94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

POLICY AND PRACTICE REVIEWS article

Front. Sustain. Food Syst., 25 May 2023

Sec. Nutrition and Sustainable Diets

Volume 7 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2023.1088216

This article is part of the Research TopicNew Challenges and Future Perspectives in Nutrition and Sustainable Diets in AfricaView all 16 articles

Sub-Saharan Africa is experiencing the coexistence of overnutrition, undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies. Comprehensive programs and coherent public policies are required to address this problem. A study of food and nutrition security policies, strategies and programs in Ghana, Kenya and South Africa was conducted between February and July 2022 through desk reviews and key informant interviews. The aim was to generate evidence on the extent to which the policies, strategies and programs were nutrition-sensitive and add value to the scaling up of nutrition and food security. The assessment of the documents was based on the four dimensions of food security, and the Food and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations guidelines on nutrition-sensitive agriculture. A total of 48 policies, strategies and programs were reviewed. To ensure food availability, most reviewed documents tend to focus on food production and income generation, with limited attention on production and supply of diverse and nutrient-dense foods. Access to inputs, credit and land is targeted at smallholder farmers, without little sensitivity to women and youth engagement. Food access is promoted through improved market access by upgrading infrastructure and promoting social safety nets for vulnerable populations. However, information systems for agricultural marketing as well as labor- and time-saving technologies are lacking. Although nutrition education is widely promoted, especially for mothers and children, there is a gap in addressing the nutrition needs of adolescent girls. Regarding food stability, inadequate funding, poor leadership and governance and inadequate monitoring and evaluation systems are the main barriers to successful implementation of policies, strategies and programs. While efforts have been made to promote nutrition-sensitive options in the agriculture and food system value chains, the study identified several gaps that need to be addressed to ensure adequate food and nutrition security.

Food security refers to secure access to sufficient amounts of safe and nutritious food for normal growth and development and an active and healthy life (FAO, 2022a). The four main dimensions of food security are availability, accessibility, utilization, and stability [Committee on World Food Security (CFS), 2014]. Other dimensions of food security include agency, sustainability [High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE), 2020] and governance (Chen et al., 2021).

According to the State of Food Security and Nutrition (SOFI) 2022 Report, 2.37 billion people experienced food insecurity (moderate or severe) in 2021, with Africa experiencing the highest increase compared to other regions (FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO, 2022). The report indicates that the rates of food insecurity have been consistently increasing at the global level since 2014 and confirms that the world is not on track to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2.1, Zero Hunger target, by 2030 (FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO, 2022). It is noteworthy that women experience a higher burden of food insecurity. Globally, the prevalence of food insecurity among women was 10% higher than in men in 2020, compared to 6% in 2019 (FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO, 2021).

Recent analysis also indicates that the world is not on track to achieve the 2025 Global Nutrition Targets set by the World Health Assembly (WHO, 2018a,b). According to the 2020 Global Nutrition Report, no country is on track to achieve all 10 targets (Global Nutrition Report, 2020). Globally, stunting still affects one in five children, wasting one in fourteen children, and overweight about one in seventeen children under 5 years of age, well above the global nutrition targets. Similarly, the NCD targets are off-track, with adult obesity rates (13%) above the 2025 target, with no country on course to halting the prevalence rate. Notably, Africa was the region experiencing the highest levels of the triple burden of malnutrition (childhood stunting, anaemia in women of reproductive age, and adult overweight/obesity).

Nutrition-specific interventions on their own cannot address the burden of malnutrition (Bhutta et al., 2013). The Global Nutrition Report (2020) highlights the need to focus on maximum impact actions such as equitably mainstreaming nutrition into food and health systems to enable countries to reach their targets. Agriculture has a role to play due to its ability to influence the underlying determinants of nutrition outcomes (Black et al., 2013). Therefore, it is beneficial to get agriculture and health/nutrition to work together.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated food and nutrition insecurity and exposed the dysfunctionality of our food systems. According to a report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the pandemic has disrupted global food systems and threatens people’s access to food via various pathways, including disruptions to food supply chains; loss of income and livelihoods; widening social and gender inequality; increasing food prices in localized contexts; lack of access to fresh food markets; and disruption of social protection programs (FAO and WFP, 2020). These disruptions caused global food prices to rise almost 20% in 2020, affecting the most vulnerable the hardest (FAO and WFP, 2020). The ongoing pandemic has called for better integration of food and health systems to safeguard nutrition and health gains made to date (Committee on World Food Security, 2021).

Food systems encompass the entire range of actors and their interlinked value-adding activities involved in the production, aggregation, processing, distribution, consumption and disposal of food and the outputs of these activities, including socio-economic and environmental outcomes (FAO, 2018a,b). These components, viewed through a human rights lens, encompass the food systems framework which is essential for optimal food and nutrition security policies (High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE), 2020). Food systems in Sub-Sharan Africa (SSA) have evolved over the past decades to provide positive benefits such as off-farm employment opportunities and an increased array of food choices outside of local staples. However, non-desirable consequences, including the wide availability and consumption of ultra-processed nutrient-poor foods, and high levels of food loss and waste, have accompanied evolving food systems.

