94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Food Syst., 14 April 2022

Sec. Urban Agriculture

Volume 6 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.844170

This article is part of the Research TopicBuilding Sustainable City Region Food Systems to Increase Resilience and Cope with CrisesView all 11 articles

The concept of the city-region food system is gaining attention due to the need to improve food availability, quality and environmental benefits, for example through sustainable agri-food strategies. The COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced the importance of coherent and inclusive food governance, especially regarding food resilience, vulnerability and justice. Given that evidence from good practices is relatively sparse, it is important to better understand the role of different types of cities, regions and household characteristics. The paper's aim is to describe, analyze and attempt to explain (sub-national) regional variations of household food behavior before and during the first wave of COVID-19 in 2020 using a city-region food system perspective. Informed by the literature, comprehensive survey data from 12 countries across Europe is used to describe the pre-pandemic landscape of different household food behaviors across comparable regional types. We examine how a specific economic and social shock can disrupt this behavior and the implications for city-region food systems and policies. Conclusions include the huge disruptions imposed on income-weak households and that the small city scale is the most resilient. Proposals are made that can strengthen European city-region food system resilience and sustainability, especially given that future shocks are highly likely.

Given that about 75% of the EU's population now resides in urban areas (Macrotrends, 2021), city-region food systems play a crucial role in meeting the challenges besetting the European food sector. Although integrated city-region food system policies across most of Europe are still scarcely developed, with actors operating outside of local production and consumption spheres and at higher governance levels (Sonnino et al., 2019), the COVID-19 crisis has revealed a need for more local approaches to food governance (Blay-Palmer et al., 2021; Morley and Morgan, 2021; Zollet et al., 2021) and for taking into account the socio-economic determinants of food behaviors, in order to build a more equitable food system (Cohen and Ilieva, 2021).

On the other hand, even though inequalities between population groups within cities and their hinterlands, as well as growing differences between cities themselves (Nijman and Wei, 2020) also related to food provisioning (Keeble et al., 2021), existed before COVID-19, the system shock has further exposed and exacerbated them (Zollet et al., 2021). It has moved actors to take actions starting from a perspective much more grounded in local food systems and the agency of different actors (Lever, 2020; Schoen et al., 2021; Vittuari et al., 2021). Moreover, the pandemic has stimulated a wealth of literature concerned with its effects on food systems and consumer behavior.

The concept of a city-region food system as a system of “actors, processes and relationships that are involved in food production, processing, distribution and consumption in a given city region” (FAO, 2016) provides a definition from a socio-economic perspective. This enables their exploration through the lens of the Eurostat classification of territorial typologies, which relies on the assumption that most economic, social and environmental situations and developments have a specific territorial connotation (Eurostat European Commission Statistical Office of the European Union, 2018).

The aim of this paper is to describe, analyze and attempt to explain (sub-national) regional variations of household food behavior before and during the first wave of COVID-19 using a city-region food system perspective. Informed by the literature, comprehensive survey data from 12 countries across Europe is used to describe the pre-pandemic landscape of diverse household food behaviors across comparable regional types, and then how the pandemic has disrupted this behavior and the implications this has for city-region food systems and policies.

The paper examines the issues described above from a regional perspective through the following structure. First, Section Introduction presents the aims of the paper, outlines the context, provides a literature review and proposes a conceptual framework. Section Materials and Methods describes how the survey data was designed, collected and analyzed, the basic definitions and approaches used and the representativeness of the samples. Section Results presents the results of the analysis around four main topics: (1) COVID-19 restrictions on household income and health; (2) Local food environments: where households shop and eating outside the home; (3) Social context: the amount of food, money and stocking up, food preparation at home and food vulnerability; and (4) Food consumption and diet: types of food consumed, special dietary needs and environmental issues. Finally, Section Discussion links these four topics together with existing literature and state-of-the-art knowledge in the context of the conceptual framework to suggest likely explanations of the results obtained. Focus is on the key responses and adaptations needed to external shocks taking account of ongoing trends toward the re-regionalization of European city-region food systems, how they can be made more resilient and sustainable, as well as the role of spatially heterogeneous food policy and governance arrangements within the city-region food system context.

There are numerous recent studies on the policies and governance of food systems especially in a city-region food system context since the outbreak of the pandemic. These include a special issue of the Food Policy journal in August 2021 on “Urban food policies for a sustainable and just future”. In the introductory editorial, Moragues-Faus and Battersby (2021) identify three core perspectives in urban food governance scholarship: a shift toward systemic engagement with food systems; increased engagement with scalar complexity; and a growing focus on relational aspects of urban food governance and policy-making dynamics. Their analysis also points out three key aspects that require further focus for the field to be transformative: a stronger conceptualization of the urban; a clearer definition and articulation of the nature of governance and policy; and a more engaged focus on issues of power and inequities. In the same issue, Cohen and Ilieva (2021) show how policy makers are starting to acknowledge that the food system is multidimensional, that social determinants affect diet-related health outcomes, and the need to move away from focusing food programs and policies narrowly only on food access and nutritional health. Thus, the boundaries of food governance are expanding to include a wider range of issues and domains not previously considered within the purview of food policy, like labor, housing, and education policies.

There is clear evidence that households already experiencing some food poverty were pushed to an even greater extent to a reliance on charity and food banks. Capodistrias et al. (2021) show that, compared to 2019, in 2020 European food banks redistributed a significantly higher amount of food despite numerous social restrictions and other challenges associated with the pandemic. This was made possible by organizational innovations, new strategies and new internal structures in the food banks, as well as the establishment of new types of external network relations with other firms and/or public organizations. In relation to urban food policy governance, Parsons et al. (2021) point to the importance of institutions as policy-structuring forces, the need to rebalance national-local powers and to develop cross-cutting food plans. Clark et al. (2021) emphasize the role of community food infrastructures and the importance of critical middle infrastructures to connect production with consumption and larger markets, thereby building resilience through intermediate markets. The overall thrust of this literature is about the importance of linking urban food policies with other urban policies, new types of place leadership for example through the anchor institutions and middle infrastructures of community-wealth building and “new localism” initiatives (Millard, 2020).

The importance of the sustainability of city-region food systems inevitably turns attention to the topic of short food supply chains (SFSCs), which are associated with extensive good practice evidence related, e.g., to re-connection of food producers with consumers (Grando et al., 2017), social sustainability (Vittersø et al., 2019), or building transparent food supply chains with the fair distribution of power among actors (Kessari et al., 2020). In addition, SFSCs are associated with the production of quality and safe food when consumers buy products from trusted suppliers who are able to guarantee genuine and safe products, not necessarily located nearby (Baldi et al., 2019). Pandemic experience has highlighted the vulnerability of globalized agri-food systems as well as societies in the relatively developed world, to which the research is already responding. Matacena et al. (2021) see this situation as an opportunity to strengthen the sustainability agenda, e.g., by pursuing the Farm to Fork strategy of the EU and thus, enhancing the resilience of regional and local food systems and empowering consumers to make informed food choices. Murphy et al. (2021) mention the importance of local food supply chains for supplementing the global market and ensuring normal product flow during emergencies, whilst Vidal-Mones et al. (2021) propose strengthening independence in the form of support for local and seasonal consumption.

An extremely short food supply chain is represented by home food gardening, which tends to be neglected by most food systems research and policies but remains relatively widespread across European countries and regions as Vávra et al. (2018b) and Jehlička et al. (2021) show. The habit of growing one's own food as well as available land (e.g., home, allotment, weekend home, and community garden) are important elements of sustainable food systems. For example, gardening households in Czechia produce 33% of their own consumed fruit, vegetables and potatoes (Vávra et al., 2018a), whilst 20% of fruit and vegetables consumed by all Czech households is grown at home (Jehlička et al., 2019). This figure includes non-gardening households which receive some food from their food-producing relatives, friends or neighbors. Edmondson et al. (2020) investigated individual crop production in Leicester city, UK, by monitoring production in 80 different self-provision locations through a citizen science project showing that average crop yield increased by 2.3 ± 0.2 kg m2. The authors combined these results with GIS data to upscale their findings across the whole city and found that “total fruit and vegetable production on allotment plots in Leicester was estimated at 1,200 tons of fruit and vegetables and 200 tons of potatoes.”

