95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Food Syst. , 17 April 2023

Sec. Social Movements, Institutions and Governance

Volume 7 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2023.1090682

This article is part of the Research Topic Critical Praxis and the Social Imaginary for Sustainable Food Systems View all 14 articles

The study of non-profit food organizations has focused primarily on food policy, urban gardens, coops, and farmers' markets in cities. Despite significant research on these kinds of food non-profits, research specifically on non-profit farms – organizations that produce food for local communities – is nearly non-existent. We argue that non-profit farms are a category that deserves more research attention. This article asks what services non-profit farms see themselves as providing to their communities, along with a supply of local food. We focus on the missions of non-profit farms, using farms on the GuideStar database of non-profit organizations. We also examine, through interviews and website analysis, the role of non-profit farms in the Hudson Valley, long a hub of non-profit farms. We conclude that local non-profit farms are hybrid organizations that perform services that are similar to local community non-profits, supporting local social welfare, environment, education, and community development roles, along with providing local food access and, in some cases, supporting food system change.

Several hundred farms in the United States are organized and governed as non-profits. Yet, despite the many critiques of industrial agriculture as driven by the logic of profit, and the many analyses of alternative food networks as seeking to overcome this logic, little attention has been paid to the role of farms that are “non-profits”: that is, organized specifically around a mission rather than for profitmaking. For this reason, we argue that non-profit food organizations in the US are a category that deserves more research attention, looking specifically at how their mission-based mode of governance (Bulkeley and Newell, 2015) impacts their role in the local food system. Part of a larger study of US food non-profits, this analysis looks specifically at non-profit farms that produce food for local communities. We analyze a database we have compiled of nearly 300 non-profit farms, to understand the role of these farms in the US alternative food system. In addition, we examine, through interviews and website analysis, the missions and community role of non-profit farms in the Hudson Valley, long a hub of non-profit farms. Looking at the conceptualizations of alternative food economies and modes of governance related to alternative food systems, we ask what role non-profit farms play as “alternative modes of governance” (DuPuis and Gillon, 2009) in “alternative food networks” (Goodman et al., 2012) and “civic agriculture,” (Lyson, 2004; Donald et al., 2010). Through our analysis of the GuideStar database of non-profit farms, and local interviews in the Hudson Valley of New York, we conclude that non-profit farms' missions are varied and extend beyond – and sometimes besides – the alternative food movement emphasis of food system change (Nemes et al., 2023). Our data analysis and interviews indicate that non-profit farm missions tend to mirror those of non-profit organizations as a whole, while contributing to local food production. In other words, non-profit farms see themselves as meeting a wide-ranging set of community needs. While non-profit farms are sometimes explicitly part of local food movements, that is often a secondary role.

Critics of the industrial food system identify its productivist logic and emphasis on maximizing profit as harmful to both the environment and to human health (Magdoff et al., 2000; De Schutter, 2010). In the United States, those seeking to reform the industrial food system have built numerous alternative food initiatives (Allen et al., 2003) to reform how Americans produce and consume food. Those initiatives have also engendered a field of academic literature analyzing their activities and impact. Initiatives in Europe (Renting et al., 2003; Goodman et al., 2012) and in particular peasant initiatives around the world (Holt Giménez and Shattuck, 2011) have worked toward changing the global food system and have been topics of analysis. These research projects have examined how alternative food systems go about creating “alterity” – systems of economic production that are based less on profit and aim to meet social needs of community, healthy food access, resilience, equity, etc. – through “decommodified” (Hinrichs, 2000; Goodman and Goodman, 2009), “communified” (Warde, 1997), “nourishing” alternative food networks (Whatmore and Thorne, 1997). Many analyses point to the ways alternative food networks are built around values that create a “normative landscape” (Goodman et al., 2012) or at least tempers productivist logics (Hendrickson and Heffernan, 2002; Goodman et al., 2012; Hendrickson, 2015; Watts et al., 2017; Rosol, 2020). Yet, some critics have challenged the view that alternative food networks can create values-based exchange systems, arguing that land markets force farmers to focus on profit (Guthman, 2004). According to this perspective, alternative food production becomes “conventionalized,” organized around profit logics. Recent scholarship has challenged this critique, arguing that alternative food systems can be hybrid, incorporating both profit and normative goals, neoliberal as well as radical values (Misleh, 2022; Nemes et al., 2023).

Given this long conversation in the academic literature about alternative food systems, values, and profit, it is surprising that no study has examined a group of farms that exist legally outside of the logic of profit and specifically for normative purposes. Non-profit farms, organized as 501(c)3 “public charities,” act according to a different “mode of governance,” (Bulkeley and Newell, 2015). Instead, non-profit charities structure their decision-making based on commitment to a social mission. Yet, studies of alternative food systems have paid little attention to farms organized as non-profits. Given the burgeoning interest in food system governance (DuPuis and Gillon, 2009; Hospes and Brons, 2016; Andrée et al., 2019), it is surprising that no study has looked at non-profit governance, either at the system or individual organizational level. While examinations of food system actors have included food non-profit organizations, none have directly addressed their specific governance structure. While some investigators have focused on modes of governance at the network level (coops, food hubs, CSAs, etc.) in the creation of organizational alterity (Renting et al., 2003; Watts et al., 2017; Rosol, 2020), none have addressed the fact that some of these organizations are non-profits. For example, Allen et al. (2003) study of California alternative food initiatives did not explicitly consider non-profit governance as a significant factor in the alterity of these organizations, despite the fact that a number of them were organized as non-profits. Rogus and Dimitri, in their survey of urban agriculture, treated private and non-profit farms as one population, generalizing from those combined findings about the nature of all urban agriculture (Rogus and Dimitri, 2015). They note that a substantial number of urban farms are non-profit, but they do not explore the ways this status affects the actions and mission of these farms. This lack of attention to the alternative governance structure of non-profit farms is surprising given that many studies of the alternative food system draw upon ideas about the social embeddedness of capitalism (Granovetter, 1973; Polanyi, 2001), and many analyses of the alternative food system have noted the ways that alternative economies are embedded in social, particularly local, institutions (Lyson, 2004; Jarosz, 2008; Goodman et al., 2012; Hinrichs, 2013).

A non-profit is “a group organized for purposes other than generating profit and in which no part of the organization's income is distributed to its members, directors, or officers.”1 Studies of non-profits recognize the fact that they are specifically governed according to a social mission (Renz et al., 2022). For example, Boris et al. (2017, p. 3) describes the role of non-profits in civil society as “fostering community engagement, and promoting and conserving civic, cultural and religious values.” According to the National Association of Non-profits, these organizations are the “building blocks of democracy…where Americans come together to solve problems” (National Council of Nonprofits, 2019). Non-profits are defined primarily through tax law in the US and in other countries, and those laws vary from country to country, making comparisons difficult. In addition, most studies of non-profits focus on the United States and Europe, in part due to the fact that international charities tend to register in those countries that are the primary source of donor funds (Renz et al., 2022). This particular study focuses on non-profit farms in the United States. In the US, non-profits are tax-exempt under federal tax law, in that their income – from enterprises or donations – is not taxed but is used to meet the mission of the organization. Non-profit organizations are generally run by a director who is responsible to a board (Renz et al., 2022).

