- Department of Health Sciences, Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, ON, Canada

The proliferation of food policy councils (FPCs) in the past two decades has been accompanied by increasing academic interest and a growing number of research studies. Given the rapid interest and growth in the number of FPCs, their expanding geographic distribution, and the research on their activities, there is a need to assess the current state of knowledge on FPCs, gaps in that knowledge, and directions for future research. To address this need, we undertook a scoping review of the scholarly literature published on FPCs over the past two decades. The review identified four main themes in the FPC research—(1) Activities of FPCs; (2) Organizational dimensions; (3) Challenges; and, (4) Facilitators. We also note a significant sub-theme related to equity and diversity, race and class representation in FPCs. These themes frame a growing body of knowledge on FPCs along with key gaps in the current body of literature, which may help to direct research on these organizations for those interested in approaches to food systems change and cross-sectoral collaborative approaches to social-ecological governance.

Introduction

In the past two decades, cities and regions across North America, Europe, the United Kingdom, and Australia have established food policy councils (FPCs) as an approach to addressing the multitude of issues that impact a community's food systems (from production and harvesting to consumption and waste management). FPCs can be defined as collaborative, membership-driven organizations that bring together stakeholders across private (e.g., small businesses, industry associations), public (e.g., government, public health, postsecondary institutions), and community (e.g., non-profits and charitable organizations) sectors to examine opportunities to implement integrated strategies for improving local and regional food systems. Key characteristics of FPCs–which differentiate them from other food systems organizations–are: (1) their use of a cross-sectoral committee to guide decisions and activities; and, (2) their use of a food systems approach (i.e. they focus on a variety of food issues and are not limited to one specific area of concern such as nutrition or agriculture).

The first FPC was established in 1982 in Knoxville Tennessee, with a few additional FPCs emerging throughout the 1990s. The initial creation was spurred by events such as the World Fair (hosted in Knoxville in 1982) and the United States Conference of Mayors (1984–1985) which urged municipal leaders to become more involved in developing and shaping policy around food issues. Other catalyzing moments included the development of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion in 1986 and the World Health Organization's Healthy Cities program. Throughout the 1980s, the significant rise in the demand for emergency food due to increased poverty–paralleled by drastic cuts in social services, forced cities to consider how to address a mounting food security crisis (Riches, 2018). By the early 2000s, many FPCs were established and by 2007, there were about 44 of these organizations distributed primarily across North America, with a few in Europe and Australia (Schiff, 2007). By 2020 FPCs had proliferated: the Food Policy Networks project (operated through the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future) identified over 350 FPCs across North America [Centre for a Livable Future, (n.d.)]. Most FPCs operate at local/municipal level with a few working at a regional or state/provincial scale. In 2021, the Canadian federal government created a National Food Policy Advisory Council to support cross-sectoral collaboration and engagement at a national level and to support the implementation of the new Food Policy for Canada.

There were a few studies of early FPCs in the 1980s and 90s in the U.S. and Canada (Clancy, 1988; Dahlberg, 1994a,b; Yeatman, 1994; Gottlieb and Fisher, 1995; Webb et al., 1998) and Australia (Yeatman, 1995; Hawe and Stickney, 1997). The proliferation of FPCs in the past two decades has been accompanied by increasing academic interest and a growing number of research studies. Given the rapid interest and growth in the number of FPCs, their expanding geographic distribution, and the research on their activities, we identified a need to systematically assess the current state of knowledge on FPCs and gaps in that knowledge. As such, we implemented a scoping review methodology to systematically assess the scholarly literature published on FPCs over the past two decades (1999–2019).

Methods

We utilized the five-stage process for conducting scoping reviews as outlined by Arksey and O'Malley (2005). Below, we discuss the five stages and describe our specific approach.

Research Question

Three research questions guided this scoping review:

a) What are the major themes in research on FPCs in the past two decades (i.e., published between 1999–2019)?

b) What methods have been employed in the study of FPCs in the past two decades?

c) What gaps and directions for further research are suggested by the research on FPCs?

Literature Search Strategy

Our initial search included five databases for identification of peer-reviewed journal articles: The Web of Science, Food Science Source, AGRICOLA, FSTA, and Greenfile. To search for chapters in academic books, we utilized Omni library portals. We also included publications from the Johns Hopkins Annotated Bibliography on Existing, Emerging, and Needed Research on Food Policy Groups (Santo et al., 2017). Databases were searched using the keywords “food policy” AND “council” or “committee” or “association” or “coalition” or “alliance” or “network”. The search was limited to literature published between 1999 and 2019.

Study Selection Criteria

We engaged in three stages of review (title review, abstract review, full content screening) to refine the results to our specific topic. In the title review stage, titles were included if they mentioned food policy, FPCs, or synonymic terms such as food policy groups, associations, councils, etc. Additionally, titles with related concepts such as food security, food democracy, wellness committees, and urban food systems merited further review, and were forwarded to abstract screening. The abstract review stage focused on identifying articles that discussed FPCs as defined by our definition which is found in the first paragraph of this article. Abstract review screened out those articles which might have focused on organizations that did not fit with the FPC definition–such as food systems non-profits that do not use a cross-sectoral council to guide their activities or government committees that are focused narrowly on one specific aspect of the food system. Full text screening focused on identifying articles where FPCs were the primary/exclusive focus. This stage screened out articles where FPCs were only briefly discussed or were review articles that did not present empirical research findings. This resulted in the final list that was used for content analysis to answer the research questions.

Data Charting

Data was captured in a Microsoft Excel workbook with two spreadsheets. The first spreadsheet included all articles identified in the initial search. This sheet tracked: author; year; title; citation; database/source. Following title and abstract screening, a secondary sheet included those articles that had passed the initial screening process. This sheet documented: study location; synopses; major findings for each publication. A third sheet (with the same fields as the second sheet) was created for the final list, which included all articles identified as relevant after full content review.

Summarizing and Report Results

All three authors of this article were involved with analysis and reporting. All authors reviewed all articles in the final list using an inductive approach to interpretive content analysis (Drisko and Maschi, 2016) to identify key themes related to our three research questions. This analysis was guided by the following focus as defined by our research questions: thematic organization of the existing literature, description of methods used to study FPCS, identify gaps and potential direction for future FPC research. The authors met to merge the results of individual inductive analysis into a single coding scheme. This was accomplished by identifying common themes identified in the individual inductive analyses and applying codes (thematic titles) which captured those common themes. The codes that emerged through merging of the individual inductive interpretive analysis included:

• Research Question 1: impacts / effectiveness; organizational dimensions; FPC activities

• Research Question 2: geographic scale; scope; methods

• Research Question 3: researcher identified gaps and recommendations.

