- 1International Center for Tropical Agriculture, Nairobi, Kenya

- 2Consultant, Nairobi, Kenya

Five to seven in every 10 people in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) are youths. They have significantly low employment rates but are unattracted to agriculture. Recently, the sector has witnessed considerable efforts by African governments to promote youth participation. While these efforts have started to bear fruits, salient gender issues remain hard to address and solve promptly. For example, youth empowerment issues—whether mutual or emancipative, asset ownership, taboos and cultural expectations, perceptions against climate change, and use of technology and ICT significantly influence livestock production among pastoralists and agro-pastoralists. While these problems are partly known and being solved, it is to be understood the extent and the salient gender issues that drive youth participation in livestock production. To understand this, we conducted a systematic review using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to thematically synthesize and evidence the youth-empowering interventions in livestock production systems in Sub-Sahara Africa. Peer-reviewed studies were retrieved from online databases (Scopus, Google ScholarTM, and gray literature). The findings show that youth face significant barriers to participating in livestock systems ranging from limited empowerment, limited access to productive assets and land, social-cultural limitations and inadequate youth-focused policy implementation. Despite the hurdles, youths, and other actors are employing various mechanisms to overcome them and enhance their participation in livestock systems. They utilize self-driven approaches such as gifting animals amongst themselves, forming saving groups commonly referred to as merry-go-rounds and belonging to community group formations as a form of social capital to empower themselves mutually. Education is also an empowerment tool for youths in the livestock sector. Emancipative empowerment through participation in political and community-level leadership is taking shape, though still in its infancy. There are opportunities presented by small ruminants and poultry where women and youths are getting a voice in the community by becoming relatively income independent and desisting from waiting for the inheritance of large livestock and assets from men. Opportunities presented by ICT in the field of livestock have been taken advantage of through the use of various apps and internet tools to enhance youth participation in livestock systems.

1. Introduction

Youths, defined by United Nations and African Union Youth Charter as persons within 15–24 years, 15–35 years, respectively and whose definitions differ by country, such as those between 18–34 years in Kenya, form the largest part of the population in Sub-Sahara Africa (African Union, 2006; Senga and Kiilu, 2022). It is believed that 5 to 7 in 10 persons are under 30 years in Sub-Sahara Africa, thus the “youth bulge” phenomenon NEPAD (NEPAD, 2022; United Nations, 2022). This demographic advantage can be leveraged for the economies of Sub-Sahara African (SSA) countries, as seen in the “East Asian miracle” that has resulted in more than half of the total economic growth in Asia (Bloom et al., 2000). On the other hand, there is also a prevalent narrative of the “ticking time bomb” phenomenon, where an additional billion youths are expected to enter the global job market creating the “angry young men” crisis (Kalliney, 2001; ILRI, 2019). Therefore, there is a pressing requirement for boosting agricultural production to generate a surplus of employment opportunities and lead to over a two-fold rise in the output of industrial and service sectors, facilitated by a shift of labor from off-farm to on-farm sectors (Lipton, 2005).

Interestingly, studies are also finding that since 2000, crop and livestock production has appealed less and less to the youths (Rhiannon et al., 2014; Diogo et al., 2022). On the other hand, there are counterarguments about youth engagement in agriculture as demonstrated in the case of rural Ethiopia and Zambia where introduction of modern farming practices, low-tech solutions like diversification, use of ICTs, draft animals, use of electricity was reported to induce uptake of farming by the youths (Leavy and Hossain, 2014). Reconciling these two juxtapositions require a revisit to well-evidenced youth engagement in agriculture to the extent of challenging the prevailing orthodoxies and assumed policy proposals about youth participation in agriculture in general and livestock sector in particular. Thus, the livestock sector which is dogmatized with gender and youth issues and that reportedly has potential for creating employment through dairy farming, zero grazing, meat provision is pursued in this study. The sector significantly contributes to countries' Gross Domestic Products (GDP) e.g., 10–13% to Kenyan agricultural GDP and 33% to Ethiopian GDP (FAO, 2019). In Uganda, livestock production is valued at around USD 8.7 million per year (Solomon and Assegid, 2003).

To enhance youth participation in the livestock sector, African governments have responded by enacting various policies and developmental programs that would increase production and create employment opportunities for the youths. These efforts are believed to enhance youth empowerment. Youth empowerment can loosely be defined as the process of equipping young people with the right skills, knowledge, and resources with an aim of overcoming developmental barriers (Holden et al., 2004). Some youth empowerment interventions by African governments include: the “Youth in Agribusiness” program in Nigeria which is implemented by the Central Bank of Nigeria and the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development and that aims to empower young people to participate in the livestock sector by providing them with training, mentoring and access to finance (Bello et al., 2021). The “African Youth Agripreneurs” program in Ghana implemented by the African Development Bank, is aimed at empowering young people to become agripreneurs in the livestock sector by providing them with training, mentorship, and access to financial services (ADB.AYAF, 2020). The “Youth in Agribusiness” program in Kenya, implemented by the government of Kenya and the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), aims to support young people to enter the livestock sector by providing them with training, mentorship, and access to financial services (MOALF, 2018). The “Youth in Livestock Development” program in Ethiopia, implemented by the Ethiopian government and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), aims to support young people to enter the livestock sector by providing them with training, mentorship, and access to resources such as land, feed, and veterinary services (FAO, 2018). While these programs and policies have achieved tremendous success in the recent past, numerous shortcomings have been observed, including lack of government's commitment, lack of proper project management, lack of funding among others (Ika and Saint-Macary, 2014). One factor that is often neglected is the role of gender and youth issues in livestock production as discussed in Kinati and Mulema (2018).

1.1. The gender-youth nexus in livestock production in Sub-Sahara Africa

While revitalization of agriculture in rural areas presents tremendous opportunities for youth employment, gender issues are emerging to be a pain-point to fully maximize these realizations. Indeed, a critical debate is emerging on whether rapid rural transformation efforts through digitalization and “feminization” of agriculture and capacity-building efforts will attract youths to boost livestock production especially the adoption of technology-intensive zero-grazing methods (OECD, 2018). Gender pertains to the expectations and social norms that define the roles and identities attributed to individuals as either male or female within a given society or context. Gender roles can be influenced by a variety of factors such as ideology, religion, ethnicity, economics, and culture, and they have a significant impact on the allocation of responsibilities and resources between men and women either young or old. Gender roles are shaped by social constructs and are therefore fluid and prone to change depending on evolving social norms, circumstances among other factors (Quisumbing et al., 2014). Although gender disparities are inherent in every society, these differences can vary greatly across cultures and can shift drastically over time, either within a single culture or across different ones. A particular case of gender disparities exists within the livestock system.

