- 1Centre for Climate Change and Social Transformations (CAST), School of Psychology, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom

- 2School of Applied Sciences, University of the West of England, Bristol, United Kingdom

- 3School of Geography and Planning, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom

Introduction: Failures of the current food system sit at the core of the multitude of crises by being the root framework for both consumption choices and food production. Low-income households are disproportionately affected by these failures, impacting their food security and access to healthy and sustainable foods. Community-supported agriculture (CSA) is a bottom-up response towards an agri-food system transformation by providing an alternative food system based on agroecologically grown food that is sold locally and rooted in social values. Alongside other food citizenship movements and alternative food networks (AFN), CSAs are driven by the vision to develop a democratic, socially and economically just, and environmentally sustainable food system. Yet, low-income households are underrepresented in the CSA community.

Method: Our paper presents findings from a co-produced intervention between the research team, four CSA farms based in Wales, United Kingdom and two food aid partners that sought to identify ways to improve the accessibility of CSA memberships for food-insecure households. Thirty-eight households received a weekly veg bag for a period of 2–4 months. We interviewed 16 household members at the project start and end of the harvest season. Building on the food well-being framework, we investigate impacts of a CSA membership on food-insecure households.

Results: We found that CSA membership holistically improves food well-being, through strengthening producer-consumer relationships, increasing availability of healthy foods, helping people to care for their own and their families well-being, and building place-based food capability and literacy.

Discussion: This paper supports wider narratives that call for systematically prioritizing interventions that promote overall food well-being, which can lead to sustainable and just food systems with positive outcomes for financially excluded, food insecure households in localized AFNs.

1. Introduction

What we eat and the way we produce our food greatly impacts our land, climate, biodiversity, health and well-being, and communities (Willett et al., 2019). The current food system is not only unsustainable but also increasingly inequitable, resulting in food insecurity for many people in the United Kingdom and globally. The failures of the current food system were further highlighted during the COVID-19 and the current cost-of-living crises that amplified the risk factors associated with food insecurity and an unhealthy diet, with its biggest negative impact on already vulnerable communities (Power et al., 2020; Sanderson Bellamy et al., 2021; Patrick and Pybus, 2022).

These layered crises not only exacerbate and replicate food and health inequalities, but simultaneously fuel scholarly and practitioners’ interest in Alternative Food Networks (AFN) as a response. AFNs have been for some time at the center of practice and discussion about how to make food systems more just and sustainable (Jarosz, 2008; Bos and Owen, 2016; Cerrada-Serra et al., 2018). Community gardens, farmers markets and Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) have been hailed for addressing key failures of industrialized food system by being rooted in ecological and social values (Mert-Cakal and Miele, 2022), and creating well-being benefits (Giraud et al., 2021). They have been criticized for their inaccessibility to low-income households (Vasquez et al., 2016) and potential to reproduce social inequalities (Guthman, 2011; Moragues-Faus and Marsden, 2017). This study addresses these gaps by focusing on how CSA memberships can be made more accessible to low-income and food-insecure households.

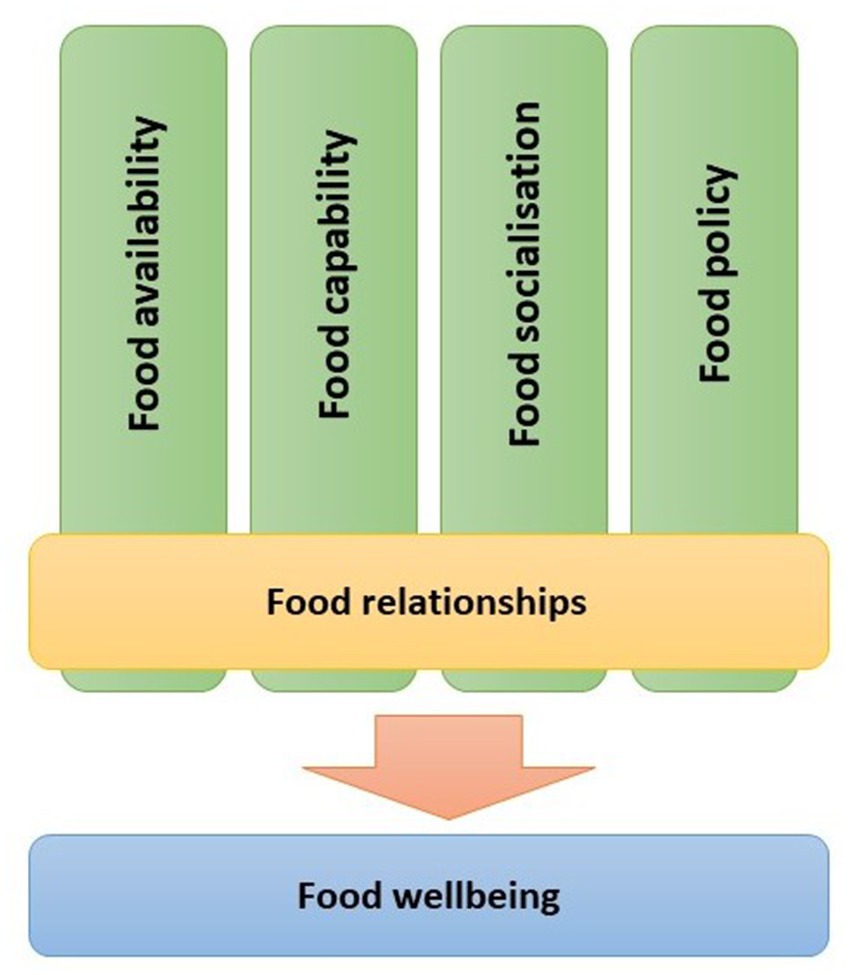

We contribute to these debates by presenting findings from a co-produced intervention between the research team, four CSA farms based in Wales, United Kingdom and two food aid partners. We aimed to identify barriers to CSA membership and participation, understand the impact of CSA membership on food-insecure households and explore means for CSAs to implement solidarity models to improve accessibility of healthy and sustainably-produced food. We explore the impact of CSA membership on food-insecure and low-income households across four dimensions influencing food-well-being, building on the food-well-being framework (Block et al., 2011; Voola et al., 2018). In addition to the four dimensions, namely (1) food availability, (2) food capability, (3) food socialization, and (4) food policy, we identified a cross-cutting theme we call food relationships. We argue that community-supported agriculture holistically improves food well-being by strengthening producer-consumer relationships, increasing physical availability of healthy foods, helping people to care for their and their families’ well-being and building place-based food capability and literacy.

The remainder of this section introduces the concept of CSA, highlights inequalities in the current food system and ties these in with concepts around food citizenship and food well-being, before introducing the methodology and analysis and discussion of the present study data in the context of food well-being and through the lens of the food well-being framework by Voola et al. (2018), which further enhances our understanding of food well-being.

1.1. Community supported agriculture as a response to a broken food system

The current food system is dominated by large-scale producers, food manufacturers, and retailers well equipped to maximize calorific content and longevity of food. However, the system fails to provide nutritious, sustainable food for all (Schmidt-Traub et al., 2019). Diet-related non-communicable diseases are largely driven by a food system that encourages cheap and energy dense food choices (Branca et al., 2019). The COVID-19 pandemic further highlighted many of the weaknesses of the current dominant food system and injustices and its detrimental effects on people’s health and well-being (Shanks et al., 2020). Moreover, current trends in global food systems prevent achieving climate change goals, hence rapid and ambitious actions are needed (Clark et al., 2020). Increasingly, there have been calls for a more sustainable and equitable food system, a narrative that has been underpinned by multiple discourses around what an equitable food system could look like (Juskaite and Haug, 2023). CSA is commonly seen as one of the key alternative food networks (AFNs) that challenge the conventional food system dominated by large-scale, industrialized agriculture and globalized supply chains.

Community-supported agriculture is a bottom-up response to address key failures of the current food system by providing an alternative food system based on agroecologically produced food that is grown for the community and rooted in social values (Mert-Cakal and Miele, 2022). It is a model of agriculture that connects consumers directly with local farmers. The main idea behind CSA is that individuals or households purchase a share of a farm’s produce in advance. This provides farmers with the necessary capital to grow their produce and ensures that consumers receive fresh, locally-grown produce throughout the season, often accompanied by community events and opportunities to contribute to the work on the CSA farms (Forbes and Harmon, 2008). They are commonly seen as an example of alternative food networks (Cerrada-Serra et al., 2018). Although the discussion about their emergence, definition and transformatory impact is ongoing, AFNs are usually underpinned by the following five principles: (a) transparent short supply chains, (b) organic or environment-friendly farming at smaller scale, (c) reconnecting producers and consumers through alternative routes to market, such as food co-operatives and farmers markets (Jarosz, 2008), (d) commitment to develop socially and economically just, and environmentally sustainable food systems (O’Kane, 2016), and (e) promoting citizen-consumer participation in shaping their food systems (Renting et al., 2012; Moragues-Faus and Marsden, 2017).

Community-supported agricultures play a pivotal role in food production and are a key actors in transforming the sector (Matzembacher and Meira, 2019). CSA is a unique model of agriculture that emphasizes direct relationships between farmers and consumers, shared risks and benefits, locally grown and seasonal produce, sustainable agricultural practices, and community involvement. The United Kingdom CSA Network Charter describes four principles by which to define CSAs: (1) agroecological production; (2) community investment and commitment in sharing risks, rewards and responsibilities of farming; (3) farm businesses that produce food, flowers, fibre or fuel; and (4) hyper local direct distribution of their own produce.

