95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Food Syst. , 15 March 2022

Sec. Social Movements, Institutions and Governance

Volume 6 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.754639

This article is part of the Research Topic Critical and Equity-Oriented Pedagogical Innovations in Sustainable Food Systems Education View all 15 articles

Undergraduate programs in sustainability and food systems studies increasingly recognize the importance of building equity competencies for students within these programs. Experiential learning opportunities in these programs often place students in internships or service learning in racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse communities. Many community-based organizations focus on youth development and empowerment through mentorship. Learning in these contexts can be mutually beneficial for mentors, youth and community organizations working in partnership toward a shared goal. Intentional preparation of mentors for these experiences is germane, particularly when mentoring youth with marginalized identities. Mentoring in the U.S. historically and currently rests on deficit-oriented discourses that position youth of marginalized identities as needing help, and that help is often provided by white and privileged saviors. Many programs intentionally or unintentionally employ assimilation models with white middle/upper class ideologies and expectations for success, which further lift dominant identities while marginalizing the youth of focus. These models also displace focus from systemic inequities, while placing blame on individuals. Building equity-based competencies with undergraduate mentors is necessary to avoid these downfalls that perpetuate harmful practices and discourses. Through intergenerational mentorship and urban agriculture, GNM works to advance environmental, social and racial justice in North Minneapolis. The GNM partnership was originally initiated by community members that wished to build pathways to the University and workforce for youth through agriculture, food systems, and natural resource sciences. In this study, we highlight results from our experience preparing undergraduate mentors through Growing North Minneapolis, an urban agriculture program and community-driven collaboration between North Minneapolis community elders and the University of Minnesota, focusing on youth and their communities. This case study serves as a model for building equity-based competencies in undergraduate programs. Our findings highlight (1) how the experience of collaborative mentoring in community-based internship for youth of marginalized identities can support the growth of undergraduate mentors and (2) how undergraduate mentors can be prepared to work with communities and youth of marginalized identities in critical ways within an equity-based framework.

Undergraduate programs in Sustainable Food Systems Education (SFSE) are emerging across many institutions of higher education in North America to address complex global socio-environmental food systems issues. Faculty and educators supporting these programs have identified knowledge, skills, behaviors, and attitudes needed by future food systems professionals to address inherently complex socio-environmental food systems issues (Valley et al., 2018; Ebel et al., 2020). Modalities of teaching, or “signature pedagogy” that address the fundamentals of a profession to students and future practitioners, have been identified for SFSE to include systems-thinking, multi-inter-and trans-disciplinarity, experiential learning, and participatory and collective action projects (Valley et al., 2018). Experiential learning activities are viewed as integral to SFSE as they integrate cognitive, psychomotor and affective domains of learning and allow students to practice collective action and transformative work.

Health and food-related inequities are disproportionately experienced by people of lower incomes and along racial and ethnic lines, underscoring the importance of understanding historic systems of oppression and bringing an equity-based approach to this work. A recent article authored by university educators identifies key domains of equity competencies for SFSE: (1) awareness of self, (2) awareness of others and one's interactions with them, (3) awareness of systems of oppression, and (4) strategies and tactics for dismantling inequity (Valley et al., 2020). Development of knowledge, skills, attitudes and practices that foster these competencies may be approached through experiential learning in SFSE. Experiential learning activities can take many forms and often include service-learning experiences, which typically include student engagement in off-campus, community-based projects with educational instruction designed to foster civic engagement and social responsibility through personal reflection on the experience (Lim and Bloomquist, 2015). However, service-learning practices have been notably critiqued as a “pedagogy of whiteness” (Mitchell et al., 2012), as these experiences often occur without proper consideration of the impacts of racism and white supremacy on under-served communities where many service projects take place. Thus, white supremacy is often reinforced as students fall into “white savior” roles, and any learning is done at the expense of communities without true benefit (Mitchell et al., 2012). Consequently, intentional discussions and reflection on impacts of systemic racism, particularly place-based and context-specific, should be integral to prepare students for engagement in service-learning experiences and are particularly aligned with the key domains of equity competencies for SFSE.

Youth mentorship programs are a form of service-learning, wherein undergraduate students are provided with preparation and guidance prior to engaging in a mentorship role with youth from marginalized communities (Hughes et al., 2012; Weiler et al., 2013). However, outcomes of these experiences are underreported in the literature. Youth mentorship programs typically claim to provide meaningful learning experiences to both mentors and mentees. Undergraduates who participated in a university service-learning course that included guided youth mentoring practices showed positive outcomes for civic attitudes and action, self-efficacy, self-esteem, interpersonal and problem-solving skills, and political awareness (Weiler et al., 2013). In another study, undergraduates who participated in one-on-one mentoring with youth from low-income communities reported increased awareness of self-privilege, social inequities, recognition of the importance of civic action, and were better able to challenge negative stereotypes (Hughes et al., 2012). In this study the majority of the undergraduate mentors identified as white and middle-to upper-middle class while the majority of mentees were black high school students from low-income families. The role of race in socio-economic inequities was acknowledged, however, based on student responses, mentors exhibited deficit views toward mentees indicating inadequate equity competencies prior to engaging in youth mentoring. Such experiences risk harming the marginalized youth they claim to benefit, as shown by the author's conclusion that these types of service-learning experiences may be more meaningful to “economically privileged” college students than students whose backgrounds are similar to that of the mentees (Hughes et al., 2012).

While there are many documented benefits of mentoring for youth of marginalized identities—for example, socioemotional growth, academic success and developing a sense of agency (e.g., Adams, 2010; Watson et al., 2016)—there are serious concerns and risks to consider. Mentoring in the U.S. rests on deficit-oriented discourses that position youth of marginalized identities as needing help (Lindwall, 2017), often provided by white and privileged saviors (Baldridge, 2017). Many programs intentionally or unintentionally employ assimilation models with white middle/upper class ideologies and expectations for success, which further lift dominant identities while marginalizing the youth of focus (Weiston-Serdan, 2017). These models also displace focus from systemic inequities that need addressing (Weiston-Serdan, 2017), while placing blame on individuals (Noguera, 2009).

Wellintentioned outsiders may be limited in their understandings around important issues related to culture, identity and oppression. Mentor training in cultural competency has been leveraged to bridge these issues, however, such trainings are often limited in time and depth (Lindwall, 2017). Consequently, there are many mentors from privileged and white spaces working with youth and communities of marginalized identities, who are underprepared to do so effectively and responsively. This raises important questions around preparing mentors from dominant backgrounds to work with youth and communities of marginalized identities.

While research has provided some helpful guidance in preparing mentors (Lindsay-Dennis et al., 2011; Hughes et al., 2012), more research is needed in this field, particularly related to preparing mentors to work effectively with youth of marginalized identities. While research often focuses on youth outcomes, we must better understand the experiences and growth of mentors, and how to best support them. Additionally, research has not yet examined the particular challenges and opportunities in preparing mentors for community-engaged work, including the valuable role of community partners. In these spaces, there are sometimes unique opportunities for partnership, including intergenerational and collaborative mentoring, both of which are underexplored. Our study sought to address some of these gaps in the research literature by focusing on the experiences of our university mentor participants, the impact of our preparation strategies, and the nuances of preparation for community-engaged work, including the opportunities for collaborative preparation and collaborative mentoring with community elder mentors. This work is situated in an urban food systems context within our Growing North Minneapolis summer program and discusses how this work builds key equity competencies identified for undergraduates in Sustainable Food Systems programs.

