- Department of Management, Innovation, Sustainability, and Technology, School of Engineering, University of California-Merced, Merced, CA, United States

Food sovereignty encompasses the right of humans to have access to, and to produce, healthy and culturally appropriate food. Food sovereignty exists within the “social” pillar of sustainability and sustainable food production. Over time, and as a result of colonialism and neo-liberal food regimes, Indigenous food system patterns in boreal regions have been disrupted. Imports make local food production economically infeasible. The intersection of food sovereignty and international trade is understudied. Food insecurity cycles are likely to perpetuate without deliberate action and government intervention. Policies that facilitate local access, and ownership, of agriculture and food processing facilities may foster food sovereignty. Indigenous community governance, and agricultural practices, are critical to restoring environmental and social sustainability.

Introduction

Food sovereignty is a dynamic political framework that espouses local control over food systems (Desmarais, 2008). La Vía Campesina proposed this ideology in 1993 as a voice for peasants and small-scale farmers, who were becoming increasingly displaced by globalized agriculture and growing disparities in food access. The doctrine was also formalized in the eponymous Nyéléni Declaration, referring to “the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems” (La Vía Campesina, 2007, p. 1).

The food sovereignty movement was borne from awareness and adverse experiences stemming from neo-liberal policies that have given rise to powerful corporations that have shaped the global food system. Large volumes of agricultural products move across the globe, pricing many consumers and small-scale agricultural producers out of the market (McMichael, 2009). The grassroots mobilization of activist groups, including peasants and small producers from around the world, led to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas, or “UNDROP” in 2018 (Claeys and Edelman, 2020).

There is optimism that the UNDROP will advance recognition of basic human rights, including the right to food and food production, into practice (Claeys and Edelman, 2020).

The history and definition of “food sovereignty” is complicated (Edelman, 2014). Edelman refers to food sovereignty goals as those upholding the basic tenets of La Vía Campesina, the Nyéléni Declaration, and UNDROP, while simultaneously advancing food export policies that facilitate both food sovereignty and expanded agricultural production in boreal1 ecosystems. Food sovereignty supports a key pillar of sustainability, human social sustainability, which is necessary for achieving sustainable food production.