Alternative food networks in general have been critiqued for their potential to reproduce social inequalities (Guthman, 2011; Moragues-Faus and Marsden, 2017) or being prone to co-optation (Marsden and Sonnino, 2007; Pudup, 2008). However, we are more inclined to continue to look for ‘politics of possibility’ with Gibson-Graham (2006, p. xxxi) who observe that ‘future possibilities become viable by virtue of already being seen to exist’. This is especially important when it comes to creating democratic, just and sustainable food systems that need fertile soil to nurture seeds of such possibilities. CSA fertilizes the soil by centering care for people and the planet in their practices (Jarosz, 2011), as well as allowing producers and consumers to express care for diverse human and more-than-human others (Cox et al., 2013). Nevertheless, working in a neoliberal food regime that prioritizes unhealthy and unjust food by design (Guthman, 2011) makes it challenging to balance their environmental and social justice commitments (Bos and Owen, 2016). While highly motivated to contribute to their community, CSAs often lack the resources to systematically improve their reach to more diverse members of their community (e.g., low-income households; Galt et al., 2017). Therefore, access to their produce is often economically and culturally limited (Bos and Owen, 2016; Prost, 2019). This in turn contributes to inequalities in accessibility of sustainably-produced fruit and vegetables and other non-food benefits.

1.2. Underrepresentation of low-income households in CSAs

Community-supported agriculture members are demographically homogeneous with most members being affluent, highly educated, and white (Vasquez et al., 2016). Accessibility of CSA membership is multi-faceted, often correlated with household income. Research in the United States suggests that as well as income barriers, social, cultural and identity factors may constitute additional obstacles to membership that CSAs could address (Galt et al., 2017). CSA programs have been associated with positive impacts on food consumption and health benefits as well as an increased sense of belonging and community building. This means that large parts of the population are excluded from potential CSA membership benefits. Lower-income households and those affected by food insecurity would particularly benefit from these positive impacts. A recent study conducted with a poor community in the US found that a substituted CSA program improved diet behaviors, food security and overall health (Izumi et al., 2020). While there has been some research into potential benefits of CSA memberships for low-income households (e.g., Berkowitz et al., 2019; Izumi et al., 2020), these programs tend to be subsidized by charities or health initiatives.

The social benefits of local AFNs have been recognized elsewhere (Diekmann et al., 2020). As such, we argue that focusing on building relationships back into the food system and connecting households to food producers, as is achieved by the CSA model, better addresses food well-being, leading to corresponding changes in dietary behavior. Focusing on the community scale means that the relevant place-based approach is incorporated in how the community may choose to redress food insecurity and build solidarity models. By focusing systematically on how these interventions foster overall food well-being, rather than just accessibility to food or better nutrition, we can move towards more sustainable and just food systems that create positive outcomes for food-insecure households who are too often financially excluded from participating in localized AFNs.

Community-supported agriculture diets tend to adhere more closely to the recommendations of the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems (Willett et al., 2019; Mills et al., 2021; Sanderson Bellamy et al., 2023). There has been some criticism of the EAT-Lancet Commission diet for not meeting the need for micronutrients (Beal et al., 2023) and for not assessing the affordability of the recommended diet (Hirvonen et al., 2020). CSA diets tend to be more varied and of higher quality (Minaker et al., 2014), which is likely to provide more micronutrients. However, CSA diets tend to not be tailored to meet affordability and accessibility needs. Households that decide to join a CSA are usually motivated to make a change to their diet, most often because of either health or sustainability reasons (Sanderson Bellamy et al., 2021). This, together with their higher average income, raises practical questions for both CSA farmers and for policymakers about how to scale-out impact to a wider cross-section of society. However, with even the Eatwell diet (United Kingdom public health guide for healthy diet) being increasingly unaffordable for a growing percentage of the population, achieving sustainable and healthy diets for all will not be possible without significant policy shifts.

1.3. Food citizenship and food well-being

Accessibility to CSA memberships for low-income households is also relevant to debates on food citizenship and food well-being. In the wider context of the food democracy movement, a term coined in the 1990’s (Lang, 1998), food citizenship has emerged as a concept that rethinks consumers as active citizens who participate in shaping the food system (Renting et al., 2012). Through creating spaces for building up individual and collective agency to determine values in the food system, it aims to shift power relations to establish justice and fairness (Bornemann and Weiland, 2019). Food citizenship is often promoted through involvement in community-based food projects, which have been associated with improved well-being. For instance, a study by Lam et al. (2019) showed that exposure to school gardens increased youth well-being. More specifically, the school gardens were associated with relaxation, connectedness to growing food and the people involved, improved self-esteem, and other dimensions linked to well-being. Another study found a strong link between participation in local food projects with increased well-being (Bharucha et al., 2020). The authors identify well-being as a co-benefit of local food initiatives beyond the mental and physical benefits of growing food. Blake (2019) has identified similar food-plus benefits - new skills and increased individual and community resilience through relationship building, acquired by people participating in and running community food-security initiatives. These non-food co-benefits are a real asset in times of both a food and mental health crisis. Low-income households have been disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and cost-of-living crisis, with detrimental effects on people’s well-being (Power et al., 2020; Patrick and Pybus, 2022). Hence, CSAs have the potential to counter some of these effects by providing healthier food and mental health benefits. More broadly, the underrepresentation of low-income households in CSAs impedes aims to democratize and redistribute power imbalances within the food system (Juskaite and Haug, 2023).

Food well-being is a multidimensional concept that combines perspectives from food security, food sovereignty and individual and social well-being (Gartaula et al., 2017). In a broader sense, it can be defined as “a positive psychological, physical, emotional, and social relationship with food at both the individual and societal levels” (Block et al., 2011, p. 6). As such, food well-being is situated in the wider context of food availability and food (in)security and is a direct outcome experienced by individuals from food consumption and their relationship with the food (Jayashankar and Raju, 2020). Promoting a more holistic approach to food overcomes the shortcomings of any unidimensional understanding, for example food as only health (Block et al., 2011) or as secure production and supply (Gartaula et al., 2017). Voola et al. (2018) emphasized the importance of addressing not only nutritional needs but also factors such as food access, food safety, and the social and emotional aspects of eating when considering food well-being.

Food well-being has been associated with physical health, positive emotions, and more generally with life satisfaction (Ares et al., 2015). Increasingly, evidence has highlighted the important relationship between food and subjective well-being. Apaolaza et al. (2018) demonstrates that organic food consumption is linked to increased well-being, especially when individuals hold strong health beliefs. In the context of low-income consumers, food well-being has also been associated with social cohesion and networks as underpinning factors of perceived food availability (Jayashankar and Raju, 2020). As highlighted by Block et al. (2011) in their conceptualization of food well-being, a key component is food availability which tends to be compromised for low-income and food-insecure households, especially with regards to healthy and fresh foods. Common barriers to food availability include so called ‘food desserts’ (i.e., areas with limited availability of affordable, fresh produce), transport barriers, reliance on packaged and processed foods (e.g., due to limited storing options and due to being a source of cheap calories) and psychological distress caused by hunger (Bublitz et al., 2019).

Scholars to date have used food well-being to explore well-being as a perceived outcome (Jaeger et al., 2022) or to assess different factors and their configurations that contribute to or limit food well-being. The latter particularly resonates in scholarship investigating its relationship to food injustices such as community response to food insecurity in the United Kingdom (Parsons et al., 2021) and in the United States (Bublitz et al., 2019), food insecurity amongst farmers in Nepal (Gartaula et al., 2017) or gendered experiences of food insecurity in India (Voola et al., 2018).

Although there is not yet a consensus over the definition of food well-being (Jaeger et al., 2022), scholars have widely used Block et al.’s (2011) five dimensions of food well-being: food socialization, food availability, food literacy, food marketing and food policy. In their research of gendered experiences of food insecurity in India, Voola et al. (2018) developed the framework with a specific focus on food well-being in poverty, and paid attention to four dimensions: food availability (the production of food and its accessibility), food socialization (the socio-cultural influences and relevance of food, with a focus on family setting), food capability (conceptual, procedural and functional knowledge about food and nutrition), and food policy (from macro-level of agriculture, technology and welfare to micro-level of food safety and labelling). They enrich Block et al.’s (2011) framework with a feminist lens, shedding light on the role of families and especially women in shaping food well-being, and by developing the food literacy dimension into food capability. This dimension foregrounds informal and experiential learning in increasing food proficiency and literacy. Food literacy is in itself a multidimensional concept that includes conceptual and declarative knowledge (gaining information about foodstuffs, for example nutrition), procedural knowledge (using the information in food decision-making) and the ability, opportunity and motivation to use the knowledge in practice, for example in food preparation (Block et al., 2011). Voola et al.’s (2018) framework enhances our understanding of food well-being. More recently, scholars have started to make connections between food literacy and food citizenship, proposing wider literacy about the food system to be a condition for nurturing food citizenship (Meyer et al., 2021; Rowat et al., 2021).

Given the framework’s focus on food well-being in poverty, centering familial relations and experiential learning, we found it useful as a framework for our exploration of the role of CSA in driving food well-being of food-insecure households in the United Kingdom. It offers a two-prong approach for our investigation: firstly, it enables us to consider more holistic outcomes of our intervention, rather than just food security and health, i.e., to what extent CSA membership contributes to people’s individual and collective food well-being? Secondly, it facilitates the exploration of the different factors that influence well-being. Its foregrounding of relations enables us to consider how CSAs and other AFNs are uniquely placed to impact not just food security, but broader food well-being. Given that most prior research has focused on consumption factors (Scott and Vallen, 2019), in this paper we enrich the discussion by concentrating on how improving accessibility to CSAs simultaneously tackles other factors that holistically contributes to food well-being. CSAs also provide an opportunity to consider how food well-being can better connect with broader questions of societal and planetary well-being such as environmental, social and economic sustainability of food systems and be a key component for a transformed food system.

