- 1Department of Architecture, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

- 2Department of Political History, Theories and Geography, Faculty of Political Sciences and Sociology, Complutense University of Madrid (UCM), Madrid, Spain

Literatures on social innovation, collective agency and multi-actor collaboration stress the importance of action research and joint problematization to research ongoing processes of collaboration and transformation to advance both theory and practice in these fields. In this paper we analyze our experience building a transdisciplinary action research (TAR) trajectory between 2020 and 2021 to investigate socially innovative multi-actor collaborations (IMACs) and urban governance innovation trajectories in the city of Leuven (Belgium). We specifically focus on (1) how we involved a wide array of researchers, stakeholders and practitioners in the TAR trajectory; (2) how we enacted joint problematization and action, ensuring that all facilitative leadership roles were taken care of; (3) the challenges that the specific COVID context posed on TAR and the innovative tools and approaches we took to adapt under such circumstances; and (4) how our TAR contributed to the ongoing IMACs in Leuven. Discussing our experience in relation to issues raised in action research literature, we summarize key dimensions, roles and tasks necessary in TAR to enable facilitative leadership and multi-actor collaboration and successfully drive joint problematization and transformative change. We conclude that our TAR trajectory in Leuven became a case study of IMAC in itself, and so learnings from our TAR directly dialogue with and inform our empirical analysis of the performance of IMACs too. Through this realization and the analysis of our experience, we get to broader question the role of action research and researchers in urban governance innovation.

Introduction

In the first months of 2020 we initiated a research aiming to analyze socially innovative multi-actor collaborations (IMACs) (Medina-García et al., 2021) and urban governance innovation trajectories in the city of Leuven (Belgium). We were specifically focusing on two ongoing IMACs aiming to transform the city's food system: (1) the multi-actor collaborative platform Leuven2030 and (2) the parallel collective development and implementation of a Food Strategy for the city. The aim of the research was to understand the collaboration process of Leuven's Food Strategy, the interferences between practice and governance levels, and the transformative socially innovative processes that occur in and through these IMAC trajectories.1

In our research we followed recommendations and experiences in the fields related to our research, i.e., social innovation (Andersen and Bilfeldt, 2013; Arthur, 2013; Konstantatos et al., 2013; Kunnen et al., 2013; Moulaert and MacCallum, 2019), governance and urban planning (Healey, 2012; Albrechts, 2013; Novy et al., 2013; Gray and Purdy, 2018; De Blust et al., 2019), and sustainable transformation of food systems (Tornaghi and Van Dyck, 2014; Moragues-Faus et al., 2015; Bradbury et al., 2019; Hammelman et al., 2020). These stress the importance of “praxis oriented,” transdisciplinary research and joint problematization among researchers, practitioners and stakeholders to investigate and address current complex urban challenges to advance both theory and practice. We embraced these recommendations by taking a Transdisciplinary Action Research (TAR) epistemological and methodological approach.

As Fontan et al. (2013, p. 311) describe, in TAR “a researcher collaborates with practitioners in the effort to change a situation and resolve a problem experienced in a milieu, community or organization, and to improve the understanding of the phenomena in question.” Action research (AR) in general is a critical research approach rooted in the epistemological belief that combining different types of knowledge and experiences and building horizontal relations between researchers and “objects of research” can contribute to cocreation and democratization of socially valid knowledge and empowerment of the actors participating in the research process (Fals Borda, 2006; Andersen and Bilfeldt, 2013; Moragues-Faus et al., 2015). According to Bradbury et al. (2019, p. 6) AR does so “not by starting with the expert understanding of our problems, but by helping those with stake in an issue to see their own problems more clearly and to take intelligent action with others in response to their shared learning.”

The objectives of applying TAR to our research in Leuven were to: (1) gain a broader understanding of the complexities of ongoing IMAC processes while contributing to their performance and the broader governance transformations in the city; (2) contribute to internal reflection within each IMAC trajectory and participant initiative; and (3) enable dialogue, exchange and mutual learning among actors involved in governance innovation in the city. We experimented with different ways to interact with ongoing IMACs and contribute to collective reflection, joint problematization and further multi-actor co-creation, that would be relevant both for the academic scholarship and the daily practices of the initiatives involved (Fontan et al., 2013). In this paper we share our experience doing TAR between spring 2020 and summer 2021 and reflect on the challenges and learnings along the process. Through the analysis of our TAR we contribute to action research literature distilling key dimensions of TAR and specificities on how to conduct socially innovative TAR in the field of governance innovation.

The remaining paper is structured as follows. In Section Epistemological and methodological approach: transdisciplinary action research to investigate governance innovation in Leuven we explain our TAR epistemological and methodological approach, showing how social innovation theory enriches action research literature and practice bringing in specific analytical tools (i.e., socio-institutional analysis) and ethics (i.e., reflecting on the socially innovative nature of TAR and the positionality of researchers in the phenomenon investigated). In Section Our experience conducting transdisciplinary action research in Leuven: research trajectory, challenges, and adaptations we describe our experience conducting TAR to investigate socially innovative multi-actor collaborations in Leuven. We specifically focus on (1) how we involved a wide array of researchers, stakeholders and practitioners in the TAR trajectory; (2) how we enacted joint problematization and action, ensuring that all facilitative leadership roles are taken care of; (3) the challenges that the specific COVID context posed on TAR and the innovative tools and approaches we took to adapt under such circumstances. In parallel, we explore (4) how our TAR was a socially innovative practice in itself, interacting with and contributing to ongoing IMACs in Leuven. In Section Discussion we discuss how action and research enrich each other and how, when applied to research about IMACs, the TAR trajectory became an actor in the broader landscape of governance innovation. As such, it contributed to changing existing social relations empowering vulnerable and excluded actors in Leuven, and became a field for experimentation that directly informs and affects further steps in the IMACs investigated. Further discussing our experience in relation to issues raised in AR literature, we summarize key dimensions, roles and tasks necessary in TAR to enable facilitative leadership and multi-actor collaboration and to successfully drive joint problematization and transformative change. Specifically, we address the importance of transparency, continuous negotiation and adaptability, and combination of project-based interventions and potential to contribute to long-term transformations in the TAR process; the agency of interaction and of collective outcomes; relevant dimensions of communication governance in TAR (in COVID times); and the relevance of establishing an Editorial Board. In Section Conclusion we conclude that our TAR trajectory in Leuven became a case study of IMAC in itself, and so learnings from our TAR directly dialogue with and inform our empirical analysis of the performance of IMACs too.

Epistemological And Methodological Approach: Transdisciplinary Action Research To Investigate Governance Innovation In Leuven

In this section we elaborate on the body of knowledge that has guided our transdisciplinary action research trajectory and how we structured our research. To explain our specific epistemological approach, we enrich the action research (AR) approach with reflections about transdisciplinary research introduced in social innovation literature.

The Basics of Action Research

Action Research (AR) is an umbrella term covering a variety of approaches to building “collaborative research, education and action oriented toward social change” (Kindon et al., 2007, p. i). When different strands of AR extended in the 1970s, it represented a major epistemological challenge to mainstream research and knowledge production traditions, opposing positivism and the supremacy of academia (Fals Borda, 2006). By involving those vulnerable communities affected by the issues investigated, it advocates combining academic research and knowledge with everyday praxis and wisdom. It also seeks a more horizontal relation and collaboration between research subjects and objects, which empowers participants and stakeholders of the research through democratization of knowledge (ibid.). As an epistemological position, AR is a “philosophy of life” (Fals Borda, 2006), while from a practical methodological perspective, AR is a cyclical process (Kindon et al., 2007), which starts with a joint identification of the issue and research that leads to collective action, followed by a reflection about the learnings from the action to start the analysis, investigation, action and reflection processes again. Along the AR iterative process, different meanings, knowledge and outcomes are negotiated and coproduced that are useful both for academia and practice (ibid.).

As any collaborative process, AR takes time and relies on building trust by being sensitive to participants' interests and sensibilities. As Monk describes:

Action Research is not an approach that can be rushed into, but one that takes time and talent, that requires the building of trust, and being sensitive to ‘turf'.[…] Working across the boundaries of academia and other worlds requires cultivation of mutual understanding and respect, sensitivity to differences in organizational cultures and goals, networking and sharing information, recognizing and strengthening individual and group capacities, questioning priorities, formulating questions so as to foster change and not simply to ‘explain' what is, and, not surprisingly, dealing with diverse personalities. (Foreword in Kindon et al., 2007, xxiii)

Already from these words, we understand that such a research approach requires reflexibility and care for the process, the actors involved, the relations established and the methods negotiated.

AR From a Social Innovation Perspective: Transdisciplinary Action Research

AR relates directly to the definition of social innovation (SI) from the Euro-Canadian school (Moulaert and MacCallum, 2019). SI addresses collectively defined needs by means of innovating in social relations and empowering those affected by the issue researched and often excluded from decision-making (Moulaert et al., 2013). Actually, much has already been written about the relation between AR and SI, and the transformative power of AR applied in SI research (Arthur, 2013; Fontan et al., 2013; Konstantatos et al., 2013; Moulaert and MacCallum, 2019; Van den Broeck et al., 2020). Taking into account that our research is focusing on collaborative processes within socially innovative multi-actor collaborations, the consideration of AR as a collaborative process and as SI adds an extra complexity layer, i.e., investigating a process while experiencing it. Consequently, for our research, we enrich the general AR approach with learnings and considerations from its application in SI research, aiming to contribute to this field with the specific experience of researching about and with IMACs.

Like AR, SI research is praxis-oriented and aims to facilitate a process of knowledge co-production, integrating tacit, practical and collective knowledge and experiences (Konstantatos et al., 2013). From this perspective, SI research has the potential of being socially innovative through its own activities, which follow the same values of solidarity, reciprocity and association of SI itself (Moulaert and MacCallum, 2019; Assaf et al., 2021). The key for achieving such potential lays in adopting a transdisciplinary approach, that connects researchers, practitioners and stakeholders outside academia through a process of joint problematization by which participants collectively define and address uncertain and complex social problems (Moulaert and MacCallum, 2019). Similar to AR literature in general, in transdisciplinary action research (TAR), stakeholders are not just taken as “informants,” but are actively involved in the co-design and co-creation of the problem definition, the research methods, data analysis, and dissemination of results in different formats and languages that are meaningful for the actors involved and that can lead to a solution to the problem investigated.

