- 1Griffith Business School, Griffith University, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 2Griffith Business School, Griffith University, Southport, QLD, Australia

In Queensland, Australia, more than half of all women working in agriculture are employed as farmers or farm managers, and they contribute 33 percent of all on-farm income. However, women play a major role in contributing to day-to-day living and farm survival through their off-farm earnings, which is estimated to contribute an estimated $2,715 million or 84 percent of all off-farm income. Despite this major economic and social contribution, little is known about the barriers they face in achieving their leadership goals. In this article we analyse qualitative data from workshops with Queensland farm businesswomen using Acker's concept of the “ideal worker” and inequality regimes theory (1990, 2006) to highlight the issues farm businesswomen face when aspiring to become leaders and we develop the concept that the “ideal farmer” is male. We find that there is a long way to go for these women in the state of Queensland to achieve their leadership goals in this traditionally male-dominated industry. We identify that woman want to expand their roles and undertake leadership opportunities and be recognized by their partners and industry for the contributions they make. Structural (micro) and organizational (meso) level barriers and enablers both hinder and assist farm businesswomen to achieve their leadership goals.

Introduction

In Australia, women contribute half the total value attributable to farming communities through their paid and unpaid activities (Sheridan and McKenzie, 2009) and their contribution has been recognized as critically significant for farm family survival (Alston and Whittenbury, 2013). Despite widespread recognition that women in Australian agriculture represent an untapped potential for rural businesses, rural communities, and the nation, the economic and social contributions of women are not matched by their representation in leadership positions in key agricultural organizations. Women's role in agriculture and in rural communities is often overlooked leading to their roles in farming being described as “invisible” (e.g., Williams, 1992; Alston, 2003). This paper discusses the leadership and development aspirations of women in farm businesses in Queensland, one of the eight states and territories in Australia. Queensland comprises an area of 1.853 million km2, almost three times the area of France, and has a population of 5.11 million. Its climatic zones are tropical, sub-tropical, hot arid and warm temperate resulting in a wide variety of farming enterprises.

The focus of this article and research question is: What are the barriers which farm businesswomen in Queensland face in achieving their leadership goals? What are the conditions which assist farm businesswomen in achieving these goals? This article gives an overview of women's employment and contributions to agriculture in Australia, and an analysis of relevant international literature which shows similarities found in other economies. This highlights that Australian women are not alone in experiencing the impact of gender on the ability of women to be recognized as legitimate farmers and leaders in agriculture. Following the discussion of the methodology, the findings and discussion sections focus on the concepts of the “invisible worker” and inequality regimes (Acker, 2006). The findings highlight the lack of acknowledgment of women's roles in farm businesses and leadership roles, which has direct implications for economic and social development.

Women's Contribution to Agriculture in Australia

Women play an essential role in the Australian agricultural workforce. Self-employment is common and “family farming is officially recognized as the dominant mode of agricultural production” (Alston, 2015, p. 189). In 2019, 33 percent of all persons employed in agriculture were women (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2019). In August 2019 there were 177,952 Farmers and Farm Managers who plan, organize, control, coordinate and perform farming operations, 31.7 percent of whom were women, an increase of just over seven and a half percent since August 2016 (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2019). The 2019 ABS Labor Force survey data shows that more than half (53.7%) of all women working in agriculture were employed as Farmers and Farm Managers.

Women's economic contributions to the agriculture industry through on- and off-farm income are considerable. Sheridan and McKenzie (2009) estimate that women contributed 33 percent of all on-farm income ($8,558 million) to the agriculture industry in 2005–06. A relatively high number of women also undertake off-farm work where their “total contribution of over $2.7 billion represents ~83 percent of the estimated $3.26 billion of total off-farm wage income” (Jefferson and Mahendran, 2012, p. 200). This off-farm income generation is a critical survival strategy for most farm families as women are likely to work off-farm “for the much-needed income for the family to survive in agriculture” (Alston, 2010, p. 65). At least one-third of family farms are dependent on women's income (Alston, 2015) which “contributes significantly to families' day-to-day survival” (Alston et al., 2018, p. 6). Women generate “48 percent of real farm income through their off-farm and community work,” which goes to support the continued existence and development of the farming business (Alston, 2015, p. 198). Women in the agriculture workforce are more likely to spend time on unpaid domestic labor and to engage in volunteer activities than women nationally (Binks et al., 2018).

There is a range of historical and contemporary complexities in farming which has had an impact on how women are perceived as farmers and industry leaders in society (Annes et al., 2021). Both the Australian and international literatures identify that women's work in agriculture is devalued and their contributions within industry are likely to be minimized (Glover, 2014; Alston, 2015; Jackson Wall, 2022). Such notions have been perpetuated by “paternalistic attitudes” and gendered divisions of labor between home and work, and the operation of farming work taking place within an environment seen as hostile toward women (Glover, 2014, p. 288; Bossenbroek et al., 2015; Tchékémian, 2022). Women also endure being stereotyped as fragile, inferior or “incomplete,” compared to the image of the male farmer (Rasplus, 2020a; Annes et al., 2021; Jackson Wall, 2022; Savage et al., 2022 p. 30).

