- 1Institute for Environmental Economics and World Trade, School of Economics and Management, Leibniz University Hannover, Hannover, Germany

- 2Asian Development Bank Institute, Chiyoda City, Tokyo, Japan

In this article, we review and shed light on the interlinkages between interstate war and food insecurity and discuss global policy actions needed to address the challenges of food insecurity due to interstate war. We conceptualize the interlinkages between these two issues with a focus on: (i) the most critical and direct cause of interstate war, namely geo (territorial) political conflict, and (ii) the mechanisms through which interstate war affects four different food security pillars, namely food availability, food access, food utilization, and food stability. We position that, if unsuccessfully addressed, geo (territorial) political conflicts will create a vicious cycle of violence and hunger. This position is illustrated by analyzing recent Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Herein a summary of the root and nature of the invasion and how it has affected global food security is presented, with a discussion on the potential considerations and solutions to avoid the cycle of violence and hunger.

1. Introduction

The right to food is considered a human right. Whilst under international law, states are obliged to respect, protect and fulfill the right to food of their populations, the practical difficulties in achieving this human right are demonstrated by prevalent food insecurity across the world (Margulis, 2013). According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the number of hungry people worldwide has increased from about 630 million in 2014 to 690 million in 2019, and to between 720 and 811 million in 2020 (FAO, 2021). This means in 2020, around 1 in 10 of the world population faced hunger, and roughly 70 to 161 million more people faced hunger in 2020 than in 2019 (FAO, 2021). In addition, around 2 billion people (25.9% of the global population) did not have regular access to nutritious and sufficient food in 2019. The increase in the number of hungry and undernourished people is mainly attributed to the growing number of conflicts, climate-related shocks, or economic slowdowns due to the COVID-19 pandemic (FAO, 2021). These figures indicate that we are not on track to ending hunger by 2030 and that further actions are required to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) of zero hunger.

One of the reasons and also consequences of food insecurity is geopolitical conflict, generally referred to as conflicts with geographic and political natures and roots. Although geopolitics might also indicate relations between sub-national geopolitical entities, the term usually refers to countries and their relations. Geopolitical conflict heightens tensions between countries, and interstate armed conflict or war might happen if the conflict is not successfully solved (Sempa, 2002). The association between domestic (or within-country) armed conflict and different dimensions of food security has been well documented in the literature (see Messer and Cohen, 2007; Brück et al., 2016). However, much less is known about the interrelations of geopolitical conflict between countries and global food security. The end of the Cold War seemed to awaken the old hope of a new and democratic world freer from violence than in previous ages, and instead, the “new world order” further increased armed conflicts (Reuber, 2000). The most visible impact of armed conflicts on food security is that they destroy farmland, irrigation schemes, and infrastructure. Moreover, armed conflicts also disrupt food supply chain and distribution, creating food crises in food-importing regions. Food insecurity, in its turn, can prolong or intensify armed conflicts, creating a vicious circle of violence and hunger (Martin-Shields and Stojetz, 2019).

The Russia's invasion of Ukraine is a typical example of an armed conflict rooted in geopolitical considerations (Saâdaoui et al., 2022). The direct effects of the war are already evident. Thousands of people, mainly Russian and Ukrainian, including children and women, have died, and millions have been displaced (UNHCR, 2022). Food, fuel, and fertilizer prices have spiked. As it is widely known, war-induced food insecurity problems are very likely to trigger armed conflicts in already poor regions (Bellemare, 2015). Russia's invasion of Ukraine has led to food crises in many countries, with several of them being very poor such as Cameroon, Kenya, and Nigeria (Human Rights Watch, 2022). The current food crises due to the war in Ukraine indicate the weaknesses of the international community in governing food (in)security in conflict settings (Kemmerling et al., 2022). Since the beginning of the invasion on February 24, 2022, there have been a number of publications either on the causes or the effects on food security (Behnassi and Haiba, 2022; Harvey, 2022). However, these efforts have not linked the two issues systematically and have, therefore, been unable to provide sufficiently useful information for international policy responses.

Against this background, in this article, we review and shed light on the interlinkages between interstate war and food insecurity to better understand the global policy actions needed to address the food insecurity challenges resulting from interstate war. Our aim is not to undertake a comprehensive and systematic literature review on either interstate wars or food security, as this has been done and is available in the literature. Instead, we synthesize the literature to conceptualize the circle of violence and hunger based on the two-way relationship between interstate war and food (in)security. We use Russia's invasion of Ukraine as an example which is rooted in the geopolitical conflicts between these two countries and has profound effects on global food security. The food crises induced by this invasion are likely to trigger conflicts in other parts of the world. We use the data from secondary but reliable sources such as articles published in peer review journals or from international organizations such as FAO and the World Bank to establish our arguments supported by reliable media sources such as Reuters or Bloomberg. Our paper is structured as follows. Section Geopolitical conflict, interstate war, food security, and the circle of violence and hunger conceptualizes the interlinkages between interstate war and food security. We start this section with one of the most important causes of interstate war, i.e., geopolitical conflict. We then review the mechanisms through which an interstate war impacts different pillars of food security. We position that geopolitical conflict, if unsuccessfully addressed, will create a vicious cycle of violence and hunger, not only in the current conflicting region but also in other regions that are experiencing food crises due to the conflict. Section 3 illustrates our position regarding the current invasion of Russia to Ukraine. Herein, we briefly summarize the root and nature of the invasion and how it affects global food security. Section 4 discusses potential considerations and solutions to avoid the vicious cycle of violence and hunger.

2. Geopolitical conflict, interstate war, food security, and the circle of violence and hunger

2.1. Geopolitical conflict and interstate war

Conflict is defined as a serious disagreement or argument, typically a protracted one, between countries, human groups, and individuals (Bearce and Fisher, 2002). There are several forms of conflict, but armed conflict or war between or among countries (interstate war) is the most severe, destroying human society through loss of infrastructure and human lives. There are several causes of interstate war, such as (i) trade or commerce (Lake, 1992; Lake and Rothchild, 1996; Henderson, 1997; Henderson and Tucker, 2001; Rosato, 2003), (ii) identity or ideology (Sambanis, 2000; Sanín and Wood, 2014), (iii) geo (territorial) political issues (Flint, 2006; Valigholizadeh and Karimi, 2016), and (iv) external events or processes, such as climate change (Burke et al., 2015). Interstate war can happen due to only one or several causes. For example, the last cold war period between the capitalist and the communist blocs witnessed many geopolitical conflicts and interstate wars between or among countries in the two blocs (Sempa, 2002). The cold war also reflects the ideological differences between socialism/communism and capitalism; the Vietnam War from 1955 to 1975 is a typical example of a war on both ideology and identity. Even though it was between the North and South of Vietnam, the war was essentially between the two states: one in the North that the communist bloc supported, and the other in the South that was supported by the United States (US) and several Western countries (Miller and Wainstock, 2013). In fact, during the last several decades, armed conflicts within or between some countries have arisen as different armed groups have tried to prove their identity or impose their ideology (Ugarriza and Craig, 2013; Pettersson et al., 2021).

Among these causes, geopolitical conflict seems more complicated and challenging to address. Geopolitical conflict refers to the struggle over controlling geographical entities with an international and global dimension and using such entities for political advantage (Flint, 2006, p. 16). Thus, geopolitics involves thinking and acting geographically and explains how countries, human groups, or individuals try to reach their political goals by controlling geographic entities such as the places, regions, territories, scales, and networks that make up the world. If a geopolitical conflict cannot be resolved through peaceful methods, it could lead to war (Valigholizadeh and Karimi, 2016). Geopolitical conflict, thus, is considered one of the most potent causes of interstate war, threatening the entity and sovereignty of nation-states.

Two critical features characterize geopolitical conflict. First, it is persistent and not easy to be resolved because the causes of conflict are geographic values that are among the national and collective interests. Therefore, it is not negligible and challenging for the parties involved to compromise on it (Hafeznia, 2006, p. 126–128). Second, resolving geopolitical conflict requires goodwill, cooperative behavior, friendly relations, and trust between states involved in the conflict (Mojtahedzadeh, 2000, p. 176) and full respect and compliance with international principles and laws on the sovereignty of other states. This is even more difficult if one party of geopolitical conflict is a “super” power in international relations such as the USA or Russia, who are among the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council with the right to veto any resolutions that go against their own national interests.

2.2. Food security

The right to food was first established in 1948 in the globally recognized Universal Declaration of Human Rights. As defined by the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), the right to adequate food is realized when every man, woman, and child, alone or in a community with others, has physical and economic access at all times to adequate food or means for its procurement (CESCR, 1999). In 1974, the United Nations (UN) announced the Universal Declaration on the Eradication of Hunger and Malnutrition in the wake of the food price shocks during the 1970s and major food calamities, such as famine in Bangladesh (Wilkinson, 2015) and in 2015, Zero Hunger was created as one of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by the UN General Assembly and is intended to be achieved by 2030.

Food security is the measure of food and individuals' ability to access it. The UN Committee on World Food Security defines food security as “when all people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their food preferences and dietary needs for an active and healthy life.” According to the World Food Summit (1996), food security has four pillars: availability, access, stability, and utilization. Food availability refers to the availability of sufficient quantities of food of appropriate quality, supplied through domestic production or imports (including food aid). Food access means the access by individuals to adequate resources (entitlements) for acquiring appropriate food for a nutritious diet (e.g., through money). Food utilization refers to the quality and diversity of diets. Food stability means that food can be accessed at all times (Grote et al., 2021).

