- 1Institute of Development Research, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna, Austria

- 2Department of Sociology, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria

- 3Department of Geography, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria

The current food regime has experienced a multidimensional crisis, driving further unjust and unsustainable development. Various food alternatives address these challenges by promoting different modes of alternative production and consumption. However, they are not extensively theoretically addressed within the food regime literature. Thus, we suggest analyzing food regimes with further social science theories to explore food alternatives and their possible contributions to transforming the present food regime. Drawing on a combination of critical state theory, the social capital concept, and territorial approaches, we introduce an interdisciplinary conceptual framework called values-based modes of production and consumption. We assume that food alternatives are based on values other than economic ones, such as democracy, solidarity, or trust. The framework allows examining perspectives of transformation that focus on conflict or cooperation and how they can be interlinked. We aim to determine entry points for analyzing food alternatives within the current food regime because these enable an exchange between debates that are usually taking place alongside each other. By linking them, we aim to inspire further insightful interdisciplinary research.

1 Introduction

The multidimensional crisis of the current food regime has recently become apparent. The financial and economic crisis since 2007 has intensified the pressure on land and people. Transnational corporations have increasingly become financialized, and investment and pension funds consider land an asset to diversify their portfolios (Fairbairn, 2014; Plank and Plank, 2014). Large-scale agricultural enterprises grow flex crops (Borras et al., 2016) as cash crops, partly for agrofuel production (Borras, 2010; McMichael, 2010; Plank, 2017), employing unfair trade regimes that aggravate the energy and climate crisis (Franco and Borras, 2021), and foster land grabbing (Borras et al., 2011; McMichael, 2012; Hall et al., 2015) and green grabbing (Fairhead et al., 2012). With the coronavirus pandemic and the war in Ukraine, the multidimensional crisis has intensified (Van Der Ploeg, 2020; Gras and Hernández, 2021), providing challenges and opportunities for food alternatives.

Social movements, such as the environmental or food sovereignty movement, are prominent examples of fostering food alternatives to transform the current food regime (Patel, 2009; Edelman, 2014; Alonso-Fradejas et al., 2015; Bernstein, 2016). By promoting alternative ways of production and consumption, such as community-supported agriculture or regional food chains (Clancy and Ruhf, 2010), the food sovereignty movement aims to change the dominant capitalist mode of production and consumption dependent on capital accumulation and economic growth (Schermer, 2015). However, most food alternatives, defined as alternatives in production, networks, and economic practices (Rosol, 2020), work locally. How they can be upscaled to have a more extensive influence on the food regime remains an open question.

Friedmann and McMichael (1989), who developed the food regime approach in the 1980s, more recently suggested “widen[ing] the conversation” (Friedmann, 2016) on food regime theory and enriching it with other theoretical approaches to examine social change (see also Friedmann, 2009). We follow this suggestion to examine the transformation potential of the current food regime through local food alternatives. A joint effort of society at large is needed to encounter crises and foster transforming the present food regime; hence, various theoretical perspectives and food alternatives and their context-specific characteristics and motivations must be included in the analysis (Penker et al., 2023). Thus, we also consider food alternatives that do not explicitly identify with the food sovereignty agenda or are not openly motivated to change the current food regime (Stevenson et al., 2007). Initiatives such as organic regions or traditional farming cooperatives are more commonly addressed in the alternative food network literature than in the food regime literature, where they are framed as value-based supply chains relying on values other than economic ones (Stotten et al., 2017; Stotten and Froning, 2023).

Therefore, this contribution presents an interdisciplinary conceptual framework to analyze how food alternatives transform corporate and state power in the food regime through a values-based approach. By linking critical state theory with the concept of social capital and territorial approaches, we examine actors and institutions, values, and their multiscalar interplay. We call this framework values-based modes of production and consumption and investigate it using analytical perspectives that focus on conflict or cooperation within the present food regime.

2 Food alternatives in the current food regime

Food regime theory is known for analyzing global changes within the agricultural food system from a long-term, political-economic perspective. Its strength lies in examining the stabilizing dimensions of a food regime by examining investment flows, trade relations, and interstate relations and their socioecological effects (Bernstein, 2016). Overall, transformation in food regime theory has so far been a question of how food regimes change in an ex-post analysis, that is, how we progress from the first (1870s–1930s) British-centered regime to the second (1950s–1970s) US-dominated regime to the third (from the 1980s to the present) corporate-driven food regime (McMichael, 2013). Friedmann (2009) questioned this last shift, arguing that a hegemonic international currency is missing. Other researchers have questioned the corporate character as the only primary driver of the current food regime and discussed a neoliberal food regime (Otero, 2012), highlighting the role of the state and biotechnology, or a post-neoliberal food regime (Tilzey, 2019), where competing states secure capital accumulation.

As Friedmann (2016) stated, “food regime analysis is most useful today as part of a wider set of analyses of transitions. Therefore, we draw on debates on the role of actors and institutions, values, and their multiscalar interplay within the current food regime to determine how they can contribute to the interdisciplinary analysis of its transformation. Transformation requires different leverage points (Abson et al., 2017) where intent (i.e., values) and design (i.e., institutions) embedded in materiality are the most significant levers for systemic change. We analyze niche activities and their interplay with higher spatial scales (Plank, 2022; Barlow et al., 2024).

2.1 Actors and institutions

Analyzing social movements to understand agency within the current food regime, focusing on resistance, has garnered substantial attention (Borras et al., 2008; Fairbairn, 2008; Holt Giménez, 2011). Notably, social movement scholars have researched strategies regarding how the food sovereignty movement is organized (Claeys and Duncan, 2019; Duncan et al., 2021), emphasizing the desire for democratic control of food systems (Patel, 2009; Desmarais et al., 2017). In addition, research on the role of the state in the food regime has been increasing in the last few years (Otero, 2012; Akram-Lodhi, 2015; Pritchard et al., 2016; Tilzey, 2017, 2018; Belesky and Lawrence, 2019; Jakobsen, 2019; Tilzey, 2019). While Otero (2012) referred to the neoliberal state, which, via “neoregulation,” supports transnational corporations through the state’s absence, Pritchard et al. (2016) highlighted the possibility of rights-based food agendas within a nation-state.

