94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Food Syst., 04 April 2022

Sec. Nutrition and Sustainable Diets

Volume 6 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.858048

This article is part of the Research TopicExploring Consumers' Willingness To Adopt Climate-Friendly DietsView all 14 articles

The meat consumption at the current level is highly unsustainable. Because of the problems that meat production causes to the environment, it is considered as one of the main problems. Vegetarian and vegan private label products represent a new challenging trend in addressing the customers within sustainable food consumption at affordable prices. The submitted paper aimed to find out whether Slovak consumers know and subsequently buy products of the private brand targeted on vegans and vegetarians, in which product categories they do so, how they perceive them and what attracts and discourages them. The research was carried out in the period from September to December 2020, when a total of 2,011 respondents from all over Slovakia took part. As we have focused only on consumers who know the product line of private labels targeted on vegans and vegetarians (product line of vegan and vegetarian products), we have further analyzed and interpreted only the answers of 978 respondents. For the need to obtain the main aim of the research, we have formulated four theoretical assumptions and five hypotheses, whose veracity was verified with the use of selected statistical methods and techniques processed out at statistical programs XL Stat, SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1. and SAS 9.4. The key finding of our research is, that even if it could be assumed that the products of this specific private label will be bought only by respondents from the vegan or vegetarian category, the opposite is true—the private label is known and bought by the respondents from the category “I eat everything,” which means that it is necessary to think about this product line, to wider it and continue in the improvement of its quality as this is what the customers want.

The meat industry is facing some major sustainability problems. Animal livestock uses a disproportionally large amount of land and the meat industry is also a major source of environmental damage, with the UN describing animal agriculture as “one of the most significant contributors to the most serious environmental problems, at every scale from local to global.” Whilst many of the problems associated with animal agriculture could be solved by large percentages of the world's population giving up meat, this seems extremely unlikely, regardless of environmental or ethical reasons. As such, there is a large opportunity for any company that can create a realistic substitute for meat products (Dent, 2020).

How does the market reflect on this challenging trend in sustainable food consumption? Could be also taken into consideration a requirement of many customers for the affordable price of vegan and vegetarian products? The answer comes with the private label vegetarian and vegan product lines.

Marques et al. (2020) stated that private labels have had several different definitions over the years, however, they are commonly known as super and hypermarkets' brands and products, sold exclusively on their stores, alongside other brands (Sutton-Brady et al., 2017).

As Gil-Cordero et al. (2020) state, in general terms, private labels are brands that can be manufactured by the distributor or a manufacturer, managed and marketed by the distributor under the name of the ensign or its brand, and that can be distributed in the ensign's establishments or those of other chains (Lybeck et al., 2006). Private labels represent a significant threat to their national label competitors (Hoch and Banerji, 1993; Anesbury et al., 2020; Bronnenberg et al., 2020; Marques et al., 2020; Pinar and Tulay, 2020). With the development of private labels, individual retailers now play an active role in producing final products. These products, which represent between 10 and 40% of food retail sales in the different countries of the European Union, are a strategic tool used by retailers to increase profits (Gil-Cordero and Cabrera-Sánchez, 2020; Gil-Cordero et al., 2020). It is not surprising that private labels provide additional market power to retailers (Bontemps et al., 2008).

As it was pointed out in several studies (Chan and Coughlan, 2006; Košičiarová and Nagyová, 2014; Lim et al., 2019; Kádeková et al., 2020a; Košičiarová et al., 2020a,b,etc.), one of the characteristic features and at the same time key strategies of retail chains and companies is to address as many customers as possible and, if it is possible, all customer groups, i.e., focus not only on price-sensitive customers but also those who seek for the quality. These realities have to be satisfied by the products or services we have researched, which are collectively referred to as private labels, whose share in Europe, especially in Slovakia, is constantly growing.

The growing market share of private brands began many years before the global economic recession of 2008 (Cuneo et al., 2012). In these receptions, some authors investigated how different macroeconomic variables affected private brand share (Samit and Cazacu, 2016; Gil-Cordero et al., 2020). In this sense and the different receptions, the growth of private labels in Europe and the USA in recent years has been extraordinary, since in the last decade they have become present in more than 90% of the categories of products packaged for the final consumer (Kumar, 2007).

Private labels become not just a source of competitive advantage, but especially a means of building customer loyalty and thus the overall corporate image, which cannot be (by the quality of private labels) only significantly improved but also worsen (Kádeková et al., 2020a). It can be stated that while in Austria the share of private labels (in household expenditure) still represents a level above 40%, in the case of the V4 countries this level is above 30% and it has mostly increased in the case of the Czech Republic, by 1%. Interestingly, while in France private labels represent 1/3 of the sold products, in Switzerland and Spain it is up to ½ products (PLMA, 2020).

However, in according to the results of research by Gfk in 2021, private labels are gaining increasing share in expenses for fast-moving goods. They currently represent a quarter of the market value (25.5%; Mediaguru, 2021).

As Li et al. (2021) explained, that some studies have also focused on the private-brand quality-positioning problem (Chung and Lee, 2017; Nalca et al., 2018). Wang et al. (2021) suggested that the retailer should lower the quality of the store brand to reduce competition intensity with the manufacturer.

It can be said that most chains continue to develop and evolve their brands in response to changing market conditions, the development of science and technology, as well as the customers' needs (Kádeková et al., 2020a,b).

In the case of 2018 and 2020, further positive activities in the area can be observed, as several retail chains (especially Kaufland and Lidl) have introduced new private label product lines focused not only on domestic products and their producers, but also on the development and expansion of the range of foods aimed at people with food intolerances and specific needs when they introduced new categories of private labels such as “K-take it veggie,” “K-bio,” “K-free,” or “Vegan friendly,” “Free from”etc.

Although the popularity of vegetarian diets has varied over the centuries, the prevalence of vegetarianism is currently high (Amato and Partridge, 2008; Timko et al., 2012), which can also contribute to sustainable consumption, agriculture, and the economy. The research studies by Segovia-Siapco and Sabaté (2019) and Sanchez-Sabate et al. (2019) mention that in countries like the United States or the UK, vegetarians account for <5% of their respective populations. According to a News Gallup (2020), 5% of U.S. adults consider themselves to be vegetarian and the US vegan population is 3% of adults (News Gallup, 2020). Recognizing the difference between what people eat and what they think they are can explain the inconsistency between the lack of an increase in the number of people who identify as vegetarians and reports of reductions in the consumption of meat (Šimčikas, 2018).

The current position is that the number of people who maintain a vegetarian or vegan diet 100% of the time holds at 3% of the population and still increases. Interest in veganism has reached an all-time high in 2020, based on the data from Google Trends (Google Trends, 2020). It reflects the notable rise in popularity of plant-based diets and vegan lifestyles around the world (Ho, 2021).

“Vegetarianism” refers to a spectrum of inter-related food selection and food avoidance patterns (Beardsworth and Keil, 1993). Technically, ovo-vegetarians include eggs but no dairy products in their diet, Lacto-vegetarians include dairy products but exclude eggs, and Lacto-ovo vegetarians include both eggs and dairy products in their diet (Messina and Burke, 1997; Trautman et al., 2008). Semi-vegetarians restrict the type of meat they consume only to a certain extent, with some consuming only fish (Pesco-vegetarian), some only poultry (Pollo-vegetarian), and some consuming both fish and poultry (Pesco Pollo vegetarians). Finally, individuals who adhere to a vegan diet exclude all red meat, fish, poultry, dairy, and other animal-origin foods such as eggs from their diets, and generally also avoid non-edible animal products such as leather (Vegan Official Labels, 2020).