What is specific in SI research from a planning perspective though, is the institutionalist approach to SI and governance transformation processes (Healey, 1999; González and Healey, 2005; Van den Broeck, 2011; Servillo and Van Den Broeck, 2012; Moulaert et al., 2016; Manganelli, 2019; Oosterlynck et al., 2020), which aims to unveil the time and space-specific organizational and institutional frameworks in which these occur. It focuses the attention on analyzing actors and stakeholders, arenas, discourses and practices to identify interrelations between specific practices and episodes and deeper structural changes in governance structures (González and Healey, 2005).2 This approach helps understanding power relations and (dis)empowering mechanisms both in the “object of study” and the action research process, and serves as the basis for further joint action and research. To conduct such an analysis, and enriching the general AR approach, apart from combining academic and “everyday” knowledge, TAR also requires inter-disciplinarity, that is, on bringing together input and methodologies from different disciplines to achieve a holistic understanding of the issue at stake (Moulaert and MacCallum, 2019).

Novy et al. (2013) already explored how to establish platforms where academics, practitioners and other non-academic stakeholders can interact along the process of knowledge cocreation. Specifically, they identified five key elements to achieve successful joint problematization, knowledge coproduction and long-lasting collaboration relations in TAR. First, specific interests, knowledge and skills of each participant need to be identified, valued and integrated in the joint design of research questions and steps, in the collective understanding of terms and results, and in the valorization and evaluation of the results. Second, appropriate spaces and time need to be designed and allocated to build trust among participants and to facilitate democratic decision-making and the contribution of each of them in each stage of TAR. Third, and related to the previous point, communication tools and strategies shall be designed so that all actors can contribute “on equal footing.” Managing communication among the diversity of actors that participate in a TAR process requires translation between languages, registers, realities and logics of the actors involved and taking the time to exchange and negotiate approaches to build common understanding and strategies. Fourth, contribution and allocation of resources and tasks by the different participants shall be transparent, clear, fair and negotiated according to the characteristics and possibilities of each actor. Resources in this context include material and immaterial ones, such as time, knowledge, skills, expertise or labor among others (Ansell and Gash, 2008; Martinelli, 2013). Fifth, all participants shall be able to disseminate cocreated knowledge in their own context, be it in the shape of a collective outcome and/or in different formats and styles adapted for specific interest groups or purposes.

In terms of data gathering techniques for SI research, Konstantatos et al. (2013) defend the use of qualitative and participatory methods based on interaction between researchers and stakeholders like interviews, focus groups, participant observation and participatory methods. Lately, media-based and artistic methods and new tools to collectively explore and visualize issues and relations, such as participatory mapping and diagramming, have also spread within TAR as a means to emphasize exchange and negotiation among actors in the knowledge co-creation process, both in data gathering and analysis stages (Kindon et al., 2007).

Two Key Aspects in the TAR Process: Reflexivity and Positionality

Two other concepts are stressed in SI literature while conducting and evaluating TAR: reflexivity and positionality. These terms relate to the ethics of TAR and aim to reflect on the role of TAR as SI and about how researchers become part of SI by collaborating with other actors during joint problematization, respectively (Moulaert and MacCallum, 2019).

Reflexivity refers to the continuous reflection about the TAR process as a SI trajectory. It relates both to “the social relevance and ethical appropriateness” of the collective research and action (Moulaert and MacCallum, 2019, p. 115) and the power dynamics enacted and changed in and through the collaboration process. For this, actors involved in TAR must acknowledge AR in itself as a form of power to affect reality and so wonder whether its use is justified as the means to address particular questions in particular contexts (Kindon et al., 2007) and ensure that the process develops according to SI principles (Moulaert and MacCallum, 2019). Some aspects to consider are: whether all relevant stakeholders are being integrated in the TAR and whether there is a fair share of tasks, knowledge and authority (ibid.); whether relevant scientific-, policy-, and practice-related knowledge is being produced and appropriately adapted and disseminated to reach diverse interest groups; whether the collaboration is contributing to more democratic and sustainable knowledge production (Novy et al., 2013) and analyzing how new cocreated knowledge is contributing to changing the reality (Hamdouch, 2013).

Positionality, refers to the researchers' continuous reflection about their role and contribution in the TAR and SI processes and requires consciousness about context and power relations between them and other participants (Konstantatos et al., 2013; Vicari Haddock and Tornaghi, 2013). It also requires further assessment of the researchers' biases, believes, and perspectives vis-à-vis “the subject, participants and research context and process” (Major and Savin-Baden, 2013, p. 71) as well as their performative impact in the broader trajectory of the SI initiatives investigated (Vicari Haddock and Tornaghi, 2013).

Role of Researchers Within SI Trajectories and SI Research

Similarly to any other stakeholder, researchers can engage in different stages within SI research. To enable a rich reflection about our role in the TAR trajectory, we summarize roles that researchers in particular, and academia as a collective agency, can take in TAR from the SI and transdisciplinary AR literature.

First and foremost, SI research and TAR scholarship aim to fight the general critique to academia that academic environments, as they deal with the creation of “valid knowledge” and discretionally choose research topics, may contribute to reinforcing dominant discourses and empowering or disempowering specific narratives and actors (Hammelman et al., 2020; Klein, 2020). Therefore, the deliberate decision to investigate socially innovative trajectories through TAR is in itself an engagement to contribute to SI by building and disseminating alternative experiences, co-created visions and understandings and interrelations among fields of knowledge that “redefine” reality and “what is right,” and legitimize specific action and actors (Moulaert and MacCallum, 2019; Klein, 2020). Nonetheless, such an ethical stance must not divert researchers from committing to rigorous research and knowledge building. As Fontan et al. (2013, p. 317) remind, despite taking a collaborative and participatory approach, researchers must maintain their academic independence of thought and freedom of action, caring for the quality and integrity of the research, and refusing to subordinate to the interests of particular partners.

Second, within a specific TAR trajectory, as Hamdouch explains (Hamdouch, 2013, p. 259), the challenge for researchers to contribute to SI trajectories is to continuously reflect about “how new knowledge about the reality of SI initiatives and dynamics can be built and, at the same time, contribute to changing the reality.” For this, researchers take a deliberate stance in regards to the issue researched. For instance, when we research IMACs transforming food systems, we do so from the critiques built from SI literature to mainstream approaches of sustainable transitions and the critiques of alternative food networks to mainstream food systems.

Third, when immersing in SI processes, researchers may take the role of “active actors” contributing to the codesign and implementation of SI action or as “facilitators” mediating among actors in the field and helping in the knowledge cocreation and the collective learning processes (ibid.). Vicari Haddock and Tornaghi (2013) further explore this line, noting that researchers can help shaping dialogue among actors and enabling new alliances by means of mobilizing the knowledge they gain during the research and sharing it with actors on the field. Moreover, the “action research thinking” introduced by researchers in SI trajectories can “help stakeholders become aware of their existing/potential powers, capabilities and resources and assist them in the design and implementation of democratically co-created solutions that could “work” for them” (Hamdouch, 2013, p. 260). In this respect, the role of researchers as documenters and analysts of the SI reality is always different from that of practitioners or other stakeholders (Kunnen et al., 2013).

Coordination and Facilitative Leadership Roles in the Governance of TAR and IMAC Processes

By building a collaborative TAR trajectory in Leuven, not only do we position the research process within the SI case study, but it also allows us to “practice” with collaboration processes and improve our understanding of the IMACs we are investigating. Thus, our reflections about our role as researchers in IMACs in Leuven and about how coordination and facilitation are enacted in TAR can inform our results in relation to the role and performance of IMACs too. For these reflections, we complement theories about coordination of TAR processes with the lens of collaborative governance we mobilized to understand collaborative processes within IMACs.

Regarding how joint problematization is facilitated within TAR, Cassinari et al. (2011) draw attention to the differing performance and involvement of actors participating as “stakeholders” and/or as part of the “coordination team.” Stakeholders are understood here as “any person or organization, who is affected by the social context and effects of the research project, or who can contribute to the process of knowledge production” (Cassinari et al., 2011, p. 16). Stakeholders can participate along the whole process, or intervene in specific activities or interaction moments, e.g., in problem identification, analysis or results implementation stages. Coordination responsibilities however, are required along the whole process, which include: (1) identifying and framing tasks and time-frames; (2) communication management; (3) leading with the “tension between heterogeneity and effectiveness” through reflexivity and trust-building; and (4) maximizing application of results in practice through “cognitive integration of knowledge” (Cassinari et al., 2011, p. 17). In our research, while the authors of this paper took a coordinating role as part of the “Editorial Board” established at the beginning of the TAR, and, thus, were involved in all stages, other researchers and stakeholders of the IMACs only participated in some stages or activities under the role of “stakeholders” of the TAR.

To further explore the governance of the TAR and roles taken up by different participants, we recognize the three facilitative leadership roles Ansell and Gash (2012) identify in collaborative governance: stewards, mediators and catalysts. Each role cares for different dimensions of the collaboration: the integrity of the collaboration process, the relations between participants and the potential and impact of the collaboration, respectively. As Ansell and Gash (2012) describe it, stewardship is closely related to the first coordinating responsibility, since it involves convening stakeholders, framing the agenda of the collaboration, helping establishing the collaboration and caring about the institutional structure, resource allocation and transparency of the whole collaborative process. Mediation relates to the following two coordinating responsibilities, with the focus set on nurturing and stabilizing relations among participants and contributing to building shared understandings. Tasks related to this role include easing engagement, communication and trust-building of and among participants and mediating and arbitrating in conflicts and differing understandings as they arise. The catalyst role relates to the last coordinating responsibility and implies that participants reflect on the mutual reinforcement between the collaboration process and the innovation that is collectively achieved, helping the group identify valuable action and research avenues and pursuing them.

Conducting TAR to Investigate Governance Innovation in Leuven in COVID Times

Between 2020 and the summer of 2021, we set up and developed a TAR trajectory to investigate governance innovation in Leuven, focusing on two (presumed) innovative multi-actor collaborations (IMACs) in the city: Leuven2030 and the collective development of a food strategy.

