95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Food Syst. , 09 August 2023

Sec. Social Movements, Institutions and Governance

Volume 7 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2023.1198290

This article is part of the Research Topic Innovations in Gender Research for Sustainable Food Systems View all 14 articles

Jessica Susan Marter-Kenyon1*†

Jessica Susan Marter-Kenyon1*† S. Lucille Blakeley2†

S. Lucille Blakeley2† Jacqueline Lea Banks3†

Jacqueline Lea Banks3† Codou Ndiaye4

Codou Ndiaye4 Maimouna Diop5

Maimouna Diop5Achieving gender equality in agricultural development is fundamental to reductions in global poverty, hunger, and malnutrition. African women make important contributions to farming and food systems; however, their efforts are often hindered by inefficient and inequitable allocations of intrahousehold labor and time that render women time poor. Time poverty is a root cause of women’s marginalization in rural Africa and an important area of inquiry for feminist scholarship. While gendered time use and time poverty have been researched in many different contexts and countries in Africa, significant knowledge gaps remain. Most studies consider women’s time use divorced from gendered relations, and overlook children’s contributions. Other factors which may combine to influence women’s time burden but are often overlooked include seasonality, work intensity, household structure and composition, cultural norms, familial relationships and intrahousehold power dynamics. Further, the majority of research on gendered time use and time poverty in Africa uses quantitative methods applied to secondary data, which presents challenges for critically identifying and characterizing the confluence of various intrahousehold dynamics which impact women’s multiple roles, responsibilities, and consequently their work and time. This study adds important nuance to the existing body of research by offering an in-depth, qualitative assessment of intrahousehold labor allocation, time use, and time poverty amongst women, men, and children living in multi-generational, largely polygamous households reliant on peanut-farming in the Kaolack region of Senegal. Data collection took place in February 2020, with 111 individuals in three villages. We find that individual workload correlates with gender and age, but is further determined by the demographic composition of the household, the roles assumed by the individual and other family members, and the individual’s place within the social hierarchy. Women and girls in Kaolack are clearly at more risk of time poverty due to their dual responsibility for reproductive and productive work, especially during the rainy season. Furthermore, women’s workload in particular changes over the life course as they assume different roles in different life stages. As a result, women with older daughters and, especially, daughters-in-law are significantly less time poor than other women.

Gender gaps in agriculture are persistent, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa (Kristjanson et al., 2015). Many gaps stem from the fact that women in farm households are often overburdened by their responsibilities for both reproductive and productive labor (Arora, 2015). Intra-household distribution of work is “dictated by social norms that put women at a disadvantage” (Arora and Rada, 2017, p. 93); this often results in gendered time poverty (Blackden and Wodon, 2006; United Nations, 2020), one aspect of the multidimensional nature of poverty in rural Africa (Alkire, 2018).

Time poverty is a condition wherein people lack time for rest and leisure because their working hours are so long (Blackden and Wodon, 2006), and they have no possibility of reducing their working hours without falling (further) into economic poverty (Bardasi and Wodon, 2010). Many studies, including those employing the Women’s Empowerment in Agricultural Index (WEIA) tool, use 10.5 h per day as the time poverty line (Alkire et al., 2013; Adeyeye et al., 2021), while others have used thresholds of 12 h (Gammage, 2010; Arora, 2015), or 1.5 times the median hours worked (Lawson, 2008; Bardasi and Wodon, 2010). Gendered time poverty relates to differences in men’s and women’s “ability to change their schedule, their control or influence over their time use, and unequal time burdens” (Eissler et al., 2022, p. 1022).

While time poverty can also be experienced by men (Lawson, 2008; Soh Wenda and Fon, 2021), many labor-saving innovations in agricultural settings focus on productive activities dominated by male control. Further, Africa has yet to undergo the structural transformations in the household, including domestic labor-saving mechanization, that have taken place in developed countries (Dinkelman and Ngai, 2022). Due to patriarchal social norms, rural African women also have lower levels of time-use agency – an individual’s ability to determine what they do with their time in order to reach their goals – which is an important element of empowerment (Eissler et al., 2022).

Consequently, “time poverty is exacerbated among women in [African] agriculture” (Adeyeye et al., 2021). Women in Africa work up to 13 h more per week than men (FAO, 2009), and rural women dedicate more time to unpaid care work than those living in urban areas (Charmes, 2019). Indeed, women’s unequal responsibility for household work makes up most of the gender disparity in time poverty. Around the world, women provide more than 75% of the hours dedicated to household reproduction1; there are no countries where men spend more time on household work (Charmes, 2019). In many countries where this data is collected, as in Benin and Tanzania, women spend more time now on unpaid care work and less time on income-generating work than they did a decade or two prior, while men spend less time on unpaid care work (Charmes, 2019). Women contribute critical labor in agriculture, too, much of which is also unpaid and often rendered invisible (Lentz et al., 2019).

Time poverty is a root cause of women’s marginalization in many sectors, including agriculture, and impacts their own welfare as well as that of others (Alkire et al., 2013). In a comparative study of seven African countries, workload emerged as the primary cause of disempowerment in three countries, and in the top three causes in a fourth (Meinzen-Dick et al., 2019). Time poverty inhibits women’s ability to obtain and maintain paid work, adopt agricultural technologies, and participate fully in food production, and can negatively impact their ability to take full advantage of a wide range of agricultural interventions, such as extension services, financial services, accessing inputs, and finding support in producer organizations (World Bank, 2009; Floro and Komatsu, 2011; Whillans and West, 2022). Men’s failure to contribute their labor to unpaid reproductive work means that, even when women do participate in income-generating activities, they lose free time as they must still assume responsibility for reproductive work (Miedema, 2021). The many competing claims on women’s time result in inefficient tradeoffs and cause physical and mental stress (Arora and Rada, 2017), leading to negative consequences for - amongst others - household income as well as personal income (Blackden and Wodon, 2006; Kes and Swaminathan, 2006), nutrition (Njuki et al., 2016; Johnston et al., 2018), women’s access to formal medical care (Adeyeye et al., 2019), investments in children, and future poverty reduction (Bardasi and Wodon, 2010). Women’s high time commitments and responsibilities for reproductive work is a core indicator for gender inequality, and results in women having contaminated leisure or less time for leisure in general (Giurge et al., 2020). Further, leisure is a fundamental component of welfare and human rights, and enables the expansion of social networks and the development and deepening of social relationships, which are linked to pathways out of poverty (Lawson and Hulme, 2007).

For these reasons, recognizing women’s unpaid work and the ways social norms influence intrahousehold time use is fundamental for understanding and addressing gender inequities in well-being (Quisumbing et al., 1995; Arora and Rada, 2017). Identifying and disassembling gendered inequity in workload is a part of efforts to promote human rights and development. Target 5.4 of the Sustainable Development Goals is aimed at ‘recogniz[ing] and valu[ing] unpaid care and domestic work through… the promotion of shared responsibility within the household and family’ (UN Women, 2015). “Decent working time” is also central to the International Labour Organization’s goal of “promoting opportunities for women and men to obtain decent and productive work in conditions of freedom, equity, security and human dignity” (ILO, 1999; Bardasi and Wodon, 2010). Therefore, time use is a critical focus of gender studies and feminist economics, and research on the livelihood and survival strategies of the poor (Bardasi and Wodon, 2010; Arora and Rada, 2017; Stevano et al., 2019).

While research on gendered time poverty in high-income countries has a long history, far fewer studies investigate these issues in other parts of the world, and there is “still a large knowledge gap regarding women’s time use and time allocation on the [African] continent” (Dinkelman and Ngai, 2022, p. 59). As Stevano et al. (2019, p. 2) argues, “methodologies should be broad enough to encompass household socioeconomic status, composition, seasonality, and work intensity, as well as a focus on gendered relations rather than women’s time use exclusively.” Yet research in Africa has mainly not done this and, further, men and women are typically analyzed as internally homogeneous categories, overlooking within-group differences. Most studies use quantitative methodologies applied to secondary data sources, making it difficult to untangle the relationships underpinning inequities in time use. There is also scant evidence about the impact of development interventions on gendered time use (Johnston et al., 2018). Some women’s empowerment programs have been found, paradoxically, to increase gendered time poverty (Adeyeye et al., 2021), as have efforts to increase agricultural productivity and women’s incomes (EIAR, 2012). We know even less about how women’s time is impacted by contemporary trends in Africa including commercialization of agricultural production (Kennedy and Cogill, 1988), male out-migration, and the feminization of agriculture. This lack of basic understanding of how time poverty operates in rural African farming households inhibits progress toward the goals of development research and practice.

In an effort to add nuance to our understanding of gendered time poverty amongst farm households in rural Africa, we conducted a qualitative study in early 2020 in the Kaolack region in the Groundnut Basin of Senegal. This region, typified by large, multigenerational, and often polygamous households situated in close communities impacted by irregularly patterned seasons where family members presence and roles are in flux, changing both with the weather and over their life course, presents an opportune site for us to example the way these interacting factors converge to produce systemic and gendered inequities and agricultural inefficiencies.