Šedík et al. (2017) have pointed out, that hypermarket Kaufland responded to changing trend in food consumption by creating its private label brand “K-take it veggie.” All these products are offered to consumers with conscious consumption (Kaufland.sk, 2021).

In a new retail landscape, retailers have realized that the most important engine to drive both growth and profitability is strategically building private labels (Gangwani et al., 2020).

The submitted contribution is focused on the issue of specific categories of private labels, specifically private labels designed primarily for vegans and vegetarians, where we try to prove and find out whether these products have their place in the private label market, whether they have found their customer and whether this customer is just a vegan/vegetarian.

The submitted contribution intended to point out the fact that Slovak consumers are starting to focus on new categories of private labels, specifically on vegan/vegetarian products, which are still just looking for their regular consumers. For this reason, the main aim of our research was to find out whether Slovak consumers know and subsequently buy products of the private brand targeted on vegans and vegetarians, in which product categories they do so, how they perceive them and what attracts and discourages them.

The research was carried out in the period from September to December 2020, when a total of 2,011 respondents took part in it (based on the mentioned, our sample can be considered reliable, as n ≥ 1,849 at a 99% confidence level and 3% margin of tolerable mistakes).

As we have focused (in the research) only on consumers who know the product line of private labels targeted on vegans and vegetarians (product line of vegan and vegetarian products), we have further analyzed and interpreted only the answers of these respondents and thus their final number was 978 (the sample is reliable at 99% confidence and 5% margin of tolerable mistakes, as n ≥ 665.64). The specific representation of respondents can be seen in Table 1.

For the needs of fulfilling the main aim of the research, we have formulated the following theoretical assumptions, which we wanted to confirm, or refute by the research:

• Assumption 1—we assume that the private label targeted on vegans and vegetarians is bought only by vegans, resp. vegetarians,

• Assumption 2—the most frequently purchased food under the private label targeted on vegans and vegetarians is tofu,

• Assumption 3—the quality of products labeled with private brands targeted at vegans and vegetarians is comparable to the quality of similar products of traditional brands,

• Assumption 4—respondents from the selected aspects of products under the private label targeted on vegans and vegetarians evaluate as the best their quality level.

Subsequently, we have formulated the following statistical hypotheses:

• H1 there is no dependence between the consent to the statement and the form of the respondent's diet,

• H2 there is no dependence between the purchase of the private label targeted on vegans and vegetarians and the form of the respondent's diet,

• H3 there is no dependence between the consumption of specific products of the private label targeted on vegans and vegetarians and the respondent's sex,

• H4 there is no dependence between the perception of the quality of products labeled with the private label targeted on vegans and vegetarians and the preference for their purchase,

• H5 there is no dependence between the preference of products labeled with the private label targeted on vegans and vegetarians and the comparability of the quality of its products,

whose veracity was verified with the help of selected statistical methods and techniques. We have tested the above-mentioned hypotheses with the help of statistical programs XL Stat, SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1. and SAS 9.4, where we have used the statistical methods, techniques and tests such as:

• Pearson's Chi-square goodness of fit test—which is a statistical test applied to sets of categorical data to evaluate how likely it is that any observed difference between the sets arose by chance (Pearson, 1900),

• Cramer's contingency coefficient—which is a measure of association between two nominal variables, giving a value between 0 and +1 (inclusive). It is based on Pearson's chi-squared statistic and was published by Cramer (1946),

• Pearson's correlation coefficient—is a measure of linear correlation between two sets of data. It is the ratio between the covariance of two variables and the product of their standard deviations; thus it is essentially a normalized measurement of the covariance, such that the result always has a value between −1 and 1 (University Libraries, 2022),

• Phi coefficient—is a measure of association for two binary variables. In machine learning, it is known as the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) and it is used as a measure of the quality of binary classifications (Matthews, 1975). Introduced by Karl Pearson (Cramér, 1976) and also known as the Yule phi coefficient from its introduction by Yule (1912) this measure is similar to the Pearson correlation coefficient in its interpretation—Pearson correlation coefficient estimated for two binary variables will return the phi coefficient (Guilford, 1936). The phi coefficient is related to the chi-squared statistic for a 2 ×2 contingency table,

• Friedman's test—is a non-parametric statistical test developed by Friedman (1937) and it is used to detect differences in treatments across multiple test attempts. The procedure involves ranking each row (or block) together, then considering the values of ranks by columns (Friedman, 1940),

• Kruskal-Wallis—is a non-parametric method for testing whether samples originate from the same distribution. It is used for comparing two or more independent samples of equal or different sample sizes. It extends the Mann–Whitney U-test, which is used for comparing only two groups (Kruskal, 1952),

• the Correspondence analysis—is a multivariate statistical technique, which offers a visual understanding of relationships between qualitative (i.e., categorical) variables. Correspondence analysis is a method for visualizing the rows and columns of a table of non-negative data as points in a map, with a specific spatial interpretation. Data are usually counts in a cross-tabulation, although the method has been extended to many other types of data using appropriate data transformations (Greenacre, 2001), and

• Categorical principal component analysis (CATPCA) with Varimax rotation and Kaiser normalization—which is appropriate for data reduction when variables are categorical (e.g., ordinal) and the researcher is concerned with identifying the underlying components of a set of variables (or items) while maximizing the amount of variance accounted for in those items (by the principal components; Data Science and Analytics, 2022). This method has shown a great potential when applying for validation of questionnaire especially for Likert scale or different measures due to optimal scaling. Furthermore, it explains higher variance in comparison to FA or PCA (Campos et al., 2020). CATPCA was applied for ordinal data obtained from respondents who evaluated selected aspects regarding vegetarian and vegan private label products (5-points scale was applied).

Based on results of research by Dodds et al. (1991), Sweeney and Soutar (2001), Flavián et al. (2006), Vahie and Paswan (2006), Liljander et al. (2009), Beneke et al. (2013), Diallo (2012), Diallo et al. (2013), Beneke and Carter (2015), and Gfk (2021) and many others can be concluded the private labels have found their important place worldwide. Also in Slovakia, the Slovak consumers recognize and purchase private label products more often, which was proved by the research agencies such as IRI, Nielsen, Gfk Slovakia, TNS Slovakia, etc. This fact was supported also by findings and results of our research, which we have been conducting since 2014 when we recorded the major shifts in the perception and evaluation of private labels by Slovak consumers.

As for the specific interest of Slovaks in the private labels, it can be said that as in the case of retail chains and customers, their interest in them is constantly growing—this is confirmed not only by the representatives of the most important retail chains operating in Slovakia but also by the results of research by Nielsen (2019) that found out that revenues from private labels exceeded 4 billion EURO in 2018, which means that they have increased by 0.5% year-on-year (the share of private labels on the Slovak market accounts for more than 1/5 of the total turnover of fast-moving products and maintains approximately the same level).

