- 1KIT - Royal Tropical Institute, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 2Bioversity International, Rome, Italy

- 3Independent Researcher, Münster, Germany

- 4Bioversity International, The Hague, Netherlands

- 5International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), New Delhi, India

Gender-transformative change requires a commitment from everyone involved in agricultural research for development (AR4D) including organizations at international and national level, individual researchers and practitioners, farmers, development agencies, policy-makers and consumers, to transform the existing values, practices and priorities that (re)produce and perpetuate gender biases and inequities in agrifood systems. However, the adoption of a gender transformative agenda can be challenging, especially for AR4D organizations whose primary focus is not necessarily the attainment of gender equality. This paper looks at a collective, bottom-up, transformative effort within the AR4D organization of CGIAR. It advances the emerging CGIAR Community of Practice on Gender Transformative Research Methodologies (GTRM-CoP) as a case study to explore the potential of CoPs as social learning systems that create the conditions for transformation-oriented learning. Driven by an ethos of reflecting and doing anchored in critical and feminist principles and social learning praxis, the GTRM-CoP aims to be a safe space to spur reflexivity, creativity and collaboration to support existing work on gender transformation in CGIAR while re-imagining how gender in AR4D is conceptualized, negotiated and advanced. The paper focuses on the process leading to the development of the CoP, that is, designing for change, which is crucial for sustained transformation.

1. Introduction

The gender and development field is increasingly driven by transformative ambitions for women’s empowerment and gender equality across all areas of development including agricultural research for development (AR4D; Anderson and Sriram, 2019; Farhall and Rickards, 2021). These efforts are characterized by tensions around the meaning, translation and implementation of these ambitions in research and practice (Lopez and Ludwig, 2021; Lopez, 2022). Feminist scholars critique the instrumentalization, essentialization and depoliticization of gender in many development efforts and how gender matters are often implemented in a truncated form, for example, by prioritizing short-term targeted measures to the detriment of working toward long-term gender transformative goals; and by reducing gender complexities into ready-to-apply packages, tools, and guidelines (Baden and Goetz, 1998; Hawthorne, 2004; Sohal, 2005; Palmary and Nunez, 2009). In response, feminists working within organizations, including in AR4D, emphasize the multiple challenges of translating social justice ideals into research and development practice—especially in organizational cultures largely dominated by patriarchal, positivist, techno-centric mindsets (see for instance, Resurreccion and Elmhirst, 2021).

Underlying principles of gender-transformative scholarship emphasize that transformation requires a concerted commitment from all those involved in AR4D work, from individual researchers and development professionals to farmers, policymakers and development and research organizations, to challenge and transform the existing values, practices and priorities that (re)produce and perpetuate gender biases and inequities (McDougall et al., 2015; Sarapura Escobar and Puskur, 2015; Wong et al., 2019). However, the adoption of a gender-transformative agenda embraces that a feminist ethos can be particularly challenging in organizational cultures.

In this paper, we discuss the development of a Community of Practice on Gender-Transformative Research Methodologies (GTRM-CoP) within CGIAR, an AR4D organization comprised of multiple centers sharing common as well as individual AR4D and gender research agendas.1 CGIAR’s evolution over the years, from a primarily crop- and livestock breeding focus to its current systems transformation approach for food, land, and water systems, is resulting in an increasing focus on the social element of socio-ecological systems in agriculture and the environment, with an emphasis on gender research. Over the years, gender research has seen ebbs and flows in commitment and in capacity within CGIAR, both at the consortium and center levels. There have been significant achievements and examples of resistance, based on assumptions and beliefs about whether CGIAR should engage in research in which women’s empowerment and social equity is a goal alongside mechanization, productivity and crop improvement related goals (see for instance, Poats, 1990; Kauck et al., 2010; Van der Burg, 2019). However, concrete support for gender transformative work as well as for strengthening gender capacity, knowledge and expertise in individual CGIAR centers remains uneven. At present, CGIAR is committed to a reform process termed “One CGIAR.” As part of the new strategy, “gender equality, youth and social inclusion” is now one of CGIAR’s five core impact areas (CGIAR System Council, 2019). Yet, in this new portfolio of large, cross-center, multidisciplinary One CGIAR research projects through global and regional initiatives2 gender is addressed very differently. A few have adopted ambitious gender transformative goals while most aim to be gender-responsive (see definitions in Box 1) and some do not even consider gender matters. This perpetuates historical challenges for gender research and gender researchers, including limited capacity and underfunding; under appreciation of and willingness to understand social science epistemologies in CGIAR work; fragmentation of gender research and isolation of gender researchers in the organization. To partially address this, a new CGIAR gender research architecture is being developed. We use the GTRM-CoP—currently, the only established and funded space for gender transformative research across the CGIAR3, as a case study to show how taking a social learning “design turn” can provide an opportunity for transformative “reflecting and doing” and for building commitment and capacity for gender-transformative research within the CGIAR. The expression “design turn” recognizes that “a learning system” cannot be designed as such but is rather an emergent property of a set of design considerations which deliver a performance. A learning outcome emerges (or does not) from the interactions between (i) a context (ii) practitioners (here gender researchers) and (iii) tools, techniques, methods, methodologies, etc (Ison, 2010).

Together with the Introduction, the paper comprises five sections. In section 2, we advance the concept of Communities of Practice (CoP) and the theoretical dimensions and components that can influence the conditions for learning. As part of this, we describe the rationale for the feminist “reflecting and doing” process that guides and underpins the GTRM-CoP. In section 3, we present our case study and provide an overview of historical attempts to mainstream gender in CGIAR. The overview contextualizes the case study and locates it within recent efforts to advance a gender-transformative research agenda in the organization. In section 4, we examine the “reflecting and doing” process of the GTRM-CoP according to the set of design considerations adopted with the aim of creating the conditions for action-oriented learning. In the final section, we tie the design considerations back to CoP theory and how it is being used in practice and conclude with critical reflections about emerging limitations of the CoP as well as its potential for contributing to broader transformations of the ways gender in CGIAR and, more broadly AR4D, is conceptualized, negotiated and advanced.

BOX 1. Key terms and concepts*.

Gender-sensitive approaches: encourage the participation of both women and men with the goal of collecting sex disaggregated data and perspectives.

Gender-responsive approaches: aim to reduce gender-based inequalities by assessing and responding to the different needs/interests of women, men, boys and girls, and by incorporating the perspectives of women and girls.

Gender-transformative approaches: actively examine, challenge and transform the underlying causes of gender inequalities rooted in discriminatory social institutions. They aim to address the unequal gendered power relations, discriminatory gender norms, attitudes, behaviours, and practices as well as discriminatory or gender-blind policies and laws that create and perpetuate gender inequalities.

Gender-transformative change: refers to change toward gender equality. This change can be conceptualized as a process with three key dimensions: (1) building agency, (2) changing unequal power relations, and (3) changing discriminatory structures. To attain gender-transformative change one must engage with deeper barriers such as the underlying, and often unrecognized, structural causes of inequalities that are embedded in agrifood systems, including informal barriers (norms), formal barriers (laws, policies, regulations) and semi-formal barriers (such as national statistics and data systems). Gender-transformative change emerges from critical consciousness and involves fostering examination of gender dynamics and norms and intentionally strengthening, creating, or shifting structures, practices, relations, and dynamics toward equality.

Gender norms: informal rules and shared social expectations which determine and assign socially acceptable roles, behaviours, responsibilities and expectations to male and female identities. They set expectations for masculine and feminine behaviour considered socially acceptable and appropriate, affecting individuals’ choices, freedoms, capabilities and self-image.

Gender transformative research: is participatory, reflexive, critical, action-oriented and involves collaborative integration of research and practice. It requires a shared and contextualized understanding of the need for a profound gendered change in a specific setting. As a first step it demands personal and professional transformation, which in turns demands reflexivity, and a commitment to decolonizing approaches to development and research.

Gender-transformative research methodologies: aim to catalyze gender transformative and socially just change processes. Some of the principles underpinning gender-transformative research include conducting deep, intersectional gender analyses to understand the context and the multiple dimensions and layers of inequality and power; meaningfully engaging with and (if needed) building capacities of diverse actors to drive and sustain change processes; combining action to influence change with research on how change happens; and a focus on how norm and structural change can happen at scale.

*These are definitions of key gender terms and concepts used throughout the paper (Hankivsky, 2014; Cole et al., 2020; McDougall et al., 2021; Njuki et al., 2022; Rietveld et al., 2022). However, the list is not exhaustive as the terms and concepts in gender and agrifood systems are several, varied and in constant evolution. For more information about differences, overlaps and opportunities between distinct concepts for gender in agrifood systems, see Van Der Burg (2021), as well as the forthcoming (2023) publication of FAO, IFAD, WFP, and the CGIAR Gender Impact Platform focused on gender transformative change in food security, nutrition, and sustainable agriculture.

