- Institute of Sociology, Mountain Agriculture Research Unit, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria

The disembedding nature of globalization is being tackled by integrated and territorial approaches that focus on local contexts and include multiple actors and sectors. One example are biodistricts that rely on values of organic agriculture to strengthen territorial agro-food systems. The remote rural mountain valley of Valposchiavo, Switzerland, follows such a territorial approach and is subject of this case study. In this article we aim to understand in detail the processes of territorial development strategies in Valposchiavo. To shed light on the development approach, we used the theoretical concept of neo-endogenous development by Ray. We conducted document analysis, secondary interview analysis as well as problem-centered interviews. The results indicate that the rural development approach follows a neo-endogenous development that renews rural–urban linkages by developing internal and external networks. The creation of a territorial brand and a regional development project contribute to the establishment of local and organic agro-food supply chains. The territorial development approach in Valposchiavo demonstrates how remote mountain areas can shape the well-being of their community and tackle negative impacts of globalization.

1. Introduction

One strategy adopted to cope with the impacts of globalization is for rural areas to adapt and initiate their pathways to ensure the well-being of their communities (Clement, 2005). More recently these initiatives have started to choose integrated and territorial approaches aimed at including many actors in a region, based on the entire territorial development concept, which makes an entire territory in all its diversity the object of interest instead of highlighting certain sectoral aspects (Ray, 2001; Böcher, 2009). One example of these integrated territorial approaches is the recently established approach of biodistricts in Europe. They can be understood as territories that rely on the principles and values of organic agriculture to guide regional sustainable development (Schermer, 2005; Stotten et al., 2018; Guareschi et al., 2020; Dias et al., 2021).

One region that follows such an approach is the Valposchiavo, a remote rural mountain valley in Switzerland, where the population has created various initiatives and strategies that contribute to the socio-economic well-being of the region (Semadeni et al., 1994; Luminati and Rinallo, 2021). At over 83% (BfS, 2021b), the region has the highest percentage of organic agriculture in Switzerland, a crucial part of the territorial development. Strong synergies in short agro-food supply chains create further territorial added value through the food brand 100% Valposchiavo (Ermann et al., 2018). In 2012, local actors formulated the development strategy Smart Bio Valley with a vision to become a certified biodistrict in the future (Luminati and Rinallo, 2021).

This article aims to considerate how a holistic understanding of organic agriculture as a locally adapted strategy of territorial development became normative in the region. In detail, we investigate the structure and dynamics of the biodistrict as it becomes established, as well as its values, practices, and managerial challenges. Further, we reveal structures and stakeholder networks in the valley that have led to instrumental and normative ends for this territorial development approach. To do so, we shed light on the development pathways through the lens of neo-endogenous development as proposed by Ray (2001, 2006). In this concept, development focuses on territorial areas and is based on local resources by highlighting their specific value in a bottom-up approach. Central in the understanding of rural development for Ray (2001) are the cultural characteristics of a region. They serve as a starting point for the projects and actions and are called cultural markers.

1.1. Regional development and biodistricts

Globalization in the context of regions, rural areas, and regional development is seen as a process of complex and multidimensional dynamics (Woods, 2007; O Riain, 2011). Regions and rural areas get integrated into global market processes because global economies tend to also capture local and regional spaces for capital accumulation. These complex realities of globalization processes at regional and rural levels are termed globalized countryside (Woods, 2007). It describes the interconnectivity and influences of a globalization logic on regional (as well as rural and mountainous) spaces. However, the impacts of globalization on regional and rural areas and its relations with these areas are complex and uneven and depend on historical and spatial developments (O Riain, 2011). In the past, regional and rural areas were mostly based on farming for food production. Even if farming activities have generally decreased (Ward and Brown, 2009), it still contributes to the viability of rural areas (van der Ploeg, 2005), especially in mountain areas (Ermann et al., 2018).

In the understanding of the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM) organic agriculture is defined “as a “production system that sustains the health of soils, ecosystems, and people. It relies on ecological processes, biodiversity, and cycles adapted to local conditions, rather than the use of inputs with adverse effects. Organic Agriculture combines tradition, innovation, and science to benefit the shared environment and promote fair relationships and good quality of life for all involved” (IFOAM, 2008). This definition includes aspects of farming beyond simple technical ones (Freyer et al., 2016; Guareschi et al., 2020) and integrates diverse values and processes along the entire agrifood supply chains (Stotten et al., 2018). In addition, it aims to create strong relationships between producers and consumers by looking at agrifood products, the production process, and the benefits of the agricultural system (Arbenz et al., 2017). In practice, enacting these values does not mean a legal obligation to farm organically. However, this holistic understanding of organic agriculture is thought to enhance rural and regional development as it focuses on local resources, strengthens local supply chains, and provides ecosystem services (Darnhofer, 2005; Lobley et al., 2009). Further direct outcomes of organic agriculture can be the creation of jobs in remote areas and environmental services that boost the tourism sector (Stotten et al., 2021, p. 124).

In regional development, the spatial clustering of organic farming in a certain territory serves to establish so-called biodistricts (also called organic regions, organic districts, bio regions, eco districts or eco regions; Schermer, 2003; Groier et al., 2008; Stotten et al., 2018; Belliggiano et al., 2020). Within the EU Organic Action Plan these are defined as “a geographical area where farmers, the public, tourist operators, associations and public authorities enter into an agreement for the sustainable management of local resources, based on organic principles and practices” (EU Commission, 2021, p. 15). This characterization is broadly identical with the definition by the International Network of Eco-Regions (IN.NER) of 20141, except that it highlights agro-ecology specifically. In a more detailed characterization, Basile (2014), the president of the IN.NER, defines a biodistrict as [cited translated after Dias et al. (2021, p. 3)]:

“a non-administrative, but functional, geographical area, in which an alliance is established between farmers, citizens, tour operators, associations and public administrations, for the sustainable management of resources. This synergy takes place based on the biological principles and practices of production and consumption (short chain, organized groups of supply and demand, quality restoration, biological canteens). In the [biodistrict], the promotion of organic products is intrinsically linked to the promotion of the territory and its peculiarities, to achieve the full development of the economic, social, and cultural scope.”

This underlines further the linkages of local organic food products to the territory and a related promotion. Together they form a starting point for a cross-sectoral regional development to evolve (Groier et al., 2008). As a multi-stakeholder network (Dias et al., 2021), producers and processors bundle several supply chains and, together with actors from the social, cultural, and institutional sectors, work on a holistic development based organic agriculture (IN.NER, 2017; Belliggiano et al., 2020). Structurally, biodistricts are local production systems that rely mainly on organic agriculture integrated with economic, environmental, and socio-cultural domains in the region (Guareschi et al., 2020). Its structural strategic objectives include the internationalization, digitalization, and valorization of the agricultural, cultural, and environmental heritage (Dias et al., 2021).

Kirchengast et al. (2008) formulate five key criteria that encourage the development of biodistricts: a clear setting of territorial boundaries of the region, more organic farms in the region than the national average, no use of genetically modified substances, the development and implementation of an organizational structure for the biodistrict and the creation of a comprehensive regional concept/strategy. Historically, the first biodistrict evolved in Italy; the bio-distretto Cilento in southern Italy was established in 2009, and by 2019, 34 biodistricts had been set up (Guareschi et al., 2020). Today, there is a growing number of biodistricts, for instance, in France (Biovallée Drôme), Austria (Bioregion Mühlviertel), and Portugal (e.g., São Pedro do Sul Bio Região; Stotten et al., 2018; Guareschi et al., 2020; Dias et al., 2021). These approaches have been taken up by the European Union and are now integrated for promotion in the EU Action Plan (EU Commission, 2021) to (re)integrate local agro-food systems in the territory, aimed at improving the quality of life in rural communities. However, so far there is no official regulation for the governance of biodistricts and best practice models are missing. This often results in weak governance and promotion strategies, as well as low and instable levels of financial resources (Guareschi et al., 2020). As their logic follows Ray’s (2001) theoretical approach, biodistricts are seen as an example of neo-endogenous development (Schermer, 2003; Stotten et al., 2018).

1.2. Conceptual frame: neo-endogenous approaches

Theoretically, there are two types of regional development concepts: so-called core-periphery, top-down, exogenous concepts of regional development and bottom-up, endogenous ones (Lowe et al., 1998; Gkartzios and Lowe, 2019; Klimczuk and Klimczuk-Kochańska, 2019). The first type of concept distinguishes a ‘developed’, urban-industrialized, central core region from an ‘underdeveloped’, rural, often agricultural, and sometimes remote, periphery (Gkartzios and Lowe, 2019; Klimczuk and Klimczuk-Kochańska, 2019). Critics of this approach claim that it leads to a marginalization of the periphery (Willett and Lang, 2018; Gkartzios and Lowe, 2019) and that it overlooks the real complexity and interrelations (Klimczuk and Klimczuk-Kochańska, 2019). The opposing bottom-up or endogenous approaches deal with the complexities of regional diverse structural compositions and human capital (Gkartzios and Lowe, 2019). One approach of this bottom-up perspective is the endogenous rural development that later advanced into neo-endogenous rural development (Bock, 2016; Gkartzios and Lowe, 2019; Chatzichristos et al., 2021). These endogenous approaches explicitly consider various spatial scales. While the focus is on local and regional scales as spaces of agency, the external, larger scales, like national and global levels, are also taken into account. Endogenous development is seen as an integrated approach of socio-economic interdependencies and thus also focuses on ecological aspects and sustainable use of (natural) resources (Tödtling, 2011).