Specifically, we explored the following research questions:

• How does the experience of collaborative mentoring of youth of marginalized identities support the growth of undergraduate mentors?

• How can undergraduate mentors be prepared to work with communities and youth of marginalized identities in critical ways?

The framework for our study comes from Torie Weiston-Serdan's (2017) critical mentoring. Critical mentoring rests on the belief that young people are natural revolutionaries, and challenges deficit-oriented notions of mentees. It shifts the paradigm from hierarchical mentoring relationships to participatory, emancipatory and transformative.

Weiston-Serdan acknowledges that youth, particularly youth of color, are living in racial, social, and economic toxicity. Mentoring needs to address and transform these root causes of contexts and systems, as well as treating the symptoms (i.e., academic performance, behavioral performance, etc.). Weiston-Serdan's critical mentoring rests on the central components of critical race theory to inform the central components of mentoring—to address and transform the toxic contexts in which youth live. In effect, critical mentoring supports counter storytelling, by youth and mentors, to counteract the metanarratives that are deficit-oriented, often positioning adults as saviors and youth as in need of saving. Critical mentoring incorporates difficult conversations around race, gender, class, sexuality, and ableism.

Weiston-Serdan advocates for youth centrism in mentoring, stating that “Young people have shown us time and time again that they are sound and substantial partners and leaders; it is us who refuse to recognize them in that way and who default to deficit notions of operating” (p. 25–26). Young people are at the center of critical mentoring; they must inform the work, and they must have voice, power, and choice. Critical mentoring intentionally incorporates the key components of cultural relevance—to help mentors understand how to center and use cultural assets of young people to drive meaningful experiences and engagement.

This case study takes place within the greater context of a program called Growing North Minneapolis (GNM), which is a community-driven collaboration between North Minneapolis community elders and the University of Minnesota (UMN), focusing on youth and their communities. The GNM partnership was originally initiated by community members who wished to build pathways to the University and workforce for youth through agriculture, food systems, and natural resource sciences. The design of GNM comes from the firm belief that the North Minneapolis community is full of cultural assets and has rich skills and experiences in urban growing and food systems and the university can provide support with additional knowledge, skills and resources in agriculture, horticulture, and youth development.

While GNM has both a summer internship program and a school-year program, this study and context focuses exclusively on the summer internship program and related mentor training course. The summer program is an urban agricultural and environmental internship program for 14–15-year-old North Minneapolis youth of marginalized identities. This study took place during the third year of the GNM program. During the summer of 2019, 36 youth participated in the 9-week summer internship. Each group of six youth was paired with one community elder mentor and one UMN undergraduate mentor, and each group was responsible for two to three community gardens. The six UMN undergraduate mentors are the focus of this particular study. These intergenerational garden groups spent the summer growing and caring for gardens in their community, developing career skills, and learning about related topics related to agriculture and environmental sciences in contextualized ways (Livstrom et al., 2020).

Prior to the summer experience, the undergraduate mentors participated in a 7-week preparation course—Critical Mentoring in Partnership with Community—designed and led by the first and second authors. The course was designed after the first summer of GNM in response to challenges experienced by the first cohort of undergraduate mentors in working across differences, deficit-oriented thinking, and white saviorism mentalities (Livstrom et al., 2018). The course was designed based on an interplay of practical findings from the first year's program, discussions with youth and community, and critical mentoring literature (e.g., Lindwall, 2017; Weiston-Serdan, 2017).

The course was aligned with the critical mentoring framework (Weiston-Serdan, 2017). The first part is to critically explore the toxicities of the world that young people of marginalized identities are growing up in. The progression of the course challenged undergraduate mentors to critically analyze and reflect upon the roots of colonization in agriculture, food systems, education, and academic knowledge production (see Supplementary Table 1). Systemic inequities and institutionalized racism local to their communities and nationally, such as redlining practices and the New Jim Crow in our criminal justice system, were also explored. Next, in alignment with Weiston-Serdan's (2017) youth centrism, the mentors were encouraged to dive deeper into youth identities and intersectionality (Hooks, 2014; Weiston-Serdan, 2017), and power, privilege, and Whiteness (e.g., Baldridge, 2017; Picower, 2009). Lastly, in alignment with the critical mentoring framework, the course moved forward to culturally relevant pedagogies, critical pedagogies, and funds of knowledge (e.g., Ladson-Billings, 2006; Paris, 2012). The undergraduate mentors discussed and applied these ideas to community and youth work and in designing learning activities.

Youth centrism, critical theories and culturally relevant pedagogies were embedded throughout the course materials. Course materials included a mix of slam poetry by youth and people of color, TED Talks, podcasts, interactive computer explorations and academic articles. Course materials, including Critical Mentoring: A Practical Guide (Weiston-Serdan, 2017), were selected prioritizing the voices and perspectives of youth and adults of color.

There were seven in-person course sessions, each lasting 2 h, which met in the North Minneapolis community. Course sessions included interactive activities and discussions around the course material, as well as workshop sessions around youthwork, culturally relevant mentoring, community-engaged work, and garden-based lesson planning. The workshop sessions were sometimes facilitated by outside partner experts. Intentional within the design of the course, community mentors attended the majority of course sessions. This supported relationship building and intentional discussion between undergraduate mentors and community mentors. The course was kept small, to six undergraduate mentors. A course of this nature needed to be small in order to adequately support the students through the intensity of the material, intellectually and relationally. Additionally, the course instructor also had the responsibility to maintain the physical and emotional wellbeing of community partner participants.

In addition to weekly reflections, course experiences and assignments included: the initial design of youth workshops, a personal mentorship plan, and community hours. The workshops and community hours were added in the second iteration of the course. The undergraduate mentors each designed two workshops—one focused on a career development topic and one focused on a more technical agriculture or environment related topic. Workshop topics were predetermined by community mentors; undergraduate mentors chose topics they were interested in from the list provided. The mentors completed at least 30 h of work in North Minneapolis with community elders prior to the summer program. These hours allowed the mentors to build further relationships with the community mentors, to spend time in the community, and to contribute to gardening preparation.

This study employed an explanatory, single case design. The case was bound by the 2019 Growing North Minneapolis undergraduate mentor preparation course in combination with summer mentorship program. Case study was chosen because this methodology offers local, ecological validity and the unraveling of meaning in context (Yin, 2017). As an explanatory case study, we sought to explain how undergraduate mentors can be prepared to work with youth and community of marginalized identities in critical ways.

