- College of Economics and Management, Northeast Agricultural University, Harbin, China

Introduction: It is widely known that rural labor mobility is of the utmost importance for the livelihoods of families in rural areas of developing countries. While it increases the income and overall labor productivity of rural households, it also creates many inevitable rural recessions. Existing studies have different views on whether increasing income is the only reason for rural labor mobility.

Methods: This paper discusses the influencing factors of rural labor mobility and investigates research on the causes of rural labor mobility. To do so, the study analyzes micro-survey data of 47 villages in 13 cities in Heilongjiang province, China, from 2014 to 2019. Considering the basic situation of rural families and labor mobility, the actual demand for rural laborers in Heilongjiang province is also analyzed.

Results: The research results show that increasing income is not the only reason for the flow of rural labor, and that rural labor mobility requires more than just rising incomes.

Discussion: This study's main contribution is identifying that increased income does have a positive and significant impact on rural labor mobility, but seeking job opportunities, pursuing better-quality education for children, and developing prospects are significant factors in the current rural labor mobility.

1. Introduction

It has been widely believed that rural labor mobility has been the major primary driver that has lifted both rural households' income and overall labor productivity (Cai, 2018; Wang and Benjamin, 2019). Since the second half of the twentieth century, countries like the US, Japan, Indonesia, Brazil, India, and China have either experienced or are experiencing a large amount of internal labor mobility (Dustmann and Preston, 2019; Masaki and Mayo, 2019; Marta et al., 2020). In 2016, 768 million people worldwide were internally mobile (United Nations, 2016). China has a unique institutional background that also demarcates its well-defined periods of rural labor mobility. Since the economic reform and opening up (1978), China's economic development level has continuously improved, the industrial structure has been continuously optimized, and the policies restricting labor mobility have been gradually lifted. A notable phenomenon facing China is of rural laborers' -most of whom are young and fit- mobility across sectors and regions, engaged in migrational off-farm employment (Liu and Li, 2017). According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China, the number of peasant laborers who were employed outside townships was 171.72 million in 2021, an increase of 1.4% over the previous year. The urbanization rate has risen to 64.72% in China as of the end of 2021.

According to the theory of labor mobility, due to the heterogeneity of agricultural labor, its mobility is not as fast as that of other production factors such as capital and land, and the direction of its flow is income-oriented, only flowing to places with high wages (Docquier et al., 2019). There is still a significant urban-rural dual structure in China. In addition to subjective factors such as family factors and personal factors, the most objective factor affecting labor mobility is the hukou system (Pizzi and Hu, 2022; Zhou and Hui, 2022). Even though the hukou system has undergone drastic changes in the past several decades, rural migrants are significantly more deterred by hukou restrictions than urban migrants (Colas and Ge, 2019). Migrant laborers without local hukou do have the right to access local public facilities, but their accessibilities are considerably limited; for example they do not have access to subsidized public housing, public education, public medical insurance, and government welfare payments (Müller, 2016; Sun, 2021). China still has a dual economy, as first described by Lewis (Gollin, 2014; Chen et al., 2018), and has an issue of unbalanced development between urban and rural areas, which other developing countries encountered during urbanization (Yaya et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021). Not only does the rural-urban income gap remain, but so too do large significant disparities in consumption, employment rate, productivity, infrastructure, and social services between rural and urban areas (Guo et al., 2020; Luo et al., 2022). These factors combined initiated the increase in labor mobility between rural and urban (Chen and Lin, 2013; Wang et al., 2019).

This paper uses household survey data from 47 villages in Heilongjiang province, China from 2014 to 2019, a theoretical framework based on the new economics of labor migration, the Lewis-Fei-Ranis model, and the push-pull theory to examine the influencing factors of rural labor mobility and investigate research on the causes of rural labor mobility. This study makes two contributions: one enriches the theoretical framework of rural labor mobility and provides Chinese samples and empirical supplements for the Lewis-Fei-Ranis model and push-pull theory. The other introduces summer precipitation as an instrumental variable to alleviate the endogeneity problems. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The second section introduces the theoretical framework, while the third section presents the data and methods used in this study in greater detail. Finally, the fourth presents the descriptive and empirical analysis. The fifth section discusses the results, and the final section provides a conclusion with policy implications.

2. The theoretical framework and hypotheses

2.1. The theory framework of rural labor mobility

Three aspects that affect rural labor mobility's decision-making are individual attributes, family attributes, and social attributes (Fan et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2020). The variables of gender, age, and education level of the labor force directly affect rural labor mobility. Family attributes mainly include family income, family composition, and cultivated land area (Liao and Yip, 2018; Ma et al., 2019). The level of agricultural mechanization and the distance between the residential village and the county seat also indirectly affect whether the laborers go out to work (Chen et al., 2018; Xiao and Zhao, 2018). In addition, the timeline proposed by relevant support policies also provides strong support for the framework of this paper. The Chinese government implemented Targeted Poverty Alleviation (TFA) in 2013 to ensure that all poor counties and regions will be out of poverty by 2020 (Zhou et al., 2017; Guo et al., 2020). In 2013 and 2014, the central government also emphasized accelerating the promotion of “rural land ownership confirmation”, promoting the transfer of arable land, and protecting the rights and interests of land transferors (Han, 2019; Zhou et al., 2020). The “Compulsory School Merger Plan”, which was implemented in 2001 and ended in 2012, merged small rural schools into fewer but larger (theoretically better funded) institutions. It requires rural minors of the appropriate age to go to different towns, leading to the phenomenon of “accompanying education” (Chow et al., 2019; Kihwele et al., 2019). Based on these influencing factors, in addition to the increase in income, we have also identified two possible reasons for rural labor mobility.

There is substantial evidence that access to education is an important essential factor affecting rural labor mobility (Xia and Lu, 2015). With the gradual opening of urban and rural barriers, pursuing better-quality education for children could be the reason for rural labor mobility. On the one hand, young or highly educated rural laborers tend to move to cities for better prospects (Melzer, 2013; Burger et al., 2020). On the other hand, the quality of rural-urban education varies greatly within developing countries (Lagakos, 2020). Parent laborers struggle between leaving their children behind in their rural homes and pursuing better-quality education in urban areas (Zhang, 2017; Emran et al., 2019). The Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China stated that, by 2020, the number of migrant children in compulsory education reached 14.297 million in China, an increase of 0.63 million over 2015. Empirical studies on countries around the world show that even in developed countries with small regional gaps, this mechanism of “mobility for education” exists objectively (Sá, 2015; Liu and Xing, 2016), and the flow direction of migrant laborers and their migrant children presents obvious directional characteristics (Xiong, 2015; Li et al., 2018).