To overcome the theoretical dichotomy between exogenous and endogenous concepts, scholars suggested more realistic and hybrid models that also consider the influence of external pressures and actors (Gkartzios and Lowe, 2019). One example of this more hybrid thinking, where “rural development is locally rooted, but outward-looking” (Gkartzios and Lowe, 2019, p. 163), is the concept of neo-endogenous development proposed by Ray (2001). It explains regional/rural development as starting from local bottom-up initiatives, projects, and movements that improve the well-being of the community and the local territorial areas with the cooperation and support of extra-local external factors. The argument is based on the idea that interaction and collaboration of internal and external factors, people, and resources is the key to sustainable regional/rural development. In his concept, Ray (2001) mentions three crucial aspects of this approach. First, development should focus on territorial areas like certain regions instead of sectoral aspects of the local economy. Second, the regional development initiatives should be based on local resources by highlighting their specific value or revalorizing them, and third, it should focus—as a bottom-up approach—on the ideas, perspectives, and needs of the local population as the most important source of input. Cultural, environmental, and ‘community’ values in particular are the basis for actions. Recent debates (Neumeier, 2012; Bosworth et al., 2020; Vercher, 2022) underline the role of social innovation “as a motor of change rooted in social collaboration and social learning, the response to unmet social needs as a desirable outcome, and society as the arena in which change should take place” (Bock, 2016, p. 4). Referring to territorial development, it puts into center the social dimension of rural development (Vercher, 2022) that is however relying on the cooperation of internal and external networks to facilitate knowledge exchange and to gain new markets (Bosworth et al., 2020). Cultural characteristics of a region serve as a central starting point for the projects and actions. Ray (2001) draws on the cultural capital approach of Bourdieu (1986), who understands it as values and symbols in material (cultural goods) and non-material forms (knowledge, values). In turn, strong cultural capital within communities is seen as the key to community-driven action (Ray, 2001; Marango et al., 2021). This cultural capital of a region or territory is called cultural markers and might include culinary specialties, languages and dialects, crafts, historical sites, endemic flora and fauna, etc. These characteristics are used as resources to imprint their specific territorial values on the local economy. “This attempt by rural areas to localize economic control—to revalorise place through its cultural identity—has been called the cultural economy approach to development” (Ray, 2001, p. 20).