McEachern et al. (2021) point out that “while existing literature has predominantly focused on larger retail multiples, we suggest more attention be paid to small, independent retailers as they possess a broader, more diffuse spatiality and societal impact than that of the immediate locale. Moreover, their local embeddedness and understanding of the needs of the local customer base provide a key source of potentially sustainable competitive advantage” and thus help underpin both urban and community resilience. Finally, Vittuari et al. (2021) document how the COVID-19 pandemic unveiled the fragility of food sovereignty in cities and confirmed the close connection urban dwellers have with food and suggested how citizens would accept and indeed support a transition toward more localized food production systems. The paper proposes the reconstruction and upscaling of such connections using a “think globally act locally” mind-set, engaging local communities, and making existing and future citizen-led food system initiatives more sustainable to cope with the growing global population.

At the household level, a large amount of literature has already examined the impact of COVID-19 on food systems and consumer behavior. In a survey of households in Denmark, Germany and Slovenia, Janssen et al. (2021) found that between 15 and 42% of households changed their food consumption patterns during the first wave of COVID-19 and that this was related to the closure of physical places to eat outside the home, reduced shopping frequency, individuals' perceived risk of COVID-19, income losses due to the pandemic, and socio-demographic factors. A meta-analysis of COVID-19 induced changes in food habits in Italy, France, Spain, Portugal and Poland indicated the generally negative effect of quarantine on eating habits and physical activity with an increase in food consumption and reductions in physical activity and consequent weight gain (Catucci et al., 2021). Some psychologically oriented studies point out the potential increase of negative psychological aspects during the pandemic, like panic buying, herd mentality, changing discretionary spending, especially during first signs of disaster (Loxton et al., 2020).

Regarding diets, the results of several studies vary across countries, regions and also economic groups of inhabitants. Profeta et al. (2021) show that the pandemic has a significant impact on consumers' eating habits in Germany. The purchase of ready meals and canned food increased, including the consumption of alcohol and confectionery, at the same time as there was a decrease in the purchase of high-quality and more expensive food like vegetables and fruits especially by economically vulnerable groups (income-loss households and with children). This study warns about negative health consequences if the trend continues. In contrast, research conducted in Spain (Rodríguez-Pérez et al., 2020) shows the opposite trend and a move toward Mediterranean diets and thus healthier dietary habits. The authors examine dietary behavior in Spain, including the differences between 3 large regions (north, central, south), and noted that adherence to the Mediterranean diets before and during COVID-19 was significantly influenced by the region, age and education level, being highest in the northern region. Households' responses to COVID-19 can be observed not only in consumption but also in food production. Recent research shows how variable the effect was. On one hand the anti-pandemic travel limitations and gardeners' health concerns have led to lower frequencies of visits to allotments in some cases (Schoen et al., 2021), whilst on the other hand gardens were seen as a safe space, other leisure activities were restricted and food concerns increased too. According to some studies this led to more time spent in the gardens and more people growing their own food (Mullins et al., 2021; Schoen et al., 2021).

Although not directly focused on food systems, there are relevant sources that examine the impact of COVID-19 on cities and regions. The EU's Committee of the Regions 2020 report examined the territorial dimensions of COVID-19 across the EU and showed that, although government responses were largely national, they resulted in very different regional impacts. The socio-economic asymmetry of consequences across Europe, countries, regions and cities is largely shaped by diverse regional characteristics that call for higher levels of place-sensitive policy responses, taking into account a region's economic structure, structural challenges, and social profile. Although much of the analysis is focused on specific regions rather than regional types, the findings show both that, because COVID-19 responses vary so much, the usual urban-rural differentiation does not apply, but that also metropolitan areas have generally been strongly hit but also tend to experience quicker recovery (European Committee of Regions, 2020). Sharifi and Khavarian-Garmsir (2020) report that cities that don't have a diverse economic structure are more vulnerable to COVID-19. For example, in Poland, cities going through trans-industrialism, with hard coal mining, large care centers and shrinking cities, are the most vulnerable ones. Whilst the evidence is mainly on the negative impacts, more positive developments are also seen, for example COVID-19-induced transportation restrictions and border closures have disrupted food supply chains in cities but have in turn provided additional momentum to urban farming movements. It is expected that more attention will be paid to local supply chains in the post-COVID-19 era. There are also successful cases of social innovation and collaboration, such as in Naples where efforts have been made, through volunteering programs, to get people involved in local practices that contribute to meeting local food demands and also strengthen social ties during the pandemic (Cattivelli and Rusciano, 2020).

Although there appear to be few systematic studies on the regional food systems, an important Czech study undertaken before COVID-19 by Spilková (2018) looked at whether alternative food systems (AFN, covering farm markets, street markets, cooperatively owned or solidarity shops, specialist organic food outlets and buying food directly from the producers) attract significantly different consumers in different regions than traditional forms and large-scale outlets. Results showed that consumer choices arise from a mix of lifestyle, socio-economic determinants and contextual factors, that “similar people with similar lifestyles ‘cluster' within the same localities” and there is a need to take account of “‘objective' (areal) variables within a given geographical area and settlement system context (p. 189)”.

To better understand processes and relations within different regional types, it is useful to consider the three stages of the urbanization process and how these can repeat themselves (Aleksandrzak, 2019; Mitchell and Bryant, 2020):

1. Initial urbanization accompanies the shift from an agrarian to an industrial factory-based society and sees growth concentrated in urban cores.

2. This is later followed by a suburbanization stage during which growth occurs beyond the urban core, at the expense of the core's population as new forms of efficient transport allow the better-off to move out of the center to new suburbs.

3. The final counter-urbanization (or de-urbanization) stage sees the growth of smaller cities and towns in nearby areas beyond the built-up suburban ring and is accompanied by population decline in the core and its immediate suburbs.

The cycle can re-start with a re-urbanization stage that sees new growth back in the original urban core, driven by the inward movement of both counter-urbanite and suburbanite populations. Many metropolitan regions, particularly in advanced economies, experienced a counter-urbanization period in the past, for example in the early 1970s. Since then, parts of this cycle have repeated themselves especially in the last 20 years but through somewhat different processes, this time driven by globalization and enabled by digital technologies leading to the counter-urbanization we are currently experiencing. These distinct metropolitan cycles, often reflecting at the regional scale an inverse relationship between population growth and city size, are also charted by Cividino et al. (2020) with metropolitan growth being highly positive before 2000 but declining progressively in the subsequent decades. The 1990s were a transitional period away from a spatially homogeneous demographic regime based on high rates of population growth strictly dependent on city size, to the regime we largely see today grounded on low rates of population growth varying over space. This seems synonymous with Mitchell and Bryant's counter-urbanization phase and the growth of smaller cities.

According to KPMG (2021), COVID-19 has accelerated this move toward the growth of smaller cities through the adoption of online shopping, working from home and online gatherings rather than meeting in person in cities and towns in England. KPMG predict that people are unlikely to return to the old ways of doing things. With fewer people coming into very large cities to work and shop, that leaves a big space in areas that were once characterized by bustling shops and offices. Those places that are most at risk are those that have little else to attract locals and visitors from further afield. In these cities there has been a loss of commuter flow from over a tenth to under a third of commuter footfall seen pre-COVID. Apart from the largest, mainly capital, cities like London, the authors contend that it is unlikely there will be a return to old commuting habits in most very large cities, with a significant proportion of those able to work from home doing so for at least part of the week or shifting to working closer to home in smaller cities. This is likely to lead to significant reductions in office space in large cities and a collapse in their central retail areas.