Specifically, youths in livestock farming in Africa can face a variety of gender-related issues, including: (a) limited access to land, particularly for young women, making it hard for them to establish and operate their own livestock farms (Rabinovich et al., 2020), (b) inadequate education and training opportunities, hindering their ability to acquire the knowledge and skills needed to effectively raise and manage livestock (Scott-Villers et al., 2016), (c) societal norms and expectations, particularly traditional gender roles, that often restrict young women's opportunities in the livestock sector (Kaba et al., 2013; Moyo, 2014), (d) discrimination and mistreatment due to the perception of being uneducated or “backwards”, (e) inadequate access to credit and financial services, making it difficult for them to secure the funding necessary to start and expand their livestock businesses (Opiyo et al., 2016), and (f) limited representation in leadership roles, particularly the underrepresentation in leadership positions in the livestock industry, which can hinder their influence on policies and decisions that impact the sector (Afande et al., 2015). Gender and socially imposed roles, along with traditional customs like female genital mutilation and the unequal distribution of assets and leadership positions among youth, have a disempowering impact, particularly on young women (Vincent, 2022). For example, as seen in many communities that keep livestock, it is common for men and boys to be the sole owners of the herds while women are assigned household tasks, constructing temporary dwellings, and caring for the children (Maru, 2017). Another example could be the issues of patriarchy established in culturally contingent systems that limit realization of rights and justice for young girls (Tavenner and Crane, 2019).

Currently, youth participation in livestock production, is hard to estimate due to minimal age-disaggregated data—and approximated at only 15% (ILRI, 2019). Besides, most livestock keepers are nomadic pastoralists, a few are agro-pastoralists and only a handful practicing zero grazing. In fact, about 50–270 million pastoralists occupy about 40 percent of the entire Africa's land mass; with a poverty rate of between 70–85% (Gueye, 2017). It has been observed that pastoralists, particularly young pastoralists who have a strong feeling of identity with their livelihood and who are frequently referred to as the “heirs of the heritage,” are increasingly shunning the tradition and looking for work in towns (Maru, 2017). Due to their lack of education, youth in pastoral villages are also at a disadvantage in the job market and end up working menial occupations in urban areas, as was the situation with Maasai youth in Tanzania (Munishi, 2013). Besides, traditional livestock keeping is threatened by climate change that has exacerbated drought and livestock keepers and mostly pastoralists are now termed as the highly-at-risk group with disrupted livelihoods and shrinking pasturelands that often cause conflicts and deaths to both humans and animals (Akall, 2021). Therefore, modernizing livestock practices and capacity-building the youths who are the heirs-of-the-tradition with ICT knowledge and modern technology-intensive practices would most likely induce their interest in commercial livestock farming and improve commercialization of livestock and livestock products (Leavy and Hossain, 2014).

Together with various issues in livestock systems, this study presents a systematic literature review that is arranged thematically, to highlight the gender-youth nexus in livestock systems with a particular focus on evidence of interventions that are facilitating youth participation in livestock systems. This systematic review delivers a meticulous summary of the available research, making available evidence more accessible in a concise manner, to decision-makers and other researchers working on the same or similar issues. It also highlights constraints and opportunities for particular research questions or research areas. In our case, we are interested in understanding youth participation and engagement beyond livestock production to understand gaps and guide interventions that can intentionally target youths in the livestock value chain within and external to the CGIAR. It delineates from general discussions on the types of livestock kept. It fills the following gaps in literature: Gender equality, youth & social inclusion is one of the impact areas of the CGIAR and the gender impact platform. This is in line with the call for youth inclusion in agriculture and this study contributes to the understanding of the challenges and opportunities in this phenomenon. The interest is to “synthesize and amplify research, fill gaps, build capacity and set directions to enable CGIAR to have maximum impact on gender equality, opportunities for youth and social inclusion in agriculture and food systems. This systematic review responds to this need to gather evidence and understand the opportunities or entry points for youths in the livestock system, a sub-section of the agri-food system. Secondly, youth inclusion and gender issues in livestock farming practices are critical areas that warrant attention, especially in the context of the “youth bulge” and the need to create employment opportunities in the agricultural sector. Therefore, there is a pressing need for an in-depth exploration of the gender-youth nexus in livestock farming, examining themes such as empowerment, education, ownership of assets, societal norms, and adaptation strategies, to address the complexities and opportunities in this area. Evidence gathered and summarized in this review could inform the discourse on the development of policies that target and promote youth participation in livestock production systems in Sub-Sahara Africa. Policy makers can use the evidence to identify salient issues in making agriculture, especially livestock keeping an attractive agribusiness venture that employs the youths.

1.2. Research questions

The main aim of this study is to provide thematically synthesized evidence on gender-empowering and youth-targeted interventions/strategies in livestock production among the youths in Sub-Sahara Africa. It presents the variation across studies in the outcomes that concern broad themes and sub-sets through the following research questions:

a. What are the gender empowerment outcomes for the youth with regards to education achievement, household headship, household decision making, asset ownership e.g., communal land among youth livestock farmers?

b. Do reported differentials in cultural taboos and tradition affect participation in livestock farming for the youth?

c. Do climate change perceptions differ among youth livestock farmers and what adaptation, mitigation and coping strategies youth use?

2. Methods

2.1. Literature search criteria

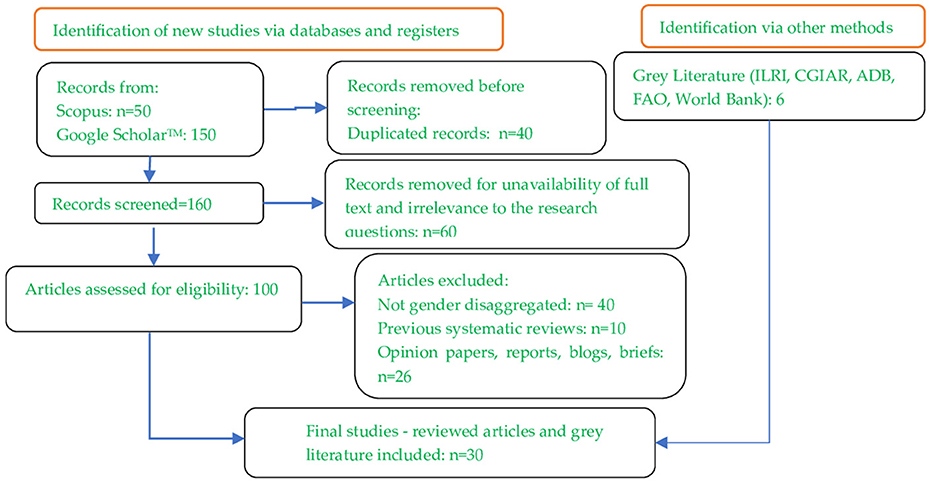

We carried out literature search in electronic repositories with peer-reviewed articles published in the English language only. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria was used to assess the relevance of literature to be included (Maru, 2017). The study specifically employed a systematic review rather than meta-analysis due to its qualitative nature and because of the heterogeneity in the aspects reported by each author, due to different settings and study designs. This, therefore, meant that rigorous risk-biases associated with meta-analysis while comparing similar outcomes from different authors was not a problem. Nonetheless, the review authors independently evaluated all the studies to judge if there were certain elements that would warrant assessment of risk of bias for each domain and agreed that non would be of concern to the current paper as discussed in Page et al. (2021). The recommendations of Page et al. (2021), therefore, were followed to the latter (36) as shown in Figure 1. The search was carried out between 15th-16th November, 2022 in the Scopus repository, Google Scholar and additional gray literature (documents produced by organizations with non-commercial publishing) from International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and subsidiary CGIAR centers. These institutions carry out large research on livestock across African countries. Limits on the year of publication and the study design were not imposed because of the limited articles that cover the subject on youths with respect to gender issues. Geographical coverage was limited to Sub-Sahara African countries and based on the 2020 survey carried out by Statista (2022).