Besides studies of cooperatively organized farms (Rosol, 2020) few have looked at alternative modes of governance at the farm level. Non-profit farms also fall – surprisingly – into the cracks on research about civic agriculture (Lyson, 2004; Hinrichs and Lyson, 2007; Hinrichs, 2013), civic markets (DuPuis and Gillon, 2009), shortening food chains (Renting et al., 2003), and re-localizing food systems (Hendrickson and Heffernan, 2002). Despite a large and growing literature on the civil society role of farms, and a concomitant literature on the role of non-profits as the backbone of civil society–there has been little or no research looking at the contribution of non-profit farms to civic agriculture or alternative food systems. While urban gardens and agriculture have received a great deal of research attention (see Golden, 2013; Dimitri et al., 2015), almost no research has been done on those organized as non-profits. Even less work has been done on non-profit farms outside of urban areas. On the other hand, several studies note the non-profit status of various local food system organizations, including food hubs (Hinrichs, 2013), food cooperatives (Moragues-Faus et al., 2020), farm-to-institution organizations (Richman et al., 2019) and food policy alliances (Sussman and Bassarab, 2017).

Building on these discussions, we ask: to what extent does non-profit organization, as an alternative mode of governance, affect a farm's ability to function according to values-based goals? And, what values do non-profit farms contribute to the “normative landscape” (Goodman et al., 2012) of alternative food systems in general? Are these farms part of the alternative food movement, challenging the existing food system and seeking to build alternatives “that are environmentally sustainable, economically viable, and socially just” (Allen et al., 2003)? Do non-profit farms contribute to the efforts to re-regionalize and re-localize the food system? Do these farms meet community needs, make local food systems more resilient, and build local infrastructure? Our goal in this paper is therefore to distinguish this type of farm both from other alternative food non-profit organizations, and from the local private alternative food system. Both in terms of how these farms serve their local communities and how their modes of governance affect their role in local food systems, we ask to what extent do non-profit farms, as an alternate mode of food governance, contribute to and support alternative food systems. In other words, there is a great deal of work to be done on non-profit food and farm organizations as part of the Third Sector (Etzioni, 1973). This study is the first in a larger study of the role of non-profit organizations in alternative food networks.

In order to understand the role of non-profit farms, we compiled a list of non-profit farms in the United States. Our list of 295 farms represents all of the farms that submit IRS form 990 tax forms to the Internal Revenue Service that we could find on the GuildStar database of 990 tax forms, and which reported income.2 Any non-profit organization with over $50,000 of income a year is obliged to submit these forms. Because these farms fall into a number of non-profit categories, it was necessary to do more than simply sort non-profits by taxonomic indexes. Instead, we carried out significant examination and sorting of organizations by topic, by name and by searching websites. Through this process, and because non-profit farms categorize themselves along so many different missions, it is likely that some farms did not make our list. Therefore, our list of farms represents nearly all of the farms in the United States that have over $50,000 in annual income, along with those with less income that report to the IRS. We are confident that our retrieval and examination process enabled us to build a database that represented the vast majority of larger food-growing non-profits in the United States. We have confined our study to the United States for two reasons: first, because non-profit laws and regulations differ from one country to the next, so that conclusions about non-profits in one country is likely to differ from another country and, second, because our access to data on non-profit organizations is restricted to the GuideStar list of non-profits in the United States (GuideStar USA, 2022).

Given that there is no overview of non-profit farms in the United States, this first study will provide a general sector analysis examining the existence and status of these farms. We will then look at non-profit farms as non-profits, to understand to what extent their non-profit status affects their activities. Then we will look at non-profit farms as farms, to understand their role as food producing organizations. Next, we will address the question of the role of non-profit farms in food infrastructure and, subsequently, in alternative food networks. We will examine to what extent the ways that non-profit farms are meeting local human service needs are or are not congruent with a role in supporting alternative food networks. We conclude by finding that non-profit farms are organized around a wide variety of missions, meeting local expectations of non-profit services like environmental preservation, food access and social welfare while also, in some cases, supporting food system change.

Much of the research on the non-profit sector – its growth, structure and change – comes from analysis of IRS form 990s required by non-profit organizations. We defined the category “non-profit farm” as an agricultural production organization (1) which qualifies as 501c3, and has submitted IRS 990 tax forms to the government, (2) produces food for donation or sale, and (3) is not a farmland trust or a community garden, an organization that makes land available to private farmers or gardeners. We compiled a list of non-profit farms in the United States from the GuideStar list of non-profits (GuideStar Search) which is the most comprehensive and up to date list of non-profit organizations and is the list most commonly used to analyze non-profit organizations. Because farms were not under a particular category, we also carried out internet searches of non-profit farms, as well as making sure that non-profit farms directed by underrepresented groups were found in the GuideStar list. Because many non-profits that make < $50,000 also sometimes report on IRS 990 forms, our list of non-profit farms includes a number of farms (46) that report < $50,000. We omitted farms that did not report income on their most recent IRS 990 form, since it would be unlikely that those farms would be actively growing food either for contribution or sale.3 The GuideStar list does not represent one calendar year. Instead, farms on the list are from years 2019–2021. The GuideStar list, while reporting data from several different years, is the best data available on non-profits in the United States. Based on these databases and searches, we discovered 295 non-profit farms that reported income on the GuideStar list.

Through web searches and IRS 990 forms, along with information provided in interviews, we also compiled a list of non-profit farms in the Hudson Valley. Some of these farms were not represented on the GuideStar list, since their income was < $50,000/year during this period. We researched each of these farms for available data on GuideStar as well as through information reported on their websites. We also interviewed eight of these farms in 2019, focusing in particular on their mission and governance. This enabled us to gather information not available on databases.

There are more than 1.8 million organizations registered as non-profits in the United States (Independent Sector, 2020). Those required to report income and assets to the IRS bring $2.6 trillion in revenues and nearly $6 trillion in assets to the US economy, representing 5.6% of the country's gross domestic product (National Center for Charitable Statistics, 2020) and 8% of the total US labor force (Gazley, 2016). Up until the COVID pandemic, the non-profit sector was growing, both in terms of organizations and revenue. In fact, the number of non-profits grew 75% between 2000 and 2016 (National Council of Nonprofits, 2019). Growth has slowed since then (National Center for Charitable Statistics, 2020). However, over the longer term, non-profits have become, and are likely to continue to be, a significant actor in American civil society (Boris et al., 2017). Non-profits “are a vital source of civil society…Their basic role as enablers of public engagement and promoters of the common good is the cornerstone of our pluralistic democracy” (Boris et al., 2017, p. 1). A more critical perspective on the turn to non-profits sees it as part of neoliberal arrangements, where government has been “hollowed out,” in response to the perceived or real shortcomings of government or market institutions. Whether or not the reason is “government failure” or “market failure,” the last few decades have been characterized as communities increasing their dependence on the non-profit sector to provide various community services, including food access (Salamon, 2002; McCarthy and Prudham, 2004; Allen and Guthman, 2006). Other services include education, community health, environmental protection and social welfare (National Center for Charitable Statistics, 2020).