2. Background

2.1. Communities of Practice, definitions and design considerations for learning

Communities of Practice (CoPs) describe groups of people who share a concern, a set of problems, or a passion about an issue, and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this issue by interacting regularly (Wenger et al., 2002).

The core elements of a CoP are:

• its domain or purpose, such as the motivation that acts as a unifying call for action,

• its practice, that is, the actual tools, methods, frameworks or narratives that the CoP develops and uses,

• the community itself, representing people who are passionate about and committed to the domain, and want to improve their practice.

CoPs follow the flow of what people do naturally every day—discussing and improving practices they are passionate about, but with a more organized form structuring conversations more purposefully than in friendship groups or general discussion and making sure that the current of conversation and idea-making is periodically “reified”4 so that lessons can be learnt and a repertoire of practices built up (Wenger, 1998). CoPs can act as spaces to build and strengthen collective empowerment around a “convening call,”5 especially for individuals without peers in the immediate environment (Iaquinto et al., 2011). In CGIAR, many gender researchers work in teams mostly made up of biophysical researchers who are not necessarily trained in the social sciences, and who may struggle to fully appreciate the value of social scientists and of social epistemology (Mangheni et al., 2019). Gender researchers often feel isolated, as there is frequently only one in each multidisciplinary team. Lacking peer support or adequate mentoring and supervision, gender researchers can find it difficult to build their ideas and conduct effective research. Thus, intentionally connecting gender researchers to one another via a CoP would help to create a sense of “power with.” We hypothesized that the GTRM-CoP could have the potential to reduce gender researchers’ isolation in CGIAR, improve their knowledge and skills, and thereby increase their “power to” conduct more impactful and potentially transformative gender research for development.

While individual empowerment is important, collective empowerment of gender researchers in organizations is fundamental for institutionalizing transformation within the organizational culture and ensuring transformation has staying power. Collective empowerment seeks to “establish community building so that members of a given community can feel a sense of freedom, belonging, and power that can lead to constructive social change” (Hur, 2006, p.535). Similarly, social learning systems are proposed to be an organized and coherent group of individuals, collaborating together to achieve high quality transformations, with a deep appreciation of their own integrity, a keen sense of emergence, and an acute consciousness of their shared processes, levels and states of learning, as they design and create new and responsible futures together (see more in Bawden, 1995). For a CoP to be successful, members need to experience freedom to collaborate (within and outside of their organizational units), and interaction should take place at a pace and rhythm chosen by its members (Probst and Borzillo, 2008) which contributes to collective empowerment.

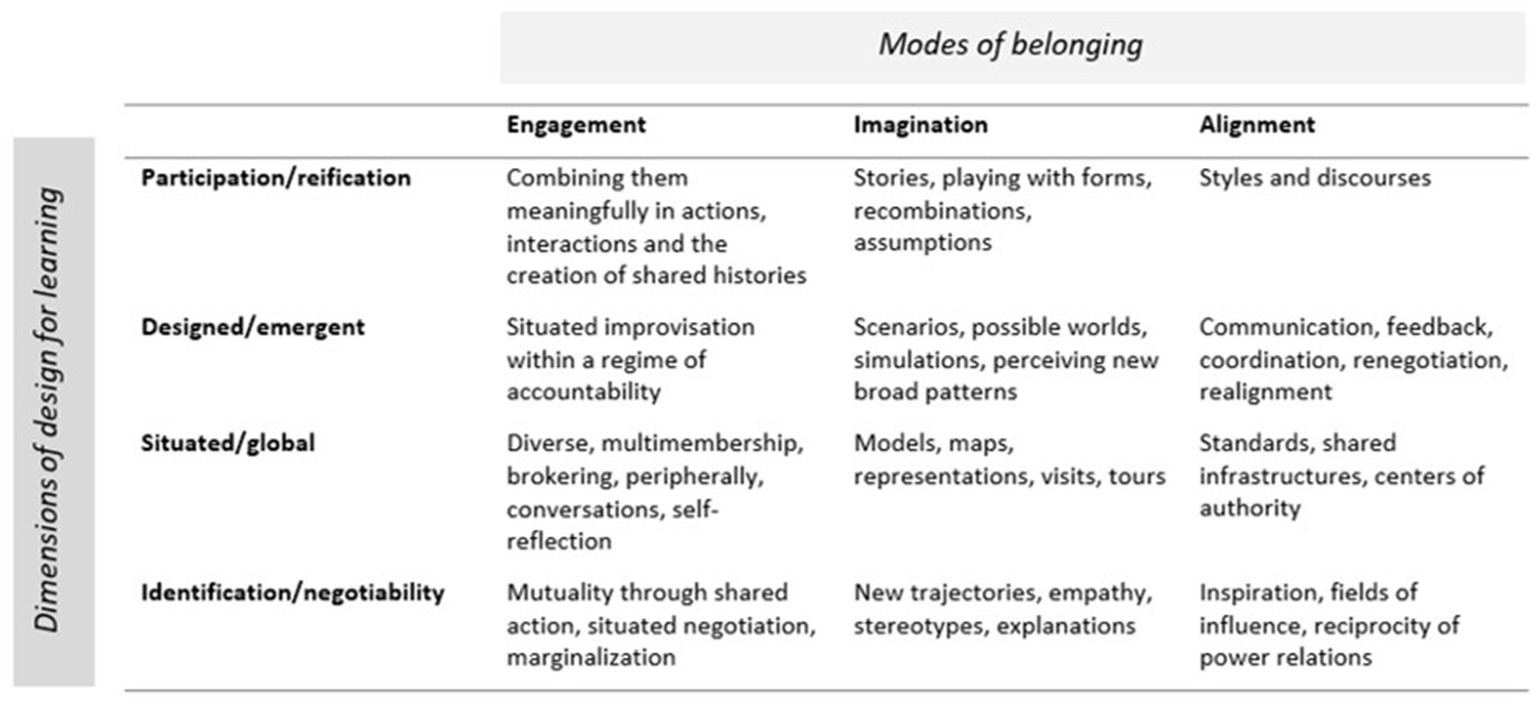

Collective empowerment and social learning cannot be created directly, but they can be “recognized, supported, encouraged and nurtured” through design choices (Wenger, 1998, p.229). Wenger (1998) proposes a framework for designing the conditions for learning which we use in this paper. It is composed of four dimensions of design and three modes of belonging that, together, support the design of a learning architecture (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Articulating components and dimensions of a learning architecture. Adapted from Wenger (1998).

The dimensions of design for learning are conceived as four creative tensions.

2.1.1. Participation and reification

Community members participate in learning conversations, but there is also a need to “reify” periodically the conversations, into blogs, notes, recordings, etc., to provide a concrete expression of the conversations, so that they are not ephemeral and thus lost. Too much reification can reduce space for spontaneity and creativity, too little reification means that valuable insights can be lost.

2.1.2. Designed and emergent

Practice is a response to design, not a result of design. Consequently, design needs to be minimalist, providing enough structure for the community to engage in conversations while allowing room for emergence of new directions and approaches.

2.1.3. Situated and global

All practices are situated in terms of engagement, including the practice of gender-transformative research, even though the issues they address may have global implications. For CoP design this means balancing individuals’ unique experience, knowledge and needs with the “broader constellations in which their learning is relevant” (Wenger, 1998, p. 234). Unlike Wenger, who refers to practices as “local” rather than “situated,” in this paper, and in line with feminist epistemology (Longino, 1993, 2017), we use “situated” rather than “local” practice.

2.1.4. Identification and negotiability

CoP members are united in a focus on developing and using the practice of interest and this provides them with a convening identity. What the practice actually means in theory and concrete terms is “negotiated” emergently for each individual through conversations.

Each of these tensions much be addressed through three “modes of belonging” which are fundamental to designing an architecture for learning. Imagination refers to the shared vision of the future that gender researchers conceive of achieving through their research. In practice, this can take the form of reflection, visioning, and trying new things out in a playful way. Alignment comprises the principles, leadership, routines, discourses, and accounting measures that keep the community on track. Engagement is about providing the infrastructure for interaction, for example directory of members, joint tasks, time for interactions, meetings, opportunities to collectively problem solve.

The GTRM-CoP case study (section 3) employed a “design for learning” approach, making design considerations which are intended to encourage learning by navigating the dimensions and components outlined above.

2.2. Reflexivity as transformative practice

A feminist and critical lens applied to thinking about, planning, implementing, disseminating, and using research in culturally sensitive and context-specific ways increases the chances of catalyzing positive change (Mertens, 2021). Researchers committed to increased social and gender justice can support transformative change by continuously asking themselves a series of questions such as: What is the impact of my work? Is it contributing to increased justice or supporting oppression? What do I need to do in the design of my research to support transformative change and sustainable impact? (See full discussion in Mertens, 2021). There are different ways to engage with these questions.