Leuven2030, initially named Leuven Klimaatneutraal 2030, was established in 2013 as a non-profit governmental organization, after decades of multi-actor experiments and projects addressing sustainability issues at the local level. It acts as multi-actor umbrella organization to join forces among the local administration, public companies, businesses, knowledge and social organizations and citizens in achieving a carbon-neutral city by 2050. However, Leuven2030's “climate neutrality” approach fell short in addressing some aspects of the sustainability transition, such as the transformation of food systems. In reaction to this, a bottom-up process to develop a food strategy for Leuven was initiated in 2017 by urban actors that were already building an alternative food system, parallel to the work of Leuven2030 but aiming to involve all actors participating in Leuven's food system. After several workshops, the Strategy “Food Connects” was published in 2018. In the subsequent years, this strategy was subject to several processes of institutionalization, during which its objectives were integrated in the Leuven2030 Roadmap developed in 2019, as well as in the work of the local government and Leuven's Climate Action Plan passed in 2020.

In addition to the inherent challenges of applying TAR in a new context for the lead researchers, the specific timing of our research, coinciding with COVID, casted additional obstacles that forced us to keep evaluating and adapting the research plans. When the Belgian government enforced tele-working and highly restricted physical social interactions in March 2020, measures that in different degrees of severity remained until the fall of 2021, both researchers and urban actors involved in Leuven2030 and the transformation of Leuven's food system were forced to find online (or hybrid) alternative ways to continue academic activities and collective reflections and actions. This affected communication, interaction and trust-building processes among researchers and between researchers and stakeholders, and triggered their creativity to adapt participatory research methods related both to AR and the work of IMACs.

In order to face these additional challenges and increase the reach and impact of our research, the lead researchers took the strategic decision to build a collaborative research trajectory involving different types of stakeholders from the IMACs studied and combining different levels of teaching and research within the department of Architecture at KU Leuven. These were: two advanced master thesis students and the students in two courses coordinated by Prof. Pieter Van den Broeck that focused on putting into practice strategic spatial planning through TAR, i.e., the Institutional Aspects of Spatial Planning (IASP) course taught in the fall semester and the International Module in Spatial Development Planning (IMSDP) in spring.

Within the resulting collaborative TAR trajectory, the authors of this paper acted as the “Editorial Board” that drafted the research questions and approach and cared for the research integrity and process along the year. The latter required documenting and discussing, not only the results of the TAR, but the process itself, for instance, by making minutes of all meetings and documenting group management documents and decisions, and recording and transcribing meetings with stakeholders. The other researchers intervened in different stages of collective problematization, as well as in the design and implementation of TAR interventions involving a broader array of actors from the city, i.e., citizens, experts, and academics, alternative practices in the food system, coordinators from Leuven2030 and politicians and civil servants from the local administration.

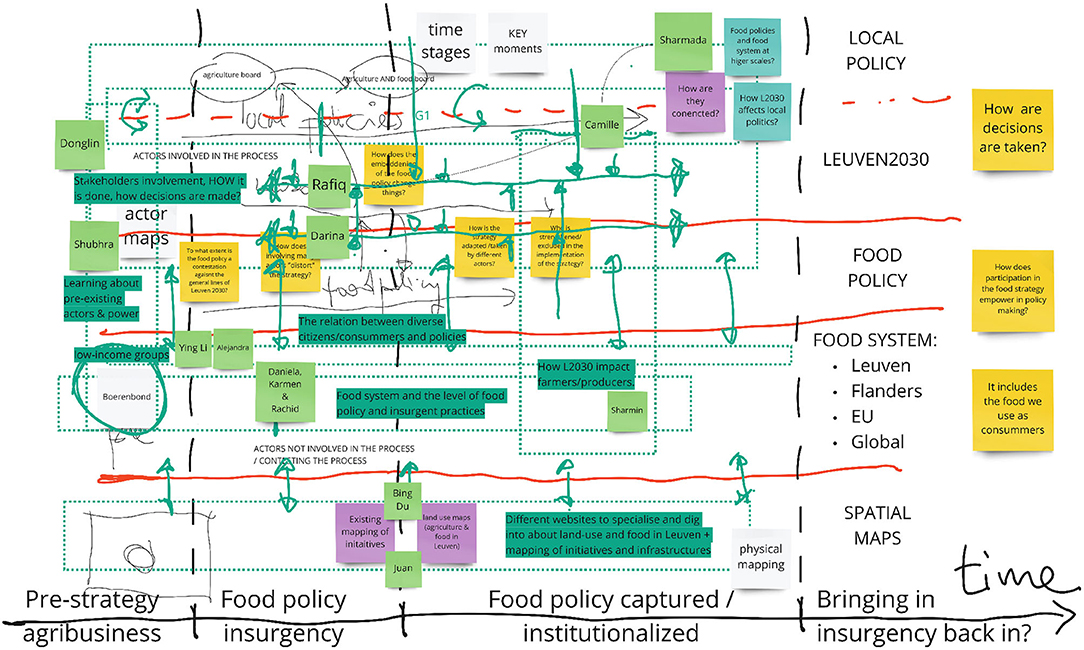

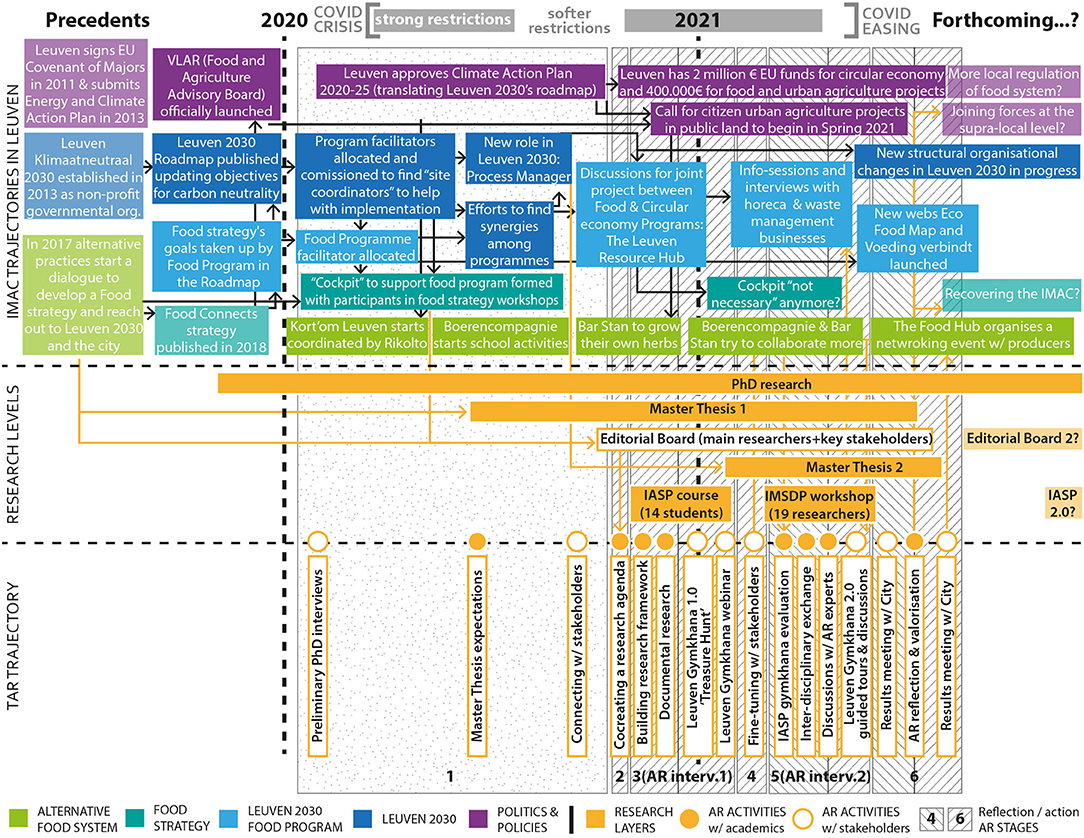

In Figure 1 we summarize the key moments of the ongoing IMACs in Leuven that we were researching and acting on in relation to the research layers combined in our trajectory and the specific research activities and interventions conducted (the TAR trajectory), indicating the resulting TAR stages that guide our analysis of the TAR experience in the following section.

Figure 1. Timeline describing key moments and actors in the IMAC trajectories investigated (top), the research levels involved in the TAR (middle) and the specific TAR activities and stages (bottom).

Our Experience Conducting Transdisciplinary Action Research In Leuven: Research Trajectory, Challenges And Adaptations

Strategic Design of the TAR Trajectory and Collaborative Framework in COVID Times

The research trajectory started with a preliminary research that helped frame the research issues, map actors involved in the case studies and inform the TAR agenda and plan. This included interviews with representatives from Leuven2030, Gent en Garde, Rikolto and the municipality conducted by PhD researcher Clara Medina-García between January and February 2020 and further documentary research about Leuven2030 and the “Food Connects” Strategy. The insights from this stage led to the assumption that Leuven2030 was an example of socially innovative multi-actor collaboration (IMAC) (Medina-García et al., 2021) that is contributing to democratic innovation in Leuven. They also helped identify sustainable transformations in the local food system as a relevant field for further research through TAR, taking Leuven2030's Sustainable and Healthy Eating Program and Leuven's Food Strategy as entry points.

Given the extra difficulties COVID casted on meeting and mobilizing stakeholders, the PhD researcher and her promotor resolved to frame the TAR trajectory along the 2020–2021 academic year as several cycles of collaborative research involving other researchers and students from the Department of Architecture of KU Leuven. In June 2020, Sharmada Nagarajan joined the research team to develop her Planning Master Thesis.