The first observation one can make about these farms is that they vary greatly in terms of history, finances, origin, staff and resources. In our web research, we found that many of these are old, historic farmsteads preserved by their towns. Others are founded on former estates or former institutions. A few are the vision of one or two people, while others are the products of larger community efforts. Their founding years range from 1961 to 2019, and they differ greatly in their financial resources and their missions. For example, these farms differ greatly in terms of their financial assets (Figure 1). Some farms have few, even negative assets, while the wealthiest farms have assets over $10 million. One reason for this discrepancy is landownership. Farms that own land, especially in areas with high land values, have high value assets.

Nevertheless, non-profit farms share some financial characteristics with non-profits as a whole. Looking specifically at the non-profit farms that reported more than $50,000 in income in the GuideStar list (249 farms) we can compare them to published figures on non-profits as a whole (Table 1).4 The budgets of non-profits in general vary widely, with 5% having expenses of more than $10 million dollars a year, 25% with between $500,000–$9.9 million dollars and 67% with a budget of < $500,000 a year (National Center for Charitable Statistics, 2020). In other words, non-profits as a whole vary widely in terms of income. Non-profit farms, in comparison, tend to have fewer very large and very small non-profit budgets (expenses), with only 0.3% having over $10 million and 63% with budgets < $500,000. 36% of non-profits farms fall into the middle range in terms of budgets. This indicates that non-profit farms tend to be larger than the smallest non-profits as a whole, but not as large as the largest non-profits. The cost of land maintenance and stewardship is likely to mean that non-profit farms must maintain higher budgets than non-profit organizations as a whole.

While taxonomies categorizing what non-profits do vary, non-profit organizations as a whole tend to be broadly characterized under eight basic groups: (1) arts and culture; (2) education; (3) environment and animals; (4) health and hospitals; (5) public services; (6) international; (7) foundations and (8) religion (National Council of Non-profits, 2016). Under this taxonomy, the category “agriculture” falls under “environment and animals.” However, it is possible to find non-profit farms characterizing themselves along all of the eight major categories, as will become evident in the analysis in the next section.

It is difficult to compare non-profit farms as an economic sector to for-profit farms. First, given the types of services non-profit farms provide, it appears that much of the income on these farms comes from programs and donations not from sales of food, as opposed to income from for-profit farm operations which mostly comes from selling what they grow. While data on income from non-profit farms in GuideStar represents different years, it can give us some indication of the total amount of income from these farms and the general percentage of income from donations. For the 295 farms that reported income in the years represented in the GuideStar list, the total income was $296,255,980 while contributions represented 66% of that amount, $196,839,104. Table 2 represents the income categories of for-profit and non-profit farms. It is clear that non-profit farms are represented at all income levels while for-profit farms mostly are making incomes of < $100,000 per year. However, this data is not entirely representative, since non-profit farms that make < $50,000 per year are not required to file with the IRS. It is likely that the number of non-profit farms making < $50,000 a year is significantly larger than the 45 farms in this category that have filed with the IRS in recent years. In fact, according The Urban Institute, only slightly more than one third of all non-profits report to the IRS each year (National Center for Charitable Statistics, 2020). Because non-profit farms have somewhat higher income in the middle range, it is likely that they represent somewhat more than a third, but not that much more.

Our analysis of the IRS 990 list reveals that non-profit farms are spatially concentrated in the Northeastern region of the US, although California also has a large number of non-profit farms (Figure 2). The concentration of non-profit farms in the Northeast is likely related to the extent of farm loss and development threat experienced in this region over the last 50 years. This fits in strongly with one of the major missions of non-profit farms: to preserve local agriculture and greenspace.

Our analysis indicates a concentration of non-profit farms in certain states. In fact, the states with the highest number of non-profit farms tend to have a higher percentage of urban land use than states with fewer non-profit farms. However, there are many highly urbanized states that do not have a high concentration of non-profit farms (Table 3). In addition, several more rural states, such as Ohio and Washington, have a large number of non-profit farms, indicating that reasons for concentration sometimes have to do with factors beyond urbanization. Nonetheless, the largest percentage of non-profit farms are concentrated in the Northeast Region (Figure 2), which is the most urbanized part of the US.

The location of non-profit farms is somewhat, but not entirely, related to those places in the United States with well-developed food infrastructure. A comparison of states ranked highly for food infrastructure by the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) with non-profit farm hub states indicates that those states are not necessarily correlated with strong statewide food infrastructure. Statewide food infrastructure, as measured in the UCS rankings, includes conventional organizations such as farm bureaus. In part, this has to do with the fact that non-profit farms tend to be concentrated in states that, with the exception of California, are not the top agricultural states. However, states with a high number of non-profit farms are also not necessarily located in states with significant alternative food infrastructure, as measured in the UCS “community food systems” ranking. Only three of the ten top non-profit farm hub states are in the top 10 states in terms of alternative food infrastructure, measured by the number of farmers markets, food policy councils/hubs/networks, composting facilities and heathy food retailers.5 These data indicate that, while non-profit farms often have missions like those of alternative food system organizations, the presence of non-profit farms is not necessarily associated with alternative food systems. While this data is not conclusive in terms of the contribution of non-profit farms to the social infrastructure of civic agriculture as a whole, it does indicate that states with high concentrations of non-profit farms are not necessarily associated with states that have strong alternative food networks.

A look at the missions of non-profit farms helps provide an answer as to why non-profit farms are not major contributors to non-profit food infrastructure in many regions. We are defining “mission” as the primary and secondary subject areas listed in IRS 990s. Based on that analysis, we find that people establish farms as non-profits to fulfill a number of different missions. Non-profit farms' missions fall into the following categories:

1. Agriculture, General (29%): a number of farms identified their mission as “agriculture” but did not specifically identify in the IRS 990 forms with alternative food networks or community food systems. In these cases, non-profit farms are providing food for local communities and are therefore “alternative” in that they are part of local food systems. However, these farms did not identify themselves with the alternative food network community.

2. Education (24%): many non-profit farms identify their main mission as educational. In many cases, this means that their primary mission is environmental education, often providing summer camps for children as well as historical education about the role of agriculture in the region. Farms that specifically listed alternative agriculture or food systems as their secondary subject area/mission we placed in the alternative food networks category. However, some of these farm education programs may teach about sustainable food systems as part of their environmental education mission while not identifying it in their IRS 990 form.

3. Alternative Food System (22%): these farms specifically identify with alternative food systems. These farms specifically identify with food justice, youth organizing, community food systems and other missions that seek food system change.

4. Social Welfare (14%): many farms identify their primary mission as social welfare. These are farms that focus on providing jobs and food for low-income and marginalized communities. In some cases, the mission of these farms is rehabilitation of former inmates and/or training for those differently-abled.

5. Environment and Farmland Preservation (11%): a number of farms identify missions closer to environmental and conservation goals associated with farmland preservation as land. These farms also grow food but were founded primarily as a way to preserve a farm under threat of development or as a way to create greenspace for a community. These organizations function closer to nature preserves.

