- 1Faculty of Agricultural and Food Sciences, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon

- 2Department of Business and Social Sciences, Faculty of Agriculture, Dalhousie University, Truro, NS, Canada

- 3Sciences Po Rabat, College of Law, and Political and Social Sciences, Université Internationale de Rabat, Rabat, Morocco

Food system transformations occur in a complex political, economic, social, and territorial landscape. The study provides a historical construction of global food regime changes and the adaptiveness, transformability, and resilience of the local food system in Lebanon, a Middle Eastern context. Lebanon offers a unique opportunity to understand the influence of global food regimes and geopolitics on agriculture, the local food system, and capital accumulation. After the 1975–1990 Lebanese Civil War, Lebanon experienced food retail transformation and international penetration through foreign investments. These alterations have several implications for society and the local food system: farming households' influence on agricultural policies and the political commitment to support the farming community decreased. The paper concludes that Lebanon's local food system transformation is a manifestation of geopolitical events and global food regime changes. This may have important implications and pave the way for a new food system that is based on the revitalization of agriculture and new forms of geoeconomic partnerships with regional actors.

Introduction

Lebanon predominantly has a family-based agrarian structure linked to its natural, religious, and cultural heritage and geopolitical system (Al Dirani et al., 2021). Indeed, Lebanon was a prosperous agricultural country as late as the 1950s, exporting surplus agricultural production to neighboring countries. However, post-1950s, the farming households' influence on agricultural policies and the political commitment to support the farming community decreased and shifted to the service sector (FAO, 2017). Recently, amid geopolitical turbulence, global pandemic, and recession, there has been a renewed interest in revitalizing agriculture (MOA, 2020). A historical construction of geopolitical and economic events may help expand our understanding of food system changes and the adaptiveness and transformability of the local food system (Meyer, 2020).

Since the late 19th century, three periods can be identified to explain the transition in global food regimes: the first food regime occurred during the colonial era, which lasted until approximately 1945; the second food regime manifested post-World War II and was marked by the rise of the Green Revolution (Bernstein, 2016); and the third or current global food regime is characterized by trade liberalization, globalization, and corporatization. As a result, the third regime is also often termed the “corporate” food regime; this is because it emphasizes imperial states and how they have permitted their economies to be re-regulated in favor of transnational capitalist interests. There is also a tendency to describe the third food regime as a “neoliberal” food regime to better understand agrarian and politico-economic dynamics and acknowledge distinct trends in post-neoliberal developments.

Food system transformations occur in a complex political, economic, social, and territorial landscape, and such transformations are varied and context-specific (Bernstein, 2016). However, the traditional food literature does not address the role of geopolitical and historical events in transforming local food systems (Søndergaard, 2020) and the complexities of alternative food regimes (Manganelli et al., 2020). This study engages with recent re-conceptualizations of food regime theory, particularly with the work of Tilzey (2018, 2019) and Søndergaard (2020). The latter provides a historical construction of food system transformations (in the Brazilian context) but focuses on the third, the corporate food regime. Our study goes back to the colonial era (first-food regime) to document geopolitical and economic events shaping the current food regime in the Middle Eastern context. Lebanon offers a unique understanding of geopolitics' influence on agriculture and the dynamics of local food systems. Previous research shows that the corporate food regime has been integrated in Lebanon alongside the traditional local formats (Seyfert et al., 2014; Bahn and Abebe, 2017).

The study aims to provide a historical construction of geopolitics and geoeconomics and the impact this may have on the recent food system changes in Lebanon. More specifically, the study aims to address the following questions: (1) Which historical and geopolitical developments could be linked to the manifestation of the neoliberal food regime in Lebanon? (2) What are the lessons learned from a historical analysis of food regime changes in Lebanon? (3) What anticipated food system transformations are associated with historical events, the recent economic depression, and political uncertainty? The research draws on secondary sources to answer these questions and utilizes a qualitative framework provided by Lune and Berg (2017) and Søndergaard (2020).

Food Systems, Food Regime Changes, and Transnational Corporations

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO, 2018, p. 1) provides a broader definition of food systems as “the entire range of actors and their interlinked value-adding activities involved in the production, aggregation, processing, distribution, consumption, and disposal of food products that originate from agriculture, forestry or fisheries, and parts of the broader economic, societal and natural environments in which they are embedded.” Food system transformations occur in a complex political, economic, social, and territorial landscape and at various levels, global to local (Bernstein, 2016). Several factors drive the transformation in food systems, such as external (e.g., globalization, climate change, and sustainability) and internal (e.g., changes in the production technology and farming practices) (von Braun et al., 2021).

The global food system has had some notable failures. For example, the introduction of the Green Revolution promoted intensive monoculture farming systems by influencing national policies supporting such unsustainable food production practices. Consequently, food has become a commodity resulting from a competitive homogenous food supply, leading to adverse environmental, social, economic, and health impacts. The environmental cost includes loss of biodiversity, soil and water pollution, and an increase in global greenhouse gas emissions and the vulnerability of smallholder farmers. Such environmental and socioeconomic costs resulted in increased unsustainability of the food system. Moreover, the abundance of cheap, energy-dense food has increased obesity and diet-related chronic diseases. The combination of environmental, socioeconomic, and health costs contributes to selective food insecurity, usually among the most vulnerable segments of society.

McMichael (2009) proposed the food regime theory to analyze the relationship between historical geopolitical events and food system changes and explain the construction of the world capitalist economy. The food regime theory takes a political economy perspective to explore historical relations shaping global food system transformations. This theory highlights the role of agriculture and food in building world capitalism. Food regime changes happen during periods of instability and power struggles (Saab, 2018). Some marked instability and power struggles thus far have led to the first, second, and third food regime changes (McMichael, 2009). Historical geopolitical events impact food supply chains, particularly agricultural food production and trade, and cause food policy changes that affect food security at the local, regional, and global levels. For example, the famine in Europe during World War II called for an international conference in 1943, which focused on increasing food availability. This inspired the Green Revolution that caused a major global agricultural development and initiated a new food system, the second food regime.

The emergence of the corporate food regime in the 1990s has been characterized by the rearrangement of food supply chains through supermarketisation and corporatization of the food system (Bernstein, 2015). The corporate food regime attributes its success to its most instrumental tools–globalization and trade liberalization (McMichael, 2009). Researchers have identified transnational corporations (TNCs) as the primary tool for the globalization of the food system (Heffernan and Constance, 1994). While there is no universally agreed definition, the one provided by Weissbrodt and Kruger (2003, p. 908) defines TNCs as “enterprises, whether they are of public, mixed or private ownership, which owns or controls production, distribution, services or other facilities outside the country in which they are based.” For decades, TNCs have shaped the global food system, including the manifestation of supermarkets and corporate foodservice operations (Monteiro et al., 2013). Global agribusinesses form a foundational component of the corporate food regime (Reardon et al., 2003; McMichael, 2005). For example, global agribusinesses such as Germany's Bayer (USD 10.8 billion + 2.0 billion), the U.S.-based Corteva Agriscience (USD 8.0 billion in sales), China's Syngenta, including ChemChina, (~USD 3.0 billion in sales), and France's Limagrain (USD 1.8 billion in sales) topped the global seed sales, accounting ~69% (Zhang, 2019). Such global agribusinesses influence not only food supply and agriculture but also geopolitics and food sovereignty.

