- Food Systems and Society, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR, United States

Current crises in the food system have amplified and illuminated the need for urgent social change to increase equity and survivability. Global crises such as climate change, environmental degradation, and pandemics increasingly disrupt everyday lives and limit possibilities in the food system. However, the prevalence of these crises has not yet engendered commensurate rethinking on how to address these increasingly evident and desperate social problems. Food and food systems are at the core of survival and food systems issues are deeply intertwined with and inextricable from the structures and operating principles of society itself. Effective and equitable change requires new ways of thinking, ways that are different than those that led to the problems in the first place. This requires identifying, conceptualizing, and addressing social problems through critical inquiry that places social justice at the center in order to render visible and explicit the social injustices in problem causes and consequences, as well as transformative pathways toward social justice. One of the most important domains for this work is that of higher education, an arena in which crucial conceptual thinking can be supported. In this brief article we review why critical pedagogy should be a priority in higher education; discuss critical pedagogy for food systems equity; and illustrate how we apply critical pedagogy in the Food Systems and Society online Master of Science program at Oregon Health & Science University.

Introduction

A crucial and appropriate location for conceptual thinking about social problems and their social-justice-based solutions is higher education, where intellectual work can take place free of daily exigencies of survival. Non-profits can struggle to create the necessary time and space for critical inquiry, given their funding pressures and foci of advocacy and direct action. Private enterprise focuses on profit generation rather than equity. While higher education is the appropriate institution for pedagogical approaches grounded in critical inquiry, it is time-consuming and often not prioritized in the interest of expedience and more instrumental values. Particularly in their neoliberal incarnations and given reductions of public funding, many universities face the same sorts of pressures as do non-profits and private enterprises. Institutions and programs of all sizes may struggle for financial support and often focus on research and education that generates specific pecuniary value for the institutions themselves and for their graduates. Accordingly, universities increasingly tend to push toward instrumental career-focused skill building; valorize research that can be commercialized; increase reliance on contingent faculty; and redefine students as customers purchasing private goods. While these trends are not new, the priorities they represent have been reinforced under neoliberalism and increasingly take precedence over critically-oriented education (see, for example, Saunders, 2010; Giroux, 2014). This is put quite starkly by Giroux (2010, p. 186), who opines that higher education has abandoned the common good and “has become an institution that in its drive to become a primary accomplice to corporate values and power makes social problems both irrelevant and invisible.” Consequently, there is little room for addressing social justice, conceptual thinking, critical inquiry, or reflection.

Nonetheless, it is the role and, indeed, responsibility of public education and research institutions to articulate problems and solutions that are in the public interest, that is, to address systemic inequity. This is closely connected to developing capacity for critical thinking, high-level literacy, and discernment—foundations of “real” democracy. For Giroux (2010, p. 188) “higher education may be one of the few public spheres left where knowledge, value, and learning offer a glimpse of the promise education for nurturing critical hope and a substantive democracy.” Realizing this promise requires pedagogical approaches that are congruent with it. Drawing on Freire (2005), Giroux explains that these approaches must provide “the knowledge, skills, and social relations that enable students to expand the possibilities of what it means to be critical citizens” so they can effectively participate in a “substantive democracy” (Giroux, 2010, p. 192). In the context of food systems education, Classens and Sytsma (2020) argue that post-secondary institutions have a responsibility to increase food literacy in order to address food insecurity and unsustainable social and ecological outcomes in the food system. We suggest that this responsibility extends beyond food-system-focused literacy and practices and to critical conceptual thinking and inquiry about social structures and systems that enable and constrain social justice. This involves a critical pedagogy that is based on clear problem definition, appropriate epistemologies, and relevant conceptual frameworks that center social justice.

Foundations of critical pedagogy for social justice in food systems and society

Our first point is an ontological one that has to do with the category of, “food system.” While problems may be evident in the food system, their causes and solutions transcend the boundaries of the food system per se. They are inextricably connected to the social world through which they were created, persist, and can be solved. Problems such as poverty and resource exploitation are not merely outcomes or contextual factors of food systems, but are integral to dominant food systems and society's operating principles. That is, to address problems in the food system, the unit of analysis must shift from the food system to the historical and contemporary social relations that constitute, structure, and condition the society in which food systems are embedded. Critical ontologies of food systems must include the social relations and systems that construct and condition them. For example, Yamashita and Robinson (2016, p. 270) emphasize the importance of student understanding of “the larger sociopolitical contexts that shape food systems” in developing critical food literacy. This can be applied to the framework of food-system localization and local food systems initiatives.