Tilzey (2019) argued for integrating a Poulantzian understanding of the state as a social relation in food regime research, highlighting the role of strategic selectivities inherent in the capitalist state (see Poulantzas, 2014). As Tilzey asserted, food regimes arise from what he called the “state-capital nexus” (2018, 2019). In this understanding, a food regime is no more than the combination and articulation in the international arena of national food systems, reflecting the dominant interests of the hegemonic states and their capitalist interests. The state represents a heterogeneous ensemble of institutions interwoven with the economy (i.e., shaping economic activities resulting from capitalist development). The state secures specific economic interests and activities through its legal and institutional structure (Jessop, 2002, 2007). The more opposed actors are to a hegemonic regime, the less likely they are to incorporate their interests into it (Tilzey and Potter, 2016). Actors and institutions incorporated into a regime can be analyzed through political projects. For instance, (Tilzey (2017)) differentiated these into hegemonic, sub-hegemonic, alter-hegemonic, and counter-hegemonic projects.

2.2 Values

According to McMichael (2009), the current food regime is defined by a set of rules institutionalizing corporate power through the World Trade Organization as the leading institution, finding its expression in free trade agreements. As noted, others have questioned this leading value of corporatism (Otero, 2012; Tilzey, 2019). Friedmann (2006) called it “corporate-environmental” because ecological farming, fair trade, and social justice have become increasingly popular and have been inscribed into the food regime. With the failures of neoliberalism to provide food security, social and economic justice in trade relations, and environmental sustainability in the face of the climate crisis (Smith et al., 2010), food alternatives based on values such as solidarity, trust, justice, and environmental sustainability are essential for change (Campbell, 2009).

A social capital perspective can explore how such values in values-based supply chains (Stevenson and Pirog, 2008; Fleury et al., 2016; Stotten et al., 2017) are established, lived, and transmitted along the food chain, especially across spatial distance. Drawing on Polanyi (1978), strong social capital reflects the embeddedness of the economy in society (Carroll and Stanfield, 2003), and it has been argued that “the market economy remakes society, in the process destroying solidarity and destabilizing the substantive economy thereby ultimately threatening social disintegration” (Stanfield, 1986, pp. 11). The role of values must be empirically analyzed, regarding whether values foster food alternatives or are simply co-opted into the food regime and represent a form of localized capitalism (Tilzey, 2017; Stotten, 2024).

2.3 Multiscalar interplay

Within the food regime literature, transformation is often addressed from a top-down perspective, analyzing capital accumulation processes, dominant power constellations, and class relations (Friedmann and McMichael, 1989; Bernstein, 2016). Nevertheless, more recently, national and local scales have been examined owing to their transformation potential. Localizing “food from nowhere” to “food from somewhere” (Campbell, 2009; McMichael, 2009) has been identified as a crucial but not exclusive element of food sovereignty (Robbins, 2015), where production is localized and certified trade links markets over distance (Burnett and Murphy, 2014; Plank et al., 2023). These diverging quests have resulted in a tension that shapes the corporate food regime, “whereby a ‘food from nowhere’ regime is in constant dialectic with a ‘food from somewhere’ regime” (Smith et al., 2010, p. 147).

Food production and consumption are intrinsically linked to physical space and its materiality. A context-specific territorial lens (Dorn and Hafner, 2023, p. 30ff) helps explain processes of scaling and connecting the organizational-structural (institutional) and relational to physical space (Sack, 1986; Raffestin, 2012; Haesbaert, 2013), addressing the well-articulated critique by Potter and Tilzey (2005, p. 583) regarding the cognitive dissonance between the focus on geographical settings versus approaches detached from space. Bridging the physical geographical focus with actor networks and their inherent power relations, reframed as an “agricultural restructuring as a sociopolitical project” (Tilzey, 2005, pp. 584–585) is useful for an in-depth analysis of the multiscalarity and connection between the organizational-structural, relational, and physical spaces. Socioecological change may occur locally but is interlinked with strategies and power relations between actors and institutions on multiple scales.

3 Values-based modes of production and consumption as an interdisciplinary conceptual framework

This paper proposes an interdisciplinary conceptual framework to analyze food alternatives within the current food regime, building on insight from debates on actors and institutions, values, and their multiscalar interplay. This framework is rooted in critical state theory, the social capital concept, and territorial approaches. The role of actors and institutions and the interdependency between food alternatives and the state are highlighted, drawing on critical state theory (Jessop, 2002, 2007). How food alternatives are simultaneously embedded in the current food regime and how they aim to transform it by scaling their values-based approach to the national scale can thus be investigated. This approach enables the analysis of the political-institutional setting to support food alternatives from the perspective of broader socioeconomic development.