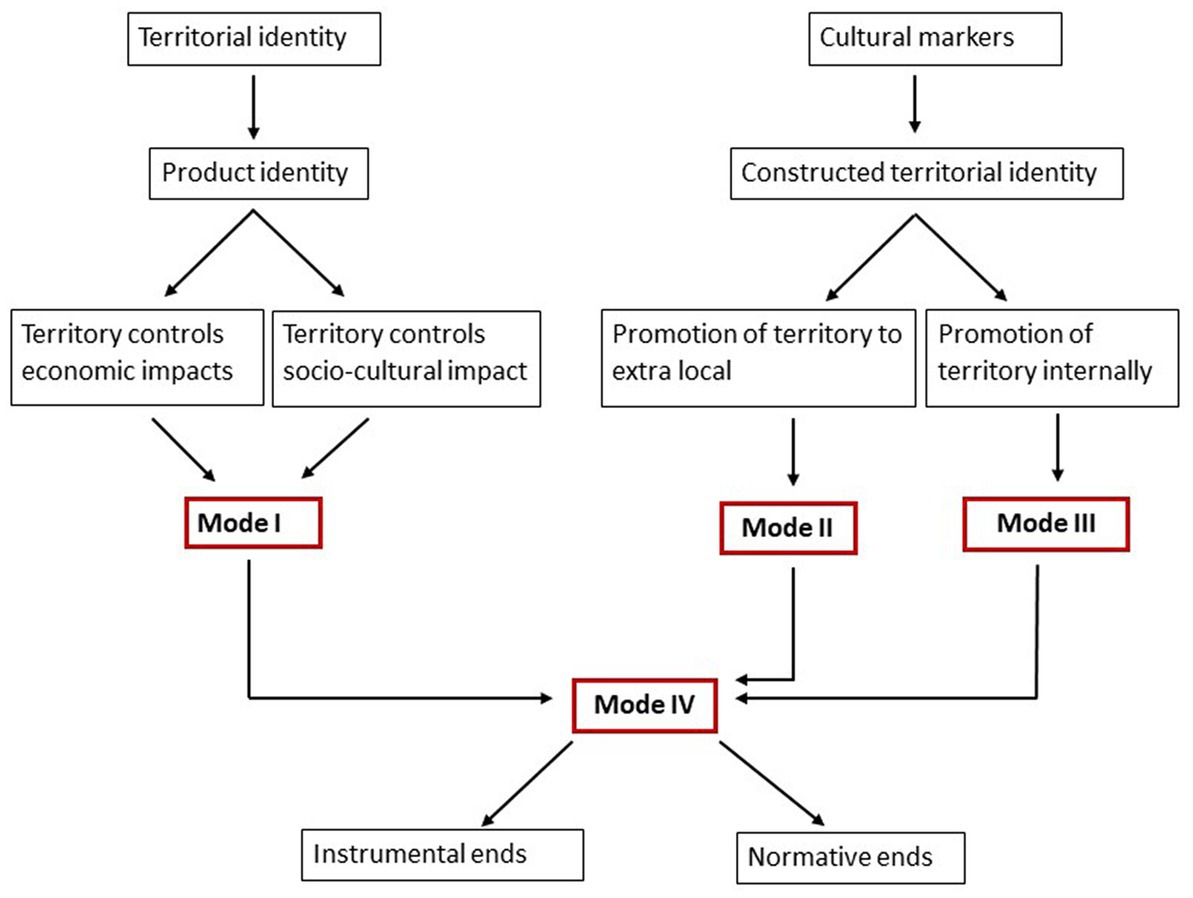

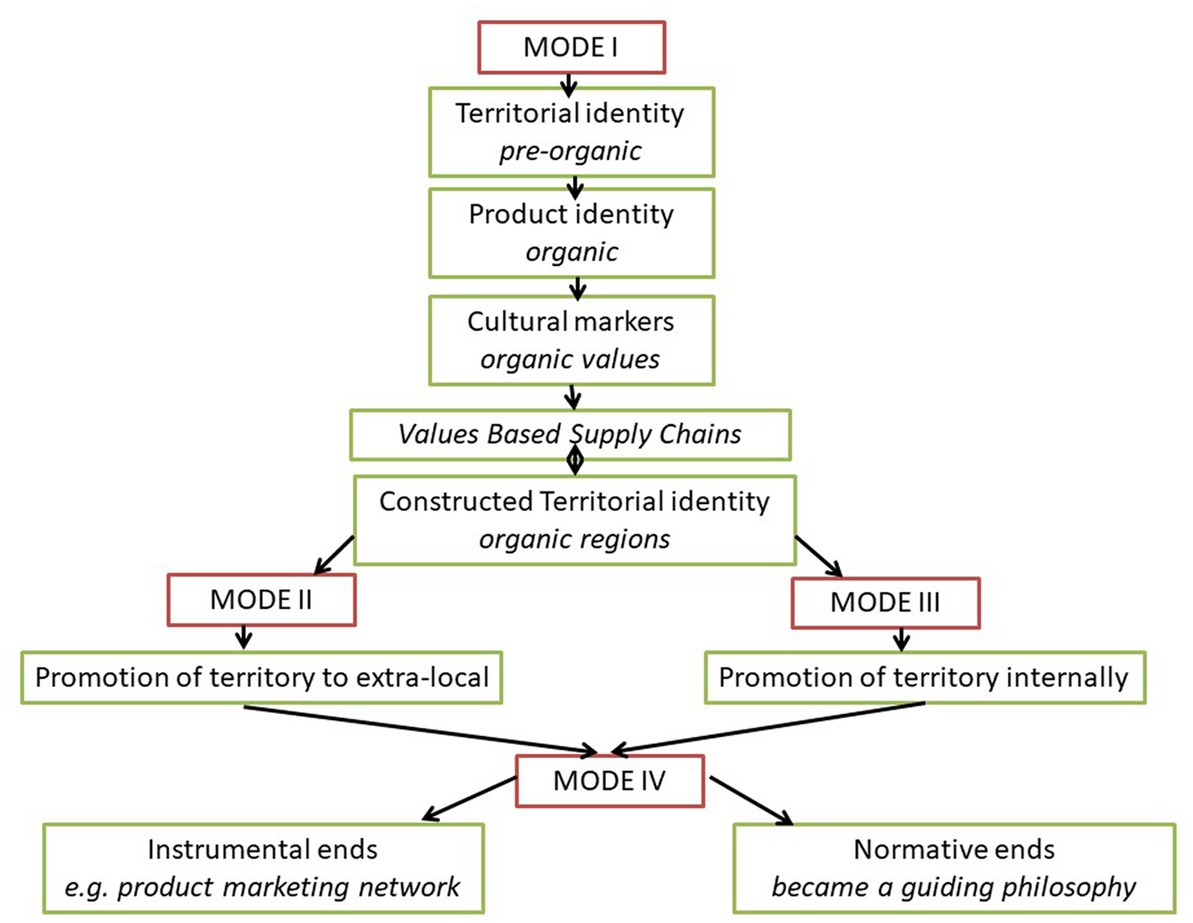

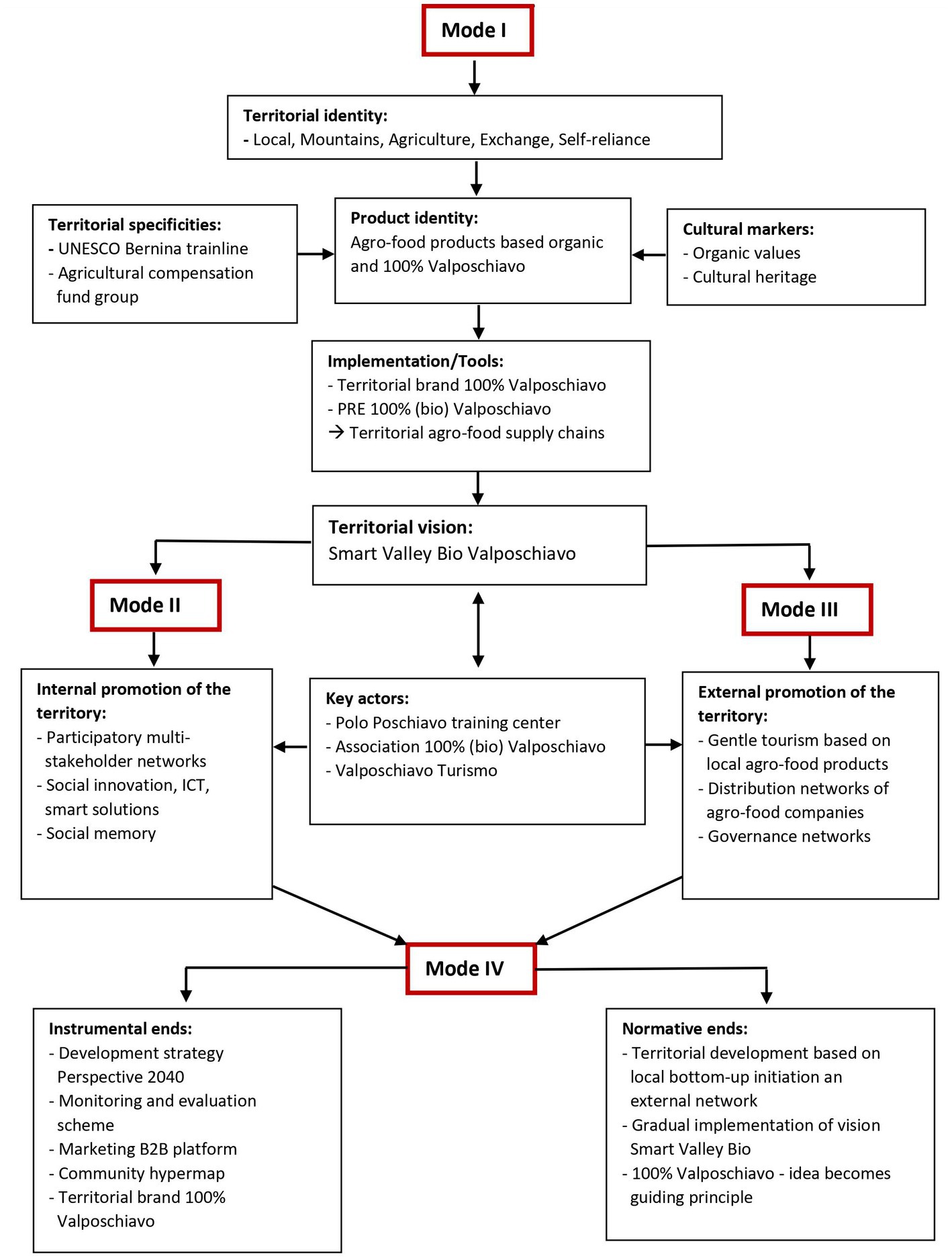

Ray (2001) presents his concept of a culture economy schematically with four modes (see Figure 1). Mode I describes the use of territorial values and identity as resources for marketing certain products. The added value of certain products stems from the specific territorial characteristics of an area which are inscribed in the individual products and used for marketing the region. Examples are regional agrifood products and regional cuisines. In terms of rural development, this means that the local cultural imprint in the products should foster the local economy. Mode II moves away from pure product identities and focuses on the construction of a territorial identity of the entire region to present outside. The cultural markers or cultural resources mentioned above serve to create a kind of corporate identity that the region can use for promoting the territory. The products (Mode I) are also part of this corporate identity. This is important, as it ensures the interaction of the local conditions with extra-local factors, for instance, funding, tourism purposes, etc. While Mode II focuses on the outside, Mode III does the opposite, and promotes a (new) territorial identity within the region to a variety of stakeholders. It targets the motivation of people to (re)-identify with the given cultural territorial characteristics of their region as something valuable that can foster the well-being of rural communities. People’s awareness of their local cultures also triggers “new economic opportunities, innovation and a socio-cultural vibrancy that counter economic vulnerability and traditional forces for emigration” (Ray, 2001, p. 25). Finally, Mode IV can be seen as a synthesis of the other modes, with the focus on the specific cultural territorial resources of a region to enable a distinct regional development strategy. The values that are expressed in the other modes become normative by applying them on a broader scale as a holistic strategy, which means that several stakeholders internalize the logic of the cultural territorial values (Stotten et al., 2018). To ensure the endogenous character of this development, resources are locally owned and the choices for certain developments are based on collective agency (Ray, 2001, p. 22). While the original concept sees the first three modes as happening simultaneously (see Figure 1), Stotten et al. (2018) have suggested an adapted order with the modes in sequence (see Figure 2). It sets out with the use of product identities (Mode I) that create a certain territorial identity, which is then promoted internally as well as externally (Modes II/III). Only on this basis does the strategic development path specific to a territory become enabled (Mode IV).

Figure 1. Model of neo-endogenous development by Ray, 2001, created by the authors.

Figure 2. Adapted model of neo-endogenous development after Stotten et al., 2018.

Empirically, the concept of neo-endogenous development has been applied for investigations in various contexts. For instance, Ray (2001) demonstrates the concept by investigating the LEADER regions in France and England. Bosworth et al. (2016) evaluate the neo-endogenous development in LEADER initiatives in England as a constant process of negotiating responsibilities and power relations between local and extra-local stakeholders and forces. Further, they emphasize that in practice often already powerful stakeholders also benefit in neo-endogenous development projects and that problems around participation and elitism can occur. In a comparative study of European rural areas, Chatzichristos et al. (2021) state that interregional networking and social innovations in governance are key aspects. In the context of local nature conservation initiatives in England, Marango et al. (2021) point out that the neo-endogenous development approach serves to understand community-led local initiatives within multi-level governance structures. In agriculture, the concept of neo-endogenous development has been applied to investigate areas focusing on organic agriculture as a collective basis for territorial development, with case studies from various European (mountain) regions (Stotten et al., 2018; Belliggiano et al., 2020).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Case study area

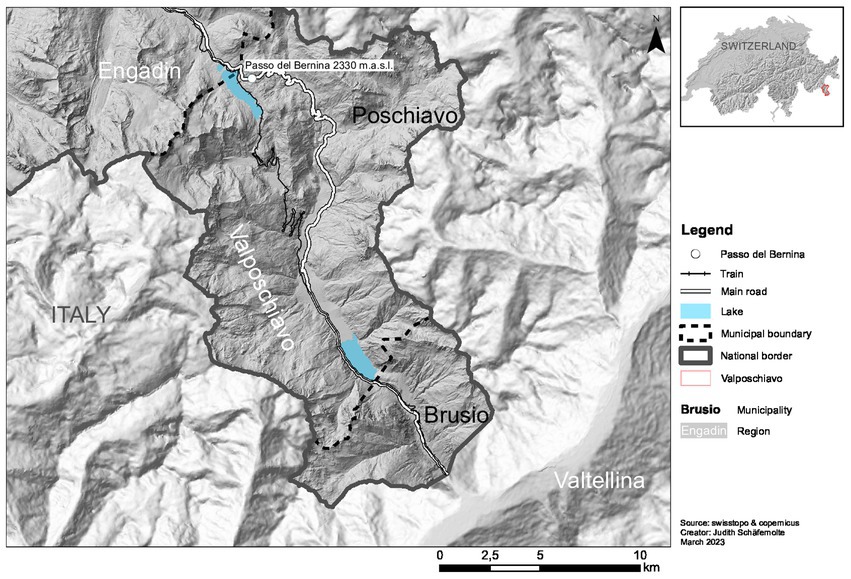

Valposchiavo is situated in the southern part of Switzerland in the canton Grisons (see Figure 3). In the north, it is physically separated from the rest of Switzerland (Engadin) by the Bernina mountain pass (2,328 m.a.s.l.). In the south, it borders on the Italian region of Lombardy. The valley consists of the two communities Poschiavo and Brusio. Together they form the political district of Regione Bernina (see Figure 3). It is 25 km long and its width ranges from 6 to 16 km (Lentz, 1990). The diverse landscape ranges from high alpine terrain of mountains over 3,000 m.a.s.l, in the east and west to the lowest point of Campocologno (553 m.a.s.l.; Lentz, 1990; Semadeni et al., 1994). Climatically, the valley is influenced by its geographic location in the Southern Alps and its physical separation by the Bernina pass. There is a gradient of the temperatures as well as precipitation from the Bernina pass down the valley. Except for the high alpine area around the Bernina pass, a relatively mild climate is predominant, and often a strong northerly wind down the valley leads to drought periods (Semadeni et al., 1994). The diverse topography creates microclimates that allow for diverse farming systems (Lentz, 1990).

Historically, the valley has a long and varied history largely shaped by its geographical location in the border region with Italy and it was also settled from the south. Territorial control over the Valposchiavo changed several times between Italian and Swiss rule (Semadeni et al., 1994). The Bernina pass has been used for transit and transportation since the Middle Ages and a pass road was built in the mid-19th century. Since 1910 a railway connects the Engadina and the Valtellina (Italy) across Valposchiavo (Tognina and Zala, 1953). Demographically, the population increased around 1900 due to the construction of the hydropower plants and the Bernina train line. Since the 1950s there has been continuous and strong outmigration from Swiss mountain valleys like Valposchiavo (Lentz, 1990; BfS, 2021a). After 1990, the population decreased slightly and is around 4,600 today (Stettler, 2021; BfS, 2021a). The official language of Regione Bernina is Italian (Regione Bernina, 2016), which is the main language for over 90% of the population (Semadeni et al., 1994). Further languages are German and the local dialect pusc’ciavin which stems from the Italian Lombard minority language.

As in any Alpine mountain village, subsistence farming was the predominant economic activity of the population until the mid-20th century. In 1950, less than 50% of the population worked full-time on farms, falling to just 10% by 1990. Today, most of the farms are run part-time (Semadeni et al., 1994) and rely on additional income. The southern alpine climate permits mixed farming combining animal husbandry and arable farming and the varying climate allows multiple farming activities along the valley. In the 1990s, mainly grassland farming for livestock feed was practiced in the more northern part, and to some extent arable farming. Towards the south of Valposchiavo, warmer temperatures allow vegetable and fruit farming on small lots. Other cultivated crops include chestnuts/walnuts, cereals like rye and buckwheat, and special crops like berries, herbs, and medicinal plants (Lentz, 1990). In 2021, with 83.5% of organically farmed land, the Regione Bernina had the highest share of organic agriculture in Switzerland (BfS, 2021b). Since 2010, the number of organic farms has grown to 63 (out of 84, 2021; BfS, 2021b).

The economic situation of Valposchiavo is dominated by the hydropower company Repower and by the railway company Rhaetian Train that runs the Bernina train line, who provide jobs in the valley (Semadeni et al., 1994; Regionalentwicklung OBV, 2015; Regione Bernina, 2016). The Repower company was founded in 1904 as the Kraftwerke Brusio and operates today on the entire Swiss and European energy market (Repower 2023). In 2008, the Rhaetian Railway in the Albula/Bernina Landscapes (the train line between Thusis in Switzerland and Tirano in Italy) was certified by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as a cultural world heritage because of its historical and technical significance for Valposchiavo, which positively stimulates tourism. An UNESCO buffer zone was established for the landscape along the train line to limit negative anthropogenic impacts and to demand an integrated and environmentally acceptable land management at the same time (Pola, 2020, p. 210). The regional economy has since expanded towards tourism and today around 10% of the population works in tourism (Stettler, 2021). Contrary to most Northern Alpine valleys, summer tourism is much stronger than winter tourism. The valley focuses on soft touristic activities like hiking, mountaineering, and cultural and culinary offers (Semadeni et al., 1994; Stettler, 2021) and does not provide any large touristic infrastructure like ski resorts. In 1991, the highest number of overnight stays reached 138,000 (Semadeni et al., 1994). More recently, 45,000 overnight stays have been recorded (2015), increasing to 65,000 overnight stays in 2020 (Stettler, 2021).