2. Methodology

2.1. Community-supported agriculture project partners

This research has been co-produced with four CSAs and two food aid organizations. Data were collected via in-depth interviews with food-insecure CSA members to understand how they interact with CSAs and benefits arising from those interactions as well as barriers to realizing additional benefits of CSA membership. In total, 38 households received a weekly veg bag for a period of 2–4 months of which 16 participated in interviews before receiving the veg bag and towards the end of the growing season.

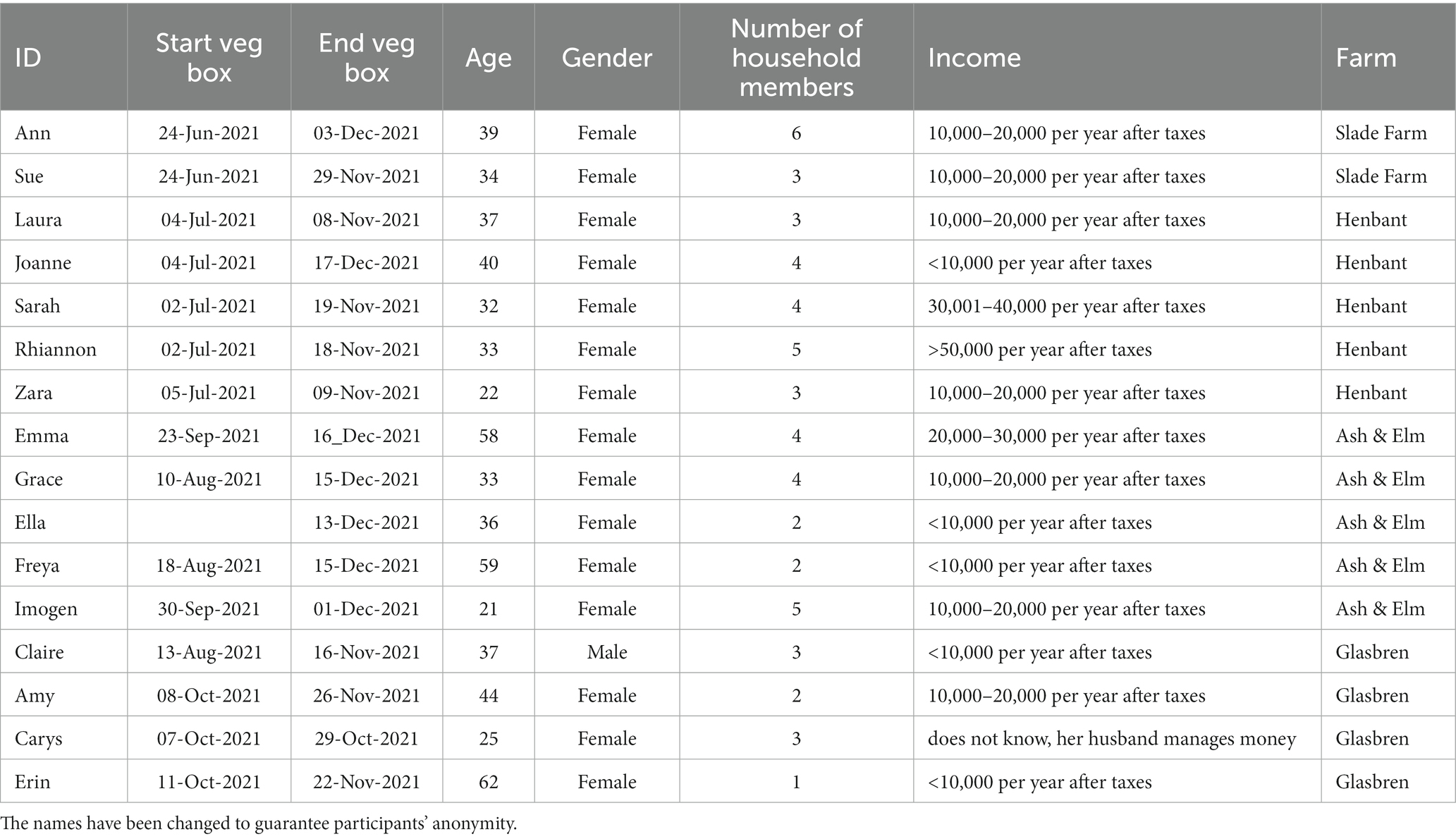

The chosen farms were geographically spread across Wales (see also Figure 1) and expressed an interest in exploring solidarity models for making their vegetables accessible to food-insecure households. These farms were:

• Ash and Elm Horticulture, Llanidloes, Wales (5 acres).

• Glasbren CSA, Bancyfelin, Carmarthen, Wales (1.5 acres).

• Henbant CSA, Clynnogfawr, Caernarfon, Wales (75 acres).

• Slade Farm Organics, St Brides Major, Wales (5 acres).

Figure 1. Food desert map for Wales. The yellow circles indicate where our case study farms are based. The e-food desert index (EFDI) is a multi-dimensional composite index for GB which measures the extent to which neighbourhoods exhibit characteristics associated with food deserts across four key drivers of groceries accessibility: (1) Proximity and density of grocery retail facilities (2) Transport and accessibility (3) Neighbourhood socio-economic and demographic characteristics, and (4) E-commerce availability and propensity. Source: mapmaker.cdrc.ac.uk.

Our farm partners were encouraged to partner with local food charities to help support their work with food-insecure households. The two charity partners who participated in the project were:

• Splice Child and Family Project, Bridgend: offer a family-centered service which aims to support parents/carers to play and learn along with their children which helps to develop confidence and self-esteem. Splice provides emotional and practical support to families.

• Siop Griffiths, Penygroes, Gwynedd is a Community Benefit Society run for the benefit of the whole community.

