94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Food Syst., 13 July 2021

Sec. Sustainable Food Processing

Volume 5 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.703223

This article is part of the Research TopicConsumer Behavior and Sustainability in the Food ChainView all 9 articles

Marketing communication concerning the consumer in the retail food market is currently undergoing significant changes, based on a shift from the passive supply to manage the consumer, toward an effort to understand his needs. The changes in communication are influenced by the technological revolution, which has also significantly affected retail and consumer shopping behavior, resulting in the modern changes in how to approach customers nowadays. Marketing communication must respond to changes in purchasing behavior with the greatest possible flexibility and ability to follow current trends. The presented research will aim to present the importance of the topic and emphasize its topicality by defining specific forms of communication causing an increase in consumer interest in local and sustainable food. Part of the aim of the presented work will be a general proposal for applying specific forms of marketing communication, increasing the interest of consumers in local foods characterized by the attribute of sustainability. The theoretical basis of the work presents current knowledge focused on marketing communication about sustainability in the food chain and consumers' relationship to local and sustainable food, which builds the communication. The work is based on collecting primary data and their subsequent management by mathematical and statistical methods. Friedman's test as a method used for data processing allows us to reveal differences in consumer preferences between various forms of standardized marketing communication to increase local, sustainable foods to engage the consumer. Independently of the Friedman test, the Chi-square test allows us to find races among the individuals corresponding to the respondents. The research results reveal that the differences between the various forms of standardized marketing communication bring a new perspective on the role of communication with the consumer. The results also reveal the role of a specific label expressing the sustainability of local foods. The benefit of our work is to set recommendations for producers and distributors of local and sustainable foods in the field of marketing communication.

Currently, there is a strong trend of environmental protection in all areas of life. Large organizations, manufacturing companies, wholesalers, retailers or private sector entrepreneurs have included environmental and consumer health protection into most processes in their organization/company. They realize that environmental protection is not only a topical issue, but it is an important topic (Krajčovič and Cábyová, 2020), which is to a great extent connected with the future of all generations.