Over the 40 years since reform and opening up, China's rural land system has undergone a drastic transition (Liu, 2018; Zhou et al., 2020): the establishment of the “three-rights separation” (i.e., ownership right, management right, and contract right) system for rural land lay an institutional foundation for promoting the rational allocation of rural resource elements, guiding the circulation of land management rights (Han, 2019; Dong et al., 2021). Some studies have found support for the view that agricultural mechanization and farmland transfer have contributed to rural-urban mobility (Kuang et al., 2021). In recent years, with the continuous improvement of the level of agricultural mechanization and the large-scale management of agricultural land, agriculture labor productivity has increased; as the Ranis-Fei model described (Ranis and Fei, 1961), the demand for rural labor force in agricultural production was significantly reduced (Cai et al., 2013; Xie and Lu, 2017; Gong et al., 2019), promoting the rural surplus laborers to seek job opportunities in cities (Lu et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2021).

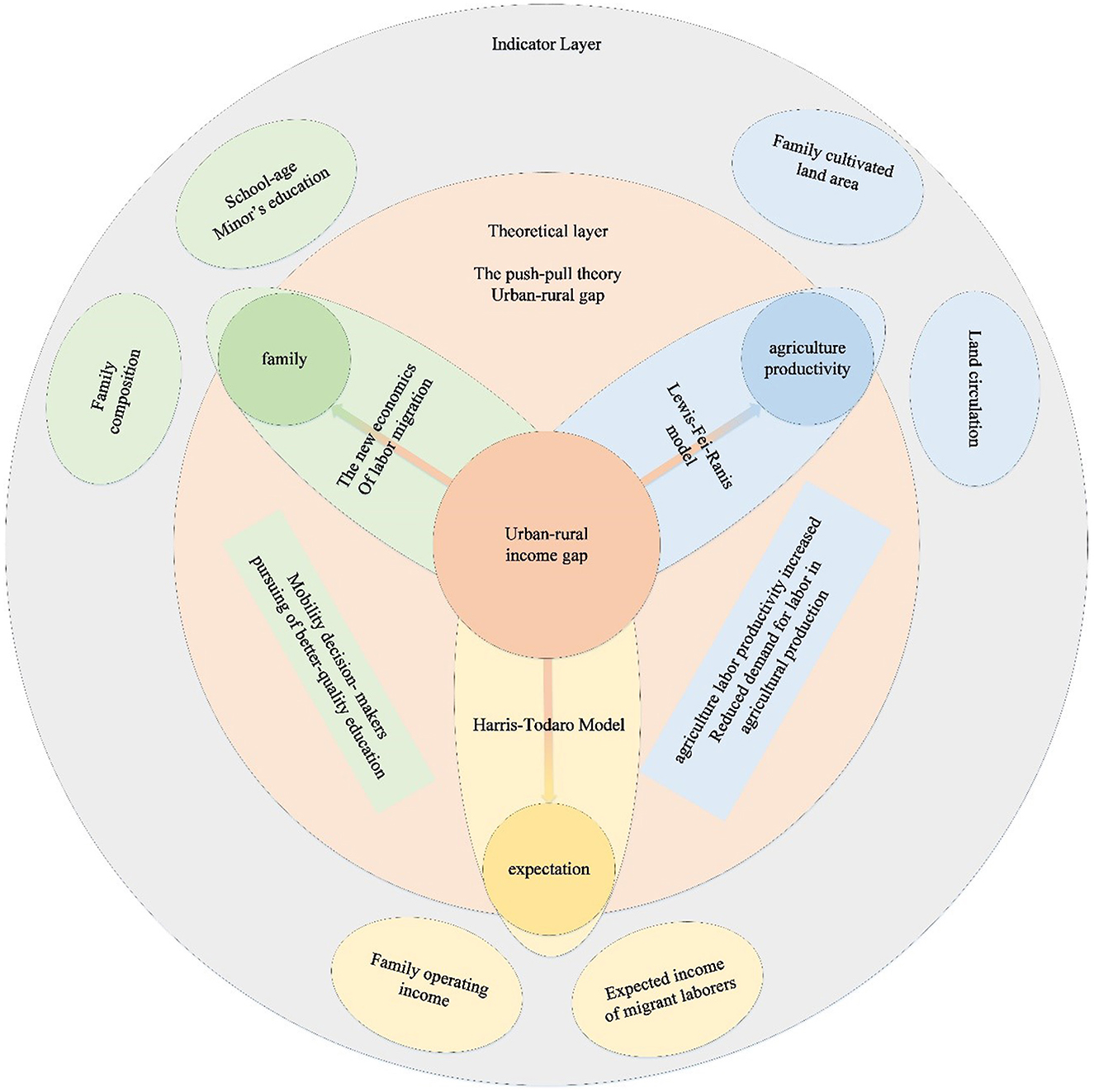

Rural labor mobility has complex motivations. There is not only the pull of the urban-rural wage gap and the push of insufficient rural resource endowments, which early development economists proposed (Lewis, 1954; Lee, 1966), but also the role of institutional reform dividends resulting from the gradual opening of urban and rural barriers (Zhang and Tian, 2018; Zhang et al., 2019). Laborers could leave to pursue increased income or better education for future generations, or be seeking labor opportunities in cities due to increased labor productivity in rural areas, reflecting the following contradictions, including the contradiction between better life needs for rural people and unbalanced urban-rural development (Lagakos, 2020; Guliyeva et al., 2021), the contradiction between rapid urbanization and inevitable rural decline (Li et al., 2018; Feng et al., 2019), and the contradiction between citizenization of rural labor and urban and rural barriers (Boffy-Ramirez and Moon, 2018; Colas and Ge, 2019). Therefore, it can still be asked what is the reason for the rural labor mobility–is it just for the increase of income–and what is the actual need for rural labor? Investigating these uncertainties is related to transforming the mode of rural labor development and improving urban-rural integration. Correct prediction of future rural labor mobility trends also optimizes the path of sustainable and stable growth of rural living standards. Based on the above analysis, the theoretical framework of this paper is based on the push-pull theory, formed by the new labor migration theory, the Lewis-Fei-Ranis model, and the Harris-Todaro model, combined with relevant literature research results. The theoretical framework of rural labor mobility in this paper is shown in Figure 1.