The European settlement of Australia in the nineteenth century was a male enterprise and there is evidence of this in the collection of government statistics: women were classified as non-economic earners in census data and have been under recognized in government policy (Alston, 2015). Farm work was shared by men, women, and children but the work of the last two groups rarely appeared in public records in Australia (Strachan and Henderson, 2008, p. 493; Strachan, 2009). Similarly, women were unrecognized in the census data of other economies such as Northern Ireland and France, thus contributing to women's invisibility in farming (Shortall, 2004; SOFA and Cheryl Doss, 2011; Puglise and Quagliariello, 2018; Rasplus, 2020b, 2021; Annes et al., 2021). Alston (2015) emphasizes that in Australia, historically, women have faced a range of issues that preclude them from being viewed and respected as credible contributors to individual farms and the broader farming community. She suggests that historical influences have contributed to gendered policy formation over time, and this, coupled with the lack of acknowledgment of women's roles in supporting the long and short-term sustainability of farms, has contributed to their lack of recognition.

Women in Rural Leadership in Queensland

It is difficult to gain a detailed picture of women's roles as leaders in their communities given the multiplicity of small organizations and the difficulty of accessing relevant data through publicly available information in Australia. Women in other countries are also shown to experience similar issues in terms of their recognition as farmers and leaders (Annes et al., 2021; Jackson Wall, 2022). However, one way that appears to have not been fully explored is the examination of the number of women in board positions in agricultural organizations, and this provides opportunities for the further analysis of the composition of gendered roles in the sector, the results of which provide a critical role in shaping the agenda of an organization in terms of increasing women in leadership positions (Alston, 2015, p. 192). Agricultural industry boards play an important role in their representation to government and manage significant government funds which deliver industry initiatives. Without the inclusion of women to provide their experiences and values, these boards may not be representative of the industry (Alston, 2015).

Historically, leadership positions in all industries have been held by men and therefore women farmers' aspirations for leadership have been obstructed. Women have often held a secondary status to that of male farmers (Glover, 2014; Annes et al., 2021; Tchékémian, 2022) and leadership positions in agriculture in Australia have been filled largely by older white males who were rarely representative of the sector (Alston, 2015). There have been calls for increased levels of female representation on agricultural industry and government boards since the 1990s. At the first rural women's international conference held in Melbourne in 1994, the Minister for Agriculture, “agreed that 50 percent of all agricultural and rural board positions would be held by women by 2000” (Alston, 2015, p. 197).

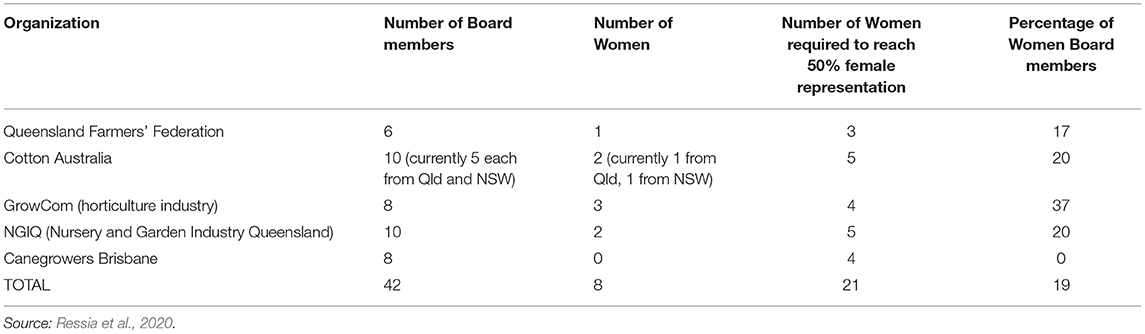

The Queensland Government had achieved 50% representation of women on all boards of Queensland Government Corporations in industries such as transport and energy by September 2019 (Department of Justice Attorney-General, 2021). In contrast, examination of the boards of the five major agricultural organizations in Queensland show that these targets were not achieved for women in agriculture leadership and women at best form one-third of members and at worst have no representation on some of the major agricultural industry boards in Queensland (see Table 1).

Table 1. Female representation on five of Queensland's agricultural boards: Queensland Farmers' Federation, Cotton Australia, NGIQ, GrowCom, and Canegrowers Brisbane.

Women Farmers as the Ideal Worker?

Farm businesswomen are not considered to fit the “ideal worker” type as they are not considered “true farmers” within the context of farm work. These women therefore experience discrimination due to the limited recognition of the importance of their roles (Glover, 2014, p. 280). Societal beliefs such as women's role as caregivers and men's role as breadwinners inform the concept of the “ideal worker” (Acker, 1990; Annes et al., 2021). The “ideal worker” is based on the model of the Caucasian male with no family or care responsibilities who works hard spending eight or more hours per day in the work environment paying full attention to work, and puts work first, totally dedicating themselves to paid employment (Acker, 2006; Sang et al., 2015). As such, notions of the ideal worker are tied to the male role, as they are assumed to be more committed to their employment and are subsequently viewed as being more suitable in achieving positions of authority and leadership (Ball, 2017). Therefore, women's roles become overshadowed and invisible due to their being tied to the male through providing labor in support of the male's farm work activities. The male therefore is unencumbered of the caring needs of the family and home (Williams, 2001; Gornick and Meyers, 2009) and further, is freed from the undervalued administrative tasks tied to the running the farm, often completed by a wife or partner (Glover, 2014). This “invisibility” ties back to historical, cultural and gendered views of women's work and their classification as non-economic earners in census data and government policy over time (Strachan and Henderson, 2008; Rasplus, 2020a, 2021).