Figure 3 indicates that non-profit farms have a wide variety of missions, most of which are not specific to alternative food networks. We defined farms that defined one of their missions as either community agriculture, sustainable food systems, food justice or food sovereignty as alternative food networks. Other definitions of alternative food networks might change these results. For example, we categorized all non-profit farms that defined their mission as food assistance in the “social welfare” category. Others might see providing fresh food to marginal populations as a major aspect of food justice and food sovereignty. If one categorized alternative food systems as including general agriculture/local food systems, farmland preservation, and environmental education, then nearly all of these organizations would qualify as members of alternative food networks. However, like Allen et al. (2003) we find it is important to distinguish between those alternative organizations providing local food access and those seeking system change.

If we look at non-profit farms as non-profits, we see that their missions are very close to local non-profit organizations as a whole. Non-profit farms provide the same kinds of services to their communities as many other local non-profits: social welfare, education, environmental protection and historical preservation. In national analyses of non-profit missions, as noted above, non-profit farms fall under the environment category. This fact makes it clear that non-profit farms are hybrid organizations that function both as non-profits and as members of local food systems. Like many non-profits (and many farms) their status as alternative or conventional is less than clear.

Our interviews and examination of websites in the Hudson Valley confirmed many of these findings. We found that many non-profit farms in the Hudson Valley were founded to meet a wide variety of missions and goals. While 990 forms allow for a general analysis of the role of non-profit farms in their regions, they do not provide information on more specific issues related to these farms. We gathered interviews with 8 non-profit farms in the Hudson Valley and did a survey of IRS 990s and websites of other non-profit farms in the Hudson Valley, for a total of 17 farms. The interviews covered a wide range of topics, looking at mission themes, presence or absence of particular governance structures, source of income, organizational collaborations, intended audience and land provenance.

Our analysis of Hudson Valley non-profit farms does indicate that they play a major role in the local food landscape that is the Hudson Valley. Besides the iconic Stone Barns, which has a more national alternative agriculture focus (Barber, 2014; Francis, 2017) the Hudson Valley contains fifteen other non-profit farms.

Generally speaking, the organizations interviewed have both much in common and are also quite distinct from one another, with different structure in terms of history, land ownership, leadership and governance structure, mission and finances. They also vary a lot in age (from 5 to 48 years old, median 13 years), mission, stability and focus. However, these farms also have a lot in common. Commonalities between many of the organizations include: preserving farmland, a focus on CSAs, an emphasis on farm-based education, and the increasing importance of social justice and/or food access.

For many non-profit farms in the Hudson Valley, the organizational mission includes environmental goals such as landscape preservation and community recreation as well as growing food (Table 4). Many of these farms also offer education programs, from culinary training to summer camps. In this way, non-profit farms in the Hudson Valley share many characteristics with the approximately 40 nature preserves and 18 state parks in the Hudson Valley region that have been established as green space, recreation, historical, education and watershed protection landscapes. In some cases, Hudson Valley non-profit farms' focus on greenspace conservation and environmental education is closer to the mission of nature preserves than to either for-profit farms or urban non-profit farms. These environmental education and preservation missions are intertwined with their activities to grow and provide access to fresh food. As a result of this closer link with environmental goals, some non-profit farms in their mission statements and websites emphasize farming practices that protect local watersheds, such as improving soil health and pasture management as a form of green infrastructure to manage water cycles. These farms are therefore contributing to local communities by providing a variety of ecosystem services.

Table 4. Missions (multiple) of Hudson valley non-profit farm organizations.6

Many of the non-profit farms in the Hudson Valley were established as part of larger greenspace and farmland preservation initiatives. The specific goal for founding many of these farms was therefore to protect land otherwise threatened by development. For many of them, preserving greenspace is a goal laid out in their mission, as stated, for example, in the Rockland Farm Alliance's mission statement to “promote sustainable agriculture in Rockland County by protecting and revitalizing farmland.” Frequently these farms also function as recreational parkland. Many of the farms also have hiking trails and offer other forms of community recreation, more similar to a community nature preserve than to a private for-profit farm.

At least five of the eight organizations interviewed identified preservation and sustainability of farmland as a key aspect of their mission. In the case of non-profit farms in the Hudson Valley, it is unclear to what extent farmland preservation and links to the alternative food movement developed in tandem with their founding or if these farms enrolled themselves in the alternative food movement as their greenspace mission evolved. Some of these farms focus on providing food for the local community and/or to local food banks, as well as food and farm education, without active participation in larger-scale food system change. Others, such as Glynwood and Stone Barns, see themselves as leaders in the development of alternative food systems in the region. On the other hand, some interviews indicated a mission that was closer to maintaining the history of agriculture in the Hudson Valley, as opposed to representing the alternative food movement. Therefore, some farms, rather than aligning with the alternative food movement, see themselves primarily as maintaining farm vitality in the Hudson Valley region and preserving farmland in the community.

Despite these differences, nearly all of the farms interviewed had or currently have a CSA/food share program. The proliferation of CSAs on both non-profit and private farms in the Hudson Valley, along with the proliferation of farms seeking access to burgeoning local farmers markets, has created strong competition between non-profit and for-profit farm CSAs for committed consumer members. As a result, some of the farms interviewed were considering phasing out or have phased out their CSA. Reasons include a decline in membership and financial challenges. Nevertheless, the 2019 pandemic created a rush on CSAs, leading to all CSAs in the region being sold out early in the season. This may have led a number of these farms to reconsider canceling their CSAs, at least for the time being.

Three of the eight organizations interviewed use the word “education” directly in their mission statement. All but two of the organizations noted education as a main part of their programming. Five organizations work to educate children, and three of these also have educational programming for adults; the other two educate families and adults, respectively. Of the organizations that work with children, some work with school children on food-based education in school districts that have a high proportion of students on subsidized lunch programs. These food-based education programs emphasize the use of produce grown at the farm in the school lunches and tasting activities for the children. Additionally, a few of the organizations cited “hands-on education” as part of their programming. Other educational programming included farm camps, vet tech training, educational care of animals, teacher education and nutrition education. It is also worth noting that these education programs make up a large portion of some of the organizations' budgets and are often grant-funded. This is more typical of nature preserve programming.

Interestingly, two of the organizations interviewed and three more in our web-survey mentioned the support of art and artists as part of their mission. This is more in keeping with the tradition of local non-profits in the Hudson Valley, including nature preserves. Arts philanthropy in the region is high, and therefore a non-profit seeking funds for art is likely to jive with local giving interests.

Almost all the organizations interviewed identified social justice as an important aspect of their mission, whether it is included in the written statement or not. A number of the organizations we interviewed are reconsidering their mission in terms of expanding their social justice mission.

There are several aspects of non-profit farms that make them closer, in terms of organizational structure, to non-profits than to for-profit farms or food policy non-profits. In particular, governance structures for the farm were quite similar to other non-profits, especially those dedicated to the conservation of greenspace in the Hudson Valley. The number of people on the boards range from 8 to 17. There's a spectrum of relationships that organization directors/managers have with their boards, ranging from working boards that are involved in the everyday details to oversight boards that are primarily helping to ensure that the organization is keeping to its mission and financial/federal responsibilities. A number of farms interviewed have an Executive Director separate from the Farm Manager who is in charge of farm production.