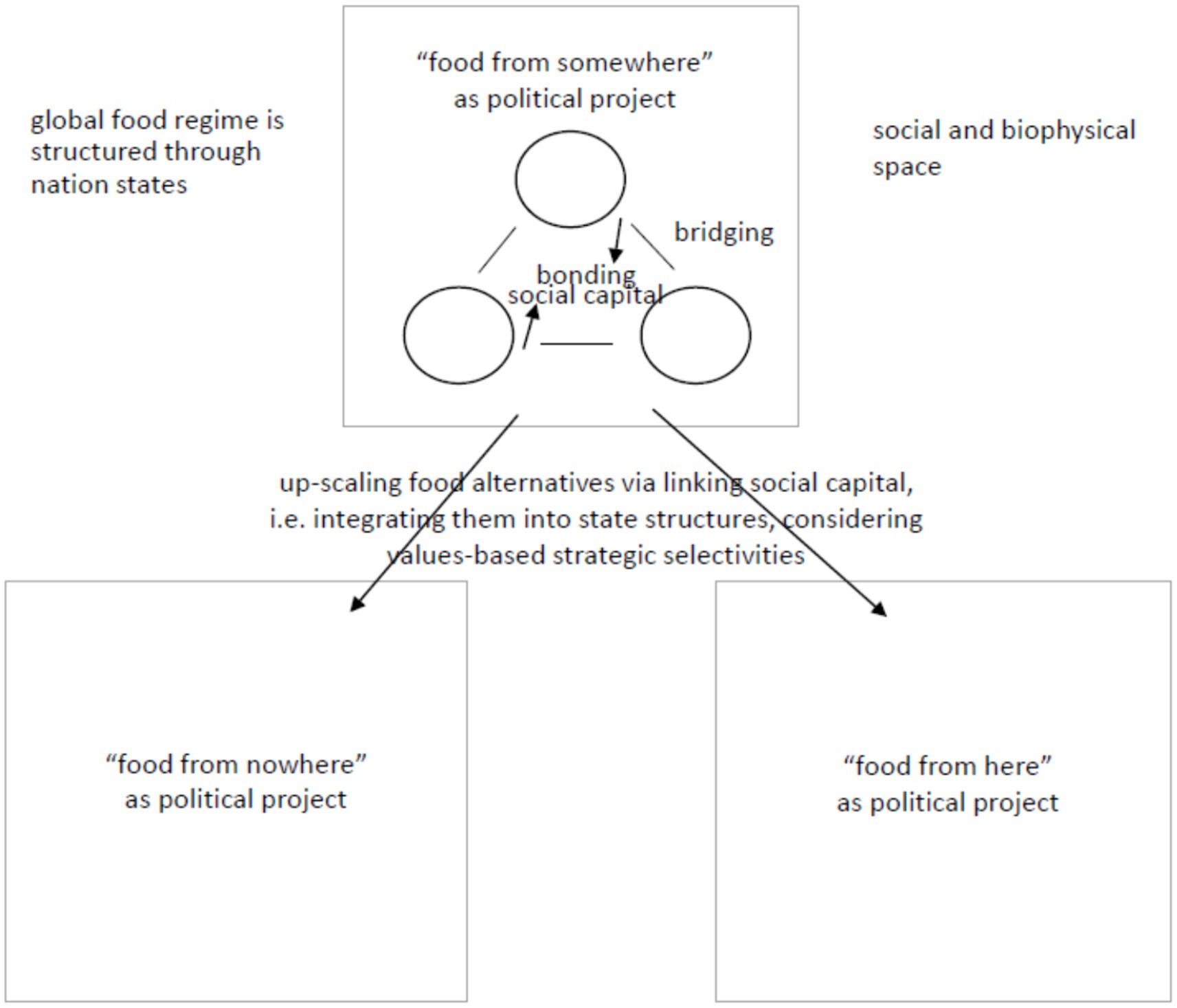

Furthermore, this approach allows for an examination of barriers that food alternatives encounter at the institutional level and the strategies to address them. The concept of social capital (Putnam, 2000) facilitates the examination of underlying values, such as trust, of the actors in the supply chains of food alternatives and how these values influence activities across spatial distances. By articulating critical state theory with territoriality (Dorn and Hafner, 2023), we link food alternatives and their values to how the food regime is articulated within the nation-state. Power relations between actors and institutions and materiality are examined on various spatial scales to explore how political-economic interests unfold in the respective institutional settings. Based on this interdisciplinary approach to values-based modes of production and consumption (Figure 1), we identify conflict- and cooperation-centered perspectives on transformation and how they link to a specific territory.

Figure 1. Interdisciplinary conceptual framework of values-based modes of production and consumption to examine food alternatives transforming the current food regime.

3.1 Perspectives on transformation

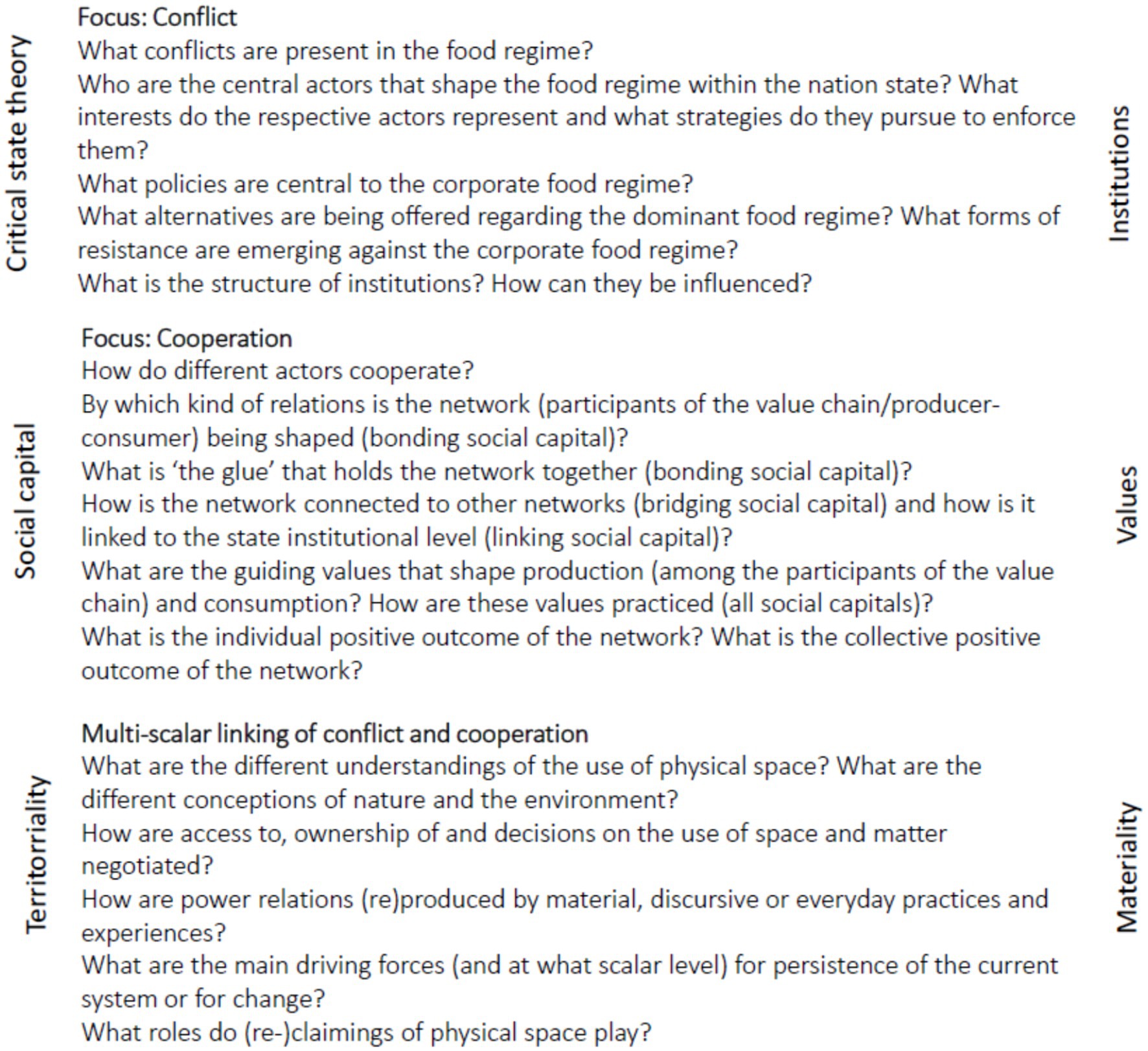

Various disciplines have distinct analytical added value. To understand the transformation dynamics within the current food regime, we combine theoretical perspectives and use them as different entry points for an analysis of conflict, cooperation, or both (Figure 2). Further, we focus with our analysis of the state and values of the food initiatives on leverage points which can have a great potential for transformation.

