- 1F.C. Manning School of Business, Acadia University, Wolfville, NS, Canada

- 2Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador, Eastern Health, St. John's, NL, Canada

- 3School of Nutrition and Dietetics, Acadia University, Wolfville, NS, Canada

The degrees to which diets are consistent with food system sustainability, are the result of influences across scales of social interaction. This study considers the importance and limitations of institutional influence over integration of sustainable food systems ideas and concepts in dietetics practice. Working with the International Confederation of Dietetics Associations (ICDA) and their Member Country Associations our objectives are to (a) understand ways by which ICDA could contribute to global sustainable food systems, (b) develop a method for assessing ICDA's contribution to sustainable food systems and (c) test initial data collection options for this assessment. Assessment of institutional support for sustainable food system integration to practice was conducted by examining usage data (from Google Analytics) of the ICDA sponsored online sustainable food system Toolkit, and website content analysis. Study results establish baseline data and indicate initially modest support for backing integration of sustainable food system concepts within the dietetics profession.

Introduction

Contributions of our global food systems to an unsustainable world are clear (Mason and Lang, 2017; Mosby et al., 2020), and the need for food system participants to make positive change toward sustainable food systems (SFS) and to be able to assess progress is increasingly pressing. Among the vast network of actors within the food system who can make contributions toward SFS, dietitians and nutritionists are often overlooked. Dietitians work in various roles across the food system that are well-positioned to support pro-SFS behavior change across their communities (Vogliano et al., 2015; Dietitians Canada, 2020; Spiker et al., 2020). For this study, researchers worked with a global body of registered dietitians, and their representative association, the International Confederation of Dietetics Associations (ICDA), to (a) understand ways by which ICDA and member affiliates could contribute to SFS, (b) develop a method for assessing ICDA and member affiliates' contributions to SFS, and (c) test initial data collection options for this assessment.

The following sections introduce concepts of institutional influence for behavior change as they relate to ICDA, dietitians, and sustainable food systems. We continue by exploring the importance of addressing barriers to behavior change, and the possibility of assessing the extent to which barriers to change are being reduced or removed. This is followed by presentation of the methods used to develop and select assessment measures, as well as the data collection process. The final sections present results and a discussion of the findings.

ICDA, Institutions, and Behavioral Influence

Organizational and institutional theorists have long explored the interplay of influence between institutions and their members (Meyer and Rowan, 1977). Institutions directly influence individual behaviors and group norms through “shared rules and typifications that identify categories of social actors and their appropriate activities or relationships” (Barley and Tolbert, 1997). Likewise, individuals, as organizational participants, both enact and influence the rules and norms of legitimate behavior for and within institutions. As an international confederation, the ICDA has no direct influence over the daily routines of registered dietitians-nutritionists (RDNs), yet they play an important role in setting the global context of standards and expectations for RDNs. Further, ICDA must also work to ensure that the management of the organization and replication of norms are not overly reliant on, or expressive of, one region of the world or cultural identity. Within this context, the ICDA governing Board of Directors supports and promotes international standards of practice that are derived by and for RDNs across the globe. Through communications via their newsletter, website, and member conferences, basic professional standards of practice and norms for activities and patterns of behavior are shared and reproduced. Given that RDNs occupy various roles of influence across the food system (Dietitians Canada, 2020), the ICDA is in a powerful position to support standards, norms and expectations for RDNs to be a positive influence toward global sustainable food systems.

The relationship between institutions and individual sustainability related values and behavior has been observed in several different industries. Velasco and Harder (2014) examined an education for sustainable development (ESD) intervention enacted by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies with their Youth as Agents of Behavior Change program. Their study highlights the importance of an institutional and societal context that supports behavior change for sustainability. Without institutional and broader contextual support, people can learn about the need for sustainability, but transfer to behavior change will be inhibited (Velasco and Harder, 2014). Another study exploring the influence of small and medium business owners in New Zealand showed that appropriate institutional support can foster the development of sustainability-related identities, which as a result, can lead to behavior, organizational, and cultural change toward sustainability (Kiefhaber et al., 2020).