This is the same with the food industry. These companies strive to grow and produce products with the lowest possible negative impact on the environment where we are located and live and on consumers' health. In the last few years, however, we have seen a change in shopping behavior patterns on the part of consumers, who have decided to use more sustainable products in their lives (Zamora and Ruiz, 2019). According to Mkhize and Ellis (2019), organic and local purchasing are considered activities with a positive impact on sustainable development because they contribute to environmentally friendly behavior. This behavior is mainly due to their constant awareness of environmental degradation and the growing scarcity of natural resources. Growing health concerns due to the growing number of chemical poisoning cases worldwide act as a driving force in the organic food market. Consumers are increasingly aware of the deeper meaning of the word “health” due to the harmful effects caused by the presence of chemical pesticides in food. Promoting and accelerating the adoption of environmentally friendly consumer behavior is key to environmental sustainability (Taufique et al., 2016). The great importance of sustainability stems from the many challenges of today's globalized world, with which society is constantly struggling (Buerke et al., 2016). Sustainable consumption and production are defined as a holistic approach to minimizing the negative impacts of consumption and production systems on the environment while promoting quality of life for all parties involved (Borusiak et al., 2020). Among the different types of environmental behavior, the purchase and consumption of sustainable products, including organic and sustainable foods, significantly contributes to improving the quality of the environment (Davari and Strutton, 2014). Due to the many environmental consequences of an unsustainable economy, the consumption of local and organic foods is gradually becoming one of the most popular alternatives to sustainable consumer behavior (Gan et al., 2016). Sustainable food is one of how consumers can adopt more responsible behavior toward the environment and society as a whole in order to protect present and future generations (Laureti and Benedetti, 2018). Exactly this fact has created many business opportunities in the market for sustainable and local foods and thus contributed to the sustainable growth of the organic economy over the last decades (D'Amico et al., 2016). For these local businesses to use the principles of the organic economy in their production, they first need to use the right forms of marketing communication, which is very closely linked to the perception of consumer confidence in sustainable food. Foroudi et al. (2020) understand trust primarily as a mental state involving accepting sensitivity to auspicious motives. In connection with sustainability, green marketing, and consumers, the “green trust” concept becomes very well known. Green trust is crucial for companies, including agricultural ones, in the context of strict international environmental regulations and the prevailing environmentalism of customers. Consumers tend to rely on corporate advertising and information to make environmental choices, and often misleading and not true product advertising significantly “undermines” this trust (Chen and Chang, 2012). Some studies point out that many consumers perceive a lack of confidence in sustainable goods (Sangkumchaliang and Huang, 2012; Tung et al., 2012; Nuttavuthisit and Thøgersen, 2015), which can significantly limit the development and growth of demand. Consumers are increasingly more skeptical due to the increasing use of greenwashing and express their distrust of crop control or certification processes. According to Zamora and Ruiz (2019), organic foods are a truly classic example of possible unreliable goods, as consumers cannot verify whether or not a product has been produced/grown based on promised characteristics and conditions. Delmas and Burbano (2011) define “greenwashing” as combining two types of society's behavior: poor environmental performance and positive communication from society about this environmental performance. According to Seele and Gatti (2015), greenwashing exists only in combination with misleading communication about CSR with accusations by a third party (consumer, environmental movements, etc.). In other words, it is the misleading of consumers, which represents a kind of gap between symbolic and factual activities within the company's initiative following the approach of sustainability. There are many obstacles to choosing sustainable, healthy or local foods, including greenwashing and (Torelli et al., 2019), personal values, getting familiar with the product or lack of knowledge and product information (Folwarczny et al., 2021, Szabo and Webster, 2020). This is why a well-chosen marketing communication and its forms play a key role in promoting sustainable and local foods, which can significantly influence the environmental behavior of consumers. Governments and scientists alike agree on the need to provide consumers with clear and comparable information on the impact of food on the environment (Lazzarini et al., 2018). At the same time, a survey conducted by Aschemann-Witzel and Peschel (2019) showed that communication efforts could influence attitudes toward sustainable food. Sustainable marketing activities generally positively impact brand image, company growth, and longevity (Jung et al., 2020). According to Choi and Sung (2013), these organizations focus primarily on consumer satisfaction, their social and ethical needs, such as providing cultural support, environmental protection or support in case of any unexpected disaster. Sustainable marketing activities, in turn, have a positive impact on improving the brand image, company growth and longevity. According to Vilkaite-Vaitone and Skackauskiene (2019), the biggest benefits of environmental marketing communication include: strengthening customer relationships, increasing profits, achieving organizational goals, strengthening competitive advantage, reducing costs or improving brand reputation. According to Lewandowska et al. (2017), however, creating effective and easy-to-understand eco-marketing communication can be a real challenge for manufacturers and retailers. Green marketing, in general, incorporates philosophy and a wide range of other activities to satisfy the needs and wishes of consumers and thus create a favorable position for the company by communicating its environmental, social and economic interests (Villarino and Font, 2015). In the case of sustainable and local foods, farmers and retailers aim to market the benefits of consuming organic products, leading to an increase in organic purchases (Mkhize and Ellis, 2019). At the same time, in order to reduce consumers' distrust of the information provided, subjects should focus on providing accurate and consistent reports on the benefits of consuming sustainable and local products not only for individual consumer needs but also for the general public and the environment (Cant et al., 2017). For managers in an organization to establish effective communication, they must direct the recipient to what they want to communicate in a simple, direct and accurate way, spoken or written. At the same time, to achieve this goal, gender and cultural differences in consumers should be taken into account in connection with communication (Genç, 2017). Comprehensibility of communication is generally defined as the absence of ambiguity, inadequacy or informative misleading of the consumer. Comprehensibility and clarity of information are also considered a key factor in the communication intermediary as it contributes to increasing consumer credibility in the information provided, to increasing one's knowledge and awareness of organic products while contributing to the right choice of organic food in shopping behavior (Strijbos et al., 2016). According to the study results by Pham et al. (2018), “topics related to food” (food sustainability, sustainable food consumption) should be communicated and promoted mainly through mass and social media. This survey also points to the fact that communication campaigns should provide clear and honest information on organic farming methods, nutritional values, and environmental benefits associated with organic food. At the same time, key information regarding the production and consumption of sustainable foods should be communicated through educational interviews with media celebrities and professionals (Pham et al., 2018). When adopting marketing strategies within individual products, marketing professionals must also have an in-depth understanding of consumer behavior evoked by marketing communication from different perspectives of these food products (Peschel et al., 2019). The most used formulas within the basic forms of marketing communication include, for example, direct announcement, testimony, demonstrations of the product or a distinctive personality, etc. (Arens et al., 1994). In our present study and survey, in connection with the promotion and marketing communication of sustainable and local foods, we, therefore, focused primarily on direct message announcement, which we consider as the direct message of the product itself, producer and user of sustainable and local foods. Direct message announcement is one of the oldest and simplest production formats for advertising. It is used in campaigns that do not have a complex creative concept, but their task is primarily to acquaint the target group with the product's characteristics (Arens et al., 1994). In our case, we focused our research on local products, characterized by attributes such as fair trade, environmental friendliness, bio, vegan, and products produced following environmental management principles. Within the research, these attributes were incorporated into advertising slogans based on which the respondents' preferences in the area of the most suitable form of marketing communication in correlation with the selected attribute were researched.

Although several experts and scientists suggest how sustainable consumption could be communicated (Vergragt et al., 2016; Mandujano et al., 2021; Weder et al., 2021), communication on sustainable consumption, in contrast to communication on climate change, has not yet developed into a consolidated area of research. Therefore, given this fact and the extensive damage caused by the still unsustainable practices of the agricultural industry, the contribution significantly expands the particular area of research and supports local and sustainable entities in the correct setup of their marketing communication. The paper brings current knowledge focused on marketing communication on sustainability in the food chain and consumers' relationship to local and sustainable food, which builds the communication. Based on the formulated hypotheses, the study's authors would like to confirm or decline the correlations between the particular form of marketing communication and its perception by the respondents.