Figure 2. Guiding questions for analysis of conflict and cooperation in processes of transformation.

3.1.1 Conflict-focused perspective on transformation

One central entry point for analyzing transformation strategies and their barriers is the current conflicts in the food regime. From a critical state-theoretical perspective, various actors, such as parties, interest groups, nongovernmental organizations, and social movements, shape the food regime due to their interests and strategies. Drawing on the concept of strategic selectivities (Jessop, 2010), we can analyze how specific interests are inscribed into the state, whereas others are not. For example, the specific interests and strategies imprinted in today’s food regime are dominated by those of transnational corporations (McMichael, 2009). For instance, this situation can be observed in policy-making (Torrado, 2016) when powerful actors push to retain direct payments or allow glyphosate within the European Union.

A further example is the transformation of the food regime in India and South Africa, where the right to food has been incorporated into state structures (Pritchard et al., 2016; Jakobsen, 2019). Political projects allow the joint action of diverse social forces by articulating their interests and strategies within the state. Certain projects operating in specific contexts might achieve hegemony (Staatsprojekt Europa, 2014; Brand et al., 2021; Voigt et al., 2024). Political projects differ in terms of values, interests and strategies of their actors (see Staatsprojekt Europa, 2014). Regarding food system transformation as understood by food regime theory, two major ideal-type political projects can be identified: “food from nowhere” as the dominant one and “food from somewhere” as fostered by food alternatives.

“Food from nowhere” (McMichael, 2009) is a hegemonic project that involves specific institutional structures concerning food production, processing, and consumption. Outcomes and constituent components of this project are highly unequal, for instance, private property-based ownership structures of land as well as the phenomena of land concentration and grabbing driven by the financialized capitalist system, the food industry, and major retail chains. “Food from somewhere” (McMichael, 2009), in contrast, focuses on food alternatives (i.e., how social movements become engaged in political action, how they aim to shape food policies or institutions, and how they aim to change access to land). Food alternatives, such as community-supported agriculture or regional food chains, can coexist with or challenge the dominant food regime (Plank et al., 2020) and are supported by the food sovereignty movement protesting, e.g., against implementing the Common Agricultural Policy at the national level (ÖBV-Via Campesina Austria, 2020). When investigating options for transformation, critical questions arise: How is “food from somewhere” supported or hindered by state structures? These are ideal-type projects on a high level of theoretical abstraction, the concrete articulation of which must be examined for each state. For Austria, e.g., Salzer (2015) demonstrated how small-scale farmers are embedded in the hegemony of the conservative political structures of their political economy. Thus, Schermer (2015) underlined that a sole focus on regional production, called “food from here,” stabilizes the dominant food regime in an Austrian context and hinders the emergence of radical alternatives, such as community-supported agriculture. Depending on the respective examined state, these characteristics must be explored.

3.1.2 Cooperation-focused perspective on transformation

Another starting point for analyzing transformation is examining a certain expression of values (e.g., how to foster cooperation within and between food alternatives). Better than a critical state-theoretical perspective, the social capital approach explains structures leading to (or constraining) cooperation in such food alternatives. According to Putnam (1993), the accumulation of social capital within a region enhances economic cooperation (see also Woolcock, 2001; McShane et al., 2016). According to this theory, robust social networks in the form of local associations contribute to the effective functioning of democracy and stimulate economic growth. Putnam argued that engagement in voluntary associations generates social capital, fostering trust in societal interactions. This trust encourages individuals to cooperate with the confidence that others will reciprocate (Rothenstein, 2005). In contrast to Bourdieu (1980), who understood social capital as one component of symbolic capital together with cultural and economic capital, exploring its role in reproducing social hierarchies, Putnam focused more on the mechanisms that strengthen the integration of communities through values (for a detailed elaboration of the concept, see Siisiäinen, 2003).

Putnam (2000) introduced the distinction between bonding and bridging social capital (Figure 1), the latter relating to the concept of weak ties (Granovetter, 1973). Bonding social capital creates internal cohesion in a system, such as a community or value chain, and is characterized by shared values, such as trust, loyalty, solidarity, and mutual assistance. For instance, traditional farming cooperatives rely on solid bonding social capital, empowering them to shape the regional food production system based on shared values (Schermer, 2009). In contrast, bridging social capital does not refer to close interpersonal interaction within groups sharing narrowly aligned values or value systems, but links individuals or social groups across social difference, enabling inter-group learning processes (Woolcock, 1998). For instance, small-scale producers are organized in different lobby groups (e.g., the association ‘Bio Austria’ of organic farmers in Austria) strengthened by horizontal integration through bridging social capital and contributing to mutual learning processes.

Finally, linking social capital, as developed by Woolcock (2001) to consider vertical power relations in capital terms and reflects the capability of individuals or social groups to link to the level of the state, enabling, e.g., the best use of the legal framework for their purposes. Combinations of bonding and bridging social capital are needed to maximize the positive political outcomes of cooperation (Woolcock and Narayan, 2000). If shaping access to the state institutional level through linking social capital (Woolcock, 2001), such combination facilitates economic activities to the benefit of regional development (Schermer, 2009). While acknowledging the merits of Putnam’s social capital approach with regard to studies on food system transformation, we are aware of neoliberal tendencies inscribed in the social capital concept depending on how it is being used analytically and embedded theoretically, particularly when emphasizing the community as the sole source of social, economic and political support or individual responsibility, or when neglecting the exclusionary effects of (especially) bonding social capital and ensuing social stratification or uncritically interpreting the notion of linking capital (Ferraigina and Arrigoini, 2018).