Figure 1. Systematic literature review inclusion and exclusion criteria. Source: Author's based on Page et al. (2021) PRISMA guideline.

The search phrases used in the Scopus included “livestock” AND “gender” AND “youth” AND Limit-To (Doctype, “article” Srctype, “j” and interchangeably with OR to join the search string). In Google ScholarTM, the search phrases included allintitle: “livestock” OR “pastoralist” AND “gender” OR “youth” and “[country].” The search was also augmented with the allintext search criteria for in-text keywords to ensure all texts with relevant search phrases weren't excluded. The intext text search was modified to avoid returning only general “livestock” string and synonymous words such as dairy, ruminants, sheep, goats, cows, poultry, chicken, pigs etc. would be used. It was not surprising that this search string always returned the same papers because most authors often start with keyword livestock in their writings. In each successive search, the specific country was iteratively replaced, and the search phrase modified with respect to the theme, e.g., “youth empowerment” OR “education” OR “land ownership” OR “assets” etc. in accordance with the pre-defined thematic areas of interest. The searches in both databases yielded 206 articles. We purposively included a few gray literatures from ILRI and other CGIAR centers to maximize the discussions regarding youth and livestock and to mitigate publication bias in articles as discussed in Gusenbauer and Haddaway (2020).

2.2. Study selection, inclusion, and exclusion criteria

Peer-reviewed journal articles from reputable journals and peer-reviewed reports from NGOs promoting livestock systems in Sub-Sahara Africa were included based on the following criteria: (i) the study reported on youth participation in agriculture with a particular focus on livestock; (ii) the study attempted a disaggregated analysis, preferably by gender; (iii) it was written in English; (iv) not an editorial, expert opinion, review or instructive article, blogs (except gray literature), web pages, opinion pieces, and magazine articles. They were excluded because they lacked scientific rigor. Articles included in our final analysis were 30 i.e., 24 peer reviewed articles and 6 gray literature. Data extracted from each article included author's name, year of publication, study interventions, gender issues addressed, outcomes realized among others. The summarized documents are shown in the section for summary of findings (Tables 1, 2).

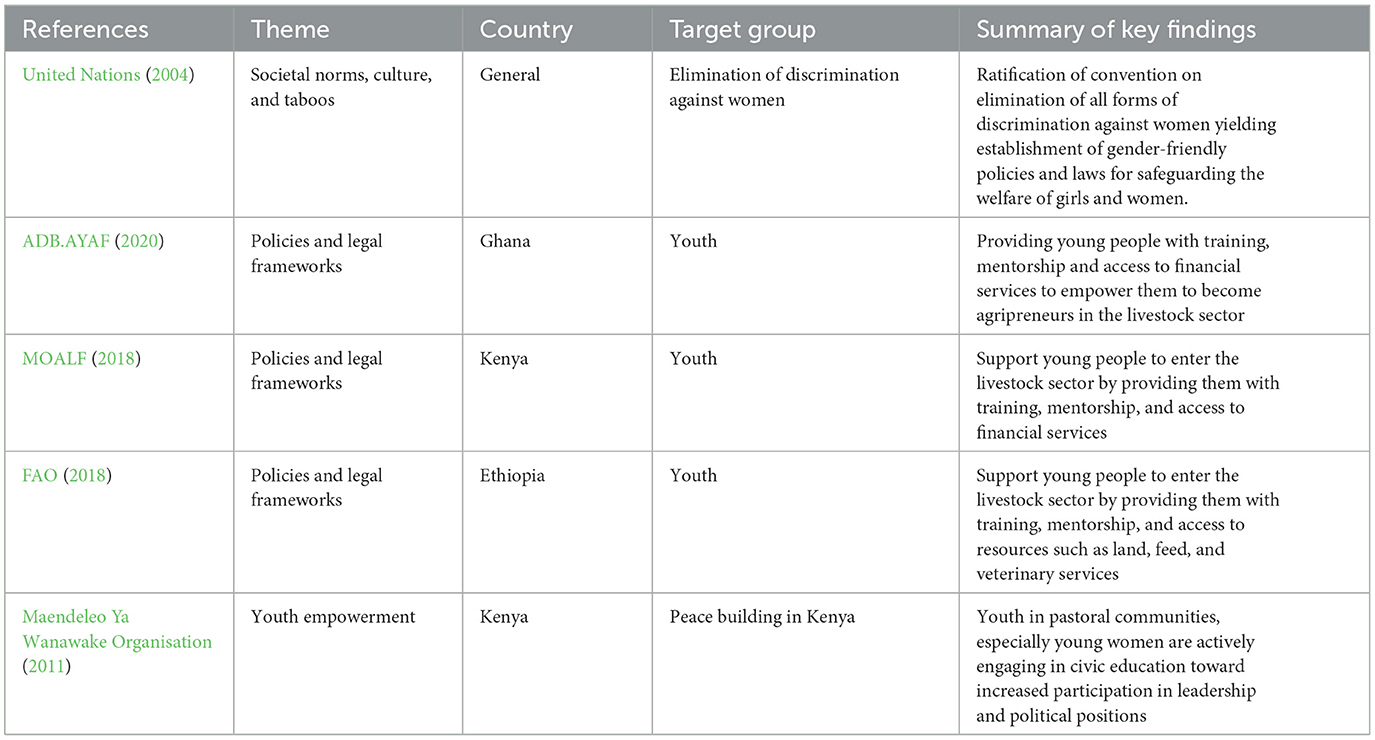

Table 1. Summary of peer-reviewed articles on youth and livestock disaggregated by thematic area, authorship, target country and target group.

Table 2. Summary of gray literature on youth and livestock disaggregated by thematic area, authorship, target country and target group.

3. Results

In this section, the study presents various outputs from each selected paper and the specific gender and youth inclusion approaches and policy issues in livestock farming practices it explores. Results are clustered around general thematic areas in the gender-youth nexus. These themes are supported by evidence regarding youth engagement in livestock farming are used to back up the claims. Tables 1, 2 summarizes the literature that was reviewed in terms of the authors, theme covered by the study, the country of the origin of the paper, the population of youth being targeted and the main findings of the paper.