The aims and benefits of the paper are supported by the methodological procedure, methods and material used. The methodology is appropriate to the primary research objective of the study, in particular, to determine whether there is a possibility to achieve a higher preference for a sustainable food product through a particular type of advertising slogan. This research seeks to reveal the differences in the success of standardized advertising slogans and the factors influencing the success of the application of sustainable food products through standardized advertising slogans in the food market, using the acquired theoretical background and empirical research. The standardized advertising slogans were based on direct announcements, which have been known on the market for a long time (Arens et al., 1994). Any other research did not influence the concept of our research, and its methodological framework is based only on the possibilities of logical use of mathematical-statistical methods of data processing obtained by primary research. Therefore, we can state that this article suggests 5 standardized slogans for specific foods labeled with a sustainability attribute, one question about what kind of advertising slogan is consciously preferred by consumers and one about trust in sustainability attributes. These questions are then evaluated according to whether there is a difference in preferences or a specific dependence. The fact that this article is not methodologically based on any other research may, on the one hand, be considered as a lack, as its results cannot be compared with other articles. However, on the other hand, this article may set the base for other researchers to research the appropriateness of our article but especially would like to explore the possibility of measuring the preferences of advertising slogans.

The research involved 632 respondents with different demographic characteristics who provided information for the needs of this research. The research focused on respondents aged 20–30 who lived in the Slovak Republic at the research time. Respondents forming the research sample were characterized by different income, employment status, gender or housing in the city or in the countryside, which provided the possibility of determining the dependence of the preference of the type of advertising slogan on one of the listed attributes. The research was conducted through the online tool Google Forms, through which data was collected from respondents. The research took place in the first quarter of 2021. The questionnaire testing consisted of two parts. The first part of the questionnaire questioned the demographic characteristics of the respondents. The second part of the questionnaire collected the conscious opinions of respondents about their preferences concerning the type of advertising slogans of selected types of food products. The second part of the questionnaire contained 7 questions. Five out of six questions in a standardized form simulating practical use required the respondent to mark the preferences in the rankings according to the personal assessment of the attractiveness of a standardized advertising slogan, which would persuade the person to buy the product the most, medium and the least.

Advertising slogans were typed into:

• Direct message on product values (Slogan type 1)

• Direct message on producer values (Slogan type 2)

• Direct message on user values (Slogan type 3)

The wording of the advertising slogans related to the attributes indicating specific types of sustainability used in food products. Sustainability attributes were assigned to specific products in order for respondents to mark the order of their preferences and the advertising messages created, as follows:

1. Attribute – Ecological

• Local tomatoes “Bobulky” will win you over with their excellent taste, rich color and traditional aroma. Their organic cultivation means that they are free of added pesticides and environmentally friendly.

• The founders of the local Farma Bobulky rely on ecological practices when growing tomatoes, such as watering them with rainwater or using natural sprays without pesticides. All this with an essential ingredient of love is a guarantee of their delicious taste.

• When buying tomatoes in a supermarket, Tomáš always looks for the products of local farmers. He likes tomatoes Bobulky the most because of their fascinating aroma and taste and the knowledge that they are really healthy and honestly grown.

2. Attribute - Vegan

• Legumes form the basis of tasty traditional vegan LUT-ner spreads. Their use is extensive. They are of pure plant origin, without gluten and preservatives. They are based on local soy without GMOs.

• With a 30-year tradition, LUT-ner relies on the taste and proper nutritional value of its plant products. Through tasty vegan spreads, it tries to contribute to changing the eating habits of its customers.

• Carolina is a big fan of LUT-ner spreads. Mexican, French or chickpeas – she likes them all, because they contain local soy without GMOs and she knows that LUT-ner legume spreads are full of quality proteins and great taste.

3. Attribute - Fairtrade

• Enjoy a cup of aromatic locally roasted organic coffee Zlaté zrno of the highest quality, the unique taste you can enjoy at home while knowing that the grower was also honestly paid for his work.

• Local coffee roaster Zlaté zrno is based on the fairness of buying coffee toward producers and processes its organic coffee in traditional methods to preserve everything a good roaster can offer.

• Carolina bears a great responsibility in her job, but with a cup of selected delicious and organic coffee from the roast of Zlaté zrno, she can swap her mind to be instantly on an exotic plantation while accompanied by the satisfied grower, but also encourage herself for the rest of the day.

4. Attribute – Bio/Environmentally friendly

• The first Biodynamic wine is grown in our vineyards! The grape berries of Rozália wine ripen on the sunniest slopes of our south in a vineyard that operates on its abilities. Taste wine combined with nature, without pesticides and added sulfur!

• Rozália and Július are pioneers of our wines. They decided to bring back traditions to our vineyards and grow grapes in harmony with nature, building its natural defenses. Taste the first Biodynamic wine Rozália, without sulfur and pesticides!

• Tomas is a lover of quality wine. Therefore, there is no surprise that the first Biodynamic wine Rozália, using the natural defenses of the vineyard, got his attention. Try the taste of wine Rozália from berries grown in the sun, without sulfur and artificial pesticides in organic quality!