2.2. Overview of regional development initiatives and projects in the case study area

100% (bio) Valposchiavo is a broad multi-stakeholder rural development approach of the Regione Bernina, including several initiatives and projects, such as a territorial brand. This regional development approach developed over the last 20 years (Howald, 2015) aims to revalorize local agrifood supply chains and to strengthen the socio-economic well-being of the population by harnessing territorial resources (Pola, 2020; Luminati and Rinallo, 2021). The development approach was initiated with the help of compensation payments from the local hydropower company for a large dam project planned around the year 2000 (Pola, 2020). An agricultural compensation fund group was created with actors from the hydropower company and the two municipalities of Poschiavo and Brusio with the aim to support the local agrifood sector in the valley (Howald, 2015; Luminati, 2021). Further, a project funded by the Swiss regional development project (PRE2) scheme was set up by representatives of the associations of agriculture and tourism of both communes, in which many food producers, processors, and consumers are organized. It was professionally supervised by a private sector planning agency specializing in consulting and research for rural development, with a focus on agronomy and rural economy (Beti et al., 2014).

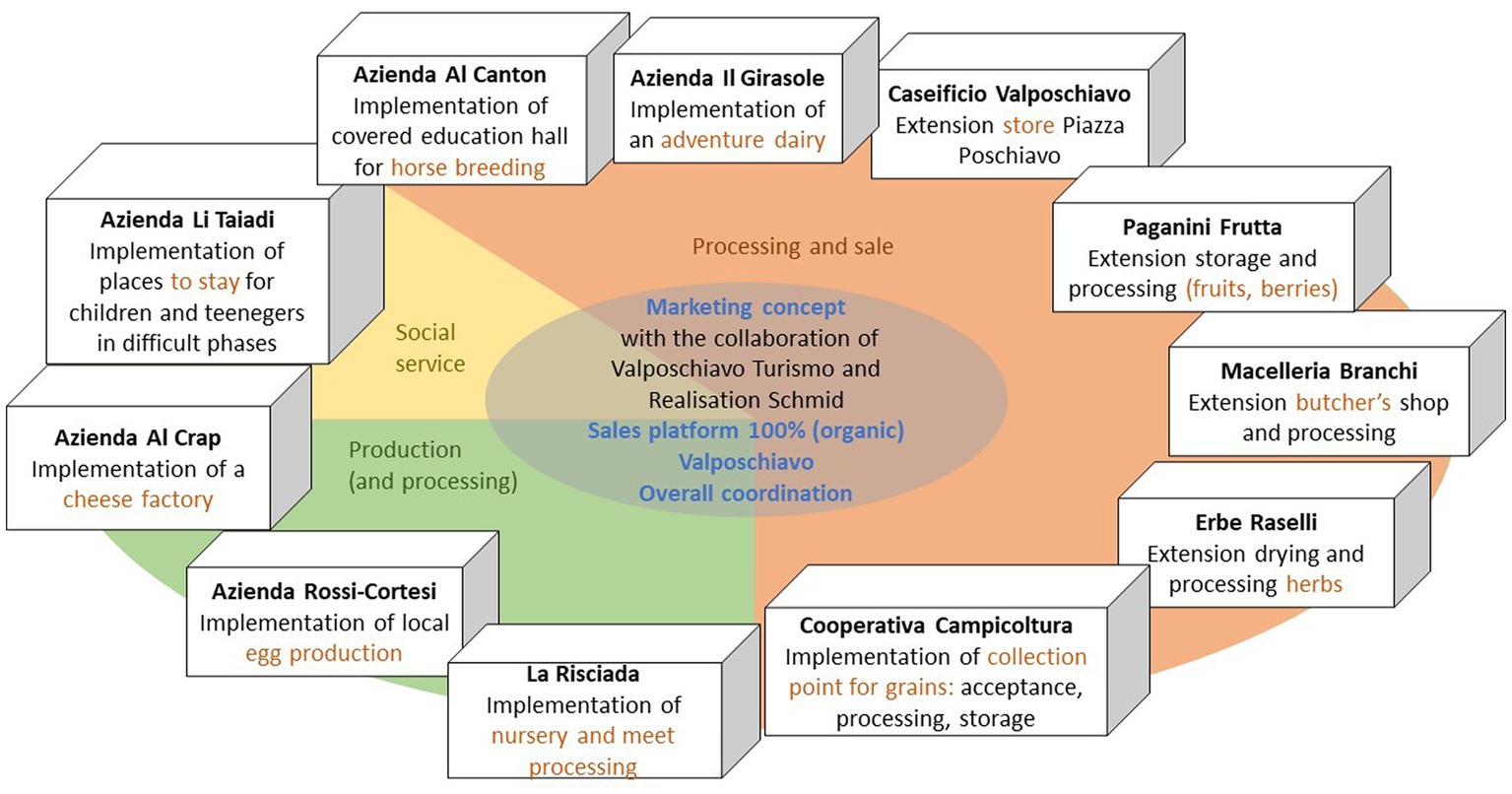

The PRE project was launched in 2020 to run for 4 years, with three core activities: the marketing concept, to be realized by Valposchiavo Turismo; the development and operation of a marketing B2B platform for the 100% Valposchiavo products, and the overall coordination of the project activities. The PRE also involves 11 businesses mainly active in agrifood production and processing at the core of the project (see Figure 4; Pola, 2020).

Figure 4. Structure and participating actors of the PRE 100% (bio) Valposchiavo, Source: Pola (2020), created by the authors.

2.2.1. The territorial brand 100% Valposchiavo

In 2015, the tourism organization Valposchiavo Turismo, together with various actors from the agrifood associations, launched the territorial brands 100% Valposchiavo (produced and processed in the valley) and Fait sü in Valposchiavo (processed exclusively in the valley; Howald, 2015; Luminati and Rinallo, 2021) within the wider PRE project described above. It covers various dimensions, but central is the valorization of regional, traditional, and typical products from Valposchiavo through a certification regulation (Howald, 2015). In total, 150 different products from Valposchiavo have been certified so far (Luminati and Rinallo, 2021). Besides the territorial brand, the Charta 100% Valposchiavo—Albergatori/Ristoratori regulates the promotion of the two certification brands in the catering sector and includes offering at least three meals that fully originate and are prepared in Valposchiavo. This charter has been signed by 13 restaurants across the valley (Howald, 2015).

2.2.2. The Valposchiavo Smart Valley bio strategy

The Valposchiavo Smart Valley bio strategy is a long-term approach to regional development to certify the region as a biodistrict (Beti et al., 2014; Luminati and Rinallo, 2021). The PRE 100% (bio) Valposchiavo was formulated in the context of this wider strategy. It pursues a transformation to organic farming and moreover focuses on a smart development of the entire territory (Beti et al., 2014). This smart development in Valposchiavo includes, first, the efficient and organic use of the landscape, second, professional training by the center for training and regional development Polo Poschiavo, third, the promotion of renewable hydropower energy, and, fourth, the organization of active participation of the local population (Beti et al., 2014, p. 3). The training center Polo Poschiavo coordinates the implementation of the strategy (Luminati and Rinallo, 2021). However, a clear path of the project is to evolve during its implementation and will clarify how the formal organizational structures and the certification process will work in the end (Beti et al., 2014). This flaws in the development strategy in Valposchiavo can be explained by the general lack of governance and organizational structures for biodistricts (Groier et al., 2008; Stettler, 2021). Since 2020, the main practical tool of the Smart Valley Bio strategy is the so-called Community Hypermap, which is a participatory and digital approach to raise awareness about the value of the landscape, as well as the socio-cultural and historic characteristics in the territory (Luminati, 2021). It serves as a digital archive of historic and current knowledge of Valposchiavo.

Additionally, actors and networks of Valposchiavo are well connected and integrated to external actors networks in Switzerland and across the Alps. The training center Polo Poschiavo hosted for example several events the International Commission for the Protection of the Alps (CIPRA), or the EU Strategy for the Alpine Region (EUSALP). Additionally, Polo Poschiavo participates in several projects of different EUSALP action groups as well as it is involved in Interreg projects. These are for example the Interreg Sinbioval project (2018–2021) that aimed at strengthening the organic agriculture in Valposchiavo and the neighboring Valtellina in Italy or the Interreg Alpine-Space project Alpfoodways (2016–2019) that envisaged Alpine food cultural heritage. Currently, it is also a leading agency to integrate Alpine food practices into the UNESCO Register of Good Safeguarding Practices for programmes, projects and activities for safeguarding the intangible cultural heritage.