The goal of the research is to open the “black box” of the farm household, using a qualitative approach to understand the concept, experience, drivers, and dynamic nature of time use and time poverty for men, boys, girls, and women over the life course within the particular cultural and geographic context of Kaolack, Senegal. As De Vreyer and Lambert (2020, p. 2) note, “inter-personal inequality in living standards within households is a largely uncharted territory.” Few studies compare men, women, and children’s time use, or investigate how relationships between household members influence labor allocation and levels of time poverty (Ilahi, 2000; Sow, 2010; Doss, 2013; Johnston et al., 2018; Daum et al., 2021). We also differentiate beyond “male” and “female,” to explore how sex intersects with other social categories in the context of time use and allocation. Finally, this research adds to our understanding of time use dynamics within (1) polygynous2 households, which are under-examined, and (2) within Senegal, which is likewise underrepresented: Senegal is not one of the 11 African countries that collect time use data in regular household surveys (Charmes, 2019; Dinkelman and Ngai, 2022) and we found just one (quantitative) study of time allocation in the country (Sow, 2010).

Time use and time poverty have been investigated for decades, starting in the 1970s with Vickery (1977), who defined time poverty as a 12-h workday. Time use itself has been used to understand gendered relations across many situations, but is more heavily deployed in Europe, Canada, and the USA countries (Bardasi and Wodon, 2010; Dinkelman and Ngai, 2022). However, given the low deployment in the rest of the world, there are several gaps in both time-use study methodologies and theoretical frameworks.

In sub-Saharan Africa, time-use studies frequently rely on interview and recall techniques as study populations are often not fully literate. There are logistical difficulties in deploying these studies, related to the interviewing techniques and differences in understanding what constitutes work (Bamji and Thimayamma, 2000; Abdourahman, 2010). Importantly, time-use studies may not adequately capture women’s work. To begin with, women often have many jobs, more so than men (Charmes, 2006). Men typically complete tasks sequentially, whereas women complete tasks simultaneously (Blackden and Wodon, 2006). Reporting simultaneous tasks can pose a problem-how many activities should be reported if a woman is performing childcare, preparing a meal, and cleaning laundry at the same time (Lentz et al., 2019)? Consequently, simultaneous activities are likely underreported, posing challenges for assessing work intensity (Blackden and Wodon, 2006; Lentz et al., 2019). Finally, surveys that use statistics as a framework for measuring time use often mask women’s work in agriculture, primary production, or trade activities (Charmes, 2006). There are difficulties in activity definition; many questionnaires fail to adequately measure non-market economy work, and time-use studies can be myopic in establishing what ‘counts’ as work (Abdourahman, 2010; Johnston et al., 2015). Time-use studies frequently embody the researchers’ value judgments of what constitutes work (Whitehead, 1999). Not only can women’s work be invisible to the surveyors, but it can also be invisible to the participants themselves: women often fail to categorize care as work (Arora, 2015). Therefore, women’s work is underreported in many time-use studies (Lentz et al., 2019). Additionally, many surveys do not capture seasonal variations in time use or work intensity, especially in Africa, Asia and Latin America (Charmes, 2015; Johnston et al., 2015, 2018).

There is much evidence globally that women work more hours in the day than men. Women’s work can amount to almost twice that of a man’s (Arora, 2015), and the ratio of time in unpaid work from men to women is more than double parity; in Mali, it can range from 2.3 to 14. Women often spend more time on farm work (Arora, 2015), and produce between 60 to 80% of food in low-income countries (Ransom and Bain, 2011), yet it is estimated that women are energy deficient for nearly 6 months of the year (Haswell, 1981). There is evidence that women experience more time poverty and contaminated leisure overall (Arora, 2015), where contaminated leisure is defined as work done during leisure time, usually childcare (Bittman and Wajcman, 2000; Mattingly and Blanchi, 2003). Finally, women who work outside of the home spend almost as much time as housewives on childcare and housework, with the difference being under 30 min per day, despite having spent 5–7 h performing income-generating activities.

The work women do is not limitless, or free, and time spent doing certain activities may take away from a woman’s ability to do other, more productive work (Komatsu et al., 2018). Women are typically responsible for taking care of children, the sick and elderly (Kes and Swaminathan, 2006) and ensuring their nutritional needs are met. Increased time in agriculture can result in a decrease in the quality of care for children or themselves-care may be skipped, reduced in frequency, or substituted (Komatsu et al., 2018). Women also must contend with tradeoffs between market and household responsibilities-women will take lower-paying jobs in order to be able to continue providing childcare. However, women’s time constraints can be offset by the presence of other household members who can substitute their reproductive work-primarily older daughters (Kes and Swaminathan, 2006), or older women (Johnston et al., 2015). However, there is evidence that the care provided by other children is of lower quality than the care provided by women (Komatsu et al., 2018). In many polygynous households, women rotate duties (Barret and Browne, 1994), as was seen in our study where families lived in semi-communal dwellings. However, household structures and hierarchical structures are permeable and can shift and change quickly. The groups that consume and the groups that produce are not always the same (Guyer and Peters, 1987), nor static, and men and women living in the same household may not pool their incomes or make all expenditure decisions jointly (Glick and Sahn, 1998). Different types of households (such as male-or female-headed) and the ages of the workers will influence the activities done by individuals (Whitehead, 1999).

In Sub-Saharan Africa, time spent on agricultural duties competes with domestic duties and may displace activities such as sleep, rest, or leisure (Johnston et al., 2015). Although the common assertion that African women contribute 60–80% of labor for agriculture has been contested (Palacio-Lopez et al., 2018), women do devote significant time to agricultural work, and are often responsible for food processing, crop transportation and storage, weeding and hoeing, while men frequently do most of the land clearing, planting, and crop maintenance (Haswell, 1981; Kes and Swaminathan, 2006; Boserup, 2007). In poor households in Ghana, women spend more time in agricultural work than women in non-poor households (Komatsu et al., 2018). Women must rely on men for access to agricultural land in many parts of West Africa and, in Senegal, men have sometimes taken productive land by establishing approval councils that consist exclusively of men in order to displace women (Nation, 2010; Komatsu et al., 2018).

For many purposes, women are considered helpers to men as opposed to individual economic actors (Ransom and Bain, 2011; Petrics et al., 2015). Both men and women face time constraints, but women experience more severe tradeoffs-paid work and unpaid work can take place simultaneously (Komatsu et al., 2018). Additionally, the gendered division of labor is not determined by education levels or land ownership, but rather societal norms (Arora, 2015). Finally in an effort to focus on women’s time use, men’s information may not be collected which can have ramifications for deducing how women’s time use and poverty relate to the household (Johnston et al., 2015).

Women may not be able to access information or services to improve their productivity due to time constraints as well. Evidence shows that women are more likely to adopt innovations (such as climate-friendly practices) when they are made aware of them (Kristjanson et al., 2017). However, women often say they do not have the time to sit and listen to information that may improve their productivity and time restraints prevent mobility needed to seek out extension services (Goh, 2012; Jost et al., 2015; Petrics et al., 2015). Time-saving technology might not be sufficient to address women’s time burdens (Johnston et al., 2018). Additionally, climate shocks increase women’s time poverty directly by requiring more time to be spent in agricultural labor and activities (Goh, 2012; Jost et al., 2015; Chaudhuri et al., 2021). Finally, agricultural interventions often require increased time commitments (Johnston et al., 2018) and can result in women spending less time working in feeding or food preparation (Johnston et al., 2015; Chaudhuri et al., 2021).

Kaolack is located in the Groundnut Basin of Senegal to the southeast of Dakar, bordering Gambia. It is one of 14 Regions in Senegal and contains three départements: Kaolack, Nioro du Rip, and Guinguineo (Figures 1, 2). The population of Kaolack was estimated at 2.09 million people in 2019, or about 13% of Senegal’s total population (Global Data Lab, 2019). As in the rest of the country, most residents are Muslim, but there is a minority Christian population. Ethnic groups in the area include Wolof, Bambara, Serer, Soce, and Peulh.

The majority of Kaolack households rely on agro-pastoral livelihoods based on a millet-peanut rotation (90% of the cultivated area), with additional crop diversification into hibiscus, cowpeas, sorghum, sesame and horticulture (Beaujeu et al., 2009). Cows and goats are the most common livestock; some households also own horses and donkeys for transport and land preparation. Cultivation is overwhelmingly conducted through family labor.

Typically, there is a household millet field owned by the head which is used as the basis for family consumption; additional plots planted with peanut or other crops are exploited by individual family members. Adult sons may be given land upon marriage; while Senegalese law acknowledges the right of women to own land, in practice it is rare for women to hold legal title (Sall, 2010); rather, women’s access to land for cultivation is typically mediated by male family members who retain ownership. This is primarily due to sociocultural taboos and restrictions; in Kaolack, according to the Secretary General for the Ministry of Agriculture, “tradition dictates that a woman should not inherit land at the risk of seeing misfortune or death befall her” (Thiam, 2016). Younger women tend to only grow peanuts, whereas older women with larger families tend to cultivate additional crops such as okra or indigo, and grain and irrigated vegetables` (Nation, 2010). Groundnuts grown by women are mainly on small plots of land and intended for household consumption (Tyroler, 2018). Women-managed plots tend to have lower yields due to myriad challenges. Women’s fields are allocated by male family members or male committees and are frequently smaller and have poorer soil quality; due to social norms, women’s fields are worked after their husbands’ and those of senior male family members (Nation, 2010). Finally, women are engaged in household and care work while men are able to dedicate more time to cultivation, and prioritize their own fields or the family millet plot (Tyroler, 2018; O’Laughlin, 2020).

