- Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States

Antibiotic stewardship programs (ASPs) are meant to promote appropriate use of antibiotics and to help maintain the effectiveness of antibiotics. For the United States (US) animal agriculture industry, multiple resources exist to guide antibiotic stewardship practices. Animal management certification programs can promote on-farm compliance with antibiotic stewardship through the incentive of achieving certification. The goal of this project was to determine whether the stewardship-related requirements of US-based certification programs align with identified core components of antibiotic stewardship in food animal agriculture using the Antibiotic Stewardship Assessment Tool (ASAT). We applied the ASAT to publicly available information from four different US animal agriculture certification programs that incorporate some level of antibiotic stewardship. In part due to varying scopes, the programs demonstrated a great deal of variability in meeting the metrics of the ASAT, with one program meeting all the required metrics and the other three only meeting the metrics to varying degrees (ranging from 3 to 67%). We identified several areas as opportunities for enhancing and promoting ASP implementation on farms. The area with the most opportunity for improvement is evaluation. Evaluation can help ensure effective outcomes of stewardship practices and ensure accountability for following recommended antibiotic stewardship guidelines. While evaluation currently may fall outside the scope of some certification programs, the incorporation of more specific antibiotic stewardship evaluation details within certification program content could serve as an important mechanism for promoting voluntary on-farm compliance with antibiotic stewardship guidelines.

Introduction

Antibiotic resistance is a critical global public health threat that requires enduring action from those who use and rely on antibiotics to treat infections (World Health Organization, 2015; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2016; OIE World Organisation for Animal Health, 2016; Federal Task Force on Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria, 2020). One approach to combating antibiotic resistance is through implementation of antibiotic stewardship programs (ASPs), yet the definition of stewardship and what actions determine effective stewardship can vary depending on the setting. Overall, ASPs are meant to promote appropriate use of antibiotics and to help maintain the effectiveness of antibiotics. Comprehensive ASPs (which usually incorporate some form of leadership commitment, actionable policies and interventions, accountability through tracking and review, drug expertise, and education) have been implemented and shown to be effective in human medical settings for many years (Davey et al., 2017; Nathwani et al., 2019; Centers for Disease Control Prevention, 2020). Yet similar documentation of comprehensive ASPs in veterinary medical settings has been lacking in the United States (US) even though resources to guide the development of ASPs have become increasingly available (Weese et al., 2013; Page et al., 2014; Guardabassi and Prescott, 2015; Guardabassi et al., 2018; Lloyd and Page, 2018). This has started to change, especially in larger veterinary hospital settings such as teaching hospitals (Redding et al., 2020b; Feyes et al., 2021; University of Minnesota, 2021); however, information remains limited regarding comprehensive ASP implementation on-farm in US animal agriculture settings.

In animal agriculture, one component of antibiotic stewardship that frequently receives attention is decreasing antibiotic drug use; however, decreased antibiotic drug use alone does not equate to good stewardship. Antibiotics can still be used inappropriately and if antibiotics are withheld completely, animal health and welfare can suffer, which can often result in negative economic and social consequences (Bengtsson and Greko, 2014; Karavolias et al., 2018; Singer et al., 2019). In 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) implemented significant policy shifts to improve responsible use of antimicrobial drugs (including antibiotics) in animal agriculture (U. S. Food and Drug Administration, 2012, 2013). These changes included eliminating the use of medically important antibiotics for growth promotion in food animals and requiring veterinary oversight for the use of medically important antibiotics in animal feed or water. The anticipation of these policies, which were years in development, and their full implementation have contributed to an overall decrease in antibiotic use in at least the US poultry industry (U. S. Poultry and Egg Association, 2019; Singer et al., 2020a,b), while the effects on overall antibiotic use in other industries for major food animal species in the US (i.e., cattle, swine) are currently less certain, in part due to variable antibiotic use measures and data collection within these industries (Davies and Singer, 2020; Hope et al., 2020; Schrag et al., 2020). The FDA has developed additional guidance to ensure veterinary oversight for all medically important antimicrobial drugs approved for use in animals (U. S. Food and Drug Administration, 2021). Other high-income countries have implemented similar, and in many cases more strict or comprehensive, approaches to antibiotic use in animals (Australian Government, 2017; Government of Canada, 2017; More, 2020). Still, effective antibiotic stewardship on-farm involves more than simply decreasing overall antibiotic use.

In addition to these federal initiatives, multiple US professional veterinary organizations and state agricultural programs have developed antibiotic stewardship guidelines for food animal veterinarians and animal agriculture producers (American Association of Bovine Practitioners, 2017; American Association of Avian Pathologists, 2018; American Association of Swine Veterinarians, 2020; California Department of Food and Agriculture, 2021; Minnesota Department of Agriculture, 2021), although the implementation of these guidelines has generally been left to individual veterinarians and producers. Existing guidelines overlap in content and typically endorse or incorporate the core principles of antimicrobial stewardship as outlined by the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) (American Veterinary Medical Association, 2021). Few reports, however, have examined the implementation of comprehensive ASPs on-farm to ensure effective stewardship and literature reviews indicate that more evidence-based data are needed to inform antibiotic stewardship practices (Sargeant et al., 2019). The US Department of Agriculture's (USDA's) National Animal Health Monitoring System (NAHMS) published two reports in 2019 on their first “in-depth look” at antimicrobial drug use and stewardship practices on US swine sites and cattle feedlots the year before the FDA policy changes went into effect (i.e., 2016) (U. S. Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, 2019, 2020). These reports will serve as a benchmark for comparison with antibiotic use and stewardship practices in future studies. The impact of these policies, guidelines, and collection of antibiotic use data require continued study, standardization, and consideration when implementing comprehensive ASPs in agricultural settings.

While further study and data collection are necessary to understand more fully antibiotic use and antibiotic stewardship practices in US animal agriculture, to combat antibiotic resistance veterinarians and animal agriculture industries must continue to implement what are currently deemed best practices regarding antibiotic stewardship. Various quality assurance and process-verifying programs (including certification programs) in the US help veterinarians and producers accomplish this by incorporating aspects of antibiotic stewardship into their program content. While these programs range in purpose and scope, programs that involve certification can promote best animal-production practices on farms by providing training and education on important animal health issues and by ensuring that farms meet a set of standards through audits, self-assessments, or other verification methods. Some programs focus their efforts on educating and training their stakeholders and also provide tools to assist with implementation of program content. Others provide producers a way to build consumer confidence and market their products by verifying the implementation of specific agricultural processes. Similar programs have been implemented in other countries with success and some criticism—citing the need for critical review of such programs (More et al., 2017; More, 2020).

