94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Food Syst., 16 June 2022

Sec. Agroecology and Ecosystem Services

Volume 6 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.872751

This article is part of the Research TopicScale, Diversity, and Inclusion in Agroecology, Organic Farming, and Regenerative AgricultureView all 5 articles

Collaboration between farmers and other farm support professionals is a critical tool for food systems transformation. Collaborative research and outreach can address structural inequalities that limit the success of immigrant and minority growers and uplift farmer knowledge, which has been systemically valued below that of academic knowledge. Agroecologists who work at the synthesis of science, movement, and practice propose wisdom dialogues and horizontalism as principles by which to develop collaborations that avoid reinforcing structural inequalities due to race, gender, and traditions of valuing academic knowledge above that of farmers. Public entities, such as land grant universities and state agencies, have a particular responsibility to address structural inequalities and serve the diversity of farmers in their region. This study examines the use of collaborative learning processes, such as wisdom dialogues and horizontalism, by public and non-profit professionals in their collaborations with a group of immigrant farmers in the Upper Midwest. We used a qualitative interview approach with two farmers, two of their advisers, and eight of their collaborators at the University of Minnesota Extension, Department of Agriculture, and a local agricultural non-profit. Through the interviews we examined each of their perspectives on current and potential collaborations by discussing the motivations, resources, and effects for and of collaboration between immigrant farmers and farm support professionals. Farmer interviewees emphasized that collaborations between immigrant and non-immigrant individuals and groups must develop with non-exploitative motivations and preparation undertaken by non-immigrant individuals to better understand the experience of immigrant farmer prior to engaging in collaboration. Emergent themes from interviews with non-farmers included a strong commitment to providing access to knowledge and resources, and recognition that collaboration improved the ability to accomplish institutional goals, indicating use of wisdom dialogues and horizontal learning at varying levels within current work. Interviewees emphasized that institutional support was an important determinant for how much they could prioritize relationships and collaboration in their work. Based on interviewees' experiences, support and continued opportunities for learning are critical to facilitate continued use of wisdom dialogues and horizontalism to address different conceptions of equity and equality, and for developing intentional and mutually beneficial collaborations.

Food systems worldwide are in urgent need of transformation to address structural inequalities and achieve resilience and abundance. Collaborations between farmers and farm support professionals, through research and outreach, can be a means to achieve beneficial outcomes by addressing the conditions that limit the success of immigrant and minority growers and uplift the knowledge of farmers. In Minnesota, many immigrant farmers have historically had limited connections with researchers or other public food system entities but have built new connections with some of these farm support professionals in recent years. The recent development of these relationships is an opportunity to learn about the perspectives of the farmers who engage in them, and the attitudes and practices of public university Extension and government agency collaborators who have built these relationships, in order to guide future collaboration.

Society asks farmers in the 21st century to manage their farms to produce abundant, sanitary, and nutritious food while concomitantly supporting ecosystem function and operating as an economically viable enterprise (Garnett et al., 2013; Hunter et al., 2017). This is a huge task, and one that farmers should not be expected to accomplish on ingenuity alone. However, efforts to address these complex, interrelated priorities should honor farmer expertise and wisdom. One opportunity to develop knowledge across types of expertise is through sustained collaboration between farmers, academics, and other food systems professionals.

Integrated projects in which academics collaborate with non-academic stakeholders have become more prevalent in recent years under the auspices of participatory and engaged scholarship (Boyer, 1990; Driscoll and Sandmann, 2001). The connection between academic and non-academic knowledge in agriculture has traditionally taken place under the auspices of Land-Grant University (LGU) Extension programs. The Extension system has a contested history (Peters, 2013), in which its main functional role has been as a technical expert system to share scientific information from academia with farmers (Heleba et al., 2016). However, that position has changed significantly over time, and there are currently efforts to re-think the relationship between research and farmers broadly (Warner, 2006), and to reconsider the historic and future role of Extension in such relationships (Peters, 2014).

Key aspects for how to reimagine the role of Extension include proposals to re-orient the land grant mission toward broader public accountability, to focus on democratic engagement and in agricultural contexts, on the development of robust, multi-sector networks that promote social learning. Social learning is distinct from the knowledge-transmission model of Extension which has been extensively critiqued (McDowell, 2001). However, some see the Extension system as a possible hub facilitating broad collaboration and democratic participation in the process of knowledge co-creation and exchange (Warner, 2006). These reorientations have also been more broadly conceptualized in progressive visions of the LGU mission in the 21st century, which defines public accountability as ensuring accessibility, relevance to rural and urban demographics, and focusing on sustainability and social justice (Goldstein et al., 2019).

Proposals to re-think extension programs and the public role of LGUs are part of the broader international agroecology movement. While a contested term, agroecology as a transdisciplinary endeavor seeks to connect farmers, food systems activists, and researchers through integration of the biophysical, social, and political factors in agroecological systems (Altieri, 1987; Wezel et al., 2009). Agroecologists using participatory approaches specifically recognize that farmer expertise is a critical component in developing more sustainable agroecosystems (Pretty, 1995; Van de Fliert and Braun, 2002; Berthet et al., 2016; Lacombe et al., 2018). It is also a practical means to allow non-farmers to connect their expertise to the knowledge-sharing networks through which farmers get most of their information (Kroma and Flora, 2001).

Knowledge-sharing and knowledge co-creation in agroecology are facilitated by principles of horizontalism and diálogo de saberes, or wisdom dialogues (Anderson et al., 2018). Horizontalism rejects hierarchical transfers of knowledge in favor of peer-to-peer level learning that builds capacity and expertise simultaneously. Wisdom dialogues entail sharing cultural capital, or wisdom, across different groups, thereby building social capital within the larger, combined group (Gutiérrez-Montes and Aguero, 2016). Putting wisdom in dialogue is to engage in respectful appreciation of others' perspectives, and to share one's own wisdom in the process, thereby building collective wisdom. Wisdom dialogues can be farmer-to-farmer, such as farmer field schools in the Mesoamerican Agroenvironmental Project (Gutiérrez-Montes and Aguero, 2016), or can be applied to sharing knowledge across the researcher-farmer divide as is taking place across a diverse set of projects in Europe (Anderson et al., 2018).