Each of these codes also contained sub-codes which are discussed in detail in the results section. We also included a code for a small amount of data which could not be categorized within these themes. We then utilized this coding scheme to review all publications in the final list and to categorize data. We also analyzed results for any additional potential gaps in research that are not identified in the existing literature.

Results

Our initial search yielded 2,239 unique peer-reviewed journal articles, 578 book chapters, and an additional 16 articles/chapters from the Johns Hopkins database. Following full content screening our final list yielded a total of 25 articles. Five of these articles were published between 1999 and 2009 when the number of FPCs was still relatively small−44 FPCs in North America as per Schiff (2007). The increase in studies on FPCs between 2009 and 2019 may be related to the rapid increase in the number of these organizations during that time period.

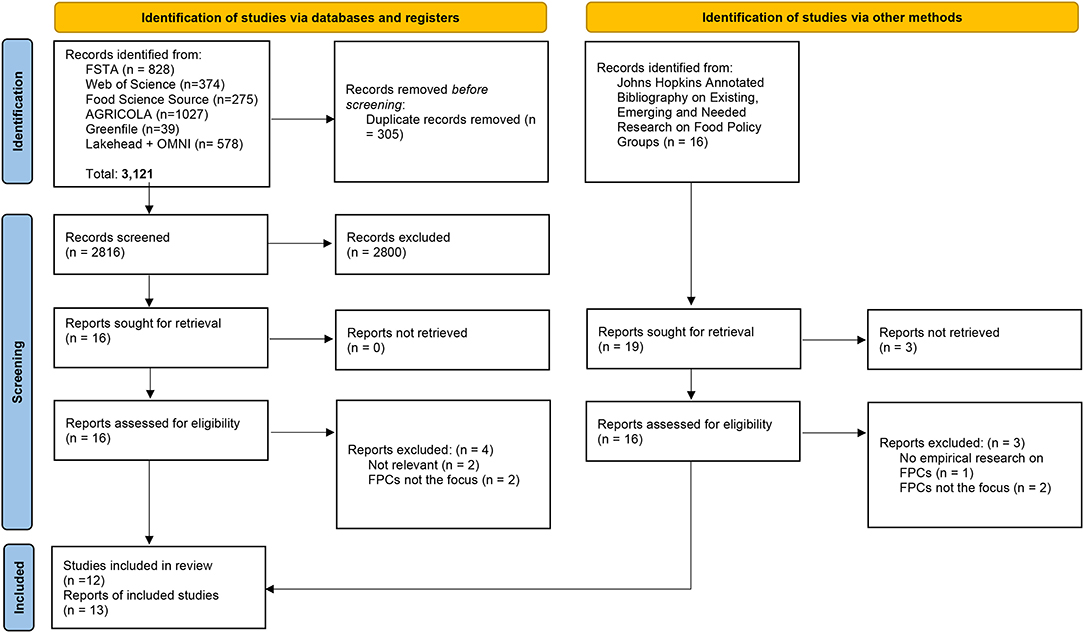

The scoping review search strategy and selection process are summarized in Figure 1. The 25 articles which met the scoping review criteria are accompanied by an asterisk (*) in the reference list at the end of the article. For the purposes of this article, we refer to all articles/chapters as “articles” in the findings and discussion.

Figure 1. Details of scoping review and citation selection process. Adapted from: Page et al. (2021).

The interpretive content analysis resulted in coding structure around four key themes in the research on FPCs in the past 20 years: (1) Activities of FPCs; (2) Organizational dimensions; (3) Challenges; and, (4) Facilitators. A theme related to “methods employed in the study of FPCs” is included in our findings and “researcher recommendations” is included in our final discussion section. We note that this analysis was not analyzing FPCs themselves but rather was analyzing the ways in which the FPC literature (from empirical studies) discusses and analyzes FPCs. In other words–the purpose of this article was not to provide a detailed description or definition of FPCs. The purpose of this work was to thematically organize literature on FPCs to identify what is known and how this reveals gaps in knowledge and directions for future research.

Findings

Methods Employed in the Study of FPCs

As mentioned above, codes included documentation of geographic scale, scope, and methods. In relation to methods, of the 25 articles/chapters included, the majority (17) used a case study methodology. Many case studies used mixed methods which included semi structured interviews, participant observation, field notes and document review. Other methods included structured surveys or large numbers of FPCs and multi-site comparative case studies.

In terms of geographic scale, 12 articles/chapters exclusively examined FPCs operating at a municipal/local level. Three focused exclusively on FPCs operating on a regional or state/provincial scale. The remaining 10 examined FPCs operating at different levels – i.e. included examination of FPCs at municipal, regional, and state levels in one study. In terms of geographic scope, most articles (17) reported on research conducted in the United States. Three articles reported on research conducted in Western European countries, one article on research in Australia, and five from Canada. Two articles compared FPCs in different countries. Thirteen articles focused on a single FPC, while the others included between two and 56 FPCs in their research.

Activities of FPCs–What FPCs Do

Much of the research on FPCs focused on an examination of what FPCs do and specifically on their various activities. As the very nomenclature suggests a focus on policy (change) there is indeed a considerable amount of literature focusing on the policy work of FPCs. There is however also significant documentation of a wide range of other kinds of activities that go well beyond policy-specific work. In this subsection, we describe the ways in which FPC activities are documented and discussed in the articles.

Policy Specific Activities

Early literature on FPCs (Dahlberg, 1994a,b; Yeatman, 1994) indicated that impacting and influencing food related policy at a municipal, regional, or state level is a key priority for many FPCs–this theme was also evident in our review and analysis of the FPC literature. This might include policies that relate to food directly (e.g., retail zoning, food related funding, food safety bylaws, etc.) or indirectly (e.g., transportation, use of public space, etc.). In the articles reviewed, FPC policy work primarily included activities such as drafting resolutions, reports, and proposals for and with governments (Lang et al., 2005; Blay-Palmer, 2009; Scherb et al., 2012; Coplen and Cuneo, 2015; Siddiki et al., 2015; Clark, 2018; Koski et al., 2018). Other policy activities included advocating for food-related issues (Blay-Palmer, 2009; Purifoy, 2014), creating legislation to create an FPC within government (De Marco et al., 2017) and working to amend zoning laws (McClintock et al., 2012). Many of the articles on municipal FPCs (10 of 12) include some focus on policy change to support urban agriculture.

