95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Food Syst. , 31 March 2023

Sec. Nutrition and Sustainable Diets

Volume 7 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2023.1083660

This article is part of the Research Topic Role of Multi-Sector Research and Development Approach in Promoting Sustainable Healthier Diets View all 6 articles

The objective of the study was to compare agricultural investment and agricultural production of rural agrarian women in Uganda that had received microcredit to those that had not. A quasi-experimental was used to assess differences between performance indicators of agricultural enterprises for existing and incoming borrowers of Bangladesh Rural and Advancement Committee (BRAC) microfinance. Propensity score matching was used to ensure the comparability of the groups and to assess differences between existing borrowers and in-coming borrowers, before they received their first loan. Results indicated that the major reason for borrowing was education of children. There was no difference in investment in agricultural production between the study groups. The existing borrowers had lower monetary value of all harvested crops and for maize and beans than the in-coming borrowers. Total number of animals owned, types of animals kept and reported monetary value for goats and local cattle were also less for existing borrowers than for in-coming borrowers. It was observed that the loan repayment protocols did not match income from agriculture. The results reveal a need to modify loan repayment protocols to address the latent period between agricultural investment and output.

According to the World Bank (2007), three out of every four people in developing countries live in rural areas and mostly depend on agriculture for their livelihood. Agriculture contributes significantly to the national gross domestic product (GDP) and has potential to be an instrument for sustainable development and poverty reduction (Wang et al., 2019). Despite the importance of agriculture, agrarian communities in the least-developed countries still suffer from cyclic food shortages because of fluctuations in production and in food prices (Morvant-Roux, 2011). The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), reported that unfavorable climate conditions aggravate agricultural production problems in different parts of the world leading to persisting food insecurity challenges (FAO, 2016; World Bank, 2016). Food insecurity is prevalent in rural areas in Uganda and has been associated with monetary poverty (UBOS and WFP, 2013).

Given the importance of agriculture in poverty reduction and development, national and international organizations have established programs geared toward agricultural production improvement with focus on transformation from subsistence to commercial agriculture as prerequisites for economic development (World Bank, 2007; Diao et al., 2010). The opportunities these programs present to addressing Sustainable Development Goals that focus on food security improvement need to be understood (FAO, 2021). This study aimed to evaluate the potential role of microcredit in this transformation for resource-poor rural women, involved in agricultural production. According to the Uganda Annual Agriculture Survey of 2018, agriculture ranked first in terms of labor force participation in the Uganda economy with ~7.4 million households operating in agriculture. About 80% of the agricultural households engaged in crop and livestock production both for own consumption and for income generation. The higher proportion of these (89%) were women than men (79%) UBOS (2020). In 2022, the Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing sector contributed 24.1% to Uganda's GDP and 33% of export earnings in the financial year 2021/2022 (UBOS, 2022).

The strategic direction of Uganda's Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries (MAAIF), includes transformation of subsistence farmers into enterprise farmers. These programs entail, among others, activities aimed at improvement of agricultural production and productivity, increasing access to farm inputs, and improving agricultural markets. Rural infrastructure development, provision of extension services, dissemination of weather information and promotion of improved production practices and crop varieties are some of the activities undertaken by the government (UBOS, 2016).

Food security may be improved through increasing access to financial services (Meyer, 2013; Gyasi et al., 2020), because lack of financing and poorly functioning financial markets limit farmers' capacity to invest in new practices and improved technologies (FAO, 2011). Microenterprise finance through provision of microcredit is highly regarded by development agencies and non-governmental organizations as a tool for poverty alleviation in low-income communities (Hulme, 2000; Armendáriz and Morduch, 2010; Armendáriz and Labie, 2011). Investment of microcredit in agriculture is expected to improve input expenditures and subsequent agricultural output (Morvant-Roux, 2011). MoFPED (2014), UBOS (2014) reported an increase in microfinance activities in Uganda. However, microfinance institutions offering loans for agriculture are few because of the riskiness of agricultural production, and the time lag between investment and agricultural output that often does not favor their schedules of loan repayment. And yet, many of their clients in rural and agrarian communities tend to be involved in agricultural production. In addition, some forms of support to agricultural producers may not have the desired effect (FAO, 2021).

There is, however, limited literature about the extent to which microcredit recipients invest microloans in agricultural production, and whether such investments in agriculture translate into production output increase. The effect of borrowing on income is also still a subject of debate (Banerjee, 2013; Banerjee et al., 2015).

The current study sought to assess the extent to which borrowing affects expenditure on and output from agricultural production. The study focused on females because of their high representation in agricultural production and among the Bangladesh Rural and Advancement Committee microfinance microcredit (BRAC) program clientele.