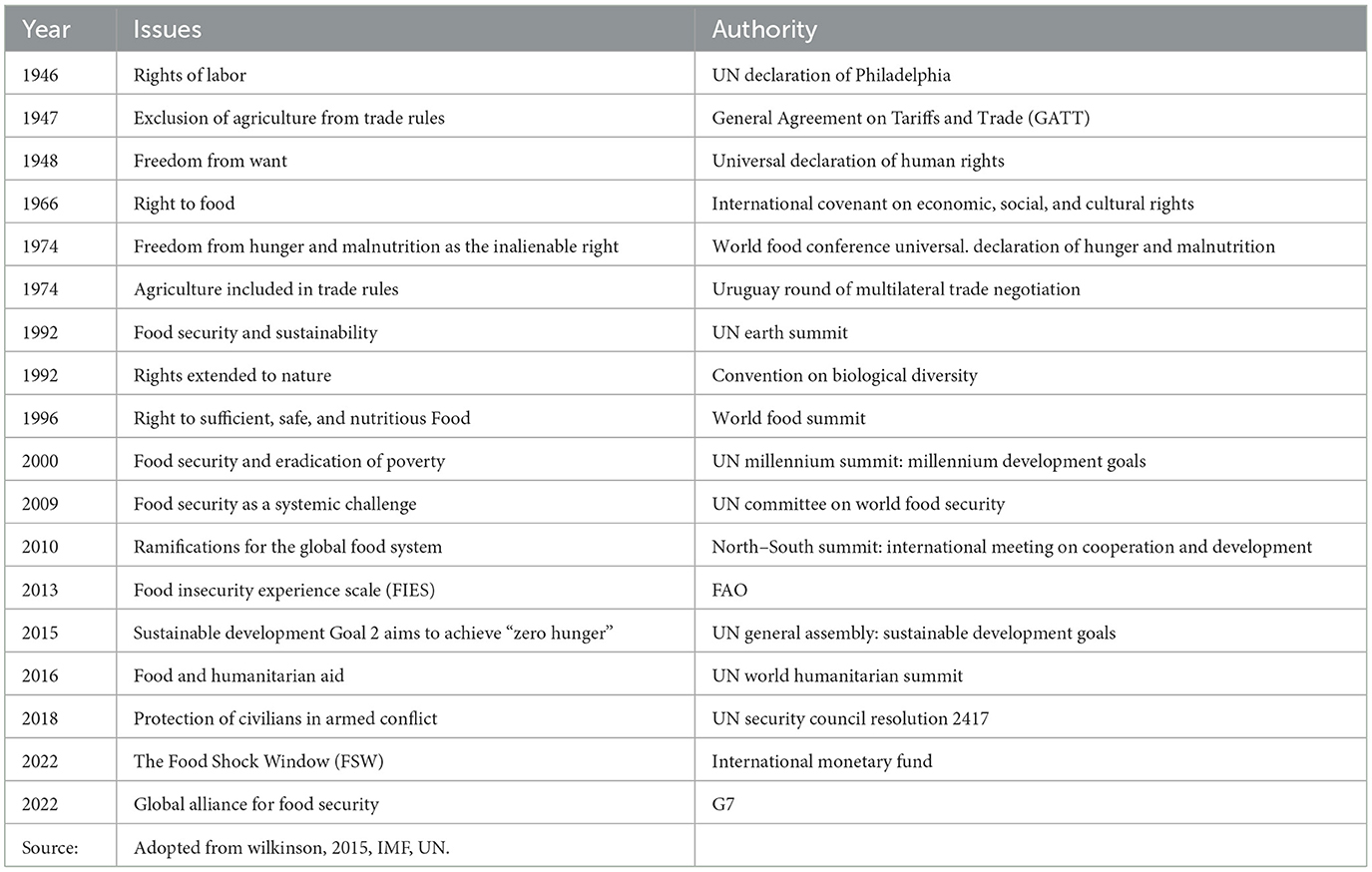

From a historical perspective, there have been milestones in understanding the food security concept (see Table 1). First, the “Right of Labor” was established in 1946 by the UN in the declaration of Philadelphia. Next, agriculture was excluded from trade rules in 1947. Access to food became a human right with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. The right to food was included in the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights in 1966. Overall, the post-war period consolidated individual rights and progress toward food security with a new geopolitical framework to exclude food from being commodification. In 1974, the UN announced the Universal Declaration on the Eradication of Hunger and Malnutrition, under which agriculture was excluded from the General Agreement on Tariff and Trade (GATT).

However, with the reformulation of the World Trade Organization (WTO), agriculture began to be progressively treated as other economic commodities. Food security has transformed structurally with historical changes in international trade and agreements and is bound by geopolitical perspectives. The US and European Union (EU) initially pushed for agricultural trade liberalization to promote a competitive agricultural economy by negotiating with the GATT and WTO. Since the 1980s, simultaneous advances in the agriculture and global food markets have impasse at multilateral level pressures for liberalizing agricultural markets with free trade agreements (Wilkinson, 2015). In 2000, the eight Millennium Development Goals were adopted at the UN Millennium Summit, in which the first goal was to eradicate extreme poverty and hunger by 2015. In 2015, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals were adopted by the UN General Assembly as part of the Post-2015 Development Agenda, including no poverty (Goal 1), zero hunger (Goal 2), and peace, justice, and strong institutions (Goal 16). Various efforts have been made to assist in the achievement of these SDGs. For example, the Committee on World Food Security (CFS) was established in 1974 and reformed in 2009 as the foremost inclusive international and intergovernmental platform for all stakeholders to work together to ensure food security and nutrition for all. FAO developed the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) to create a shortened, standardized experience-based measure for use across sociocultural contexts (Ballard et al., 2013).

In response to conflict-induced crises, including food crises, the UN World Humanitarian Summit was organized in 2016 to fundamentally reform the humanitarian aid industry to react more effectively to crises. The UN Security Council Resolution 2417 of 2018 stresses the importance of belligerent compliance with international law and condemns the denial of humanitarian access to affected civilians. The resolution also stipulates that obstructing humanitarian access in conflict settings can result in targeted sanctions (Kemmerling et al., 2022). In 2022, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) Executive Board approved a new Food Shock Window to provide a new channel for emergency fund financing to member countries that have an urgent balance of payment needs due to acute food insecurity, a sharp increase in their food import bill, or a shock to their cereal exports. Also, in 2022, the Global Alliance for Food Security was established by the G7 countries to support immediate aid measures relating to food security and facilitate the long-term transformation of global agri-food systems toward more resilience and sustainability. Despite all these efforts, ensuring food security is still a challenge, especially in the context of increasing geopolitical and armed conflicts worldwide.

2.3. Interlinkages between interstate war, food security, and the circle of violence and hunger

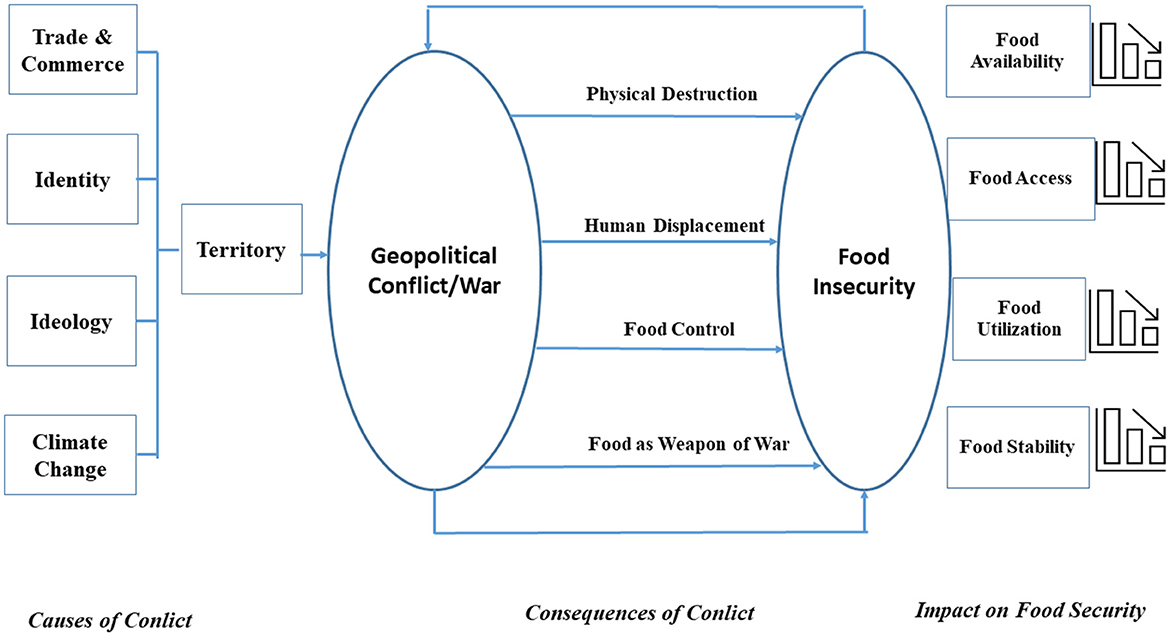

Interstate war, primarily due to geopolitical conflict, and food security are characterized by high complexity and contextualization. On the one hand, geopolitical conflict negatively affects the level of food security and, thus, is considered a cause of food insecurity as it reduces food availability, access, utilization, and stability. On the other hand, food insecurity can cause or trigger conflict (Messer and Cohen, 2007). Interstate war affects food security in conflict regions directly and in other regions indirectly. There are at least five channels through which an interstate war affects food security (Figure 1): physical destruction, human displacement, food control, hunger as a weapon of war, and disruptions in trade and value chains. The first four channels can be easily observed in a conflict region as war destroys agricultural land, irrigation schemes, and infrastructure; displaces humans; and creates starvation, and threatens the food security of the affected population (Kemmerling et al., 2022). In interstate wars, belligerent states aim to harm, defeat, or even eliminate their enemies, and consequently, this results in massive physical destruction, which affects people's vulnerabilities.