Methodology

Research Design

According to Lune and Berg (2017), analysis of historical events can be a valuable tool for understanding the transformation in the food system. This research utilizes secondary (publicly available) data to assess the relationship between historical geopolitical events and food system changes in Lebanon. It applies a chronological sequence of events to understand food system transformations in Lebanon. The events chosen were World War I and II, the Cold War, the Lebanese Civil War, and their political aftermaths. These significant historical geopolitical events coincided with the first, second, and third food regimes. Such events were tabulated to show the historical breakdown and transition of food system changes in Lebanon for the first, second, and third regimes.

Study Context

Lebanon is a small, developing country located in the Middle East along the Mediterranean Sea. Lebanon was part of the Ottoman Empire until 1920, when France colonized it until independence in 1943. Israeli Lebanese relations deteriorated after the Six-Day War in 1967, leading to political tension and conflict, exacerbating instability locally and regionally (Karsh et al., 2013). Lebanon subsequently underwent a civil war between 1975 and 1990 that reflected the aftermath of the Arab Cold War (the 1950s−1960s) or the Lebanese Civil War of 1958 and was invaded by Israel in 1978. The Lebanese Civil War concluded following the 1989 Taif Accord, which instated the distribution of governmental power and representation of relevant groups based on sectarianism and consociationalism (Rosiny, 2013). The Syrian regime occupied Lebanon militarily and politically until 2005 (Ryan, 2012). Another significant event in Lebanon occurred in mid-October 2019, also known as the “October Revolution”. This event marked the people's condemnation of the ruling class, reconciliation from the civil war, and denunciation of political sectarianism (Bergman, 2020).

Data Sources and Analysis

This historical analysis is based on qualitative research methods, following the approach set out by Lune and Berg (2017). In this research, secondary data sources were used to extract historical data about Lebanon during major global geopolitical events. A timeframe of events was set chronologically, and sources related to agriculture, trade, and economic policies were included. Multiple sources (publicly available), including journal articles, history books, governmental data, and company histories, were consulted, when possible, to triangulate information from various sources. These sources were critically and systematically analyzed. Accordingly, title themes were categorized according to distinct periods, chronologically, starting with the first food regime and its foundation and ending with the neoliberal food regime and its aftermath. A careful interpretation of critical historical events was conducted to explain the local food system transformation in Lebanon.

Findings and Discussion

Manifestation of Global Food Regimes in Lebanon

Corporate retail transformation is a global phenomenon; however, the rearrangement of the supply chain within the global context is unique for every country or region. In the following, we analyze the geopolitical history of Lebanon and how it helped constitute the first, second food, and third food regimes that have shaped the country's agriculture and trade policies.

The First Food Regime and Food System Transformations in Lebanon

The first food regime (the 1870s−1914) began with Europe's colonial hegemony over settler states in Asia and Africa, where exported wheat and tropical fruits were the primary commodities transported to Europe (Dörr, 2018). Expansion in cultivated areas was realized along with the overexploitation of peasants. The basis of supplying cheaper wheat from these colonies than farms in Europe depended on unpaid labor costs, especially among family farms (Friedmann, 2005). The first food regime ended with the First World War in 1914, followed by the grain price collapse and the Great Depression (1929–1939). This set the stage toward the end of the Second World War for the second food regime (the 1940s−1970s), where the US gained power after pledging to rebuild and feed post-war Europe by adopting agricultural and foreign policies under the era of the Green Revolution (1950s−1960s) (Magnan, 2012).

Lebanon was not yet part of the European-based Allied coalition rule (1917–1920) or the French rule (1920–1943) during the first food regime but rather was under Ottoman Rule (1516–1917). During pre-war Lebanon, significant developments were reported in agriculture and trade. Under the rule of Bashir Shihab II (1789–1840), the commercial economy of Beirut became interdependent with the agricultural economy of Mount Lebanon. The political landscape was altered and allowed for the agricultural expansion into cash crops that had persisted into the 20th century (Fawaz, 1984). Agricultural development then led to Europe's penetration into Lebanon's economic and political structure. Lebanon's sectarian structure created a foreign tension within the Ottoman Empire. The French sided with the Maronites, and the British sided with the Druze, creating political struggles over the right to land, especially between the Maronites and Druze populations of the region (Salih, 1977). Before the League of Nations mandated France in 1920, Mount Lebanon only included the central part of current-day Lebanon, but the mandate still allowed for the inclusion of the north toward Syria, the south toward Palestine, and the interior Bekaa Valley. This geographic expansion of de facto borders would change Lebanon's political economy by opening new agricultural lands and making way for new foreign trade policies.

The clearest agricultural development during Lebanon's transition across food regimes goes back to silk production during the 1860–1914 period that coincided with the first food regime. The agrarian and urban bourgeoisie were created during this period, where private land property reforms were apparent, along with the conversion of farmland into industrial production (Roland Riachi and Martiniello, 2019). In Mount Lebanon, the mulberry tree as a feedstock for silkworms became a monoculture dominating around 80% of the agricultural landscape, spreading massively in Lebanon's Bekaa and coastal areas. Surprisingly, the fall of the feudal structure (1858) led to a shift from large-scale to small-scale farms and thus encouraged private investment in producing silk with financial incentives supported later by the Ottoman government. The peasants, now independent of their landowners, became dependent on the merchants, and thus the landowners sought lower economic and political power to remain part of the transforming agricultural system. The proprietors had become dependent on brokers and merchants, who functioned as intermediaries between the ports and the French market, allowing them to have a larger profit. The region in this period recognized a shift from subsistence farming of cereal to cash crop systems to meet European demand. Also, in this period, the rural population was primarily employed in silk manufacturing. Nevertheless, Mount Lebanon also grew barley and corn; however, it had to import its remaining demand from Syria and parts of the Bekaa. France, in this period, was fully invested in the silk industry importing around 40–50% of the world's silk production, and Mount Lebanon was able to penetrate this market. Another motivator was when the Ottoman rulers, in 1882, removed the taxes on newly planted mulberry trees for the first 3 years to meet the rising demand for silk. By 1895, the French consul reported a declining investment in silk production and recommended a shift to other profitable crops, where vinicultural methods encouraged grape production. Also, this led to the uprooting of the mulberry tree and replacing them with olives, figs, citrus production, and tobacco. However, the decline in profitability and the number of mulberry trees were not realized until 1914 (Firro, 1990).