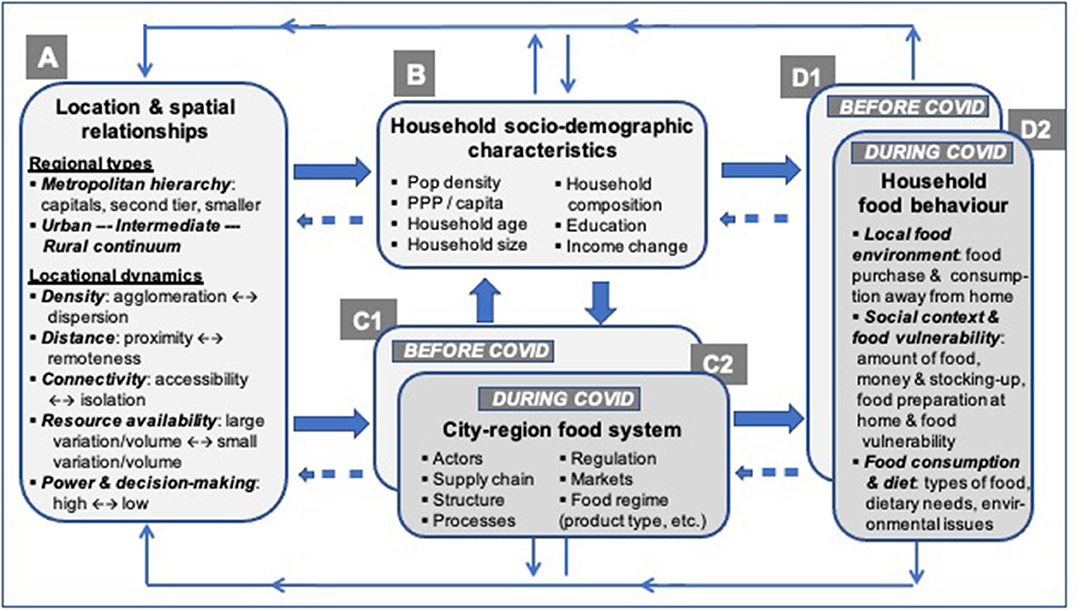

In this paper we focus on the locational characteristics and spatial dynamics of household food behavior, both before and during COVID-19 within a European city-region food system context. This is expressed through the six regional types specified in Figure 1 box A and defined in detail in Section Sample and Data Analysis. Box A also summarizes the five main locational characteristics that we propose underpin the differences between the six regional types relevant for city-region food systems.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of potential relationships between regions, household characteristics and city-region food systems and their influence on food behavior before and during the pandemic.

Box B in Figure 1 summarizes the socio-demographic characteristics of households examined in this paper. Box C1 outlines the main characteristics of city-region food systems before COVID-19 which are likely to interplay with Box B and then together shape the specific elements of household food behavior examined in the paper in Box D1. (This paper only focuses on the parts of the food system that directly interface with consumers.) Most of the literature draws a clear causative link between Boxes B and C acting together, on the one hand, and Box D on the other (for example Janssen et al., 2021), and our paper will also touch on these relationships. However, the main proposition is that much of the significant unevenness through space of Box B's socio-demographics and Box C's food system can itself be directly linked to, and in some cases determined by, the type of region in Box A in which the household is located. (Note that an accompanying proposition could, of course be, that much of the households' socio-demographic variation, in addition to regional characteristics is also related to national characteristics, including food history and culture, and to the relative geographic position of each country in Europe, across which climate zones, soils and food systems vary. However, this proposition is not pursued in this paper but might be tested in follow-up research.) The expectation is that the influence of Box A on Boxes B and C is not deterministic at the micro scale of individual households or food systems. But, at the macro aggregated scale, of which we have taken a valid sample (see Section Methodology Flow Chart below), clear spatial effects determined by the regional types can be expected (for example, see Eurostat European Commission Statistical Office of the European Union, 2020).

Thus, we expect that location has an important influence on household food behavior, both via the household's socio-demographic characteristics as well as via the structure and processes of the city-region food system itself. We might also expect that a sudden and severe shock, like that occasioned by COVID-19, will significantly change Box C1 to Box C2, and that C2 together with B, both shaped by A, will lead to a new pattern of household food behavior in Box D2. In the context of the city-region food system, this paper attempts to analyze and explain many of these influences and relationships given that cities vary down the metropolitan hierarchy and that they are embedded in different regional milieux along the urban-intermediate-rural continuum. We will then propose actions and policies needed to strengthen European city-region food system resilience and sustainability.

Figure 2 outlines the main steps in the overall methodology of this paper, commencing with data collection design and implementation based on an online questionnaire accessible via a dedicated website (https://www.food-covid-19.org/) and available as part of the Supplementary Material. This was designed to capture the changes in respondents' behavior in relation to food provision, preparation and consumption, as well as experiences of COVID-19-related illness, regulations and closures. Ancillary information was also collected on household socio-economic characteristics, including respondents' postcodes which were subsequently allocated to NUTS-3 regions using Eurostat conversion tables that also provide data on the regional types used in this paper. Exactly the same questions were used in each country's questionnaire, translated from the master English version by local partners. Where useful, national names of, for example, the specific types of big and ordinary supermarkets, discount and other shops in questions 2–4 were added in order to maximize data comparability between countries. A dataset was constructed based on twelve countries for further analysis—see Section Sample and Data Analysis on the sample used.

In order to meet the aims of the paper and drawing on existing literature, Step 2 illustrates the two main regional typologies along the geographic center-periphery: a metropolitan hierarchy consisting of capital cities, second-tier metros and smaller metros; and an urban-intermediate-rural continuum – see Section Regional Typologies below. Step 2 also shows the two main predictors (independent variables) deployed in the analysis—the six regional types and whether households lost income during the first wave or not. Step 3 of the methodology flow chart indicates the main statistical methods used—see Section Sample and Data Analysis. Step 4 outlines how the results section of this paper is structured in Section Results. Finally, step 5 shows how the discussion part of the paper in Section Discussion is structured, drawing upon all previous steps.

The evidence base consists of online survey data from twelve countries with a good representation across Europe's varied food systems, food cultures, political systems, economic conditions, agricultural practices and climate zones: Czechia, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Serbia, Slovenia and the UK. The sampling of respondents combined two methods. First, representative quota samples of respondents based on gender, age, education and regional distribution (data collection by market research agencies), and second convenience sampling by which respondents were contacted largely via social media, although local researchers in these countries did attempt to reach out to all groups in all parts of the country. Questionnaire responses considered invalid and thus excluded were those where respondents took <5 min to answer or where they had responded incorrectly to attention-check questions in different parts of the questionnaire. This together resulted in responses from at least 100 households in each country yielding 7,368 responses in total (see Table 1 for overview).

Data was collected from March to July 2020. While the research network consisting of researchers from many countries needed to be established rapidly, not all of them were able to quickly ensure enough funding for representative sampling and data collection. As mentioned, in some cases, market research agencies were hired but funding was restricted so the quota sampling and data collection were accompanied by convenience sampling. We are aware that countries relying on convenience samples are not fully representative of the respective national populations and thus there would be limitations if we were to analyze the data on a country-by-country basis. However, as we do not provide such national comparisons in this paper but instead focus on Eurostat's general regional typology with the lowest number of respondents in any regional type at 883 out of a total of 7,368 respondents from 12 countries, we provide important insights into the households' food-related behavior during COVID-19. In addition, Section Regional Typologies shows that, in terms of socio-demographics, our sample does closely mirror the different regional types as described by Eurostat European Commission Statistical Office of the European Union (2020, p. 22). Thus, from a regional perspective we are confident that the results are valid and meaningful.