There is no atomistic “local.” We can only comprehend local experiences and social relations when they are contextualized within global systems. As O'Connor (1998) points out, localities are always constructed in relation to other localities and the global economy. While people experience inequity individually and locally, it is rarely produced locally. In relation to food-systems pedagogy, Meek and Tarlau (2016) suggest the role of food systems education “should be a dialectical process of analyzing the reality of the local food system, linking this local reality to national and international structures that have coproduced this local reality, and helping students come up with creative solutions to transform these realities” (134). For working toward social justice, this involves pedagogical approaches that make visible and clearly conceptualize social structures, contexts, and problems relevant to food system equity. Pedagogy thus becomes critical pedagogy as it seeks to cultivate student capacities as “critical agents who actively question and negotiate the relationships between theory and practice, critical analysis and common sense, and learning and social change” (Giroux, 2010; p. 193). Critical pedagogy is based in praxis and critical inquiry.

Praxis structures critical pedagogy by specifying the correspondence among learning, action, and reflection. Praxis, according to Freire (2005, p. 51) is “reflection and action upon the world in order to transform it.” Reflection includes developing understanding and knowledge that leads to individual and collective action; that action makes the world we live in and its history. By focusing on praxis-informed (“problem-posing”) education, “people develop their power to perceive critically the way they exist in the world with which and in which they find themselves; they come to see the world not as a static reality, but as a reality in process, in transformation” (Freire, 2005, p. 83, italics in original). Praxis is the postulate that people can understand the world and transform it through cycles of learning, action, and reflection; a corollary is that that in order to transform the world, people first need to understand it. While for Freire, thinking is a form of action, in social-justice work there is often a perceived distinction between thinking and action. Mitchell reminds us that this is a false divide, highlighting the intellectual work essential to social-justice activism (Mitchell, 2008). As Musolf (2017, p. 12) points out, we first have to think our way out of oppression before we can fight a way out of it. Consequently, pedagogy focused on understanding and addressing social injustice through the epistemological approach of critical inquiry is foundational to food-system transformation.

Critical inquiry is crucial for enhancing our ability to perceive problems, causes, and remedies relevant to social justice in food systems and society. This requires a departure from or addition to the more familiar and often-used positivist, post-positivist, and constructivist epistemologies employed in food-systems research and education. Critical inquiry directly addresses oppression and privilege in the struggle for social justice, using knowledge to liberate and improve the human condition (Lincoln et al., 2018). While methodological approaches of critical inquiry vary, it has consistent purposes and applications, including developing alternative problem definitions, uncovering assumptions and ideologies, and revealing areas for strategic intervention for socially-just change (Denzin, 2015). Understanding and addressing oppression through critical inquiry begins with specifying and identifying the concepts of social problems and social justice.

Social problems and social justice

A second ontological point is that we cannot address problems unless we first articulate, specify, and valorize their existence. For working toward social justice, the concept of social problem is crucial. A social problem is one that has social consequences and social causes, and consequently, social remedies (Alessio, 2011). Most people concerned about social justice in the food system identify social problems such as food insecurity, environmental degradation, and poverty. We can and do produce horrifying lists of the negative and unjust consequences in the food system. To understand why a social problem exists, though, these harmful consequences must be contextualized alongside their associated beneficial consequences. Often, the food system is framed as “failing” or “broken” (see, for example, Béné et al., 2019 review of narratives defining food system problems and solutions). But clearly, the food system is not failing for everyone. Oppression and privilege are inverse correlates.

The social systems and social relations in which the food system is embedded impoverish some while enriching others and threatening the resources upon which we all depend. Identifying and understanding who is being harmed and who is benefiting in current configurations of social relations in the food system is therefore essential for transforming the food system toward social justice. The food system has been built on the violences of dispossession, enslavement, exploitation, racism and patriarchy and the ideologies that legitimize these practices. Some frame these conditions in terms of maldistribution of risk and responsibility. Bowness et al. (2020) describe this as organized irresponsibility. They point out that powerful players in our food system create, benefit from, and escape responsibility for systemic risks that show up throughout the globe in the form of pesticide poisoning, food insecurity, land destruction and dispossession, income inequality, and dangerous working conditions, among others. Understanding these kinds of food system issues as socially-produced consequences of social problems requires us to ask about winners and losers in food systems and society, the causes of these imbalances, and what can be done to address them. This approach requires conceptualizing and defining what we mean by social justice.