While many FPCs engage in policy work, some articles (4) noted FPCs that do not prioritize this type of work. The articles in this review reported that some FPCs have members that (despite the nomenclature) are not directly interested in policy work and prefer to focus on project development and implementation. Newer FPCs sometimes have concerns that their recent emergence—being a new entity with lower levels of recognition among policymakers and less political capital—was a potential hindrance to their impact on policymaking (Sieveking, 2019). Similarly, McCartan and Palermo (2017) found that some FPCs viewed policy change as a long-term goal that required a more established council to have an impact (McCartan and Palermo, 2017). For some FPCs, policy work was simply not a part of their goals (Packer, 2014).

Other Activities

For many FPCs, policy work is a priority, however most articles described FPCs pursuing non-policy initiatives. Gupta et al. (2018) note, “research makes it clear that the FPC label is being applied to collaborations that engage in a diverse and wide-ranging set of activities, not all of which involve…policies” (p. 13). Schiff (2008) categorized the various types of non-policy work that FPCs engaged in, including: implementing food (nutrition; urban food production; other (farm and fisheries) production; distribution) programs; creating and facilitating a network for food systems organizations; facilitating program implementation for food systems organizations, and; education on sustainable food systems.

Supporting urban agriculture was a theme of several (5) articles. Blay-Palmer (2009) described the work of the Toronto Food Policy Council (TFPC), that included the creation of more opportunities for producers to sell their food, leading the implementation of urban agriculture projects such as rooftop gardens, and urban apiaries, and demonstrating the importance of urban agriculture for the city council (Blay-Palmer, 2009). Other articles describe similar urban agriculture initiatives undertaken by the Oakland FPC (McClintock et al., 2012), Ghent FPC (Prové et al., 2019), Portland Multnomah FPC (Coplen and Cuneo, 2015) and many others (Scherb et al., 2012).

Purifoy (2014) highlighted other, diverse non-policy activities of several FPCs–describing FPCs as ideal institutions to integrate action on food, environment, and social justice issues. These activities included the creation of opportunities for green grocers in New Orleans, sustainable agriculture on public lands in Colorado and New York, and farm to school programs by FPCs in New Mexico and Mississippi. Sands et al. (2016) described the role of the Holyoke Food and Fitness Policy Council in supporting school food programs, which fostered public awareness of local food issues by working with community members and made significant improvements to the quality of food served in local schools.

As Schiff (2008) notes, many FPCs focus on education as a key activity and outcome of their work. This is echoed in other articles, such as Packer (2014) who noted that the Rhode Island FPC participated in regional research and action groups with the goal of food systems education. Other research points to FPC work on educating and raising awareness among policymakers about interconnected food system issues. This was identified by Walsh et al. (2015) in their study of the Cleveland–Cuyahoga County Food Policy Coalition, as well as by Sieveking (2019) in the study of the Oldenburg FPC. The Oldenburg FPC also had a strong focus on community education and awareness and supported initiatives such as “Political Soup Pots” where community members could gather to discuss food systems issues and educational activities in schools (Sieveking, 2019).

Organizational Dimensions–Effects on FPC Impact and Effectiveness

Many of the articles reviewed focused on analysis of the organizational dimensions of FPCs. By organizational dimensions we refer to the ways in which FPCs are structured and governed. This literature was often accompanied by a focus on how organizational dimensions affected the activities of FPCs or how they impacted the effectiveness of FPCs in achieving their stated goals. The literature on FPC organizational dimensions included themes related to memberships and partnerships, relationships with government, and internal governance. We also note that, within the discussions of membership and partnerships, there was a sub–theme that emerged focused on equity, diversity, race and class.

Partnerships/Membership

Every article we reviewed mentioned the partnerships and memberships that make up the FPCs. Diversity in partnerships/membership was portrayed in two ways: (1) sector diversity and (2) social (race and class) diversity.

Many (12) articles described a deliberate effort from FPCs to ensure that a diversity of sectors were represented. Most of these articles (8) noted that members were appointed to ensure representation from across the food system and from the public, private, and charitable sectors (Blay-Palmer, 2009; Scherb et al., 2012; McCartan and Palermo, 2017; Clark, 2018; Koski et al., 2018; Baldy and Kruse, 2019; Bassarab et al., 2019; Sieveking, 2019). For example, in a study of 10 FPCs, Gupta et al. (2018) noted that all had involvement from local government employees. The most frequently represented agencies included Cooperative Extension, public health, environmental health, and the Agricultural Commissioner Office.

In addition to discussions of diversity in membership across food systems sectors, some articles (5) discussed other elements of membership diversity–particularly in relation to race and class representation. More specifically, some articles indicated that many FPCs are predominantly composed of white, middle-class professionals from similar socioeconomic and educational backgrounds (Packer, 2014; Sands et al., 2016). This issue is further exacerbated because the individuals and communities that are most directly affected by food system issues are sometimes the ones most absent in FPC membership (Sands et al., 2016; Boden and Hoover, 2018; Bassarab et al., 2019). As Packer (2014) highlighted, this lack of diversity and representation in FPC membership can create hotbeds for negative stereotypes, and deficit-based framing of low-income and food-insecure individuals. During the launch of the RIFPC, the First Lady of Rhode Island “publicly hailed the council's… ‘teaching people on SNAP how to eat healthy”' (p. 13). As Packer (2014) notes, such problematic proclamations betray widely held beliefs that people in receipt of SNAP1 benefits do not (know how to) eat “healthy” and require instruction from those more privileged, educated, or even enlightened” (p. 13) thus perpetuating negative stereotypes. Additionally, members of the RIFPC used deficit-based framing, through “negative, pitying terms: hunger, discrimination, inaccessibility, etc.” (Packer, 2014, p. 15). These examples point to a potential for implicit and explicit bias among members of FPCs, which may further alienate racialized or marginalized individuals from joining, thus perpetuating already existing barriers for membership diversity.

These issues with membership stand in contrast to the priorities and stated goals of many FPCs, which often include addressing inequity within food systems (Blay-Palmer, 2009; Packer, 2014; Siddiki et al., 2015; Sands et al., 2016; Boden and Hoover, 2018; Clark, 2018; Bassarab et al., 2019). Several articles indicated that some FPCs have recently included mandates or activities which focus on equity. Examples include the RIFPC which aims to achieve equitable food access regardless of income or race (Packer, 2014) and the Chicago Food Policy Advisory Council, which has joined a project which works toward “dismantling racism and empowering low-income and communities of color through sustainable and local agriculture” (Purifoy, 2014, p. 397). As Kessler (2019) writes, “without confronting the equity component, councils are prone to reinforce inequitable structures” (p. 49).