The study followed a quasi-experimental cross-sectional design with existing borrowers and incoming borrowers of BRAC microfinance from Buikwe and Mukono districts of Uganda as the respondents. Choice of the two districts was based on the fact that BRAC microcredit program was enrolling new clients at the time of the study and that the microcredit program in the districts covered female agrarian clients. Respondents for this study were drawn from a bigger sample of 533 (312 current borrowers and 221 incoming borrowers) women enrolled onto the BRAC microcredit program in the two districts. The 244 (173 current borrowers and 71 incoming borrowers) clients included in this study were those that indicated that they practiced agriculture as a business, i.e., invested in crop and animal production with the aim of selling their produce for income. The participants in the two groups had to fulfill the criteria specified in Table 1.

Tables 2, 3 provide summary of the quantitative and qualitative data collected in the study.

To assess the level of commercialization of agricultural production, “business-like scores” were constructed for crop and animal production. These scores were based on inputs of production in order to assess whether the crop and animal activities of the respondents qualified as business-like. For crop production, a crop business-like score was computed as summation of positive responses to four questions eliciting information on (1) Having employees in crop production; (2) Payments for farm laborers in crop production; (3) Seed purchase; (4) Purchase of fertilizers and/or pesticides. The maximum crop business-like score thus equalled 4. The animal business-like score on the other hand was the summation of positive responses to the following questions: (1) Payment for veterinary support; (2) Animal feeds purchase; (3) Payments for hired farm labor. The maximum animal business-like score thus equalled 3. This information was used to assess the degree of commercialization of production activities.

For crop producers, data on a self-reported measure of area under crop production, change in area under cultivation after accessing credit, time allocation to garden work, both on days when the respondent conducted non-farm micro-enterprise (ME) activities and on days with no non-farm ME activity, were obtained.

To capture the effect of microcredit on output for crop-related agriculture, output of crop production was obtained and used to calculate the monetary value of crop harvest, as the product of the quantity of different crops produced and the unit market price of respective crop items at the time of the study. For animal-related MEs an animal-wealth variable was calculated as the product of the numbers of different types of animals and unit market price of the animal type at the time of the study. For crop and animal production, total crop production input expenditures and cost of animal production were computed, respectively.

The personality variables concerning risk preference, time preference, and achievement motivation were calculated as the means of the respective answers to the scale items. Since the answers were given on a scale from 1 (agree strongly) to 4 (disagree strongly), the interpretation of the scale is reversed. For example, a high score on the risk preference variable indicates low risk preference.

Three focus group discussions (FGDs), consisting of 8–15 participants, were conducted for each group (existing borrowers and incoming borrowers) to obtain in-depth understanding of the reasons for borrowing, investments made with borrowed funds, loan payment dynamics, views on suitability of microcredit loans for agricultural investments and extent to which borrowing affected investments into agriculture.

Information about the BRAC microcredit program was obtained from focus group discussions with the borrowers and from key-informant interviews with BRAC loan officers, branch managers and the area manager. Some information was obtained from loan sheets that were accessible and meetings attended to understand more about the program operations.

We cross-checked and ensured comparability of the existing borrowers and incoming borrowers groups by use of the Propensity Score Matching (PSM) methodology. Factors which could influence self-selection into microcredit and those which could influence microcredit outcomes were used as control variables in the PSM procedure, with weighted Kernel matching (Luellen et al., 2005). These factors included respondent background characteristics that included religion, marital status, age, years of education, time preference, and risk preference and achievement motivation. In order to compare with the incoming, borrowers, all age-related variables of existing borrowers were converted to the age basis at the time of their first loan, indicated as “corrected age”, “corrected family size” and “corrected dependency ratio” hereafter. Principal components analysis was used to check the dimensionality of the personality characteristics. In this analysis, only the time preference items were found to have a single factor in common, hence the average item scores were used as a measure of time preference, or impatience. The need for achievement and risk preference items were not explained from common factors, so we used the individual item scores in this procedure. The control variables were used to construct propensity scores estimating the probability of being in the comparison or treatment group. The PSM procedure was also used to estimate the effect of receiving microcredit. The rationale of this procedure is to match the participants in the treatment group to those in the comparison group based on propensity scores. Therefore any remaining differences observed can be attributed to the treatment.

Propensity scores were used to estimate the probability of being in the control (incoming borrowers) or treatment (existing borrower) group. They were also used to estimate the effect of receiving microcredit. Participants were matched in the different groups based on propensity scores. Remaining observed differences were then attributed to the treatment. The average treatment effect on the treated (τATT) was defined as per the equation.

Where D = 1 if respondent had a running loan and D = 0 when they belonged to the incoming category. Y (D) denotes the outcome variable of each participant (for example monetary value of the harvest) while [Y (0) |D = 1] is counterfactual and unobservable. According to Rosenbaum (2010) τATT can be expressed as:

Where P(X) is the propensity score, that is, the probability of an individual to participate in the microcredit program given the observed characteristics.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis as described by Rosenbaum (2010). We did this for the main monetary value of harvest and found that unobservable covariates would need to change the odds of treatment assignment by factors beyond 3 to conclude that the observed treatment effects from propensity score matching were due to non-random assignment. We concluded that our PSM results were unlikely to be influenced by unobservable attributes of the clients.