We conducted the project described here to evaluate existing certifying-level programs in the US that incorporate antibiotic stewardship components into their program requirements. To do so, we used an assessment tool recently developed by The Pew Charitable Trusts that considers actionable metrics to determine if the programs' requirements for farm or producer certification align with core principles of antibiotic stewardship in animal agriculture and to what degree. With the goal of advancing current antibiotic stewardship efforts, we have identified common areas of strength in existing programs' antibiotic stewardship requirements and potential areas for improvement to promote on-farm ASP implementation.

Methods

The Antibiotic Stewardship Assessment Tool

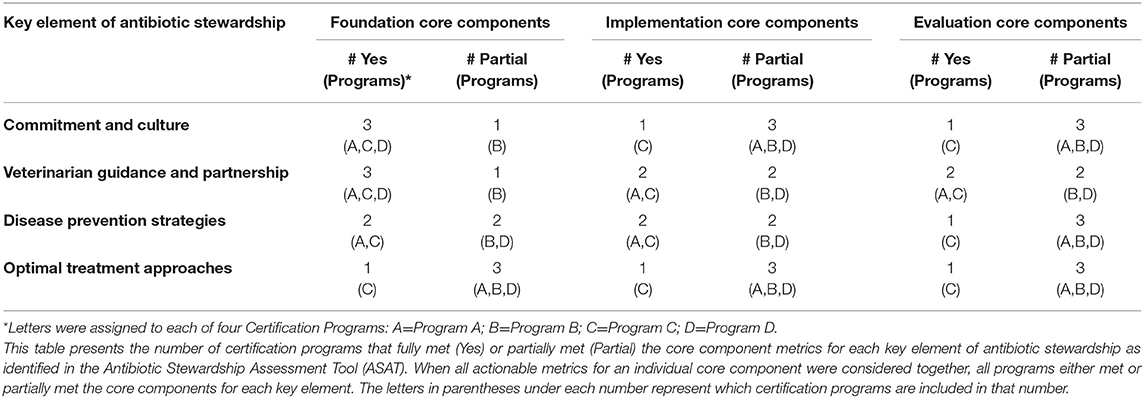

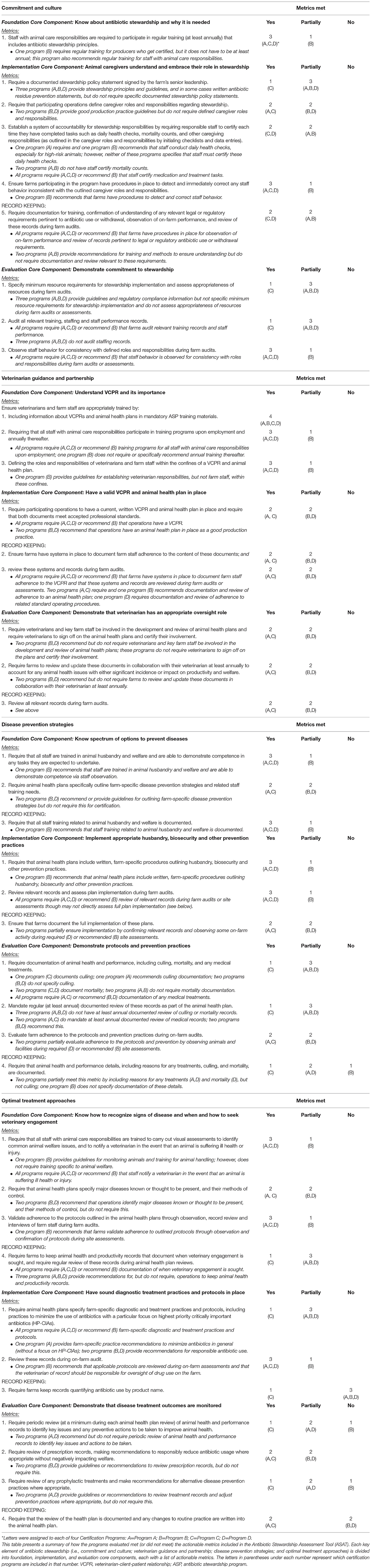

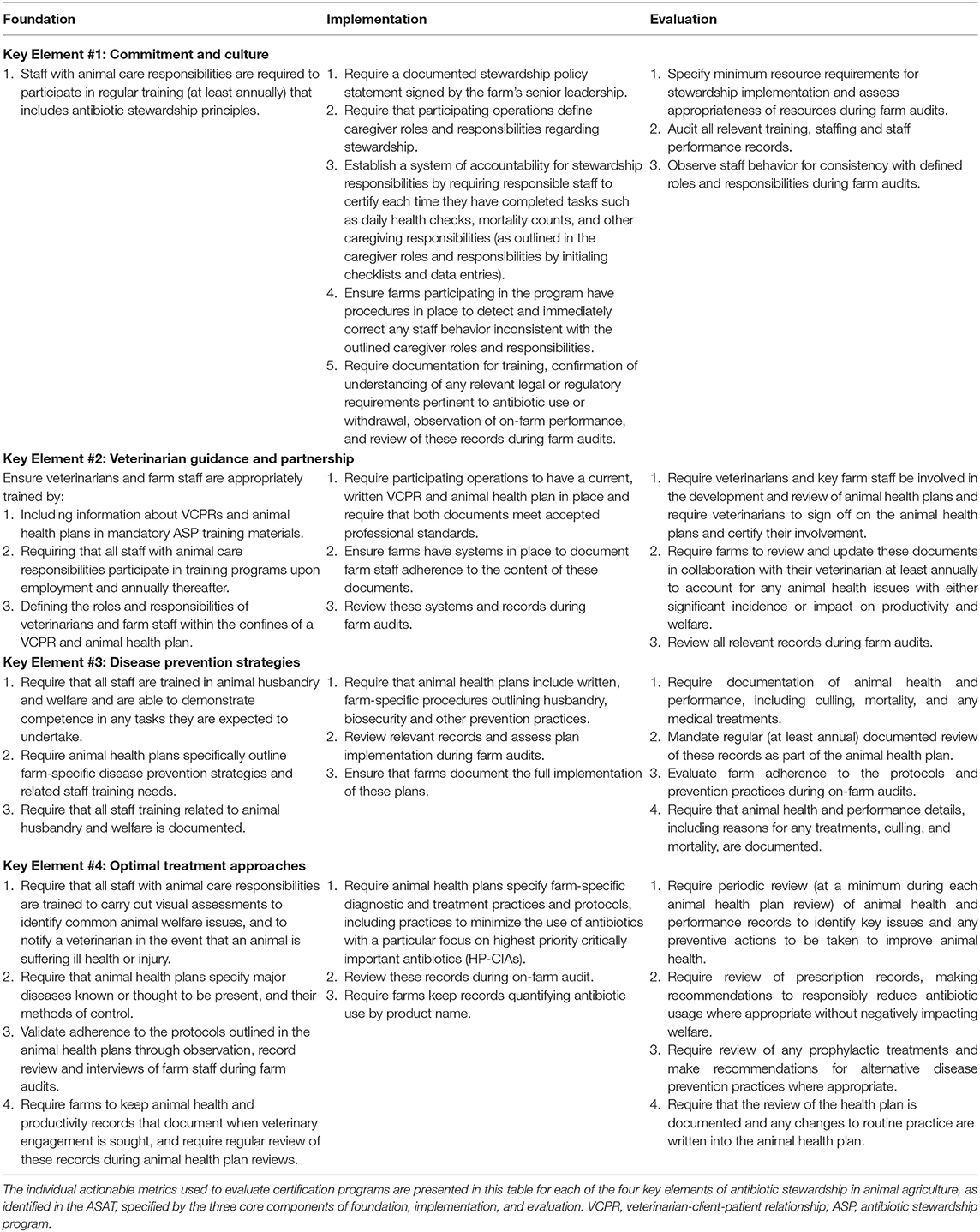

The Antibiotic Stewardship Assessment Tool (ASAT) (see supplement for full version) was developed for use by food-systems stakeholders within the major animal agriculture industries in the US (i.e., cattle, swine, poultry). The stated objective of the tool, which is intended to be used to evaluate qualified animal management certification programs (definition below), is to “facilitate the transparent and regular assessment of progress in antibiotic stewardship throughout the supply chain in US animal agriculture.” The ASAT includes four key elements of antibiotic stewardship: (1) commitment and culture, (2) veterinarian guidance and partnership, (3) disease prevention strategies, and (4) optimal treatment approaches. Each key element is further divided into three core components: foundation, implementation, and evaluation. The foundation core component is focused on knowledge, training, or understanding; the implementation core component is focused on having policies, procedures, and plans in place that promote meaningful stewardship; and the evaluation component is focused on validating stewardship practices, such as observing staff, conducting audits or document reviews, and assessing adherence to stewardship practices. Metrics are specified for each of the three core components under the four key elements; the metrics identify actionable steps that can be taken at the farm-level to effectively achieve the respective core component and thus can be used to evaluate the implementation of meaningful antibiotic stewardship in animal agriculture across the four key elements (Table 1). The key elements and core components of the ASAT were developed by a group of major food companies, retailers, livestock producers, and trade and professional associations in dialog with the Farm Foundation and The Pew Charitable Trusts and summarized in a Framework for Antibiotic Stewardship in Food Animal Production document (The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2018a,b). Construction of the ASAT was modeled after the Global Food Safety Initiative's (GFSI's) benchmarking tools and Benchmarking Requirements (Global Food Safety Initiative, 2021).

Table 1. Assessment metrics in the Antibiotic Stewardship Assessment Tool (ASAT) for each key element by the three core components (Foundation, Implementation, and Evaluation).

Certification Programs

The ASAT defines an animal management certification program as “any program that incorporates an evaluation of antibiotic stewardship as a component of the program's certification requirements and meets the following criteria: (1) the program is a certifying program that directly evaluates the workforce training and animal production practices of major food-producing species (i.e., cattle, swine, poultry); (2) the program criteria are freely available and accessible to the public (e.g., are available on the program website [or upon request]); and (3) the program is open to participation by all producers that meet the program requirements (company-specific and proprietary policies are excluded from evaluation).” For this study, efforts were aimed at identifying certification programs located in the US.