3.1. Youth empowerment

Although the notion of youth empowerment is intricate, vague, and lacks well-defined limits, we adopt the definitions put forward by Úcar et al. (2017) that empowerment is essentially about enabling young people to attain optimal growth by acquiring competencies as they overcome specific challenges. Thus, on the theme of youth empowerment in livestock production, discussions are based on general dimensions that include: (a) relational empowerment—in which youth engagements in livestock production to a greater degree depend on mutual empowerment among young people themselves, (b) empowerment through educational achievements—in which acquisition of competences with notable indicators of self-efficacity, critical thinking, and participation (Africa Educational Trust, 2011; Maendeleo Ya Wanawake Organisation, 2011; Enns and Bersaglio, 2016; Scott-Villers et al., 2016; African Development Solutions, 2017; Ancey et al., 2020; Yitbarek et al., 2022) and (c) transformative/emancipative empowerment—in which empowerment is integrated within the development of abilities for social change awareness of socio-political hierarchies of power and availability of support structures and those conditions that lead to young people being able to act in their own name and on their own terms instead of being controlled by others (Wagaman, 2011).

We found very few peer-reviewed articles evidencing mutual empowerment in youth-led livestock farming. One study in Kenya by Mutua et al. (2017), explored group membership and “merry-go-round” as strategies for acquisition of livestock by youths and also “gifting” of livestock to each other as a mutual empowerment strategy. While such approaches helped male youths in these communities, gender issues surrounding inheritance were still bold as girls could not inherit livestock or any kind of property—because it encouraged insubordination and reduced chances of getting married among pastoral communities such as the Tugen. Even group membership that would encourage mutual empowerment had limitation as it depended on someone's perceived wealth status in the community (Mutua et al., 2017). On the other hand, while a system of indigenous mutual support practices (IMSPs) exists in Ethiopia among pastoralists, youth-led initiatives that encourage belonging to Savings Internal Lending Communities (SILC) would be a great way for overcoming limited access to income and developing mutually-beneficial social capital to help other youths in the livestock sector (Endris et al., 2022). Most discussions on the mutual empowerment from the gray literature discussed potential but not the actual empowerment in farming among the youths (Maendeleo Ya Wanawake Organisation, 2011; Rhiannon et al., 2014; Scott-Villers et al., 2016; ILRI, 2019).

Educational empowerment with regards to young girls' in nomadic pastoral and agropastoral communities has taken a center stage in most literature and government policies (United Nations, 2004; Maendeleo Ya Wanawake Organisation, 2011; Scott-Villers et al., 2016). It is viewed through the angle of educational attainment among youths in livestock keeping communities. For example, while an enabling policy environment has been created in Ethiopia since 1994, enrollment, retention, and learning attainment remain low in the pastoralist areas for girls (Yitbarek et al., 2022). In Kenya, girls who are educated are prone to losing their “marriageability” (Scott-Villers et al., 2016). Among the Fulani of Nigeria, educating a girl-child should be limited to “preparing her for the roles of mother and wife” (Fareo and Ateequ, 2020). Despite these educational challenges, evidence shows that gender norms and practices contributed to the passing of traditional ecological knowledge from adult to child. This is the case of young girls in Maasai areas in Southern Kenya who had better knowledge of wood species better than boys on their firewood collection duties (Tian, 2017). Evidently, educational empowerment through the governments' affirmative action has also seen rise in youths (both girls and boys) enroll in primary and secondary education among livestock keepers in Kenya (Odhiambo, 2013). In Burkina Faso, schooling has seen reduced child marriages as education offers an alternative pathway for girls beyond marriage (Misunas et al., 2021). In fact, education is viewed as part of the family's strategy to diversify the household income in Burkina Faso and targeted to youths who can no longer be integrated within the livestock systems (Ancey et al., 2020). In Chad, young migrants from pastoralist are often interested in “evening classes” in French, as this helps them overcome cultural shocks associated with traditional livestock keeping and adapting to town life (Ancey et al., 2020).

Within the domain of transformative/emancipative empowerment, this study provided evidence of youth in livestock production and their engagement in socio-political aspects such as leadership to overcome some gender issues in livestock farming. Breaking free from gender norms requires young people to use empowerment strategies that are not dependent on receiving assets from older generations. For instance, instead of waiting to inherit livestock from their fathers, young girls and women in Kenya have opted for less capital-intensive and more accessible options, such as poultry, as a means of generating income (Sulo et al., 2012; Mutua et al., 2017). Similarly, young people in Ethiopia are taking a similar approach by working in wage positions in small-ruminant food chains, bypassing the traditional practice of older generations owning larger animals and as a means of employment (Mueller et al., 2017). Additionally, young women in Ethiopia can now control income from sale of milk cheese and butter from small ruminants such as sheep and goats (Kinati and Mulema, 2018). Access to livestock can also be strongly gendered. For example, in Kenya, only men can inherit livestock such as cattle, sheep and goats as a customary right, although they can be gifted to both genders. Instead of engaging in traditional milk production methods, evidence from Ethiopia show that a segment of young, educated, and affluent farmers have embraced an upgrade to production of high quality milk production (Ruben et al., 2017).

On the other hand, evidence from gray literature shows that youths in pastoral communities are actively engaging in civic education toward increased participation in leadership and political positions—especially the young women in Kenya (Maendeleo Ya Wanawake Organisation, 2011). In Ethiopia, the increased political interventions and rights awareness among young men and women in livestock keeping areas has been witnessed among youths participating in registered cooperatives (Hebo, 2014). This evidence is also demostrated by Endris et al. (2022) who argue that youth membership in Savings Internal Lending Communities (SILC) has achieved tremendous youth participation in community-based civic education but would even work better if education among the participants was improved.

3.2. Overcoming challenges of ownership of land and assets

Whereas entrepreneurial opportunities exist for youth in livestock systems, barriers including the inadequate access to land hinders success among youths agripreneurs in Kenya (Ouko et al., 2022). Notably, research has found a correlation between low youth participation in agribusiness and inadequate access to land (Njeru and Gichimu, 2014; Afande et al., 2015; Lwanga-Ntale and Owino, 2020). Innovative strategies aimed at improving young people's access to resources have been witnessed to yield positive results. Notably, in Malawi and South Africa, land reform initiatives have enabled youth to gain access to land. In Ethiopia, rehabilitated communal land was allocated to youth groups, opening up opportunities for them to participate in agricultural value chains. Additionally, land rentals and leasing programs have also been effective in expanding access to land. These interventions have shown promising potential to empower youth and promote economic growth in their communities (Yami et al., 2019). In Africa, patrilineal inheritance systems are prevalent, where the male line determines succession and property inheritance, with only sons or other males inheriting land from the family estate. This practice excludes daughters from inheriting family land due to the belief that they become part of another family upon marriage. Despite this, Islamic law recognizes a woman's right to inheritance, but her share is often smaller than a male relative's. To combat this discrimination, several countries have enacted family and succession laws that override customary norms, establish community property rights over family land, and grant spouses' equal rights in managing family land. Examples include Ghana's Intestate Succession Law 1985 and Ethiopia's Revised Family Code 2000, though the implementation of these laws remains low (Cotula et al., 2004).