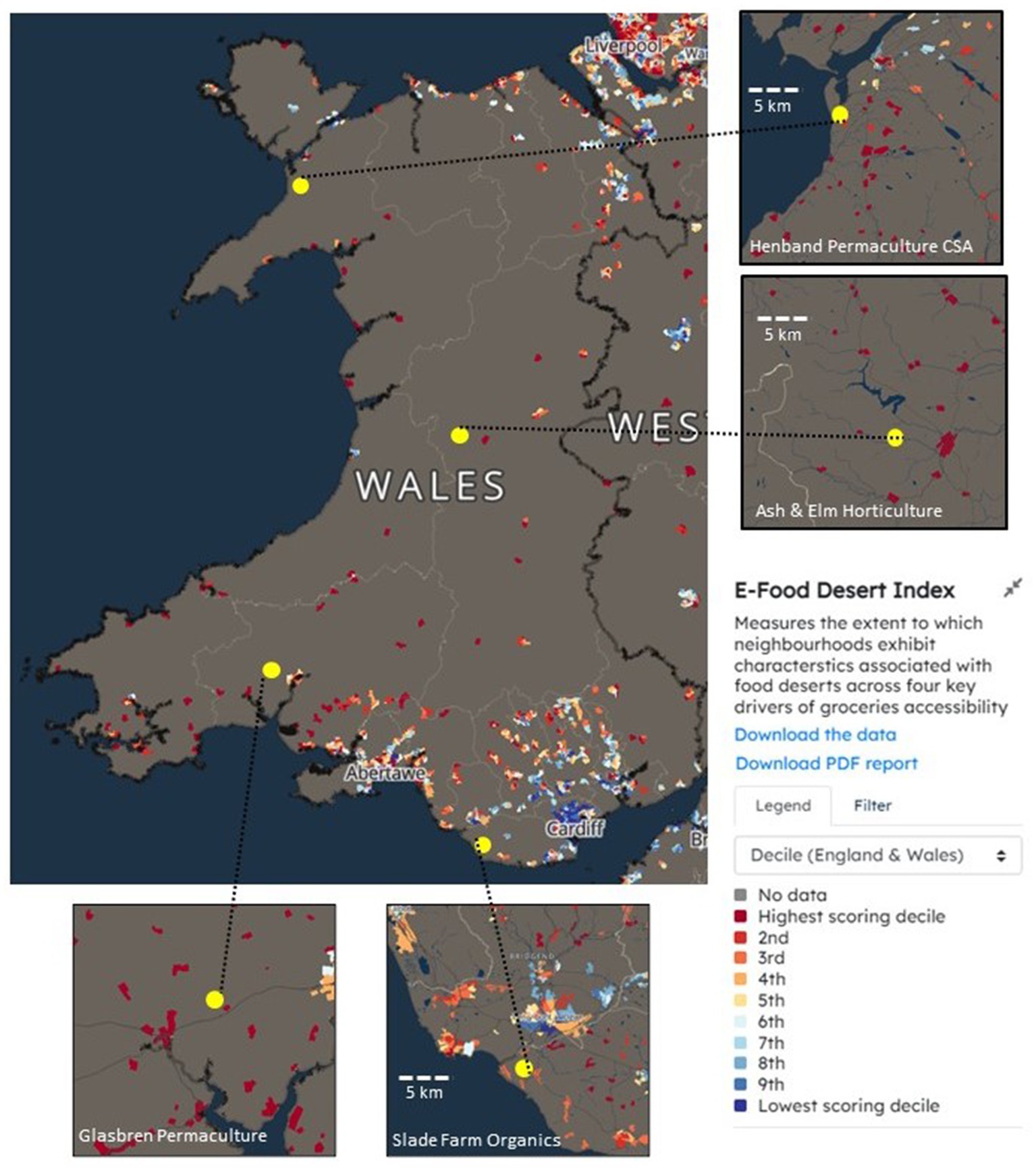

2.2. Procedure: free CSA membership, participant recruitment and interviews

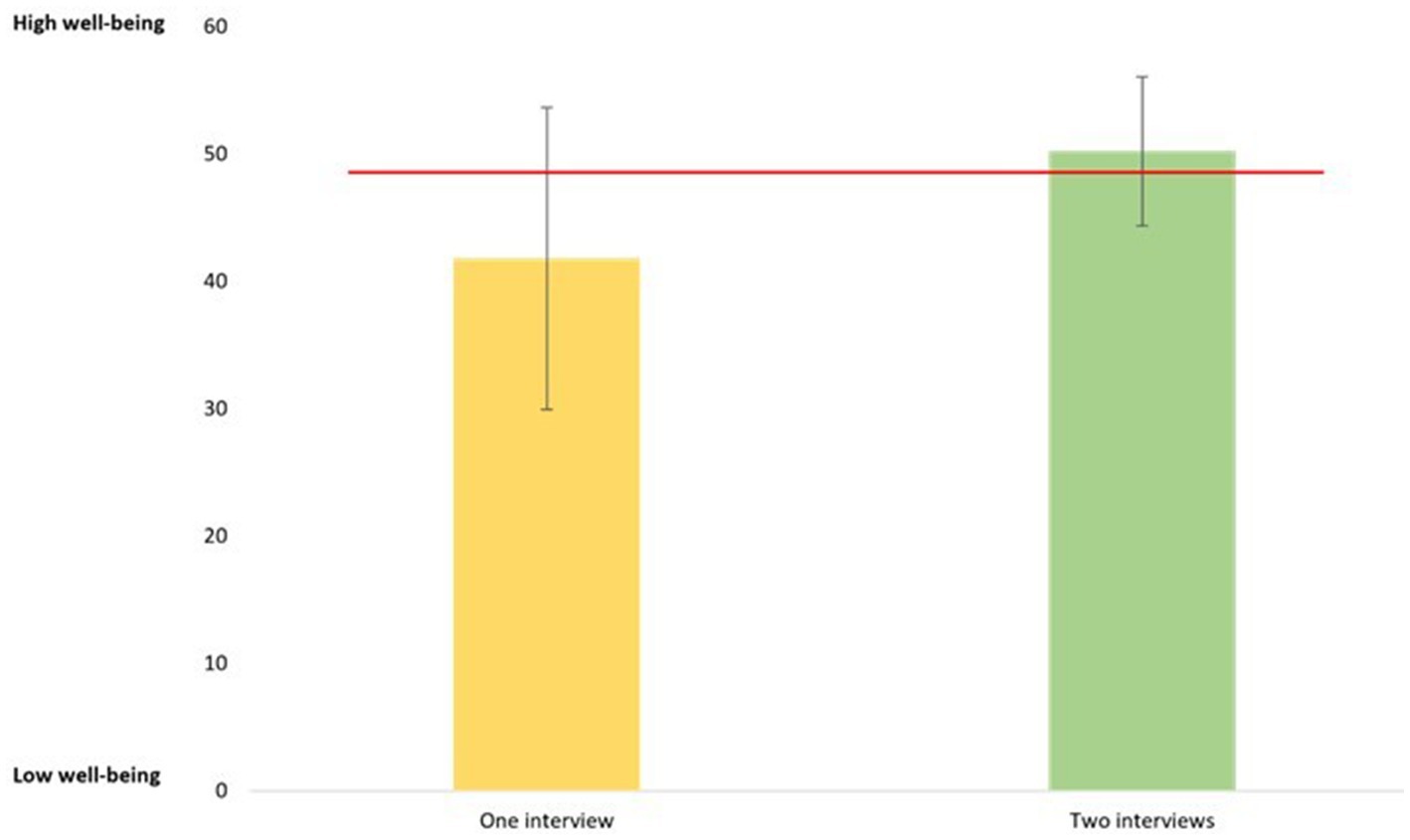

Most participants were female and tended to be young to middle age (see Table 1). Most participants had a below United Kingdom median household income1 and many experienced food insecurity expressed in either a subjective perception of food insecurity during the interviews and/or through reporting of skipping meals for financial reasons. To measure food insecurity, we asked the following four questions: In the last month have you or anyone else in your household done any of the following because you could not afford or access food: (a) found it difficult to afford to buy your weekly shop? (b) had smaller meals than usual or skipped meals? (c) been hungry but not eaten? (d) not eaten for a whole day (Figure 2)? These questions were adapted from USDA National Food Security Survey (Coleman-Jensen et al., 2021).

Figure 2. Assessment of food insecurity among participants before and during the delivery of the veg bags.

Participants were recruited either through the CSA partners or local food aid charities that supported low-income and food-insecure households. Participants were selected based on household income and knowledge of the presence of food insecurity through the food aid charities. Participants received an information sheet with an invitation to take part in the project through our project partners. They were incentivized to join the study by receiving free weekly vegetable bags from the host CSA for the duration of the harvest period (July to November/December 2021). Participants in the project became full members of the CSA veg bag scheme for 2–4 months; the length of the project was limited due to the length of the harvest season, after which the farm partners did not provide veg bags. They received the same information from the CSA as other members, pertaining to the foods that they were growing, recipes for how to use the vegetables, opportunities to visit the farm and volunteer or attend other events that the CSAs hosted during the season. We encouraged participants to get involved as much as they wished.

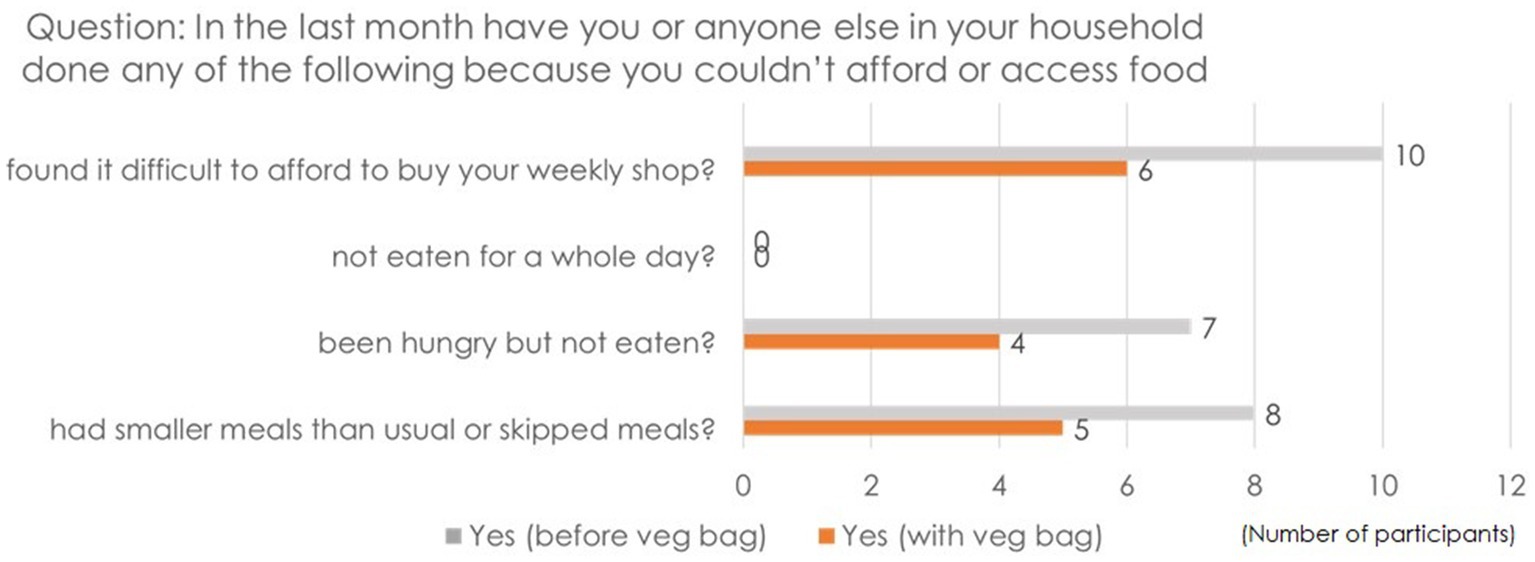

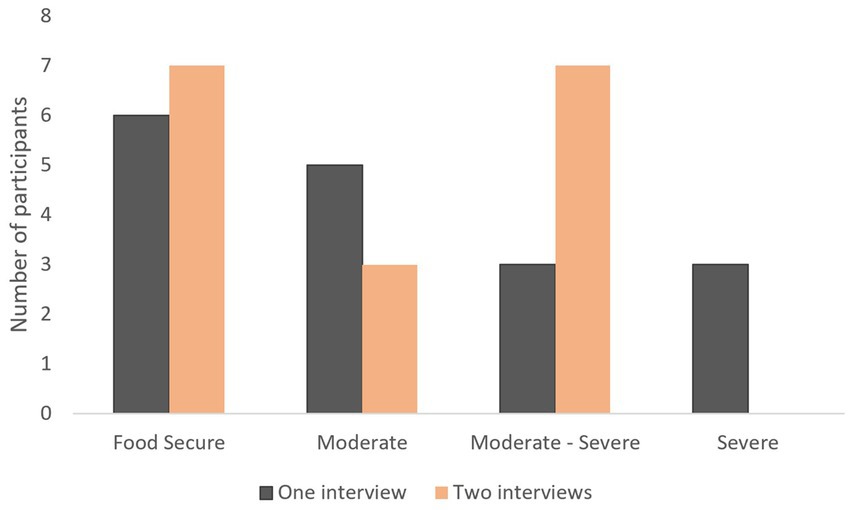

To assess the impact of the CSA membership, interviews were carried out pre and post project participation by phone. The interviews included questions about participants’ diet and consumption patterns, experiences of the membership and its impacts and three proposed solidarity models for future use. Most interview questions were open-ended; however, a few interview questions were closed and covered areas such as demographics, food insecurity and well-being. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental well-being Scale was used and measures mental well-being with 14 items that relate to an individual’s perceived mental well-being in the prior two weeks (Stewart-Brown and Janmohamed, 2008). In total,16 participants representing 16 households took part in both the pre and post veg-bag interviews (Table 1). Initially, 44 households signed up, of which 38 took part in the initial interview before receiving the veg bag. This means that the dropout rate was relatively high. We compared some key indicators between the drop-out sample and the participants who completed both interviews and found some relevant differences, for instance, lower well-being of dropout participants in comparison to those who completed two interviews (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Pre-interview Well-being score for participants that did not complete the study (i.e. only one interview = yellow bar) compared with those who completed the project (i.e. Two interviews = green bar).