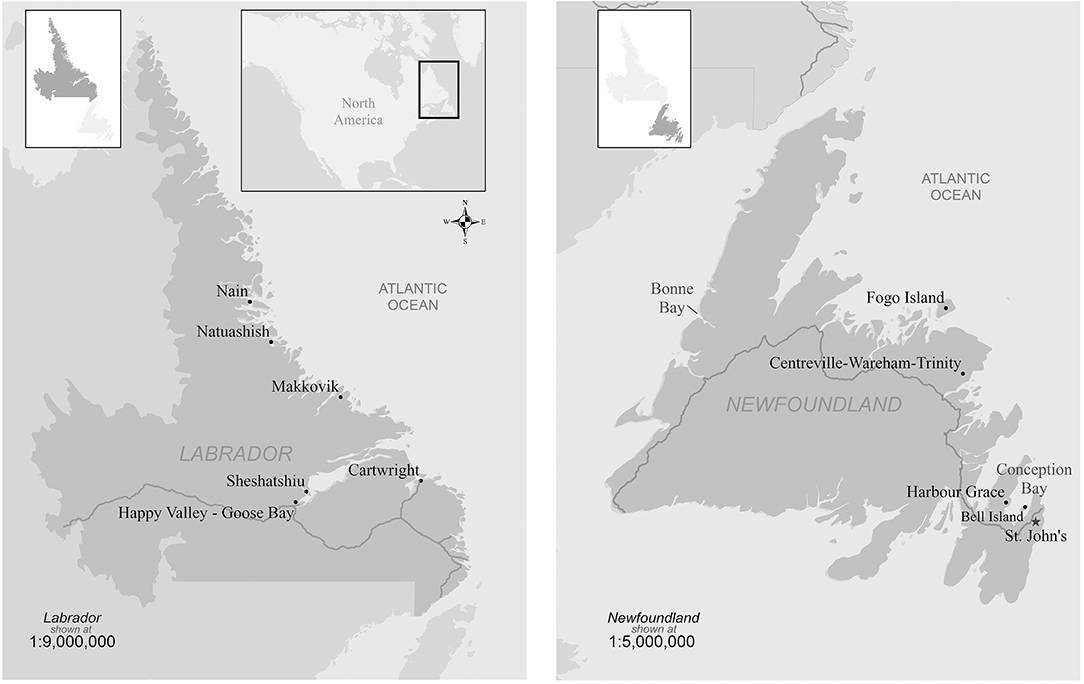

Study Region: Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada

To advance adoption of UNDROP's principles and food sovereignty in boreal regions of the world, this policy brief uses a threaded example from Atlantic Canada and specifically the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador, which is co-governed by the Nunatsiavut regional Inuit government (Nunatsiavut Government, 2021).2 The Nunatsiavut government represents ~7,000 Inuit of the Labrador Inuit land claim area. Labrador residents are of mixed descent and include Innu, Inuit, Southern Inuit (Inuit-MÃtis), and non-Aboriginal persons. Newfoundland is home to two Mi'kmaq communities, the self-governing Miawpukek Mi'kmaq First Nation, and the landless Qalipu Mi'kmaq Nation (Merrell, 2020). Approximately one-fifth of Newfoundland residents have applied for Qalipu Mi'kmaq First Nations Band recognition, which adds additional complexity to resource governance (Manning, 2018).3 Figure 1 depicts the province of Newfoundland and Labrador in eastern Canada.

Colonialism and resource exploitation have resulted in a near ecosystem and economic collapse in Newfoundland and Labrador, culminating in the infamous 1992 cod fishery moratorium, and a severe decline in shrimp, snow crab, and capelin stocks in recent years (Mullowney and Baker, 2020). A closer look at the study area illuminates patterns that should be avoided, and cautious optimism about future agricultural expansion. Corn, legume, dairy and livestock production is projected to increase in the study region (Cordeiro et al., 2019) and in many parts of the global boreal belt (King et al., 2018) due to rising temperatures associated with global climate change. Intensifying agricultural production in these regions without damaging the boreal forests could improve chronic food insecurity and environmental sustainability (Godfray et al., 2010). Like the study area, the world's boreal regions are sparsely populated with high biodiversity and natural resources, and Indigenous communities are reclaiming governance over their land and natural resources (Wells et al., 2020).

Newfoundland and Labrador's long history of European colonialism and resource exploitation has perpetuated a cycle of food insecurity and export practices that are not dissimilar to extraction communities across the boreal belt with fly-in-fly-out labor forces (Southcott et al., 2018). Parallels can be drawn to rural communities within the boreal ecosystems elsewhere that have social infrastructures similar to wealthy nations like Canada. Canada's safety net of social programs provides many (though not all) households with enough subsidized income for food and to just barely get by, but not enough security so as to regain providence over household or community food production and supply chains (Keske, 2018; Wilson et al., 2020).

In what is now Newfoundland and Labrador, sixteenth-century migratory fishing and transient European settlement attracted colonization and periods of contact with Indigenous persons. This evolved into unregulated permanent English settlement that increased throughout the eighteenth century (Cadigan, 1992, 2009). Over centuries, settler households depended upon fish exports to provide income for purchasing grocery and household staples.

As recently as the first half of the twentieth century, colonizing settlers and Indigenous communities considered themselves self-sufficient (Cadigan, 2009). They produced critical agricultural commodities like dairy, and they self-provisioned by harvesting local plants and wild game, defined by Indigenous communities as “country foods” or “traditional foods” (Skinner et al., 2013). However, a deeper anthropological and economic study has shown that many Indigenous communities were also dependent upon imported food for survival. Income from fish exports procured necessities like molasses, tea, and flour (Omohundro, 1994). Colonialization over hundreds of years assimilated non-native foods like root vegetables into many Indigenous communities in Atlantic Canada. Both settler and Indigenous communities gradually became increasingly dependent upon imports for household meals, and food exports for income to purchase basic essentials. These patterns created food systems that were adopted into cultural identities of Indigenous and settler communities over time (Keske, 2018, p. 15–17).