While the concept social problem structures thinking about the harms and benefits of social problems evident in the food system, the concept of social justice provides a normative basis from which to articulate the forms of injustice present in a problem, who is affected by them, and frameworks for socially-just solutions. In critical scholarship, “conceptions of the good” need to be explicitly identified, distinguishing conditions and norms that enable or, conversely, repress flourishing and the common good (Sayer, 2009). Otherwise, even when social justice is identified as an objective of a framework or intervention, unless it is clearly defined, it may be too vague to animate effective action. For example, in their review of social justice definitions in urban food initiatives in the European Union, Smaal et al. (2021) found that social justice definitions employed tended to be implicit and partial, with unspecified criteria to indicate progress. The consequence, they say, is that inadequate engagement with social justice limits public consciousness and stifles action on social justice issues in the food system such as malnutrition and poverty. The vocabularies and frameworks we employ in food systems can be ineffectual or even inadvertently reinscribe inequity if they do not clearly define social justice or address causes of injustice.

Causes, remedies, and frameworks

Problems, causes, and remedies are a set and are implied in food-system frameworks for transformation. Causes are what constrain social justice and remedies are what enable social justice. Social problems always have social causes. As discussed, the food system is socially produced and organized. A corollary is that social inequity is also produced, both historically and contemporarily. People, through ideologies, policies, and practices, create positive and negative consequences in food systems and society. Remedies for social-justice problems therefore require investigation of the causes of these problems. Often, however, food system frameworks can exclude or obscure social causes of social problems.

Silence on causation can lead to food-system frameworks for solutions that are meant to include social justice, but do not sufficiently address it. These frameworks include sustainability, resilience, agroecology, and food sovereignty. For example, sustainability is a static term that means keeping things the same, no matter how much many of us have tried to contort and infuse social justice into the term (see, for example, Allen, 2004, 2008). Resilience is equally limiting. While resilience can mean to rebound, rebounding from what is left an open question and it can equally mean to avoid. According to Leary (2019, p. 149) the term was coined by an environmental scientist to measure the persistence of systems in conditions of disturbance to still “maintain the same relationships between populations.” It is misplaced and often dangerous to impute biophysical observations to social systems because what we are trying to explain and achieve are different. Applications of resilience frameworks have often failed to address the question “resilient for whom?” or the social dynamics internal to its location of focus (Brown, 2014; p. 109). Moreover, resilience's goal is a stable state, but advocates of resilience addressing social systems are often agnostic on what the “state” should look like, avoiding complex social and normative factors such as power, politics, and patriarchy (see Cote and Nightingale, 2012). In a review of resilience research on food systems, Hedberg (2021, p. 5) finds, “Rights and social justice are central to food system resilience, yet meaningful engagement with rights is not a common feature of existing scholarship applications.” Yet it is those very factors that have created inequality and must be addressed to reduce it. Social relations and collective goals for them, including barriers to and pathways toward social justice, must be visible and central in food system frameworks if they are to be adequately addressed.

Similarly, conceptual frameworks such as agroecology, food sovereignty, local food systems, community, and, ironically, food justice, are often under-theorized or under-specified in their relationship to social justice in food systems and society. For example, Meek and Tarlau (2016) and Meek et al. (2019) emphasize food sovereignty as a guiding conceptual framework for critical food systems education. In a review of food-sovereignty-focused educational programs, Meek et al. (2019, p. 612) note that food sovereignty “means very different things in disparate geographic contexts, making it difficult to provide a universal definition of the concept. Despite this ambiguity, scholars agree that food sovereignty is a rights-based approach in which farmers, other producers, and communities are in control of their food system.” When particular communities wrest control of the food system from extra-local institutions and actors, it could lead to more socially just outcomes, but this cannot be assumed. We must be cognizant of which problems a framework is likely to address and which it is likely to exclude. For example, does the framework address power imbalances and divergent priorities related to class, race-ethnicity, or gender? Anderson et al. (2019, p. 527) point out, for example, that while food sovereignty is theoretically an emancipatory approach, “quiet food sovereignty” may do nothing to “reveal and address the underlying systems of oppression that are left intact and unquestioned.” Our perspective is that these issues must be identified and addressed before, not after, we adopt and promote frameworks for food-system transformation. That is, let us not put the cart before the horse. Before we identify solutions-oriented frameworks we need to understand the problems we are trying to solve, their causes, their context, and their scope.