We conducted online searches between November and December 2020 to identify certification programs in the US that met the selection criteria listed in the ASAT. We used key terms, and different combinations of key terms, that could return certification programs (e.g., antibiotic stewardship certification agriculture, agriculture antimicrobial stewardship program, antimicrobial stewardship poultry, etc.). We looked at the previews to the sites that were returned from each search for the first two pages of search results, pursuing sites that appeared to reference programs that could meet the inclusion criteria. In addition to these key-term searches, we reviewed company websites for 10 of the major food-animal agriculture companies in the US (as identified in the National Provisioner's Top 100 Processors Report and Dairy Foods' annual Dairy 100) for mention of potential certification programs that could meet the inclusion criteria; these companies represented the beef, dairy, pork, and poultry industries.

To ensure we had identified all applicable programs, we also reached out to at least one subject matter expert (SME) from each of the following: professional or trade organizations for animal agriculture industry (at least one from each primary industry sector), veterinary professional organizations, and academia. Criteria for selection of SMEs were defined as follows. Professional or trade organizations must: (1) be national in scope to avoid possible regional bias; (2) be broadly representative of the industry sector, to include representing multiple producers; (3) have demonstrated interest in farm-related policies or standards; and (4) should not be an organization already identified as a program to be evaluated for this project. Veterinary organizations must: (1) be national in scope to avoid possible regional bias, (2) be broadly representative of veterinarians involved with food animal agriculture and/or public health, and (3) have demonstrated interest in antibiotic resistance issues. Academia representatives must have: (1) expertise in antibiotic resistance/stewardship content, (2) experience/expertise working with the food animal industry, and (3) be associated with a reputable university.

Following these searches and discussions, we identified the following four US certification programs for inclusion in this study (listed in alphabetical order): Beef Quality Assurance (BQA), the National Dairy Farmers Assuring Responsible Management (FARM™) Program, One Health Certified™ (which at the time of this study only had chicken and turkey standards), and Pork Quality Assurance® Plus (PQA® Plus). While the scopes of these programs vary significantly, they all include specific components or tools that can be used to evaluate workforce training and animal production practices, which are publicly available and open to all qualifying producers. We identified multiple additional programs, agencies, and companies that discuss antibiotic stewardship in animal agriculture; however, none met the criteria for a certification program as defined in the ASAT. One of these was a certifying-level program but it did not meet the ASAT criteria of directly evaluating workforce training and animal production practices.

Data Collection and Application of the Tool

For the four identified certification programs, we reviewed publicly available information from the program websites related to the antibiotic stewardship components identified in the ASAT. Materials included program manuals, field guides, audit checklists, assessment or evaluation guides, drug residue reference manuals, guides for responsible antibiotic use, templates, and text on website landing pages (e.g., FAQ pages). We then applied the ASAT to assess each program based on the publicly available information.