The relationship between managers and boards was also closer to that of a non-profit nature preserve than to a private farm. However, all of these farms had a person in a leadership role. Three out of the eight organizations have founders that also serve as the leaders of the organization. For the rest of the organizations, there is an Executive Director running the organization with support from the board. Generally speaking, younger organizations tend to have working boards with a more direct relationship between the founder and Executive Director, whereas the older organizations tend to have oversight boards with more autonomy for the Executive Director. Even though we did not specifically ask about fundraising responsibilities, a number of the boards also have a role in terms of fundraising and development. Like many non-profits, Boards are expected to be major contributors. For example, one interviewee indicated that they asked their board members give/get financial contributions, stating that “the best board member has time, talent and treasure. This is hard to come by.”

In terms of staffing, these farms are different from other non-profits in terms of the type of staff. The number of staff varies widely, from four people to 30, depending to a great extent on the number of acres cultivated and the extent of the education programs. These numbers include seasonal, year-round, full time and part-time staff. Median staff number is 14. Two organizations have board presidents that are essentially acting as the leaders of the organization.

The relationship between the farmer on a non-profit farm and governance board can be challenging. As one interviewee noted, “The many advantages of farming at a non-profit do not come, however, without some difficulties and responsibilities that an independent farmer might not have to face. Lines of communication with the many different people involved in the organization must remain open and require care and understanding to ensure that they facilitate economically and ecologically sound farming.” As another interviewee put it, “the oversight that a non-profit needs is not necessarily congruent with a farmer mentality.” In an informal conversation as to whether farmers would see the benefits of transforming their farms into non-profits, one non-profit farm staff member noted that many farmers started farms in order to be their own boss, and that non-profit governance structure would not be conducive to that kind of farmer autonomy. Most of the organizations noted that relationships with the board of directors was a challenge. This included the function, autonomy and reliability of the boards and the relationship between staff members/founders and their boards.

During the course of preparing for and conducting these interviews, the term “Friends of” groups came up frequently. This kind of group is most often associated with preserves in the area as opposed to farms. The National Recreation and Park Association states that “‘Friends groups' are generally formed by a group of citizens with common interests in the stewardship of a local park or preserve. Their activities can range from fundraising and volunteer work to significant operational support. At times, friends' groups form on a temporary basis to support development or conservation of a specific park.”7 The presence of Friends of groups is another characteristic that makes non-profit farms in the Hudson Valley more like nature preserves in terms of their governance.

It has long been established that a major challenge of peri-urban agriculture is the price of land. Therefore, the provenance of land for non-profit farms in the Hudson Valley, especially in the high-priced commuter suburbs of the Lower Hudson Valley, are particularly pertinent to the ways in which the business of non-profit farming is conducted in this region. In several cases, farms did not own their own land. Instead, they existed either on land leased from town/city, county or state governments, from non-profit organizations, or from a university. Lease prices tend to be nominal, as the goal of the lending groups is not to make the highest profit (which would be to sell the land for development) but to preserve agriculture in the community. Most of the farm organizations, however, must earn income either from their food sales, their education programs, or from fundraising in order to meet both rents and wages. An informal web survey of several non-profit farms in the United States indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic has severely impacted their programming and therefore their income. In this way, non-profit farms are similar to preserves and other non-profits, in that they depend on education program funding, a strong presence of fundraising boards and fundraising events such as galas, the attraction and cultivation of wealthy donors, and the writing of grant proposals.

Land ownership is also noteworthy in the fact that it affects how the majority of these organizations are run and managed. Because many lease land from government or other organizations, this leads to requirements on how they gain access to the land, whether leased or unleased, the lengths of their leases, what kinds of activities they can pursue or infrastructure they can build, and who has the ultimate say on their programming. Leasing government land also necessitates a partnership that comes with its own benefits and challenges. Nine farms cultivate their own land, and their activities and programming are to some extent determined by how they obtained the land. Many of these other farms were originally family estates and the land was donated by the heirs of these estates. For example, the Verplank family gave Stony Kill Farm to the State of New York for SUNY to use as a teaching farm in the 1940s. Common Ground Farm now leases some of that farmland. Glynwood, Stone Barns, and Stony Kill Farm were all formed from families giving land to preserve the farm and its open space. In the case of Stone Barns and some other non-profit farms derived from estates, these families also provided an endowment which helps to support some of the farm operations.

Organizational budgets vary, from 350K to about 14M. The relative percentages of sources of funding also varied from organization to organization. Some places received most of their funding from contributions, whereas others received most funding via earned income. Some had endowments while others received municipal support. All of the organizations we interviewed shared that funding and fundraising is a constant challenge. This included challenges associated with the dwindling of CSA income; how to bring in more earned income; ways to encourage more individual giving; and the need to “get bigger” in order to have foundations fund their work. Several organizations mentioned aging infrastructure in need of updates, renovations and upkeep, and/or the need for additional infrastructure to support the growth of their programs and initiatives.

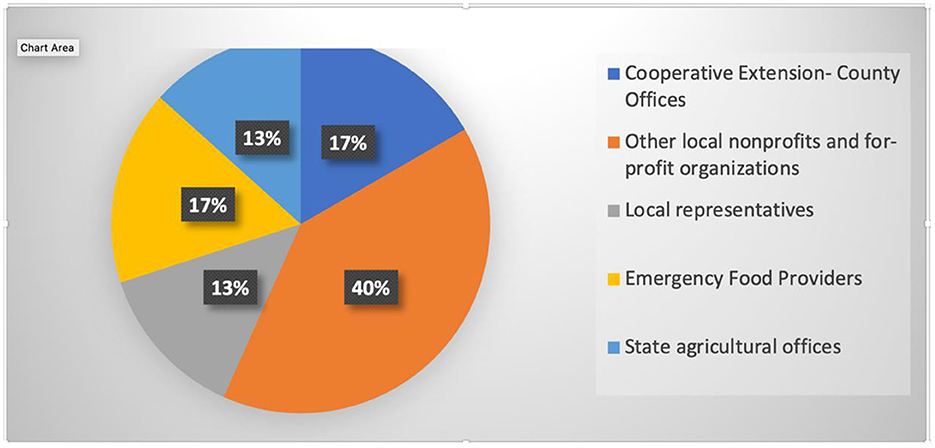

Rather than asking specifically about the role their farm played in the local food system, we asked a general question about the ways in which they collaborated with other organizations in the region. Most of these organizations were involved in collaborations with other local organizations, such as non-profit and government entities (Figure 4). We asked about two types of collaborations in our interviews. The first we termed “partnerships with municipalities,” which include relationships generally structured as a result of land ownership and/or governance. This includes relationships with state, county, town or city municipalities, or relationships with individuals or organizations that own the land which the farm cultivates. The second type was termed “local, state or national collaborations/partnerships,” which sought to understand other kinds of collaborations or relationships these organizations might have that did not necessarily relate to land ownership or governance. The responses in Figure 4 indicate that non-profit farms in the Hudson Valley play a role in local food system infrastructure. However, these organizations went beyond that role, their collaborations having as much to do with their non-profit role as with their agricultural role.

1. Partnership with municipalities/other agencies

Organizations that farm on town/county/state land have an explicit partnership with a governmental organization; this informs at least some part of their decision-making and programming. Three of the eight organizations interviewed have partnerships with county/town municipalities through the fact that the land on which they farm is owned by the county/town/city. Other partnerships include relationships with city council and town governments, chambers of commerce and tourism departments.