2.2. Hypotheses

In the real world, there may be many factors affecting rural labor mobility. This study is guided by our literature review and the survey of rural areas in Heilongjiang province, China. We mainly consider six factors that could affect the decision on rural labor mobility. The hypotheses in this paper are as follows:

Hypothesis 1: The higher the expected income of migrant laborers for the next year, the more likely to the laborer will be to make mobility decisions.

Hypothesis 2: The larger the area of family land inflow, the less likely to the laborer will be to make mobility decisions.

3. Data and methods

3.1. Data

The data used in this study were collected in the “Household Survey on Rural Economic and Social Conditions in Heilongjiang Province” for our study. It was continuous field surveys in 47 villages in 13 cities, including Harbin, Qiqihar, and Jiamusi in Heilongjiang Province, China. The survey collected information on the basic fundamental status of rural families, family labor status, and labor mobility. After extracting the samples with missing values in the main variables, a total of 15,125 samples remained.

The survey area was randomly selected according to the standards of land circulation, cultivated land area, and grain output, with the core along the “Sui-Man” line and “Two Great Plains'. Xiaoxing'an Mountains and the four resource-based cities each selected a typical agricultural county, implemented PPS three-stage sampling (township-village-household), and conducted a typical survey of the entire village. The sample cities were selected to cover six accumulative temperature zones, including a variety of topography and crop planting areas, the population was densely distributed, and most of the surveyed areas were large counties and dairy industry areas transferred from pigs. Specifically, the survey and research are distributed across one sub-provincial city, 11 prefecture-level cities, and one district in Heilongjiang Province, China. This covers 47 sample counties (cities), including plains, hills, mountains, and other topography; covering agricultural areas, forest areas, mining areas, and areas where corn, rice, soybeans, and other food crops are planted; and it includes both densely populated areas and relatively sparsely populated areas. The random sampling method is used to select the survey area and sample cities in this paper to ensure the samples are representative, which can minimize sample selection bias.

3.2. Variables

3.2.1. Rural labor mobility

In this paper, the dependent variable is the behavior of rural labor mobility, that is, whether rural laborers go out to work. 1 means that rural laborers go out for work and 0 means that rural laborers do not go out to work. The survey found that the labor force goes out to work in two ways: “going out to work and returning to the village to do farming when farming is busy” and “going out to work without participating in farming”. Considering that the regression analysis results of part-time labor have large significant errors, this paper only discusses “going out to work and not participating in farming”, so that the regression results are realistic.

3.2.2. Expected income of migrant laborers

Todaro's “expected income” theory believes that the difference in expected income between urban and rural areas will affect mobility decisions (Harris and Todaro, 1970). This paper uses the average income of migrant laborers in the village in the previous year as the expected income of migrant laborers. For laborers who have gone out to work in the previous year, their labor income will affect their decision-making in the next year. Laborers who have not yet gone out are referred to as migrant laborers in the same village. The labor income of the labor force forms the expectation of the income of migrant laborers.

3.2.3. Control variables

Based on the theoretical framework, control variables affecting rural labor mobility were selected from three perspectives in this paper. For individual attributes, the variables of gender, age, and education level of the labor force directly affect rural labor mobility. For family attributes, family operating income mainly refers to family income from farming and raising, excluding the wage income of migrant laborers. External factors include family composition, cultivated land area, and land circulation. For community attributes, the level of agricultural mechanization and the distance between the residential village and the county seat also indirectly affect whether the labor force goes out for work.

Many documents mention school-age minors' education, but this paper does not include it in the model. The research team conducted a remarkable collection of this issue and found that with the mobilization of basic education and the adjustment and withdrawal of primary and secondary schools in rural areas, the phenomenon of “accompaniment education” has emerged (He and Tian, 2018), which is usually divided into mother-accompaniment and inter-generational accompaniment Considering Heilongjiang's simple crop management methods and high agricultural mechanization level, the accompanying will choose to return to the village to help during busy farming periods. Accompanying parents are not separated from agricultural labor, therefore they do not belong to the scope of labor mobility in this paper. Therefore, the empirical part excludes this indicator.

Land is the main source of income for non-migrant farmers, providing them with the most basic employment opportunities and livelihood security. Compared with small farmers, large-scale farmers have greater livelihood capital. However, the increase in planting scale not only brings economies of scale to farmers, but also occupies the time that farmers may spend on working outside. Therefore, this article selects land inflow as the control variable that affects the flow of rural labor, mainly using the actual amount of land inflow by farmers to measure.

3.2.4. Instrumental variables

There may be reverse causation between family operating income and working outside, leading to endogeneity. The rural labor force chooses whether to go out to work according to the actual living conditions of the year, and the situation of going out to work will also affect their family income. Simultaneously, multiple collinearities between family operating income and family-cultivated land areas are also urgent problems. Therefore, this paper refers to the practices of Hu and Hong (2019) and Li et al. (2019), and others, and selects sample data to investigate the summer rainfall in each county in the previous year as an instrumental variable for family operating income.

