-reserve is largely understudied. This research identified the knowledges and perspectives of Miskoziibiing participants in a way that will not only contribute to the current studies associated with traditional foods, but it also explores challenges associated with IFS, documenting and preserving Indigenous food knowledge for future generations, and supported Miskoziibiing community members in acknowledging their traditional teachings and knowledge. Indigenous or traditional foods can be defined in many ways, especially when utilizing community perspectives of traditional foods. From a theoretical perspective, traditional foods are a sacred gift that support health and well-being, it links people to their ancestors, each other, and life, and they provide “health, emotional balance, mental clarity, and spiritual health” (Coté, 2016; Jernigan et al., 2021, p. 2). Wilson and Shukla (2020) argue that Indigenous and traditional connect people to their local ecosystems and cultural food practices. What this means, is that traditional foods are and could be foods we typically associate with the land and waters of Indigenous territories, but they can also include introduced foods that have become integral to their health, well-being, and survival such as the introduction of Bannock, a food now synonymous with Indigenous peoples in North America that was introduced by Scottish settlers during the fur trade of the 18th and 19th centuries (Allard, 2023).

Sharing key teachings and values, alongside understanding the barriers and challenges in engaging in IFS, provides an opportunity for Indigenous food system revitalization. The underpinnings of IFS are inherently values-based, holistic, local, and contextual (Martens, 2021). Indigenous foods cannot be separated from cultural values. Kuhnlein (2020) affirms this by sharing that “it is universally recognized that traditional food provides more than the essential physical sustenance; it also provides extensive social and cultural values for communities” (p. vii).

2 Methodology

2.1 Author positionality

The positioning of all authors is an important part of this work, not only to acknowledge the power and privileges we have as being academics and researchers, but to also the tensions we have within our own identities as Indigenous and non-Indigenous authors. Positionality reflects how we view ourselves but also how we are perceived in research spaces, it affects the research process (Holmes, 2020). Kovach (2009) also invites researchers to self-identify within their research to show how relationships are integral to our lives.

The lead author identifies as Anishinaabe from Miskoziibiing and grew up in a large family. It was because of this large family that the importance of food and survival was instilled within her. She grew up listening to the stories that her father shared about the hard times they had feeding such a large family. Although, her family did not consider these times as hard; to them it was life. Her father started hunting with his father and uncles at the age of 13. The stories he’s shared at the dinner table are precious stories; stories that she holds dear to her heart. During her childhood, she understood the seasons based on the food she ate. In the winter, it was trapping and hunting rabbits, moose, and caribou. In the spring, it was hunting geese, ducks, waterfowl, and fishing pickerel, sturgeon, catfish, whitefish, goldeye, jackfish, and suckers. In the summer, it was trips up the river, specifically every Sunday after Catholic Church. In the fall, it was trips to the trapline to hunt for moose, trips up the river for geese and ducks, and commercial fishing on Lake Winnipeg. This was a lifestyle that had been practiced for years, a lifestyle that had been passed on from generation to generation. This way of life instilled love for her family and community within her. My parents, siblings and extended family enjoyed our time together. Today, life is about work, western education, urban areas, and travel. As a mother, her goal is to instill Anishinaabe teachings in her children and to share the experiences that she had in her childhood with them. We share food and tell stories of times with her grandparents, trips to the trapline, hunting, fishing, and harvesting. It was these stories and lifestyles in her past that have influenced this research.

The second author is a first-generation immigrant and original inhabitant from India settled on Treaty 1 Territory. He has always worked with and for Indigenous communities, supporting Indigenous knowledge systems, planetary health, and sustainability in close collaboration with Indigenous communities, academics, governments, and non-government partners from Turtle Island and South Asia. Over the last two decades, he has collaborated with academic and research partners from Canada and Internationally on interdisciplinary research projects on Indigenous knowledge systems and community-based resources management. All of this is to support the ongoing work already being done within Indigenous communities, including this research.

The third author is a Anishinaabe, Cree, and Filipino woman who grew up on the other side of Lake Winnipeg from Miskoziibiing in Fisher River Cree Nation. She grew up medicine picking with her grandmother and listening to stories of what life was like before she was born such as how food was medicine and how connected families and communities were to one another across Manitoba. As she entered Western spaces, she pulled away from traditional practices but reconnected to them through her academic work in food sovereignty. It is not only a pathway to revitalizing Indigenous food systems but reconnecting to ancestral knowledge for a sustainable future.

Our identities have many implications in this work, including our shared responsibilities to support and promote Indigenous livelihood, traditional teachings, resilience, knowledge, and culture.

2.2 Research framework

Miskoziibiing is an Anishinaabeg community, therefore, Anishinaabeg ways of knowing were central to how this research was situated. In Kaandossiwin: How We Come to Know by Kathleen Absolon (2011) it is recognized that connection to land is important for Indigenous peoples, and they use a flower image to display a wholistic Indigenous methodology that supports self-determination and liberation. It is important to understand the need to advocate for Indigenous voices within and throughout this type of work, which is core to the principles of IFS. The parts of the flower identify the critical elements in an Indigenous paradigm: (1) the roots represent worldview; (2) the flower center represents the self; (3) the leaves represent the journey; (4) the stem represents critical consciousness and support; (5) the petals represent diversity in methods; (6) the environment represents the academic contexts within which Indigenous research methodologies grow.