3.3. Toward overcoming societal norms, expectations, cultural taboos, and traditions

Livestock keeping is dogged with numerous culturally underpinned taboos and traditions among which female genital mutilation, early child marriages, labor division (drudgery) and patriarchy are prominent (Mutua et al., 2017; Daum, 2019). Overcoming these have attracted myriad strategies among which ratification of Convention on Elimination of All forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) has resulted in established gender-friendly policies and laws aimed at safeguarding the welfare of girls and women, including affirmative action for higher education (United Nations, 2004). Deeply ingrained social and cultural practices continue to pose a significant challenge and this is particularly true for pastoralist girls and women (Korir, 2018). However, these practices are changing with affirmative action put in place by governments for the livestock-keeping communities as witnessed in the case of Kenya. Evidently, the mandatory admission, attendance, completion of basic education and 100% transition to secondary schools by all youths in Kenya has resulted in reduced rates of FGM among youths in pastoral/livestock-keeping communities (Korir, 2018). In Ethiopia, overcoming traditional practices such as FGM has witnessed increased use of experience-sharing events among livestock-keeping households to curb the tradition (Wondim and Kefale, 2018). These experience-sharing events can be extended to cases of gender-based and child-based violences in which children or adults experiencing these are often witnessed to seek support from a range of people mostly kin and friends in Ethiopia (Chuta et al., 2019). In Chad and Burundi, early child marriages and FGM have been reported in various literature, but evidence shows that well-targeted interventions for the youths put in place and based on Social Cohesion and Community Based Protection Mechanisms; are already reducing child marriages through what is called “WellBeing of Community Groups” that protect vulnerable groups (Besada et al., 2014).

While patriarchy and clannism also contribute to youth discrimination in livestock keeping communities, in Somalia, for example, youths overcome such by using alternative sources of income such as remittances from the diaspora and forming youth groups to diversify their income and overcome patriarchy-based wealth generation system (Lwanga-Ntale and Owino, 2020). Evidence shows that this leads to independence in decision and use of own income to purchase herds of camels and small ruminants. In Kenya, the use of “sensitizing men” training modules among livestock keepers and that is targeted to young men has resulted in increased recognition of the negative effects of patriarchy among young men (Tavenner and Crane, 2019). This has resulted into more allocation of resources toward purchasing women produce from small ruminants and poultry in the area, a case of “leading-by-example” to overcoming patriarchy among the youths.

3.4. Use of ICT among the youths in livestock systems

In some cases, youth participation in livestock production has been enhanced through use of modern technologies. For example, overcoming drudgery associated with intensive livestock keeping has witnessed transition to mechanized zero gazing from nomadic pastoralism. In Nigeria, a proposal for use of Information, Communication Technology (ICT) in livestock keeping areas, especially use of real time and customized information to overcome system inefficiencies and optimize production has witnessed youths using apps to access inputs, finance, training and market their produce such as milk conveniently (Akilapa et al., 2020). In Kenya, the use of ICT services especially DigiCow Dairy App from Farmingtech Solutions and SmartCow have been used to enable youth livestock keepers use ICT services to relay herd data to experts thus improving their management practices (Daum et al., 2022). In Tanzanian youth dairy farmers access the Shamba-shape up episodes through the website, radio and TV (Okello et al., 2020). This platform gives youths independence in terms of access to livestock production information. The changing access to information also helps the youth overcome barriers to markets and even pricing of livestock. On the other hand, there are evidence of behavioral change on engagement in agriculture due to use of ICT-enabled platforms as has been witnessed in the Songhai model in Benin, and the AFOP program in Cameroon in which youths engaged in transformational agricultural practices have indicated attitudinal change in livestock keeping especially the startups (Eley et al., 2014). Efforts to increase the use of ICT in agriculture that would, in turn, increase youth participation in the sector are being promoted through the National Agriculture Policy of 2013, which was implemented by the then Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperative in Tanzania, gives credence to integration of ICT in agriculture (Bernard et al., 2019).

3.5. Differentials in climate change perceptions, climate activism, and adaptation strategies

Many references in the literature including IPPC 2018 report highlight that women and youth are more vulnerable to climate change in agriculture and livestock keeping, as they often have less access to information, markets, credit, or insurance in addition to already having heavy workloads in the home. However, many governments and organizations recognize that investing in women is often a better return than in investing in men, possibly because women have stronger family ties and stay at home and depend on livestock more.

Climate change and the resultant environmental stressors as well as environmental degradation often undermine the resilience of livestock production systems. Youth perceptions, responses and mitigation strategies including climate activism with respect to livestock has received little attention in literature (Mugeere et al., 2021). Climate change and the resultant environmental stressors as well as environmental degradation often undermine the resilience of the lives of pastoralists to climate change is necessary for sustainable mitigation and coping strategies (African Union, 2006; Senga and Kiilu, 2022). Perception is very much likely to influence how agripreneurs respond to risks as well as opportunities that come with climate change. Perception will determine the nature, the course of action and the outcomes of the adaptation strategies chosen. In Kenya, there was reported a positive correlation between the age of the household head and the practice of climate change adaptation activities. In other words, older household heads were more likely to engage in activities to cope with the effects of climate change than younger household heads. This suggests that experience and knowledge may play a role in shaping attitudes and behaviors toward climate change adaptation in this particular context (Opiyo et al., 2016). On the contrary, results from studies on the determinants of adaptation to climate change among agro-pastoralists in Botswana and Ethiopia show that in terms of the age of the household head, younger pastoralists are more likely to employ climate change adaptation strategies than their older counterparts. This is explained by the view that older pastoralists are likely to be inclined toward preferring conservative methods of adaptation to climate change as opposed to modern and more relevant strategies. In this study, the perception on climate change was based on an increase in annual temperature and a general decline in the annual rainfall received (Kgosikoma et al., 2018; Gebeyehu et al., 2021).

4. Discussion and conclusion

This study sought to establish thematically synthesized changes on youth participation in livestock production against the backdrop of “youth bulge” and the need to create employment in the agricultural sector to absorb the youths. To assess this, various databases were queried with a realization that limited peer-reviewed articles exist on youth and livestock with respect to Sub-Sahara Africa, a matter that was also raised by Vincent (2022). Even this thin literature seems to concentrate heavily on some countries especially Kenya, Uganda, Nigeria, Chad, and Ethiopia. This has mostly been attributed to the fact that the search databases are often based on English language (excluding Arabic and Francophone countries) and also on the fact that research is difficult in most areas where livestock keeping is practiced due to conflicts (Mkutu, 2008; Holechek et al., 2017; Gammino et al., 2020). In addition, the literature evidencing youth participation in livestock production is more concentrated among the pastoral communities and only a few concentrates on youth with respect to agropastoral communities and zero grazing. It is our assumption, that perhaps authors prefer to research on the pastoral communities because they are observed to have some of the highest concentrations of gender problems such as early childhood marriages, FGM, inequalities in asset ownership and subjection of women to traditions and taboos that are difficult to change (Maendeleo Ya Wanawake Organisation, 2011). Nonetheless, various gender-youth nexus issues have been observed and evidence of how youths in livestock overcome or cope with them have been reported.