Nielson's Report (2018) that “The largest markets for private-label products are found primarily in the more mature European retail markets.” Regarding the exposure of private labels, we can also talk about a significant shift, as the results of research conducted by Go4insight (conducted for the Slovak Food Chamber in 2019; Tovarandpredaj, 2017) show that while in 2013 the share of private labels was longer at the level of 20%, in 2019 it was found that this share increased by 1.3% (compared to the previous year) and it has reached a level of more than 25%. Most private labels are represented on the shelves of retail chains Lidl (56%), followed by Kaufland and Coop Jednota (23%) and the lowest share is held by the CBA chain at 13%. Interesting findings of the mentioned research are that private labels in Slovakia have the largest representation in the category of food in discount stores and warehouses, where their share is up to 50%; the share of private labels on store shelves in Slovakia is as follows—milk (68%), canned products (40%), packaged meat products (42%), pasta (39%), natural cheeses (37%), other dairy products (35%), oils (34%), packaged long-life bread (31%), soft drinks (29%), processed products (27%), water and mineral water (24%), chocolate confectionery (22%), non-chocolate confectionery (12%) spirits (9%), beer (9%), and wine (6%); the share of private labels is 25%, with 18% representing foreign production and the remaining 7% domestic, Slovak. At the same time, most foreign private labels are displayed in the Lidl chain, up to 51% (Kádeková et al., 2020a). Unfortunately, as far as the vegan product category is concerned, there is no detailed database yet that can be used as a basis for evaluating how many of these products are represented in the private label category. However, this is a modern trend and it is therefore highly likely that the number/share of the products in question will continue to increase over time.

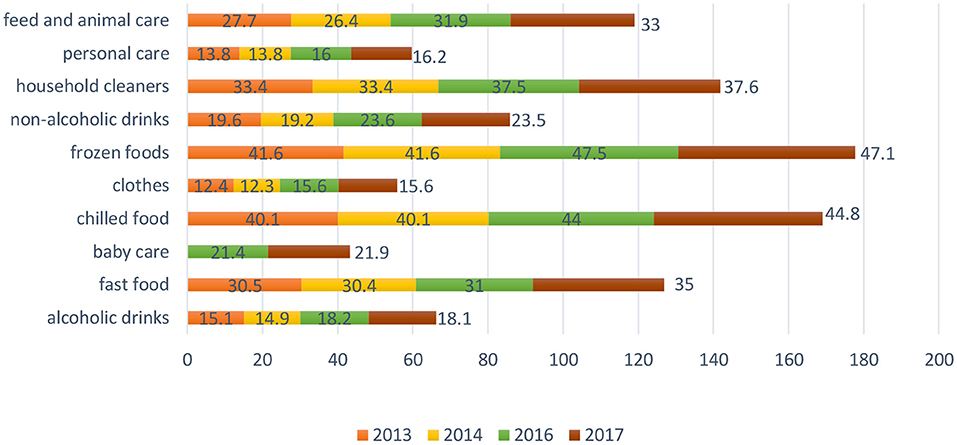

Muruganantham and Priyadharshini (2017) pointed out that the highest number of research studies were carried out in the food and grocery product category as a leading private label's research area. In terms of the percentage of private labels in individual product categories, it can be said that in Europe, private labels are currently mostly represented in the category of frozen and chilled foods, or detergents, animal feed and consumer food (IRI, 2018; Figure 1); or to the fact that according to the results of research carried out by IRI in 2017, household cleaners (36.2%), personal care products (34.2%) and hygiene products (36.4%), resp. alcoholic beverages (26%), frozen meals (24.8%) and ready meals (22.2%) are the most preferred product lines in Greece. The results of Nielsen's research from the same year carried out in the Czech Republic show that Czechs prefer private milk and dairy products (average 31.25%), cooking oils (36%), canned food (average 34%), salty snacks (29%), packaged bread (27%), or sweet packaged pastries (25%) and juices (22%).

Figure 1. Percentage of private labels in individual product categories in Europe (2013 and 2014, resp. 2016 and 2017). Source: own processing according to available sources.

As far as customers themselves and thus consumers are concerned, a significant shift in the perception and purchase of private labels can be also observed. While the results of research carried out by the GfK Slovakia in 2010 show, that every Slovak household has popular brands in its usual and regular purchases, which it prefers, while in some categories of goods there is a stronger preference for brands, resp. while in the case of long-life milk, “less prestigious” private labels account for almost 80% of total consumption (TASR, 2010); thus, the results of a survey conducted by TNS Slovakia in June 2012 clearly stated that the most popular private labels are TESCO brands (49% of respondents), COOP Jednota (44% of respondents), Kaufland (32% of respondents), Billa (23% of respondents), and CBA (21% of respondents); and that products sold under the private labels of the COOP Jednota and TESCO are bought by women rather than by men (Fedorková, 2012). These then underline and supplement our findings in the given area, when in 2014 we found out, that of a total of 644 respondents, up to 57% of respondents purchase the private labels regularly, up to 17% explicitly prefer them over traditional brands (especially in the case of the TESCO retail chain), and that the most frequently purchased categories of private labels include milk and dairy products, salty snacks and water, lemonades and juices (Nagyová and Košičiarová, 2014). In the case of our further research, we have gradually recorded a slight shift in the area, as in 2020 we have found out, that of the total number of 1,190 respondents, up to 81.26% buy private labels (of which 28.49% buy them regularly and 52.77% buy them sporadically); furthermore, up to 30.17% explicitly prefer them in their purchases over traditional brands; up to 39.83% buy mainly classic private labels; and that as far as specific product categories are concerned, private labels are most often purchased in the product categories milk and dairy products, then mineral waters, lemonades and juices, salty delicacies, confectionery, delicacies and preserves, frozen semi-finished products, meat and fish, respectively coffee and tea and at least in product categories ready meals and alcoholic beverages (Košičiarová, 2020).

According to Yang (2012), the perceived quality disparities amongst private label brands and national brands are an important determining of intention to purchase. Private labels perceived quality directly affects the purchase intent of consumers toward private labels brands (Liljander et al., 2009; Yan et al., 2019). The findings of such studies conclude that the higher the strength or the more favorable the perception, the more likely the consumer will purchase the private labels and develop patronage toward them. Therefore, it can be assumed that private labels perceived quality has a positive effect on the consumer's private labels purchase intention (Gangwani et al., 2020).

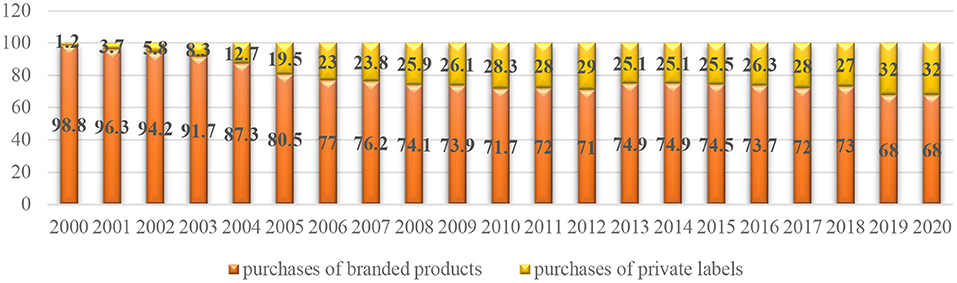

Based on the results in Figure 2, it can be said that purchasing or the preference of private labels by the Slovak consumers has an increasing tendency, which is largely caused not only by the lower price of the products but also by higher confidence in them, respectively their ever-increasing quality, which in many cases becomes not only comparable but also higher compared to traditional brands.

Figure 2. Percentage share of purchases of branded products and products sold under private labels in Slovakia. Source: own processing according to available sources.