During the last half of the twentieth century, intensified neo-liberal trade policies and global demand for cod greatly increased exports to the point where the ecological carrying capacity of cod stocks in Atlantic Canada famously “crashed” in 1992. The food that instigated colonial settlement became unattainable for many households, who resultingly became increasingly reliant upon imported food for daily meals, not just staples. Though cod has slowly recovered under close regulation, other seafood (notably shrimp and snow crab) stocks present similar, disconcerting depletion trends. There are reverberating concerns about the impact of harvest quota restrictions on local employment and household income, and indirectly, household food security.4

The loss of land-based knowledge has forced Northern Indigenous communities to rely upon expensive imported food due to reduced access to local, healthy, and culturally appropriate foods (Egeland et al., 2011; Council of Canadian Academies, 2014). Approximately 25% of Indigenous households across Canada are food insecure, approximately double the rate of non-Indigenous households, and 62%-83% of households in Labrador are food insecure (Council of Canadian Academies, 2014). Chronic food insecurity has led to nutrient deficiencies in Indigenous communities that have been measured in biomarkers over time (Egeland et al., 2011). Newfoundlanders are also chronically food insecure, though food insecurity among the lowest income households has shown improvement as a result of targeted intervention programs, down from 60% of low-income households in 2007 to 34% in 2012 (Tarasuk, 2017, p. 13–14).

If agricultural production expands within Newfoundland and Labrador as predicted (King et al., 2018; Cordeiro et al., 2019), residents will ostensibly become less reliant upon imported food. To put this into practice, locally grown food needs to be locally processed and distributed, rather than exported. Thus, there needs to be sufficient household income to purchase locally grown foods that would face world price pressures, unless government price supports are imposed. If the past is a predictor of the future, arguably, the region's sparsely populated, rural areas may not have the population and income base to make local production enterprises profitable, unless the food is exported. Hence, without careful planning and deliberation, cycles similar to the North American cod and seafood fisheries and processing plants may extend to new agricultural enterprises, wherein nutritious, locally produced food is exported away from nearby communities, and corporate profits aren't reinvested into communities and local supply chains (Omohundro, 1994). Some Indigenous communities have shown interest and ownership in self-production to improve self-sufficiency and subsistence (Wells et al., 2020), though this may be difficult without supplemental household income (Arnaquq-Baril, 2016). Wilson et al. (2020, p. 298) observe that “…agriculture in the North requires a modified conceptualization of commercial scale. The distinctions between commercial, community, and subsistence production are much more fluid than in other parts of Canada.”

Food sovereignty can be viewed as a precursor to food security (Edelman, 2014). However, the study region is chronically food insecure. According to Cordeiro et al. (2019), Newfoundland is at the upper northern limit of crop production, with ~64 growing degree days and 1% of the land being arable. Excessive precipitation makes planting tenuous. Rocky and sandy soils will impede future agricultural production in many areas, even if temperatures rise as expected from global climate change (Ruckstuhl et al., 2008; Wells et al., 2020). Home gardening and home food production for self-sufficiency is time consuming, and involves commitment that is colligated against twenty first century lifestyles (Omohundro, 1994; Arnaquq-Baril, 2016). When opportunity cost is considered, it is unlikely that home food production will again reach the necessary scale to achieve the World Food Summit's definition of food security, particularly when technological advancement and efficient transport allows for clear comparative advantage of food production, like garden vegetables, in more temperate climates.

Food sovereignty is most likely to be achieved through initiatives that ensure that locally grown food remains within the region. This requires local governance of food resources and the supply chain.

Policy Options and Actionable Recommendations for Advancing Food Sovereignty and Sustainability in Boreal Ecosystems

Government Policy Must Prioritize the Right to Food From National to Local Scales

There are no straightforward answers to addressing the conundrum between the basic right to food that is juxtaposed against global, neo-liberal market forces that have improved food access for many, but not all. However, if the right to food under the Nyéléni Declaration is prioritized in boreal food system production at community, provincial, and national levels, then progress can be made to achieving food security and food sovereignty.

In 2019 Canada instituted its first national food policy, “Everyone at the Table” (Agriculture Agri-Food Canada, 2019) that addresses the social and environmental pillars of sustainability. The policy promotes inclusivity, diversity, and culturally appropriate food; lowering environmental impacts, such as reduced greenhouse gas reduction and waste; infrastructure investment to increase nutritious food production; and strong Indigenous food systems. Indigenous communities provide nuanced differentiation that there is community responsibility to provide food (Coté, 2016). This is embedded in hunter traditions of sharing meat and filling community freezers in the modern day (Arnaquq-Baril, 2016).