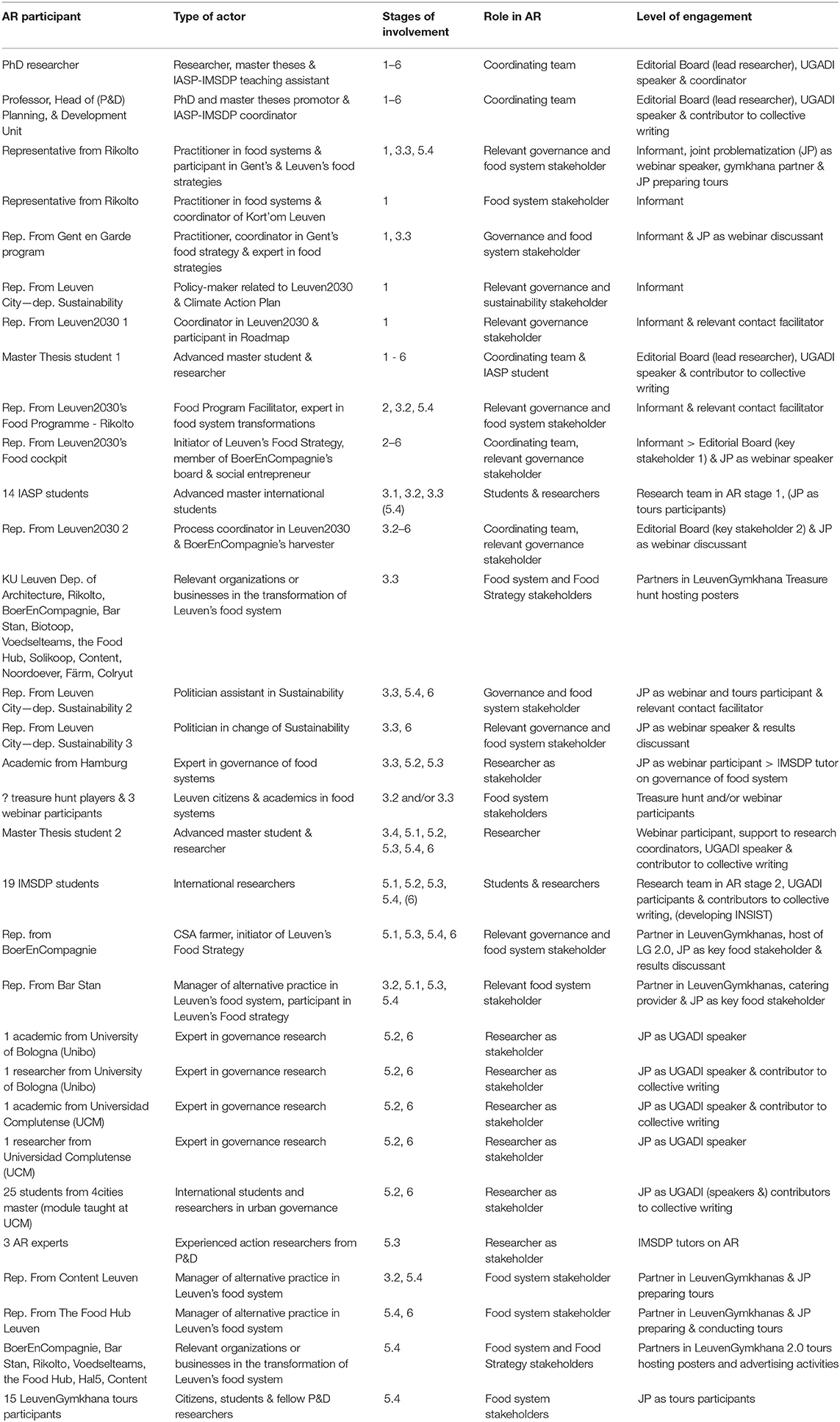

Table 1 lists all the individual and collective actors −70 researchers and 40 stakeholders- that participated along the different stages of the TAR, specifying their role and contributions.

Table 1. List of researchers and stakeholders involved in the AR trajectory in order of contribution.

Building Relations With Stakeholders and Negotiating an Action Research Agenda and Plan: The Birth of the Editorial Board

In October 2020 the incipient research team conducted more exploratory and propositional online meetings to identify key stakeholders with whom we could establish a collaborative mutually enriching relationship along the year. The stakeholders previously interviewed became the first nodes from which to build a network for the TAR through the “snowball” method. This led us from one general coordinator in Leuven2030 to the Food Program facilitator, who referenced us Erik Béatse, member of the “Cockpit” that was supporting the implementation of the Leuven2030 Food Program.

During our meeting, we learnt that Erik had been involved in the development of both Leuven2030 and the Food Strategy from the beginning—on a voluntary basis—and kept working as a social entrepreneur and board member in BoerEnCompagnie, a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) initiative in Leuven. We soon identified common interests in the governance and social justice dimensions of the Food Strategy and potential to enrich the research from his practical perspective, to support his and collective critiques to the ongoing IMACs and help the further implementation of the Food Strategy through our TAR. We then agreed to establish an Editorial Board for the TAR with Erik as key stakeholder supporting research coordinators. Together, we co-designed the research agenda for the next TAR stage with the IASP students. Without defining a specific expected outcome, the resulting “IASP Brief” text drafted initial assumptions, general objectives and a theoretical frame to guide them.

First Cycle of TAR: The Work With IASP Students

Co-developing an Institutionalist Analysis Framework: Joint Problematization and Desk-Screen-Research

In November 2020, when stronger lockdown measures in Belgium forced all academic activities to go online, the IASP course started with 14 advanced master students, all international. In the first session, the Editorial Board introduced the case studies and the Brief. Our starting point was the preliminary critical assumption that, although Leuven2030 and the Food Strategy were examples of governance innovation in Leuven, social justice, discussions about “uncomfortable topics” related to the transformation of the food system and civil-public collaboration (explained below) were gradually disappearing in Leuven2030's Food Program and the Food Strategy. The objective for the IASP team was to perform a “TAR intervention” with which we could explore these preliminary assumptions and alter public-civil relations in Leuven, aiming to improve the access of civil society to the implementation of the Food Strategy.

Through online collective brainstorming and discussion sessions and documentary research, IASP students started taking ownership of the issue and developing a collective institutionalist analysis through the reconstruction of a narrative of the IMACs investigated. Research coordinators kept reflecting about the research and group processes between working sessions and readjusting the work plan for following ones. As the research advanced, the team identified areas that needed further research in order to fully grasp what was going on in Leuven's food governance (Figure 2). Then, IASP students divided into five teams to explore specific dimensions that could enrich our collective understanding: (1) the evolution of local and supra-local policies and politics in relation to governance and the food system; (2) the evolution and work of Leuven2030; (3) the current food system, its impact and the actors involved in Leuven's food system; (4) the principles behind the Food Strategy and the alternative practices trying to transform the food system; and (5) identifying and making maps that supported the work and results from all groups.

All groups worked simultaneously in online collaborative text files and a miro board accessible to all IASP members, and kept sharing and discussing their advancements in plenary sessions. During these meetings we could establish connections among groups and realize the complexity of layers, actors and institutional relationships that collided in the process of developing of Leuven2030 and the Food Strategy. Occasional interaction with our key stakeholder through the Editorial Board complemented the groups' research and gave us feedback on our analysis and intervention ideas.

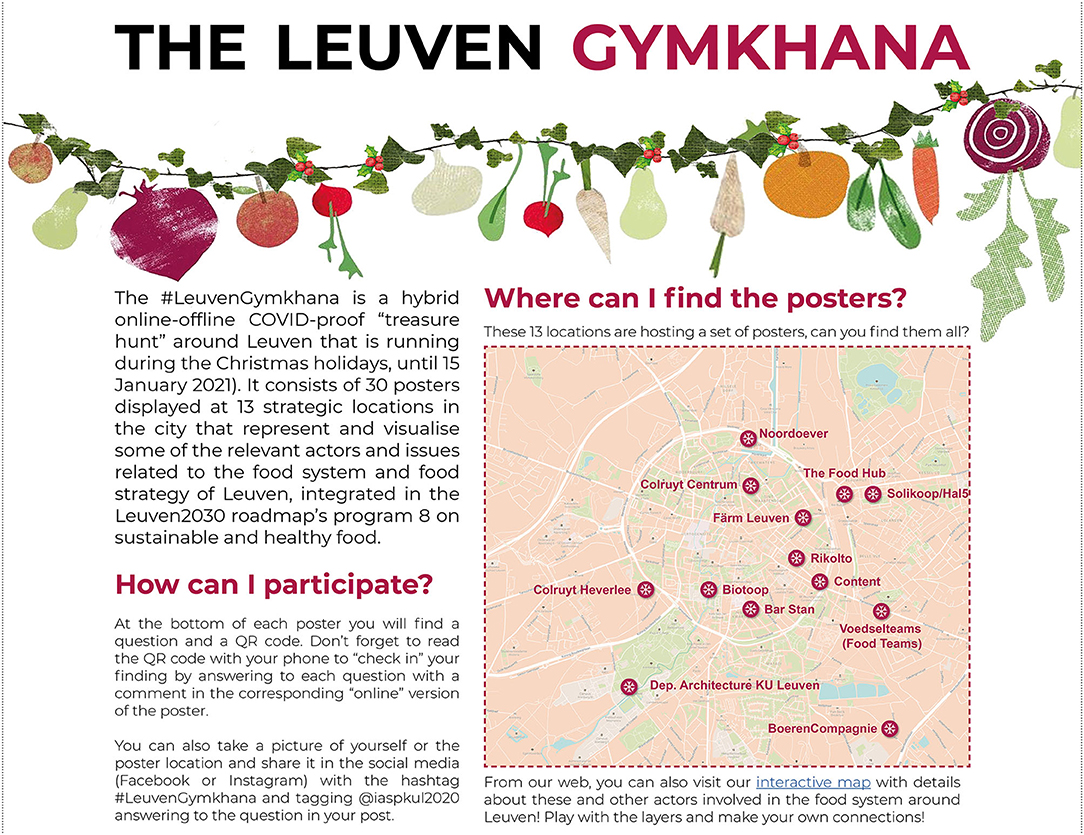

Eventually, we agreed that making the complex findings accessible and comprehensible to the broader population and opening a broad debate about them with citizens and stakeholders involved in the processes was already an ambitious objective for the IASP TAR intervention. With this in mind, and taking into consideration COVID restrictions regarding group gatherings, the team co-designed and developed two activities: the LeuvenGymkhana3 treasure hunt and a Closing Webinar. To advertise the activities and facilitate online conversations about the findings, we created the “LeuvenGymkhana” brand, website and Instagram profile. The Editorial Board checked the relevance and appropriateness of the collective idea with Sarah Martens, an expert in civic participation that had recently joined Leuven2030's coordination team. From then on, she remained close to the Editorial Board bringing in Leuven2030's perspective.