To summarize, critical pedagogy for food-system transformation requires relevant ontological, epistemological, and conceptual foundations. Praxis articulates the interrelated roles of learning, understanding, and reflection in achieving transformation toward social justice. Critical inquiry specifies an epistemological approach for learning and understanding that focuses its purposes on confronting oppression and increasing social justice. Applying the concept of social problem through critical inquiry leads to clear identification of social problem causes, harms, benefits, and potential solutions. A clear definition of social justice orients the critical inquirer to the specific injustices present in the problem and provides a pathway for transformation. The next section briefly reviews how these concepts are operationalized in the Food Systems and Society (FSS) graduate program at Oregon Health & Sciences University (OHSU).

Operationalizing critical pedagogy in the food systems and society program

The purpose of the FSS program is to explore and expand critical intellectual capacity for addressing social justice within food systems and society. A foundational ontological position of the FSS program is that food systems are not separate from and cannot be separated from society as a whole. Hence, the name of the program and degree is Food Systems and Society. Students who enroll in the program are often initially focused on food-specific frameworks gleaned from food-systems literature discussed above, such as localization, community participation, resilience, sustainability, or food sovereignty. Through the FSS curriculum students move beyond food-system-specific frameworks, increasing their capacity to identify and articulate social problems related to social justice, critically inquire about the root causes of those problems, and explore possible solutions.

An important element of seeing the food system through society, and central to developing critical intellectual agency, is recognizing the possibility for social change for social justice. Students learn that the issues we face in the food system have been created by people and hence can be transformed by people. This grounding animates students and encourages active participation in both inquiry and transformative action for social justice. While students can sometimes become overwhelmed by the prevalence and scope of social-justice problems in society, we focus on Harvey's (2000) concepts of insurgent architects, theaters of action, collectivities, and the inevitability of living in the world as it exists while simultaneously working to change it. These notions are infused throughout the FSS curriculum so that students understand that they have power, but that they are not individually responsible for all social-justice work. Many others stand beside them.

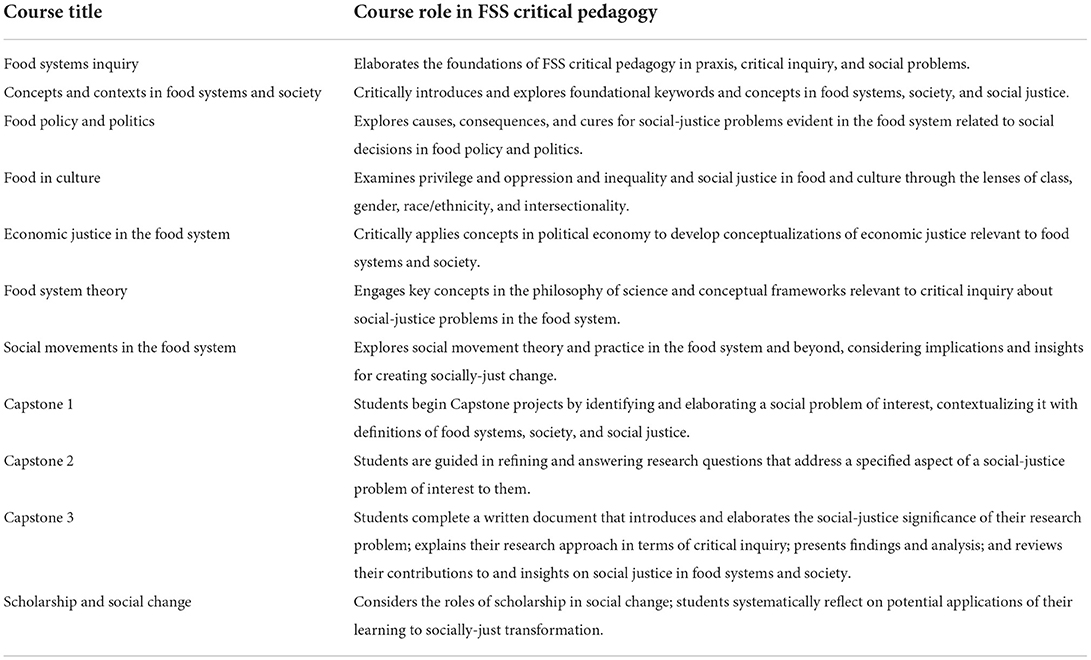

To operationalize this approach, students engage collaboratively throughout the curriculum with the concepts of praxis, critical inquiry, social problem, and social justice and their applications in food systems. Table 1 provides an overview of the ontological, epistemological, and pedagogical contributions of key concepts in the FSS program. Each concept suggests the next: praxis compels critical inquiry to systematically increase understanding; critical inquiry requires a conceptual framework like social problem to structure its focus on addressing problems to improve the human condition; and social problem requires a normative conceptual framework such as social justice to guide analysis and evaluation of its causes, consequences, and cures. Conceptual frameworks for praxis and critical inquiry are established early in the FSS program to make visible and elaborate the overall pedagogical approach taken.