The region operated under a laissez-faire liberal economic structure up until Arab domestic uprisings (1908–1909) and the Ottomans involvement in foreign wars (1911–1913). The Ottomans increased interference in global geopolitics and alliance with Axis powers (1914) eventually led to the Famine of Lebanon in 1915. The famine was due to Lebanon's reliance on exporting cash crops to Europe, which had been impaired through sea blockades set by the Allies that restricted the export of cash crops (mainly silk) and import of foodstuff from the West accompanied by a land blockade established by the Ottomans that restricted the import of regional foodstuffs (Collelo, 1989). This crisis marked the end of the first food regime. The events that followed would set the stage for the second food regime when The Occupied Enemy Territory Administration (1917–1920) immediately sought the importation and distribution of seed grains and livestock to cater to the people's needs. Besides, financing through army bankers was made available along with the restoration of postal services and the establishment of a stable currency. Table 1 provides a summary of the first food regime in Lebanon.

The Second Food Regime and Food System Transformations in Lebanon

The second food regime (the 1940s−1970s) began with the end of European colonization over settler states and these states' independence around the end of World War II, where the US claimed the hegemonic role as a major cereal exporter to the import-dependent developing world. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) (1947) ensured the legal framework for nations to be more involved in world trade and thus completed the Western-led post-war global economic system (Fenby, 2018). The shifting political power was realized with the agricultural developments of the Green Revolution (the 1950s−1960s) and the emergence of agribusiness corporations in food processing and input markets (Dörr, 2018). The dynamic had shifted to produce a surplus that would be imported to the world market, especially ex-settler states, and to set the stage for the food manufacturing industry to become a major actor in the food supply chain.

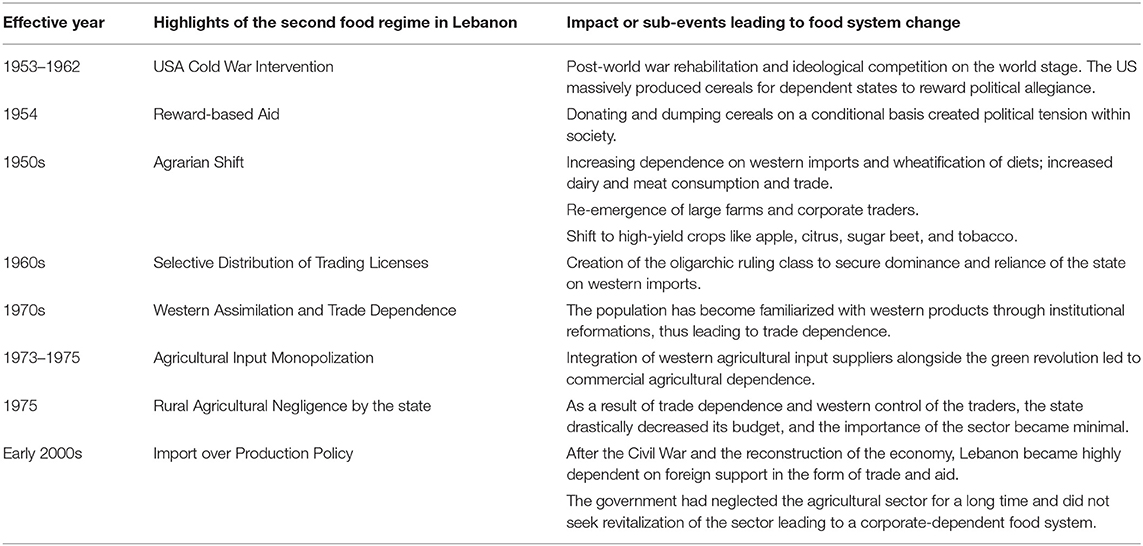

In 1954, President Eisenhower signed the PL-480 that was later amended in 1961 into Public Law 87–195 under the Kennedy Administration to bolster the recipient nation's social, economic, and political development (Office of the Historian, n.d). Subsequently, the United States granted Lebanon a sum of $86.2 million in the form of food aid during the period from 1946 to 1980 (Addis, 2011). In 1958, the United States intervened in Lebanon to restore order and peace. In this case, the communist insurgence of the United Arab Republic (Syria and Egypt) and internal opposition threatened the pro-Western regime of President Camille Chamoun (Bryson, 1980). This event falls with the major geopolitical conflicts globally in correspondence to the Cold War (particularly the 1953–1962 periods). This played a vital role in food regime analysis because it would decide a country's foreign policy, especially on trade and eventually on agriculture. The anti-communist doctrine of the US administration reinforced its strategy in the form of aid on a reward basis rather than on need (AbuKhalil, 2005). In addition, the food aid dependency during this period relied on the consolidation of private property rights and the Green Revolution that allowed the US to overflow the MENA markets with wheat, which eventually led to the wheatification of diets (Roland Riachi and Martiniello, 2019).

Thus, the protection and prevalence of pro-western ideologies and the foreign facilitation of trade and capital shaped the path for the structure of the Lebanese economy. In the 1960s, Western financial institutions penetrated the Beirut market, dominating 75% of foreign companies. By 1972, industrial exports (including finished or intermediate goods) displaced the export of raw goods (primarily agricultural) by a 24.6% difference and grew to account for two-thirds of total export value. And by 1973, commodity imports were equivalent in value to 53.6% of Lebanon's GDP. During this period, an import quota was administered by the Ministry of Trade and then assigned licenses obtained by a few politically powerful traders, creating an oligopoly. In 1974, four companies accounted for two-thirds of total imports from Western countries. Therefore, an oligopoly or an oligarchic ruling class controlled agricultural inputs, food, and textile products (Nasr, 1978).

Western hegemony influenced the political economy involved in rural agricultural production. Local agricultural production would witness a drastic change due to the economic and political pressures of urban merchants. The agrarian change in Lebanon contributed to a decline in total agricultural output, with a 53% decrease in cereal production from 1948 to 1970, where cereals were then imported from Australia and the US. Furthermore, Lebanon had witnessed a surge in meat, livestock, and milk imports during this period due to significant subsidies made by the European Economic Community for dairy products. The shift in agricultural production was motivated to produce other high-yielding agro-exports like fruits, apples, and citrus, respectively realizing a 700% and 250% increase in output during 1955 to 1971. Apples were grown on small- and medium-sized plots in the mountains, while citrus was cultivated on a “capitalist farm” in the coastal south. By 1974, 91% of Lebanese fruit exports were absorbed by the Arab market. Also, the tobacco production in the south increased three-fold, and that of sugar beet rose five-fold during the 1955–1970 period. However, the expansion of sugar beet and tobacco production was obstructed by the respective importers. So, production capacity potential was gradually replaced with import dependency so that traders would increase profits by selling imported sugar (Nasr, 1978). It is interesting to look at sugar as a component of corporatization and Western trade infiltration, justified by the nutrition transition that would follow this period globally.