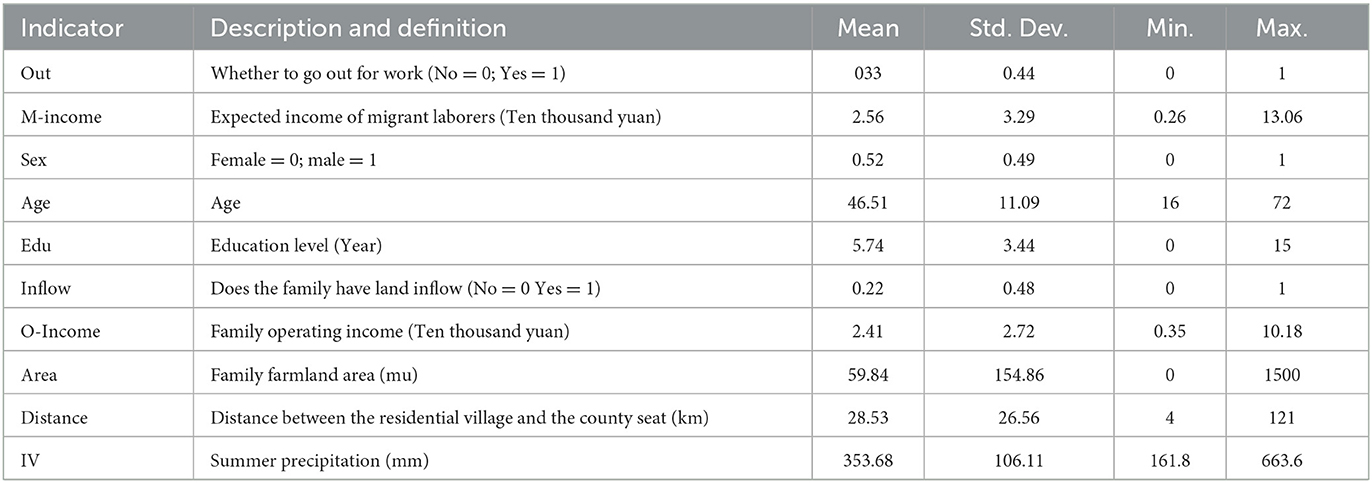

The selection of instrumental variables meets the requirements of correlation and exogeneity homogeneity. On the one hand, the instrumental variable summer precipitation is strongly correlated with the core explanatory variable family operating income. Rain-fed agriculture is one of the most prominent characteristics of agricultural production in Heilongjiang. The precipitation during crop growth and development will affect production costs and yields (Lobell et al., 2011; Acharya, 2018). The main food crops in Heilongjiang Province are rice, corn, and soybeans, all of which are one-season crops. Summer precipitation plays a decisive role in their growth, which determines the harvest of food crops. Therefore, summer precipitation directly affects farmers' family operating income that year, which affects the labor force engaged in agricultural operations in the second year. On the other hand, the summer precipitation is not related to the error term of the model. As a natural factor, summer precipitation has robust exogeneity and does not directly relate to whether laborers go out for work. Definitions are given in Table 1.

3.3. Model

Whether the labor force goes out to work is a binary variable. The linear regression model usually assumes that the dependent variable is continuous and is not suitable for solving such problems. Therefore, the binary logistic regression model is used to obtain the regression coefficient of each independent variable to explain the probability of rural labor mobility. The basic idea of the model is as follows:

Equation (1) can be written as:

To make the above model more elastic, the probability Πiis assumed to be influenced by a set of variables xi, and the relationship between the two is usually set as a linear function:

Where xi represents the explanatory variable and β represents the coefficient vector. This model is usually called the linear probability model, and it can be estimated by the ordinary least square method, but there are still defects. The probability value should be between 0 and 1, and the linear combination term on the right side of the equation can take any value. If the model is not strictly constrained, it is difficult to ensure the reasonable predicted value of the model.

Therefore, probability Πi should be transformed to eliminate the constraint on its range. First, probability Πi should define the odds ratio:

The ratio of the probability that yi = 1 to the probability that yi = 0 can be arbitrarily non-negative, thus eliminating the upper bound constraint.

Then, take the logarithm to compute logit:

The lower bound constraint can be eliminated.

After completing the above changes, the Logistic regression model is defined, and the logit variation of probability Πi is assumed to follow a linear model as follows:

Since the Logit transformation is one-to-one, we can obtain the probability value by taking the inverse logarithm and reverse logit, which can be solved by Equation (6):

The explained variable is further expressed as:

Where εi is the random interference term, which has two possible values:

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive analysis of the migrant labor force in Heilongjiang province

In the 2019 survey, a total of 1896 households were sampled and included in the household survey. There were 939 migrant laborers in the sampled households, accounting for 30.02% of the total labor force. This is an increase of 11.52% compared to 2014. 16% of the sampled households have labored and gone out for work, which is 3.51% higher than in 2014.

In this survey, the research team interviewed the main prominent leaders of the sampled village on the “basic situation of our village laborers going out for work”, and found that the village leaders have some understanding of the overall situation of the migrant laborers in the village, but they do not know the specific number of migrant laborers. This is because the definition of migrant laborers is vague, the village committee does not pay enough attention to migrant laborers in the village, and there is no statistical information on migrant laborers.

4.1.1. Age distribution of migrant labor

The ages of migrant laborers in the 47 sample villages is 18–64 years old; the majority are over 60 years old, and a few of them are younger than 20 years old. On the one hand, the problem of pensions for rural residents is prominent, and they still need to take odd jobs to subsidize their lives at the age of 60. On the other hand, it may be that some young people go to school, reducing the number of young laborers who go out to work. For example, in a survey in A Village, a villager surnamed Wang said, “When I am old, my children have a hard time. I don't want to trouble them all the time. I can do odd jobs for a small amount of money, but it's not easy to find odd jobs as I'm old”. In other villages, there are many similar answers, reflecting that the current rural residents' pension model is still imperfect.

4.1.2. Educational distribution of migrant labor

During the survey, the research team found that the majority of the migrant laborers have a junior high school education or above. However, 22% of the migrant labor force have a primary school degree or below, and the overall academic qualification is low. This is not only due to the achievements of the nation's compulsory education but also because of the special historical background. Residents in the village have certain requirements for their children's academic qualifications, but many parents fall behind this.

4.1.3. Income distribution of migrant labor

The average annual income of migrant laborers in the 47 surveyed villages is about 26,000 yuan, which is relatively high. However, the income gap is large, with more earning millions of yuan a year, and fewer earning only a few thousand yuan a year. When the research team interviewed about the “time for migrant laborers to go out to work”, we found that there are big differences in the same village, as well as different villages. For example, in B Village, a villager surnamed Chen said “Heilongjiang is cold in winter. My children are working on construction sites in nearby towns. They can't work for a few months a year and their income is unstable.” A villager surnamed Liu in C Village said, “The child works in a Shanghai electronics factory. It is relatively stable, with a monthly income of more than 3,000, which is enough for him.” We found that work location, type of work, and education level of migrant laborers have a significant impact on working hours. The working hours in this county and city are generally shorter, and the working hours outside the province are longer. The working hours are longer when the work is stable, and the lost time when the work is unstable is generally shorter.

4.1.4. Left-behind household members' situation

In this survey, the research team found that in some families both parents go out to work, while in some one parent stays home. In C Village, one woman named Wang said, “There are more children's parents in the village who go out to work. Only the children and grandparents are left behind at home. They come back several times a year, far away is once a year which is not easy to go back and forth.” In D Village, we found that the phenomenon of “left-behind children” was widespread, but the situation in different villages is quite different. The E village director Liu said that “our village does have more left-behind children, but parents can't make money unless they go out to work, it's very contradictory” We believe that the left-behind situation of families in the surveyed village is relatively serious, and the proportion of parents who go out to work is too large. The care mechanism for left-behind people needs to be improved urgently.