2. Collaborations with local, state, and national partners

All eight of the organizations interviewed also collaborate with a number of external state, national, non-profit, and private organizations. Those external organizations include environmental organizations like local watershed agricultural councils and Soil and Water Conservation Districts. Connections also include agricultural organizations such as local agricultural boards, the state agricultural commission and Cornell Cooperative Extension, and farmers markets. Their role as environmental and agricultural educators puts them in contact with school districts and local universities. Finally, their role in food access puts them in touch with food banks and food pantries. As greenspaces in the local landscape, they often have relationships with local tourism organizations and sometimes co-sponsor tourism events. Their relationship with municipalities often puts them in close relationship with local and state officials, who are sometimes involved in governance of the organization.

Figure 4. Collaborations reported by interviewed and observed for web-researched organizations in the Hudson Valley (excluding partnerships/collaborations related to land ownership). Source: Interviews and website analysis.

While farms interviewed mentioned some collaboration with other organizations involved in alternative food networks or sustainable agriculture, it was clear that, for most of these farms, major linkages were with local community organizations and governments. The two largest farms, Stone Barns and Glynwood, were the exceptions, existing as strong members in national and regional networks.

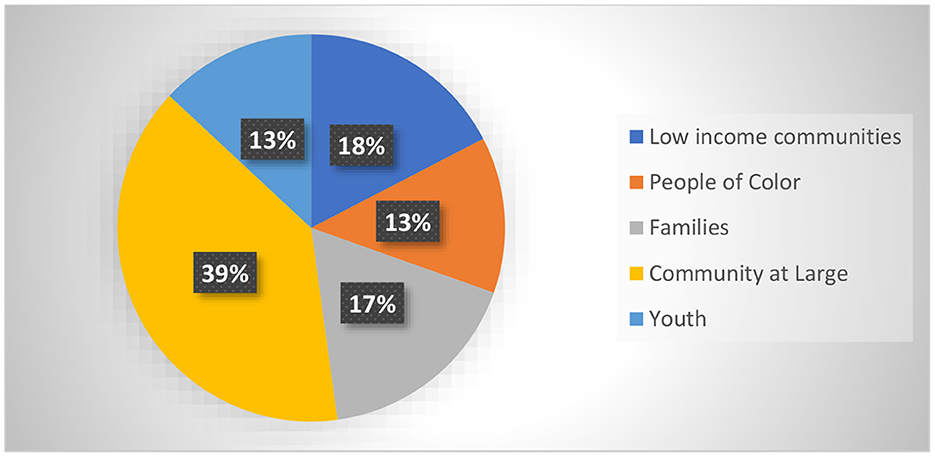

Even for local for-profit farms, the primary audience must be the local community of food consumers who buy their products, since that is their source of their financial support. As a result, many local private farms in the Hudson Valley are part of the “normative landscape” of farming of the region, supporting community, environmental and sustainability missions. Nevertheless, non-profit farms, like most non-profits, are more closely tied to a social mission. Many of the organizations we interviewed expressed a desire to expand their mission even further, to provide access to programming and resources for specific populations in their community, particularly low-income populations and people of color in their region (Figure 5). When asked what audience they would most like to draw to their farm, 6 of the 8 organizations stated that they wanted to work with more people of color and low-income families and individuals. One interviewee stated that “unless we can really reach into black/brown communities and underserved communities, we aren't doing our job, as there's a lot of ignorance and not enough knowledge of what's really going on.”

Figure 5. The most desired audiences for interviewed and web-researched organizations in the Hudson Valley. Source: Interviews and website analysis.

Nearly all of the interviewed organizations listed additional audiences that they would also like to reach, including families with children, food and farming professionals, the general public and “foodies.” At least two of the organizations noted that for the most part, their CSA audience consists of white, middle-class families or individuals. In addition, because Boards of Directors and Friends' Groups are so closely related to philanthropic support, most of the individuals involved in non-profit farm governance are better-off members of the community.

Lastly, three organizations identified families as a key part of their intended audience. In particular, like local nature preserves, many of these farms saw themselves as destinations for families with children. As a result, many farms kept farm animals on the premises, although livestock production was not a major farm goal. The idea, however, was for the most part that these farms served the larger local or regional community, including food and farming professionals, families including low-income families and underserved communities, tried and true foodies, as well as young people. As noted above, the larger farms serve a national or even international alternative agriculture community.

Interviewees, however, admit that the CSA audience has always been mostly white and middle class, and that the ability to link to low income and food insecure families in the Hudson Valley was a challenge. On the other hand, farms near low-income areas were strongly active in food access activity, including providing vegetables to local food banks and other food access organizations. In this way, non-profit farms in the Hudson Valley pursued what they defined as their social justice goals.

However, generally speaking, most of the organizations agreed that they needed more engagement with the communities that they work with (or would like to work with) to determine community needs. This could range from offering scholarships for programs to ensuring they have the right staffing and infrastructure to meet these needs. They also hoped to intensify their collaboration with key players in the community. However, the tensions between a governance structure that relies on the resources provided by better-off donors to meet the needs of less-well-off clients is an issue commonly discussed in the literature on non-profit governance (Salamon, 2002).

We asked interviewees to reflect on their successes in meeting their mission. They tended to have two perspectives on what would be defined as a successful outcome. The first was that some organizations felt they had succeeded in improving the wellbeing of the underserved audiences with which they worked, ranging from improved health outcomes as a result of programming such as school-based programs that lead to a “self-enforcing cycle of benefits [to] kids and increased buy-in from the community,” to large donations of fresh produce to food pantries. These missions reflect the national analysis of non-profit farms which shows that human services are often part of the mission of these organizations. Other notable accomplishments included preserving farmland and coalition building.

We asked interviewees to reflect on whether and how their mission is changing. A few, major themes emerged. These included cost of farmland in the Hudson Valley, climate change, CSA membership changes and the increasing interest and need for the inclusion of diversity and attention to food justice. Other trends that were common were: shifting demographics, a growing trend toward collaboration and the increase of economic disparity, both on a local and international level. One interviewee noted that “there's a problem of scarcity, of rich people having a lot and poor people not. If someone is food insecure, it isn't going to totally help them if you just give them food” (they need housing, etc.). Yet, the nature of fiscal sponsorship and land provenance – dependent on wealthier community members – added to the disconnect between alternative food networks and social justice goals (Guthman, 2008), and their funding sources means that these farms struggle to meet the needs of a diverse audience of wealthy sponsors, middle-income families and low-income community members.

The interviewed organizations shared ways in which they were altering their programming or organizational practices in order to respond to these challenges. Major themes included more collaborations with a wider variety of organizations, more climate resilient or regenerative agricultural practices, inclusion of more diversity on all levels of programming, alternatives to the CSA model and increased assistance to young and emerging farmers.

Despite these challenges, it is clear that non-profit farms play a distinct and useful role in their communities. It is clear that, as a whole, non-profit farms provide valuable resources to the community, enhance sustainability and provide environmental education, regional greenspaces, and watershed protection while also providing critical access to fresh foods. Individually, however, these farms vary widely in terms of their mission. Some grow food primarily to train farmers; others to provide work for those who are unable to gain a living. Still others focus on environmental education or hands-on learning for children. Many grow food to reconnect their communities with the soil or their community's agrarian heritage. A number of farms donate food to food banks, several of them give away everything they grow. Most farms combine a number of these missions in service to their community.