2.3. Research design

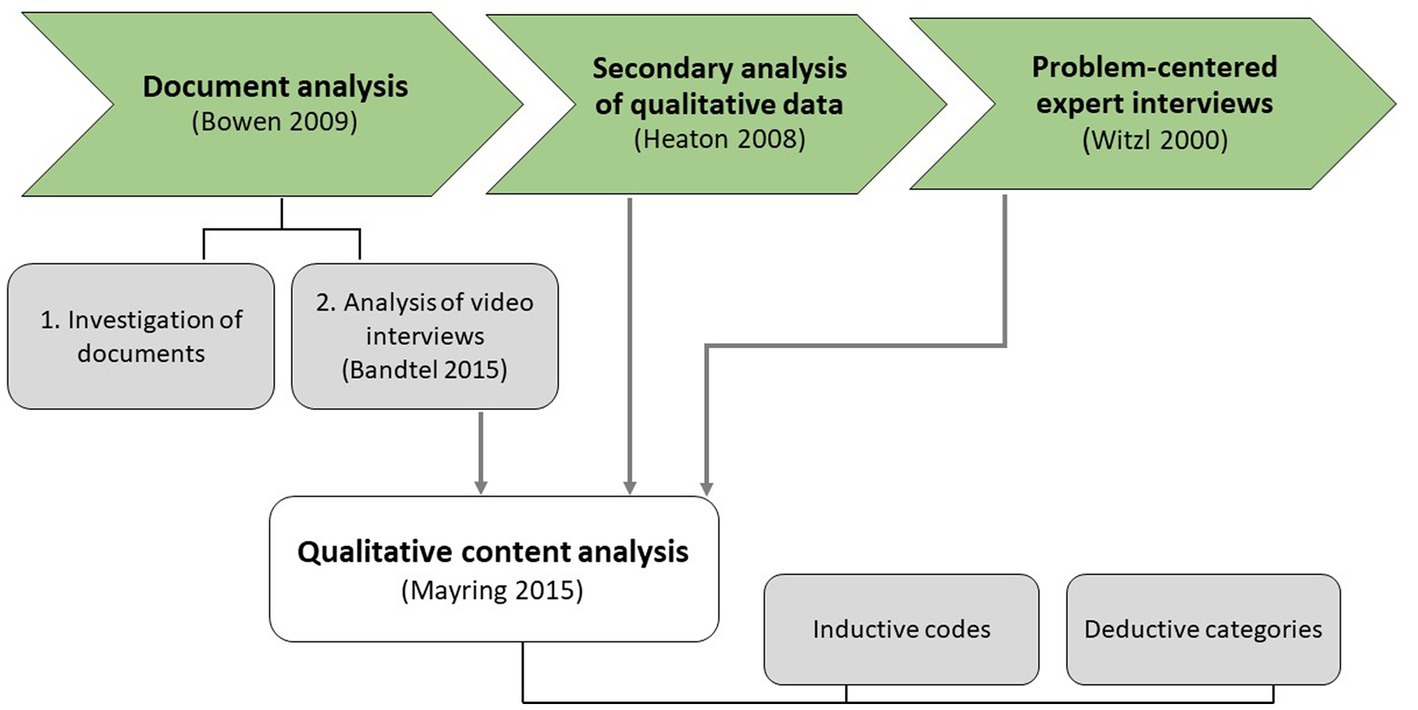

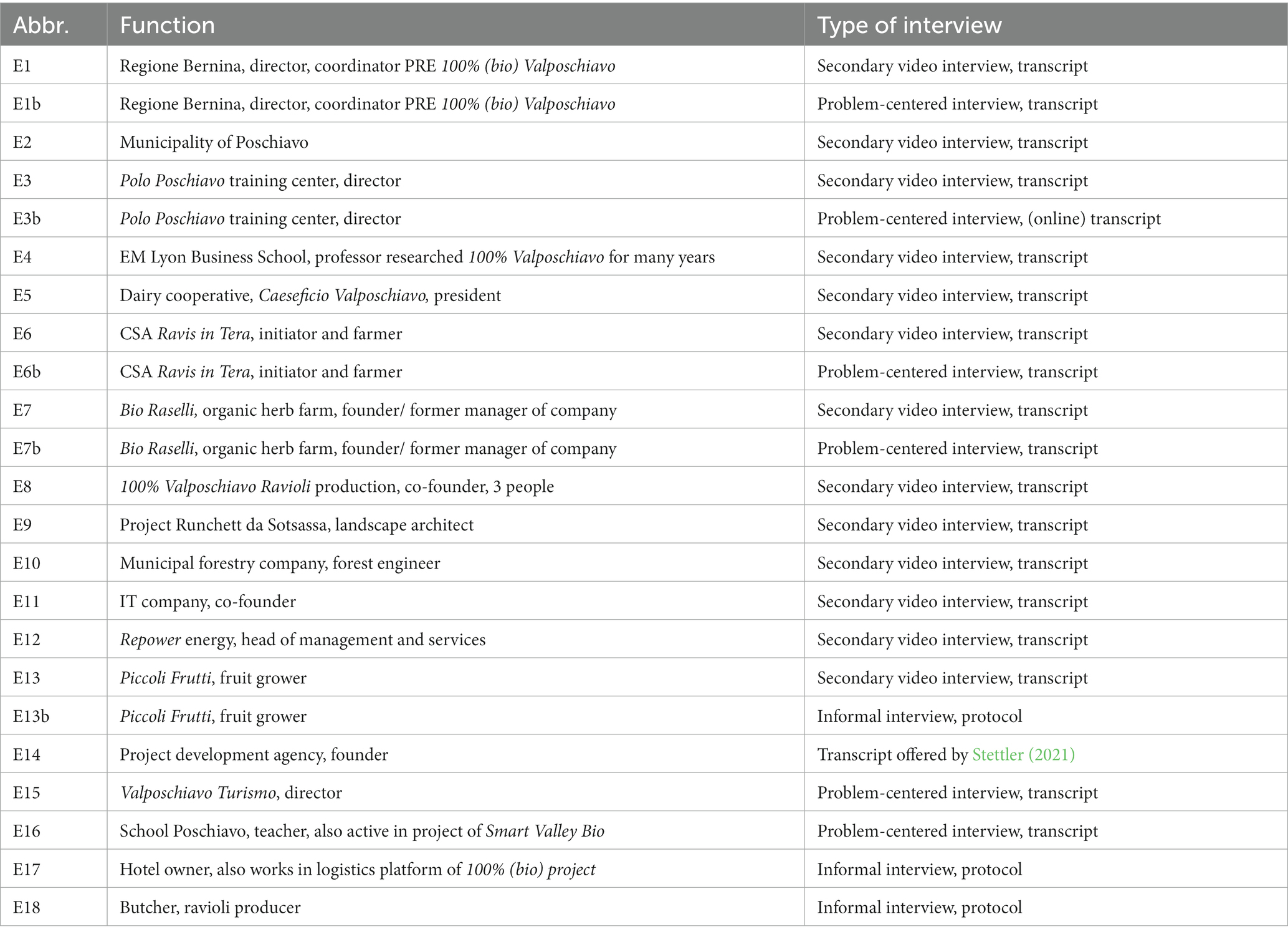

We investigated the territorial development in Valposchiavo in three steps (see Figure 5). First, we carried out a document analysis, second, we realized a secondary analysis of qualitative data, and third, we conducted problem-centered qualitative expert interviews (see Table 1).

In the document analysis (Bowen, 2009), we first compiled and investigated documents that provide background information as well as historical insight. For our investigation, research reports, scientific publications, public government documents, official statistics, annual reports, and articles of associations served to gain data on the context of the case study region. Later on, this information served in the sense of triangulation to seek convergence (Bowen, 2009). Second, we analyzed video interviews (Sharma et al., 2012; Bandtel, 2015). These were produced with local experts in the context of the Forum—Origin, Diversity, and Territories3 on the theme “Breakdown and rebound of territorialized food systems.” They were developed as staged interview constellations (Bandtel, 2015) and are publicly available on YouTube. The videos are in Italian with English subtitles, they were coded and analyzed with qualitative content analysis after Mayring (2015) within the software MAXQDA. This systematic, rule-guided, and theoretically grounded, approach is based on the inductive development of codes and on applying deductive verification of these to the research questions. Therefore, we revealed 21 inductive codes (deriving from the written qualitative data) that were later deductively grouped into the four modes of neo-endogenous development.

Subsequently, we analyzed an uncoded transcription of an expert interview within the process of secondary analysis of qualitative data (Heaton, 2008), meaning that it was conducted within another research project4 by a researcher who investigated social innovation in Valposchiavo (Stettler, 2021). As this interviewed person was difficult to contact and our research aims were somehow similar, we decided to reuse the existing qualitative material, also in terms of economical use of participants’ resources as well as of research funding (Heaton, 2008). This transcript too was evaluated with qualitative content analysis (see above).

We then entered the research field with this broad prior knowledge to conduct in-depth, problem-centered expert interviews (Witzel, 2000; Bogner et al., 2009). For specific questions that arose from the first two steps of the investigation presented above, we held five expert interviews in January 2023 and one online expert interview. The interviews lasted between 30 and 60 min and were recorded for later transcription. These study participants provided written informed consent. Additionally, during our field visit, we had seven short informal interviews (up to 15 min) that were not recorded, although participants were informed about our research aims. From these interviews with, for example, bakers, a pasta producer, restaurants, hotels, and farmers, we drew up protocols (Gray and Jensen, 2022) to be considered for evaluation. Anonymized transcripts and protocols were descriptively evaluated with qualitative content analysis after Mayring (2015; see above) for further interpretation.

3. Results

The following chapter is organized along the structure of the theoretical model of neo-endogenous development by Ray (2001), i.e., according to the modes I–IV of the culture economy. The examples, projects, etc. have been assigned to the dominant modes. For a better understanding of our case study, we rename Mode II as internal promotion of the constructed vision and Mode III as external promotion of the constructed vision.

3.1. Mode I: territorial values, product identities, and agrifood supply chains

Territorial values and product identities shape Mode I and are expressed in several agrifood supply chains, such as the local dairy, the ravioli pasta supply chain, the small-scale fruit production, medicinal herb production, or solidarity vegetable farming.

3.1.1. Territorial values and product identities

The territory of Valposchiavo with its distinct natural (e.g., climatic conditions) and cultural (e.g., traditional farming) characteristics contributes to the territorial value and forms its identity. Historically it features repeated periods of out- and back migration that included a brain gain in the past as well as recently (E14, E13, E1). A local conservation project of the dry stone walls, for instance, expresses the collective identity that people associate with this landscape (E9). Organic agriculture demonstrates one core value (E1, E14), rooted in the long tradition and early transformation in the 1980s by some “bio pioneers” from conventional to organic livestock and pasture-based dairy farming (E13, E14). One expert (E1) explained the specific identity present in the products from the valley as follows: “[…] We have an almost 100% organic territory with quality products grown with a truly great passion by farmers and those who work the land and animals in general.” Historical relations with neighboring Valtellina resulted in a distinct restaurant culture, “I believe that restaurants have historically been important for us, we in the south pick up a strong legacy from the Italian side, but we also have our own identity in catering.” (E1). As result, the so-called product identity mainly focuses on the territory and its unique characteristics.

The collaboration of farmers, processors, and the restaurant sector is seen as crucial for building strong supply chains, keeping the added value in the valley, and also for marketing the region successfully (E1, E14). The collaboration needs special efforts in planning and organizing for all actors involved because restaurants must decide a long time in advance which vegetables they want and in what dishes to offer them much later in the season (E6). This requires organization and a high degree of flexibility in restaurants.

3.1.2. Agrifood supply chains

These values and identities, which actors associate with the territory and with agrifood products, are expressed in several agrifood supply chains, some of which are briefly presented here. One traditional product with strong ties to the territory is the Valposchiavo cheese, which is locally produced in the organic dairy Caeseficio Valposchiavo, a cooperative of 13 farmers producing organic hay milk. Before the merger in 2011, another dairy existed (E5, E14). With the transformation to only one organic dairy, many farmers also converted to organic during that process (E7b).

The production of ravioli stems from a collaboration of agrifood processors: a butcher, a pasta producer, and an agritourism operator. Together they produce new ravioli variations by combining traditional pasta production with innovative processing (E8), as they use local flour, produced by the farmers’ cooperative Cooperativa Campicoltura, reviving the cultivation of buckwheat and the use of fillings from the valley. Dedicated to a ‘nose to tail’ strategy, they use a certain meat salami made from pork innards (E8). The ravioli is also certified by the 100% Valposchiavo brand and distributed in markets/stores in the valley, as well as offered in dishes by restaurants and hotels. The ravioli producer (E8) mentioned that the 100% certification also helps greatly in selling the ravioli, people recognize it and appreciate the products. People associate it with the territory of Valposchiavo.