For each certification program, using Excel spreadsheets (Microsoft Excel, RRID:SCR_016137), we recorded if the requirements for each metric were: (1) fully met, (2) partially met (i.e., some, but not all, of the requirements were met), or (3) not met (i.e., none of the requirements were met). We established decision-making rules to ensure consistency within (and across) programs for how metrics could be met. For example, if a metric “required” a certain practice or activity to fully meet the metric, we defined “required” to include those practices or activities necessary to achieve certification or program site status. If a practice or activity was only recommended (e.g., through guidelines, principles, good production practices, or best practices) but not required for certification or program site status, we considered that metric to be partially met rather than fully met. For each metric, we also recorded notes explaining how the publicly available information provided evidence that the program fully met, partially met, or did not meet the listed requirements.

Verification of Information

Through program websites, we identified either an individual point of contact email or a generic “contact us” option for each certification program. We sent an initial electronic inquiry to all programs requesting a discussion to verify information we had gathered about the program and to ensure the validity of any assumptions made and resultant findings regarding how the metrics were classified. Personnel from each of the four programs responded to our inquiry and participated in a conference call discussion specific to their program. During the calls, we also inquired whether the information that we could not find on the program website was available elsewhere and could be shared upon request. Documents “available upon request” were considered to be publicly available. During each call, the program representative(s) also agreed to review and validate the information we gathered regarding their program.

Following the calls, we sent a copy of the completed spreadsheet to the representatives from each program for their review. All program representatives agreed with the information gathered and some provided additional information that resulted in minor changes to the completed spreadsheets.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted by summarizing and comparing the information gathered in Excel for each certification program. We assigned a letter (A, B, C, or D) to each program to present results. In addition to individual metrics outlined in Table 1, for each program we assessed the four key elements of stewardship (i.e., commitment and culture, veterinary guidance and partnership, disease prevention strategies, and optimal treatment approaches) by the separate core components of foundation, implementation, and evaluation. We then summarized results across the four programs.

When considering the key elements by the separate core components, if all the individual metrics under a foundation, implementation, or evaluation core component section were met, this was recorded as “yes” for that specific key element-core component section. If any of the individual metrics under a core component section were not met but at least one or more of the other metrics in that section were met or partially met, this was recorded as “partially” for that key element-core component section. Although this did not occur in our evaluation, if all the individual metrics under a core component section were not met this would have been recorded as “no” for that key element-core component section.

Results

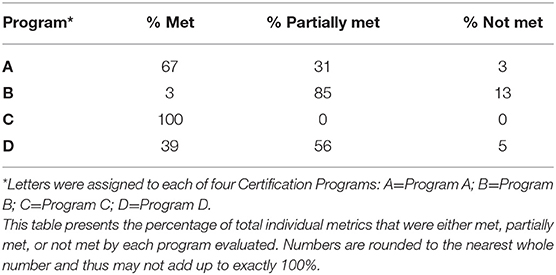

All four programs either fully met or partially met the core components for each of the four key elements of stewardship (Table 2), although individual metrics under the core components were not always met (Table 3). One program met all individual metrics listed in the ASAT and the other three programs met 3, 39, and 67% of the total metrics (Table 4). Only one metric was fully met by all programs; this foundation metric involved training under the key element of veterinarian guidance and partnership. No single core component for any key element was met by all four programs nor was there any single key element that had more than one core component met by a majority of programs. For two key elements (commitment and culture and veterinarian guidance and partnership), three of the programs met the foundation core components. In general, programs were more likely to meet the foundation core component metrics, which are focused on providing information and training, whereas programs were more variable in meeting the implementation core component metrics, and less likely to meet the evaluation core component metrics. Only one out of 10 metrics specifically labeled as record keeping in the ASAT was met by a majority of programs.

Element 1: Commitment and Culture

Of nine individual metrics under commitment and culture, three were met by the majority of programs: one metric under each core component. Three of four programs met the single metric under the foundation core component, which focused on requiring regular (i.e., annual) training on antibiotic stewardship. The program that did not meet this metric required training for producers who obtain certification, but the training is not required annually. Out of the five implementation core component metrics, the one that was met by three of the four programs was ensuring procedures are in place to detect and correct any staff behavior inconsistent with caregiver roles and responsibilities. Only one or two programs met the following four metrics: (1) requiring a documented stewardship policy statement signed by senior leadership, (2) requiring that participating operations define caregiver roles and responsibilities regarding stewardship, (3) establishing a system of accountability for stewardship responsibilities by requiring staff to certify certain activities, and (4) requiring documentation for training. One of the three metrics under the evaluation core component was met by three of the four programs: observing staff behavior for consistency with defined roles and responsibilities during farm audits. The other two (one on specifying minimum resource requirements and one on auditing all relevant training, staffing, and staff performance records) were each met by only one program.

Element 2: Veterinarian Guidance and Partnership

While three out of nine metrics under veterinarian guidance and partnership were met by the majority of programs (the same ratio as the commitment and culture key element), all of these metrics were under the foundation core component and one of these metrics was met by all programs [ensuring appropriate training by including information about veterinarian-client-patient relationships (VCPRs) and animal health plans in ASP training materials]. The other two metrics under the foundation core component involved requiring all animal-care staff to participate in training on the VCPR upon employment and annually, and defining roles and responsibilities for veterinarians and farm staff within the confines of the VCPR and animal health plan. For the three metrics under the implementation core component and the three metrics under the evaluation core component, the same two programs fully met all of the metrics. The three metrics under implementation involved: (1) requiring that current written VCPR and animal health plans are in place, (2) ensuring that farms have systems in place to document adherence to these documents, and (3) reviewing these systems and records during farm audits. For the metrics under the evaluation component, the first requires that veterinarians and key farm staff be involved in developing the plans and signing off on them, the second requires farms to review and update the documents annually to account for any animal health issues, and the third requires review of all relevant records during farm audits.

Element 3: Disease Prevention Strategies

Four of the 10 metrics under disease and prevention strategies were met by a majority of programs. Two of the three foundation metrics were met by three programs: (1) requiring that all staff are trained in animal husbandry and welfare and are able to demonstrate competence in tasks they are expected to undertake, and (2) requiring that all staff training related to animal husbandry and welfare is documented. The program that did not fully meet these foundation metrics recommended, but did not require, this training and documentation for certification or site status purposes. The remaining foundation metric requires that animal health plans specifically outline farm-specific disease prevention strategies and related staff training needs. This was fully met by two programs and recommended by the other two programs. For the implementation core component, two of the three metrics were met by a majority of programs: one requiring that animal health plans include written, farm-specific procedures outlining husbandry, biosecurity and other prevention practices, and one reviewing relevant records and assessing plan implementation during farm audits. The third implementation metric ensuring that farms document the full implementation of these plans was only met by two of the four programs. Again, the programs that partially met these metrics recommended, but did not require, these actions for certification or site status purposes. None of the four metrics under the evaluation core component were met by more than two programs. These metrics include: (1) requiring documentation of animal health and performance, including culling, mortality, and any medical treatments, (2) mandating at least annual documented review of these records, (3) evaluating farm adherence to the protocols and prevention practices during on-farm audits, and (4) requiring that animal health and performance details are documented including reasons for any treatments, culling, and mortality.