To ensure Africa’s food systems provide healthy diets and positive nutrition outcomes for the population, food and nutrition security policies, strategies and programs need to be developed and implemented in a way that minimizes negative impacts and maximizes positive contributions, including prioritizing people’s right to food, and bridging socio-economic inequities. Lately, the issue of governance of food systems, which is a critical enabling factor for food and nutrition security, has become topical. As part of governance of food systems, the UN Food Systems Summit [United Nations Food Systems Summit (UNFSS), 2021a,b,c] highlighted that food systems transformation requires bringing together actors from different sectors and institutions to work in a coordinated way that is place-based, with a long-term and multi-generational commitment. Addressing the triple burden of malnutrition requires a food systems approach, with coherent public policies, strategies and programs that address both the supply and demand side of food, as well as the food environment where consumers engage with a food system to make food-related decisions.

Food systems across the continent are very diverse, with unique historical, social, and economic contexts (FAO and WHO, 2019). To ensure that each country delivers on all the dimensions of food security and nutrition, while considering these unique contexts, the FAO and WHO emphasize the need for territorial diets. This territorial approach may provide an avenue for the continent’s policy makers to assess the impact of policies on the different aspects of sustainability (health, environment, culture, economy, society), as well as to assess any trade-offs and ensure policy coherence (FAO and WHO, 2019).

The three countries are at different stages of achieving global nutrition targets. Whereas Kenya is on track to achieve four of the global nutrition targets (childhood stunting, childhood wasting, childhood overweight and exclusive breastfeeding), Ghana is on course to achieve one (childhood stunting), while South Africa is on track to achieve two targets (childhood overweight and childhood wasting) (Global Nutrition Report, 2022).

All the three countries are making efforts to ensure functional food systems that contribute to attainment of the global nutrition targets. In common with many other countries, the three countries provided pathways to transformed and sustainable food systems as part of their commitments to the United Nations Food Systems Summit [United Nations Food Systems Summit (UNFSS), 2021a,b,c]. The three countries also convened and made declarations on urban food systems by creating enabling policy and local governance systems within urban areas (FAO, 2020). The UNFSS has proposed five action tracks to achieve sustainable food systems: (i) ensure access to safe and nutritious food for all; (ii) shift to sustainable consumption patterns; (iii) boost nature-positive production; (iv) advance equitable livelihoods; and (v) build resilience to vulnerabilities, shocks and stress [United Nations Food Systems Summit (UNFSS), 2021a,b,c]. To be implemented, these commitments and pathways will need to be adopted as official policy in each country.

This paper describes a study on food and nutrition security policies, strategies and programs in Ghana, Kenya and South Africa. These countries were chosen as case studies in the three Sub-regions of Eastern, Southern and Western Africa. The purpose of the study was to assess the extent to which the policies, strategies and government programs are nutrition-sensitive, equitable, and add value to the scaling up of food security and nutrition in the three countries, and how this can provide lessons for other African countries. Examining these policies at the national level is in line with the recommendation that transformation of food systems should be in accordance with and dependent on national contexts and capacities (Committee on World Food Security, 2021).

The study was conducted in Ghana, Kenya and South Africa between February and July 2022.

The objectives of the study were to address the following key issues:

i. The specific nature and range of policies and related strategies and programs to improve nutrition through food and agriculture, with a lens on women and youth;

ii. Key knowledge gaps in the relationship between food and agricultural systems and nutrition;

iii. Specific aspects of the agriculture and food system and its potential impact on nutrition, including the following study components:

a. Identify and describe policies in agriculture that may have an impact on diet and nutrition, focusing on nutrients of concern, e.g., iron, zinc and vitamin A;

b. Identify applied language and terminology regarding food and nutrition security with a women and youth lens; and

c. Identify information and knowledge needs and gaps that should be addressed through further study and suggest potential processes for monitoring and evaluation.

This study received ethical approval from the Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences Research Ethics Committee, University of Pretoria (Reference No: NAS 101/2022).

A desk review was conducted first, starting in February to May 2022, followed by key informant interviews during the period June to July 2022. To identify current national policies, strategies and programs, searches were conducted on websites of government departments working in the food and nutrition sectors and the FAOLEX database (FAO, 2022b). The programs were limited to those at national level and led by government ministries or departments. Representatives from government departments were contacted to verify that the policies identified were in use and to provide guidance on additional policies that might have been missed from the online searches. A total of 48 documents, comprising 15 from Ghana, 20 from Kenya and 13 from South Africa, were reviewed (see Table 1 for list of documents).

The policies were analyzed using a checklist adapted from the FAO (2015) guiding principles for nutrition-sensitive agriculture, the four dimensions of food security [Committee on World Food Security (CFS), 2014], and additional criteria on agency/governance and sustainability. The checklist was used to assess the extent to which the policies, strategies and programs were nutrition-sensitive and can add value to key actions on the scaling up of nutrition and food security. Further, these documents were reviewed for the extent to which they create opportunities for women and youth. The checklist and key informant interview guides are attached as Supplementary information 1.

Key informant interviews were conducted with relevant stakeholders working in the food and nutrition sector, including representatives of relevant government departments and ministries, civil society organizations and development partners. The purpose of the key informant interviews was to triangulate the information gathered during the desk reviews and to get an in-depth understanding on the status of implementation of the policies, strategies and programs. The targeted stakeholders were purposively selected and included the following: (i) Government ministries and departments (e.g., Ministries of Health, Food and Agriculture, Women in Agriculture, Food and Drug Authorities, Social Development, and Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation); (ii) UN agencies (WFP, UNICEF); and (iii) other organizations (research institutions and farmer organizations). A total of five key informants in each country were interviewed Ghana and Kenya and eight in South Africa.