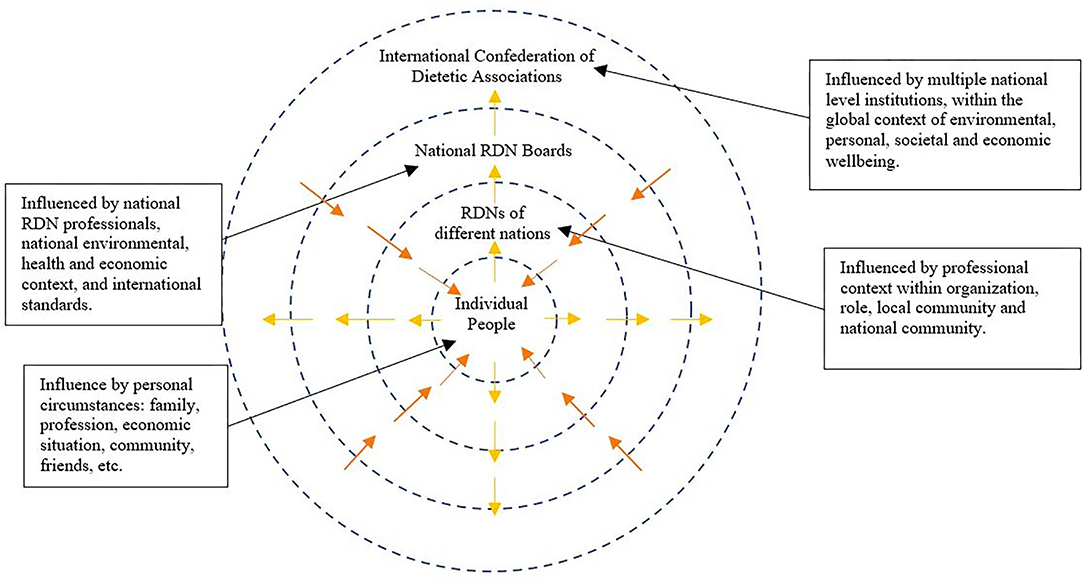

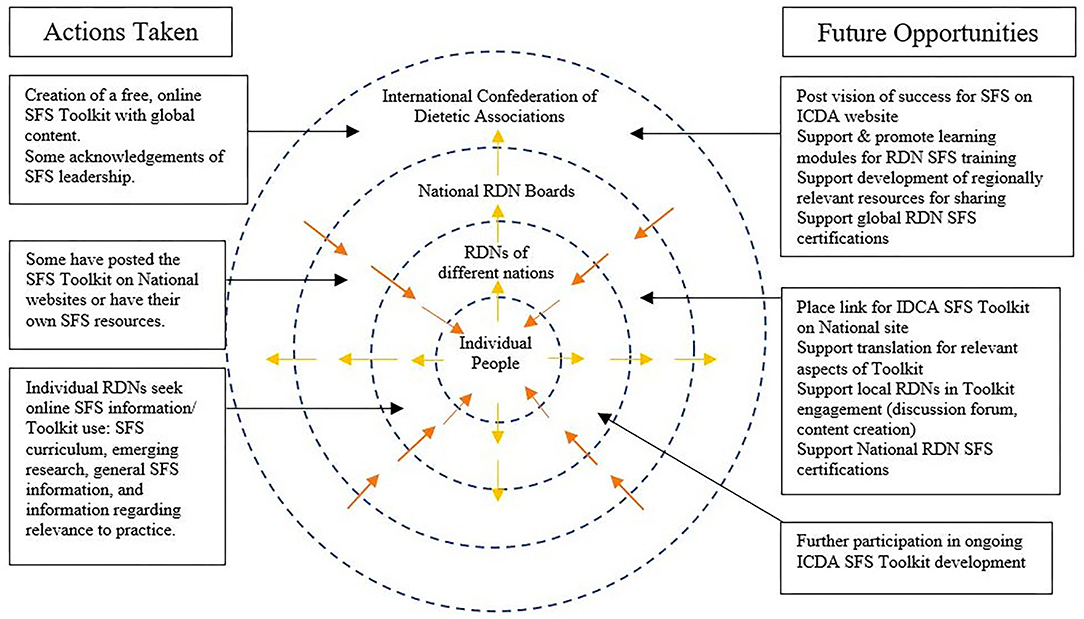

Similar to these organizational settings, the ICDA can leverage change toward SFS within the dietetic profession by setting a broader institutional context that highlights the importance of sustainable food and understanding sustainable food systems. As an international association that reaches a large audience the ICDA can facilitate learning and leverage behavior change that supports SFS (Carlsson and Callaghan, 2022). Figure 1 illustrates domains of influence across four concentric rings of scale within the dietetics profession: populations of focus (individual people) for RDNs, practicing RDNs who work with individual people and institutions of various nations, national level Associations of RDNs, and finally the International Confederation of Dietetic Associations (ICDA).

Reducing Barriers for Behavior Change

Setting a positive context and expectations is often not enough to illicit behavior change. When people are interested in learning or doing something new, such as adopting a new hobby or habit, or in some significant way changing their behavior pattern, barriers often arise. Because barriers to change can slow or completely block drivers that promote a desired change, identifying barriers and creating and implementing strategies that support the removal of barriers can be productive in facilitating individual, organizational and social change. The need to address barriers to change has been seen in a variety of contexts, including: corporate shifts toward sustainability (Lozano, 2007), sustainable consumer behavior (Rizzi et al., 2020; Chwialkowska and Flicinska-Turkiewicz, 2021), public health promotion and programming (Ljungqvist et al., 2014), and programs to enhance effectiveness in workplace settings (Mohajer and Singh, 2018; Maltinsky and Swanson, 2020).

In a study of Registered Dietitians of Canadian (Carlsson et al., 2020), participants were asked what barriers they saw for achieving SFS. Four high-level barriers were identified: (1) competing food-health messages that lack scientific evidence, (2) inadequate opportunities for developing understanding of interactions between food, people, and the environment, (3) cultural expectations of stable access to a variety of imported foods year-round, and (4) cultural de-prioritization of food. While this study took a comprehensive approach to understanding barriers to SFS as perceived by dietitians, the context was limited to Canada, a high-income country. It is reasonable to assume that barriers may differ between countries of different income levels and cultural contexts.

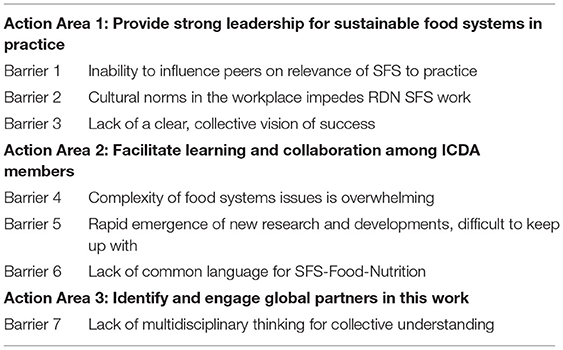

Building on the Canadian research, another study explored perceived barriers to SFS from an international audience of dietitians (Carlsson et al., 2019). Working with the ICDA, researchers found that the ICDA membership perceived seven high-level barriers to moving toward SFS globally: (1) professional culture that is reluctant to embrace sustainability related research and practice, (2) lack of common ground for understanding the scope and complexity the SFS challenges, (3) the food price paradox (high food prices inhibit access, low food prices can incentivize unhealthy diet patterns), (4) profits as priority, (5) food safety/waste trade-offs, (6) access to adequate infrastructure and technology, (7) environmental degradation. As a loosely coupled global association of national dietetics associations, there is a relatively low degree of dependence among the organizations of which the ICDA is comprised. Thus, the ICDA is limited in its ability to address some of these barriers directly. Many are tied to social and economic policies at the country or international level. However, of these high-level barriers identified, the first two barriers were within ICDA's purview. Within these two ICDA relevant barriers, seven additional sub-barriers were identified (Carlsson and Callaghan, 2022):