Canada's federal policy orients the principles promulgated by UNDROP and the basic tenants of La Vía Campesina and the Nyéléni Declaration. This is a good first step. Implementation must align at the community level (Wilson et al., 2020). It will take time to evaluate impacts of national policy on remote, rural communities, and to develop provincial and community policies.

Food Sovereignty Intersects and Challenges Colonial Values. Policies Must Be Reframed to Place Food Sovereignty at the Forefront

Over millennia, Indigenous persons hunted and gathered food within the regenerative capacity of the land and sea, in an environmentally and culturally sustainable manner that was synonymous with their self-identity (Coté, 2016). However, Indigenous food pathways are now also inextricably linked to the global economy. Regaining food sovereignty involves reducing dependence upon the colonialized global food system, upon which Indigenous peoples are paradoxically reliant, and in which they participate. Supplemental income is necessary to purchase fuel for hunting expeditions and grocery staples (Coté, 2016).

Colonial policies that reduce income to Indigenous communities intersects their food sovereignty. The displacement of Indigenous food pathways by colonial values needs to be acknowledged, and policies need to be reframed to uphold food sovereignty. The Inuit seal hunt serves a thought-provoking example of how colonial values have upended Inuit food sovereignty and food security. Seal hunting is universally recognized as a culturally appropriate, nutritious food source for Canada's Inuit. The international community is slowing becoming aware of how policies such as the EU's ban on the trade of seal products (European Union, 2010) exacerbated food insecurity among Indigenous persons. Income from the sale of seal pelts for clothing is vital to the Inuit for purchasing fuel and household supplies (Finger and Heininen, 2019). Without supplemental household income, would-be hunters seek employment outside of the community, perpetuating the cycle of reliance upon imported and commercialized food and community marginalization (Arnaquq-Baril, 2016; O'Neill, 2018). Emerging research suggests that decolonizing the international view of seal products and shifting the ontology around the definition of sustainability would be a step toward increasing food security and correspondingly, food sovereignty for the Inuit (Arnaquq-Baril, 2016; O'Neill, 2018).

Local and Indigenous Governance and Ownership Are Vital

The Nyéléni Declaration and La Vía Campesina imply, but fall short of, explicitly advocating for local control and resource ownership. This is likely because the movements inclusively advocate on behalf of tenant farmers, landless people, and other marginalized populations. However, local governance and ownership over resources and supply chains, including processing and distribution channels, are critical to upholding the right to food and to ensuring that future agricultural production is sustainable over time (Wilson et al., 2020). Local control over resources, including the supply chain, facilitates local harvesting and access to fresh food that might otherwise be viewed as valuable export commodities.

In North America, the gradual transition of returning land and resources to Indigenous populations is expected to gain momentum in years to come. There is opportunity to “relearn” the cycles of nature that have sustained Indigenous civilization over time. However, there is also growing awareness that boreal environments are dynamic; climate change presents uncertain impacts on future food harvesting practices. Moreover, resource transitions and co-governance with Indigenous communities has not necessarily been particularly smooth, as the Atlantic lobster fishery (Coletta, 2020) and building of the Muskrat Falls hydroelectric dam (Keske et al., 2020) have shown.

Regulation Will Be Necessary to Cultivate Food Supply Chains That Support Food Sovereignty

Food sovereignty is often interpreted to entail necessary conditions of local food consumption and distribution. Practices of and returns on trade directly would support food sovereign practices through commodity supply chains that closely connect farms and consumers, reducing the involvement of third-party intermediaries, particularly when profits are not locally reinvested.

Food sovereignty advocates for small farms to hold providence over all aspects of their crop production, distribution and consumption. This creates paradoxical tension with gains from comparative advantage and international trade, where the value of maintaining sovereignty typically isn't reflected in food prices. Reconciliating food sovereignty and agricultural trade, especially at an international scale, is a difficult endeavor (Burnett and Murphy, 2014). As Edelman (2014, p. 970) writes, “‘food sovereignty' advocates rarely consider what sort of regulatory apparatus would be needed to manage questions of firm and farm size, product and technology mixes, and long-distance and international trade.”

As discussed throughout this article, local food system disruptions accentuate differences between those who “have” and “have not.” In order to shift to a system that supports food sovereignty, the right to food, and local supply chains, regulatory support will be necessary. Regulation may be necessary to ensure that food from locally owned food processing and distribution centers remains available to local communities (Wilson et al., 2020).