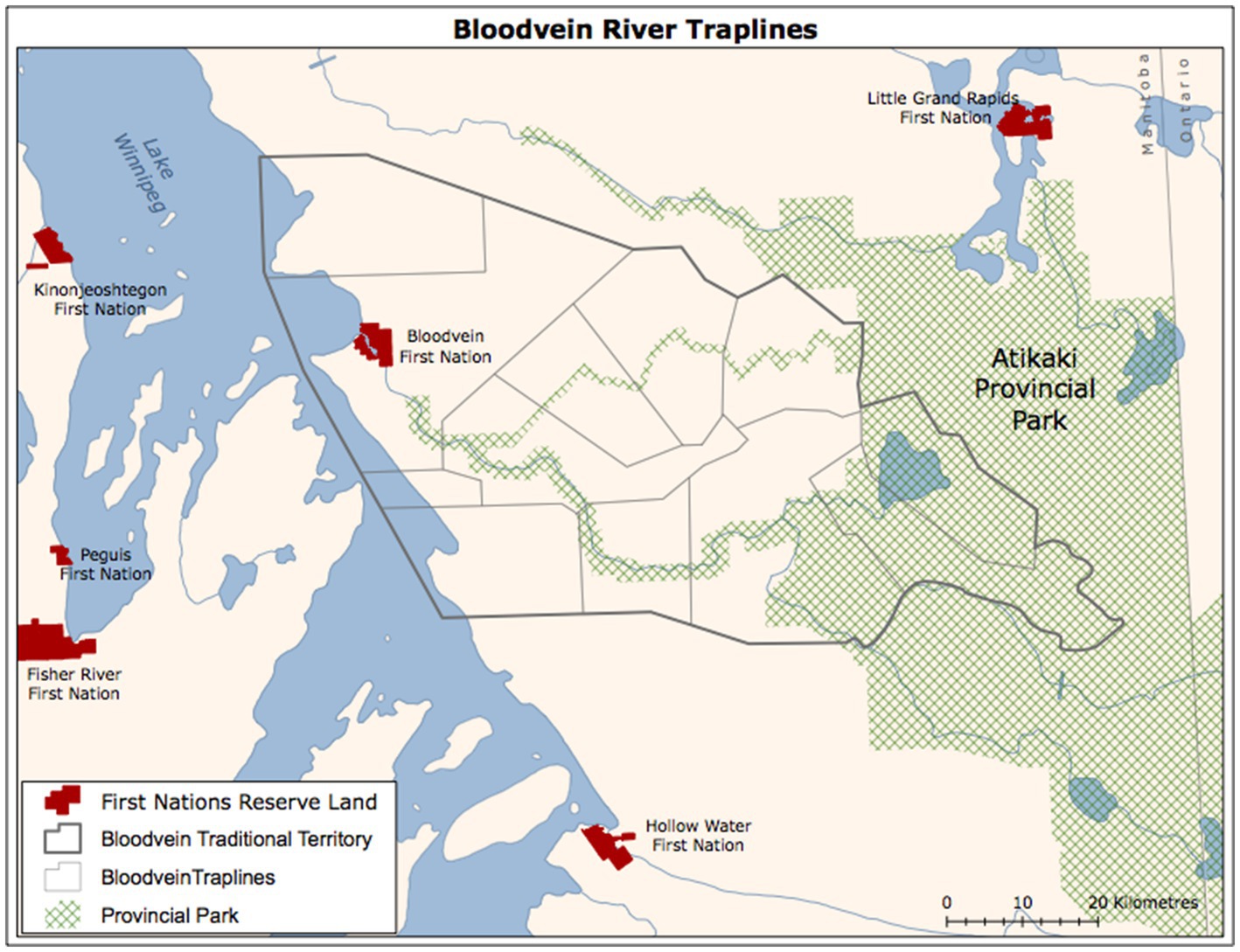

The community of Miskoziibiing was selected due to the distinct social and cultural values which provide rich historical teachings based on Indigenous food systems. The Anishinaabeg has occupied this area since time immemorial. The Anishinaabeg of Miskoziibiing self-identify with their territory and know their hunting, fishing, trapping, and harvesting areas. Learning about the territory and waterways, as well as ways to hunt, fish, trap, and harvest, was crucial for the survival of the Anishinaabeg of Miskoziibiing. Figure 1 shows the location of Miskoziibiing and Figure 2 indicates traditional traplines and traditional territories of Miskoziibiing (Bloodvein River First Nation and Whelan Enns Associates Inc, 2007).

A qualitative research design was used to explore connections and reciprocal relationships that the Anishinaabeg have with their traditional hunting, fishing, trapping, and harvesting areas (Creswell, 2009). Using a case-study and focusing on a single community allowed for observation of how the Anishinaabeg from Miskoziibiing locate traditional food: how they hunt, trap, fish, harvest, and prepare traditional foods. The research took place in Miskoziibiing, on the hunting grounds of the Anishinaabeg, as well as closer to the community where an all-weather road was developed. This all-weather road is located right through the hunting grounds of the Anishinaabeg and includes a bridge which runs over the Bloodvein River, and a creek called Long Body Creek. In addition to researching the traditional hunting territory of the Anishinaabeg, the focus was to develop an understanding of the ontology, epistemology, and axiology of the Anishinaabeg in Miskoziibiing.

2.3 Recruitment, data collection, and analysis

In June 2017, a meeting was held between the Miskoziibiing Band Council Leadership and the second author to provide information on the potential collaboration between the University of Winnipeg and Miskoziibiing for the benefit of the community. It was here that the Miskoziibiing leadership identified local knowledge keepers and Elders who had in-depth understandings of traditional foods, community culture, and critical values who may be interested in participating. Potential participants resided in both Miskoziibiing and Winnipeg. Potential participants were approached and asked if they would be willing to participate in an interview for this case study. Interviews were chosen as a conversational method which aligns with Indigenous worldviews of orality as a way of transmitting knowledge and upholding relationality (Kovach, 2009). Deloria (1996) interpreted oral tradition as the “non-western, tribal equivalent of science” (as cited in Absolon, 2011, p. 36). That knowledge explains the nature of the people’s physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual worlds. Ten Miskoziibiing Elders were interviewed from July to September 2017. Locations of interviews were determined by the Elders and were conducted at their residence, the local Child and Family Services office, and other locations within the community such as during a walk exploring the waterways and fishing, hunting, and harvesting practices occurred.

The research ethics protocol for this project was developed by two of the authors and then shared with the Miskoziibiing Band Council in June 2017 who provided feedback on the process. The Band Council approved the revised ethics protocol in October 2017 which was then reviewed and approved by the University of Winnipeg Huaman Research Ethics Office in May 2018. The protocol was continuously reviewed by the researchers as the Miskoziibiing Band Council and participating Elders made requests to ensure that all community protocols were being followed and participants were being respected throughout the process. The protocol included an interview checklist with an informed consent process where consent forms were reviewed with participants in detail with them before they were signed. An interpreter was also made available for translation of the consent forms and research questions. Two Elders were interviewed using the interpreter. Each participant was given the opportunity to remain anonymous if they chose and after discussions with the Elders it was decided to utilize their initials instead of pseudonyms. In addition to meeting Western academic ethical protocols, the study engaged in Indigenous research ethics protocols such as: (1) Offering of tobacco to Elders as a gift that signified respect and reciprocity (in addition to a cash honorarium through the SSHRC grant of the second author for this research); (2) focusing on the governmental structure within the community of Miskoziibiing and utilizing the concept of reciprocity; (3) participating in ceremonies performed during the research process and holding their cultural knowledges sacred (Kovach, 2009). In addition, there was a continued acknowledgement of participants in the research, there was no competition for ownership of the knowledge shared, it was owned communally as well as by the Elder sharing their stories.

During the research process, the data gathered was analyzed regularly and reviewed by participants. The traditional hunting, trapping, fishing, and harvesting locations were mapped, documented, and photographed throughout the research. They were shown to the research participants to ensure the information was recorded correctly. The collected data was transcribed from an audio format and then coded onto a spreadsheet. The responses were then coded using the open coding procedures, where each response was coded with a theme based on the literature review (Strauss and Corbin, 1998) and compared with the master coding sheet initially developed. The frequencies of codes were derived using the NVivo data analysis software. For the information gathered during the research process to remain valid, the data was analyzed alongside the participants to ensure everything was remembered and documented correctly.

3 Findings

3.1 Indigenous food teachings from Miskoziibiing: community values ongoing and critical

Anishinaabeg culture and traditions are essential to the community of Miskoziibiing. The interviews highlighted the importance of community sharing and intergenerational teaching in upholding IFS. These fundamental values are upheld within Miskoziibiing and are foundational in providing food security through Indigenous food systems, which was evident in the participants’ discussions around the sharing of core values through teachings, community food sharing, the transfer of skills and knowledge, and the importance of social learning.

Regarding IFS, sharing seemed to be of utmost importance to the participants, with one Elder stating, “Sharing was very, very important to the people; they always, always shared what they had” (FY, September 8, 2018). Participants stated several reasons as to why sharing was essential, but two reasons stood out among them. The first was situated in the past, where sharing was about survival, with Elder MF (September 9, 2018) explaining:

“…because that is the only way people survived long ago by sharing. They shared everything, not only in their territory but the rest of Turtle Island. They shared medicines, food, instruments for ceremonies, they shared everything.”

The second reason was situated in contemporary Indigenous contexts concerning the current market-based food governance. Traditional foods were not purchased; rather, they were shared among one’s family and community. MM (July 29, 2018) described this when they shared the following:

“In the summertime, when my dad killed a moose, or some member of the family killed a moose, they shared it to the community. They didn’t sell any moose, any of the stuff that was killed, they shared it with the community people. Your neighbor, they would come and get meat from my parents or other members of the community people. They would keep the heart, everything was not wasted, heart, liver, kidneys all that stuff that they saved was eaten by members of the family or they would give to other people. There was a lot of sharing.”

The Anishinaabe people of Miskoziibiing live with a distinctive worldview guiding how they interact with the land and food systems. In addition to sharing food, sharing the protocols around food gathering was highly important to the participants. This was mainly discussed in respecting the lives that were given up – both animal and plant life – to support and sustain their health, traditional knowledge, and lifestyles. The teachings surrounding these protocols have been passed down from generation to generation, which was made clear when Elder MF (September 9, 2018) spoke about the history of respect for life:

“Well, a long time ago, before there was reserves, people said that they were nomads, they followed the food, they followed the animals, and the teachings were to respect all life, to respect those animals because those animals provided food, medicines, clothing, shelter all those things they provided there was teachings to everything that had to do with animals, fish, birds and vegetation.”

There were two specific ways in which the values and protocols were practiced amongst participants while hunting and gathering. The first was through offerings to thank both the Creator and the animal or plant itself for the life sacrificed to feed their families and communities. MM (July 29, 2018) described the experience her brothers had while hunting with their father:

“My brothers I used to hear them, because when my dad went to hunt, they would see my dad putting tobacco out, already that time. Tobacco says if you take something off the land you put tobacco down and thank the creator. Cause the animals give themselves up to the people, to use as food.”