The microcredit program was found to target poor women (aged 20–50 years) with stable businesses to enhance the performance of their self-employment activities (agricultural or non-farm microenterprises). Individual loans were given to women who belonged to a village organization which comprised 20 women on average. Loan applications are guaranteed by every member of the group. Loan amounts were also agreed upon unanimously and authorized microloans disbursed in cash to individual women, at the branch.

At the time of the study, the borrowers in the existing borrowers group, had on average received credit three times. The mean amount of the first loan was UGX 358,414 ($138), while the average amount of running loans was Uganda shillings (UGX) 725,000 ($278). The average number of weeks since receiving the last and first loan for the respondents was 20 and 97, respectively.

Loans were repayable in either 20 or 40 equal weekly installments, at flat interest rates of 12% and 25%, respectively. The installments were paid at weekly meetings with repayments commencing 1 week following the receipt of the loan. No grace period was given between receiving the loan and payment of the first installment. In case of inability to pay, women before the meeting day would mobilize funds toward repayment from each member. In case of a member's failure to pay, the group chairperson and credit officer urged members to cover the payment by pooling funds. Group meetings were not to be dispersed until all funds had been collected, counted and verified in front of all women. When members failed or refused to raise the funds for a defaulter, the loan guarantor would be contacted. If this failed as well, the credit officer reluctantly allowed the meeting to disperse and she would then continue to seek the guarantor. In cases where the loan officer concluded that a defaulting client was unable to continue making her weekly repayments, her loan guarantor was required to repay the loan in one installment or weekly payments until the full amount was paid up. In extreme cases, property of the borrower (usually a business or household asset) or of the guarantor was confiscated.

There was strict observance of village organizations meeting routines and credit officers and branch managers reported good repayment records mainly for the initial loans. Repayment difficulties were reported with larger loans for successive loan cycles when weekly repayment amounts commensurately increased.

The majority of current (53%) and in-coming (66%) borrowers were involved in both crop and animal production. The remaining, 47% and 34% respectively for current and in-coming borrowers, practiced either crop or animal production.

The socio-demographic and personality characteristics of the clients with agricultural-related microenterprises in the study for existing and incoming borrowers were similar on the control variables, both before and after propensity score matching. The similarity of the groups before matching seemed to be an outcome of the two groups having self-selected to participate in the BRAC microcredit program. Clients that participated in the study were on average 35 years of age, with 7 years of primary education. The dependency ratio was 1.4, which was slightly higher than the national average of 1.2. The majority (75%) were married. Risk preference was 2.2 on average (on the 4-point agree–disagree scale), indicating that most respondents were risk neutral and most had a relatively low time preference score (3.3 on average on the agree–disagree scale), implying they possessed the ability to delay gratification to the future. The clients had a high achievement motivation score (1.0 on average on the agree–disagree scale), implying they agreed on questions eliciting respondent aspirations to improve their lives.

A quarter (25%) of clients though declaring that they performed agriculture as a business stated that they did not deploy any basic production inputs of crop production that would make production more profitable, even after accessing credit. They never hired labor, purchased improved seeds nor used fertilizers in the season before the study. The remaining percentage (75%) either hired labor, purchased improved seeds or used fertilizers the season before the study, and with minimal inputs into the same.

The commercial crop diversity for clients in the study was two (2), with maize and beans being planted by more than half of the existing borrowers.