Critics have scrutinized the Putnamian perspective for assuming that elevated social capital invariably yields positive outcomes (e.g., King et al., 2019; Baycan and Öner, 2023). They emphasized that high social capital could also result in adverse economic consequences or, regarding spatial configurations, lead to path dependencies and lock-ins (see also McShane et al., 2016). However, other scholars (e.g., Svendsen and Svendsen, 2000; Schermer, 2009) have underscored that the availability of bonding, bridging, and linking social capital is vital for the long-term economic performance of collective farmers’ marketing initiatives. The role of democracy, trust, and equal chances for a profit demonstrates the importance of social capital for the performance of dairy cooperatives (Svendsen and Svendsen, 2000). Urban and rural communities might differ regarding the amount and type of social capital and how they interlink. For instance, rural residents may display higher levels of bonding social capital than urban dwellers, whereas bridging social capital might be better developed in urban regions (Sørensen, 2016). We thus suggest to investigate both amount and composition of social capital in specific local and regional spatialities of the food regime in a nation-state context to better understand potentials and constraints of food alternatives.

3.1.3 Linking conflict and cooperation-focused perspectives on transformation

A third, territorial approach links conflictive and cooperative transformation perspectives and examines them on scalar levels, including the materiality of food production. In this way, the interconnectedness of the biophysical materiality of food production with social relationships and processes of negotiation, power structures, and strategies across scales can be addressed (Dorn and Hafner, 2023). From an analytical standpoint, territoriality allows for the examination of how individuals and communities relate to, are part of, and interact with the physical space and place (Dorn, 2021). This approach calls for reassessing and abandoning container thinking for a more integrative understanding of inter- and intrasectionality between the physical and social space, defined by the actors’ interpretation of how control is exercised. Consequently, territory is not a fixed entity but must be continuously (re-)produced by material, discursive, and everyday practices (i.e., territorialization processes; Dietz and Engels, 2018).

Political decisions set the frame for forms of agricultural activity. Actions such as supporting farm size upscaling, facilitating monocultures, and applying genetically manipulated crops favor large-scale investors and agribusinesses and hold additional relevance for neighboring small-scale alternative production sites. For example, once the large-scale application of glyphosate is allowed and exercised, neighboring organic or agroecological production fields experience the effects of glyphosate carried by wind, contaminating organically produced crops (Lapegna, 2016). This materialization of state regulations results in a discrepancy between the alternative ideals and values of food production and their possibility in practice, emphasizing the necessity to explore how the interrelationships between humans and the environment are understood. This example could be extended, as “food from nowhere” (the large-scale application of glyphosate use in industrialized agriculture being one specific practice which is characteristic of this political project) and “food from somewhere” (as, e.g., connected with agroecological production) represent two fundamentally distinct methods of producing space. In other words, they constitute different territorialities that may overlap and often enhance the contestation around territories (see Porto-Gonçalves and Leff, 2015). For example, social movements that strive for food sovereignty are always about autonomy and access to physical land. In doing so, they do not only challenge the free market hegemony but also the territorial sovereignty of nation-states (Copeland, 2019; Storey, 2020).

Drawing on the perspectives of conflict and cooperation, we have covered a broader mix of transformation opportunities, representing possible entry points for empirical research. We suggest questions (Figure 2) to guide the interdisciplinary analysis.

3.2 Operationalizing values-based modes of production and consumption

In concluding, we want to demonstrate, how the analysis of the three analytical perspectives outlined above can be combined within three steps. First, we propose examining how the food regime is articulated in the nation-state and how it is composed by political projects to obtain an overview of the challenges regarding the transformation of the food regime. Interests, strategies, and power relations within the food regime are made explicit by identifying critical actors, institutions, and policies and defining the food regime within the state. Various forms of state-capital relations (e.g., national developmentalist or competition-orientated states) must be considered (Tilzey, 2018).

Second, we suggest to focus on local and regional food alternatives and to elucidate their values. We investigate how values are transmitted across communities, horizontal distances, and vertical scales using bonding, bridging, and linking social capital and are shaping relationships between producers, processors, and consumers. In this way, we examine how values motivate agency within food alternatives, how they influence social practices on various scales, how values are transmitted among the actors in the food chain, and how they can contribute to institutionalizing food alternatives nationally. Some food alternatives openly and explicitly aim to transform the corporate food regime, whereas others do not have a conscious political understanding of their activities.

Third, we suggest to combine the analysis of territoriality with the bonding, bridging, and linking of actors within and across alternative food initiatives. Actors share interests, values, and understanding of ideal human-environmental relationships, which are visible in food production, distribution, and consumption. Every day, hands-on multisensory and visceral experiences (Hafner, 2022) related to “food from somewhere” strengthen the link between the tangible and intangible characteristics of food production, distribution, and consumption. The performative element of experiencing food requires asking how diverse social groups perceive their physical environment to operationalize territoriality. A research agenda on territoriality includes actors’ access to and use of space and the (re-)production and materialization of power relations. This approach is connected to values and how they are selected by state structures (i.e., institutions, discourses, and technologies).

4 Conclusion

We focused on food alternatives against the background of multiple crises in the current food regime. By widening the theoretical perspective of food regime theory through critical state theory, the social capital concept, and territorial approaches, we introduced an interdisciplinary conceptual framework to examine food alternatives as values-based models of production and consumption. Critical state theory offers an analytical perspective on societal conflicts, whereas approaches to social capital focus on the ability to cooperate. Territoriality links these two perspectives and anchors actors’ social interactions and intra-actions in the biophysical space, arguing that each social interaction is also materialized, produced, and reproduced spatially. The framework examines necessary prerequisites for upscaling food alternatives and provides a perspective on the barriers to this process.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

CP: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. RS: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. RH: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The study was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) [ZK-64G].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abson, D. J., Fischer, J., Leventon, J., Newig, J., Schomerus, T., Vilsmaier, U., et al. (2017). Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio 46, 30–39. doi: 10.1007/s13280-016-0800-y

Akram-Lodhi, A. H. (2015). Accelerating towards food sovereignty. Third World Q. 36, 563–583. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2015.1002989

Alonso-Fradejas, A., Borras, S. M., Holmes, T., Holt-Giménez, E., and Robbins, M. J. (2015). Food sovereignty: convergence and contradictions, conditions and challenges. Third World Q. 36, 431–448. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2015.1023567

Barlow, N., Schulken, M., and Plank, C. (2024). How and Who? The Debate About a Strategy for Degrowth, in De Gruyter Handbook of Degrowth. Eds Eastwood, L., Heron K., Herausgeber (Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter), 109–28.