The second way these practices were illustrated was through concepts of sustainable hunting practices, wherein overharvesting was understood and monitored carefully to ensure that both the wildlife and the traditional practices and knowledge were passed down to future generations. Elder WY (August 9, 2018) shared about the intergenerational teachings of sustainable hunting practices:

“…the hunting ethics I guess, the sustainable practices, I guess were passed on down. Not to over kill the animals, that was passed on down to the younger hunters and we’re still going to be doing that sometime in the future here.”

The passing down of teachings also extended to understandings of the land. Many participants shared their personal experiences and stories they received from their fathers, uncles, and grandparents. Harvesting locations are not on a map but merely in the memory of the hunter, trapper, fisher, or harvester. Additionally, they are in areas that require knowledge of the land and waterways. Without this knowledge, a harvester would be putting themselves at risk. The ability to harvest food from the land requires skills, knowledge and cultural values. If either is lacking, survival may be jeopardized. When travelling up the local river, the hunter must navigate through the river’s rapids, avoiding the reefs’ rocks and acknowledging the strength of the current. The hunter must always be aware of his surroundings, especially when travelling on the river.

The participants shared how they began learning and engaging in traditional food practices as children and young adults. Each participant discussed practicing these activities – hunting, fishing, trapping, and harvesting with family or community. Intergenerational teachings were passed on to ensure the preservation of the knowledge and sustainability of the environment. Elder ES spoke Anishinaabemowin throughout her interview and spoke of her upbringing with her family (September 10, 2018):

“They helped each other, they knew by watching, they watched. Whatever, however people lived they just took the kids with them. Since they were children, they took them to trap lines and that’s how they learned, by just watching and learning.”

Working together as a family or community was incredibly important for sustainability and ensuring the whole community’s food security. Everyone contributed, and everyone benefited. Elder WY remembered how the food from hunting and fishing was shared with other community members. He also remembered being with extended family on these hunting and fishing trips. The following are recollections from Elder WY (August 29, 2018):

“…when I was taught growing up with hunting and fishing, it was my dad that taught me and some of the community members were involved as well, my cousins when we were growing up, we would go out hunting and they taught me quite a bit as well.”

Throughout the interviews, each Elder reminisced about their childhood and young adulthood. A common thread between each interview was how proud each Elder was of the teachings they received as children. Each participant shared that their teachings had come from their parents or their grandparents and that they shared their knowledge with their children. Elder SD spoke about sharing traditional knowledge with his children (September 9, 2018):

“I took him twice when he was just a little boy. That’s where he was, he was skinning under that moose neck area, he was cutting doing the same thing, he had a lot of moose meat.”

Elder SD also shared about learning from his Elders and passing on those learnings to his children (September 9, 2018):

“That’s the way my dad used to tell me, I’d listen to some old people, what they said. They still think of an old man there, I listen to him, I listen to the other people, I listen to Mike Green there. I listened to what’s his name; Benson there, Robert Benson. I heard my dad, and sometimes I would hear from umm, my uncle Shell there, but little did, Charlie Weshkup he told me a little bit. But all this was the way to live, the way to hunt. They explained everything to me; I took it and trying to explain that to my own boys now.”

3.2 Challenges and barriers to engaging in indigenous food sovereignty

Lifestyle and dietary changes have significantly impacted the Anishinaabeg of Miskoziibiing. These changes have impacted the youth of Miskoziibiing, who are losing their cultural heritage. The lifestyle and dietary practices of the Anishinaabeg of Miskoziibiing have drastically changed over the last 40 to 50 years.

Alongside the change in diet has come a change in lifestyle and activity level. In previous years, physical work was crucial for survival. Simple luxuries such as running water and electricity are new to the Anishinaabeg residents. While clean, running drinking water has enhanced the community’s well-being, it has eliminated the daily exercise of carrying water home. Elder ES talked about a lack of hard work that have harmed youth’s health (September 10, 2018):

“Life is different. They had to work for their food. They're not used to the way we used to eat before; they don't even carry water."

Many participants who were hunters, fishers, trappers, and harvesters acknowledged the importance of knowing the environment and the changing landscapes. As previously mentioned, the participants discussed lifelong teachings received from family members. These teachings provided safety and stability while harvesting food but were also impacted negatively by changing weather patterns and new developments in the area. Elder LK recalls having the ability to go berry picking anytime and anywhere. However, today, due to the changed landscapes, there are limited areas to pick berries. Elder LK (July, 2018) shared, “there used to be lots of blueberries, lots of strawberries, cranberries there was lots, raspberries, there was all kinds of berries, lots of them, saskatoons. Now there’s none.”

Elder MM made the same statement during her interview. The abundance of berries that community members could utilize as a treat have all but disappeared (July 29, 2018):

“I will say the berries, no more berries. There used to be all kinds of berries in Bloodvein, you could go in the bush or just around the reserve there would be lots of strawberries, blueberries, cranberries, all these things are gone, there's nothing growing anymore.”

To add the changes in how participants interacted with the land, many participants echoed challenges regarding policies and laws. In addition to navigating new physical landscapes, they are also navigating new political landscapes. These participants are still actively harvesting and have to abide by provincial regulations. Participants also raised concerns about hunters coming from outside of the community and hunting on Miskoziibiing’s traditional territory. Elder WY said (August 9, 2018):

“And of course there are regulations that are imposed on us and you know we've, with the encroachment of the all-weather road now and there's hunters coming to our area. And they don't hunt safely at all; they're noisy and drunk half of the time too. So those are the challenges and those are the things that the community has to deal with.”

Another challenge identified in the interviews was the growing costs of engaging in traditional hunting and harvesting practices. Travel expenses, such as using local airlines for transportation to traplines, are another expense. These modes of transportation and their associated expenses were unavailable in previous years. Elder SD shared, “I had this feeling, boy, it felt like I was going to kill a moose, but I had no way of going because I had no boat” (September 9, 2018). Elder VT also shared about access and affordability (August 31, 2018):

“Many of the people don't have guns anymore. They don't even have canoes, they don't even have boats, gas, all this. They don't have the proper knives, utilities that they need to go hunting, they don't have the proper tools for skinning the animals even. These things are very expensive. Guns are very expensive.”

The affordability challenge came with utilizing a boat and motor or floatplane as a transportation method to their harvesting locations. The interviews with the participants explained the hard work required to harvest, hunt, fish and trap. This lifestyle required physical and manual labor. Transportation to harvesting, hunting, fishing, and trapping locations required walking, running, paddling, and portaging. In the winter, dogsled and snowshoeing were required. Although these transportation methods may seem challenging, they were simply the way of life for the Anishinaabe. This not only affects their economic stability but their physical health. Elder WY shared (August 9, 2018):

"We've grown too accustom to the Western foods and all the can stuff, all the processed food and we've forgotten our traditional ways of obtaining our traditional food from our land."

3.3 Opportunities for indigenous food systems revitalization

In addition to the successes and challenges of engaging in traditional food practices, the participants also shared their recommendations for solutions. Indigenous communities across Canada are working to address their problems of food insecurity with the involvement of Elders, local band council leaders, community members, and community advocates. The interviews identified opportunities and strategies to revitalize traditional food systems in Miskoziibiing and promote IFS. Miskoziibiing has been promoting land-based teachings along with other resources, such as Jordan’s Principle, Child and Family Services, Miskooseepi School and Chief and Council. Many Miskoziibiing community members have been actively involved in assisting in getting these teachings to Miskoziibiing youth and young adults. The goal is to ensure traditional practices are passed down to the younger generation to ensure these teachings and livelihood is preserved. Any spring, summer, fall, and winter harvests are shared amongst community members. The teachings of the distribution of food are taught and shared with those that can no longer actively get out to harvest food.