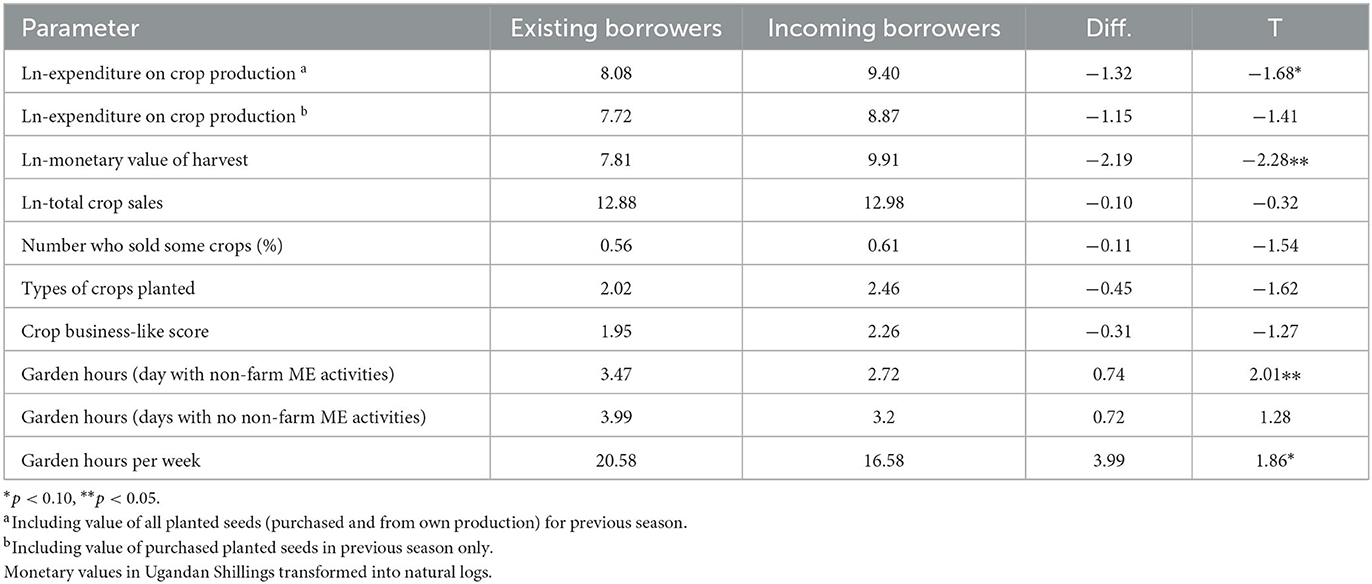

Tables 4, 5 shows differences between the study groups regarding basic crop and animal production parameters and practices, investments in crop production, and expected outcomes of borrowing on crop production. These differences can be considered as average treatment effects on the treated (ATT) based on probability score matching with Kernel matching.

Table 4. Differences between existing borrowers and incoming borrowers agricultural production parameters.

Table 5. Differences in monetary values (In Uganda shillings) of individual crop harvests (in logarithms) between existing and in-coming borrowers.

Results revealed no evidence of improvement in commercialization of crop production after borrowing. This was revealed by the lack of differences between study groups on the number of planted crops, number who sold some crop in the previous season, and on the monetary value of crop sales (Table 4).

Existing borrowers spent less than in-coming borrowers on crop input expenditures (such as on purchase of seeds for planting), with both groups spending less than the equivalent of US$ 100 on crop production inputs in the cropping season before the study. It was therefore not surprising that the monetary value of the whole crop harvest (the product quantity of respectively crop harvest times the unit market price at the time of the study)

Although not significant, results revealed a negative trend in number of borrowers who sold some crops from the previous season, the number of different types of crops planted, and the crop business-like score for borrowers. However, responses to the inquiry about change in amount of time spent on garden-related activities after borrowing indicated that 44% of existing borrowers spent the same amount of time, 33% spent less time, while 23% increased the amount of time.

The results of the quantitative survey were confirmed by the qualitative focus group discussions. The following reasons for borrowing, in order of frequency of occurrence, were mentioned: (1) pay children's school fees; (2) recapitalise non-farm microenterprises; (3) personal development; (4) household welfare and improvement; (6) crop farming; (7) animal husbandry; (8) start a new business. Borrowing to purchase crop production and animal inputs was ranked 6th and 7th, respectively out of eight reasons to borrow. The FGDs provided more insights into the reasons for limited investment in crop production. Some clients, for example, argued that they had access to small pieces of land for crop growing, limiting the worth of investment in crop production. Clients also argued that high risk associated with crop production made it unattractive for investment of loan funds. Focus group discussion participants also observed that investment in agriculture did not suit the BRAC weekly loan repayment requirements. One participant commented: “You have to make weekly loan repayments from the very week you receive the loan. If you invest in agriculture and have no trade business, you will have difficulties”.

The most important crops for the clients based on monetary value of the harvest were maize, beans, sweet potatoes, and cassava (Table 5). The monetary values for maize and beans for existing borrowers were, respectively, two per cent point and almost three percent point lower than that for incoming borrowers. On the other hand, the monetary value of harvested eggplant and tomatoes for incoming borrowers were, respectively, 0.4 percent point and 0.36 percent point higher than for existing borrowers. Maize and beans may be the drivers of the negative shift in monetary harvest value. Borrowers may have reduced the production of some of their crops, possibly because of loan repayment challenges and other reasons discussed above. Another challenge clients reported for their limited enthusiasm in investing borrowed funds in crop production was poor markets. Some observed that in times of good harvest, they failed to sell off crops like cassava and sweet potatoes, because of poor markets. They revealed that part of the harvested produce was consumed by the household and the excess used to feed pigs or left to rot in the gardens. This type of market failure may discourage additional investments in production of such crops.

Quantitative results revealed that one-third of the women with agriculture-related MEs, had non-farm microenterprise, with self-reported net worth of <$50. Cash collections from these small businesses were pooled with the proceeds from sale of crops and used to make weekly loan repayments.