As we have in 2020 also focused on the research on how Slovak respondents perceive private labels, whether they are their end-users and whether they also buy them in new and specific categories of private labels (a total of 1,120 respondents participated in the given research)—when our results show that Slovaks buy private labels not only in the food segment, but also in the category of cosmetics and cleaning products, where they buy them every month, or in the category of clothing, which they buy mainly depending on the current offer; further that up to 45.45% of respondents buy also specific types of private labels, such as e.g., organic assortment, gluten-free assortment, low-fat assortment, etc., and they buy them mainly due to a healthy lifestyle (36.45% of respondents); respectively that they are also the end-users of private label products (61.52% of respondents; Kádeková et al., 2020a,b). Perceived value is revealed to absolute influence consumer willingness to buy a product (Sweeney and Soutar, 2001). Furthermore, price-quality linkages significantly influence private labels purchase, especially in a category that consumers perceive as riskier (Sinha and Batra, 1999). Consumer's perceived value is debatably the most decisive determinant factor of purchase intention (Gangwani et al., 2020).

The submitted research paper focuses on those private labels, which aim to address customers with specific needs and requirements. As we have pointed out in the Material and Methods Section, the main aim of our research was to find out whether Slovak consumers know and subsequently buy products of the private brand targeted on vegans and vegetarians, in which product categories they do so, how they perceive them and what attracts and discourages them.

A total of 2,011 respondents participated in the research, of which up to 978 respondents (i.e., 48.67%) know, and 709 respondents (i.e., 35.26%) regularly buy products of the given private label, i.e., vegan products. The specific representation of respondents can be seen in Table 1, from which it is clear that in the case of our research the most represented were women (77.2%), respondents aged from 21 to 30 years (65.85%), respondents with secondary education (40.59%), students, respectively employed people (45.81 and 38.75%), households with two members (31.6%) and net monthly family income over 1,501 € (37.01%), respondents from a city with a population over 100,000 (21.17%) and respondents from Nitra and Bratislava region (30.47 and 24.34%).

At the same time, our results bring many interesting findings, especially the fact that even if it could be assumed that the given products are known and bought only by vegans, resp. vegetarians, it is not quite so—from the above sample of respondents (i.e., 978) up to 32.72% stated that in terms of consumption/their diet they fall into the category “I eat everything” (Figure 3; assumption 1 was not confirmed).

Nezlek and Forestell (2020) stated that not enough attention has been paid to possible differences among types of vegetarians, including differences in why people are vegetarians. Some research suggests that vegans are meaningfully different from other types of vegetarians (Matta et al., 2018; Nezlek et al., 2018; Rosenfeld, 2019), but more attention needs to be paid to possible differences between vegetarians who have similar eating habits but different reasons for being vegetarians. As noted by Rosenfeld (2018) as well as by Nezlek and Forestell (2020), the recent research converges to suggest that the three most common motivations among vegetarians are concerns about animals, health, and the environment. It is important to note that these motives are not mutually exclusive. Most vegetarians report being motivated by a combination of motives to adopt a vegetarian diet (Janssen et al., 2016; Rosenfeld and Burrow, 2017a,b; Armstrong Soule and Sekhon, 2019). Finally, some people may be motivated to adopt a plant-based diet by the appeal of the “idea” of being vegetarian. This is referred to as social identity motivation and reflects the desire to identify with a social group because of its perceived positivity and potential benefits for one's self-esteem (Plante et al., 2019).

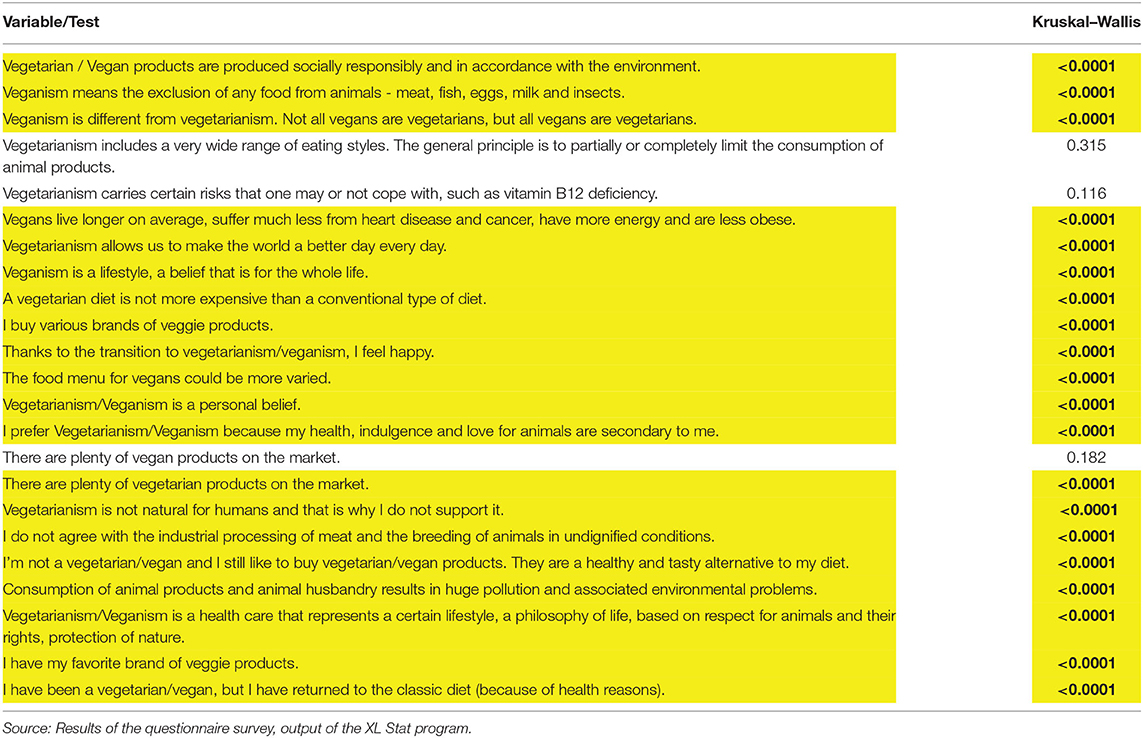

In our research, we were interested in the respondents' opinions on individual statements about veganism and vegetarianism, in the questionnaire survey we have also formulated certain statements to which the respondents had to react in the range of answers, i.e., on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 meant I disagree at all and 5 I strongly agree. We have then looked at the answers not only in terms of which statement the respondents agree with the most and with which the least, but also whether there is a dependence between agreeing with the statement and the form of the respondent's diet.

As it can be seen from Tables 2, 3, our respondents mostly agree with the statement “Vegetarianism means the exclusion of any food from animals—meat, fish, eggs, milk, and insects” and the least with the statement “I was a vegetarian, but I returned to classic diet for health reasons” (so we have the least respondents of this category), respectively it can be seen that there are indeed dependencies between the level of agreement with the statement in the form of the respondent's diet, where these dependencies indicate higher levels of agreement between respondents from the vegan and vegetarian categories (Table 3, highlighted in yellow).

Table 3. Results of the Kruskal–Wallis Test (dependence between agreement with the statement and the form of the respondent's diet).