The data collected by market research agencies and researchers in individual countries were merged into a large dataset of respondents from all 12 countries. IBM SPSS and MS Excel software were used for data management and analysis. As the aim of the paper is to present a geographical perspective on a wide variety of food-related behavior of households we mostly used chi-square analysis and adjusted residuals to compare the differences between the types of regions (and of the effect of income loss). Student's t-tests and One-Way ANOVA were also used where appropriate, as indicated in the Supplementary Material. More detailed and sophisticated statistical analysis focusing on selected behaviors is planned in future.

Table 2 shows the two main regional typologies along the center-periphery regional dimension, their Eurostat-derived definitions and the sample sizes of usable validated data.

Table 3 provides data on the main range of socio-economic and demographic variables of the sample along the six regional types of the center-periphery dimension. Overall, as shown below, the sample is close to the whole population of these regions as described by Eurostat. Given the importance of income loss (which does not necessarily mean complete “loss” of income but any decrease) due to COVID-19 or anti-pandemic measures, data for income-loss and no-income-loss are presented separately where appropriate.

In Table 4, comparisons are made between Eurostat's summaries of the whole regional population (Eurostat European Commission Statistical Office of the European Union, 2020, p. 22) with the sample taken in our survey, showing that the latter is largely representative of the former. (Note: a description of “urban” is not provided by Eurostat given it represents an approximation of all metros combined).

Table 4 demonstrates both that regional differences are statistically significant and that our sample is largely representative of the total population of regions, with only two noteworthy differences. In comparison with Eurostat's characterizations, these are that the sample's percentage of single households in capital cities is lower, and that the sample's mean household age in smaller metros is higher than in intermediate and rural areas generally.

In this section, a number of results are presented and commented showing different aspects of food behavior by comparing before with during the first wave of COVID-19 and how this behavior has changed during the pandemic. This is undertaken from the center-periphery perspective collectively across the 12 countries of the sample using the two regional typologies of the metropolitan hierarchy and the urban-rural continuum. Figures are presented based upon the data provided in the Supplementary Material, which also indicates their statistical significance. All results commented below are statistically significant unless otherwise stated. It is important to note that the vertical scales within each figure are configured differently to demonstrate the specific regional variations involved. If all scales were standardized, the illustrative power of many figures would be lost, making them redundant and the alternative would be large data tables. Most figures are in percentages and, unless otherwise stated, this refers to the proportion of households in a given regional type that either: (i) behaved as described by the given variable; (ii) or changed the behavior described either by an increase or decrease overall; or (iii) expected that this behavior change will continue in future either positively or negatively overall. The reader is thus enjoined to note the scale of each figure and to refer to the Supplementary Material for all data.

The analysis shows the overwhelming importance across almost all food behaviors of whether or not households lost income during the pandemic, and that this often varies between regional types. Some of this variation may be related to COVID-19 related restrictions imposed nationally or locally, as shown in Figure 3. This shows differences between the self-reported restrictions experienced by the income-loss and no-income-loss cohorts in 11 of the 12 countries in the sample (the exception being Hungary where restriction data was not collected). The income-loss/no-income-loss variable is also significantly related to Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) per inhabitant across the six regional types, as shown in Table 3, so could also function in some respects as a surrogate for actual mean income.

The data on restrictions due to COVID-19 are as reported by the sample households, which may or may not be the formal situation but, as this represents their personal experiences, is useful in putting their food behavior changes into context. It can be seen from Figure 3 (and with reference to the Supplementary Material) that income-loss compared to no-income-loss households have been impacted more severely by travel restrictions and closures and that all of the metropolitan regional differences are significant in terms of travel restrictions as well as the closure of eateries (comprising restaurants and cafés as well as other outlets like hotels and pubs where the on-premises eating of food is available) and of physical workplaces. These include general travel restrictions in both capitals and second-tier metros (though not in smaller metros), as well as public transport restrictions and the closure of physical workspaces in all metro regions, all of which are often locally/regionally imposed. The differences between the two household types are much smaller and are not significant in terms of the closure of eateries and educational and similar establishments, reflecting that these restrictions tend to be more ubiquitously imposed at national level.

In terms of COVID-19 health impacts, the only significant difference is related to isolation in capital cities which is much greater than elsewhere due to a combination of higher population densities and smaller housing units, and especially a much greater proportions of high rise apartments than of individual houses. Less than one third of the differences along the urban-rural continuum are significant, and where they are this is mainly due to the contrasts between urban and rural in terms of closures of physical premises.

Figure 4 and the Supplementary Material show that differences in where households shop before compared to during COVID-19 are significant in most cases, thus indicating that the pandemic has had a profound impact. The figure also reveals many significant differences in terms of income-loss as well as along the center-periphery dimension. “Big market” is defined as large food supermarkets, whereas “grocery” indicates smaller establishments. (In each country, named examples of each type were provided in the questionnaire completed by households to improve the consistency of responses. Discount shops are included in both but tend to be smaller so are more often in the “grocery” category. “Grocery” also includes standalone bakeries and butchers).

Figure 4 shows a significant decrease in “big market” shopping during COVID-19 but a lower decrease in “grocery” shopping, even though “big market” shopping remains the most important. Again, these changes are more likely to be significant down the metropolitan hierarchy than along the urban-rural continuum, but significant changes are also seen in the latter. Despite these decreases, shopping in “big market” and “grocery” is significantly higher in smaller metros, except by income-loss households during COVID-19 indicating that the latter tend to react more strongly under stress.

Shopping at AFN shops (i.e., alternative food networks including farm markets, street markets, cooperatively owned or solidarity shops, specialist organic food outlets and buying food directly from the producers) also decreased significantly during the pandemic, but this decrease was less pronounced in the smaller metros than in capitals or second-tier metros, and less pronounced in rural areas. However, given the nature of AFN, this may be due to the time the data was collected, not as a result of the pandemic itself, although there may be differences between countries as in Central Europe it is often not possible to buy local vegetables or fruits in the spring being out of season. Also in Czechia, for example, farmers' markets were banned in the spring of 2020. Interestingly, smaller metros, in strong contrast to the other metros, saw little difference in AFN shopping between income-loss and no-income-loss households as well as between before and during the pandemic, as also noted in relation to “grocery” shopping. It is also interesting to see that households in urban regions are more likely to shop at AFN than in intermediate or rural regions.

In contrast to in-person shopping, there were significant increases in the home delivery of meals ordered online or by telephone during COVID-19 across all regions and especially by income-loss households, but that this service is used decreasingly along the center-periphery dimension. This is probably related to the lower availability of such services, although smaller metros again go against this decreasing trend to some extent. In terms of meals from take-away shops, a decrease is seen from before to during the pandemic, together with a decrease along the center-periphery dimension However, again the smaller metros seem to strongly defy this trend although only before COVID-19 and that this difference disappears during the pandemic.

As with home delivery, there is generally a significant increase in food obtained from local food producers during COVID-19, with income-loss households doing so much more than no-income-loss households. The only exception is no-income-loss households in capital cities. The move to local producers is exceptionally strong in the smaller metros and especially amongst income-loss households, which also are much more likely to state that this shift will continue after the pandemic. Such households in rural areas also state that this behavior is likely to continue. These patterns are generally supported by households traveling shorter distances to food shops during COVID-19 compared to before, and again this is especially marked in the smaller metros. However, no regions expect this behavior to continue after the pandemic, although smaller metros are less likely to state this than any other regional type.

Thus, during the pandemic the food-purchasing behavior of both household types changed toward smaller, more specialist and local geographically proximate outlets, probably both because this was perceived as less risky due to exposure to fewer people, but also because of travel and other restrictions.