Results indicate that pigs were the most kept animal type. Fewer existing borrowers than in-coming borrowers owned goats, local cattle and local chicken (Table 6). Although we did not find quantitative evidence of the effect of borrowing on pig production, focus group discussions participants indicated that they used loan funds to purchase pigs. They indicated that the preference for keeping pigs was due to their short life cycle and the possibility of selling them readily to meet urgent household needs, and to provide capital for failing microenterprises.

Borrowing did not translate into commercialization of animal production among borrowers. This is evidenced by the similarity in the business-like score (animal production) between the study groups. Apart from the increase in exotic chicken production among borrowers, borrowing seemed to have a negative effect on animal wealth as depicted by lower monetary worth of some types of animals and numbers of different types of animals owned for existing borrowers (Table 6).

Majority of the clients (78% of existing borrowers and 84% of incoming borrowers) kept at least one type of animal. There was no statistical difference between numbers of existing borrowers and incoming borrowers, who kept animals. Borrowing seemed to have a negative effect on animal production according to the probability score matching method, with Kernel matching (Table 7). Existing borrowers spent less than new borrowers on animal production inputs, kept smaller numbers of animals, and they had a lower monetary value of kept goats and local cattle. However, the total animal wealth for both groups did not differ (see Table 7).

Contrary to the common assertion that credit is a major limiting factor to improvement in agricultural production, and that borrowing will lead to improvement in investment in agricultural production and output (Armendáriz and Labie, 2011; FAO, 2016), we tested and rejected the hypothesis of microcredit leading to improvement in recurrent agricultural input expenditures and in crop and animal output after borrowing. Microcredit did not translate into commercialization of crop and animal production among borrowers and seemed to have a negative effect on animal wealth.

Our findings of this study are contrary to observations made by some authors. For example Kaboski and Townsend (2012) reported improvement in agricultural investment after borrowing, Denis et al. (2021) reported positive changes in productivity of smallholder farmers after borrowing and Crépon et al. (2015), observed increase in the scale of livestock and non-livestock agriculture activities. Chan and Ghani (2011) reported increased investment in rural enterprises and improvement in income of remote area dwellers after borrowing. Our findings are in agreement with findings by Matin et al. (2002) and Yuko and Eustadius (2020). These reported no change in the hire of labor, utilization of improved technology and fertiliser's inputs, by farmers after borrowing. Our findings also agree with UBOS' observation (UBOS, 2010) that only 7% and 3% of the people in Uganda borrow to buy farm inputs, that is seeds and livestock, respectively. And with Grimpe (2002) who observed that FINCA Uganda clients used loans to cater for short-term livelihood needs rather than development in agriculture.

The findings raise questions of why the borrowers did not increase recurrent expenditures in agricultural production or take up improved technologies. The possible explanations as to why borrowers did not invest microloans in agricultural activities may be found in the nature of the borrowers and their agricultural activities, the local market conditions for agricultural produce and the requirements of the microfinance institution (MFI) protocols for loan repayment. These are described below.

The characteristics of the women and the agricultural activities they were involved in may explain why borrowers did not invest more in agricultural production, after borrowing. Individual characteristics, skills and abilities (Cheston and Kuhn, 2002; Gifford, 2004) such as level of schooling (Reza et al., 2020), age and marital status (Van Rooyen et al., 2012) have been reported to influence the success of women-run economic ventures. In addition, livelihood assets and resources of the loan recipients may moderate levels of outcome of microcredit participation.

The clients in this study seem to fit well the definition of peasants by Ellis (1993, p. 13), as “households that derive their livelihoods mainly from agriculture, utilize mainly farm labor in farm production, and are characterized by partial engagement in input and output markets which are often imperfect or incomplete”. This definition appropriately characterizes the women in the study. Peasant households in Uganda have been reported to have poverty prevalence levels as high as 38% (UBOS, 2018). The peasant and subsistence nature of the respondent's agricultural activities as depicted by the low levels of investment in crop and animal production, may have limited the potential for commercialization even after borrowing. As observed, current and incoming borrowers used dismal levels of inputs and technology in their production activities. About 40% of both existing and incoming borrowers did not sell any crop produce, meaning all harvest was used for own consumption.

Although we found women in our study to be risk neutral, women are generally regarded as being risk averse and unlikely to invest their loans when they perceive the possibility of failure in an activity (Fletschner et al., 2010). Being risk averse, poor households are unlikely to take up risky ventures (Gloede et al., 2015), like crop production, whose outcome depends on unpredictable weather patterns and existing soil conditions (Morvant-Roux, 2011). This is one of the explanations offered by Banerjee (2013), as to why poor borrowers may not invest microloans in agricultural production.

Focus group discussion results revealed that borrowers were cautious while allocating loans to agricultural production, because of unpredictable weather patterns that make agricultural production risky. Crop failure could easily lead to loan repayment problems.