Element 4: Optimal Treatment Approaches

Of 11 individual metrics under optimal treatment approaches, three were met by a majority of programs. Two of these metrics were under the foundation core component: (1) requiring all animal-care staff to be trained to carry out visual assessments to identify common animal welfare issues and to notify a veterinarian in the event that an animal is suffering ill health or injury; and (2) validating adherence to animal health plan protocols through observation, record review and interviews of farm staff. Two programs met the foundation metric requiring that animal health plans specify major diseases known or thought to be present, and methods of control. And only one program fully met the record-keeping metric, which requires farms to keep animal health and productivity records that document veterinary engagement and requiring regular review of these records. Similar to other key element areas, the programs that partially met these metrics recommended, but did not require, these actions. One of the three metrics under the implementation core component was met by a majority of programs (reviewing records relevant to farm-specific diagnostic and treatment practices and protocols); the other two were only met by one program. The first requires that animal health plans specify farm-specific diagnostic and treatment practices and protocols, including practices to minimize the use of antibiotics with a focus on highest priority critically important antibiotics, with most programs recommending this and not requiring it. The second was the only metric in this study that the majority of programs did not meet and requires that farms keep records quantifying antibiotic use by product name. None of the four metrics under the evaluation component were met by more than two programs; these included: (1) requiring periodic review of animal health and performance records to identify key issues and any preventive actions to improve animal health; (2) requiring review of prescription records, making recommendations to responsibly reduce antibiotic usage where appropriate; (3) requiring review of any prophylactic treatments and making recommendations for appropriate alternative disease prevention practices; and (4) requiring that the review is documented and any changes to routine practice are written into the animal health plan.

Discussion

Certification programs can promote best animal-management practices on farms by providing training and education on important animal health issues and by ensuring that farms or individual producers meet a set of standards to achieve certification. These programs, therefore, can serve as an important mechanism for promoting voluntary on-farm compliance with existing antibiotic stewardship guidelines through the incentive of achieving certification. The goal of this project was to determine whether the antibiotic stewardship-related requirements of identified US-based certification programs align with recognized core components of antibiotic stewardship in food animal agriculture. We also wanted to determine if important gaps exist in implementing antibiotic stewardship practices that could be addressed by recommending improvements to farm certification programs. Furthermore, rather than surveying individual farms, this study was designed to assess US animal-management certification programs, which provide certification to thousands of farms and individual producers. At the time of this study, approximately 8% of the broiler production, 85% of the beef grown, 85% of the pig population, and 99% of the milk supply in the US came from farms or producers certified by the programs included in this assessment (Beef Checkoff, 2020; Samuel et al., 2020; U. S. Department of Agriculture and Agricultural Marketing Service, 2020; National Dairy FARM Program, 2021; U. S. Poultry and Egg Association, 2021). By targeting these certification programs, we were able to generate a reasonable picture of how well antibiotic stewardship practices are being addressed on certified farms, or farms with certified producers, across different food animal industries.

The major findings from this study are as follows. First, the programs demonstrated a great deal of variability in meeting the metrics of the ASAT, which is in part due to the varying scopes of the programs with each having different audiences and intentions. Second, only one metric (under the veterinarian guidance and partnership foundation core component) was fully met by all four of the programs, indicating that efforts to strengthen these programs toward meeting more of the metrics would be of value in improving antibiotic stewardship on US farms. Third, most of the metrics (8 out of 11) for the foundation core component were fully met by a majority of the programs, across all key elements, suggesting that these certification programs play an important role in ensuring that farm staff know what stewardship practices are needed and why, which is a critical first step in voluntary compliance with ASP recommendations. Improving awareness and knowledge alone, however, does not necessarily indicate that these practices are actually being implemented on-farm. Fourth, the core component with the least amount of focus by these programs is the evaluation component. This again is in part due to the varying scopes of the certification programs. For example, some programs are mainly educational in scope and do not include evaluation as a main component of their requirements or activities, or do not include on-farm evaluation at all as part of individual producer certification requirements. Since the evaluation component focuses on documentation and accountability, efforts to strengthen this component across all key elements could improve the effectiveness of these certification programs in promoting antibiotic stewardship at the farm level.

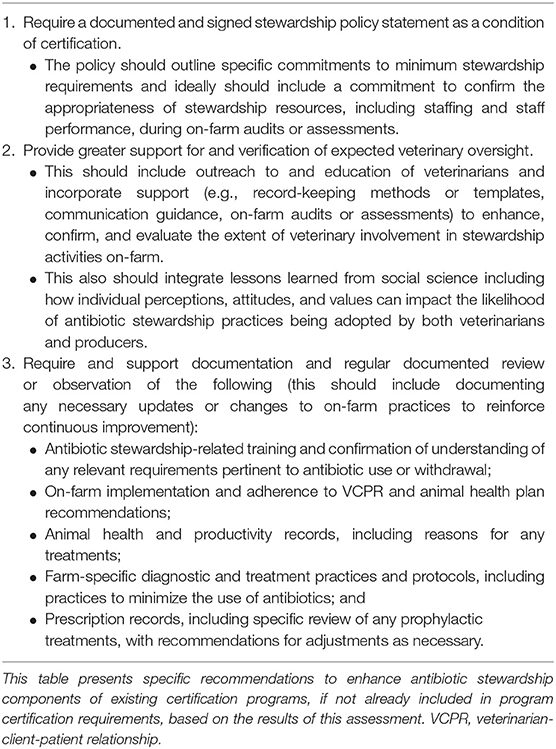

We have highlighted specific recommendations (Table 5), taken from the more granular results of our evaluation (shown in Table 3), that could enhance existing certification programs by focusing resources or improving practices toward several actionable metrics. These recommendations mainly involve strengthening on-farm implementation and accountability. For example, even though not all certification programs require on-farm audits or assessments as part of their certification or site status requirements, all programs could require a documented and signed stewardship policy statement as a condition of certification. Such a policy should help farms or individual producers outline specific commitments to minimum stewardship requirements and ideally should include a commitment to confirm the appropriateness of these resources, including staffing and staff performance, during on-farm audits or assessments. This could involve partnering with existing third–party auditing programs that use the certification program guidelines as the basis for their auditing criteria.