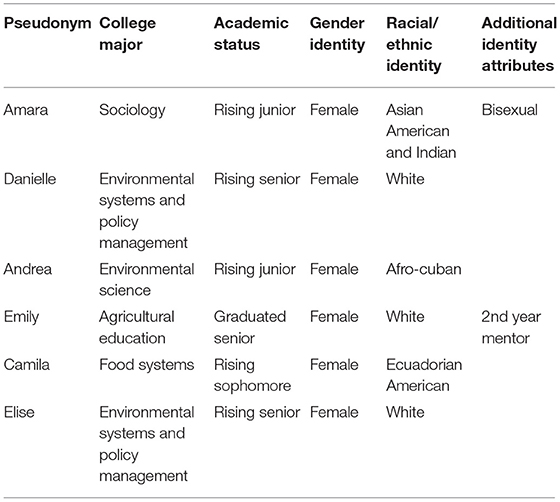

All six undergraduate mentors from the 2019 Growing North Minneapolis summer cohort were selected to provide depth into a variety of experiences. Information about the undergraduate mentors is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Undergraduate mentor participants (names anonymized) in Growing North Minneapolis program, 2019.

Primary data sources included weekly reflections during the preparation course, weekly reflections during the summer program, mid- and post-summer semi-structured interviews, and field notes with reflexive memoeing. Mid- and post-summer interviews and weekly reflections served as the primary data sources. Interview protocols were developed using Merriam and Tisdell (2015) guide to good interview questions and recommendations from Rubin and Rubin (2012). Interviews were designed to illuminate how participants were experiencing their summer program, with particular attention to challenges encountered and growth and learning. Weekly reflections during the course were open-ended and encouraged the undergraduate mentors to reflect on the course material and their own development through engagement in the material. Weekly reflections during the summer were also open-ended and designed to elicit information about the learning experiences as they were happening; what was working and not working, how their young people were responding, growing and developing, and overall challenges and success. Field notes were used as a secondary and supporting data source. They were recorded by the primary author during the preparation course, at pre-program meeting sessions, post-summer meeting sessions and 2 weekly meeting sessions during the summer.

Analysis of primary data sources (interviews, course reflections and summer reflections) were guided by constant comparative methods, involving iterative cycles of coding and comparison (Saldaña, 2015; Creswell and Clark, 2017). Interviews and written reflections were then analyzed through iterative cycles of deductive and inductive coding (Clark and Creswell; Saldaña). Deductive coding was rooted in the theory and literature around critical mentoring and working with youth and communities of marginalized identities. These deductive codes were used to develop an initial codebook to guide data analyses. Inductive open coding allowed themes to emerge organically from the participants. Coding was completed by the first author using Dedoose qualitative coding software to increase reliability in data analyses (Lincoln and Guba, 1986). Field notes were triangulated and analyzed to provide contextual data and to support and challenge already identified themes (Lincoln and Guba, 1986).

The findings are organized by research question. First, we address research question 1, How does the experience of collaborative mentoring of youth of marginalized identities support the growth of undergraduate mentors? through the presentation of themes related to the growth of knowledge and dispositions undergraduate mentors developed through the combination of their experiences. The findings begin with growth during the mentor preparation course and then growth during the applied summer program. Within each theme, connections are made to the second research question, How can undergraduate mentors be prepared to work with communities and youth of marginalized identities in critical ways?, by sharing specific experiences the mentors attributed as creating opportunities for growth. A summary of themes is provided in Table 2. Building off these thematic findings, in the discussion, we consider the second research question and the ways in which undergraduate mentors can be prepared to work with communities and youth marginalized identities in critical ways. Our findings are limited by our small sample size, as we sought for depth in understanding and transferability, rather than generalizability. Thus, we invite readers to make connections and applications between the elements and implications of our study and their own work. We do not claim that our findings can be generalized to broader settings or larger groups.

Growth during the preparation course focused on themes of sociopolitical and sociocultural consciousness; identity and intersectionality; from deficit to assets-based thinking; youth centrism; and culturally relevant mentoring.

An important area of growth the mentors reported, taking up the bulk of their weekly reflections, was related to sociopolitical, sociocultural and critical consciousness. This theme includes sub-themes of: embracing issues of equity and diversity; learning from people of color; deconstructing stereotypes and biases; and unpacking whiteness and white saviorism. Particularly through the audiovisual resources, the mentors built new knowledge about global and local issues, like systemic racism, redlining, power, privilege, and reparations. Some saw this as a first step on their journeys to being responsive youth workers. Andrea reflected her growing understandings about present day systematic racism and the new Jim Crow,

It baffled me that the “justice system” was like an assembly line bringing people of color into jail en masse. It made me think about how the war on drugs became a systematically racist and politically-driven vehicle that circulated the idea that people of color were druggies, dangerous, irresponsible, incompetant, etc. While a white person consuming drugs was pitied and given help via treatment, the person of color was given years, sometimes decade-long sentences for mere drug possession.

Danielle reflected on learning about power, privilege, and representation from Marley Dias—a 6th-grade African American activist and feminist. She said,

What resonated with me the most was her talking about having to raise money to get books featuring African American people, specifically girls. As a white woman, I have a major privilege. In this case, it manifests in being able to have as many books as I could possibly want that represent me. This is extremely sobering to realize that people do not see themselves in everyday books and stories...

Danielle's words also highlight the importance of learning from diverse perspectives, typically not represented in traditional education spaces.

Elise wrote about her learning around reparations from Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The most important theme from this piece is that present-day America is (trying to) address racism, but is doing a terrible job at it because we are completely ignoring the history of violence, inequity, oppression, exploitation.” Danielle expressed the importance of learning about issues close to her communities. She explained, “Sometimes I find it easy to imagine that things are happening far away from me, instead of in the places that I spend time. The redlining maps were an eye opener because they showed visually how inequalities manifest within Minneapolis.”

All mentors wrote about their journeys in embracing material, discussions, and work around issues of injustice, equity and diversity, which some of them had largely avoided in the past. To guide their thinking, they found the most value in the TED Talks and slam poetries. For example, Elise reflected a powerful TED Talk and how it helped her grow,

The Color Blind to Color Brave TED Talk really resonated with me because I've been in so many situations in which race is brought up and people automatically get very uncomfortable. This is so important because I want to be the person more intentional in recognizing race in these situations and help realize the strengths and power of diversity.

Andrea showed curiosity and initiative to keep exploring as she was exposed to issues of equity and diversity. She wrote, “Watching the first video dropped me into a rabbit hole of videos on creative expression of racism, white privilege, being a black woman. It was enlightening; things I've heard before seasoned with individual personality and experiences of the poet.”

Each of the mentors reflected on the TED Talks, podcasts, and slam poetries from people of marginalized identities. They appreciated the representation in voices delivering the content, the personality, the emotional charge, and the sharing of lived experiences outside of their own. Amara shared “The slam poetries were ethnically centered and moved me deeply. We have a very limited view of how we see people of color. America shows controlling, racialized stereotypes so there are false narratives defined for people of color.” Camila relatedly wrote on learning about the lived experiences of Muslim and Black identifying individuals,

The poets provided a raw and emotional depiction of racism and inequalities as a non-white person living in the United States. The two Muslim poets noted that people believe they are protecting the world from terrorism behind their computer screen when in reality they are terrorizing Muslim and Arab people for simply existing. In the slam poetry titled “Cuz He's Black,” the poet described being questioned by the police like “mine field” and “war zone” because one wrong move can be detrimental. I cannot imagine the reality of being told as a child why white people may not like you or having to painfully attempt to explain uncontrollable and racist realities to a black child.