Once the idea had been validated, the five IASP research teams rearranged to cover the “practical tasks” required to run the interventions: poster atlas production, content development, website creation and management and documenting the process. The research coordinators retained continuous dialogue with the key stakeholders, who helped finetune the content produced. They were also responsible for organizing the agenda and practicalities for the treasure hunt and the webinar (IASP's exam). This included reaching out to actors in Leuven's food system taking advantage of previous personal relations and their position in university and negotiating their collaboration as partners hosting the posters of the gymkhana (Figure 3), and/or as speakers or discussants in the event.

Figure 3. Crop from the LeuvenGymkhana advertising poster showing all the partner organizations hosting posters for the treasure hunt.

Democratizing Our Findings and Inviting Stakeholders in Our Joint Problematization: The LeuvenGymkhana Treasure Hunt

The LeuvenGymkhana treasure hunt consisted of 30 posters displayed at 13 strategic locations in Leuven that represented and visualized some of the relevant local actors and issues related to the food system and Food Strategy (Figure 4). Each poster either introduced the organization hosting the posters or featured a specific statement sharing part of our analysis, supported by relevant graphics, e.g., timelines, actor-maps, diagrams or maps, and posed a question for participants to react online4 While the posters functioned as offline medium displaying our findings, social media tools like Facebook, Instagram, and WordPress functioned as the platforms on which to advertise the event and facilitate online discussions.

Figure 4. Pictures of the LeuvenGymkhana posters displayed in the premises of different stakeholders of the food system in Leuven between December 2020 and January 2021.

This intervention focused mainly on connecting with alternative practices and actors in Leuven, visualizing them and engaging the public in the broader debate of the Food Strategy. On the one hand, asking for permission to show posters in local businesses and organizations allowed us access to new stakeholders. On the other, we would further develop the narrative and test it by gathering comments from such stakeholders and participant citizens. While we succeeded in the networking part, mainly thanks to references from our network of stakeholders, we did not manage to collect online reactions from participants. Consequently, we could not really assess the reach of the intervention among citizens nor integrate their views at this stage.

Involving Decision-Making Stakeholders in Joint Problematization About IMACs in Leuven and Negotiating Further Steps in Our TAR: The LeuvenGymkhana Webinar

As closing event of the gymkhana, we organized a webinar on 22 January where we could share our IASP work, learn about the perspectives and experiences of the relevant actors of the Food Strategy identified during our research, and start a conversation among them with the specific focus on governance. Its organization was strategic to capture the attention and perspective of bigger actors and decision-makers related to the Food Strategy involved in its drafting process and implementation and to empower voices stating that alternative practices and citizens were being excluded from further decision-making. Our objective was to integrate more actors in the joint problematization about the current stage of the implementation of the Food Strategy and to find common agreement on challenges to move forward and on how the TAR trajectory could support the process.

The event was public but required prior registration via an online form in which we could gather some background information from participants, share the objectives of the research and obtain consent for recording and using the event for our research purposes. Not only was this form an adaptation of “standard” information letters and consents to online events, but also to the collaborative nature of our TAR. In total, 5 relevant stakeholders and 7 external participants joined (see Table 1).

The webinar raised and revealed specific aspects of governance and participation within Leuven2030 and the Food Strategy that helped us fill some gaps in our narrative and further refine our TAR goals for the following stages. From the personal experiences shared we could better understand the multi-actor collaborations that led to Leuven2030, its Roadmap, and the parallel development of the Food strategy. The renewal of the local government in 2019, the City's choice to regard agriculture as a matter of sustainability rather than just an economic activity, and the decision to embrace the Food Strategy to guide steps in the new legislature, were identified as key moments that reinforced the Food Strategy's goals and subsequent implementation. Participants also discussed how Leuven2030 and the Food Strategy had evolved through time, from being citizen- and expert-led initiatives to a current institutionalized framework supported by the City and larger organizations. Through the debate, stakeholders agreed on the need to re-open the strategy to citizens and to realign and restructure their goals and functioning to be more inclusive of the perspectives of alternative practices as well as the diversity of consumers in terms of diet, culture, time and money availability, location. They also agreed that it was time to address conflicting and “uncomfortable” topics pertaining to food and agriculture left out in the process of building consensus, such as debates around meat consumption. Lastly, questions were raised about how to re-open and conduct broad debates to discuss and improve upon these aspects (taking into account COVID times), and who should moderate these debates.

These discussions and learnings were documented in a report developed by research coordinators5. These were discussed by the Editorial Board and taken up as starting points to update the IASP Brief into the IMSDP Brief. The report was mailed to all participants and made available publicly in the LeuvenGymkhana website to expand the community around our TAR.

At this stage Lariza Castillo-Vysokolan joined the research team, which added a new dimension in the TAR trajectory, since she would combine her master thesis research, focusing on the role of Leuven2030 as a collaborative platform (Castillo-Vysokolan, 2021), with an internship within Leuven2030's Food Program. This allowed her (and the team) to gain insights from inside and better understand the governance transformations within Leuven2030 and the current approach and role of the Food Program in the implementation of the Food Strategy.

Second Cycle of TAR: The Work With IMSDP Researchers

Transferring Knowledge to IMSDP Students and Engaging Alternative Practices: Playing and Evaluating the IASP LeuvenGymkhana

The work with the 19 international pre-doctoral researchers participating in the IMSDP between March and May 2021 posed three extra challenges in relation to the IASP experience. First, none of the students were familiar with Leuven and the Flemish context, as they were attending a 3-month research training program. Second, this was a hybrid group, with some students able to travel to Leuven and others attending online with the possibility to join live later if international traveling restrictions allowed it. Third, the IMSDP work was to build on the IASP experience, a methodological and team-building challenge requiring knowledge transfer and facilitating that the new group took ownership of the previous joint problematization and learnings and managed to move forward.

Bearing this in mind, the first session of the workshop consisted in playing together a hybrid version of the IASP LeuvenGymkhana, guided by the Editorial Board, and watching the webinar together. The research coordinators took advantage of the walks arranging meetings with two alternative practices hosting our posters directly involved in and affected by the Food Strategy: the CSA BoerEnCompagnie and restaurant Bar Stan. Also, catering for the day was provided by two LeuvenGymkhana partners.

As we visited the posters on site, the lead researchers kept sharing pictures and recordings from the explanations with the students following online, who, in exchange, had more time to explore the website, get familiar with the IASP material and discuss the gymkhana in the online classroom. This experience allowed the IMSPD team to test and criticize the Gymkhana from a participant's perspective; to read, understand and discuss all posters; and to start getting familiar with Leuven's food system by visiting relevant stakeholders. The meetings with the alternative practices turned out key in learning about the interests, struggles and existing collaborations among them and, from this point on, BoerEnCompagnie and Bar Stan became key stakeholders in our TAR. Lacking the time to formally join the Editorial board, they kept contributing to further joint problematization by giving feedback on our advancements and sharing their experiences further in short meetings with the research coordinators and supporting the logistics of the LeuvenGymkhana 2.0.

The second session started with presentations by the research coordinators, aiming to provide additional insight on the history of Leuven2030 and the Food Strategy, the work developed with IASP students and the theoretical framework behind our work. The development of the session was in itself dynamic, with presentations building on each other and putting them to test with questions and different interpretations from students. These discussions advanced the IMSDP joint problematization and set the basis toward the final scheme for our analysis: the LeuvenGymkhana timeline.

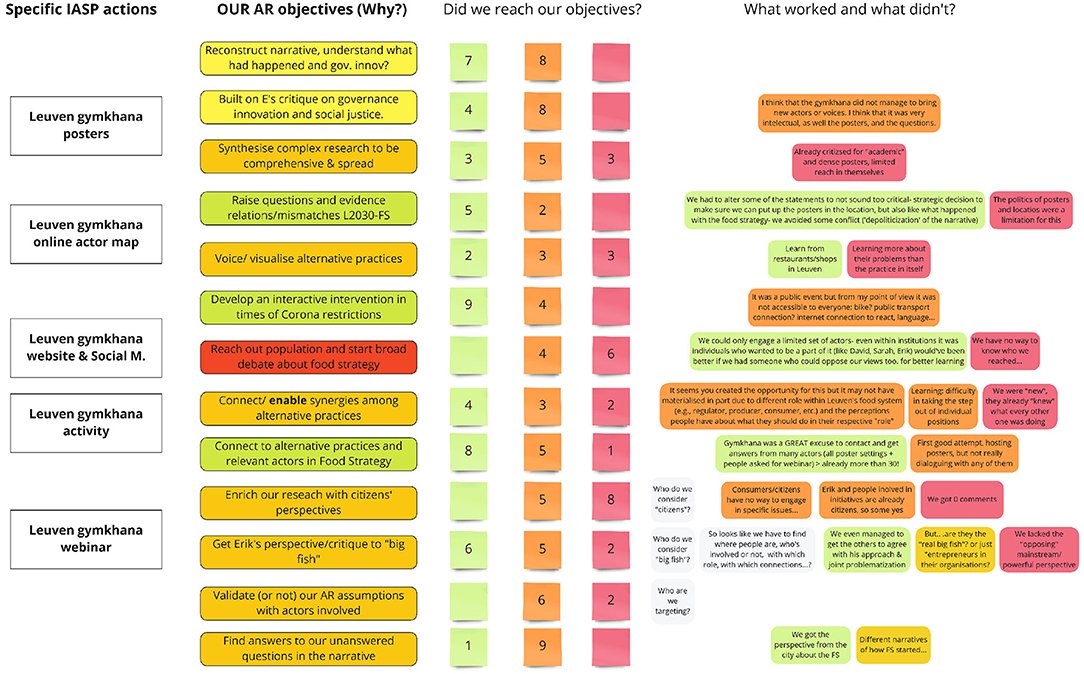

Using the insights from the first sessions, in the third session we evaluated the objectives and impact of the IASP research and interventions (Figure 5). This allowed research coordinators to further rationalize the TAR process already conducted and the IMSDP students to further understand TAR and start restructuring objectives toward the IMSDP's intervention. The only “condition” imposed by the Editorial Board was to continue with the LeuvenGymkhana concept to take advantage of the connections, partnerships and “brand” already built.

Figure 5. Screenshot from the IMSDP Miro board understanding the AR process and evaluating the IASP work to inspire further IMSDP work.