Relevant institutions were engaged via telephone, emails and virtual conference calls to explain the purpose of the study and request the participation of their representatives as key informants. Following the engagements, the heads of departments nominated their representatives to participate as key informants. The interviews were conducted in English through in-person interviews or remotely via internet-based platforms. An interview guide (see Supplementary information 2) containing open ended questions was used. The interview guide covered issues related to agriculture and nutrition policy formulation and implementation, organizational roles, collaboration, technical capacities, identified gaps, and factors that either enhance or hinder these issues. The duration of the interviews varied between 1 h 30 min and 3 h. The discussions were captured through writing notes as well as recording (based on consent from the participants).

The policies were analyzed based on the criteria in the checklist. Depending on the level of coverage of each criterion from the checklist in each of the policies, strategies and programs, these were placed in one of three categories as being (i) covered; (ii) partly covered; or not covered. For the key informant interviews, key themes were extracted using a deductive analytical approach and incorporated into the report.

Ghana is a lower middle-income country with an estimated population of 30.8 million and a gross domestic product (GDP) (purchasing power parity) of $164.8 billion (Ghana Statistical Service, 2021). Some key challenges facing Ghana’s food systems include poor dietary choices, increasing urban food insecurity, non-mechanized agriculture, inadequate funding, high levels of environmental degradation, unpredictability of food supply and prices due to climate variability, and limited institutional and human resource capacity (Cooke et al., 2016). Ghana, in common with other African countries, is grappling with the triple burden of malnutrition. An estimated 17.5% of children under 5 years of age are affected by stunting, 6.8% are wasted, and 1.4% are overweight (Global Nutrition Report, 2020).

Kenya’s food system combines traditional and modern dynamics. Traditional elements are associated with widespread extreme poverty and undernourishment, and this is more dominant than the modern dynamic (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, 2022). In the drought-prone areas of the Arid and Semi-Arid Lands (ASALs), which make up 80% of the country’s land area, there have been increased vulnerabilities, which have resulted in chronic emergency needs, driven by food insecurity and high rates of acute malnutrition. Additionally, urbanization and rapid population growth, a large and youthful workforce, and technological advances, are also changing the demands and opportunities for food systems. The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has led to increased levels of food shortage. In 2020, about 26.2% of children under 5 years of age were stunted, while 4% were wasted and 4.1% overweight (Global Nutrition Report, 2020).

South Africa has a population of about 61 million people and is classified as a middle-income country. It is food secure at the national level, yet there are high levels of food insecurity at community and household levels. Approximately 3.4% of children under 5 years of age are wasted, while 21.4% are stunted [Southern African Development Community (SADC), 2021]. Concurrently, overweight and obesity are increasing rapidly, and South Africa is not on track to achieve SDG 2 targets (Global Nutrition Report, 2020). Approximately 18.2% of men and 42.9% of women are obese, while 16.3% of girls and 13.5% of boys aged 5–19 years are classified as obese (Global Nutrition Report, 2020). Due to an increase in population and urbanization, there are high levels of food insecurity in rural areas and urban informal settlements.

Food availability is achieved when there is adequate physical existence of food at national and household levels. This is a function of food production, supply and distribution. The policies, strategies and programs were assessed against four priority areas and corresponding key elements and a cross-cutting priority area of women and youth (Table 2; Priority areas and key elements of the availability dimension).

Overall, 37–73% (18–35 out of 48) of the policies, strategies and programs in Ghana, Kenya and South Africa address the priority areas and key elements related to food availability, while 12–26% (6–13 out of 48 documents) partly cover the same issues (Table 2). Great efforts and emphasis are focused on the provision of factors of production in the form of land, credit, seeds and other inputs to rural smallholder farmers in general, with little or no special attention being paid to urban and peri-urban production and women, youth and other vulnerable groups, inspite of the recent urban food systems dialogues in the three countries (FAO, ICLEI, 2022). A recent policy on Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries Policy for Nairobi City County (2015) in Kenya is an exception. As a result of urbanization, food insecurity in urban and peri-urban areas is high.

Fresh fruits, vegetables and animal source foods are inaccessible to the rural, urban and peri-urban poor due to high food prices [High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE), 2017]. It is, therefore, necessary to promote traditional foods such as legumes, local fruits and vegetables as well as forest foods to improve dietary diversity and improve nutrition [Cernansky, 2015; High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE), 2017]. Nutrient-dense crops such as vegetables and fruits are promoted by almost all the reviewed documents across the three countries. However, there is little attention to use of biofortified seed and traditional or indigenous crops. These areas should be strengthened, possibly by providing incentives to producers. Production of protein-rich foods such as legumes and small livestock is not adequately promoted in policies, strategies and programs.

Only 35–54% (17–26 out of 48) of the policies, strategies and programs promote access to productive resources among women in Ghana, Kenya and South Africa (Table 2). The lack of targeted efforts to empower women in food production is a missed opportunity, considering that nearly half of the agricultural workforce globally are women (FAO, 2018a). In addition, women’s control of productive resources has been associated with improved nutrition for household members (Quisumbing, 2003; FAO, 2015; Hodge et al., 2015).