Through audiovisual content of diverse representation, the mentors were able to explore—intellectually and emotionally—lived experiences outside of their own and important to their work. This contributed greatly to their growing sociopolitical, sociocultural, and sociohistorical understandings and consciousness.

Largely through exposure to diverse voices in representation of material and emotional connection with the poets, writers and speakers, the undergraduate mentors wrote about experiences in challenging their own pre-existing stereotypes and biases. Andrea reflected on the stereotypes of the North Minneapolis community, and the importance of not falling into these. She expressed, “I have a lot more to learn about North Minneapolis and the history that makes it what it is today, and the importance of never assuming someone's history or perspectives. I fear this creates unbalanced, uneducated relationships and interactions.” Elise wrote about power, storytelling and stereotyping,

We don't always have the capability of knowing every nuance of everyone's stories. Stereotypes are the things we hold onto because for some reason it is easier for us to find differences between ourselves and others. This is so relevant to structural and institutional racism because the people and institutions in power have used these stories of difference to divide people. It will be important to be aware of the stereotypes that exist and challenge them through sharing multi-dimensional stories.

Camila reflected on the importance of embracing discomfort and deconstructing biases, particularly after viewing an impactful TED Talk. She wrote about her past response to uncomfortable situations and her future plans:

Myers claims we all hold biases and it is important to look within ourselves in order to be willing to change. I was moved by her guidance about speaking out to benefit future generations. She gave the example of an aunt, uncle or grandparent saying an offensive or inaccurate term or stereotype at the dinner table. Rather than not commenting on it, people should correct those inaccuracies because children are also sitting at that dinner table. This has certainly happened in my family in which racist and inappropriate statements were made, yet the adults would not give a counterpoint. In the future, I plan on being more aware and reactive when incidents of silence occur in my family.

The mentors not only explicitly embraced reflections and discussions about equity and diversity regularly throughout the course, but also made commitments to do so moving forward with their young people and in their lives more generally, showing a growth in dispositions.

Inspired by a few articles, in conjunction with slam poetry, the mentors wrote about their developing understandings of Whiteness, colorism, white privilege and the dangers of white saviorism. Some of the mentors wrote about developing understandings of Whiteness. Amara reflected “The slam poetry was powerful. They talked about wanting to be white. Whiteness is the ideal type in America. People of color are marginalized and not considered beautiful. When I was a little girl, I wanted to be white.” Camila also wrote about White superiority and colorism, heavily impacted by the slam poetry selections,

I enjoyed seeing the two poets regain their confidence in their skin color. Their words were powerful—that they must “bathe in bleach” because their “skin was dirty.” This is a metaphor of white washing in American society in which Caucasian features are unfortunately deemed as most appealing due to institutionalized racism and mass media.

After engaging in slam poetry, Danielle reflected on her own White privilege. She wrote, “Black folks, and folks of color are at a disadvantage from the time they are born. No matter who you are, having white skin allows you freedoms and opportunities that others do not have.” Emily wrote on her developing understandings around White privilege in our educational systems and how this enabled her to remain unaware of important issues. She reflected,

I have also always incredibly benefited from the immensely obvious white-culture of the school system I was in, and my views had never been challenged; instead, the minority groups in my school always had to acclimate to my norms, instead of me having to expand my mind to understand the different background they had. I remained ignorant of other cultures and remained in a cozy bubble of privilege. My peers in minority groups, to the least degree had to understand white culture, and were potentially permanently impacted by the need to assimilate into a culture that forced them to have no other option.

Emily demonstrates growth by acknowledging the lasting impact of growing up in a White supremacist society for both White people and people of color.

Amara reflected on an article on Whiteness and working with communities of color, and checked her own saviorism mentality that she felt she came in with. She wrote, “I learned that when working with youth, it is important to know that you are not saving anybody. The youth are not deficient. They are here to learn and they come with many rich experiences that I should incorporate.” Amara's words demonstrate an important shift in thinking about her role—as one of a savior to a learner. Emily's reflection also shows a recognition and shift in her thinking around mentoring and saviorism. She wrote,

I have grown up seeing the white person helping to ‘lead troubled youth’ out of their ‘misguided worlds’. Therefore, I, and many Americans, have been exposed to the idea that a mentor, particularly a white mentor, fulfills their role by taking these ‘at-risk’ youth, engaging with them as their ‘special projects’, and helping them through their hard times through their ‘all-knowing leadership’.

Through the course material, mentors made important growth in their understandings around Whiteness and connected these understandings to their plans for approaching their upcoming work with young people of color.

Much of the learning about systemic racism and whiteness, while building sociopolitical and sociocultural consciousness, prompted student reflections and questioning their own intersecting identities and positionality. Some mentors wrote on the concept of intersectionality, which was brought up in their critical mentoring book. For example, Andrea wrote,

There are so many non-race related aspects of identity that are unexplored and misunderstood, ignored and demonized. Incorporating gender identities and sexual preferences that are social taboos, compounded with one's race and socioeconomic identity and age, into the critical mentoring scope makes it so much more complex than I was originally learning it to be...Critical mentoring goes deep into the nitty gritty of what it means to be a human, especially a marginalized one.

Emily specifically reflected on the Whiteness of her identity and experiences, and what this might mean while working with youth of color. She wrote,

I have the potential to be a good mentor for students of other ethnic backgrounds, but there are many things I need to check myself on each day...I think the root of healing comes from acknowledging, not actively ignoring, the plain and simple truth; for me, that will be expressing the obvious fact that I am a very white woman, and I come from a different background than these youth.

Some mentors reflected more specifically on their developing understandings and wonderings about their own identities and roles given their positionalities. About the course in its entirety, Amara said in an interview, “It showed me what my role was. Without it I don't think I would've had the right initial mindset. It's provided me with good information, like, not having this savior complex, which to be honest, I totally had.” Others questioned their role, given the material they had been exposed to. Elise wrote, “The materials also raised a big question—what is my role, as a privileged, white female, in empowering black communities, especially minority youth, to exercise their power against the injustice that they face?” Emily spoke further on this concern, particularly on issues of assimilation and success. She wrote,

I have been thinking about how one may struggle to offer productive means of mentoring a marginalized youth in an incredibly white-driven system. Past papers acknowledge that trying to uplift marginalized individuals can be counter-productive, because lifting them up, in certain ways, can be trying to make them comply to what it means to be successful in a white, capitalistic society. However, it is difficult to not do this to a certain degree, because complying to such standards is what allows a person to exist in this society.