Reluctance within Professional Culture:

Inability to influence peers on relevance of SFS to practice.

Cultural norms in the workplace impedes N-D SFS work.

Lack of a clear, collective vision of success.

Lack of Common Ground borne from Complexity:

Complexity of food systems issues is overwhelming.

Rapid emergence of new research and developments, difficult to keep up with.

Lack of common language for SFS-Food-Nutrition.

Lack of multidisciplinary thinking for collective understanding.

Process as Indication of Progress

In order to assess progress toward significant objectives (such as sustainable diets, or climate adaptation) within a complex system (such as the food system, or the earth's climate), evaluators of programs are encouraged to use a mix of both outcome and process indicators (Bagheri and Hjorth, 2007; Niemann et al., 2017). Outcome indicators demonstrate that a specific objective has been achieved and are most useful when assessing progress toward a specific, clearly defined end goal. Process indicators are more suitable for contexts and problems that are constantly changing, where the time horizon for achievement of the objective is difficult to determine, and the exact measure of success is fuzzy due (in part) to the many voices of stakeholders who can influence the outcome. Process indicators “measure progression toward the achievement of an outcome (e.g. ‘resilience to drought'), but do not guarantee or measure the final outcome itself” (Bours et al., 2014).

Like adaptation to a changing climate, or supporting society in reducing its reliance on plastics, the evolution toward food systems sustainability is wickedly complex (Hull et al., 2018; Lehtonen et al., 2018). In relation to sustainable food systems, the influence of ICDA allows them to provide professionally relevant information and support activities designed to enable dietetic associations and their members to incorporate SFS framing into their practice. Ideally, this will assist in promoting dietary patterns that are consistent with SFS on local and global levels. Within this context, process indicators are a more useful tool than outcome indicators for assessing contribution toward SFS.

The operationalization of process indicators are actions (processes). The previous study of ICDA membership presented above, also explored what types of supports/actions RDNs felt would be useful to them in their efforts to integrate SFS within their practice (Carlsson and Callaghan, 2022). Three high-level action areas were identified. These action areas are shown in Table 1, with each associated barrier to SFS that could potentially be addressed by the action/process.

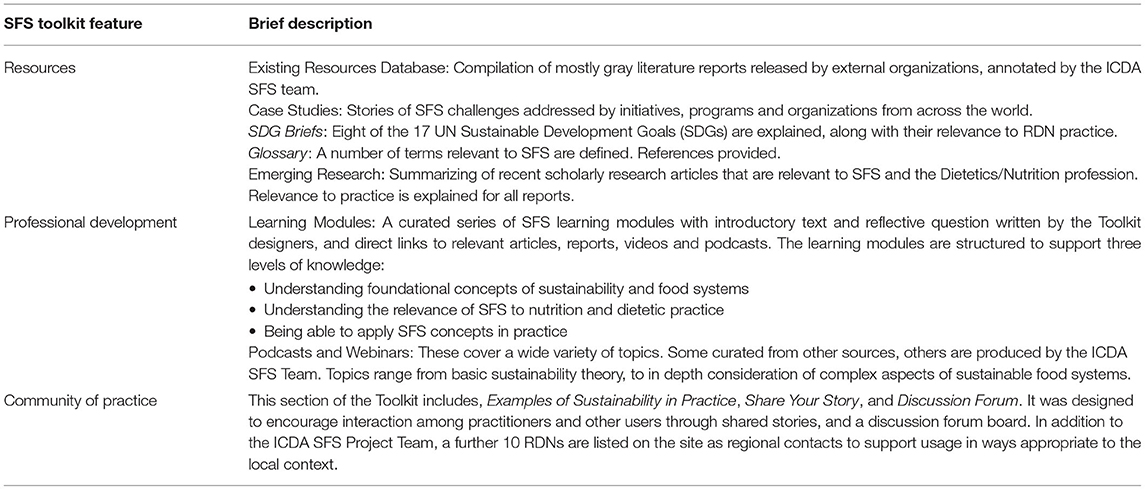

The identification of these three clear areas of action, and associated barriers that could be addressed by ICDA, led ICDA to invest in development of an online SFS Toolkit1 for global dietitians (Carlsson et al., 2019). The SFS Toolkit was designed to demonstrate SFS leadership by ICDA, assist others in taking SFS leadership, and to facilitate learning and collaboration (the first two action areas). Identifying and engaging global partners in SFS work was beyond the initial scope for the SFS Toolkit. In existence since September 1, 2020, the SFS Toolkit contains three main sections: Resources, Community of Practice, and Professional Development. The Resources section includes various types of literature, reports and case studies. The Community of Practice section provides a number of opportunities for users to share their own stories, and interact with one another in a way that could build community around SFS. Finally, the Professional Development section provides a curated set of learning opportunities regarding SFS related webinars, podcasts, etc. Refer to Table 4 for more details regarding the various Toolkit elements.