Horizontalism and wisdom dialogues are a means to uplift silenced voices, and to provide for “emergent discourses” outside of traditional knowledge production regimes (Martínez-Torres and Rosset, 2014; Anderson et al., 2018). Emergent discourses refer to the possibility of new ways to view the world that would not be possible without the unique perspectives offered by participants in the process. The creation of space for emergent discourses enables alternative models of research that may be more appropriate for engagement with historically marginalized communities. Examples of alternative ways of knowing come from indigenous models of research, which emphasize relational ways of knowing (Hart, 2010). A relational orientation is built on trust, which has been demonstrably important for successful co-management of natural resources (Stern and Coleman, 2015). Trust can also provide space to explore mutual benefit and reciprocity, which have been key in developing community-based participatory research projects (Jordan and Gust, 2010). Wisdom dialogues can also facilitate shared control and leadership (Lacombe et al., 2018), reflexivity (Finlay, 2002), and development of robust and flexible participatory processes (Lyon et al., 2010).

An approach to building collaborations with farmers using wisdom dialogues and horizontal learning presents a renewed opportunity to address persistent gaps in traditional models of extension and outreach in academia and government. Historically, both academia and the USDA have failed to fulfill their stated missions in interactions with farmers who are not traditionally mainstream. At best, extension and outreach programs have insufficient capacity to address concerns that are not easily defined by traditional disciplines within scientific and technical terms (Peters and Wals, 2013). However, extension and outreach programs have also explicitly sought to disempower and disenfranchise farmers (Scott and Barnett, 2009) based on production practices (Barbercheck et al., 2012), race, gender, or immigration status (Herren and Edwards, 2002; Minkoff-Zern and Sloat, 2016). These conditions have contributed to broader structural barriers for immigrant and minority farmers, who are more likely to have farms with less fertile soil because of historically limited accessibility to land and capital (Sullivan and Peterson, 2015; Minkoff-Zern, 2017).

One of the main mechanisms to upend inequities faced by immigrant and minority farmers are non-profit organizations that focus on land access and beginner farmer trainings. Throughout the US, non-profit farmer training programs have been important spaces to value immigrant and minority farmer experience and provide them with the tools to be successful farm operators in the USA. For example, the Agriculture and Land-based Training Association in California “creates opportunities for low-income field laborers through land-based training” with a focus on facilitating farm ownership (ALBA, 2022). Similar farm incubation programs in Minnesota (Big River Farms) and New England (New Entry Sustainable Farming Project) focus on providing land and training for new entry farmers (New Entry Sustainable Farming Project, 2022; The Food Group, 2022). These programs are in contrast to other organic agriculture initiatives, farm internship programs, and local food initiatives, which have been criticized for failing to upend structural racism and inequity (Slocum, 2007; Guthman, 2008; Etmanski, 2012; Cadieux et al., 2019; Levkoe, 2019).

While non-profits have demonstrated success for supporting immigrant and otherwhile marginalized farmers, the historical failures to connect with multiple types of these farmers has resulted in extension and government outreach systems that many immigrant and minority farmers do not see as resources or potential collaborators. In the Upper Midwest, a survey of Hmong and Hispanic farmers indicated that only 2–7% of these farmers would turn to an Extension agent or university entity for advice about farming practices (McCamant, 2014). In the Mid-Atlantic region, the growing population of Latino farmers rarely participates in USDA financial assistance programs due to the lack of legibility that their production systems have within the regulatory framework of the USDA programs (Minkoff-Zern and Sloat, 2016). A horticultural Extension needs assessment from the University of Minnesota in 2019 found it difficult to reach immigrant farming populations (Klodd and Hoidal, 2019), which may have been due to insufficient alternative language and format outreach.

Non-profit models have worked to fill the gap left by insufficient public investment in collaboration with immigrant and minority farmers, and have made significant impact by facilitating land access and collaboratively building knowledge with historically marginalized farmers. However, the existence of these programs does not negate the responsibility of public institutions to invest in relationships and collaborations with immigrant growers. Many non-profit programs are geared toward beginning growers; these growers have continued support needs after graduating from beginning farmer programs, and the persistent gaps between these farmers and public agencies such as Extension and state agriculture departments can perpetuate the disparities that immigrant growers face. These disparities include limited investment in interpretation and translation in relevant languages, limited research and support for non-Euro-centric crops, and policies that are not rooted in racial justice. For example, a report on Farm to School programs in Minnesota found that immigrant and other minoritized groups face additional hurdles to accessing markets, despite clear potential benefits from them doing so (Olds et al., 2019). It is therefore clear that the force of good intentions and theoretical commitments to wisdom dialogues and horizontal learning are insufficient and that public entities have work to do to develop collaborative relationships with immigrant and minority farmers. As has been proposed in the literature comparing how food sovereignty and food justice are used in academia, more clarity is needed on what it looks like to “do” the work (Cadieux and Slocum, 2015).

On-the-ground descriptions of collaborations, as well as reflections on the collaboration process, can be a critical part of the type of action research that is advocated for as a necessary part of agroecology (Méndez et al., 2016). Part of the action research process is the cultivation of a reflective practitioner's posture, which entails self-reflection and critique of one's participation, thus expanding agency for change (Reason and Torbert, 2001; Torbert, 2001). In turn, that space (physical, financial, mental) for reflection and for cultivating the skills and practical resources necessary to develop horizontalism and wisdom dialogues, which requires a certain set of resources. In the following case study, we propose to address two related questions that reflect on the collaboration process: (1) How do a pair of farmers and their advisers view collaboration and the necessary factors to make them successful; and (2) What perspectives and reflections do non-farmer collaborators bring to collaboration, and where are there opportunities for continued growth?

In 2016, the primary author participated in a Minnesota Department of Agriculture Specialty Crop Block Grant funded project to explore summer cover crops with Latino vegetable farmers. The project was designed as a collaboration between university researchers and a cooperative of Latino farmers, but largely hewed toward conventional knowledge-transmission models of extension, with one of its goals being to “Provide research-based information to specialty crop producers regarding the benefits of legume cover crops in rotation with vegetable crops and extend this information to immigrant farmer communities” (Minnesota Department of Agriculture, 2022).

By implementing this largely traditional research project in an on-farm setting, the project became slightly more collaborative, and during the project, the primary researcher and the farmer collaborators repeatedly discussed how future projects could be better developed to foster more horizontal knowledge sharing and to prioritize long-term collaborative relationships. The author was a graduate student at the time, and upon completing the project, there were questions about how the grower collaborators could remain connected to the University in the absence of the specific relationship with the author. The farmers in the cooperative repeatedly stressed the importance of long-term collaborations to the success of farmers, because of the potential for long-term interaction and access to resources that such collaboration can facilitate. The grower and researcher both recognized that some of the more robust opportunities for sustained collaboration might be found through Extension and through engagement with government entities. Therefore, a follow-up interview-based project was developed to elaborate on the approaches and mental habits that government and academic representatives have when working with individuals from the farming cooperative, both to inform future research collaborations as well as provide information for non-research practitioners.