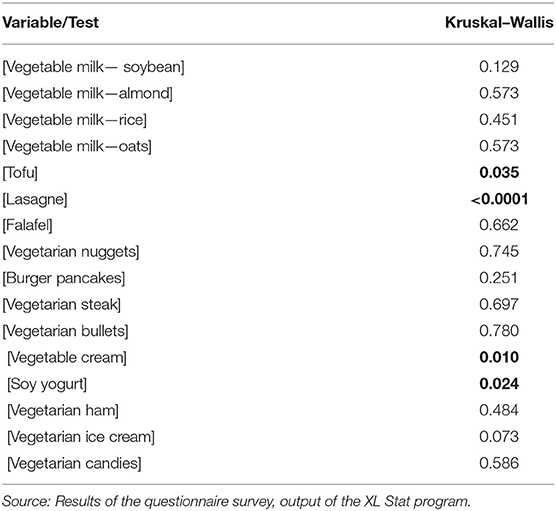

As our research further shows, up to 45.81% of respondents buy a given private label sporadically and another 26.69% buy it regularly, while we have shown a clear relationship between buying the given private label and the form of respondent's diet (p-value was at the level of significance α ≤ 0.001, the value of the Phi coefficient was equal to 0.5747 and the value of the Cramer's coefficient was 0.4064, which indicates a mean and at the same time statistically significant dependence). As we were interested, how often do the respondents buy or consume the researched private label products, we have focused on the given questions in the questionnaire survey. The results of our research show, that our respondents most often consume and at the same time buy tofu, vegetable cream and soy yogurt (almost daily; assumption 2 was confirmed). The least purchased foods in a given range of private labels are lasagne, vegetarian candies, vegetarian bullets and burger pancakes, which are bought and consumed only occasionally, or not at all. From the point of view of statistical evaluation of the obtained data, it proved to us that again it is true that the given products are rather bought and consumed by vegans and vegetarians, respectively, by women rather than men, where the preference was found for products such as tofu, lasagne, vegetable cream and soy yogurt (Table 4).

Table 4. Results of the Kruskal–Wallis test (dependence between the consumption of specific products of the researched private label and the respondent's sex).

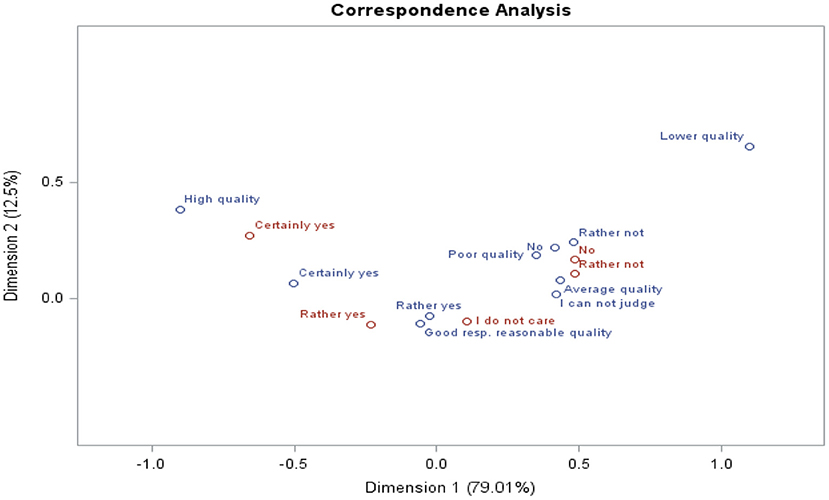

Subsequently, we have focused on the perception of the range of private labels in terms of their quality level, comparability of quality and subsequent preference for purchase by our respondents. The results of our research show that the respondents are generally satisfied with the range of these private labels-−79.27% of respondents perceive the quality level of private labels targeted on vegans and vegetarians as good or appropriate; in terms of quality comparability 48.8%, respectively, 22.28% of respondents think that it is rather, respectively, certainly comparable to the quality of similar products of traditional brands; in 79.27% of respondents the given private label evokes adequate quality at a reasonable price and up to 31.59% of respondents prefer the products of the given private label to traditional brand products in their purchase (12.13% explicitly prefer them; assumption 3 was confirmed). From the point of view of the results of the correspondence analysis, which is also called as a reciprocal averaging, and which is a useful data science visualization technique for finding out and displaying the relationship between categories (Tibco.com, 2022; Figure 4), it can be said that it applies that those respondents who perceive the quality of the private label and its products as good and high also think that it is comparable to the quality of traditional brand products and they have a fundamental preference for the given private label.

Figure 4. Output of the correspondence analysis. Source: Results of the questionnaire survey, output of the SAS program 9.4.

The above-mentioned dependence between the preference of the products of the private label targeted on vegans and vegetarians and the perception of the quality of its products, resp. the dependence between the preference for products labeled with the private label targeted on vegans and vegetarians and the comparability of their quality is confirmed by the results obtained from SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1, which show a statistically significant dependence, but this dependence is perceived as small rather than medium (p-value was in both cases at the significance level α ≤ 0.001, the value of the Phi coefficient was equal to 0.4434 in the case of H4 and the value of the Cramer coefficient of 0.2217 and in the case of H5 0.3676 and 0.1838, which indicates a weak and statistically significant dependence).

The last questions we have focused on in our questionnaire survey are the questions:

• concerning the evaluation of selected aspects of vegan products of the private label targeted at vegans and vegetarians, where the respondents had on the scale of 1–5, where 1 meant very low and 5 very high, to evaluate aspects such as the level of promotion, price level, breadth of assortment, the attractiveness of design/packaging, level of quality, and overall acceptability of products; and

• regarding the decisive factors in the purchase of a given private label and the disincentives to purchase it.

The results of our research declare that in terms of perception, resp. evaluations of selected aspects are rated as the best acceptability of products and their quality level, as in these aspects the respondents gave the highest ratings (Appendix A; assumption 4 was confirmed), in terms of decisive factors “playing” in favor of purchasing private label products are the good previous experience and reasonable price and quality (Appendix B) and the factor that mainly discourages from the purchase of these products is their taste (Appendix C).

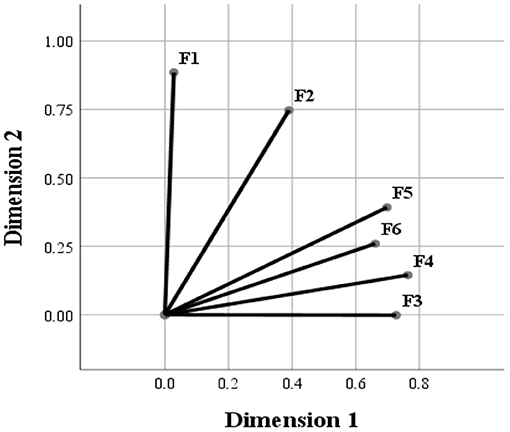

In addition, by applying CATPCA on selected aspects of the private label targeted on vegans and vegetarians we obtained a deeper insight into respondents' evaluations. Test explained 62.8 of variance and identified two latent factors based on component loading (Figure 5). The first latent component includes price and quality level. The second component involves promotion level, assortment width, attractiveness packaging, and product's overall acceptability.

Figure 5. Purchasing factors analyzed by CATPCA. Source: Results of the questionnaire survey, output of the SPSS version 25. F1- price level, F2- quality level, F3- promotion level, F4- assortment width, F5- product's overall acceptability, F6- attractiveness of packaging.