In fruit cultivation, the agrifood company Piccoli Frutti in the southern part of Valposchiavo specializes in berries. The 10 hectares of farmed land are managed by 10 permanent employees and 40 fruit pickers (E13). The farm cultivates around 70 separate small plots from approx. 40 people in the region, which make up around 8.5 hectares. The plot owners themselves often help with the harvest and are paid annually in cash by the agrifood company Piccoli Frutti for the lease. In summer the produce is sold directly as dessert berries, and in winter, frozen berries are processed into jam, juice, etc. From an economic perspective, such production methods are seen as “an absurdity” (E13). On the other hand, they offer agronomic advantages for the microclimate, for biodiversity, and phytopathology, because plant diseases cannot spread too easily across all the fields, as the little plots are scattered (E13). Moreover, the agrifood company is innovating, for example, it launched a project in 2017 to cultivate olive trees on the dry-stone wall terraces, with 40 trees, and harvested 10 l of oil in 2020. The company further launched a collaboration of 30 families with chestnut groves in 1992 to uphold the tradition of chestnut cultivation.

The organic herb agrifood company Bio Raselli is one of the pioneers of organic farming in the valley, with around 30 years of organic production. Their main business is herbs and medicinal plants for teas, sweets, and other herb mixtures. In addition to the farming activities, the company also processes the harvested herbs itself, from drying, mixing, to packaging (E7), thus generating added value in the valley. Another agrifood initiative is the community-supported agriculture project Ravis in Terra (Volz et al., 2016), which translates as “joy in the soil” (E6). Started by two women to grow vegetables in cooperation with processors in the valley, it has evolved to six women engaged in growing and 20 prosumers. However, this project stopped in 2022 for organizational reasons (E6).

To improve the distribution of products and link actors along the supply chains, an online B2B marketing platform is currently being developed. The aim is for hotels and restaurants to purchase all their local products through this platform, which also manages logistics, billing, and other administrative aspects. This should facilitate work for the different stakeholders along the supply chain (E1).

3.1.3. 100% energy supply from Valposchiavo

The local labelled agrifood strategy of 100% Valposchiavo is about to be extended to the energy and timber sector. Local renewable energy and the local hydropower company Repower are seen as a “powerful lever for local economic development” (E3, E12). One aim within the valley is to achieve energy self-sufficiency, again intended to label this locally produced sustainable energy as 100% Valposchiavo (E3). A recent pilot project aims to develop and certify localized timber supply chains (E3b). In the past, this economic activity was widespread across the valley but lost its economic importance in recent decades (Stettler, 2021); the project now aims to revive local timber production (E3b).

3.2. Mode II: internal promotion of the collective development vision

In this mode, the focus is on the collective territorial vision and its internal promotion across Valposchiavo, which is shaped by actors and networks as well as initiatives and projects.

3.2.1. Construction of collective vision for territorial development

The common vision for the territory, rooted within the community, was elaborated in a study on the local context of organic agriculture in 2004/5 (E14). The extraordinarily high share of organic farms led to the idea to valorize this potential and to further increase the share of organic farms and products, as well as its high added value (E14). The collective vision for territorial development is integrated in the formulation of the long-term Valposchiavo Smart Valley Bio strategy with the aim to certify the region as a biodistrict.

3.2.2. Focus on the territory: cultural heritage and landscape conservation

The territory and the landscape are considered the most important aspect for the development of the region (E1, E2, E3, E9, E13, E-14), this includes the cultural landscape and the valley’s heritage (E9, E3, E13). This has been valorized with the certification of the Rhaetian Railway in the Albula/Bernina Landscapes as a UNESCO world heritage (E3). Moreover, the valorization of the terraced landscape in Valposchiavo, constructed from dry stone walls, as a traditional farming practice demonstrates the meaning that is given to the cultural landscape; a practice that tended to disappear with the modernization of agriculture (E9). In the project Runchett da Sotssass, initiated by a local landscape architect, the traditional knowledge of building dry stone walls is being revived (E9).

Another example that underlines the importance of local heritage is the so-called Casa Tomé, the oldest building in the valley in the center of Poschiavo, which has been revived as a living museum that communicates the old way of rural living. Events like collective baking of the traditional rye bread (E3) or cooking of the local dish Pizzocheri take place here. The community hypermap as a part of the Smart Valley Bio strategy is another important tool for collecting and restoring traditional knowledge, values, and cultural heritage in the territory of Valposchiavo (E3, E9). One expert explains the aim of the project to: “[…] be able to tell and visualize everything that has happened in this territory in recent years through a tool shared with the population” (E3). One characteristic of this digital archive is the open source software so everyone can contribute to developing the map (E3).

3.2.3. Internal communication and connections between actors and networks

Interviewees stressed the close personal contact of three local individuals as a starting point for creating a project (E14). Interestingly, these people all have academic backgrounds and external experience with regional development projects (E14). One expert (E14) explains that the creation of the project stems from a personal network, “We all have different experiences and so we could complement each other. We did not seek each other out. We casually knew about each other, and at some point, we sat together at the same table. Somehow it is a coincidence.” (E14). The director of the tourism association was also mentioned as a central figure. Together with the director of Polo Poschiavo, he forged the contacts between farmers, processors, and restaurants within the 100% (bio) Valposchiavo project (E3,E14). Polo Poschiavo, a training center and agency for development projects, fulfils several roles in the valley. It develops and accompanies regional development projects; organizes IT infrastructure, computer training, and other educational courses. Additionally, it is well connected with actors from the valley in the tourism, agriculture, processing, restaurant sectors, etc., and its director is active in diverse roles. The director of Polo Poschiavo was elected president of the Regione Bernina from 2014 to 2019, is co-founder of the PRE 100% Valposchiavo, and had developed many other regional development projects before (E14). He is also well connected with external actors and networks across the Alps, like the CIPRA, or the EUSALP. He was also a major figure in the process of the UNESCO certification of the Rhaetian Railway in the Albula/Bernina Landscapes (E3). These connections to external actors and networks (see for details, Section 2.2) reflects a strong bridging social capital that enables access to knowledge.

The limited territory and remoteness of Valposchiavo are seen as a reason for close contact between different actors in the territory (E1, E13, E14). The project of 100% (bio) Valposchiavo functions as a social process of actors who come together also because they are isolated and must get creative (E13). The limited area further requires that people use the resources that are present in the territory creatively and innovatively (E1). One expert (E1) comments, “Our good fortune and our misfortune lie in the fact that the territory is limited, so we must be good at making the most of it. It is a limitation because we cannot become too big, but it is fortunate, because in this way, we have to make the most of our resources, we have to use our heads work.”

One result of the strong communication and internal promotion across Valposchiavo is described as the pride of local people in the local products and that they consume them more (E4), as one expert underlines,” […] In the population, there is this concept of 100% Valposchiavo, which has become a trend, in the sense that everyone eats pizza with local flour and then posts a photo on social networks and says, “look I’m eating 100% Valposchiavo pizza.” There is a pride in eating like this and it is beautiful. It has brought a certain identity and enthusiasm to this local dynamic that has developed in the valley,” (E6).

Another aspect that is important for the internal connections of actors are the historic external mobility patterns of people from Valposchiavo, as many emigrants, then and now, with financial as well as human capital for development (E1). In more recent history, this mobility can be also seen in the network that initiated the 100% (bio) Valposchiavo network.

3.3. Mode III: external promotion of Valposchiavo

Local products and the tourism sector, as well as territorial initiatives and projects, are promoted and marketed outside of Valposchiavo, which means that it is well-known and connected externally (E7, E1, E3, E14). The ongoing movements of people from the valley described above in Chapter 2 is one reason for the development of external connections, networks, and expertise. The development of the PRE 100% (bio) Valposchiavo is just one example (E14).

3.3.1. Tourism marketing and rural–urban linkages

The tourism sector in Valposchiavo is an important factor in the external promotion of Valposchiavo. Local tourism has developed strong marketing and is nowadays well known outside the valley (E3, E14). The focus is on soft tourism activities, and especially on culinary aspects like tastings, events, agritourism, and the promotion of typical local products. The combination of farming and tourism is widespread in Valposchiavo as a way to diversify incomes. Several farmers, but also processors, offer additional touristic activities (E8, E13). The absence of any large infrastructure for winter tourism is another aspect mentioned as important for today’s situation (E14). The main three aspects for its positioning in tourism are the unique mountain landscape, the high share of organic agriculture, as well as the historically evolved variety of local supply chains in the valley (E14).

Proof of successful marketing to attract external tourists for the soft tourism model of Valposchiavo is the boom of guests during the Covid pandemic, as an expert pointed out (E4), “I would also dare to say, […] Valposchiavo, in general, felt the pandemic crisis in a very much lesser way thanks to the reputation this valley enjoys, also thanks to […] 100% Valposchiavo [and] this local origin of the products, also communicated as a tourism argument by Valposchiavo Tourism; the fact that many tourists had to stay in Switzerland” (E4). Concerns were voiced about the occupancy rate in the hotel sector, especially in the winter season (E14).

In this context, territorial brands like 100% Valposchiavo could serve to renew rural–urban linkages and exchange. Rural areas hold an immense diversity of knowledge and old practices worth sharing with external areas, territories, communities, and people (E4). Related to this aspect, the interregional and cross-border exchange between regions is also seen as an important development that allows creating additional external strategies and synergies that are right outside the territory. “These exchanges make […] and shape communities of practice and this is a way of transmitting knowledge that truly allows us to create strategies adapted to places,” (E4).

Another aspect of the external promotion of the territory is the way actors in tourism, farmers, etc. communicate the origins of their products and their production with a strong link to the territory. People and guests who come to Valposchiavo do not only see the local special products, but they immediately see how they are produced and transformed into the end product, explains one expert (E1). Farmers and producers see it as something crucial to connect producers and consumers. People get to know the quality and specialty of products (E7). In this way, people recognize producers (also processors/transformers) not only as producers who disappear once the product is finished, but as “figures that are present on local markets and who are connected to the product,” (E7). This might encourage visitors to connect with agrifood products and develop new values, also for the farming practices and the reality of farming (E7). This connection also fosters an understanding of the higher production costs of the quality products from the mountains, which could so be better communicated (E4, E14). One expert explained, “People will feel attached to the product, because they feel a special connection to the territory where they are in that moment. Tourists on site, tourists far away, maybe still buy such products, talk about it.” (E4).

