- 1Center for Biodiversity and Conservation, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY, United States

- 2Sustainable Food and Bioenergy Systems, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT, United States

- 3Institute of Human Nutrition, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY, United States

- 4Faculty of Land and Food Systems, Centre for Sustainable Food Systems, University of British Columbia, East Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada

- 5Department of Urban-Global Public Health, School of Public Health, Rutgers University, Newark, NJ, United States

- 6School of Public Health, Oregon Health and Science University and Portland State University, Portland, OR, United States

- 7Department of Health and Behavior Studies, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, NY, United States

- 8Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Environmental Biology, Columbia University, New York, NY, United States

- 9Sustainability Institute, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH, United States

- 10Department of Environmental Studies, State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Syracuse, NY, United States

Sustainable food systems education (SFSE) is rapidly advancing to meet the need for developing future professionals who are capable of effective decision-making regarding agriculture, food, nutrition, consumption, and waste in a complex world. Equity, particularly racial equity and its intersectional links with other inequities, should play a central role in efforts to advance SFSE given the harmful social and environmental externalities of food systems and ongoing oppression and systemic inequities such as lack of food access faced by racialized and/or marginalized populations. However, few institutional and intra-disciplinary resources exist on how to engage students in discussion about equity and related topics in SFSE. We present perspectives based on our multi-institutional collaborations to develop and apply pedagogical materials that center equity while building students' skills in systems thinking, critical reflection, and affective engagement. Examples are provided of how to develop undergraduate and graduate sustainable food systems curricula that embrace complexity and recognize the affective layers, or underlying experiences of feelings and emotions, when engaging with topics of equity, justice, oppression, and privilege.

Introduction

Food systems1 are foundational drivers of change and power relationships on local to global scales, cutting across social, political, economic, health, and environmental systems. Poor quality diets are among the top contributors to the global burden of disease (Murray et al., 2020), and producing the food that comprises these diets puts pressure on the earth's systems through major contributions to greenhouse gas emissions, fresh water use, and biodiversity loss (Willett et al., 2019). Our current industrial food systems are not effectively contributing to the health of people or the planet, with notable disparities for the most vulnerable populations and regions (Global Nutrition Report, 2020). However, discussions about “fixing a broken food system” in order to “feed the world” assume that food systems of the past functioned to produce equitable outcomes. This framing overlooks the violences of racial inequities, colonial histories, and disparities in power between privileged groups and marginalized groups that continue to be subject to harmful social and environmental externalities of food systems and ongoing oppression and systemic inequities due to exploitative globalization (Cadieux and Slocum, 2015; Holt-Giménez and Harper, 2016; Holt-Giménez, 2017)2.

The way in which food is produced and moves through food supply chains impacts laborers and other stakeholders as well as consumer food environments, including the availability, affordability, acceptability, and sustainability of foods (Downs et al., 2020). Systems thinking identifies innovative ways to reorient food systems toward the production and consumption of just, equitable, healthy, and sustainable diets and toward prioritizing access to affordable and culturally relevant food for all (Cadieux and Slocum, 2015; Valley et al., 2018; Iowa State University Extension and Outreach, 2021). Food systems thinking is an approach that goes beyond the conventional focus on linear and distinct food system elements and that moves toward accounting for more complex, interconnected, and dynamic linkages (Ingram et al., 2020).

Given the complexity of the problems within our current food systems, there is a need for people from diverse disciplines trained in food systems thinking (cf. Ingram et al., 2020), regardless of the sector or discipline. Often described as multi-, inter-, and trans-disciplinary, sustainable food systems education (SFSE) is rapidly advancing, with a signature pedagogy that serves as a framework in which future practitioners in this field are educated and equipped to both compete in a dynamic and heterogenous job market and foster new vocational opportunities for food system transformation (Valley et al., 2018). However, we argue that this training must center equity,3 particularly racial equity and its intersectional links with other inequities (Ebel et al., 2020; Valley et al., 2020). Concepts of sustainability often focus on environmental aspects with an “equity deficit” that fails to acknowledge connections with social needs, welfare, and economic opportunity for all (Agyeman et al., 2003). Several U.S.-based organizations, from the Sustainable Agriculture Education Association4 to the Inter-Institutional Network for Food, Agriculture, and Sustainability5 to the Agriculture, Food, and Human Values Society6, are starting to compile resources for their membership on how to teach about food systems in ways that center equity given the urgent need to address adverse effects of food production and distribution faced by marginalized populations.

An advancement toward centering equity in SFSE requires a fundamental shift from siloed, disciplinary ways of “seeing” the world to systemic approaches that embrace and work through complexity, uncertainty, and relationships (e.g., de Sousa Santos, 2014). Systemic ways of knowing necessitate adopting a pluralistic approach to acknowledging the importance of diverse stakeholder perspectives in conceptualizing issues and recognizing outcomes and impacts of interventions. An equity-centered approach draws from an emergent understanding of relational systems thinking and cross-epistemological research and teaching (Goodchild, 2021). Sustainable food systems education's engagement with pluralism and equity requires an awareness of historical and current power relations among stakeholders and their communities in order to interrupt the reproduction of systems of oppression within food systems. Developing systems thinking capacities within SFSE programs must center equity in ways that interrupt and interrogate colonialism, white supremacy, patriarchy, heteronormativity, ableism, and the “monoculture of the capitalist logic of productivity” (de Sousa Santos, 2014, p. 174). Not doing so is likely to reproduce the harms and violences of our current food systems (Giordano, 2017; Stein et al., 2017; Bansal, 2018), such as attempts to improve food system outcomes that fail to give explicit attention to race and racializing processes, thereby reproducing racial inequities (Slocum, 2007; Sullivan, 2014; Valley et al., 2020).

