- 1Department of Societal Transition and Agriculture, Institute for Social Sciences in Agriculture, University of Hohenheim, Stuttgart, Germany

- 2Department of Geography, University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany

Departing from reflections and observations raised by Food Policy Councils (FPCs) within North America specifically, this article explores the complex material, discursive, and governance aspects of food provision on the urban-regional scale by highlighting recent accounts of public food provision within state-funded public-catering places in Germany. Based on a fieldwork in Southern Germany, and grounded in a methodological approach guided by participatory action research (PAR), participatory observation, feminist GIS, and 17 interviews with different actors within the regional food systems involved we would like to form the basis for pushing these new approaches further toward more food democracy and food justice as we are elevating the key factors and rewards, but also the downsides and challenges of food provision in public catering places regarding social-ecological inequalities. In doing so, the global intimacies of the urban food system on the local scale, their different modes of inclusions and exclusions, and their intersections of inequalities are unpacked by also shifting the focus to the economic and political entanglements at stake within the global sphere of food provision. By amplifying how producers, meal providers, and consumers within the urban food systems perceive (and perhaps contradict) issues of food justice and by coalescing their perspectives about local food system transformations and desires toward food justice and sustainability, not only the challenges at place but also the promises of hope within public-catering places are illustrated.

1. Introduction

Food is more than solely a lifestyle issue. In the aftermath of Covid-19 and times of inflation (and not only then), there are shortages of delivery rates, there are climate-change-induced agricultural challenges in fostering healthy food, and accessible food is distributed unequally. Even in welfare states such as Germany, a recent study highlights that 3.5 million persons are affected by “material food poverty” which is connected to “social food poverty” that excludes people from participation in social life [WBAE (Scientific advisory board on agricultural policy, food and consumer health protection), 2023, p. 1]. This situation leads to a whole set of subsequent questions: which modes of food production, processing, and distribution can foster a more just access to and sustainable transformation within the current food system? How can we pay better attention to the underlying inequalities and problematizations, when food is produced, processed, and consumed within the structure of global capitalism? And how can consumers gain more decision-making power over the food system? These questions are raised by food democracy and food justice theorists and by the rising FPC movement. Departing from these reflections and observations, this article explores the concept of food justice and its interlinkages with food democracy in relation to the debate about sustainable food transformations in public-catering places. On the basis of fieldwork in public school food providers in Southern Germany, these FPC-inspired interlinkages of food justice (Alkon and Norgaard, 2009; Reese and Garth, 2020) and food democracy (Hassanein, 2008; Baldy and Kruse, 2020) will be pushed further by elevating the complex material, discursive, and governance aspects of food provision at the urban-regional scale. By highlighting the recent accounts of public food provision within state-funded public-catering places in Germany, not only the key factors and rewards but also the challenges of providing food in public catering places will be illustrated by back bounding them to the more recent debate on transitions toward sustainable food systems (Baldy and Kruse, 2020; Stein et al., 2022).

Methodologically, our study is based on the participatory action research (PAR) approach (Fals-Borda, 2000) and developed in cooperation with the FPC movement in the federal state of Baden-Württemberg. On the basis of the analysis of 17 qualitative interviews with different actors in the value chain relevant to the issue of school catering, including members of the university, city administration, the FPC, parents’ association, and pupils and a workshop with the German-wide FPC network, the argument is that the means to facilitate a more just and sustainable access to school food on the ground are still underexplored and that actual spaces for democratic participation to foster such developments are missing. By mapping the different scales of food provision, moments of food consumption, and levels of food governance, five key factors are developed, which are vital to foster further discussions about local food system transformations toward food justice in contested places such as public catering institutions in general and public-school canteens in particular.

2. Problem definition: nutrition, social-ecological inequalities, and school catering in Southern Germany

The global food system contributes around 30% to global greenhouse emissions and has thus a huge impact on climate change (Rockström et al., 2020; Crippa et al., 2021). The high incidence of child labor in Ghana, ongoing precarious working conditions in tomato greenhouses in Spain, and exploitative working contracts deployed in meat factories in Germany throughout the last decade highlighted that the current food system has not only a huge ecological but also an enormous social footprint which leads to rising social inequalities between “privileged and cash-poor customers across the globe” (Friedmann, 2005, p. 258). These and other troubling dimensions of local–global food production pushed advocates for food justice to reflect and rethink how our current globalized food system could be transformed into a more sustainable and just one on a more regional scale. Questions such as this have been increasingly raised by social movements, local initiatives, and critical scientists. However, they are not new or unique. From a historical perspective, Food Regime theorists have been criticizing the distancing of production and consumption by processes of global sourcing with the expansion of world market integration after WWII until today. These processes resulted (and still do) in more disaggregated global value chains and unequal power relations between local producers and transnational corporations. In this lineage, different conceptual frameworks have emerged, which aim to theorize the spatial and temporal distancing of global value chains. One of them is Philip McMichael’s notion of “Food from Nowhere” (McMichael, 2005, p. 287), which makes part of a corporate Food Regime and represents a model of mass production and processing of food and mass consumption within capitalist trade circles. In contrast, Harriet Friedman’s “Food from Somewhere” (Friedmann, 2005; see also: Campbell, 2009) refers to the search for more regional and ecological food sources which, however, often results in a two-class consumer society in which some privileged groups have access to quality food and others rely on buying Food from Nowhere. More recent studies in Food Regime Theory try to discover relational spaces in which –instead of focusing on nation-states– powerful regional networks (e.g., complex of food corporations) are visualized in order to explain regional political-economic dynamics within the global food system (Wang, 2021, p. 638).

While Food Regime Theory helps explain inequalities in the food system from a historical point of view, it is rather emblematic that often public discourse about sustainable food consumption focuses solely on the individual scale of consumers’ decisions, disregarding global inequalities at place (Brand and Wissen, 2017). However, we argue that local municipalities, specifically public food procurement, could provide an important leverage point for promoting sustainable food in a way accessible to all social sectors in the sense of food justice. Recent research projects (e.g., KERNiG), and policy papers underline the potential role of local municipalities for sustainable food transitions and offer concrete recommendations for policy measures (Schanz et al., 2020; Sipple and Wiek, 2023). Nevertheless, this potential role is largely underestimated, although in Germany, public catering entities serve about 12.4 billion customers annually, with rising tendencies (Speck et al., 2022, p. 2,288). Moreover, by promoting sustainable food services, cities can function as a role model for citizens, especially for pupils in the case of public school catering. However, due to neoliberal city management and outsourcing of public services in the last years, school catering was neglected, precariously financed, and externalized to private catering companies. In Germany, commercial catering companies deliver 88.7% of school food through the model of external provision. Only in a few cases (11.3%) school meals are produced in school-owned or municipality-owned kitchens (Jansen, 2019, p. 70). As the most relevant criterion for selection in public tenders is price, factors of quality and sustainability are seldom considered in the model of external provision nor is pupils’ participation encouraged (Jansen, 2019). Thus, this study aims to uncover the key factors and challenges for shaping school food systems in a more just and sustainable manner. From this, we deduce the following two research questions:

1. How are global food production, transportation, and processing networks reflected in local contexts of school cafeterias, the cityscape, and bodies of consumers (pupils)?

2. What are the key factors for cafeterias to become a more just and sustainable place within public schools?

3. Theorizing food justice and food democracy in the context of Food Policy Councils and sustainability transformations in school canteens

Our study interconnects food justice approaches with ideas of food democracy regarding public school food canteens in Southern Germany. Although these concepts have different origins, they have interconnected agendas, which perceive food as a common good to which all citizens should have access to and should be able to decide upon. To unpack their underlying normative ideas and to illustrate how these concepts are perceived by regional stakeholders and what the contradictions are when putting them into practice, each approach will be first introduced by emphasizing its interlinkages to what is at stake here: a sustainable food transformation for food provision in public schools. In this view, we will first highlight how FPCs try to articulate food justice and food democracy by creating spaces for democratic participation in the food system and by making it more just and regionally connected.