In rural Senegal, the household structure relies on patrilineal family hierarchy and land is inherited through the father (Martin, 1970). It is common for extended families to live together in compounds (carrés). The carré is headed by an older adult male patriarch-the chef du carré - who inherits this role after the death of his father or older brother. There are three types of carré in Senegal, (a) the head of the carré who has only his immediate family as part of the carré, (b) the head of a carré with other households comprised of his relatives, (c) the head of a carré with households that he is not related to Martin (1970). Typically, the chef du carré is also the head of his own household (ménage). Nuclear households are typically defined as a family for whom a wife cooks food (ngak in Serer or ndiel in Wolof) (Martin, 1970; De Vreyer and Lambert, 2016). The carré is usually further comprised of additional ménages headed by an adult male (the chef du ménage) related to the chef du carré (e.g., a married adult son or brother), his wife or wives, and their unmarried children. In some cases – for example, when there is insufficient land held by the chef du carré – some or all of his sons and brothers will remain within the chef’s household rather than forming their own ménages within the larger carré. There are four types of households- (a) monogamous households, (b) polygynous households, (c) households headed by single, widowed or divorced men, and (d) households headed by widowed, or divorced women. Within this patrilineal structure, women leave their parents’ home to join their husband’s extended family upon marriage. These women are the daughters-in-law, of the husband’s parents. Their father-in-law may be the household head, or their husband may be the head if his father has passed or lives in a separate household.

Households are therefore both vertically and horizontally extended, meaning not only do multiple generations share resources (e.g., parents, grandparents, and grandchildren) but so do family members in the same generation as the household head (e.g., siblings, uncles/aunts and nephew/nieces). In the 2006–2007 Poverty and Family Structure survey of Senegal, 28% of household members were neither the head, nor one of his wives or children, and 49% of households include vertical and/or horizontal extensions (De Vreyer and Lambert, 2020). Nearly 40% of married women and 25% of men are in polygynous unions. The average household size in Kaolack is 14.2, and the total fertility rate is 6.2 (Global Data Lab, 2019).

The research presented here is part of a larger project on time use and time poverty amongst groundnut farmers in Kaolack aimed at developing a novel, more granular methodology for measuring time use data collection and was funded by the USAID Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Peanut, whose interest was in understanding the implications of gendered time use for the development of groundnut value chains in the country.

Qualitative data were collected from respondents living in three villages (Table 1 and Figure 2) located in the Kaolack Region of Senegal: Ndiobene Bagadji, Keur Taibe, and Bilory. The villages were chosen to maximize geographic and demographic variability. Keur Taibe and Bilory are located in north Kaolack on either side of a main road, near the medium-sized market town of Gandiaye. Keur Taibe is larger (~500 people), comprised primarily of Bambara households in two hamlets, with some Peulh and Serer households in two other hamlets, and approximately 15 min walking to the main road and 50 min to Gandiaye market. Bilory has ~225 inhabitants in two hamlets exclusively from the Serer ethnicity and, while further from the main road and Gandiaye (1.5 h walking), is much closer to the Saloum River, and therefore more of the men and women engage in fishing livelihoods in addition to agriculture. Ndiobene Bagadji is in south Kaolack, near the border with The Gambia and the protected Mamby Forest, and the most isolated of the three villages (3 h walking to the main road and the city of Nioro du Rip, and over an hour to the town of Porokhane), and is comprised of five ethnic groups clustered in one hamlet.

Data collection took place in February 2020 and involved focus groups, unstructured interviews, village transect walks, and direct observation. The research team was comprised of American and Senegalese researchers, and interviews were conducted in Wolof with translation to and from French for the benefit of the American researchers.

Ménages within our study sample ranged in size from 4 to 36, and carrés from 1 to 4 ménages. The largest carré we interfaced with had 4 ménages with more than 60 people living within it. Most polygamous households in our sample comprised the head and two wives, although at least a few household heads had three wives; this is consistent with what other surveys have found (De Vreyer and Lambert, 2020).

Research subjects included men, women and children of both sexes age 14 and older. In total, we conducted individual interviews and group discussions with 111 individuals in the three villages, 70 of whom (two-thirds) were women and girls, and 8 of whom were between the ages of 14 and 17 (Table 2). The research was approved by the IRB of the University of California, Santa Barbara.

While this study provides an important window into gendered time use dynamics and time poverty in rural Senegal, several limitations must be noted. First, the research was not structured, and not all questions were asked of all people. Second, while the qualitative nature of the research was intentional and provides useful insights into the social and other drivers of labor allocation and time use, we are not able to quantify, e.g., relative levels of time poverty. Third, we did not systematically investigate differences between ethnic groups, polygamous versus monogamous households, or between agriculturalists and pastoralists. Fourth, we conducted this research in only three villages of Kaolack, in a relatively short window of time. Therefore, detailed results may not be generalizable to all rural households in Senegal or the region, but we feel the broader results are, and that the research reveals important categories that should be considered in studies of time use and time poverty.

We found a clear pattern in the division of labor and set of ‘normative expectations’ (Eissler et al., 2022) related to how men and women spend their time.

The chef du ménage is responsible for managing household finances and furnishing the primary nutritional needs of the household, e.g., millet. Although both men and women are involved in agriculture, there are sex-specific tasks and responsibilities. Men are the primary decision-makers, and dedicate a larger proportion of their time to crop farming, as well as herding and guarding livestock. Men and boys are typically responsible for land preparation, planting, and harvest. Horticulture3 is also a primarily male activity in our study villages. Men contribute very little labor to domestic tasks such as sweeping, laundry, cooking, childcare, and the collection of fuel and water; they do manage the repair of buildings and household items. A few men told us they contribute to childcare and household cleaning, similar to what Sow (2010) found in the Groundnut Basin. However, she found a more significant proportion of male household heads reporting they assist with childcare (30%), cleaning and cooking (21%), and fetching wood (38%). Men also contribute income through their engagement in wage work, which includes a variety of activities from teaching, to working on other people’s farms, selling goods at the market, and serving as hunting guides for tourists. There is significant male out-migration during the dry season.

In contrast, women and girls labor on the fields of their male relatives and sometimes on their own plot if they have one, and have the time. Women’s participation in agriculture primarily involves weeding and post-harvest processing (e.g., shelling and sorting groundnuts, selecting seeds, pounding millet, and transforming grain). They also provide critical labor during harvest time, especially plucking groundnuts from the haulm of the plant. Depending on household size and composition, women and girls will assist in pulling the horse during land preparation and planting but ordinarily only if there is a lack of available male labor. In addition to their agricultural work, some women have small businesses – for example, making and selling sorbet, dried shrimp, and breakfast for fishermen in the area. They tend to spend the profits on condiments and extra food beyond the essential carbohydrates, paying for water at village wells, and purchasing clothes and soap for themselves and their children. Domestic work demands the majority of women’s time. Primary activities include cooking, collecting water, fuel (wood and/or dung), and edible leaves and fruit, laundry, sweeping and cleaning, and childcare. These tasks are universally considered to be women’s work.

There are some household and village-level differences in gendered expectations around time use related to familial and ethnic cultural differences, as well as geography. For example, women in Ndiobene Bagadji frequently managed and cultivated their own plots, whereas – due to land scarcity - most women in Bilory did not. Further, as Sow (2010, p. 110) notes, due to a variety of factors including the out-migration of youth and men, there has been “a dysfunction of the household head’s role” and a trend in more responsibility for women.

Time poverty (or gnak jot, in Wolof) was a concept easily recognized and understood by participants. Most, though not all, felt they experienced it personally. By way of illustration:

“Yes, we experience time poverty. For example, I might want to go visit friends, or a neighbor invites me to a ceremony, but I can’t go because I have work in the fields. Or, if a granary falls down, but we’re already delayed with our work in the fields, I might not be able to repair it right then” [45-year-old man, household head, Ndiobene Bagadji4]

“I do experience time poverty: when I do laundry, or have to prepare food, I don’t have time to come here [to the neighbor’s house] and visit my friends. I’m definitely busiest during the rainy season-I don’t have any time to play” [16-year-old girl, Keur Taibe]

“I live time poverty. It’s especially the case during the rainy season because I have to go to the fields, clean the house, do laundry, and prepare lunch and dinner. Sometimes I don’t have time to do the laundry and have to leave it for another day. Daughters-in-law have almost no time to relax or visit friends; we won’t even go to see our parents unless there was a ceremony” [32 year old woman, daughter-in-law, Ndiobene Bagadji]

• “I always feel time poverty. I do all the domestic work around the household, and I’m also responsible for getting vegetables from the market. I’m typically busiest in the evenings. I have to do dinner, look for water and wood, and sometimes even do laundry. So I really have no time for agriculture” [43 years old woman with no daughters-in-law, Keur Taibe]

Patterns emerged in gendered experiences of time poverty. For children, it was often related to being unable to play or attend school, and girls mentioned not being able to finish all their domestic chores on time. Men cited a lack of leisure time, the ability to conduct market work, and delays in agricultural work. Women’s immediate reactions were almost entirely centered around the inability to complete domestic tasks, loss of sleep, and to a much lesser extent lacking time for market work and leisure.