Through regression analysis of the ratio of children left behind, the ratio of spouses left behind, the ratio of both couples going out, the ratio of elderly left behind, and the labor mobility index, the results show that left-behind children hinder labor mobility and shorten the mobility radius, while the left-behind spouse and the elderly do not affect the mobility. There are three main reasons for the above results: First, due to the children's schooling and other reasons, both spouses generally leave one person to care for their children. Even if they go out to work, they will choose a closer working place. Second, the elderly population generally has more than two children in rural areas at this stage, and the burden of support is relatively small. Moreover, the survey found that many rural households have only two elderly people, and there is no need for young and middle-aged laborers in the family to help in agricultural production or take care of daily life. Third, although many people are old in rural areas, due to their limited income sources, they have to continue to engage in agricultural production or go out to do odd jobs to earn a living.

4.2. The total effect of labor attributes on rural labor mobility

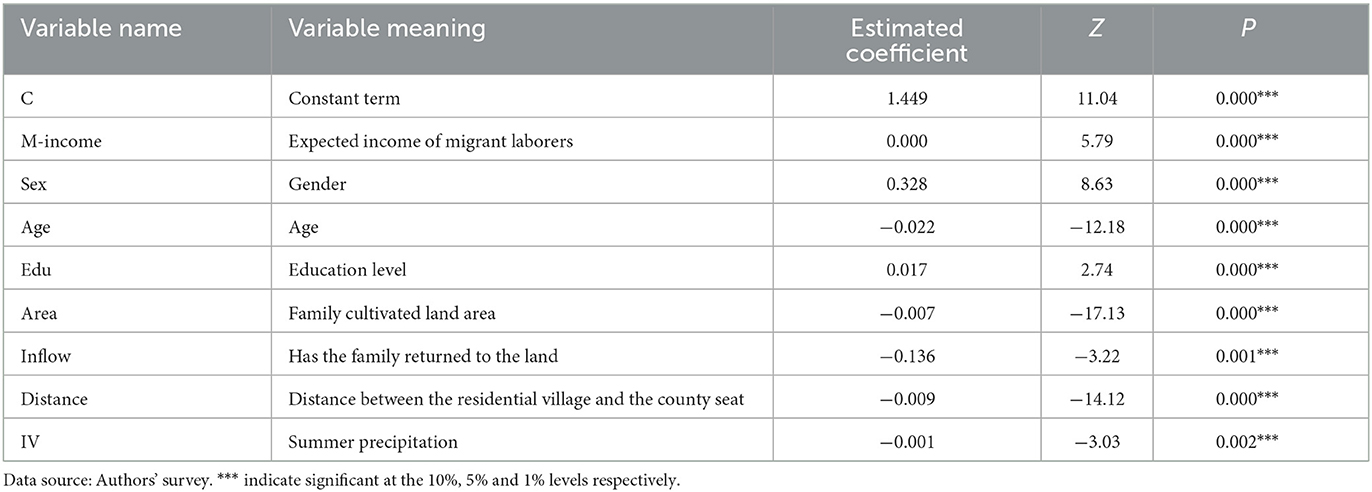

Based on the above descriptive analysis, we estimate the effect of individual and family attributes on rural labor mobility. Based on the above descriptive analysis, we then estimate the effect of individual attributes and family attributes on rural labor mobility. The influencing factors and their correlation coefficients are shown in Table 2.

The regression results show that the expected income of migrant laborers positively affects rural labor mobility, which is significant at the 1% statistical level. The variable of household operating income level is negatively correlated with labor mobility, indicating that the expected income of migrant laborers will affect the decision-making of going out to work. The result is consistent with hypothesis H1. When the income of migrant workers is lower or slightly higher than the income from agricultural production, migrant workers cannot meet the basic needs of farmers for income sources. Farmers will continue to engage in agricultural production and only work as workers. When income and agricultural income form a certain difference, they will flow outward.

The impact of migrant labor's education level is significant. This is firstly because the education level affects laborers' income when they go out to work. The rural labor force transfers from the agricultural industry to the non-agricultural industry because there is a gap between urban and rural income expectations. According to the education cost-benefit analysis model results, the higher the education level, the greater the opportunity cost and direct education cost, and the expected education income will also increase. The second contributing factor is the space for migrant laborers to go out for employment and the stability of their work. The higher the education level of laborers, and the higher their cultural literacy and learning ability, the faster they can adapt to the job. At the same time, there is a general education threshold in the recruitment of big cities, so many laborers with low education can only choose to work in the nearby towns, and their employment scope is narrow.

The area of household cultivated land is negatively correlated to rural labor mobility (row 6, column 3), and the situation of land inflow is negatively correlated to rural labor mobility (row 7, column 3), both of which are significant at the 1% statistical level. This indicates that the larger the area of family-cultivated land, the lower the possibility of labor mobility. This result is consistent with hypothesis H2. The land inflow will help promote large-scale land management and release rural labor. With the acceleration of the cultivation process of new agricultural business entities, the number of new agricultural business entities such as large plantation growers and family farms in Heilongjiang Province has increased rapidly. In the meantime, their development and the rapid development of cooperatives and agricultural-related enterprises have enabled the centralized production of fragmented land in rural areas. By leasing land to cooperatives and other methods, a large number of rural laborers are released. Not only can they collect a certain amount of rent, but the released rural laborers can also go to cities to work and obtain an income.