Moreover, sugar beet was subsidized by the state since 1967 as a price control measure while encouraging production, halted in 2002, and finally terminated in 2007 due to the industry's monopolistic nature and the crop's environmentally damaging impact (Saadi, 2001). The failure would be later blamed on the Civil War. Yet, the real failure of the sector can be attributed to the traders that owned the only sugar processing plant in the country but favored importation, despite or in opposition to being supported by the state's subsidy program. For the case of tobacco, the state-controlled company, Regie des Tabacs (1935/1952), would procure tobacco leaves from local farmers at a subsidized rate, export them to processors, import them back as cigarettes from the US, and sell them to distributors, leading to an economic deficit and drainage of the public treasury (Salti et al., 2014). Moreover, removing subsidies would negatively affect small-scale farmers, where international food price volatility and changing climate conditions play supporting roles (Roland Riachi and Martiniello, 2019).

During the 1950s, big capitalist farms producing primarily citrus, sugar beets, and potatoes in Akkar, Bekaa, and the southern coastal plain emerged by procuring land from absentee or feudalist proprietors. By the mid-1960s, three-fourths of the rural population still owned land, where 67% had less than three hectares of land, and 50% had less than a hectare of land. These farms primarily relied on family labor and could be considered family farms. The system consisting of landowners, bankers, usurers, and traders further exploited farmers to facilitate feudalistic practices even after liberation over Ottoman rule. Also, concerning the Green Revolution's involvement during the second food regime, the assimilation of its tools was supplied by big Western agribusiness firms and facilitated by their local agents. By 1970, 25 traders for two-thirds of apples; 20 traders for 80% of citrus products controlled marketing resources, including transportation, storage, and financial resources allowing them to buy products cheaply from producers and sell profitably to consumers. At the same time, the private sector and foreign banks controlled agricultural credit because it was neglected by the public sector, where farmer debt accumulated to 50 m LBP in 1950, reaching 160 m LBP by 1973. By 1973–1975, two firms, Unifert and Le Comptoir Agricole, controlled the agricultural inputs market, realizing high returns rates of 300% on insecticides. As a result, the GDP share of agriculture decreased (20–12% from 1948 to 1964), government spending on agriculture decreased (reaching 2.3% in 1973), and the active population working in agriculture decreased (48.9–18.9% from 1959 to 1970). Rural migration to city centers mirrored the shift in labor away from the agricultural sector and into the industrial and service sectors. Lack of government involvement in the agricultural sector allowed for the penetration of foreign capital, while the domination of the private sector led to an increase in corporate power over the local economy (Nasr, 1978). The industrialization has undervalued the value of fresh agricultural goods due to the extension of shelf life that improves warehouse storage duration and logistical capabilities over long distances, as the backbone to facilitate global trade. Table 2 summarizes historical events related to the second food regime in Lebanon.

The Neoliberal Food Regime in Lebanon

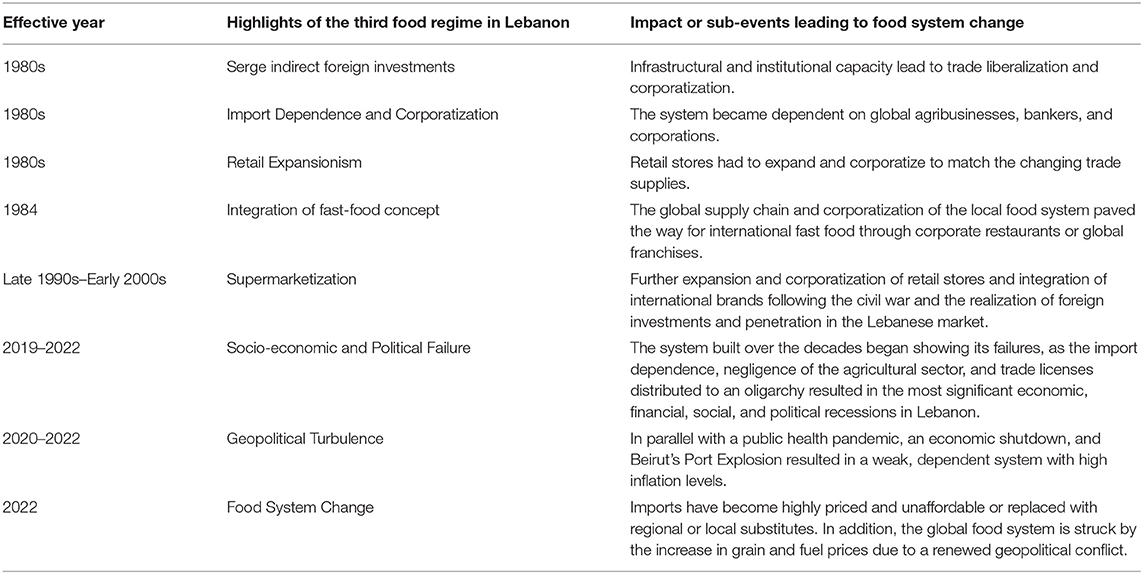

The neoliberal food regime (1980s-present) or the third food regime is a post-developmental globalization project settled by the end of the Cold War (1947–1991). During this period, liberalization and corporatization claimed victory to set the world stage for the next 40 or more years. Fundamental infrastructure such as ports, roads, power generators, and grids have been installed in the form of aid or loan to make way for a new food system. This system is controlled by global agribusinesses, bankers, and especially corporations. The tools used are no longer occupation, but hegemony in the form of import dependency, aid, and debt. Thus, a neo-colonial system was employed locally and managed by clashing imperial states. Historically, it is interesting how the political and economic turmoil came in parallel with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the year before the reconstruction plan for Lebanon. Subsequently, the US. and France, and more recently, Germany and the Netherlands supported the country with aid and investment and facilitated international trade. This had a temporary boost on the economy, bringing short-term liquidity and growth but failed due to bad policies and overfunded investments. The shift in the political economy concerning agriculture marks the foundation for corporate involvement in the food industry, where supermarkets and the corporate foodservice industry redefined a new corporate-driven food regime accompanied by a nutrition transition that still shapes the food system, especially in the developing world. The food system shift has been facilitated by increased foreign direct investments, leading to the assimilation of settlers' cultures within the local context.

The concept of fast-food or international cuisine and the procurement of a large array of products imported from around the world were facilitated during this period. In 1984, during Lebanon's Civil War, Juicy Burger opened in Beirut with the hope of becoming the “McDonald's of the Arab World” and thus introducing the fast-food industry in the country. By 1997, McDonald's entered the market, starting with its primary location at Ain Mreiseh, Beirut. This has opened the door for other local and international corporate fast-food chains to penetrate the local market. The healthy local Lebanese diet would now compete with the unhealthy western food brought by the neoliberal or corporate food regime.