Food justice is a “theoretical, methodological, and aspirational framework” (Reese and Garth, 2020, p. 1) that emerged from the movement against environmental racism in the 1980s/1990s in North America, which was predominantly led by women of color. By addressing the unequal distribution of environmental benefits and the higher prevalence of environmental damages such as pollution and floods among lower-class, migrant, and Black communities (Alkon and Norgaard, 2009), environmental justice movements spotlighted multiple dimensions of environmental racism. Accordingly, food justice activists claimed that Black and migrant communities in particular have less access to fresh and affordable food and are more affected by nutritional diseases such as diabetes or obesity (Guthman, 2014). Continuing these debates and activists’ engagements, food justice theorists highlight the postcolonial continuities in the configuration of local food systems and analyze the underlying racist and patriarchal power relations that produce unequal foodscapes from an intersectional perspective (Winker and Degele, 2011; Miewald and McCann, 2014; Reese, 2019; Motta, 2021)—and which are still present and effective until today.1 The food justice approach thus differentiates various justice dimensions such as global justice, distributional justice, capability justice, and procedural justice (Tornaghi, 2017). As a proposal and a political perspective, food justice activists claim equitable access to fresh and healthy food (distributional dimension) and hope for higher democratic participation in shaping the local food system (procedural dimension). This connects with the claim for more food democracy, which was put forward by the FPC movement. From a feminist point of view, the dimension of justice involves also questions about the equal distribution and recognition of the care work for preparing food—a work often undervalued and disregarded, especially when undertaken in invisible private spaces (Tronto, 1993; Brückner, 2023).

The food democracy approach conceives of food as a common, jointly shared good (Helfrich and Bollier, 2019; Vivero-Pol, 2019). The idea of food as a commons was introduced by Vivero-Pol (2019), who differentiated, on the one hand, five dimensions of food as a commons: Food as a human right, as a renewable resource, as a public good, as essential for human life, and as a cultural determinant. On the other hand, he identifies as an opposing dimension the notion of food as a commodity (Vivero-Pol, 2019, p. 34 f). The dimension of food as public good departs from the idea that all citizens should have equitable access to food. Public goods are generated through collective choices, funded by collective payments and (e.g., taxes) owned through private, public or collective property regimes (Vivero-Pol, 2019, p. 35). This is connected to food citizenship, which implies that citizens have rights to decide democratically upon the food system and also responsibilities (Vivero-Pol, 2019, p. 35; Welsh and MacRae, 1998, p. 240). In contrast, the dimension of food as a commodity is historically rather new, having expanded in the last 200 years due to capitalist accumulation and expansion of global trade. Treating food as commodity implies that people are merely conceived of as consumers, and their rights and decision-making power are reduced to their ability to buy or avoid certain products and services (Vivero-Pol, 2019, p. 34f). In Germany, school food is increasingly becoming a commodity according to the notion of food as tradeable good by Vivero-Pol (2019) due to the growing outsourcing and externalization of public services to commercial providers in recent years.2 According to Hassanein (2008, p. 290ff), food democracy is expressed by five key aspects, two of such are “becoming knowledgeable about the food system” and “acquiring an orientation toward food as a community good.” These aspects show the importance of raising awareness and sharing knowledge about food and food systems as a precondition to exercising food citizen rights.

The promotion of food democracy was brought forward by the rising FPC movement, which emerged in the context of the 1980s and 1990s in North America as an answer to the above-described problems of food racism in lower-class and Black neighborhoods. In Germany, the first FPCs were founded in 2016 in Cologne and Berlin, two major cities that were already strongly engaged in urban gardening and where community-supported agriculture (CSA) initiatives already existed. Their motivation was to expand their efforts from the local scale of neighborhoods toward the regional scale of the city and its surroundings and to build up networks with the surrounding rural communities with the FPC as an integrative platform. Currently, there are more than 70 FPCs in German-speaking counties.3 Some of them are already well-established and financed by the city administration (e.g., Cologne, Freiburg, Oldenburg). Others are organized at a voluntary level, which requires more effort from their members in their free time to coordinate the activities and projects (see for more information: Sieveking, 2019). The FPCs are usually organized as associations with spokespersons, a coordinating committee, and working groups, which are open to the participation of local and regional citizens. Main areas of activity of these working groups are the promotion of biodiverse agriculture, regional value chains, edible cities, education, and public catering. The FPC’s action area of public catering (especially school catering) will be the main focus of this study.

Grounded on the empirical insights gained through participatory observation and interviews and the collaboration with FPC in Southern Germany, we analyze how food democracy and food justice are articulated, hinder or undermine each other, when putting from theory into practice. In doing so, we draw on and depart from the uplifting and utilization of feminist notions of scale (e.g., the body and workspaces) for our mapping of socioecological inequalities within urban food systems.

4. Methods: participatory action research and mapping of global intimacies of food production, consumption, and working conditions in public catering areas

This study is inspired by and based on feminist geographical scholarship and research practices, which include reflecting our own positionality, being sensitive of the situatedness of the knowledge we reproduce and co-produce, and our entanglement with field relations, providing us with conceptual understandings of positionality and situatedness (Haraway, 1988; Ahmed, 2007; Billo and Hiemstra, 2013; Faria and Good, 2015; Coddington, 2017). Our positionality is linked to our experiences as white female academic researchers from a lower-class family background. Both of us have not been to a school where public food was provided. Our personal perspective on this topic is first and foremost related to our three-fold role as scientists, activists, and mothers, as one of the authors is engaged as chair in a local FPC and is single mother of a 13-year-old child. On the one hand, these rich experiences and entanglements enabled access to as well as some first-hand insights into activist and school contexts. On the other hand, being deeply inspired by PAR, our positionalities and collaborative approach also implied possibilities to co-reflect and re-think our own viewpoints on school food and normative issues of social justice together with actors involved in this research (Kindon et al., 2007).

PAR aims to merge research with action to transform social realities (Fals-Borda, 2000). In this case, our study is conducted in cooperation with the FPC movement in Germany. The underlying idea of this research was presented at three occasions to the groups involved (e.g., in the German-wide network meeting of FPCs in Cologne in March 2023) to receive feedback on the methodological procedure and to gain insights on what research questions, prompts, and notions of food justice, sustainability, and public catering are of interest from the activist’s point of view. By analyzing the key factors of and barriers to organizing school catering in a more just and sustainable way and by feeding back results, this research aims to contribute to the knowledge exchange and conceptual growth within the FPC network and beyond. In this way, we are especially highlighting key factors and hurdles that emerge when implementing these ideas on the ground in school canteens and dining halls from both angles—those, who organize, produce, and process public food (municipal city governments, school administrative, canteen staff, local farmers, etc.), and those supposed to pay for and consume it (parents and pupils).

In doing so, our study aims to (a) integrate and contrast viewpoints from the different actors all along the school catering value chain and (b) visualize them in a less textual, more space-related way. To this end, 17 interviews were conducted between October 2021 and 2022. These interviews had an exploratory character to gather the perceptions and visions of school food actors about their understandings of sustainability and justice. Thus, the interviews were initiated with open questions on these terms and then a semi-structured questionnaire followed (see Supplementary material 1). In the selection of the interviewees, the aim was to gather the perspectives of the actors of the different stages in the school catering value chain (producer organization, kitchen management, city administration, parents’ association, pupils, and teachers). Different models of school catering organizations (school-owned kitchen, municipality-owned kitchen, and catering company) were taken into account, as well as different regional foci within Southern Germany (Freiburg, Tübingen, Rottenburg, Mannheim, and Munich).

Additionally, four interviews were conducted with pupils to gain some qualitative insights into their perceptions of school meals. For this questionnaire (see Supplementary material 2), our questions were adapted to make language accessible for the target group. The questionnaire started with entry questions (“What is your favorite meal at school?”) and open brainstorming questions about their first associations when hearing the term “sustainability.” In the next step, we were asking questions on how their understandings of sustainability relate to their current perceptions and visions of school food. For these interviews, different age groups (12 years–15 years), school types, and genders were considered, although all pupils have at least one parent with an academic background. For the analysis, all empirical material was revised and restructured to identify and illustrate the five key factors and challenges that seem to be central to organizing school food in a just and sustainable way. To this end, all interviews were coded and analyzed with the software MaxQDA according to a previously defined codebook by organizing the entries along the predefined categories: “sustainability,” “participation,” “food justice,” “spatialities,” “key factors,” and “challenges.”