Farm businesswomen may experience a sense of reduced power in terms of how they negotiate “new working arrangements” with their male partners, which in turn creates farm-level gender regimes which structure the way the farm, household, and off-farm work is managed (Alston, 2015, p. 193; Annes et al., 2021). Acker (2006) discusses gendered assumptions, such as expectations that men are to put work first and women are to put family ahead of their own desires to work. She describes how these result in underlying power regimes and gender-based inequalities in organizations, through her inequalities regimes theory. Acker defines inequality regimes as “loosely interrelated practices, processes, actions, and meanings that result in and maintain class, gender, and racial inequalities within particular organizations” and are linked to inequalities in societies, politics, history, and culture (Acker, 2006, p. 443). Consequential disparities of organizational gender-related inequalities, such as lesser power and control over goals and resources, workplace decisions on how to organize work, opportunities for interesting work, pay and other monetary rewards, and respect (Acker, 2006; Glover, 2014; Annes et al., 2021), may help to understand the gendered experiences and outcomes that farm businesswomen experience in their individual role as farmers and in their aspirations for leadership within broader organizational contexts

Methodology

This project undertook a detailed analysis of national statistics and re-examined the findings of a qualitative and quantitative study undertaken in the state of Queensland by the Queensland Farmers' Federation [QFF]. The data was collected by facilitators who conducted workshops throughout the state and took workshop notes and provides an insight into the views of Queensland farm businesswomen. This project examined the findings in the report titled “Cultivating the leadership potential of Queensland's farm businesswomen” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018), written by Manktelow, Muller and Slade. In this paper we concentrate on the qualitative workshop data, with the survey data providing some demographic details. The online survey was completed by 149 women, while a total of 82 women participated in the five workshops. The half-day workshops engaged women from a range of agricultural sectors in Queensland and were held in five major regional locations in 2017 (Mareeba−12 participants, Toowoomba-−24 participants, Caboolture-−14 participants, Emerald−10 participants, Bundaberg−22 participants). Discussions centered around “their current leadership roles, future aspirations, barriers and enablers to reaching their goals” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018 p. 9). Workshop findings led to the development of an online survey exploring “the key objectives of the project, seeking to gather information about women's current leadership activities and skills; their aspirations; barriers to participation; and enablers and development opportunities that women would choose to access” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 12). A convenience sample was used by Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF] (2018) for this exploratory research and the survey was promoted through workshop participants and project partner networks (Etikan et al., 2016). The survey collected responses from a range of age groups, with 53 percent aged between 31 and 50 and 30 percent were aged between 50 and 65. Fourteen percent were aged under 30 and 3 percent were aged over 65. Participants also indicated high levels of education with 82 per cent of all respondents holding a University qualification, 34 percent at undergraduate level and 26 percent at post-graduate level.

Three members of the research team qualitatively re-analyzed the workshop notes data collected by the Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF] (2018) by coding to identify themes and sub-themes considering the concepts of the “ideal worker” within the context of Acker's inequality regimes theory (2003, 2006). These codes were then formed into categories relating to the characteristics and diversity of women in farming, their current contributions, aspirations, the barriers and enablers to achieving their goals, and the training and organizational needs that would assist them in achieving business, social and leadership goals within the context of a traditionally male-dominated industry (Glover, 2014; Ressia et al., 2020).

Findings

Our analysis focused on the structural (micro) experiences of women and the meso level of agricultural and rural organizations. Our investigation of the national statistics and the QFF survey statistics clearly show that Queensland farm businesswomen are highly educated and are keen to expand their economic and social contributions. The data showed that many women are already active in carrying out leadership activities within their communities, and others were developing new business ventures such as in tourism (agritourism) (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 22, 28, 70). These women aspire to make further contributions both economically through their business development and socially in their own and other farming communities, and to state and national policy development. They undertake a range of leadership activities in the agriculture industry and within the community, for example, one farm businesswoman connected her passion for travel to farming and set up her own tour company taking rural women on tours to international agricultural locations (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018). In addition, many farm businesswomen want to be leaders and to encourage and help develop other women.