Development of the SFS Toolkit is a strong indication of ICDA's intention to make positive contributions toward integrating SFS into dietetic practice. Of course, the mere existence of a toolkit is not enough. Building the toolkit was a step in the right direction, further actions must be taken, however, before barriers to change will diminish. Assessment of toolkit usage, through Google Analytics and a user Self-Assessment survey, allowed for initial consideration of contributions made by ICDA and member affiliates toward supporting a shift within the profession toward sustainable food systems.

Methods

Data Collection

This study is one component of a larger body of work, and builds directly from earlier publications (Carlsson et al., 2019; Carlsson and Callaghan, 2022). As with the earlier work, the population for this study was dietitians who are registered with their country's ICDA Member Association. Initial invitation to participate was sent from the ICDA Board via email to member country ICDA representatives. At the time of this work, there were 43 ICDA member countries, each with one or two elected ICDA representatives, elected by numerous registered dietitians within each country. Participant recruitment, and inclusion criteria, are fully discussed in a previously published paper (Carlsson and Callaghan, 2022). Ethical approval for the methods used was granted by Acadia University, Research Ethics Board.

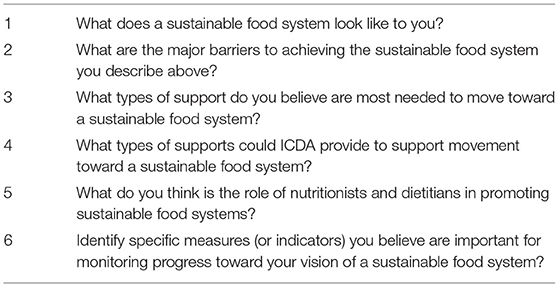

Initial data collection was done through a Delphi Inquiry Method (administered through an online survey system, Lime Surveys © 2017), where participants were asked a set of the same questions in three consecutive rounds. For each consecutive round, participants were given a composite summary of responses from the prior round and asked to respond to the questions again considering what their colleagues have expressed. This method of data collection allowed us to facilitate a quasi-dialogue with members, over time, and across the globe. In the first round, 72 ICDA members participated from 30 countries (including all continents except Antarctica). In round two, 61 members participated, and 50 participants completed round three. Australia had the highest level of participation, followed by Portugal and Greece.

Data and analysis presented for this publication is one component of a larger study. Six questions were asked in the Delphi Inquiry, as shown in Table 2. Results and analysis for the first five questions are the subject of another paper (Carlsson and Callaghan, 2022). Initial ideas for how to monitor progress were taken from participants responses to questions 6 below, and further framed by responses to questions 2 and 4 as presented in other published work (Carlsson and Callaghan, 2022).

The vast majority of respondents' answers to question 6 spoke to broad scale societal, human health, infrastructure, and ecological indicators that are beyond the bounds of this study, such as: affordability of local food, food type intake, energy production, and fish stocks. When data collection of the Delphi Inquiry process was complete, respondents had suggested over 500 possible indicators of progress toward SFS. Of the indicators suggested, the researchers zoomed in on those relevant to the barriers identified and the action areas highlighted in Table 1. Indicators were culled according to the following criteria:

1) Relevance to ICDA

2) Suggested by participants

3) Availability of data

4) Feasibility of data collection (measurable, time, cost)

In total, 16 indicators to assess progress toward dismantling barriers that impede integration of SFS into RDN practice were identified. Of these, 12 were feasible to research within the constraints of this study. The full list of indicators are provided in Tables 3a–g, along with data sources and results of data collection. For each barrier, there are two or more potential indicators of progress, and for each indicator, there are often multiple sources of data identified. Indicators with an asterisk are those suggested by Delphi participants.

Table 3. (a) Barrier 1 – Inability to influence peers on relevance of SFS to practice; (b) Barrier 2 – Cultural norms in the workplace impede RDN SFS work; (c) Barrier 3 – Lack of a clear, collective vision of success; (d) Barrier 4 – Complexity of food systems issues is overwhelming; (e) Barrier 5 – Rapid emergence of new research and developments, difficult to keep up with; (f) Barrier 6 – Lack of common language for SFS-food-nutrition; (g) Barrier 7 – Lack of multidisciplinary thinking for collective understanding.

As illustrated in Tables 3a–g, data collection for the identified indicators involved several different methods, including website content analysis, descriptive statistics, and google analytics. In addition to the websites of ICDA, and Member Associations, the ICDA SFS Toolkit was used extensively in this research. A detailed description of the various aspects of the Toolkit relevant to this research is provided in Table 4.

To assess the pages within Resources and Professional Development a variety of analytical tools were used. Many of the pages were assessed for content of key terms that were relevant to the barrier being assessed. Researchers also used Google Analytics to understand user interaction with the SFS Toolkit [Google Analytics, (n.d)]. The bounce rate for pages was also examined along with the average time spent per page, and exits per page. Bounce rate is a metric which refers to the percentage of single-page sessions in which there was no interaction with the page (i.e., that a person exits the page without page interaction). A higher bounce rate (e.g., 100%) indicates that on average, users interacted less with the page. A lower bounce rate (e.g., 0%) indicates higher interaction with the page. Exits include moving to another page on the site, or clicking a link on the page which leads to an external website (e.g., some resources on the workshops and webinars page lead to other websites).

In addition to analysis of specific page use within the Toolkit, the ICDA SFS Toolkit includes an anonymous, voluntary Self-Assessment Tool. This Self-Assessment asked users a number of questions designed to help them navigate the Toolkit, quickly identifying information relevant to their interests. This also gave researchers insight into the learning needs of users. The 100 Self-Assessments (from 21 countries) competed between September 1, 2020–January 13, 2021, were used as a source of data for this study. The data collection period varied slightly among the different elements of the Toolkit. Date ranges for each analysis and detailed descriptions of data collection method for each indicator is presented in Table 3.