Matin et al. (2002), observed that the borrowing terms for the poor need to be context specific. The socio-economic environment within which the women operated may also thus have disfavoured investment of borrowed funds into farming. Many rural area dwellers in Uganda are resource poor (UBOS, 2018), and operate in an environment of poorly developed markets and infrastructure. Such conditions of poor infrastructure and imperfect markets pose a risk to income and consumption and may discourage agricultural investment (Diagne and Zeller, 2001). Lack of markets for agriculture produce (Morduch, 1995), and overgrown crops in gardens because of this, were reported by the women in the study. Authors like Adams and Von Pischke (2001) have argued that credit may not be as large a problem for agricultural smallholders. Price and other production risks are key factors that may hinder the poor from enhancing their economic condition, even when they borrow.

Another factor that may have hindered commercialization of agriculture after borrowing, are gender specific constraints as reported by Lakwo (2006) and Wakoko (2004), which abound in Uganda. Examples of these are lack of land and land ownership rights, limited access to agricultural knowledge and information, the difficulties in balancing production and reproduction roles. These entrap women to mainly engage in food provision for their households, and not in more lucrative cash crop production.

The microfinance protocol for loan repayment as observed by Mutesasira and Kaffu (2003), Nanayakkara and Stewart (2015) may also explain some of our results. The observed BRAC loan protocol is an institutionalist approach as described by Khan et al. (2017). This protocol places emphasis on security and profitability of loan repayments, with weekly loan repayments that commence the week after loan disbursement. This poses a mismatch with borrowers who focus on agricultural production, as a source of funds for loan repayment (Namayengo et al., 2016; Namayengo, 2017). As a result, the borrowers maybe shifting away from crop and animal production, which have a long lag phase between investment and output, and instead opt for non-farm activities with shorter gestation periods.

One explanation for lack of improvement in animal production after borrowing was the conversion of animals into cash, to obtain funds for loan repayment. From the focus group discussions, women reported that they sell off whatever is saleable to get funds for loan repayment.

Our results reveal that current borrowers had lower investment in agricultural inputs and recorded lower agricultural production than in-coming borrowers. Borrowers generally did not invest borrowed money into agriculture, possibly because of the high risk associated with agriculture and the mismatch between timing of loan repayment and anticipated income from agriculture. With the current MFI protocols, microcredit is therefore unlikely to lead to growth in agricultural production and may negatively affect food security. To enhance MFI's contribution to economic improvement of poor agrarian communities, there is therefore need to review loan terms and processes to take into account the lag between agricultural investment and income as well to cater for the risk associated with agricultural production.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants to participate in the study.

FN worked on the concept development, data collection and analysis, and manuscript drafting and review. GA contributed to concept development, data analysis including the propensity score matching methodology, and manuscript review. JvO made contribution on concept development, data analysis, and manuscript review. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the NUFFIC Netherlands fellowship program [grant number: CF8560/2012].

We would like to acknowledge the financial support of the NUFFIC Netherlands Fellowship Program that covered all research related expenditures for the study. This work is part of a PhD study entitled: Namayengo (2017). Microcredit to women and its contribution to production and household food security. PhD thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, the Netherlands (2017). ISBN: 978-94-6343-110-1. doi: 10.18174/407189 We are also grateful to the research office of BRAC Uganda, who allowed us to work with the communities and the women whom they serve. Special thanks go to the loan officers who enabled us to access the respondents for the study, the women under the different village organizations, who patiently responded to the to the study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

BRAC, Bangladesh Rural and Advancement Committee; PSM, Propensity Score Matching.

Adams, D. W., and Von Pischke, J. (2001). Microenterprise credit programs: Deja vu. World Dev. 20, 1463–1470. doi: 10.1016/0305-750X(92)90066-5

Armendáriz, B., and Labie, M. (2011). Handbook of Microfinance. New Jersey, NJ: World Scientific. doi: 10.1142/7645

Armendáriz, B., and Morduch, J. (2010). The Economics of Microfinance. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. doi: 10.2307/20111887

Banerjee, A., Karlan, D., and Zinman, J. (2015). Six randomized evaluations of microcredit: introduction and further steps. Am. Econ. J. 7, 1–21. doi: 10.1257/app.20140287

Banerjee, A. V. (2013). Microcredit under the microscope: what have we learned in the past two decades, and what do we need to know? Ann. Rev. Econ. 5, 487–519. doi: 10.1146/annurev-economics-082912-110220

Blais, A.R., and Weber, E. U. (2006). A domain-specific risk-taking (DOSPERT) scale for adult populations. Judg. Decis. Mak. 1, 33–47. doi: 10.1017/S1930297500000334

Chan, S. H., and Ghani, M. A. (2011). The impact of microloans in vulnerable remote areas: evidence from Malaysia. Asia Pacific Business Rev. 17, 45–66. doi: 10.1080/13602380903495621

Cheston, S., and Kuhn, L. (2002). Empowering women through microfinance. Draft, Opportunity Int. 64, 1–64.