Table 1. Ontological, epistemological, and pedagogical foundations of the food systems and society graduate program.

The concept of praxis orients students to the idea that intellectual understanding and reflection are as fundamental to socially just change as participatory action. The concept affirms and valorizes their intellectual labor and makes clear that they are an active participant and transformative agent in their education and in the world. In line with critical pedagogy, the concept illustrates the intent and operation of the FSS program to develop critical agents, capable of asking and answering their own questions in order to identify and address pressing social-justice problems. Enacting praxis, reflective assignments included in all FSS courses encourage students to systematically reflect on their evolving understanding of food systems and society and to specifically consider their learning's relevance to socially-just change. This practice, accomplished through end-of-course assignments delivered through persistent and interactive documentation methods, enhances students' critical intellectual capacity and confidence in their ability to create meaningful change.

While elaboration of the concept praxis demonstrates to students the importance of new understanding in socially-just change, critical inquiry helps them better understand the kinds of problems and questions they can address to realize this goal. Students are acquainted with contrasting research paradigms early in the program. These are not positioned as “right” or “wrong,” but are explored in terms of variation in their ontologies, epistemologies, methodologies, and their intent or capacity for identifying and addressing different kinds of research problems. Critical inquiry is explained as relevant to understand, illuminate, or transform social processes, institutions, and relationships toward greater equity in power, knowledge, and resource distribution. Engaging with academic scholarship, students explore different theoretical, conceptual, and analytical approaches to research relevant to social justice in food systems and society.

Clear problem-definition is a precondition for effective social-justice-related social-problem solving, as is applying clear analytical criteria for social justice, and identifying points of intervention. Early in the program, students explore conceptual frameworks related to social justice and consider contrasting definitions, framings, and foci. In conceptualizing social justice in the FSS program we consider oppression and privilege starting with the categories and axes of gender, class, race, and their intersections. These inter-related categories construct and reflect ideologies and practices of inequalities that structure people's lives and life chances throughout the world (see, for example, Collins, 2013). Based on these initial categories, students then articulate their own definitions and criteria for social justice, ensuring that they “know it when they see it” and can apply it to defining problems and solutions in their own work. In this way, they avoid relying on vague or surrogate conceptualizations of social justice or underspecified food-system frameworks and can focus not only on inequitable “outcomes,” but also on their causes. With a definition of social justice in hand, students are able to identify and explain the aspects of social problems in the food system that need to be addressed in order to create meaningful transformation toward social justice. Without a definition of social justice, it is impossible to develop goals for food system equity, illustrating the fundamental importance of conceptual thinking in critical pedagogies.