In the workshops with our project partners, we reflected on potential barriers these households may have experienced that led to a lower participation rate in the post-interview. These included the interview timings (particularly busy and stressful time before Christmas) and also higher non-participation rates in areas not partnered up with a food aid organization. The initial 44 households were chosen by our food aid partners and the participating farms. The number of households was determined by multiple factors including limited amount of funding, farm capacity to generate additional veg bags and accessibility to households that were willing to participate. Conversations with our food aid partners revealed that, while there were many low-income households that would qualify to take part, the willingness and capacity for many of these households was limited – often linked to mental health issues and distrust in institutions. As has been noted elsewhere, severe food insecurity is linked to extreme chronic stress (Smith et al., 2023), which reduced potential participants’ capacity to take part.

In addition to the interview data represented here, we conducted a workshop with the project partners after the harvest season. The farms and food aid charities discussed their experiences with the projects and various activities and efforts to build a sustainable solidarity model for continuing to provide veg bags for food-insecure households going forwards. The study methods were approved by the University of the West of England’s Ethics Committee (reference number: HAS.21.07.166, Ref: JW/lt) and Cardiff University School of Psychology (reference number: EC.22.01.18.6505).

2.3. Analysis

We recorded and transcribed the interviews and anonymized the responses. For the data analysis, we applied a coding procedure derived from Braun and Clarke (2006). This involved filing all the data (using the software package NVivo) and identifying themes that existed within the data. Initially we revisited the research questions and coded any data that was relevant to them. For example, any data that mentioned interacting with the farmer or CSA community was coded as such: i.e., comments about farm visits were coded as ‘connection with the CSA’. The second stage of the coding involved identifying ‘in-vivo’ themes that were present in the data and coding them accordingly. These were strong themes that emerged from the data, but were not necessarily considered before the study began, either in our research questions or previous literature. One such theme was motivation for and enjoyment of cooking as an expected benefit of joining the scheme. The thematic analysis was carried out iteratively until no new themes arose, data saturation was reached (Fusch and Ness, 2015) and the definitive findings emerged. Below we describe our findings. We start with an overview of participants characteristics and then turn to exploring the impact of the CSA membership through the lens of food well-being.

In this paper we argue that CSA membership for low-income households has great potential to improve food well-being. To assess the impact of CSA membership, we used a well-being scale (see next section) and a measure of food security as indicators for food well-being. Additionally, and building on the food-well-being framework by Voola et al. (2018), we analyzed the qualitative data across four key dimensions, namely (1) food availability, (2) food capability, (3) food socialization, and (4) food policy.

3. Findings and discussion

3.1. Food well-being

Food security is a fundamental prerequisite for food well-being because it refers to the ability of all people, at all times, to have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for a healthy and active life (FAO, 2006). The sample in this study has a high prevalence of experienced food insecurity. Assessing an improvement of food security is therefore important to assess food well-being more generally. Although the research design did not allow to assess nutritional benefits, this was explored by an associated study (Sanderson Bellamy et al., 2023).

We used four questions to assess food insecurity. Our data indicates that self-reported measures of food insecurity decreased over the period during which participants received a weekly veg bag (see Figure 4). This indicates that the CSA membership had a positive effect on food insecurity by reducing it, although some still experienced hunger and skipped meals. Although the CSA membership provides access to organic vegetables, more foodstuff is needed for a sufficient diet, which might be a limitation of CSA memberships as the only additional source of food.

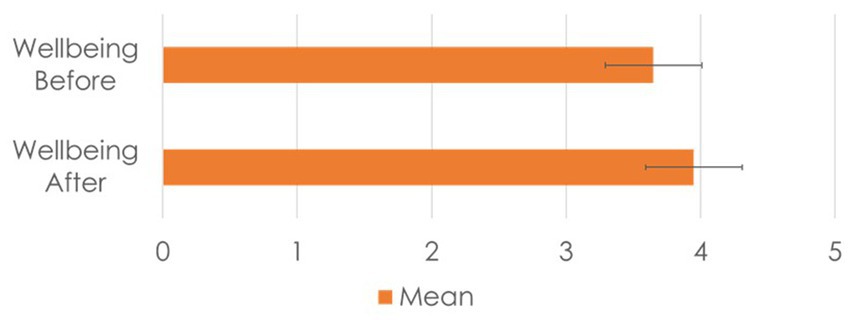

Figure 4. Results of Warwick-Edinburgh well-being scale. Example question included: “I’ve been feeling optimistic about the future” and “I’ve been thinking clearly”. 1 = None of the time, 2 = Rarely, 3 = Some of the time, 4 = Often, 5 = All of the time.

We used a general well-being scale (Stewart-Brown and Janmohamed, 2008) as another indicator to assess food well-being. Our results also show that well-being improved over the same period (Figure 3). Participants were asked to indicate what best described their experience over the last 2 weeks for statement like “I’ve been feeling optimistic about the future” (note: 5-point Likert scale with 0 = None of the time and 5 = All of the time). The difference (0.29 mean difference, 95% CI [0.458; 0.122]) was statistically significant, t(15) = −3.677, p < 0.05 with participants reporting on average lower well-being scores before receiving the veg bag (M = 3.64, SD = 0.359) compared to after receiving the veg bag (M = 3.938, SD = 0.406).

The level of food insecurity was compared for the two groups and found that the group that had pre-interviews only, had significantly higher levels of food insecurity (p = 0.046). Figure 5 shows the answers to the food insecurity questions, both groups equally found it difficult to afford their weekly shop, participants with pre-interviews only were frequently having smaller meals or skipped meals, or did not eat for a whole day, than those who completed both interviews. The level of food insecurity was measured between the two groups as seen in Figure 3. Participants that completed the pre-interviews only had higher levels of severe food security, determined by either answering ‘yes’ to all four questions or answering ‘yes’ to not eating for a whole day.

Figure 5. Number of participants that experience food insecurity. Here the comparison is made between the participants who completed one interview and then dropped out and those who completed two interviews.

Well-being is a multifaceted concept and is the outcome of many processes. Our findings indicate that CSA membership for low-income and food-insecure households does improve two components of food well-being, namely food security and general well-being. Previous research has demonstrated that food insecurity has a significant effect on the likelihood of being stressed or depressed (Pourmotabbed et al., 2020). We show that these effects can be reduced through CSA membership.

In the next section we explore the dimensions of food well-being further by analyzing our qualitative data building on Voola et al.’s (2018) food-well-being framework. In addition to the four dimensions identified by Voola, namely (1) food availability, (2) food capability, (3) food socialization, and (4) food policy, we found a fifth cross-cutting dimension that is particularly relevant in the context of CSAs, which is food relationship (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Revised food well-being framework that integrates the dimension of food relationship for food well-being.

3.2. Food availability

All collaborating CSA farms were predominantly located in so-called “E-Food deserts” - geographical areas that exhibit especially low accessibility to groceries. The key factors considered in the E-Food-Desert Index developed by Newing et al. (2022) and used as an indicator in this paper include (1) Retail opportunities (i.e., distances to nearest large grocery store), (2) Transport and accessibility (i.e., travel time to nearest grocery store by car and on foot), (3) Neighborhood socio-economic and demographic indicators (i.e., income deprivation, car ownership, pensioner in household), and (4) Online groceries (i.e., propensity to shop online and availability of home delivery). The index highlights inequalities in access to groceries, especially to fresh vegetables, which are often more expensive and limited in very small local stores. Rural Wales, where all four case studies took place, is characterized by remote and rural communities with poor access to both physical and online grocery stores (see Figure 1).

This was corroborated by research participants who reported the desire to access more fresh produce locally from small producers, but noted financial inaccessibility, physical availability or transport as main barriers to achieve that:

Interviewer: “What would the ideal food purchasing look like? So if you could just imagine anything?” Emma: “I think it would be all locally, or most of it locally sourced. Fresh and well not every day but you know every few days, I wouldn’t have to do a big shop in one go. As much fresh stuff as possible rather than tinned stuff - more fresh stuff rather than processed.” Interviewer: “And what do you think are the barriers to achieving this at the moment?” Emma: “Cost. And to certain extent availability [pause] and time to a certain extent as well, it’s great, you know, you go around the bakers and the butcher’s and the veg shop and things but it does take more time than just getting everything [in one place].” Emma, 58, household of three.

The CSA membership improved different aspects of people’s food availability, including physical availability, economic accessibility, quantity, quality and variety. Firstly, it made local and seasonal fruit and vegetables more available. The vast majority of participants reported a positive impact of receiving the veg bag on their diet, mostly focused on boosting their vegetable consumption. There was a statistically insignificant increase in people’s intake from on average 2.7 portions of fruit and veg reported before being a member, to 3.2 at the end of the project. Some participants also reported that receiving a free veg bag also made finances available for buying other food. This indirectly increased accessibility of other food, as well as reduced concerns about exceeding weekly budget and thus improved mental well-being. This is important because as prior research shows, households who are food insecure consume less fruit and vegetables than households who are food secure (Maguire and Monsivais, 2015). This discrepancy is exacerbated by a current cost-of-living crisis when in the last three months of 2022, the total amount of vegetables purchased in the UK decreased by 8% compared to the same period in 2021, and nearly 16% compared to 2020 (Veg Power, 2023).