Most of the Ghanaian policies and related documents (86.7%;13 out of 15) cover the priorities and key elements to maintain and improve the natural resources such as water, soil and climate change, compared to Kenya (15%; 3 out of 20) and South Africa (38.5%; 5 out of 13). Some of the practices promoted in the reviewed policies include climate resistant crops, organic farming and preservation of land meant for agriculture. However, more needs to be done by the three countries to be proactive to address climate change adaptation and mitigation. Globally, climate change is a problem which is characterized by shifting seasons and increased episodes of natural disasters such as floods and droughts.

Improved food processing, storage and preservation are covered by 40–87% (19–42 out of 48) of the policies, strategies and programs. Food processing, storage and preservation are important in preventing post-harvest losses, preserving nutrient content of food, adding value to crops and increasing income, preventing seasonal shortages of micronutrient-rich foods and improving food safety (FAO, 2015). Food safety is covered by 23–67% (11–32 out of 48) of the reviewed documents. These results are indicative of a major gap in food safety and actions to address aflatoxin poisoning are almost non-existent.

Aflatoxin poisoning leads to suppressed immunity, liver cancer in humans and stunting in children (WHO, 2018a,b). This calls for an urgent need for all country policies to improve on documentation of food safety measures. Further, issues on post-harvest losses and food waste (DEFF and CSIR, 2021) are not adequately addressed in most reviewed documents. These findings are consistent with a policy review study that was conducted in Senegal (Lachat et al., 2015).

Women- and youth-related issues were addressed in 35–54% (17–26 out of 48) of the framework documents, showing a major gap when it comes to women and youth empowerment. Where framework documents partly cover women and youth, the focus is mainly on women rather than youth in food production and availability value chains.

Food access is achieved when all households have enough resources and are physically able to obtain food in sufficient quantities, of good quality and diversity, for a nutritious diet. The policies and related strategies and programs were assessed against three priority areas and corresponding key elements, including women and youth (Table 3; Priority areas and key elements of the access dimension).

At least half (24 out of 48) of the reviewed documents promote the expansion of markets and consumer access to markets (Table 3). Market access in all the three countries focuses on developing infrastructure and creating markets, although this varies across the different documents. Improved access to markets has positive effects on food access, including increasing income for farmers, incentivizing food production by farmers and improving dietary diversity among consumers (FAO, 2013).

An analysis of data from Ethiopia, Indonesia, Kenya and Malawi showed that farmers’ market access had a greater effect on dietary diversity compared to production of diversified foods (Sibhatu et al., 2015). Further, children in Ethiopia living closer to markets had more diverse diets and higher mean weight for height (WHZ) and weight for age (WAZ) z-scores (Abay and Hirvonen, 2016). Some of the efforts outlined in the reviewed documents to create markets for smallholders include linkages with school feeding programs and facilitating bulk government purchases from smallholders. However, issues of trade and how it affects the smooth functioning of markets are not addressed comprehensively.

All three countries are battling overweight and obesity among their populations. Efforts have been made to impose tax on unhealthy foods such as sugar sweetened beverages. Nevertheless, there is a huge gap at policy level in advocating for tax on ultra-processed foods high in sugar, salt and fats, whilst lowering taxes on healthy foods such as vegetables and fruits. This is a barrier to promoting consumption of nutritious foods, considering that food prices affect consumers’ food choices (Griffith et al., 2015).

The three countries are faced with a challenge of high consumption of ultra-processed foods and low consumption of nutritious foods. Highly processed energy-foods are more affordable compared to nutrient-dense foods (Drewnowski and Specter, 2004). In common with findings of a study in Senegal (Lachat et al., 2015), marketing of nutritious foods is quite low in all three countries. Women empowerment through income opportunities is partly addressed but there is limited priority regarding decision making roles, labor and time-saving technologies for women. A study in East Africa proposed focusing on export production to reduce the time burden on women (Hodge et al., 2015).

Regrettably, a huge gap still exists regarding youth as they continue to experience high unemployment rates. Various social safety nets for vulnerable groups are well documented in policy and related documents, including food and cash support. School feeding programs are well supported by policies in all three countries to increase access to food among vulnerable school children. In addition, school feeding programs create a market for smallholders to sell their produce and earn income [High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE), 2017]. In general, the policies, strategies and programs in all three countries are limited in promoting the development of agricultural market information systems, including use of information and communication technologies (ICT).

Food utilization refers to digestion and assimilation of the nutrients from the food consumed, which in turn is influenced by health status, preparation of food, water and sanitation conditions, and the microbiological and chemical safety of the food. In addition, utilization is influenced by nutritional knowledge (Baute et al., 2018), food habits, child-feeding practices, and the social role of food in the family and in the community. The priority areas and the corresponding key elements are shown in Table 4 (Priority areas and key elements of the utilization dimension).

Most reviewed policies, strategies and programs promote knowledge-based nutrition interventions, including nutrition education and, sometimes, behavior change in communities, schools and health care settings. Between 40 and 73% (19 and 35 out of 48) of the reviewed documents adequately cover food utilization in Ghana, Kenya and South Africa (Table 4). Interventions on reducing all forms of malnutrition across different age groups and populations are prioritized. However, inclusion of adolescent nutrition and the roles of men in ensuring good nutrition for women and children are not well covered. Adolescents are mostly targeted through school nutrition in all three countries, leaving those that may not be enrolled in schools. An example of a good practice is the promotion of anemia screening for girls in schools in South Africa.