3.3.2. External distribution networks in the supply chains

The certification scheme of the territorial brand 100% Valposchiavo has a clear focus on promoting and placing the products successfully on the market, not only locally, but also externally all over Switzerland (E7, E14). The external distribution for producers and processors of larger quantities is necessary for a small territory like Valposchiavo (E14). The focus on the local resources and the added value that remains in the valley is seen as the basis, but the distribution to external free markets and competition is something that actors mentioned as important (E7, E14).

Different actors also mentioned that the external sales of the products are not just about selling but about promoting the territory of Valposchiavo, as well as local development and organic farming (E1, E4, E7, E13). One expert explained, “It is a company [organic herb producer] that has promoted a good image of Valposchiavo. We make special products, and we make organic products […], and people come from many different places to visit us, and I have the impression that we convey the idea of being a dynamic company and a company active in the area, that provides jobs, brings well-being, creates a positive and ecological image of the Valposchiavo, and I want to reiterate that it brings work in these valleys, where it cannot be taken for granted.”(E7).

3.3.3. Prizes and media attention

Through international networking, lobbying, and events, Valposchiavo raised awareness in Switzerland and beyond (E3, E14). The PRE 100% (bio) Valposchiavo won several prizes and awards5 for innovative regional development strategies in mountain areas, such as the LIASON award 2019, which is a European-wide network of institutions working in the rural context. Besides this aspect, Valposchiavo has also been presented as a brand and destination at international exhibitions, such as the EXPO6 in Milan in 2015. Further, the valley has been portrayed in several Swiss and Italian TV formats that finally also promoted the valley itself. One expert mentioned the impact of this external interest, “Television has already come twice to make programmes, and therefore thanks to this product, the name Valposchiavo has truly been brought to half of Europe. Because Rai (Italian television) came to [produce a programme], […] this is an enormous advertisement for the whole territory” (E8).

3.4. Mode IV: normative strategies for territorial development in Valposchiavo

Finally, Mode IV integrates the above-presented modes I, II, and III and underline their contribution to a normative strategy for territorial development.

3.4.1. The guiding principles of territorial development

One important underlying principle for the normative development path is the collective vision of actors that has evolved over the last 20 years and become a principle for the territorial development of Valposchiavo (E3). Central to its long-term success is the combination of local initiation of projects with external support and input (E1, E3, E3b E14). One expert explained this aspect so, “100% Valposchiavo is […] much more bottom-up. We have made the rules ourselves. The charter has been created by the actors themselves. This is how we proceed. The farmers became organic themselves. They gave themselves the rules. It wasn’t top-down, at some point, almost everybody was in favor of it,” (E14). Further, the regional development is considered dynamic, as a slow and steady process aimed to “put together a set of mosaics” (E3). Experts involved highlighted the common philosophy and vision that has spread among the different actors and also within the population (E3, E6, E14). Considering the local consumption of 100% Valposchiavo products, it is also integrated with the local population (E6).

3.4.2. Instrumental ends of territorial development

Instrumentalization for territorial development is rooted in the collective vision and guiding philosophy of territorial development described above. The actors aim for the permanent integration of the initiatives and projects that exist across Valposchiavo (E3b). Therefore they have started the regional development approach for Valposchiavo, summarized under the label Smart Valley Bio (E3b). It includes different theoretical and practical components in the long-term development perspective of certifying the entire territory as an organic valley (E3b). That is why the Perspective 2040 is being developed to integrate projects, initiatives, and networks within an official regional development strategy (E3b). A multi-stakeholder platform, consisting of representatives from farming, business associations, tourism, culture, education, as well as political actors, has been established to jointly work out the Perspective 2040 strategy. The aim is to create a permanent communication platform that continues to work on the territorial development of the valley (E3b). Part of the Perspective 2040 strategy is for the platform to set up a monitoring scheme for certifying the region in the future, as one expert explained, “Monitoring would make what everyone already sees a bit more tangible. These criteria would then enable the monitoring, because we could collect regular data to see how the whole thing is developing.” (E3b). One participatory instrument in the project Smart Valley Bio is the so-called community hypermap (E3). Within the digital map, perspectives and values of the landscape are gathered by the local population. Another part of the Perspective 2040 strategy are the already established projects of localizing the supply chains, like the 100% (bio) Valposchiavo project, as well as the territorial brand 100% Valposchiavo for products and meals (E3, E3b, E14).

In Valposchiavo, close links exist between the different stakeholders from the valley with the political level (C3, E14). These strong ties have encouraged the initiation and funding of official development projects. The project 100% (bio) Valposchiavo has become a formal PRE (E14). Since 2021, the new director of the Regione Bernina heads the project 100% (bio) Valposchiavo as a coordinator (E1). This change in the structure of the staff has led to an institutionalized coordination of the regional development in Valposchiavo with a clear contact point at the administrative-political level of the Regione Bernina (E3b).

4. Discussion

4.1. Instrumental and normative ends of the territorial development approach

All four modes of Ray’s model of neo-endogenous development are present in Valposchiavo but in a historical and chronic way. Therefore we organized the neo-endogenous model in an adapted and sequential way after (Stotten et al., 2018; Figure 2). In our case study, our defined Mode II refers to the internal promotion and local agency, whereas Mode III covers the external promotion of the territory. This schematization (see Figure 6) acknowledges that neo-endogenous development is primarily initiated from bottom-up, endogenous processes and is subsequently guided by external processes (Gkartzios and Lowe, 2019).

In Valposchiavo, a strong historically grown territorial identity exists among the population that forms the starting point for neo-endogenous development (Ray, 2001) and considers place-specific identities as crucial for successful and sustainable regional development (Meier et al., 2010; Weber and Kühne, 2015). Historic processes, as well as more recent developments and decisions in Valposchiavo, explain the territorial identity and indicate a pronounced cultural and social capital (Bourdieu, 1986), which in Ray’s (2001) model is expressed as cultural markers. Further, a diversified, small-scale family agriculture based on specific climatic conditions has long been the prime activity in the territory on which the socio-economic well-being of the communities was based. As in many other rural mountain regions, food production lost its importance for the local economy which has shifted towards the service sector and ICT (Ward and Brown, 2009). However, Valposchiavo strongly relies on organic farming, with the highest share in Switzerland, and organic pioneer farmers started 40 years ago (Arbenz et al., 2017): The prevailing extensive and pasture-based farming and the conversion of the local dairy to organic production are certainly practical reasons for this high share. Still, results revealed that many actors and initiatives in the agrifood sector rely on the holistic principles and values of organic agriculture (Luttikholt, 2007; Arbenz et al., 2017). In addition, historical food and culinary specialties, such as cheese, pasta dishes, or herbs (Semadeni et al., 1994; Howald, 2015) express the territorial identity that influences successful community-driven development (Flora and Flora, 2008; Marango et al., 2021). Moreover, the territorial identity in Valposchiavo has been used by local actors to attach it specifically to locally produced and processed organic agrifood products, which forms Mode I in the model of neo-endogenous development (Ray, 2001; Figure 6).

To reveal the roots of the product identity, two processes (territorial specificities) favored the valorization of the territorial identity. First, the certification of the Rhaetian Railway in the Albula/Bernina Landscapes as UNESCO cultural heritage motivated a new re-valorization of the high quality of the cultural landscape and its sustainable use (Pola, 2020). Second, the collective agricultural compensation fund group of the local energy company and the two municipalities of Valposchiavo enabled a territorial development approach to support the entire agrifood sector across the valley.

In Valposchiavo, the territorial vision (see Figure 6) which links Mode I to the following modes (Ray, 2001; Stotten et al., 2018) was developed in several steps. First, based on a high share of organic farming and the strong territorial identity, local actors in tourism and farmers associations launched the territorial brand 100% Valposchiavo that ranges over and connects various local supply chains and thus strengthens the local economy (Lorenzini et al., 2011). Second, to embed the new promotion of agrifood products in the shape of the territorial brand in a wider territorial development context, the regional development project (PRE) 100% (bio) Valposchiavo was initiated by stakeholders from the agricultural compensation fund group and the Regione Bernina (Luminati and Rinallo, 2021). The aim of the PRE is to support several agrifood businesses infrastructurally by creating a marketing platform for local products that fosters Mode I of strong product identity. As the PRE is oriented to further transform agriculture towards 100% organic, it takes into account the territorial dimension of the holistic understanding of organic agriculture (Arbenz et al., 2017). Based on the two aspects above, a territorial vision is being developed as a long-term strategy to finally create the Smart Valley Bio.

Based on the territorial vision, actors in Valposchiavo promote their territory internally (Mode II) as well as externally (Mode III). Diverse local actors from different sectors like agrifood, catering, tourism, industry, regional development, and politics are involved in the development processes of the territorial brand, the PRE, or the Smart Valley Bio strategy. They have formed strong multi-stakeholder networks (Dias et al., 2021), however, the results identified three key actors for shaping the wider territorial development approach (Figure 6). First, Polo Poschiavo with its diverse roles makes it a key factor in the local regional development. Second, the double role of the coordinator of the association 100% (bio) Valposchiavo as also president of the political Regione Bernina facilitates a political acceptance and backing of the wider territorial development approach by directly linking the PRE with the governance level (Böcher, 2009). Third, the local tourism agency Valposchiavo Turismo is actively integrated into the territorial development, owning the territorial brand 100% Valposchiavo and being in charge of the PRE’s marketing concept. These three actors provide strong social capital and can be seen as what Böcher (2009) calls regional promoters who manage, shape, and ensure the success of projects (see also Bosworth et al., 2016).

In the adapted model, Mode II covers internal promotion as explained above (Figure 6). Both the territorial brand and the development project 100% (bio) Valposchiavo contribute to stronger local and often organic supply chains in the agrifood sector (Stotten et al., 2018). Actors along the agrifood supply chains re-orientate themselves to local collaborations and networks by joining the territorial brand, signing the charter, or taking part in the PRE (Stotten et al., 2018; Vittersø et al., 2019). The small territory and the historically tightly knit community are additional factors that strengthen the social and cultural capital, as well as cohesion (Wilson, 2012) between actors, such as the ravioli agrifood supply chain.

Figure 6. Neo-endogenous development in Valposchiavo based on Ray (2001) and Stotten et al. (2018), created by the authors.