Rather than providing an extended analysis of the “why” of centering equity, here we write about the “how” in our own context. This paper describes efforts at several institutions, including multi-institutional collaborations, to develop and apply pedagogical materials that center equity while building students' skills in systems thinking, critical reflection, and affective engagement.

Centering Equity in Teaching and Framing Food Systems

The cornerstone of our vision for SFSE pedagogy is equity and its full integration into curricula at the undergraduate and graduate level, instead of being discussed in one-off or certain class sessions. What will it take to bring about this vision? Here, we describe two multi-institutional collaborations and efforts by faculty at three different institutions to develop curricula that frame food systems in ways that center equity while fostering essential process skills.

Multi-Institutional Collaboration for Developing Curriculum to Center Equity

Teaching Food Systems Community of Practice

Fully integrating equity into sustainable food systems curriculum necessitates collective work across institutions. We support that a collaborative mechanism such as a Consortium or a Community of Practice (CoP) is critical for the adoption and full integration of equity into curricula. Here, we provide an example of our Teaching Sustainable Food Systems CoP that has been a collaborative mechanism for educators in North America to identify, develop, review, and share curriculum materials for SFSE.

Specifically, the “Teaching Food Systems CoP”7 was launched in 2016 by faculty members at Columbia University, in collaboration with the Center for Biodiversity and Conservation at the American Museum of Natural History, in parallel with the redesign of an undergraduate food systems course (described below). The goals of the CoP are to convene academics and practitioners focused on SFSE, to: (1) support and grow a CoP for developing and implementing curricula in food systems courses; (2) share materials using systems thinking frameworks to teach about food systems; and (3) foster assessment tools on student learning in systems thinking.

Several CoP members collaborated on a study to determine the extent to which SFSE programs in the U.S. and Canada address equity and proposed an equity competency model to support the development of future professionals capable of dismantling inequity in the food system (Valley et al., 2020). The authors argue that the limited number of SFSE programs explicitly stating equity terms (17%) indicates a significant gap between the knowledge, skills, and attitudes being called for by food justice scholars and activists and the educational outcomes associated with institutions responsible for preparing future professionals. Given the findings, the CoP Subcommittee on Equity, Inclusion, Diversity, and Justice and Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (EIDJ and IPLCs) developed training materials that explore how teachers and students in undergraduate and graduate STEM classrooms can engage with EIDJ content in ways that recognize affect—feelings and emotions (Isen et al., 1987). Since affect controls cognitive behavior (Isen et al., 1987; Carver and Scheier, 2001), we support that affect and affective states including emotion, mood, interpersonal stance, attitudes, and personality traits (Scherer, 2005) are recognized within SFSE learning contexts and are critical to centering equity in this context. It is important for sustainable food systems educators to consider the words of Zembylas (2013): “classrooms are not homogeneous environments with a common understanding [or experience] of oppression, but deeply divided places where contested narratives are steeped in the politics of emotions to create complex emotional and intellectual challenges for teachers” (p. 181).

During training sessions with fellow CoP members, the EIDJ and IPLCs Subcommittee asked educators to consider the role of emotion and affective state in key relationships in teaching and learning [between students and teachers, subject matter, fellow students, and developing self, as per Quinlan (2016), as well as between teacher and teacher]. This approach draws from the work of Fawaz (2016) in that explicit attention to the variation and shifting intensity of affective responses can result in productive aspects of encounters with pain and trauma, working to expand students' feelings in order to encourage investment in redressing issues of structural oppression, such as racism, sexism, homophobia, and colonialism. In sustainable food systems, these issues are central and foundational. Ultimately, critical pedagogical strategies must function within the larger context of how structural inequality is operationalized in departments and across campuses. It is imperative to move in the direction of democratic pedagogy, informed by transformational connections coupling the classroom and society. This approach connects education with social and political change, making the classroom a lens in which change and action is understood (de los Reyes et al., 2001), especially when local framing can aid qualitative inquiry8 (Stanley and Haynes, 2019).