Marangon et al. (2016) also examined consumers' awareness of vegan food, to investigate the consumers' attitudes and preferences toward vegan food products. Factors related to the country of origin were found to be critical in the purchasing process. Assortment width and quality belong to one of the most important factors when purchasing vegetarian/vegan food products, however, the results suggested that only 8% of customers are willing to pay a premium price. Based on results by Kapoor and Kumar (2019) and Underwood and Klein (2002), Yildirim et al. (2017), the attractiveness of products packaging is important especial for young people. For customers older than 25 is much more important the information provided by the producer on the packaging. Consumers tend to search for a vegan indicator and use their brand beliefs to give the conclusion of whether the product is vegetarian/vegan suitable. The result shows the role of the vegan indicator in the vegan product label. In this context can be concluded that the promotion level of vegetarian/vegan products belongs to the least important factors influencing the purchasing behavior of the customers worldwide.

Purchasing affordable vegetarian and vegan products could be a solution to the problem regarding the sustainability of meat production and its consumption and also a new challenging trend. The submitted contribution intended to point out the fact that Slovak consumers are starting to focus on new categories of private labels, specifically on vegan/vegetarian products, which are still just looking for their regular consumers. For this reason, the main aim of our research was to find out whether Slovak consumers know and subsequently buy products of the private label targeted on vegans and vegetarians, in which product categories they do so, how they perceive them and what attracts and discourages them. The research was carried out on a sample of 2,011 respondents, where it was found that even though up to 48.67% of respondents know the given private label, only 35.26% of our respondents are its real consumers and users, so, indeed, the private label is still looking for its customers. However, our results point to another interesting finding, and therefore that even if it could be assumed that the products of this private label will be bought only by respondents from the vegan or vegetarian category, the opposite is true—the private label is known and bought by a respondent from the category “I eat everything.” To fulfill the main aim of the article, we have formulated a total of four theoretical assumptions and five statistical hypotheses, based on the evaluation which we can say that three theoretical assumptions were confirmed and all examined dependencies were proved, although in some cases it can be said that they are weak rather than moderate addictions.

The importance of submitted research is highlighted by the fact that private labels have been growing. However, we realize that our research has also some limitations and barriers. We focused just to the limited area of Slovakia. There is also a fact that solved problem is evolving over time and situation described in the submitted paper may change in close future. This is the point from which further possibilities and trends for future research can arise. In terms of our recommendations for practice and possible limits of the research can be said unequivocally that we are aware that this research is unique and specific and therefore it is not possible to provide a thorough discussion of our findings—the area of private labels is largely researched by us, as far as new and specific categories of these brands are concerned, there are still large gaps and reserves in the market. Therefore, we perceive this contribution as original and unique in the subject area and it can therefore serve as a guide for further similar research, whether in this area or even from managerial, economic or marketing point of view. Results of our research could be also used in the practice by food companies and sellers. As our results show that these products are also bought by omnivorous consumers, it is clear that chains should focus on the better promotion of these products, as it is still true that several respondents are unaware of this type of private label and therefore they do not buy me. In terms of the quality level of these products, our respondents are generally satisfied, but the possibilities for improvement can be still found and the customer regularly asks for them. It is questionable whether the chain wants to go into a “bigger” fight for a potential customer, but since it is still true that private labels are a source of competitive advantage and a means of building a positive corporate image (Košičiarová, 2020), we think it will pay off.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

IK, ZK, PS, and LS contributed to all steps of research (concept, questionnaire, data collecting), database and manuscript as well as a literature review. IK, ZK, and PS did statistical evaluation. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2022.858048/full#supplementary-material

Amato, P. R., and Partridge, S. A. (2008). The Origins of Modern Vegetarianism. Eatveg.com. Available online at: http://www.eatveg.com/veghistory.htm

Anesbury, Z. W., Jürkenbeck, K., Bogomolov, T., and Bogomolova, S. (2020). Analyzing proprietary, private label, and non-brands in fresh produce purchases. Int. J. Mark. Res. 63, 597–619. doi: 10.1177/1470785320948335

Armstrong Soule, C. A., and Sekhon, T. (2019). Preaching to the middle of the road: strategic differences in persuasive appeals for meat anti-consumption. Br. Food J. 121, 157–171. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-03-2018-0209

Beardsworth, A. D., and Keil, E. T. (1993). Contemporary vegetarianism in the UK. Challenge and incorporation? Appetite 20, 229–234. doi: 10.1006/appe.1993.1025

Beneke, J.-, and Carter, S. (2015). The development of a consumer value proposition of private label brands and the application thereof in a South African retail context. J. Retail. Consum. Services 25, 22–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.03.002

Beneke, J., Flynn, R., Greig, T., and Mukaiwa, M. (2013). The influence of perceived product quality, relative price and risk on customer value and willingness to buy: a study of private label merchandise. J. Prod. Brand Manage. 22, 218–228. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-02-2013-0262

Bontemps, C.h., Orozco, V, and Réquillart, V. (2008). Private labels, national brands and food prices. Rev. Indus. Organ. 33, 1–22. doi: 10.1007/s11151-008-9176-x

Bronnenberg, B. J., Dubé, J. P., and Sanders, R. E. (2020). Consumer misinformation and the brand premium: a private label blind taste test. Market. Sci. 39, 382–406. doi: 10.1287/mksc.2019.1189

Campos, C. I., de Pitombo, C. S., Delhomme, P., and Quintanilha, J. A. (2020). Comparative analysis of data reduction techniques for questionnaire validation using self-reported driver behaviors. J. Saf. Res. 133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2020.02.004

Chan, S. C., and Coughlan, A.T. (2006). Private label positioning: quality versus feature differentiation from the national brand. J. Retail. 82, 79–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jretai.2006.02.005

Chung, L., and Lee, E. (2017). Store brand quality and retailer's product line design. J. Retail. 93, 527–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jretai.2017.09.002

Cramer, H. (1946). Mathematical Methods of Statistics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 282.

Cramér, H. (1976). Half a century with probability theory: some personal recollections. Ann. Probab. 4, 509–546.

Cuneo, A., Lopez, P., and Yagüe, M. J. (2012). Measuring private labels brand equity: a consumer perspective. Eur. J. Market. 46, 952–964. doi: 10.1108/03090561211230124

Data Science Analytics. (2022). Categorical Principal Components Analysis (CATPCA) with Optimal Scaling. Available online at: http://bayes.acs.unt.edu:8083/BayesContent/class/Jon/SPSS_SC/Module9/M9_CATPCA/SPSS_M9_CATPCA.htm

Dent, M. (2020). The Meat Industry is Unsustainable. IDTexEx. Available online at: https://www.idtechex.com/en/research-article/the-meat-industry-is-unsustainable/20231

Diallo, M. F. (2012). Effects of store image and store brand price-image on store brand purchase intention: application to an emerging market. J. Retail. Consum. Services 19, 360–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2012.03.010

Diallo, M. F., Chandon, J. L., Cliquet, G., and Philippe, J. (2013). Factors influencing consumer behaviour towards store brands: evidence from the French market. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manage. 41, 422–441. doi: 10.1108/09590551311330816

Dodds, W. B.-, Monroe, K. B.-, and Grewal, D. (1991). Effects of price, brand, and store information on buyers' product evaluations. J. Mark. Res. 28, 307–319. doi: 10.1177/002224379102800305

Fedorková, J. (2012). Najvýhodnejšie Nákupy Robíme v Kaufland. Available online at: http://www.tns-global.sk/informacie-pre-vas/tlacove-spravy/najvyhodnejsie-nakupy-robime-v-kauflande