Results

Tables 3a–g report the findings for each of the indicators, the indicator data sources (IDS), and their associated barrier. In the text below, the data are discussed.

Action Area 1: Provide Strong Leadership for Sustainable Food Systems in Practice

Barrier 1: Inability to Influence Peers on Relevance of SFS to Practice

Results for IDS-1, IDS-2 and IDS-3 reveals that ICDA and the majority of Member Associations have not yet documented actionable commitments to integrating SFS into dietetics practice. With no SFS focus in their strategic plan, no existing position statement for practice, and just over a handful of Member Associations with an SFS related policy statement, there was no documented evidence that SFS has penetrated to the core of institutional planning and policy making. Usage stats from the other indicator data sources however, counter this second possibility. The results of IDS-7 show that of the 100 respondents to the Toolkit Self-Assessment, 32% indicated that they were interested in learning more about all aspects of sustainability in relation to food systems.

With respect to traffic on the SDG briefs and learning modules pages (IDS-8), is appears that users spent adequate time on each page to review and consider what was presented, and interact with the material provided. Almost half of the users who examined the SDG briefs page (167) explored the page interactively by clicking through to the SDG briefings as indicated by the 51% bounce rate. Similarly, just over half of the users who accessed the Learning Modules main page, clicked into one of the three modules offered on that page (bounce rate 47%). The analytics from the learning modules is more difficult to interpret. Each Learning Module includes explanatory text, reflection questions, references, and links to other websites for further information. As shown in the Data Results table, people spent the most time, on average, on Learning Module 1 (3 min, 51 s/231 pageviews), a bit less on Learning Module 2 (2 min, 34 s/69 pageviews), and the least time on Learning Module 3 (1 min, 24 s/53 pageviews). The text on the Learning Module pages is more generally contextual, with the more rigorous explanations and learning coming from the downloadable files and the video links from other websites. It could be that users downloaded the files that they wanted, then exited the site to examine the detailed more closely. Further, each click through to a different website would count as an exit of the site, rather than interaction with the material. Thus, while the data shows that people are using the various pages, limitations of the data inhibit our ability fully understand the extent to which they are interacting with, and learning from, the material provided.

Barrier 2: Cultural Norms in the Workplace Impede RND SFS Work

Results from IDS-9 and IDS-10 reveal that ICDA has not promoted standards for practice relevant to SFS in dietetics practice. For IDS-11, content analysis of ICDA and ICDA-SFS newsletters was conducted to find recognition of SFS work by RDNs. Between January 2017 and April 2021, analysis of 13 ICDA newsletters, which are sent to all registered members of ICDA, revealed seven recognitions of RDN SFS work; analysis of four ICDA-SFS newsletters, which is sent to people who explicitly sign-up for the newsletter on the SFS Toolkit, found four recognitions of this type of recognition out of nine recognition opportunities.

Barrier 3: Lack of a Clear, Collective Vision of Success

For both IDS-13 and IDS-14, content analysis was conducted for the ICDA and Member Association website to see if the ICDA member generated Vision of Success for SFS was posted or referenced. No such references or postings were found.

Action Area 2: Facilitate Learning and Collaboration Among ICDA Members

Barrier 4: Complexity of Food Systems Issues Is Overwhelming

Data for examining means by which IDCA is addressing this barrier were taken entirely from usage data of the ICDS SFS Toolkit. The data from IDS-15 are summarized above (IDS-8), however it is worth noting that the process indicator suggested for IDS-15 was toolkit usage.

IDS-16 examines usage stats from specific pages of the Toolkit. During the 8 month date range of data collection, there were almost 350 visits to the Workshops, Webinars and Podcast page of the Toolkit, as well as the Resource Database page. There was more traffic on the Resources Database, and the bounce rate for this page was lower than for other pages (41.68%). The bounce rate for the Workshops Webinars and Podcasts page was higher relative to some other pages (67.69%). It is important to note that direct comparison between bounce rate numbers is misleading. All of the items on the Resource Database page keep users within the website, but most of the items on the Workshops Webinars and Podcasts take users to other website. Thus, the bounce rate away from the Resources Database page is an accurate reflection of people leaving without further explorations of the material on the page, whereas the bounce rate for Workshops Webinars and Podcasts likely includes interactions with the page that took users to other websites. Emerging research had significantly fewer visits, but data collection only occurred over ~2.5 months. Analysis of clicks from the ICDA SFS newsletters onto specific articles on the Emerging Research page showed moderate interest.

Data from ISD-18 shows that during the period of data collection 104 people filled in the Self-Assessment form. When asked what type of sustainability issues they would like to learn more about, just over 18% chose “select all.”

Barrier 5: Rapid Emergence of New Research and Developments, Difficult to Keep Up With

The Emerging Research section was not part of the initial Toolkit design. In early 2021, however, funding to support this became available. Therefore, the relatively lower number of page views (94) needs to be understood with this in mind.

With IDS-21, the intention was to assess discussions of research in the Toolkit's Discussion Forum. Unfortunately, there was insufficient traffic on the Discussion Forum to allow for analysis.

Barrier 6: Lack of Common Language for SFS-Food-Nutrition

Of the RDNs/Trainees who completed the Self-Assessment, IDS-22 shows that 45% of them were interested in sustainable informed curriculum.

The data results for IDS-23 and IDS-24 have been summarized above (IDS-8 and IDS-16 respectively). To understand Toolkit usage to support development of a common language for SFS, we also examined Google Analytics from the Glossary page. Results showed that relatively few people (59 views) reviewed the glossary page, but those that did spend time to review the material, and interact with it.