Overall, creating a diverse FPC has been described as a contributor to success (Clancy et al., 2008; Schiff, 2008; Dharmawan, 2015; De Marco et al., 2017) with benefits to internal and external networks; however, it appears to be a goal that many groups struggle to achieve. The existing membership structures serve to alienate others, limiting the council's ability to represent the community, and therefore decreasing its impact (Packer, 2014). McCullagh and Santo (2014) note,

Applied to FPCs, “meaningful inclusion” of diverse community residents is not simply an invitation to participate, but a practice that ensures that all participants feel comfortable and supported in making contributions and that their opinions are listened to and respected… (p. 28).

The absence of these important voices creates several challenges for FPCs, specifically the potential for a lack of ideological diversity, questions around equity and a limited understanding of the needs of those most vulnerable within the community (Sands et al., 2016; Boden and Hoover, 2018; Bassarab et al., 2019). The articles reviewed in our study suggest that in order to create meaningful change, many FPCs must change their governance structures and membership policies to enable greater diversity and work toward dismantling racism in the food system. The strategies to make such changes are not described in the literature and point to a potentially important area for further research.

Diversity within FPCs has been important for creating room for critical analysis, spurring innovation through diverse perspectives, and increasing social capital (; Walsh et al., 2015; Ilieva, 2016; McCartan and Palermo, 2017). Despite the evidence demonstrating the value of diversity, many of the articles reviewed indicated that FPCs often struggle to create a diverse membership. This has been particularly noted in terms of struggles to represent a broader range of race, class, and other socio-economic dimensions among members (Sands et al., 2016; Boden and Hoover, 2018; Bassarab et al., 2019).

Relationships With Government (and Bureaucracies)

Twenty of the articles we reviewed discussed the engagement of state actors in FPCs. Some of these articles discussed FPCs as being embedded within government offices or with direct links to government (Clancy et al., 2008; Mendes, 2008; Blay-Palmer, 2009; Coplen and Cuneo, 2015; Boden and Hoover, 2018; Bassarab et al., 2019). Some of the articles discussed directives or policies which mandated the inclusion of government representatives (Clayton et al., 2015; Siddiki et al., 2015; De Marco et al., 2017; Bassarab et al., 2019) while others noted the benefits of having paid staff funded directly through government (McCartan and Palermo, 2017).

From a different perspective, some articles discussed ways that FPCs were intentionally established outside of government or developed to ensure distance from government reach (Clancy et al., 2008; Packer, 2014; Boden and Hoover, 2018; Bassarab et al., 2019). Bringing these two extremes (government based or non–government) together, Schiff (2008) noted that a “hybrid” model includes “some formal relationship with government through funding, resources, or otherwise while maintaining some NGO or non-profit status. In their research, Gupta et al. (2018) echoed this noting that:

all but one of the 10 councils [studied] is organized as a multisector community collaborative, rather than as an independent non-profit organization or a government advisory body. Each includes local government personnel as members and most depend on government resources for their operations (p. 11).

Baldy and Kruse (2019) discussed two main ways that government actors were involved with FPCs, first as initiators of processes (e.g., introduce particular topics), and second as shapers of process (e.g., deciding who is involved, creating transparency within the process). Research findings from Bassarab et al. (2019) note that “membership and relationship to government have more bearing on the policy priorities (activities) of an FPC than the organizational structure” (p. 39).

Internal Governance

Seven articles discussed various internal governance arrangements such as formalized decision-making processes. Some of these articles discussed consensus decision-making processes implemented by FPCs to mitigate power imbalances (Packer, 2014; Clark, 2018). Other research indicated that FPCs developed processes and procedures to ensure greater democratic engagement such as Terms of Reference that were reviewed regularly, member surveys, committee structures, holding public meetings and sharing of meeting minutes (Sands et al., 2016; McCartan and Palermo, 2017; Boden and Hoover, 2018; Prové et al., 2019; Sieveking, 2019).

Challenges–Factors That Create Barriers to FPC Effectiveness

Most (19) articles described several different types of barriers that FPCs experience that impede their ability to achieve their goals (i.e., impede their effectiveness)2. We found four distinct categories of barriers described in the articles that we reviewed: membership and structural issues; resource issues; political issues; setting priorities.

Membership and Structural Issues

In terms of membership and structural issues, several (8) articles reported diversity and lack thereof, as a major barrier to effectiveness (as discussed above). These articles mainly focused on diversity issues from an equity or community representation perspective (Packer, 2014; Sands et al., 2016; Boden and Hoover, 2018). Some research pointed to difficulties of FPCs in engaging citizens (Sands et al., 2016; Boden and Hoover, 2018; Baldy and Kruse, 2019) and maintaining engagement in sub-committee work for volunteer members (Sieveking, 2019). Koski et al. (2018) identified engagement challenges when FPCs were too large–which could lead to marginalization of unique perspectives and disagreements on priorities 2018. Two articles pointed to lack of food system knowledge as a challenge for FPCs. This included lack of knowledge about the local food system of the FPC (Baldy and Kruse, 2019) as well as lack of knowledge about utilizing a food systems perspective (Sieveking, 2019). Another major challenge identified in the literature on FPCs is related to lack of leadership. This can be an issue when the FPC lacks leadership overall (Clancy et al., 2008; Scherb et al., 2012) or when there is a lack of leadership or champions for particular issues (Schiff and Brunger, 2013). On a related note, Scherb et al. (2012) and Sands et al. (2016) noted that some FPCs can also face challenges when members disagree about leadership, council structure or priorities.

Resource and Capacity Issues

The literature on barriers also noted that FPCs face several resource and capacity issues, some of which may be the most significant in terms of impeding the ability to achieve their specific goals. Resource/capacity barriers were noted in 11 articles. For example, funding is a major issue faced by many FPCs. As Bassarab et al. (2019, p. 36) described: “FPCs are woefully underfunded; 68% operate on an annual budget of $10,000 or less (35% have no funding). 12% have an annual budget over $100,000.” Several articles noted that some FPCs lack core funding–i.e. for staff, which is a significant barrier (Clancy et al., 2008; Schiff, 2008; Schiff and Brunger, 2013; Sands et al., 2016; Sieveking, 2019). Koski et al. (2018) described this specifically as a challenge for non-profit FPCs. Even for those FPCs that do have funding, the literature noted that there are often still monetary challenges. McCartan and Palermo (2017) identified issues related to lack of long-term funding–such as not being able to plan long term projects. Alternatively, some articles described FPCs that have core funding (even long-term core funding) but do not have funding for individual projects and face difficulty obtaining the funding needed to achieve their objectives (Schiff and Brunger, 2013; McCartan and Palermo, 2017; Prové et al., 2019).