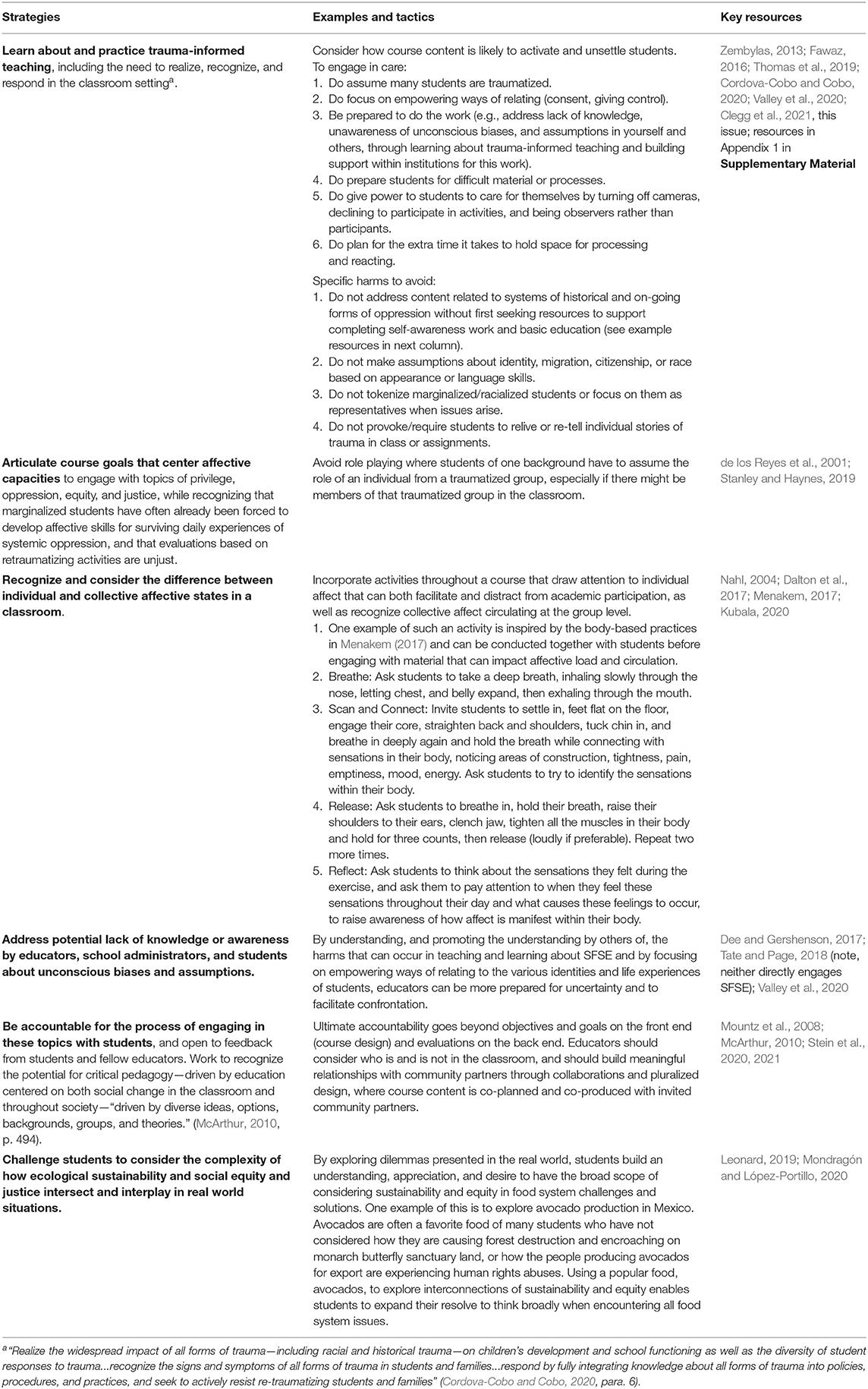

At the same time, such pedagogies pose risks to traumatized students and they demand comprehensive preparation, considerations of safety, and accountability for student well-being (also see Clegg et al., 2021, this issue). Requiring systemically traumatized students to engage affectively can reinscribe marginalization and exclusion from educational environments (Dalton et al., 2017; Cordova-Cobo and Cobo, 2020; Wahl, 2021). Institutional support and resources for this critical trauma-informed preparation may not be as readily available as it should be. Nevertheless, the dual moral imperatives of addressing injustice on the one hand, and not traumatizing already marginalized students on the other, remain in tension. Much of this critical trauma-informed education is both readily available and of basic professional and moral importance. Through recognizing the necessity of considering affect in SFSE curricula, Subcommittee members have identified strategies for developing capacities to be safe, self-aware, accountable, and intellectually generative when engaging with EIDJ content (Table 1; also see Appendix 1 in Supplementary Material for supplementary resources for educators).

Table 1. Strategies for educators to consider the role of emotion and affective state when centering equity in sustainable food systems education.

Inclusive Food Systems Curriculum USDA Higher Education Challenge Project

Faculty from Montana State University, University of British Columbia, and University of Minnesota launched the Sustainable Food Systems Consortium in 2013 and have been collaborating on a project titled “Advancing an Inclusive Food Systems Curriculum based on a Signature Pedagogy” supported by a USDA Higher Education Challenge (HEC) grant focused on creating inclusive and replicable 4-year core curricula models for Baccalaureate degree-level SFSE programs, guided by a signature pedagogy model of cognitive maturation in young adults (Valley et al., 2018) as well as methods for enhancing inclusion of under-represented students. These curricula models include a range of materials such as curriculum maps, lesson plans, hands-on course activities, and evaluation tools that are aligned to the sustainable food systems signature pedagogy including holistic and pluralistic ways of understanding sustainability challenges, experiential learning, and participation in collective action projects. The learning approaches of the sustainable food systems signature pedagogy are recognized to be inclusive of diversity of perspective and supportive of underrepresented students (Valley et al., 2018) as well as catering to multiple learning styles essential for designing inclusive curricula that account for students' educational, cultural, and social background and experience (Smith, 2002). Additional inclusion approaches being implemented by participants of this project for centering equity in the curriculum include: (1) focus on complex issues of public welfare; (2) development of civic identity; (3) appreciation of different forms of knowledge and understanding; (4) peer support and; (5) skill development for addressing food system issues in multi-sector and multi-cultural settings (Whittaker and Montgomery, 2012).