In the case of youth empowerment, it is observed that they utilize self-driven approaches such as gifting of animals amongst themselves, forming saving groups commonly referred to as merry-go-rounds and belonging to community groups formation as a form of social capital to mutually empower themselves (Mutua et al., 2017; Endris et al., 2022). Education is also an empowerment tool for youths in the livestock sector. For example, even under gender-defined roles, young women in livestock-keeping areas seem to be more knowledgeable on some aspects compared to males; and youths in countries such as Chad and Burkina Faso are taking education as a factor for changing their livelihoods and moving from traditionally “acceptable” livelihoods (Odhiambo, 2013; Ancey et al., 2020; Misunas et al., 2021). Evidence shows that emancipative empowerment through participation in political and community-level leadership is taking shape, even though it is still at the infancy. The opportunities presented by small ruminants and poultry is giving women and youths and opportunity to have a voice in the community by encouraging income-based independence and desisting from waiting for inheritance from adult males.

While myriad taboos and traditions still plague progress toward a more harmonized and gender-sensitive community where young women and girls have a voice, evidence shows that youths are using various strategies to overcome them. Use of experience-sharing events and the affirmative action on abolishment of practices such as FGM and early childhood marriage has witnessed increased number of enrolled students and changing livelihoods especially for women. The example of “sensitizing men” in Kenya established through training modules among youth livestock keepers is a behavioral change approach that will increase the recognition of the negative effects of patriarchy and discrimination against women among young men (Tavenner and Crane, 2019).

Besides, the tremendous opportunities presented by ICT in the field of livestock has been taken advantage of through use of various apps and internet tools. Evidence from Kenya suggest that youths can access educational materials through apps. This overcomes the information barrier associated with livestock markets, marketing of products and makes livestock farming attractive. ICT has significantly increased access to modern technologies and already attracting youths in countries such as Zambia and Ethiopia (Osti et al., 2015; ILRI, 2019; Okello et al., 2020; Daum et al., 2022). Perhaps, it will also address the gender issue associated with drudgery among young girls as it will bring in new technologies that solve energy problems such as use of biogas to reduce time taken to fetch firewood by girls in pastoral areas.

This study has successfully identified and analyzed various gender-youth nexus issues in livestock farming practices. The study's contribution to literature is a systematic synthesis of existing research on youth engagement in livestock production systems achieved through aggregating and analyzing findings from diverse sources. It contributes to a comprehensive understanding of the challenges and opportunities faced by youth in this context. The study is valuable to academics, policymakers, development practitioners, and stakeholders interested in opportunities and entry point to youth engagement, gender equity, and sustainable livestock production. It offers evidence-based recommendations and contributes to the broader understanding of youth inclusion in agriculture while aligning with the broader goal of promoting inclusive and sustainable agricultural practices.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The paper was conceptualized, co-written, and revised by all authors. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funded the publication of this work through grant number INV-009649/OPP1198373.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor declared a shared research partnership group [CGIAR] with the authors EN and CA.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

ADB.AYAF (2020). African Development Bank - Building today, a better Africa tomorrow. Available online at: https://www.afdb.org/en/african-youth-agripreneurs-forum/ayaf-2020 (accessed January 30, 2023).

Afande, F. O., Maina, W. N., and Maina, M. P. (2015). Youth engagement in agriculture in kenya: challenges and prospects. J. Cult. Soc. Dev. 7, 4–19.

African Development Solutions (2017). Pastoralist Youth Education Initiative (PYEI) Kenya - Sécheresse info. Nairobi: Kenya. Available online at: http://www.secheresse.info/spip.php?article100451 (accessed December 12, 2022).

African Union (2006). African Youth Charter African Youth Charter, Eastern Asia University Academic Journal. Addis Abbaba, Ethiopia: African Union.

Akall, G. (2021). Effects of development interventions on pastoral livelihoods in Turkana County, Kenya. Pastoralism. 11, 1–15. doi: 10.1186/s13570-021-00197-2

Akilapa, O., Farayola, C. O., Adebisi, L. O., Akilapa, O., and Gbadamosi, F. Y. (2020). Does innovation enhance youth participation in agriculture: a review of digitalization in developing country? Int. J. Res. Agric. For. 7, 7–14.

Ancey, V., Rangé, C., Magnani, S., and Patat, C. (2020). Pastoralist youth in towns and cities: Supporting the economic and social integration of pastoralist youth Chad and Burkina Faso. Doctoral dissertation, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

Bello, L. O., Baiyegunhi, L. J. S., Mignouna, D., Adeoti, R., Dontsop-Nguezet, P. M., Abdoulaye, T., et al. (2021). Impact of youth-in-agribusiness program on employment creation in Nigeria. Sustain. 13, 1–20. doi: 10.3390/su13147801

Bernard, T., Dercon, S., Orkin, K., and Taffesse, A. S. (2019). Parental aspirations for children's education: is there a “Girl Effect”? Experimental evidence from rural Ethiopia. AEA Pap. Proceed. 109, 127132. doi: 10.1257/pandp.20191072

Besada, H., Wheaton, W., Ben, O., and Tok, E. (2014). Phase I Study report : social cohesion and community based protection mechanisms in chad and Burundi. Res. Rep. 1, 69.

Bloom, D. E., Canning, D., and Malaney, P. N. (2000). Population dynamics and economic growth in Asia. Popul. Dev. Rev. 26, 257–290.

Chuta, N., Morrow, V., Pankhurst, A., and Pells, K. (2019). Understanding violence affecting children in Ethiopia: a qualitative study. Working paper.

Cotula, L., Toulmin, C., and Hesse, C. (2004). Land Tenure and Administration in Africa: Lessons of Experience and Emerging Issues. London: IIED.

Daum, T. (2019). Of bulls and bulbs: aspirations, opinions and perceptions of rural adolescents and youth in Zambia. Dev. Pract. 25, 29. doi: 10.1080/09614524.2019.1646209

Daum, T., Ravichandran, T., Kariuki, J., Chagunda, M., and Birner, R. (2022). Connected cows and cyber chickens? Stocktaking and case studies of digital livestock tools in Kenya and India. Agric. Syst. 196, 103353. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2021.103353

Diogo, B., Mai, F., Dominique, F., Laurent, K., Loic, L., Pritha, M., et al. (2022). Climate Change and Chronic Food Insecurity in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC, USA: African Department (Series). Report No.: DP/2022/016. doi: 10.5089/9798400218507.087

Eley, M. L., Owens, J. P., and Adjibi, Y. (2014). Songhaï Centers as Models for Promoting Sustainable Agriculture. (MEAS Case Study # 10). Report No.: 10.