5. Attribute – EU requirements on food safety

• The delicious taste of home-made cheese characterizes smoked cheese from the Syrček dairy, the tradition of production and the guarantee of production according to environmental management standards, based on international standards focused on sustainability.

• Syrček Dairy celebrated its 60th anniversary with the success of opening its gates to the export markets of our delicious home-made cheese. The international standard focused on the sustainability of production specifies the environmental management system requirements, which foreign partners will certainly appreciate.

• Francis has been working at the local Syrček dairy for 28 years. The taste of their smoked cheese is the only and delicious for him even after so many years. Like this cheese, he is also pleased that because of František, the company can boast about introducing new environmental practices in line with international standards introducing sustainable management into businesses.

The sixth question of the second part of the questionnaire was formulated as a control or as a reference question. The respondents' task was to mark the order of preferences according to which the food product marked as sustainable could reach and affect them the most, medium or the least. The wording of the answers to the question was as follows:

• Direct announcement of product values - Highlighting the story of the product itself and the benefits or differences connected or related to the product.

• Direct communication about the producer's values - Telling the story, not about the product but the people or stories of the companies producing food.

• Direct communication of user values - A story from a third party, such as a satisfied family with both the product and the grower.

The seventh question in the second part of the questionnaire examined the attitudes of respondents expressing their confidence in “better shopping” at sustainable food spas.

A total of 632 respondents participated in the research. Data collection was preceded by pilot testing in the form of a questionnaire test on a sample of 27 respondents. The successful implementation of the requirements for proper adjustment was followed by data collection aimed primarily at respondents aged 20–30. The questionnaire was also randomly distributed to other residents of Slovakia through different groups and of different ages on social networks. The questionnaire was distributed in several stages, in different forms containing different order of questions, trying to avoid distortion of the informative value of the questionnaire caused by a higher probability of choosing the first options. Data obtained from 632 respondents were adjusted for respondents who marked two or more options in one question with the same numerical evaluation. After checking the logical correctness, the following processing and evaluation of responses were performed based on information obtained from 598 respondents (n = 598). The evaluation of the obtained information and the statistical verification of the established hypotheses took place utilizing the Friedman test and the chi-square test. Using the Friedman test, we evaluated whether there is a difference in the preferences of selected types of advertising slogans of food products with the attribute of sustainability. Friedman's test characterizes a model in the form yij = m + αj + βi + eij where (i = 1, 2, ., ni), (j = 1, 2, ., k). In this model, “yij” represents the value of the character, “m” the unknown common level, “αj” the unknown effect of the i-th row, “βi” the unknown effect of the j-th column and “eij” represents random errors, that should be mutually independent and should have a continuous distribution. Friedman's test is characterized by its hypotheses, which can generally be formulated as follows:

H0: β1= β 2=. β k - the effects are equal

H1: $ r, s: β r ≠ β s - there is at least 1 pair, where the effects are not equal

After setting the hypotheses, the calculation is performed so that all values of “yij” are arranged according to size within the respondent's choice; then we determine the values of the order “rij”, we calculate the total values of “Rj” representing the sums of the order of individual samples. Subsequently, the test characteristic is calculated in the form of:

where “k” expresses the number of orders.

Subsequently, the table value is determined from special tables, where s: (α, k, n). The conclusion of the test is evaluated as follows: H0 is rejected if F ≥ s (α, k, n)

Using the chi-square test, we evaluated the respondents' demographic characteristics on the results of preferences. Chi-square tests used data obtained through contingency tables containing the exact numbers of respondents based on selected characteristics such as age, education, gender or place of living within their answers:

where:

Oi = observed frequency

Ei = expected frequency

Eight hypotheses were identified for the examination and verification of relations: (see. Table 1.)

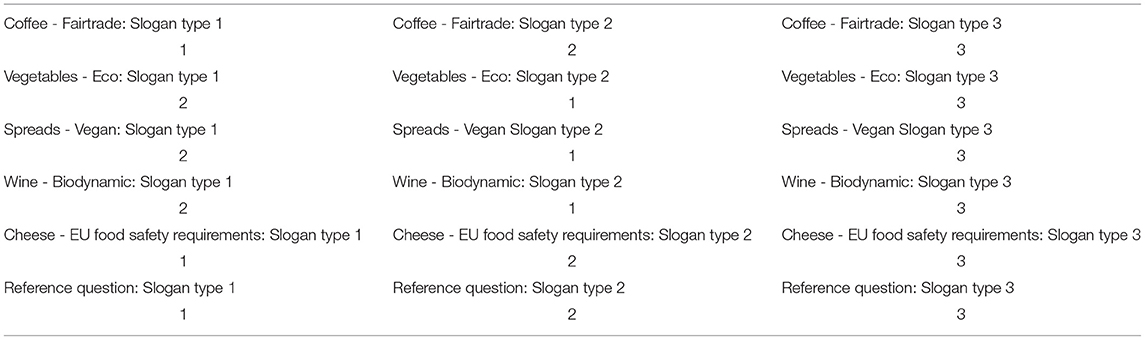

Based on the researched information, we were able to determine the order of slogans according to the respondents' preferences. Based on the answers, we rated each slogan from the best (1) to the least able to increase the interest of the respondents (3). The information results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Ranking of individual types of slogans according to the quantitative expression of the number of respondents' answers from the best (1) to the worlst (2); Source: own processing.