4.3. Robustness test

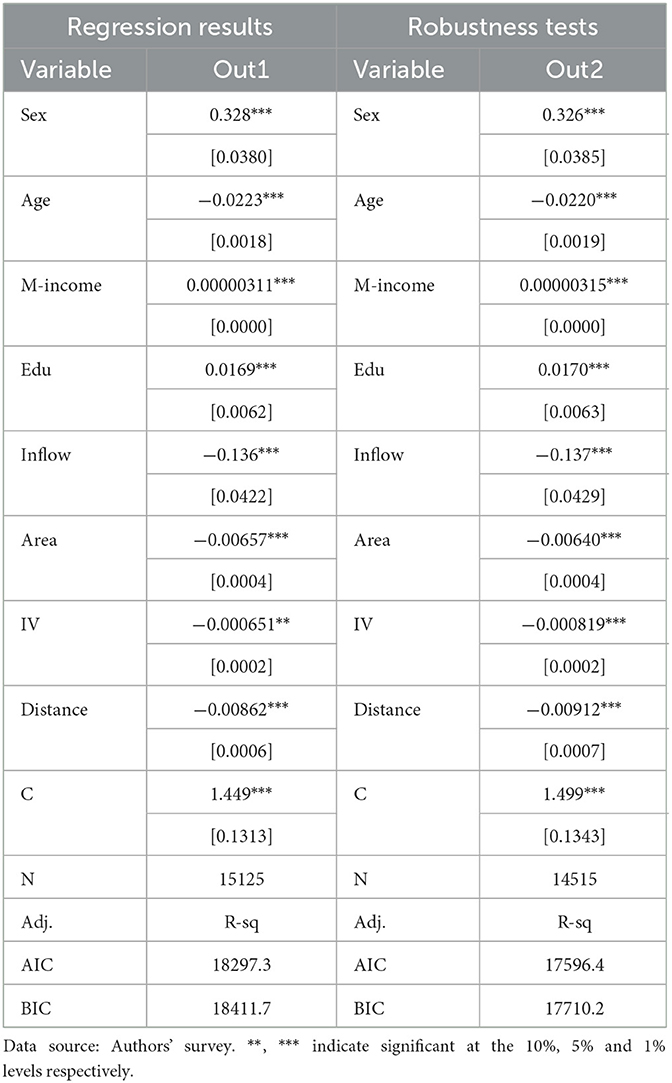

To ensure the reliability of the results, this paper rediscusses the robustness of the empirical results by changing the sample size. Among the 47 sample counties in Heilongjiang Province, the data of Fuyuan County and Tahe County are excluded, which are located in the fifth accumulated temperature zone (1900–2100°C) and the sixth accumulated temperature zone (<1900°C) respectively. After doing so, the proportion of agricultural business income in household income is lower, while the proportion of labor income has increased. To ensure that the empirical analysis conclusions are not affected by specific regions, this paper will exclude the samples from these two counties and then regress them again. The results presented in Table 3 show that the signs and significance of the main explanatory variables do not change substantially, indicating that the results of this paper have a certain robustness.

5. Discussion and implications

5.1. Discussion

The descriptive analysis results and empirical results indicate that increasing income is not the only reason for rural labor mobility. There are few employment opportunities in rural areas, unequal access to education for school-age minors, and the development prospects vary between urban and rural areas.

Many countries, especially China, have or are experiencing a large amount of internal labor mobility, but little attention has been paid to the causes of rural labor mobility. This study estimated the influencing factors of rural labor mobility and investigated research on the causes of rural labor mobility using data that tracked the basic fundamental status of rural families, family labor status, and labor mobility in 47 sample villages across 6 years in Heilongjiang province, China. This study's main contribution is identifying that increased income does have a positive and significant impact on rural labor mobility, but seeking job opportunities, pursuing better-quality education for children, and developing prospects are significant factors in the current rural labor mobility.

5.2. Implications

5.2.1. Theoretical implications

Our findings offer several theoretical implications. This paper focuses on the occurrence of rural labor mobility, and the deeper causes of it, while considering the impact of economic and non-economic factors on the decision for rural laborers to move to urban areas, which provides a new perspective to enrich the theoretical framework of rural labor mobility, providing Chinese samples and empirical supplements for Lewis' binary theory, the push-pull theory, and the Todaro model to a certain extent.

The Todaro model, which focuses on labor mobility in developing countries, emphasizes that the expected income gap between urban and rural areas has a decisive impact on labor mobility decisions (Harris and Todaro, 1970), and that the greater the expected income gap between urban and rural areas, the greater the likelihood that agricultural laborers will flow to urban areas. The new economics of labor migration, on the other hand, proposes that mobility decisions are usually motivated by household behavior (Stark and Bloom, 1985). Individual-level aspirations and household-level negotiations will jointly influence travel decisions (Bentolila et al., 2010; Donzuso, 2015; Levy et al., 2017). The Ranis-Fei model considers the emergence of an agricultural surplus due to an increase in agricultural productivity as a prerequisite for the inflow of agricultural labor into the industrial sector (Ranis and Fei, 1961).

5.2.2. Implications for policy and practices

The findings have implications for policy and practices. In the process of rural labor mobility, regardless of age, gender, or educational level, migrant labor is a high-quality labor force. This part of the labor force leaves the countryside and focuses on work and life in the cities. Although this has made important contributions to urban economic and social development, also it has also led to the lack of rural main-body construction. Women and the elderly have become the main leading agricultural producers, which has severely affected the governance structure in rural areas. Undoubtedly, the released rural laborers can also go to cities to work and obtain wage income. However, the fact that rural laborers go to urban areas to work is also due to the lack of job opportunities at the same level in the countryside, and this should not be overlooked.

The data points out that the labor force engaged in “accompaniment education” does not belong to the scope of labor mobility in this paper. However, the internal cause of the phenomenon cannot be ignored. It reflects the education gap between urban and rural areas. For the education of future generations, some family members need to take care of the children who go to school in cities and towns and have to sacrifice the income source of migrant laborers, thereby reducing the mobility of migrant workers' families to a certain extent. Even if both parents go out to work, they will choose a closer working place.

Therefore, in terms of policy implications, maybe we should divert attention to other aspects, and consider rural labor mobility in a more comprehensive way, rather than just focusing on the impact of increasing labor income. It is necessary to correctly understand the relationship between labor mobility and rural hollowing, and enable proper reasonable planning of labor demand in agricultural production.

5.3. Strengths and limitations

Existing literature on the study of environmental trends and economic factors of rural labor mobility has been relatively rich, and the study of the relationship between rural labor mobility and the urban-rural income gap is also relatively comprehensive; this paper conducts a further study of the causes of rural labor mobility. The main strengths are, at the research content level, the focus of rural labor mobility research is shifted from the occurrence of mobility to the key demand of rural labor, and the deeper causes of rural labor mobility are studied from the influencing factors of rural labor mobility. The survey data at the household level of Heilongjiang Province, which is typically representative of the level of rural labor mobility, are also used to further explore the basic laws and characteristics of rural labor mobility. At the methodological level, summer precipitation is introduced as an instrumental variable to solve the endogeneity problem between household operating income and whether rural laborers go out to work, and to solve the multiple covariance problem between household income and household cultivated land area.