It is clear that women want to increase the level of their participation in senior management and leadership roles (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 1). Queensland farm businesswomen aspired to a wide range of roles within the next 5 years, which included providing mentoring for less experienced farm businesswomen, being a spokesperson or advocate within their industry and community, diversifying, innovating, value-adding or developing new areas of commercialization within a farm or another business, being on an industry association board, executive committee or research and development [R&D] advisory committee, or on a Government board or an advisory forum. However, they are constrained by factors such as the lack of recognition of their roles in farm businesses as one farm businesswoman elaborated:

“Today I look around and see young women doing great things and planning for a career in the agriculture or farming in every field. BUT I still find the board rooms and corporate sector wanting. On average in Australia's peak state agriculture lobby groups women only represent 20% of the boardroom. Is the government hearing our voices? Is the consideration made that a woman's perspective may be different?” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 29).

There appear to be a range of barriers preventing farm businesswomen achieving this recognition, which stem from a complex mix pertaining to their multiple roles (farmers, business owners, homeworkers, careers, community workers), limited support and recognition from others, lack of representation on industry boards, and the lack of education and resources available to support them. Personal circumstances and capacity can also be a barrier to further engagement in leadership, as can organizational issues and a lack of recognition of the skills and perspectives women have developed, and that they can bring to the industry. This research also found a range of enablers that women felt supported them in achieving their leadership goals.

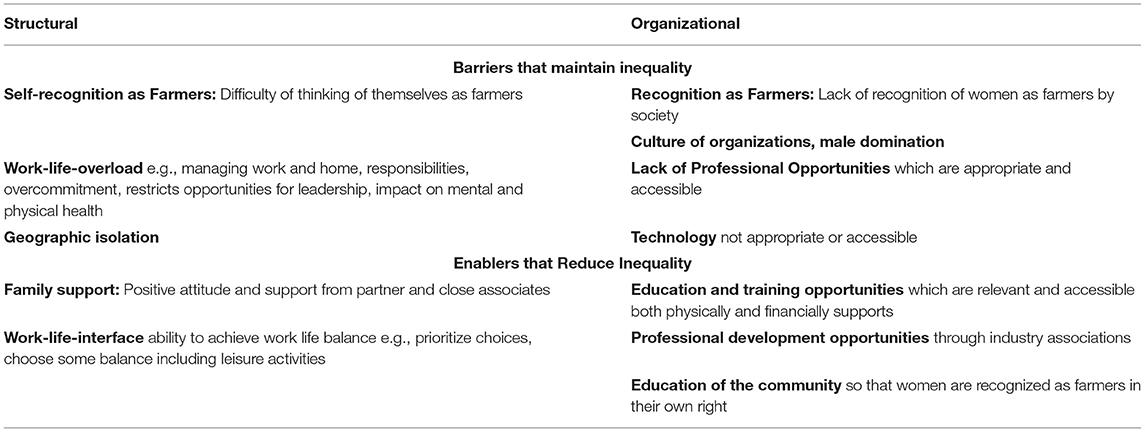

Farm businesswomen face complex challenges. While these women perform varied roles, the evidence suggests that they are not achieving the leadership outcomes to which they aspire, with many women wanting to become industry and community advocates and take on leadership roles on industry, government, or community boards Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, however opportunities for growth, development and support are needed. The barriers and enablers identified by Queensland farm businesswomen occur at an individual level and within the context of organizational structures with which they interact. Table 2 presents the themes and sub-themes that emerged, with the themes divided into two categories: structural and organizational. Using these two categories, the barriers and the enablers that maintain and reduce inequality are identified, presenting sub-themes (for example, recognition as farmers and culture of organizations) in both the structural and organizational categories.

Table 2. Barriers and enablers that maintain and reduce gender inequality of Queensland farm businesswomen.

Structural barriers that were identified by workshop participants included their lack of self-recognition as farmers, both within themselves and by others. For example, “Women who marry into a farming family/farming business sometimes do not feel entitled to identify as a farmer” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 82; see also Annes et al., 2021). One woman, who had a financial background, had married into a fourth-generation dairy farm and did not feel that she had the right to claim to be a farmer, although she was very comfortable managing the business side of the farm. Yet she still would identify as “a mum.” However, after a recent business restructure, her place was formally recognized in the farm business, and this has helped her to identify as a farmer (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 63).

In common with other workers, particularly women workers, many farm businesswomen experience work-life overload (Pocock, 2003) as they attempt to manage farm work with home responsibilities, as one farm businesswoman elaborated:

“A common problem, though, is that in most farms/properties, the women work as hard as the men, but then come inside and turn around to do all the cooking and other home-based jobs while the men relax. Women need to be more mindful of this because it actually undermines what we do and gives men permission to expect women to keep providing all those ‘services’ and to continue to perceive women as playing a secondary or support role and undervalue the core work they are doing alongside men.” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 72)

One participant linked their concern for recognition to health outcomes:

“Women's tendency to take everything on, or to try to manage every aspect of home and business life, and to need to have things done their way or to their standard … leads to over-commitment and mental fatigue. We need to own the fact that often we create our own problems when we behave like this.” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 74)

Concerns about mental and physical health add yet another barrier and supports the findings in earlier research undertaken by McGowan (2011). This can be compounded by lack of support and is “especially a problem if the women closest to you [or your] own family are not positive or supportive” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 75).