Based on the cumulative quantitative expression of the number of respondents' responses according to preferences for individual types of responses, it seems that the least attractive type of slogan for promoting food products with sustainability attributes is a type of slogan highlighting user values and product benefits. This is indicated by the results of the preferences for all model questions as well as the results of the reference question. Based on the cumulative quantitative expression of the number of answers to the reference question, we could conclude that the most attractive slogan is the type of slogan expressing the value of the product and the second of the three is the type of slogan expressing the values of the product producer. However, the results of the model questions suggest that the order of success of the slogans used in the natural market environment may differ. Based on this finding, there is a need for a statistical survey.

The statistical survey using the Friedman test calculated in Microsoft Excel was performed for each question of the second part of the questionnaire individually. The results point to the difficulty of making conclusions from the conscious answers of the respondents.

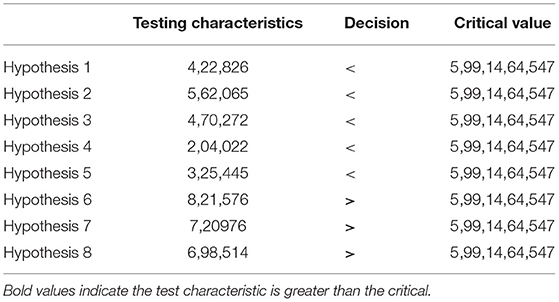

Friedman's test did not reveal any significant differences in the effects of model slogans. Therefore, based on the Friedman test, with a permissible error of 5%, it is impossible to determine which one is better with any of the model slogans. Thus, we reject Hypothesis 1 (H1), Hypothesis 2 (H2), Hypothesis 3 (H3), Hypothesis 4 (H4), Hypothesis 5 (H5). On the contrary, we confirmed Hypothesis 6 (H6), and thus when explicitly expressing the characteristics of individual types of advertising slogans, we can say that with 95% probability, there is a significant difference in respondents' preferences for individual types of advertising slogans. However, the discrepancy between the results obtained suggests the need for further research, as respondents seem to explicitly prefer to know about food products through direct communication of crucial product values, but in real life, they equally prefer communication of other values as well.

Using the Chi-square test, we researched the results of the reference question and looked for the dependence of personality characteristics and preference for the type of advertising slogan. Based on the Chi-square test, we can say with 95% probability that there is no relationship between the preference for the type of advertising slogan and age, gender or income. However, with a 95% dependence, there is a dependence between the preference for the type of advertising slogan and the residence in one of the eight administrative units of the Slovak Republic called the region. Based on these results, we confirm Hypothesis 7 (H7), which we accept. The dependence of the preference of the type of advertising slogan and residence indicates the need for further research to reveal the form of the dependence, as residence includes many socio-economic and other factors that may cause this dependence.

We also looked for the relationship between trust and the preference for advertising slogans through the chi-square test. We filtered respondents according to the preferred type of advertising slogan and obtained additional data for more detailed research through contingency tables. Based on the research results, we conclude with a probability of 95% that the respondents who preferred the 2nd type of advertising slogan showed higher confidence in the “good purchase” when buying sustainable food. The results of the comparison of test characteristics (F, χ2) and critical values (chinv) for individual hypotheses are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Results of the comparison of test characteristics and critical values during the statistical survey. Source: own processing.

Sustainable food is not just fancy news. Many of the authors we used as a source confirm (Taufique et al., 2016; Mkhize and Ellis, 2019; Zamora and Ruiz, 2019) that sustainable food sales and consumption will be an essential part of an increasing number of people globally. The drivers of the increase in such consumption will be the care for one's health and the awareness of the effects of previous consumption, characterized by pesticides, monocultural production, or plastic packaging.

The mission of scientists and researchers around the world is to help humanity for a better future. Therefore, this work seeks to shed more light on overcoming the barriers of young consumers characterized by price sensitivity. This barrier, which stands between producers producing sustainable food, often out of their own belief, to provide a better offer for consumers and consumers who often do not believe or know the benefits of sustainable food, does not seem so high in the light of our research to be not overcome. Therefore, our starting point in setting hypotheses was that proper marketing communication based on the principles of segmentation, targeting and positioning can help producers get their products into the shopping cart without the producer having to compromise on price or profit. To this end, it was necessary to find out what explicit and implicit preferences consumers have and reveal the relationships between their choices. Our goal was to clarify the issue of effective and easy-to-understand eco-marketing communication, the creation of which, according to Lewandowska et al. (2017), is still considered as a challenge. We agree with Mkhize and Ellis (2019), who say that in the case of sustainable and local foods, farmers and retailers aim to market the benefits of consuming organic products in a way that increases organic purchases but based on an analysis of available resources, we have found that there is no single recommendation on how this goal should be achieved. Therefore, based on the proven practice of direct advertising, which Arens et al. (1994) already clarified in 1994, we proposed an experiment to research whether there is a difference between certain types of direct advertising and whether the type of advertising can affect trust toward the communicated attributes. The results of our paper show that there is no universal key to what marketing communication or what type of advertising slogan consumers prefer. Although at first glance it may have seemed from the results of our research that it was clear that consumers had chosen a particular type of advertising slogan, closer research revealed that the preference for the type of advertising slogan is not clear. The results suggest that even though consumers would consciously prefer to learn as much as possible about the product directly through advertising slogans, thereby raising awareness of why it is beneficial to buy sustainable food. However, when choosing a model example of an advertising slogan, many expressed affection for information that brought producers closer to sustainable products and their value.