For many participants, improving the quality and quantity of vegetables in their diet was a key contribution of the scheme and they valued the diversity the veg bag brought every week, allowing them to be more ‘adventurous’ (Joanne, 40) or ‘experimental’ (Erin, 62) in cooking:

“To be fair, it’s encouraged the children to, obviously, eat more veg, and they’ve been excited to see what comes on Thursday, because in the veg bag we don’t obviously get to choose what we’ve got in there, it’s literally what is available at that time. So there’s some things that we wouldn’t usually go and purchase in the shop or … or, you know, in the local supermarket or anything, so they’ve been really excited to try new things and stuff, so it’s been really encouraging to see them get excited, and they’ve wanted to come and volunteer as well down at Slade Farm, which we have done.” Ann, 39, household of six.

As the participant highlights, receiving a seasonal veg bag without the choice of what goes in it exposed the whole family to new kinds of vegetables they would not usually eat. This was especially important for families with children, where a common coping mechanism with food insecurity is limiting purchases of food that risks not being eaten. Therefore, families are less likely to experiment and buy new foodstuffs that may not be liked by their children and potentially wasted (Burns et al., 2013). In contrast, being a member of a CSA scheme allowed families to try new varieties of produce and ways of cooking in a low-risk environment. As the participant suggests, the learning and acceptance of new foodstuffs by her family was also supported by visiting and volunteering at the farm.

However, for a variety of reasons that included personal and familial preferences or too big a quantity, approximately half of participants were not able to eat all vegetables included in their weekly bag. This did not necessarily lead to increased food waste as surplus food was often distributed to extended family members and neighbors, and so further improved social relationships with and through food. Nine participants were explicitly concerned about wasting the produce; it is therefore important to recognize that this may have been a contributing factor to the high participant drop-out rate in the research study.

3.3. Food capability

The relational experimentation through embodied experience of food is an important building block for people’s food capability (Voola et al., 2018). This dimension foregrounds informal and experiential learning in increasing food proficiency and literacy. Food literacy is in itself a multidimensional concept that includes conceptual and declarative knowledge (gaining information about foodstuffs, for example nutrition), procedural knowledge (using the information in food decision-making) and the ability, opportunity and motivation to use the knowledge in practice, for example in food preparation (Block et al., 2011).

The prevalent discourses of food literacy scholarship focus on the need to increase people’s knowledge about nutrition and food to promote healthier food choices (Scott and Vallen, 2019). Similar emphasis on ‘becoming knowledgeable’ about food and food systems is also highlighted in food citizenship literature (Renting et al., 2012). This educational emphasis positions consumers/citizens as somehow deficient, presuming lack of conceptual or procedural knowledge. We’d like to offer a slightly different perspective on the role of veg bags in our participants’ food literacy journey. Even if the bags exposed participants to new varieties of vegetables, cooking practices and connections in the community, we do not endeavor to present CSA membership as a solution to the lack of their knowledge. Indeed, given that participation in the veg bag scheme and our research was voluntary and self-selected, the majority of participants warmly anticipated numerous ways they and their families would benefit from being part of the CSA community, including

“trying a variety of different veg” Rhiannon, 33, household of five.

“trying new things, new recipes” Grace, 33, household of four.

“make more healthier options on the home cook meals” Joanne, 40, household of four.

These motivations for joining the scheme are conditioned by pre-existing knowledge and interest in vegetables, food and healthy cooking, which the membership enables further exploration and expansion of:

“I guess, [I’d like] to try a variety of different veg. You know, you go into a supermarket buying the same things for the same meal. So in a way, to try and find, well I heard there will be recipes as well, you know, I’m all for that, because cooking is my specialty.” Rhiannon, 33, household of five.

Majority of participants also reported increased confidence in purchasing and preparing fresh vegetables.

“We were thinking about doing it before, but we didn’t have enough knowledge to be able to do it, and since we have started the veg bag and volunteering at Slade, we’ve now found … we’ve now got some… a bit of confidence to be able to do it. […] we’ve just… we’ve just started with, you know, the simple things, like I say, potatoes, tomatoes and stuff like that, so… and it’s fun for the kids.” Ann, 39, household of six.

Rather than filling empty vessels, the CSA membership built on and developed people’s food capabilities in two distinct ways. Firstly, the exposure to new varieties of local and seasonal vegetables. The diversity of vegetables grown on CSAs means that members receive vegetables (and varieties of vegetables) not typically found in supermarkets. The more unusual vegetables were often the topic of conversations on Facebook and WhatsApp groups supporting CSA members. For example this post on Facebook (accompanied by a photo of a celeriac), “It’s not the most handsome veg, but it’s very tasty and very versatile. Attached is a link for how to cook celeriac. Enjoy! We’d love to hear how you cooked yours.”

As the above post illustrates, exposure to new vegetables was often accompanied with information about ways to cook the vegetable and recipes to encourage development of new cooking skills. The information was circulated through various media, including physical recipe cards and newsletters in the veg bags and digitally on social media. The latter went beyond the two-way relationship between a consumer and a producer and enabled the members to share recipes, cooking tips and information between each other. The recipes and information about how the produce was grown were key in helping people with food utilization, as explained by a participant receiving vegetables from Glasbren:

“Yes, I think different recipes as well. And also, you know with the… there’s this insert in the box always, and I love it when they do… you know, when there’s a little suggestion of what to do with the vegetables? Because you know, most people have got… well, I don’t know most people […] myself, but you know, it’s usually certain vegetables you prepare in a certain way, and it’s easy to go to that same way of preparing that particular – or using – that particular vegetable, so there’s nice to have a simple suggestion to do it otherwise like for instance, leeks, there were leeks in the box, and I thought ‘Oh, gosh, I’m not a big fan of leeks’. I like leek and tomato and leek and potato soup, but I … I usually don’t buy leeks. And there was a suggestion on … in one of the inserts of the box just to have some you know, in the frying pan. Put some oil or butter in it, and you know, do some sliced leek and then with garlic. And it was just like the most amazing thing ever. I … ‘Why haven’t I? … It’s so simple!’ It was so delicious.” Erin, 62, household of one.

The routine, or ‘certain way to prepare vegetables’ she describes, was echoed across different interviews where participants reflected on how the membership gave them space and suggestions about how to experience vegetables differently. Many consumer-citizens reflected on the deliciousness and different taste of fresh produce from the veg bags. This sensory experience was important in building people’s food capabilities especially in connection to foodstuffs that were previously disliked. Children, who previously were not interested in vegetables, expressed enthusiasm and curiosity about the contents of the weekly veg bags delivered to their homes. Unlike an Instagram post, a recipe in a supermarket magazine or a Governmental 5-a-day campaign, CSA membership intersects all three dimensions of literacy as it makes both the knowledge and vegetables available in one package. It enables them to learn holistically about vegetables from inside out, viscerally, as demonstrated by the participant above.

Secondly, the scheme has helped participants to build on knowledge of their local food system, in two parts. First, it enhanced people’s awareness of seasonally grown vegetables: while many participants had a general knowledge about seasonality, participation in the CSA created more awareness about the particularities of seasonality, including the improved quality of taste of vegetables produced in season and picked at the height of maturity.

“Just because I now … I now know what to do with it, I now know, you know … it’s a lot fresher if you buy it, like sort of grown and not in a shop. They do taste different as well, they do taste nicer.” Laura, 37, household of three.

Like others, the participant here highlights the sensory difference of the produce she experienced as a member of the scheme, noticing the ‘nicer taste’. Secondly, participating in communications with CSA farm managers and members raised participants’ awareness of various issues related to the sustainability of the food system. In follow up interviews they expressed concerns about the economic, social and environmental sustainability of food production, especially in connection to over-reliance on imported produce, and the capacity of the local small farmers to meet the increasing demand.

Importantly, some participants also mentioned applying new knowledge outside the scheme when given the opportunity, for example

“looking at more organic veg in the supermarket” Rhiannon, 22, household of five.

“fitting more vegetables in my shopping” Joanne, 40, household of four.

“trying not to buy any vegetables that are not from the UK” Emma, 58, household of four.

These quotes demonstrate the transition that participants experienced from being a food consumer to being a food citizen. Participants engaged with exercising choices that better reflected their values. As a CSA member, they could participate in building the architecture of choice as opposed to being limited by the choices permitted by the architecture.

3.4. Food socialization

Family played an important role for participants’ motivation to take part in the study and receive a weekly veg bag:

“Well, I guess having the extra things to bulk up the slow cooker with really, you know, if push comes to shove that what’s great with veg, you can just all bung it in with a sauce. So it’s having more profits like that can well how, and also, it’s like I said before, trying to have a change and also, you know, getting kids to eat something possibly that I haven’t bought before. So yeah, but it will help definitely.” Rhiannon, 22, household of five.

Participants saw it as an opportunity not only to help with the weekly food shop, but to improve the level of health and nutrition in family meals by having a wider variety of fresh vegetables and trying new recipes. There were also some participants who were interested in teaching children about where food comes from and how it is prepared. In this way the veg bags enabled participants to express care for their family, their health and well-being (Cox et al., 2013). To some extent it also eased the gendered burden of feeding and caring for one’s family. When discussing the impact the veg bag had on her family’s diet, one participant said:

Zara:“I’ve been able to get more healthy foods inside my family. It’s made it [the diet] healthier.” Interviewer: “Okay. So, how so?” Zara: “I was able to cram more veggies, even if they were hidden, into different meals.” Zara, 22, household of three.