We first present perspectives from the two main farmer collaborators from the cooperative, on what they found most important in their collaborations. From their priorities and previous literature on farmer-research-action collaborations, we use the concepts of wisdom dialogues and horizontalism as principles by which to evaluate the experiences and perspectives of the non-farmer collaborations recommended by the farmers. In doing so, we turn the focus onto the non-farmer side of the collaborations to examine their orientation to collaboration, learn from their successes, and to build upon that knowledge to suggest important growth areas to facilitate future collaboration.

The data for this study come from 12 interview of 35–65 minutes each. Individuals in the case study are either farmers in a cooperative (2), direct advisers to the cooperative (2) or farmer support professionals (8).

The first set of interviews were open-ended conversations with two farmers and two advisers of a cooperative to which the farmers belong. The second set were semi-structured interviews with farm support professionals identified as current or potential collaborators with the farmers in the cooperative, all of whom had experience working with immigrant farmers in Minnesota. The second set of interviews used a set of questions focused on aspects of collaboration or potential collaboration with immigrant farmers. Interviewees were chosen based on farmer recommendations and then extended to their colleagues; despite the small sample size, the interview group represents most of the current collaborative relationships that the growers have had with state and university entities. The interviewees not associated with the farming cooperative are employed by the University of Minnesota (5), Minnesota Department of Agriculture (2), and a non-governmental organization (NGO) (1).

Semi-structured interviews afford individual interviewees the opportunity to express their opinions and mental habits, while maintaining comparability across multiple interviews (Adams, 2015). In the semi-structured-interviews, interviewees were asked about their (and their organizations') goals for collaboration, their role in such collaborations, and what they perceived as probable consequences of not collaborating with these farmers. Additional questions touched on the resources and capacities that individuals or organizations had to collaborate with farmers, and how collaboration has or could change the practice of their work as it relates to the future of vegetable farming in the Upper Midwest (Table 1).

All interviews were recorded and transcribed using an automated transcription software services (Sonix, 2020; Temi, 2020). Subsequently, the primary author reviewed all transcriptions with the original audio and made necessary corrections. Transcriptions were analyzed for emergent themes related to collaboration and for the semi-structured interviews, for each of the questions. Emergent themes were concepts that were repeated across multiple participants, both in agreement and disagreement. A resulting draft manuscript describing the results was shared with all interviewees and all were invited to provide further insight. Multiple interviewees responded with insightful comments, and the second author helped to shape the narrative and framing of the final paper.

In the results, we introduce each of the main emergent themes under the topics of Goal, Effects, and Resources. We then discuss how these themes build on existing knowledge about how to collaborate with farmers, especially those who have been systematically marginalized, and how lack of training and resources limits the effectiveness of that work. We close with reflections and recommendations for those looking to build sustained collaboration with minoritized farmers.

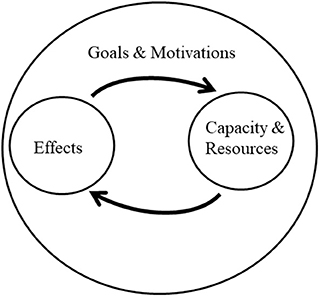

Interviews with farmers, their advisers, and farm support professionals, demonstrated that the effects of collaboration were in a reciprocal relationship with the capacity and resources to engage in collaboration, with each reinforcing or attenuating the other. Importantly, the goals and motivations for collaboration formed a basis onto which that reciprocal relationship was built, and thus affected the effects, capacities, resources, and the relationships among them (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Visual representation of the relationship between the capacities and resources that non-farmers have and the effects they hope to or can achieve. Goals and motivations form the backdrop onto which effects and resources mutually reinforce one another. Wisdom dialogues would be most impactful at the level of goals and motivations, thus changing the context in which effects and resources exist and affect one another.

Non-farmer interviewees indicated that their goal, both when collaborating and engaging with immigrant and minority farmers generally, and the farmers of the cooperative, in particular, is to facilitate access to information and resources. An additional goal highlighted by the NGO employee and an Extension professional was to facilitate a space for co-learning between farmers. While the goal of accessibility was universal among interviewees, individuals varied in how they conceived of accessibility. One conception of accessibility focused on the broad range of resources within the organization, and making sure that the largest possible number of farmers had access to that knowledge:

My goal, in a very basic sense, is [that] there's so much information out there that can help farmers that they don't currently have access to, and so I want to help them get access to information that they need to be successful, whatever that means to them.

This goal was highlighted by one of the farmers, who hoped that collaboration with Extension would mean that “all the information that the university has can get to the farmers, which is what creates trust”. As discussed further below, trust emerged as a key component of successful relationship building.

A second approach highlighted by the farmers and non-farmers alike centered on more intentional collaboration that valued farmer knowledge and learning preferences. The move beyond information sharing more clearly allows for horizontalism and wisdom dialogues. To build a more horizontal process, one interviewee articulated the importance of carefully identifying and thinking through which farmers to focus on; considerations here included geographical diversity, farming techniques, styles, and approaches, crops grown, cultural nuances, racial diversity, and other localized forms of marginalization. Beyond considering the various forms of diversity, the interviewee was adamant about the need for appropriate motivations and active follow-through in collaborations and improving access for the aforementioned groups:

For me what is really, really, important [in my organization] is to make sure that we have very fair and balanced equity in our approach, and in the services that we provide, and in making sure that all Minnesota farmers receive the same level of access, but also resources…And first of all, a lot of people talk about diversity, and having diversity in this and diversity in that, and sometimes, to be frankly honest, I think folks really just want to check a box… It's one thing, which is good, for us to make sure that we recognize [multiple forms of diversity] and want to make sure that everybody is at the table, but what are we doing to make sure that those groups can actually participate at the same level and be provided with whatever resources they need to allow them to participate at that level?

The same interviewee strongly advocated that collaboration alone was not a sufficient frame. Rather, it was necessary to have “intentional collaboration”, a phrase that was echoed by another interviewee from a different organization.

For multiple interviewees, intentionality was linked closely with compensation. The focus on remuneration was echoed by other interviewees who specifically mentioned that grant funding had improved their ability to work directly with farmers because they had written farmer compensation into the grant budget. In describing one collaborative project, the interviewee equated that payment with their impression that the farmers felt respected:

I tried to make it like we were equal partners and I used grant funds… I mean, I crank our thousands of dollars out the door to them, so I feel that they felt really respected in the process, so that was good.

Furthermore, multiple interviewees pointed out that collaboration could be a burden on the already busy lives of farmers, and that they had taken care to collaborate with farmers in ways that fit within farmer priorities and schedules. One interviewee provided a specific example of collaboration in which they created a farmer advisory board for a curriculum design project. Farmers invited to join the board were not asked to write anything or attend specific meetings, but instead were asked to be on call for questions that came up during the project. At the same time, interviewees stressed that collaboration was more appropriate and would be more successful at providing access if farmers were involved in collaborative projects as early as possible, not just when the information was being disseminated.