Lebanon is one of the Middle Eastern countries affected by the third wave of supermarketization, a phenomenon reported in the developing world (beginning in the late 1990s-early 2000s), including Central and South America, Asia, Eastern Europe, and part of Africa (Reardon and Hopkins, 2006). Interestingly, key supermarkets in Lebanon began long before the second food regime. For example, Bou Khalil (Lebanese-based) opened in 1935 during the French Mandate over Lebanon (1920–1943), and Spinneys (Egyptian-based) followed in 1948 after the country's independence (1943). Supermarkets in Lebanon re-emerged during the third wave of supermarketization with the opening of Monoprix's (French-based) establishment in 1999, The Sultan Center (Kuwaiti-based) in 2008, and Carrefour (French-based) in 2013. However, one of the largest and most successful supermarkets, Charcutier Aoun (Lebanese-based), began as a family-operated grocery shop in 1953. This supermarket expanded and merged with other retailers in 1956–1976 using refrigeration and contractual leasing of part of the stores (significantly the meat/Charcutier section), integrating a family-owned local meat production facility by 1982, further expanding into various locations in 1999, and corporatizing and rebranding by early 2000s and onwards1.

As a prerequisite of the neoliberal food regime, Lebanon's Gross National Agriculture Product (GNAP) entered a period of stagnation from 1967 to 1975, where corruption permeated government institutions and drastic changes in policies followed. From 1975 to 1988, market structures were destroyed by the Civil War, and agricultural production declined except for prohibited crops that flourished during this period. From 1989 onwards, the agricultural sector entered a period of negligence. The GNAP of Lebanon had decreased by 10.45% from 1970 to 1996 when the West's GNAP increased drastically by 384% in the US and 544% in the EU. Since 1992, the government's expenditure on agriculture was almost absent. During the reconstruction process of Lebanon, the FAO, UNDP, the World Bank, the EU, and the bilateral support of France, Italy, Germany, the US, and Holland provided support to Lebanon. However, each of the countries and unions involved had its agendas, while Lebanese authorities could not redirect foreign investments effectively. A top-down approach was utilized by international organizations, which was not adaptable to Lebanese conditions. Those investments were wasted due to the lack of vision in economic and social policies concerning rural agricultural society and the lack of a proper agricultural framework and policies to execute a plan. NGOs launched hundreds of development projects in Lebanon; however, the lack of a national coordinating body allowed ineffective implementation, sometimes with negative results. The apparent substantial development impact on rural communities and the agricultural sector was not reached. Historical events associated with the third food regime in Lebanon are displayed in Table 3.

Geopolitical Turbulence, Economic Recessions, and the Current Food System Challenges

The manifestation of the neoliberal food regime in Lebanon is evident through several social, economic, and political developments. Historical geopolitical events have altered current food regime models and thus forced food system transformation. The transition from the first to the second food regime was marked by World War II globally, independence, and the establishment of a capitalist economic regime in Lebanon. The transition from the second to the third food regime was the end of the Cold War globally and the Lebanese Civil War in Lebanon. For a food regime change from the third to the fourth, the global Covid-19 pandemic and the economic crisis, and the ongoing geopolitical turmoil are expected to be the main drivers. According to Clapp and Moseley (2020), the Covid-19 pandemic marks a pivotal point to demand a new set of food policy changes due to the disturbances along the global food supply chains, global economic recession, and irregular food prices.

The research focuses on the expected change in the local food system following Lebanon's geopolitical turbulence, such as the 2019 October Revolution and the August 2020 Beirut port disaster. On October 17, 2019, a social movement burst forth in Lebanon. This movement catalyzed an economic and political shift in Lebanon. Hundreds of thousands of people felt that the system was flawed (Chehayeb and Sewell, 2019). Popular voices rejected unbearable austerity measures, especially for the poor who struggled to meet their basic needs. The country's deepening economic crisis was further aggravated by the rising public debt and excessive reliance on remittances and the crisis in the banking and services sectors rather than the agriculture or industry. The October Revolution led to a new government under Prime Minister Hassan Diab, which announced an economic rescue plan to save Lebanon economically, financially, and socially. The proposed reforms would restructure the Lebanese economy with increased government support for agriculture and manufacturing, where local production was encouraged over imports (International Crisis Group, 2020). After the Beirut explosion, Hassan Diab resigned on August 10, 2020, following a series of political failures that hindered any progress in the proposed economic reforms (Azhari, 2020a). The hyperinflation and compounded crises that followed were clear indicators of the failure of the rescue plan. Nevertheless, the plan itself highlighted a shift in economic strategy, which would require decades to fix the damages of the past.

Private agricultural input companies have stimulated and maintained the agricultural sector in Lebanon ever since the Civil War; however, in the face of the fiscal crisis, they have lacked cohesion and cooperation in preventing the dismantlement of the agricultural sector since 2019. This failure has its roots in the 1992 reform that converted cash sales into credit sales. In the absence of low interest on state-supported agricultural credit, importers provided input working capital to retailers and farmers. Farmers could not repay their loans due to poor agricultural returns, which increased their debt year after year. By October 2019, agricultural inputs reached about 80 m USD, where farmers' debt to retailers reached 60 m USD. Since farmers are usually marginalized from borrowing capital from the bank, agricultural input suppliers and retailers held default risk to maintain their client base. Agricultural input suppliers have been responsible for maintaining the agricultural sector since the government has been negligent. Thus, the actual debt was obliged to them, which farmers failed or struggled to pay back, and the debt owed to the banks had accumulated without control. Finally, the financial system of Lebanese agriculture secured by importers collapsed2.

Lebanon's agricultural sector relies heavily on fuel and agricultural inputs. Agricultural inputs, including seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, irrigation equipment, and machinery, are mostly, if not all, imported through local agricultural inputs companies and sold directly to farmers or agricultural pharmacies. Since the October Revolution, the price of agricultural inputs had skyrocketed, and farmers had trouble transporting and selling their products. Farmers witnessed that the price of inputs and the cost of their operations had significantly increased. The price surge would lead to transformations in the sector, where farmers would rely less on the tools derived from the Green Revolution. They might resort to more organic or natural products for value-added products or resort to cash crops that can be imported or feedstock for local livestock production, where value has increased drastically due to currency inflation. However, most farmers, i.e., conventional farmers that will remain dependent on those tools, will lead to an overall increase in food prices, especially for locally grown fruits and vegetables. Regional produce would be easier to penetrate the local market due to lower production costs. Conventional farmers that usually pay agricultural input companies on a credit basis would struggle. Since banks disfavor agricultural loans to small and medium farmers, this will transform agricultural input companies into agricultural banks to maintain business operations, revitalizing the financial failure of the past. Those farmers who resist adaptation will eventually have to forfeit their agricultural operations, where larger or corporate farmers might take advantage of the situation and procure more agricultural land from the small and medium farmers, creating a corporate-feudalistic land ownership model. The government can prevent this model by promoting, investing, and intervening in policies and projects pertaining to agriculture, agroindustry, and agricultural trade.