Figure 1. Interrelations between interstate war, food security, and the circle of violence and hunger.

The destruction of agricultural land and related infrastructure due to armed conflicts and the expansion of war zones lead to mass displacement. The impacts on food security are direct and severe in both the short- and long-term. War-induced displacement leads to the collapse of agricultural production and the decay of infrastructure at the origin; disrupts or interrupts local, regional, or even international supply chains; and increases food prices. At the same time, the displaced are exposed to food insecurity. The government or armed forces undertake food control because the food supply is of strategic economic importance to any armed group.

During conflict or crisis, food security concerns might force food-exporting countries to halt or stop their food exports, thereby reducing food supply in international markets, which leads to food price spikes and results in severer food insecurity in food-importing countries. In addition, when conflicts are directed at certain human groups, food insecurity can become a “weapon of war” (Messer and Cohen, 2015), either as an intended strategy or a by-product. The goal is either to deprive a particular warring party or to eliminate entire population groups by starvation (e.g., ethnic cleansing or genocide) (Kemmerling et al., 2022), even though the 1996 World Summit on Food Security declares that food should not be used as an instrument for political and economic pressure. Lastly, interstate wars disrupt the import and export of agricultural inputs and food imports and exports and increase food prices, and this results in food crises in other parts of the world that depend on food imports.

Food insecurity, in turn, can spark, intensify, or perpetuate violent conflict (Buhaug et al., 2015; Martin-Shields and Stojetz, 2019). While food insecurity alone might not be able to cause violent conflict, it can become a decisive factor in increasing social grievances, combined with threats to livelihood, socioeconomic inequalities, and political marginalization (Kemmerling et al., 2022). These factors ignite a vicious circle of violence and hunger and vice versa. A well-known example in history is the French Revolution of 1789, primarily fuelled by poor grain harvests that led to sharp increases in the price of essential food commodities, such as bread (Miguel et al., 2004; Bruck and Schindler, 2009). The Arab Spring uprisings of 2011 brought historically high food prices in North Africa and the Middle East. Several other contemporary internal wars indicate the nuances of hunger problems, such as in South Sudan in 2013, Syria in 2011, and Yemen in 2018 (Miguel et al., 2004; Pettersson et al., 2021; Bjornlund et al., 2022). Bellemare (2015) argues that rising food prices causes social unrest and lead to food riots. Food insecurity may trigger, fuel, and sustain conflicts that channel broader grievances, such as poverty, unemployment, low incomes, unpaid salaries, and political marginalization (Brinkman and Hendrix, 2011; Maystadt and Ecker, 2014). Overall, in this way, food insecurity forces more people to be involved in the conflict. Consequently, the vicious cycle of violence and hunger continues to affect people worldwide. As stated by Houngbo (2022), conflict and hunger are closely intertwined; when one of them escalates, the other follows; and it is the poorest and most vulnerable who are hardest hit, and in our globalized world, the impact of the conflict will reverberate across continents.

3. Russia's invasion of Ukraine and global food security

3.1. Root and nature of Russia's invasion of Ukraine

Ukraine is located in Eastern Europe and borders Russia to the east and northeast, Belarus to the north, Poland, Slovakia, and Hungary to the west, and Romania and Moldova to the southwest. The country has a coastline along the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. Essentially, it is at the crossroads of Russia and Europe. Ukraine used to be a member of the Soviet Union but became a sovereign state after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Although most of the population in Ukraine is ethnically Ukrainian, there is a significant ethnic Russian minority, particularly in the eastern region. While the official language in Ukraine is Ukrainian, most people can speak both Ukrainian and Russian (Gessen, 2022). Ukraine was the second most populous and powerful of the 15 Soviet republics. The country is, therefore, significant to Russia geopolitically, historically, and culturally. According to Masters (2002), in its three decades of independence, Ukraine sought to forge its path as a sovereign state while aligning more closely with Western institutions, including the EU and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). However, Kyiv has struggled to balance its foreign relations and bridge deep internal divisions. A more nationalist, Ukrainian-speaking population in western parts generally supported greater integration with Europe, while a primarily Russian-speaking community in the east favored closer ties with Russia (Masters, 2002).

On the Russian side, after the Soviet collapse, many Russian politicians, including long-time president Putin, viewed the divorce from Ukraine as a mistake of history and a security threat to Russia (Masters, 2002). President Putin has undertaken a policy based on the assumption that the national identity of Ukraine is artificial and, therefore, fragile. This helps explain the root of the current conflict. It also suggests that Moscow's ambitions extend beyond preventing Ukrainian NATO membership and encompass a more thorough aspiration to dominate Ukraine politically, militarily, and economically (Mankoff, 2022).

The geopolitical issues from both the Russian and Ukrainian sides are reflected in what has been happening in these regions. In 2014, Russia launched an attack on Ukraine, citing that the invasion was just a defense of ethnic Russians who live in the eastern Donbas region (Reals and Sundby, 2022). Russia also used the invasion to annex the Crimean Peninsula unilaterally and has since continued to occupy it even though the international community does not recognize the annexation (Nguyen and Do, 2021). Since 2014, an armed conflict between the Russian-backed separatists and the Ukrainian government has been intensifying in the eastern Donbas region.

A peace deal in 2015 put an end to major battles, but the armed conflict has continued. Russia has now unilaterally recognized the independence of two regions in Donbas (Donetsk and Luhansk) held by the Russian-backed separatists, breaking the peace deal. With the justification that Russia could not feel “safe, develop and exist” due to a serious threat caused by Western-leaning Ukraine, Russia, on February 24 2022, authorized airstrikes across Ukraine and ordered armed forces to advance into the country (Osborn and Nikolskaya, 2022; Reals and Sundby, 2022). In response to Russia's invasion of Ukraine, the USA, EU, and several other countries and entities have been imposing a range of economic sanctions against Russia, targeting the allies of its top leaders, Russia's banking system, and its access to crucial technology. In response to the economic sanctions, Russia has also retaliated by imposing an export ban for more than 200 products, including agricultural and some forestry products, which could directly affect developing nations relying on agricultural imports from Russia (Bloomberg, 2022).