Through the course material, particularly the course articles, undergraduate mentors became aware of their own deficit-oriented mindsets around particular issues and began transitions into asset-oriented mindsets. Emily reflected deeply on the deficit-oriented ways in which society and media portrays and treats Black youth and the need to see Black youth for the wealth of knowledge and experience that they hold. She wrote,

Black students are not to be treated as a completely different entity, as such movies suggest; they are complex individuals and their experiences, no matter what they have been, earn them unique wisdom that they can share in a cooperative partnership with their mentor. Youth possess incredibly wild amounts of knowledge, creativity, and ingenuity that mentors can frequently lack. They do not deserve to undergo their mentor's ‘white savior’ complex. I couldn't have said it better myself when the blog post closed with: “Mentoring Black youth is an honor, and it deserves to be treated as such.”

After reading an article about deficit thinking, Amara wrote about transitioning away from deficit-oriented thinking when working with young people and communities of color, inspired by an article about working with Black youth. She wrote, “not looking at black youth as “problem kids” that are “trying to make it out” is super important. We do not know anything about them and we have to keep an open mind, literally.” Reflecting on that same article, Andrea also wrote about shifting her mentality,

One thing that popped my bubble was not to have the mentality to help them “make it out” of their situations. That very mentality is horrible because it tells the youth that the context that raised them and gives them identity is something bad to run away from. This was extremely useful advice to me because I had this mentality without knowing it.

Andrea continued to write about her shift toward assets-based thinking, “I also learned that culture and ethnicity can work to bond strangers who then carry the weight of the struggles by the people they identify with.” Elise wrote on her intentions moving forward toward assets-based mentoring. She reflected,

Youth, especially minority and marginalized youth, have so much knowledge and experience that gets suppressed with institutionalized racism and segregation in schooling. Youth are not being seen or heard. As a mentor, it is so important to provide a space for youth to be seen and heard, to be engaged and challenged. I am going to work on my listening skills to truly listen to understand, not just listen to listen. I really want to encourage my mentees to tell and share stories because stories hold so much power.

The mentors' reflections illustrate important growth toward assets-based, youth centric, dispositions. They demonstrated a shift in power dynamics from mentor to mentee as a valuable holder of knowledge, experience, and contribution.

Building on their developing assets-based mindsets, the mentors grew into mindsets of affirming the power in young people and planning to center the young people in their experiences. They built these indirectly through the powerful clips of youth voices, and directly through the concept of critical mentoring. Some mentors wrote about learning from and being inspired by the young people. Emily wrote,

The content reminded me how powerful youth are, and that they hold so much potential on their own...Seeing the momentum one young person can have on the world, particularly a young person who has already articulated experiences set-backs due to institutionalized racism, I'm in awe. I also think of the potential that was in so many kids like Marley, but who were suppressed due to the current educational system, instead of lifted up from it. It is an immense loss to society.

Other mentors reflected pointedly on the concept of youth centrism. Camila reflected on the concept and connected it to her own childhood experiences. She wrote,

I learned about youth centrism which is the concept of putting youth first in an organization...youth are more influential than adults give them credit for. When I was in elementary school I admittedly had so much more motivation and courage than I do now. Perhaps this youthful self power diminishes over time due to adults rejecting rather than fostering creativity and bravery.

The mentors' reflections on youth centrism demonstrate continued growth in their knowledge and dispositions around mentoring that builds from youth assets in a horizontalized way that centers youth as the stakeholders in the work.

All of the mentors reflected on their growing understandings of culturally relevant mentoring, a key component of critical mentoring, particularly toward the end of the course. Andrea reflected on the importance of the articles in combination with exposure to youth voices from many identities, “I learned in the past 6 weeks the importance of making sure that mentors/teachers take into account the identities of every individual youth and use them as a source of knowledge with which to connect the lessons.” Camila shared her understanding of culturally relevant mentoring, “I learned about cultural relevance which is three ideas of academic success, cultural competence, and critical consciousness. I thought the cultural competence aspect was interesting because it focuses on using a students' culture as a drive to learning.” Danielle wrote about her own realization around culture and learning, “I never thought critically about the way cultural differences may impact students' learning. This is important to think about when creating content and super helpful as someone who is going to mentor folks who have different backgrounds than me.” While theory to practice is a whole different process, the mentors made significant growth in their knowledge and perspectives around critical mentoring, inspired by articles on the subjects in combination with youth voices from slam poetries and video clips.

Wow, I went from Growing North to my last year of college and I learned so much less in college. I would go into classes and I would have focus problems. I would have issues with learning anything genuinely. And this summer, I did the same internship, and I've learned so much more about plants, soil, interacting with people, so much more knowledge than I did in my last year at a big university. My last year of college I was thinking, like there's something wrong with my head. I just can't learn anymore. Then I went to Growing North and was like, oh no, I'm learning fine. (Emily)

Data analyses of interviews, weekly summer reflections, and field notes revealed important themes related to mentor's growth in knowledge, dispositions and skills related to critical mentoring during the summer program. These themes included: sociopolitical and sociocultural consciousness; personal awareness of positionality; community knowledge/cultural wealth; collaborative mentoring, working across differences and intergenerational learning/learning from diverse perspectives.

Building on knowledge built from the course materials and experiences, the mentors continued growth in sociopolitical and sociocultural knowledge, particularly in moving their understandings from theory to practice and in challenging negative narratives and stereotypes.

While the mentors grew significantly during the course in their socio-political understandings, many of them spoke about the importance of bringing this knowledge into a reality filled with layers of experience, history, humanity, and emotion. Danielle spoke about learning about systemic inequities and intersectionality through her experience,

I realized how different, like even within North Minneapolis, their inequities are. There's so many intersecting parts of a person's identity that each person's experience is so different than the other...this summer we had conversations about, like, what it meant to be the child of immigrant parents and how that experience of being like a black female is different... I knew that, but when you go to a neighborhood, you experience it.

Amara shared the importance of experiencing the humanity behind the sociopolitical issues she learned about through the course and through her sociology major,

I've grown in that I'm learning that the youth have and want a lot of agency in their lives. And, I forget to think about that...we talk about it in sociology in a very like Black people, Asian people, White people kind of way. And then you forget... there are actual people behind there. It's another thing to go into your community and to people and see what they actually think about the world and how they want to change it.

Andrea shared how working with her group of young people supported her understandings around the sociopolitical realities of their lives. She described a particular learning experience,

David...he's a big talker and he's definitely got a mouth on him. When we were talking about code switching... and we all came up with a list of people that you would need to code switch with... then you introduce the question and they talk in that way. One of them was police, and so it was David's turn to interview his partner. He was like, oh, I'm not even going to say nothing...I'm just going to be quiet. They already won. They already won before I did anything.

While the mentors had learned about inequitable policing practices and police brutality, hearing from the youth brought an entirely different learning experience—with personal connection and emotional charge.

Elise reflected particularly on learning sociopolitical and sociohistorical realities of trauma and the impact of trauma on the working community. She said,

When the group comes to the table, they bring their trauma with them. And that may be why there's arguments and blow ups and all this stuff. And so it just made me realize how much, like how much more complex issues of race and justice and historical trauma...and how much that plays into how people are and how they work.

Elise's experience and reflection speaks to the value, albeit challenge, of working with community mentors of identities, histories, and experiences completely different from her own. Through this, she developed understandings around sociopolitical histories and realities that she would not otherwise have access to, apart from a theoretically oriented distance through courses.