Another opportunity to improve implementation of certification program guidelines is to provide greater support for and verification of expected veterinary oversight. Two of the most critical aspects for implementing antibiotic stewardship in animal agriculture settings are the VCPR and the animal health plan. Several metrics involving the veterinarian, and particularly the animal health plan, however, were only partially met or were not met in this assessment. Although all programs we evaluated either require or recommend a VCPR, confirmation and evaluation regarding the extent of veterinary involvement in ASP activities on-farm was not always required. The reliance on veterinarians is an important area of opportunity as veterinarians may not be aware of all the stewardship-related expectations of them or they may lack the resources to effectively implement these expectations. While VCPRs are likely to have increased in recent years given new FDA policies, the USDA's 2017 Antimicrobial Use and Stewardship surveys indicate that, at least on swine sites and cattle feedlots, a VCPR is not always present, especially on smaller operations (U. S. Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, 2019, 2020). The situation is likely similar in other animal agriculture sectors. Even when a VCPR is present, the frequency of veterinary visits and likely extent of engagement on individual operations can vary considerably. Support of veterinary oversight may include empowering veterinarians via education and providing practical, value-added, and audience-appropriate methods for ASP implementation and communication (Redding et al., 2020a; Gomez et al., 2021; Moore et al., 2021). Other studies, and the National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria, reinforce the opportunity for outreach and education of both veterinarians and producers to promote lasting behavior changes that can improve antibiotic stewardship (Speksnijder and Wagenaar, 2018; Federal Task Force on Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria, 2020). It is worth emphasizing that for this outreach and education to be the most successful, it must incorporate lessons learned from social science including how individual perceptions, attitudes, and values can impact the likelihood of antibiotic stewardship practices being adopted (Speksnijder and Wagenaar, 2018; Redding et al., 2020a,b; Moore et al., 2021). In tandem with veterinary engagement, regular review and assessment of progress made is necessary to ensure success and continued improvement of ASPs (Page et al., 2014; The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2018b). If and when site audits or assessments are conducted, another method that most of the certification programs could use to strengthen ASPs would be to require and support documentation and regular documented review or observation of the following: (1) antibiotic stewardship-related training and confirmation of understanding of any relevant requirements pertinent to antibiotic use or withdrawal; (2) on-farm implementation and adherence to VCPR and animal health plan recommendations; (3) animal health and productivity records, including reasons for any treatments; (4) farm-specific diagnostic and treatment practices and protocols, including practices to minimize the use of antibiotics; and (5) prescription records, including specific review of any prophylactic treatments, with recommendations for adjustments as necessary.

The results of this evaluation, and the application of the ASAT, are not limited to the certification programs included in our study, nor are they limited to sites that use antibiotic drugs. Multiple antibiotic stewardship principles apply to sites that do not use antibiotics (e.g., organic farms), or strictly limit their use, as many components focus on improving animal health and management with the goal of decreasing the need for antibiotic use in the first place. While the programs we included might have the broadest reach to stakeholders in the US, there are multiple additional US programs, possibly more narrowly focused (e.g., strictly focused on antibiotic use) or perhaps more generally applicable (e.g., antibiotic stewardship guidelines), that could use the ASAT. The ASAT is an easily used and thorough tool that, based on our review of certification programs, captured the primary elements that such programs include to effect antibiotic stewardship. The tool, therefore, can help programs to compare and evaluate their antibiotic stewardship requirements. Studies have shown that benchmarking stewardship practices among peers can have a positive impact spurring action and improving antibiotic stewardship behavior among veterinarians and farmers (Speksnijder and Wagenaar, 2018). As new evidence about antibiotic stewardship practices becomes available or new strategies gain acceptance (such as diagnostic stewardship), the metrics within the ASAT could also be expanded. Just as antibiotic use anywhere can lead to antibiotic resistance, stewardship implemented anywhere antibiotics are used has the potential to decrease the development and spread of antibiotic resistance.

While the potential impacts of antibiotic use in animal agriculture on antibiotic resistance in humans is often a primary driver of stewardship efforts in animal agriculture, antibiotic resistance can also have direct consequences on agricultural animals and their caretakers. For example, animals with resistant or difficult to treat infections may undergo more suffering or experience poor welfare. Studies have shown that antibiotic resistance in animals can lead to social-emotional and economic consequences for animal caretakers (Bengtsson and Greko, 2014; Salois et al., 2016; Dee et al., 2018). Furthermore, workers in direct contact with farm animals appear to be at greater risk of acquiring resistant organisms, making antibiotic stewardship outreach efforts to animal caretakers and veterinarians even more important (Bennani et al., 2020).

This study has several limitations. First, the inclusion criteria for certification programs resulted in a small number of programs with various scopes being evaluated. Other antibiotic stewardship-related programs that did not meet the ASAT criteria for being a certification program were not included. Second, we combined the information for different programs and the programs have different objectives and scopes. Third, this evaluation focused on the processes of the programs as described in publicly available written sources. These processes may not represent actual actions that happen on-farm. Fourth, we acknowledge that the application of the metrics within the ASAT to individual programs is somewhat subjective. We attempted to address this by creating a list of rules for what type of program information “met” a metric vs. only “partially met” a metric, and the breakdown of some metrics to separate actionable pieces also assisted with this issue, yet interpretation of program information and of metrics within the tool remain, to some extent, user dependent. Our process of verifying information gathered about each program with representatives from the respective programs was an additional way to address this limitation and to ensure our assumptions were valid. However, even verification from the program representatives regarding our interpretations of how metrics were met may have been somewhat subjective or biased in their favor.

Conclusion

This study offers valuable information regarding possible strategies to improve antibiotic stewardship metrics used by certification programs involved in animal agriculture. One of the programs met all of the metrics, while the other three varied widely and only partially met the metrics, indicating opportunities for enhancing the effectiveness of these certification programs in promoting antibiotic stewardship on farms. The area with the most potential for enhanced action is evaluation. Evaluation, as with evidence-based medicine, is critical to show actions are effective as well as to ensure accountability. The detailed assessment of existing certification programs presented in this study can help existing and future certification programs fill in potential gaps in ASP-related requirements and activities to potentially expand the reach and impact of their efforts.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

The work for this project was completed with support from The Pew Charitable Trusts Contract ID 34280.

Author Disclaimer

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the certification program representatives who graciously shared their time, provided additional information, and reviewed data gathered about their respective programs.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2021.724097/full#supplementary-material

References

American Association of Avian Pathologists (2018). American Association of Avian Pathologists (AAAP) Antimicrobial Stewardship for Poultry. Available online at: https://www.aaap.info/assets/Positions/AAAP%20Antimicrobial%20Stewardship.pdf (accessed December 10, 2020).