3.2. Role of Russia and Ukraine in global food markets

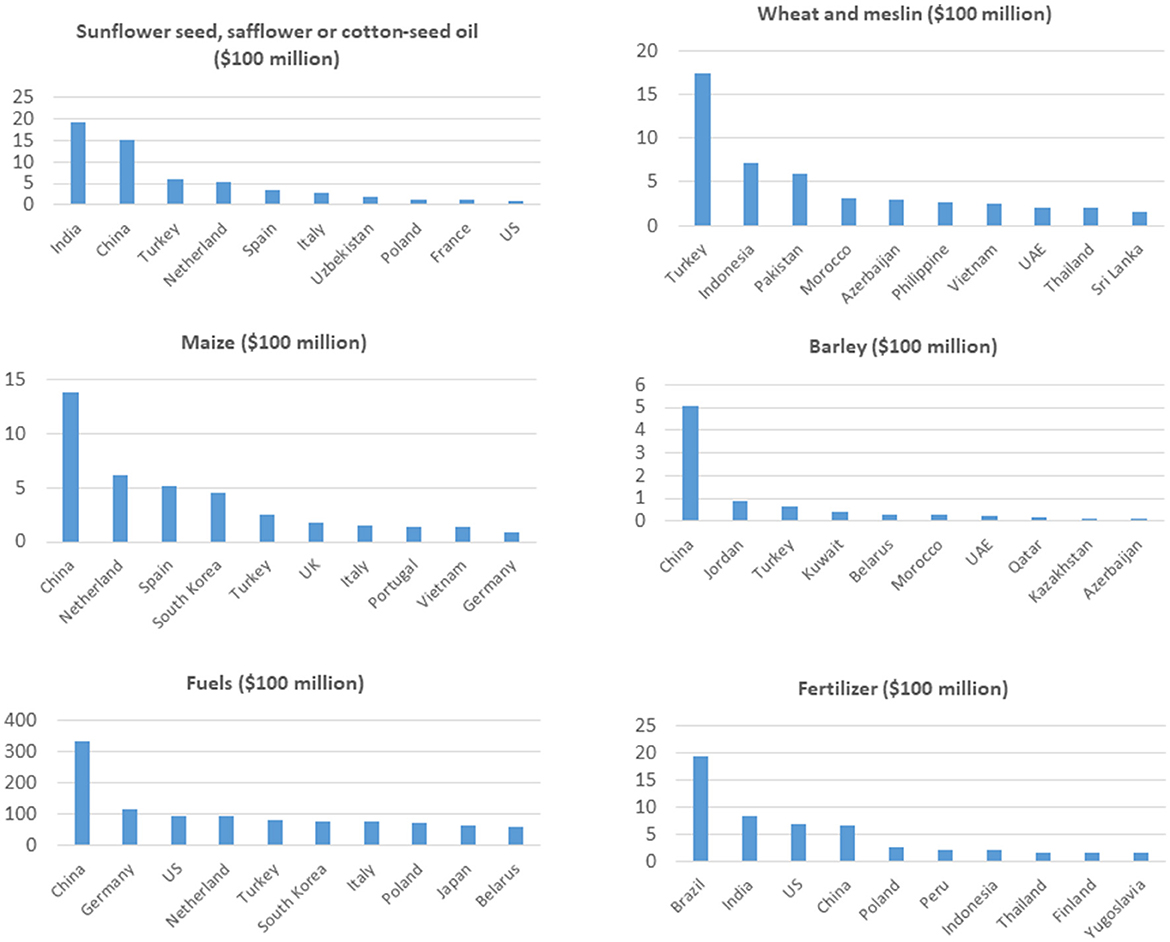

Ukraine and Russia are major producers and exporters of many food commodities, such as wheat, barley, maize, and vegetable oils. Each country contributes about 6% of global market shares in food calories (Emediegwu, 2022). Ukraine is the world's largest producer of sunflower oil and the fourth, fifth, and sixth largest producer of maize, barley, and wheat, respectively. Together, Ukraine and Russia provide more than half of the world's exports of sunflower oil and approximately about 22, 20, and 14% of global exports of wheat, barley, and maize, respectively (Table 2). They rank first as the world's largest producers of essential staple foods such as wheat, meslin, and barley. In addition, the two countries also come in fourth place as the world's largest producers of maize. Since low-income countries depend more on staple foods in their diets compared to higher-income nations (FAO et al., 2020). Ukraine and Russia, thus, play an important role in feeding the world population, especially the poor and vulnerable. The disruption in the supply of these important staple foods to their trading partners has increased their prices globally, hurting the poor and vulnerable whose diets consist mainly of staple foods (FAO et al., 2020).

Table 2. Export value, share of total world exports, and world ranking of major exported food commodities and agricultural inputs from Ukraine and Russia in 2020.

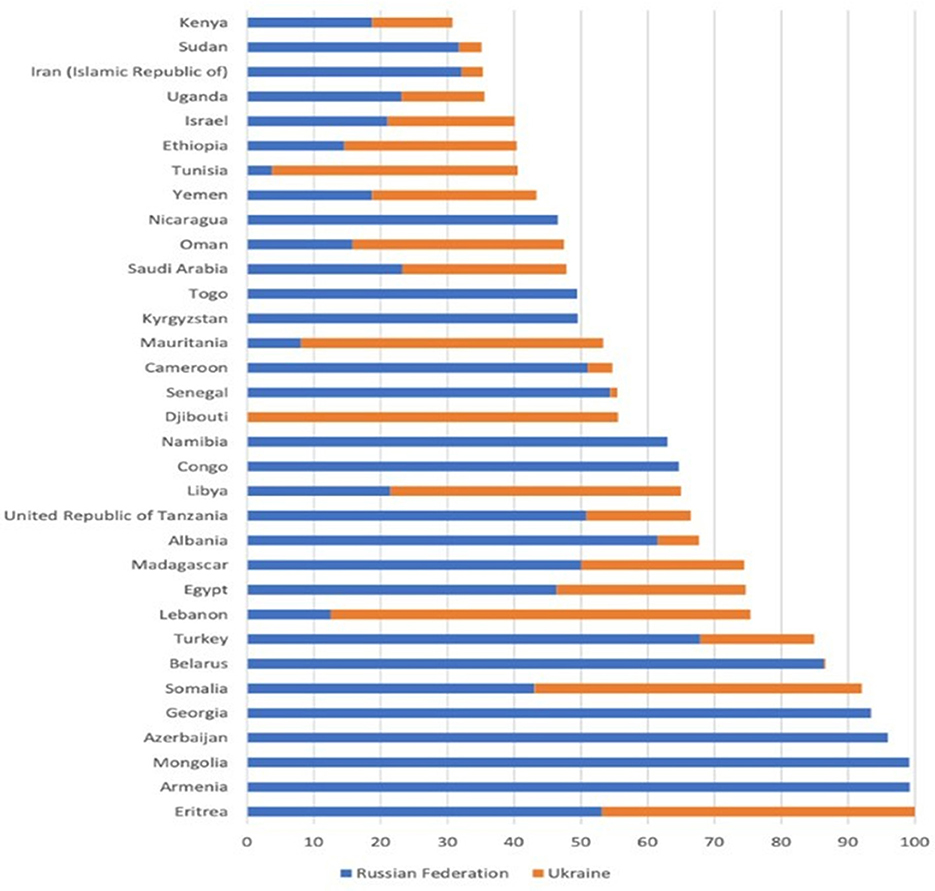

Ukraine and Russia also export their food commodities and important agricultural inputs such as fertilizer and fuel to developed and developing countries. As the world's largest exporter of wheat, meslin, barley, and sunflower oil, Ukraine and Russia's agricultural imports reach a wide range of nations, from the world's most populous country (China) to one of the world's poorest countries (Somalia). According to the world trade data in 2020, the top importers of Ukrainian and Russian sunflower oil are India, China, Turkey, and some European countries, while the Middle East and South and Southeast Asia are the leading importers of important grains such as wheat, maize, and barley from the two countries (Figure 2). Similarly, China, Brazil, India, and some Southeast Asian countries are among the top ten largest importers of crucial agricultural inputs such as fertilizers and fuels. Although the majority of the top importers of staple foods and agricultural inputs from Ukraine and Russia have a relatively large economy, a large share of their population still suffers from poverty, nutrition, and food insecurity (i.e., India, China, Brazil, and Southeast Asian countries). In addition, ~40% of wheat and maize from Ukraine is supplied to the Middle East and Africa, where hunger issues are pressing (IFAD, 2022). Up to 25 African countries, many of which are least developed countries, import over one-third of their wheat supply from Ukraine and Russia (UNCTAD, 2022). The countries include, for example, Eritrea, Somalia, Egypt, Madagascar, Tanzania, Libya, Congo, Namibia, Djibouti, Senegal, Cameroon, Mauritania, Togo, Tunisia, Ethiopia, Sudan, and Kenya. Moreover, humanitarian organizations also buy their grain supply from the region. For instance, the World Food Program (WFP) purchases half of its grain supply from Ukraine (Bearak, 2022). Therefore, the supply of staple foods and agricultural input products from Ukraine and Russia is crucial in achieving the world's food security and nutrition.

Figure 2. Top 10 countries importing major food commodities, fertilizer, and fuels from Ukraine and Russia [Source: Data from the World Integrated Trade Solution of the World Bank (https://wits.worldbank.org/)].

The food supply disruption from Ukraine and Russia could jeopardize the food security of many low-income countries worldwide. Figure 3 projects that wheat imports in many African and Middle East countries are highly concentrated toward supplies from Ukraine and Russia. The figure also shows that there are 33 countries whose wheat imports from Ukraine and Russia account for more than 30 percent of their total wheat imports. African nations, including Eritrea, Somalia, and Egypt, are among the top 10 net wheat importers from Ukraine and Russia. Six countries, including Somalia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Mongolia, Armenia, and Eritrea, have a wheat import dependency level of more than 90%, an overly concentrated level. In case of disruption of wheat supply from Ukraine and Russia, the food security of these countries would fall into a crisis.

Figure 3. Wheat import dependency (%) of net wheat importers from Ukraine and Russia, 2021 (Source: FAO et al., 2020).

3.3. Impact of the war on food security

The ongoing war has affected food security through several channels, as described in Figure 1, including physical destruction, human displacement, food control, food as a weapon of war, and disruptions to the trade and value chains of many food and energy commodities. Farmland, irrigation systems, agricultural machinery, and other facilities have been destroyed within Ukraine, and Ukrainian farmers joined military forces, died, or were displaced. By June 2022, at least 45 million square meters of housing, 256 enterprises, 656 medical institutions, and 1,177 educational institutions in Ukraine had been damaged, destroyed, or seized. The Kyiv School of Economics estimated that the damage done so far to building and infrastructure was nearly $104 billion, and the Ukrainian economy had already suffered losses of up to $600 billion (Deutsche Welle, 2022). Since February 24, 2022, tens of thousands of people have died in this ongoing war (Reals and Sundby, 2022; UN News, 2022). More than 5 million Ukrainians have fled their homes to bordering countries (Russia, Poland, Romania, Moldova, Slovakia, Hungary, and Belarus) to seek safety, and approximately 8 million people are displaced inside Ukraine (BBC, 2022a). Despite various efforts by the EU, UN, and individual nations, such as Germany, Poland, and Turkey, food exports from Ukraine have been very limited due to shuttered ports and mined maritime routes in the Black Sea. Commercial operations in Ukraine's ports have been suspended, making food exports from the country for several months impossible.

Both Russia and Ukraine have undertaken food control, and Russia has been trying to use food as a weapon. The former Russian president and senior security official Dmitry Medvedev called food exports a “quiet weapon” in the fight against Western sanctions: “Many countries depend on our supplies for their food security,” Medvedev wrote on his Telegram channel on April 1, 2022, and “it turns out that our food is our quiet weapon” he wrote. The invasion and its associated sanctions imposed by and on Russia have also disrupted the export of food and agricultural inputs such as fertilizer and energy. In addition, several other countries have already ban or announced their intention to ban exports of food and essential agricultural inputs, such as India, Egypt, Argentina, Indonesia, Serbia, Turkey, and Hungary (EU, 2022; Nicas, 2022). These all have caused food shortages and price hikes that have pushed millions of vulnerable people into poverty.