Figure 5 illustrates the substantial decreases in all types of eating away from home during COVID-19, especially for income-loss households which, before the pandemic, tended to eat more often out of the home than no-income-loss households. This is perhaps because they were more likely to avail themselves of the typically subsidized meals in workplace canteens and/or eat in cheaper fast-food eateries, which many of the comments made by the respondents show. Both types of household decreased away from home eating from between 15 and 40% down to 10% or less, but with little difference between the two household types during the pandemic. The latter probably reflects the severely reduced opportunities for eating outside the home that affected both types of households equally. The greatest reductions are in visits to eateries, followed, respectively, by eating in work canteens and from street-vendors, clearly as a consequence of the closure of most of these food outlets by national and local regulations. In contrast, eating away from home with family or friends was greatest for no-income-loss households before COVID-19. This is probably because these more affluent households have fewer children (see Table 3) and are more likely to have family or friends with homes that are better suited to hosting meals for others.

As above there is often a significant decreasing trend between center and periphery in line with a decrease in the availability of away-from-home eating outlets as population densities decrease. However, smaller metros again throw up some interesting exceptions in all examples except the use of eateries. Thus, for each of the other three examples, there is little difference between income-loss and no-income-loss households in the smaller metros, whether before or during COVID-19.

How the amount of food, money spent and food stocking changed during COVID-19 is illustrated in Figure 6. In terms of food eaten, income-loss households report increased intake more than non-income-loss households, and the former also expects that this change will continue after the pandemic. This is perhaps because eating food helps more-financially stressed households seek some solace from the COVID-19 shock more so than no-income-loss households. Moreover, in both household types there is a relatively large increase in unhealthy “comfort” food whilst fresh food consumption tended to decrease, and this difference is greater in income-loss-households (see Section Food Consumption). In line with the increased food consumption, income-loss households also increased the amount of money spent on food during COVID-19 much more than no-income-loss households, although both types saw increases. Thus, although money was increasingly scarce for the former, it is likely that the lack of many other spending opportunities during the pandemic, especially in rural areas which saw the biggest difference between the two household types, reinforced the displacement behavior that increased food consumption and spending provided.

It is also noteworthy that, as observed in many other food behaviors, the difference between the two household types was very low in the smaller metros. Income-loss households also expect that this change will continue more than the no-income-loss households so that, both in terms of the amounts of food eaten and money spent, income-loss households predict that food behavior changes induced by the pandemic are more likely to continue for the longer term. In other words, the pandemic has impacted income-loss households more deeply and probably for a longer period, than it has other households. A very similar situation is seen in relation to the stocking of food during COVID-19, so that income-loss households do this much more, again reflecting their greater food anxiety and stress, although the only exception, once again, is in the smaller metros where there is little difference between the two household types.

In terms of regional differences, there are only weak, inconsistent and largely insignificant changes along the center-periphery dimension, except in the case of the smaller metros. Here, the differences between income-loss and no-income-loss households are in all cases smaller than elsewhere. When looking at all metropolitan households, changes in the amounts of food eaten and money spent during COVID-19 are lowest in smaller metros. Thus, smaller metros seem again to exemplify a more balanced overall affluent type of region with more money to spend on less, but higher quality and healthier, food (see also Section Food Consumption).

There are many significant differences in how food behavior changes from before to during COVID-19 across the different types and locations of households. Figure 7 shows that the use of ready-made meals has decreased especially for income-loss households. However, there is little difference across the six regional types with the marked exception of the smaller metros which before COVID-19 used such meals more than any other region and continued to do so during the pandemic. Smaller metros also behave against the overall center-periphery trend in the use of processed ingredients in meal preparation. Income-loss and no-income-loss households make the similarly highest use of processed ingredients before COVID-19 in the smaller metros, whilst all other regional differences are small. However, during COVID-19 this distinction largely disappears. In terms of the use of raw ingredients, both household types use a similar amount before COVID-19, but during the pandemic income-loss households increase their use of raw ingredients much more than no-income-loss households and these differences are greater in the smaller metros. Overall, the use of raw ingredients is greater than of processed ingredients at between 80 and 90% of all households compared with between 45 and 60% before and during COVID-19. The pandemic also induces a general increase in the use of raw ingredients and a decrease in processed ingredients in a largely similar manner in both income-loss and no-income-loss households, and this is most conspicuous in the smaller metros which again stand out against the overall trends.

In terms of households growing their own food at home, it is unsurprising that this is significantly greater in intermediate and rural regions, where generally there is more land available, and that the activity increases significantly during the pandemic in all regions to about the same extent. In addition, in metropolitan regions the activity is overall significantly higher in the smaller metros, and there is also greater expectation here that this will continue in future, as there is in rural regions. Self-produced food has grown in importance for all households but to a much greater extent in income-loss households which could be explained by the income-loss shock. However, income-loss households also grew their own food more often before COVID-19 than no-income-loss households which suggests that it could either be because there is more need or that food growing is a habit of the social groups which suffered income-loss during the pandemic, although their motivation could be very diverse, not only economic. These households also expect their increased awareness of home-grown food to continue in future, whilst non-income-loss households generally do not. In both types of households, however, those in the smaller metros are significantly more positive that this change will continue. As also shown below in Section Food Vulnerability, income-loss-households also obtain more food from food banks, eat more free hostel meals, are more anxious about obtaining enough food and have missed more meals than no-income-loss households, and these differences generally increased sharply during COVID-19. This underlines the critical nature of such shocks on financially weaker and more food-vulnerable households.

When looking at the range of food prepared at home, Figure 7 shows an overall increase of between 6 and 18%, but with few differences between regions except when broken down into income-loss and no-income-loss households. The former have increased the range of food prepared significantly more than the latter, apart from in smaller metros where there is little difference. Again, this appears to point to the conclusion that these regions are more socially balanced and inclusive. This also seems to apply to the increase in the number of ingredients and recipes used during the pandemic which is again significantly higher in income-loss compared to no-income-loss households but with much less difference between the two in smaller metros. These differences are replicated in households' expectations that these changes in how food is prepared and in food dish types will continue in future—again there are significant differences between the two types of households, with income-loss households generally positive while no-income-loss households generally negative, except in smaller metros where the differences are much smaller though still significant. This is again evidence that financially weaker households have been obliged to change much more than financially stronger households.

Finally, the pandemic has changed the person responsible for food by between 9 and 24% of households, with a significantly greater change in income-loss households, although again this is much less in the smaller metros. Overall, the biggest change has taken place in capital cities, perhaps because here COVID-19's induced stress on family life tends to be more acute. In most capitals many more households live in small apartments and there have been more stringent lock-down restrictions here, as shown in Figure 3. This means that more people were forced out of workplaces and more eateries closed, putting even greater focus on food and meals at home often for longer periods than in other regions, leading to the re-jigging of personal responsibilities. Figure 7 also shows that all households do not expect these changes to food responsibilities to continue, but that this is less so in income-loss households and in smaller metros.

Figure 8 presents several variables examining food vulnerability and how this has changed from before to during COVID-19. These build on the many results already presented regarding the relative vulnerability of income-loss compared to no-income-loss households and how this is typically higher in second-tier metros and, depending on the issue, sometimes higher in capitals and rural areas. The use of food banks generally doubled during the pandemic but from a very low base of about 1–3%, perhaps reflecting the early nature of the survey during the first wave, given there is substantial evidence of much greater subsequent increases amongst certain types of households and locations Capodistrias et al. (2021). But, compared with other kinds of food obtained, this category is the smallest and also food bank increase is in general low. As would be expected, income-loss households both had a higher before COVID-19 use of food banks but also much greater increases than no-income-loss households. Both were greater in metro regions than elsewhere, probably because the number of food banks is large here reflecting the population density, although during COVID-19 the focus shifted to smaller metros perhaps for this reason. Similar results are seen for the access of free-food in hostels although this is much greater at between 10 and 20%, with fewer differences between metro regions and others, and at their lowest in the smaller metros. This may be because hostels have a much more visible presence than food banks as already prepared food is consumed in public compared with the food-banks' provision of ingredients that households take home to prepare meals in private.