As we had done with IASP students, in the following sessions, we experimented with work across different teams and combining individual and collective reflections. This enabled deeper conversations in small groups but presented the challenge of losing specific messages and ideas when communicated during plenary sessions. Using Miro as a common whiteboard was useful to overcome such limitations and to keep track of and understand the perspectives of each group. It also provided the opportunity to reshuffle information and collectively develop new schemes during plenary sessions, as well as to go back to previous work when the group felt somewhat lost defining the next steps.

Meta-Level Inter-disciplinary Exchange About Governance Innovation: The UGADI Seminar

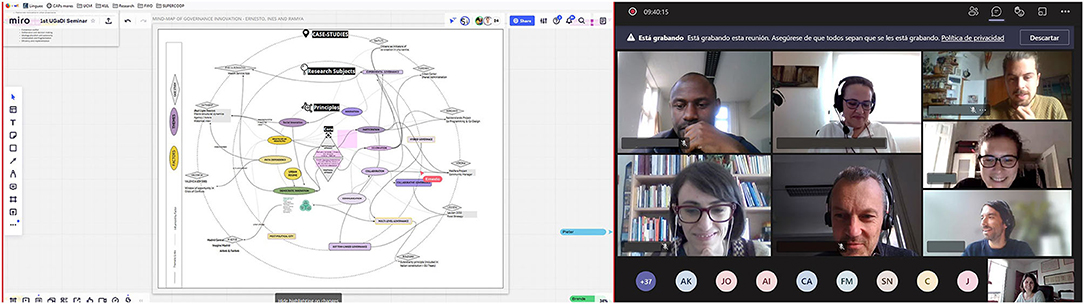

To reinforce the inter-disciplinary nature of our TAR, the research coordinators also mobilized a network of academics researching governance innovation in different contexts. For this, the Planning and Development Research Unit from KU Leuven joined the Faculty of Political Sciences from the Universidad Complutense in Madrid, the Department of Social Sciences from the University of Bologna and the School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture from the University of Edinburgh to apply for UnaEuropa Seed funding6 to set up two hybrid seminars in which different researchers and students could exchange and enrich their perspectives and approaches. Despite not getting the funding, the parties decided to continue with the organization of a hybrid seminar on 19 and 20 April 2021, attended simultaneously by researchers and professors from the participant universities and students from the 4cities module on Governance that was taking place in Madrid and the IMSDP students in Leuven.

The resulting UGADI Seminar on Urban Governance And Democratic Innovation (see Figure 5) consisted of three blocks: in Block 1 (Theoretical Exchange) professors gave theoretical and methodological lectures, in Block 2 (Research Exchange) researchers and students shared their research approaches and experiences, and in Block 3 (Collective Writing) the collective discussion continued in smaller groups and materialized through the cocreation of three texts, a mind-map and a video report7 (Figure 6). The collective reflections developed about governance innovation research will be included in the next INSIST Issue on Governance8. Moreover, the event was especially useful for our research, “forcing” research coordinators to improve their analysis and narrative of the on-going processes in Leuven and helping IMSDP students advance their understanding. The focus on governance innovation also helped clarify the focus of our collective interventions in Leuven around the governance of the Food Strategy and avoid getting lost in “content-specific details” regarding the transformation of the food system.

Figure 6. Screenshot during the UGADI Seminar Plenary session sharing the collective outcomes produced about governance innovation research.

Building a Common Understanding: Joint Problematization and Intervention Codesign

The slightly relaxed COVID regulations in the following weeks allowed physical work on campus. While hybrid meetings opened up new opportunities for interaction among those on campus, and flexibility for all members to participate regardless of their location or personal situation, it also posed extra challenges in terms of technological set up and management of group dynamics and work as we advanced in the definition of a TAR intervention. For this stage, experts in TAR from our network (Seppe de Blust, Michael Kaethler, Barbara Van Dyck, Ruth Segers, and Alessandra Manganelli) joined as tutors in specific sessions.

With the new intervention, the IMSDP team intended to overcome the limitations identified in the previous version of the LeuvenGymkhana and move forward in the facilitation of a critical debate about the Food Strategy with all actors involved and those that were being excluded in its implementation. For this, the gymkhana concept was adapted into a series of interactive guided tours on various aspects of Leuven's Food Strategy. We also identified the need for an improved communication strategy and to continue with the simplification of our analysis and schemes.

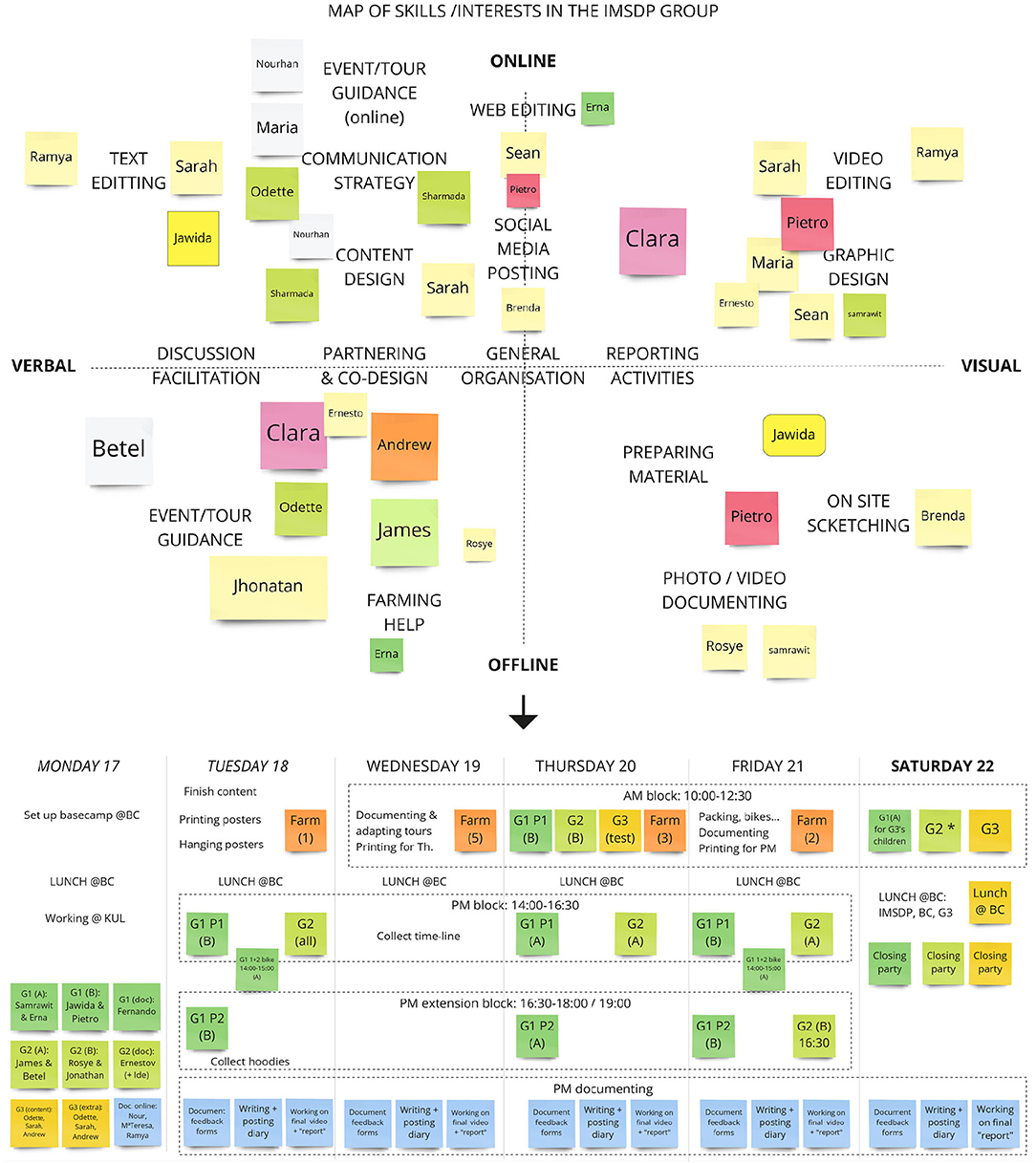

Once the intervention idea was agreed upon, the IMSDP team re-arranged in “practical teams” to cater for all the tasks needed for the design, planning and implementation of the tours. Compared to the IASP experience, this work got more professionalized, and we dedicated more time both to identify tasks and to allocate roles according to everyone's interests and skills, but also physical availability (Figure 7). This time all students took a dual role, one related to the thematic knowledge more appealing to them—by choosing the specific gymkhana they would design and guide—and a practical role according to the specific skills they could contribute, i.e., content development, graphic design, practical arrangements, social relations, web and social media management, and reporting. Depending on the objectives of the remaining sessions and the workshop activities, the team would work as per thematic or practical role.

Figure 7. Screenshot from the IMSDP Miro board negotiating the reorganization of working teams as per required tasks and personal skills and interests and the organization of work during the workshop week.

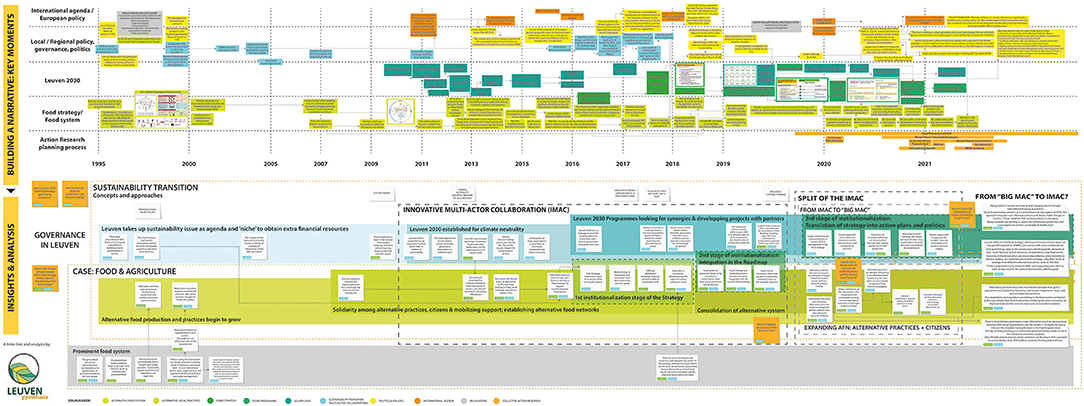

While IMSDP students focused more on planning the intervention, the PhD and Master researchers kept advancing the analysis of the trajectory of governance innovation in Leuven, in a continuous exercise of updating, reframing and feeding the analytical framework. The resulting LeuvenGymkhana Timeline (Figure 8) depicted key moments in the history of Leuven2030 and the Food Strategy, and the insights we were deriving from them. These insights were parallelly discussed with the IMSDP class during the development of the tour scripts in a mutually enriching process, and kept being updated during the tours. Through this process, we came to clarify three key issues that explained the current situation of IMACs and governance innovation in Leuven:

1. The Food Strategy has been subject to several stages of institutionalization or formalization, as the initial document got integrated in Leuven2030's Roadmap and the new Climate Policy of the city.