The financial cycle of the agricultural value chain was further affected by the structure of the fresh produce wholesale market, whereby traders dealt with farmers on a consignment basis on a deferred payment basis, paid in the devaluating local currency. The fresh produce wholesale market is considered the main contributor to the inefficiency in the horticultural supply chain (Mukahhal et al., 2022). However, the “fiscal crisis of 2019 combined with banks blocking credit to wholesalers, created a liquidity vacuum with delayed payments to farmers”2. The expected impacts of the financial crisis include lower yields, quality, and quantity, but more importantly, increased social unrest in the agricultural and rural communities until the stability of the Lebanese LBP and cash operations resume utilizing the local currency. The free market became uncoordinated and inefficient, and the government's negligence of agriculture made the sector unable to compete with subsidized global agro-production and emerging global food standards. As a result, between 2018 and 2020, the value of field crops production was projected to decrease by almost 70% (cereals 64%, potatoes 72%, and onions 61%); vegetables and flowers by 44%, and forest products and prohibited crops by 39–40%2.

Lebanon was already suffering from rising gasoline and wheat prices before the October Revolution. Rather than acting as a shifting point to the country's socioeconomic and political discourse, the financial and economic situation further deteriorated. Monetarily, the availability of USD in the market plummeted, resulting in rising pressure on the LBP and informal market depreciation. Purchasing power dropped, and the price of imported items such as fuel, wheat, medicine, and agricultural inputs has increased substantially. Food insecurity is expected to rise due to a spike in poverty, inflation, and unemployment, where subsidizing these imported commodities would be later intolerable to the government (World Bank, 2019; Chehayeb, 2020; WFP, 2020). The reliance on food imports and aid is expected to increase drastically, especially after the Beirut Port Explosion.

The economic crisis in Lebanon encourages reducing imports, increasing investments in production, and re-exploring trade routes. Corporate food institutions in Lebanon import items and thus will have to incur a higher cost to supply these products. Companies either must increase their prices on items that cannot be usually substituted or delist items that other or local providers can substitute. This means less diversity and availability for customers due to reduced purchasing power.

The fiscal crisis during the October Revolution harmed the food retail sector and producers, where sales and profits for food companies decreased due to a decrease in purchasing power, hyperinflation, and bank control on withdrawals. People were buying less, which led companies to reduce their purchasing capacity from producers or suppliers. The depreciation of the local currency extended to imported commodities priced in USD, leading to price inflation. Also, local production has increased in price simply because the raw material used in production also is imported, such as gasoline, agricultural inputs, and packaging or raw materials. The deteriorating economic situation forced supermarkets and corporate foodservice operators to procure substitutes from local or regional sources rather than from the accustomed global supply chain (Saadi, 2001). Nevertheless, the October Revolution may prove a pivotal point that would force the country into a more sustainable food regime since Lebanon is import-dependent on its foodstuff, medicine, fuel, and raw material.

As of 2018, Lebanon was already the third most indebted country globally, with a 151% debt-to-GDP ratio. This is expected to increase dramatically due to the recession, instability, and emergency. As of December 2019, Lebanon's trade deficit reached USD 14.81 billion. At the same time, public debt reached its highest (valued at around 122,473 billion LBP) (Trading Economics, 2020). As of 2020, Lebanon's nominal debt-to-GDP ratio increased to 171.70% (CEIC Database, 2020).

Along with the crisis, a new government was formed in January 2020 and tasked with rescuing Lebanon from the economic crisis by designing policies such as legalizing cannabis production for medical and industrial purposes and providing liquidity for manufacturers to promote local production. Furthermore, the primary limiting factor faced by Lebanese producers is a lack of clear agricultural policies and frameworks. In parallel, the reduction of foreign aid was realized during the Trump Administration. Also, Europe's and Saudi Arabia's support declined due to the rise of a predominant internationally unfavorable parliamentary block in the Lebanese government. This suggests a political shift in allegiances leading to a change in policies and international trade.

On August 4, 2020, a massive explosion erupted in the port of Beirut. Human lives were lost, infrastructure was damaged, and people lost their homes. The relevance of this event to understanding food regime analysis can be correlated to the socio-geopolitics implications involved. The explosion was attributed to the same reason that led to the October Revolution, i.e., corruption and institutional failure. The catastrophe became a geopolitical opportunity. Public relations deteriorated as all trust was lost until major institutional and economic reforms were adopted by the country's leadership (Azhari, 2020a). The country's foreign aid was no longer readily available until a change in leadership came into effect, which was satisfactory to the international community, France, and the US. The decision had drastic events on the Lebanese population due to currency hyperinflation, economic depression, and political unrest to pressure the leadership to change (Azhari, 2020b). However, no institutional change was apparent by the leadership. Thus, the consequences of this simulated embargo chipped away the socioeconomic security of the entire nation, but more so to the lower-middle class, foreign domestic workers, producers, and traders.

Conclusion

The study has provided a historical construction of global food regime changes and the adaptiveness and transformability of the local food system. The historical events discussed in this study have considerably decreased farming households' influence on policies and the political commitment to support agriculture. Also, the case study in Lebanon demonstrates what happens when the prevalent food system fails amidst global recession and geopolitical turbulence. The failure marks a pivotal event that signals a chain of internal socioeconomic and political failures. The picture unfolds and requires a view of the long run to explain the developing food regime paradigm.

The food regime theory facilitated our understanding of the transformation of the local food system in Lebanon. The fundamental historical construction relies on the food regime changes stirred by global geopolitical events and their influence on the social, economic, and political fabrics of the local food system. In terms of adaptiveness, the study has provided some evidence of how the retail concepts have existed for centuries in the form of merchants or “Dekkene”. For example, farmers adapted to the change in the French demand for silk and the embargo in World War I (leading to a great famine) by changing from a monoculture of mulberry trees to more fruits and vegetable production to feed the population and replace the alternating global demand. More specifically, the study has interpreted Lebanese contemporary and agrarian history within the framework of food regime analysis and geopolitical events to bring together non-Middle Eastern centered work on the food system transformation with that of the Middle Eastern context, which is understudied. The paper provides insights for future food policy responses to transform the local food system amidst crisis and geopolitical turbulence.