In terms of psychological worries and anxiety about obtaining food, this has risen from between 10 and 20% before COVID-19 to up to 30% during. Again, this is greatest in income-loss-households, and lowest in the smaller metros where the differences between the two household types is smallest. Similar results are seen regarding missed meals and food insufficiency which tend to be highest in capitals and rural areas, despite the latter growing more food at home but where there are more likely to be pockets of poverty. These concerns are lowest in smaller metros which generally combine relatively high incomes with low poverty.

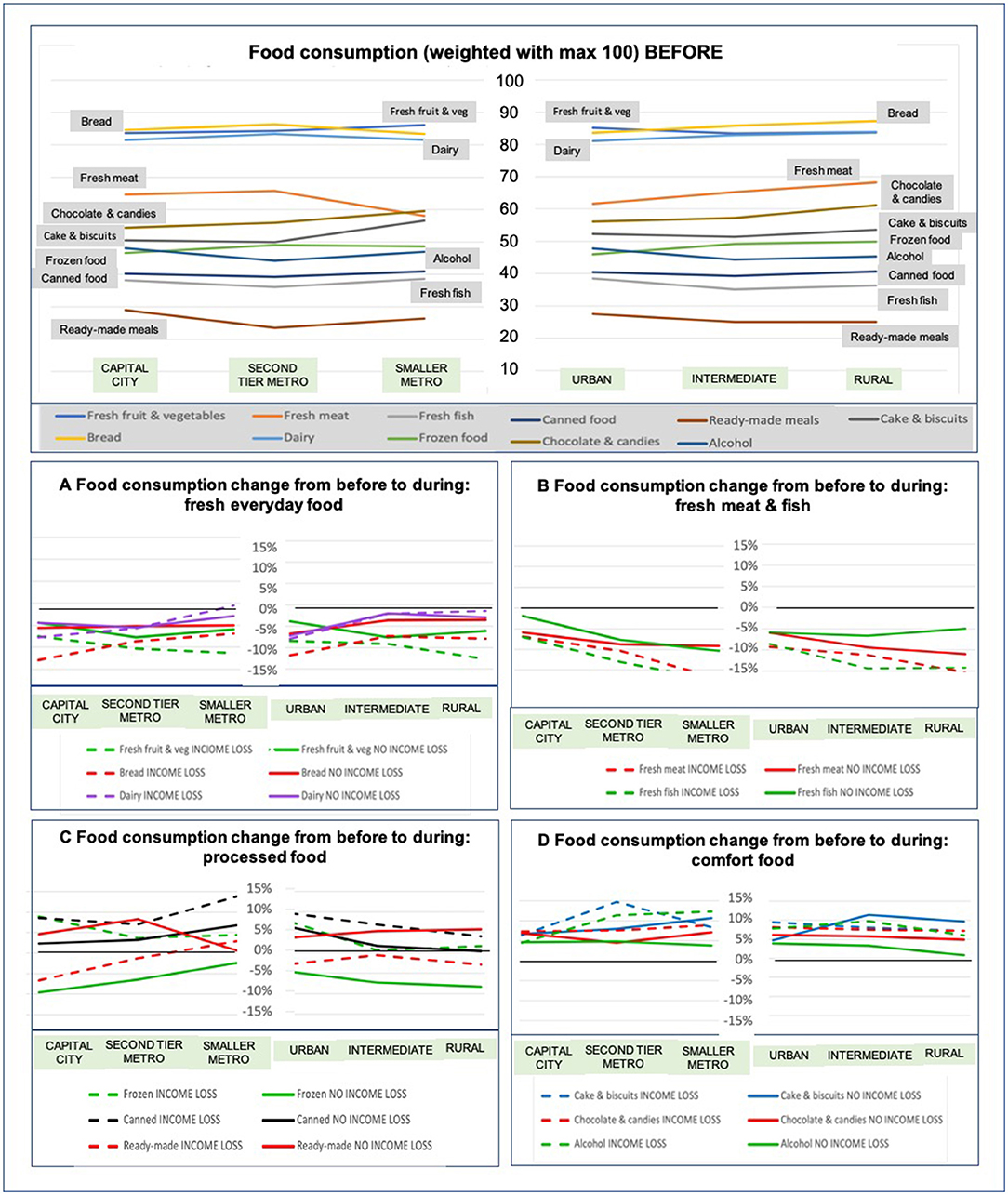

The survey examined 11 types of food consumption, as presented in Figure 9, first showing pre-COVID-19 consumption levels and, second, how these types form four groups depicting how consumption changed during the pandemic. The figure shows that the highest consumption frequencies before COVID-19 are of fresh everyday food (fresh fruit and vegetables, bread and dairy products), followed by fresh meat, then so-called comfort food (cake and biscuits, chocolates and sweets and alcohol), and finally by processed foods (frozen, canned and ready-made) and fresh fish. There are few variations across the six regional types, although there is some greater tendency to consume fresh meat and comfort foods in rural areas, fresh meat in capitals and comfort foods in smaller metros (the latter may be due to the larger number of families with children in these regions consuming cakes and sweets). Otherwise, these apparently quite typical European food consumption patterns seem relatively ubiquitous, at least across the 12 countries in the survey, resulting from the strong moves over recent decades to a common European food sector producing and consuming increasingly standardized foodstuffs. This is, however, not to imply that strong national, regional and local food types and cuisines are no longer important in Europe, but their importance has become diminished over recent decades, an issue which our survey has not examined.

Figure 9. (A–D) Food consumption. Data for the top diagram is a sum of each households' consumption before the pandemic of the 11 food items shown, weighted on a 6-point Likert scale by the frequency of consumption: less than once a fortnight or never; between once a week and once a fortnight; once a week; 2–3 times a week; 4–6 times a week; daily. Summed results were then standardized out of a possible maximum of 100, for example if all households in a specific regional type consumed a particular food item daily then the score would be 100.

The second part of Figure 9 shows that the COVID-19 shock has led to some dramatic changes in food consumption behaviors. Fresh food consumption decreased significantly, whilst both processed and comfort food increased. Figures 9A,B both show decreases of between 0 and 15%, but with different patterns. Fresh everyday food decreased most in capital cities and generally least in smaller metros and rural areas, which might be explained by tighter supply constraints on fresh food in the former, although in the latter two areas fresh fruit/vegetables did decrease strongly amongst income-loss households. In terms of fresh fruit/vegetables and bread, both with the shortest shelf-lives, the decreases were greatest amongst income-loss households, but least for dairy products with longer shelf-lives. The consumption of fresh meat and fish saw similar decreases but geographically the reverse compared to fresh everyday food. Apart from this, in all regions fresh food decreases were greatest in income-loss households.

In contrast to decreases in fresh food consumption during the pandemic, Figures 9C,D show strong increases in processed and comfort food of up to 15%. Both phenomena might be explained by greater supply constraints on fresh foodstuffs, compared to more stocking-up and the advantages of longer shelf-lives of non-fresh foodstuffs during COVID-19 restrictions. In terms of processed foodstuffs, although there were a few decreases in most regions (ready-made in income loss households, and frozen in no-income-loss households), increases were greatest in the smaller metros. Income-loss households consumed more canned and frozen foods than no-income-loss households, but the reverse was the case with ready-made meals. The comfort food category increased more than any other type, with no decreases. This is possibly because of their potential stress-ameliorating characteristics and the fact that many more adults and children were at home virtually constantly, which clearly increased snacking and in-between meal-time consumption. This pattern appears to be similar across all regions, although income-loss households in second-tier metros consumed more cakes/biscuits and alcohol than elsewhere, and no-income-loss households in intermediate regions consumed most cake/biscuits. Apart from the latter, income-loss households always consumed more comfort food than other households. If these trends continue, it could bring serious negative health consequences especially in these more distressed regional types and amongst the most financially stressed households, made worse by the decrease in fresh food consumption.