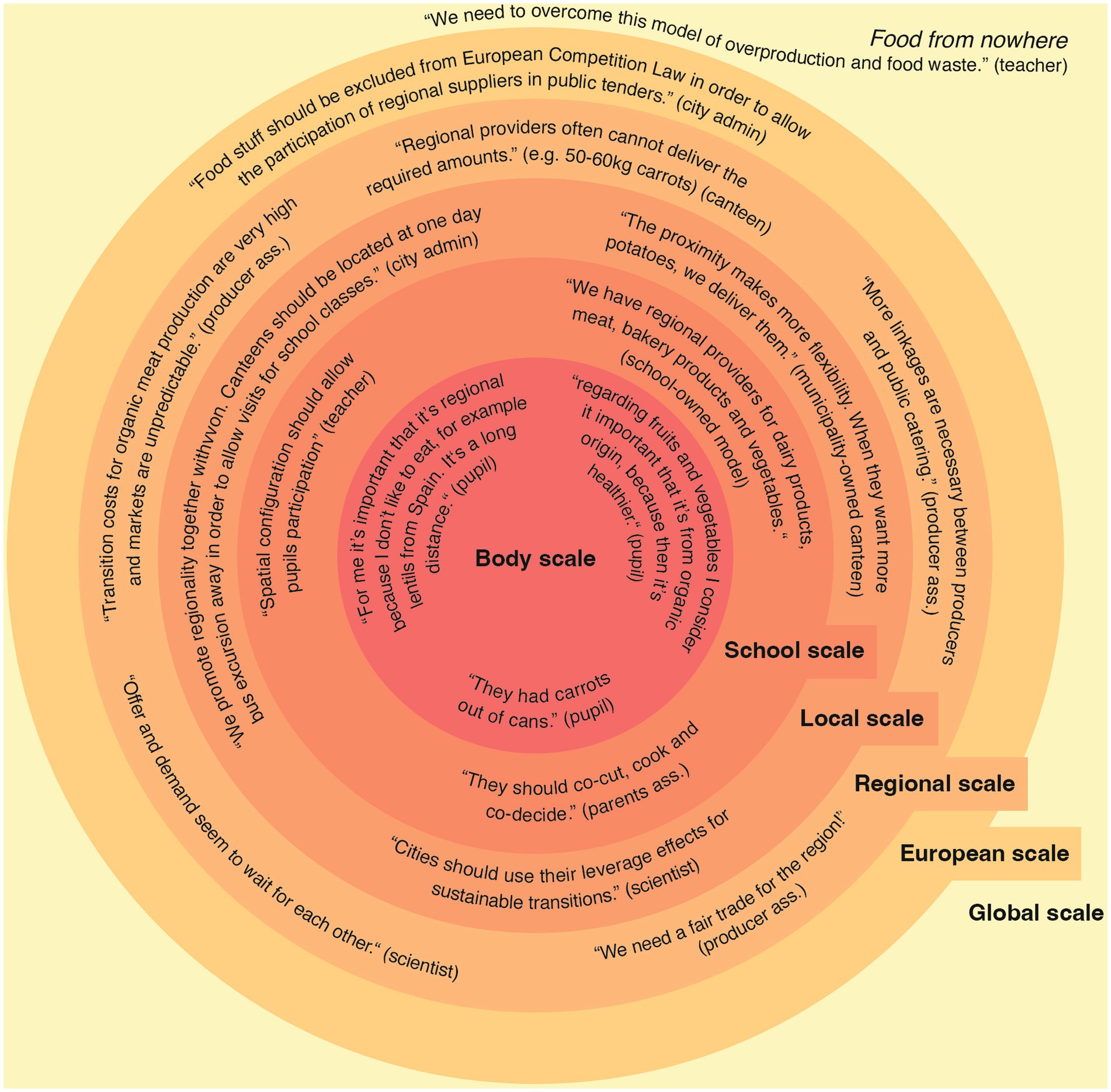

Inspired by feminist approaches to Geographical Information Systems (GIS; Elwood, 2015; Whitesell and Faria, 2020), the food industry at play was mapped across the body, the city, and the global scale. By grounding the underlying macro (geo-)economic shifts in the experiences of pupils, their parents, public kitchen workers, and local farmers involved in the public food provision in school cafeterias, our insights revealed some of the cross-scalar political economics of food democracy and food justice. Thus, a form of “global intimate mapping” was developed (Whitesell and Faria, 2020, p. 1276; Klosterkamp, 2023) to find answers empirically to the central research questions introduced at the beginning.

Of particular influence to our mapping project are early feminist engagements with GIS (Kwan, 2002; Pavlovskaya, 2002; Elwood, 2015), which made visible the embodied, gendered, and relational spatialities of commonly ignored and marginalized subjects. In this way, we elucidate the paradoxes (re-)produced through the co-existence of “Food from Nowhere” (McMichael, 2005) and “Food from Somewhere” (Friedmann, 2005). This approach also helped us to take a closer look at the processes of including sustainability criteria in the public food sector and associated contradictions (see Figures 1–3). The overall goal of this investigation was to integrate and contrast the various perspectives of different actors all along the value chain of public school catering—from production, (re-)distribution, and meal preparation to consumption—to be able to portray a more grounded picture of the global-intimacies of the global–local food economies at play, when it comes to public food services.

Figure 1. Learning from best-practices: spatial dimensions of regional vs. global food production and food transportation. © Irene Johansen, Sarah Klosterkamp & Birgit Hoinle.

Figure 2. Mapping toward food justice: unfolding social-economic inequalities in the context of school catering in Southern Germany. © Irene Johansen, Sarah Klosterkamp & Birgit Hoinle.

Figure 3. Unpacking the global–intimate dimensions of food production, food transportation and food consumption. © Irene Johansen, Birgit Hoinle & Sarah Klosterkamp.

5. Results

In the following section, the results of the analysis are presented, focusing on the main potentials and obstacles for establishing a higher degree of sustainability and food justice regarding school food systems. We also analyzed the enabling as well as hindering spatial factors and visions for a future school food system, which pupils and working staff mentioned during the interviews. The results show the various perspectives of the different actors on the categories of sustainability, justice, and spatial factors.

5.1. Sustainability in school food—various dimensions

When openly asked about sustainability in school food, interviewees mostly mentioned regionality and organic production as criteria. When explicitly asked about the social dimension of sustainability, most interviewees referred to working conditions in the school catering companies/school kitchens or to fair trade. During the interviews, they stated further criteria of sustainability that were not addressed by our guiding questions but appeared as relevant topic for the actors: above all, animal welfare, reduction of packing material, energy-saving cooking, and most important of all, food waste reduction. Interestingly, the interviews with different stakeholders and FPCs indicated that best-practice examples to meet these demands are already available. Among these are municipalities that demand a high share of organic food (50%–75%) in their public tenders. In this regard, the cities of Nurnberg and Munich were most often mentioned. Augmenting the share of organic food in public tenders was seen as an important incentive for contributing to a “resilient agriculture” (Interview No 4), which was considered as being necessary for organizing value chains in a more sustainable way. Additionally, the interviews also allowed to better understand some of the key difficulties that producers face—such as unpredictable demand shifts and high costs for certification processes—in the transition toward organic farming.

As one representative of a producer association mentioned, the transition to organic farming is fraught by high risks and may entail existential economic threats for producers because of high costs for meeting animal-welfare standards that raise product prices (Interview No 1). Herein, one crucial point is meat. Transitioning to organic meat production involves large investment in facilities (e.g., appropriate cowsheds) and further efforts to reorganize fodder supply chains (e.g., GMO-free, local). To make these efforts requires stable demand in the longer run (Interview No 1). Indicating Munich as an example, several interviewees disagreed with the general view that organic food in public canteens is necessarily more expensive than conventional food4, yet the example of Munich showed strategies to offer organic food in a cost-neutral way. From the perspective of the farmers, cooperation with public procurement has a huge unexploited potential, but at the moment, there are still very few direct linkages between producers and public consumers (Interview No 2). Whereas school-owned and municipality-owned kitchens have more flexibility to integrate organic providers into their menu planning, the transition to increasing the organic share in public tenders is more difficult because contracts between city administrations and commercial catering companies last for about 5 years, inhibiting rapid changes in public procurement. As one interviewee expressed, a higher rate of organic products does not necessarily imply regionality “when the organic tomato sauce comes in cans from Italy or Turkey” (Interview No 1). In his eyes, not only share of organic food should be raised, but also regional value chains should be promoted.

Regionality is one of the most desired sustainability criteria, however it is often restricted by legal frameworks. In middle-sized cities such as Tübingen or Freiburg, due to European law, the total sum of the school food supply requires to announce the tender on a European level. This legal setting makes it rather difficult to integrate regional value chains as part of a sustainability strategy. The models of canteens owned by schools or municipalities have more potential to promote regional food as “proximity allows more flexibility” (Interview No 5). The municipality-owned and school-owned kitchens of this study are already working with a (limited) list of regional suppliers for certain products, such as potatoes, bakery, and milk products. In the interviews, seasonality was often mentioned as an important sustainability aspect. Defining a seasonally orientated menu plan as a requirement in public tenders also helps promote regional value chains. This can mean “pumpkin soup in autumn and no tomato salad in winter” (Interview No 14). From the perspective of the representative of the city administration, seasonality is a good way to promote regional offers, but the challenge is that pupils find the typical German dishes of autumn and wintertime (e.g., cabbage) attractive (Interview No 15). In our study, the school-owned and municipality-owned kitchens are already actively promoting the issue of seasonality—e.g., by adapting the menu plans to seasonal offers. Freshness is also an important issue for them: “We make all the 650 meatballs by ourselves, and also all sauces” (Interview No 5).