In their mid- and end-of-summer interviews, all of the mentors spoke about the negative stereotypes that are placed on the North Minneapolis community and youth. They shared the processes of challenging their own stereotypes and biases, and significant issues of others' stereotyping youth and communities of color. Elise reflected on her own processes of opening her mind to the beauty in the community beyond the stories she had heard previously. She said, “The picture of what North Minneapolis was painted like unfortunately was not the best. And I've been realizing how wrong that is and how you can't make judgments about certain communities without actually being involved in them.” She continued to speak to the importance of moving beyond the single-story narrative about the community, and the importance of understanding different and valuable ways of being in spaces that can be subject to external judgment without understanding. She explained,

There's a lot of inclusivity and community and I think the community aspect looks a lot different here than it does other places. Everyone comes out in the street and jokes around and has fun together… not like, I'm gonna say hi to you from across the street or the picket fence. I think, as an outsider, it would be hard to understand because that's how the media portrays it…. like, you're loitering or up to no good.

Elise's words demonstrate a depth of sociopolitical understandings around stereotyping and media depictions, as well as cultural understanding and appreciation for different ways of being.

Amara spoke more specifically about moving past her own unconscious biases around black men, through working with her group of five young black men. She shared, “We had conversations in onboarding about how society stereotypes young black men...being around young black men, I've gotten to know how sweet and smart and sensitive they are... it's helping me engage with other black men…” She moved on to talk about how she wishes others would approach young black men. She said, “I worked with five young men, so they've been stereotyped as like, you know, violent and hyper masculine and not treating women well. …they all love and adore their moms. And, they all treat us with so much respect.”

Coming into a community space as an outsider, particularly as an outsider from the university into a community of color that has been harmed by the university, is difficult work. This was a difficulty that undergraduate mentors consistently worked through and reached out for help throughout the summer. While it's not an area that any outsider can master, all the mentors grew in their consciousness of their positionalities and the intersecting identities they brought with them. Camila reflected on her developing understanding of how to be in the North Minneapolis community space. She said,

I'm just here to learn from others...like I just appreciate the work that everyone else has done and I'm not trying to take over...I realized that I'm not fully, like, a citizen of North Minneapolis. Mama Athena said it in a way that was much better—like you just have to come in here, like, wanting to understand people. Otherwise no one's going to trust you.

Camila spoke to a sentiment that all the mentors shared—that they were not there to take over, but instead there to help and support a vision and program already doing good work. Aware of their positionalities as university-identifying and aware of the appalling history of harm to the community by the university, they wanted badly for the community to understand that they had no desire for power.

Building on the understanding of self as a supporter, rather than leader, most mentors spoke about building awareness through listening and navigating their own voice in the space. Elise shared,

I learned something every single time we have a group meeting. It's just, to go in with open ears and kind of digest it as it comes. It is challenging to work with, cause I don't know, when is appropriate to insert my voice, you know? I've been really working on listening and now finding the balance of listening but also being able to—voice your perspective. And I don't think I always feel super comfortable doing that being who I am, you know, and like based on my identity in the space that I'm coming into.

Elise's developing thoughts and actions show important growth in awareness of self and positionality related to community-driven work. Danielle also shared her process of relinquishing the control of always needing to have a voice and to respond to everything said. She explained, “It's easy to get riled up about things and wanting to talk. It's important to listen to what everybody has to say...this group has taught me to listen without reacting and not come up with my own rebuttals.”

All of the mentors—throughout the summer, in reflections, and in interviews—spoke about the beauty, depth and cultural wealth of the North Minneapolis community and community mentors, and about ways in which community work differs from university work. In this, they built an awareness and understanding of the value of knowledge and skills and cultural wealth outside of traditional University understandings of wealth and knowledge. Amara shared her thoughts about the overall value of having community mentors on the team and supporting the mentors, “Having community folks ground us and tell us how it's important and they're always here to support us. They bring themselves and they bring their stories and that's very impactful because it makes them.” Danielle reflected on the cultural assets and strengths of the community, community mentors, and how the community engages in work together,

Something that I've seen a lot is how the community works together to help one another. Like, when something happens everyone's out and asking you what you need, which is something that I don't find in other communities...And like the resiliency thing, just being able to like find resources and figure out things when they're not like given resources from outside people. They're able to figure it out...like you ask somebody in our group for something and they're like, well I don't have it but I'll figure out a way to get it.

Danielle's words show a growing understanding and appreciation for the cultural wealth of the community and community mentors—of working together, supporting one another and resourcefulness. This recognition is important, especially when traditionally white spaces, like universities, so often value things like individualism, efficiency, and economic wealth. Similarly, Andrea spoke to the power in the North Minneapolis community—in coming together and supporting and caring for one another and the community as a whole. She said,

It's exposed me to how much the community cares about itself...seeing people recognize the injustice of not having fresh food around, not having really good education systems, not having a safe place for their children to walk outside. The fact that they're trying to come together and unite and create a better tomorrow for their kids is really cool...

The mentors' reflections on the community and community-driven work show a deepened understanding of the North Minneapolis community, built through their hands-on experiences of working in the community and in collaboration with community mentors. Their reflections demonstrated a growing understanding of and appreciation for the cultural wealth of the community and the way the community worked together and advocated for justice.

All the undergraduate mentors spoke about the value of their community mentor partners' knowledge, skills and perspectives, and learning from community mentors through collaborative mentoring. They learned about gardening, working with young people, working in the community, and about identity. Danielle reflected on the new experience of working alongside elders rather than people her own age,

I never worked with community elders anywhere before or even like older people. It's always been like peers, my own age and interests. It's been fun for me to get to know the elders and see how much knowledge all of the elders have to bring. They've taught me so much about North Minneapolis being a person honestly, just like knowing my identity.

Elise also spoke about how the community mentors brought their whole selves, which encouraged her to do the same. She said, “They're so different. I learned to, like, be yourself, and be cool with that. They are all so much themselves and it's awesome. They don't conform to the space that they're in.”

Danielle shared how she learned from her community mentor about working with young people, specifically in prioritizing the young people over the garden work. She explained,

I think Joseph is really good at like seeing—cause I get like too focused on the garden, but he's really good at seeing like when somebody is having an off day and that'll go over my head, because I'm so focused on like the actual like work. He helped me like check-in on the person. It makes me realize like, Oh yeah, I need to step back, slow down and like make sure that everybody's doing okay and understanding.

Amara also reflected on learning from her community mentor about working with youth and encouraging them to build on their strengths. She shared, “When people are being particularly defiant, she's like—you know you're a leader right? People follow you. She's complimenting and telling them they gotta do stuff in positive ways...She sees the human and really brings out strengths.” Amara felt that she received similar care and support from her community mentor partner as the youth. She said, “She's always encouraging me...if I make a mistake, she's not on my case about it. She knows that I'm growing as a person too...”

A few of the mentors spoke specifically to the sociocultural knowledge, history and experiences community mentors brought, as well as shared lived experiences to the young people, all of which they were able to learn from. Emily shared,

He would just be blunt about a lot of things about racism, about systemic issues in North Minneapolis. He would bring up tough things about, like, gangs and like violence and stuff that I only slightly read about it, you know, but he would be able to be like, I remember this. I was there. I remember how this felt. I remember how this person felt when this person died.