All three countries have policies that adequately promote exclusive breastfeeding and complementary feeding. Dietary diversity is also promoted but the link between a diverse diet and prevention of malnutrition, including micronutrient deficiencies, is not spelt out in some of the documents. Instead, when it comes to micronutrient deficiencies, supplementation with vitamins (such as Vitamin A, iron, zinc and folate), rather than consuming diets rich in those nutrients, is mostly emphasized. Although water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) were mentioned in some of the policies, they were not included in the monitoring frameworks.

Food stability is attained when the supply of and access to nutritious food at national and household levels remains constant during the year and in the long-term, even in the face of economic and climate shocks or cyclical events such as seasonal changes. Stability is felt through the availability and access dimensions. Sustainability refers to long-term viability of the ecological and social bases of food systems (FAO, 2018b; Clapp et al., 2022). Stability and sustainability are also determined by the governance of food systems.

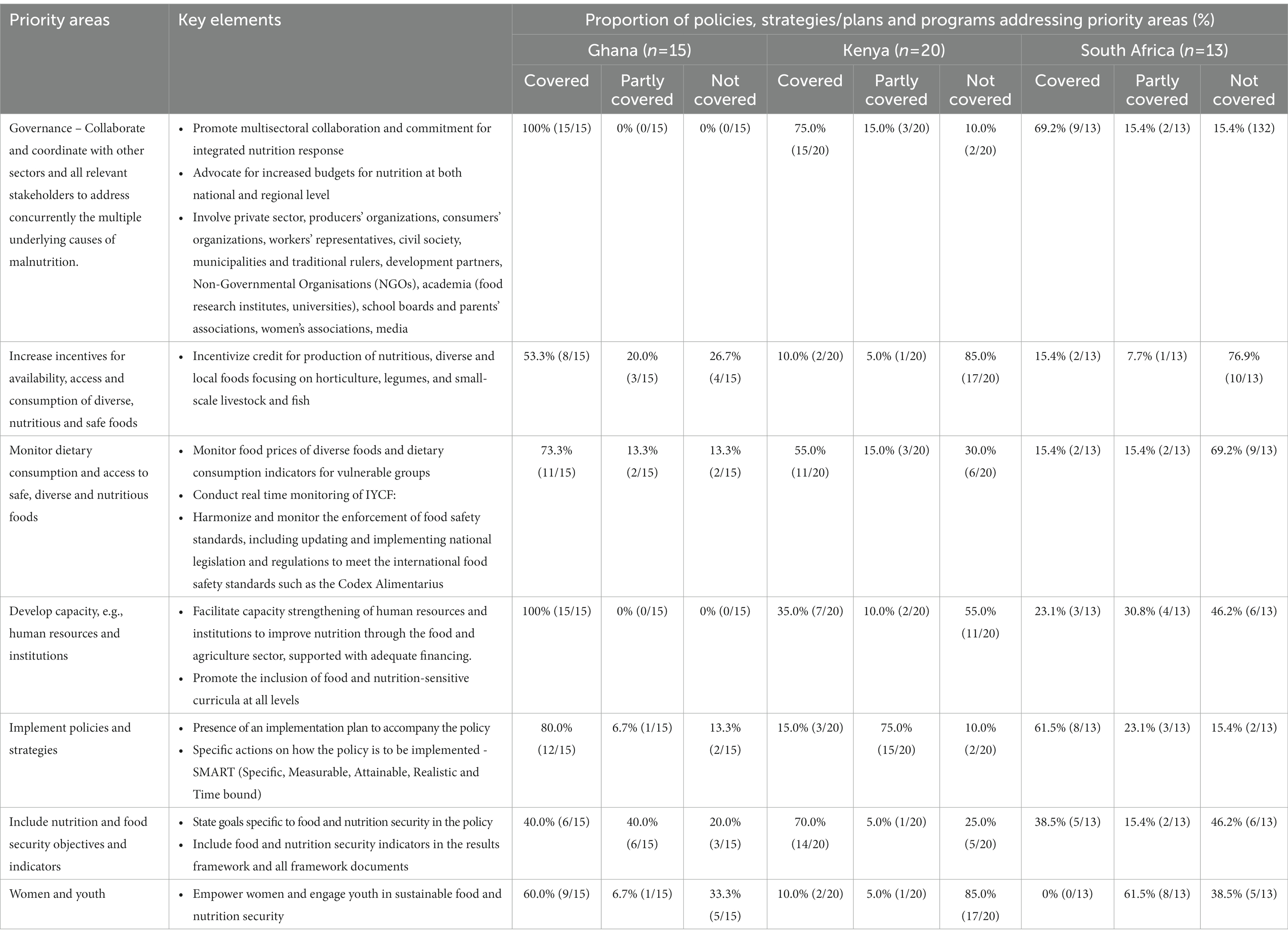

Governance relates to the rules of the game, that is, how the rules, norms and actions are structured, sustained, regulated and implemented through the interaction of different actors, such as government institutions, civil society, the private sector and consumers (Chen et al., 2021). Agency, the capacity of individuals to exercise voice and make decisions about their food systems, is an important component of governance (Clapp et al., 2022). Good governance of food systems facilitates equitable, coherent, coordinated, and transparent design and review of mechanisms and processes such as policies, legislation, planning, finances, monitoring and coordinated implementation (GAIN, 2021). The priority areas and their corresponding key elements that were assessed are shown in Table 5 (Priority areas and the key elements of the stability dimension, sustainability and governance).