The historical contextualization of food system changes may provide important lessons to revitalize agriculture and overcome the failures of the global food system in Lebanon. The Green Revolution has had a significant impact on food system changes due to the increased influence of agrochemical companies. Furthermore, the food system linked to corporate buyers has excluded small family farmers, which constitute the core of the Lebanese agricultural landscape (Mukahhal et al., 2022). Although the local food system remained resilient., there is a need for alternative routes to increase the competitive position of local food systems by taking advantage of current trends toward local foods (Abebe et al., 2022). Different approaches can be applied to create direct links and promote co-investment within the local food system, including farmers' markets and community-supported agriculture. In addition, the family-based agrarian structure and beautiful natural landscapes can provide excellent opportunities for promoting agro-tourism in Lebanon.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

WM gathered data and authored the first draft. GA guided research design and data collection and authored the final draft. RB and GM assisted the study design and peer-reviewed the final draft. All authors approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^https://www.aub.edu.lb/fafs/news/Documents/2020News/DIAGNOSIS%20OF%20LEBANESE%20AGRICULTURE.pdf

2. ^https://www.aub.edu.lb/fafs/news/Pages/2020_RiadFouadSaade.aspx

References

Abebe, G. K., Traboulsi, A., and Aoun, M. (2022). Performance of organic farming in developing countries: a case of organic tomato value chain in Lebanon. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 1-10. doi: 10.1017/S1742170521000478

AbuKhalil, A. (2005). Lebanon: Key Battleground for Middle East Policy. Available online at: https://ips-dc.org/lebanon_key_battleground_for_middle_east_policy/. Institute for Policy Studies (accessed September 15, 2021).

Addis, C. L. (2011). Lebanon: Background and U.S. Relations. Congressional Research Service. R40054. Available online at: https://sgp.fas.org/crs/mideast/R40054.pdf (accessed July 10, 2021).

Al Dirani, A., Abebe, G. K., Bahn, R. A., Martiniello, G., and Bashour, I. (2021). Exploring climate change adaptation practices and household food security in the Middle Eastern context: a case of small family farms in Central Bekaa, Lebanon. Food Sec. 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s12571-021-01188-2

Azhari, T. (2020a). US Caesar Act Could Bleed Lebanon for Years to Come. Available online at: https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2020/6/19/us-caesar-act-could-bleed-lebanon-for-years-to-come, AL JAZEERA (accessed October 08, 2020).

Azhari, T. (2020b). Lebanon PM Hassan Diab Expected to Announce Resignation. Available online at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/8/10/lebanon-pm-hassan-diab-expected-to-announce-resignation, AL JAZEERA (accessed October 08, 2020).

Bahn, R. A., and Abebe, G. K. (2017). Analysis of food retail patterns in urban, peri-urban and rural settings: A case study from Lebanon. Appl. Geogr. 87, 28-44. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2017.07.010

Bergman, H. (2020). The Art of Reconciliation-Understanding art From the October Revolution Through Multimodal Discourse Analysis as a Part of a Reconciliation Process in Lebanon., LUP Student Papers. Lund University. Available online at: https://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=9011310&fileOId=9011314 (accesed Decemeber 25, 2020).

Bernstein, H. (2015). Food Regimes and Food Regime Analysis: a Selective Survey. Working Paper 2. Available online at: https://www.tni.org/files/download/bicas_working_paper_2_bernstein.pdf (accessed February 10, 2020).

Bernstein, H. (2016). Agrarian political economy and modern world capitalism: the contributions of food regime analysis. J. Peasant Stud. 43, 611–47. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2015.1101456

Bryson, T. A. (1980). Tars, turks, and tankers: the role of the United States Navy in the Middle East, 1800-1979. Naval War Coll. Rev. 33, 11. Available online at: https://primo-pmtca01.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/primo-explore/fulldisplay/01SFUL_ALMA21145041930003611/SFUL

CEIC Database (2020). Lebanon Government Debt: % of GDP. Available online at: https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/lebanon/government-debt–of-nominal-gdp (accessed April 4, 2020).

Chehayeb, K. (2020). Beirut blast worsens Lebanon's already concerning food crisis. The Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy. Available online at: https://timep.org/commentary/analysis/beirut-blast-worsens-lebanons-already-concerning-food-crisis/ (accesed December 15, 2020).

Chehayeb, K., and Sewell, A. (2019). Why Protesters in Lebanon Are Taking to the Streets. Available online at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/11/02/lebanon-protesters-movement-streets-explainer/, Foreign Policy (accesed December 05, 2020).

Clapp, J., and Moseley, W. G. (2020). This food crisis is different: COVID-19 and the fragility of the neoliberal food security order. J. Peasant Stud. 47, 1393–1417. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2020.1823838

Collelo, T. (1989). Lebanon, a country study (3rd. ed.). Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. Library of Congress. Federal Research Division. Available online at: https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/frd/frdcstdy/le/lebanoncountryst00coll/lebanoncountryst00coll.pdf (accesed March 21, 2019).

Dörr, F. (2018). “Food Regimes, Corporate Concentration and Its Implications for Decent Work”, in Decent Work Deficits in Southern Agriculture. Augsburg, München: Rainer Hampp Verlag, Scherrer, C., Verma, S. (Eds.). p. 178–208. Available online at: https://kobra.uni-kassel.de/bitstream/handle/123456789/2018041755357/LaborAndGlobalizationVol11.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

FAO (2017). Study of small-scale family farming in the Near East and North Africa: Focus country: Lebanon [Étude sur l'agriculture familiale a petite échelle au proche-orient et afrique du nord pays focus Liban]. Rome: FAO, CIHEAM-IAMM, and CIRAD. Available online at: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i6608f.pdf [accesed May 15, 2021].

FAO (2018). Sustainable food systems: Concept and framework. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Available online at: http://www.fao.org/3/ca2079en/CA2079EN.pdf (accessed September 25 2021).

Fawaz, L. (1984). The City and the Mountain: Beirut's political radius in the nineteenth century as revealed in the crisis of 1860. Int. J. Middle East Stud. 16, 489–495. doi: 10.1017/S002074380002852X

Fenby, J. (2018). Crucible: The Year that Forged our World. Britain, United Kingdom: Simon & Schuster Ltd.

Firro, K. (1990). Silk and agrarian changes in Lebanon, 1860-1914. Int. J. Middle East Stud. 22, 151–169. doi: 10.1017/S0020743800033353

Friedmann, H. (2005). From colonialism to green capitalism: Social movements and emergence of food regimes. Res. Rural Sociol. Dev. 11, 227. doi: 10.1016/S1057-1922(05)11009-9

Heffernan, W. D., and Constance, D. H. (1994). “Transnational corporations and the globalization of the food system,” in From Columbus to ConAgra: The globalization of agriculture and food, ed. Bonnano, A., et al. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press. p. 48–64.

International Crisis Group (2020). Pulling Lebanon out of the Pit. Middle East & North Africa, Report number 214. Available online at: https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/eastern-mediterranean/lebanon/214-pulling-lebanon-out-pit (accessed October 14, 2020).

Karsh, E., Kerr, M., and Miller, R. (2013). Conflict, Diplomacy and Society in Israeli-Lebanese Relations. Oxfordshire: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315875484

Lune, H., and Berg, B. L. (2017). Social Historical Research and Oral Traditions. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences 9th ed. Pearson Education Limited. Long Beach: California State University.