The interviewed Elders shared how Indigenous food and land-based teachings were passed on to them through their grandparents and other knowledge keepers from their communities and is their responsibility to continue to teach future generations. Elder MF shared (September 9, 2018):

“It’s important to teach our children because it's our responsibility to teach them. If we don't teach them, it's going to come back to us and it's our fault … if things are not carried on, especially the traditional way of harvesting and eating and all those things. It’s our responsibility.”

Some interview participants emphasized that starting with teaching simple tasks like where and how to set up traps in different seasons and how to prepare wild meats for winter is essential, and others emphasized transmission of specific practices associated with traditional food hunting and harvesting. Elder MM confirmed this when they stated (July 29, 2018):

“I believe it will be nice if you had the younger people teach them how to clean these things, fish and all that. Teach them how to preserve them for the winter. They need to be taught, [traditional knowledge] needs to be brought back.”

Involvement of local Elders has been strongly practiced in the last five years and the Prevention Program actively involves their input in this development. Miskoziibiing recently developed cultural grounds just outside of the community perimeter called Circle of Voices in Anishinaabemowin it is Ke-wah-way-we-tung and was named after a Miskoziibiing Elder (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Participants of a sweat at circle of voices cultural grounds (courtesy of Angela Meeches).

The role of land-based learning by Elders and formal educational institutions such as schools was aptly emphasized by research participants. Elder LK shared that the early introduction of traditional foods was important for children and youth. Elder MF envisaged the community and the local schools having essential roles in intergenerational teachings of traditional food systems through planned interventions (September 9, 2018):

“They should implement programs in the school and in the community to address these concerns about living a good life. They need to take the children back to the land, back to the water, where they can once again listen to the spirit through the water, the wind, the mother earth, the stars, the sun, the moon, all that. Those were their teachers long time ago.”

There is a need for language revitalization in IFS. Elder YY explained the importance of language in traditional food systems (August 29, 2018):

“Language is critical in terms of how we harvest and how we prepare food, using the language … the younger generation also benefits from preparing the food, while harvesting the food, preparing the food in the language used.”

Community support is incredibly important for the success of IFS. For these recommendations to be implemented successfully, the support from the Miskoziibiing leadership is needed. This was stressed by the participants. The Chief and Council have already been involved with their members and partake in activities that happen in the community. Elder FY identified that there are already discussions within the community about organizing spaces for sharing knowledge (September 8, 2018): “Some people that were talking about starting some kind of knowledge learning like that with younger people.”

Elder SD mentioned that seeking more support from the Chief and Council would be beneficial to community members (SD, September 9, 2018): “and, the other thing I think about is to ask the Chief and Council when we need something that we could ask them, see if they can help us out.”

Elder MF (September 10, 2018) agreed that Chief and Council “should implement programs in the school and in the community to address these concerns so we can live the good life.”

4 Discussion

4.1 The Spirit of sharing: core values of Miskoziibiing’s indigenous food system

Power (2008) stated that food obtained from traditional food systems is critical to cultural identity, health and are essential factors for the survival of communities and their food systems. Food security requires a healthy environment where land and water are healthy and where animals consume good medicines in the environment (Shukla et al., 2019). Sharing protocols and values is part of the plethora of traditional food knowledge shared amongst the people of Miskoziibiing. The sharing of sustainable hunting and gathering food skills and knowledges are vital to food security. One of the reasons sharing is vital is that not all harvesters are fortunate enough to have a successful hunting, fishing, or trapping experience and harvesters often share their food with their communities. This was reiterated by Pawlowska-Mainville (2020) when she stated that “occasionally, even though everything is done right, nothing gets trapped or netted. If another harvester were fortunate, his catch would be shared with community members to ensure people would not go without” (p. 58). Fieldhouse and Thompson (2012) stated that the ability to harvest, share and consume traditional food is considered particularly important to Indigenous peoples’ food security. As reported in other studies from Northern Manitoba, Asatiwisipe Anishinaabeg food systems follow the practice of miigiwewinan, where meals of locally harvested wild rice or moose are shared within a community (Pawlowska-Mainville, 2020).

Miskoziibiing is one of four communities that comprise the Pimachiowin Aki World Heritage Project (2012). This partnership stresses the importance of sharing traditional teachings and values. Morrison (2011) identified that sharing traditional food practices has shaped, supported, and sustained distinct cultures, economies, and ecosystems. These partnerships display the concept of shared responsibilities, which comes full circle to the discussion of communal responsibility to share food within and throughout the community. Miltenburg et al. (2022) developed a framework on IFS initiatives which situates IFS in place, the connection to land that foundational to Indigenous food systems, this is further centered on core values of relationality, responsibility, and reciprocity. All of which are key for the function of relationships to the lands, waters, and other people. This considers how communities work with each other, are responsible to the land and each other, and give back.

Reciprocity plays a significant role in food sovereignty. It is one of the most basic values for many Indigenous groups (Scott and Feit, 1992). It is required to uphold responsibilities and relationalities, it strengthens relationships. This can happen when out on the land and waters engaging in food harvesting practices wherein a hunter express respect for the provision of healthy foods but also through the mutual relationships built with other community members. Feit (2014) furthers this concept of reciprocity when they discuss the social responsibilities of hunters who do intensive work to harvest food but share it with their kin, friends and family, who do not have the access, skills, or abilities to hunt. This is a form of social responsibility and mutual aid that is core to IFS values.

The literature and study participants also discuss the importance of sharing food for survival due to overpriced store-bought foods. Store bought foods often have higher costs in addition to being higher in sugar, salts, and unhealthy fats, which often results in higher rates of obesity and diabetes that plague Indigenous communities (Wilson and Shukla, 2020). As shared by participants, many community members, and Elders in Miskoziibiing now rely on store-bought goods and acknowledged the importance of sharing with other community members who may not have the means to provide for their families.

4.2 Affordability: evolving challenge

As Indigenous communities moved into the 21st century, the cost of living increased and caused harm. In the past, people hunted, fished, and gathered to provide food for their families. Affordability was not an issue for Anishinaabeg in the past. However, in recent years high costs associated with accessing traditional and healthy food has been a barrier (Wilson and Shukla, 2020). This was present in the findings in two ways, through the high costs of the tools needed to engage in traditional hunting and harvesting practices and increasing costs of store-bought foods.

Skinner et al. (2013) identified that traditional food activities have declined in recent decades, especially for young people. Many of these endeavors are seasonal and are limited by financial constraints for harvesting transportation and equipment. Affordability to maintain this lifestyle has challenged many Indigenous people locally and globally. The cost of transportation, whether by boat, vehicle, plane, or skidoo, and required equipment, such as guns, knives, fishing gear, camping gear, and sleeping gear, can create a barrier to IFS and security. The costs of buying hunting and harvesting tools and the lack of adequate transportation have reduced many young people’s time and active participation in traditional food activities (Skinner et al., 2013).

This disconnection from the land was echoed by Pawlowska-Mainville (2020) in her studies in Anishinaabe communities from boreal forest regions of Manitoba. Pawlowska-Mainville (2020) stated, “Whereas most consumers purchasing food from a grocery store rarely consider the aspect of land or what ecosystems their foods came from, Indigenous food systems are founded on the health of the land” (p.70). Utilizing the land, territory, and waterways is essential to the people of Miskoziibiing and high costs are having an incredible impact on this connection.

Providing for your family and community is crucial for food sovereignty. The cost for travel, such as airfare, to a trapline can cost upwards of $5000.00 CAD for a return trip, this does not include other costs such as purchasing and maintaining equipment or food for the trip, or the loss of income from taking time from jobs to engage in traditional harvesting. Costs continue to put a barrier in with local harvesters to commute to traditional harvesting territories, there is local resource assistance to ensure that local harvesters have the means to get to hunting sites for harvesting and teaching purposes. Despite this, affordability continues to be a barrier to traditional food systems and many community members have utilized local or urban grocery stores to provide for their families. Now, most families rely on store-bought items that have a higher financial cost than food harvested from the land. Both affordability challenges can lead to the destruction and loss of cultural values associated with hunting, harvesting, and food preparation practices in addition to negative impacts on their lifestyles and diets (Glacken, 2008; Wendimu et al., 2018).