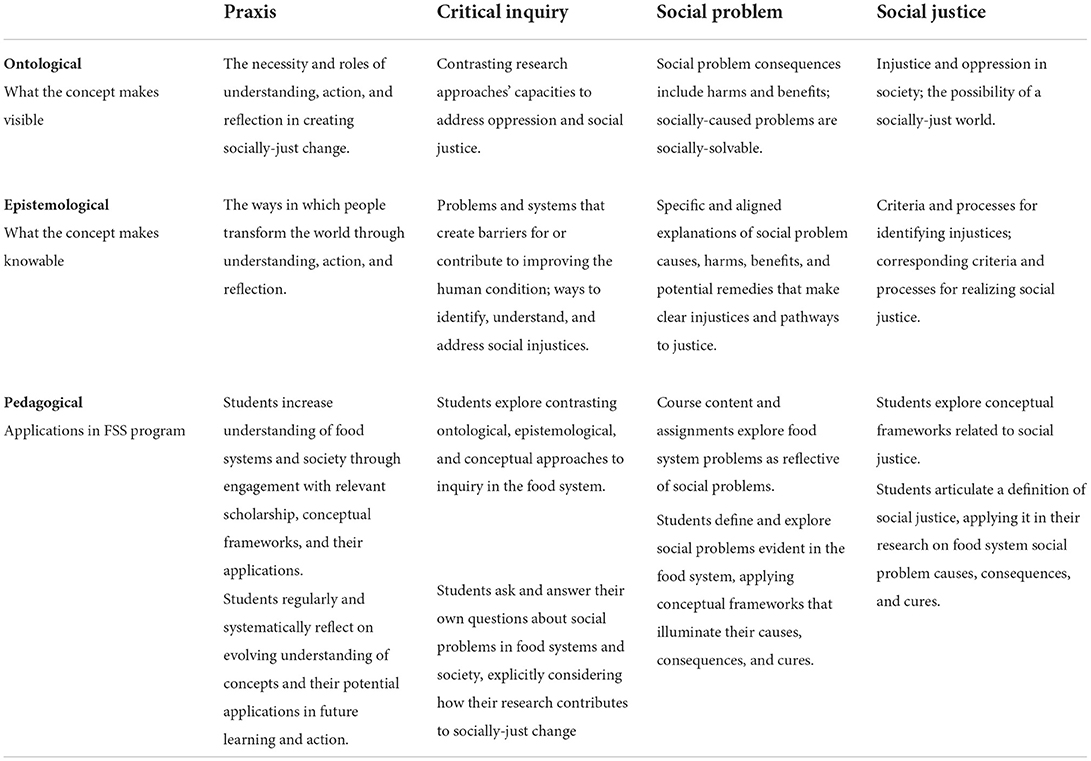

Critical, conceptual engagement with the social justice aspects of social problems in the food system continues throughout the program, and culminates in student research that emphasizes clear conceptual thinking over and above data collection or internships. The FSS curriculum contains 50 credits of coursework, including Foundation, Capstone, and Practicum course types. Foundation courses explore key concepts in food systems and society; Capstone courses guide students through research on social-justice problems; and Practicum courses support collaboration and scholarly capacities. Table 2 lists Foundation and Capstone courses and illustrates some of the course content.

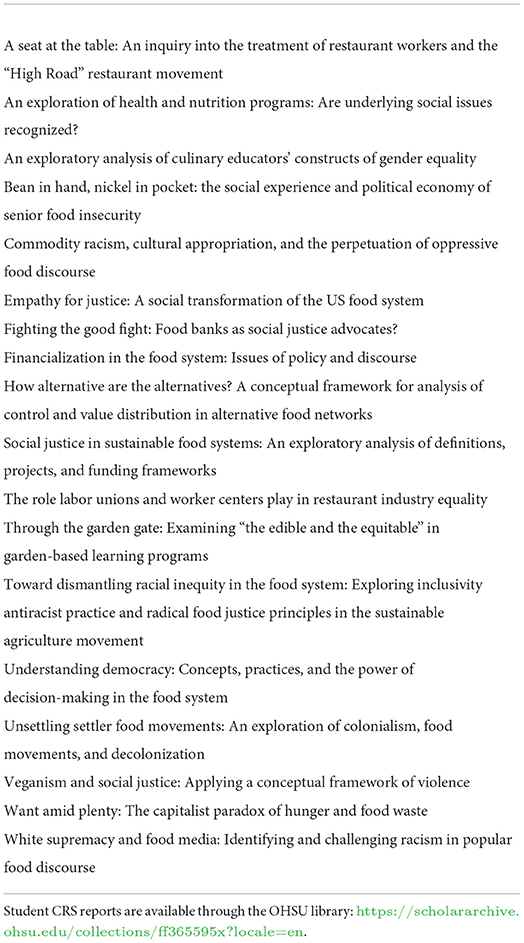

In their FSS Capstone research, students synthesize and apply concepts to ask and answer their own questions about social-justice problems in food systems and society. Students focus on social justice problems that are of particular interest to them, based on their experiences and positionality. In their research, students evidence a social problem, examining its causes, consequences in terms of harms and benefits, and potential remedies. Students engage in basic definitional work of all key concepts in their research, building their own conceptual frameworks and corresponding definitions and analytical criteria for use in critical inquiry. The concepts of praxis, critical inquiry, social problems, and social justice move students toward specific appraisals of problems, their causes, and proposals for solutions to inequities in food systems and society. Clarity in problem identification and conceptualization is essential for developing fundamental critical intellectual capacity that can support social change. Students explicitly consider and reflect upon how their research and new understanding contributes to socially-just change. Each student's research is summarized in a written Capstone Research Synthesis (CRS) report, which is a requirement for graduation. The diversity of social problems, conceptual frameworks, and approaches in student research is illustrated in the sample of CRS titles in Table 3.

Table 3. Selected Capstone Research Synthesis (CRS) titles from food systems and society program graduates.

