95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Food Syst. , 17 April 2023

Sec. Social Movements, Institutions and Governance

Volume 7 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2023.1052298

This article is part of the Research Topic Diverse Economies and Food Democracy: Implications for Sustainability from an Interdisciplinary Perspective View all 11 articles

Against the backdrop of multiple crises within—and due to—the current industrial agri-food system, food is a highly political issue. As calls for food sovereignty grow louder and the war in Ukraine exposes the fragility of global food systems, the concept of food democracy calls on all (food) citizens to engage in a democratic and collective struggle for socially just and environmentally friendly food systems. To date, “Western” examples of food democracy and formal political procedures of civil society have dominated scholarship, ignoring the self-organized, low-key, and informal political activities around food in the post-socialist East. In this article, we shed light on the aspects of food democracy within Food Self-Provisioning (FSP) practices in Eastern Estonia, which is our case study. Our empirical data is based on semi-structured interviews conducted in 2019–2021 with 27 gardeners on their so-called dachas—a Russian term for a plot of land with a seasonal allotment house used primarily for food production. The analysis focuses on the food-, farming-, and nutrition-related attitudes and practices of the gardeners, as well as the multitude of collective endeavors to improve food systems. Despite the precarious socio-economic and political status of the gardeners, we identified a variety of subtle, informal, and mundane forms of democratic practices and everyday resistance. We investigate the interplay of these aspects along the three dimensions of food democracy (input, throughput, output). On the one hand, FSP on Eastern Estonian dachas encompasses essential characteristics of the mainly “Western” concept of food democracy, allowing access to and participation in agricultural production while preserving (re)productive nature in the future. On the other hand, we caution against excessive optimism and romanticization of such local food communities, as they tend to remain exceptions and risk extinction or displacement if they are not valorized and reshaped through public discourse. We conclude with a plea for building and strengthening alliances between the marginalized elderly rural food producers and the more youthful urban food activists to achieve more democratic, just, and ecologically sound food systems.

Amidst multiple crises within—and due to—the current industrial agri-food system, food has become increasingly political. It serves as a point of reference for experiencing, shaping and initiating transformation processes. Social issues such as equitable access to nutritious and healthy food remain one of the core issues of global food governance (SDG2), as do environmental concerns related to intensive agriculture, industrial livestock farming and carnivore diets. In addition to these socio-ecological aspects that have dominated critical discourses on food and agriculture so far, food has recently come to be perceived as an object and terrain of democratic practice. Subsistence farmers and smallholders are globally deprived of their land, seeds, and livelihoods while consumers face increasing alienation from their food base and limited opportunities to shape their own food-related systems. They are forced into a passive role, in which they can, at best, “vote with their forks” (Pollan, 2006) when choosing one market product over another. These developments have given rise to numerous counter-movements. Unlike the prevailing global “food security” programs that are implemented by the UN's Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and that most development agencies advocate, these counter-movements claim to address the root causes (rather than the symptoms) of current dysfunctions and crises. Thus, they demand either equal access to food (“food justice”), more autonomous food production (“food sovereignty”), or increased possibilities for all “food citizens”1 (Wilkins, 2005, p. 271) to shape food-related systems (“food democracy”) (Hassanein, 2008; Bornemann, 2022, p. 351).

The concept of food democracy was introduced in the 1990s by Lang (1998) in response to increasing corporate control of the food system and was further elaborated by Hassanein (2003, 2008). Central to the concept of food democracy is the idea that all people can (and should) participate actively and meaningfully in shaping the food systems that surround them (Hassanein, 2003, p. 79), and possess the know-how necessary to design socially just and ecologically sound alternatives. Ideally, food systems should provide everybody with the equal access and “means to eat adequately, affordably, safely, humanely, and in ways one considers civil and culturally appropriate” (Hassanein, 2008, p. 288). Food democracy contests the commodification of food and encourages “passive” consumers to become active food citizens who reclaim their influence, exert power, remodel, and improve the existing food system. As such, it seeks nothing less than to fundamentally and collectively reshape power relations in and around agri-food systems and to challenge the structure of capital, corporate control, and reckless profits of industrial agri-food systems (Hassanein, 2008, p. 289; Renting et al., 2012; Booth and Coveney, 2015).

Most forms of the alternative agri-food movement and AFNs (alternative food networks) originate from the Western context, or, increasingly, from the South (e.g., Thornton, 2020). However, as various scholars, including Müller (2020), Jehlička (2021), and Pungas (2023), have demonstrated, knowledge originating in the East,2 and alternative practices already in place there seem to be systematically overlooked. Furthermore, Sen (2006, p. 210) problematizes the “frequently reiterated view that democracy is just a Western idea” and that democracy is exclusively associated with the Western world and value system. Classic examples of food democracy in the Western scholarship include various formal forms of political activities or collaboration through food policy councils, food banks, food co-ops, Community Supported Agriculture (CSA), urban (community) gardening projects, as well as educational programs such as Farm-to-School, school-cooking and vegetable gardens in school yards (Carlson and Chappell, 2015, p. 6–7; Bornemann and Weiland, 2019, p. 109). Hitherto, most frameworks on food democracy case studies are consumption-oriented and have focused on one of these—“Western”—examples. Hassanein (2008), for instance, has extended the theory on food democracy by investigating qualitative and quantitative data in four dimensions of food democracy in Montana, US, that involved students, a CSA and a food bank. Lohest et al. (2019) explored the contribution to food democracy of three AFNs, including an organic shop brand, an online shop and a non-profit collaboration between organic farmers and purchasing groups in Brussels. Further case studies on food democracy include food policy councils in Germany and in the US (Sieveking, 2019; Berglund et al., 2021) and food sharing initiatives in Western European cities (Davies et al., 2019), among others.

Against this backdrop, we aim to shed light on the agricultural practices prevalent in the East. Food Self-Provisioning (FSP) at dachas during the Soviet era is the world's largest example of (peri-)urban agriculture in contemporary history and remains the most prevalent AFN example in the Global North (Brown, 2021). As a vivid agricultural practice in post-socialist Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), it deserves further scholarly attention with regard to its political dimension and potential, which we hope to contribute to by exploring the FSP practice through the lens of food democracy. FSP is most often understood as the practice of “growing and consuming one's own food using one's own (predominantly non-monetary) resources” (De Hoop and Jehlička, 2017, p. 811) that takes place outside the conventional agri-food system. However, FSP also encompasses various social practices of care, mutual aid, and gift-giving, as well as collaboration and deliberation processes, to name a few. The political dimension of these collective practices and processes will be of particular interest in this paper.

Our main research objective lies in exploring the extent and forms of food democracy in Eastern Estonian dachas. In particular, we are interested in the following aspects: (i) Which properties of food democracy are present and/or are being lived out? (ii) Which aspects are scarce or insufficient? (iii) What are the drivers and barriers to the democratization of food in such context?

This article is structured as follows. In the next Section 2, we introduce the concept of food democracy, apply it to FSP practice in Eastern Estonia, and explain its main features. In Section Case study and methodology, we describe our case study and its region-specific and socio-culturally relevant context and present our methodology and empirical framework. In the following Section 4, we will demonstrate and discuss our research findings and explore the existing and problematic/insufficient features of food democracy before concluding with a discussion in the final Section 5.