American Association of Bovine Practitioners (2017). Key Elements for Implementing Antimicrobial Stewardship Plans in Bovine Veterinary Practices Working With Beef and Dairy Operations. Available online at: https://www.aabp.org/resources/AABP_Guidelines/AntimicrobialStewardship-7.27.17.pdf (accessed December 10, 2020).

American Association of Swine Veterinarians (2020). Basic Guidelines Of Judicious Therapeutic use of Antimicrobials in Swine. Available online at: https://www.aasv.org/documents/JUG.php (accessed December 10, 2020).

American Veterinary Medical Association (2021). Antimicrobial Stewardship Definition and Core Principles. Available online at: https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/avma-policies/antimicrobial-stewardship-definition-and-core-principles (accessed March 11, 2021).

Australian Government (2017). “AMR and Animal Health in Australia,” in Antimicrobial resistance. Available online at: https://www.amr.gov.au/about-amr/amr-australia/amr-and-animal-health-australia (accessed July 17, 2021).

Beef Checkoff (2020). “Premiums and market drivers behind BQA-certified beef,” in Beef Checkoff. Available online at: https://www.beefboard.org/2020/01/14/premiums-and-market-drivers-behind-bqa-certified-beef/ (accessed June 11, 2021).

Bengtsson, B., and Greko, C. (2014). Antibiotic resistance—consequences for animal health, welfare, and food production. Ups. J. Med. Sci. 119, 96–102. doi: 10.3109/03009734.2014.901445

Bennani, H., Mateus, A., Mays, N., Eastmure, E., Stärk, K. D. C., and Häsler, B. (2020). Overview of evidence of antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance in the food chain. Antibiotics (Basel) 9:20049. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9020049

California Department of Food Agriculture (2021). Antimicrobial Stewardship. Available online at: https://www.cdfa.ca.gov/AHFSS/aus/Stewardship.html (accessed May 28, 2021).

Centers for Disease Control Prevention (2020). Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs | Antibiotic Use | CDC. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/core-elements/hospital.html (accessed September 22, 2020).

Davey, P., Marwick, C. A., Scott, C. L., Charani, E., McNeil, K., Brown, E., et al. (2017). Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices for hospital inpatients. Cochr. Database Syst. Rev. 9:2. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003543.pub4

Davies, P. R., and Singer, R. S. (2020). Antimicrobial use in wean to market pigs in the United States assessed via voluntary sharing of proprietary data. Zoon. Pub. Health 67, 6–21. doi: 10.1111/zph.12760

Dee, S., Guzman, J. E., Hanson, D., Garbes, N., Morrison, R., Amodie, D., et al. (2018). A randomized controlled trial to evaluate performance of pigs raised in antibiotic-free or conventional production systems following challenge with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. PLoS ONE 13:e0208430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208430

Federal Task Force on Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria (2020). National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria 2020–2025. Available online at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/264126/CARB-National-Action-Plan-2020-2025.pdf (accessed March 5, 2021).

Feyes, E. E., Diaz-Campos, D., Mollenkopf, D. F., Horne, R. L., Soltys, R. C., Ballash, G. A., et al. (2021). Implementation of an antimicrobial stewardship program in a veterinary medical teaching institution. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 258, 170–178. doi: 10.2460/javma.258.2.170

Food Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2016). The FAO Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance 2016–2020. Available online at: http://www.fao.org/3/i5996e/i5996e.pdf (accessed May 28, 2021).

Global Food Safety Initiative (2021). Recognition. Available online at: https://mygfsi.com/how-to-implement/recognition/ (accessed April 5, 2021).

Gomez, D. E., Arroyo, L. G., Renaud, D. L., Viel, L., and Weese, J. S. (2021). A multidisciplinary approach to reduce and refine antimicrobial drugs use for diarrhoea in dairy calves. Veter. J. 274:105713. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2021.105713

Government of Canada (2017). Responsible Use of Medically Important Antimicrobials in Animals. Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/antibiotic-antimicrobial-resistance/animals/actions/responsible-use-antimicrobials.html (accessed July 17, 2021).

Guardabassi, L., Apley, M., Olsen, J. E., Toutain, P.-L., and Weese, S. (2018). Optimization of antimicrobial treatment to minimize resistance selection. Microbiol. Spectr. 6:18. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.ARBA-0018-2017

Guardabassi, L., and Prescott, J. F. (2015). Antimicrobial stewardship in small animal veterinary practice: from theory to practice. Veter. Clinic. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 45, 361–376. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2014.11.005

Hope, K. J., Apley, M. D., Schrag, N. F. D., Lubbers, B. V., and Singer, R. S. (2020). Comparison of surveys and use records for quantifying medically important antimicrobial use in 18 U.S. beef feedyards. Zoon. Pub. Health 67, 111–123. doi: 10.1111/zph.12778

Karavolias, J., Salois, M. J., Baker, K. T., and Watkins, K. (2018). Raised without antibiotics: impact on animal welfare and implications for food policy. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2, 337–348. doi: 10.1093/tas/txy016

Lloyd, D. H., and Page, S. W. (2018). Antimicrobial stewardship in veterinary medicine. Microbiol. Spectr. 6:23. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.ARBA-0023-2017

Minnesota Department of Agriculture (2021). Antibiotic Stewardship. Available online at: https://www.mda.state.mn.us/food-feed/antibiotic-stewardship (accessed April 8, 2021).

Moore, D. A., McConnel, C. S., Busch, R., and Sischo, W. M. (2021). Dairy veterinarians' perceptions and experts' opinions regarding implementation of antimicrobial stewardship on dairy farms in the western United States. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 258, 515–526. doi: 10.2460/javma.258.5.515

More, S. J. (2020). European perspectives on efforts to reduce antimicrobial usage in food animal production. Ir. Vet. J. 73:154. doi: 10.1186/s13620-019-0154-4

More, S. J., Hanlon, A., Marchewka, J., and Boyle, L. (2017). Private animal health and welfare standards in quality assurance programmes: a review and proposed framework for critical evaluation. Veter. Rec. 180, 612–612. doi: 10.1136/vr.104107

Nathwani, D., Varghese, D., Stephens, J., Ansari, W., Martin, S., and Charbonneau, C. (2019). Value of hospital antimicrobial stewardship programs [ASPs]: a systematic review. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 8:35. doi: 10.1186/s13756-019-0471-0

National Dairy FARM Program (2021). National Dairy FARM Program 2020 Year in Review. Available online at: https://nationaldairyfarm.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/FARM_YearInReview_2020_FINAL_021821_Web_pages.pdf (accessed June 9, 2021).

OIE World Organisation for Animal Health (2016). The OIE Strategy on Antimicrobial Resistance and the Prudent use of Antimicrobials. Available online at: https://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/Media_Center/docs/pdf/PortailAMR/EN_OIE-AMRstrategy.pdf (accessed July 17, 2021).