Participants of this project further developed adaptable learning outcomes for SFSE where each learning outcome is framed with consideration of justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion (Ebel et al., 2020). As an example of a product of this effort, members of the collaboration at the University of British Columbia published the Just Food Educational Resource9, a teaching and learning open education resource for post-secondary instructors and other educators interested in teaching food justice and equity.

Additionally, participants of this project collaborated with the Teaching Food Systems CoP to offer the “Teaching Sustainable Food Systems in Our Times Sandbox Webinar Series10,” to provide professional development opportunities for educators to enhance and share knowledge and skills regarding justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion. Multiple webinars in this series provide examples of how to integrate equity-minded curriculum into teaching and learning including through self-reflection, storytelling, cultural protocol, positionality, Indigenous methodologies, multicultural texts, and community partnerships.

Most recently, HEC grant collaborators partnered with Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures11, an arts/research collective based at the University of British Columbia aiming to identify and deactivate colonial habits of being and to gesture toward the possibility of decolonial futures. Collaborators facilitated a 6-week professional development program for sustainable food systems educators in the U.S and Canada to explore contributions of decolonial perspectives and embodied practices in relation to SFSE.

Program and Course-Level Efforts

Montana State University

Faculty of the Master of Science in Sustainable Food Systems and Bachelor of Science in Sustainable Food and Bioenergy Systems at Montana State University (MSU) have been centering equity in the curriculum through evaluation and modification of course content. Specifically, the faculty have been developing content that emphasizes systems thinking, critical and deep reflection, interdisciplinarity, collaboration and communication with diverse stakeholders, future visioning and design, practical skills, experiential learning, and participation in collective action projects (Jordan et al., 2014; Valley et al., 2018). Most recently, MSU faculty have been revising existing curriculum of core courses in the sustainable food systems programs to better align with consideration for equity-minded approaches and content. For example, the “Food Environments and Sustainable Diets” graduate course expanded its focus of examining linkages between food environments, food security, diets, sustainability, and health within the frameworks of socio-ecological theory and policy to also include linkages with equity. Each of the five course units aligned to different dimensions of food environments and sustainable diets were modified to include content and assignments focused on health equity, food access, affordability, cultural relevance, food sovereignty, and Indigenous peoples' food systems. In addition, students of this course participated in the 21-day Racial Equity Habit Building Challenge developed by Food Solutions New England12 as an experiential assignment. Following participation in the Challenge, students engaged in reflection regarding their experience through pod discussions and written reflections, including their perspectives of applying learnings and awareness to their work in the food system. The course syllabus for “Food Environments and Sustainable Diets” can be found in Supplementary Material.

Rutgers University

Rutgers School of Public Health's Public Health Nutrition Concentration within its Master of Public Health program has also been centering equity within its curriculum. Two of the required courses, “Global Food Systems and Policy” and “Global Food and Culture” were designed to provide students with a deeper understanding of the elements of the food system and how they influence nutrition, health, environmental, social, economic, and equity outcomes. Equity is addressed throughout these courses in lecture content, assigned readings, videos and podcasts, in-class discussions, and assignments.

Assignments include reflections that require students to critically think about topics such as cultural appropriation of food, how food production systems influence our diets, how to intervene within the food system to improve health and equity outcomes, among others. By encouraging students to critically examine the root causes of inequity throughout our food systems they will be better positioned to identify solutions aimed at addressing it in their future work. Course syllabi and descriptions of the assignments can be found in Supplementary Material.

Columbia University

First developed and offered by Columbia University's Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Environmental Biology in 2011, “Food, Ecology, and Globalization” was a broad survey course for science and non-science majors with a focus on the factors that influence food choice and the implications of those choices at many scales. In 2018 and 2020, a core team of instructors redesigned the course to more intentionally center racial equity and food justice, working with students through each class session to explore the context for how racism and equity operate within food systems with a key learning outcome that students be able to understand and describe why equity is at the heart of food system transformation. For example, in 2020, the core team collaborated with Spiller (UNH) to develop a new course session “Introduction to Systems Thinking as a Tool For Understanding Food Systems and the Role of Racism in Food Systems.” During this virtual session, students were introduced to a framework for understanding levels of racism developed by Race Forward: The Center for Racial Justice Innovation (2014), and applied this framework to food systems, then worked in breakout groups to use the systems thinking tool “rich pictures” to visualize the topic and analyze the role of racism within food systems. This session, and several others throughout the course, focused on the use of innovative tools to bridge different levels of content knowledge and surface systemic drivers of social-ecological systems (several of the materials used in the course were published by the Network of Conservation Educators and Practitioners13, see Betley et al., 2021a,b, and Paxton et al., 2021). The course syllabus and descriptions of the assignments can be found in Supplementary Material.