The first diagram in Figure 10 shows the regional variations of households with special dietary needs and that these are significantly greater in income-loss households in capital cities and rural areas where, as noted above, there are more likely to be pockets of poverty.

The second diagram depicts some of the environmental impacts of food consumption and diet. The purchase of unpackaged foodstuffs (mainly fresh fruit and vegetables) has increased across all regions by up to 20% and more so amongst income-loss households and in smaller metros, although in the latter both household types purchase to the same extent. This is a relatively positive finding given the more careful approach taken by shops to foodstuffs and the application of stricter hygienic measures during the pandemic. The consumption of organic foods has, however, generally decreased by up to -10% in all households and significantly more so in smaller metros although this is mainly due to income-loss households.

Significant decreases in food waste have occurred in the context of the greater importance given to food during the pandemic by all groups, perhaps because of food supply problems. Interestingly, this reduction is seen more in income-loss households probably related to the greater financial stress they experience, so that not immediately discarding uneaten food, and even consuming food after the sell-by date, can become important. Reduced food waste is also seen across all regions with the greatest decreases in smaller metros. These regions seem generally to be the most environmentally aware, probably related to their relatively large incomes, high educational levels and their overall more balanced socio-demographics. Smaller metros also have the highest proportion of families with children which is likely to make households more aware of the importance of both diet and environmental issues, even though at the same time comfort food eating increased more in smaller metros than other regions (except second-tier metros), perhaps itself also related to consumption by children.

In line with Eurostat European Commission Statistical Office of the European Union's (2020) description of Europe's regional geography, this paper's sample of 7,368 respondents across 12 European countries demonstrates distinctive regional variations often revealing the highly significant alignment and interaction between geography and society. Thus, there are regular trends from higher to lower from the center of capital cities to the rural periphery, for example in terms of the data in Table 3 on population density, income (PPP) and education. These are molded by five locational dynamics that play out over geographic space (see the conceptual framework in Figure 1) that are largely determined, shaped and sorted by the mutual relationships between them, both within a given region as well as between regions:

• Density: ranging from agglomeration to the dispersion of people, consumers, stakeholders and their activities along the food value chain, as well as the organizations and firms that support this.

• Distance: the relative distance between these actors, activities and organizations of the food value chain across space, ranging from proximate to remote.

• Connectivity, both physical and virtual: ranging from accessible to isolated in terms of how easy, quick, timely, costly and convenient it is to connect with any location. New technology is increasingly enabling food producers to undertake many product monitoring, cultivation and harvesting tasks remotely, and consumers are able to select and order food online and get it delivered rapidly, phenomena which have been considerably magnified during COVID-19 as evidenced by the significant growth of home delivery during the pandemic (Figure 4). However, food is, and will remain at least for the foreseeable future, a physical object and thereby subject, to a greater or lesser extent, to these locational and spatial dynamics.

• Resource availability for all food stakeholders and organizations: ranging from large to small variation and volume, for example in terms of all human resources, capital, soft and hard infrastructures, etc., required along the whole food value chain.

• Power and decision-making, both political and market: ranging from high to low within a national context, for example the ability to determine and allocate resources and make rules and regulations for all relevant stakeholders and organizations along the food value chain.

These five locational dynamics operate along the whole of the center-periphery dimension and are visible in most of the results presented in Section Results. For example, they are very clear in terms of home delivery (Figure 4) but not at all when eating away from home with family and friends (Figure 5). The former likely reflects the relatively density, connectivity and resources of retail outlets offering these services away from the center, while the latter is predominantly determined by social relations and, although this can be affected by population density, it only appears to be important for income-loss households which have limited resources and probably less accommodation space regardless of where they live. Another contrast is food consumption before COVID-19 which, in a European context, is hardly affected by where people live (Figure 9), whereas geography clearly becomes important during COVID-19 (also Figure 9), thereby suggesting that in some cases a shock like the pandemic can re-prioritize geography over the market.

There are also smaller scale regular center-periphery trends around individual cities and towns, for example around capitals, second tier metros, smaller metros, as well as towns in rural areas, each operating over shorter distances with smaller hinterlands as manifestations of individual city-region food systems. When regional, national and continental markets become stronger, however, these have increasingly overlapped and nested within each other while becoming weaker. As seen in the food consumption example above during the pandemic shock, this process can be temporally and perhaps permanently reversed in favor of shorter value chains, exemplified by the move to smaller retail outlets, local producers and shopping (see Figure 4).

There is, however, one very prominent exception to the center-periphery trend regularity, i.e., the smaller metros which in most cases in Section Results have disrupted these trends acting more like local/regional capital cities in terms of their socio-demographics and food behavior. In fact, they often display many of the advantages of capital cities while foregoing some of the disadvantages, such as having the lowest percentage of income-loss households, the most balanced household composition and relatively high incomes but with fewer extremes as compared with capitals (see Table 3). Capitals typically exhibit pockets of poverty alongside very wealthy households, while second-tier metros are more likely to be characterized by the lowest metro incomes as former industrial areas that have been left behind economically with relatively high levels of unemployment, poverty and social exclusion. As outlined in Section Regional Typologies, these differences are typical of most European regions recognized by Eurostat European Commission Statistical Office of the European Union (2020), in our sample's socio-demographic characteristics, as well as in most of the results presented in Section Results. For example, smaller metros typically change less during COVID-19 as well as exhibit no or smaller, though sometimes still significant, differences between income-loss and no-income-loss households. In this way, they demonstrate their relative demographic and food system cohesion and resilience compared with the other regional types.

The specific role of smaller metros in food systems is an important conclusion arising from this paper and is clearly reflected in the modeling of the current stage of the urbanization cycle, described in Section Regional Perspectives. This is the current counter-urbanization trend resulting in the growth of smaller cities beyond the traditional suburbs accompanied by population decline in the core and its suburbs. This is being recognized in many countries, for example, the Danish Knowledge Centre for Housing Economics Boligøkonomisk Videnscenter (2021) is charting the movement of population out of the five largest Danish Cities, including Copenhagen, to the smaller provincial cities in their hinterlands. These are today the fastest growing municipalities in a development that is expected to continue to at least 2040 and which is also being fueled by movements from rural areas. This dynamic is being driven by a better quality of life balancing urban and rural advantages, high services levels, as well as continued good connectivity to the larger cities when desired.

Another main finding of the study which has, unlike the regional dimension, been noted by other authors (see Section Household Responses to the Pandemic) is the high importance of the income-loss/no-income-loss variable in this study. It is significant in many before-COVID-19 food behaviors as a good surrogate for individual household income, so that households with income-loss during COVID-19 were likely to be fragile even before the pandemic which then made their situation worse. Income-loss households nearly always experienced food behavior changes arising from COVID-19 much more than no-income-loss households, probably because their financial and social situations are more precarious, so they are more sensitive to external shocks and are likely to react more strongly under stress. The precariousness of income-loss-households is also related to the fact that they over represented in regions with the lowest PPP/inhabitant, have a lower mean age and are more likely to be families with children, which together imply both lower earning potential and that finances need to be stretched further.