We see that women's opportunities are further compounded as some lack support in their pursuit of leadership roles and juggle the management of farm work and family roles against a backdrop of geographic isolation. While some farmers live close to towns, some, particularly in the livestock industry, live, work, and bring up their children on large, isolated properties, hundreds of kilometers from other properties. As one participant noted, “digital technology is still not sufficiently developed or reliable to overcome the tyranny of distance for rural/remote women to participate efficiently in decision-making or representational forums” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 47).

Organizational barriers add another dimension to women's ability to attain leadership roles. In wider Australian society, women may not be recognized as farmers. One woman farmer commented that “It depends on the audience. [I] have experienced discrimination e.g., [for example] from truck drivers who assume a woman can't handle the task of loading cattle and suggest she better get her husband” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 72). Visibility of women farmers in the community generally was an issue: “Having our voices in agriculture heard and dealing with all the negative messages about [and the] poor public perception of agriculture and farming” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 74) was problematic for these women, and similar to experiences of women farmers in other economies (Annes et al., 2021).

Cultural issues arise due to the gendered social beliefs about women in leadership, as well as barriers that prevent women from participating in professional opportunities such as networking and developing workplace relationships. Agriculture is still perceived as a dominantly male domain and this dominance can be seen in the predominance of men in the leadership positions in agricultural organizations (Ressia et al., 2020). This hegemonic male dominance goes beyond leadership positions as “women's ideas and voices are not always validated, especially in a male-dominated group” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 58). Women encounter a stereotype that farming involves heavy manual work and large machinery:

“Some farm women...tell us that they feel uncomfortable calling themselves a “farmer” because they aren't necessarily always outdoors or driving a tractor. There is a stereotype – a myth – that farming is only considered “farming” if it consists of outdoor manual work...” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 26)

An insightful comment from one workshop participant shows that not all areas of farming are regarded as equal. Some areas of farming, such as growing flowers can be seen as more acceptable for women, but then they may be dismissed as being true farmers:

“I have no problem saying, “I'm a flower farmer”, so I've never considered this as an issue. Is that because females are more prevalent in flower farming? Although, other farmers scoff that flower farming is not real farming.” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 80)

This confirms the predominance of hegemonic masculinity in agriculture and possibly a hierarchy in what is regarded as “real” farming, with feminized areas downgraded (Annes et al., 2021; Savage et al., 2022). Participants in one workshop summed up their experience of this struggle to be recognized as legitimate farmers:

“The image of the primary producer is a masculine image and in many ways, rural people want to protect that male image; the masculine image of the primary producer is romanticized and wrapped up in our image of “the land.” In this picture, men are primary and the women are in support roles. Women are identified as those who have babies and raise children.” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 64)

Alston (2015) asserts that gender stereotyping is a major barrier to women's involvement in leadership and decision-making positions. The ability to keep on top of technological advancements in the industry and limited access to supports such as mentors and resource knowledge through funding are barriers that stymie growth and innovation.

Women experienced other organizational barriers including lack of professional development opportunities and support. There was “poor access to opportunities for development activities or a lack of knowledge of available opportunities” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 75) and the lack of a sponsor or champion (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 75). Access to technology and the latest developments could be difficult because of geographical distance. Indeed, “the limitations around information and communication technologies experienced in remote areas exacerbated the tyranny of distance, leading to difficulties in accessing resources and facilitation in building support networks” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 20). In addition, “it is extremely challenging to keep up with rapid technological change” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 20). For farm businesswomen in the large state of Queensland, connection to others and to their customers is critical to: “Achieving enough connectivity and communication; reaching out”, and “connecting to your customer base” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 57).

Women identified a lack of resource knowledge with which to further their business and their potential leadership roles. It was noted that:

“There are not enough funds around to support women to get the skills they need to progress in business and leadership. It would be valuable for women to have access to subsidized business management/governance/leadership training/professional development – or, even better, access to scholarships/bursaries.” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 58)

Structural enablers that the participants discussed included perceptions of having a positive attitude and self-belief, being supported by their partner, and having the ability to compartmentalize the toughness of farming by taking time out to have fun in order to achieve some sense of work-life-balance. For instance, farming women discussed the importance of “Taking opportunities to rest/have some fun – because farming life is tough going” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 74). One woman further elaborated:

“30 years of farming does take its toll … you must do things to look after yourself, to achieve balance, to have some fun. Get up on the balcony and off the dance floor – it's essential to look at things from a wider perspective as often as you can.” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 74)

Women farmers said that they needed to be resilient: ‘If you are going to “put it out there” [and] put yourself in the spotlight to promote what it is to be a farming woman, you need to be prepared to cop the flack. People will comment and criticize’ (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 55; see also Annes et al., 2021). They indicated that support from others, especially those close to them, was critical: “Having a cheerleader! [sponsor] – especially when that person is your partner/close family. Who is your number one fan?” and the importance placed on partner support: “Having a supportive partner, particularly one who is willing to equally share the load of home and family work” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 74). Networks and training were also critical as “getting involved in networks that provide opportunities for collaboration, support, skills development, sharing ideas” were seen as beneficial (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 84) as was “taking opportunities to do training, skills development – especially in leadership capabilities” (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 83).