Table 5. Priority areas and the key elements of the stability dimension, sustainability and governance.

Ensuring food stability and sustainability is complex and often a challenge in many settings. On paper, all three countries have very good collaboration and coordination among sectors to ensure good governance of the food system (see Table 5). However, in practice, there is a preponderance of vertical programming as most sectors prioritize their own mandate rather than integrated food and nutrition systems and interventions. The study has highlighted the need for effective multi-sectoral collaboration and governance, instead of the vertical programming which is often seen in policies and programming.

Although multi-sectoral collaboration and participatory governance is often referred to in the policies, key informant interviews revealed the need to strengthen this, especially at the regional and district levels. It is evident that most sectors prioritize their main goals rather than nutrition goals. For example, the focus of agriculture and food policies is on food production; there is limited focus on production of diverse and nutrient-dense foods. In addition, evidence-based policy development appears to be limited. Some of the reasons found to hinder evidence-based policy development include policy makers’ own interests and attitudes, lack of accountability and lack of time to wait for and examine evidence (Gillespie et al., 2015).

Often, budgetary constraints hinder successful multisectoral approaches. In general, there is limited advocacy for increased nutrition budgets in all three countries. The government is the main funding source for food and nutrition security programming in all three countries. Private sector involvement is mentioned in policies, although their roles in policy processes are usually not fully spelt out. The COVID-19 pandemic has been a major barrier for implementation in all three countries, as highlighted by key informants. It took away resources (especially financial and human resources) from an already strained sector.

Regarding sustainable supply of nutritious food, the greater proportion of policies and related documents lack incentives to promote production of nutritious and diverse foods such as legumes and small livestock. Except for Ghana, less than 50% (7 out of 15) of the policies incentivize the availability, access and consumption of diverse, nutritious and safe foods.

Strong leadership and participatory governance are critical to ensure the successful implementation of interventions and sustainable food and nutrition security. The reviewed policies and related documents demonstrate the need for very well-organized systems of governance and accountability. However, some gaps are evident, for example, policies are fully embraced at national level but not at provincial and district levels. Nutrition indicators (mainly impact level) are partly included in at least half of the documents reviewed per country. However, most indicators do not capture women and youth issues. The lack of an integrated monitoring system for food and nutrition security also hinders collaboration and accountability among various sectors and actors. Additionally, the lack of women empowerment and youth indicators in most policy action plans and M&E frameworks, poses a significant challenge for monitoring progress of inclusivity objectives [International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), 2012].

As part of the United Nations Food Systems Summit (UNFSS) (2021a,b,c), youth committed to action, advocacy, and empowerment to transform food systems. This would be achieved by raising awareness for healthy, nutritious, and sustainable diets; supporting, advocating and acting on climate and biodiversity actions for a liveable resilient future; and advocating for fair and decent wages and social protection for people working in food systems. These commitments will need to be incorporated into national food systems policies and strategies.

Vulnerable populations, for example, the elderly and disabled, are also inadequately targeted in food and nutrition security policies, strategies and programming. Implementation of policy action plans and strategies suffers from non-robust monitoring and evaluation (M&E) mechanisms. Lack of resources – staff, technical capacity, funding, and equipment – are cited by key informants as issues impeding effective implementation and monitoring of food and nutrition security action plans.

Technical capacity building, which this study has helped to surface, is needed to ensure policy and program objectives are achieved. These observations are similar to those from a policy review in Senegal where some gaps in agricultural programs included lack of nutrition goals in program implementation as well as inadequate monitoring of nutrition indicators (Lachat et al., 2015). In general, there is insufficient involvement and the voice of consumers in the governance of the food systems, while participation by smallholder farmers is largely limited to compliance with regulations, either from government or marketing channels.

A number of lessons that would be of value to other African countries were identified from the three country case studies. These are listed as follows:

i. Protection of land for agricultural use through levying taxes on land changed from agricultural to other uses, while using the taxes to fund agricultural development programs;

ii. Acceptance and formalization of urban and peri-urban agriculture and providing the necessary support as a way of addressing food and nutrition insecurity in urban areas;

iii. The need to promote traditional and orphan/neglected crops, some of which are known to be highly nutritious and have the ability to withstand adverse conditions brought about by climate change;

iv. Expansion of food storage facilities and strategic grain reserves to strategic food reserves, covering traditional cereal and/or staple foods, to include other nutritious foods such as pulses, fruits and vegetables;

v. Facilitate access of women to traditionally male-dominated commodity chains by providing financial and capacity development;

vi. Support increased participation of women and youth in agriculture and food system value chains as employees and agripreneurs, especially by creating dedicated funding mechanisms and capacity development;

vii. Sensitize and develop the capacity of agricultural extension services in nutrition-sensitive agriculture;

viii. Nutrition education and behavior change communication programs to improve food and nutrition security to include men as they influence most food and dietary choices at household level;

ix. To achieve effective multi-sectoral coordination of national food and nutrition security programs, it is necessary to set up one national leadership and coordination structure at the highest level, for example the office of the presidency or prime minister’s office; and

x. Countries need to promote private sector investment in smallholder agriculture and food system value chains by making smart public sector investments through innovative fiscal and economic incentives.