From our observations and their reporting, adult women are clearly time-poor relative to adult men, especially on a daily basis. For example, a 25-year-old in Keur Taibe described a typical day in the rainy season - which is the busiest time of the year - as involving approximately 7–8 h of agricultural work with a 3-h break after lunch, during which he spends time relaxing with friends and chatting. By contrast, none of the women or girls we interviewed described such a significant break in work during daylight hours. The burden of household production impacts women’s availability and ability to engage in income-generating work or self-investment like managing a farm, selling things in the market, or going to school. A woman in Bilory told us, “Men’s work is harder, but women work more hours.”

One driver of women’s relative time poverty is lack of access to labor-saving technologies. For example, men have priority over the use of charettes (animal-drawn carts); if unavailable, women have to walk. In general, animal labor is owned and managed by men, and there are more labor-saving technologies available for men’s work. Domestic tasks are very rarely marketized (e.g., there are paid laborers to help in fields, but no paid maids) nor mechanized (there are no washing machines) in rural areas. One notable exception is the existence of a millet grinding machine in Bilory: “It used to take us 2 h per week to pound millet. Now we have a machine nearby. If we have money, we can do all of it at once. If not, we have to do it by hand” (44-year-old woman, female-headed household, Bilory). However, as this quote illustrates, women must have access to money to pay for these technologies. The same is true for men to access labor-saving devices, but men’s work generates more income, and as described above, they largely control household finances and expenditures.

Beyond lack of time, we can also think about time poverty through the lens of the quality, drudgery, or safety of work: which tasks do people enjoy doing, and which do they find uncomfortable or unpleasant (Seymour et al., 2020)? In general, respondents of both sexes said they consider men’s work to be physically more demanding. A young adolescent from Ndiobene Bagadji reported that weeding is his favorite task, compared to burning bushes or pulling the horse at planting time. Most women said they prefer domestic work over their work in the fields. Pounding millet frequently emerged as women’s least favorite task within the household sphere because it’s physically taxing and irritating to the skin and eyes. One daughter-in-law in Bilory told us that cooking was her favorite task, along with laundry, “because a woman needs to know how to do these.” Another in Ndiobene Bagadji said she prefers cooking to laundry because the latter takes more time.

We probed respondents on the consequences of time poverty and found a variety of impacts.

Tasks can be delayed or put off for another day. For example, women in Bilory said they often delay eating breakfast until morning chores have been completed. The coincidence of cultural ceremonies and the groundnut harvest means that deshelling can be postponed: “They do not all start deshelling peanuts at the same time-it depends on the availability of women. In certain families, women are busy with ceremonies, and you have to wait until the women can regroup” (62-year-old chef du village, Bilory). This delay can lead to increased aflatoxin if groundnuts are not stored properly. Likewise, he described that, if a woman does not have help from her children or other women in the household, peanut shelling can be delayed because she has to spend her time on daily, time-consuming tasks like collecting fuel. People tend to prioritize tasks that are critical for survival and immediate livelihood functioning or that they are normatively expected to do. While some can be left for later – for example sweeping the courtyard, laundry and dishwashing – others must be completed that day, for example, cooking and indoor cleaning.

Sometimes, however, the task is simply not done. A middle-aged woman in Keur Taibe with no other women in the household, described: “Normally, women go to the fields after harvest and collect peanuts fallen on the ground [which we can use for our own purposes]. If there were many women in a household, maybe one would stay behind to watch the children. But since it’s just me, I do not have the time to do it, so other people collect the fallen peanuts on my field.” For her, the broader consequence is the loss of potential food and income. As a 41-year-old man in Keur Taibe described: “I work all the time. On Wednesdays and Thursdays, I have to go to the market to sell vegetables or mutton. When I go to the market, I cannot do horticulture. And some things at home or in the field will also suffer: first, I cannot take care of the animals. Or, if I had to do something in the field, like weeding, that would be difficult to manage too. So, in that case, the kids would take care of the animals for me and I would do the farm and garden work on a different day.” What he’s describing here is a tradeoff between market work (selling vegetables and mutton) and agricultural work (horticulture, animal husbandry, crop farming).

Time poverty obviously results in less time for leisure and social activities. A group of daughters-in-law in Ndiobene Bagadji described how, in the rainy season, they all feel they have much less time to relax or visit their friends and parents. Time poverty can also inhibit both men and women (but especially the latter)‘s ability to engage in economically productive activities.

And finally, time poverty can lead to children dropping out of school or reducing their attendance. As one teenagegirl in Keur Taibe said, “I did 3 years at school, but then I stopped because I wasn’t intelligent enough, and my mom did not have anyone to help her around the house.” A 16-year-old girl from the same village said she sometimes comes home early from school to sweep, do laundry, or search for water. We suspect that time poverty within the household may also affect boys’ schooling, but that they would be subject to different, potentially lower, rates (De Vreyer and Lambert, 2014; Le Nestour, 2018).

We also asked people how they cope with time poverty. Again, putting off non-critical tasks until later is common. Sometimes this leads to more time spent on the activity, for example, going to the well if you were too tired to wait for the tap to come on late at night. It’s also common to recruit other family members onto whom the task can be shifted. A 25-year-old PE teacher in Keur Taibe noted, “I cannot take care of the animals when I’m working at the school. My little brother does it for me instead.” There were four other strategies mentioned exclusively by women. First, during the rainy season, women will cook dishes that take less time, for example, thieboudienne (broken rice, fish, and vegetables) as opposed to mafe (a stew with a tomato-peanut butter sauce), which takes more time because the stew and rice are cooked separately. Second, women conduct work simultaneously. This is a typical pattern of gendered time use in rural Africa; the women we interviewed noted they tend to increase the simultaneity of work during periods of the year when they are particularly time-poor: “when school is in session, sometimes I’ll sweep the courtyard and do the petit linge at the same time as I do the cooking” (16-year-old girl in Keur Taibe). Third, women report losing sleep in order to not let anything fall by the wayside. Fourth, women will hurry to finish their tasks: “on Fridays when the men go to the mosque, or when the children go to school, you may cook faster so they can eat enough before they go.”

Intrahousehold time use and time poverty are gendered in the study area. However, the research revealed important nuances. Here, we discuss five dimensions we found have a strong influence on differences between, and within, sex groups: (1) household size, structure and composition, (2) intrahousehold social hierarchies and power dynamics, (3) an individual’s stage along the life course, (4) seasonality, and (5) aspects of the physical landscape.

Prior research has looked at household size in relation to gendered time poverty and time use in Africa, with mixed results (Lawson, 2008; Bardasi and Wodon, 2010; Arora, 2015; Adeyeye et al., 2019). In Rwanda, Habimana (2017) found that each additional household member decreased time spent on domestic work by 1 h per week for men, and 3 h per week for women, since the workload could be distributed across more individuals. On the other hand, in Mozambique larger household sizes were associated with increased time poverty for women (Arora, 2015) because more members results in more chores.

Respondents in our study reported that household size was a factor in their time allocation and experience of time poverty, specifically that fluctuations in the number of people in the house (e.g., people coming back to the rainy season) resulted in more time spent on cooking and laundry. Beyond that, we found quite a lot of evidence that the structure and composition of households matters. Ultimately, much of this comes down to substitution of labor, or the ability to shift responsibilities onto other individuals.

Studies conducted in Nigeria and Lesotho (Lawson, 2008; Adeyeye et al., 2021) find that households with a disproportionate number of children and the elderly require more care work, and Seymour et al. (2017) advance that “in large households where membership is largely adult male, the bulk of the domestic activities will fall on the adult women; hence, exacerbating their time poverty” (Adeyeye et al., 2021, p. 9). We similarly found that age distribution within Kaolack households is an important factor in determining how members allocate their time.

The presence and age of children influences the amount of time women spend on domestic tasks, and which ones they spend time on. A few individuals told us that women with more children tend to spend more time on domestic chores, especially when the children are young: “if you have a lot of little kids it can make doing chores harder because, when they undo the chores, you have to redo them.” Married women without young children are less busy as a result and, other things being equal, would be less time poor.

The sex of the children matters as well. As a middle-aged woman in Ndiobene Bagadji noted, “If you have a girl who is older she helps with housework but, if you have an older boy, he has to get married before you will have a daughter-in-law who can do work for you.” Younger boys also displace some of the domestic work of girls and adult women, including water and fuelwood collection. Older boys are essential contributors of agricultural labor, especially during land preparation, planting, and harvest; they also play an important role in livestock management. Consequently, adult men with fewer or younger male children in the household may be more likely to experience time poverty, which is what Sow (2010) found in her study of time use in Kaolack. The same would be true for men in households with few other adult men. In the context of land preparation and harvest, the chef du village in Bilory told us “If you are in a house with only one man, you’ll have to hire someone to help. Boys over the age of 12 help too. If the chef only has girls and cannot afford hired labor, then the women and girls will help with the land preparation.” Therefore, a lack of men and boys also influences the amount of time women and girls have to spend on agricultural work.