3.3.1. On food availability

The invasion affects global food availability directly through a reduction in food production. According to FAO, the invasion causes major concerns on food production due to disruptions to harvesting and planting; agricultural labor shortages; access to and availability of farm inputs such as fertilizer and fuels; disruption of logistics and food supply chains; abandonment of and reduced access to agricultural land; damage to crops due to military activities; and destructions of food system assets and infrastructure (FAO, 2022).

Since the onset of the war, Ukraine's most productive agricultural regions have fallen under Russian control (Bearak, 2022). As farms are either shut down or occupied by Russian soldiers, future agricultural output in Ukraine will likely decline sharply (Emediegwu, 2022). Former Ukrainian agriculture minister Roman Leshchenko estimated that the country's spring crop sowing area in 2022 may be less than half of the previous year, about 15 million hectares (Polityuk, 2022). As of April 2022, it is reported that only 210 square kilometers had been cultivated in the Chernihiv oblast, compared to about 10,000 square kilometers last year (Mercy Corps, 2022).

Besides the reduction of available farm area, the availability of agricultural labor also declines due to war-induced displacement. Many farmers are among the 8 million displaced inside Ukraine, and 5 million who fled their homes to neighboring countries to seek safety. For remaining farmers in the country, their time working in the fields is also limited due to imposed curfews and security reasons (Emediegwu, 2022). Since workers are at risk when working on farms during the war, several major agribusinesses have stated that a number of plantings would not be possible this year (Durisin and Choursina, 2022). The oilseed crushing operations in the country are also suspended (FAO, 2022b).

Another major negative effect of the war on food production is the destruction of food system assets and infrastructure. The damage to farms, storage facilities, agricultural equipment, roads, and railways all contributes to a decline in food production. For instance, shelling caused a warehouse fire in Ukraine's largest frozen-food store, damaging about $8.5 million worth of frozen chickens (Durisin and Choursina, 2022). Many more warehouses of other food commodities are also at risk since damaged roads and railways limit access to facilities (Durisin and Choursina, 2022). According to a study by the Kyiv School of Economics (2022), at least 195 factories and enterprises, 295 bridges and bridge crossings, and 151 warehousing infrastructures have been damaged, destroyed, or seized. The study estimated that total damages to Ukrainian business assets amounted to almost $10 billion.

The reduction of food production in Ukraine has led to lower food exports. With port closures and export licensing restrictions for major crops and food commodities, the exports of Ukraine's giant industrial agriculture sector may decline sharply or even completely halt. In response to the severe economic sanctions (The New York Times, 2022), Russia has also retaliated by imposing an export ban for more than 200 products, including agricultural products and some forestry products (Bloomberg, 2022). Without export income, farmers may go bankrupt, and the global grain supply will become increasingly limited even after the end of the war (Bearak, 2022). The conflict reduces food supply not only in the conflict zones due to a decline in food production but also in the rest of the world due to a fall in the export of major staple food commodities and agricultural inputs such as fertilizers and fuels (Emediegwu, 2022). The EU estimated that an additional amount of 25 million tons of wheat is needed to meet worldwide food needs in the current and the following season (EU, 2022). All these factors caused by the invasion have contributed to the reduction in global food availability.

3.3.2. On food access

Food access reflects the number of food choices that individuals or households can consume, given the prevailing prices, income, and safety net arrangements through which food can be accessed (Barrett, 2010). The invasion affects global food access mainly through increases in prices of food, fuel, and fertilizer, as well as in the level of economic uncertainty, which reduces consumption and investment, with depressive effects on economic growth and employment. As discussed above, the availability of major food commodities declined while food demand remained high, increasing food prices in both local and global markets. The increase in food prices means lower access to food and thus rising food insecurity, not only in the conflict zones but also in the rest of the world. Besides the effect on the global grain market–which directly affects global food security–the conflict also indirectly threatens global food security through an increase in energy and fertilizer prices. As fuels and fertilizers are important inputs for agricultural production, a rise in their prices increases agricultural production costs and thus further increases food prices.

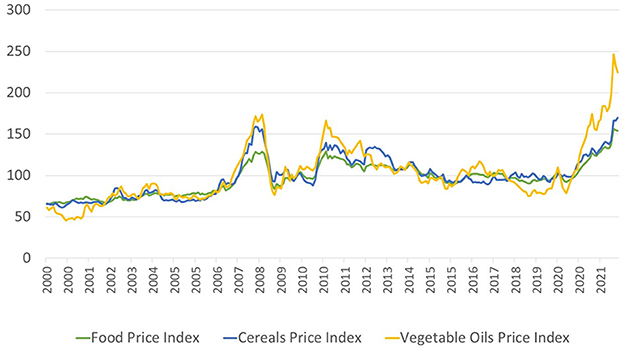

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, food prices have been rising since mid-2020. The war between two of the top producers of food commodities, and the intention to control food export by some other countries, for example, India, has pushed prices into the realms of the 2008 and 2011 food price crises (Husain et al., 2022). The FAO Food Price Index, an indicator showing the monthly change in international prices of a pre-determined basket of food commodities, reached a new all-time high in February 2022 (FAO, 2022a; Rice et al., 2022). Figure 4 shows that, after one month into the war, the FAO Food Price Index reached 156 points in March 2022, an increase of 17% from January 2022 and 31% higher than its level in 2021. This war-induced food price hike reached an even higher level than during the food price crises in 2008 and 2011. The vegetable oils price index saw the sharpest increase, and it rose to an average of 246 points in March 2022, a sharp increase of 35% in the two months. The cereal prices index also rose sharply after the onset of the war, a rise of 20% from January to March 2022.

Figure 4. Price indices of food, cereals, and vegetable oils, 2000–2022 (Source: FAO, 2022).

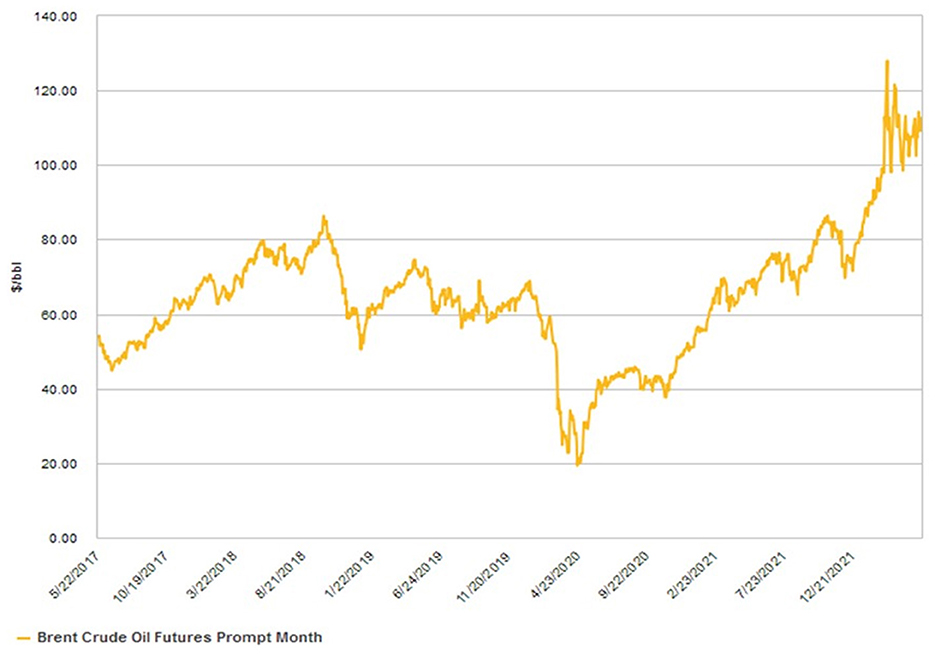

Russia is the world's third-largest exporter of mineral fuels and oils, after USA and Saudi Arabia (Table 2). Russia is also the largest producer and exporter of fertilizer. Various sanctions imposed on Russia, including the ban on Russian oil and gas imports, have resulted in a sharp rise in fuel prices in the international market (BBC, 2022b). With the ban on oil supply from Russia and other top oil producers being unable or unwilling to raise their output in the near future, the price of Brent crude oil (the global benchmark) reached $128 per barrel in early March 2022, up almost 65% since early January and the highest since 2015 (Lynch, 2022) (Figure 5). It should be noted that Figure 5 also illustrates a sharp fall in oil price in early 2020, mainly due to a decrease in demand resulting from business closure and travel restrictions during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Oil price began to increase in May 2022 following an agreement between oil-producing countries to reduce oil production. Since then, oil price have seen an increasing trend until it rose sharply after the onset of the war in Ukraine in February 2022.

Figure 5. Brent crude oil price per barrel in US dollars, 2017–2022 [Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence. Market & financial data application (S and P Global Market Intelligence, 2022)].