One way is through the development of a diversity of methods6 for researchers to better understand the root causes of gaps, inequities and biases in their efforts toward social justice and gender equality in the heterogeneous contexts where CGIAR works. A second way is for researchers to consciously include members of vulnerable and marginalized communities in ways that are culturally appropriate while committing to reduce power inequalities, i.e., by adopting a role of co-creators and facilitators of change (Peake, 2017; Mertens, 2021). This recognizes and values them as (co)creators of change while contributing to their empowerment by developing a sense of ownership in the knowledge creation. A third way is via the recognition of and engagement with a diversity of knowledges, whether derived from formal research or situated knowledge, to discuss unequal power relations and hierarchical and neo-colonial scientific constructs – including the validity of gender concepts, methods and methodologies, and, as part of this, to build upon marginalized knowledges through feminist standpoints (Lopez and Ludwig, 2021; Staffa et al., 2022). The ongoing “reflecting and doing” process of the GTRM-CoP embraces these distinct engagements and in so doing aligns with recent feminist thinking and critical insights about the role, responsibility and accountability of the researcher and of their research impacts in neo-colonial contexts (see for instance Istratii, 2020; McAlvay et al., 2021).

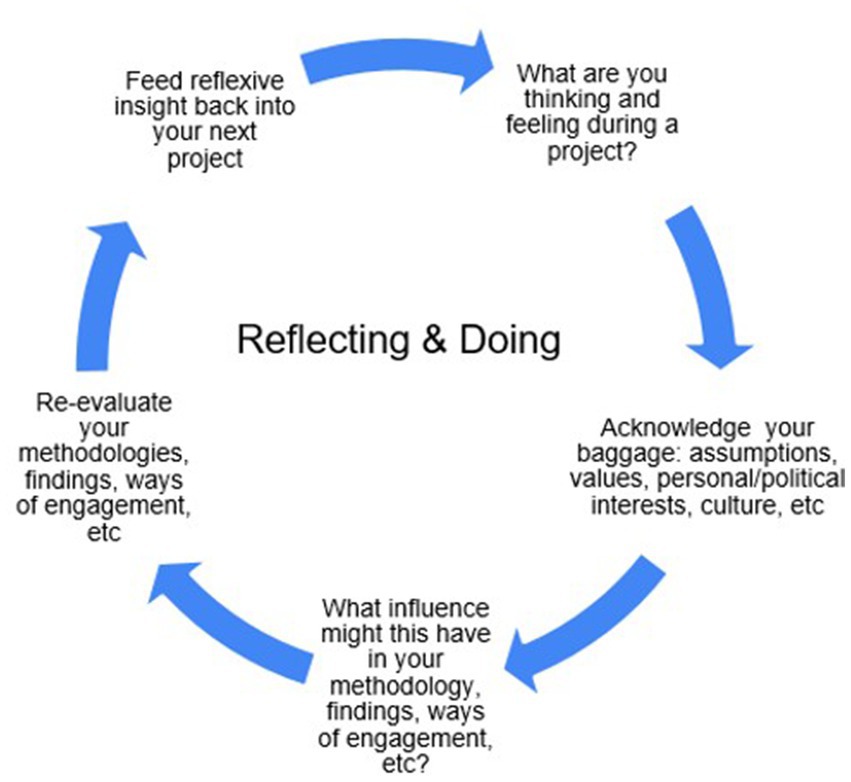

Feminist epistemologies posit that doing research is never value-free. Concepts around positionality and reflexivity are therefore key tools for the critical researchers. Positionality is about how researchers see the world from different sociocultural and geographical locations and perspectives and how a researcher’s lived experience influences their research and knowledge development processes. It is also about being aware of how one’s own biases can affect research processes and outcomes. This leads to the concept of reflexivity, which describes the process of examining oneself as a researcher. Reflexivity induces self-discovery and can lead to insights and new hypotheses about research questions. Yet reflexivity as an end in itself “divorced from the situated power relations within which the researcher operates” can easily become an introspective, academic exercise with no serious intent for action (Peake, 2017, p. 5). With this in mind, an ethos of “reflecting and doing” has been key in the process of applying design considerations in practice to the development of our case study, the CGIAR GTRM-CoP.

3. The CGIAR Community of Practice on Gender-Transformative Research Methodologies

The GTRM-CoP emerged from a bottom-up process led by a large group of researchers across CGIAR centers and beyond, committed to creating the conditions for sustained gender-transformative work. It aims to promote the transformative ambitions of CGIAR, its partners, and interested organizations and individuals by creating safe spaces for innovating, sharing and taking-up gender-transformative research methodologies, and at the same time, building and strengthening the collective empowerment of gender and feminist researchers in CGIAR. The CoP is committed to gender-transformative change processes (Box 1). It aims to contribute to co-creating socially just and gender-equitable futures in food, land, and water systems (Rietveld et al., 2022). The GTRM-CoP emerged from researchers’ experiences with past and present struggles and opportunities to advance, mainstream and consolidate gender and social research across the CGIAR organization for sustainable and equitable impacts of agricultural innovation systems. The following overview of CGIAR and of these processes helps situate and contextualize the work of the CoP.