Flavián, C., Guinalíu, M., and Gurrea, R. (2006). The influence of familiarity and usability on loyalty to online journalistic services: the role of user experience. J. Retail. Consum. Services 13, 363–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2005.11.003

Friedman, M. (1937). The use of ranks to avoid the assumption of normality implicit in the analysis of variance. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 32, 675–701. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1937.10503522

Friedman, M. (1940). A comparison of alternative tests of significance for the problem of m rankings. Ann. Math. Stat. 11, 86–92. doi: 10.1214/aoms/1177731944

Gangwani, S., Mathur, M., Chaudhary, A., and Benbelgacem, S. (2020). Investigating key factors influencing purchase intention of apparel private label brands in India. Acad. Strat. Manage. J. 19. Available online at: https://www.abacademies.org/articles/investigating-key-factors-influencing-purchase-intention-of-apparel-private-label-brands-in-india-9284.html

Gfk (2021). Gfk Consumer Reporter. Available online at: https://www.gfk.com/products/gfk-consumer-life-reports

Gil-Cordero, E., and Cabrera-Sánchez, J. P. (2020). Private label and macroeconomic indexes: an artificial neural networks application. Appl. Sci. 10:6043. doi: 10.3390/app10176043

Gil-Cordero, E., Rondán-Cataluña, F. J., and Sigüenza-Morales, D. (2020). Private label and macroeconomic indicators: Europe and USA. Administr. Sci. 10:91. doi: 10.3390/admsci10040091

Google Trends (2020). Google Trends. Available online at: https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=allandq=veganism

Greenacre, M. (2001). “Scaling: correspondence analysis,” in International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, eds N. J. Smelser, and P. B. Baltes (Pergamon), 13508–13512. doi: 10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/00502-7

Ho, S. (2021). Google Trends 2020: Interest In Veganism At Record High According To New Report. Available online at: https://www.greenqueen.com.hk/google-trends-2020-interest-veganism-all-time-high-new-report/

IRI (2018). Private Label in Western Economies. Available online at: http://vriesversplatform.nl/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/IRI-PL-Report_July-2018.pdf

Janssen, M., Busch, C., Rödiger, M., and Hamm, U. (2016). Motives of consumers following a vegan diet and their attitudes towards animal agriculture. Appetite 105, 643–651. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.06.039

Kádeková, Z., Košičiarová, I., and Rybanská, J. (2020a). Privátne Značky ako Alternatíva Nákupu. Praha: Verbum Praha.

Kádeková, Z., Košičiarová, I., Vavrečka, V., and DŽupina, M. (2020b). The impact of packaging on consumer behavior in the private label market - the case of Slovak consumers under 25 years of age. Innovat. Mark. 16, 62–73. doi: 10.21511/im.16(3).2020.06

Kapoor, S., and Kumar, N. (2019). Does packaging influence purchase decisions of food products? A study of young consumers of India. Acad. Mark. Stud. J. 23:16.

Kaufland, sk (2021). Zo Sortimentu. Available online at: https://www.kaufland.sk/sortiment/nase-znacky.html

Košičiarová, I. (2020). Privátne Značky Ako Významný Atribút Budovania Firemného ImidŽu Potravinárskych Obchodných Retazcov Pôsobiacich na Slovensku. Bratislava: Univerzita Komenského v Bratislave.

Košičiarová, I., Kádeková, Z., DŽupina, M., Kubicová, L., and Dvorák, M. (2020a). Comparative analysis of private labels - private labels from the point of view of a millennial customer in Slovakia, Czech Republic and Hungary. Sustainability 12:9822. doi: 10.3390/su12239822

Košičiarová, I., Kádeková, Z., Kubicová, L., Predanocyová, K., Rybanská, J., DŽupina, M., et al. (2020b). Rational and irrational behavior of Slovak consumers in the private label market. Potravinárstvo Slovak J. Food Sci. 14, 402–411. doi: 10.5219/1272

Košičiarová, I., and Nagyová, L. (2014). Private Label: The Chance How to Increase the Consumer's Interest in a Proper Retail Chain. ICABR, 452–467. Available online at: http://www.icabr.com/fullpapers/icabr2014.pdf

Kruskal, W. (1952). Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 47, 583–621. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1952.10483441

Kumar, N. (2007). Private Label Strategy: How to Meet the Store Brand Challenge. Brighton: Harvard Business Review Press

Li, D., Liu, Y., Hu, J., and Chen, X. (2021). Private-brand introduction and investment effect on online platform-based supply chains. Transport. Res. Part E 155:102494. doi: 10.1016/j.tre.2021.102494

Liljander, V., Polsa, P., and Van Riel, A. (2009). Modelling consumer responses to an apparel store brand: store image as a risk reducer. J. Retail. Consum. Services 16, 281–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2009.02.005

Lim, W. M., Teh, P. L., and Ahmed, P. K. (2019). How do consumers react to new product brands? Mark. Intell. Plann. 38, 369–385. doi: 10.1108/MIP-09-2018-0401

Lybeck, A., Holmlund-Rytkönen, M., and Sääksjärvi, M. (2006). Store brands vs. manufacturer brands: consumer perceptions and buying of chocolate bars in Finland. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 16, 471–492. doi: 10.1080/09593960600844343

Marangon, F., Tempesta, T., Troiano, S., and Vecchiato, D. (2016). Toward a better understanding of market potentials for vegan food. A choice experiment for the analysis of breadsticks preferences. Agric. Agric. Sci. Proc. 8, 158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.aaspro.2016.02.089

Marques, C., Da Silva, R. V., Davcik, N. S., and Faria, R. T. (2020). The role of brand equity in a new rebranding strategy of a private label brand. J. Bus. Res. 117, 497–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.022

Matta, J., Kesse-Guyot, E., Goldberg, M., Limosin, F., Czernichow, S., Hoertel, N., et al. (2018). Depressive symptoms and vegetarian diets: results from the Constances Cohort. Nutrients 10:1695. doi: 10.3390/nu10111695

Matthews, B. W. (1975). Comparison of the predicted and observed secondary structure of T4 phage lysozyme. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 405, 442–451. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(75)90109-9

Mediaguru (2021). Privátní Značky Tvor í Ctvrtinu Trhu, Pozici Posiluj í Diskonty. Available online at: https://www.mediaguru.cz/clanky/2021/06/privatni-znacky-tvori-ctvrtinu-trhu-pozici-posiluji-diskonty/

Messina, V. K., and Burke, K. I. (1997). Position of the American dietetic association. Vegetarian diets. J. Am. Dietet. Assoc. 97, 1317–1321. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(97)00314-3

Muruganantham, G., and Priyadharshini, K. (2017). Antecedents and consequences of private brand purchase. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manage. 45, 660–682. doi: 10.1108/IJRDM-02-2016-0025

Nagyová, L., and Košičiarová, I. (2014). Privátne Značky: Fenomén Označovania Výrobkov 21. Storočia na Európskom Trhu. Nitra: Slovenská Polnohospodárska Univerzita.