While interviewees primarily sought to collaborate in order to increase farmer access to knowledge provided by their organizations, they also sought to support and facilitate spaces for co-learning. For some interviewees, this goal was connected with the effects of their work, in that collaboration could build trust with farmers and thus facilitate future outreach opportunities. This was illustrated by an interviewee who connected mission accomplishment and trust-building back to the horizontal information-sharing that other interviewees indicated to be a goal of their work:

The more we're able to build trust with them, and the more comfortable they feel coming to us, then the more information that they're able to share with their communities and potentially put those people directly in touch with us… we're meeting our goals because we've got accurate information flowing out into communities.

The interviewee emphasized that connecting with a single farmer could result in broader outreach than the individual connection might suggest. Each individual connection could be an effective strategy to promote co-learning opportunities among networked farmers, and to provide multiple farmers with resources, even if the collaboration only happened with one person.

One of the farmers also stressed the importance of knowledge sharing, not just knowledge extension, for future collaboration. In describing the type of agency he would like to work with, he described it as “a program that really says, ok, we're going to try to work together, and we will take the best of what you know and the best of what I know and combine it”. This sentiment was echoed by a farm support interviewee who recognized that language barriers could sometimes limit this type of knowledge sharing:

[The farmers] are probably more knowledgeable than you are. It's just that there's a language barrier. That is an easy fix. So, let's figure out how we can go through the language barrier, and you will realize that indeed they are extremely knowledgeable and you can learn from them.

Other interviewees also acknowledged that language barriers could limit their ability to learn from farmers, and therefore appropriate motivation to overcome these barriers was a key priority.

Farm support interviewees consistently reported that collaboration with immigrant and minority farmers increased their ability to accomplish the organization's mission. All interviewees have farmer engagement as part of their work, and each indicated that they were better able to accomplish that mission by collaborating with farmers. One interviewee, who had recently started in their position, expressed this sentiment as being dependent on building trust with collaborators, while also acknowledging that their organization had not always been a trustworthy collaborator:

If no one is trusting the work that we're putting out, we're not really doing anything; we're not really achieving any public benefit. I think there's a general trend in the world that people are changing the way that we trust authority and people are moving away from this idea that just because [an authority] said it, it must be true. We tend to trust more anecdotal information and the people around us, and I think that's fine. I still really believe that research and the process of research is really important to how we understand the world, and I see that the more that we can involve people in that process and allow people to feel empowered in that process, and like they have some say in that process, the more we maybe can build trust in institutions and in research. I know that that has not always been merited, and that [institutions] have done things that have not been in the public interest and that have harmed communities, but I think that by involving people in that research process, we hold ourselves accountable, and we also achieve more public good.

This statement highlighted the potential connections between research opportunities and the long-term, non-research focused relationships that the farmers in the cooperative have with interviewees. By connecting the research process to other forms of engagement, the interviewee expressed a desire to build trust across multiple types of knowledge and expertise. Building trust was also highlighted by one of farming cooperative advisers, who mentioned that “It's not easy to find immigrant farmers in rural areas and even if they have a desire [to work with you]; they will not show that they have that desire because of a lack of trust.” For many immigrant growers, a lack of trust has limited past engagement with the university and state entities. One farmer gave an example of a typical interaction that they had experienced which eroded their desire to work with state entities:

For example, say I go into your office, and you don't pay attention to me, or you just take my name and never call me. Or, if I meet someone and they say, “oh, there's no one here who can help you, leave your number”, but then they don't call, or [they say] “we don't speak your language” or “we can't do anything”. This is what it's like. For me, that's like, ok, they aren't interested in helping me.

For this grower, past experiences had made him particularly passionate about reminding non-farming professionals that they would need to earn the trust of immigrant farmers, many of whom had stories like his.

Non-farmer interviewees echoed the sentiment that building trust through collaboration was key to organizational success because it made farmers more likely to engage with the organization, and they recognized that past conduct by their organizations might need to be overcome to facilitate new relationships. As part of that work, interviewees mentioned that in the process of building trust, they needed to adjust their job activities and, in multiple cases, actively participate in the community without expecting to accomplish any of their role-specific goals. Examples of this type of engagement included attending cultural celebrations, regular meetings of two major farmer-to-farmer networks in the state (Land Stewardship Project and Sustainable Farming Association), farmer-focused conferences, and an annual farm-to-school barbecue.

While interviewees felt that building collaborations with farmers of all kinds was critical to the future of their organizational missions, they also expressed an understanding that their choice or desire to collaborate and participate in less traditional outreach model was not universally accepted:

I would say this style of engagement is the future, but there's still plenty of other people in the world who just want to see the [return on investment] on how our time and money is spent. And so figuring out how we could express that concept of outreach and engagement in a way that really does make sense to everybody because, it's not something that people who maybe are not fans of the government [would like]. It's not something that everybody sees the need for.

Negotiating the negative perceptions of collaborative engagement was an important aspect of the interviewee's work, and for many, this pushback related directly to perceived capacities and resources, as discussed below.

While many of the interviewees expressed personal goals and motivations to engage in meaningful collaborations that embrace the tenants of horizontalism and wisdom dialogues, their capacities and resources limited their ability to carry out this work. Interviewees consistently noted the importance of structural support for collaborative, relationship-focused work. However, each person felt different levels of support ranging from none, to passive encouragement, to active support, and perceptions of support varied among members of the same institution (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Types of support as detailed by interviewees for conducting collaborative work with immigrant and minority farmers.

The main types of support highlighted by interviewees include practical considerations like time, funding, and scheduling flexibility, as well as more abstract concepts such as a supportive internal culture and understanding the logistics of how to do collaborative work. While interviewees varied on the extent to which they felt supported, none indicated that institutional conditions fully prevented them from engaging in this type of work. One interviewee described the difference between official policy and how the relationship with their supervisors affected the actual process of their work:

We're not supposed to be one-on-one. That is also most exclusively forbidden…[but] I say, pay attention to the results, let me deal with the process… and that's what's happened. So [my supervisor] has basically said, whatever you're doing, keep doing it. So I really appreciate that. I mean it's amazing, we have no oversight. So in that way it's good, [but] if you're new, that's hard, because you have very little mentorship.

On the other end of the spectrum, members of one organization emphasized that their unit was actively supportive of collaborative and relationship-based work that focused on immigrant farmers and valued their knowledge:

One of the reasons that I feel good about where our program is it's not any single individual within our program that's responsible for ultimately holding up all of those new relationships that we're trying to build… I think what ultimately puts our program on a really good track is the fact that [our supervisor] is also super, super conscious about matters related to race and equity, but also just relationships in general and that need for human interaction and positive relationships with people.