3.1. Transformation from within: gender in CGIAR

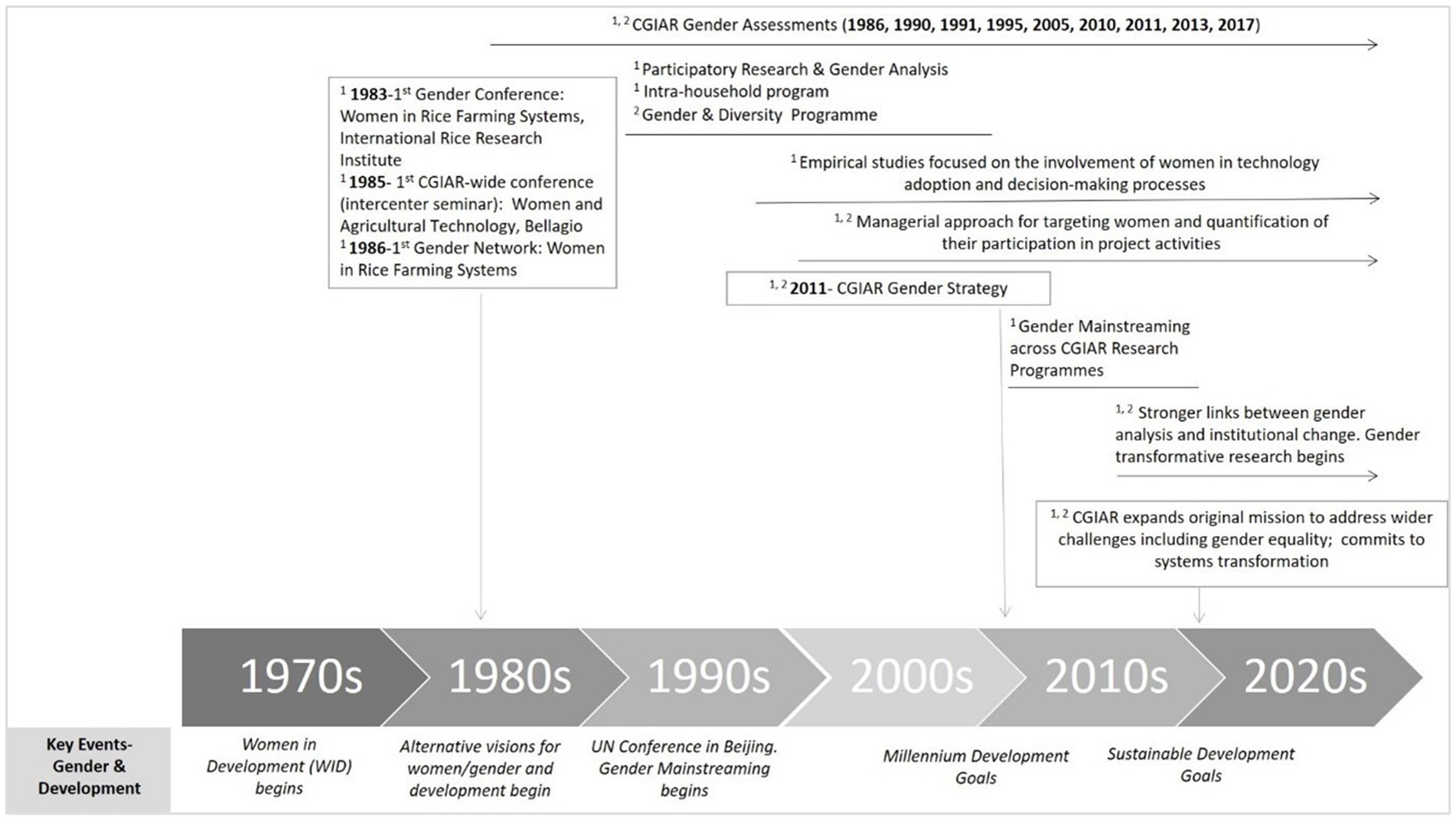

CGIAR is an international non-profit AR4D organization. It represents the world’s largest agricultural innovation network, with over 3,000 partners across 89 countries encompassing national governments, academic institutions, global policy bodies, private companies and non-governmental organizations (Özgediz, 2012). CGIAR is constituted of various autonomous research centers working on agricultural and food policy, crops, livestock and fish, and eco-regional and natural resource management (see footnote 1). Originally established in 1971 with a focus on technological efficiency and productivity for agricultural transformation, over the years CGIAR has expanded its emphasis beyond efficiency and productivity to include gender equality (Özgediz, 2012; Van der Burg, 2019). CGIAR began to engage with gender issues in the 1980s with individual centers addressing gender in different ways (see Sarapura Escobar et al., 2017; Van der Burg, 2019). Since then, understandings of gender and gender equality have changed and expanded across CGIAR centers, albeit unevenly and without the development of a shared consensus of what this means in terms of research theory and practice. Broadly, though, there has been a shift away from an emphasis on women’s access to resources and the gender division of labor toward more transformative perspectives with a focus on achieving structural change in the underlying normative structures which reproduce gender and social inequalities, toward more gender and social equality (Quisumbing et al., 2014; Van der Burg, 2019). Figure 2 provides a historical overview of the most prominent gender-related events and programs within CGIAR (see also Lopez, 2022).8 We discuss a few of these, which were specifically influential, below, illustrating how similar issues and challenges keep (re-)emerging over the past few decades.

Figure 2. Historical overview of most prominent gender-related events and programs within CGIAR. Source: authors.

An important attempt to institutionalize gender came with the Participatory Research and Gender Analysis (PRGA) Program which was established as a CGIAR Systemwide initiative in 1997. It promoted the use of gender-sensitive participatory research approaches within CGIAR and its partners. A review highlighted its many successes but noted a key challenge as well, i.e., the need for more (management) support, tools and funding (see Alvarez et al., 2010). Another study (see Farnworth et al., 2007) discussed the frequently paternalistic attitude of technologically-oriented organizational cultures, including CGIAR, toward those they represent as the beneficiaries of their technologies, with agricultural science being viewed and advanced as “rational, objective, rigorous” and in opposition to “the notion of social constructivity of knowledge and reality” (Farnworth et al., 2007, p. 34). In organizations like CGIAR, non-economic social scientists note that speaking the “right language” means doing the “right kind of science”—i.e., doing quantitative rather than qualitative research (Farnworth et al., 2007, p. 35). As such, deviance from the right language meant that social scientists struggled to develop women’s equality, gender and social equity as legitimate topics for discussion, and which they considered are pivotal to the achievement of CGIAR’s mandate—including its biophysical elements. Gender scientists interviewed for the study saw themselves as radicals, trying to achieve vitally important change from within, and argued this was a lonely place to be. Following the Farnworth et al. (2007) study, which highlighted how patterns of inclusion and exclusion characterize CGIAR culture, a study by Kauck et al. (2010) noted organizational constraints, including the influence of organizational values, on gender research in CGIAR. This study acknowledged the numerous “strategic gender initiatives” across the organization which “demonstrated instances of excellence and innovation in incorporating gender analysis in agricultural technology [research and development].” However, it regretted the lack of “a robust, properly resourced and supported effort to embed gender analysis across CGIAR” (Kauck et al., 2010, p. 7). The study’s findings contributed to a concerted effort to mainstream gender across the organization in the new CGIAR Research Programs which started in 2011 (CGIAR Consortium Board, 2011). CGIAR’s institutional commitment toward gender equity (in the form of budgeting, capacity building, skills development, and monitoring and evaluation mechanisms) thus opened spaces for contestation and change—including an enhanced gender research agenda (Arora-Jonsson and Sijapati, 2018).

The enhanced scope of gender research in CGIAR over the last 12 years has been evidenced by the use of analytic (and political) feminist frameworks such as performativity (e.g., Badstue et al., 2021), Feminist Political Ecology (e.g., Elmhirst et al., 2017), intersectionality (e.g., Colfer et al., 2018; Tavenner and Crane, 2019), and the exploration of normative dimensions of gender (e.g., Elias et al., 2018; Lopez and Ludwig, 2021; Rietveld et al., 2022) as well as support for research initiatives that aim to catalyze gender transformations both within and beyond CGIAR (see for instance, Morgan, 2014; Cole et al., 2020). The emphasis on gender-responsive approaches was supported by some of the CGIAR Research Programs (CRPs; 2011 to 2021) while gender-transformative approaches were an institutional priority for the CRP on Aquatic Agricultural Systems (2011 to 2013). Important gender work developed during the CRPs period including investigation into gender in breeding (Ashby and Polar, 2019), gender and social inclusion in climate change, agriculture and food security (Huyer, 2016), systemic change in gender relations in aquatic systems (Cole et al., 2020), indices to quantify gender gaps in empowerment and impacts of agricultural development programs (Galiè et al., 2019; Malapit et al., 2019), measuring transformative change (Morgan, 2014), and inclusive scaling of agricultural innovations (McGuire et al., 2022). While gender research and methods focusing on the identification of gender gaps had previously dominated gender work in CGIAR, since the 2010s, as shown in Figure 2, gender-transformative approaches seem to be gaining momentum—albeit they continue to be relatively few and fragmented.9

As part of the “One CGIAR” reform—and despite gender equality, youth and social inclusion been one of CGIAR’s five core impact areas (CGIAR System Council, 2019)—gender is, again, addressed very differently and unevenly across the current cross-center CGIAR Research Initiatives (see footnote 2) with few pursuing a gender transformative agenda. This means that the three historical challenges of gender research previously described are still relevant today, with gender research continued to be underfunded; scarce appreciation for and willingness to understand social science epistemologies in CGIAR work; and fragmentation and isolation of gender research in the organization. To partially address this, a new CGIAR gender research architecture has been developed and consists of multiple axis: a CGIAR gender impact platform, a cross-center research project focused on gender equality and social inclusion across agri-food systems, and gender teams and individual researchers working in other CGIAR projects and initiatives contributing to gender impact.

All gender teams and researchers contribute to the Platform, and many are involved in the gender equality and social inclusion initiative. Despite these efforts, CGIAR gender research is a long way to go, especially for a transformative change in agri-food systems, leading to more sustainable and equitable impact. This is also reflected in a recent study commissioned to understand the capacity and needs of CGIAR gender research: “To successfully embed and center gender in CGIAR’s operations and approaches, all staff members—finance, operations, human resources, scientists—must be committed to and engaged with gender-responsive initiatives, rather than relegating this work to gender specialists alone… and displayed organizational commitment to gender transformation” (Zaremba et al., 2022, p. 13). To make it happen, gender research should go beyond “check boxing” for donor requirements and the fragmented and piecemeal approach to gender should step up by dedicating adequate financial and human resources for more strategic and integrative gender research (see also Travis et al., 2021).

3.2. Toward the GTRM-CoP

One influential initiative for catalyzing critical reflections toward how to conduct gender-transformative research in CGIAR and fostering social capital among gender researchers was GENNOVATE (2014–2018).11 GENNOVATE was a global comparative research initiative that addressed the question of how gender norms and agency influence men, women, and youth to adopt innovation in agriculture and natural resource management. Principal investigators from eight CGIAR centers conducted a total of 137 case-studies across three continents and 26 countries. While GENNOVATE was primarily focused on describing and understanding gender gaps in innovation, it prompted a series of reflections on how to advance more gender and socially equitable research. Importantly GENNOVATE created physical and virtual meeting spaces where gender researchers met regularly to share ideas and to co-write articles. GENNOVATE researchers considered this experience helped them to reduce their sense of isolation and to be generally empowering (CGIAR-IEA, 2017; Elias et al., 2018)—as well as resulting in a large number of solidly researched scientific publications.12

The GENNOVATE experience and connections between gender researchers led, after the initiative ended, to a self-selected group of these individuals wanting to continue their critical reflections, community and research collaborations. The GTRM-CoP developed from these critical discussions and, partially, also as a reaction to the three historical challenges of gender research in CGIAR. The current members of the GTRM-CoP profited from the current gender architecture to ensure the CoP became an established and funded space for gender-transformative research across CGIAR centers. The CoP is situated within the Methods module of the CGIAR gender impact platform.13

4. The GTRM-CoP “reflecting and doing” process

The GTRM-CoP is guided by a “reflecting and doing” process based on feminist thinking and critical insights generated from recent debates about the role of the researcher and research impacts. Here we outline the design considerations we used when designing the social infrastructure of the GTRM-CoP in order to maximize the possibility that members will continue to engage in “reflecting and doing” beyond the regular online meetings held by the CoP. We employed an approach based on CoP “praxis,” i.e., theory embedded in practice, using community of practice theory to guide design decisions.