On the other hand, this initial look at non-profit farms indicates that this mode of governance is not without its drawbacks. First, non-profits depend on donations and therefore non-profit missions are heavily influenced by donors, whose interests may outweigh the interests of other stakeholders in local food systems. This is particularly important when major donors are also board members, which is often the case. Since missions are determined by non-profit boards, board members who are also major donors, or founders who set missions while donating large endowments, are likely to have a major influence on farm mission. However, as interviews indicate, non-profit organizations are also keenly aware of the need to serve their local communities and have worked hard to be responsive to local stakeholders (Faulk et al., 2021).

In addition, the extent of to which these farms are playing an active role in local food movements or food policy is not always clear. Many of the best known of these organizations – such as Stone Barns and Glynwood in the Hudson Valley – are leaders in the food policy field. Others appear to be more committed to local philanthropic, service or religious communities, or simply want to connect their communities together to the land and nature. This approach contributes to the conversation about whether or not alternative economies can fill all the social needs not met by private or governmental systems. Recognizing the variety of non-profit farm missions resonates with recent arguments arguing against dividing food organizations according to fixed ideas about alterity (Nemes et al., 2023). These recent analyses seek to go “beyond the impasse,” advocating for an understanding of the hybridity of alternative food network organizations which, simply by their presence, influence food system futures (Misleh, 2022). The recent analysis of the role of local food systems during the COVID 19 food chain breakdowns is an example of the ways that organizations with simple missions to grow local food play an important role in a changing economic and environmental future (Clapp and Moseley, 2020). Looking at these farms from a non-profit mode of governance perspectives adds some depth to these conversations. If “alternative” is a mode of governing based on any of a wide variety of values (Nemes et al., 2023), then non-profit farm governance is the most able to pursue those non-market ideals.

From this broader perspective, one can recognize that many of these farms play a role in their local communities outside of strictly food system issues. For many farms, their social welfare role is closer to traditional charities, such as by supporting those who are not otherwise able to gain an income, or by donating food to food banks. It is therefore difficult to distinguish between non-profit farms' role as farms and their role as non-profits. As non-profits, these farms often perform in ways that are similar to local community non-profits that provide social welfare services. In accordance to these recent, less fixed approaches, one can assess the importance of non-profit farms as hybrid organizations supporting local community, environment, education, social welfare and community development roles, along with providing food. In addition, in their role of supporting communities, non-profit farms have a front row seat to view the problems with the current food system and the communities that system fails to serve.

Further research will be necessary to determine whether an efflorescence of non-profit farms could make a larger contribution to the transformation and re-regionalization of local food systems. Would several non-profit farms in one community end up competing for the limited donation dollars available? Would a farmer want to perform the other jobs necessary to fulfill a social welfare mission, such as community education or food bank donations, in order to fulfill a mission? In a rare essay on his experience managing a non-profit farm, one farmer noted, “Farming for and with others is a complicated and difficult undertaking” (Welton, 2014). And, as noted above, farmers often choose their vocation in order to be their own boss.

What remains clear is that non-profit farms will continue to play a unique and major role in local foodsheds in many communities. They will continue to pursue their hybrid education, human service and environment goals, while growing food for food banks and/or to supplement their income to meet their other missions. There are many questions left to be answered in terms of the who, how and in what ways these farms serve their communities, and whether an expansion of non-profit farms would enhance local food systems. This analysis is a first step toward answering these questions.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

AC: data collection and management. ED and AC: analysis and editing. ED: writing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research was supported by the Helene and Grant Wilson Center for Social Entrepreneurship, the Dyson College Institute for Sustainability and the Environment, and the Kenan Scholarly Research Funds, all at Pace University.

The authors would like to acknowledge the support and assistance of Rebecca Tekula, Director of the Wilson Institute and Marcus Braga, Pace University. In addition, research assistants Julia Corrado and Julie Bazile provided assistance in assembling the database. We also thank the four reviewers for their helpful and extensive comments that contributed to a greatly improved manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/non-profit_organizations#:~:text=A%20non%2Dprofit%20organization%20is,members%2C%20directors%2C%20or%20officers

2. ^The Guidestar list represents organizations that have submitted 990s or 990EZ forms to the IRS. The submission dates vary. We decided to include farms that have submitted 990s and 990EZ forms, and which appear on the Guildstar list, from 2019–2021.

3. ^A few farms do grow and donate food while not receiving income. We have not included those farms (< 5) on this list. However, it is likely that some of these farms receive foundation and other support despite budgets that are zero or negative.

4. ^The Urban Institute data on nonprofit expenses only covers nonprofits over $50,000. It was necessary therefore to only include farms with expenses over $50,000. It was not possible to compare nonprofits vs. nonprofit farms in terms of revenue because The Urban Institute reports these differences in finances only in terms of expenses.

5. ^https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/50-state-food-system-scorecard#bycategory

6. ^This data is not comparable to the general NPF data above, since we asked each NPF to identify all missions, not just their primary one. For that reason, also, the number of missions exceeds the number of farms.

7. ^National Recreation and Park Association. Park Advocate Handbook. Retrieved January 20, 2020 from https://www.nrpa.org/uploadedFiles/Americas_Backyard/park-advocate-handbook-100711.pdf.

Allen, P., FitzSimmons, M., Goodman, M., and Warner, K. (2003). Shifting plates in the agrifood landscape: the tectonics of alternative agrifood initiatives in California. J. Rural Stu. 19, 61–75. doi: 10.1016/S0743-0167(02)00047-5

Allen, P., and Guthman, J. (2006). From “old school” to “farm-to-school”: Neoliberalization from the ground up. Agric. Human Values. 23, 401–415.

Andrée, P., Clark, J. K., Levkoe, C. Z., and Lowitt, K. (2019). Civil Society and Social Movements in Food System Governance. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis.

Boris, E. T., McKeever, B., and Leydier, B. (2017). Roles and Responsibilities of Nonprofit Organizations in a Democracy. The Nature of the Nonprofit Sector. London: Routledge, 15–32.

Clapp, J., and Moseley, W. G. (2020). This food crisis is different: COVID-19 and the fragility of the neoliberal food security order. J. Peasant Stu. 47, 1393–1417. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2020.1823838

De Schutter, O. (2010). Agribusiness and the Right to Food. Report to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food to the Human Rights Council. Available online at: http://www.srfood.org/images/stories/pdf/officialreports/20100305_a-hrc-13-33_agribusiness_en.pdf (accessed March 21, 2023).