Lang (2007) basic premise of food as the center of democratic processes first evokes the question on what we mean by democracy. In this paper we use Pateman (2000, 2012) theory of participatory democracy, deep democracy as applied to urban agriculture by McIvor and Hale (2015), Barber's (2004) differentiation between thin and strong democracy and lastly, draw onto Mouffe (2000) understanding of democracy as a constitutive, “open” process. According to Pateman (2000), democratic values such as collaboration, openness and commitment to a common good can only be sustained if they shape citizens' daily lives. This stands in strong contrast to the “realist” and (neo)liberal notion of representative democracy, in which citizens contribute to democracy merely through their vote. Deep democracy, as described by McIvor and Hale (2015), implies a social form of interaction and collaboration in which citizens become agents of change rather than remaining mere subjects of the larger socio-economic or political structures that surround them (Wolin, 2008). According to McIvor and Hale (2015), deep democracy “requires processes by, and spaces within, which citizens can exercise some measure of control over decisions that affect their lives” (McIvor and Hale, 2015, p. 8). The everyday relationships and practices of ordinary people are thus both a space and a means through which they can “assume responsibility for addressing common challenges and pursuing collective visions” (Wolin, 1989, quoted in McIvor and Hale, 2015, p. 8). These understandings of democracy inform our exploration of FSP on the dachas through the lens of food democracy—the daily labor, commitment, and various forms of interaction constitute the foundation for food democracy on the ground. Another differentiation with regard to democracy is that of thin and strong democracy by Barber (2004). In contrast to “thin” democracy, which is based on an individualistic “rights” perspective with a limited role for citizenship, participation and civic virtue, in a “strong” democracy people govern themselves as citizens (instead of delegating the power and responsibility to representatives) and engage in a messy and relational work indispensable to collective action (McIvor and Hale, 2015, p. 7). Politics in a “strong democracy” is regarded as an essential part of life that plays a prominent and natural role and is characterized by regular engagement in decision-making processes (Booth and Coveney, 2015). Moreover, we understand democracy not only as a capacity but as a constitutive process of people (demos) to act collectively to bring about change as they assume agency and power (kratos) (Ober, 2007). Constitutive democracy then implies various collective processes of learning, exchange, and opinion shaping, in this case related to agri-food systems (Mouffe, 2000).

Based on these understandings (a participatory, deep, strong and constitutive), food democracy can (or even should) be an underlying element constituting one's daily way of living and shaping food-related interactions. As such, we aim to shed light on more invisible, quiet, and subtle forms of democratic practices around food that often take place in informal networks with covert forms of organization and coordination. We assert that in the daily interactions among FSP gardeners, there are a multitude of joint opinion-forming, negotiation, and decision-making processes that are political and can be viewed through the lens of food democracy. Our objective, therefore, is to make visible the political actions, implications, and overall potential within the everyday life of the dachniki and to explore the political dimension of the prevalent daily activities around food.

As various scholars such as Thelen (2011), Jacobsson (2015), and Jacobsson and Saxonberg (2016) have already noted, the search for such a civil society as is common in the “West” (consisting of associations and NGOs with formal memberships that organize visible protests with political demands, etc.), in the “East” will only reproduce the overly pessimistic views of “relative backwardness” (Stenning and Hörschelmann, 2008) and “understanding of political life in the [CEE] region in terms of absences, voids and deficiencies” (Rekhviashvili, 2022, p. 1). Jacobsson and Korolczuk (2020), in their study on the CEE civil society and grassroot movements, emphasize the importance of uneventful, low-visibility, low-profile and small-scale protests and covert resistance, the collective formation of agency and the process of becoming active in the public sphere (“political becoming”). They conclude that a “reassessment of post-socialist civil society is needed on both empirical and theoretical grounds” (Jacobsson and Korolczuk, 2020, p. 126). Císar (2013a,b) and Goldstein (2017) have argued that invisible struggles, “everyday discrete activism”, or “self-organized civic activism” are not only common but also highly rational in contexts where other forms of activism are ideologically or politically problematic, risky, or ineffective. Such “infrapolitics” (Scott, 1985) or “politics of small things” (Goldfarb, 2006) are less radical, more mundane and in many cases more likely to be organized in informal, spontaneous and fluid networks. As such, they pose a methodological challenge and require close knowledge of, and sensitivity toward the local context. However, to neglect these specific forms of civic activism and collective action simply because they do not correspond to “Western” forms of civil society due to the methodological and theoretical lenses used in the prevailing research would be highly problematic.

Eastern Europe is an important case for the study of food democracy, as between 30% and 60% of the population there grows and consumes a considerable amount of their own food (Smith and Jehlička, 2013; Church et al., 2015, p. 72), in comparison to, for instance, 6% in Denmark and 5% in the Netherlands (Alber et al., 2003, p. 11–12). Despite the initial framing of FSP as a “survival strategy of the poor” who “muddle through economic transition with garden plots” (title by Seeth et al., 1998; see also Shlapentokh, 1996; Humphrey, 2002), scholars have increasingly emphasized the wide spectrum of other motives and benefits of the FSP practice in the CEE (Jehlička et al., 2020) in general, and in Poland (Smith et al., 2015), Hungary (Balázs, 2016), the Czech Republic (Sovová et al., 2021), Croatia (Ančić et al., 2019), Baltic countries (Mincyte, 2011; Aistara, 2015; Pungas, 2019), and Moldova (Piras, 2020), in particular. In addition to various beneficial aspects for psychological and physical health, care for family members and good quality food, these agricultural practices (often including crop rotations with intercrops such as legumes, organic fertilization, composting, and green manure), have a positive impact on soil health and biodiversity, thus serving as an example of “quiet sustainability” (Smith and Jehlička, 2013) and “quiet food sovereignty” (Visser et al., 2015).3 “Quiet” in this context means that FSP gardeners do not advertise the environmentally beneficial aspects of their practice, and the small-holders in Russia studied by Visser et al. (2015) do not make explicit political claims, as does La Vía Campesina. However, the positive environmental impact and ideas of the global food sovereignty movement are still present, albeit rather implicitly. Similarly to these examples, we find it important to explore the full range of manifest food-related collective actions and activities in a region that, due to its past, is characterized by a very different political culture, democratic traditions, and civic culture than the “West”. Contrary to the dominant narrative of weak, passive, and donor-driven civil society in CEE countries that lacks social and political trust, and despite the absence of a multitude of formal forms common in Western examples of food democracy, we contend that regionally specific quiet, subtle, and informal forms of food democracy (such as exchange and cooperation, joint opinion formation, open discussion and negotiation processes) prevail and should not be overlooked.

Furthermore, if we apply the properties of democracy concepts mentioned above to the concept of food democracy, food democracy becomes a way of life in which the variety of everday practices substantially constitutes the political sphere of the object (“doing democracy” as well as “doing food” such as growing, preparing, consuming, organizing, coordinating, and sharing food). This adds to the various formal and visible forms of collaboration, decision-making, negotiation, and social change that are also present. Therefore, FSP on dachas in Eastern Estonia makes an interesting case study because the lives of gardeners revolve around FSP practices and are often entirely shaped by dacha gardens and daily food practices—at least during the respective gardening seasons (from April to September).

As a fairly broad concept, food democracy has been operationalized through a variety of criteria and theoretical frameworks. According to the most cited scholar on the topic, Hassanein (2008), food democracy is foremost about collaboration and collective action for the sake of food system sustainability, where individuals can design and govern their own food systems and their relationship to food (Hassanein, 2003). Further criteria of food democracy include the acquisition of knowledge, the exchange of ideas, the development of a sense of (collective) efficacy, and the contribution to the common good (Hassanein, 2008, p. 295). Other scholars have used additional dimensions to assess food democracy: Davies et al. (2019) have identified participation, the right to food, sustainability, and realignment of control as key dimensions. Lohest et al. (2019) have analyzed the exercise of food democracy in terms of the political, social, and economic power of food citizens and differentiated between practice (process) and performance (goal) of food democracy within their case studies. McIvor and Hale (2015) have asserted that lasting relationships, the display of power, and the cultivation of commons are conditions for a thriving “deep democracy” in urban agricultural initiatives.