4.3 Environmental and landscape changes

The changing climate, development, forestry, and commercialization has negatively affected ecosystems and access to traditional territories. Pawlowska-Mainville (2020) acknowledged that knowing the land and working hard is critical when trapping or hunting food in the boreal forest. Patience, persistence, and confidence in survival techniques are also needed for these activities. Environmental and landscape challenges must be taken seriously. Otherwise, the outcome can be detrimental and life changing. The most experienced harvester must always consider the elements, the landscape, and their experience as a harvester before setting out onto the land as it can pose challenges to any experienced harvester. These challenges can consist of fast-flowing or low water in the river, landscape erosion, or all-weather road erosion. The all-weather road, Provincial Road 34, passes through Miskoziibiing’s traditional hunting territories, and some traplines are accessible. This recently constructed all-weather road was completed in 2014. This all-weather road has brought regular traffic travelling through these areas, resulting in less wildlife, other harvesters from surrounding areas hunting in Miskoziibiing’s traditional territory, and increased pollution.

4.4 Lifestyle and dietary changes

These changes include fewer harvesting practices and an increase in store-bought goods in local stores and urban areas. The items purchased in local stores or urban areas are often unhealthy, increasing the risk of obesity and diabetes. Harvesting and consuming traditional foods must not only meet nutrition and health needs, but it must also satisfy traditional values (Wendimu et al., 2018). There are considerable economic, social, and cultural barriers to accessing nutritional foods such as “remote living, loss of cultural traditions, lack of economic stability, and am myriad of issues stemming from colonization” (Wilson and Shukla, 2020, p. 203). Food system impacts from colonization includes events like disconnection from traditional territories through the introduction of the reserve system, residential school system causing malnutrition and nutrition related diseases, and the forced dependance on store-bought foods which is directly linked to ongoing dietary diseases (Turner and Turner, 2008; Coté, 2016).