Discussion

Given the harmful social and environmental externalities of food systems and ongoing oppression and systemic inequities, it is critical for equity, and particularly racial equity, to be a central focus in efforts to advance SFSE. However, few resources exist regarding how to engage students in equity and related topics in SFSE. Here, we provide examples of multi-institutional collaborations and program efforts to develop and apply pedagogical materials that center equity while building students' skills in systems thinking, critical reflection, and affective engagement. Importantly, we support collaborative mechanisms for identifying and sharing pedagogy such as the Teaching Food Systems CoP and the Inclusive Food Systems Curriculum USDA HEC project. These are examples of multi-institutional collaboratives to facilitate co-development of pedagogical approaches to teaching and framing food systems that center equity.

All of the efforts we describe have reinforced to us, as educators, the need to engage both colleagues and students in these equity-centered discussions, and the need for continual professional development to improve the ways in which we engage. For example, simply adding content about racial equity to a course syllabus is insufficient and can perpetuate harms against racialized students who may be systemically traumatized. We encourage sustainable food systems educators to carefully study and consider how they incorporate affect in their pedagogical approaches, with strategies presented in Table 1 as a possible starting point including specific tactics that have been successfully employed in our classrooms. We also encourage the development, expansion, and strengthening of new and existing multi-institutional collaborations that broaden our understanding of how best to develop future professionals capable of effective decision-making in a complex world, and allow educators to share resources and lessons learned from varied and iterative approaches across diverse student populations.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

SAh, SAk, EB, ES, LT, and WV led the conception and design of the perspective. DC, BI, LT, and WV developed content on affective considerations for educators when engaging with EIDJ content. EB and ES led the drafting of the manuscript and all authors contributed to writing and revision. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published.

Funding

The material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) under Grant No. 1711411 and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Higher Education Challenge Grant, National Institute of Food and Agriculture (Award Number: 2018-70003-27649). We also received generous support from the Columbia University Office of the Provost, Columbia University Center for Teaching and Learning, Columbia University Institute of Human Nutrition, and The Chapman Perelman Foundation. Support for this manuscript also came from Lynette and Richard Jaffe, and the Jaffe Family Foundation. The Teaching Food Systems CoP was funded by an unrestricted educational grant from Pharmavite, LLC to Columbia University's Institute of Human Nutrition. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Author Disclaimer

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation and the United States Department of Agriculture.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Sarah Bergren for her dedicated support for the Teaching Food Systems Community of Practice. We acknowledge the Indigenous Nations and Peoples on whose traditional and ancestral homelands the institutions represented in this paper and its authorship are located. We recognize the longstanding significance of these lands, including ceded and unceded territories, for Indigenous Nations and Peoples past, present, and future. We believe that awareness of the resilience and flourishing of Indigenous Nations and Peoples in the face of historical and ongoing settler-colonialism, exclusion, coercion, and erasure is critically important. We are committed to building and nurturing relationships with Indigenous communities to address and overcome the legacy of these impacts in our own educational institutions and beyond, to disrupt and dismantle colonialism, and to celebrate and amplify the voices of Indigenous communities. The American Museum of Natural History, Columbia University, and Rutgers University are located on the traditional and ancestral homelands of the Lenape people. Montana State University stands on the traditional homelands and ancestral territory of the following Indigenous Nations and Peoples: the Apsáalooke (Crow), Ktunaxa (Kootenai), Niimiipuu (Nez Perce), Očhéthi Šakówiη (Lakota), Piikani (Blackfeet), Qlipse (Pend Orielle), Seliš (Salish), Shoshone, and Tsétsêhéstâhese (Northern Cheyenne). Oregon Health and Science University and Portland State University are located on the traditional and ancestral homelands of the Multnomah, Kathlamet, Clackamas, Tumwater, and Watlala bands of the Chinook, the Tualatin Kalapuya, Molalla, Wasco, and many Indigenous nations of the Willamette Valley and Columbia River Plateau. The State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry is located within the original territory of the Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois, Confederacy. The Vancouver campus of the University of British Columbia is located on the unceded territory of the xwmeθkwey'em (Musqueam) people. The University of New Hampshire is located on the traditional lands of the Abenaki, Pennacook, and Wabanaki people. We encourage members of academia from all disciplines to work to understand the history of the lands where they live and work, develop meaningful relationships with the Indigenous Nations and Peoples of these places, and take action to support Indigenous communities. These relationships and dialogues can also help inform respectful and carefully considered acknowledgments of Indigenous Nations and Peoples and Native land and territories in professional endeavors where appropriate, including curricula, institutional websites, presentations, and messaging, as well as publications in peer-reviewed journals and gray literature.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2021.737434/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Data Sheet 1. Appendix 1: Selected training and resources for educators to Supplement Table 1.

Supplementary Data Sheet 2. Syllabus for Food Environments and Sustainable Diets (Montana State University).