The study assessed the nutrition-sensitivity of food and nutrition security policies, strategies and programs in Ghana, Kenya and South Africa. The intended objectives of assessing key gaps in policy and programming relating to the four pillars of food security (availability of safe and nutritious food, access, utilization, and stability, including sustainability and governance) have been adequately analyzed in this report. The report has highlighted the need for effective multi-sectoral collaboration and governance, instead of the vertical programming which is often seen in policies and programming. Although multi-sectoral collaboration and participatory governance is often referred to in the policies, there is still a need to strengthen this, especially at the regional and district levels.

Implementation of policy action plans and strategies suffers from non-robust M and E mechanisms. Lack of resources – staff, technical capacity, funding, and equipment – are all cited as issues impeding effective implementation and monitoring of food and nutrition security action plans. Technical capacity building, which this report has helped to surface, is needed to ensure policy and program objectives are achieved. Some focus areas of women empowerment which have not achieved adequate progress include access to credit and decision-making roles for women in agriculture.

Focus on women and youth issues is mentioned in most policies but has not been adequately achieved. The lack of women and youth indicators in most policy action plans, and M and E frameworks poses a significant challenge for monitoring progress of inclusivity objectives. Vulnerable populations, for example, the elderly and disabled, are also inadequately targeted for food and nutrition security policies and programming.

Whilst efforts have been made to make policies nutrition-sensitive, the following gaps have been noted:

i. Food production and income generation are the main priorities of food policies, with limited attention on production and supply of diverse and nutrient-dense foods.

ii. Allocation of farming resources are not women- or youth-sensitive.

iii. Information systems for agricultural marketing as well as labor- and time-saving technologies are lacking.

iv. There is lack of male involvement in ensuring adequate nutrition for mothers and children. In addition, nutrition-specific interventions do not address adolescent girl’s needs.

v. Inadequate funding, poor leadership and governance and inadequate monitoring and evaluation systems hinder successful implementation of policies, strategies and programs, even when they are nutrition-sensitive.

The findings were used for capacity building of mid-level policy makers during planned virtual national and regional roundtables. The meetings highlighted the gaps that exist and provided awareness to policy makers to discuss actions aimed at developing measures to improve future food and nutrition policies and their implementation.

There is a need to conduct research on sustainable funding mechanisms and identify successful cases of how governments and their partners should sustainably fund nutrition programs. It is critical that all three countries research and implement evidence-based interventions, whilst identifying a basic set of indicators which measure the impact of agriculture on nutrition and ensure efficient use of resources. Efforts should be made to investigate the most effective incentives to improve nutrition outcomes and how to create functional public-private partnership arrangements. It is also necessary to conduct research on how to empower women and youth for more meaningful participation in food and agriculture value chains.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (Grant number ES/T003871/1) under the ARUA-GCRF UKRI Partnership Program as part of the Capacity Building in Food Security (CaBFoodS-Africa) project.

We would like to acknowledge the active participation of the food and nutrition security stakeholders in Ghana, Kenya and South Africa who freely shared information to enrich the study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2023.1088216/full#supplementary-material

Abay, K., and Hirvonen, K. (2016). Does market access mitigate the impact of seasonality on child growth? Panel data evidence from Northern Ethiopia (No. WP-2016-05), Innocenti Working Paper.

Baute, V., Sampath-Kumar, R., Nelson, S., and Basil, B. (2018). Nutrition Education for the Health-care Provider Improves Patient Outcomes. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 7:2164956118795995. doi: 10.1177/2164956118795995

Bhutta, Z. A., Das, J. K., Rizvi, A., Gaffey, M. F., Walker, N., Horton, S., et al. (2013). Lancet Nutrition Interventions Review Group, the Maternal and Child Nutrition Study Group, 2013. Evidence-based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: what can be done and at what cost? Lancet 382, 452–477. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62093-0

Black, R. E., Victora, C. G., Walker, S. P., Bhutta, Z. A., Christian, P., de Onis, M., et al. (2013). Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 382, 427–451. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X

Cernansky, R. (2015). The rise of Africa's super vegetables. Nature 522, 146–148. doi: 10.1038/522146a

Chen, Q., Knickel, K., Tesfai, M., Sumelius, J., Turinawe, A., Isoto, R., et al. (2021). A framework for assessing food system governance in six urban and peri-urban regions in Sub-Saharan Africa. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5:763352. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2021.763352

Clapp, J., Moseley, W. G., Burlingame, B., and Termine, P. (2022). Viewpoint: The case for a six-dimensional food security framework. Food Policy 106:102164. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2021.102164

Committee on World Food Security, (2021). CFS voluntary guidelines on food systems and nutrition. Rome: CFS

Committee on World Food Security (CFS) (2014). Global Strategic Framework for Food Security & Nutrition (GSF). Third Version 2014. Rome: CFS.

Cooke, E., Hahue, S., and Mckay, A., (2016). The Ghana poverty and inequality report: using the 6th Ghana living standards survey. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/ghana/Ghana_Poverty_and_Inequality_Analysis_FINAL_Match_2016(1).pdf

DEFF and CSIR (2021). Food waste prevention and management: a guideline for South Africa. 1st, DEFF & CSIR, Pretoria.