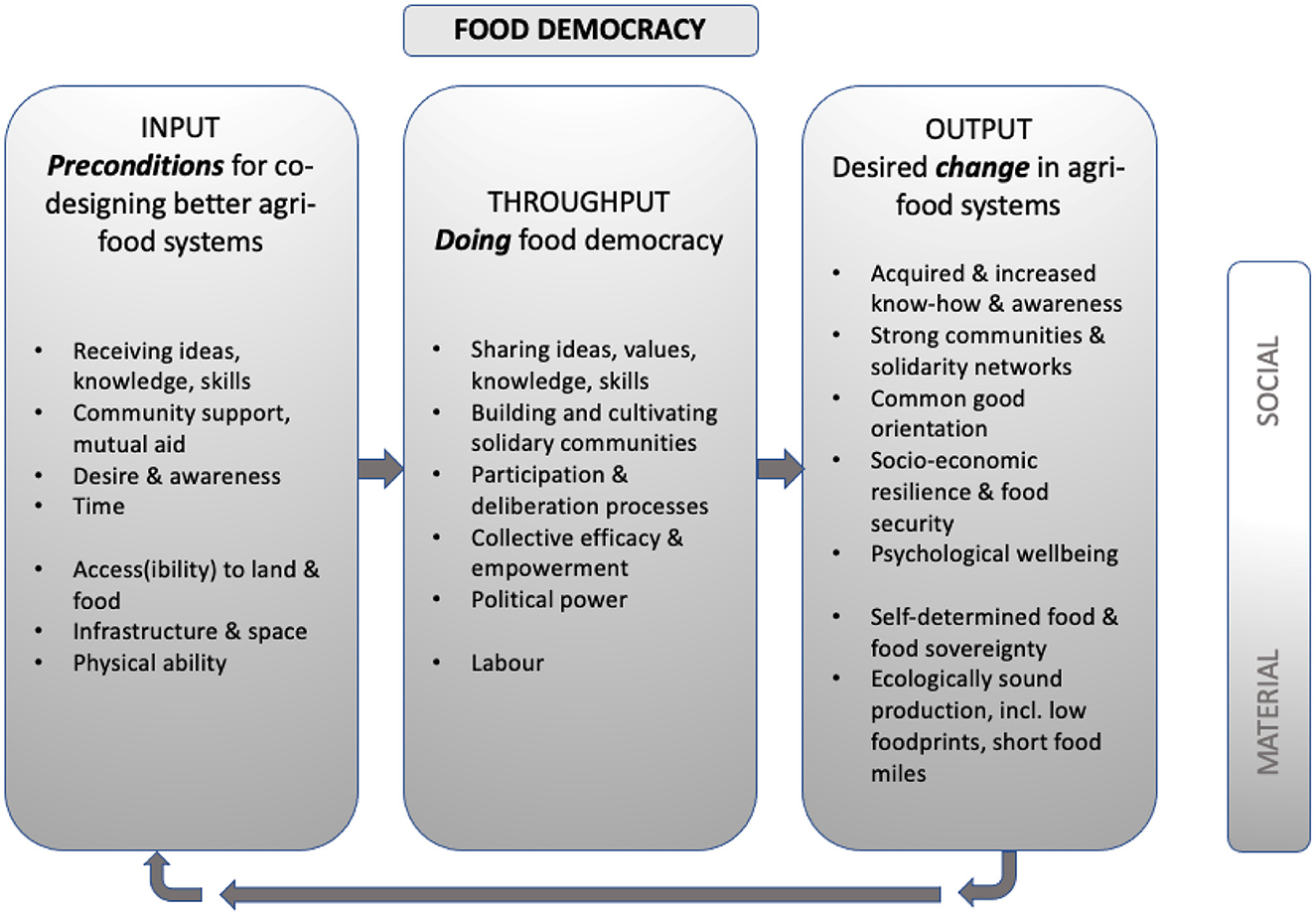

Drawing on Fraser (2019) work on democracy and justice, we join the scholars that differentiate between two aspects of food democracy (McIvor and Hale, 2015; Friedrich et al., 2019; Lohest et al., 2019). First, the procedural dimension of food democracy includes participatory processes leading to the creation of spaces for debate, negotiation, and protest, and is essentially a process of policymaking around food systems by (input) and with (throughput) citizens. Second, the substantive dimension of food democracy results in impacts on specific agricultural production modes or agri-food systems where food democracy has a goal (output/outcome) to transform food systems by addressing the problems created from imbalances in power (Bassarab et al., 2019; Friedrich et al., 2019). In this paper, we approach food democracy based on the concepts of participatory (Pateman, 2000, 2012), deep (McIvor and Hale, 2015) and strong democracy (Barber, 2004), and democracy as a constitutive process (Mouffe, 2000) and explore the case of FSP through this lens. Furthermore, we follow Bornemann's framework (Bornemann, 2022), which applies Schmidt (2013) system-theoretical concept of complex democracy, along with its three central features—the input, throughput and output dimension of democratic processes. As such, we add a third dimension—a precondition for food democracy as an input—to our analysis because we consider this dimension crucial within production-oriented frameworks. The three central features of food democracy are concretized as follows:

Input—understood here as the preconditions for codesigning food system—ability (e.g., know-how, time, physical condition), access(ibility) and infrastructure that empower and enable people to articulate interests, ideas and to participate, co-create, and design self-determined and preferred alternatives in relation to food systems.

Throughput—understood here as the doing of food democracy—procedural quality, transparency, and deliberative capacity in order to sensitize for, discuss, negotiate, develop and co-create alternatives, build coalitions as well as oppositions, raise collective efficacy, and coordinate strategies to balance or reshuffle existing power relations.

Output—understood here as achieving desired changes in the malfunctioning of the food system, or, alternatively, constituting alternative models (e.g., food security, sovereignty, low foodprints).

The dacha cooperatives and gardeners in Eastern Estonia are the subject of this article, as they still produce extensive amounts of fresh and healthy food through the practice of FSP without being “professional” farmers or smallholders. Instead, every household either has a dacha garden or at least access to one (through other family members or friends). This phenomenon has a complex socio-historical background which plays an integral role with regard to food democracy. Eighty-five percentage of the inhabitants of the Eastern Estonian county Ida-Viru represent a Russian-speaking minority, many of whom were resettled there during the Soviet era from thousands of kilometers away between 1950 and 1970 to work in the local industry (Raun, 1997, p. 336; Stat, 2021). As early as the 1970s and 1980s, local factories and state-owned collective farms (kolkhozes) started providing their employees with gardening plots on devalued state-owned land to guarantee food security and a more diverse food supply in a “shortage economy” (Kornai, 1980). After the collapse of the USSR, most dacha gardens in Eastern Estonia were privatized, and although gardeners remain members of the garden cooperative, they are now private owners of their gardens.

After regaining independence in 1991, Estonia enforced rigorous neoliberal economic reforms that disproportionately affected the Russian-speaking minority in terms of unemployment and poverty (Lauristin, 2003; Bohle, 2009; Pungas, 2017). Attempting to shake off the unwanted past, Estonia's political elite opted for “an intentional and complete break with the Soviet past and everything that reminds of it” (Lauristin, 2003, p. 610). This included socialist structures and institutions, but also norms of equality and solidarity (Bohle, 2009; Lauristin and Vihalemm, 2009) and culminated in the so-called Citizenship Act in 1992, which resulted in the loss of citizenship for the local Russian minority if they could not demonstrate the required level of Estonian language proficiency (Riigiteataja, 1992; Hughes, 2005; Järve and Poleshchuk, 2019). In 2020, Estonia still counted approximately 70,000 stateless citizens, many of whom live in Eastern Estonia (BNS, 2020). The reasons for this ongoing statelessness are manifold and, as various scholars have shown, not “black-and-white” (Vetik, 2012). Yet, what can be said with certainty is that many ethnic Russians have felt like “second-class citizens” since the 1990s (Lauristin, 2003) and have lost their political trust to a considerable extent (Hallik, 2006; Saar, 2007). Especially the elderly, who constitute the majority of the Ida-Viru population, have seen their knowledge and practices devalued throughout the last decades of neoliberal transformation and nationalist framing. Furthermore, as some scholars have argued, gardeners in this region experience a three-fold “peripheralisation” as they are located on the flip side of the respective urban-rural, center-periphery, and east-west divides (Sovová and Krylová, 2019; Pungas et al., 2022). These tensions have been further exacerbated by the war in Ukraine (ERR, 2022; Henley, 2022; Pungas and Kiss, 2023).