Another resource issue described in the literature is lack of time. Research by Scherb et al. (2012) found that this is particularly the case when FPCs have been legislatively created or are dependent on a limited funding time frame. Mendes (2008) indicated that, as a result, FPCs can be forced to trade-off between quick wins and longer-term investment in policy change processes. An additional resource issue identified in the literature was related to training. While only one article touched on this issue (Scherb et al., 2012) with a focus specifically on lack of training in policy change processes, we note this may be an underlying challenge not yet identified among other FPCs.

Political Issues

The literature also identifies a range of political challenges faced by FPCs. There are two primary political issues: political turnover and formal association with government. Political turnover–due to political/electoral cycles–is an issue identified in several studies, often due to concerns about loss of support for the FPC as political leaders and the political climate (Clancy et al., 2008; Schiff, 2008; Blay-Palmer, 2009; Scherb et al., 2012; De Marco et al., 2017). Some studies expand on the associated issues which include a constant need to educate new political leaders, bureaucrats, other community leaders (Clancy et al., 2008; Schiff, 2008; Blay-Palmer, 2009). This is due to the lack of understanding among some new leaders about the interconnectedness of food issues and need for FPCs (Schiff, 2008; Blay-Palmer, 2009).

The second political issue identified in the literature is that formal associations with government can also create a range of challenges. While Schiff (2008) and others noted that FPCs can face difficulty accomplishing policy goals if they do not have strong relationship with government–there is other research which indicates challenges due to government affiliation. Coplen and Cuneo (2015) conducted an in-depth examination of dissolution of a government-based council and identified numerous issues related to its government affiliation. Other research has identified that having government employees on a council can be a barrier because they may not be allowed to do policy work (Scherb et al., 2012) or need to get approval for certain activities which slows down progress (Siddiki et al., 2015). As Siddiki et al. (2015, p. 544) described, “A lot of members, because of their a?liations, cannot engage in advocacy activity, which impacts what the council can actually do in garnering public support for policy recommendations.” Scherb et al. (2012) also identified that members might lack trust in governments which can lead to internal conflict or slow progress. Government councils can also be less connected and less responsive to community needs (Walsh et al., 2015). It is important to note that being situated within government or having government members can provide many benefits (these are discussed in the section on facilitators below).

Setting Priorities

A final area of challenges that we identified in the literature was related to defining priorities and conducting strategic planning. Scherb et al. (2012) indicated that there can be significant issues when FPCs have trouble defining or agreeing on priorities. As Koski et al. (2018) describe, this may be particularly challenging for FPCs with larger memberships. De Marco et al. (2017) identified that agreement on priorities can be difficult when diverse representatives may not understand other members' motivators and drawbacks to involvement on specific issues. Related to this is the challenge faced when members have different stances on particular issues. Scherb et al. (2012) also found that there may be different or even opposing perspectives on a policy or other issue that the FPC is attempting to address–this can lead to stagnation in agreeing on achieving objectives. Finally, Prové et al. (2019) identified an issue that, while not mentioned elsewhere, may be understudied and significant for other FPCs as well. They found that FPCs focusing at a specific scale (whether neighborhood, municipality, regional or state) may miss opportunities, fail to address important issues, or encounter challenges that could have been avoided if the focus was at a different scale, or even multiple scales.

Facilitators–Factors That Support FPC Effectiveness

In addition to barriers, almost all (23) of the articles discussed factors or approaches that may support FPC effectiveness. These factors included include distinct approaches to: organizational structure; membership; and strategic planning. There is also some literature on how to successfully form a FPC, which we include here as well.

FPC Establishment

Two of the articles we reviewed spoke directly about how to effectively form an FPC. While there is not an extensive literature on this topic, it is nonetheless important, since many FPCs in their formative stages look for such direction and guidance. De Marco and colleagues (2017) noted four factors which support successful formation of a FPC. Those included: (1) stakeholder involvement; (2) diverse partnerships; (3) stake-holder ability to compromise; and (4) conducive political setting (De Marco et al., 2017). Schiff and Brunger (2013) also discussed the formation of an FPC and noted that widespread education and awareness raising about food issues in a community (such as through the creation of a community food plan) can help to build support for and interest in the FPC concept among politicians and community members.

Structural

The literature discusses a number of approaches to structuring an FPC that can be important for supporting on-going effectiveness–this was a theme in seven of the articles reviewed. Several of these studies identified the importance of processes that would support open communications and transparency in decision making processes (Coplen and Cuneo, 2015; Baldy and Kruse, 2019; Sieveking, 2019). Other studies identified the importance of having staff (Clancy et al., 2008; Schiff, 2008) as well as a strong, long-term commitment and engagement from staff and members (Clancy et al., 2008; Blay-Palmer, 2009; McClintock et al., 2012). Finally, Coplen and Cuneo (2015) indicated that strategic planning and evaluation could be very important for FPCs to ensure that structures and processes can be responsive to changing needs.

Membership

Membership can be an impediment (as discussed above) but is also identified in many (13) articles as a core strength of FPCs. Several (10) studies discussed the ways in which membership can be mobilized for greatest effectiveness. In this literature, diversity in representation and community engagement were widely cited as key factors for FPC effectiveness (Clancy et al., 2008; Mendes, 2008; Schiff, 2008; McClintock et al., 2012; Coplen and Cuneo, 2015; Sands et al., 2016; Gupta et al., 2018). Purifoy (2014) found that having local residents as members can help maintain legitimacy and support with municipalities and organizations. Additionally, research by McCartan and Palermo (2017) revealed that having members from a diverse range of sectors helps to extend the reach, influence, and resources of the FPC networks. Similarly, other research found that FPCs may see more success when they consciously focus on internal and external partnerships and seek out key partners/members in private and public sectors (Mendes, 2008; Clayton et al., 2015; Walsh et al., 2015; Sands et al., 2016).

Strong leadership within the membership was another strongly cited factor for success–appearing in 11 of the articles. This included the importance of including and engaging local “experts” or “champions” and links to government (Clancy et al., 2008; Schiff, 2008; Gupta et al., 2018). Researchers reported that these types of partnerships and links can help gain legitimacy, political capital, and maintain links with people in government with decision and policy-making capacity and power (Packer, 2014; Clayton et al., 2015; Walsh et al., 2015; Boden and Hoover, 2018; Bassarab et al., 2019) and with the private sector (Schiff and Brunger, 2013; Clayton et al., 2015). Baldy and Kruse (2019) argue that state actors are pivotal for affecting change through participation processes that aim to implement food policy measures. However as noted in the section on challenges, links with government can also come with pitfalls. For this reason, Gupta et al. (2018) recommend FPCs maintaining some degree of autonomy in priority setting and decision-making capacities (Gupta et al., 2018). They suggest that FPCs might be more effective if housed outside of government:

Councils housed outside of the government…can engage in strategic temporary alliances or partnerships with specific agencies that align with their particular campaign goals at the time without needing to comply with or adhere to the mission of any particular government agency over the long-term. Positive working relationships with government entities, therefore, do not necessarily need to be formalized and/or institutionalized to lead to successful policy outcomes or to build trust and legitimacy (p. 23).