Crépon, B., Devoto, F., Duflo, E., and Pariente, W. (2015). Estimating the impact of microcredit on those who take it up: evidence from a randomized experiment in Morocco. Am. Econ. J. 7, 123–150. doi: 10.1257/app.20130535

Denis, A. H., Godefroy, G. G., and Melain, M. S. (2021). Access to finance and difference in family farm productivity in Benin: evidence from small farms. Sci. African. 13, e00940. doi: 10.1016/j.sciaf.2021.e00940

Diagne, A., and Zeller, M. (2001). Access to Credit and its Impact on Welfare in Malawi, 116. Washington: IFPRI.

Diao, X., Hazell, P., and Thurlow, J. (2010). The role of agriculture in African development. World Dev. 38, 1375–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.06.011

Ellis, F. (1993). Peasant Economics: Farm Households and Agrarian Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

FAO (2011). The State of Agriculture and Food (2010-2011). Closing the Gender Gap for Development. Available online at: http://www.fao.org/. (accessed 20 October, 2016).

FAO (2016). “The state of food and agriculture,” in Climate change, agriculture and food security. Rome: FAO. Available online at http://reliefweb (accessed 12 November, 2016).

FAO (2021). The State of Food and Agriculture 2021. Making Agrifood Systems More Resilient to Shocks and Stresses. Rome: FAO. doi: 10.4060/cb4476en

Fletschner, D., Anderson, C. L., and Cullen, A. (2010). Are women as likely to take risks and compete? Behavioural findings from Central Vietnam. J. Dev. Stud. 46, 1459–1479. doi: 10.1080/00220381003706510

Gifford, J. (2004). Utilizing, Accumulating, and Protecting Livelihood Assets: The Role of Urban Informal Financial Services in Kampala, Uganda. Delft: Eburon Academic Publishers.

Gloede, O., Menkhoff, L., and Waibel, H. (2015). Shocks, individual risk attitude, and vulnerability to poverty among rural households in Thailand and Vietnam. World Dev. 71, 54–78. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.11.005

Grimpe, B. (2002). Rural microfinance clients in Uganda: FINCA client analysis. FSD series No.6. Financial System Development Project 2002. Available online at: http://www.microfinancegateway.org/ (accessed 31 March, 2015).

Gyasi, R. M., Phillips, D. R., and Adam, A. M. (2020). How far is inclusivity of financial services associated with food insecurity in later life? Implications for health policy and sustainable development goals. J. Appl. Gerontol. 40, 189–200. doi: 10.1177/0733464820907441

Hulme, D. (2000). Is microdebt good for poor people? A note on the dark side of Microfinance. Small Enterprise Dev. 11, 26–28. doi: 10.3362/0957-1329.2000.006

Kaboski, J. P., and Townsend, R. M. (2012). The impact of credit on village economies. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 4, 98–133. doi: 10.1257/app.4.2.98

Keinan, A., and Kivetz, R. (2011). Productivity orientation and the consumption of collectable experiences. J. Consum. Res. 37, 935–950. doi: 10.1086/657163

Khan, W., Shaorong, S., and Ullah, I. (2017). Doing business with the poor: the rules and impact of the microfinance institutions. Econ. Res.-EkonomskaIstraŽivanja. 30, 951–963. doi: 10.1080/1331677X.2017.1314790

Lakwo, A. (2006). Microfinance, rural livelihoods, and womens empowerment in Uganda. (Ph.D Thesis). Nijmegen: Radboud Universiteit (African Studies Centre Research report no 85.)

Luellen, J. K., Shadish, W. R., and Clark, M. (2005). Propensity scores. An introduction and experimental test. Evaluat. Rev. 29, 530–558. doi: 10.1177/0193841X05275596

Matin, I., Hulme, D., and Rutherford, S. (2002). Finance for the poor: from microcredit to micro financial services. J. Int. Dev. 14, 273–294. doi: 10.1002/jid.874

Meyer, R. L. (2013). “Microcredit and agriculture: Challenges, successes and prospects,” in Microfinance in developing countries: issues, policies and performance evaluation, Gueyie, J. R., and Yaron, J. M. (eds.). (pp. 199-226). London: Palgrave Macmillan, London. doi: 10.1057/9781137301925_10

MoFPED (2014). Poverty status report 2014. Structural change and poverty reduction in Uganda. https://www.tralac.org/news/article/6878-poverty-status-report-2014-structural-change-and-poverty-reduction-in-uganda.html (accessed 1 December, 2016).