Baycan, T., and Öner, Ö. (2023). The dark side of social capital: a contextual perspective. Annals of Regional Science, 70, 779–798. doi: 10.1007/s00168-022-01112-2

Belesky, P., and Lawrence, G. (2019). Chinese state capitalism and neomercantilism in the contemporary food regime: contradictions, continuity and change. J. Peasant Stud. 46, 1119–1141. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2018.1450242

Bernstein, H. (2016). Agrarian political economy and modern world capitalism: the contributions of food regime analysis. J. Peasant Stud. 43, 611–647. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2015.1101456

Borras, S. M. (2010). The politics of biofuels, land and agrarian change: Editors' introduction. J. Peasant Stud. 37, 575–592. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2010.512448

Borras, S. M., Edelman, M., and Kay, C. (2008). Transnational agrarian movements confronting globalization. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Borras, S. M., Franco, J. C., Isakson, S. R., Levidow, L., and Vervest, P. (2016). The rise of flex crops and commodities: implications for research. J. Peasant Stud. 43, 93–115. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2015.1036417

Borras, S. M., Hall, R., Scoones, I., White, B., and Wolford, W. (2011). Towards a better understanding of global land grabbing: an editorial introduction. J. Peasant Stud. 38, 209–216. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2011.559005

Bourdieu, P. (1980). Le Capital Social. Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, no. 18. pp. 2–3.

Brand, U., Krams, M., Lenikus, V., and Schneider, E. (2021). Contours of historical-materialist policy analysis. Crit. Policy Stud. 1–18. doi: 10.1080/19460171.2021.1947864

Burnett, K., and Murphy, S. (2014). What place for international trade in food sovereignty? J. Peasant Stud. 41, 1065–1084. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2013.876995

Campbell, H. (2009). Breaking new ground in food regime theory: corporate environmentalism, ecological feedbacks and the ‘food from somewhere’ regime? Agric. Hum. Values 26, 309–319. doi: 10.1007/s10460-009-9215-8

Carroll, M. C., and Stanfield, J. R. (2003). Social capital, Karl Polanyi, and American social and institutional economics. J. Econ. Issues 37, 397–404. doi: 10.1080/00213624.2003.11506587

Claeys, P., and Duncan, J. (2019). Do we need to categorize it? Reflections on constituencies and quotas as tools for negotiating difference in the global food sovereignty convergence space. J. Peasant Stud. 46, 1477–1498. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2018.1512489

Clancy, K., and Ruhf, K. (2010). Is local enough? Some arguments for regional food systems. Choices 1, 1–5. doi: 10.22004/ag.econ.93827

Copeland, N. (2019). Linking the defence of territory to food sovereignty: peasant environmentalisms and extractive neoliberalism in Guatemala. J. Agrar. Change 19, 21–40. doi: 10.1111/joac.12274

Desmarais, A. A., Claeys, P., and Trauger, A. (2017). Public policies for food sovereignty: Social movements and the state. Earthscan from Routledge. London: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group.

Dietz, K., and Engels, B. (2018). “Raum, Natur und Gesellschaft” in Theorien in der Raum- und Stadtforschung: Einführungen. eds. J. Oßenbrügge, A. Vogelpohl, and J. Affolderbach, vol. 2 (Münster: Westfälisches Dampfboot), 78–96.

Dorn, F. (2021). Changing territorialities in the argentine Andes: lithium Mining at Salar De Olaroz-Cauchari and Salinas Grandes. Erde.

Dorn, F., and Hafner, R. (2023). Territory, territorialty and territorialization in global production networks. Población Soc. 30, 27–47. doi: 10.19137/pys-2023-300102

Duncan, J., Claeys, P., Rivera-Ferre, M. G., Oteros-Rozas, E., van Dyck, B., Plank, C., et al. (2021). Scholar-activists in an expanding European food sovereignty movement. J. Peasant Stud. 48, 875–900. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2019.1675646

Edelman, M. (2014). Food sovereignty: forgotten genealogies and future regulatory challenges. J. Peasant Stud. 41, 959–978. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2013.876998

Fairbairn, M. (2008). Framing resistance: international food regimes and the roots of food sovereignty. Available at: https://minds.wisconsin.edu/bitstream/handle/1793/31140/1115475.pdf?sequenc.

Fairbairn, M. (2014). ‘Like gold with yield’: evolving intersections between farmland and finance. J. Peasant Stud. 41, 777–795. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2013.873977

Fairhead, J., Leach, M., and Scoones, I. (2012). Green grabbing: a new appropriation of nature? J. Peasant Stud. 39, 237–261. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2012.671770

Ferraigina, E., and Arrigoini, A. (2018). Are young people outsiders and does it matter? Mark Smith; Tiziana Nazio; Clémentine. European Youth Forum Moyart (Youth employment, Policy Press), 30–32.

Fleury, P., Lev, L., Brives, H., Chazoule, C., and Désolé, M. (2016). Developing mid-tier supply chains (France) and values-based food supply chains (USA): a comparison of motivations, achievements, barriers and limitations. Agriculture 6:36. doi: 10.3390/agriculture6030036

Franco, J. C., and Borras, S. M. (2021). The global climate of land politics. Globalizations 18, 1277–1297. doi: 10.1080/14747731.2021.1979717

Friedmann, H. (2006). “From colonialism to green capitalism: social movements and emergence of food regimes” in New directions in the sociology of global development, vol. 11 (Bingley: Emerald (MCB UP) Research in Rural Sociology and Development), 227–264.