However, one of the main challenges in the implementation of a higher degree of regionality in public-school catering is in terms of scale: sometimes large kitchens need a vast amount of products (e.g., 50–60 kg of carrots), which small-scale regional producers cannot provide regularly because the caterers need the products all at once or in an already-processed format (e.g., peeled potatoes) to reduce the workload and, thus, depend on low processing costs and time. As one member of a producer association highlighted, maintaining the regional structures of food processing (e.g., mills, dairies) had no political priority in the last decades and should be promoted more: “We need a fair trade for the region” (Interview No 6). Given the legal constraints, very few municipalities make efforts to integrate and amplify regional value chains to supply schools–one of them is depicted in Figure 1. Here, three flows of commodities are visualized: goods from national and European origin with transparent origin, as well as goods with unclear origin in school canteens which underlines the notion of “Food from Nowhere.”

Food waste was a highly discussed topic in nearly every interview. It is directly related to pupils’ low acceptance rates of school food. Here again, the different models of food supply make a difference. In the school-owned kitchen of our study, every pupil from 1st until 6th grade eats every day at the school canteen. This habit makes it easier for the kitchen management to calculate the required quantities and to avoid food waste. As highlighted by the parents’ association, “they work with exact portion sizes. When it is too small, pupils can go for second helping” (Interview No 8). In the municipality-owned kitchen, the proximity allows more flexibility: “When they like the potatoes, we can bring them more” (Interview No 5). In our study, in the schools provided by external caterers, the high absence rates make it difficult for caterers to calculate the exact amount of food needed for the lunch breaks. Many pupils prefer to go to the city center and buy food elsewhere instead of having lunch at the school canteen. The unclear number of eaters is a challenge for kitchen management and generates high amounts of food waste. For instance, the city of Mannheim has developed a strategy to reduce food waste, which includes the regular adoption of portion sizes and a feedback system (Interview No 14).

5.2. Food justice—visions and challenges in public school canteens

All interviewees were asked about their vision on food justice and the role the issue of diversity plays in school meals. The answers reveal a panorama of visions by different actors and pupils—but also a lack of meeting specific dietary, economically-driven, or culturally-embedded needs, when it comes to public food provision in school canteens.

Working conditions in school canteens are crucial regarding the issue of food justice. In the municipality-owned kitchens, the municipality employs all kitchen workers, who receive a regular salary based on a labor contract in the public sector. In the case of school-owned kitchens, the school association employs only a few professional cooks, so parents also have to voluntarily help out with activities such as cutting vegetables, serving meals, or cleaning up afterward. One of the parents highlighted that at their school, not only the mothers but also the fathers are involved in this duty called “Kocheltern” (“cooking parents”; Interview No 8). From the perspective of a teacher who had the opportunity to know other school systems during exchange programs, in France, schools usually have their own kitchen, where employed workers prepare and serve meals: “I do not know any other scholar system where there are less employed people at schools than in Germany” (Interview No 12). Her statement shows that much more permanently employed personal resources would be necessary to improve school food quality.

There is a lack of knowledge about the working conditions of the staffs within the private catering companies. One interviewee explained that in the last decades, the food sector was economized and externalized, resulting in negative consequences for the working conditions—all of which also influenced the quality of school meals. As such, the demand for better recognition for the work of kitchen employees was visible in several interview statements: “The kitchen should have a feel-good atmosphere; people should like to work there” (Interview No 4), or “The workers should have space for creativity and for trying out new recipes” (Interview No 6). Regulated working hours, a fair salary, and a good quality of apprenticeship are also considered necessary (Interview No 6). In the workshop with the FPC, participants formulated a clear need for a better political and societal recognition of the profession of cooks in public canteens. In view of the rising requirements (e.g., hygiene standards, punctual delivery, etc.) for kitchen work, interviewees claimed that this situation should also be reflected in better payments and further education offers.

Regarding the issue of diversity, future school organization faces several challenges which could also be seen as potentials. The expert from a consultancy agency highlighted that diversity (in terms of diverse dietary or intercultural eating habits) has not been well considered and taken into account at the majority of school canteens (Interview No 3). Until now, this lack has been reflected only through offering dishes without pork meat for children of Muslim backgrounds. According to the interviewee’s statements, further aspects of diversity that take into account the different needs of people from diverse cultural backgrounds are not considered yet. One interviewee claimed that the canteen organizers should better consider the needs of refugee children as sometimes the (regional) names of the southern German dishes (written in German dialect) are not understandable for German learners (Interview No 3). When asked about diversity, a member of a producer’s cooperative stated that there is a lot of underexplored potential for this topic: “We need more out-of-the-box thinking and cooking” (Interview No 6). One project manager added that cuisines from other regions have a lot of potential regarding sustainability as many of them (such as Eastern European and Arabic countries) cook legumes such as lentils or chickpeas as plant-based proteins. She states that there is a “huge culinary playground” for creativity to discover new things from other kitchens (Interview No 4) by admitting that these potentials are so far not well developed at all.

These observations illustrate that school food is an inherently social justice issue. The provision of sustainable school food could be an approach that allows all children (regardless of class, race, parents’ income, etc.) access to fresh and healthy food in the sense that food is a common good (Vivero-Pol, 2019, see above). Our results illustrate again the often contradicting demands and realities on the ground: considering the rising rate of children from migrant families being integrating into the school system, the issue of diversity or diverse eating habits are not sufficiently accounted for in the meal compositions. At the same time, more and more middle-class parents demand wholesome, organic, and thus healthy food on their children’s plates, and in contrast, working-class families would not be able to afford this or would need more than the existing state subsidies for it (Morgan, 2015; Krüger and Strüver, 2018; Augustin, 2020; see for general comments: Haynes-Conroy and Haynes-Conroy, 2013; Shannon, 2014). Although municipalities provide subsidies to make food accessible for all families, the subsidies depend on each municipality’s decision and economic power.

When asked about their visions for a future school, pupils had several (visionary) ideas: One was to integrate local gastronomy (his favorite restaurant has West-African dishes) in the school canteen because of its good taste (Interview No 11). Others said that children should “look forward to going eating there” (Interview No 10). In her eyes, always having vegetarian and vegan options should be “normal” (Interview No 10). When asked about their vision for food in a future school, parents and teachers referred to the issue of participation: “They should co-cut, co-cook, and co-decide” (Interview No 8). They also proposed formats, such as school conferences, which allow more pupils to participate or own working groups run by them. Schools having their own canteen with “diverse, regional, organic, and seasonal food” was considered important (Interview No 12). Here again, the emphasis was on the participation of pupils in the cooking and decision-making processes to address the formulated necessity that they regain the connection with food and learn to value it (Interview No 12). This change would also require more efforts to connect the transition with a holistic education concept that makes learning about regional food cultures part of the curriculum (Interview No 8). From the perspective of project coordinators, school canteens could be the places in which pupils learn “sustainable eating habits for the future” (Interview No 4).

5.3. Space matters—underestimated aspects of school food consumption spatialities

According to feminist and critical geography, the shaping of space reflects societal power relations – it is a space produced and reproduced by social processes (Belina and Michel, 2011). In the case of school food, many canteens reflect decades of political disinvestment and disinterest. The category “space” was not considered at the beginning of the questionnaire but came up during the first interviews as a crucial aspect for evaluating school meal organization. As highlighted throughout many interviews, space matters often immensely, as it renders and shapes the atmosphere, wherein food is socially consumed and shared: From the consultant’s view, “food is a social process”; in his eyes, it makes a difference, whether the canteens are designed as “feeding centers” or “places of wellbeing” (Interview No 3). In a similar vein, it was critized that psychology and needs of teenagers were seldomly considered when designing the architecture: “The elder ones want their own spaces (…); they do not want to sit next to the ones of the lower grades” (Interview No 4). The representative of the parents’ association also highlighted transparency of the kitchen as an important feature: “In our school, you can look directly into the kitchen; everything is transparent, very open, with glasses. Pupils can have a look on how they cook” (Interview No 8).