Research demonstrates that more family meals are associated with healthy eating in young people: increased consumption of fruits and vegetables and decreased consumption of fast food and takeouts (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2003; Walton et al., 2018). However, we know that cooking family meals also represented a challenge for some participants (n = 11). These challenges included negotiating different taste preferences, particularly among younger children, lack of inspiration and risk adversity to cooking a meal that may not be consumed because of taste preferences. As a result, prior to receiving a weekly veg bag, many families used a limited range of recipes and vegetables in meal preparation. After joining the schemes, seven participants suggested that receiving a veg bag helped them with the above challenges; that they felt more inspired to cook and other people (especially children) wanted to be involved in the process of food preparation. Family members expressed enthusiasm at seeing what was in the veg bag, cooking it and trying it. Some of this may be due to the surprise element of receiving vegetables that are ready to be harvested, instead of picking vegetables based on pre-defined preferences or meal plan. A number of participants have likened it to receiving a gift, like for Christmas:

“Because you never quite know what’s going to be in there, so when it comes, it’s quite exciting to see what’s in it, and you have to like plan for like lots of meals around, so I’m looking for new recipes, and yeah, sort of like what can we do with this, you know, celeriac or whatever, swede or whatever it happens to be? What can we do with that, sort of vegetables perhaps that I wouldn’t normally consider buying? Yeah, I’ve had some really great things to do.” Emma, 58, household of four.

For some participants, the surprise element was not always positive, as they received vegetables that the family did not like, and were worried about wasting it. Rather than preparing something new, they chose to give these vegetables to others, such as extended family members or neighbors. This sharing of vegetables also created new opportunities to share learning and information about the farms where the vegetables came from.

The lack of choice presented a double-edged sword for participants - excitement and joy from a variety of vegetables on one hand, and concern about wasting it on the other if it did not meet their various needs:

“At one point, I texted the woman, because I … it was so much, I couldn’t at time go through it, and I don’t like to waste, because I used to give them to other people because there were just loads in the box.” Rhiannon, 33, household of five.

Therefore, a common recommendation for the scheme improvement was to increase its flexibility and choice of what goes into the veg bags. Participants proposed different sizes of bags, variety of frequencies (alternate weeks as opposed to every week) and being able to tailor the content to their and their family needs. The inability to choose was listed as a second barrier to joining other schemes at reduced rate besides the price itself the inability to choose presented a barrier for joining hypothetical future schemes at reduced rate:

Interviewer: “What if it was offered at a reduced rate?” Joanne: “Possibly not.” Interviewer: “Okay. Any particular reason?” Joanne: “I just would find to be sort of not knowing what was in it more difficult to budget and factor into my own shopping and to being [inaudible] one day of the week I … I would prefer to potentially spread out my shops if … if it was free, I wouldn’t object to that. But if it was being purchased, then I don’t see it as being convenient for me.” Joanne, 40, household of four.

The balance in building more long-term democratic and sustainable food systems needs and short-term choices available to people currently need to be considered in any future schemes aiming to improve social injustices and focusing specifically on low-income households.

3.5. Food relationships

In terms of food socialization, most prior research has focused on either a family on one end as a key social and cultural site influencing the relationship between food and well-being (Block et al., 2011; Voola et al., 2018) or on the other end broader issues of ethnicity, social class and cultures - especially in relation to media and marketing - have been shaping people’s food well-being (Scott and Vallen, 2019). In our research we found that the middle level, community relationships, creates a sense of belonging and builds new social connections that influence food consumption. Therefore we propose a new dimension of food well-being that is focused on developing relationships in the food system that foster consumers’ and producers’ well-being. These relationships are critical for building all different forms of social capital that enable different actors in the food system to act collectively (Woolcock and Narayan, 2000; Vecchio et al., 2022).

Like others (Furness et al., 2022; Hennchen and Schäfer, 2022) we found that CSAs were fostering new connections between consumers and producers. Through receiving veg bags, participants felt more connected with the farm and farmers. They valued getting to know them, usually as part of the delivery, their friendliness and approachability, but also appreciated the ability to find out where their food comes from and how it is grown:

“I’ve definitely got more of an idea of how they operate and what they grow, and like the effort that they put in than I did before. Like I didn’t even know they existed prior to this scheme.” Sue, 34, household of three.

As part of the scheme, farms also organized volunteer days, open days and community events, such as pumpkin festival, accessible to all members. Only a minority of participants (n = 4) took part in those. Participants who did not visit the farm or engaged in events reported a lack of time or means of transport as main barriers. However, the majority of participants (n = 12) felt connected to the farm even without visiting it, just through receiving the veg bag, interacting with producers and others upon delivery and through media. This highlights the importance of different ways of connecting; all of our CSA partners prioritized face-to-face interactions with CSA members, believing that this is the primary way to build relationships with their members. However, our results show that connection with the farm can occur in many ways other than just face-to-face and on-farm interactions and that these connections hold meaning for CSA members. Those who attended events held at farms reported a deeper connection and it played a role in inspiring participants to grow their own vegetables, sharing knowledge and skills and further connecting their family members about the source of their food.

However, even the seemingly insignificant and brief interaction that occurred during the weekly veg bag delivery had a strong positive impact on participants. For example, for a participant receiving a veg bag from a food aid partner, it was a weekly opportunity to access other support from the project:

“She [food aid organization staff] used to come and collect, see… see if we were okay and our well-being, and if we needed anything for the baby, etc., and then… and then just basically handed us the veg bag, and she used to take the veg bags back as well.” Ann, 39, household of six.

During a period in which large parts of the UK population are arguably experiencing an endemic of loneliness (Nesta, 2023), the regular, weekly positive points of contact that members experienced as part of the CSA may sometimes be the only positive connection that food-insecure households have outside of their homes. This can be especially true for low-income households, managing the stress of overdue bills, contacts with social and welfare services and other financial demands on limited household resources, where every contact outside of the household may represent stressful interactions. Positive contact, free of demands, judgment or discrimination, is likely another reason why we see an improvement in well-being experienced by research participants.

Although participants preferred face-to-face interaction, the majority of them also found it useful being connected through different social media, as was also found in previous research (Furness et al., 2022). This included coordinating deliveries of veg bags through WhatsApp, sharing recipes in a Facebook group or watching videos about the farm when they were not able to get there in person. These mediated connections were established and maintained by CSAs, but also community food initiatives, which highlights the importance for building partnerships and cross-sectoral links for improved food well-being. This is also important to note for CSA managers, who are often time-poor. Significant positive benefits can arise from digitally mediated communications, which require less time and fewer resources for CSAs to manage (Furness et al., 2022).

For some participants, this connection also led to more awareness about the wider benefits and challenges of conventional food system. This demonstrates that even ‘weak ties’ between different and distant agents in food system (Van der Ploeg and Marsden, 2008) have a potential to build knowledge and bridging social capital to enable collective action. For example, after participating in the scheme, some participants expressed concern about the relationship between imported produce and economic viability of small local businesses:

“Yeah, it has built up my awareness to the fact that, you know, it’s difficult for a small farm as to keep up with mass produce. Yeah, I mean, the… the cost factor, the… the effect on smaller businesses, and the… the availability to keep up and compete. And also, just really not knowing the source of what you’re ingesting.” Emma, 58, household of four.

Relationships between community-scale food system actors also proved critical for the success of the intervention tested. Two of the CSA partners worked together with a charity partner within their region. The charity partners were able to identify food-insecure households and facilitate participation in the veg bag scheme. This was easily achieved because the food aid charities had already established trust with the participating households and knew which households were food-insecure. They were able to communicate the objectives of the project and support households in their participation. This facilitation role was critical to circumventing barriers to participation. All of the households participating in these two CSA schemes remained in the study for its full duration. A third CSA partnered with their local council, but the council had very little time to engage with the project and there was poor communication between the council, the farm, the participants and the research team. In addition, there was very little understanding of the particular needs of the participating households. As a result, there was a high rate of dropout among the food-insecure participants within this CSA scheme.

The final farm was unable to identify a partner with whom to work. They approached the local primary school and solicited participants through the free school meal program. In this case, there was almost no communication between the research team, farm and participating households; confusion prevailed about the expectations of the research project and the weekly collection of veg bags. Many veg bags went to waste because households did not know they were to be collected every week. There was a poor mechanism for households to communicate with the farm or the research team, because there were no pre-existing relationships in place. The CSA partner did not have the time to be able to properly engage with the participating households to explain the scheme, answer questions or support their involvement. The partnership between farms and local food charity partners was therefore important for reducing the burden of time for farms to engage with a solidarity scheme. Farmers were already time-poor, owing to the diverse number of activities they had to tend to on the farm, and the very small profit margins under which they operated. It was often untenable for them to support food-insecure households above and beyond the interactions that were already offered for all of the CSA membership.

3.6. Food policy (United Kingdom context with global application)

Food policy is a dimension that describes the relationship between the government and its policies and people as food consumers (Voola et al., 2018). The specific food policy environment in which the CSAs and our participants are placed influence their food choices and therefore their food well-being. The question of how we address climate change, biodiversity loss, soil security, water security, chemical contamination and other environmental issues, while also delivering healthy, nutritious food for all in the face of shrinking resources and a growing population is globally relevant. This question has been posed in a raft of recent internationally influential reports which have recognized the need for food system change, some calling for a ‘great food transformation’. In the UK, there are a growing number of legislations, policies and government strategies to redress food system failings. These include the Good Food Act 2022 (Scotland), Food (Wales) Bill and the National Food Strategy in England.