Ultimately, however, the statistical survey did not show a different effect of the type of advertising slogan on the overall preference of respondents. Therefore, the universal key must be replaced by knowledge of the target group. Therefore, estimating what affects the customer remains the marketer's art, who should inform and sell. Our efforts to identify the relationship between age, income and education as the primary personality characteristics of each of us did not show any sensitivity of a particular group of respondents to the recurring preference for the type of advertising slogan. An interesting but not surprising finding is the revealed dependence between the residence in one of the administrative units of the Slovak Republic called the region and the preference for the type of advertising slogan. We can say that the respondents living in the “richer” regions of the Slovak Republic showed a higher level of interest in the second type of advertising slogan, which brings the respondent closer to the value of the producer. This finding requires more attention for future research, as an administrative unit called a region involves many socio-economic links, from average GDP, through the quality of life to average income or infrastructure. However, this result may indicate that the producer's relationship-building activity can address respondents from a more developed environment. This finding is also in line with the statement, which was confirmed by Hypothesis 8. We can argue a statistically significant relationship between confidence in the product label expressing the sustainability attribute and the preferred type of advertising slogan. We found that respondents preferring the second type of advertising slogan, informing about the producer's values, showed the greatest confidence in a “good buy” when buying food marked with a sustainability attribute. On the contrary, although the reduced effect of the third type of slogan was not statistically confirmed, respondents who expressed the preferences of the third type of slogan, informing about the values of the user, expressed the lowest confidence in “good buy” when buying foods labeled as food with a sustainability attribute. This may indicate the existence of distrust of individuals in society. Therefore, we think that the future of successful promotion of sustainable food is in building integrated marketing communication, the transparent relationship of producers and distributors with their customers, and not pursuing short-term sales.

Based on the results obtained, we recommend that food producers seek to gain a significant position in the food market using the sustainability attribute to consider the benefits of advertising slogans and build the brand and personality of the company through values based on their values. An approach based on consumer values shows a higher degree of consumer confidence in the benefits of sustainable products, which can help overcome barriers and answer the consumer's purchasing decision in retails when choosing from different types of products, both local and sustainable though considered to be more expensive.

We would like to point out that this paper is based on data obtained from respondents living in one country. The data obtained from these respondents may not be global. Findings in the field of food market obtained from respondents in one country can bring specific results based on the cultural and historical development of the population of a given country and current social and political-economic characteristics, which may differ in another particular country.

We have also to note that the setup of hypotheses 1–5 is based on the authors' views or the content of the questions intended to collect primary data. Although the questions based on which hypotheses 1–5 were evaluated designed to be content-consistent, to be of approximately the same length, and to try to eliminate side effects as much as possible, such as the choice of the first options, we must say that any other research did not influence the concept of our research. Its methodological framework is based only on the possibilities of logical use of mathematical-statistical methods of data processing obtained by primary research. This article is therefore not methodologically based on any other research. This may be considered as a con, on the one hand, as its results cannot be compared with other articles, but on the other hand, this article may set the basis for other researchers who would like to research the appropriateness of our article but mostly would like to explore the option of measuring preferences of advertising slogans.

Sustainable agriculture and sustainable food consumption are among the many challenges facing humanity in light of population growth, pollution, diseases of civilization, or the loss of primary resources. The company is increasingly focused on environmental protection, local community development, ethical business and improving relationships with employees and partners (Bednárik and Augustínová, 2021). With the new technologies, education, lifestyle changes and well-being, consumers are increasingly concerned about the environment and a healthy lifestyle. Similarly, marketing as a scientific discipline, whether focused generally or specifically within the application in the conditions of a place or region, has developed dynamically in recent decades together with the political, business or technological environment (Darázs and Šalgovičová, 2021). Part of this change is the consumption and promotion of sustainable and local foods, which are considered chemical-free (Mayangsari et al., 2018).