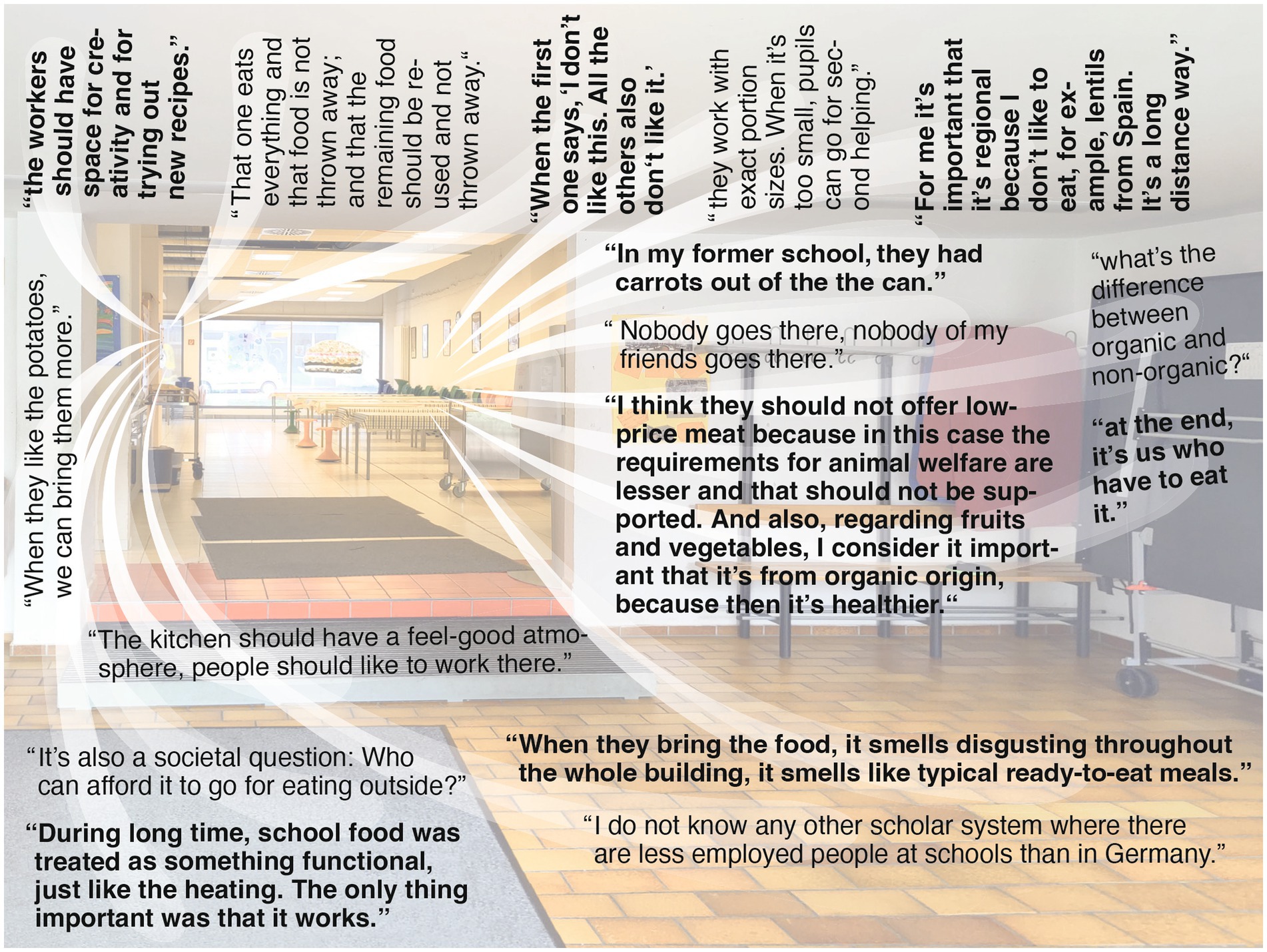

In our interviews, we asked pupils whether they like or dislike to go to the school canteens. From their perspective, first, high degrees of dissatisfaction with the food offered by private companies became evident during the interviews: “Nobody goes there; none of my friends goes there” (Interview No 11). “When they bring the food, it smells disgusting throughout the whole building; it smells like typical ready-to-eat meals” (Interview No 10). In light of the bad image of the school canteen, the teacher’s perspective helped to explain the group dynamics among the pupils: “When the first one says, “I do not like this.” All the others also do not like it” (Interview No 12). When asked about their wishes for school meals, pupils especially highlighted the need for freshness: “In my former school, they had carrots out of the can” (Interview No 11). When asked about their ideal canteen, pupils considered it important that they could sit with their friends and that the teachers do not prearrange the sitting order. Another interviewee mentioned that for her, “cleanliness” is important when eating with so many people and that she would like decorations on the tables (Interview No 10). Others wished for more comfortable sitting zones and a more friendly and colorful space design with “images on the windows” (Interview No 17).

The school canteen architecture is important for not only the pupils but also the staff: In some cases, the teachers also go and eat in the school canteens. The interviewed teacher states that in her school, teachers do not have enough space. If they want to eat the school meals the canteen offers, they have to take them in a box to the staffroom and eat there (Interview No 12). In her eyes, the spatialities of the canteens are very important: “There should be enough space; it should be a building with glass fronts and should have a view toward the urban green with comfortable sitting corners inside. Ideally, it should be designed as a multiuse building so that during the day, it can offer space for pupils to work there in the afternoon, and in the evening, the hall could be used for events” (Interview No 12). The spatial configuration also influences the quality and variety of school meals. She mentioned one example in which there is space for a salad bar, pasta bar, and certain action weeks, which attract the attention of the pupils (Interview No 8).

In combing these different accounts of pupils’ and teachers’ perceptions of the spatialities of school food provision with feminist qualitative mapping techniques, Figure 2 illustrates “the layered insights that feminist epistemologies and methodologies afford” (Whitesell and Faria, 2020, p. 1,277). The quotes visualized here reflect upon the different perceptions and visions of actors of the school value chain (including pupils) at place, by drawing specifically on the pupils’ demands on how the school canteen may become a more welcoming and social space.

6. Toward a more just and sustainable school food system?

“We have already a lot of good examples and schools that cook on their own, but we need to change the structures” (Interview No 3). But who decides upon what? To what degree can citizens participate in and shape the local food system to meet the economic, political, and sustainability demands? In the following, we want to highlight crucial aspects for food justice discovered in our analysis, one of them is educational offers regarding food sustainability. These were seen as crucial in improving the acceptance and participation of pupils (Interview No 7). Although since the year 2016 in the curriculum for the federal state of Baden-Württemberg, sustainability and health are introduced as cross-cutting perspectives that every teacher should integrate into her/his lessons, food sustainability results often more as a “nice to have” topic but not as an integrated content of the curricula (Interview No 15).

Several interviewees stressed that relying on voluntary initiatives of singular schools is not enough and that, instead, political guidelines should be formulated to effect change toward a more just and sustainable school food organization. This move could be initiated on a local scale with a decision of the municipal council in which, for example, the increase of the share of organic and fair-trade products in public catering is defined. It was positively mentioned that, for instance, the federal state of Baden-Württemberg defined the goal of 30% organic food share in public catering as a political goal. As a concrete measure, the “Biomusterregionen” (organic model regions) were established to promote organic agriculture and value chains on a regional scale (Interview No 9). Political incentives such as the promotion of the network of “Biostädte” (organic cities) were considered relevant in the exchange of experiences between cities in the process of transitioning (Interview No 3). On a European scale, one interviewee demanded that foodstuff should be exempted from European competition law to allow the participation of regional providers in the public tenders for school meals (Interview No 15). Thus, our interviews illustrate that much more political will, educational efforts, and public investment are needed to put these measures into practice to promote changes on a more structural level.