One suggestion is to foster community-level ownership and regulatory mechanisms that involve equity and joint ownership. Returning to the Newfoundland and Labrador study region, in 1967 the Fogo Island Co-operative and Shorefast Foundation embraced these principles to “rebuild” the local fishing and harvesting processes into a community-owned enterprise, in a manner that has been dubbed the “Fogo Process” (Low, 1967). The Fogo Island Co-op was initially established as an alternative to federal and provincial initiatives to relocate residents to the mainland. Rather than relocate to mainland, like most communities, local inshore fishers and processing plant workers instead took control over the fisheries and supply chain. It provides the quintessential and perhaps most renowned example of food sovereignty stemming from the residents' awareness of the need to maintain local control over resources.

Providing each citizen with a universal basic income has gained appeal as a policy tool for addressing food insecurity (Ruckert et al., 2018; Tedds et al., 2020). As the economic impacts of universal income supports are being evaluated, it's worth evaluating whether a universal income might provide much needed income to cultivate local agricultural supply chains.

In sum, the scales required to attain food sovereignty may initially seem daunting. However, if agricultural production is introduced in a stepwise manner, there is opportunity to slowly foster supply chains at small scales or in pilot programs that can eventually be replicated.

Greater Understanding, Research, and Definition, Are Needed About the Intersectionality Between Food Production Models and the Basic Right to Food

My research team and I conducted a scoping review on food sovereignty and international trade to demonstrate that the vast majority of literature focuses on either food as a basic human right, or food production models, but that there is little intersectionality between the two. Research in this area is necessary in order to identify models of success, and policies, that can be replicated elsewhere.

To investigate the co-occurrence between research on food sovereignty and international trade and gaps in the literature, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were used as a methodological and analytical framework (Moher et al., 2009).

The Binimelis et al. (2014) framework was used to guide the scoping review. The framework consists of five axes or evaluative categories delineated from the Nyéléni Declaration: access to resources, production model, transformation and commercialization, food consumption and right to food, and agricultural policy and civil and social organizations.

A stepwise search covered all journals indexed by OVID journal databases, accessed through the University of Toronto's Gerstein Library research portal. The stepwise search of the terms [“international trade” and “food sovereignty”] yielded 213 net results. A second search was conducted via the ProQuest portal of the 3,236 publications indexed by the Social Sciences Combined Databases using the search terms [“trade” or “import” and “food sovereignty”] for a total of 645 results, and a combined total of 858 articles. After sorting for duplicates and other criteria, 34 articles were retained from the first literature search and 29 articles from the second search, yielding 63 articles for further semantic analysis of paragraphs.

Nearly all of 63 articles on food sovereignty focused on either the production model, or the right to food model, but there was little co-occurrence between the two categories. This builds upon observations made by Edelman (2014) and others that food sovereignty remains an elusive term that is aspirational in principle, but difficult to implement. This scoping review fortifies the observation that two aspects of the food sovereignty movement, the “right to food” and “international trade” involve a tricky balance, which will be challenging in regions where imports and exports have been a legacy and a necessity.

In summary, upholding the basic right to food, a central tenant of the food sovereignty movement, provides promise for regions of the world whose food systems have paradoxically been full of abundance and scarcity.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

Funding for this project Developing Food Sovereignty Indicators to Promulgate Food Security and Food Sovereignty was provided by the Blum Center, at University of California-Merced.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author expresses appreciation to Mr. Jacob Morgan for his role as a research assistant, as well as two authors and the editor whose insightful comments improved the quality of the manuscript.

Footnotes

1. ^Ruckstuhl et al. (2008), Wells et al. (2020), and others (Kuusela, 1992) describe the boreal ecosystem as the world's second largest biome, containing roughly one third of the world's forest cover. It is characterized by rich biodiversity, expansive roadless areas, and low intensity settlement peripheral from market centers. Brandt (2009) states that the boreal biome is comprised of 627 million hectares (ha), or 29% of the North American continent north of Mexico.

2. ^Nunatsiavut Government (2021). Available online at: https://www.nunatsiavut.com.

3. ^The Mi'kmaq First Nations have inhabited eastern Canada for centuries, including what is now Newfoundland and Labrador. Many “born and bred” Newfoundlanders are reconciling their settler heritage with a newly discovered Mi'kmaq identity that had been assimilated by colonialism (Manning, 2018).