Against the backdrop of such socio-economic hardship and loss of social status and citizenship in the 1990s, dacha gardens played an essential role for many. Our interlocutors can be thus characterized by challenging socio-economic biographies, distrust of the (neoliberal Estonian) state, and at the same time a high degree of trust in the dacha gardens, which provided sustenance during difficult times. Both the FSP practices in the dacha gardens and the informal networks of mutual aid cultivated in the gardens were the main anchor for many dachniki in times of political and economic turmoil, and helped to maintain a degree of social trust. By contrast, formal infrastructures or state (aid) more commonly brought massive disillusionment. This socio-historical background of gardeners and the role of the dachas throughout history makes the FSP practice a particularly interesting yet challenging case to explore food democracy from within.

Moreover, our greatest concern is to shed light on dacha gardeners, not because the FSP practice is a vivid example of AFNs, but because gardeners—mostly elderly and part of the Russian-speaking minority—are seen as “passive and apolitical, unable or unwilling to engage in any collective attempts” and as such are disregarded as political actors with democratic agency. Similar to Leipnik (2015) observations in Ukraine, the elderly in East Estonia is portrayed as passive receivers of assistance and “as actors of a past epoch, ideologically at odds with the societal changes and political order” (Leipnik, 2015, p. 80), and their political views critical of neoliberalism, for instance, are in many cases delegitimized as a “Ostalgie” and de-politicized as “Soviet mentality”. Apart from the fact that some of the gardeners, as “stateless” citizens, cannot actually vote in parliamentary elections (and are thus politically “silenced”), they are not recognized as “real” civil society in Estonia. Rekhviashvili (2022) cautions against overwriting differences and divisions between groups mobilizing as rights-abiding citizens and those not recognized or treated as such by subsuming all identified everyday political activities under the concept of civil society. Instead, she proposes to differentiate between civil society as understood in Western scholarship, and Chatterjee (2004) concept of political society to account for a diversity of subaltern struggles deemed backward. The concept of political society by Chatterjee (2004) “explicates how this alternative terrain is marked by partial or tenuous citizenship and the recognition of some groups and populations who do not fit in modernization agendas yet are exposed to, and contest contemporary forms of governmentality” (Rekhviashvili, 2022, p. 14). This might also result in the depreciation of subaltern activism as passive and reactive self-help groups or mere not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) groups that mobilize politically only when they perceive an intrusion or threat to their own private sphere, and may reflect a de-politicization of their claims (Jacobsson and Korolczuk, 2020, p. 131ff). Therefore, and despite the methodological challenges of researching the political dimension of this specific target group, we aim to shed light on dacha gardeners precisely because their values and voices have in many ways been oppressed, silenced, or marginalized, for example, in comparison to the active urban and young activist volunteers in community gardens in Estonia's capital. Within such communities as dacha garden cooperatives, which are commonly perceived as resistant to change, passive, and atomized, many collective activities might be overlooked by researchers because they are perceived as unradical, apolitical, or irrelevant acts of everyday life. In many cases, however, they have important political implications and represent specific forms of resistance (Jehlička et al., 2019; Jacobsson and Korolczuk, 2020).

This article takes a qualitative approach and builds on semi-structured in-depth interviews conducted during field research in 2019, 2020, and 2021 in and around the Estonian city of Sillamäe (dacha cooperatives Sputnik and Druzhba) and Narva (various dacha cooperatives in Kudruküla, Olgina, and Kulgu) (Figure 1). In addition to interviews, the research included on-site participant observations at public and private events, photographic materials, and informal conversations with the gardeners documented with written field notes. We used a semi-structured interview guide4 developed during the initial field visit in 2019. A total of 45 interviews were conducted with 59 gardeners and relevant stakeholders (ranging from 10 to 180 min, mostly 45 to 90 min), of which 20 interviews with 27 gardeners were analyzed and coded for this article. Furthermore, we examined the meeting protocols (Sputnik, 2022) and the association statutes (Sputnik, 2019) of the largest garden cooperative Sputnik near Sillamäe with over 1,100 members and its own homepage (Sputnik, 2022). We further analyzed the local newspapers “Sillamäe Vestnik” (Vestnik, 1993–2017) and “Infopress” (Infopress, 2006) with regard to the issues raised by the garden cooperative members (mostly Sputnik) in Sillamäe.

Figure 1. The satellite photo (left) of Ida-Viru region between Sillamäe (on the left, right at the Baltic Sea) and Narva (on the right, at the Russian border) with the marked areas of dacha cooperatives (Sputnik, Druzhba) or their sites (Kudruküla, Olgina, Kulgu). A map (right) of the Sputnik dacha cooperative with over 1,100 garden plots.

The dacha garden cooperatives we visited are formally voluntary associations whose aim is to provide various services (e.g., security and certain infrastructure) to their members who own privatized garden plots. Despite having been cooperatives in the Soviet era until the privatizations in the 1990s, the legal term now is, roughly translated, “garden partnership” (садовых товариществo in Russian), as most garden plots are privately owned, but the common infrastructure is managed in “partnership”. However, since gardeners commonly refer to the “garden partnership” as a cooperative, we also use this term in this article. The gardeners are members of the cooperative and are invited to annual general meetings (AGM) and thus possess decision-making power on major issues affecting the whole cooperative (one garden plot = one member = one vote). Yet, democratic principles are not applied entirely, as the board plays a very strong role in decision-making in many cases. Thus, cooperative members are subject to a number of regulations, and experimentation with different types of decision-making and conflict moderation tends to be unwanted.

The interview partners represent a broad spectrum with regard to educational background (from highly educated engineers and civil servants to hairdressers, kindergarten teachers and mine pit workers), occupational status (in school, employed or retired), gender and age (see Table 1). However, older and female interview partners are over-represented at the dacha gardens and thus also as interviewees (roughly 2/3 each). We conducted interviews with both gardeners who have had gardens for decades and gardeners who have only recently become garden owners, as well as with cooperative chairs board members, and staff (e.g., security) to gain different insights into aspects of food democracy within the garden cooperative. However, the sample is not representative of the different dacha garden cooperatives across the nation (nor in CEE), as we only targeted dacha gardeners with a considerable quantity of produce in their gardens—the garden(er)s with a mere lawn and barely any garden beds are not represented in this study. In the garden cooperatives we visited between 2019 and 2022, ~2/3 of the gardeners use a considerable area in their gardens for food production and 1/3 for mainly recreational purposes. Therefore, it is acknowledged that the full spectrum of attitudes and activities associated with food democracy among dacha gardeners may not be reflected.

As food democracy is a highly complex phenomenon that encompasses an assemblage of cultural, political and biographical traditions, values, and beliefs, all of which are embedded in social (power) relations on the ground, it evades any simple categorization into a rigid set of properties that are easily tested or measured. For this reason, the semi-structured interviews focused broadly on (1) gardening practices, user groups and their motives, as well as collaborations and tensions within the cooperative, (2) the socio-economic, historical, and political context of the gardens and FSP practices in the respective region, as well as (3) the gardeners' concerns, views, and (emotional) perceptions of agri-food systems in general. Through these thematic foci, we sought to build an understanding of experiences related to the variety of themes relevant to food democracy as mentioned above. In doing so, we proceeded in an exploratory rather than comprehensive manner, and certainly did not capture the whole spectrum of this complex phenomenon, nor all political facets regarding food and FSP among dacha gardeners. In most cases, the interview subjects not only answered questions, but also raised and addressed new issues themselves, resulting in lively and stimulating dialogues. We did not specifically inquire about formal political participation, party preferences or democratic attitudes for two reasons: firstly, part of the respondents proved to be reserved toward what they perceived as “political” discussions or avoided these topics altogether. Secondly, our objective was to explore rather informal, self-organized and covert, “quiet” forms of everyday food democracy, related practices, activities and motives. In many cases, however, the issues that were initially avoided manifested themselves latently or emerged on their own accord in the course of the conversation. Most of the gardeners were approached in the gardens and not contacted in advance. In some cases, we obtained their contacts from media articles, neighbors, or the board of the cooperative.