The presence of other adult women and older girls in the household strongly influences women’s work. Daughters-in-law are primarily responsible for domestic production and can share responsibilities when there are multiple daughters-in-law within the household. Apart from childcare, cooking is the main domestic task that must be done daily, whereas most other activities can be distributed throughout the week. In households with multiple daughters-in-law, women rotate who is in charge of cooking every 2 or 3 days; the person in charge of cooking on any given day is also responsible for procuring the necessary fuel. On the days when a woman is not responsible for meals, they can allocate time to other work, for example sweeping and collecting water. Not all tasks are shared amongst daughters-in-law living in the same household. For example, we spoke with a woman in Bilory whose household comprises her husband, his two brothers, the wife of one brother, and their children. She noted, “Each of us does our own laundry, and the laundry for our husbands and children. The woman who has only one child does the laundry for our mother-in-law. I do the laundry for my brother-in-law who is not married.” In general, though, women’s work is reduced the more daughters-in-law there are in the household. One middle-aged woman in Ndiobene Bagadji told us “in houses where there are only one or two co-wives, there’s a lot more work for women,” because there are fewer opportunities for work sharing.

Children’s time poverty may also be influenced by the demographic distribution of the household. In smaller households, where there are fewer siblings or older family members to share their workloads, children may be relied upon more for both domestic and production work. We interviewed a 16-year-old girl in Keur Taibe in a household comprised of her mother, father, three younger brothers and two sisters who reported experiencing a higher rate of time poverty than her mother. Since her mother worked at a local health center, and was often gone overnight, this girl was responsible for more of the domestic work in her household. In addition to commuting and spending time at school during the weekdays, and doing homework at night, she used what would otherwise be leisure time on domestic work (laundry, dish washing, meal preparation, childcare, and searching for water).

We also investigated the concept of time-use agency, defined as “an individual’s confidence and ability to make and act upon strategic choices about how to allocate one’s time” (Eissler et al., 2022, p. 1011). How much latitude do individuals have to determine which activities they do, and in what order, and do they have control over how they spend their leisure time? Do they have the authority to direct how other members spend their time? We found some general patterns, with the caveat that each household is different, conditioned by family culture and the relationships between family members.

Men have broad autonomy over their time, other than when it comes to farming the household millet field and with regards to the obligation to attend prayers at the mosque. Men also decide whether to contribute to feminized tasks; for example, the chef du village of Bilory told us “If men have the time, they might help the women deshell peanuts.” However, there are intrahousehold inequalities in time-use agency between men. There is typically a senior man in the household who directs the labor of the other adult men, usually his brothers, in his family. In the rainy season, for example, it’s the chef du ménage who decides when it is time to go to the fields, and who should go. Family members work on his field first, then on the others (oldest first, down to the youngest, regardless of the gender of the owner).

In Benin, Nigeria and Malawi, Eissler et al. (2022, p. 1025) found that “women shared some control over deciding when and how to spend their time on normative and expected tasks and responsibilities, but men controlled the decision making on all tasks beyond such activities.” This is similar to what we found in Kaolack, although – as long as they had finished their domestic work – women seemed to have autonomy around the businesses they operate and how they spend leisure time. However, women in Ndiobene Bagadji also described that caring for their husbands took priority over other tasks: “if my husband wants something, I have to stop what I’m doing and do it for him. Before I can do my other work I have to search for water for him, put out his clean clothes, give him food, wash his clothes.”

We found that, as with men, there is a social hierarchy between female household members that influences inequities in time use and time-use agency. In households with multiple daughters-in-law, the senior one directs some of the labor of the other daughters-in-law. For example, in a household with four daughters-in-law in Bilory (each married to a different brother), we were told: “The oldest belle-fille here takes a bit more responsibility than the others. She’s the oldest and has been in the family the longest. She decides what will be cooked every day. Her husband gives money to his wife every day and she distributes it to the others.”

Mothers-in-laws told us they manage their own decisions, for example related to small businesses, and do not intervene in the direction of the daughters-in-law’ work. In the words of one 67 year old mother-in-law in Bilory: “It’s the daughters-in-law who decide what to do, and what to prepare for the meals, they just bring me food to eat.” However, daughters-in-law in Bilory also told us that they will only ask their mothers-in-law for assistance with their babies if they are getting the cooking fire ready and the smoke is unsafe for the child. Women in Keur Taibe described how, if they fell sick, their mother-in-law could step in to cook or do other work on their behalf; however, out of respect, they would not ask her directly: “Every morning you have to say hello to your mother-in-law, if you do not she will come to your house to find out why you did not say hi, when she sees you she will see that you are sick and then she will offer to help so you can rest.”

Children, unsurprisingly, have the least time use agency. Mothers direct their daughters to do tasks such as cooking, laundry and childcare. They also direct children of both sexes to collect water and fuel. Boys are directed by older men in the household, particularly the chef du ménage. While other adult members may direct the work of their nieces and nephews, parents have more control over their own children. Children can also be asked to do tasks by anyone in the village; while this is not per se an employer-employee relationship, the neighbor or extended family member might give them a gift or some money in exchange for their help.

As Johnston et al. (2015, p. 4) note, it is essential “to take into consideration the household’s developmental cycle and how it may shape women’s use of time over time.” Our research in Kaolack indeed found that women’s and men’s roles and work responsibilities are not stagnant but change over the life course. It is not necessarily age that governs differences in time use and time poverty over time (except in the childhood/pre-marital stage), but by role in the household and relationships with other household members.

One study found children spend, on average, 4–6 h per day on reproductive and productive tasks (Sow, 2010).

Boys start contributing productive labor to the household around 7–10 years of age. Indeed, an 18 year old from Keur Taibe told us: “At the age of 10, I considered myself to be a young man. There are some advantages and inconveniences to this: my work increased very rapidly, but I had the advantage of going to school. I became more mature, so I see things more clearly-I can take some decisions for myself.” Concerning domestic production, boys of this age can be sent to the market, collect and carry water in small quantities, and pour and pass tea to family members. With respect to non-domestic work, they begin riding horses, passing equipment to workers in the fields, helping to direct draught labor during planting, watching livestock during the dry season, and distributing water to livestock. Around the age of 12, boys begin to play a more significant role in land preparation, typically with the aid of animals. Boys around 15 years old start using machines in the field.

Girls likewise start making significant contributions to household work around 8 or 9: at that age, they can sweep, wash dishes, and fetch water in buckets; they also help with childcare for younger children. Around 10, girls start to learn how to cook and at 15 years old they could become fully responsible for cooking. Girls aged 12–15 and older would also take care of the children if their mothers had to go somewhere else. Girls as young as 6 might assist in chores such as sweeping and washing dishes.

In Keur Taibe and Ndiobene Bagadji, people mentioned concerns related to the security situation and fear of children being kidnapped, which restricts the distance children are allowed to go in search of food, water and fuel: “This issue is a big problem for us. It creates a lot more work for parents if you cannot let kids go off on their own to get wood and animal fodder” (woman in Ndiobene Bagadji).

In their study of time use and gender in Africa, Dinkelman and Ngai (2022, p. 77) note that “[m]ore evidence would be extremely useful in shedding light on how households cope with the arrival of young children.”

In Kaolack, we found that women’s domestic tasks generally remain the same during pregnancy. This aligns with what prior research has found in other rural parts of Africa, Asia, and Latin America (Peterman et al., 2013). Rarely, women will be advised by a doctor to rest, in which case they will abstain from work in the home and fields. Women also reported that, in the third trimester, it can be too difficult to pull weeds or gather fuel. But for the most part, women will only stop working – especially within the home – when they begin labor contractions. We did find some evidence that pregnancy - in interaction with local infrastructure – can interfere with girls’ education. For example, an 18-year-old girl with a 7-month-old in Keur Taibe told us she stopped studying when she was 7 months pregnant because it became too difficult to walk the 4 km to school.

After having a baby, women ideally rest for 40 days, during which their only required task is to wash their baby’s clothes, if there is another woman in the house who can take over her work. Otherwise, they only rest for a week and the mother-in-law or other children would help. Women in Ndiobene Bagadji also noted that, during the rainy season and harvest, post-partum women will take less time off. When babies are 3 months old, they can be left at home with someone while the mother goes to the field or the market; but the baby has to be at least a year old for their mother to go to the fields during the rainy season. Some women said they carry babies under two on their backs when they leave the house for various activities. Since many women will co-breastfeed, if there’s another lactating mother in the household or carré, this can free time for the other woman to conduct other activities. In Keur Taibe, a woman told us “It’s hard to combine taking care of the baby and domestic work. We can work quickly while the baby sleeps, but sometimes we do not have enough time for everything. The priorities would be: cooking, children, cleaning and laundry. But if we do not have enough time we’ll leave the sweeping and the baby’s laundry.”

Men reported no differences in time use as a result of their wives’ pregnancies or the arrival of newborns and very young children. Most women told us men will occasionally hold or watch the baby, but do little childcare beyond this.