Strategic Planning

The literature also includes some discussion of the ways in which FPCs can approach their activities and plan their work, that might lead to the greatest effectiveness in achieving goals. Some studies identified that background research and planning, while lengthening the process, may be critical to being successful for specific projects and goals (McClintock et al., 2012; Coplen and Cuneo, 2015). Other studies discuss the importance of collaboration, and of engaging members in planning and implementing projects (Schiff, 2008; McCartan and Palermo, 2017). It should be noted however that other articles and earlier FPC research has found that putting pressure on members to be involved in project implementation can also be a drawback (Schiff, 2007; Sieveking, 2019). This occurs when members might have limited time or capacity to take on that work. Several studies identified the importance of both internal (within the FPC) and external education and awareness raising about projects (Clancy et al., 2008; Schiff, 2008; Schiff and Brunger, 2013; Walsh et al., 2015; Baldy and Kruse, 2019; Sieveking, 2019). Internal learning can help to build excitement and buy-in around projects while external education can build more widespread community support and bring additional resources to projects. Some research also suggests the importance of focusing on community needs (Walsh et al., 2015), having priorities that are flexible according to opportunities, financial or otherwise (Schiff and Brunger, 2013), and looking for “quick wins” that can help to build confidence in the FPC. Finally, Schiff and Brunger (2013) note that celebrating success is important for building and maintaining morale and support for the FPC.

Gaps and Future Research Directions

Our review of the literature on FPCs also considered the directions for future research suggested in this literature. Four themes emerged from this analysis: (1) Methodological gaps; (2) Evaluation needs; (3) Impact of FPC activities; (4) FPCs' role in democratic decision making.

Methodological Gaps

A significant set of gaps that we identified was related to the methods employed in the studies of FPCs. Almost all the studies of FPCs (21 articles) used a case study approach, with primarily qualitative (interviews, focus groups, document review) methods. There were only two studies (Scherb et al., 2012; Bassarab et al., 2019) that used quantitative methods. Those studies surveyed FPCs at a national level and used descriptive statistics to analyze data related to policy activities, policy priorities, and the influence of organizational structure and membership on policy work.

While qualitative and case study approaches yield important and in-depth information, we suggest that there is a need for more diverse methods and greater application of quantitative, multi-site, and mixed methods in the study of FPCs. There is a particular lack of the application of quantitative methods to add to the evaluation and in-depth understanding of single FPCs at a local level. Since much FPC research has focused on case study approaches, there may be a need for a more standardized and generic framework through which to describe the characteristics and activities of individual FPCs. Such approaches might add significantly to answering some of the outstanding questions related to FPCs as described below such as those related to strategic evaluation and impact of FPC activities. Multisite comparative, longitudinal, and quantitative approaches would be well suited to linking different aspects of organizational functioning with success/failure of FPCs. Social network analysis might also be a valuable methodological tool to consider for investigations related to FPCs membership, partnerships, and related impacts (Levkoe et al., 2021).

Another important consideration in future evaluation of FPC literature may be a consideration of the theoretical orientations employed by researchers in the formulation of research questions and methodologies. Future examination of the FPC literature might investigate theoretical frameworks through which FPCs are examined. It may also be important for further empirical studies on FPCs to examine these frameworks and discuss explicit orientation of their research within existing theory on FPCs.

There are also significant geographic gaps in the study of FPCs, with most research focused on FPCs in the U.S. There is little research on FPCs in other countries such as Canada, Australia, the U.K. other European countries, and in the Global South. Some of the articles that we reviewed noted this gap and suggested a need for more examination of FPCs in other countries (Baldy and Kruse, 2019). We also suggest a need for more research that can implement a geographical approach to understanding FPCs. This could include research which examines the experiences of FPCs within and between countries in different types of geographies and geo-political contexts, for example, rural vs. urban, local vs. regional levels, and across different national contexts.

Strategic Evaluation

An additional and related methodological gap is the lack of strategic formative and program evaluations conducted on/with FPCs. When the FPC movement was in its infancy, such evaluations were seen as a potential threat to their ongoing growth and the establishment of new FPCs (Schiff, 2007). Now that many FPCs are well established and widespread, we suggest that researchers and FPCs should consider regular, formal program evaluations (of FPC structure and activities) to support continuous improvement. This may help to further future research directions identified in several of the articles that we reviewed. Many authors called for systematic evaluations of FPCs' influence on policy, other impacts on local food systems, and the relationship between these efforts and the organizational dimensions. There were also articles that called for changes to governance structures to allow for greater equity and diversity in FPC membership, though there were not suggestions on how to achieve this. We suggest that more research may be needed on governance structures that are successful in supporting diverse councils and addressing / dismantling racism in the food system. Implementing regular evaluations might also prevent many of the issues (even dissolution) of FPCs that were described in the literature by providing FPCs with information on what is working, and what could be changed to improve their functioning. Such evaluations should look to program evaluation methodology (Newcomer et al., 2015) and incorporate both quantitative and qualitative approaches to assessing challenges, successes, and opportunities. Such work may in fact add further legitimacy and demonstrate the importance of FPCs in supporting the move toward healthy, sustainable and equitable food systems.

Impact of FPC Activities

Many articles suggested a need more research on and documentation of the impact of FPC activities (e.g., are FPCs achieving goals for food systems change?). This could apply broadly to any activities that FPCs are engaged with–as McCartan and Palermo (2017) suggest, there is a need to understand the extent to which FPCs influence local food systems. This will contribute to a greater understanding of work being undertaken within local food systems, which may lead to a greater proliferation of FPCs and create meaningful change within the broader food system.

Several articles focused specifically on policy work. There were several suggestions for further analysis of FPCs' success in influencing policy and policy-making processes. This was accompanied by an interest in understanding whether FPC policy activities result in food systems change, as Bassarab et al. (2019) described:

Since our analysis did not explore FPC policy out-comes, we are left with further questions around the goal of food democracy—that is, if and how FPC policy outcomes yield transformative food systems change” (p. 40).