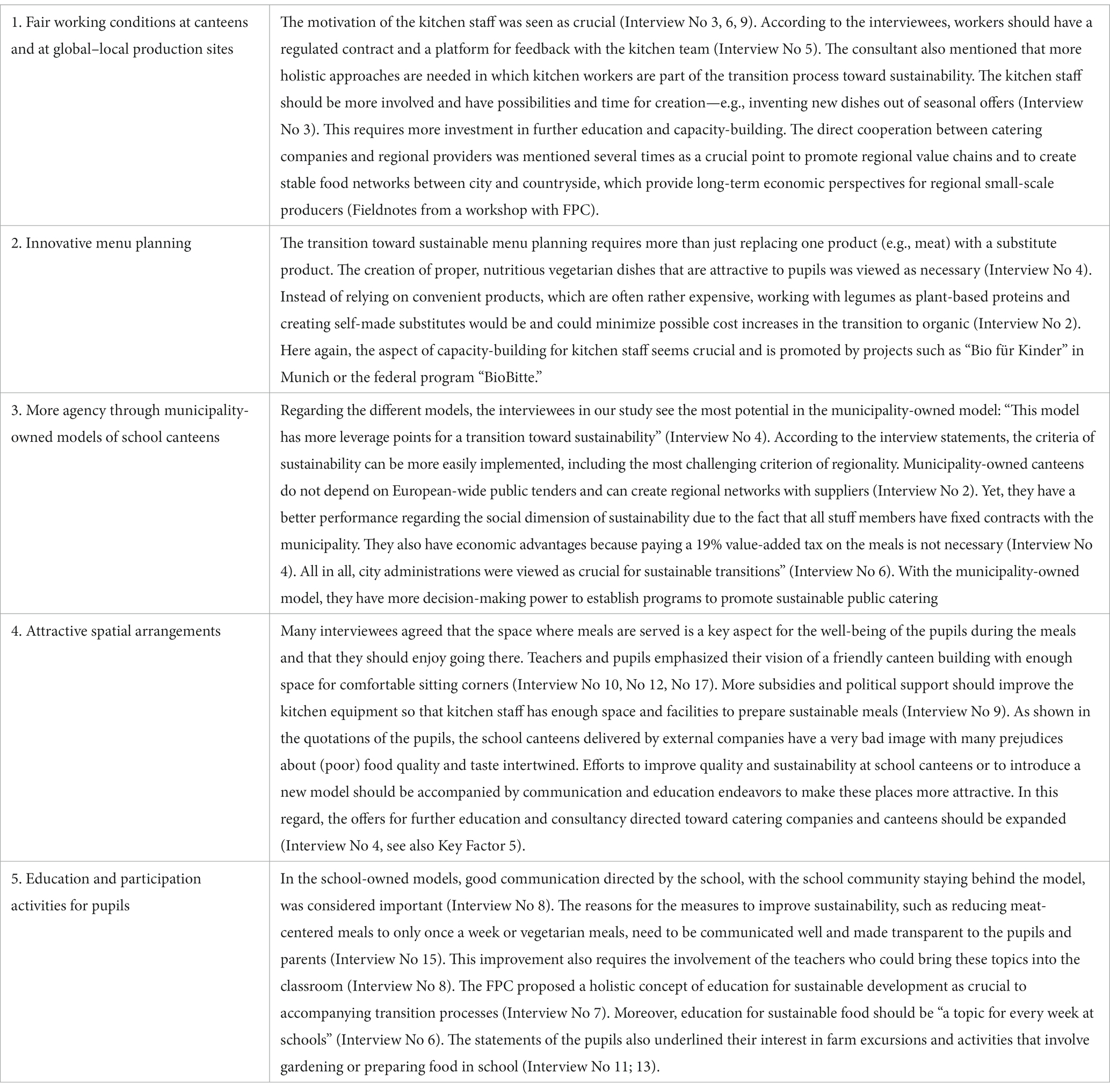

In our overall analysis of the empirical insights, several key factors and challenges that promote or hinder the transition to a more sustainable and just school food system were identified (see Table 1). Among these, fair working conditions at the canteens, menu planning, different models of ownership and governance of public canteens, and attractiveness of the eating venue are all favorable factors and shall be discussed in more detail below.

Table 1. Key factors for a more just and sustainable school food system, elaborated based upon empirical results (own source).

All these favorable factors are often not implemented for various reasons: (1) a lack of regional networks, (2) economic constraints, (3) the lack of political will, and (4) a huge dependence on voluntary work, which can also shape the implementation of a more just, sustainable, and less exclusive public catering food system.

First, the lack of regional networks has been mentioned throughout all interviews as one of the main challenges. Particularly, interviewees referred to the missing links between producers and public catering institutions: “They seem to wait for each other” (Interview No 2). As explained, producers reclaim missing regional marketing possibilities, whereas catering companies and municipalities argue that regional and organic offers are not enough. In this regard, one difficulty is that larger kitchens need the products in huge amounts, and often, they need them already processed. However, in the last decades, many already-existing regional processing facilities, such as mills, slaughterhouses, or dairies, have closed. Political efforts are necessary to promote processing structures to maintain the full value chain of a region and connect them with the supply of public catering institutions. In this regard, the example of the “organic model regions” was outstanding as they undertook measures for promoting a platform in which canteens could find regional and organic providers and organized network meetings between producers and catering companies (Interview No 9). In a conceptual dimension, the promotion of regional food networks could contribute that pupils – instead of receiving “Food from Nowhere” (see McMichael, 2005)—could experience where their food came from and who is producing their food in the sense of a “Food from here” (Schermer, 2015).

Second, economic constraints were mentioned in several interviews, by drawing on a wide variety of different challenges throughout the production process and distribution of food, that come into play in school canteens, such as (a) rising prices due to inflation and economic crisis (Interview No 5), (b) high investment costs for transitions toward organic meat production (Interview No 1), and (c) difficulties of small-scale producers to make a living out of organic farming (Interview No 6). From a producers’ perspective, one main challenge was the missing planning reliability due to an unpredictable and volatile market situation (e.g., in the organic sector). In this regard, direct cooperation schemes with public catering would be a way to develop long-term perspectives for regional producers and processors (Interview No 1). The two producer associations interviewed in this study still do not cooperate with public catering but considered this as their future project.

Third, and as illustrated in Figure 3, many interviewees discovered a “lack of political will” (Interview No 12) that hinders, for instance, investment in public catering that would improve the sustainability and quality of school food. At an organizational level, sometimes, persons in leading positions were observed to end up being “the bottleneck” as they promoted or constrained efforts toward more sustainability based on their individual opinions (Interview No 2). In this regard, establishing political guidelines as orientation was viewed as necessary (Interview No 4).

Lastly, the example of the school-owned canteen illustrates how several initiatives already on a promising transition toward sustainability still highly depend on voluntary work or parent engagement (Interview No 8). However, not in all social contexts are parents in the appropriate condition or have enough time capacities to contribute with their unpaid work (e.g., single parents). While the type of school-owned kitchen was especially motivated by parents’ dissatisfaction with the predominant externalized model of school food, it is thus not easily transferable to other (less privileged) contexts. The parents’ reliance on unpaid voluntary work makes it likely that women take over this work and that a gendered division of labor is reproduced in a similar vein as in household economics. The logic is related to the missing recognition of cooking as an essential care-work for the well-being of society (in this context in public school catering places).

Figure 3 illustrates the challenges for providing school food in a more sustainable and just manner on different scales, ranging from the body scale up to the local, regional and global scale of food consumption and production, closely aligned to our findings. As such, this figure illustrates that efforts to improve food justice in school canteens have to consider different scales to develop better action strategies toward social justice and sustainability along public food provision, by reforming European law (European scale), improving networking of producers and canteens and by incentivizing new value chains on regional scale.

7. Conclusion: who decides about school food?

Our results show key factors for organizing school food systems in a more just and sustainable way in Southern Germany and beyond, although these processes are related with several challenges.

Following the lead of Whitesell and Faria (2020), and as such, by incorporating feminist methodologies with GIS technologies, the aim was to highlight and amplify often-unheard voices within the public food system, such as that of pupils and parents of public schools, and their visions for a transition to a more just and sustainable space. As such, our study tried to integrate the grounded viewpoints of local consumers with the production needs and price sensitivity of transportation modes (see Figure 1), deeply connected and rendered by each type of food that gets served and combined as a meal plan (see Figure 2) or referred to as a democratic, sustainable, and more just undertaking within the region (see Figure 3). Mapping these economically vibrant, socially distinct, and (trans-)national spaces of food production, transportation, and processing within the food system of school cafeterias offers new and layered understandings of the global, political, and economic shifts reshaping the economies of public food provision in Germany. By back bounding these findings to the theories in place, our empirical insights also illuminate further research areas for the study of Food Regimes, and globalization in and through the food system and its underlying (in)justices, contradictions, and aspirations in multiple ways.

Regarding sustainability, several examples of already engaged municipalities were identified that were on the way to improving the share of organic food in school meals. The municipality-owned kitchens were discovered to have more potential for better working conditions than the school-owned and externalized models, because canteen workers have fixed, long-term treaties with a public institution there. Regarding the criteria of regionality, the municipality-owned model has more possibilities to promote and build up regional value chains. This opportunity is connected to the spatial and social dimensions of sustainability because the integration into regional networks could help small-scale farmers to have a steady demand for their products in public catering entities and offer them economic perspectives. Several interviewees (including pupils) referred to food waste as a highly relevant topic of sustainability. In this regard, the need for further research was identified to develop strategies for avoiding food waste in terms of kitchen organization and more sustainable ways of reusing the waste (e.g., biogas systems). For us, food waste is not only a regional problem but also an international one, taking into account the global justice dimension of food and its socioecological inequalities of overproduction and food poverty all along the value chain.