4. ^Food security defined as “a situation that exists when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life” [World Food Summit, 1996, quoted in Binimelis et al. (2014), p. 325].

References

Agriculture Agri-Food Canada (2019). Food Policy for Canada: Everyone at the Table. Available online at: https://multimedia.agr.gc.ca/pack/pdf/fpc_20190614-en.pdf (accessed April 18, 2021).

Binimelis, R., Rivera-Ferre, M. G., Tendero, G., Badal, M., Heras, M., Gamboa, G., et al. (2014). Adapting established instruments to build useful food sovereignty indicators. Dev. Stud. Res. Open Access J. 1, 324–339. doi: 10.1080/21665095.2014.973527

Brandt, J. P. (2009). The extent of the North American boreal zone. Environ. Rev. 17, 101–161. doi: 10.1139/A09-004

Burnett, K., and Murphy, S. (2014). What place for international trade in food sovereignty? J. Rural Stud. 41, 1065–1084. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2013.876995

Cadigan, S. (1992). The staple model reconsidered: the case of agricultural policy in northeast Newfoundland, 1785-1855. Acadiensis. 21, 48–71.

Claeys, P., and Edelman, M. (2020). The United Nations declaration on the rights of peasants and other people working in rural areas. J. Peasant Stud. 47, 1–68. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2019.1672665

Coletta, A. (2020, October 26). Indigenous people in Nova Scotia exercised their right to catch lobster. Now they're under attack. Washington Post. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/canada-nova-scotia-indigenous-lobster-fishery/2020/10/24/d7e83f54-12ed-11eb-82af-864652063d61_story.html (accessed October 26, 2020).

Cordeiro, M., Rotz, A., Kroebel, R., Beauchemin, K. A., Hunt, D., Bittman, S., et al. (2019). Prospects of forage production in northern regions under climate and land-use changes: a case-study of a dairy farm in Newfoundland, Canada. Agronomy 9:31. doi: 10.3390/agronomy9010031

Coté, C. (2016). Indigenizing food sovereignty. Revitalizing indigenous food practices and ecological knowledges in Canada and the United States. Humanities 5:57. doi: 10.3390/h5030057

Council of Canadian Academies (2014). Aboriginal Food Security in Northern Canada: An Assessment of the State of Knowledge. Ottawa, ON: Expert Panel on the State of Knowledge of Food Security in Northern Canada, Council of Canadian Academies. Available online at: https://cca-reports.ca/reports/aboriginal-food-security-in-northern-canada-an-assessment-of-the-state-of-knowledge/ (accessed April 18, 2021).

Desmarais, A. A. (2008). The power of peasants: reflections on the meanings of La Vía Campesina. J. Rural Stud. 24, 138–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2007.12.002

Edelman, M. (2014). Food sovereignty: forgotten genealogies and future regulatory challenges. J. Peasant Stud. 41, 959–978. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2013.876998

Egeland, G. M., Johnson-Down, L., Cao, Z. R., Sheikh, N., and Weiler, H. (2011). Food insecurity and nutrition transition combine to affect nutrient intakes in Canadian Arctic communities. J. Nutr. 141, 1746–1753. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.139006

European Union (2010). Commission Regulation (EU) No 737/2010 of 10 August 2010 Laying Down Detailed Rules for the Implementation of REGULATION (EC) No 1007/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Trade in Seal Products. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2010:216:0001:0010:EN:PDF (accessed April 18, 2021).

Finger, M., and Heininen, L. (Eds.). (2019). The GlobalArctic Handbook. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-91995-9

Godfray, H. C. J., Beddington, J. R., Crute, I. R., Haddad, L., Lawrence, D., Muir, J. F., et al. (2010). Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 327, 812–818. doi: 10.1126/science.1185383

Keske, C. (Ed.). (2018). Food Futures: Growing a Sustainable Food System for Newfoundland and Labrador. St. John's: ISER.

Keske, C., Godfrey, T., Hoag, D., and Abedin, J. (2020). Economic feasibility of biochar and agriculture coproduction from Canadian black spruce forest. Food Energy Secur. 9:e188. doi: 10.1002/fes3.188

King, M., Altdorff, D., Li, P., Galagedara, L., Holden, J., and Unc, A. (2018). Northward shift of the agricultural climate zone under 21st-century global climate change. Sci. Rep. 8:7904. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26321-8

Kuusela, K. (1992). The Boreal Forests: An Overview. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online at: http://www.fao.org/3/u6850e/u6850e03.htm (accessed April 18, 2021).