Supplementary Data Sheet 3. Syllabi for Global Food Systems and Policy and Global Food and Culture (Rutgers University).

Supplementary Data Sheet 4. Syllabus for Food, Ecology, and Globalization (Columbia University).

Footnotes

1. ^Many people, particularly those from Indigenous and local communities, conceptualize food systems as encompassing the dynamic and reciprocal relationships between people and the places and spaces where we acquire food, prepare food, talk about food, exchange food, or generally gather meaning from food. Others focus more on elements of the food supply chain: “the elements (environment, people, inputs, processes, infrastructures, institutions, etc.) and activities that relate to the production, processing, distribution, preparation, and consumption of food, and the output of these activities, including socio-economic and environmental outcomes” (HLPE, 2017, p. 23). Regardless, food systems are deeply embedded elements of our daily lives and generate impacts across scales.

2. ^For expanded debates between philosophies of oppression that go beyond our brief applied perspective, see Nussbaum (1993), Charusheela (2009), and de Sousa Santos (2014). We base our perspective on the work of the Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures collective (e.g., Stein, 2019) and Mignolo's (2011) colonial matrix of power which addresses the interrelated facets of racism, colonialism, capitalism, enlightenment humanism, the nation-state, etc.

3. ^Forms of equity include racial, age/generational, ability, class/economic, culture/ethnicity, gender, health (physical and mental), livelihood/employment, political, religion, sexual orientation, and urban/rural, among other categories of social differentiation.

4. ^Sustainable Agriculture Education Association: https://sustainableaged.org/.

5. ^Inter-institutional Network for Food, Agriculture, and Sustainability: https://asi.ucdavis.edu/programs/infas.

6. ^Agriculture, Food, and Human Values Society: https://afhvs.wildapricot.org/.

7. ^Teaching Food Systems Community of Practice: https://tinyurl.com/44mkzfca.

8. ^As quoted in an interview of scholar Yvonna Lincoln: “There are plenty racial and social injustice issues close to our own institutions, in places where we can explore, with critical qualitative research, scenarios of oppression, inequity, discrimination, and make compelling cases for serious policy revisions” (Stanley and Haynes, 2019, p. 1921).

9. ^Just Food Educational Resource: https://justfood.landfood.ubc.ca/.

10. ^Teaching Sustainable Food Systems in Our Times Sandbox Webinar Series https://waferx.montana.edu/sandbox_webinar_series.html.

11. ^Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures: https://decolonialfutures.net/.

12. ^21-day Racial Equity Habit Building Challenge developed by Food Solutions New England: https://foodsolutionsne.org/21-day-racial-equity-habit-building-challenge/.

13. ^Network of Conservation Educators and Practitioners: https://ncep.amnh.org/.

References

Agyeman, J., Bullard, R., and Evans, B., (eds.). (2003). Just Sustainabilities: Development in an Unequal World. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Bansal, D. (2018). Science education in India and feminist critiques of science. Contemp. Educ. Dialog. 15, 164–186. doi: 10.1177/0973184918781212

Betley, E., Sterling, E. J., Akabas, S., Gray, S., Sorensen, A., Jordan, R., et al. (2021a). Modeling links between corn production and beef production in the United States: a systems thinking exercise using mental modeler. Lessons in Conservation 11, 26–32. Available online at: https://www.amnh.org/research/center-for-biodiversity-conservation/resources-and-publications/lessons-in-conservation/volume-11 (accessed May 14, 2021).

Betley, E., Sterling, E. J., Akabas, S., Paxton, A., and Frost, L. (2021b). Introduction to systems and systems thinking. Lessons in Conservation 11, 9–25. Available online at: https://www.amnh.org/research/center-for-biodiversity-conservation/resources-and-publications/lessons-in-conservation/volume-11 (accessed May 14, 2021).

Cadieux, K. V., and Slocum, R. (2015). What does it mean to do food justice? J. Polit. Ecol. 22, 1–26. doi: 10.2458/v22i1.21076

Carver, C. S., and Scheier, M. F. (2001). On the Self-Regulation of Behavior. New Yrk, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Charusheela, S. (2009). Social analysis and the capabilities approach: a limit to Martha Nussbaum's universalist ethics. Cambridge J. Econ. 33, 1135–1152. doi: 10.1093/cje/ben027

Clegg, D., Dring, C., and Valley, W. (2021). Preparing for affective pedagogy of injustice in STEM classrooms. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. this issue.

Cordova-Cobo, D., and Cobo, V. III (2020). Anti-racist, trauma-informed teaching. The Public Good. Available online at: https://sites.google.com/tc.columbia.edu/traumainformedteaching (accessed February 18, 2021).

Dalton, P. S., Gonzalez Jimenez, V. H., and Noussair, C. N. (2017). Exposure to poverty and productivity. PLoS ONE 12, e0170231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170231

de los Reyes, E., Smith, H., Yazzie, T., Hussein, Y., and Tuitt, F. (2001). A Democratic Pedagogy for a Democratic Society: Education for Social and Political Change. Unpublished manuscript, Harvard Graduate School of Education.

de Sousa Santos, B. (2014). “A critique of lazy reason: against the waste of experience and toward the sociology of absences and the sociology of emergences,” in Epistemologies of the South, 1st Edn., ed B. de Sousa Santos (New York, NY: Routledge), 164–187.