Danielle spoke more specifically to how sociocultural history and experience her community mentor brought impacted her views and practices around working with her group of young people in important ways. She said,

We were lenient about some things...and Joseph, this is one thing that Joseph said time and time again—that I don't have the cultural experience of—he's like, a lot of kids who grew up in North Minneapolis, they're not given more than one chance. He told me not to break down our kids, but just to remind them that like we're giving them chances now that they're not going to get again.

As demonstrated through the mentor reflections, the community mentor partnerships were critically valuable. The community mentors brought diverse and complementary knowledge, skills, histories and identities that greatly supported the growth of undergraduate mentors and garden groups as a whole.

While the mentors unequivocally learned and grew from working in the community and alongside community mentors, they also experienced significant challenges in working across differences. Through these challenges, they demonstrated immense growth and expressed appreciation. Elise shared about her growth through working across differences, “I've grown in that I've worked with so many different kinds of people that have many different ways to interact with the world and speak and present themselves, and I've grown in my knowledge of how to navigate that.” Similarly, Camila spoke more to the value of working with people of cultures and generations different than her own. She reflected, “Gaining cultural understanding and working with people I hadn't before. I think that's important for anyone in any career. Working with different ages, the community mentors, because for most people, it's 10 years above, and here it's 50 years above.”

Camila explained more about the differences in her garden group in contrast to more traditional working environments. She said,

This is a community organization, like it's not gonna have the same structure as very professional corporate internships. So just having an open mind of—everything starts from the seed and just gets better over time. So we're still in that growing rooting process. We're a seedling. Like, you're not going to come here and it's going to be all spic and span...And I took that as a learning experience of being able to work in...something that is more free flowing.

The mentors' words show important growth in understanding how the ways in which things are done in community are different than in the university. Both spoke about appreciating and thriving in structured environments, and both grew to appreciate and work with, rather than against, the different structures of community work.

Another marked difference that each of the mentors highlighted was the ways in which communication happened in the GNM community, including conflict resolution and different ways of showing respect. Elise spoke to the challenges she navigated in working with different communication and conflict styles than she was accustomed to. Camila reflected on the challenges and value of learning to work alongside and communicate in a diverse group,

I think we had a lot of differences and in a good way. I was able to learn how they've been treated in society and how they wish to be treated and what type of problems they see in the world. Ms. Cassandra does really well on letting us know her thoughts very clearly, which I really appreciate. So, learning to work with that is sometimes tricky, but really valuable to have different opinions and learning how to speak to someone who doesn't have that same opinion.

Danielle shared her experiences of navigating the different communication and conflict resolution styles of community mentors, particularly around learning to better understand the anger that was regularly expressed amongst elders. She explained,

The elders brought a lot of kindness. Sometimes they're kind of volatile to each other, but they always brought help and understanding when we needed it. Even if our two community members aren't getting along, they'll be able to separate issues. It confused me a ton in the beginning, cause I'm like, whoa, I thought you guys hated each other. And it's like, oh, it's just this one issue that we don't agree on. It's not like them as a person.

Emily spoke to another part of learning to communicate across differences—the importance of communicating one's vulnerabilities to develop trust and be heard. She said, “When I articulated my vulnerabilities, is where they're more willing to hear what I'm saying. They want to take care of you. Showing your vulnerability to people in this community is, like, essential to being a part of it.” For each of the mentors, learning to communicate across differences varied, yet all grew in their abilities to navigate working with people of different identities, different ways of working together.

Mentors spoke about community learning, cultural learning, intergenerational learning, and learning from diverse perspectives. An openness to these types of learning is an essential disposition of a critical mentor. Danielle spoke about the power of community-based experiential learning in developing understandings around food insecurity in communities of color and problem-solving around these issues. She said,

A lot of what I've heard about North Minneapolis comes from my food classes at school. It's interesting like the way that they talk about it in classes vs. like the way it is...It's not the problem that there aren't stores. It's what's in the stores...I've realized that you really need to see it and explore it for yourself to see what solutions could actually work.

Andrea reflected on being introduced to cultural learning and community learning, and the power of these types of learning. She shared, “I was introduced to cultural learning and community learning...It's a completely different dynamic. It's real shallow in the university...here—having a bunch of different people who are passionate about their work and showing me.”

Amara spoke more on the differences of learning in community, highlighting the value of learning from others in a familial way. She shared, “Learning from people allows you to learn more about the space that you're in. And, more than what a piece of paper can tell you... in school, you have to listen to the professors...Here it's a family environment.” Community learning and cultural learning validate experiences and histories, and the reciprocal sharing of these through relationships, all of which constitutes valuable knowledge.

Many mentors spoke to the power of learning through a diversity of perspectives—youth, community, and peers. In Emily's words, “It's more of a complete knowledge circle...it creates a more holistic view of learning for different life perspectives and the perspective of privilege vs. more trauma and trials and tribulations and acknowledging that both exist in the world.” Danielle elaborated on the importance of having a diversity of voices and perspectives in a learning environment,

Generally here we're getting a diversity of voices. In the university, it's so many old white people telling you their pitch...and it's super frustrating because I know that there are other opinions...but where am I going to get that information from? Because, none of the papers I'm reading are representative of diverse voices and none of my professors are. But, within Growing North, those voices and representation are already integrated in.

Camila spoke more on the value of learning from the generational diversity in GNM, saying, “We're all learning from youth and from older people. I think Growing North brings a lot of innovation and creativity because you're working with young people. So they have different ideas than maybe college students would.” Elise commented on the knowledge that her group of young people brought to the table and the importance of learning from youth lived experience. She explained,

You can gain so much knowledge from experiences. And like some of that comes from age, some of that comes from education, some of that comes from the community that you grow up in. They all had a lot of knowledge about the way things are, about reality, the world that we live in.

The reflections of the mentors learning from multiple and diverse perspectives demonstrates their critically oriented dispositions, open to different types of knowledge and ways of knowing, outside typically regarded institutional knowledge.

In this section, we discuss our findings in connection to existing research on critical mentoring and critical food systems education. Specifically, we build on concerns about incongruencies in mentor/mentee identities (Lindwall, 2017) and associated risks of deficit-oriented, assimilation approaches that so often depict the mentor as a savior and the youth in need of saving (e.g., Baldridge, 2017). These concerns raise the critical question of how best to prepare undergraduate mentors to work with communities and youth of marginalized identities such that they develop the necessary knowledge, skills, and dispositions to support marginalized youth. Based on our research findings, we provide suggestions to prepare mentors, particularly those from dominant and privileged backgrounds, for work with youth and communities of marginalized identities.