Nalca, A, Boyaci, T, and Ray, S. (2018). Brand positioning and consumer taste information. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 268, 555–568. doi: 10.1016/j.ejor.2018.01.058

News Gallup (2020). Americans Who Are Vegetarians or Vegans (Trends). Available online at: https://news.gallup.com/poll/238346/americans-vegetarians-vegans-trends.aspx

Nezlek, B. J., and Forestell, A. C. (2020). Vegetarianism as a social identity. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 33, 45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cofs.2019.12.005

Nezlek, J. B., Forestell, C. A., and Newman, D. B. (2018). Relationships between vegetarian dietary habits and daily well-being. Ecol. Food Nutr. 57, 425–438. doi: 10.1080/03670244.2018.1536657

Nielsen (2019). V Januári sa DôleŽitost Privátnych Značiek Zvyšuje. Available online at: https://www.nielsen.com/sk/sk/insights/article/2019/in-january-importance-of-private-brands-is-increasing/

Nielson's Report (2018). The Rise and Rise Again of Private Label. Available online at: www.nielsen.com

Pearson, K. (1900). On the criterion that a given system of deviations from the probable in the case of a correlated system of variables is such that it can be reasonably supposed to have arisen from random sampling. Philos. Mag. 50, 157–175. doi: 10.1080/14786440009463897

Pinar, M., and Tulay, G. (2020). “Comparing private label brand equity dimensions of the same store: their relationships, similarities, and differences,” in Improving Marketing Strategies for Private Label Products (Hershey: IGI Global), 61–82. doi: 10.4018/978-1-7998-0257-0.ch004

Plante, C. N., Rosenfeld, D. L., Plante, M., and Reysen, S. (2019). The role of social identity motivation in dietary attitudes and behaviors among vegetarians. Appetite 141:104307. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2019.05.038

PLMA (2020). Industry News. Private Label Today. Available online at: https://www.plmainternational.com/industry-news/private-label-today

Rosenfeld, D. L. (2018). The psychology of vegetarianism: recent advances and future directions. Appetite 131, 125–138. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2018.09.011

Rosenfeld, D. L. (2019). A comparison of dietarian identity profiles between vegetarians and vegans. Food Qual Prefer. 72, 40–44. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2018.09.008

Rosenfeld, D. L., and Burrow, A. L. (2017a). The unified model of vegetarian identity: a conceptual framework for understanding plant-based food choices. Appetite 112, 78–95. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.01.017

Rosenfeld, D. L., and Burrow, A. L. (2017b). Vegetarian on purpose: understanding the motivations of plant-based dieters. Appetite 116, 456–463. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.05.039

Samit, C. E. L. A., and Cazacu, S. (2016). The attitudes and purchase intentions towards private label products in the context of economic crisis: a study of thessalonian consumers. Ecoforum J. 5, 1–10.

Sanchez-Sabate, R., Badilla-Briones, Y., and Sabaté, J. (2019). Understanding attitudes towards reducing meat consumption for environmental reasons. A qualitative synthesis review. Sustainability 11:6295. doi: 10.3390/su11226295

Šedík, P., Šugrová, M., Horská, E., and Nagyová, L. (2017). Comparative study on private label brand “K - take it veggie” in Slovakia and the Czech Republic. Ekon. Manage. 9, 59–71.

Segovia-Siapco, G., and Sabaté, J. (2019). Health and sustainability outcomes of vegetarian dietary patterns: a revisit of the EPIC- Oxford and the Adventist Health Study-2 cohorts. Eur J Clin Nutr. 72, 60–70. doi: 10.1038/s41430-018-0310-z

Šimčikas, S. (2018). Is the Percentage of Vegetarians and Vegans in the U.S. Increasing? Animal Charity Evaluators. Available online at: https://animalcharityevaluators.org/blog/is-the-percentage-of-vegetarians-and-vegans-in-the-u-s-increasing/

Sinha, I., and Batra, R. (1999). The effect of consumer price consciousness on private label purchase. Int. J. Res. Mark. 16, 237–251. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8116(99)00013-0

Sutton-Brady, C., Taylor, T., and Kamvounias, P. (2017). Private label brands: a relationship perspective. J. Bus. Indus. Mark. 32, 1051–1061. doi: 10.1108/JBIM-03-2015-0051

Sweeney, J. C., and Soutar, G. N. (2001). Consumer perceived value: the development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 77, 203–220. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4359(01)00041-0

TASR (2010). PRIESKUM: Predaj Značkových Tovarov SI UdrŽal Postavenie aj v Case Krízy. Available online at: http://www.edb.sk/sk/spravy/prieskum-predaj-znackovych-tovarov-si-udrzal-postavenie-aj-v-case-krizy-a2398.html

Tibco.com (2022). What is Correspondence Analysis? Available online at: https://www.tibco.com/reference-center/what-is-correspondence-analysis

Timko, C. A., Hormes, J. M., and Chubski, J. (2012). Will the real vegetarian please stand up? An investigation of dietary restraint and eating disorder symptoms in vegetarians versus non-vegetarians. Appetite 58, 982–990. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.02.005

Tovarandpredaj (2017). Privátna Značka Kauflandu K-Classic Opät Získala Ocenenie Najdôveryhodnejšia Značka 2017. Available online at: https://www.tovarapredaj.sk/2017/12/06/privatna-znacka-kauflandu-k-classic-opat-ziskala-ocenenie-najdoveryhodnejsia-znacka-2017/

Trautman, J., Rau, S. I., Wilson, M. A., and Walters, C. (2008). Vegetarian students in their first year of college. Are they at risk for restrictive or disordered eating behavior? Coll. Stud. J. 42, 340–347.

Underwood, R. L., and Klein, N. (2002). Packaging as brand communication: effects of product pictures on attitude towards the package and brand. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 10, 58–68. doi: 10.1080/10696679.2002.11501926

University Libraries (2022). SPSS Tutorials: Pearson Correlation. Available online at: https://libguides.library.kent.edu/SPSS/PearsonCorr

Vahie, A., and Paswan, A. (2006). Private label brand image: its relationship with store image and national brand. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manage. 34, 67–84. doi: 10.1108/09590550610642828

Vegan Official Labels (2020). Indexing of Official Vegan Certification Around the World. Available online at: http://vegan-labels.info/

Wang, L., Chen, J., and Song, H. (2021). Manufacturer's channel strategy with retailer's store brand. Int. J. Prod. Res. 59, 3042–3061. doi: 10.1080/00207543.2020.1745313

Yan, L., Xiaojun, F., Li, J., and Dong, X. (2019). Extrinsic cues, perceived quality, and purchase intention for private labels. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 31, 714–727. doi: 10.1108/APJML-08-2017-0176

Yang, D. (2012). The strategic management of store brand perceived quality. Phys. Proc. 24, 1114–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.phpro.2012.02.166

Yildirim, S., Rocker, B., Pettersen, M. K., et al. (2017). Active packaging applications for food. Comprehens. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 17, 165–199. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12322

Keywords: private label, vegan, vegetarian, consumer behavior, sustainable food consumption

Citation: Košičiarová I, Kádeková Z, Šedík P and Smutka Ĺ (2022) Vegetarian and Vegan Private Label Products as a Challenging Trend in Addressing the Customers Within Sustainable Food Consumption—A Case Study of Slovakia. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 6:858048. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2022.858048

Received: 19 January 2022; Accepted: 09 March 2022;

Published: 04 April 2022.

Edited by:

Giuseppe Di Vita, University of Turin, ItalyReviewed by:

Adriano Gomes Cruz, Adriano Gomes da Cruz, BrazilCopyright © 2022 Košičiarová, Kádeková, Šedík and Smutka. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zdenka Kádeková, emRlbmthLmthZGVrb3ZhQHVuaWFnLnNr

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.