Dee, T., and Gershenson, S. (2017). Unconscious Bias in the Classroom: Evidence and Opportunities. Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis.

Downs, S., Ahmed, S., Fanzo, J., and Herforth, A. (2020). Food environment typology: Advancing an expanded definition, framework, and methodological approach for improved characterization of wild, cultivated, and built food environments toward sustainable diets. Foods 9, 532. doi: 10.3390/foods9040532

Ebel, R., Ahmed, S., Valley, W., Jordan, N., Grossman, J., Byker Shanks, C., et al. (2020). Co-design of adaptable learning outcomes for sustainable food systems undergraduate education. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 29, 170. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2020.568743

Fawaz, R. (2016). How to make a queer scene, or notes toward a practice of affective curation. Femin. Stud. 42, 757–768. doi: 10.15767/feministstudies.42.3.0757

Giordano, S. (2017). Feminists increasing public understandings of science: a feminist approach to developing critical science literacy skills. Front. J. Women Stud. 38, 100. doi: 10.5250/fronjwomestud.38.1.0100

Global Nutrition Report (2020). Action on equity to end malnutrition. Development Initiatives. Available online at: https://globalnutritionreport.org/reports/2020-global-nutrition-report/ (accessed June 29, 2021).

Goodchild, M. (2021). Relational systems thinking: that's how change is going to come, from our earth mother. J. Aware. Based Syst/ Change 1, 75–103. doi: 10.47061/jabsc.v1i1.577

HLPE (2017). Nutrition and Food Systems. A report by the high level panel of experts on food security and nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security, Rome. Available online at: http://www.fao.org/3/i7846e/i7846e.pdf

Holt-Giménez, E., and Harper, B. (2016). Dismantling racism in the food system: food—systems—racism: from mistreatment to transformation. Food First. Available online at: https://foodfirst.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/DR1Final.pdf (accessed June 30, 2021).

Ingram, J., Ajates Gonzalez, R., Arnall, A., Blake, L., Borrelli, R., Collier, R., et al. (2020). A future workforce of food-system analysts. Nature Food 1, 9–10. doi: 10.1038/s43016-019-0003-3

Iowa State University Extension Outreach (2021). Resources: Inequities in the Food System. Available online at: https://www.extension.iastate.edu/ffed/resources-2/food-systems-equity/ (accessed June 30, 2021).

Isen, A. M., Daubman, K. A., and Nowicki, G. P. (1987). Positive affect facilitates creative problem solving. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 52:1122.

Jordan, N., Grossman, J., Lawrence, P., Harmon, A., Dyer, W., Maxwell, B., et al. (2014). New curricula for undergraduate food-systems education: a sustainable agriculture education perspective. NACTA J. 58, 302–310. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/nactajournal.58.4.302

Kubala, J. (2020). Of trauma and triggers: pedagogy and affective circulations in feminist classrooms. Femin. Format. 32, 183–206. doi: 10.1353/ff.2020.0030

Leonard, T. (2019). How Meghan's favourite avocado snack - beloved of all millennials - is fuelling human rights abuses, drought and murder. The Daily Mail.

McArthur, J. (2010). Achieving social justice within and through higher education: the challenge for critical pedagogy. Teach. High. Educ. 15, 493–504. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2010.491906

Menakem, R. (2017). My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and Mending our Hearts and Bodies. Las Vegas, NV: Central Recovery Press.

Mignolo, W. D. (2011). The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options. Duke University Press.

Mondragón, M., and López-Portillo, V. (2020). Will Mexico's growing avocado industry harm its forests? World Resource Institute Commentary.

Mountz, A., Moore, E. B., and Brown, L. (2008). Participatory action research as pedagogy: boundaries in Syracuse. ACME Int. J. Crit. Geograph. 7, 214–238. Available online at: https://acme-journal.org/index.php/acme/article/view/804

Murray, C. J., Aravkin, A. Y., Zheng, P., Abbafati, C., Abbas, K. M., Abbasi-Kangevari, M., et al. (2020). Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 396, 1223–1249. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2

Nahl, D. (2004). Measuring the affective information environment of web searchers. Proc. Amer. Soc. Inform. Sci. Technol. 41, 191–197. doi: 10.1002/meet.1450410122

Nussbaum, M. C. (1993). social justice and universalism: in defense of an aristotelian account of human functioning. Mod. Philol. 90, S46–S73.

Paxton, A., Frost, L., Betley, E., Akabas, S., and Sterling, E. J. (2021). Systems thinking collection: stakeholder analysis exercise. Less. Conserv. 11, 33–38. Available online at: https://www.amnh.org/research/center-for-biodiversity-conservation/resources-and-publications/lessons-in-conservation/volume-11

Quinlan, K. (2016). How emotion matters in four key relationships in teaching and learning in higher education. College Teach. 64, 101–111. doi: 10.1080/87567555.2015.1088818

Race Forward: The Center for Racial Justice Innovation (2014). Moving the Race Conversation Forward, Parts 1–2. Available online at: https://www.raceforward.org/research/reports/moving-race-conversation-forward (accessed June 28, 2021).