As children age, their parents’ workload changes. For example, as the mother of a 15 year old girl in Bilory describes, “I have a daughter who helps me, but she goes to school so she can only help on Saturdays and Sundays. On those days, she does pretty much everything.” Another woman in Ndiobene Bagadji notes, “By the time girls turn 15, the mothers go into retirement-girls need to learn how to cook and become independent and responsible.” A father in Ndiobene Bagadji likewise says “I have two major busy periods: weeding and harvest. I do not have that many laborers. That will change when my kids get older; my tasks will diminish. It’ll be the same thing for my wife when our kids get older and especially when they get married.”

Women move from their parent’s household to live with their husband and his extended family after marriage. At this point, they go from helping their mothers to being fully responsible for certain domestic tasks. Whether this initially leads to more or less work, would likely depend on the household sizes and compositions.

The most significant impact of a son’s marriage is on his mother, whose work drastically reduces. We asked two co-wives in Bilory if their lives changed when one of their sons married and brought his wife home. They responded, “yes, now we do not have to do the washing or the cooking.” Another mother-in-law told us that, in the dry season, all she has to do is shell and sort peanuts, and a middle-aged woman in Ndiobene Bagadji reported “if the workload becomes too much, a woman could ask her husband to take another wife; if he does not have the means, then you have to wait until the children grow up and you get a belle-fille!”

Widowed women may have more work in the fields than those with surviving husbands. We spoke with a widow in Bilory living in a household comprised of her co-wife, three sons, a daughter-in-law, and 7 grandchildren. As she describes, “when my husband died, I was obliged to take care of the household. I have to go to the fields, because there is not any other work. My co-wife and the small children stay home, and my daughter-in-law and two of my sons come to the field with me. My daughter-in-law comes back during the afternoon to make lunch. She does all the cooking but the 10-year-old girl helps her.” Depending on the composition of the household and the availability of off-farm work, widows may also engage in more market work. Another widow in Bilory told us: “Because my husband died early, I had to start these businesses to take care of the family.”

Men’s workload does not seem to change significantly after marriage.

Elderly men and women will retire from productive work if they can. A 41-year-old man in Keur Taibe told us: “In households where the chef is old, he’ll have daughters-in-law and his wife does not cook..” Likewise, his 57-year-old neighbor mentioned: “Men start to retire when their sons become older. The children will support you-working in the fields. All you have to do is make decisions and surveil what’s going on. The sons take care of all of the expenses.”

Elderly men with sons and grandsons do little work, beyond preparing tea. Elderly women with daughters-in-law may have more work than their male counterparts, although much less than during their younger years. A 67 year old mother-in-law in Bilory reported, “If there aren’t any peanuts, I just rest. Otherwise, I’m busy shelling the peanuts. When everyone goes to the fields, I take care of the children. It’s difficult to do, because there are a lot of children! I take care of the children under 6 years of age. The kids under a year go to the field with their parents. I go to the mosque every day except when I’m sick.” Again, though, elderly women’s time use is contingent on the presence of adult women; if they do not have daughters-in-law, they remain responsible for domestic work.

Finally, we probed the impact of sickness and disability on time use. When there is an illness or disability shock in the household, the burden of care work falls on women and can reduce agricultural productivity and food security, unless men share in the care burden (Ilahi, 2000; Arora and Rada, 2017). However, men are also impacted. “If a family member falls sick, it creates problems for everyone” (men’s focus group in Bilory).

We observe a strong substitution effect here (Ilahi, 2000). A chef du ménage in Bilory noted that, if he were too ill to work, the other men’s workload in the household would increase as a result. We asked men which household members would cause them the most difficulty if they fell sick. They all responded that it would be the other men that contribute to their shared work. For example, “the worst would be if my brothers fell sick-they are the ones who do all the work” (63 year old chef du ménage); “for me, the worst people to get sick are the men who hold the machines, and the one who pulls the horse” (62-year-old chef du village). If the chef du ménage fell ill, we were told that his younger brother would take charge. “The chef could still command the household from his sickbed-the rest of the brothers would just need to work harder.”

If a daughter-in-law falls sick, the others will share her work. If there is no daughter-in-law, children or neighbors would help. A woman in a small household in Bilory, comprised of only her husband and two children under 12, said “If I got sick and could not work, the neighbors would help me, or my daughter would skip school.” A middle-aged woman in Keur Taibe with no other adult women in the household echoed this sentiment: “The imam is my uncle. If I got sick, they’d let me borrow a teenager to help out with things. Also, the boys would look for food and water. The girl would help with washing and sweeping-she’s 12 now.” It would be most difficult if the woman responsible for cooking woke up sick that day, because the others would have to prepare food in addition to the other work they had planned that day. A woman in Bilory told us she would have the children cook first and, if they were also sick, then the mother-in-law would do it. Everyone agreed the worse time to get sick would be in the rainy season. Women specifically noted that the weeding period would be a particularly unfortunate time for another woman to be ill.

We also observe a care effect, wherein family members allocate more time to caring for sick individuals (Ilahi, 2000). This can include men, who accompany women to health clinics. The chef du village in Bilory told us: “There’s no health post here - the closest one is 5 km away. If a chef du ménage gets sick, the adult son would take him, or maybe his brother or neighbor would take him. If a woman got sick, her husband would take her. If a kid gets sick, it would either be the father or the mother.”

While disabled people may be less time-poor because they face difficulties conducting paid or unpaid work (Bardasi and Wodon, 2010), we found that chronic disability leads to an increase in workload and higher likelihood of time poverty for others in the household. One man in Keur Taibe, who had lost the use of his right hand and only has small children and one wife in his household, relies on neighbors and friends to help him with cultivation. A woman in Ndiobene Bagadji said that, because of her husband’s frailty, she goes with her children to farm.

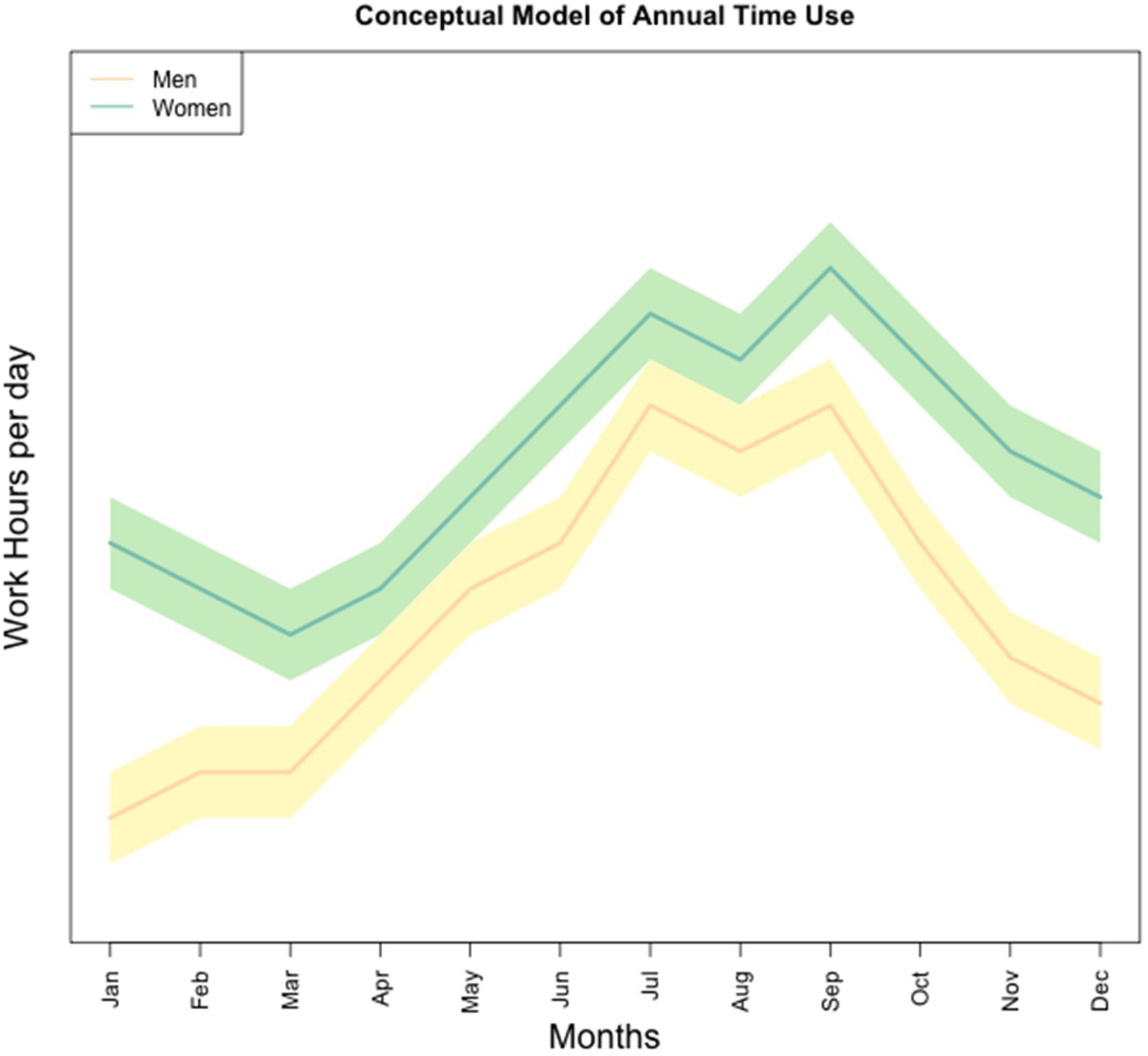

Seasonality is known to impact gendered time use (Kes and Swaminathan, 2006; Adeyeye et al., 2021). All respondents agreed that the rainy season (June to September) is the busiest time of the year. However, men still report having leisure time during this period.