Organizational enablers focused on professional opportunities relevant in content and delivery available through industry associations enabling access to information and network supports when carrying out, or aspiring to, leadership roles. Access to both physically available and financially supported educational opportunities was important for developing business and leadership skills. This could be achieved through access to tertiary education, leadership courses and other training and development that recognize their unique requirements, for example, the needs of women who marry into farming families. Furthermore, through education, women's knowledge and management of technology has become valuable in enabling decision-making and change (Hay and Pearce, 2014).

Industry associations play a major part in training with women saying that these associations can play a key role with enabling and supporting them by providing professional development opportunities where regional facilitators can bring critical and specifically targeted information to local meetings and to share industry knowledge. Such activities would further support farm women and enable them to be engaged, stay informed and connect with other women farmers at a personal level (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 59–60). Region-specific databases of regional resources and information that facilitate networking and sharing amongst regional communities was also highlighted as needed and as a key enabler. Regional skills audits that gather key contact information could make it easier to find and connect with the right people for obtaining help and advice regarding specific aspects of farming and the broader agriculture industry (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 60).

Finally, community wide education campaigns were seen by participants as important for reshaping the image of farming women, to build a wider understanding of the role they play in contemporary agriculture. This is an important enabler, as it would work toward re-shaping and provide a broader perception of women farmers within the wider community, and for the recognition they deserve as farmers in their own right (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018, p. 58).

Discussion

The research identifies that women's contribution to the farming and agriculture sector, and to rural and regional communities has been underestimated. We know, historically, that when compared to males, women have been “invisible” and unacknowledged as farmers (Williams, 1992; Alston, 2003; Annes et al., 2021). This aligns closely with Acker's concept of the “ideal worker” and the continued hegemonic dominance of men in the agriculture industry which continue to create inequalities for women (Acker, 1990, 2006; Annes et al., 2021). The concept of the “ideal worker” has been used widely in academic literature and while this concept focuses specifically on workers in companies and organizations, we suggest that the concept of the ideal worker can be extended to farm businesses in relation to the impact inequality regimes have on farm businesswomen. The analysis revealed that these women are struggling for recognition in the shadow of their male farming counterparts. They undertake the management of traditional gender roles and so are encumbered by the responsibilities of the family and the home in addition to working in the farm business. On many occasions they are not recognized publicly for their contributions to farm management, thus rendering their work as farmers “invisible.” In this respect, we therefore extend the concept of Acker (1990) “ideal worker” by introducing the concept of the “ideal farmer” (Ressia et al., 2020) to distinguish a worker who is focused on work on the farm external to the house, without any family and/or childcare responsibilities; a worker who has been seen historically as a man with household and family work undertaken by his wife or partner. We have related this concept to the feelings of women farmers, of being the “invisible farmer” (Rasplus, 2020b, 2021; Annes et al., 2021) a feeling identified by some respondents in the (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018) (survey and discussed in the work of Alston (2015).

Unfortunately, we see the legacy of the “invisible female farmer” continuing today. The ABS recognize that using the number of individuals who report farming as their main job cannot completely measure a women's contribution, as “farming families” are officially recognized by the ABS as the main mode of agricultural production in Australia (Alston, 2015, p. 189). Therefore, women's individual contributions are still unrecognized (Alston and Whittenbury, 2013, p. 124) in multiple ways, and there is still inadequate policy and industry attention that recognize and support women's various work, care, and community roles (Alston, 2015, p. 194). Policy formation has often ignored and/or trivialized women's contributions to their families, communities, and industries (Alston, 2015) and this creates further barriers, as identified in this research, that contribute toward women farmers' inability to achieve opportunities for leadership within the industry.

We acknowledge that there is still a lack of information about the detail of women's roles on farms but we do know from our analysis that women's roles are complex. These women have a wide range of responsibilities related their farm businesses, innovation, entrepreneurship, and family care. While the barriers we identified from the workshop discussions are not new, the culture of masculinity in the industry is having an effect on women's ability to achieve true recognition as farmers, as well as opportunities for leadership. We see that what makes this issue even more problematic are the cultural norms around the image of the famer, and farm businesswomen not seen as fitting the mold of the “ideal farmer.” Combined with the impact of remoteness and their inability to access support, this creates conditions that make it more difficult for farm businesswomen in Australia to achieve their leadership goals.

Conclusions

Our research explored the aspirations of Queensland farm businesswomen and analyzed workshop notes and survey data collected by the (Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF], 2018). Together with incorporating a review of the available international literature and local academic literature, industry reports and statistics concerning women in agriculture, we analyzed farm women's experiences through the lens of Acker's inequality regimes theory (1990, 2006). The major barriers to achieving leadership positions which women farmers identified focused on the lack of recognition of women as farmers as this occupation was still seen as a male role. In addition, work-life overload and geographic isolation exacerbated their difficulties. Support from family and close associates and access to relevant education helped them. Using Acker's original “ideal worker” concept, we apply these ideas to farm businesswomen who, in Australian society, do not meet the concept of the “ideal farmer,” who is a man devoted to the farming business without any responsibilities for the care of home or family (Ressia et al., 2020). Women's roles are still seen to have a primary focus on family and therefore these women are unlikely to be seen as leaders in farm businesses and industry organizations.