Friedmann, H. (2009). Discussion: moving food regimes forward: reflections on symposium essays. Agric. Hum. Values 26, 335–344. doi: 10.1007/s10460-009-9225-6

Friedmann, H. (2016). Commentary: food regime analysis and agrarian questions: widening the conversation. J. Peasant Stud. 43, 671–692. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2016.1146254

Friedmann, H., and McMichael, P. (1989). AGRICULTURE and the STATE SYSTEM: the rise and decline of National Agricultures, 1870 to the present. Sociol. Rural. 29, 93–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9523.1989.tb00360.x

Granovetter, M. (1973). The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 78, 1360–1380. doi: 10.1086/225469

Gras, C., and Hernández, V. (2021). Global Agri-food chains in times of COVID-19: the state, agribusiness, and agroecology in Argentina. J. Agrar. Change 21, 629–637. doi: 10.1111/joac.12418

Haesbaert, R. (2013). “A global sense of place and multi-territoriality: notes for dialogue from a ‘peripheral’ point of view” in Spatial politics: Essays for Doreen Massey. eds. D. Featherstone and J. Painter. 1st ed (Malden, Mass: Wiley-Blackwell), 146–157.

Hafner, R. (2022). “Viszerale Methoden” in Mehr-als-menschliche Geographien. Schlüsselkonzepte, Beziehungen und Methodiken. eds. C. Steiner, G. Rainer, V. Schröder, and F. Zirkl (Stuttgart: Steiner), 297–316.

Hall, R., Edelman, M., Borras, S. M., Scoones, I., White, B., and Wolford, W. (2015). Resistance, acquiescence or incorporation? An introduction to land grabbing and political reactions ‘from below’. J. Peasant Stud. 42, 467–488. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2015.1036746

Holt Giménez, E., and Shattuck, A. (2011). Food crises, food regimes and food movements: rumblings of reform or tides of transformation? J. Peasant Stud. 38, 109–144. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2010.538578

Jakobsen, J. (2019). Neoliberalising the food regime ‘amongst its others’: the right to food and the state in India. J. Peasant Stud. 46, 1219–1239. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2018.1449745

Jessop, B. (2007). “Spatial fixes, temporal fixes and spatio- temporal fixes” in David Harvey: A critical reader. eds. N. Castree and D. Gregory, vol. 3 (Malden, Mass: Blackwell), 142–166.

King, J., Hine, C. A., Washburn, T., Montgomery, H., and Chaney, R. A. (2019). Intra-urban patterns of neighborhood-level social capital: a pilot study. AHealth Promot Perspect. 9:150–155. doi: 10.15171/hpp.2019.21

Lapegna, P. (2016). Genetically modified soybeans, agrochemical exposure, and everyday forms of peasant collaboration in Argentina. J. Peasant Stud. 43, 517–536. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2015.1041519

McMichael, P. (2009). A food regime genealogy. J. Peasant Stud. 36, 139–169. doi: 10.1080/03066150902820354

McMichael, P. (2010). Agrofuels in the food regime. J. Peasant Stud. 37, 609–629. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2010.512450

McMichael, P. (2012). The land grab and corporate food regime restructuring. J. Peasant Stud. 39, 681–701. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2012.661369

McMichael, P. (2013). Food regimes and agrarian questions. Agrarian change and peasant studies 2. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing.

McShane, C. J., Turnour, J., Thompson, M., Dale, A., Prideaux, B., and Atkinson, M. (2016). Connections: the contribution of social capital to regional development. Rural. Soc. 25, 154–169. doi: 10.1080/10371656.2016.1194326

ÖBV-Via Campesina Austria . (2020). Positionspapier Zur Agrarpolitik Nach 2020 Der Österreichischen Berg- Und Kleinbäuer_innen Vereinigung. Available at: https://www.viacampesina.at/wp-content/uploads/delightful-downloads/2020/05/OeBV_Positionspapier-Agrarpolitik-nach-2020_final.pdf. (Accessed February 27, 2022).

Otero, G. (2012). The neoliberal food regime in Latin America: state, agribusiness transnational corporations and biotechnology. Can. J. Dev. Stud. 33, 282–294. doi: 10.1080/02255189.2012.711747

Penker, M., Brunner, K. M., and Plank, C. (2023). APCC Special Report: Strukturen für ein klimafreundliches Leben (APCC SR Klimafreundliches Leben) In. Ernährung. [Görg, C., V. Madner, A. Muhar, A. Novy, A. Posch, K. W. Steininger und E. Aigner (Hrsg.)]. Springer Spektrum: Berlin/Heidelberg. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-66497-1_9

Potter, C., and Tilzey, M. (2005). Agricultural policy discourses in the European post-Fordist transition: neoliberalism, neomercantilism and multifunctionality. Progress in Human Geography. 29:581–600. doi: 10.1191/0309132505ph569oa

Plank, C., Görg, C., Kalt, G., Kaufmann, L., Dullinger, S., and Krausmann, F. (2023). ‘Biomass from somewhere?’ Governing the spatial mismatch of Viennese biomass consumption and its impact on biodiversity. Land Use Policy 131:106693. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2023.106693

Plank, C. (2017). “The Agrofuels project in Ukraine: how oligarchs and the EU Foster agrarian injustice” in Fairness and justice in natural resource politics. eds. M. Pichler, C. Staritz, K. Küblböck, C. Plank, W. Raza, and F. R. Peyré (London: Routledge).

Plank, C. (2022). “An overview of strategies for social-ecological transformation in the field of food” in Degrowth and Strategy: How to bring about social-ecological transformation. eds. N. Barlow, L. Regen, N. Cadiou, E. Chertkovskaya, M. Hollweg, and C. Plank (Verena Wolf: Mayfly).

Plank, C., Hafner, R., and Stotten, R. (2020). Analyzing values-based modes of production and consumption: community-supported agriculture in the Austrian third food regime. Österreich Z. Soziol. 45, 49–68. doi: 10.1007/s11614-020-00393-1

Plank, C., and Plank, L. (2014). The Financialisation of farmland in Ukraine. J. Entwicklungspolitik 30, 46–68. doi: 10.20446/JEP-2414-3197-30-2-46

Polanyi, K. (1978). The Great Transformation: Polit. U. Ökonom. Ursprünge Von Gesellschaften U. Wirtschaftssystemen. 1. Aufl. Suhrkamp-Taschenbücher Wissenschaft 260. [Frankfurt (Main)]: Suhrkamp.