Women have to balance their ordinary reproductive tasks and increased productive responsibilities on the farm, including weeding and harvesting. “During the rainy season, the ones who do not have to cook go to the fields. The other one stays behind to cook, do dishes and sweep, and brings breakfast to workers in the fields. Most women have to go work in the fields during the rains, except the one who is cooking alone, and the mother-in-law who can watch over children.” Women and children also have more work shelling peanuts immediately after harvest. A woman in Ndiobene Bagadji noted that, if the harvest is bad “our [women’s] activities will decrease because we have fewer peanuts to shell. But our food will decrease as well, so my husband would probably go to get money elsewhere.”

In addition, domestic work becomes more time-consuming, both because of environmental conditions and an increase in household size during this critical agricultural period. Laundry is more difficult for a number of reasons. Clothes get muddy and, if the laundry gets wet again, it has to be redone. In addition, there is significant circular migration in and out of Kaolack. Men, and some women and girls over the age of 15, leave during the dry season to find wage work, returning to assist with agriculture in June or July. As a result, the amount of laundry increases. Women also mentioned that returning men often wear blue jeans, which take longer to wash and dry. Cooking becomes a more lengthy process, both because of the increase in household size, and because it takes longer to find fuel: cow dung has melted into the earth, and wood is wet. Water from taps located in or near the homestead is often salty during the rainy season, so water must be collected from the well, which takes extra time.

When it’s raining, younger children are kept at home to avoid illness. In larger families, one mother-in-law cannot watch them alone, in which case the mother will also stay back to provide childcare. Women reported some interaction between seasonality and time use in the post-partum period: “whether a woman has a baby in the dry or rainy season affects whether she will be able to rest and stay home with the baby or if she has to go work in the fields.” Teenagers also noted not having time to play during the rainy season, and some will leave school entirely, or come home early in order to help with productive and reproductive work.

Men also universally report the rainy season as the busiest time of the year, although a 23 year old from Ndiobene Bagadji told us “There’s a period of the year where you do not have much work to do-because there’s too much rain-this is usually in August.” and teenage girls in Keur Taibe note that “the men here do have free time in the rainy season.” For the most part, the first 2 months of the dry season (land prep and planting) are busy for men, along with the harvest period. Harvest can lead to time constraints because, after January 15th, goats and cows are legally permitted to roam: “The time issue is pressing. If you do not finish on time, the animals will come and eat what’s in your field” (63-year-old chef du ménage, Bilory). Weather events can also lead to time constraints for those involved in agricultural labor. For example, flooding in Bilory, followed by drought, meant fields had to be re-planted twice. Further, men told us that, because soil is less fertile now and there is not enough rain, which they linked to deforestation, they now have to use fertilizer which extends the time required for planting.

Women’s domestic work during the dry season is comparably less demanding, primarily due to male out-migration. In Kaolack, many men go to Gambia for the cashew harvest, and to find wage work in Dakar, Mauritania and Libya, while some women out-migrate to Dakar to work as maids. They return for the rainy season and for ceremonies like Tabasky.

Daughters-in-law reported that, when family members migrate, they have less cooking and laundry work. However, water collection remains time-consuming and tedious during the dry season, albeit for different reasons. Tap water tends to go out, returning after 8 or even 10 at night. Hence, people have to wait until it comes back on to fill up their bidons so they have water for dishes, and for their horticulture plots. As a man in Ndiobene Bagadji described: “We do not have water until 10 pm a lot of the time. Sometimes my wife is tired, and she cannot fill the basins in the middle of the night. So my wife will go to the well with the other women in the village.” Some men reported giving up horticulture due to lack of water. Dung is easier to find during the dry season, but dust storms make it unpleasant to be outside so people have to stop tasks and wait until the atmosphere clears. Heat also causes headaches, which leads to work stops.

It’s the opposite for mother-in-laws, however: their work increases when the men leave. They have to take care of the food and water for the animals. The same is true for boys: they have to clean the livestock barns, and give food and water to the animals. Around March, livestock is no longer permitted to roam, which increases men - and especially boys - workload in terms of watching the herd.

By contrast, men remaining in the village feel little time poverty during the dry season. As an 18 year old from Ndiobene Bagadji put it: “During the dry season there is nothing to do but take the animals to drink and eat.” Teenagers in Keur Taibe said that “During the dry season [men] just do gardens, and have a lot of free time.” A 46-year-old Soce man from the same village described his typical day during the dry season as: “drinking tea, talking, going on a walk (faire promenade), eating, sleeping, and listening to the news. Sometimes kids come in and play, but its not my place to take care of babies or children. There is nothing to do until close to the rainy season.”

Finally, we found evidence that aspects of the physical landscape influence what types of activities people engage in, how long it takes to complete tasks, and how they are staggered. For example, Bilory is close to a river, enabling both men and women to engage in fishing-related activities and enterprises. Deforestation is a serious problem in Kaolack, driven by expansion of agricultural land and population pressure on wood collection for cooking fuel. To combat deforestation, the Government of Senegal has protected forests, including the one outside Bilory. This means that women cannot use it for fuelwood collection, and instead collect animal dung, which reportedly can take up to 2 h to collect per cooking day. As a result, fuelwood prices are increasing and collection is becoming even more time-consuming, especially in the Groundnut Basin. One study found the aggregate time all household members spend on firewood collection is 14.5 h per week (Bensch and Peters, 2015).

The presence, reliability, and distance to infrastructure also influence time use. Water taps have reduced collection times for women in Ndiobene Bagadji although, as noted above, they often do not work until late at night during the dry season. While there are wells, some are decades old and produce only dirty, salty water. As described earlier, the distance to health centers and hospitals impacts how much time it takes people to access health care. In Ndiobene Bagadji, the health center is only a kilometer away and can easily be reached on foot, while in Bilory the nearest center is five kilometers away and usually requires accessing a charette for transport.

Our research adds to the growing body of literature that shows rural women in the majorityworld are dual-burdened by their responsibilities for productive and reproductive work. Reflecting findings from other studies of rural Africa (e.g., Johnston et al., 2018), women in Kaolack play a critical role in agriculture. This includes providing the care work necessary to support family members engaged in agricultural work and labor for production. Women and older girls further play an important role in weeding and peanut harvesting and are largely responsible for the time-consuming and often painful task of post-harvest peanut sorting and shelling. Indeed, in her study of time use in Kaolack, Sow (2010) found women devote more time than their husbands to peanut cultivation (3.5 h/day compared to 3.2) but receive little of the income.