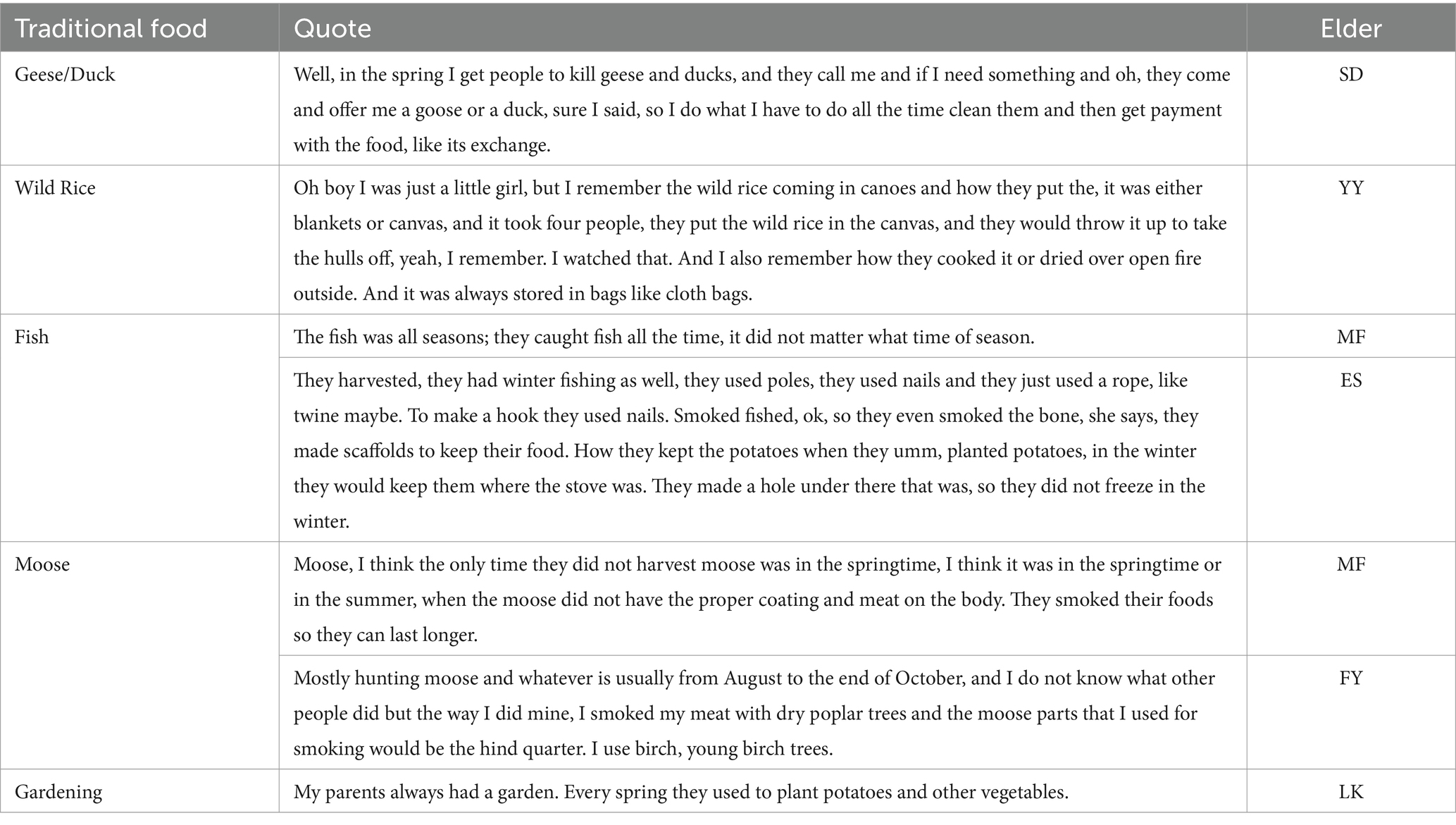

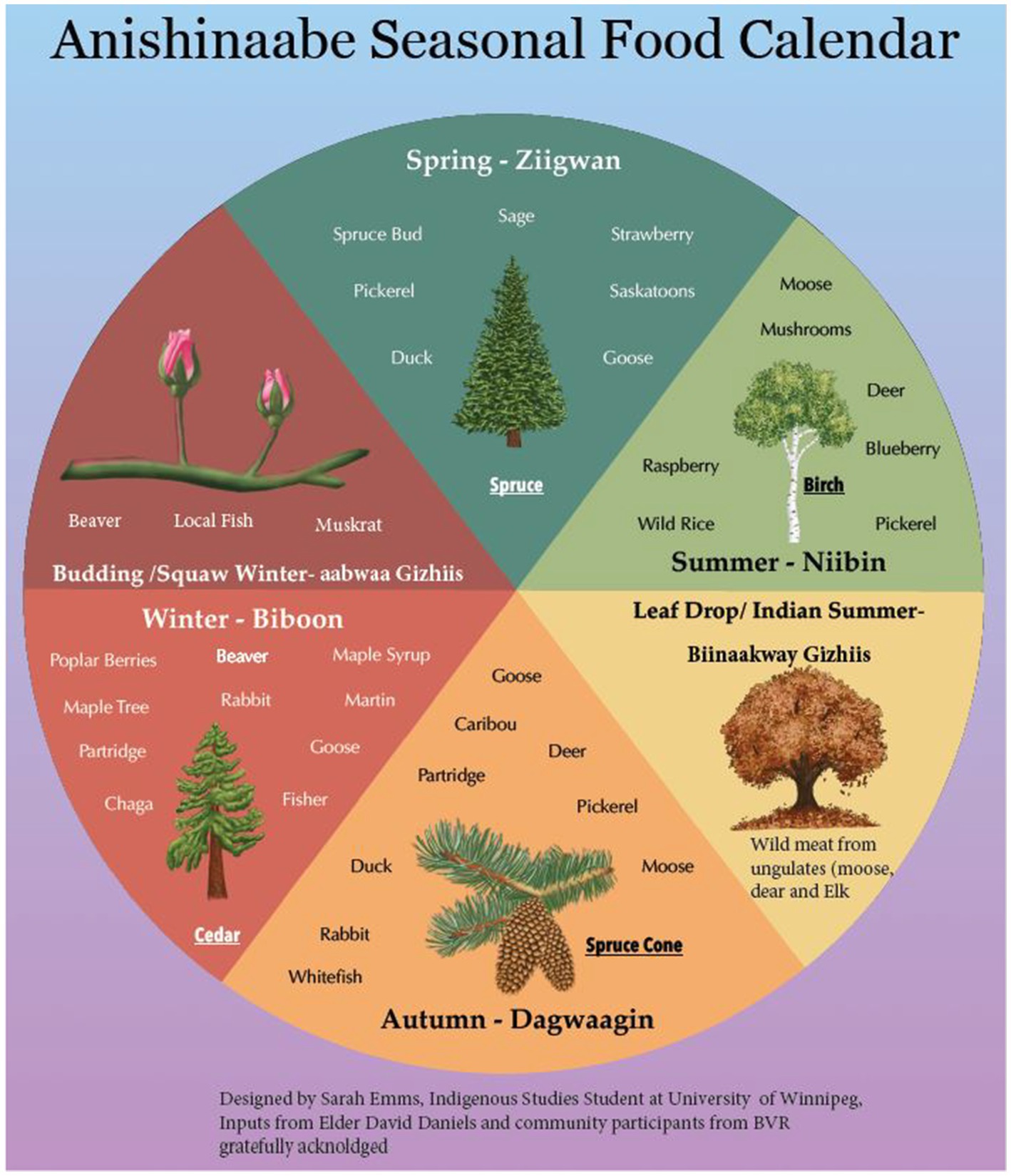

Throughout the interviews, the Elders discussed many foods historically important to their communities that played roles in the transmission of culture and values and contributed to mental, emotional, and physical health and well-being (Table 1; Figure 4). When discussing what was important to survival, Elder ES stated (September 10, 2018):

Table 1. Anishinaabe foods important to Miskoziibiing community members with quotes from Miskoziibiing elders.

Figure 4. Anishinaabe food calendar (designed by Sara Emms, developed from information from Elder David Daniels and Miskoziibiing Elders).

“All traditional foods like the beaver, the moose, the fish. So, we have to learn how to harvest the food, any kind of food that they had.”

4.5 Government policies, laws

IFS principles must be supported through government laws, policies, and legislation that does not undermine Indigenous food systems practices. This includes regulations and policies that determine who is eligible to possess firearms in Canada. These laws have created challenges for potential harvesters in Miskoziibiing. Many hunters need the means to travel to urban centers to apply for a Firearms Certificate (FAC), and they need the means to purchase supplies required to harvest, hunt, fish, and trap. Laws surrounding firearms have been put in place for protection. However, this has caused underlying challenges for many Indigenous people. Pawlowska-Mainville (2020) stated that present-day provincial resource management laws continue to affect the food sovereignty of another First Nation just 160 km from Miskoziibiing by regulating the harvesting season and firearm permits, changing laws on acceptable traps, and controlling the provincial registered trapline system. These laws can determine whether an individual will qualify to obtain the government regulated FAC (now known as a Possession and Acquisition License). If a person cannot obtain a FAC, they cannot hunt and need to depend on others to share their game. Turner and Turner (2008) further explained that food sovereignty is affected by introduced colonial forces:

"The exposure of First Peoples to colonial and imperial pressures led, among other things, to a decline in their food sovereignty and security, reflected in the loss of many dietary traditions and resource management practices” (p. 109).

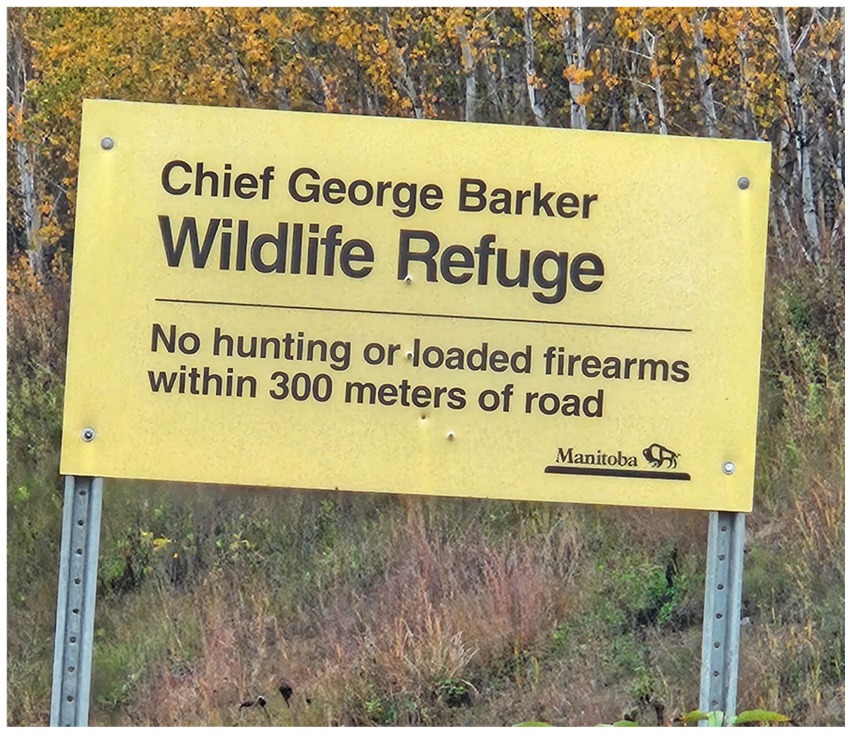

Another challenge is the ongoing encroachment of non-Indigenous hunters in Miskoziibiing and other Indigenous communities traditional hunting territories. All along on the Miskoziibiing all-weather road there are signs that state “Wildlife Refuge” however, the previous Provincial government continues to sell hunting licenses to non-Indigenous hunters (Figure 5). Campsites from non-local and non-Indigenous hunters can be found all along the roads and waterways between urban centers and Miskoziibiing. These hunters partake in illegal hunting practices such as spotlighting, the hunting of nocturnal animals using high powered lights, and the pollution of their campsites when they leave garbage strewn about. This encroachment continues to impact wildlife sustainability and jeopardizes the safety and well-being of local community members.

Miskoziibiing has a land use plan called the Pimitotah Land Use Plan, which the provincial government accepted. The land use plan states that the nation must be consulted if there is any activity on the traditional lands. Despite Miskoziibiing’s land use plan and the signage along the roadway, hunters still come into our territory in the fall. This makes one question whether the provincial government gave these hunters hunting licenses or were hunting illegally. The Pimitotah Land Use Plan for Miskoziibiing has designated areas that may be used for traditional and commercial activities. In this way, the land should be protected from companies entering the territory to engage in illegal activities. The provincial government is supposed to consult with the First Nation before any new endeavors are undertaken. Miskoziibiing hoped that establishing this land use plan would protect the land.

While many Indigenous peoples in Manitoba have differences, their similarities are related to the encroachment of regulations and policies on their harvesting lands and waterways. These regulations have made it difficult for Indigenous people to achieve food sovereignty. Beaudin-Reimer (2020) found that “harvesters who were 50 years of age or older expressed that legislation of the past had a damaging impact on Métis harvesters, their traditions, and their practices” (p. 244).

5 Community-led solutions based in cultural values

5.1 Intergenerational learning and transmission of food knowledges

Youth are an integral part of hunting and harvesting practices as they are not only helpers to their parents or those teaching them but also receive teachings to maintain and uphold these practices so they can be passed on to future generations. Sources like Gilpin and Hayes (2020) have stated that intergenerational teachings continue the intimate relationship with land and waters and plant the seeds of ancestral knowledge and prepare ways for generations to come. Intergenerational teaching is essential for the sharing and preservation of intergenerational knowledge and ensuring that knowledge stays within communities for generations (Poirier and Neufeld, 2023).

Introducing the younger generation to land-based or culturally based activities provides children and youth with skills such as hunting, fishing, trapping, harvesting, and preparing traditional foods. This ensures our traditional teachings continue to be practiced. Miskoziibiing utilizes and connects with Miskoziibiing knowledge keepers for continued transmission of teachings that have been passed on from generation to generation through The Prevention Program, which has a group of harvesters from the surrounding areas that have actively been harvesting for years connect with youth and knowledge keepers. Along with utilizing our traditional territory as their harvesting grounds, the Prevention Program also utilizes their funding to assist Elders to fly to their traditional traplines for harvesting. This provides the opportunity for young people to gain knowledge, skills and a sense of pride in being able to provide food for their families. Power (2008) identified that Indigenous children have yet to acquire the taste for traditional foods because they were not introduced to them at an early age. Having children and youth involved with harvesting traditional food has empowered them to develop that taste for traditional food. Gilpin and Hayes (2020) explain that community knowledge and traditional teachings become embodied when youth, parents, and grandparents participate in garden projects and hands-on learning experiences.