4.1. Defining the scope of the CoP

The definition of the GTRM-CoP emerged from 2020 onwards through discussions held online and through hybrid workshops among a self-selected group of GENNOVATE researchers together with a broader group of invited researchers and practitioners committed to gender and social equality. Participants decided to both build on GENNOVATE and to move away from it to strengthen a gender-transformative research agenda within CGIAR. The initial SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) analysis showed that, first, while GENNOVATE data and associated publications had exponentially increased understandings of gender norms and processes of normative change across many agri-food systems and geographies, there was discomfort that rural research participants and national research partners had not necessarily been empowered by their participation. It appeared that international staff were the primary beneficiaries of the research process. Second, discussants shared a concern for potential harm for the rural communities where CGIAR works when gender research, and gender-transformative approaches, are implemented superficially. Third, participants were concerned lest the momentum, critical thinking and approaches developed through GENNOVATE be lost in the One CGIAR reform process.

Over the course of a 3-day hybrid workshop held in October 2021, the idea of continuing to develop a gender-transformative research praxis emerged and began to coalesce around three elements (see full discussion about the CoP set-up, ambitions, goals, principles and structure in Rietveld et al., 2022):

• Domain: improving gender equality and social equity.

• Practice: understanding, developing, testing and using tools and methodologies for gender-transformative research, and gathering evidence with and about the methodologies.

• Community: researchers who are passionate about and committed to exploring and understanding gender-transformative change, centered around—but not exclusive to—CGIAR.

4.2. Design considerations

Over the ensuing year, a group of research practitioners worked to design the “social infrastructure” to create the conditions for learning and doing gender-transformative research—this group includes the five authors of this paper who act as core convenors of the CoP. There are nine design considerations: (1) enabled learning, (2) composition and size of the community, (3) leading and guiding the topic groups, (4) adding value to the participants’ everyday work, (5) amount of work and level of engagement, (6) generating momentum, (7) technological infrastructure, (8) being flexible and adaptive, and (9) creating an atmosphere for engagement.

The design consideration (1) was the level at which learning would be most enabled. The group felt that the topic of “gender-transformative research methodologies” was too broad to operationalize. What did it mean in practice? The group wanted to develop and adopt research methodologies in novel ways to explore topics such as masculinities and intersectionality in order to underpin normative transformational societal change toward greater equity and social justice. They also identified a need to be reflexive about the research processes and data generated, including around local actors’ and communities’ ownership and access to data. Other needs identified included further development and application of the tools and data developed during the GENNOVATE project, and to understand better the potential for transforming gender norms in and through institutional and organizational change. Based on this, an initial list of five “topic groups” (co)convened and (co)facilitated by CGIAR and non-CGIAR staff were suggested: (i) gender-equitable masculinities, (ii) intersectionality, (iii) transformative research processes and data, (iv) mobilizing GENNOVATE data and tools, and (v) organizations and institutions (see details in Rietveld et al., 2022).

The level of the topic groups is strongly linked to their objectives, and this in turn influences the design consideration (2): the composition and size of the desired community. In the case of the topic group on transformative research processes and data, the format is one of different experts providing food for thought and a subsequent discussion. It was not considered that there was a need to constrain the group size, so monthly meetings are open to all gender researchers of CGIAR and invited guests beyond CGIAR including from think tanks and academic institutions. For the intersectionality topic group, a particular aim was to offer participants the opportunity to share their work in progress with colleagues for constructive feedback, in a “clinic” format. For this reason, there was a design decision to limit participation to a small intimate group for the time being to help foster the conditions needed for critical and reflexive conversations to take place.

Design consideration (3) was to identify the “energy” to lead and guide these topic groups. While topics might be ideal from an analytical point of view, if there is no emotional commitment or enthusiasm to engage and lead it is difficult for a CoP to succeed. Following (Ison, 2010), the group sought to trigger enthusiasm as an emotion, which can lead to purposeful action, and as a methodology—a way to orchestrate purposeful action.

Reaching out to potential community members, the group discovered that there were people enthusiastic enough to co-lead only four of the identified five topics, and so the group removed one topic (organizations and institutions) to focus energy on where enthusiasm could hopefully result in purposeful action.

In order to maintain and increase the resource of enthusiasm for purposeful action, it is important that the GTRM-CoP as a whole, and the topic groups, add value to participants’ daily work, and that the value is commensurate with the amount of engagement and work required. This was, thus, design consideration (4). There are different aspects to how value can be understood. Wenger et al. (2011) identify five sources of value for Communities of Practice which are useful for gauging the value that CoP members are currently obtaining or could obtain from membership. They range from “immediate value” (finding a group you identify with for example), through “potential value” and “applied value” to “realized value” (realizing an improved “performance” as a gender-transformative researcher), and even “reframing value” (allowing new visions of success and a chance to change direction). All five values can be created simultaneously. The activities to be developed in the topic groups of the GTRM-CoP have been agreed through discussions with members regarding their needs and aspirations. This is considered to provide a solid basis for value creation.

In order to ensure the planned activities would create value for members, the first step for the topic groups was to understand members’ needs and design the community around meeting those needs. In the case of Intersectionality, the topic group took advantage of an in-person meeting in which CGIAR colleagues had brainstormed the challenges of conducting intersectional research. Clustering these challenges into themes provided material for a series of intimate, small monthly meetings on addressing these challenges. In the case of the topic group on transformative research processes and data, the co-convenors invited all interested parties to an initial online meeting where they used an adapted version of “Outcome Mapping” progress markers which asked participants what they would expect, like or love to see the community achieve in the coming year (i.e., in 2023). Such progress markers are useful in a situation of uncertainty where inputs (people’s time) are unpredictable. They allow the community to establish a lowest level criterion of success (expect to see), which is the minimum that might constitute progress. Like to see represents achievable goals if all goes well. Love to see highlights probably unattainable goals, but nevertheless act as a “north star” attractor to guide the direction of activities. In the topic group meeting, participants established their expectations and a set of guiding principles. They also proposed what they would be willing and able to contribute to the community. These inputs formed the basis of a “Discussion Series” which comprises CGIAR and non-CGIAR speakers and facilitators. An interactive workshop between representatives from Ghanaian NGOs and local communities with gender-transformative experience, and gender researchers to explore mutual learning and better ways of working together in meaningful and horizontal ways is currently being planned.

The other side of the value–inputs equation is the amount of work and engagement that CoP members need to put in, i.e., design consideration (5). This “logistical grind” (see Iaquinto et al., 2011), including updating mailing lists, organizing meetings, acting as the contact for members suggesting discussion topics, communicating relevant issues to the group and encouraging participation in meetings is best taken on by a community coordinator. In the case of the GTRM-CoP the second author of this paper takes on this role in partnership with “content coordinators” who act as “sources of explicit knowledge by searching, retrieving, transferring and responding to members’ knowledge requests” (Iaquinto et al., 2011, pp. 17). Each topic group has its own organizing group of between three and five content coordinators who are also the co-convenors. These share the role of providing, facilitating and encouraging gender-transformative research expertise.

Research on CoPs show that they need to establish a heartbeat (design consideration 6) in order to generate the momentum needed to underpin the exchanges and learning. The co-convenors of topic groups as well as the CoP core convenors agreed to hold meetings regularly, allowing enough time between them for reflection and action, without losing the momentum between encounters. Importantly, each topic group agreed that, rather than imposing a standardized modus operandi across topics, the different topic groups were to agree upon and follow their own pace and rhythm to further contribute to a sense of collective empowerment. The convenors also agreed to have periodic stock-taking exercises to compare and build on each other’s experiences and insights.

The design consideration (7) was the technological infrastructure to support exchanges between participants. The core group followed Wenger et al. (2009), who advise that the level of technology to adopt should follow the community’s needs and comfort with technologies. GTRM-CoP members are familiar with working through email, and conducting video meetings using Microsoft Teams and Zoom. These were therefore adopted as the main tools to support the community. However, there is also a need to capture and “reify” conversations so that can be referred to by others or at a later date. For this reason, using the corporate suite of tools commonly adopted at CGIAR (Microsoft Office), the CoP built a simple.

Sharepoint as a repository for meeting notes and recordings. This allows topic groups to follow what is happening in the other topic groups, permits existing members to catch up on missed conversations, and enables new members to easily catch up on the “repertoire” of shared history and conversations. Additional functions in the Sharepoint include a directory of members and a library of key resources for each topic group.