Morduch, J. (1995). Income smoothing and consumption smoothing. J. Econ. Persp. 9, 103–114. doi: 10.1257/jep.9.3.103

Morvant-Roux, S. (2011). “Is microfinance the adequate tool to finance agriculture?,” in The handbook of microfinance, Armendáriz, B., and Labie, M. (eds.). London: World Scientific. p. 421–435. doi: 10.1142/9789814295666_0020

Mutesasira, L., and Kaffu, E. (2003). Competition working for customer: The evolution of the Ugandan microfinance sector: A longitudinal study from December 2001 to March 2003. Kampala: MicroSave-Market-led solutions for financial services, Nairobi, Kenya. Available online at: http://www.microsave.net/files/pdf/Competition_Working_for_Customers_The_Evolution_of_the_Uganda_MicroFinance_Sector_A_Longitudinal_Study_from_December_2001_to_March_2003.pdf (accessed March 15, 2023).

Namayengo, F. M. M. (2017). Microcredit to Women and its Contribution to Production and Household Food Security. PhD Thesis. Wageningen, the Netherlands: Wageningen University. (2017).

Namayengo, F. M. M., Antonides, G., and Van Ophem, J. (2016). Women and microcredit in rural agrarian households of Uganda: match or mismatch between lender and borrower? APSTRACT. 10, 77–88. doi: 10.19041/APSTRACT/2016/2-3/9

Nanayakkara, G., and Stewart, J. (2015). Gender and other repayment determinants of micro financing in Indonesia and Sri Lanka. Int. J. Social Econ. 42. 322–339. doi: 10.1108/IJSE-10-2013-0216

Petrocelli, J.V. (2003). Factor validation of the consideration of future consequences scale: Evidence for a short version. J. Soc. Psychol. 143, 405–413. doi: 10.1080/00224540309598453

Ray, J. J. (1980). The comparative validity of Likert, projective, and forced-choice indices of achievement motivation. J. Soc. Psychol. 111, 63–72. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1980.9924273

Reza, M., Manurung, D., Kolmakov, V., and Alshebami, A. (2020). Impact of education and training on performance of women entrepreneurs in Indonesia: Moderating effect of personal characteristics. Manag. Sci. Lett. 10, 3923–3930. doi: 10.5267/j.msl.2020.7.018

Rosenbaum, P. R. (2010). Design of observational studies (Vol 10) (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1213-8

UBOS (2010). Uganda National Household Survey 2009/2010. Socio-economic Module. Abridged Report. Kampala: UBOS. Available online at: http://www.ubos.org/ (accessed 1 December, 2016).

UBOS (2014). Uganda National Household Survey 2012/2013. Kampala Uganda. Available online at: http://www.ubos.org/. (accessed 5 December, 2015).

UBOS (2016). National Population and Housing Census 2014. Main report. Kampala Uganda. Available online at: http://www.ubos.org/. (accessed 1 December, 2016).

UBOS (2018). Uganda National Household Survey 2016/2017. Kampala Uganda: UBOS. Available online at: https://www.ubos.org/wp-content/uploads/publications/03_20182016_UNHS_FINAL_REPORT.pdf (accessed 25 May, 2020).

UBOS (2020). The Annual Agriculture Survey 2018 Statistical Release. Available online at: http://www.ubos.org/. (accessed 17 September, 2022).

UBOS (2022). Uganda Profile: Economic Statistics. Available online at: https://www.ubos.org/uganda-profile/. (accessed 17 September, 2022).

UBOS WFP (2013). Comprehensive Food Security and Vulnerability Analysis (CVSVA) 2013. Kampala. Available online at: http://documents.wfp.org/. (accessed 25 May, 2020).

Van Rooyen, C., Stewart, R., and de Wet, T. (2012). The impact of microfinance in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of the evidence. World Dev. 40(11), 2249-2262. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.03.012

Wakoko, F. (2004). Microfinance and Womens Empowerment in Uganda: A Socioeconomic Approach (PhD Thesis). Ohio: Ohio State University.

Wang, X., Rafa, M., Moyer, J. D., Li, J., Scheer, J., and Sutton, P. (2019). Estimation and mapping of sub-national GDP in Uganda using NPP-VIIRS imagery. Remote Sens. 11, 163. doi: 10.3390/rs11020163

World Bank (2007). World Development Report 2008: Agriculture for Development. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank.

World Bank (2016). Global Monitoring Report 2015/2016 Development Goals in an Era of Demographic Change. Available online at: http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/ (accessed 24 June, 2016).

Keywords: microcredit, agricultural production, resource-poor, rural women, propensity score matching

Citation: Namayengo FMM, van Ophem JAC and Antonides G (2023) A comparative study on the role of microcredit on agricultural production improvement among resource-poor rural women. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7:1083660. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2023.1083660

Received: 29 October 2022; Accepted: 09 March 2023;

Published: 31 March 2023.

Edited by:

Andrea Fongar, Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, ItalyReviewed by:

Iván González-Puetate, Universidad of Guayaquil, EcuadorCopyright © 2023 Namayengo, van Ophem and Antonides. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Faith Muyonga Mayanja Namayengo, ZmFpdGhtdXlvbmdhQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==; bmFtYXllbmdvZkBreXUuYWMudWc=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.