5.2 Local leadership

Community support is incredibly important for the success of IFS, this happens through supportive funding, legislation, and leading by example through engaging in these activities (Poirier and Neufeld, 2023). The involvement of community members, youth, adults and Elders, along with the Chief and Council, has been encouraging and promising. Encouragement and support from Miskoziibiing’s local leadership is crucial in ensuring these practices are not forgotten. The Chief and Council have been actively involved in encouraging local harvesters to become involved with the younger generations. This has been beneficial to many of our young men and women as many have addiction issues. Many resources have been working together to ensure numerous positive, culturally appropriate activities are taking place in the community. Our natural resources have utilized these resources to promote positive lifestyles within the community and the good life – Mino-bimaadiziwin.

6 Conclusions and future directions

The research participants shared stories and teachings of growing up with their parents and grandparents around traditional foods, which shaped their perspectives on the meaning of the Indigenous food systems that nourished them. Sustainability was considered as the most necessary value for the community, and the importance of reciprocity ensured that no one would go without it. This all comes together into a Miskoziibiing-specific version of a food systems governance framework which incorporates social dimensions and knowledge such as community values and intergenerational learning, and stewardship, economics, and governance through building healthy relationships within the community and with the land through food practices, self-governance, and sustainable food practices (Price et al., 2022).

Teachings of hunting, fishing, trapping, and harvesting were shared among community members. There were some similarities in the stories shared by the participants. Their memories and teachings were similar. Each participant acknowledged the communal values of sharing and the importance of sharing teachings with their grandchildren and their community. A continued practice of sharing food with families who have no hunters in the household is also critical and considered an important value to be learned by future hunters in the community. This is key in continuing food practices over generations and building ongoing food knowledges (Joseph and Turner, 2020). Food practices are integral in intergenerational knowledge building because their reciprocal shaping of social institutions, worldviews, customs, and values (Joseph and Turner, 2020).

Participants indicated their challenges in achieving food security and sovereignty for their families and communities. These challenges included dietary changes, environmental and landscape changes, policies, and laws which impact harvesting of Indigenous foods, recent infrastructure developments like the all-weather road, and affordability of food. These challenges only uncovered the tip of the iceberg. Underlying challenges to Indigenous food system-based security and food sovereignty include structural inequalities from the colonial legacy of residential schools and day schools, addictions to drugs and alcohol, lack of intergenerational transmission of knowledge, and a lack of access to affordable and nutritious food due to limited grocery stores. These colonial disruptions undermine self-determination, connections to community, transmission of food way knowledge, and the rights and responsibilities Indigenous peoples have to the land (Ruelle and Kassam, 2013; Ferreira et al., 2022; McKinley and Jernigan, 2023). Community members must travel over 100 km of gravel road and then the highway to get to the nearest town, which has grocery stores with more variety as well as a healthier selection of foods. Only some people in Miskoziibiing have the luxury of owning a vehicle to drive to go shopping and have the money to hire someone from the community to transport them to urban areas. That is why it is so important to community value and spirit of sharing traditional foods that are harvested.

Documenting oral history in Indigenous communities is crucial. The Anishinaabe Food Calendar depicts the rich traditional food heritage and healthy lifestyles that is part of Miskoziibiing’s own unique Indigenous food systems. The ability to pass on these valuable teachings to future generations provides a sense of relief as communities lose their Elders. The loss of an Elder is the loss of history and knowledge of the community. Each participant agreed that passing on these teachings would benefit younger generations. The participants identified that they would be willing to work with the youth, band council and the community members to ensure teachings are passed on through land-based programming. The participants shared about how they received teachings from their relatives. They expressed that traditional teachings and a spiritual connection to the land and waterways are crucial for the well-being of future generations.

Strengthening community food security and Indigenous food sovereignty by building upon teachings and Indigenous food knowledges is incredibly valuable for community of Miskoziibiing. This includes enhancing intergenerational transmission of Indigenous food knowledges through the active involvement of Elders and youths, reclaiming and revitalizing learning of traditional food knowledges and languages through education, and proactive involvement of local leadership. Indigenous food systems must include sociocultural meanings, acquisition and processing techniques, and use, consumption, and nutritional consequences of food. Traditional foods are valued from health, cultural, and spiritual perspectives (Shukla et al., 2019). This includes the acquisition and distribution of traditional foods and the practicing and strengthening of associated cultural values (Wendimu et al., 2018). Respecting these values are central to the reasserting the role of Indigenous-led governance for their food security and supports Indigenous food sovereignty.

Indigenous food sovereignty can and will look different in every community. Expanding beyond Miskoziibiing, the concepts discussed in this article can provide guidance and examples of how embracing local and Indigenous food systems values can strengthen Indigenous governance and contribute to the ongoing health, wellness, and sustainability of communities and the lands and territories that surround them. It directly correlates to ongoing struggles globally that Indigenous peoples face when their connections to their land, water, and food systems are threatened by colonization, cultural loss, climate change, land development, and incursion from outsiders who do not respect local land management protocols. Miskoziibiing’s work toward revitalizing their local food system through upholding their cultural values and strengths can be replicated in other communities as long as we engage in local and community-based values, protocols, and solutions.

Living off the land and providing for one’s family demonstrates food sovereignty. Traditional food ways improve not only physical health but convey and build important sociocultural meanings and values for sustainability of humans and all relatives. For example, reciprocity, discussed throughout this paper which is play an important role in forming relationships, social responsibility, mutual aid, and overall health and wellbeing in community’s like Miskoziibiing (Scott and Feit, 1992). They are acts of culture structured in concepts of resistance and resurgence. All of this is crucial for balance, wellbeing, and health (Robin et al., 2021). The values outlined in this paper are foundational to Miskoziibiing, its ongoing resilience, self-determination, and the sustainability for future generations. Promoting our traditional foodways will promote the well-being of the community members of Miskoziibiing. For the people of Miskoziibiing, we as researchers hope and pray to the Creator for Antawaynchikaywin Mino Pimatisiwin oonji (hunting and fishing for a good life).

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because datasets are co-owned by the lead author and research participants. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to bGlzYWN5b3VuZ0Bob3RtYWlsLmNvbQ==.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Winnipeg Human Research Ethics Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual (s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

LY: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. SS: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. TW: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) grant SSHRC-IDG: 430-2018-01013 and the University of Winnipeg.

Acknowledgments

Many people have helped throughout this research which was a part of thesis by the First Author for her Master of Arts in Indigenous Governance Degree at the University of Winnipeg. The researchers thank the family of first author, the community members and Chief and Council of Bloodvein River First Nation, Southeast Student Services – Richard Grisdale, and various members of Indigenous Studies Department from the University of Winnipeg -including Jazmin Alfaro, Crystal Flamand, and Erin Froese. The content of this manuscript has previously appeared in the First Author’s master’s degree thesis published by the University of Winnipeg.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Allard, D. (2023). Kitchen table politics: bannock and Métis common sense in an era of nascent recognition politics. Native Am. Indig. Stud. 10, 36–68. doi: 10.1353/nai.2023.a904182

Beaudin-Reimer, B. (2020). “Perspectives from Métis harvesters in Manitoba on concerns and challenges to sustaining traditional harvesting practices and knowledge: a distinctions-based approach to indigenous food sovereignty” in Indigenous food systems: Concepts, cases and conversations. eds. P. Settee and S. Shukla (Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars), 229–251.

Bloodvein River First Nation and Whelan Enns Associates Inc . (2007) Our heritage river: the river of our people CHRS conference. Talk presented at Canadian Heritage river system conference, Winnipeg.