Endris, G. S., Wordofa, M. G., Aweke, C. S., Hassen, J. Y., Hussien, J. W., Moges, D. K., et al. (2022). A review of the socio-ecological and institutional contexts for youth livelihood transformation in Miesso Woreda, Eastern Ethiopia. Cogent. Soc. Sci. 8, 2152210. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2022.2152210

Enns, C., and Bersaglio, B. (2016). Pastoralism in the time of oil: Youth perspectives on the oil industry and the future of pastoralism in Turkana, Kenya. Extr. Ind. Soc. 3, 160–170. doi: 10.1016/j.exis.2015.11.003

FAO (2018). Ethiopia's youth find hope in agricultural entrepreneurship | FAO Stories | Food and Agriculture Organization of the Unite Nations. Available online at: https://www.fao.org/fao-stories/article/en/c/1132999/ (accessed January 30, 2023).

FAO (2019). The future of livestock in Uganda: Opportunities and challenges in the face of uncertainty. Africa Sustainable Livestock 2050. Rome, Italy: FAO, 60. Available online at: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/ca5464en/ (accessed July 20, 2023).

Fareo, D. O., and Ateequ, W. (2020). Determinants of girl child education among the nomads in Nigeria. EAS J. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2, 138–145. doi: 10.36349/easjpbs.2020.v02i05.006

Gammino, V. M., Diaz, M. R., Pallas, S. W., Greenleaf, A. R., and Kurnit, M. R. (2020). Health services uptake among nomadic pastoralist populations in Africa: A systematic review of the literature. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 14, 1–23. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008474

Gebeyehu, D. T., Bekele, D., Mulate, B., Gugsa, G., and Tintagu, T. (2021). Knowledge, attitude and practice of animal producers towards antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance in Oromia zone, north eastern Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 16, e0251596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251596

Gusenbauer, M., and Haddaway, N. R. (2020). Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta-analyses? Evaluating retrieval qualities of Google scholar, PubMed, and 26 other resources. Res. Syn. Methods 11, 181217. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1378

Hebo, M. (2014). Evolving markets, rural livelihoods, and gender relations: the view from a milk-selling cooperative in the Kofale District of West Arsii, Ethiopia. Afr. Study Monogr. 48, 5–29. doi: 10.14989/185113

Holden, D. J., Messeri, P., Evans, W. D., Crankshaw, E., and Ben-Davies, M. (2004). Conceptualizing youth empowerment within tobacco control. Heal. Educ. Behav. 31, 548–563. doi: 10.1177/1090198104268545

Holechek, J. L., Cibils, A. F., Bengaly, K., and Kinyamario, J. I. (2017). Human population growth, african pastoralism, and rangelands: a perspective. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 70, 273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.rama.2016.09.004

Ika, L., and Saint-Macary, J. (2014). Special issue: why do projects fail in Africa? J. African. Bus. 15, 151–155. doi: 10.1080/15228916.2014.956635

Kaba, M., Ame, I., and Mariam, D. H. (2013). Extramarital sexual practices and perceived association with HIV infection among the borana pastoral community. Ethiop. J. Heal. Dev. 27, 25–32.

Kalliney, P. (2001). Cities of affluence: masculinity, class, and the angry young men. MFS Mod. Fict. Stud. 47, 92–117. doi: 10.1353/mfs.2001.0004

Kgosikoma, K., Lekota, P., and Kgosikoma, O. (2018). Agropastoralists' determinants of adaptation to climate change. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manage. 10, 488500. doi: 10.1108/IJCCSM-02-2017-0039

Kinati, W., and Mulema, A. A. (2018). Gender Issues in Livestock Production in Ethiopia A Review of Literature to Identify Potential Entry Points for Gender Responsive Research and Development. Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI. doi: 10.33259/JLivestSci.2019.66-80

Korir, G. K. (2018). Cultural practices contributing to girls' dropout rate in primary schools in kajiado county : a review of literature. Int. J. Adv. Res. Rev. 3, 10–15.

Leavy, J., and Hossain, N. (2014). Who wants to farm? Youth aspirations, opportunities and rising food prices. IDS Working Papers. doi: 10.1111/j.2040-0209.2014.00439.x

Lipton, M. (2005). The family farm in a globalizing world: The role of crop science in alleviating poverty. Discussion Papers 40. International Food Policy Research Institute. Washington, DC.

Lwanga-Ntale, C., and Owino, B. O. (2020). Understanding vulnerability and resilience in Somalia. Jamba J. Disaster. Risk Stud. 12, 1–9. doi: 10.4102/jamba.v12i1.856

Maendeleo Ya Wanawake Organisation (2011). Women and Conflict. Nairobi, Kenya: Soloh WorldWide Inter-Enterprises Ltd.

Maru, N. (2017). Youth perspectives on pastoralism: opportunities and threats faced by young pastoralists. Nat. Faune 31, 22–25.

Misunas, C., Erulkar, A., Apicella, L., Ng,ô, T., and Psaki, S. (2021). What influences girls' age at marriage in Burkina Faso and Tanzania? Exploring the contribution of individual, household, and community level factors. J. Adolesc. Heal. 69, S46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.09.015

Mkutu, K. A. (2008). Uganda: pastoral conflict and gender relations. Rev. Afr. Polit. Econ. 35, 237–254. doi: 10.1080/03056240802194133

MOALF (2018). Republic Of Kenya Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Irrigation Kenya Youth Agribusiness Strategy 2018-2022 Positioning the Youth at the Forefront of Agricultural Growth and Transformation “Vijana Tujijenge na Agribiz”. Available online at: www.kilimo.go.ke (accessed January 30, 2023).

Moyo, H. (2014). Gendered mourning and grieving rituals amongst the Jahunda people of Zimbabwe as a challenge to the pastoral care ministry of the church. Black Theol. 12, 213–229. doi: 10.1179/1476994814Z.00000000036

Mueller, B., Acero, F., and Estruch, E. (2017). Creating employment potential in small-ruminant value chains in the Ethiopian Highlands. FAO Animal Production and Health. Rome: FAO (Working Paper). Report No.: 16.

Mugeere, A., Barford, A., and Magimbi, P. (2021). Climate change and young people in Uganda: a literature review. J. Environ. Dev. 30, 344–368. doi: 10.1177/10704965211047159

Munishi, E. J. (2013). Rural-Urban Migration of the Maasai Nomadic Pastoralist Youth and Resilience in Tanzania : Case Studies in Ngorongoro District, Arusha Region and Dar es Salaam City. Freiburg im Breisgau: Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg.

Mutua, E., Bukachi, S., Bett, B., Estambale, B., and Nyamongo, I. (2017). Youth participation in smallholder livestock production and marketing. IDS Bull. 48, 95–108. doi: 10.19088/1968-2017.129

NEPAD (2022). AUC and AUDA-NEPAD Second Continental Report on the Implementation of Agenda 2063. Midrand, SA: NEPAD.

Njeru, L. K., and Gichimu, B. M. (2014). Influence of access to land and finances on Kenyan youth participation in agriculture: a review. Int. J. Dev. Econ. Sustain. 2, 1–8.

Odhiambo, M. O. (2013). The ASAL Policy Of Kenya : releasing the full potential of arid and semi-arid lands—an analytical review. Nomad. People. 17, 158–165. doi: 10.3167/np.2013.170110

OECD (2018). The Future of Rural Youth in Developing Countries. Paris, France: OECD Publishing, 100. Available online at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/the-future-of-rural-youth-in-developing-countries_9789264298521-en (accessed November 11, 2022).