Design consideration (8) is local adaptation. Already, after 8 months of implementation, the topic groups are taking different “design turns” within the guiding parameters of “improving the practice of gender-transformative research methodologies.” Each topic group is generating a unique learning trajectory, emerging from the interactions of the individual members’ enthusiasms, needs, knowledge and experience. Individuals across the four topic groups have different starting points in terms of years and types of experience. For instance, in the topic group on Intersectionality the starting point is that there are many pockets of expertise which can be surfaced, shared and discussed. The need for external inputs is therefore lower than in the group on masculinities, where expertise is generally lower. In the first group, progress and learning can be achieved through conversations and sharing; in the second group, identification and invitation of external expertise is needed to kickstart the learning trajectory.

Similarly, the direction of the learning trajectory differs by topic group. The topic groups have set their own objectives for what they want to achieve, reflecting their own enthusiasms and needs. In the case of Intersectionality, the objectives are centered on action. Participants explore deep challenges in addressing intersectionality in gender-transformative research methodologies and practice, including identifying which intersectional identities to work on and who to work with, sampling size, and scaling. Real-life case studies focused on on-going research planning and emerging—and often complex—fieldwork findings are discussed. For the topic group on transformative research processes and data, the primary focus is on understanding the current research landscape and its opportunities—who is doing what, the concepts and frameworks being used and their potentials and limitations, lessons already learned, unmet needs—to inform research praxis as well as ensuring that this very process contributes to the personal and professional transformation of topic members by encouraging continuous (individual and collective) reflexivity and a commitment to decolonizing gender approaches to development and research.

The final design consideration (9) is creating an atmosphere for engagement. Following Bailey (2017), the Intersectionality topic group started by establishing principles by which they agreed to work to set solid foundations for conversations (Box 2). These include establishing a “half-open door to participation.” This resulted in setting the boundaries of the group to ensure a small enough group for trust building and reflexivity among active participants.

BOX 2. Design principles for intersectionality topic group working together.

- Bring your half-baked ideas. It is a learning space. Mistakes, naïve questions and knowledge gaps are welcome here.

- Participation is a gift to the other community members. Leverage what you know. Share it out—educate your colleagues, help someone, mentor someone with lower competence.

- Where we go depends on you. All members have responsibility for contributing to what they would like to see as the value of the CoP.

- We have a half-open door to participation—in the core group only people who want to contribute actively. Other people are welcome in wider activities.

- We may have different kinds of spaces for different groups of people.

5. Discussion and conclusion: reflecting on doing

Our design decisions taken so far reflect the Wenger (1998) framework (four dimensions and three modes of belonging in Figure 1), as well as the feminist and critical ethos of “reflecting and doing” to guide the development of the GTRM-CoP process.

Engagement is key. This is seen in the focus of the conversations on applying skills and jointly devising solutions to shared research challenges. Emergence of engagement is fostered through design decisions around identification of strategic topics and of considerations of the right group size to reach different objectives. The self-identification of topic group co-convenors, based on their self-professed enthusiasm, taps into their identity and their negotiation of what it means to “be” a gender-transformative researcher and to “do” gender-transformative research. The major force for engagement is the connection between the situated interactions in the CoP and the situated experiences of researchers in their diverse research projects. These provide a rich ground for negotiating meaning and for critical reflexivity.

Reification of the conversations is secured through recording and saving all meetings. This contributes to the beginnings of a shared learning trajectory for each group, which rests onto the topic group members, but overall contributes to the GTRM-CoP. This is reinforced through co-convenors, in the Intersectionality core topic group, for example, discussing the efficacy of each meeting immediately upon its conclusion in relation to how learning appears to be occurring, and the co-convenors meet regularly to engage in reflexive discussions. A Sharepoint site, Dgroup and online meetings provide the physical spaces for storing emergent conversations.

The imagination function is catered for through the visioning Outcome Mapping progress markers, providing an image of a desired future for group activities, and generating a creative tension between current identities and the negotiation of future meanings. It is also seen in the periodic sense-making sessions. These serve to reify group reflection and compare discussion processes across the different topic groups, thus imagining different trajectories (“doing” element). In the Intersectionality group, for example, an intentional effort is being made to create a playful space where members feel comfortable to try out methods and imagine different ways of “being” a gender-transformative researcher. Through group meetings, members are given virtual visits to other members’ research contexts, thus connecting their local experiences through imagination with the wider world of gender-transformative research methodologies.

Alignment is provided through the establishment of a schedule of meetings, periodic feedback and sense-making and the provision of guidelines and principles by which to work, connecting the situated to the global. Gender-transformative researchers use and develop a shared discourse, which is a form of reification of their participation. Coordination and feedback mechanisms provide the design space for emergence of new topics and desired futures.

More broadly, this paper has explored the potential of CoPs as social learning systems to create the conditions for transformation-oriented learning. Specifically, we try to shed light on how transformation can happen from “within self” gender researchers if they are aware of what, how, why, and for whom they are doing gender research. By dissecting gender-transformative research and methodologies into different topic groups focusing on multiple dimensions of transformation—be it intersectionality, masculinity, transformative research processes and data, or GENNOVATE data and tools—the paper presents the GTRM-CoP as an open space to discuss, debate, and bring the agenda forward and beyond CGIAR discussion spaces. The GENNOVATE data and tools topic, for instance, was originally designed for CGIAR purposes. However, due to the rich knowledge generated, its scope of research and its seminal contribution on bringing social norms in agri-food systems into the academic discussion, it is expected that gender-transformative methodologies derived from this topic will have a wide range of readership and application in gender in AR4D and in gender norms theory and practice more broadly.

While the overall goal of this paper is to introduce this CoP as a case study that incorporates a feminist ethos of “reflecting and doing” from designing, experimenting, and learning, we have particularly focused on the designing aspect of it. The experimenting and learning aspects will deepen as we gain some more understanding on practicalities on transforming from “within self”—following the praxis of gender-transformative research. This CoP will promote reflexivity through ensuring discussion processes are iterative and transformative. It will track researchers as they challenge their own values and assumptions about what it means to work on gender transformative research in CGIAR. Because the CoP is an ongoing process, this is an evolving matter. In the last month, for instance, the CoP members have agreed to make more punctual efforts to track change, including by documenting the discussions and how these influence gender researchers’ thinking processes and practices and by systematically identifying and sharing ongoing gender transformative practices across the CGIAR projects. For instance, the topic group on transformative research processes and data, has recently committed to develop a living resource to help researchers (1) identify (common) good practices for gender transformative research; (2) present real cases across regions and agrifood systems to contextualize, adapt and (if possible) standardize such practices or explain why they cannot be generally applied; and (3) feed a list of critical research questions—including about the concepts, methods and ways of engagements used, the assumptions and values behind them, and their actual need and benefit for diverse stakeholders and communities—to ensure that the feminist and critical ethos of “reflecting and doing” is maintained. The latter is particularly tough as there is an intention to set “recurring critical questions” such as those posed by Mertens (2021) and others, e.g., what is the impact of my work? Is it contributing to increased justice or supporting oppression? What do I need to do in the design of my research to support transformative change and sustainable impact? Who is being transformed in the process and to what ends? How can GTAs be pursued in ways that are not paternalistic and are sensitive to local context (i.e., aligned with the social transformations that project participants would like to see and not just extensions of technocratic agendas). See Figure 3 as an example of how this can contribute to strengthen a project. In parallel, the “Discussion Series” will be adapted to ensure that reflexivity is embedded in future presentations and informal discussions. This ambition emerged as a result of a recent “stock-taking and reflection sessio” where participants collectively acknowledged that, as any other feminist initiative in organizational setting dominated by patriarchal, positivist and techno-centric values, GTAs and its associated methodologies run the risk of becoming instrumentalized, diluted and co-opted. The ongoing CoP “reflecting and doing” ethos, a constant exploration of varied theoretical and methodological frameworks, people-centered ways of engagement, and researchers’ openness, humility, creativity and continuous efforts are helpful to mitigate some of these risks.

Even at this initial designing stage, the case study shows the potential of a CoP to create a safe and innovative space for gender researchers committed to a feminist agenda for gender-transformative change while also contributing to building and strengthening a collective sense of empowerment among (often isolated) gender researchers. This is important especially within an organizational culture such as that of CGIAR where the adoption of a gender-transformative agenda that embraces a feminist, critical and decolonial viewpoint can be challenging.

The CoP has only been “live” for 8 months so it is premature to assess success or failure—which is also not the goal of the paper. The topic groups have got off to a good start evidenced by the levels of interaction and enthusiasm in the meetings so far. In terms of to what extent the GTRM-CoP is creating a space within CGIAR for gender-transformative research, we can identify elements that are indicative of early promise of success, as well as potential challenges.