The interviews were mostly conducted in Russian, recorded, transcribed, translated into English, and anonymized by the authors. For our qualitative analysis, we selected 20 interviews with 27 gardeners in which, according to our critical interpretation, gardeners actively raised issues and concerns linked to food democracy. Subsequent coding was done using MAXQDA according to the principles of content analysis (Mayring, 2010) and was guided by the concepts of deep, participatory, and strong democracy (as a constitutive process), as well as the suggested frameworks of Hassanein (2008) and Bornemann (2022). These theories and frameworks served us both as tools and as points of departure for the discussion on food democracy. They provided the initial main coding categories (e.g., input, throughput, output from Bornemann, 2022) and were complemented by additional (sub-) codes (e.g., social vs. material dimension) during the course of the qualitative content analysis. The results of our qualitative analysis of the found properties of food democracy can be seen below in our production-oriented framework (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Empirical framework as inspired by the work of Hassanein (2008) and Bornemann (2022), as well as by theories of participatory (Pateman, 2000, 2012), deep (McIvor and Hale, 2015), and strong democracy (Barber, 2004), and our empirical data.

Our empirical data has shown that several additional factors might be essential for food democracy on the ground. For instance, the material dimension of food democracy does not seem to be adequately addressed in previous empirical studies on the topic (Hassanein, 2008; Carlson and Chappell, 2015; Bornemann and Weiland, 2019; Sieveking, 2019; Bornemann, 2022), with the exception of Lohest et al. (2019), who emphasize economic power alongside social and political power. We have found that the material dimension (which is essentially embedded in unequal power relations) can enable or hinder food democracy, regardless of existing social aspects such as knowledge, participation or transparent and deliberative procedures. Therefore, we have distinguished between two different dimensions (social and material) of input, throughput, and output categories of food democracy. However, the respective categories are all hybrid. We are aware that by doing so we reproduce problematic dichotomies, but at the same time we consider it necessary to distinguish, for instance, between the social and material dimension in order to illuminate our reading of food democracy, which requires both the social dimension (for the sake of democracy/people) and the material dimension (for the sake of food/nature). Furthermore, some aspects of food democracy such as knowledge, skills, know-how, as well as solidary networks and strong communities seem to be essential for all “phases” of food democracy—they are indispensable as preconditions for food democracy, crucial for its process, and they constitute a desired goal of democratic food systems.

Through the analysis of our empirical data, the following preconditions for and properties of food democracy crystallized. We aim to demonstrate the variety of social forms from political demands, opposition and resistance to subtle, daily and mundane processes of collaboration, knowledge sharing and collective opinion formation. In addition, we draw attention to the material dimension, from access to land and food, physical ability to perform sustenance labor, to ecologically sound production, including low foodprint, short food miles, protected biodiversity and enhanced soil quality.

We understand “input” in food democracy as the variety of preconditions for codesigning food system(s). This includes the skills and ability (e.g., know-how, physical condition), access(ibility), and infrastructure that enables people to articulate their interests and ideas, participate, co-create, and design self-determined and preferred alternatives in relation to food systems. Our empirical data has shown that various factors have been found to be essential for food democracy as an “input”. As such, in the social dimension, we consider relevant preconditions to be (1) acquired knowledge and skills, (2) community support, and (3) desire/awareness and (4) time resources for active engagement. In the material dimension, we have found that (1) access(ibility) to land and food (e.g., logistics, public transport, or vicinity to the city), (2) certain infrastructure (e.g., electricity, water, space), and (3) physical ability and health conditions that enable gardening are equally important and should not be underestimated in their importance.

As several scholars such as Hassanein (2008), Jhagroe (2019), and Adelle et al. (2021) point out, knowledge and skills, both about food (or FSP) and “democratic” skills such as collaboration and tolerance, are essential prerequisites for food democracy. These skills are even more critical when larger quantities of food are produced organically that could meet a significant portion of a household's needs, as is the case in FSP practice. The extensive know-how is usually passed on from (grand)parents to new gardeners and generations, shared with neighbors or, more recently, acquired through television and discussed in various Internet forums: “We are talking about the use of various natural, popular remedies. And it goes from one generation to the next. The grandmothers pass it on to the children and then to the grandchildren. [..] And everyone knows that as soon as a caterpillar appears on a cabbage head, you need to treat it with a fruit vinegar.” (Oleg, gardener, Sillamäe)

In addition, community support, solidarity, sharing, and mutual aid plays an essential role. This is visible, on the one hand, in the form of the cooperative as an official structure that acts as a legal entity in the interest of the gardeners, and on the other hand, as a more informal community that shares and exchanges its seed(lings) and garden produce, helps with know-how and physical labor, or borrows tools. “With the cucumbers, we didn't pull the sprouts off, and then one time a neighbor [stopped by] and said, ‘what are you doing? You have to pull them off!'—and she cleaned our whole greenhouse, and that's how we slowly got into gardening.” (Magdalena, gardener, Sillamäe)

Finally, the desire (implying awareness) to consume “unprocessed,” “clean,” and “real” (all of these adjectives were regularly used by gardeners) food and provide it to one's family is a strong motive for many gardeners, and explains the willingness to invest a lot of time and physical labor in FSP practices: “We have a grandson—this year he will start school, he turned seven. I don't want him to eat from the shops, I want him to eat clean [produce]” (Vlada, gardener, Sillamäe). This desire is also manifested in the strong need to be in nature, to engage with it and have “fingers in the soil”, as has already been demonstrated by various scholars (Zavisca, 2003; Sharashkin, 2008; Ančić et al., 2019; Pungas, 2019; Sovová, 2020).

However, the desire can only “emerge” when there is enough time to spend at the dacha garden. This, in turn, counters the perceived alienation from nature (and feeds the desire for “organic” food). The temporal aspects become often evident in younger generations who seem to only want (or have time for) the “shashlik, rest, trampoline, pool”, as noted by an older gardener (Lyudmilla, gardener, Sillamäe). Many gardeners cited the time factor as the main reason why most people could not practice FSP “properly” or spend more time in their gardens, or why FSP would not generally be applicable for most people. Considering that retired people have more (free) time, it is also not surprising that most of our interview partners were elderly, as they were mostly the ones working in the gardens with vegetable beds. In contrast, younger generations tend to have recreational areas in the garden with fruit trees, berry bushes, flowers, and herbs that do not require much labor. As one gardener told us, “I thought about planting less so I could rest. Because the youth around us, everyone around us, all rest, only I work. But they have small children that don't allow them to spend time on the garden” (Tania, gardener, Sillamäe). Another gardener commented, “Especially the younger ones have only the ‘green zone'.5 It is us elderly who are busy [with the gardens].” (Anushka, gardener, Narva). The amount of time that the most diligent gardeners invest almost daily (~2–6 h) would be unimaginable for people with full-time jobs in the city and possibly also with caregiving responsibilities for family and children with which they already struggle.

Material access to (and affordability of) the land (including aspects of ownership and property) (or alternatively sufficient material resources or economic power to purchase healthy food) are essential preconditions for food democracy. The land does not need to be private property of the gardeners, as long-term warranties and affordable (or free) leasing can equally contribute to the flourishing of alternative food systems such as FSP, as the case of Eastern Estonian dachas has shown throughout history. Beginning in the 1960s, factories around Narva, Sillamäe, and throughout the Ida-Viru region began providing 600 square meter garden plots to their employees virtually free of charge to provide food security and “meaningful and active” recreation. In the 1990s, these garden plots were converted into a private property, which the former tenants bought for a more symbolic monetary value or vouchers. “Back then [1961], there was [..] a shortage of vegetables, fruits, and throughout the Union [USSR] the [so-called] consumption program was announced. And they started giving 600 square meter garden plots” (Anna, gardener, Sillamäe).

However, when such food gardens are not in private hands, the exchange value of peri-urban areas suitable for FSP often exceeds its use value. This is especially the case in areas around larger cities and capitals, where purchasing (or even leasing) a large enough area for FSP would be unthinkable for most urban residents without some support from city authorities, such as supportive regulations or subsidies. As a result, FSP practices must compete with rising real estate prices around urban centers and are subordinated to more profitable land uses such as capital-intensive commercial or real-estate development projects (Pungas et al., 2022). For instance, the creation of new FSP garden plots and community projects around the capital city Tallinn would counter unfavorable conditions and leasing prices. In fact, in many cases, community garden projects in the capital have become mere placeholders for real estate investments (Benjamin, 2020; Pungas et al., 2022), forced to leave as soon as a new real estate project is in the pipeline.