Page, S., Prescott, J., and Weese, S. (2014). The 5Rs approach to antimicrobial stewardship. Veter. Rec. 175, 207–208. doi: 10.1136/vr.g5327

Redding, L. E., Brooks, C., Georgakakos, C. B., Habing, G., Rosenkrantz, L., Dahlstrom, M., et al. (2020a). Addressing individual values to impact prudent antimicrobial prescribing in animal agriculture. Front. Vet. Sci. 7:297. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.00297

Redding, L. E., Muller, B. M., and Szymczak, J. E. (2020b). Small and large animal veterinarian perceptions of antimicrobial use metrics for hospital-based stewardship in the United States. Front. Vet. Sci. 7:582. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.00582

Salois, M. J., Cady, R. A., and Heskett, E. A. (2016). The environmental and economic impact of withdrawing antibiotics from US broiler production. J. Food Distrib. Res. 47, 79–80. doi: 10.22004/ag.econ.232315

Samuel, R., Thaler, R., and Carroll, H. (2020). Introducing PQA Plus Version 4. Available online at: https://extension.sdstate.edu/introducing-pqa-plus-version-4 (accessed June 10, 2021).

Sargeant, J. M., O'Connor, A. M., and Winder, C. B. (2019). Editorial: Systematic reviews reveal a need for more, better data to inform antimicrobial stewardship practices in animal agriculture. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 20, 103–105. doi: 10.1017/S1466252319000240

Schrag, N. F. D., Godden, S. M., Apley, M. D., Singer, R. S., and Lubbers, B. V. (2020). Antimicrobial use quantification in adult dairy cows – Part 3 – Use measured by standardized regimens and grams on 29 dairies in the United States. Zoon. Public Health 67, 82–93. doi: 10.1111/zph.12773

Singer, R. S., Porter, L. J., Schrag, N. F. D., Davies, P. R., Apley, M. D., and Bjork, K. (2020a). Estimates of on-farm antimicrobial usage in broiler chicken production in the United States, 2013–2017. Zoon. Pub. Health 67, 22–35. doi: 10.1111/zph.12764

Singer, R. S., Porter, L. J., Schrag, N. F. D., Davies, P. R., Apley, M. D., and Bjork, K. (2020b). Estimates of on-farm antimicrobial usage in turkey production in the United States, 2013–2017. Zoonoses and Public Health 67, 36–50. doi: 10.1111/zph.12763

Singer, R. S., Porter, L. J., Thomson, D. U., Gage, M., Beaudoin, A., and Wishnie, J. K. (2019). Raising animals without antibiotics: U.S. producer and veterinarian experiences and opinions. Front. Vet. Sci. 6. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00452

Speksnijder, D. C., and Wagenaar, J. A. (2018). Reducing antimicrobial use in farm animals: how to support behavioral change of veterinarians and farmers. Anim. Front. 8, 4–9. doi: 10.1093/af/vfy006

The Pew Charitable Trusts (2018a). Framework for Antibiotic Stewardship in Food Animal Production. Available online at: https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2018/12/framework-for-antibiotic-stewardship-in-food-animal-production_dec19.pdf (accessed May 28, 2021).

The Pew Charitable Trusts (2018b). Groups Issue Framework for Antibiotic Stewardship in Food Animal Production. Available online at: https://pew.org/2QIJo39 (Accessed March 4, 2021).

University of Minnesota (2021). Antimicrobial Resistance and Stewardship Initiative. Available online at: https://arsi.umn.edu/ (accessed April 5, 2021).

U. S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Marketing Service (2020). One Health Certified. Available online at: https://www.ams.usda.gov/services/auditing/one-health (accessed June 10, 2021).

U. S. Department of Agriculture Animal Plant Health Inspection Service. (2019). Antimicrobial Use and Stewardship on US Feedlots, 2017. Available online at: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/nahms/downloads/amu-feedlots.pdf (accessed March 30, 2021).

U. S. Department of Agriculture Animal Plant Health Inspection Service. (2020). Antimicrobial Use and Stewardship on US Swine Operations, 2017. Available online at: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/nahms/amr/downloads/amu-swine.pdf (accessed December 10, 2020).

U. S. Food Drug Administration (2012). Guidance for Industry #209: The Judicious use of Medically Important Antimicrobial Drugs in Food-Producing Animals. Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/media/79140/download (accessed April 5, 2021).

U. S. Food Drug Administration (2013). Guidance for Industry #213: New Animal Drugs and New Animal Drug Combination Products Administered in or on Medicated Feed or Drinking Water of Food-Producing Animals: Recommendations for Drug Sponsors for Voluntarily Aligning Product use Conditions with GFI #209. Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/media/83488/download (accessed April 5, 2021).

U. S. Food Drug Administration (2021). Guidance for Industry #263: Recommendations for Sponsors of Medically Important Antimicrobial Drugs Approved for use in Animals to Voluntarily Bring Under Veterinary Oversight all Products that Continue to be Available over-the-Counter. Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/media/130610/download (accessed July 15, 2021).

U. S. Poultry Egg Association (2019). Antimicrobial use Within US Poultry Production. Available online at: https://www.uspoultry.org/poultry-antimicrobial-use-report/index.cfm (accessed May 28, 2021).

U. S. Poultry Egg Association (2021). Economic Data. Available online at: https://www.uspoultry.org/economic_data/ (accessed June 11, 2021).

Weese, J. S., Page, S. W., and Prescott, J. F. (2013). “Antimicrobial Stewardship in Animals,” in Antimicrobial Therapy in Veterinary Medicine, eds. S. Giguere, J. F. Prescott, and P. Dowling (Ames, Iowa: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.), 117–132.

World Health Organization (2015). Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241509763 (accessed March 11, 2021).

Keywords: antibiotic stewardship, antibiotic stewardship program, antibiotic resistance, antimicrobial stewardhip, antimicrobial stewardship program, antimicrobial resistance, animal agriculture, certification program

Citation: Umber JK and Moore KA (2021) Assessment of Antibiotic Stewardship Components of Certification Programs in US Animal Agriculture Using the Antibiotic Stewardship Assessment Tool. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5:724097. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2021.724097

Received: 11 June 2021; Accepted: 11 August 2021;

Published: 20 September 2021.

Edited by:

Terence Centner, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, United StatesReviewed by:

Dubraska Diaz-Campos, The Ohio State University, United StatesIan Jenson, Meat and Livestock Australia, Australia

Copyright © 2021 Umber and Moore. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jamie K. Umber, dW1iZXJAdW1uLmVkdQ==

Jamie K. Umber

Jamie K. Umber Kristine A. Moore

Kristine A. Moore