Drewnowski, A., and Specter, S. E. (2004). Poverty and obesity: the role of energy density and energy costs. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 79, 6–16. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.1.6

FAO (2015). Designing nutrition-sensitive agriculture investments. Checklist and guidance for program formulation. Available at: https://www.fao.org/3/i5107e/i5107e.pdf

FAO (2018b). Sustainable food systems – concept and framework. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/ca2079en/CA2079EN.pdf

FAO (2020). Cities and local governments at the forefront in building inclusive and resilient food systems: key results from the FAO Survey “Urban Food Systems and COVID-19”. Revised Version. Rome: FAO

FAO (2022a). Hunger and food insecurity. Available at: https://www.fao.org/hunger/en/#:~:text=What%20is%20food%20insecurity%3F,of%20resources%20to%20obtain%20food

FAO (2022b). FAOLEX database. Country Profiles. Available at: https://www.fao.org/faolex/country-profiles/en/

FAO and WFP (2020). Impacts of COVID-19 on food security and nutrition: developing effective policy responses to address the hunger and malnutrition pandemic. HLPE issues paper 1–24.

FAO, ICLEI (2022). Sixteen Urban Food Systems Dialogues for the United Nations Food Systems Summit – Synthesis Report. Rome. doi: 10.4060/cc0309en.

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO (2021). The State of Food Security in the World 2021. Transforming food systems for food security, improved nutrition and affordable healthy diets for all. Rome, FAO

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO (2022) The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022. Repurposing food and agricultural policies to make healthy diets more affordable. Available at: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cc0639en.

Ghana Statistical Service (2021). Ghana 2021 Population and Housing Census – Summary of Provisional Results. Accra Ghana Statistical Service

Gillespie, S., van den Bold, M., Hodge, J., van den Bold, M., Hodge, J., and Herforth, A. (2015). Leveraging agriculture for nutrition in South Asia and East Africa: examining the enabling environment through stakeholder perceptions. Food Sec. 7, 463–477. doi: 10.1007/s12571-015-0449-6

Global Nutrition Report (2020). Action on equity to end malnutrition. Bristol, UK: Development Initiatives Poverty Research Ltd.

Global Nutrition Report (2022). Global Nutrition Report: Stronger commitments for greater action. Bristol, UK: Development Initiatives.

Griffith, R., O’Connell, M., and Smith, K. (2015). Relative prices, consumer preferences, and the demand for food. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 31, 116–1430. doi: 10.1093/oxrep/grv004

High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE). (2017). Nutrition and food systems. A report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security. HLPE Rome

High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE) (2020). Food Security and Nutrition: Building a Global Narrative Towards 2030. HLPE Rome

Hodge, J., Herforth, A., Gillespie, S., Beyero, M., Wagah, M., and Semakula, R. (2015). Is there an enabling environment for nutrition-sensitive agriculture in East Africa? Stakeholder perspectives from Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda. Food Nutr. Bull. 36, 503–519. doi: 10.1177/0379572115611289

International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) (2012). Gender equality and women’s empowerment. IFAD and gender. Available at: http://www.ifad.org/gender/.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (2022). Kenya Demographic and Health Survey. Available at: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/PR143/PR143.pdf

Lachat, C., Nago, E., Ka, A., Vermeylen, H., Fanzo, J., Mahy, L., et al. (2015). Landscape analysis of nutrition-sensitive agriculture policy development in Senegal. Food Nutr. Bull. 36, 154–166. doi: 10.1177/0379572115587273

Nairobi City County (2015). Nairobi City County Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries Policy. Nairobi: KIPPRA

Quisumbing, A. R. (2003). Household decisions, gender, and development. A synthesis of recent research. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

Sibhatu, K. T., Krishna, V. V., and Qaim, M. (2015). Farm production diversity and dietary diversity in developing countries. Available at: http://purl.umn.edu/205286

Southern African Development Community (SADC). (2021). Synthesis report on the state of food and nutrition security and vulnerability in Southern Africa. Gaborone: SADC

United Nations Food Systems Summit (UNFSS) (2021a). Five priority areas for action revealed as part of UN Food Systems Summit engagement process. Available at: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2020/09/five-priority-areas-for-action-revealed-as-part-of-un-food-systems-summit-engagement-process/

United Nations Food Systems Summit (UNFSS) (2021b). Policy Brief|Governance of Food Systems Transformation. Available at: https://ecoagriculture.org/publication/governance-of-food-systems-transformation/

United Nations Food Systems Summit (UNFSS) (2021c). Youth Declaration on Food Systems Transformation. Available at: https://foodsystems.community/youth-declaration-on-food-systems-transformat

WHO (2018a). Food safety digest: aflatoxins. Available at: https://www.who.int/foodsafety/FSDigest_Aflatoxins_EN.pdf

Keywords: nutrition, nutrition-sensitive, policies and programs, sustainable food systems, women and youth empowerment

Citation: Sibanda S, Munjoma-Muchinguri P, Ohene-Agyei P and Murage AW (2023) Policies for optimal nutrition-sensitive options: a study of food and nutrition security policies, strategies and programs in Ghana, Kenya and South Africa. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7:1088216. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2023.1088216

Received: 03 November 2022; Accepted: 25 April 2023;

Published: 25 May 2023.

Edited by:

Hettie Carina Schönfeldt, University of Pretoria, South AfricaCopyright © 2023 Sibanda, Munjoma-Muchinguri, Ohene-Agyei and Murage. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Simbarashe Sibanda, c3NpYmFuZGFAZmFucnBhbi5vcmc=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.