Scherer, K. R. (2005). What are emotions? And how can they be measured? Soc. Sci. Inform. 44, 693–727. doi: 10.1177/0539018405058216

Slocum, R. (2007). Whiteness, space and alternative food practice. Geoforum 38:520–533. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2006.10.006

Smith, J. (2002). Learning styles: fashion fad or lever for change? The application of learning style theory to inclusive curriculum delivery. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 39, 63–70, doi: 10.1080/13558000110102913

Stanley, C., and Haynes, C. (2019). What have we learned from critical qualitative inquiry about race equity and social justice? An interview with pioneering scholar Yvonna Lincoln. Qual. Rep. 24, 1915–1929. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2019.3582

Stein, S. (2019). Navigating different theories of change for higher education in volatile times. Educ. Stud. 55, 667–688. doi: 10.1080/00131946.2019.1666717

Stein, S., Ahenakew, C., Jimmy, E., Andreotti, V., Valley, W., Amsler, S., et al. (2021). “Developing stamina for decolonizing higher education: a workbook for non-indigenous people,” in Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures Collective. Available online at: https://decolonialfuturesnet.files.wordpress.com/2021/03/decolonizing-he-workbook-draft-feb2021.pdf

Stein, S., Andreotti, V., Suša, R., Amsler, S., Hunt, D., Ahenakew, C., et al. (2020). Gesturing towards decolonial futures: reflections on our learnings thus far. Nord. J. Compar. Int. Educ. 4, 43–65. doi: 10.7577/njcie.3518

Stein, S., Hunt, D., Suša, R., and de Oliveira Andreotti, V. (2017). The educational challenge of unraveling the fantasies of ontological security. Diasp. Indig. Minor. Educ. 11, 69–79. doi: 10.1080/15595692.2017.1291501

Sullivan, D. (2014). From food desert to food mirage: race, social class and food shopping in a gentrifying neighborhood. Adv. Appl. Sociol. 4, 30–35. doi: 10.4236/aasoci.2014.41006

Tate, S. A., and Page, D. (2018). Whiteliness and institutional racism: hiding behind (un)conscious bias. Ethics Educ. 13, 141–155. doi: 10.1080/17449642.2018.1428718

Thomas, M. S., Crosby, S., and Vanderhaar, J. (2019). Trauma-informed practices in schools across two decades: an interdisciplinary review of research. Rev. Res. Educ. 43, 422–452. doi: 10.3102/0091732X18821123

Valley, W., Anderson, M., Tichenor Blackstone, N., Sterling, E., Betley, E., Akabas, S., et al. (2020). Towards an equity competency model for sustainable food systems education programs. Elementa Sci. Anthrop. 8:33. doi: 10.1525/elementa.428

Valley, W., Wittman, H., Jordan, N., Ahmed, S., and Galt, R. (2018). An emerging signature pedagogy for sustainable food systems education. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 41, 487–504. doi: 10.1017/S1742170517000199

Wahl, R. (2021). Reasoning one's way to justice? Rationality and understanding in political dialogue. Philosophy of Education Society Conference (San Jose, CA).

Whittaker, J. A., and Montgomery, B. L. (2012). Cultivating diversity and competency in STEM: Challenges and remedies for removing virtual barriers to constructing diverse higher education communities of success. J. Undergrad. Neurosci. Educ. 11, A44–A51.

Willett, W., Rockström, J., Loken, B., Springmann, M., Lang, T., Vermeulen, S., et al. (2019). Food in the anthropocene: the EAT–lancet commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 393, 447–492. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4

Keywords: food systems pedagogy, systems thinking, equity, critical reflection, sustainable food systems education, affect

Citation: Sterling EJ, Betley E, Ahmed S, Akabas S, Clegg DJ, Downs S, Izumi B, Koch P, Kross SM, Spiller K, Teron L and Valley W (2021) Centering Equity in Sustainable Food Systems Education. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5:737434. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2021.737434

Received: 07 July 2021; Accepted: 24 September 2021;

Published: 28 October 2021.

Edited by:

Emily Huddart Kennedy, University of British Columbia, CanadaReviewed by:

Eric Holt-Gimenez, Retired, Oakland, CA, United StatesBen M. McKay, University of Calgary, Canada

Copyright © 2021 Sterling, Betley, Ahmed, Akabas, Clegg, Downs, Izumi, Koch, Kross, Spiller, Teron and Valley. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eleanor J. Sterling, c3RlcmxpbmdAYW1uaC5vcmc=

†These authors share first authorship

Eleanor J. Sterling

Eleanor J. Sterling Erin Betley

Erin Betley Selena Ahmed

Selena Ahmed Sharon Akabas3

Sharon Akabas3 Daniel J. Clegg

Daniel J. Clegg Shauna Downs

Shauna Downs Betty Izumi

Betty Izumi Pamela Koch

Pamela Koch Sara M. Kross

Sara M. Kross Karen Spiller

Karen Spiller Lemir Teron

Lemir Teron Will Valley

Will Valley