For this interviewee, the structural supports of their internal workplace facilitated collaborative work.

While institutional support was important, so too were tangible resources, mainly time, money, and tools to overcome language and learning style barriers. One interviewee specifically mentioned the difficulty of using certain funds to purchase food. Providing food at meetings was one way that the interviewee felt they could show respect for collaborators, and being unable to do so stunted their outreach efforts when they could not find alternate funding sources.

As mentioned above, the use of grant funding instead of institution funds often allowed interviewees to work on more collaborative and relationship-focused projects with immigrant farmers. Interviewees mentioned that grant funding could be designated to pay farmers for their time and expertise, which is more difficult with other funding sources. However, grant funding is less secure than other sources of funding, so reliance on it was presented as a source of uncertainty. Additionally, grant funding often requires letters of support from farmers, which could force a relationship to function transactionally before trust has been built; this can lead to a formal paperwork request from farmers in place of robust collaborative work that the involved parties would prefer. Concerns about this type of non-robust relationship was described by one of the farmer cooperative advisers as seeing the farmers as “just another number”. As an example, the adviser described a recent situation in which a professor from one of the state universities who had approached the non-profit asking them to contact Latinos on his behalf, and they had agreed, but wanted to make sure that there would be some sort of compensation:

This is not the only group that has said, we can't figure out how to work with Latinos, except if we come to you. But they [the university personnel] are getting something out of it, rather than just trying to benefit our clients. That's our suspicion.

The necessity of compensation and mutual benefit, as highlighted earlier, is a continued barrier for collaboration, and demonstrates the key role of trust-building in the collaboration process.

Addressing language barriers also emerged as a key resource concern. One of the farmers, who had recently begun collaborating with Extension on a project, said that before that project, his understanding was that “the university is just for… a different class of people who weren't farmers, or who were [English-speakers] from the US.” For this farmer, the most important way to build relationships was to have potential collaborators visit the farm and spend time talking with farmers, which would require potential collaborators to either speak Spanish or hire an interpreter.

One of the farming cooperative advisers also highlighted how language and learning style barriers needed to be addressed simultaneously for successful collaboration. One example given was that a soil health manual created by a university researcher was inaccessible to most of the farmers, despite having been translated to Spanish, because most of them are not comfortable learning from written material. Instead, the adviser stated that “we can't just send people through the existing systems [of farmer education]. We have to set up an alternative system, [one] that is mostly in the field, not in the classroom.”

In addition to institutional attitudes, multiple interviewees mentioned the importance of individual introspection and self-awareness. Interviewees from the university and state agencies described their lack of confidence and/or their organization's lack of history working with immigrant farmers and acknowledged that university and government entities have not historically had sustained collaboration or even “community presence”. One participant felt that the organizational reputation limited their professional capacity: “it's like [the organization] is bad. That's really hard… because I'm not a bad person”. Conversely, others stressed the importance of “taking your ego out of it” and “getting out of your comfort zone” in order to build relationships. Perceived level of institutional support did not affect whether interviewees mentioned the importance of leaning into discomfort, indicating that while the capacity for discomfort and recognizing its importance could be supported by supervisors, it was also an internal capacity issue independent of institutional culture.

Collaboration and engagement between farmers of the cooperative and academics, government, and non-profits in this study remain uneven. However, farm support professional clearly expressed the desire to provide access to resources and knowledge, and repeatedly recognized that working with immigrant and minority farmers improves their institutional capacity to accomplish goals. The goals and motivations of individual collaborators formed the backdrop that determined the types of resources they sought out and the effects of their efforts. The resources sought by collaborators and the effects of their work mutually reinforced one another (Figure 1).

In general, interviewees were committed to some sort of relational process. The commitments to creating space for co-learning indicate an appreciation for different types of knowledge necessary to facilitate horizontal learning and wisdom dialogues. Interviewees were also well aware of the institutional norms and hierarchical structures that affected their ability to do the work and had divergent approaches to address these. This indicates ongoing space-making for the emergent discourses of wisdom dialogues, which in turn could impact the goals and motivations for participating in collaborations with farmers. Continued and expanded use of wisdom dialogues and horizontal forms of collaboration are clearly key to navigating some of the unresolved challenges expressed by participants, particularly to move away from models of extending information to those in which farmer knowledge is valued and learned by Extension, government, and non-profit farm support professionals. Key to moving toward these forms of knowledge exchange include developing a robust understanding of the differences between equity and equality, and having the resources to develop more intentional and mutually beneficial collaborations.

Farm support interviewees generally highlighted that their goal for collaboration and engagement was to provide material and informational access to immigrant and minority farmers. However, the actions necessary to provide access differ widely depending on how an individual or organization defines and evaluates equal access, which can be seen as a choice between “equity” and “equality” approaches. To illustrate the importance of an equity approach one interviewee mentioned a well-known “equity vs. equality” image, which includes side-by-side pictures indicating that equality is each party getting similar advantages despite their differences, which can reinforce inequality. In contrast, equity entails each party getting the same outcome supported by different advantages. For this interviewee, this image served as a visual reminder that providing an identical approach for all farmers was insufficient, and that some farmers needed a different approach to achieve equity. This was highlighted by the farmers and farm cooperative advisers who indicated that training for the Latino farmers in their cooperative needed to take into account their learning styles. Additional support for this perspective comes from an analysis of the lack of legibility between Latino diversified farmers and the USDA in the Mid-Atlantic Region (Minkoff-Zern and Sloat, 2016). In their study, the researchers found that the USDA focus on written records and standardization severely limited participation of Latino farmers in cost-share programs. These concerns were echoed by our farmer collaborators, who mentioned that word-to-word translations of information from English to Spanish was often insufficient to make the information accessible to them.

Recognizing that different groups require different approaches of collaboration, engagement, and learning is at the core of wisdom dialogues and horizontal learning, because these concepts democratize the style of learning and teaching, and break down barriers between the two. A well-known example of this process is the campesino-a-campesino model in Central America, where farmers trained one another in agroecological practices (Holt-Giménez, 2006). The model approaches learning by scaling out. Knowledge is transferred horizontally, often through grassroots social movement networks (Mier y Terán et al., 2018). In the past decade across the USA, university Extension programs have launched various racial equity initiatives (see, for example, NCSU CEFS Committee on Racial Equity in the Food System, and MSU Center For Regional Food Systems Racial Equity in the Food System Workgroup). In Minnesota, grower involvement in advisory boards is becoming more common, and working collaboratively with growers to facilitate training on food safety, for example, has been the norm for many years. This is also a main area of success for non-profit farmer training groups, as mentioned in the introduction. University and government entities, even though they may be providing different services (e.g., collaborating with farmers at different stages of their careers), have much to learn about adapting learning materials and meeting farmers where they are at with language availability and other accessibility needs.