More often, policy is delivered in a piecemeal fashion in different sectors that intersect with the food system. For example, in Wales, there is the Sustainable Farming Scheme, Community Food Strategy, Social Value and Procurement Bill, Labor-Plaid Free School Meal Agreement, the Environment Act, and the Healthy Weight Healthy Wales Strategy, to name a few. The UK Agricultural Act (2020) sets the framework for agricultural subsidy payments in the post-Brexit era. Rather than making agricultural subsidies available based on the size of the farm, as was the case in the EU Common Agricultural Policy, the UK Agriculture Act requires payments to be made according to the provision of public goods. While the provision of public goods has so far been narrowly interpreted, e.g., healthy soils, tree planting and habitat restoration, increased water retention, and reduced pollution, there is an opportunity to join this legislation up with various other policies and strategies to achieve healthier diets and reduce household food insecurity.

Austerity policies from 2010 onwards have been criticized as a driver for increased food insecurity and poverty in the UK (Lambie-Mumford and Green, 2017), with approximately 20% of the population living below the poverty line (Social Metrics Commission, 2018). In Wales in 2018, 20% of people worried about running out of food and 26% of 16- to 34-year-olds surveyed ran out of food in the previous year (Irdam et al., 2018). The Food Foundation showed that 160,000 children in Wales were living in households for whom a healthy diet, as defined by the Eatwell Guide, was increasingly unaffordable. We then had the pandemic, where food-insecurity was estimated to have increased to 14% (Goudie and McIntyre, 2021), and further since the cost-of-living crisis, with current calculations of food insecurity in the UK at 20% (and at 27% for Wales; Armstrong et al., 2023). Similar increases in food insecurity have been experienced globally (World Bank, 2021). Further research highlights that in the UK, pre-pandemic, 26.9% of households would need to have spent more than a quarter of their disposable income after housing costs to meet the costs of eating according to the Eatwell Guide (Scott and Vallen, 2019). This is made worse by the cost-of-living crisis, where household disposable income will decrease by 7% over the two-year period between 2021 and 2023 (Office of Budget Responsibility, 2022).

The food system is estimated to be responsible for 30% of global carbon emissions (Crippa et al., 2021). In order to achieve global and national-scale net zero emission targets, we have to shift to more sustainable diets, with a higher proportion of fruit and vegetables that are produced sustainably. However, with even the Eatwell diet increasingly untenable for an increasing percentage of the population, achieving sustainable and healthy diets for all will not be possible. Significant policy shifts are required that address household access to healthy and sustainable foods. This is not just a food justice issue, it is necessary to meet UK legislative commitments to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.

Previous interventions on food security and poverty have failed to generate dietary behavior changes– because they are looking at a limited aspect of food security and consumption– calories, instead of thinking more holistically about food well-being. By focusing on building relationships back into the food system and connecting households to food producers, as is achieved by the CSA model, food well-being is addressed, with corresponding changes in dietary behavior. This focus on the community scale means that the relevant place-based approach is incorporated in how the community may choose to redress food insecurity and build their solidarity models. In the case of our partner farms, their rural location made it difficult for households to physically access the veg bags. In these cases, farms implemented procedures for delivering the veg bags to the participants. This often resulted in weekly chats with families, forming a regular positive point of contact. Particularly during the pandemic, this was very important as loneliness had a great impact on some people.

One CSA partner was running a well-being center which, among other things, installed a community freezer. Surplus vegetables were cooked into meals and made available in the community freezer. That way, people had access to fresh vegetables but were not facing the barrier of learning how to cook them or having limited cooking utensils. Another CSA was doing regular (weekly) cooking demonstrations and workshops to encourage people to cook and engage them with the vegetables. They made the cooking demonstrations publicly available online. Some farms were sharing recipes to provide support for cooking with the vegetables; one of the charity partners started a Facebook group for participating food-insecure households to support recipe ideas and stimulate enthusiasm for cooking unusual vegetables in child-friendly recipes.

Our farm partners also took different approaches to generating funds to support their solidarity schemes. One farm partnered with its members and the charity partner to plan fundraising activities to cover the cost of veg bags. The CSA members brought different ideas, skills and capacity to eventually decide on organizing a community farm fun day. The event attracted 200+ visitors and raised £1,300 and gave the CSA members agency within the community food partnerships. In addition, it shared the burden of fundraising across all partners. Farm partners often had volunteer days when CSA members could come to the farm and help with different growing activities. Although the rate of participation was not often high, participants appreciated the opportunity to participate, contributing to the sense of belonging within the community.

This approach differs from a national-scale policy that assumes one approach can address food insecurity in all of its different forms. The Scottish Good Food Nation Act, the Food (Wales) Bill and the English National Food Strategy recognize the importance of supporting community-scale actions to help drive this change from the bottom-up and seek to create a national-scale framework for supporting community-scale actions. In all three devolved nations, the legislation and strategy take a food system approach to policymaking, aiming to link up the different challenges across the food system and to create synergies across sectors for achieving a transformation of current food system functioning and outcomes.

4. Policy recommendations

The results presented here demonstrate the power of community-scale actions to reduce household food insecurity and improve well-being. While much of the financing for the solidarity schemes implemented in the Accessible Veg project came from individuals, there is a role to be played by governments (both local and national scale) in the form of increased and sustained financing. One source of this funding can result from implementing ‘public money for public goods’ payments for community-scale supply chain participants. This can create a source of long-term and secure funding for community growers, suppliers, distributors, and other organizations involved in local food provision services that result in improved environmental sustainability as well as positive public health outcomes. This policy approach can support a more diverse range of actors engaging in community-scale supply chains, generating more resilient consumption patterns that align with health, biodiversity, zero-emission policy targets and other non-food benefits. Additionally, by providing long-term grants for sustainability to organizations involved in community-scale supply chains, such as food hubs and CSAs, governments can reduce administrative burden and loss of capacity and institutional knowledge owing to high turnover related to uncertainty experienced by organizations relying on small, short-term grants.

Other funding recommendations based on outcomes from the Accessible Veg project include developing funding pots for small projects, initiatives and best practice projects (in the range of £5,000) that can be accessed quickly to help farms and/or charity partners to establish a solidarity veg bag scheme or other social innovation that circumvent barriers to participation for food-insecure households. Initial funding enables CSAs to explore and implement the most productive and sustainable model of solidarity for long-term provision of veg bags for food-insecure households. The CSA partners we worked with appreciated the opportunity to use the research funding in the first year to cover the costs of the veg bags, as this enabled them to take risks, experiment and learn how much money they could generate and how many weekly veg bags could be sustainably supplied.

The successful partnerships between the CSAs and local food charities demonstrated the benefits of supporting local partnerships between actors in the food systems. In the UK, the Sustainable Food Places, co-organized by Soil Association, Sustain and Food Matters, provides support for local food partnerships across the UK. Sustainable Food Places has nurtured networks from initial formation to maturity, through their bronze, silver and gold award program. The English National Food Strategy similarly recognizes the need to support community-scale partnerships and actions (Dimbleby, 2021).

Support and funding can be made accessible to people that experience multiple vulnerabilities, often linked to poverty (e.g., food and fuel insecurity, mental health and physical health issues). Some examples that already exist in its early stages are social prescribing and food vouchers that can be used towards CSA memberships. Healthy Start vouchers in the UK, and similar voucher schemes used elsewhere, such as in the USA can be used to support food-insecure households to access locally-grown and sustainable produce. Vouchers are supplied to low-income households and can be used at retail outlets for purchasing vegetables, dairy products, and meat. Again, this can be achieved through partnership building and a potential integration into the Healthy Start or equivalent voucher program.

4.1. Scaling-up CSAs

One important consideration from this work is about how CSAs can be scaled up. Naturally CSAs are confined geographically to their size and reach. Multiple components, including accessibility to land to expand growing activities, and distance for CSA members to reach the farm are physical factors that limit the scalability of CSAs. Other than increasing in size, another approach to scaling-up CSA activity would be to scale out and increase the number CSAs operating.

There is a lack of evidence about how to best scale up interventions targeting sustainable diets and associated food innovation such as CSAs (Gupta et al., 2022). A guide for scaling up population health interventions published in collaboration with the Australian Department of Health and Aged Care (Milat et al., 2016) recommends four key steps, which can be adapted to considerations around the scalability of CSAs and other community food initiatives.

1. Assessment of scalability, including effectiveness, potential reach and adoption, and identifying the audience for and feasibility of the intervention. This study provides relevant information about engaging with audiences that tend not to be reached by CSAs (i.e., food-insecure households). However, more evidence is needed about how CSA memberships can be made accessible to different consumer groups and how these engage with the CSAs.

2. Develop a scaling-up plan, including outlining a vision of a scaled-up intervention, situational and stakeholder analysis, and evaluation program. Currently, there is a lack of a vision for what community food might look like. National Governments are developing related food legislation and strategies (e.g., Good Food Nation Act, Scottish Government, 2022). For example, the Welsh Government is developing a Community Food Strategy in which they encourage the production and supply of locally-sourced food in Wales (Wales Programme for Government, 2021) and the Food (Wales) Bill would implement a process for developing a national food strategy. The findings in this paper can help develop a vision for the future of community food. However, to implement this, it needs clear leadership and co-production of a strategy with stakeholders to develop a scalable plan.

3. Resources and a foundation of legitimacy for scaled-up intervention, including a consultation with stakeholders (e.g., citizen’s assemblies, stakeholder workshops with farmers, food retailers, etc.), community support, and government leadership are key. Projects like the one presented in this paper, that work collaboratively with food producers and food aid charities make an important contribution to the legitimacy of scaled-up programs. However, more work is needed in this space and concerted effort to bring these voices together.

4. Coordinated action across key actors, including governance and media narrative, is needed to ensure sustainability and long-term success. CSAs rely on and are a cornerstone for community food and are a key driver for a food system transformation. Coordinated action across the sector is therefore needed to successfully scale-up CSA initiatives and transform the system.

To develop a more robust evidence base of the effects of CSAs on people’s health and well-being and, more widely, the food system, efficacy testing and real-world trials are needed. Research is often limited to pilot studies with rather small samples.

5. Conclusion