Action Area 3: Identify and Engage Global Partners in This Work

Barrier 7: Lack of Multidisciplinary Thinking for Collective Understanding

Both process indicator sources of data collection were deemed not practical, and beyond the project capacity for current collection (IDS-27, IDS-28). No data were collected to assess progress toward addressing this barrier.

Discussion

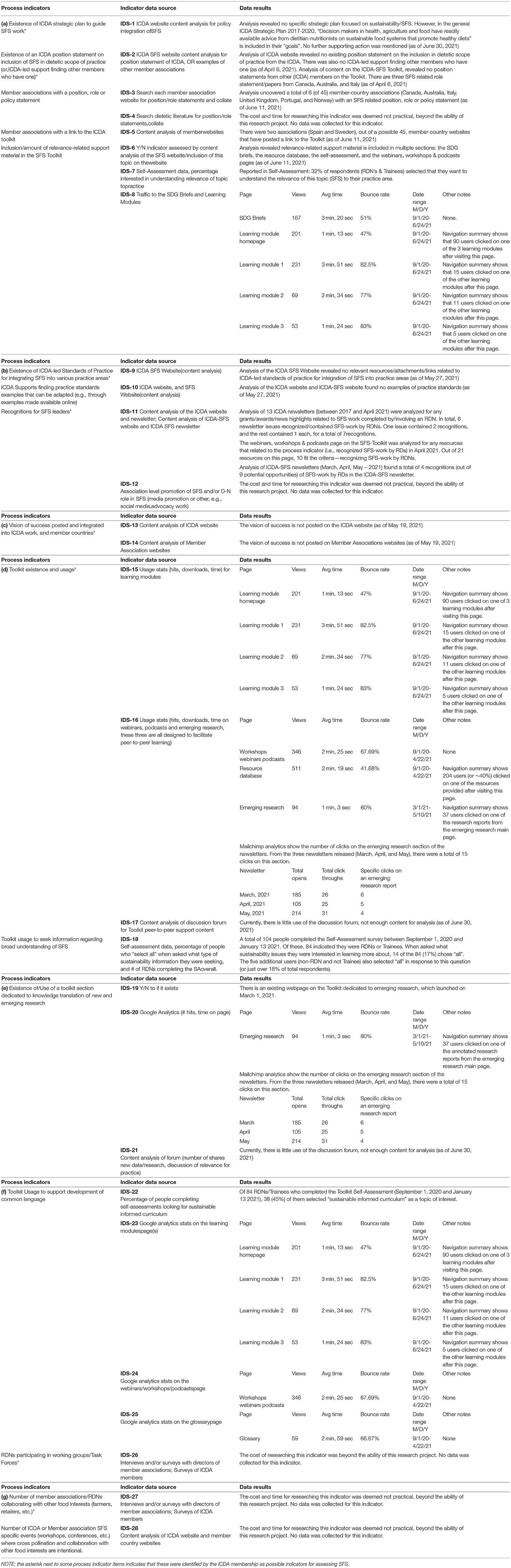

Tracking and analysis of data collected over 9 months during the first year of the Toolkit's existence provides a baseline for understanding how the website is being used. Two types of data were collected: contiguous and binary. The intent with this data is not to arrive at a single score, nor are we are able to provide conclusive answers regarding progress toward or away from the dismantling of barriers to the integration of SFS in RDN practice. We do, however, provide an initial narrative regarding the contribution made by ICDA and Member Associations, toward promoting integration of SFS to dietetic practice. Progressive tracking over years, and further development of the ICDA SFS Toolkit, will allow researchers to provide a more nuanced understanding of these indicators as well as possibly identify and develop additional indicators. This discussion is organized around Action Areas identified as important by RDNs toward supporting SFS, and consideration is given to both actions taken and potential action to be taken by ICDA, National/Regional Dietetics Associations, and RDNs themselves. Actions and future opportunities across scales of the profession are illustrated in Figure 2.

Action Area 1: Provide Strong Leadership for Sustainable Food Systems in Practice

ICDA has demonstrated leadership in supporting SFS as relevant to RDN practice by providing a free, accessible, online Toolkit with relevance-related support material in multiple sections (i.e., SDG briefs, learning modules, resource database, self-assessment tool, webinars and workshops, emerging research). This resource provides RDNs with tools and information that, theoretically, can provide grounding in SFS and its relevance to practice. Strong grounding in the relevance of SFS to dietetics practice will help RDNs facilitate the shift of cultural norms within workplace environments toward greater acceptance of SFS. This shift can also be supported by establishment of SFS certifications and acknowledgment and promotion of SFS leadership by dietetics institutions. Results illustrate that minimal institutional level efforts have been dedicated toward this type of support. We are unsure if this is because standards of practice or certifications have not developed, or if documentation of such standards have not yet been posted to their website and/or the Toolkit.

Leadership can also be demonstrated by articulating and promoting a clear vision of success in relation to a particular goal. The ICDA membership has generated such a vision for SFS in the dietetics profession, however more can be done to use the vision to its potential as a guide to orient action. Public promotion and acknowledgment, and inclusion of the vision in strategic documents, are two ways to more fully leverage the potential of the Vision of Success. Finally, that only two Member Associations provide a link to the ICDA SFS Toolkit on their own member country websites (ISD-5) is either: further indication that SFS remains a peripheral concern for most Member Association, or that the SFS Toolkit has been found to not be relevant (additional research is required to determine this).