Dimitri, C., Oberholtzer, L., and Pressman, A. (2015). The promises of farming in the city: introduction to the urban agriculture themed issue. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 30, 1–2. doi: 10.1017/S174217051400043X

Donald, B., Gertler, M., Gray, M., and Lobao, L. (2010). Re-regionalizing the food system? J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 3, 171–175. doi: 10.1093/cjres/rsq020

DuPuis, E. M., and Gillon, S. (2009). Alternative modes of governance: organic as civic engagement. Agric. Hum. Values 26, 43–56. doi: 10.1007/s10460-008-9180-7

Etzioni, A. (1973). The third sector and domestic missions. Pub. Admin. Rev. 33, 314–323. doi: 10.2307/975110

Faulk, L., Kim, M., Derrick-Mills, T., Boris, E., Tomasko, L., Hakizimana, N., et al. (2021). Nonprofit Trends and Impacts 2021.

Francis, C. (2017). Letters to a Young Farmer: On Food, Farming, and Our Future. Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture. New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press.

Gazley, B. (2016). The nonprofit sector labor force. Pub. Hum. Res. Manage. Prob. Prospects 2, 90–103. doi: 10.4135/9781483395982.n7

Golden, S. (2013). Urban Agriculture Impacts: Social, Health, and Economic: An Annotated Bibliography. Available online at: https://sarep.ucdavis.edu/sites/g/files/dgvnsk5751/files/inline-files/UAAnnotatedBiblio_2013.pdf (accessed March 2, 2023).

Goodman, D., DuPuis, E. M., and Goodman, M. K. (2012). Alternative Food Networks: Knowledge, Practice, and Politics. London: Routledge.

Goodman, D., and Goodman, M. K. (2009). “Food networks, alternative,” in International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, ed. R. Kitchin and N. Thrift (Oxford: Elsevier), 208–220.

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 78, 1360–1380. doi: 10.1086/225469

GuideStar USA (2022). Guidestar: The National Database of Nonprofit Organizations. Williamsburg, VA: GuideStar USAInc.

Guthman, J. (2004). Agrarian Dreams. The Paradox of Organic Farming in California. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Guthman, J. (2008). Bringing good food to others: investigating the subjects of alternative food practice. Cultural Geograph. 15, 431–447. doi: 10.1177/1474474008094315

Hendrickson, M. K. (2015). Resilience in a concentrated and consolidated food system. J Environ Stud Sci 5, 418–431. doi: 10.1007/s13412-015-0292-2

Hendrickson, M. K., and Heffernan, W. D. (2002). Opening spaces through relocalization: locating potential resistance in the weaknesses of the global food system. Sociol. Ruralis 42, 347–369. doi: 10.1111/1467-9523.00221

Hinrichs, C. C. (2000). Embeddedness and local food systems: notes on two types of direct agricultural market. J. Rur. Stu. 16, 295–303. doi: 10.1016/S0743-0167(99)00063-7

Hinrichs, C. C. (2013). Regionalizing food security? Imperatives, intersections and contestations in a post-9/11 world. J. Rural Stu. 29, 7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2012.09.003

Hinrichs, C. C., and Lyson, T. A. (2007). Remaking the North American Food System: Strategies for Sustainability. Sterling, VA: University of Nebraska Press.

Holt Giménez, E., and Shattuck, A. (2011). Food crises, food regimes and food movements: rumblings of reform or tides of transformation? J. Peasant Stu. 38, 109–144. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2010.538578

Hospes, O., and Brons, A. (2016). Food system governance: a systematic literature review. Food Syst. Gov. 13–42. doi: 10.4324/9781315674957-2

Jarosz, L. (2008). The city in the country: Growing alternative food networks in metropolitan areas. J. Rur. Stu. 24, 231–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2007.10.002

Lyson, T. (2004). Civic Agriculture: Reconnecting Farm, Food and Community. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Magdoff, F., Foster, J. B., and Buttel, F. H. (2000). Hungry for Profit: The Agribusiness Threat to Farmers, Food and the Environment. New York, NY: Monthly Review Press.

McCarthy, J., and Prudham, S. (2004). Neoliberal nature and the nature of neoliberalism. Geoforum 35, 275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2003.07.003

Misleh, D. (2022). Moving beyond the impasse in geographies of ‘alternative'food networks. Prog. Hum. Geograph. 46, 1028–1046. doi: 10.1177/03091325221095835

Moragues-Faus, A., Marsden, T., Adlerová, B., and Hausmanová, T. (2020). Building diverse, distributive, and territorialized agrifood economies to deliver sustainability and food security. Econ. Geograph. 96, 1–25. doi: 10.1080/00130095.2020.1749047

National Center for Charitable Statistics (2020). The Nonprofit Sector in Brief 2019. Available online at: https://nccs.urban.org/publication/nonprofit-sector-brief-2019#the-nonprofit-sector-in-brief-2019

National Council of Nonprofits (2019). Nonprofit Impact Matters: How America's Charitable Nonprofits Strengthen Communities and Improve Lives. Washington, DC: National Council of Nonprofits. Available online at: https://www.nonprofitimpactmatters.org/ (accessed March 21, 2023).

Nemes, G., Reckinger, R., Lajos, V., and Zollet, S. (2023). Values-based territorial food networks—benefits, challenges and controversies. Sociol. Rural. 63, 3–19. doi: 10.1111/soru.12419

Polanyi, K. (2001). The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Renting, H., Marsden, T. K., and Banks, J. (2003). Understanding alternative food networks: exploring the role of short food supply chains in rural development. Environ. Plann. 35, 393–411. doi: 10.1068/a3510

Renz, D. O., Brown, W. A., and Andersson, F. O. (2022). The evolution of nonprofit governance research: reflections, insights, and next steps. Nonprofit Vol. Sector Q. 30, 8997640221111011. doi: 10.1177/08997640221111011

Richman, N. J., Allison, P. H., and Leighton, H. R. (2019). Farm to Institution New England: Mobilizing the Power of a Region's Institutions to Transform a Region's Food System. Institutions as Conscious Food Consumers. New York, NY: Academic Press, 175–94.

Rogus, S., and Dimitri, C. (2015). Agriculture in urban and peri-urban areas in the United States: highlights from the census of agriculture. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 30, 64–78. doi: 10.1017/S1742170514000040

Rosol, M. (2020). On the significance of alternative economic practices: Reconceptualizing alterity in alternative food networks. Econ. Geography 96, 52–76. doi: 10.1080/00130095.2019.1701430

Sussman, L., and Bassarab, K. (2017). Food Policy Council Report 2016. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University.

Watts, D. C., Ilbery, B., and Maye, D. (2017). Making reconnections in agro-food geography: alternative systems of food provision. The Rural 29, 165–184. doi: 10.4324/9781315237213-9

Welton, J. (2014). Growing for No Profit. Cornell Small Farms Center. Available online at: https://smallfarms.cornell.edu/2014/04/growing-for-no-profit/ (accessed June 9 2020).

Keywords: non-profit farms, alternative food networks, community food systems, local food infrastructure, non-profits mission, non-profit governance

Citation: DuPuis EM and Christian A (2023) Growing food, growing food systems: The role of non-profit farms. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7:1090682. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2023.1090682

Received: 05 November 2022; Accepted: 15 March 2023;

Published: 17 April 2023.

Edited by:

Laura Zanotti, Virginia Tech, United StatesReviewed by:

Viswanathan Pozhamkandath Karthiayani, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Amritapuri Campus, IndiaCopyright © 2023 DuPuis and Christian. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: E. Melanie DuPuis, ZWR1cHVpc0BwYWNlLmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.