La Vía Campesina (2007). “Nyéléni declaration,” in Sélingué, Mali: World Forum on Food Sovereignty. Reorienting Local and Global Food Systems, Marcia Ishii-Eiteman (Vol. 235). Available online at: https://nyeleni.org/IMG/pdf/DeclNyeleni-en.pdf (accessed April 18, 2021).

Low, C. (1967). The Founding of the Co-operatives. Toronto, ON: National Film Board of Canada. Available at: http://www.nfb.ca/film/founding_of_the_cooperatives/ (accessed April 18, 2021).

Manning, S. M. (2018). Contrasting colonisations:(Re) storying Newfoundland/Ktaqmkuk as place. Settler Colonial Stud. 8, 314–331. doi: 10.1080/2201473X.2017.1327010

McMichael, P. (2009). A food regime genealogy. J. Peasant Stud. 36, 139–169. doi: 10.1080/03066150902820354

Merrell, A. R. (2020). Evolving governance: a comparative case study explaining positive self-government outcomes for Nunatsiavut government and the Miawpukek First Nation (Doctoral dissertation). St. John's, NL: Memorial University of Newfoundland. Available at https://research.library.mun.ca/14567/1/thesis.pdf

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., and Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 339:b2535. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Mullowney, D. R., and Baker, K. D. (2020). Gone to shell: removal of a million tonnes of snow crab since cod moratorium in the Newfoundland and Labrador fishery. Fish. Res. 230:105680. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2020.105680

Omohundro, J. T. (1994). Rough Food: The Seasons of Subsistence in Northern Newfoundland. St. John's, NL: ISER.

O'Neill, K. (2018). Traditional beneficiaries: trade bans, exemptions, and morality embodied in diets. Agric. Hum. Values 35, 515–527. doi: 10.1007/s10460-017-9846-0

Ruckert, A., Huynh, C., and Labonté, R. (2018). Reducing health inequities: is universal basic income the way forward? J. Public Health 40:1, 3–7. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdx006

Ruckstuhl, K. E., Johnson, E. A., and Miyanishi, K. (2008). Introduction. The boreal forest and global change. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 363, 2245–2249. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2196

Skinner, K., Hanning, R. M., Desjardins, E., and Tsuji, L. J. (2013). Giving voice to food insecurity in a remote indigenous community in subarctic Ontario, Canada: traditional ways, ways to cope, ways forward. BMC Public Health. 13, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-427

Southcott, C., Abele, F, Natcher, D., and Parlee, B. (Eds.). (2018). Resources and Sustainable Development in the Arctic. Philadelphia: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781351019101

Tarasuk, V. (2017). Implications of a Basic Income Guarantee for Household Food Insecurity. Thunder Bay, ON: Canada: Northern Policy Institute. Available online at: https://yrfn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Implications-of-a-BIG-for-Household-Food-Insecurity_PROOF.pdf (accessed April 18, 2021).

Tedds, L. M., Crisan, D., and Petit, G. (2020). Basic Income in Canada: Principles and Design Features. SSRN. Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3781834 (accessed April 18, 2021).

Wells, J. V., Dawson, N., Culver, N., Reid, F. A., and Morgan Siegers, S. (2020). The state of conservation in North America's boreal forest: issues and opportunities. Front. Forests Glob. Change 3:90. doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2020.00090

Keywords: boreal ecosystem, food sovereignty, international trade, indigenous food systems, sustainable agriculture, Newfoundland and Labrador

Citation: Keske C (2021) Boreal Agriculture Cannot Be Sustainable Without Food Sovereignty. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5:673675. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2021.673675

Received: 28 February 2021; Accepted: 06 April 2021;

Published: 30 April 2021.

Edited by:

Adrian Unc, Memorial University of Newfoundland, CanadaReviewed by:

Meaghan Wilton, University of Toronto Scarborough, CanadaCharles Z. Levkoe, Lakehead University, Canada

Copyright © 2021 Keske. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Catherine Keske, Y2tlc2tlQHVjbWVyY2VkLmVkdQ==

Catherine Keske

Catherine Keske