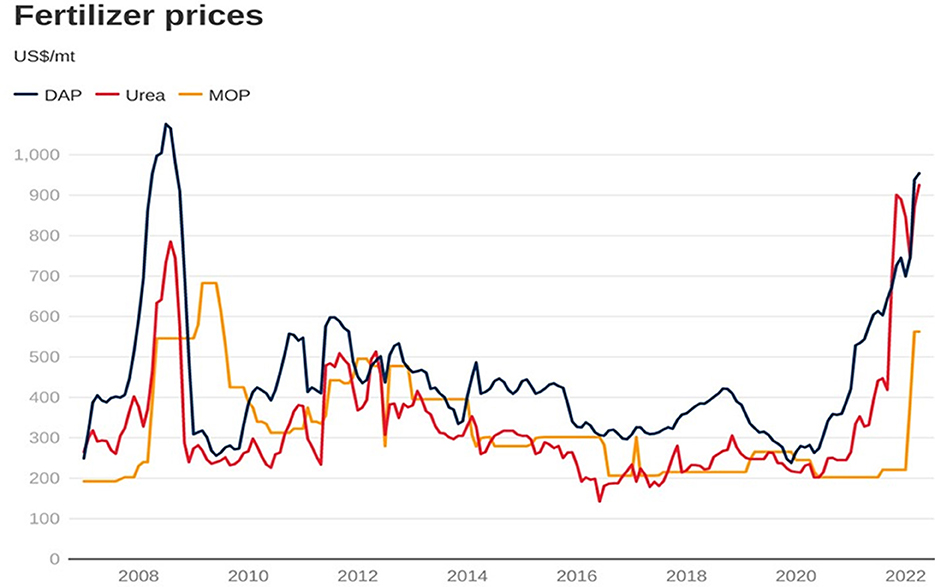

The fertilizer market is subject to supply disruptions as nitrogen-based fertilizers are produced mainly from natural gas, and the price of natural gas has soared since 2021, pushing some fertilizer prices to their highest levels since 2010. In early March 2022, Russia's Industry Ministry announced that it would temporarily suspend fertilizer exports, and the announcement followed an earlier ban on ammonium nitrate to guarantee supplies to domestic farmers. China has also suspended urea and phosphate exports through June 2022 to ensure adequate supplies for domestic food production. As Russia and China are the world's two largest suppliers of fertilizers, fertilizer prices have thus been on the rise (Figure 6). For instance, the price of urea reached a level higher than 900 US$/mt in early 2022, compared to less than 400 US$/mt in early 2021.

These all lead to increases in commodity prices worldwide. In the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, food price has continued to increase, reaching 12.6% in May 2022 compared with 11.5% in April. The energy price jumped to 35.4% year-on-year in May 2022, up from 32.9% in April (OECD, 2022). Excluding food and energy, year-on-year inflation increased to 6.4% in May 2022, compared with 6.2% in April 2022. The G7 area saw an increase in year-on-year inflation in May, reaching 7.5%, compared with 7.1% in April. It increased in all G7 countries except Japan, which was stable (at 2.5%), with the most substantial rises between April and May 2022 recorded in Canada and Italy (OECD, 2022). These price hikes have lowered purchasing power and reduced access to food. This is especially significant for poorer net food purchasers, whose food expenses comprise a high proportion of their total income.

Besides the increase in food prices and production costs, Ukrainian households also face a fall in their income due to the deaths of household laborers, job losses following damage to infrastructure and businesses, and reduced economic activities (Emediegwu, 2022). Loss of income coupled with the rise in food prices makes it even more challenging for Ukrainians to access food. In the rest of the world, especially in poor countries, higher food price reduces household's real incomes, pushing vulnerable households into the food poverty trap. This effect on household's real incomes is more serious for developing nations since a higher share of a household's disposable income is spent on food. According to UNCTAD (2022), on average, more than 5% of the poorest nation's import baskets are commodities, of which prices are expected to increase following the onset of the war; the share is <1% for richer nations.

In addition, the invasion has increased the level of economic uncertainty, which reduces consumption and investment, with depressive effects on economic growth and employment. High inflation forces central banks worldwide to increase interest rates and causes companies to reduce production, delay investment, and decrease employment.

3.3.3. On food utilization and stability

Food utilization refers to the food safety and diversity of diets that individuals or households choose to consume based on their affordability (Barrett, 2010), while food stability refers to a condition in which food can be accessed at all times (Grote et al., 2021). According to Koren and Bagozzi (2016), food utilization and utility are less likely to be directly affected by conflict than food availability and access. Nevertheless, since food utilization and stability depend largely on access to food, which, in turn, depends largely on food availability, the ongoing invasion–which intensely hurts availability and access to food–also indirectly jeopardizes food utilization and stability as well.

When access to food is being disturbed due to the war, as discussed above, households, especially the poor and vulnerable ones, are prone to hunger. Thus, food safety and diversity aspects may seem less relevant to their needs. For the less vulnerable households who may not be pushed into hunger due to the war, their access to food is still lowered due to higher food prices, reduced real income, and damaged infrastructure. Therefore, their ability and concern about food safety and diversity would be reduced, thereby decreasing their food utilization. Currently, there is no sign that the invasion will end soon, which means that food availability and access will be further affected. In addition, it will take time, probably years, depending on post-war efforts, for agricultural infrastructure to be rebuilt to the pre-war level. According to Welsh and Dodd (2022) from the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), rebuilding Ukraine's agricultural sector also requires huge investments in establishing new transportation routes and increasing storage capacities. These all indicate that food utilization and stability remain affected.

4. Addressing the circle of violence and hunger

The invasion was not expected and was a surprise to many people who thought such an invasion would never come true in Europe. Of course, undertaking an unprovoked war against an independent country, killing tens of thousands of people, including women and children, and threatening the independence and sovereignty of other nations is another matter which is absolutely intolerant. The conflict has been protracted, and there is no sign that it will finish soon, which means that its impacts on global food security will remain and will likely trigger food insecurity-induced conflicts in other regions. Thus, in the following, we position some key challenges that should be addressed to avoid the vicious cycle of violence and hunger.

4.1. Mediating geopolitical conflict to avoid interstate war by facilitating democracy, dialogue, and trust building

Promoting democracy, dialogue, and trust building should also be considered key to avoiding armed conflict and food security. Gowa and Mansfield (1993) use data for an 80-year period beginning in 1905 and position two findings: (i) free trade is more likely within, rather than across, political-military alliances; and (ii) alliances are more likely to evolve into free-trade coalitions if they are embedded in bipolar systems than in multipolar systems. Similarly, Gartzke (2007) introduces the term “capitalist peace” as a result of economic development, free markets, and similar interstate interests that anticipate lessening militarized disputes or wars. Walter (2003) argues that governments are more concerned with the long-term reputational effects of their actions when they decide how to respond to a demand for greater self-determination that is heavily influenced by reputation and by the level of democracy and government military spending.

Simmons (2005) argues that governments are less likely to engage in territorial disputes as economic actors. Settled boundary agreements benefit economic agents on both sides of the border. Settled borders help to secure property rights, signal much greater jurisdictional and policy certainty, and involve significant economic opportunity costs in the form of foregone bilateral trade. Lake (1992) and Lake and Rothchild (1996) explain that democratic nations are more likely to prevail in a conflict with autocratic ones as autocracies are more expansionist and, in turn, conflict-prone. They further argue that democracies are constrained by societies from rent-seeking behaviors and devote greater resources to security, enjoy greater societal support for their policies, and tend to form overwhelming counter-coalitions against expansionist autocracies. Moreover, trust is a central requirement for the peaceful and effective management of all relationships, and thus, building and maintaining trust is critical in resolving conflicts in general and geopolitical conflicts in particular (Kelman, 2005). One of the claims that President Putin made with regard to the war is that the national security of Russia has been increasingly threatened by Ukraine and NATO. Hughes (2022) and Das (2022) claim that the trust between Russia and the West had been eroded, which led to the war. Under such circumstances as the loss of trust, the nation need to engage in policy dialogue to prevent armed conflict. Even nations should be able to raise such issues with United Nations.

4.2. Preventing interstate war by complying with international law and improving the UN Security Council

Addressing geopolitical conflict is difficult, but that cannot be the excuse for any invasion of sovereign nations. One of the principles set out in the UN Charter and signed by all UN members is to respect the national sovereignty and territorial integrity of all nation-states. The Russia's invasion of Ukraine indicates the weakness of the global security system. Except for a few countries, the majority of the international community has condemned the invasion. However, this is far from being able to force Russia to end the invasion. Thus, the first issue for the UN system is to establish a mechanism to control for the compliance of this principle from all UN member states, and all violations must be accounted for and paid for.

The second issue is to restructure and improve the UN Security Council. Currently, all UN General Assembly resolutions are generally non-binding toward member states. The UN Security Council is primarily responsible for maintaining international peace and security, and all UN member states are obligated to comply with Council decisions. However, the Council has not been able to undertake any effective measures in preventing or terminating the invasion due to the veto right of Russia as one of the five permanent members. Therefore, the veto right of the permanent members must be terminated if one of these great powers ignores the principle of respecting the national sovereignty and territorial integrity of other nation-states and undertake an invasion. As demonstrated from the invasion of Russia, the security in general, and food security in particular, of many countries have been and will continue to be negatively affected by the invasion. This must not happen again.

The ineffective operation of the current international political system and non-binding resolutions of the United Nations and other global institutions place small nations (in terms of size, economy, and defense capabilities) in a disadvantageous situation. In addition, institutions like the International Court of Justice are not able to intervene. Therefore, a significant challenge facing humanity today is to create a system that will ensure compliance with international law and resolutions and respect for the sovereignty and territory of other nations/states and human rights.

4.3. Ensuring the right to food and food security for all

Global communities should address several challenges to ensure the right to food and food security for all. The first challenge is food access. Humanity has made significant progress in terms of food production. The gain in food production has been mainly through intensification rather than an increase in the land area, as there is little or no room for expansion of the land area for agriculture. With climate change, land degradation, and water stress, it is becoming increasingly difficult to feed the growing population. Despite tremendous progress, a large section of the population is hungry, and many cannot afford a healthy diet. Currently, the problem of food unavailability is not severe, but those of food access; thus, the food security policy should focus on improving the distribution system and reducing food waste and loss. Further, inclusive development to support the poor would help reduce food and nutritional insecurity.