FPCs and Democratic Processes

Several articles paid particular attention to FPCs as a form of democratic institution—representing a new avenue for democratic decision—making about food issues. This was discussed in the context of the FPCs inclusion of state and non–state actors in decision–and policy–making processes (Baldy and Kruse, 2019). It was also discussed in terms of FPCs engagement with deliberative processes–with a few authors suggesting direct links to theories of deliberative democracy and the emergent theory of food democracy (Sieveking, 2019). These authors suggested a need for further definition of the concept of “food democracy” as well as clearer links between this theory and the concept of deliberative democracy (e.g., a demonstration of the ways in which FPCs embody and contribute to deliberative democratic processes).

These calls for more research documenting FPCs' connections to food democracy and deliberative democracy also led to suggestions for further investigation on the importance of citizen engagement in FPC activities. FPCs were described in many instances as a tool for empowering citizens and increasing citizen engagement—however, many authors pointed to a need for more research on the importance and impact of citizen involvement (Baldy and Kruse, 2019; Bassarab et al., 2019; Sieveking, 2019).

These suggestions also tied into the need for further investigation into diversity in council membership. Boden and Hoover (2018) offer the suggestion that further attention is needed to diversity in council membership—particularly in order to address race, class, and other equity issues related to food systems and food democracy. Our analysis also found that there was little connection to a broader literature (and social movements) on racism and dismantling racism, White privilege, and privilege of the Global North in food systems (Schiff and Levkoe, 2014; Holt-Giménez, 2015). We suggest that analyzing FPCs against the backdrop of these movements may provide additional insights into the activities, successes, and challenges of FPCs.

Conclusions

In the past two decades, the number of FPCs has grown dramatically. Alongside this growth, there has been increasing academic interest in FPCs–what they do, how they do it, and what challenges and successes they encounter in their work. Given the rapid growth in FPC numbers and academic interest, our scoping review aimed to systematically analyze this growing body of literature to identify future directions for research. As such it sought to address the questions: What are the major themes in research on FPCs in the past two decades (i.e., published between 1999 and 2019)? What methods have been employed in the study of FPCs in the past two decades? What gaps and directions for further research are suggested by the research on FPCs?

We identified four main themes (and several sub–themes) in the FPC research in the past two decades: (1) Activities of FPCs; (2) Organizational dimensions; (3) Challenges; and, (4) Facilitators. We also noted a significant sub-theme related to equity and diversity, race and class representation in FPCs. These themes frame a growing body of knowledge on FPCs which may aid these organizations, those interested in approaches to food systems change, and those interested in cross-sectoral collaborative approaches to food systems and sustainability governance. We also identified four key gaps described in the current body of literature which might provide direction for future research on FPCs. These include needs to: broaden methodological approaches, support strategic evaluation, evaluate the impact of FPC activities and document links to deliberative and food democracy. This evaluation may provide direction for ongoing impact in FPC research and evaluation.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

We would like to acknowledge funding contributions from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada by way of a Partnership Grant #895 - 2015 - 1016 FLEdGE - Food: Locally Embedded, Globally Engaged.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^SNAP is the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program – a federal program of the United States government which assists low – income families with the cost of purchasing healthy foods.

2. ^For the purposes of this article, we define “effectiveness” as FPCs' ability to achieve their goals and objectives. This may be characterized in terms of program or policy goals or in terms of organizational goals such as achieving organizational stability.

References

Arksey, H., and O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 8, 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

*Baldy, J., and Kruse, S. (2019). Food democracy from the top down? State-driven participation processes for local food system transformations towards sustainability. Politics Gov. 7, 68–80. doi: 10.17645/pag.v7i4.2089

*Bassarab, C. J. K., Santo, R., and Palmer, A. (2019). Finding our way to food democracy: lessons from us food policy council governance. Politics Gov. 7, 32–47. doi: 10.17645/pag.v7i4.2092

*Blay-Palmer, A. (2009). The Canadian pioneer: the genesis of urban food policy in toronto. Int. Plan. Stud. 14, 401–416. doi: 10.1080/13563471003642837

*Boden, S., and Hoover, B. M. (2018). Food policy councils in the mid-atlantic: working toward justice. JAFSCD. 8, 39–52. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2018.081.002

Centre for a Livable Future (n.d.). Food Policy Council Directory. Available online at: https://www.foodpolicynetworks.org/councils/directory/online/index.html (accessed November 15, 2021).

*Clancy, K., Hammer, J., and Lippoldt, D. (2008). “Food policy councils-past, present, and future,” in Remaking the North American Food System: Strategies for Sustainability, Hinrichs, C., and Lyson, T. A. (eds). University of Nebraska Press. p. 121–143.

Clancy, K. Eight Elements Critical to the Success of Food System Councils. (1988). Available online at: http://homepages.wmich.edu/~dahlberg/Resource-Guide.html (accessed January 27, 2007).

*Clark, J. (2018). From civic group to advocacy coalition: using a food policy audit as a tool for change. JAFSCD. 8, 21–38. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2018.081.004

*Clayton, M. L., Frattaroli, S., Palmer, A., and Pollack, K. M. (2015). The role of partnerships in U.S. food policy council policy activities. PloS ONE. 10, 4. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122870

*Coplen, A. K., and Cuneo, M. (2015). Dissolved: lessons learned from the portland multnomah food policy council. JAFSCD. 5, 91–107. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2015.052.002

Dahlberg, K. A. (1994a). “Food policy councils: The experience of five cities and one county”, in Paper presented at the Joint Meeting of the Agriculture, Food, and Human Values Society, and the Association for the Study of Food and Society. Tucson, AZ.

Dahlberg, K. A. (1994b). A transition from agriculture to regenerative food systems. Futures. 26, 170–179. doi: 10.1016/0016-3287(94)90106-6

*De Marco, M., Chapman, L., McGee, C., Calancie, L., Burnham, L., and Ammerman, A. (2017). Merging opposing viewpoints: analysis of the development of a statewide sustainable local food advisory council in a traditional agricultural state. JAFSCD. 7, 197–210. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2017.073.018

Dharmawan, A. (2015). Investigating Food Policy Council Network Characteristics in Missouri: A Social Network Analysis Study. (Dissertation). St. Louis (MO): Saint Louis University.

Gottlieb, R., and Fisher, A. (1995). Community Food Security: Policies for a More Sustainable Food System in the Context of the 1995 Farm Bill and Beyond. Los Angeles, CA: The Ralph and Goldy Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies. Available online at: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9nm3c0gk (accessed January 25, 2021).

*Gupta, C., Campbell, D., Munden-Dixon, K., Sowerwine, J., Capps, S., Feenstra, G., et al. (2018). Food policy councils and local governments: creating effective collaboration for food systems change. JAFSCD. 8, 11–28. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2018.08B.006

Hawe, P., and Stickney, E. (1997). Developing the effectiveness of an intersectoral food policy coalition through formative evaluation. Health Educ. Res. 12, 213–225. doi: 10.1093/her/12.2.213

Holt-Giménez, E. (2015). Racism and capitalism: dual challenges for the food movement. JAFSCD. 5, 23–25. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2015.052.014

Ilieva, R. (2016). “New governance arenas for food policy and planning,” in Urban Food Planning, ed R. Ilieva (Philadelphia, PA: Routledge), 197–221.