Our research first focused on checking available resources and author definitions in this area. The research was designed to research if there is a possibility of achieving a higher preference for a sustainable food product through a particular advertising slogan. This research sought to reveal differences in the success of standardized advertising slogans and factors influencing their success in managing the application of sustainable food products through standardized advertising slogans in the food market using the acquired theoretical background and empirical research. Primary information was obtained from 598 respondents, subsequently processed by mathematical, statistical methods. Based on the results obtained, we recommend that food producers seek to gain a particular position in the food market using the sustainability attribute to consider the benefits of advertising slogans and build the brand and personality of the company through values based on their own. A consumer values approach shows consumers a higher degree of confidence in the benefits of sustainable products, which can help overcome barriers to consumer purchasing choices when choosing local and more sustainable products.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

TD is the author of the concept and design of the study, he also performed and evaluated the statistical survey as well as described the results of the research and its methodological procedure. MU mainly contributed to the review of available resources, as well as to the description of the theoretical basis of our study. TD together with MU were responsible for the concept and course of data collection, as well as for the formal design of the study. AK and JS contributed to the research of support, guidance and supervision of the whole course of research. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This contribution is a partial result of the project VEGA no. 1/0606/21 Change in preferences in consumer shopping behavior in the context of the dynamics of the development of marketing communication tools.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Arens, W., Bovée, F., and Courtland, L. (1994). Contemporary Advertising. 5th Edn. Burr Ridge; Boston; Sydney: Irwin, S. 300.

Aschemann-Witzel, J., and Peschel, A. O. (2019). How circular will you eat? the sustainability challenge in food and consumer reaction to either waste-to-value or yet underused novel ingredients in food. Food Qual. Preference 77, 15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.04.012

Bednárik, J., and Augustínová, N. (2021). “Communication of global aspects of corporate social responsibility in the circular economy,” in SHS Web of Conferences, 92. EDP Sciences. Available online at: https://search.proquest.com/openview/b63518594e4faa148fe06b4190f33ad8/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2040545 (accessed June 28, 2021).

Borusiak, B., Szymkowiak, A., Horska, E., Raszka, N., and Zelichowska, E. (2020). Towards building sustainable consumption: a study of second-hand buying intentions. Sustainability 12:875. doi: 10.3390/su12030875

Buerke, A., Straatmann, T., Lin-Hi, N., and Müller, K. (2016). Consumer awareness and sustainability-focused value orientation as motivating factors of responsible consumer behavior. Rev. Managerial Sci. 11, 959–991. doi: 10.1007/s11846-016-0211-2

Cant, M., van Heerden, C., and Makhitha, M. (2017). Marketing Management, A South African Perspective, 3 Edn. Cape Town: Juta.

Chen, Y. S., and Chang, C. H. (2012). Greenwash and green trust: the mediation effects of green consumer confusion and green perceived risk. J. Bus. Ethics 114, 489–500. doi: 10.1007/s10551-012-1360-0

Choi, M., and Sung, H. (2013). A study on social responsibility practices of fashion corporations. Korean J. Hum. Ecol. 22. 167–179. doi: 10.5934/KJHE.2013.22.1.167

D'Amico, M., Di Vita, G., and Monaco, L. (2016). Exploring environmental consciousness and consumer preferences for organic wines without sulfites. J. Cleaner Prod., 120, 64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.02.014

Darázs, T., and Šalgovičová (2021). Impact of the corona crisis on marketing communication focused on tourism. Commun. Today 12, 148–160.

Davari, A., and Strutton, D. (2014). Marketing mix strategies for closing the gap between green consumers' pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors. J. Strat. Mark. 22, 563–586. doi: 10.1080/0965254X.2014.914059

Delmas, M. A., and Burbano, V. C. (2011). The drivers of greenwashing. Calif. Manage. Rev. 54, 64–87. doi: 10.1525/cmr.2011.54.1.64

Folwarczny, M., Christensen, D. J., Li, P. N., Sigurdsson, V., and Otterbring, T. (2021). Crisis communication, anticipated food scarcity, and food preferences: preregistered evidence of the insurance hypothesis. Food Qual. Preference 91, 104–213. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2021.104213

Foroudi, P., Nazarian, A., and Aziz, U. (2020). The Effect of Fashion e-Blogs on Women's Intention to Use. (Cham: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-24374-6_2

Gan, C., Chang, Z., Tran, M. C., and Cohen, D. A. (2016). Consumer attitudes toward the purchase of organic products in China. Int. J. Bus. Econ. 15, 117–144.

Genç, R. (2017). The Importance of communication in sustainability & sustainable strategies. Procedia Manuf. 8, 511–516. doi: 10.1016/j.promfg.2017.02.065

Jung, J., Kim, J. S., and Kyung, H. (2020). Sustainable marketing activities of traditional fashion market and brand loyalty. J. Bus. Rev. 120, 294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.04.019

Krajčovič, P., and Cábyová, L. (2020). “Use of social media for marketing communication of socially responsible business activities in Slovakia,” in Proceedings of the ECSM 2020-−7th European Conference on Social Media, Larnaca, Cyprus, ed C. Karpasitis (Kidmore End, UK: Academic Conferences Ltd.), 135–143.