Our findings show that critical mentoring necessitates a dive into context, the complexities of marginalization and the intersectionalities of oppressions. Critical mentors need to build cultural competencies and sociopolitical consciousness to engage in conversations and work around these issues. Aligned with Weiston-Serdan's (2017) work on critical mentoring, we found our undergraduate mentors benefited greatly from an intensive 7-week preparation course designated to develop important knowledge and dispositions. Extending Weiston-Serdan's work, we found that undergraduate mentors were best supported in engaging in this critical work through a diverse representation of course materials. They most regularly drew on the voices and lived experiences of individuals of various marginalized identities represented in the course, through slam poetry, blogs, and TED Talks. Mentors found audiovisual resources to be the most impactful and lasting, as they were often loaded with personal experience and emotion.

For many mentors, the preparation course was a crash course in issues to which they had little prior exposure. This created a shock factor as they grappled with tough issues, such as institutionalized racism, particularly given their own privileged identities and upbringings. The shock was uncomfortable and scary for most, but with time, they reported that the shock was also instrumental to their growth processes. These understandings and dispositions were further strengthened during the summer program as they moved from theory into practice, learning from community context and the diverse voices of community mentors and youth.

It was important for the mentors to build both local and broader contextual understandings of these issues. Broadly, they reflected regularly on what it means to be marginalized in America, with inequities in the justice system and policing, intergenerational poverty, intersecting marginalities, and negative stereotyping. This broad understanding was supported through local issues such a historical redlining in the North Minneapolis community. They also built local contextual understandings through hours working in the community and through interactions with community mentors. Weiston-Serdan (2017) also speaks to the importance of critical mentors understanding context, particularly because the context in which youth grow up, is toxic—racially, socially and economically. Like her, we found it important to support our mentors in critically exploring these contexts, especially as many were previously unaware having grown up in relatively privileged bubbles. Expanding on Weiston-Serdan's work, we found the exploration of both local and broader contexts to be beneficial to the mentors' understandings and building of critical dispositions. In course reflections, the mentors spoke about their plans to work alongside the youth to transform the toxic contexts surrounding them and to support them in creating new and positive narratives of their identities and communities. No longer able to ignore the toxic systemic issues, the mentors moved away from prevalent deficit-based and assimilationist mentoring (e.g., Baldridge, 2017; Lindwall, 2017) to assets-based thinking that builds on youth power leadership (Weiston-Serdan, 2017).

In our research, we found that beyond the course material, undergraduate mentors found important value in learning with and from others—their peers, community mentors, and youth. During the course, they appreciated having the designated time and space to talk through their developing understandings and to learn from others' identities, perspectives and lived experiences. They found value in building relationships through the sessions with community mentors and from spending time working with community mentors. During their summer program, the mentors reflected continuously on learning from their community mentor partners, the team as a whole, and the young people they worked with. Through this work, they continued to grow as critical mentors. They further developed important skills and dispositions in critical consciousness; recognizing and building from community and youth assets; in working across differences; and in personal awareness of their own intersecting positionalities in the community space. Critical was the ability to learn from a different system of knowledge—from community and cultural knowledge, rather than institutionalized knowledge. In our experience, the interaction from the course preceding the summer program was critical to their openness to embrace discomforts and to their readiness to grow in these ways. The course supported them in developing the foundations of critical consciousness and cultural competencies, as well as an openness to learning from diverse perspectives and different types of knowing and being.

Our findings have important implications for youth programs and university service-learning programs working to prepare mentors for youth work, particularly when working with youth of marginalized identities. Based on our findings, we offer five key recommendations, all to happen prior to the community-based summer program. First, we advise a preparation course or workshop series oriented in critical explorations around the institutionalized nature of racism, whiteness, and white supremacy, intersectionality of oppressions, power and privilege. We suggest explorations that are both broader and local/specific to the youth and communities involved. Second, after the shock factor of exploring these issues, we advise for the course to move into what we can do about these issues: to topics like critical and culturally relevant mentoring. Third, we recommend diverse representation of types of course materials, particularly highlighting voices not often included in traditional education spaces—youth and adults of marginalized identities. In this, we also recommend a diversity of course material, as those not represented in traditional academic and schooling spaces are not often represented in traditional materials, like books and articles. For this, we leaned on slam poetries, blogs, YouTube videos, podcasts and TED Talks. Fourth, we recommend intentional reflection opportunities throughout the entire experience—for personal reflection and the time and space to reflect in community. Fifth, if possible, we propose community and partner involvement in the course. The power of learning from others' lived experiences and from learning in community cannot be underestimated. For us, this was community mentors. For others, it might be family, teachers and school partners, or community partners. We found that the recommendations highlighted prepared our undergraduate mentors to enter the summer program with an openness and eagerness to continue to learn from a diversity of perspectives, and to partner with youth and community to critically mentor.

The GNM program serves as an equity-based model for SFSE programs that are interested in undergraduate service-learning projects and poses an alternative to typical garden-based and farm-to-school curricula. Typical stated goals for many of these food systems programs have focused on encouraging youth to make healthier food choices, rather than investigating historic and systematic inequalities within food systems, which often perpetuate race and class-based assumptions and deficit mindsets (Meek and Tarlau, 2016). Although the undergraduate mentors in our study were enrolled in various programs of study, this cohort identified knowledge, skills, attitudes and practices reflective of equity competencies deemed important for sustainable food systems education, an emerging program of study (Valley et al., 2020). Self-awareness can be exhibited by “awareness of one's own assumptions, values, and beliefs that may contribute to personal biases” (Valley et al., 2020). As a result of participation in the preparation course and the summer program, student mentors showed evidence of increased awareness of white privilege, understanding Whiteness, and how white supremacy manifests when working in marginalized communities. Student mentors were able to identify implicit biases that appeared as deficit-mindedness toward the North Minneapolis community and shift their view to recognize and appreciate assets. Students also showed increased awareness of their social and cultural identities and positionalities in how they may be perceived by others and learned how to present themselves in a more supportive, collaborative role through this experience. Undergraduate mentors deepened their awareness of others and their interactions with them, including the ability to recognize the “extent to which socio-cultural structures and values may oppress, marginalize, alienate, or enhance privilege and power in other's lives” (Valley et al., 2020). This was evidenced by understanding how racism affects many of the youth mentees, such as unequal policing practices, and how intersectionality can influence social inequities. In addition, undergraduate mentors learned to tailor their communication styles to more effectively interact with both community mentors and youth mentees and expressed increased confidence in working across generational, cultural, and racial differences. These attributes are important to engender trust and build partnerships necessary to do transformative, food-justice work and meaningfully address inequities in the food system.

The preparation course offered the opportunity to expose undergraduate students to systems of oppression, including identification of historic and current, localized systemic inequities that affect individuals in the North Minneapolis community, specifically. This allowed students to identify and dismantle negative stereotypes perpetuated in the media both nationally and locally. The preparation course was instrumental in shifting student mindsets to recognize deficit bias and focus on community and youth assets. Through a critical mentoring approach that we describe here, we show that undergraduate students in SFSE can gain key equity competencies that are needed to work collectively and collaboratively to dismantle food system inequities.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

The research study was conceived and designed by IL and GR. Data analysis was performed by IL. The manuscript was written by IL, with contributions from MR. Editing and proofreading was performed by IL, GR, AS, and MR. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under Award Number 2018-70026-28936, title: Growing North Minneapolis: Building Community-Based Food Systems Through Experiential Agricultural Education.