It is necessary to acknowledge the limitations of this work. Firstly, because this study aims to investigate the causes of rural labor mobility in Heilongjiang Province, the control variables selected for the natural and economic attributes of Heilongjiang Province, such as land transfer and children's education, may not be suitable for the study of rural labor mobility in other regions of China, especially in the Yangtze River Delta region with little arable land area and economically developed provinces, which may weaken the contribution of this article.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the patients/participants was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

YH designed the research and methodology, compiled the literature, and put forward the policy recommendations. JC provided financial support and guidance during the revision phase. GW provided guidance throughout the entire research process. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China under Grant (22BJY084), the Heilongjiang Provincial Philosophy and Social Science planning project under Grant (19JYE273), and the Humanities and Social Science Fund of Ministry of Education of China under Grant (21YJA790053).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acharya, R. N. (2018). The effects of changing climate and market conditions on crop yield and acreage allocation in Nepal. Climate 6, 32. doi: 10.3390/cli6020032

Bentolila, S., Michelacci, C., and Suarez, J. (2010). Social contacts and occupational choice. Economica 77, 20–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0335.2008.00717.x

Boffy-Ramirez, E., and Moon, S. (2018). The role of China's household registration system in the urban-rural income differential. China Econ. J. 11, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/17538963.2018.1453103

Burger, M. J., Morrison, P. S., Hendriks, M., and Hoogerbrugge, M. M. (2020). “Urban-rural happiness differentials across the world,” in World Happiness Report 2020, 67–94.

Cai, F. (2018). The great exodus: how agricultural surplus laborers have been transferred and reallocated in China's reform period? China Agric. Econ. Rev. 10, 3–15. doi: 10.1108/CAER-10-2017-0178

Cai, F., Wang, M., and Du, Y. (2013). Understanding Changing Trends in Chinese Wages in China's New Role in the World Economy. London: Routledge, 89–108.

Chen, B. K., and Lin, Y. F. (2013). Development strategy, urbanization and the rural-urban income disparity in China. Social Sci. China 4, 81–102.

Chen, C., LeGates, R., Zhao, M., and Fang, C. (2018). The changing rural-urban divide in China's megacities. Cities 81, 81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2018.03.017

Chow, J. C.-C., Ren, C., Mathias, B., and Liu, J. (2019). InterBoxes: A social innovation in education in rural China. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 101, 217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.04.008

Colas, M., and Ge, S. (2019). Transformations in China's internal labor migration and hukou system. J. Lab. Res. 40, 296–331. doi: 10.1007/s12122-019-9283-5

Docquier, F., Kone, Z. L., Mattoo, A., and Ozden, C. (2019). Labor market effects of demographic shifts and migration in OECD countries. Eur. Res. Rev. 113, 297–324. doi: 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2018.11.007

Dong, Y., Wang, W., Li, S., and Zhang, L. (2021). The cumulative impact of parental migration on schooling of left-behind children in rural China. J. Rural Stud. 86, 527–541. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.07.007

Donzuso, N. N. (2015). ‘Equality of opportunities' in education for migrant children in China. Global Soc. Welfare 2, 9–13. doi: 10.1007/s40609-014-0012-y

Dustmann, C., and Preston, I. (2019). Free movement, open borders, and the global gains from labor mobility. Ann. Rev. Econ. 11, 783–808. doi: 10.1146/annurev-economics-080218-025843

Emran, M. S., Ferreira, F., Jiang, Y., and Sun, Y. (2019). Intergenerational educational mobility in rural economy: evidence from China and India. Microecon. Stu. Educ. Markets. 24, 904 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3393904

Fan, X., Gao, G., and Luo, Q. (2015). An analysis of migration space decision of rural surplus labors and its influence factors: a case study on the survey of rural households in Henan Province. Econ. Geography 35, 134–139.

Feng, W., Liu, Y., and Qu, L. (2019). Effect of land-centered urbanization on rural development: A regional analysis in China. Land Use Policy 87, 104072. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104072

Gollin, D. (2014). The Lewis model: a 60-year retrospective. J. Econ. Persp. 28, 71–88. doi: 10.1257/jep.28.3.71

Gong, T. C., Battese, G. E., and Villano, R. A. (2019). Family farms plus cooperatives in China: technical efficiency in crop production. J. Asian Econ. 64, 101129. doi: 10.1016/j.asieco.2019.07.002

Guliyeva, A. A., Averina, L. S., Grebennikov, O. V., and Shpakov, A. P. (2021). “Regional gap in human capital: determinants of education and urbanization,” in E3S Web of Conferences 301, 03004.

Guo, Y., Zhou, Y., and Liu, Y. (2020). The inequality of educational resources and its countermeasures for rural revitalization in southwest China. J. Mount. Sci. 17, 304–315. doi: 10.1007/s11629-019-5664-8

Han, C. (2019). The reform of China's rural land system. Issues Agric. Econ. 4–16. doi: 10.13246/j.cnki.iae.2019.01.001

Harris, J. R., and Todaro, M. P. (1970). Migration, unemployment and development: a two-sector analysis. The Am. Econ. Rev. 60, 126–142.

He, Y., and Tian, Y. (2018). An analysis of urban adaptation and urban orientation of rural schooling-accompanying migrant groups: an investigation in h county in Northeast China. J. Shanghai Univ. 35, 23–34.

Hu, X., and Hong, W. (2019). Which is the cause, labor migration or land rental? J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. 137, 145–169.

Kihwele, J., Taye, M., and Sang, G. (2019). Mitigating the rural-urban disparities in Chinese compulsory basic education. Int. J. Res. Stud. Educ. 8, 57–66. doi: 10.5861/ijrse.2019.4003

Kuang, Y., Yang, J., and Abate, M.-C. (2021). Farmland transfer and agricultural economic growth nexus in China: agricultural TFP intermediary effect perspective. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 14, 184–201 doi: 10.1108/CAER-05-2020-0076

Lagakos, D. (2020). Urban-rural gaps in the developing world: does internal migration offer opportunities? J. Econ. Persp. 34, 174–192. doi: 10.1257/jep.34.3.174

Levy, B. L., Mouw, T., and Perez, A. D. (2017). Why did people move during the Great Recession? The role of economics in migration decisions. J. Soc. Sci. 3, 100–125. doi: 10.7758/rsf.2017.3.3.05

Lewis, W. A. (1954). Economic development with unlimited supplies of labour. Manch. Sch. 22, 139–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9957.1954.tb00021.x

Li, W., Lin, H., and Jin, Z. (2019). Social capital availability: the case of farmers and herdsmen from inner Mongolia. Econ. Res. J. 54, 134–149.

Li, Y., Huang, H., and Song, C. (2021). The nexus between urbanization and rural development in China: Evidence from panel data analysis. Growth Change 14, 1–15.