The analysis revealed that there remain many missed opportunities for farm businesswomen to be fully recognized as “true farmers” (Glover, 2014) and for developing and supporting their aspirations for leadership in Queensland's agricultural industry. Similar to the experiences of women farmers in western economies, there has been little policy acknowledgment of women's roles in farming, and no recognition of the burden that this places upon women, their health, wellbeing, and family lives (Alston, 2015). Thus, the lack of recognition of their worth coupled with the complexity of managing multiple roles impacts these women's aspirations for leadership in the sector and their contributors to farm businesses.

This paper adds further knowledge about the environment within which women farmers operate and has provided an in-depth understanding of their contributions, aspirations, barriers and enablers to achieving their goals, and the key enablers including education and training and professional development needs that would assist them in achieving their business, and leadership goals within a traditionally male-dominated industry (Acker, 2006). More resources are needed to support these women for them to be equally recognized as valuable and credible contributors to industry, through the recognition of, and the breaking down and elimination of persistent inequality regimes.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

SR: writing original draft, literature review and analysis, editing, and completion of final draft. GS: conceptualization, literature review, methodology, project administration, and review and editing. KB: literature review, methodology, analysis, and review and editing. MR: conceptualization, analysis, and review and editing. RM: funding support and review. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded by the Queensland Farmers' Federation and the Department of Employment Relations and Human Resources, Griffith Business School to assist with the administration of the project.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acker, J. (1990). Hierarchies, jobs, and bodies: a theory of gendered organizations. Gend. Soc. 4, 139–158. doi: 10.1177/089124390004002002

Acker, J. (2006). Inequality regimes: gender, class, and race in organizations. Gend. Soc. 20, 441–464. doi: 10.1177/0891243206289499

Alston, M. (2003). Women in agriculture: the ‘new entrepreneurs’. Aust. Fem. Stud. 18, 163–171. doi: 10.1080/08164640301726

Alston, M. (2010). Gender and climate change in Australia. J. Sociol. 46, 53–70. doi: 10.1177/1440783310376848

Alston, M. (2015). “Rural policy: shaping women's lives,” in Rural and Regional Futures, eds A. Hogan and M. Young (Oxon: Routledge), 189–205.

Alston, M., Clarke, J., and Whittenbury, K. (2018). Contemporary feminist analysis of australian farm women in the context of climate changes. Soc. Sci. 7, 1–15. doi: 10.3390/socsci7020016

Alston, M., and Whittenbury, K. (2013). Does climate crisis in Australia's food bowl create a basis for change in agricultural gender relations. Agric. Hum. Values 30, 115–128. doi: 10.1007/s10460-012-9382-x

Annes, A., Wright, W., and Larkins, M. (2021). A Woman in charge of a farm: French women farmers challenge hegemonic femininity. Eur. Soc. Rural Sociol. 61, 26–47. doi: 10.1111/soru.12308

Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS] (2019). Labour force, Australia, detailed, quarterly, May 2018 - RQ1 - employed persons by industry division of main job (ANZSIC), labour market region (ASGS) and sex, annual averages of the preceding four quarters, Year to August 1999 onwards (Catalogue No. 6291.0.55.003). Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra.

Ball, K. (2017). Who You Know? Women engineers and informal networking in a project-based organisation in Australia. [dissertation/PhD thesis]. [Brisbane, Qld], Griffith University.

Binks, B., Stenekes, N., Kruger, H., and Kancans, R. (2018). ABARES Insights, issue 3, 2018: Snapshot of Australia's Agricultural Workforce. Report, Commonwealth Department of Agriculture and Water Resources, Canberra, Australia. Available online at: https://www.awe.gov.au/abares/products/insights/snapshot-of-australias-agricultural-workforce (accessed October 20, 2021).

Bossenbroek, L., van de Ploeg, D., and Zwarteveen, M. (2015). Broken dreams? Youth experience in Morocco's Saïss region. Cahiers Agriculture. 25, 342–348. Available online at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/fb11/5a3d4913d731b8998268dac891ae72409b95.pdf?_ga=2.153641976.1329588917.1645830355-137260541.1645830355 (accessed February 26, 2022).

Department of Justice Attorney-General (2021). Queensland Government, Brisbane. Available online at: https://www.justice.qld.gov.au/about-us/services/women-violence-prevention/women/boards/about (accessed November 15, 2021).

Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., and Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 5, 1–4. doi: 10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

Glover, J. L. (2014). Gender, power and succession in family farm business. J. Gend. Entrepreneurship 6, 276–295. doi: 10.1108/IJGE-01-2012-0006

Gornick, J., and Meyers, M. (2009). “Gender Equality: Transforming Family Divisions of Labor,” in Real Utopias Project, ed E. Wright (London: Verso), 3–66.