The data collected demonstrates that the ICDA and the Member Associations have initiated leadership in supporting integration of SFS in dietetics practice. However, given the urgency of global sustainability challenges, much more must be done and more quickly. While these early steps of leadership are good, a more proactive approach would strengthen the field in this area (see recommendations for practice below).

Action Area 2: Facilitate Learning and Collaboration

Active use of the ICDA SFS Toolkit can make strong contributions toward SFS learning and collaboration. Further, frustration stemming from the overwhelming complexity of SFS issues coupled with the daunting task of keeping pace with rapidly emerging new research can be calmed by systematic and consistent support in learning and application to practice. Usage statistics from Emerging Research and Learning Modules pages indicate that RDNs are seeking these types of learning materials and activities. Building the mechanisms for learning is necessary for progress in this area, however, it is not sufficient. It is possible that SFS learning and collaboration is strongly inhibited by lack of time and institutional support. This brings the discussion back to the need for strong leadership. Once SFS learning for RDNs is legitimized through certification, and collaboration is rewarded through strong institutional support, uptake in this area will likely gain pace.

Action Area 3: Identify and Engage Global Partners in This Work

Unfortunately, as noted earlier, the research team did not have capacity to investigate activities in this area. Nevertheless, it is our belief that action by RDNs toward engaging global partners will be facilitated by strong leadership. Further, without strong institutional support in this area, the energy and time required to initiate and sustain such partnerships will be impede progress. Investigation of activities designed to promote multidisciplinary thinking is an opportunity for future research.

Limitations

The authors acknowledge challenges and limitations of website usage data. Two significant challenges stand-out. First, simply because someone looks at a page, we cannot know what is gleaned from their examination of the resource. A proxy for the relative utility of a page or Toolkit resource can be estimated by tracking usage over time. Alternatively, a more accurate measure of utility can be assessed by interviewing and/or surveying users of the Toolkit. The second limitation of website usage data is that if interest in certain aspects of the Toolkit wain, without further research it is impossible to interpret why such a drop-off occurred. Perhaps, for example, if users no longer show interest in a specific set of resources it could be because their need for knowledge provided by that resource has been satisfied, or perhaps the recourse is no longer seen as adequate or relevant. As this field progresses, a broader reading of the socio-ecological and institutional contexts will be required to further ground website usage data. Additionally, data collection for this study was limited to a seven to 8 month period, and Self-Assessment data were only obtained for a 4 month period. Longer periods of data collection for future assessments will grant additional depth to this study.

Concluding Reflections

This paper has argued the importance of institutional leadership for integrating SFS into dietetics practice. In concert with our initial objectives we have identified ways by which ICDA can contribute to SFS through addressing barriers RDNs experience toward integration of SFS in dietetics practice. We have developed and tested a method for assessing ICDA's contribution toward addressing these barriers, and established a baseline regarding current ICDA and Member Association actions aimed at addressing barriers. Results show that ICDA, and some ICDA Member Associations, have taken initial steps toward demonstrating leadership for SFS, and supporting learning and collaboration for SFS. Further, results from Google Analytics indicate that RDNs from around the globe are interested in learning more about SFS. Our results also show that there remain several relatively easy and low cost steps that could be taken by the institutions to further reduce barriers to SFS experienced by RDNs. Finally, additional research is needed to identify ways dietetics institutions can support productive partnerships of diverse expertise designed to enhance collaboration on SFS.

Even with the forementioned limitations, we believe that this research has made a contribution toward understanding the importance of institutional support for SFS in the field of dietetics, and we have provided suggestions to enhance this support on into the future.

Recommendations for Practice

In order for RDNs to reach a tipping point, where SFS integration into practice is a norm, stronger and more proactive leadership from institutions is required. The commitment of time, energy, and financial resources to development and maintenance of the ICDA SFS Toolkit has been positive. However, for the Toolkit to have maximum benefit RDNs must know about the resource, be encouraged to use it, and have time to use/integrate it. ICDA could promote the toolkit, and/or various aspects of it, to member associations through the ICDA newsletter. This may influence these associations to use it in their own work or share it on their own websites in the future. Additional potential promotion and outreach options include: learning modules that steer learners to emerging research and discussion the forum, promotion of new emerging research papers and discussions on Twitter, and national/international workshops that introduce these aspects of toolkit to participants.

Finally, greater efforts need to be put toward creating incentives for Toolkit usage, and integration of ideas into practice. Positive incentives for usage will likely be motivated by: (1) social media promotion of emerging research and debates, (2) recognition and promotion of individual RDN SFS leadership in their practice, (3) development of a SFS certification, and (4) development of SFS curriculum modules for Dietetics education.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Acadia University, Ethics Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

EC was primary contributor to the framing of the study. RP was primarily responsible for website usage and content data collection, analysis, and writing. LC contributed toward study conceptualization and editing. EC and LC contributed in paper writing. All authors approved the final submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

LC was a Registered Dietitian. RP was a Dietetics Intern in Canada. EC was not a dietitian, but a scholar of business and sustainability. Generous support for student research was provided by the International Confederation of Dietetics Associations and the Harrison McCain Emerging Scholars Fund.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Please see ICDA Sustainable Food Systems Toolkit: https://icdasustainability.org.

References

Bagheri, A., and Hjorth, P. (2007). A framework for process indicators to monitor for sustainable development: practice to an urban water system. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 9, 143–61. doi: 10.1007/s10668-005-9009-0

Barley, S. R., and Tolbert, P. S. (1997). Institutionalization and structuration: studying the links between action and institution. Organ. Stud. 18, 93–117 doi: 10.1177/017084069701800106

Bours, D., McGinn, C., and Pringle, P. (2014). Guidance Note 2: Selecting Indicators for Climate Change Adaptation Programming. Guidance for MandE of Climate Change Interventions Sea Change, UKCIP, 10. Available online at: https://www.ukcip.org.uk/wp-content/PDFs/MandE-Guidance-Note2.pdf (accessed December 20, 2021).