This is different in Ida-Viru county, which tends to suffer from rural exodus (Leetmaa, 2020, p. 28). In addition, the peri-urban areas around Narva and Sillamäe also do not have a high exchange value because the cooperatives were established on the swampy wasteland. Although the prices of garden plots have been steadily increasing, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, most residents already owned their garden which they had inherited or bought in advance to the rising prices. A board member of the cooperative reflects on the meaning of the garden plots after the land privatization: “The laws are different, the lifestyles are different. But the land remains” (Oleg, gardener, Sillamäe). The plots are still rather affordable in their respective regions and are extremely common in Sillamäe, as Oleg explains: “And in our town like, almost everyone has a dacha” (Oleg, gardener, Sillamäe). However, the private status of dacha gardens could also potentially have negative aspects, as gardens (and what is grown there and how) are generally considered a private matter (see also Jehlička et al., 2019, p. 8). This, in turn, could encourage the isolation of some gardeners, rather than determining and designing food production together with the community as a whole. Despite this potential “susceptibility” to individualism and atomization, formal and legally binding regulations and protracted collective discussions on food production would most likely be met with skepticism, though for understandable reasons—the negative experiences with the state collectivization of farms in the Soviet era have left a stain on anything declared formally “collective” (Jacobsson and Korolczuk, 2020).

However, not all dachas are privately owned—in Kulgu, many illegal dacha gardens are located directly under high voltage lines (see Figure 3). The gardeners have secretly and gradually appropriated the empty wasteland for their own food growing purposes and have managed to mobilize community support in Kulgu to ensure that their gardens continue to be tolerated by the land owner. These collective actions of occupying wasteland and maintaining it as one's own do not make newspaper headlines and are not motivated by ideological values other than common sense and the implicit understanding that the land belongs to the ones who cultivate it. This practice demonstrates how covert political agency and resistance (e.g., against the negative experiences of mass privatization in the 1990s) can be undertaken, even though the formal means may be lacking.

Figure 3. Illegal dacha garden plots with green houses (left), potato fields (middle), and dacha allotment houses (right) in Kulgu, which have been tolerated for decades by the municipalities as well as the electricity company, which owns the land under the high voltage lines (photo by the author).

Since the gardens are located only a few kilometers from the city of Sillamäe or Narva, they can be reached by the dachniki either on foot, by bicycle or via a free bus line. This is an important requirement in terms of logistical accessibility (with regard to affordable and needs-oriented transportation and vicinity to the city). As in many cases in Estonia the “typical” summer houses or farms are located far away from the cities, and are often only accessible for the urban population by their own car on weekends and holidays, the vicinity of the garden plots, which allows daily accessibility (e.g., for watering) by public transport and/or by bicycle, should not be taken for granted: “Yes, 20 minutes by bike from home, or there is a free bus. It has been done well here. [..] The bus goes there in the mornings and takes people back in the evenings. For free. Very convenient. Our city hall provided us with it as a present” (Tania, gardener, Sillamäe). The accessibility and vicinity of the gardens also enables regular contact and interactions with nature and food, and counters the increasing alienation of urbanites from surrounding more-than-human nature (described as “nature gap” by Schuttler et al., 2018). It enables parents to bring their small children easily to the dacha gardens of their grandparents or stop by after a working day themselves. All that fosters regular as well as emotional connection with nature and food also among urban population and from a very young age.

Another material prerequisite for FSP as an alternative food production is the infrastructure in and around the cooperative—the roads, electricity, (potable and irrigation) water, canalization and space for meetings. Although the respective infrastructure has improved significantly, there are still massive investment deficits and challenges ahead to which the cooperatives as legal entities contribute significantly by representing the interests of gardeners vis-à-vis the city on the municipal level. The city of Narva has employees in the city council who are responsible for negotiating and coordinating different infrastructural modernization projects with the boards of all cooperatives. As almost every inhabitant in the region either owns a dacha garden or is otherwise connected to them, the city cannot afford politically to set aside the interests of the garden cooperatives, despite lacking financial resources. In most cases, the agreements on major investments distribute the costs between the cooperative and the municipality, thus gradually improving the needed infrastructure for food producers. Furthermore, most garden cooperatives own certain common space for community to gather—a cooperative house with seminar rooms, and/or an area for outdoor events. These common spaces serve as a material prerequisite for different formats of deliberative processes.

Last but not least, physical abilities and a suitable health condition are an indispensable precondition for actually growing food and doing all the strenuous and regular physical labor. As such, FSP practices literally shape gardeners' bodies, and rhythms of their everyday life—to a much greater extent than, for instance, consumers who opt for a green organic label when purchasing food at the local super market.

We have defined the throughput of food democracy as a procedural feature of doing food democracy. This involves the quality of democratic processes around food systems such as transparency and inclusiveness, as well as deliberative capacities in order to sensitize for, discuss, negotiate, develop, and co-create alternatives, build coalitions and oppositions, increase collective efficacy, and coordinate strategies to balance or reshuffle existing power relations. At the heart of the food democracy process is the power of the community to collectively address food-related concerns and develop alternatives through a variety of different interactions, including dialogues, joint value formation and decision-making processes, collaboration, solidarity, and mutual support (social dimension). These interactions occur at different levels—between family members, households, neighbors, cooperatives, and city administration. We also assess the processual aspects of physical, mental, and emotional labor of food production and preparation.

Sharing know-how, experiences, ideas, and values with regard to food (systems) is essential for food democracy as it strengthens the “democracy” aspect. According to Hassanein (2008, p. 290), people in general make better decisions for themselves and others when they regularly and collectively engage in such conversations. In the case of FSP, food is often the topic in most of the dacha gardeners' interactions with family, neighbors, friends, and visitors. Savoring and cherishing delicious homegrown food together while sharing knowledge, culturally specific delicacies and recipes, and discussing the socio-cultural aspects of food is common practice.

One gardener tells us about gardeners paying each other visits on evenings and weekends (Yevgeniy, gardener, Sillamäe), showing vibrant solidarity networks, in which the community aspect is crucial, although the gardens are not called “community gardens”. Sharing is a daily practice among most gardeners and involves seeds, seedlings, and manure in the spring, tools and car transport to the city in the summer, and garden produce, juicers, and culinary takeaways from their own kitchens in autumn. As Patel (1991) noted, sharing helps stimulate friendships and creates a pattern of reciprocity and social interactions that foster trust. One gardener describes the coordination of mutual help between neighbors as a shared sense of purpose in the cooperative:“The neighbors help us out, opening our greenhouses [in the mornings]. We don't come early, we come a bit later, and [..] if we leave without closing them, they will close them for us” (Inna, gardener, Narva). Such solidarity networks for the common good with regard to the food system are essential for food democracy, according to Hassanein (2008).