2. The current stage in this process of institutionalization shows that the IMAC around the Food Strategy is “splitting” in separate trajectories: (1) a “Big-MAC” led by Leuven2030 and the City where more resourceful actors of the food system can keep engaging in decisions about further implementation of the strategy and (2) a parallel consolidation of an alternative food system by alternative food practices. The former is led by the outcome-oriented project logic, more carbon-neutrality and mainstream approaches to sustainable transitions and economic-oriented interests of mainstream and bigger actors of the food system, while the latter is based on hybrid social, ecological and economic logics and on relations of trust and collaboration.

3. The split is due to a lack of care for all facilitative roles in the IMAC, as actors taking the lead in further implementation focus more on “meeting objectives” (a catalyzer role) rather than the governance of the IMAC and Leuven2030 does not perform as steward and mediator anymore.

Figure 8. Timeline gathering results and insights from the research about governance innovation and the implementation of the food strategy in Leuven used during the LeuvenGymkhana tours (Full resolution version included as Supplementary Material).

Reinventing Civic Engagement in Leuven to Reopen the Debate About the Food Strategy: The LeuvenGymkhana 2.0 Tours

The week between 17 and 22 May 2021 was dedicated to an intensive “trial and adapt” exercise of simultaneously conducting the tours, adapting the scripts, and preparing for a final event at BoerEnCompagnie, the base camp of the LeuvenGymkhana 2.0. This intervention aimed to reimagine civic engagement and experiment with alternative means of public debate that could double up as a trust-building process among actors.

Three Gymkhanas were designed and conducted with three specific themes and target audience (Figure 9). Gymkhana 1 (G1) “From farm to fork, what does it really mean?” was more targeted to young people and aimed to reopen the debate on what “sustainable and healthy food for all” means, addressing sensitive issues that had dissolved in the several steps of institutionalization of the Food Strategy. Gymkhana 2 (G2) “The Journey of our food” aimed at spotting the actors already building an alternative food system in Leuven and discussing the obstacles they are encountering, to inspire other practices to follow their example as well as further steps in the implementation of the Food Strategy. Gymkhana 3 (G3) “Food justice for all” would only run on the last day, wrapping up the discussions raised in the first two plus reconnecting with urban governance and the broader process of development of the Food Strategy and the actors involved. Specifically targeting actors working in the implementation of the strategy, this tour was designed as a trust-building platform aiming to trigger a collective reflection about the whole trajectory of the Food Strategy and inspire ways to move forward together.

Learning from the difficulties to engage relevant stakeholders for the webinar, G3 was scheduled on Saturday and combined with a closure collective meal at BoerEnCompagnie served by Bar Stan, where a video report of the LeuvenGymkhana would be screened. Our event would coincide with a farming and socializing event organized by BoerEnCompagnie, which facilitated further opportunities for exchange between participants of the Gymkhana and BoerEnCompagnie‘s community. We displayed the LeuvenGymkhana timeline as a three-meter banner at BoerEnCompagnie to support explanations during the tours and trigger further discussions about further steps in the Food Strategy.

Performing the tours allowed the team to further discuss with stakeholders and to really open debates with citizens and food initiatives, although with a limited reach (Figure 10). Despite the effort displayed in advertising our tours and personally inviting the most relevant stakeholders, only 15 people joined, most of them students or researchers from different fields. Some were actually IASP students that got to realize what their initial contribution had led to and “managed to understand what they were doing” during these tours. Only one of the five G3 participants was among the main stakeholders directly invited. The short notice of the event, its coincidence with exams period and a long weekend, and the rainy weather during the week might have hindered broader participation.

However, for us the making of three tours prototypes was in itself an objective and an excuse to further learn from, debate with, and empower stakeholders. Moreover, the resulting prototypes are valuable outcomes that actors in Leuven's food system can take over to involve more actors and recover the IMAC. For this, the chain of testing, interacting with stakeholders and partners, reflecting, adjusting and learning by doing, and a parallel work of documenting the experience and sharing it live in website diaries and social media were key. Also, the “unexpected” conversations that we maintained with stakeholders by visiting their premises and the video report of the gymkhana might have impacted the actors that are implementing the Food Strategy, as to learn better about what other actors are working on and the obstacles they encounter and inspire ways to move forward together, instead of splitting apart in their efforts.

Wrapping-Up, Valorizing Results, and Opening the Door to a New Stage of TAR

Like in previous stages, several individual and collective reflection moments were necessary to apprehend the IMSDP TAR process and results. A first step were the LeuvenGymkhana diaries and video report developed by IMSDP students. Once the IMSDP workshop was over, research coordinators kept reflecting while writing blog posts about the TAR in Medina-García's PhD blog (Medina-García, 2021) and the final Master thesis documents submitted in June (Nagarajan, 2021) and September (Castillo-Vysokolan, 2021).

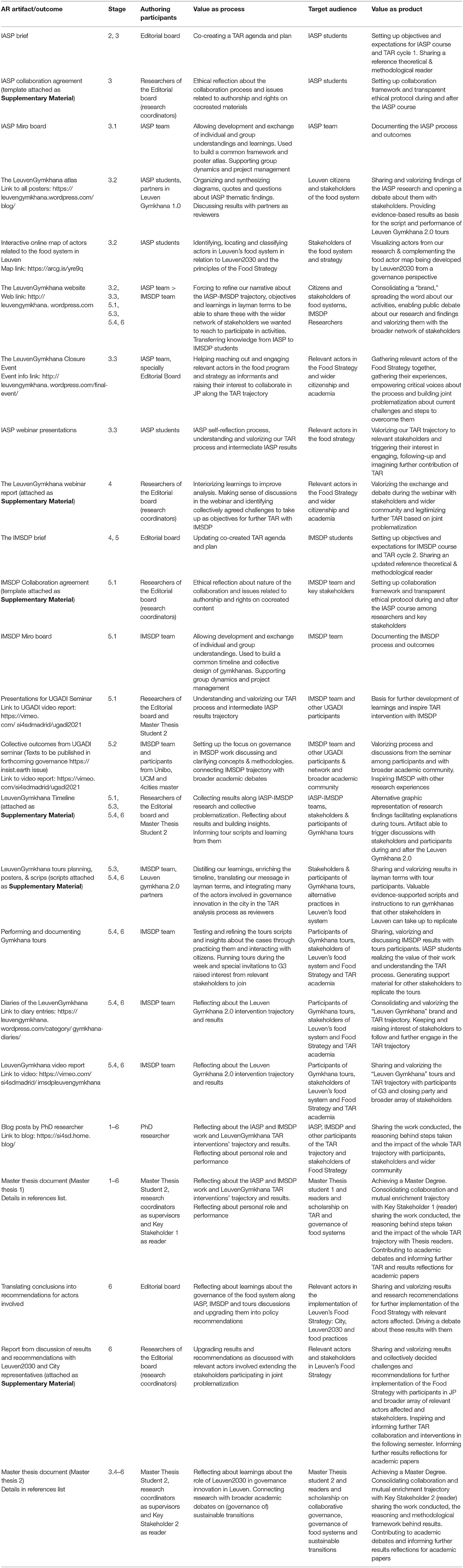

Moreover, representatives from the city of Leuven that had not been able to attend the tours showed interest in our work and requested a follow-up meeting in which the Editorial Board could share our learnings and recommendations on how to “recover the IMAC” in further implementation of the Food Strategy. Preparing this meeting helped digesting and synthesizing the gymkhana discussions and insights into recommendations, while the meeting in itself became another stage in the process of valorization and discussion of conclusions with more relevant actors. It even opened the door to starting a new stage of TAR in the following semester with a new group of IASP students involving the City in the Editorial Board. A full report of the discussion of the results and recommendations with Leuven2030 and City representatives was also developed and shared with participants and other stakeholders in Leuven.9 This open-access article and a parallel one sharing our learnings about IMACs (Medina-García et al., 2022) are another step in the continuous translation of the results in different formats and styles to valorize and mobilize them among academia and stakeholders of the processes investigated. Table 2 summarizes all the AR artifacts and activities cocreated, reflecting on their role along the AR trajectory.

Table 2. List of AR artifacts and outcomes cocreated along the process, reflecting on their role as “process” and as “outcome.”

Discussion

TAR as Social Innovation

Socially innovative TAR requires that theoretical and analytical research enriches, and is enriched by, getting immersed in the practical reality of the issues investigated and interacting with the actors involved. As a research, we tried to implicate relevant stakeholders of the ongoing IMAC processes in Leuven to our joint problematization and critical analysis of the current governance of the Food Strategy. Researchers contributed to this process contrasting academic literature, official discourses built by organizations and individual experiences shared by stakeholders. As actors new to the research context, the international researchers brought in a “naïve” and fresh reading to the stakeholders' reality and experiences that helped identify nuances, gaps and contradictions. With our analysis, we managed to reconstruct the trajectory of Leuven2030 and the IMAC governing the Food Strategy and illustrate the current “split of the IMAC.”