External networks and promotion (Mode III) appear in several ways: the external distribution of agrifood products, the external network and attention of the regional development actors in Valposchiavo, and the role of tourism. First, some small and medium-sized agrifood businesses across Valposchiavo rely on strong external marketing and distribution networks that favor rural–urban linkages (Woods, 2013; Chatzichristos et al., 2021). The limited number of actors, however, might lead to an unequal distribution of added value in the valley (Donadieu de Lavit, 2022). In contrast, the existing direct networks between local and external companies contribute to strengthening the neo-endogenous development approach (Woods 2009; Chatzichristos et al., 2021). At the same time, these strong external connections and networks integrate actors from Valposchiavo into global capitalist, mostly agrifood markets that reflect Woods’s (2007) concept of a global countryside. Second, actors from regional development and tourism have built strong interregional and collaborative networks that trigger external promotion and raise awareness of Valposchiavo (De Noni et al., 2018). These multi-stakeholder networks are characterized by decentralized personal relations and strong social capital (Lorenzen and Mudambi, 2013) and include local individuals who work in larger political, administrative, or planning organizations as well as being members of trans-Alpine and European and governance networks (De Noni et al., 2018). Third, the tourism agency Valposchiavo Turismo promotes a soft and sustainable tourism model by focusing on touristic options based on agrifood products, culinary experiences, and cultural heritage (Lee et al., 2015; Duglio et al., 2022).

Mode IV forms a synthesis of the other modes when a certain trajectory become normative and institutionalized (Ray, 2001). In Valposchiavo, this normative character starts with the historically evolved territorial vision. In addition, the implementation of the territorial brand and the PRE 100% (bio) Valposchiavo as “repertoires of strategic action” (Ray, 2001, p. 23) form an important basis for the long-term vision of certifying Valposchiavo as a biodistrict Smart Valley Bio (Böcher, 2009). Innovations like the online B2B marketing platform or the community hypermap as instrumental tools manifest the territorial vision and contribute to its normative character (Ray, 2001). The recently started multi-stakeholder platform to formulate the Perspective 2040 strategy brings together all the existing development initiatives in a single strategy (De Noni et al., 2018) and lays the basis for the future territorial governance of Regione Bernina. In this way, it strengthens the normative character of the territorial development approach in Valposchiavo (Gkartzios and Lowe, 2019; Chatzichristos et al., 2021).

In Valposchiavo, strategic action is based on the local, collective, and participative agency of diverse stakeholders who form collaborative and integrated multi-stakeholder networks, which are explicitly connected to external actors and processes (De Noni et al., 2018; Dias et al., 2021). Additionally, these networks enable social innovation that anchor ongoing projects within the society. This demonstrates that the territorial development approach in Valposchiavo is “locally rooted but outward looking and characterized by dynamic interactions between the local area and their wider environments” (Gkartzios and Lowe, 2019, p. 163). The valley thus follows a neo-endogenous development that overcomes the dichotomy of endogenous and exogenous regional development approaches but renews rural–urban linkages (Ray, 2001; Böcher, 2009; Gkartzios and Lowe, 2019; Chatzichristos et al., 2021). Despite being a remote region, the strong internal cohesion and the focus on local cultural heritage indicate that Valposchiavo is not a marginalized area, but that the development approach is embedded in the local social structures (Bock, 2016). This embedding in the sense of Polanyi’s concept also demonstrates that the approach of Valposchiavo offers an alternative to the negative impacts of globalization [Polanyi 1973 in Ermann et al. (2018, p. 41)].

4.2. Establishment of a biodistrict

Biodistricts in general as well as the investigated neo-endogenous development in Valposchiavo explicitly focus on the territory, based on the local conditions and resources, as well as actively integrating various actors (Schermer, 2003). Becoming a certified Smart Valley Bio, a goal that was first formulated in 2012, is a crucial part of the long-term strategy for the territorial development of Valposchiavo. This Smart Valley Bio can be understood as the institutionalization of the clustering of organic farming in biodistricts (Schermer, 2003; Groier et al., 2008; Stotten et al., 2018; Belliggiano et al., 2020). Following the theoretical concepts of biodistricts, developments in Valposchiavo strongly focus on a defined territory, are based on organic agriculture, highlight and promote local agrifood production and actively integrate actors from agriculture, as well as from the economic, environmental, and socio-cultural domain (Kirchengast et al., 2008; IN.NER, 2017). The high share of organic farming, the strong agrifood supply chains that are embedded in the touristic development, the focus on cultural historical heritage, as well as the diverse internal and external networks, indicate the potential of Valposchiavo to institutionalize a biodistrict (Guareschi et al., 2020; Dias et al., 2021). The results revealed that organic agriculture is not only about ecological production, but actors enhance the role of healthy, local, and fair agrifood production embedded in a wider regional and holistic context that contributes to rural development (Pugliese, 2001; Darnhofer, 2005; Arbenz et al., 2017). In this context, organic principles have become normative in Valposchiavo. Although no official organic certification for the region exists so far, the different development projects, the formulated strategy Smart Valley Bio and the recent creation of the long-term regional development strategy Perspective 2040 pull towards an official certification as a biodistrict or Smart Valley Bio (Groier et al., 2008; Beti et al., 2014). The currently developing monitoring and evaluation scheme by a multi-stakeholder platform in the context of the strategy might serve as an important organizational and tangible basis for the certification as a biodistrict (Groier et al., 2008; De Noni et al., 2018; Dias et al., 2021). By focusing on (technological) innovations and knowledge creation in the territory, based on endo- and exogenous processes, Valposchiavo also pursues a smart rural development (Naldi et al., 2015; Zavratnik et al., 2020; Gerli et al., 2022). Especially the focus on knowledge creation by Polo Poschiavo and the recently developed ICT tools, like the community hypermap, as well as actively integrating into the local population, can be seen as a community-centered, smart development in Valposchiavo (Naldi et al., 2015; Navío-Marco et al., 2020; Zavratnik et al., 2020). These developments reflect the concepts of biodistricts and smart regions.

Other existing biodistricts are embedded in existing structures like LEADER (Bioregion Mühlviertel) or national parks (Bio-distretto Cilento), so that broader concepts for biodistricts are missing (Guareschi et al., 2020). Thus, issues of governance structures are so far unresolved in Valposchiavo and new governance structures for the certification of a biodistrict would be needed for multi-level negotiations between the local and national levels (Pütz and Job, 2016). The neo-endogenous atmosphere in Valposchiavo is at least a good basis for facing such a long-term governance process.

5. Conclusion

Our analysis demonstrated that locally adapted strategies of territorial development in Valposchiavo become normative by following a neo-endogenous development path that relies on internal and external networks that renews rural–urban linkages and enables social innovation. We revealed three key aspects that facilitate the conversion into guiding principles: First, strategies are explicitly focused on the territory as they use the historically grown territorial identity and local resources for creating robust agrifood supply chains. Second, strategies are based on the existing local organic agriculture by integrating its holistic principles in the territorial brand 100% Valposchiavo and the PRE 100% (bio) Valposchiavo. Third, various actors take part in the development of strategies and form local multi-stakeholder networks. On the basis of these three aspects, the territorial vision to become a Smart Valley Bio is gradually implemented and currently manifests itself in the comprehensive long-term regional development strategy Perspective 2040 developed by a multi-stakeholder network. Thus, the normative character of locally adapted strategies of territorial development in Valposchiavo strongly favors the establishment of a biodistrict Smart Valley Bio. However, governance issues addressing aspects such as leadership or coordinating agency, still need to be aforwarded. Other approaches, such as biosphere reserves (BR), a concept that was developed within UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Programme that also strives for sustainable regional development, provide a governance system such as the multi-level governance system. Even if this is considered as a potential weakness of BR, it serves as a guideline to organize governance (Schliep and Stoll-Kleemann, 2010; van Cuong et al., 2017). Something that is missing for biodistricts on a general level.

Ray’s (2001) model of neo-endogenous regional development assumes that the actors of a certain region are more or less homogenous, which does not reflect social reality. This problem in turn limits any empirical application, as horizontal and internal power relations of actors are neglected (see Schermer, 2003), which is also true for our study. Future research is therefore needed to focus on specific power relations between actors in Valposchiavo and other case study regions. Finally, the case of Valposchiavo offers productive insights into the practice of neo-endogenous development that might serve other Alpine regions (like the Italian Valtellina or upper Val Venosta which seek to become a biodistrict) as a best practice example for their implementation. The Valposchiavo as a best practice example has already been acknowledged through the consultation of local actors by the upper Val Venosta that also aims to establish a biodistrict or the implementation of the Sinbioval Interreg between Valtellina and Valposchiavo, also moving towards a biodistrict.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

RS: conceptualization and funding acquisition. RS and PF research design, empirical fieldwork, and writing original draft. PF: data analysis. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund under Grant ZK 64.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all the respondents for their time and effort in participating in this research. We are also grateful for the transcript by Anna-Lena Stettler produced in the Swiss National Science Foundation project ‘Social Innovation in Mountain Regions’ (Grant Number 179112). They also wish to acknowledge very useful and constructive comments by the reviewers of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^http://www.ecoregion.info. Accessed February 16, 2023.

2. ^PRE stands for Projekt für Regionale Entwicklung (project for regional development), which is a national funding scheme to support Swiss agriculture and rural development in mountain regions. The main aim is to increase the added value in the agricultural sector across several supply chains in a certain region. The PRE must explicitly consider the general regional development policies and concepts of the region (https://www.blw.admin.ch/blw/de/home/instrumente/laendliche-entwicklung-und-strukturverbesserungen/laendliche-entwicklung/was_ist_ein_pre.html).

3. ^The forum Origin, Diversity and Territories is an international platform on the interactions between cultural and biological diversities and the sustainable territorial valorization of products and services whose quality is linked to their origin. The objective of the Forum is to facilitate the exchange of experiences and knowledge between a wide range of international actors, all committed to new ways of thinking and doing development, where identity, origin, quality, and local diversities are considered catalysts of inclusive dynamics of local and territorial development (www.origin-for-sustainability.org).

4. ^Swiss National Science Foundation project Social Innovation in Mountain Regions (Grant Number 179112; https://data.snf.ch/grants/grant/179112).

5. ^https://www.valposchiavo.ch/de/erleben/100-valposchiavo/das-projekt/243-100-ist-ein-hoher-anspruch. Accessed February 18, 2023.

6. ^https://www.regione-bernina.ch/it/istituzione/318-expo-2015-la-valposchiavo-a-milano?jjj=1671020072492. Accessed January 9, 2023.

References

Arbenz, M., Gould, D., and Stopes, C. (2017). ORGANIC 3.0—the vision of the global organic movement and the need for scientific support. Org. Agric. 7, 199–207. doi: 10.1007/s13165-017-0177-7