While participatory action research and community engagement is sometimes proposed as essential for social-justice work, these activities are understood as possible but not essential pathways in the FSS program. Students develop a sense of efficacy in doing their part to transform the world in the ways that are most relevant to them, always with praxis, social justice, and critical inquiry at the heart of their work. For transformative scholarship, Farias et al. (2017) explain why participatory practices must be combined with critical understanding of large-scale social conditions; without this understanding, interventions can ignore or reproduce injustice. In articulating specific social causes and consequences, social systems that reproduce inequities become visible and changeable. This is because it is first important to understand the principles of social problems, causes, and remedies and because communities and groups may and often do contain axes of oppression themselves. By first developing critical intellectual capacity, students will be better able to participate in these forms of transformative work. Thus, critical inquiry is essential for advancing social justice independent of participatory action or community engagement and it is essential for engaging in these practices as well. Through their work in the FSS program, students develop understandings of oppressive and liberatory social systems and their roles in them; they are changed and, in turn, can and do change the world.

Conclusion

The question posed in this special issue is: What pedagogies and principles are best suited to help students connect critical reflection on food systems with transformative action? Our answer is that we need vocabularies and frameworks that foreground and directly address social-justice problems, their causes, and potential remedies. There are clear winners and losers in the food system, and “outcomes” in food system analyses must focus not only on harms but also beneficiaries. Engagement with food systems must disrupt the inequitable social systems foundational to the organized irresponsibility in the food system and the risks to which it exposes us. This means resisting, reforming, and transforming social systems so they do not subsist on oppression and exploitation. The conceptual framework of food systems, absent a focus on society and its attendant inequities and their causes does not take us very far toward transformation either of the food system nor the social systems in which it is embedded.

We tend to use vocabularies and frameworks that are in academic and popular commerce and for which funding is available, often because they have transitioned from emergent to dominant discourses (see Williams, 1977 for a discussion of residual, dominant, and emergent discourses). Instead of using terms like sustainable and resilient in framing food systems, we ought to ask which systems we want to sustain and which we want to break down. Our selection of frameworks and vocabularies either oppose or reproduce historical and contemporary inequity. If the goal is to address injustice in the food system, we suggest food system scholars and practitioners shift the analytical focus from “food systems” to the systems of oppression that drive the food system and use vocabularies that illuminate problems of inequity. Creating socially just food systems requires ontological, epistemological, and pedagogical approaches that center social justice within the context of society and social relations.

Public higher education institutions should prioritize critical inquiry to address inequity in social systems. This requires a reorientation of purpose and resource allocation, engaging deeply with students who will play important and varied roles in transforming the food system in the direction of greater equity. Our hope is that universities increase emphasis on critical inquiry and support faculty and students in this endeavor. Higher education should prioritize the careful conceptual thinking foundational to identifying social equity problems and their causes and developing solutions for transformation. The world has never been in more urgent need of critical pedagogy and critical inquiry in food systems and society. Higher education must step up to the plate or accept its responsibility for accelerating social injustice in food systems and society.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

Both authors listed have made an equal, substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to students and alumni of the graduate program in Food Systems and Society, in which they courageously engage the critical intellectual labor essential for creating a more socially just food system and society. Their contributions and commitment inspire us. We appreciate the reviewers whose comments helped to sharpen the article. We also acknowledge Oregon Health & Science University for providing a home for our graduate program devoted to understanding the causes, consequences, and cures for persistent social justice problems.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alessio, J. C. (2011). “The systematic study of social problems.” in Social Problems and Inequality: Social Responsibility through Progressive Sociology, (Farnham: Taylor and Francis Group), 1–17.

Allen, P. (2004). Together at the Table: Sustainability and Sustenance in the American Agrifood System. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Allen, P. (2008). Mining for Justice in the Food System: Perceptions, Practices, and Possibilities. Agric. Human Values 25, 157–161. doi: 10.1007/s10460-008-9120-6

Anderson, C.R., Binimelis, R., Pimbert, M. P., and Rivera-Ferre, M. G. (2019). Introduction to the symposium on critical adult education in food movements: learning for transformation in and beyond food movements - the why, where, how and the what next? Agric. Human Values 36, 521–529. doi: 10.1007/s10460-019-09941-2

Béné, C. P, Oosterveer, L., Lamotte, I. D., Brouwer, S., de Haan, S. D., Prager, E. F., et al. (2019). When food systems meet sustainability–current narratives and implications for actions. World Dev. 113, 116–130. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.08.011

Bowness, E., James, D., Desmarais, A. A., McIntyre, A., Robin, T., Dring, C., et al. (2020). Risk And responsibility in the corporate food regime: research pathways beyond the COVID-19 crisis. Stud. Polit. Econ. 101, 245–263. doi: 10.1080/07078552.2020.1849986

Brown, K. (2014). Global environmental change I: a social turn for resilience? Prog. Human Geography 38, 107–117. doi: 10.1177/0309132513498837

Classens, M., and Sytsma, E. (2020). Student food literacy, critical food systems pedagogy, and the responsibility of postsecondary institutions. Can. Food Stud. 7, 8–19. doi: 10.15353/cfs-rcea.v7i1.370

Collins, P. H. (2013). “Toward a new vision: race, class and gender.” in Readings for Diversity and Social Justice, eds, M. Adams, W. J. Blumenfeld, C. Castañeda, H. W. Hackman, M. L. Peters, and X. Zúñiga, (New York, NY: Routledge), 606–611.