On the other hand, income-loss-households are much more likely to state that the positive changes they have made, and perhaps forced to make, during COVID-19 are more likely to continue post-pandemic. For example, shopping with local producers and in more local shops, growing own food, and using a wider range of food dishes and recipes. This could be a useful policy issue but is only likely to be realized if it is made as easy as possible for such changes to continue through better designed and simplified choice architectures with incentives and other focused supports, and where the household benefits can readily be seen within a short timeframe. However, it is not known whether this expectation that the changed behavior will continue is because they can see the benefits of such changes, which in some though but by no means all cases are already practiced by no-income-loss households, or because they expect their relatively precarious situation will persist regardless of the state of the pandemic. How these impacts will play out over the longer term is a critical issue and needs focused research, especially because the likelihood of other shocks with similar effects is high, whether these are new pandemics, climate change, new disruptive technology, geo-political and economic-trade tensions, etc. These concerns are, for example, voiced by the European Commission (2020, 2021), IPES-Food (2020), KPMG (2021), Millard (2020), OECD (2020), and World Economic Forum (2021b).

The income-loss/no-income-loss household balance also typically varies significantly between regional types, more often down the metropolitan hierarchy than along the urban-intermediate-rural continuum, although when there are differences in the latter this is almost always between urban regions on the one hand and rural regions on the other. However, the relative vulnerability of income-loss compared to no-income-loss households is typically highest in second-tier metros and, depending on the issue, sometimes higher in capitals and rural areas.

It is clear from the literature review, and now strongly supported by this paper, that an interdisciplinary and strong regional approach to food system development is necessary to advance food research and practice and to improve our understanding of how to create more effective, inclusive and sustainable city-region food systems. The results above, describing the changes at household level, especially in terms of income-loss or no-income-loss as well as household composition and along the center-periphery dimension, illustrate how food systems are regionally differentiated despite the majority becoming increasingly globalized over recent decades (von Braun et al., 2021). Moreover, the disruption caused by COVID-19 has further exacerbated inequalities and regional differences, highlighting both societal and regional winners and losers. Besides being an original contribution to the debate, the paper gives further strength to the pledges for the post-pandemic reform of food systems that must start from the socio-economic and geographic reality that also recognizes how these two dynamics are interrelated (IPES-Food, 2020). Also, in light of the EU's Farm to Fork Strategy (2020), this means making city-region and especially local food systems the main focus for addressing food security and sustainability (European Committee of Regions, 2020). The upcoming new European Common Agricultural Policy could become the most important policy framework to support the structuring of such food systems, directly addressing the weak spots that have been exposed by COVID-19 (European Commission, 2021). For instance, the objective of greater food security cannot disregard the role of small farmers and local supply chains that need enhanced roles in the market, and the implications this has for the production, processing, transportation and selling of food. The socio-economic crisis caused by the pandemic has also highlighted a need for much more equitable supply chains that are capable of guaranteeing fair remuneration, high quality and resilient security along shortened value chains and at affordable prices for consumers.

From a wider policy perspective, it is also necessary to strengthen urban-rural linkages and to ensure that food systems are properly included in urban and area planning and programming, for example in relation to land access and tenure for food production, market access for smallholders and investment in both the urban and rural axes of value chains (Sharifi and Khavarian-Garmsir, 2020). It is moreover necessary to institutionalize the commitment of cities to include food and nutrition as a high priority policy, adequately embedded within and supported by all other city policies. Thus, effort needs to be placed on building widespread government support, in addition to the commitment of other actors in the private and civil society sectors. Overall, it is often the food system related issues, as described in the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact (2015), that can provide a “breakthrough” moment that can bring silos together, also with spill-over impacts on the cities' other non-food issues. However, policies and strategies should not rely on market-oriented approaches alone as the potential of non-market food provisioning is far from being negligible even in urban areas as shown by our results and previous research (e.g., Vávra et al., 2018b). Various forms of urban gardening, as well as growing food in publicly accessible spaces often labeled as the “edible city” concept (Artmann et al., 2020), can play an important role in redesigning city food region systems.

This paper shows that COVID-19 has many asymmetrical impacts across territories, while many policy responses remain place-blind and uniform, thus highlighting the need for more place-based and people-centered approaches. In the context of food provisioning and consumption, the rediscovery of proximity will provide a window to shift faster from the status quo to more sustainable food systems, based on equitable relationships along the supply chain, social justice and market equity (Klassen and Murphy, 2020; Picchioni et al., 2021). Overall, the COVID-19 shock calls for a stronger focus on resilience as preparedness for future shocks requires managing who does what at which scale and how, especially at the city-region scale.

New business models are also needed that encourage a social economy to engage citizens through cooperatives or other forms of social enterprises in food production and distribution. Many of the lessons are already being learned and applied but to date have mostly appeared autonomously and bottom-up in many cities and towns in Europe and worldwide as a response to the crisis. It is up to policy makers at all levels to recognize, support and further develop them, so that future crises, no matter their nature, will have fewer detrimental impacts. Thus, dedicated long-term efforts are needed, first, to break through siloed sectors and agencies, and then establish shared priorities and joint programs. In most city regions, increased collaboration between health, nutrition and social services, environmental planning and economic development, in addition to the traditional food system actors, is urgently needed.

The differences between the three types of metro region outlined above, as well as the urban-rural contrasts and links they imply, clearly have profound implications on how city-region food systems should be developed and supported. Research and policy should be re-directed to focus on re-scaling the food system by shifting significantly away from the conventional approach and transforming toward more sustainable and resilient food systems with significantly shortened value chains in an increasingly circular city-regional food cycle. This also specifically requires deploying circularity principles which look beyond the current “take, make, and waste” industrial model of food production, processing, provisioning and consumption in order to design out waste and pollution, keep products and materials in use, and regenerate natural systems. Circularity also boosts local commerce, jobs, social inclusion and more responsive local governance (Millard et al., 2021).

The household, neighborhood, city and peri-urban area are nested within the wider regional, national and global food systems. One fundamental question is, what is the hinterland/catchment area required to provide a town or city with its basic needs for nutritious, safe, secure, sustainable local and seasonal food, and how is this organized and governed? To answer this question, a transformation is required from a predominantly international and planet-wide system toward a more circular city-region food system that becomes much more self-sustaining and resilient. This implies a much greater emphasis on strong interrelations between the household, neighborhood, town/city and region. A nexus approach and thinking are thus needed—a city is only as resilient as the surrounding region is in terms of water, energy, food, logistics and natural ecosystems, all of which need to be seen as part of one interrelated system.

An important conclusion for city-region-food-system resilience policy is to learn the lesson that smaller cities are best able to cope with system shocks. They have the most balanced socio-demographic characteristics, are affected least and come through the shock best, and have the lowest schisms between weaker and stronger households. Joined-up policy should thus focus on emulating such conditions as best as possible, for example in terms of scale so that in capitals and second-tier metros a neighborhood or district approach should be prioritized especially where there is an over-representation of vulnerable households. This could include introducing the 15–20 min walkable neighborhood concept so that healthy food is accessible within 500 m for all residents as pioneered in Paris. This is a policy for developing a polycentric city, where density is made pleasant, one's proximity is vibrant, and social intensity, as a large number of productive, intricately linked social ties, is real (World Economic Forum, 2021a).

This paper also shows the importance and position of households as a basic socio-economic and “food” unit and reveals their different conditions and abilities to tackle the crisis. The potential of household resilience ranges from food logistics and planning and the structure of diet to various aspects of obtaining, preparing and stocking food. This also reflects the household's potential to grow its own food in the future as the possibility for this otherwise changes along the rural-urban continuum. Although our research shows the highest proportion of own food gardening is in intermediate and rural regions and by income-loss households, it also shows that significant increases during the pandemic were seen in urban as well as in rural areas. It is thus important to take into account the trends in urban areas as mentioned above, also given that other authors, like Schoen et al. (2021), show increasing interest in growing more food mainly in urban areas during COVID-19. Thus, municipalities should rethink their approach to urban planning and design (Mullins et al., 2021) in order to incorporate urban gardening into the sustainable development of towns and cities. Focus should be on, for example, allotment gardens, community gardens, schools, etc., including education and raising public awareness. Many cities and towns have initiated and implemented elaborate food plans, inspired by the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact (2015) and other strategic plans adding food issues into their agenda.