Li, Y., Jia, L., Wu, W., Yan, J., and Liu, Y. (2018). Urbanization for rural sustainability–Rethinking China's urbanization strategy. Journal of Cleaner Production 178, 580–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.273

Liao, P.-J., and Yip, C. K. (2018). Economics of Rural–Urban Migration in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Economics and Finance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Liu, J., and Xing, C. (2016). Migrate for education: an unintended effect of school district combination in rural China. China Econ. Rev. 40, 192–206. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2016.07.003

Liu, S. (2018). The structure and changes of China's land system. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 11, 471–488. doi: 10.1108/CAER-05-2018-0102

Liu, Y., and Li, Y. (2017). Revitalize the world's countryside. Nature 548, 275–277. doi: 10.1038/548275a

Lobell, D., Schlenker, W., and Costa-Roberts, J. (2011). Climate trends and global crop production since 1980. Science 333, 616–620. doi: 10.1126/science.1204531

Lu, H., Xie, H., and Yao, G. (2019). Impact of land fragmentation on marginal productivity of agricultural labor and non-agricultural labor supply: a case study of Jiangsu, China. Habitat Int. 83, 65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2018.11.004

Luo, G., Zeng, S., and Baležentis, T. (2022). Multidimensional measurement and comparison of China's educational inequality. Soc. Indic. Res. 21, 1–18. doi: 10.1007/s11205-022-02921-w

Ma, L., Chen, M., Che, X., and Fang, F. (2019). Farmers' rural-to-urban migration, influencing factors and development framework: A case study of Sihe village of Gansu, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health 16, 877. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16050877

Marta, J., Fauzi, A., Juanda, B., and Rustiadi, E. (2020). Understanding migration motives and its impact on household welfare: evidence from rural–urban migration in Indonesia. Reg. Stu. Reg. Sci. 7, 118–132. doi: 10.1080/21681376.2020.1746194

Masaki, N., and Mayo, M. (2019). Japan's Employment System from a Historical Perspective: Formation, Expansion, and Contraction of Internal Labor Markets (Japanese). Beijing: Trade and Industry (RIETI).

Melzer, S. M. (2013). Reconsidering the effect of education on East–West migration in Germany. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 29, 210–228. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcr056

Müller, A. (2016). Hukou and health insurance coverage for migrant workers. J. Curr. Chin. Affairs 45, 53–82. doi: 10.1177/186810261604500203

Pizzi, E., and Hu, Y. (2022). Does Governmental Policy Shape Migration Decisions? The Case of China's Hukou System. Modern China. 48, 1050–1079. doi: 10.1177/00977004221087426

Sá, F. (2015). Immigration and house prices in the UK. The Econ. J. 125, 1393–1424. doi: 10.1111/ecoj.12158

Stark, O., and Bloom, D. E. (1985). The new economics of labor migration. The Am. Econ. Rev. 75, 173–178.

Sun, M. (2021). The potential causal effect of hukou on health among rural-to-urban migrants in China. J. Family Econ. Issues 42, 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10834-020-09698-5

Wang, S. X., and Benjamin, F. Y. (2019). Labor mobility barriers and rural-urban migration in transitional China. China Econ. Rev. 53, 211–224. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2018.09.006

Wang, X., Shao, S., and Li, L. (2019). Agricultural inputs, urbanization, and urban-rural income disparity: evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 55, 67–84. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2019.03.009

Wu, Y., Zhou, Y., and Liu, Y. (2020). Exploring the outflow of population from poor areas and its main influencing factors. Habitat Int. 99, 102161. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2020.102161

Xia, Y., and Lu, M. (2015). The three migrations of mengmu between cities: an empirical study on the impact of public services on labor flow. Manage. World 10, 78–90.

Xiao, W., and Zhao, G. (2018). Agricultural land and rural-urban migration in China: a new pattern. Land Use Policy 74, 142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.05.013

Xie, H., and Lu, H. (2017). Impact of land fragmentation and non-agricultural labor supply on circulation of agricultural land management rights. Land Use Policy 68, 355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.07.053

Xiong, Y. (2015). The broken ladder: why education provides no upward mobility for migrant children in China. The China Quart. 221, 161–184. doi: 10.1017/S0305741015000016

Yang, H., Huang, K., Deng, X., and Xu, D. (2021). Livelihood capital and land transfer of different types of farmers: evidence from panel data in Sichuan province, China. Land 10, 532. doi: 10.3390/land10050532

Yaya, S., Uthman, O. A., Okonofua, F., and Bishwajit, G. (2019). Decomposing the rural-urban gap in the factors of under-five mortality in sub-Saharan Africa? Evidence from 35 countries. BMC Public Health 19, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6940-9

Zhang, G., and Tian, Z. (2018). China's rural labor mobility in the 40 years of reform and opening-up: changes, contributions and prospects. Issues Agric. Econ. 7, 23–35.

Zhang, H. (2017). Opportunity or new poverty trap: Rural-urban education disparity and internal migration in China. China Econ. Rev. 44, 112–124. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2017.03.011

Zhang, K., Chen, C., Ding, J., and Zhang, Z. (2019). China's hukou system and city economic growth: from the aspect of rural–urban migration. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 12, 140–157. doi: 10.1108/CAER-03-2019-0057

Zhou, J., and Hui, E. C. M. (2022). The hukou system and selective internal migration in China. Papers Reg. Sci. 101, 461–482. doi: 10.1111/pirs.12651

Zhou, W., Zhao, F., Yang, F., and Li, L. (2017). Land transfer, reform of household registration system and urbanization in China: Theoretical and simulation test. Econ. Res. J. 52, 183–197.

Keywords: rural China, labor mobility, household survey data, urban-rural gap, poverty eradication

Citation: Hao Y, Chi J and Wang G (2023) Is increasing income the only reason for rural labor mobility?—A case study of Heilongjiang, China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7:1239281. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2023.1239281

Received: 18 June 2023; Accepted: 28 August 2023;

Published: 21 September 2023.

Edited by:

Sendhil R, Pondicherry University, IndiaReviewed by:

Irudaya Rajan Sebastian, International Institute of Migration and Development, IndiaAndrzej Klimczuk, Warsaw School of Economics, Poland

Copyright © 2023 Hao, Chi and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jia Chi, amlhLmNoaUBuZWF1LmVkdS5jbg==; Gangyi Wang, YXdneUBjYXUuZWR1LmNu

Yanzhi Hao

Yanzhi Hao Jia Chi*

Jia Chi*