Cote, M., and Nightingale, A. J. (2012). Resilience Thinking Meets Social theory: Situating Social Change in Socio-ecological Systems (ses) Research. Prog. Human Geography 36, 475–489. doi: 10.1177/0309132511425708

Denzin, N. K. (2015). “What is critical qualitative inquiry?” in Critical Qualitative Inquiry: Foundations and Futures. eds G. S. Cannella, M. Salazar Pérez, and P. A. Pasque, (Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press), 31–50.

Farias, L., Rudman, D. L., Magalhaes, L., and Gastaldo, D. (2017). Reclaiming the potential of transformative scholarship to enable social justice. Int. J. Qual. Methods 16, 1–10. doi: 10.1177/1609406917714161

Giroux, H.A. (2010). Bare Pedagogy and the Scourge of Neoliberalism: Rethinking Higher Education as a Democratic Public Sphere. Educ. Forum 74, 184–196. doi: 10.1080/00131725.2010.483897

Harvey, D. (2000). “The insurgent architect at work.” in Spaces of Hope, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press), 233–255

Hedberg, R.C. (2021). An instrumental-reflexive approach to assessing and building food system resilience. Geography Compass 15, 1–15. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12581

Lincoln, Y., Lynham, S. A., and Guba, E. G. (2018). “Paradigmatic Controversies, Contradictions, and Emerging Confluences, Revisited.” in The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, eds N. Denzin and Y. Lincoln, (London: Sage), 108–150

Meek, D., Bradley, K., Ferguson, B., Hoey, L., Morales, H., Rosset, P., et al. (2019). Food sovereignty education across the americas: multiple origins, converging movements. Agric. Human Values 36, 611–626. doi: 10.1007/s10460-017-9780-1

Meek, D., and Tarlau, R. (2016). Critical Food Systems Education (CFSE): educating for food sovereignty. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Systems 40, 237–260. doi: 10.1080/21683565.2015.1130764

Mitchell, D. (2008). “Confessions of a desk-bound radical.” in Practising Public Scholarship: Experiences and Possibilities Beyond the Academy, eds K. Mitchell. (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell), 99–105.

Musolf, G. R. (2017). “Oppression and resistance: a structure-and-agency perspective.” in Oppression and Resistance: Structure, Agency, Transformation, eds G. R. Musolf and N. K. Denzin, (Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited), 1–18.

O'Connor, J. R. (1998). Natural Causes: Essays in Ecological Marxism, Democracy and Ecology. New York, NY; London: Guilford Publications.

Saunders, D.B. (2010). Neoliberal ideology and public higher education in the United States. J. Crit. Educ. Policy Stud. 8, 41–77. Available online at: http://www.jceps.com/archives/626

Sayer, A. (2009). Who's Afraid of Critical Social Science? Curr. Sociol. 57, 767–786. doi: 10.1177/0011392109342205

Smaal, S. A. L., Dessein, J, Wind, B. J., and Rogge, E. (2021). Social justice-oriented narratives in European urban food strategies: Bringing forward redistribution, recognition and representation. Agric. Human Values 38, 709–727. doi: 10.1007/s10460-020-10179-6

Williams, R. H. (1977). “Dominant, Residual, and Emergent.” in Marxism and Literature. (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 121–127.

Keywords: critical inquiry, food systems, inequity, pedagogy, praxis, social justice

Citation: Allen P and Gillon S (2022) Critical pedagogy for food systems transformation: Identifying and addressing social-justice problems in food systems and society. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 6:847059. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2022.847059

Received: 01 January 2022; Accepted: 27 October 2022;

Published: 18 November 2022.

Edited by:

Molly D. Anderson, Middlebury College, United StatesReviewed by:

Will Valley, University of British Columbia, CanadaDavid Meek, University of Oregon, United States

Copyright © 2022 Allen and Gillon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Patricia Allen, YWxsZW5wYXRAb2hzdS5lZHU=

Patricia Allen

Patricia Allen Sean Gillon

Sean Gillon