Regarding the aspects of food democracy and food justice within the transition toward a more sustainable and just public feeding within the school-food-provision economy, only the model of municipality-owned canteens was discovered to correspond to the dimension of (school) food as a public good according to the notion by Vivero-Pol (2019) and, thus, may be best positioned to take a lead here for other school food policies to follow. The school-owned canteens also demonstrate these potentials to a lesser degree. However, although in the school-owned models, the school community (teachers, parents, pupils, etc.) has more decision-making power to define the guidelines of how a canteen works, they depend on the voluntary engagement of parents, which can reproduce the gendered divisions of care work (cooking) and exclude people from less privileged contexts. This highlights the need for more research on the role of inclusive and democratic participation in the school food value chain and the potential role of civil society initiatives and FPCs to foster stronger collaboration bonds and regulations between all parties involved. Freiburg was the only example in this case study in which fruitful cooperation between the city administration and the FPC had been already established, which led to several progressive political measures such as the promotion of regional providers for school food in public tenders, combined with educational offers for pupils. Nevertheless, and while much still remains in flux, first studies draw on FPC in Germany, France, and Switzerland and provide first comparative insights to their roles as leverage point for sustainable food transitions and food democracy approaches (Michel et al., 2022).

Overall, regarding the visions for future school meals, all interview participants saw the need for pupils to have more spaces of democratic participation in the school food organization and menu planning—e.g., in formats such as school conferences or working groups. As the results show, the involvement in the kitchen process also has an educational dimension such as learning where food comes from and how it is prepared, which then could also foster broader debates on the value of food and the (invisibilized) labor behind the production and preparation process. Efforts on making the often challenging and precarious working conditions behind the food “visible”—in the production and cooking process—can be seen as one of the most relevant urgencies for changes in the school food system. From a feminist point of view, the missing societal recognition of the care work for preparing food (in this case in public canteens) is a crucial aspect in this regard, so far often left aside. Thus, as our findings show, an improvement in working conditions in public canteens, the promotion of regional value chains that integrate local small-scale producers, and a better recognition of the profession of a cook are key factors (see Appendix) for making “Food from Nowhere” visible and tangible—and in this sense, for fostering social-ecological transitions in the global–local food system which integrate more “Food from Here” networks. Our final conclusion is the grounded notion that a more holistic approach is needed in which all actors involved within the school food value chain work together to promote long-term changes in the local–global food system in Germany, and elsewhere. According to our results, public provision can be an important leverage point for transitions toward sustainability and social justice. However, as the analysis of challenges also highlights, several structural, legal and economic constraints barriers impede the evolvement of these potentials currently. Thus, much more political efforts and measures, such as the promotion of regional value chains, stronger efforts and improvements of working conditions at canteens remain necessary to convert public canteens into “transformative places” under unjust conditions.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)' legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors want ot thank all our interview partners and all those who took the time to give us an inside view of their work and visions. Especially we are grateful to the Food Policy Council network and other regional stakeholders for having the opportunity to exchange ideas on the proposal in workshops and network meetings. Furthermore, we would like to thank Irene Johansen for her work on and help with developing (Figures 1–3). Without her open eye and expertise, we wouldn’t have been able to implement these in such a great way. Our thanks also go to the chair Societal Transition and Agriculture at University of Hohenheim for making possible the open access publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2023.1085494/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^As a more recent example, Reese (2019) describes in her work “Black Food Geographies” the histories and trajectories of Black working class families in Deanwood, Washington, D.C., which were affected by public disinvestment in the 1970s/1980s. Here, supermarkets relocated to wealthier neighborhoods, grocery shops closed, and the remaining shops offered mostly fast food and frozen foods. This shift resulted in an unequal foodscape: “In Washington, D.C., the chance of a full-service grocery store being nearby depends on where a person lives. And, where a person lives, is highly dependent on race and class” (Reese, 2019, p. 47).

2. ^In contrast, Brazil is an example of a country that treats food as a public good in school canteens. Due to the efforts of the Brazilian FPC called CONSEA (Conselho Nacional de Segurança Alimentaria), which was founded in 2003 on a national scale, an innovative political program (programa nacional de alimentação escolar PNAE) was established in 2009, which sets very progressive requirements for public food provision. In Brazil, 30% of all food delivered to public institutions comes from familiar agriculture, which means a regional and usually an agroecological origin (Nogueira and Barone, 2022). The food in public schools is delivered to all pupils free of charge. Although the funding for PNAE was cut down during the former government of Bolsonaro (Mendes, 2022), Brazil provides an innovative approach to how food democracy and food justice can be practiced. With the government change in 2023, the reinstallation of the CONSEA and a stronger promotion of the PNAE is to be expected in Brazil.

3. ^See map of the existing Food Policy Councils and initiatives on: https://ernaehrungsraete.org/ (Accessed 28 June 2023).

4. ^The city of Munich was set as an example for reaching a cost-neutral transition process. Among the strategies recommended to augment organic share in school food were reducing the amount of meat (e.g., by creating a one-meat-day-a-week menu), making long-term cooperations with regional suppliers (e.g., via direct selling contracts), integrating seasonal offers, and optimizing internal processes to reduce food waste. In another vein, the city of Freiburg decided recently to offer completely vegetarian menus for primary schools to allow a higher organic share and food quality (Interview N°15).

References

Ahmed, S. (2007). A phenomenology of whiteness. Femin Theory 8, 149–168. doi: 10.1177/1464700107078139

Alkon, A., and Norgaard, M. K. (2009). Breaking the food chains: an investigation of food justice activism. Sociol. Inq. 79, 289–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-682X.2009.00291.x

Augustin, H. (2020). Ernährung, Stadt und soziale Ungleichheit. Barrieren und Chancen für den Zugang zu Lebensmitteln in deutschen Städten. Bielefeld: transkript.

Baldy, J., and Kruse, S. (2020). Food democracy from the top down? State-driven participation for local food system transformations towards sustainability. Polit Govern 7, 68–80. doi: 10.17645/pag.v7i4.2089

Belina, B., and Michel, B. (2011). “Raumproduktionen” in Beiträge der Radical Geography. Eine Zwischenbilanz (Münster: Westfälisches Dampfboot)

Billo, E., and Hiemstra, N. (2013). Mediating messiness: expanding ideas of flexibility, reflexivity, and embodiment in fieldwork. Gend. Place Cult. 20, 313–328. doi: 10.1080/0966369x.2012.674929

Brand, U., and Wissen, C. (2017). Imperiale Lebensweise. Zur Ausbeutung von Mensch und Natur im globalen Kapitalismus. Oekom.

Brückner, M. (2023). Meal cartographies: using visual methods to explore geographies of food provisioning and care work. Feministische GeoRundMail 93, 24–30.

Campbell, H. (2009). Breaking new ground in food regime theory: corporate environmentalism, ecological feedbacks and the ‘food from somewhere’ regime? Agric. Hum. Values 26, 309–319. doi: 10.1007/s10460-009-9215-8

Coddington, K. (2017). Voice under scrutiny: feminist methods, anticolonial responses, and new methodological tools. Profess. Geogr. 69, 314–320. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2016.1208512

Crippa, M., Solazzo, E., Guizzardi, D., Monforti-Ferrario, F., Tubiello, F. N., and Leip, A. (2021). Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nat Food 2, 198–209. doi: 10.1038/s43016-021-00225-9

Elwood, S. (2015). Still deconstructing the map: microfinance mapping and the visual politics of intimate abstraction. Cartographica 50, 45–49. doi: 10.3138/carto.50.1.09

Faria, C. V., and Good, R. Z. (2015). Doing fieldwork research in Africa. African Geograph Rev 31, 63–66. doi: 10.1080/19376812.2012.679460

Friedmann, H. (2005). “From colonialism to green capitalism: social movements and emergence of food regimes” in New directions in the sociology of global development. eds. F. H. Buttel and P. McMichael (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 227–264.