Laureti, T., and Benedetti, I. (2018). Exploring pro-environmental food purchasing behavior: an empirical analysis of Italian consumers. J. Cleaner Prod., 172, 3367–3378. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.11.086

Lazzarini, G. A., Visschers, V. H. M., and Siegrist, M. (2018). How to improve consumers' environmental sustainability judgments of foods. J. Cleaner Prod., 198, 564–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.033

Lewandowska, A., Witczak, J., and Kurczewski, P. (2017). Green marketing today – a mix of trust, consumer participation and life cycle thinking. Management 21, 28–48. doi: 10.1515/manment-2017-0003

Mandujano, G., Vergragt, P., and Fischer, D. (2021). “Communicating sustainable consumption,” in The Sustainability Communication Reader, eds F. Weder, L. Krainer, and M. Karmasin (Wiesbade: Springer), 263–279. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-31883-3_15

Mayangsari, I. D., Ferlina, Moch., Trenggana, A., Salmiyah Fithrah Ali, D., and Abdillah, F. (2018). Marketing strategy of organic products in bandung: farmer community, product innovation and social media. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 7:1286. doi: 10.14419/ijet.v7i4.38.27807

Mkhize, S., and Ellis, D. (2019). Creativity in marketing communication to overcome barriers to organic produce purchases: the case of a developing nation. J. Cleaner Prod. 242:118415. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118415

Nuttavuthisit, K., and Thøgersen, J. (2015). The importance of consumer trust for the emergence of a market for green products: the case of organic food. J. Bus. Ethics 140, 323–337. doi: 10.1007/s10551-015-2690-5

Peschel, A. O., Kazemi, S., Liebichová, M., Sarraf, S. C. M., and Aschemann-Witzel, J. (2019). Consumers' associative networks of plant-based food product communications. Food Qual. Preference 75, 145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.02.015

Pham, T. H., Nguyen, T. N., Phan, T. T. H., and Nguyen, N. T. (2018). Evaluating the purchase behavior of organic food by young consumers in an emerging market economy. J. Strat. Mark. 7, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/0965254X.2018.1447984

Sangkumchaliang, P., and Huang, W. (2012). Consumers' perceptions and attitudes of organic food products in Northern Thailand. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 15, 87–102. doi: 10.22004/ag.econ.120860

Seele, P., and Gatti, L. (2015). Greenwashing revisited: in search of a typology and accusation-based definition incorporating legitimacy strategies. Bus. Strat. Environ. 26, 239–252. doi: 10.1002/bse.1912

Strijbos, C., Schluck, M., Bisschop, J., Bui, T., de Jong, I., van Leeuwen, M., et al. (2016). Consumer awareness and credibility factors of health claims on innovative meat products in a cross-sectional population study in the Netherlands. Food Qual. Preference 54, 13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2016.06.014

Szabo, S., and Webster, J. (2020). Perceived greenwashing: the effects of green marketing on environmental and product perceptions. J. Bus. Ethics doi: 10.1007/s10551-020-04461-0

Taufique, K. M. R., Vocino, A., and Polonsky, M. J. (2016). The influence of eco-label knowledge and trust on pro-environmental consumer behavior in an emerging market. J. Strat. Mark. 25, 511–529. doi: 10.1080/0965254X.2016.1240219

Torelli, R., Balluchi, F., and Lazzini, A. (2019). Greenwashing and environmental communication: effects on stakeholders' perceptions. Bus. Strat. Environ. doi: 10.31219/osf.io/97vxn

Tung, S., Shih, C., Wei, S., and Chen, Y. (2012). Attitudinal inconsistency toward organic food concerning purchasing intention and behavior. Br. Food J. 114, 997–1015. doi: 10.1108/00070701211241581

Vergragt, P. J., Brown, H. S., Timmer, V., Timmer, D., Appleby, D. A., Pike, C., et al. (2016). Fostering and Communicating Sustainable Lifestyles: Principles and Emerging Practices. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/17016/fostering_Communicating_Sust_Lifestyles.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed June 28, 2021).

Vilkaite-Vaitone, N., and Skackauskiene, I. (2019). Green marketing orientation: evolution, conceptualization and potential benefits. Open Econ. 2, 53–62. doi: 10.1515/openec-2019-0006

Villarino, J., and Font, X. (2015). Sustainability marketing myopia. J. Vacation Mark. 21, 326–335. doi: 10.1177/1356766715589428

Weder, F., Karmasin, M., Krainer, L., and Voci, D. (2021). Sustainability Communication as Critical Perspective in Media and Communication Studies—an Introduction. The Sustainability Communication Reader: A Reflective Compendium. 1–12. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-31883-3_1

Keywords: local food, sustainable food, marketing communication of food, consumer behavior, forms of marketing communication, communication values

Citation: Kusá A, Urmínová M, Darázs T and Šalgovičová J (2021) Testing of Standardized Advertising Slogans Within the Marketing Communication of Sustainable and Local Foods in Order to Reveal Consumer Preferences. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5:703223. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2021.703223

Received: 30 April 2021; Accepted: 10 June 2021;

Published: 13 July 2021.

Edited by:

Laurent Dufossé, Université de la Réunion, FranceReviewed by:

Heru Irianto, Sebelas Maret University, IndonesiaCopyright © 2021 Kusá, Urmínová, Darázs and Šalgovičová. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tamás Darázs, ZGFyYXpzLnRhbWFzLjk1QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.