Magnan, A. (2012). “Food regimes,” in The Oxford Handbook of Food History, Pilcher, J. M. (Ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 370–388. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199729937.013.0021

Manganelli, A., Van den Broeck, P., and Moulaert, F. (2020). Socio-political dynamics of alternative food networks: a hybrid governance approach. Territ. Politic. Gov. 8, 299–318. doi: 10.1080/21622671.2019.1581081

McMichael, P. (2005). Global development and the corporate food regime. Res. Rural Sociol. Dev. 11, 265. doi: 10.1016/S1057-1922(05)11010-5

McMichael, P. (2009). A food regime genealogy. J. Peasant Stud. 36, 139–169. doi: 10.1080/03066150902820354

Meyer, M. A. (2020). The role of resilience in food system studies in low- and middle-income countries. Glob. Food Sec. 24, 100356. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100356

MOA (2020). Lebanon National Agriculture Strategy 2020 - 2025. Available online at: http://www.agriculture.gov.lb/getattachment/Ministry/Ministry-Strategy/strategy-2020-2025/NAS-web-Eng-7Sep2020.pdf?lang=ar-LB (accessed March 25, 2021).

Monteiro, C. A., Moubarac, J. C., Cannon, G., Ng, S. W., and Popkin, B. (2013). Ultra-processed products are becoming dominant in the global food system. Obesity Rev. 14, 21–28. doi: 10.1111/obr.12107

Mukahhal, W., Abebe, G. K., and Bahn, R. A. (2022). Opportunities and challenges for lebanese horticultural producers linked to corporate buyers. Agriculture. 2022, 12, 578. doi: 10.3390/agriculture12050578

Nasr, S. (1978). Backdrop to civil war: the crisis of Lebanese capitalism. Merip Rep. 3–13. doi: 10.2307/3012262

Office of the Historian (n.d). USAID PL−480 1961–1969. Available online at: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1961-1968/pl-480 (accessed November 20 2020).

Reardon, T., and Hopkins, R. (2006). The supermarket revolution in developing countries: policies to address emerging tensions among supermarkets, suppliers and traditional retailers. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 18, 522–545. doi: 10.1080/09578810601070613

Reardon, T., Timmer, C. P., Barrett, C. B., and Berdegue, J. (2003). The rise of supermarkets in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Am. J. Agri. Eco. 85, 1140–1146. doi: 10.1111/j.0092-5853.2003.00520.x

Roland Riachi, R., and Martiniello, G. (2019). The Integration of the Political Economy of Arab Food Systems Under Global Food Regimes. Available online at: https://www.annd.org/data/file/files/6%20The%20Integration%20of%20the%20Political%20Economy%20of%20Arab%20Food%20Systems%20Under%20Global%20Food%20Regimes.pdf (accessed November 14, 2021).

Rosiny, S. (2013). Power sharing in syria: lessons from lebanon's taif experience. Middle East Policy. 20, 41–55. doi: 10.1111/mepo.12031

Ryan, C. (2012). The new Arab cold war and the struggle for Syria. Middle East Rep. 262, 28–31. Available online at: https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/asu/f/Ryan_Curtis_2012_RECAPP_New%20Arab%20Cold%20War.pdf (accessed January 17, 2021)

Saab, A. (2018). An international law approach to food regime theory. Leiden J. Int. Law. 31, 251–265. doi: 10.1017/S0922156518000122

Saadi, D. (2001). Sugar Beet Farmers Bitter About End to Subsidies. Retrieved from www.dailystar.com.lb/Business/Lebanon/2001/Apr-25/14102-sugar-beet-farmers-bitter-about-end-to-subsidies.ashx (accessed December 02, 2019).

Salih, S. (1977). The British-Druze connection and the Druze rising of l896 in the Hawran. Middle Eastern Stud. 13, 251–257. doi: 10.1080/00263207708700349

Salti, N., Chaaban, J., and Naamani, N. (2014). The economics of tobacco in Lebanon: an estimation of the social costs of tobacco consumption. Sub. Use Misuse. 49, 735–742. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.863937

Seyfert, K., Chaaban, J., and Ghattas, H. (2014). “Food security and the supermarket transition in the Middle East: Two case studies,” in Food Security in the Middle East, ed. Babar, Z., Mirgani, S. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Søndergaard, N. (2020). Food regime transformations and structural rebounding: Brazilian state–agribusiness relations. Terri. Polit. Gov. 1–20. doi: 10.1080/21622671.2020.1786447

Tilzey, M. (2018). Political Ecology, Food Regimes, and Food Sovereignty. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Tilzey, M. (2019). Food regimes, capital, state, and class: Friedmann and McMichael revisited. Sociologia Ruralis. 59, 230–254. doi: 10.1111/soru.12237

Trading Economics (2020). Lebanon. Available online at: https://tradingeconomics.com/lebanon/balance-of-trade (accessed October 14, 2021).

von Braun, J., Afsana, K., Fresco, L. O., Hassan, M., and Torero, M. (2021). Food system concepts and definitions for science and political action. Nat. Food 2, 748–750. doi: 10.1038/S43016-021-00361-2

Weissbrodt, D., and Kruger, M. (2003). Norms on the responsibilities of transnational corporations and other business enterprises with regard to human rights. Am. J. Int. Law. 97, 901–922. doi: 10.2307/3133689

WFP (2020). World Food Programme to scale up in Lebanon as blast destroys Beirut's port. Available online at: https://insight.wfp.org/world-food-programme-to-scale-up-in-lebanon-as-blast-destroys-beiruts-port-7270471d1f87 (accessed December 10, 2020).

World Bank. (2019). World Bank: Lebanon is in the Midst of Economic, Financial and Social Hardship, Situation Could Get worse. Available online at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2019/11/06/world-bank-lebanon-is-in-the-midst-of-economic-financial-and-social-hardship-situation-could-get-worse (accessed February 14, 2021).

Zhang, J. B. (2019). Top 20 global seed companies in 2018 – two megacorps, four supercorps and differentiated development. Available online at: news.agropages.com/News/NewsDetail–32780.htm AgNews (accessed November 19, 2020).

Keywords: local food system, food regime, globalization, geopolitics, geoeconomics, Lebanon

Citation: Mukahhal W, Abebe GK, Bahn RA and Martiniello G (2022) Historical Construction of Local Food System Transformations in Lebanon: Implications for the Local Food System. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 6:870412. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2022.870412

Received: 06 February 2022; Accepted: 27 April 2022;

Published: 26 May 2022.

Edited by:

Paswel Phiri Marenya, The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), KenyaReviewed by:

Viswanathan Pozhamkandath Karthiayani, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham (Amritapuri Campus), IndiaJeetendra Prakash Aryal, International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center, Mexico

Copyright © 2022 Mukahhal, Abebe, Bahn and Martiniello. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gumataw Kifle Abebe, Z3VtYXRhdy5hYmViZUBkYWwuY2E=

Walid Mukahhal1

Walid Mukahhal1 Gumataw Kifle Abebe

Gumataw Kifle Abebe