Okello, D. O., Feleke, S., Gathungu, E., Owuor, G., and Ayuya, O. I. (2020). Effect of ICT tools attributes in accessing technical, market and financial information among youth dairy agripreneurs in Tanzania. Cogent. Food Agric. 6, 1817287. doi: 10.1080/23311932.2020.1817287

Opiyo, F., Wasonga, O. V., Nyangito, M. M., Mureithi, S. M., Obando, J., Munang, R., et al. (2016). Determinants of perceptions of climate change and adaptation among Turkana pastoralists in northwestern Kenya. Clim. Dev. 8, 179–189. doi: 10.1080/17565529.2015.1034231

Osti, A., van t Land, J., Magwegwe, D., Peereboom, A., van Oord, J., and Dusart, T. (2015). The future of youth in agricultural value chains in Ethiopia and Kenya Report. Available online at: http://agriprofocus.com/agriprofocus#sthash.EnHsicVn.dpuf (accessed July 20, 2023).

Ouko, K. O., Ogola, J. R. O., Ng'on'ga, C. A., and Wairimu, J. R. (2022). Youth involvement in agripreneurship as Nexus for poverty reduction and rural employment in Kenya. Cogent Soc. Sci. 8, 2078527. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2022.2078527

Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372, n160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n160

Quisumbing, A. R., Meinzen-Dick, R., Raney, T. L., Croppenstedt, A., Behrman, J. A., and Peterman, A. (2014). “Closing the knowledge gap on gender in agriculture,” in Gender in Agriculture, eds. A. Quisumbing, R. Meinzen-Dick, T. Raney, A. Croppenstedt, J. Behrman, A. Peterman (Dordrecht: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-8616-4

Rabinovich, A., Heath, S. C., Zhischenko, V., Mkilema, F., Patrick, A., Nasseri, M., et al. (2020). Protecting the commons: Predictors of willingness to mitigate communal land degradation among Maasai pastoralists. J. Environ. Psychol. 72, 101504. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101504

Rhiannon, P., Geneviève, A. B., Sabdiyo, D., and Gabriela, Q. (2014). Unleashing potential: gender and youth inclusive agri-food chains. Community workshop session, Guinea Bisseau (KIT working papers). Available online at: http://www.snv.org/ (accessed December 15, 2022).

Ruben, R., Dekeba Bekele, A., and Megersa Lenjiso, B. (2017). Quality upgrading in Ethiopian dairy value chains: dovetailing upstream and downstream perspectives. Rev. Soc. Econ. 75, 296–317. doi: 10.1080/00346764.2017.1286032

Scott-Villers, P., Wilson, S., Kabala, N., and Kullu, M. A. (2016). Study of Education and resilience in Kenya's Arid and Semi-Arid Lands Learning for Peace. Nairobi, Kenya: UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office.

Senga, M., and Kiilu, R. M. (2022). Understanding the effect of educational attainment and unemployment on youth engagement in conflicts in Machakos County, Kenya. Afr. Educ. Res. J. 10, 46–53. doi: 10.30918/AERJ.101.22.003

Solomon, A., and Assegid, W. (2003). Livestock marketing in Ethiopia : A review of structure, per- formance and development. Socio-economics and Policy Research Working Paper. Report No.: 52.

Statista (2022). Cattle population in Africa as of 2020 by country. Farming. Available online at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1290046/cattle-population-in-africa-by-country/ (accessed November 16, 2022).

Sulo, T., Chumo, C., Tuitoek, D., and Lagat, D. (2012). Assessment of youth opportunities in the dairy sector in Uasin Gishu county, Kenya. J. Emerg. Trends Econ. Manag. Sci. 3, 332–338.

Tavenner, K., and Crane, T. (2019). “Implementing “gender equity” in livestock interventions,” in Gender, Agriculture and Agrarian Transformations, ed. C. Sachs (Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge), 147–61. doi: 10.4324/9780429427381-9

Tian, X. (2017). Ethnobotanical knowledge acquisition during daily chores: the firewood collection of pastoral Maasai girls in Southern Kenya. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 13, 1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13002-016-0131-x

Úcar, M. X., Jiménez-Morales, M., Soler Masó, P., and Trilla Bernet, J. (2017). Exploring the conceptualization and research of empowerment in the field of youth. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth. 22, 405–418. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2016.1209120

United Nations (2004). World Youth Report: The Global Situation of Young People. Rome, Italy: United Nations.

United Nations (2022). Young People's Potential, the Key to Africa's Sustainable Development | Office of the High Representative for the Least Developed Countries, Landlocked Developing Countries and Small Island Developing States. News. Available online at: https://www.un.org/ohrlls/news/young-people's-potential-key-africa's-sustainable-development (accessed November 9, 2022).

Vincent, K. (2022). A review of gender in agricultural and pastoral livelihoods based on selected countries in west and east Africa. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 6, 908018. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2022.908018

Wagaman, M. A. (2011). Social empathy as a framework for adolescent empowerment. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 37, 278–293. doi: 10.1080/01488376.2011.564045

Wondim, A. K., and Kefale, E. (2018). Gender and youth challenges and opportunities in rural community: the case of Goregora, West Dembia district of North West Ethiopia. J. Agric. Ext. Rural Dev. 10, 108–114. doi: 10.5897/JAERD2018.0958

Yami, M., Feleke, S., Abdoulaye, T., Alene, A. D., Bamba, Z., Manyong, V., et al. (2019). African rural youth engagement in agribusiness: achievements, limitations, and lessons. Sustain. 11, 1–15. doi: 10.3390/su11010185

Yitbarek, S., Wogasso, Y., Meagher, M., and Strickland, L. (2022). “Life skills education in ethiopia: afar pastoralists' perspectives,” in Life Skills Education for Youth. Young People and Learning Processes in School and Everyday Life, eds. J. DeJaeghere and E. Murphy-Graham (Cham: Springer) 245–65. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-85214-6_11

Keywords: youth, gender, participation, livestock, ICT, empowerment, traditions and culture

Citation: Nchanji EB, Kamunye K and Ageyo C (2023) Thematic evidencing of youth-empowering interventions in livestock production systems in Sub-Sahara Africa: a systematic review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7:1176652. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2023.1176652

Received: 28 February 2023; Accepted: 04 September 2023;

Published: 25 September 2023.

Edited by:

Renee Marie Bullock, International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), KenyaReviewed by:

Kassa Tarekegn Erekalo, University of Copenhagen, DenmarkHenry Jordaan, University of the Free State, South Africa

Copyright © 2023 Nchanji, Kamunye and Ageyo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eileen Bogweh Nchanji, ZS5uY2hhbmppQGNnaWFyLm9yZw==

Eileen Bogweh Nchanji

Eileen Bogweh Nchanji Kelvin Kamunye

Kelvin Kamunye Collins Ageyo1

Collins Ageyo1