Coté, C. (2016). Indigenizing food sovereignty: revitalizing indigenous food practices and ecological knowledges in Canada and the United States. Humanities 5:57. doi: 10.3390/h5030057

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches. 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Deloria, V.Jr. (1996). Reserving to themselves: Treaties and the powers of Indian tribes. Ariz. L. Rev. 38:963.

Feit, H. A. (2014). “Hunting and the quest for Power: relationships between James Bay Crees, the land and developers” in Native peoples: The Canadian experience. eds. C. Roderick Wilson and C. Fletcher. 4th ed (Toronto: Oxford University Press Canada).

Ferreira, C., Gaudet, J. C., Chum, A., and Robidoux, M. A. (2022). Local food development in the moose Cree first nation: taking steps to build local food sustainability. Food, Cult. Soc. 25, 561–580. doi: 10.1080/15528014.2021.1913557

Fieldhouse, P., and Thompson, S. (2012). Tackling food security issues in indigenous communities in Canada: the Manitoba experience. Nutr. Dietet. 69, 217–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0080.2012.01619.x

Gilpin, E. M., and Hayes, M. (2020). “A collection of voices: land-based leadership, community wellness, and food knowledge revitalization of the WJOLELP Tsartlip first nation garden project” in Indigenous food systems: Concepts, cases and conversations. eds. P. Settee and S. Shukla (Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars), 111–118.

Glacken, J. B. (2008). “Promising practices for food security” in Draft summary report (Ottawa: First Nations and Inuit Health Branch, Health Canada).

Haman, F., Fontaine-Bisson, B., Batal, M., Imbeault, P., Blais, J. M., and Robidoux, M. A. (2010). Obesity and type 2 diabetes in northern Canada’s remote first nations com- munities: the dietary dilemma. Int. J. Obes. 34, S24–S31. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.236

Holmes, D. A. (2020). Researcher positionality—a consideration of its influence and place in qualitative research—a new researcher guide. Shanlax Int. J. Educ. 8, 1–9. doi: 10.34293/education.v8i2.1477

Jernigan, V. B. B., Maudrie, T. L., Nikolaus, C. J., Benally, T., Johnson, S., Teague, T., et al. (2021). Food sovereignty indicators for indigenous community capacity building and health. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5:704750. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2021.704750

Joseph, L., and Turner, N. J. (2020). “The old foods are the new foods!”: Erosion and revitalization of indigenous food systems in northwestern North America. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 4, 1–20. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2020.596237

Kovach, M. (2009). Indigenous methodologies: Characteristics, conversations and contexts. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Kuhnlein, H. (2020). “Celebrating indigenous food systems: restoring indigenous food traditions, knowledges, and values for a sustainable future” in Indigenous food systems: Concepts, cases and conversations. eds. P. Settee and S. Shukla (Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars).

Martens, T. R. (2021). Food as helper, food as healer: How Cree elders incorporate food into helping and healing practices and the implications for indigenous food sovereignty. [Ph.D. thesis]. Winnipeg (MB): University of Manitoba.

McKinley, C. E., and Jernigan, V. B. B. (2023). “I don’t remember any of us … having diabetes or cancer”: how historical oppression undermines indigenous foodways, health, and wellness. Food and Foodways 31, 43–65. doi: 10.1080/07409710.2023.2172795

Michnik, K., Thompson, S., and Beardy, B. (2021). Moving your body, soul, and heart to share and harvest food: food systems education for youth and indigenous food sovereignty in Garden Hill first nation Manitoba. Can. Food Stud. 8, 111–136. doi: 10.15353/cfs-rcea.v8i2.446

Miltenburg, E., Neufeld, H. T., and Anderson, K. (2022). Relationality, responsibility and reciprocity: cultivating indigenous food sovereignty within urban environments. Nutrients 14:1737. doi: 10.3390/nu14091737

Morrison, D. (2011). “Indigenous food sovereignty: a model for social learning” in Food sovereignty in Canada: Creating just and sustainable food systems. eds. H. Wittman, A. A. Desmarais, and N. Wiebe (Halifax, NS: Fernwood Publishing), 97–113.

Pawlowska-Mainville, A. (2020). “Aki Miijim (land food) and the sovereignty of the Asatiwisipe Anishinaabeg boreal Forest food system” in Indigenous food systems: Concepts, cases and conversations. eds. P. Settee and S. Shukla (Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars), 57–82.

Pimachiowin Aki World Heritage Project (2012). The land that gives life: nomination for inscription on the World Heritage list. Winnipeg, MB: Pimachiowin Aki Corporation.

Poirier, B., and Neufeld, H. T. (2023). “We need to live off the land”: an exploration and conceptualization of community-based indigenous food sovereignty experiences and practices. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20:4627. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20054627

Power, E. M. (2008). Conceptualizing food security for aboriginal people in Canada. Can. J. Public Health 99, 95–97. doi: 10.1007/BF03405452

Price, M. J., Latta, A., Spring, A., Temmer, J., Johnston, C., Chicot, L., et al. (2022). Agroecology in the north: centering indigenous food sovereignty and land stewardship in agriculture “frontiers”. Agric. Hum. Values 39, 1191–1206. doi: 10.1007/s10460-022-10312-7

Robin, T., Burnett, K., Parker, B., and Skinner, K. (2021). Safe food, dangerous lands? Traditional foods and indigenous peoples in Canada. Front. Commun. 6:9944. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.749944

Ruelle, M. L., and Kassam, K. S. (2013). Foodways transmission in the standing rock nation. Food and Foodways 21, 315–339. doi: 10.1080/07409710.2013.850007

Scott, C. H., and Feit, H. A. (1992). Income security for Cree hunters: Ecological, social and economic effects. Montreal: McGill University Programme in the Anthropology of Development (PAD), Monograph Series.

Settee, P., and Shukla, S. (Eds.). (2020). Indigenous food systems: concepts, cases, and conversations. Canadian Scholars.

Shukla, S., Alfaro, J., Cochrane, C., Mason, G., Dyck, J., Beudin-Reimer, B., et al. (2019). Nimíciwinán, nipimátisiwinán – “our food is our way of life”: on-reserve first nation perspectives on community food security and sovereignty through oral history in Fisher River Cree nation Manitoba. Can. Food Stud. 6, 73–100. doi: 10.15353/cfs-rcea.v6i2.218

Skinner, K., Hanning, R. M., Desjardins, E., and Tsuji, L. J. (2013). Giving voice to food insecurity in a remote indigenous community in subarctic Ontario, Canada: traditional ways, ways to cope, ways forward. BMC Public Health 13, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-427

Strauss, A., and Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.

Tamang, J. P., Watanabe, K., and Holzapfel, W. H. (2016). Review: diversity of microorganisms in global fermented foods and beverages. Front. Microbiol. 7:377. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00377

Turner, N., and Turner, K. (2008). Where our women used to get the food: cumulative effects and loss of ethnobotanical knowledge and practice; case study from coastal British Columbia. Botany 86, 103–115. doi: 10.1139/B07-020

Vernon, R. V. (2016). A native perspective: food is more than consumption. J. Agric. Food Syst. Commun. Dev. 5, 137–132,

Wendimu, M. A., Desmarais, A. A., and Martens, T. R. (2018). Access and affordability of “healthy” foods in northern Manitoba? The need for indigenous food sovereignty. Can. Food Stud. 5, 44–72. doi: 10.15353/cfs-rcea.v5i2.302

Keywords: indigenous values, social values, cultural values, food sovereignty, food system governance, indigenous food security, traditional foods, self-determination

Citation: Young L, Shukla S and Wilson T (2024) Indigenous values and perspectives for strengthening food security and sovereignty: learning from a community-based case study of Misko-ziibiing (Bloodvein River First Nation), Manitoba, Canada. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8:1321231. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2024.1321231

Edited by:

Ina Vandebroek, University of the West Indies, JamaicaReviewed by:

Janelle Baker, Athabasca University, CanadaAshley McGuigan, University of Hawaii, United States

Copyright © 2024 Young, Shukla and Wilson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shailesh Shukla, cy5zaHVrbGFAdXdpbm5pcGVnLmNh

Lisa Young1

Lisa Young1 2

2 Taylor Wilson

Taylor Wilson