Kessler, M. E. (2019). Achieving Equity (with) in Food Policy Councils: Confronting Structural Racism and Centering Community (Master's thesis). Ås (Norway): Norwegian University of Life Sciences.

*Koski, C., Siddiki, S., Sadiq, A. A., and Carboni, J. (2018). Representation in collaborative governance: a case study of a food policy council. Am. Rev. Public Administrat. 48, 359–373. doi: 10.1177/0275074016678683

*Lang, R., Rayner, G., Rayner, M., Barling, D, and Millstone, E. (2005). Policy councils on food, nutrition and physical activity: the UK as a case study. Public Health Nutrit. 8, 11–19. doi: 10.1079/PHN2004654

Levkoe, C. Z., Schiff, R., Arnold, K., Wilkinson, A., and Kerk, K. (2021). Mapping food policy groups: understanding cross-sectoral network building through social network analysis. Can. Food Stud. 8:2, 48–79. doi: 10.15353/cfs-rcea.v8i2.443

*McCartan, J., and Palermo, C. (2017). The role of a food policy coalition in influencing a local food environment: an Australian case study. Public Health Nutr. 20, 917–926. doi: 10.1017/S1368980016003001

*McClintock, N., Wooten, H., and Brown, A. H. (2012). Toward a food policy “first step” in Oakland, California: a food policy council's efforts to promote urban agriculture zoning. JAFSCD. 2, 15–42. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2012.024.009

McCullagh, M., and Santo, R. (2014). Food Policy for all: Inclusion of Diverse Community on Food Policy Councils. Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future. Available online at: https://assets.jhsph.edu/clf/mod_clfResource/doc/Food%20Policy%20For%20All%204-81.pdf (accessed February 12, 2021).

*Mendes, W. (2008). Implementing social and environmental policies in cities: the case of food policy in Vancouver, Canada. IJURR. 32, 942–967. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2008.00814.x

Newcomer, K. E., Hatry, H. P., and Wholey, J. S. (2015). Handbook of practical program evaluation. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi: 10.1002/9781119171386

*Packer, M. M. (2014). Civil subversion: making “quiet revolution” with the Rhode Island food policy council. J. Criti. Thought Praxis. 3, 1. doi: 10.31274/jctp-180810-28

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372, 71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

*Prové, C., de Krom, M. P. M., and Dessein, J. (2019). Politics of scale in urban agriculture governance: a transatlantic comparison of food policy councils. J. Rural Stud. 68, 171–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.01.018

*Purifoy, D. M. (2014). Food policy councils: Integrating food justice and environmental justice. Duke Environ. Law Policy Forum. 24, 375–398.

Riches, G. (2018). Food Bank Nations: Poverty, Corporate Charity and the Right to Food. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315184012

*Sands, C., Stewart, C., Bankert, S., Hillman, A., and Fries, L. (2016). Building an airplane while flying it: one community's experience with community food transformation. JAFSCD. 7, 89–111. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2016.071.012

Santo, R., Bassarab, K., and Palmer, A. (2017). State of the Research: An Annotated Bibliography on Existing, Emerging, and Needed Research on Food Policy Groups (1st edition). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future. Available online at: https://assets.jhsph.edu/clf/mod_clfResource/doc/Main-FPN%20Annotated%20Bibliography-2020_final.pdf [Accessed November 15, 2020].

*Scherb, A., Palmer, A., Frattaroli, S., and Pollack, K. (2012). Exploring food system policy: a survey of food policy councils in the United States. JAFSCD. 2, 3–14. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2012.024.007

Schiff, R. (2007). Food Policy Councils: An Examination of Organisational Structure, Process, and Contribution to Alternative Food Movements. [Dissertation]. [Perth (Australia)]: Murdoch University

*Schiff, R. (2008). The role of food policy councils in developing sustainable food systems. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 3, 206–228. doi: 10.1080/19320240802244017

*Schiff, R., and Brunger, F. (2013). Northern food networks: building collaborative efforts for food security in remote canadian aboriginal communities. JAFSCD. 3, 31–45. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2013.033.012

Schiff, R., and Levkoe, C. Z. (2014). “From disparate action to collective mobilization: collective action frames and the Canadian food movement,” in Occupy the Earth: Global Environmental Movements, eds L. Leonard, and S. B. Kedzidor (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 225–253.

*Siddiki, S. N., Carboni, J. L., Koski, C., and Sadiq, A. A. (2015). How policy rules shape the structure and performance of collaborative governance arrangements. Public Admin. Rev. 76, 536–547. doi: 10.1111/puar.12352

*Sieveking, A. (2019). Food policy councils as loci for practising food democracy? Insights from the case of Oldenburg, Germany. Politics Gov. 7, 4. doi: 10.17645/pag.v7i4.2081

*Walsh, C. C., Taggart, M., Freedman, D. A., Trapl, E. S., and Borawski, E. A. (2015). The Cleveland-Cuyahoga county food policy coalition: “we have evolved.” Prev. Chronic Dis. 12. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.140538

Webb, P. D., Maretzki, A., and Wilkins, J. (1998). Local food policy coalitions: evaluation issues as seen by academics, project organizers, and funders. Agri. Human Values.15, 65–75. doi: 10.1023/A:1007408901642

Yeatman, H. (1994). Food Policy Councils in North America - Observations and Insights. Available online at: https://documents.uow.edu.au/content/groups/public/@web/@health/documents/doc/uow025389.pdf (accessed January 28, 2022).

Keywords: food policy councils, food policy, food systems, food movements, local food systems

Citation: Schiff R, Levkoe CZ and Wilkinson A (2022) Food Policy Councils: A 20—Year Scoping Review (1999–2019). Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 6:868995. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2022.868995

Received: 03 February 2022; Accepted: 04 April 2022;

Published: 20 May 2022.

Edited by:

Steffanie Scott, University of Waterloo, CanadaReviewed by:

Patrick Baur, University of Rhode Island, United StatesPhillip Warsaw, Michigan State University, United States

Copyright © 2022 Schiff, Levkoe and Wilkinson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rebecca Schiff, cnNjaGlmZkBsYWtlaGVhZHUuY2E=

Rebecca Schiff

Rebecca Schiff Charles Z. Levkoe

Charles Z. Levkoe Ashley Wilkinson

Ashley Wilkinson