Various forms of participation and processes of deliberation, negotiation, decision-making, and conflict resolution constitute an essential procedural part of food democracy within different communities. In our case study, formal negotiations and inquiries took place mainly in the cooperative meetings (we analyzed the minutes of the AGMs of the Sputnik cooperative), but also through processes such as collecting signatures for certain collective goals, e.g., a free bus service between the cooperative and the city, voicing political demands in the local newspaper (e.g., Sillamäe Vestnik), or strategically organizing support for votes of no-confidence (e.g., writing articles in local newspapers to mobilize opposition to the non-transparent behavior of the Sputnik cooperative's chairman, see, for instance, Karnaihov, 2016). Whilst some cooperatives, especially the smaller ones, seem to have more informal structures, meetings, and joint celebrations (see Figure 4), the biggest cooperative Sputnik, with over 1,100 garden plots, has one official AGM where each member has equal voting rights (“one member, one vote”). However, in the cooperative's day-to-day operations, the board takes most of the important decisions, while the AGM approves the annual budget and action plan. Despite these formal participation processes and the legal distribution of power, some gardeners seemed to lack trust and patience or understanding for lengthy collective processes such as AGMs: “Nothing was decided, just chatter” (Karolina, gardener, Sillamäe). Other gardeners were dissatisfied with regard to the cooperative board and felt that their needs were not taken seriously: “We are not listened to! If we were listened to, things would have been different. Like, we need water here in the summers, they give us no water. And now, in the fall, they give water. [..] It is decided for us. For some reason. [..] It depends on a chairman—the previous chairman, he walked in such boots, over the knee rubber boots, in winters and summers, he was worried. [..] The new chairman [..], little use” (Pavel/Nadia/Jelena, gardeners, Sillamäe). The “over-the-knee rubber boots” refers to a chairman who was physically present in the cooperative, ready to support the gardeners with their day-to-day challenges with construction, sewage, and similar problems, and who did not think he was any better (in comparison to the new chairman sitting behind the table with a stack of papers, as we were told). In contrast to the formal democratic procedures, which were met with less satisfaction and participation from the cooperative members, the smaller and informal formats (e.g., different actions with neighbors and acquintances from the cooperative such as joint apple juice making, mutual help in repairing an elderly widow's fence, car sharing, or women's singing and cooking group) seemed to thrive all the more according to the gardeners. It seems that “voluntary” informal communities provide a strong supportive network for most gardeners, whereas the formal cooperative with its implicit hierarchy and complex (and potentially not comprehensible) decisions remains a rather mistrusted institution.

Figure 4. The photo on the left shows an article written by a chairwoman of a garden cooperative in Kudruküla, near Narva, about environmental hazards (e.g., illegal waste dumping in nearby forests, as seen in the newspaper photo) and environmental consciousness and citizenship. The photo on the right gives a glimpse of the memories of annual midsummer celebrations of the same small cooperative in Kudruküla.

According to Hassanein (2008), the process of building self-efficacy (Zavisca, 2003), as well as experiencing a sense of collective efficacy, is essential, both with regard to the personal relationship to food (the ability to determine and obtain the desired produce), as well as, optimally, with some impact on the food system in general, for instance, through engagement with community food concerns (Hassanein, 2008, p. 290, 300–301). As for the more subjective sense of self-efficacy in the case of the FSP practice, this is significant both materially (e.g., tangible garden produce contributing to a sense of (food) security) as well as psychologically (self-reliance, autonomy, and as a satisfaction of having accomplished something meaningful, e.g., “sense of autonomy” as in Zavisca, 2003). Collective efficacy (or lack thereof) is best exemplified by the negotiations that the cooperative (board) regularly engages in with the city administration, for instance, on financial support for cooperative infrastructure (e.g., roads or sewage systems) or on regulatory protections. This remains a challenge, as the dacha cooperative areas are not recognized as residential areas and as such are not protected by regulations (e.g., from the proximity of polluting industry or highway construction, both the case in Sputnik), nor are they automatically entitled to new electricity lines, sewage systems, or other expensive infrastructure projects. In some cases, the cooperative board does not have sufficient power to protect the interests of the gardeners, as the chairman of one cooperative told us. During the drought in 2018, for instance, the following happened: “The factory is also taking water from there [the river], apparently. And we had no water, can you imagine? Had to water in the greenhouse, everything was burning [due to the heat]. [..] I turned to the city management, and I was told that the industry has priority” (Vlada, gardener, Sillamäe). Due to the non-residential status of the dacha gardens, economic power elites from the local industry, for instance, are not obliged to take into account the needs of the gardeners, in such manner diminishing the gardeners' ability to “reshuffle” existing power relations. This conflict mirrors the previously voiced discontent by one family (Pavel/Nadia/Jelena) about the water shortage in the cooperative during summer heat, and points to the lack of sufficient or transparent communication within the cooperative.

Despite the unfavorable status of a non-residential area, there were massive protests in 2012 against the construction of the new Tallinn-Narva highway. Forms of activism involved lengthy meetings between various cooperative groups, complaints, and formal inquiries to the city council, negotiations with different administrative units, and self-organized collections of signatures. As a result, 3,776 of about 13,000 residents (including children) in Sillamäe signed a letter to the local administration demanding a bypass instead, because they were concerned about pollution of the gardens (and their food production) and traffic noise (Vestnik, 2012a,b). Nevertheless, the new highway was built and the gardeners' concerns were brushed aside. However, the mobilized opposition demonstrated the willingness of thousands of Sillamäe residents to engage in overt political resistance and opposition, defending their vegetable gardens against the proximity of a new polluting highway.

As Leipnik (2015) and Jacobsson and Korolczuk (2020) state, these specific political resistance phases and motives are often devalued and de-politicized as mere protectionist measures by NIMBY or “self-help” groups, according to which the elderly are only concerned about their own survival and act as “service providers” instead of publicly challenging neoliberalism. Yet who decides what intentionality, motives, and awareness are “legitimate” or “suitable” to frame political resistance and opposition as such? Why should resistance and struggle against something perceived as threatening to one's existence (such as the dacha gardens in this case) be anything other than a highly rational, legitimate, and political motive? Scholars have found that in many cases that initially looked like self-help groups concerned with their own wellbeing, the activists were actually practicing citizenship, engaging in “the politics of small things” (Goldfarb, 2006), and forming pluralistic spaces (Goldstein, 2017). Leipnik (2015, p. 86ff) has explored in Ukraine further examples of collective efficacy and control among dacha gardeners who self-organize and successfully coordinate logistics around volunteers guarding their dacha cooperatives in the off-season for crime. Such self-organized civic activism is, according to Císar (2013a,b), the most common form throughout post-socialist Europe and is usually mobilized without the involvement of formal organizations, associations, or the like, making it invisible in most cases.

The last essential aspect, however, is that of political power, as Lohest et al. (2019) refer to it with regard to food democracy. As most of the gardeners belong to the Russian minority in Estonia and some of them lost their citizenship status in 1992, they lack a basic democratic political voice and power in parliamentary elections. Such a context, which additionally involved the “rapid economic and symbolic downfall of large social groups, who almost overnight became the ‘post-socialist leftovers' accused of inability and unwillingness to adapt to the capitalist order” (Hryciuk and Korolczuk, 2013, quoted in Jacobsson and Korolczuk, 2020, p. 135), resulted in massive frustration with everything that was condemned as political, and is now associated with dirty business, corruption, and unkept promises. Similar to what Jacobsson and Korolczuk (2020, p. 130) described as common among CEE activists, most dacha gardeners explicitly distanced themselves from party politics and drew strict boundaries between politics and the everyday “real” problems on which they resolutely placed their focus. To our surprise, one of the gardeners emphasized several times that the people in Sillamäe are “actually very literate”, and after our inquiry, she explained, “People often talk about it [that people here can't read and write]. As if we are not like others, retarded” (Grusha, gardener, Sillamäe). Together with her friend, she told us afterwards that “[this] starts now already in the schools. ‘You are Russian—you are not Russian'. No need to do so. [..] They [politicians] want to divide people [..] Divide and rule!” (Anna and Grusha, gardeners, Sillamäe). As such, general disillusionment and distrust in politic(ian)s are widespread in Eastern Estonia and have been exacerbated by half-hearted integration politics, politically instrumentalized polarization in the last three decades (Braghiroli and Petsinis, 2019; Makarychev, 2019; Lang et al., 2022), rural exodus (Leetmaa, 2020, p. 28), controversial and emotionally charged debates over the regional oil shale industry (well-paying jobs for locals vs. phasing out a polluting industry, see Michelson et al., 2020), over COVID-19 politics, and now in relation to the war in Ukraine—which is perceived very differently by many local Russians in comparison to Estonians.