The second challenge is the myopic behavior of some nation-states with regard to food security. Food security strategies should avoid myopic behavior and focus on national, regional, and international food security. For peace and a prosperous world, for food security, we have to work as one global community, not as individuals. Policy to support global nutrition and food security should prioritize local, national, regional, and international priorities. As food is crucial for the sustenance of life, the international community should prevent nations from using food commodities and agricultural input as a weapon of war or coercing other governments.

The third challenge is on agricultural research and development. Global communities should support the development and dissemination of technology through research. Investment to produce and deploy agricultural technology combined with sound distribution systems and trade of food and agricultural products will ensure the food supply. Global communities should not allow escalation of aggression and interstate conflict as it is detrimental to global supply chain, economic growth, life, and food security. Countries dependent on imports should diversify the sources of imports, build a partnership with stable nations, and prepare a food security strategy for various uncertainties.

The next challenge is a lack of global good governance and respect for international treaties and sovereignty that generally triggers conflicts and uncertainties. Thus, the anarchical structure of the international political system should be changed to ensure equality, stability, and peace, thereby reducing uncertainties in the global value chain and food supply. Although food security has been of particular attention to the international community, and it is widely acknowledged that the problems of food insecurity are beyond the capacity of individual states to manage alone (Margulis, 2013), it is surprising that so far, there have been no global or international food security agreements or treaties. Therefore, improving the global governance of food security to address rising world hunger and improve the efficacy of existing food security interventions is a pressing need. The efforts of FAO, WFP, the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), and other international and regional institutions (e.g., the World Trade Organization) seem insufficient, especially during food crises such as the 2007-2008 World Food Price Crisis or the current food crisis due to the COVID-19 pandemic or the Russia's invasion of Ukraine. In this regard, a global or international food security treaty should be established with the participation of both rich and poor nation-states as well as non-state institutions.

Author contributions

TN conceptualized and wrote the paper. RT collected, analyzed the data, and contributed to drafting the paper. TS and DR conceptualized and edited the text. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI) for the support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the authors' institutions, and the usual disclaimer applies.

References

Ballard, T., Kepple, A., and Cafiero, C. (2013). The Food Insecurity Experience Scale: Development of a Global Standard for Monitoring Hunger worldwide. FAO, Rome.

BBC (2022a). How Many Ukrainians Have Fled Their Homes and Where Have They Gone? Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-60555472 (accessed December 2022).

BBC (2022b). What are the Sanctions on Russia and Are They Hurting Its Economy? Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-60125659 (accessed December 2022)

Bearak, M. (2022). Ukraine's Wheat Harvest, Which Feeds the World, Can't Leave the Country. The Washington Post. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/04/07/ukraine-wheat-crop-global-shortage/ (accessed December 2022).

Bearce, D. H., and Fisher, E. O. (2002). Economic geography, trade, and war. J. Confl. Resolut. 46, 365–393. doi: 10.1177/0022002702046003003

Behnassi, M., and Haiba, M. (2022). Implications of the Russia–Ukraine war for global food security. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 754–755. doi: 10.1038/s41562-022-01391-x

Bellemare, M. (2015). Rising food prices, food price volatility and social unrest. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 97, 1–21. doi: 10.1093/ajae/aau038

Bjornlund, V., Bjornlund, H., and van Rooyen, A. (2022). Why food insecurity persists in sub-Saharan Africa: a review of existing evidence. Food Sec. 14, 845–864. doi: 10.1007/s12571-022-01256-1

Bloomberg (2022). Russia Bans Export of 200 Products After Suffering Sanctions Hit. Bloomberg. Available online at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-03-10/russia-bans-export-of-200-products-after-suffering-sanctions-hit?leadSource=uverify%20wall (accessed December 2022).

Brinkman, H. -J., and Hendrix, C. (2011). Food Insecurity and Violent Conflict: Causes, Consequences, and Addressing the Challenges. Occasional Paper No. 24. World Food Program, Rome. doi: 10.1596/27510

Brück, T., Habibi, N., Sneyers, A., Stojetz, W., and van Weezel, S. (2016). The Relationship Between Food Security and National Security. Available online at: https://isdc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Food-Security-and-Conflict-2016-12-22.pdf (accessed December 2022).

Bruck, T., and Schindler, K. (2009). The impact of violent conflicts on households: What do we know and what should we know about war widows? Oxf. Dev. Stud. 37, 289–309. doi: 10.1080/13600810903108321

Buhaug, H., Benjaminsen, T., Sjaastad, E., and Theisen, O. (2015). Climate variability, food production shocks, and violent conflict in Sub-Saharan Africa. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 125015. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/10/12/125015

Burke, M., Hsiang, S., and Miguel, E. (2015). Climate and conflict. Annu. Rev. Econom. 7, 577–617. doi: 10.1146/annurev-economics-080614-115430

CESCR. (1999). General Comment No. 12: The Right to Adequate Food (Art. 11 of the Covenant). Available online at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/4538838c11.html

Das, T. (2022). Russia-Ukraine War: Trust and Distrust. Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4060599 (accessed January 2023).

Deutsche Welle (2022). EU to Set Up a Platform for Ukrainian Reconstruction. Available online at: https://www.dw.com/en/eu-to-set-up-a-platform-for-ukrainian-reconstruction-as-it-happened/a-62345352 (accessed January 2023).

Durisin, M., and Choursina, K. (2022). Warehouse Bombed, Tractors Stolen as Russia Strikes Ukraine food. Bloomberg. Available online at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-03-15/warehouse-bombed-tractors-stolen-as-russia-strikes-ukraine-food (accessed December 2022).

Emediegwu, L. (2022). How is the War in Ukraine Affecting Global Food Security? Economics Observatory. Available online at: https://www.economicsobservatory.com/how-is-the-war-in-ukraine-affecting-global-food-security (accessed December 2022).

EU (2022). Russia's War on Ukraine: Impact on Global Food Security and EU Response. Available online at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2022/733667/EPRS_BRI(2022)733667_EN.pdf (accessed December 2022).

FAO (2022). The Importance of Ukraine and the Russian Federation for Global Agricultural Markets and the Risks Associated With the Current Conflict. Available online at: https://www.fao.org/3/cb9236en/cb9236en.pdf (accessed: December 2022).

FAO (2022a). FAO Food Price Index rises to record high in February. FAO, Rome. Available online at: https://www.fao.org/turkiye/news/detail-news/en/c/1475695/ (accessed: December 2022).

FAO (2022b). Note on the Impact of the War on Food Security in Ukraine. FAO, Rome. Available online at: https://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/1492322/ (accessed: December 2022).

FAO IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO. (2020). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020. Transforming food systems for affordable healthy diets. Rome, FAO.

Gartzke, E. (2007). The capitalist peace. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 51, 166–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00244.x

Gessen, K. (2022). Was it Inevitable? A Short History of Russia's War on Ukraine. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/mar/11/was-it-inevitable-a-short-history-of-russias-war-on-ukraine (accessed December 2022).

Gowa, J., and Mansfield, E. D. (1993). Power politics and international trade. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 87, 408–420. doi: 10.2307/2939050

Grote, U., Fasse, A., Nguyen, T., and Erenstein, O. (2021). Food security and the dynamics of wheat and maize value chains in Africa and Asia. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 4, 1–17. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2020.617009

Hafeznia, M. (2006). Principles and Concepts of Geopolitics (in Persian Language), Mashhad: Popoli Publications.

Harvey, F. (2022). Ukraine invasion May Lead to Worldwide Food Crisis, Warns UN. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/mar/14/ukraine-invasion-worldwide-food-crisis-warns-un (accessed December 2022).

Henderson, E. (1997). Culture or contiguity: ethnic conflict, the similarity of states, and the onset of war, 1820-1989. J. Conflict Resolut. 41, 649–668. doi: 10.1177/0022002797041005003

Henderson, E. A., and Tucker, R. (2001). Clear and present strangers: the clash of civilizations and international conflict. Int. Stud. Q. 45, 317–338. doi: 10.1111/0020-8833.00193

Houngbo, G. (2022). Impacts of Ukraine Conflict on Food Security Already Being Felt in the Near East North Africa Region and Will Quickly Spread. IFAD, Rome. Available online at: https://www.ifad.org/en/web/latest/-/impacts-of-ukraine-conflict-on-food-security-already-being-felt-in-the-near-east-north-africa-region-and-will-quickly-spread-warns-ifad (accessed January 2023).

Hughes, J. (2022). The Ukraine crisis: A Problem of Trust. Available online at: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2022/01/27/the-ukraine-crisis-a-problem-of-trust/ (accessed January 2023).

Human Rights Watch (2022). Ukraine/Russia: As War Continues, Africa Food Crisis Looms. Available online at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/04/28/ukraine/russia-war-continues-africa-food-crisis-looms (accessed January 2023).

Husain, A., Greb, F., and Meyer, S. (2022). Projected Increase in Acute Food Insecurity Due to War in Ukraine. World Food Program, Rome. Available online at: https://www.wfp.org/publications/projected-increase-acute-food-insecurity-due-war-ukraine (accessed December 2022).