Guthman, J. (2014). Doing justice to bodies? Reflections on food justice, race and biology. Antipode 46, 1153–1171. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.2012.01017.x

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: the science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Fem. Stud. 14, 575–599. doi: 10.2307/3178066

Hassanein, N. (2008). Locating food democracy: theoretical and practical ingredients. J Hunger Env Nutr 3, 286–308. doi: 10.1080/19320240802244215

Haynes-Conroy, J., and Haynes-Conroy, A. (2013). Veggies and visceralities: a political ecology of food and feeling. Emot. Space Soc. 6, 81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.emospa.2011.11.003

Helfrich, S., and Bollier, D. (2019). Frei, fair und lebendig—Die Macht der Commons. Bielefeld: Transcript.

Jansen, C. (2019). Essen an Schulen zwischen Anspruch und Wirklichkeit. Erwartungen an Schulverpflegung in Anbetracht von Erfahrungen aus der Praxis. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Kindon, S., Pain, R., and Kesby, M. (2007). Participatory action research approaches and methods: Connecting people, participation and place. London: Routledge.

Klosterkamp, S. (2023). “Story mapping” in Transformative Geographische Bildung. eds. E. Noethen and V. Schreiber (Heidelberg: Springer), 351–356.

Krüger, T., and Strüver, A. (2018). Narrative der ‚guten Ernährung‛: Ernährungsidentitäten und die Aneignung öffentlicher Nachhaltigkeitsdiskurse durch Konsument*innen. Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie 62, 217–232. doi: 10.1515/zfw-2017-0006

Kwan, M. (2002). Feminist visualization: re-envisioning GIS as a method in feminist geographic research. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 92, 645–661. doi: 10.1111/1467-8306.00309

McMichael, P. (2005). Global development and the corporate food regime. Res. Rural. Sociol. Dev. 11, 269–303. doi: 10.1016/S1057-1922(05)11010-5

Mendes, V. (2022). Teilhabe in Trümmern. Die Auflösung des Nationalen Ernährungsrates CONSEA in Brasilien. Berlin: FDCL.

Michel, S., Wiek, A., Boemertz, L., Bornemann, B., Granchamp, L., Villet, C., et al. (2022). Opportunities and challenges of food policy councils in pursuit of food system sustainability and food democracy – a comparative case study from the upper-Rhine region. Front Sustain Food Syst 6, 1–24. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2022.916178

Miewald, C., and McCann, E. (2014). Foodscapes and the geographies of poverty: sustenance, strategies, and politics in an urban neighborhood. Antipode 46, 537–556. doi: 10.1111/anti.12057

Morgan, K. (2015). Nourishing the city: the rise of the urban food question in the global north. Urban Stud. 52, 1379–1394. doi: 10.1177/0042098014534902

Motta, R. (2021). Social movements as agents of change: fighting intersectional food inequalities, building food as webs of life. Sociol. Rev. 69, 603–625. doi: 10.1177/00380261211009061

Nogueira, R. M., and Barone, B. (2022). “The national school food program in the interpretation of Brazilian managers” in School food, equity, and social justice. Critical reflections and perspectives. eds. D. Ruge, I. Torres, and D. Powell (New York: Routledge), 95–108.

Pavlovskaya, M. E. (2002). Mapping urban change and changing GIS: other views of economic restructuring. Gend. Place Cult. 9, 281–289. doi: 10.1080/0966369022000003897

Reese, A. (2019). Black food geographies. Race, self-reliance, and food access in Washington D.C. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Reese, A., and Garth, H. (2020). “Black food matters. An introduction” in Black food matters. Racial justice in the wake of food justice. eds. G. Garth and A. Reese (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press), 1–28.

Rockström, J., Edenhofer, O., Gaertner, J., and DeClerck, F. (2020). Planet-proofing the global food system. Nat Food 1, 3–5. doi: 10.1038/s43016-019-0010-4

Schanz, H., Pregernig, M., Baldy, J., Sipple, D., and Kruse, S. (2020). Kommunen gestalten Ernährung – Neue Handlungsfelder nachhaltiger Stadtentwicklung. Berlin: Deutscher Städte-und Gemeindebund.

Schermer, M. (2015). From “food from nowhere” to “food from Here:” changing producer–consumer relations in Austria. Agric. Hum. Values 32, 121–132. doi: 10.1007/s10460-014-9529-z

Shannon, J. (2014). Food deserts: governing obesity in the neoliberal city. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 38, 248–266. doi: 10.1177/0309132513484378

Sieveking, A. (2019). Food policy councils as loci for practising food democracy? Insights from the case of Oldenburg, Germany. Polit Govern 7, 48–58. doi: 10.17645/pag.v7i4.2081

Sipple, D., and Wiek, A. (2023). Kommunale Instrumente für die nachhaltige Ernährungswirtschaft. Freiburg: Institut für Umweltsozial-wissenschaften und Geographie.

Speck, M., Wagner, L., Buchborn, F., Steinmeier, F., Friedrich, S., and Langen, N. (2022). How public catering accelerates sustainability: a German case study. Sustain. Sci. 17, 2287–2299. doi: 10.1007/s11625-022-01183-2

Stein, M., Hunter, D., Swensson, L., Schneider, S., and Tartanac, F. (2022). Public Food Procurement: A Transformative Instrument for Sustainable Food Systems. Sustainability 14:6766. doi: 10.3390/su14116766

Tornaghi, C. (2017). Urban agriculture in the food-disabling city: (re)defining urban food justice, reimaging a politics of empowerment. Antipode 49, 781–801. doi: 10.1111/anti.12291

Tronto, J. (1993). Moral boundaries. A political argument for an ethic of care. New York/London: Routledge.

Vivero-Pol, J. L. (2019). “The idea of food as a commons: multiple understandings for multiple dimensions of food,” in Routledge handbook of food as a commons, ed. J. L. Vivero Pol, T. Ferrando, O. SchutterDe, and U. Mattei (New York: Routledge), 25–41.

Wang, K. (2021). Reimagining the global food regimes for relational spaces. Area 53, 637–646. doi: 10.1111/area.12714

WBAE (Scientific advisory board on agricultural policy, food and consumer health protection) (2023). Ernährungsarmut unter Pandemiebedingungen. Berlin: WBAE. Available at: https://www.bmel.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/DE/2023/032-wbae-ernaehrungsarmut-pandemie.html (Accessed 07 October 2023).

Welsh, J., and MacRae, R. (1998). Food citizenship and community food security: lessons from Toronto, Canada. Can J Dev Stud 19, 237–255. doi: 10.1080/02255189.1998.9669786

Whitesell, D. K., and Faria, C. V. (2020). Gowns, globalization, and “global intimate mapping”: geovisualizing Uganda’s wedding industry. Environ Plann C Polit Space 38, 1275–1290. doi: 10.1177/2399654418821133

Winker, G., and Degele, N. (2011). Intersectionality as multi-level analysis: dealing with social inequality. Eur. J. Women's Stud. 18, 51–66. doi: 10.1177/1350506810386084

Appendix

List of interviews and workshops

1. 11 October 2021, director, producer association, Rebio Rottenburg

2. 11 November 2021, scientist, University of Applied Forest Sciences Rottenburg

3. 17 March 2022, consultant, consultancy agency, Öko-Konsult Stuttgart

4. 25 March 2022, employee, project “Bio für Kinder,” Tollwood mbH München

5. 1 July 2022, director, kitchen management, Rottenburg

6. 1 July 2022, management, producers cooperative, Xäls Tübingen

7. 13 July 2022, activist, food policy council, Freiburg

8. 15 September 2022, activist, parents’ association, Tübingen

9. 16 September 2022, employee project management, Biosphärengebiet Schwäbische Alb

10. 22 September 2022, pupil, Tübingen

11. 23 September 2022, pupil, Tübingen

12. 1 October 2022, teacher, Tübingen

13. 5 October 2022, pupil, Tübingen

14. 13 October 2022, employee city administration, Mannheim

15. 20 October 2022, employee city administration, Freiburg

16. 21 October 2022, cook, kitchen administration Tübingen

17. 22 October 2022, pupil, Tübingen

18. 11 March 2023, workshop, Food Policy Council activists, Cologne

Keywords: food justice, Food Policy Councils, social inequalities, public catering, urban food systems, feminist mapping, participatory action research

Citation: Hoinle B and Klosterkamp S (2023) Food justice in public-catering places: mapping social-ecological inequalities in the urban food systems. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7:1085494. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2023.1085494

Edited by:

Andreas Mayer, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna, AustriaCopyright © 2023 Hoinle and Klosterkamp. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Birgit Hoinle, YmlyZ2l0LmhvaW5sZUB1bmkuaG9oZW5oZWltLmRl

Birgit Hoinle

Birgit Hoinle Sarah Klosterkamp2

Sarah Klosterkamp2