Farm support interviewees in this study expressed the desire for more explicit training on issues of equity; it will therefore be helpful to track the effectiveness of the aforementioned initiatives in order to adapt and expand them more broadly across LGUs. Continued use of wisdom dialogues and horizontalism, by valuing and including the wisdom of farmers, could build on current approaches that consider racial equity, and have the potential to increase farmer learning and enrich and transform institutional knowledge. However, the extent of this transformation depends on the extent of support available to practitioners: material support, time and compensation for self-learning, and career advancement opportunities that value recognition of multiple forms of knowledge should all be prioritized.

There is a long history of researchers and academic or government agencies using communities for their professional benefit, without reciprocal benefits to the community. Multiple interviewees in this study provided examples of this as one of the main limitations of working with outside entities; one interviewee expressed concern that the reputation of their institution might make farmers think they were a “bad person”. To overcome the lack of trust, potential collaborators must demonstrate their good-faith commitment to reciprocal benefit. In research, one opportunity to do this has been via the development of memorandums of understanding (MOUs), worksheets, and agreements to facilitate an explicit expression of the needs and capacities of all involved. Another important intervention has been to hire research collaborators from within target communities, which can improve the rigor of research as well as build relationships [see for example, protocols followed by the CLEAR lab (Liboiron, 2021)]. However, even projects specifically designed to address inequalities in food systems struggle to break free from “academic supremacy”, or the systematic privileging of academic partners in research collaborations (Porter and Wechsler, 2018). The four main aspects of inequality mentioned in that article—employment conditions, institutional support, capacity development, and autonomy and control of funding—are all relevant to the work discussed here. In non-research contexts, one interviewee stressed that they were working against a dominant paradigm of using collaboration and engagement to “check a box” or accomplish an external directive, which was precisely the worry that the farming cooperative advisers expressed. By addressing these factors explicitly and acknowledging the need for all parties in a collaboration to benefit, collaborations can build trust, and potentially redistribute resources so that all collaborators receive what they need from the process.

Careful attention to how trust is developed and demonstrated is an important component to overcoming concerns about motivations. In conversation with one of the farmers of the cooperative, they summarized a successful collaboration by saying, “you have to have a structure that in the end builds trust…Does it sound more poetic than theoretical? Yes, but this is one of the parts that I think would be most important for the university to have.” While a turn toward the poetic is unusual, if not explicitly frowned upon, in scientific disciplines, this approach is common in arts and design disciplines, which may have useful resources for creating emergent spaces within scientific discourse. One recent approach evaluated the use of imaginative exercises and scenario-building to facilitate the identification and development of transformative policy (Pereira et al., 2019). Some of the necessary prerequisites to this process include legitimate stakeholder involvement and inclusion of diverse voices; both of these important aspects were mentioned by multiple interviewees, but neither tended to be prioritized in their workplaces. Multiple interviewees claimed that the cultural events they have attended outside of work hours are critical to reach potential new collaborators, but that work needs more internal support.

In addition to material support that moves into the poetic and cultural aspects of trust building, reflective work is necessary. In one example, non-farmers working on a participatory project proposed the concept of “emotional rigor” to help navigate the complexity of participatory collaborative work (Bradley et al., 2018). Specifically, they provided examples of a praxis-from-the-heart, in which emotions related to the work are not seen as separate or tangential to the research process, but as a valuable and valid part that when acknowledged and acted on, can enrich the research process. This concept seems to be at the heart of much of the work undertaken by the interviewees in this case study. Many of them mentioned a personal connection to their work, and the various types of unpaid labor they engage in to be successful (such as attending cultural events and engaging in self-reflection and learning). Training and support to develop the emotional rigor evidenced by the interviewees and described by Bradley et al. (2018) could give current practitioners space to build on their horizontal learning approaches.

This case study offers the concepts of wisdom dialogues and horizontalism as tools to evaluate the successes and limitations of collaborations between a group of farmers and various non-farmer professionals. The goals and motivations of Extension, government, and non-profits reflect aspects of wisdom dialogues and horizontal learning. However, much can be learned from existing successful collaborative and participatory farmer-to-farmer training networks, and more can be done to disrupt structural inequities and mitigate prioritization (both implicit and explicit) of knowledge transmission over knowledge co-creation. This study also highlights the extent to which many farm support professionals, even those tasked with outreach to immigrant and minority communities, find their structural position limits outreach effectiveness. More resources are needed to support the practice of wisdom dialogues and horizontalism to make these tools a central and valued part of collaborations, instead of a layer on top of more conventional metrics of success. Based on the experiences of interviewees as well as experiences of the authors, we offer a few preliminary insights on how to navigate these challenges.

First, while the deep trust-building necessary for effective collaboration may be difficult to quantify in scientific disciplines, its importance seems universal. Practice is necessary to develop a deep appreciation of different perspectives that wisdom dialogues require. Folding trust-building into collaborative projects may be facilitated by (at least) the following practices: First, self-guided research, to bridge knowledge gaps as those expressed by the interviewees; do not expect collaborators to be the sole source of information on their cultural heritage or immigration history. There are many resources available and doing some self-reflective learning before engagement will alleviate some of the burdens from collaborators. Second, many interviewees stressed the importance of attending or volunteering at farmer-focused conferences and workshops. It may also be ideal to invite farmer collaborators to present (or co-present, if they prefer) in spaces where non-farmers are usually invited to be the expert. Finally, as highlighted by interviewees, supervisory support is key to facilitate success in relationship building. Those in supervisory roles can facilitate this process by providing training, monetary support, encouragement, and recognition of relationship-building as valuable work.

Trust-building takes time and energy, and farmers should not be expected to participate pro bono in collaboration. Finding ways to compensate farmers for their time both demonstrates that their time is valuable and may make the collaboration more sustainable. Interviewees provided many examples of mechanisms used to compensate farmers in Section Results of this paper, all of which can be used as guidelines for ensuring farmer compensation.

The implementation of these recommendation may be significantly affected by the level of support available. Advocacy across levels of power and influence are necessary to mitigate the limitations facing current and potential collaborators. In the meantime, recognizing where supervisors or departments fall on the spectrum from “none” to “active” support (Figure 2), along with the material resources offered with that level of support, will affect your strategy when developing partnerships. Ambitions and expectations may need to be adjusted as support and resource evaluation takes place.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board. All interviewees were provided with written informed consent to participate in the study.