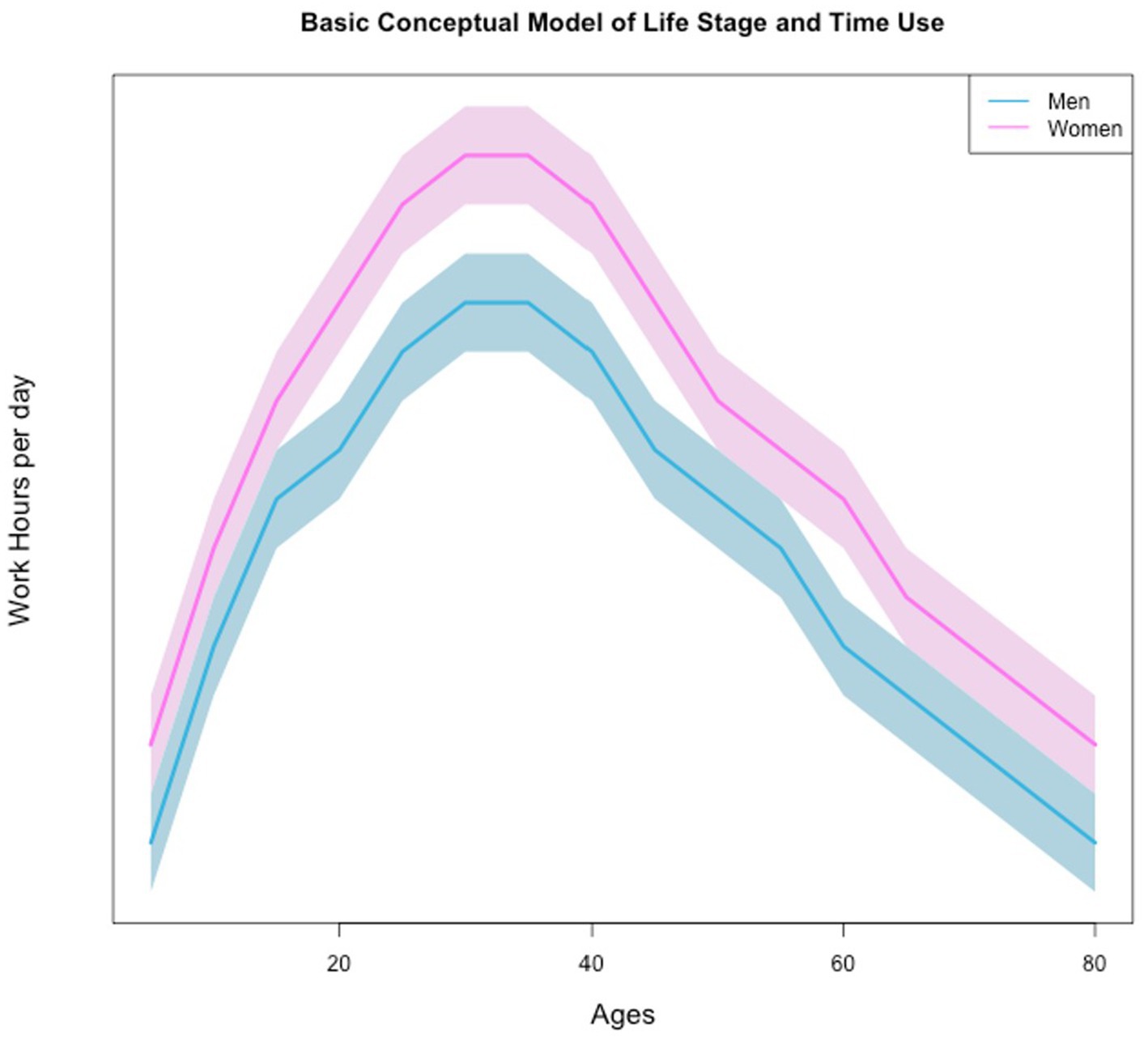

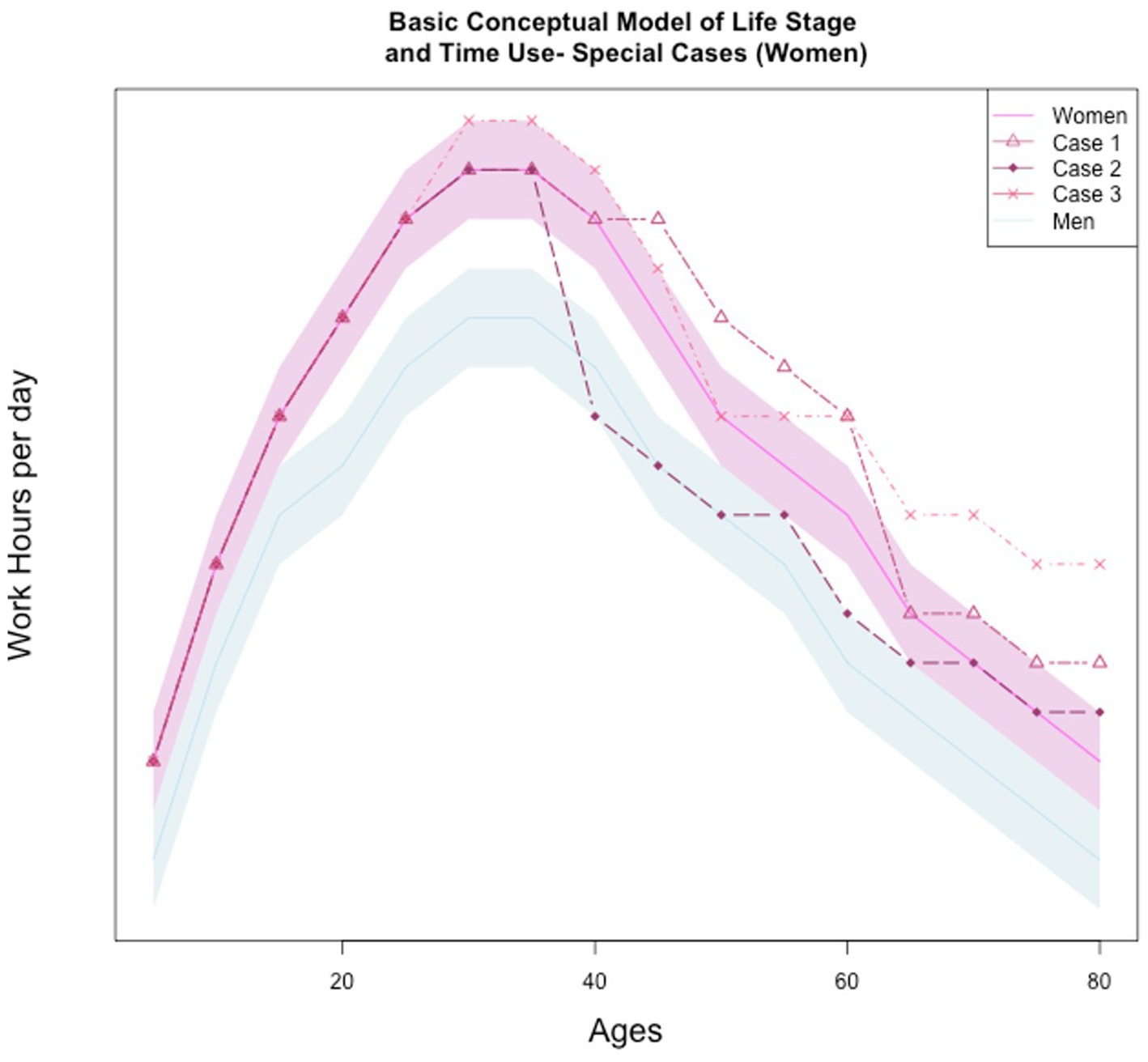

This double burden means women in rural Kaolack are, in general, more time-poor than men across the life course and consequently have less time for sleep, leisure, and engagement in wage-earning work (Figure 3). When women have free time, they reportedly spend it first on additional care work (e.g., braiding hair, cooking more elaborate meals, or increasing stocks of fuel and water), and then on leisure. To a lesser extent, and typically only for women in the mother-in-law role or with unmarried daughters over the age of 15 or 16, women in Kaolack spend free time on income-generating activities. This aligns with what Sow (2010) found: when women are significantly burdened by housework, they are less likely to engage in off-farm income-generating work, or can only do so at the expense of their own – or other women and children’s – rest and leisure time. Men who are not experiencing time poverty also spend their surplus time on leisure and market work, but they still have more hours to dedicate to relaxation and sleep, larger activity spaces, and more diverse and profitable income-generating opportunities. Tables 3, 4 illustrate stylized daily time use schedules in the rainy and dry seasons for individuals belonging to different sex-age-role categories, based on real examples from our interviews.

Figure 3. Conceptual model of gendered time use over the life course This conceptual model shows how time use changes over women’s and men’s life stages. In this model, the peak age of high time poverty (intensive time use) is in one’s late 20s through 40s, to reflect the age during which the person has heavy responsibilities with few options for delegation. However, once a family’s children begins to reach an age where they can take on heavier responsibilities, or in specific son’s can marry a spouse, the time use for the men and women decrease. It should be noted in this conceptual model that although both men and women experience high time demands, men’s time demands are less than that of women’s.

Work intensity – often defined as energy expenditure – is overlooked in the literature (Stevano et al., 2019). In Kaolack, men’s work in agriculture and animal husbandry is physically demanding, a fact reported frequently by our participants. However, they contribute relatively little to the domestic work of childcare, cooking, cleaning, and energy provision. This frees their time for wage-earning work, leisure, and social interaction. Further, women are also involved in energetically taxing work in the fields, pounding millet, and collecting and carrying fuelwood and water, sometimes with children on their backs; but they have little time for rest in between. Additionally, women’s work is often simultaneous, which is considered more stressful and tiring (Arora, 2015; Arora and Rada, 2017; Seymour et al., 2020).

Yet sex alone does not explain intra-and inter-household differences in time use and time poverty in Kaolack; many other variables interact to produce the observed inequities.

Age conditions individuals’ time use in our study households (Figure 3). As Posel and Grapsa (2017) note in South Africa, “the division of labor in multi-generational households is bisected by gender and age.” As a general rule, elders in Kaolack exhibit the lowest levels of time poverty. This supports research from several countries in Africa, which find elderly men and women are less likely to be time poor (Lawson, 2008; Bardasi and Wodon, 2010; Arora, 2015; Posel and Grapsa, 2017; Charmes, 2019). Older chefs du ménage in Kaolack rely on their sons and younger brothers to conduct agricultural work, and are consequently able to retire from productive labor. They spend the overwhelming majority of their time on leisure and personal care activities and managerial tasks. For the most part, elder mother-in-laws are likewise in retirement from productive and reproductive work. This echoes findings from Lesotho (Lawson, 2008). There, too, men and women over the age of 65 spend most of their time on personal care; elderly men spend a bit more time on production work while elderly women spend more on household maintenance. However, the Lesotho study found that neither group spends much time on caring activities, while our research in Kaolack suggests that elderly mothers-in-law often play a critical role in childcare, especially in the rainy season.