First, the community emerged from a bottom-up process led by researchers within and beyond CGIAR who are committed to set the conditions for gender transformative research, and it involved other gender researchers in the CoP development process from an early stage. This is crucial because it also means that there is a collective sense of ownership that will likely contribute to the CoP’s success as members interact to establish and meet their own self-identified needs. Second, the community is building on the strong foundations of critical feminist research methodologies kickstarted by GENNOVATE. However, one challenge will be to make sure that the groups retain an action focus and do not become “talking shops.” To this end, it will be important to establish learning processes between topic groups, and see which approaches, group sizes and meeting designs foster a turn toward applying GTRM in members’ research. It may be necessary to institute “clinic” type meetings for that, or use buddy systems to achieve the optimum mix of private and public, small and large encounters to foster the conditions for experimentation and feedback. As the practice of each group unfolds, they will become more free to make their own pathways and future trajectory as options emerge from conversations and experiences.

Regarding future scaling out from the initial groups to influence the wider CGIAR practice, this is rather a grand ambition. While the CoP members are not necessarily aiming to transform the entire CGIAR, we can envision leverage points for getting many of the emerging ideas into “good currency.” One is via multiple membership. The members of the GTRM-CoP hail from different CGIAR centers and beyond. They work in different projects with different project teams. The fact that the same individuals are having conversations on theory in one or more topic groups and then working in practice on one or more projects, thereby meeting and re-meeting the same individual in different permutations, offers very rich ground for cross-learning and for new knowing to emerge. Another leverage point is joining forces at strategic moments with other communities of interest and practice across CGIAR. There are researchers converging on topics of interest such as decolonizing research and human-centered design, which offer enough commonality to work collectively on new ways of conceptualizing and implementing the research process.

Based on the CoP’s current discussions and interactions, it is expected that there will be a generation of critical-emancipatory gender knowledge by engaging with conflict and difference, interrogating positionalities and power relations through reflexivity, and by building upon marginalized knowledges via feminist standpoints. Through this CoP, we intend to encourage and create the conditions for researchers to critically (and continuously) examine the impact of their work to avoid complicity in continuing an oppressive status quo and, instead, make contributions toward increased justice. This CoP is built on the belief that a continuous “reflecting and doing” mindset propels researchers to look beyond difference, to build feminist and other types of coalitions, to negotiate and utilize the tensions generated through continuous exchanges with different AR4D stakeholders in a transdisciplinary way in an attempt to generate a type of knowledge that is relevant and novel to the gender field and that, at the same time, recognizes the arduous historical efforts of feminists and others in CGIAR and elsewhere to advance women’s and gender concerns in the AR4D sector. Boxes 3, 4 provide two examples of positive outcomes of gender transformative research and methodologies.14

BOX 3. Example of a gender transformative research process.

Carnegie et al. (2019) is an example of a transformative research process that a group of diverse stakeholders, including Australian researchers, partner organizations and communities in Fiji and the Solomon Islands, undertook as they coproduced a methodology for community-based indicators of gender equity. Kickstarted by critical reflections on the role of economic incentives as the dominant pathway to women’s empowerment and gender equity, the researchers sought to explore alternative viewpoints. Eventually, they opted for a mix of participatory, feminist, diverse economies and strength-based approaches to co-design a research methodology and indicators more attuned to local women’s and men’s lives. The resulting indicators were grounded in local meanings and realities, included distinct ways of participating, and encompassed important relationships across all spheres of life—including the non-economic. The indicators were useful for the different stakeholders including community members, who could use them to identify aspirational goals for gender equity. They also provided an opportunity for community members to pace, track and measure their own progress toward these goals in ways that were coherent with their own customs and social dynamics, while the researchers managed to capture such progress to inform policymaking and to share their lessons and methodology with the research community (Rietveld et al., 2022).

BOX 4. Example of gender-transformative research methodologies on masculinities.

WorldFish developed a gender-transformative approach to address gender constraints within a project aiming to reduce post-harvest fish loss in the Barotse Floodplain, Zambia. It developed a gender-transformative research methodology using drama skits, embedded within an action research process. The drama skits aimed to build critical consciousness among women and men around gendered performances of masculinities and femininities. The focus was on creating a critical consciousness of unequal gender norms, gender restrictive masculinities, attitudes and power relations at community and other levels. Consequent monitoring, evaluation and learning found that women became empowered through the process. A large percentage of fishing gear ownership shifted from men owners only to joint ownership with their spouses. Women reported having significant input on decisions about how to spend fisheries income, on which they previously had little influence. The researchers conclude that challenges underlying post-harvest fish losses are technical and social in nature. However, technical innovations are more successful when they develop methodologies which “explicitly challenge and seek to address prevailing unequal gender norms, attitudes, and power relations. By tackling the technical and social constraints in value chains in tandem, small-scale fisheries have greater potential to contribute toward enhancing the food, nutrition, and economic security of all people who depend on their natural resources” (Cole et al., 2020, p. 60; Rietveld et al., 2022).

Significantly, this paper has shown that the existence of the GTRM-CoP is already an achievement. In many ways, the CoP has provided one of the few institutional spaces in CGIAR that allows gender researchers to be critical, to express and voice their concerns, wishes and aspirations and that helps them to engage in diverse dynamics via innovative ways of thinking about and working on gender in AR4D. These interactions, as well as the knowledge and experiences being generated in the CoP, constitute an informed starting point for the development of initiatives that can tackle the root causes of gender and intersecting social inequalities, avoid/mitigate negative consequences of gender research, and offer ways of intervening that seek to aid, promote and sustain gender and social justice. We expect that the next episode of this effort, where we will present the experimenting and learning aspects of this CoP, will shed more light on practicalities, learning and scaling of gender-transformative research and methodologies in AR4D, and will contribute overall to the gender and development field.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

DL led the planning, drafting, and completion of the paper. AB led the planning and drafting and provided conceptual and experiential insights on social learning systems and communities of practice. CF provided conceptual insights on organizational culture in the CGIAR and provided input to the writing, reviewing, and editing. AR and HG provided input to the writing, reviewing, and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The authors declare that this study received funding from the CGIAR Generating Evidence and New Directions for Equitable Results (GENDER) Impact Platform. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication. The GTRM-CoP is supported by the CGIAR Generating Evidence and New Directions for Equitable Results (GENDER) Impact Platform.

Acknowledgments

The authors, who are enthusiast members and core convenors of the CGIAR Community of Practice on Gender-Transformative Research Methodologies (GTRM-CoP), are grateful for the critical input received as well as for the continuous support and commitment of all the members of the CoP. We would like to thank all funders who supported this research through their contributions to the CGIAR trust fund (https://cgiar.org/funders).

Conflict of interest

AB and AR are employed by Bioversity International, and HG is employed by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), both CGIAR centers.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

2. ^https://www.cgiar.org/research/cgiar-portfolio/

3. ^The GTRM-CoP is hosted within the CGIAR Gender Impact Platform, see: https://gender.cgiar.org/.

4. ^To “reify” (from the Latin noun “res” meaning “thing”) means to make something abstract into something concrete “the freezing of knowledge in a concrete artefact” so that it is captured and able to be shared with others (Polin, 2010, unpaginated).

5. ^A “convening call” is a motivation for collective action, a call for action which resonates with many people and encourages them to convene to that end.

6. ^Including qualitative, quantitative, mixed and other method such as those based on art, see, for instance, Farnworth et al. (2022).

8. ^The figure was developed based on publicly available CGIAR reports and institutional documents as well as previous works about gender history in CGIAR including the most comprehensive work to date on this matter, i.e., van der Burg (2019).

9. ^For in-depth analyses of how gender has been historically integrated across distinct AR4D research orientations (i.e., yield/product, production system, socioecological system) in the CGIAR and across centers following a particular orientation, see van der Burg (2019, 2021).

12. ^See https://gennovate.org/publications/.

13. ^The Platform is organized in three modules: synthesizing evidence (Evidence module), fine-tuning and developing methods and tools (Methods module), and supporting networking for gender research (Alliance module).

14. ^See other examples in Rietveld et al. (2022) and Drucza and Wondimu (2017).

References

Alvarez, S., Rivas, S., Simone Tehelen, B., García, K., Ximena, C., Manners, G., et al. (2010). Demand analysis report: gender-responsive participatory research. Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (CIAT), Cali, CO. 43 p.

Anderson, S., and Sriram, V. (2019). Moving beyond Sisyphus in agriculture RandD to be climate smart and not gender blind. Front Sustain Food Syst 3:84. doi: 10.3389/FSUFS.2019.00084/BIBTEX

Arora-Jonsson, S., and Sijapati, B. B. (2018). Disciplining gender in environmental organizations: the texts and practices of gender mainstreaming. Gend. Work Organ. 25, 309–332. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12195

Ashby, J. A., and Polar, V. (2019). “The implications of gender relations for modern approaches to crop improvement and plant breeding,” in Gender, agriculture and agrarian transformations. (Routledge), 11–34.

Baden, S., and Goetz, A. M. (1998). “Who needs [sex] when you can have [gender]” in Feminist visions of development: gender analysis and policy. Eds. C. Jackson and R. Pearson (London), 19–38.