VMW conceived the study and conducted data collection, analysis, and initial manuscript draft. NH contributed to draft revisions and framing. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This project was partially funded by a University of Minnesota Institute for Diversity, Equity, and Advocacy (IDEA) Multicultural Research Award. Collaborative research undertaken with growers that inspired the project was conducted as part of a Minnesota Department of Agriculture Specialty Crop Block Grant Program for Summer cover-cropping strategies and organic vegetable production for beginning, immigrant farmers 2016–2019. A second Minnesota Department of Agriculture AGRI Crop Research Grant for Chili pepper production, quality, drying methods, and market viability for Minnesota farmers (2020–2023) allowed for continued collaboration with the same farmers and helped to cover the publishing fees for this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The authors are grateful to Drs. Julie Grossman and Nicholas Jordan for their advice and support on this project. We also thank Dr. Kristen Nelson for her mentorship, to Rodrigo Cala and Javier García for their collaboration and wisdom, and to Lindsey Miller for her thorough and thoughtful technical review of the manuscript. We also thank the reviewers for their thoughtful comments and suggestions that strengthened the manuscript.

Adams, W. C. (2015). “Conducting semi-structured interviews,” in Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation, eds J. S. Wholey, H. P. Harty, and K. E. Newcomer, 4th Edn. (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass), 492–505.

ALBA (2022). Our Work. Available online at: https://albafarmers.org/our-work/ (accessed April 20, 2022).

Altieri, M. A. (1987). Agroecology: The Scientific Basis of Alternative Agriculture. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Anderson, C. R., Maughan, C., and Pimbert, M. P. (2018). Transformative agroecology learning in Europe: building consciousness, skills and collective capacity for food sovereignty. Agric. Hum. Values 36, 531–547. doi: 10.1007/s10460-018-9894-0

Barbercheck, M., Kiernan, N. E., Hulting, A. G., Duiker, S., Hyde, J., Karsten, H., et al. (2012). Meeting the ‘multi-’ requirements in organic agriculture research: Successes, challenges, and recommendations for multifunctional, multidisciplinary, participatory projects. Renewable Agric. Food Syst. 27, 93–106. doi: 10.1017/S1742170511000214

Berthet, E. T. A., Barnaud, C., Girard, N., Labatut, J., and Martin, G. (2016). How to foster agroecological innovations? A comparison of participatory design methods. J. Environ. Planning Manage. 59, 280–301. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2015.1009627

Boyer, E. L. (1990). Scholarship Reconsidered: Priorities of the Professoriate. New York, NY: The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Bradley, K., Gregory, M. M., Armstrong, J. A., Arthur, M. L., and Porter, C. M. (2018). Graduate students bringing emotional rigor to the heart of community-university relations in the Food Dignity project. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 8, 221–236. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2018.08A.003

Cadieux, K. V., Carpenter, S., Liebman, A., and Upadhyay, B. (2019). Reparation ecologies: regimes of repair in populist agroecology. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 109, 644–660. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2018.1527680

Cadieux, K. V., and Slocum, R. (2015). “What does it mean to do food justice?,” in College of Liberal Arts All Faculty Scholarship Paper 3.

Driscoll, A., and Sandmann, L. R. (2001). From maverick to mainstream: the scholarship of engagement. J. Higher Educ. Outreach Engage. 6, 9–19.

Etmanski, C. (2012). A critical race and class analysis of learning in the organic farming movement. Austr. J. Adult Learn. 52, 484–506.

Finlay, L. (2002). “Outing” the researcher: the provenance, process, and practice of reflexivity. Qual. Health Res. 12, 531–545. doi: 10.1177/104973202129120052

Garnett, T., Appleby, M. C., Balmford, A., Bateman, I. J., Benton, T. G., Bloomer, P., et al. (2013). Sustainable intensification in agriculture: premises and policies. Science 341, 33–35. doi: 10.1126/science.1234485

Goldstein, J. E., Paprocki, K., and Osborne, T. (2019). A manifesto for a progressive land-grant mission in an authoritarian populist era. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 109, 673–684. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2018.1539648

Guthman, J. (2008). “If they only knew”: color blindness and universalism in california alternative food institutions. Prof. Geogr. 60, 387–397. doi: 10.1080/00330120802013679

Gutiérrez-Montes, A. I., and Aguero, F. R. (2016). “The Mesoamerican agroenvironmental program: critical lessons learned from an integrated approach to achieve sustainable land management,” in Agroecology: A Transdisciplinary, Participatory and Action-Oriented Approach, eds V. E. Méndez, C. M. Bacon, R. Cohen, and S. R. Gliessman (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press).

Hart, M. A. (2010). Indigenous worldviews, knowledge, and research: the development of an indigenous research paradigm. J. Indigenous Voices Soc. Work 1, 1–16. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/10125/15117

Heleba, D., Grubinger, V., and Darby, H. (2016). “On the ground: putting agroecology to work through applied research and extension in vermont,” in Agroecology: A Transdisciplinary, Participatory and Action-Oriented Approach, eds V. E. Méndez, C. M. Bacon, R. Cohen, and S. R. Gliessman (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press).

Herren, R. V., and Edwards, M. C. (2002). Whence we came: the land-grant institution-origin, evolution, and implications for the 21st century. J. Agric. Educ. 43, 88–98. doi: 10.5032/jae.2002.04088

Holt-Giménez, E. (2006). Campesino a Campesino: voices from Latin America's farmer to farmer movement for sustainable agriculture. Oakland, CA: Food First Books.

Hunter, M. C., Smith, R. G., Schipanski, M. E., Atwood, L. W., and Mortensen, D. A. (2017). Agriculture in 2050: recalibrating targets for sustainable intensification. BioScience 67, 386–391. doi: 10.1093/biosci/bix010

Jordan, C., and Gust, S. (2010). “The Phillips neighborhood healthy housing collaborative: forging a path of mutual benefit, social change, and transformation,” in Participatory Partnerships for Social Action and Research, eds L. M. Harter, J. Millesen, and J. Hamel-Lambert (Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt), 9–29.

Klodd, A., and Hoidal, N. (2019). Needs Assessment of Minnesota Fruit and Vegetable Producers. Farmington, MN: University of Minnesota Extension.