IFAD (2022). Impacts of Ukraine Conflict on Food Security Already Being Felt in the Near East North Africa Region and Will Quickly Spread. IFAD, Rome. Available online at: https://www.ifad.org/en/web/latest/-/impacts-of-ukraine-conflict-on-food-security-already-being-felt-in-the-near-east-north-africa-region-and-will-quickly-spread-warns-ifad (accessed January 2023).

Kelman, H. (2005). Building trust among enemies: the central challenge for international conflict resolution. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 29, 639–650. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.07.011

Kemmerling, B., Schetter, C., and Wirkus, L. (2022). The logics of war and food (in)security. Glob. Food Sec. 33:100634. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2022.100634

Koren, O., and Bagozzi, B. E. (2016). From global to local, food insecurity is associated with contemporary armed conflicts. Food Security 8, 999–1010. doi: 10.1007/s12571-016-0610-x

Kyiv School of Economics (2022). Direct Damage Caused to Ukraine's Infrastructure During the War Has Reached Almost $92 billion. Kyiv School of Economics. Available online at: https://kse.ua/about-the-school/news/direct-damage-caused-to-ukraine-s-infrastructure-during-the-war-has-reached-almost-92-billion/ (accessed December 2022).

Lake, D. A. (1992). Powerful pacifists: democratic states and war. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 86, 24–37. doi: 10.2307/1964013

Lake, D. A., and Rothchild, D. (1996). Containing fear: the origins and management of ethnic conflict. Int. Secur. 21, 41–75. doi: 10.1162/isec.21.2.41

Lynch, D. J. (2022). Oil Price Shock Jolts Global Recovery as Economic Impact of Russia's Invasion Spreads. The Washington Post. Available onlin eat: https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2022/03/11/oil-price-global-recovery-russia-ukraine/ (accessed April 2022).

Mankoff, J. (2022). Russia's War in Ukraine: Identity, History, and Conflict. Center for Strategic and International Studies, Washington, DC. Available online at: https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/220422_Mankoff_RussiaWar_Ukraine.pdf?tGhbfT_eyo9DdEsYZPaTWbTZUtGz9o2_ (accessed January 2023).

Margulis, M. E. (2013). The regime complex for food security: Implications for the global hunger challenge. Glob. Gov. 19, 53–67. doi: 10.1163/19426720-01901005

Martin-Shields, C. P., and Stojetz, W. (2019). Food security and conflict: empirical challenges and future opportunities for research and policy making on food security and conflict. World Dev. 119, 150–164. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.07.011

Masters, J. (2002). Ukraine: Conflict at the Crossroads of Europe and Russia. Council on Foreign Relations, NY. Available onlin eat: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/ukraine-conflict-crossroads-europe-and-russia (accessed January 2023).

Maystadt, J., and Ecker, O. (2014). Extreme weather and civil war: does drought fuel conflict in Somalia through livestock price shocks? Am. J. Agric. Econ. 96, 1157–1182. doi: 10.1093/ajae/aau010

Mercy Corps (2022). News Alert: Conflict Demolishes Ukraine's Agricultural Infrastructure Ahead of Critical Summer Harvest Season. Mercy Corps. Available online at: https://www.mercycorps.org/press-room/releases/Ukraine-war-agriculture (accessed June 2022).

Messer, E., and Cohen, M. (2007). Conflict, food insecurity and globalization. Food Cult. Soc. 10, 297–315. doi: 10.2752/155280107X211458

Messer, E., and Cohen, M. J. (2015). Breaking the links between conflict and hunger redux. Glob. Food Secur. Health. 7, 211–233. doi: 10.1002/wmh3.147

Miguel, E., Satyanath, S., and Sergenti, E. (2004). Economic shocks and civil conflict: an instrumental variables approach. J. Polit. Econ. 112, 725–753. doi: 10.1086/421174

Miller, R., and Wainstock, D. (2013). Indochina and Vietnam: The Thirty-five Year War, 1940–1975. Enigma Books: NY.

Nguyen, T. T., and Do, M. H. (2021). Impact of economic sanctions and counter-sanctions on the Russian Federation's trade. Econ. Anal. Policy 71, 267–278. doi: 10.1016/j.eap.2021.05.004

Nicas, J. (2022). Ukraine War Threatens to Cause a Global Food Crisis. New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/20/world/americas/ukraine-war-global-food-crisis.html (accessed April 2022).

OECD (2022). Prices: Consumer Prices: Updated: 6 December 2022. Paris. Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/newsroom/consumer-prices-oecd-updated-6-december-2022.htm (accessed January 2023).

Osborn, A., and Nikolskaya, P. (2022). Russia's Putin authorises “special military operation” against Ukraine. Reuters. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russias-putin-authorises-military-operations-donbass-domestic-media-2022-02-24/ (accessed June 2022).

Pettersson, T., Davies, S., Deniz, A., Engström, G., Hawach, N., Högbladh, S., et al. (2021). Organized violence 1989–2020, with a special emphasis on Syria. J. Peace Res. 58, 809–825. doi: 10.1177/00223433211026126

Polityuk, P. (2022). Ukraine 2022 Spring Crop Sowing Area Could be Halved. Reuters. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/exclusive-ukraine-2022-spring-crop-sowing-area-could-be-halved-minister-2022-03-22/ (accessed December 2022).

Reals, T., and Sundby, A. (2022). Russia's war in Ukraine: How it Came to This. CBS News. Available online at: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/ukraine-news-russia-war-how-we-got-here/ (accessed December 2022).

Reuber, P. (2000). Conflict studies and critical geopolitics -theoretical concepts and recent research in political geography. Geo J. 50, 37–43. doi: 10.1023/A:1007155730730

Rice, B., Hernandez, M. A., Glauber, J., and Vos, R. (2022). The Russia–Ukraine War is Exacerbating International Food Price Volatility. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute. Available online at: https://www.ifpri.org/blog/russia-ukraine-warexacerbating-international-food-price-volatility (accessed December 2022).

Rosato, S. (2003). The flawed logic of democratic peace theory. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 97, 585–602. doi: 10.1017/S0003055403000893

S P and Global Market Intelligence (2022). Data on Oil & Refined Products Prompt Month. Available online at: https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en (accessed December, 2022).

Saâdaoui, F., Jabeur, S., and Goodell, J. (2022). Causality of geopolitical risk on food prices: considering the Russo–Ukrainian conflict. Finance Res. Lett. 49, 103103. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2022.103103

Sambanis, N. (2000). Partition as a solution to ethnic war: an empirical critique of the theoretical literature. World Polit. 52, 437–483. doi: 10.1017/S0043887100020074

Sanín, F. G., and Wood, E. J. (2014). Ideology in civil war: Instrumental adoption and beyond. J. Peace Res. 51, 213–226. doi: 10.1177/0022343313514073

Simmons, B. (2005). Rules over real estate: trade, territorial conflict, and international borders as an institution. J. Conflict Resolut. 49, 823–848. doi: 10.1177/0022002705281349

The New York Times (2022). How the World is Seeking to Put Pressure on Russia. The New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/article/russia-us-ukraine-sanctions.html (accessed December 2022).

Ugarriza, J. E., and Craig, M. J. (2013). The relevance of ideology to contemporary armed conflicts: A quantitative analysis of former combatants in Colombia. J. Confl. Resolut. 57, 445–477. doi: 10.1177/0022002712446131

UN News (2022). War in Ukraine Sparks Global Food Crisis. Available online at: https://unric.org/en/war-in-ukrainesparks-global-food-crisis/ (accessed March 2022).

UNCTAD (2022). Ukraine War's Impact on Trade and Development. UNCTAD. Available online at: https://unctad.org/news/ukraine-wars-impact-trade-and-development (accessed January 2023).

UNHCR (2022). UNHCR Updates Ukraine Refugee Data, Reflecting Recent Movements. Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/ua/en/46035-unhcr-updates-ukraine-refugee-data-reflecting-recent-movements.html (accessed December 2022).

Valigholizadeh, A., and Karimi, M. (2016). Geographical explanation of the factors disputed in the Karabakh geopolitical crisis. J. Eurasian Stud. 7, 172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.euras.2015.07.001

Walter, B. F. (2003). Explaining the intractability of territorial conflict. Int. Stud. 5, 137–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1079-1760.2003.00504012.x

Welsh, C., and Dodd, D. (2022). Rebuilding Ukraine's Agriculture Sector: Emerging Priorities. Center for Strategic and International Studies. Available online at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/rebuilding-ukraines-agriculture-sector-emerging-priorities (accessed January 2023).

Keywords: food security, geopolitical conflict, interstate war, cycle of violence and hunger, international security system

Citation: Nguyen TT, Timilsina RR, Sonobe T and Rahut DB (2023) Interstate war and food security: Implications from Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7:1080696. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2023.1080696

Received: 25 November 2022; Accepted: 07 February 2023;

Published: 02 March 2023.

Edited by:

Gioacchino Pappalardo, University of Catania, ItalyReviewed by:

Zlati Monica Laura, Dunarea de Jos University, RomaniaMohammad Chhiddikur Rahman, Bangladesh Rice Research Institute, Bangladesh

Copyright © 2023 Nguyen, Timilsina, Sonobe and Rahut. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Trung T. Nguyen, dGhhbmgubmd1eWVuQGl1dy51bmktaGFubm92ZXIuZGU=

Trung T. Nguyen

Trung T. Nguyen Raja R. Timilsina

Raja R. Timilsina Tetsushi Sonobe

Tetsushi Sonobe Dil B. Rahut

Dil B. Rahut