Badstue, L., Farnworth, C. R., Umantseva, A., Kamanzi, A., and Roeven, L. (2021). Continuity and change: performing gender in rural Tanzania. J. Dev. Stud. 57, 310–325.

Bailey, A. (2017). Can CoP theory be applied? Exploring praxis in a Community of Practice on gender communities of practice in development: a relic of the past or sign of the future? Knowl. Manag. Dev. J. 13, 60–76.

Bawden, R. (1995). Systemic development: A learning approach to change. Centre for Systemic Development, University of Western Sydney, Hawkesbury, Occasional Paper No. 1.

Carnegie, M., McKinnon, K., and Gibson, K. (2019). Creating community-based indicators of gender equity: A methodology. Asia Pac. Viewp. 60, 252–266. doi: 10.1111/apv.12235

CGIAR Consortium Board. (2011). Consortium level gender strategy. Available at: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10947/2630/Consortium_Gender_Strategy.pdf?sequence=4

CGIAR System Council. (2019). One CGIAR: A bold set of recommendations to the system council. CGIAR 9th meeting in Chengdu, China (13–14 November). Available at: https://storage.googleapis.com/cgiarorg/2019/11/SC9-02_SRG-Recommendations-OneCGIAR.pdf

CGIAR-IEA (2017). Evaluation of gender in CGIAR. Independent evaluation arrangement of the CGIAR. Available at: http://iea.cgiar.org/

Cole, S. M., Kaminski, A. M., McDougall, C., Kefi, A. S., Marinda, P. A., Maliko, M., et al. (2020). Gender accommodative versus transformative approaches: a comparative assessment within a post-harvest fish loss reduction intervention. Gend. Technol. Dev. 24, 48–65. doi: 10.1080/09718524.2020.1729480

Colfer, C. J. P., Sijapati Basnett, B., and Ihalainen, M. (2018). “Making sense of “intersectionality”: A manual for lovers of people and forests” in Occasional chapter 184 (Bogor: CIFOR)

Drucza, K. L., and Wondimu, A. (2017). Gender transformative methodologies in Ethiopia's agricultural sector: A review. Addis Ababa: CIMMYT.

Elias, M., Badstue, L., Farnworth, C. R., Prain, G., van der Burg, M., Petesch, P., et al. (2018). “Fostering collaboration in cross-CGIAR research projects and platforms: lessons from the GENNOVATE initiative” in GENNOVATE resources for scientists and research teams (CDMX, Mexico: CIMMYT)

Elmhirst, R., Siscawati, M., Basnett, B. S., and Ekowati, D. (2017). Gender and generation in engagements with oil palm in East Kalimantan, Indonesia: insights from feminist political ecology. J. Peasant Stud. 44, 1135–1157. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2017.1337002

Farhall, K., and Rickards, L. (2021). The “gender agenda” in agriculture for development and its (lack of) alignment with feminist scholarship. Front Sustain Food Syst 5:20. doi: 10.3389/FSUFS.2021.573424/BIBTEX

Farnworth, C. R., Fischer, G., Chinyophiro, A., Swai, E., Said, Z., Rugalabam, J., et al. (2022). Gender-transformative decision-making on agricultural technologies: Participatory tools. Ibadan, Nigeria: IITA. Available at: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/127692

Farnworth, C. R., Gurung, B., and Jiggins, J. (2007). My practice is my strategy: values in organisations. Organ People 14:31.

Galiè, A., Teufel, N., Korir, L., Baltenweck, I., Webb Girard, A., Dominguez-Salas, P., et al. (2019). The women’s empowerment in livestock index. Soc. Indicators Res. 142, 799–825.

Hankivsky, O. (2014). Intersectionality 101. The Institute for Intersectionality Research and Policy, Simon Fraser University.

Hawthorne, S. (2004). The political uses of obscurantism: gender mainstreaming and intersectionality. Dev Bull 64, 87–91.

Hur, M. H. (2006). Empowerment in terms of theoretical perspectives: exploring a typology of the process and components across disciplines. J. Community Psychol. 34, 523–540. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20113

Iaquinto, B., Ison, R., and Faggian, R. (2011). Creating communities of practice: scoping purposeful design. J. Knowl. Manag. 15, 4–21. doi: 10.1108/13673271111108666

Istratii, R. (2020). Adapting gender and development to local religious contexts: A decolonial approach to domestic violence in Ethiopia. London: Routledge.

Kauck, D., Paruzzolo, S., and Schulte, J. (2010). CGIAR gender scoping study. Washington D.C.: ICRW.

Longino, H. E. (1993). Feminist standpoint theory and the problems of knowledge. Signs 19, 201–212. doi: 10.1086/494867

Longino, H. E. (2017). “Feminist epistemology” in The Blackwell guide to epistemology. Eds. J. Greco and E. Sosa. (Wiley), 325–353.

Lopez, D. E. (2022). Tensions and transformations: Gender research and practice in agricultural research for development. Wageningen: Wageningen University & Research.

Lopez, D. E., and Ludwig, D. (2021). “A transdisciplinary perspective on gender mainstreaming in international development: the case of the CGIAR” in The Politics of Knowledge in Inclusive Development and Innovation. Eds. D. Ludwig, B. Boogaard, P. Macnaghten and C. Leeuwis (New York), 48.

Malapit, H., Quisumbing, A., Meinzen-Dick, R., Seymour, G., Martinez, E. M., Heckert, J., et al. (2019). Development of the project-level Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (pro-WEAI). World Develop. 122, 675–692.

Mangheni, M. N., Tufan, H. A., Boonabana, B., Musiimenta, P., Miiro, R., and Njuki, J. (2019). Building gender research capacity for non-specialists: lessons and best practices from gender short courses for agricultural researchers in sub-saharan africa. Adv Gender Res 28, 99–118. doi: 10.1108/S1529-212620190000028006/FULL/EPUB

McAlvay, A. C., Armstrong, C. G., Baker, J., Black Elk, L., Bosco, S., Hanazaki, N., et al. (2021). Ethnobiology phase VI: decolonizing institutions, projects, and scholarship. J. Ethnobiol. 41, 170–191. doi: 10.2993/0278-0771-41.2.170

McDougall, C., Badstue, L. B., Mulema, A. A., Fischer, G., Najjar, D., Pyburn, R., et al. (2021). “Towards structural change: gender transformative approaches.” In R. Pyburn and A. Eerdewijk van (Eds.), Advancing gender equality through agricultural and environmental research: Past, present and future. (Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI)), 365–402.

McDougall, C., Cole, S. M., Rajaratnam, S., and Teioli, H. (2015). “Implementing a gender-transformative research approach: early lessons” in Research in development: Learning from the CGIAR research program on aquatic agricultural systems. eds. B. Douthwaite, J. M. Apgar, A. Schwarz, C. McDougall, S. Attwood, and S. Senaratna Sellamuttu, et al. (Penang: CGIAR Research Program on Aquatic Agricultural Systems), 48–52.

McGuire, E., Rietveld, A. M., Crump, A., and Leeuwis, C. (2022). Anticipating gender impacts in scaling innovations for agriculture: Insights from the literature. World Develop. Perspect. 25:100386.

Mertens, D. M. (2021). Transformative research methods to increase social impact for vulnerable groups and cultural minorities. Int. J. Qual. Methods 20:160940692110515. doi: 10.1177/16094069211051563

Morgan, M. (2014). Measuring gender transformative change. Penang, Malaysia: CGIAR Research Program on Aquatic Agricultural Systems. Program Brief: AAS2014-41.

Njuki, J., Eissler, S., Malapit, H., Meinzen-Dick, R., Bryan, E., and Quisumbing, A. (2022). A review of evidence on gender equality, Women’s empowerment, and food systems. Glob. Food Sec. 33:100622. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2022.100622

Özgediz, S. (2012). The CGIAR at 40: Institutional evolution of the World’s premier agricultural research network. Available at: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10947/2761

Palmary, I., and Nunez, L. (2009). The orthodoxy of gender mainstreaming: reflecting on gender mainstreaming as a strategy for accomplishing the millennium development goals. J. Healthc. Manag. 11, 65–78. doi: 10.1177/097206340901100105

Peake, L. (2017). “Feminist methodologies” in The AAG international encyclopaedia of geography. eds. D. Richardson, N. Castree, M. F. Goodchild, A. Kobayashi, W. Liu, and R. A. Marston (John Wiley and Sons, Ltd), 2331–2340.

Poats, S. (1990). Gender issues in the CGIAR system. Lessons and strategies from within. Chapter presented at the Consultative Group Meeting, The Hague.

Polin, L. G. (2010). “Graduate professional education from a community of practice perspective: The role of social and technical networking,” in TSocial learning systems and communities of practice. (London: Springer), 163–178.