Hay, R., and Pearce, P. (2014). Technology adoption by rural women in Queensland, Australia: women driving technology from the homestead for the paddock. J. Rural Stud. 36, 318–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.10.002

Jackson Wall, I. (2022). What Place for Women in Agriculture in the Northern Basque County? AgriGenre, Available online at: https://agrigenre.hypotheses.org/4737 (accessed February 20, 2022).

Jefferson, T., and Mahendran, A. (2012). Calculating the paid off-farm work contributions of women in Australian agricultural and rural communities. Int. Rev. Bus. Res. Papers. 8, 191–204. https://espace.curtin.edu.au/bitstream/handle/20.500.11937/21313/190571_72472_Jefferson_and_Mahendran_2012.pdf?sequence=2andisAllowed=y (accessed October 20, 2021).

McGowan, C. (2011). “Women in agriculture,” in Changing Land Management: Adoption of New Practices by Rural Landowners, eds D. Pannell, and F. Vanclay (Collingwood, VIC: CSIRO Publishing), 141–152.

Pocock, B. (2003). The Work/life Collision: What Work Is Doing to Australians and What To Do About It. (Sydney: The Federation Press).

Puglise, P., and Quagliariello, R. (2018). Cultivating Vision and Networks to Untap Rural Women's and Girls' Potential in the Mediterranean. New Medit, A Mediterranean Journal of Economics, Agriculture and Environment. 3:Notes, Available online at: https://newmedit.iamb.it/2018/09/15/cultivating-vision-and-networks-to-untap-rural-womens-and-girls-potential-in-the-mediterranean/ (accessed February 26, 2022).

Queensland Farmers Federation [QFF] (2018). Cultivating the Leadership Potential of Queensland's Farm Businesswomen. Report, QFF, Brisbane, Australia.

Rasplus, V. (2020a). Farmer 3.0 and Female Farmer 0.0? AgriGenre, Available online at: https://agrigenre.hypotheses.org/307 (accessed February 20, 2022).

Rasplus, V. (2020b). Women Farmers in the Light of the 1970 Agricultural Census. AgriGenre. Available online at: https://agrigenre.hypotheses.org/2301 (accessed February 20, 2022).

Rasplus, V. (2021). The Condition of Women Farmers as Seen by Bernard Lambert. AgriGenre, Available online at: https://agrigenre.hypotheses.org/2607 (accessed February 20, 2022).

Ressia, S., Strachan, G., Rogers, M., Ball, K., and McPhail, R. (2020). Queensland Farm Businesswomen: The Long Road to Leadership. Report, Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia.

Sang, K., Powell, A., Finkel, R., and Richards, J. (2015). Being an academic is not a 9-5 job': long working hours and the 'ideal worker' in UK academia. Labour Ind. 25, 235–249. doi: 10.1080/10301763.2015.1081723

Savage, A. E., Barbieri, C., and Jakes, S. (2022). Cultivating success: personal, family and societal attributes affecting women in agritourism. J. Sustain. Tourism 30, 1699–1719. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1838528

Sheridan, A. J., and McKenzie, F. H. (2009). Revisiting Missed Opportunities—Growing Women's Contribution to Agriculture. Publication No. 09/-83. Report, Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation [RIRDC], Canberra.

Shortall, S. (2004). The broad and narrow: case studies and international perspectives on farm women's research. Rural Soc. 14, 112–125. doi: 10.5172/rsj.351.14.2.112

SOFA and Cheryl Doss. (2011). The Role of Women in Agriculture. ESA Working Paper No. 11-02 March 2011. Agricultural Development Economics (Rome, Italy: ESA).

Strachan, G. (2009). “Women's Pay and Participation in the Queensland Workforce,” in Work and Strife in Paradise: The History of Labour Relations in Queensland 1859–2009, eds B. Bowden, S. Blackwood, C. Rafferty, and C. Allen (Sydney: Federation Press), 146–162.

Strachan, G., and Henderson, L. (2008). Surviving widowhood: life alone in rural Australia in the second half of the nineteenth century. Contin. Change 23, 487–508. doi: 10.1017/S0268416008006942

Tchékémian, A. (2022). The Place of Women in the World of Agriculture: Between Tradition and Change. Hashes, Available online at: https://dieses.fr/la-place-des-femmes-dans-le-monde-agricole-entre-tradition-et-evolution (accessed February 26, 2022).

Keywords: agriculture, Australia, farm businesswomen, leadership, women

Citation: Ressia S, Strachan G, Rogers M, Ball K and McPhail R (2022) Farm Businesswomen's Aspirations for Leadership: A Case Study of the Agricultural Sector in Queensland, Australia. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 6:838073. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2022.838073

Received: 17 December 2021; Accepted: 17 May 2022;

Published: 20 June 2022.

Edited by:

Benoit Dedieu, Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA), FranceReviewed by:

Edo Andriesse, Seoul National University, South KoreaElena Lioubimtseva, Grand Valley State University, United States

Copyright © 2022 Ressia, Strachan, Rogers, Ball and McPhail. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Susan Ressia, cy5yZXNzaWFAZ3JpZmZpdGguZWR1LmF1

Susan Ressia

Susan Ressia Glenda Strachan1

Glenda Strachan1 Kim Ball

Kim Ball