Carlsson, L., and Callaghan, E. (2022). The social license to practice sustainability: concepts, barriers and actions to support nutrition and dietetics practitioners in contributing to sustainable food systems. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. doi: 10.1080/19320248.2022.2034559. [Epub ahead of print].

Carlsson, L., Callaghan, E., and Broman, G. (2020). Assessing community contributions to sustainable food systems: dietitians leverage practice, process and paradigms. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2020, 1–27. doi: 10.1007/s11213-020-09547-4

Carlsson, L., Callaghan, E., and Laycock Pedersen, R. (2019). Building Common Ground for Sustainable Food Systems in Nutrition and Dietetics. International Confederation of Dietetics Associations. Available online at: https://icdasustainability.org/ (accessed October 18, 2021).

Chwialkowska, A., and Flicinska-Turkiewicz, J. (2021). Overcoming perceived sacrifice as a barrier to the adoption of green non-purchase behaviours. Int. J. Consumer Stud. 45, 205–20. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12615

Dietitians Canada. (2020). The Role of Dietitians in Sustainable Food Systems and Sustainable Diets. Toronto, ON: Dietitians of Canada, 40. Available online at: https://www.dietitians.ca/Advocacy/Toolkits-and-Resources?n=The%20Role%20of%20Dietitians%20in%20Sustainable%20Food%20Systems%20and%20Sustainable%20Diets%20(role%20paper)andPage=1# (accessed January 15, 2022).

Google Analytics (n.d.) Behavior. Available online at: analytics.google.com/ (accessed September 10 2021).

Hull, R. B., Robertson, D., and Mortimer, M. (2018). Wicked leadership competencies for sustainability professionals: definition, pedagogy, and assessment. Sustainability 11, 171–77. doi: 10.1089/sus.2018.0008

Kiefhaber, E., Pavlovich, K., and Spraul, K. (2020). Sustainability-related identities and the institutional environment: the case of new zealand owner–managers of small- and medium-sized hospitality businesses. J. Bus. Ethics 163, 37–51. doi: 10.1007/s10551-018-3990-3

Lehtonen, A., Salonen, A., Cantell, H., and Riuttanen, L. (2018). A pedagogy of interconnectedness for encountering climate change as a wicked sustainability problem. J. Clean. Prod. 199, 860–867. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.186

Ljungqvist, I., French, J., and Apfel, F. (2014). Social Marketing Guide for Public Health Programme Managers and Practitioners. Glasgow: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 105.

Lozano, R. (2007). Orchestrating organisational changes for corporate sustainability: overcoming barriers to change. Greener Manag. Int. 57, 43–64.

Maltinsky, W., and Swanson, V. (2020). Behavior change in diabetes practitioners: an intervention using motivation, action planning and prompts. Patient Educ. Counsel. 103, 2312–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.04.013

Mason, P., and Lang, T. (2017). Sustainable Diets: How Ecological Nutrition Can Transform Consumption and the Food System, 1 edition. London, New York: Routledge.

Meyer, J. W., and Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: formal structure as myth and ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 83, 340–363.

Mohajer, N., and Singh, D. (2018). Factors enabling community health workers and volunteers to overcome socio-cultural barriers to behaviour change: meta-synthesis using the concept of social capital. Human Resourc. Health 16, N.PAG. doi: 10.1186/s12960-018-0331-7

Mosby, I., Rotz, S., and Fraser, E. D. G. (2020). Uncertain Harvest: The Future of Food on a Warming Planet. Saskatchewan, Canada: University of Regina Press.

Niemann, L., Hoppe, T., and Coenen, F. (2017). On the benefits of using process indicators in local sustainability monitoring: lessons from a Dutch Municipal Ranking (1999–2014). Environ. Policy Govern. 27, 28–44. doi: 10.1002/eet.1733

Rizzi, F., Annunziata, E., Contini, M., and Frey, M. (2020). On the effect of exposure to information and self-benefit appeals on consumer's intention to perform pro-environmental behaviours: a focus on energy conservation behaviours. J. Cleaner Prod. 270, 122039. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122039

Spiker, M. L., Knoblock-Hahn, A., Brown, K., Giddens, J., Hege, A. S., and Sauer, K. (2020). Cultivating sustainable, resilient, and healthy food and water systems: a nutrition-focused framework for action. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 120, 1057–67. doi: 10.1016/jand.2020.02.018

Velasco, I., and Harder, M. K. (2014). From attitude change to behaviour change: institutional mediators of education for sustainable development effectiveness. Sustainability 6, 6553–6575. doi: 10.3390/su6106553

Keywords: sustainable food system, dietetics, practice, behavior change, institutional change, institutional influence

Citation: Callaghan EG, Powell R and Carlsson L (2022) Assessing Institutional Support From Dietetics Associations Toward Integration of Sustainable Food Concepts in Dietetics Practice. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 6:853564. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2022.853564

Received: 12 January 2022; Accepted: 24 February 2022;

Published: 01 June 2022.

Edited by:

Renata Puppin Zandonadi, University of Brazilia, BrazilReviewed by:

Larissa Seabra, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, BrazilLorena Angela Filip, Iuliu Haţieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Romania

Copyright © 2022 Callaghan, Powell and Carlsson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Edith G. Callaghan, ZWRpdGguY2FsbGFnaGFuQGFjYWRpYXUuY2E=

Edith G. Callaghan

Edith G. Callaghan Rachael Powell2

Rachael Powell2