Kroma, M. M., and Flora, C. B. (2001). An assessment of SARE-funded farmer research on sustainable agriculture in the north central U.S. Am. J. Alter. Agric. 16, 73–80. doi: 10.1017/S088918930000895X

Lacombe, C., Couix, N., and Hazard, L. (2018). Designing agroecological farming systems with farmers: a review. Agric. Syst. 165, 208–220. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2018.06.014

Levkoe, C. Z. (2019). Race, privilege and the exclusivity of farm internships: ecological agricultural education and the implications for food movements. Envir. Plan. E Nat. Space 3, 251484861987261. doi: 10.1177/2514848619872616

Liboiron, M. (2021). CLEAR Lab Book: A living manual of our values, guidelines, and protocols (Version 3). St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador: Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research (CLEAR), Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Lyon, A., Bell, M., Croll, N. S., Jackson, R., and Gratton, C. (2010). Maculate conceptions: power, process, and creativity in participatory research. Rural Sociol. 75, 538–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-0831.2010.00030.x

Martínez-Torres, M. E., and Rosset, P. M. (2014). Diálogo de saberes in La Vía Campesina: Food Sovereignty and Agroecology. J. Peasant Stud. 41, 979–997. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2013.872632

McCamant, T. (2014). Educational Interests, Needs and Learning Preferences of Immigrant Farmers. Prepared for the Center for Rural Policy; Development. Available online at: https://www.ruralmn.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/immigrantfarmerssurvey.pdf (accessed May 26, 2022).

McDowell, G. R. (2001). Land-Grant Universities and Extension Into the 21st Century: Renegotiating or Abandoning a Social Contract. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press.

Méndez, V. E., Bacon, C. M., Cohen, R., and Gliessman, S. R. (2016). Agroecology: A Transdisciplinary, Participatory and Action-Oriented Approach. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Mier y Terán, M. G. C., Giraldo, O. F., Aldasoro, M., Morales, H., Ferguson, B. G., Rosset, P., et al. (2018). Bringing agroecology to scale: key drivers and emblematic cases. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 42, 637–665. doi: 10.1080/21683565.2018.1443313

Minkoff-Zern, L. A. (2017). Race, immigration and the agrarian question: farmworkers becoming farmers in the United States. J. Peasant Stud. 45, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2017.1293661

Minkoff-Zern, L. A., and Sloat, S. (2016). A new era of civil rights? Latino immigrant farmers and exclusion at the United States Department of Agriculture. Agric. Hum. Values 34, 631–643. doi: 10.1007/s10460-016-9756-6

Minnesota Department of Agriculture (2022). Specialty Crop Block Grant Pat Projects. 2016 Federal Fiscal Year. Available online at: https://www.mda.state.mn.us/business-dev-loans-grants/specialty-crop-block-grant-past-projects#FFY16 (accessed April 15, 2022).

New Entry Sustainable Farming Project (2022). Farmer Training. Available online at: https://nesfp.org/farmer-training (accessed April 20, 2022).

Olds, T., Schned, M., Gill, M., and Norquist, P. (2019). Equity in Minnesota Farming and Farm to School Programs. Minneapolis, MN: UMN Digital Conservancy.

Pereira, L., Sitas, N., Ravera, F., Jiménez-Aceituno, A., and Merrie, A. (2019). Building capacities for transformative change towards sustainability: imagination in intergovernmental science-policy scenario processes. Elem. Sci. Anth. 7, 35. doi: 10.1525/elementa.374

Peters, S. J. (2013). “Storying and restorying the land-grant system,” in The Land-Grant Colleges and the Reshaping of American Higher Education, eds R. L. Geiger and N. M. Sorber (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers), 335–353.

Peters, S. J. (2014). Extension Reconsidered. Choices 29. Available online at: http://www.choicesmagazine.org/UserFiles/file/cmsarticle_359.pdf (accessed May 05, 2017).

Peters, S. J., and Wals, A. E. J. (2013). Learning and Knowing in Pursuit of Sustainability: Concepts and Tools for Transdisciplinary Environmental Research. Trading Zones in Environmental Education: Creating Transdisciplinary Dialogue (New York, NY: Peter Lang), 79–104.

Porter, C. M., and Wechsler, A. (2018). Follow the money: resource allocation and academic supremacy among community and university partners in Food Dignity. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 8, 63–82. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2018.08A.006

Pretty, J. N. (1995). Participatory learning for sustainable agriculture. World Dev. 23, 1247–1263. doi: 10.1016/0305-750X(95)00046-F

Reason, P., and Torbert, W. R. (2001). The action turn: toward a transformational social science. Concepts Transform. 6, 1–37. doi: 10.1075/cat.6.1.02rea

Scott, D., and Barnett, C. (2009). Something in the air: civic science and contentious environmental politics in post-apartheid South Africa. Geoforum 40, 373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2008.12.002

Slocum, R. (2007). Whiteness, space and alternative food practice. Geoforum 38, 520–533. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2006.10.006

Sonix (2020). Available online at: https://sonix.ai/ (accessed April 10, 2020).

Stern, M. J., and Coleman, K. J. (2015). The multidimensionality of trust: applications in collaborative natural resource management. Soc. Natural Resources 28, 117–132. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2014.945062

Sullivan, C., and Peterson, M. (2015). The Minnesota Farmer: Demographic Trends and Relevant Laws. Saint Paul, MN: House Research Department; Minnesota State Demographic Center; Prepared by the House Research Department; Minnesota State Demographic Center.

Temi (2020). Available online at: www.temi.com (accessed April 10, 2020)

The Food Group (2022). Big River Farms. Available online at: https://thefoodgroupmn.org/farmers/ (accessed April 20, 2022).

Torbert, W. R. (2001). “The practice of action inquiry,” in Handbook of Action Research, eds P. Reason and H. Bradbury (London: Sage Publications), 250–260.

Van de Fliert, E., and Braun, A. R. (2002). Conceptualizing integrative, farmer participatory research for sustainable agriculture: from opportunities to impact. Agric. Hum. Values 19, 25–38. doi: 10.1023/A:1015081030682

Warner, K. D. (2006). Extending agroecology: grower participation in partnerships is key to social learning. Renewable Agric. Food Syst. 21, 84–94. doi: 10.1079/RAF2005131

Keywords: outreach, food systems, immigrant farmers, collaboration, Extension, agroecology

Citation: Wauters VM and Hoidal N (2022) Horizontalism and Wisdom Dialogues to Build Trust: A Case Study of Collaborations With Immigrant Farmers in Minnesota. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 6:872751. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2022.872751

Received: 09 February 2022; Accepted: 18 May 2022;

Published: 16 June 2022.

Edited by:

Joji Muramoto, University of California, Santa Cruz, United StatesReviewed by:

Liz Carlisle, University of California, Santa Barbara, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Wauters and Hoidal. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vivian M. Wauters, dndhdXRlcnNAdWNkYXZpcy5lZHU=

†Present address: Vivian M. Wauters, Department of Horticultural Science, University of Minnesota, Saint Paul, MN, United States

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.