Porto-Gonçalves, C. W., and Leff, E. (2015). Political ecology in Latin America: the social re-appropriation of nature, the reinvention of territories and the construction of an environmental rationality. Desenv Meio Amb 35:43543. doi: 10.5380/dma.v35i0.43543

Pritchard, B., Dixon, J., Hull, E., and Choithani, C. (2016). ‘Stepping Back and moving in’: the role of the state in the contemporary food regime. J. Peasant Stud. 43, 693–710. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2015.1136621

Putnam, R. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. 14th Edn. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press.

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Raffestin, C. (2012). Space, territory, and territoriality. Environ. Plann. D 30, 121–141. doi: 10.1068/d21311

Robbins, M. J. (2015). Exploring the ‘localisation’ dimension of food sovereignty. Third World Q. 36, 449–468. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2015.1024966

Rosol, M. (2020). On the significance of alternative economic practices: Reconceptualizing alterity in alternative food networks. Econ. Geogr. 96, 52–76. doi: 10.1080/00130095.2019.1701430

Sack, R. D. (1986). Human territoriality: Its theory and history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Salzer, I. (2015). “Agrarsektor: Es grünt nicht grün?” in Politische Ökonomie Österreichs: Kontinuitäten und Veränderungen seit dem EU-Beitritt. ed. BEIGEWUM (Wien: Mandelbaum), 77–89.

Schermer, M. (2009). “Sozialkapital Als Faktor Für Den Erfolg Gemeinschaftlicher Vermarktungsinitiativen” in Neue Impulse in Der Agrar- Und Ernährungswirtschaft?! ed. H. Peyerl, vol. 18 (Wien: Facultas), 101–110.

Schermer, M. (2015). From “food from nowhere” to “food from here:” changing producer–consumer relations in Austria. Agric. Hum. Values 32, 121–132. doi: 10.1007/s10460-014-9529-z

Siisiäinen, M. (2003). Two concepts of social capital: Bourdieu vs. Putnam. Int. J. Contemp. Sociol. 40, 183–204.

Smith, K., Lawrence, G., and Richards, C. (2010). Supermarkets' governance of the Agri-food supply chain: is the 'Corporate-Environmental' food regime evident in Australia? Int. J. Sociol. Agric. Food 17, 140–161.

Sørensen, J. F. L. (2016). Rural–urban differences in bonding and bridging social capital. Reg. Stud. 50, 391–410. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2014.918945

Staatsprojekt Europa . (2014). Kämpfe Um Migrationspolitik: Theorie, Methode Und Analysen Kritischer Europaforschung. Transcript Verlag. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1fxgk5.

Stanfield, J. R. (1986). The economic thought of Karl Polanyi: Lives and livelihood. 2nd Edn. London: Palgrave Macmillan Limited.

Stevenson, G. W., and Pirog, R. (2008). “Values-based supply chains: strategies for Agrifood Enterprises of the Middle” in Food and the mid-level farm: Renewing an agriculture of the middle. eds. T. A. Lyson, G. W. Stevenson, and R. Welsh (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 119–143.

Stevenson, G. W., Ruhf, K., Lezberg, S., and Clancy, K. (2007). “Warrior, builder, and weaver work: strategies for changing the food system” in Remaking the north American food system: Strategies for sustainability. eds. C. C. Hinrichs and T. A. Lyson (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press), 33–62.

Stotten, R. (2024). Heterogeneity and agency in the contemporary food regime in Switzerland: among the food from nowhere, somewhere, and here sub-regimes. Rev Agric Food Environ Stud. 2024:207. doi: 10.1007/s41130-024-00207-y

Stotten, R., Bui, S., Pugliese, P., Schermer, M., and Lamine, C. (2017). Organic values-based supply chains as a tool for territorial development: a comparative analysis of three European organic regions. Int. J. Sociol. Agric. Food 24, 135–154.

Stotten, R., and Froning, P. (2023). Territorial rural development strategies based on organic agriculture: the example of Valposchiavo, Switzerland. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7:993. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2023.1182993

Svendsen, G. L., and Svendsen, G. T. (2000). Measuring social capital: the Danish co-operative dairy movement. Sociol. Rural. 40, 72–86. doi: 10.1111/1467-9523.00132

Tilzey, M. (2017). Reintegrating economy, society, and environment for cooperative futures: Polanyi, Marx, and food sovereignty. J. Rural Stud. 53, 317–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.12.004

Tilzey, M. (2018). Political Ecology, Food Regimes, and Food Sovereignty: Crisis, Resistance, Resilience. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tilzey, M. (2019). Food regimes, capital, state, and class: Friedmann and McMichael revisited. Sociol. Rural. 59, 230–254. doi: 10.1111/soru.12237

Tilzey, M., and Potter, C. (2016). Productivism versus Post-Productivism? Modes of Agri-Environmental Governance in Post-Fordist Agricultural Transitions, in Sustainable Rural Systems. Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Communities. Eds G. Robinson (Routledge e-book). 41–63.

Torrado, M. (2016). Food regime analysis in a post-neoliberal era: Argentina and the expansion of transgenic soybeans. J. Agrar. Change 16, 693–701. doi: 10.1111/joac.12158

Van Der Ploeg, P. (2020). From biomedical to politico-economic crisis: the food system in times of Covid-19. J. Peasant Stud. 47, 944–972. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2020.1794843

Voigt, C., Laura, H., Christina, P., and Pichler, M. (2024). Meat politics. Analysing actors, strategies and power relations governing the meat regime in Austria. Geoforum,

Woolcock, M. (1998). Social capital and economic development: toward a theoretical synthesis and policy framework. Theor Soc 27, 151–208. doi: 10.1023/A:1006884930135

Woolcock, M. (2001). The place of social Capital in Understanding Social and Economic out-Comes. Can. J. Policy Res. 2, 1–17.

Keywords: food regime theory, alternative food networks, transformation, critical state theory, social capital, territoriality

Citation: Plank C, Stotten R and Hafner R (2024) Values-based modes of production and consumption: analyzing how food alternatives transform the current food regime. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8:1266145. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2024.1266145

Edited by:

Andreas Exner, University of Graz, AustriaReviewed by:

Mark Tilzey, Coventry University, United KingdomErnst Langthaler, Johannes Kepler University of Linz, Austria

Copyright © 2024 Plank, Stotten and Hafner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Christina Plank, Y2hyaXN0aW5hLnBsYW5rQGJva3UuYWMuYXQ=

Christina Plank

Christina Plank Rike Stotten

Rike Stotten Robert Hafner

Robert Hafner