In our interviews, we also encountered explicitly anti-political and depoliticized attitudes, many of which also seem to have resulted in a certain disillusionment after the collapse of the USSR and due to increasing polarization: “One is almost in despair when one sees how far apart people are in the assessment and understanding of the situation. The separation goes through the whole society—through friends, relatives, colleagues, partners etc. [..] The first time in my life, I feel I need to simply withdraw into the private [to the dacha]” (Jana, gardener, Sillamäe). This shows the delicate and ambivalent role of the dacha—it can serve as a terrain of collective engagement for better food systems and at the same time provide an escape to a private sphere where politics is taboo and everything revolves around marmalade recipes (see also Jehlička et al., 2019, p. 8f). Some respondents reflected almost nostalgically on the Soviet past and seemed accustomed not only to universal welfare guarantees (such as employment and housing) but also centralized power as the political “norm”. On these grounds, the aversion to formal (possibly inadequate) democratic structures within the dacha cooperative, and the increasing passivity and reluctance toward public and organized forms of politics are probably the most problematic aspects of this specific form of food democracy in Eastern Estonia and caution against romanticizing Eastern Estonian dacha cooperatives as role models of food democracy.

We consider the material manifestation of food democracy as a process to be primarily the strenuous physical (but also mental and emotional) labor. Within FSP practice, gardeners engage in physically exhausting and often daily labor—this demonstrates the extent to which their lives are shaped by the cultivation of different food products in their daily practice. If food democracy is not only about reshaping power relations in corporate agri-food systems, but also building alternatives, then this is what the dacha gardeners do on a daily basis. The labor involves not only gardening (e.g., sowing seeds, raising seedlings, watering regularly, harvesting, tending the soil), but in most cases also food preparation and conservation for the winter. Although it is “hard labor”, “nobody wants to refuse [it]. Because not only is it one's own, but also it is something that is deep inside. It is most likely soul [and comes] with great physical effort” (Oleg, gardener, Sillamäe). Such labor is meaningful and rewarding (“active leisure” by Zavisca, 2003), and differs significantly from alienated wage work, as one gardener further explained to us. However, the time commitment to gardening is immense. One elderly woman told us that if she worked 8 h a day, she produced a sufficient amount of food for herself and her family.

We have defined the output of food democracy as the achievement of desired change in relation to food system dysfunctions, and/or, alternatively, the creation of alternative models (that encompass food security, sovereignty, low foodprints, and more). Contrary to Bornemann (2022), who emphasizes the effectiveness and role of institutions and governance, we aim to highlight various other forms of social change that might be overlooked by focusing only on formal and institutional forms of governance and cooperation. Therefore, we focus on the multitude forms of informal collaboration, trust-based networks and governance forms that can also be collectively binding, as well as material aspects such as short food miles, low foodprints, self-determined healthy and nutritious food.

However, a desired output is simultaneously also the same that is needed as an input to continue practicing food democracy—knowledge, skills, access(ibility) to the land, necessary equipment and seeds, because the functioning food systems must also be guaranteed for the future. In the framework, this is depicted with an arrow, illustrating that food democracy is always a dynamic, evolving, circular process, but never a static object. With this regard we join Jacobsson and Korolczuk (2020) who suggest to conceptualize civil society as a “process of building relations and achieving collective goals, rather than a stable object of research or a structure that can be fully captured by quantitative measures” (p. 139).

Acquired and/or increased knowledge and skills are a desired output of food democracy. In the case of FSP, gardeners receive the necessary knowledge through childhood gardening experiences, from family members or neighbors—informal ways of knowledge transfer seem to prevail within the FSP practice, as most gardeners told us.

Another desired goal of food democracy, awareness of the ecological limits and negative externalities of the dominant industrial food system, also seems to be increasing through the process of FSP and lively exchange, as exemplified by the board member of one cooperative: “You know what, the only thing I want to say is that on the big farms one cannot manage without pesticides. And this is very harmful. [..] Anything that is big, it cannot manage without pesticides. You won't go around sprinkling vinegar or soap or ash. You must use pesticides. The pesticides, well [..] the residues are staying.. Where? In the soil. Thus…” (Oleg, gardener/board member, Sillamäe). However, awareness of the negative externalities of “big business” does not automatically translate into an overt opposition to large agri-food systems in general. This corresponds to the findings of Leipnik (2015), Mamonova (2015), Visser et al. (2019), Jacobsson and Korolczuk (2020), and Pungas et al. (2022), who have shown that opposition in post-socialist civil society might be more cautious and often perceived as not “radical” enough (with regard to anti-capitalist or anti-corporate attitudes) compared to their Western counterparts. Yet this is understandable in a context where the left can be associated with the socialist past immediately. For instance, Visser et al. (2015, p. 14) observe that the “quiet food sovereignty” in Russia “[...] does not challenge the overall food system directly through its produce, claims, or ideas”. The reasons for quite strong individualism, further reinforced by political disillusionment, are manifold and originate in the stigma of collectivism as a legacy of the socialist experience, but also in a “preference for individualist or market-oriented problem-solving strategies as well as individualistic notions of agency, which were strongly supported by the post-socialist economic transformation” (Jacobsson and Korolczuk, 2020, p. 129). However, this does not mean that there is no political discontent, resistance to the current agri-food system, or self-organized alternatives to be found. In many cases, they are either more covert, or they simply do not explicitly challenge and publicly condemn the global capitalistic order along with agri-food corporations as a whole.

Community along with strong support networks are emphasized by Hassanein (2008), Eng et al. (2019), and Lohest et al. (2019) as essential to food democracy. Gardening helps create a sense of home, belonging, and rootedness in a specific community, while shared food “glues” this specific community together. Relationships within the neighborhood contribute to a fair and generous yet informal distribution of food, mutual aid, and cooperation. As a community, they can collectively address various food related concerns and have an impact on the surrounding food system. One chairwoman of the board told us how she regularly organizes and coordinates solidarity collections of garden produce within her cooperative for a nearby elderly home: “My daughter works in Narva in the retirement home and there are 150 babuschkas [grandmothers in Russian] and djeduschkas [grandfathers], an old people's home. We very often collect excess vegetables [for them].” (Ivanna, gardener/board, Narva).

As producers and consumers either overlap or interact regularly in such communities, the recognition of the hard and skilled labor on the producers' side leads to a crucial shift from “farming as merely the selling of raw materials to the food industry to an activity that revalues and reincorporates various elements of food provisioning in a wider social and political meaning” (Renting et al., 2012, p. 290). This then not only results in a subjectively perceived high value of organic and local food, but also bridges the rift between rural producers and urban consumers in the sense that the urbanites are “forced” to engage with agricultural aspects that they would not otherwise be exposed to in the supermarket. This reinforces a spatially and socially close(r) relationship between producers and consumers (as advocated by prosumer approaches, CSAs, etc.) and increases other benefits of food democracy such as esteem, high regard, and trust toward food produce(rs) (Lohest et al., 2019).

As scholars such as Hassanein (2008, p. 291), Petetin (2014, p. 5), and Behringer and Feindt (2019, p. 125) emphasize, (orientation toward) the common and community good is another desired goal of food democracy. Concern for the common and community good means that people, as food citizens, are willing to go beyond their self-interest, consider the wellbeing and needs of the community, and recognize its entanglement and interdependence with their own wellbeing (Hassanein, 2008, p. 291). This also includes respecting and taking action to protect the ecological boundaries of food systems. By “community good”, Hassanein (2008) refers to all more-than-human-nature as understood by Leopold (1989). Therefore, concern and engagement for the surrounding natural environment manifest themselves in caring and respectful relationships with the more-than-human-nature as well, contributing to the overall ecological sustainability of food systems. One cooperative board member told us of her frustration with people who dump their garbage in nearby forests (instead of paying some fees to bring it to official garbage collection points): “They come and throw. I'll show you later, I even wrote an article (see Figure 4). I'll show you later how the garbage is thrown. People still cannot think with their heads at all” (Mashenka, board member/gardener, Narva). Mashenka engages in educational work in her cooperative about various hazards of such behavior and apparently imposes “strict regulations” within her own cooperative. In addition, the generosity toward strangers who stop by in the garden cooperatives is also common, as one gardener explains: “I give away in buckets. When we had an excursion from Tallinn passing by [..] I drove them around whole Sputnik. I brought them apples [..] to the bus” (Grusha, gardener, Sillamäe).