Meanwhile, as action, through our interventions we experimented with ways to address the challenges collectively identified, i.e., empowering citizens and alternative practices that were no longer integrated in decision-making related to Leuven's Food Strategy. The LeuvenGymkhana interventions and events provided the opportunity to re-imagine “public events” in times of physical (not necessarily social) distancing that could become a prototype for alternative and gamified modes of civic engagement and collaborative governance. Through the design and implementation of these interventions we also tested alternative governance platforms with which to recover the IMAC with the actors involved in the Food Strategy. The LeuvenGymkhana did not aim to reinvent the wheel but rather focused on co-creating a flexible framework answering to the requirements of IMACs in Leuven that could be adapted into a platform for public debate and simultaneous trust-building. As such, it became a mini-IMAC in the landscape of governance innovation in Leuven.

After all, our experience showed how, while increasing our understanding about governance innovation in Leuven, our action research activities were socially innovative and empowering toward actors that are being excluded in further implementation of the Food Strategy. Not only did we manage to provide evidence for the emerging exclusion mechanisms causing the “split of the IMAC,” but we also developed and tested new participatory methodologies that could be used to recover the IMAC around Leuven's Food Strategy and increase civic engagement of all types of actors in Leuven's food system. From this perspective, our TAR trajectory becomes a case study of IMAC in itself. Thus, the analysis or the trajectory we developed through this paper informs both methodological discussions on TAR and literature on governance and social innovation.

Positionality, Negotiation, and the Key Role of an Editorial Board in TAR

TAR is a continuous process of collaboration and negotiation that starts with a preliminary institutionalist analysis of the topic of research and researchers taking a stance in relation to positions within the field of research and the ecosystem of actors affected. “Content specific” issues related to the food system and power dynamics identified in the institutionalist analysis inform each other in the definition of the researchers' position and the TAR trajectory, and also evolve along the research trajectory. Through the design of the Editorial Board and the IASP-IMSDP research agenda, the research coordinators deliberately and consciously sided with specific critical voices on the implementation of the Food Strategy and smaller alternative food practices in Leuven as a way to contribute to ongoing IMACs in Leuven. Further research by the IASP and IMSDP teams evidenced the dynamics behind stakeholders' critiques and so empowered the actors that had raised them.

Being transparent about the interests, expectations, resources and potential contribution of researchers and stakeholders to the process was crucial to frame the TAR trajectory and to engage (or discourage) participants along the way. As the team increased—integrating IASP, IMSDP and UGADI researchers and a broader array of stakeholders from Leuven's food system during the LeuvenGymkhanas—so did the international, cultural and academic diversity of the research team and the expectations and practical interests of stakeholders involved. Furthermore, during the broader joint problematization among researchers and practitioners, participants had to deal with evolving and hybrid roles, and combine their individual multi-dimensional interests and experiences with the perspectives and logics of the organization(s) they represented. This required a continuous reflection and negotiation about the contribution of the TAR both from a long-term and short-term perspective, and adapting TAR objectives and the collective work plan accordingly. Some TAR activities and approaches aimed to contribute to broader governance transformation, such as documenting and recognizing alternative food practices that were not being valorized in academic and political arenas, finding the way to empower critical voices by reaching decision-makers, and strengthening relations among actors and facilitating further collaborations. Meanwhile, other activities and practical decisions dealt with specific concerns and needs of stakeholders involved, like setting the spotlight on alternative practices to extend their outreach among citizens, identifying and voicing their specific obstacles and needs, or paying for time and resources invested by stakeholders in the TAR trajectory with labor in BoerEnCompagnie's farm or contracting catering services from gymkhana partners.

Reflecting on our experience, we realize the relevance of setting up an Editorial Board that performed as steward of the whole TAR process and as “coordinating team” managing the resulting complex network of stakeholders and researchers. The Editorial Board was in itself a negotiation platform between research and practical action and played a key mediating role in co-defining courses of action and managing engagement and communication of and among participants. It also placed leading researchers and key stakeholders in a privileged position to identify and guide the catalyzing potential of each individual stakeholder and the evolving collective research and action.

Maximizing Stakeholders' Engagement and Trust-Building Through Incremental TAR Interventions

In line with the mainstream discussions in AR literature (Kindon et al., 2007), our TAR in Leuven evolved as a series of often simultaneous stages of analysis, joint problematization, collective action and reflection moments. The strategic decision to integrate two academic courses within the TAR trajectory allowed us to incrementally build our research through a series of TAR cycles and to increase the number of researchers and stakeholders contributing to it. In each cycle, a group of students took ownership of previous work and designed and implemented a TAR intervention that enriched the collective understanding, increased the action outreach of the research and involved a broader array of stakeholders, i.e., citizens, experts and academics, alternative food practices, coordinators from Leuven2030, and local politicians and civil servants.

Our approach resulted in a virtuous combination of project-based short-term interventions and potential contributions to long-term governance transformations that progressively increased participants' level of engagement. For students, not only was their participation a valuable learning-by-doing experience about planning and TAR processes, but also the feeling of contributing to something “real” and seeing direct impact and further application of their work increased their commitment. For stakeholders, the possibility to participate in individual activities eased their initial engagement, normally as informants or partners in events. Yet, becoming aware that activities were part of a longer TAR process connected to academic courses and graduate research projects that opened the door to extend the collaboration, motivated them to increase their commitment in further stages and activities and to imagine future contributions of the TAR to their specific interests and needs. Moreover, the fact that all researchers were new to the research context valorized the contextual and practice-related knowledge and contribution of stakeholders from the beginning, which eased building trust and horizontal and collaborative relations between researchers and practitioners.

The process of upgrading methodologies and results from one experience to the following stage also increased the quality, rigor and legitimacy of the TAR and, thus, the chances to keep engaging relevant stakeholders. The consolidation of the “LeuvenGymkhana” brand—with dedicated logos, website, social media profiles, and even tour guide uniforms- and regular communication of advancements and forthcoming activities to relevant stakeholders and previous participants were key. As a result, the research trajectory was more and more recognized and taken seriously by stakeholders, which raised interest from new ones to join.

We acknowledge, however, that our engagement among citizens, decision-makers and the most powerful actors in Leuven2030, the local administration and the food system in Leuven has been slow and limited. We might just have managed to engage the “pioneers” or enthusiastic stakeholders within each actor network. Still, we hope that facilitating an arena for trustful and secure exchange and building collective outcomes will empower and increase the legitimacy of each of these actors in their networks.

Navigating Uncertainty Combining Individual and Collective Learning in TAR

Continuous integration of participants and adaptation of our work added complexity and uncertainty to the process, and required time to allow each participant to connect their background and perspectives with the work already advanced to empower them in further joint problematization. While flexibility and codesign are core for TAR, this methodology could be frustrating at times, since it did not have a pre-determined agenda or framework to develop. This was specially challenging for participants—both stakeholders and students—that were not used to navigating uncertainty through collective negotiation and preferred having a set target and framework. Within each TAR stage, the research coordinators performed as project managers, responsible for guiding group dynamics, managing uncertainty and combining facilitation of common understanding with engagement of every participant.

In terms of group dynamics, both IASP and IMSDP teams started with collective sessions to build a collective understanding of TAR and the issues at stake, then split in thematic research teams and then rearranged according to practical tasks required to conduct the TAR intervention. In this process, research coordinators juggled with their stewardship, mediating and catalyst roles as they planned each working session. One of the biggest challenges was to combine personal and collective learning trajectories with the urgency of reaching valuable outcomes, and to manage ambitions of the process accordingly. The main struggle was to find the balance between enabling sufficient spaces for collective discussions, using Editorial Board meetings between sessions to discuss advancements and define further steps, and keeping everyone on board by continuously sharing such decisions and the rationale behind them. In an adaptive trial-and-error experience, some sessions were more exploratory and discursive, investing the time to let all voices be heard, and others were more directed and executive in order to reach agreements and get things done.

The intensity of mediation between individual and collective learning was at its highest when time was pressing to design an intervention for the IMSDP workshop. Then, while students in Leuven attended a live workshop, research coordinators and online participants had an extra session where they managed to build on previous discussions and design a prototype of gymkhana. However, in the next session, offline students only partially grasped the reasoning behind the prototype. As a result, only some managed to integrate and upgrade the learnings about IMAC trajectories in Leuven, understand the TAR intervention and perform as convinced tour guides, while others resigned to follow instructions hoping that they were contributing to whatever was occurring. IASP students that attended the tours shared a similar feeling, recognizing that only then did they realize the meaning and contribution of their work. This illustrates that the reflection and learning processes of participants follow different rhythms and extend further than their involvement in particular TAR moments. Yet, when time presses, research coordinators and early adopters have to push forward taking decisions hoping that the team will trust and follow them. This affects the enthusiasm of some individuals, with the risk that only those participating in such decision-making moments remain convinced about the collective work.

In terms of managing personal roles and responsibilities within the IASP and IMSDP teams, this was based on negotiations of personal resources, skills and interests. The hybrid nature of the IMSDP team also affected task allocation. Eventually, students in Leuven managed on-site practicalities and guiding and documenting the tours, while online students became both “content experts,” improving the Gymkhana scripts, and the “collective consciousness” of the group, as they reviewed and synthesized all pictures, videos and audio chronicles from live participants to share what was happening with the broader community through the gymkhana diaries. These group negotiations and personal commitments, for example when students became “experts” in certain topics and tasks, professionalized the work within the team, while causing each personal experience within the TAR was “unique” even among students.

The Agency of Interaction: Questioning Standards and Ensuring a Fair and Flexible Collaborative Framework

As we have illustrated, TAR is based on joint problematization, collaboration, and negotiation, and the whole trajectory is built and shaped through the interaction among participants, building on previous steps. Thus, interaction has an agency in TAR, molding and guiding the collective learning and cocreation processes. As such, TAR interactive activities and interventions cannot be replicated from previous experiences but need to be deliberately designed and implemented in each TAR trajectory (and stage). In our experience, the Editorial Board designed each IASP and IMSDP session building on previous work and interactions with stakeholders. Neither are LeuvenGymkhanas “methodologies” that can just be replicated elsewhere. Instead, they are the outcome of the institutionalist analysis of the case under study and the several cycles of interaction among stakeholders and researchers involved in the TAR process.

As stewards of the TAR, and aware of these complexities, the research coordinators kept discussing the ethics, rigor and procedural appropriateness of the collaboration process and the impact and further possibilities of its outcomes. Not only was this required by the university and academia, but a responsibility implicit in TAR. This included reflecting about and questioning academic research integrity, ethics and authorship standards and carefully designing the infrastructure set in place to ensure a fair and collaborative framework.