- 1Greater Good Science Center, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, United States

- 2Department of Communication Studies, San Francisco State University, San Francisco, CA, United States

- 3Institute for Holistic Health Studies, San Francisco State University, San Francisco, CA, United States

- 4Pacifica Graduate Institute, Carpinteria, CA, United States

- 5San Francisco School of Nursing, University of California, San Francisco, CA, United States

- 6Stanford OBGYN, Winn Lab, Palo Alto, CA, United States

- 7Clinically Applied Affective Neuroscience Laboratory, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, United States

Contemplative science has made great strides in the empirical investigation of meditation practices, such as how mindfulness, compassion, and mantra practices impact health and well-being. However, meditation practices from the Vajrayana Buddhist tradition that use mental imagery to transform distressing beliefs and emotions have been little explored. We examined the “Feeding Your Demons” meditation, a secular adaptation of the traditional Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhist meditation practice of Chöd (“Severance”) in a pilot, randomized controlled trial in which 61 community adults from the U.S. with prior meditation experience and moderate levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms (70% female)were randomly assigned to one month (15 meditation sessions) of “Feeding Your Demons” practice or a waitlist control group. Written diary entries were collected immediately after each meditation session. We used an Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis approach to examine qualitative responses to two questions which probed (1) how participants made meaning of each meditation session and (2) how they thought it may impact their future thoughts and intentions for action. Five major themes were identified based on 20 codes developed through an inductive review of written responses across all participants. The themes included an enhanced sense of self-worth and confidence, empathy for the “demon” or rejected parts of oneself, increased self-awareness, an active-oriented “fierce” self-compassion, and an acceptance form of self-compassion. Overall, participants expressed an ability to reframe, or transform, their relationship to distressing thoughts, emotions, and experiences as they gained personal insights, self-compassion, and acceptance through the meditation process which in turn shaped their future intentions for action in the world. This research suggests that a secular form of a Vajrayana Buddhist practice may be beneficial for Western meditation practitioners with no prior training in Vajrayana Buddhism. Future research is warranted to understand its longer-term impacts on health and well-being.

Introduction

“Clouds in vast sky, Our demons are dakinis In the expanse of mind.”(Greer Dickson, 2021)

One of the most powerful psychological skills that humans can cultivate is the ability to transform adversity into meaningful insight and personal growth. This type of mental training is at the core of the Buddhist contemplative tradition through many types of meditation practices from various Buddhist lineages. In the modern world, Buddhist-derived interventions (BDIs), such as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and Cognitively Based Compassion Training, instruct individuals in a variety of mindfulness and compassion practices (Fredrickson et al., 2008; Goyal et al., 2014; Gu et al., 2015). These BDIs have been shown to reduce stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms, improve emotional resilience, increase compassion and pro-social behavior, and promote overall health (Eberth and Sedlmeier, 2012; Jazaieri et al., 2013). Yet, there is a paucity of research on meditation techniques derived from the Vajrayana Buddhist tradition from Tibet (Wilson-Mendenhall et al., 2019, 2022). Vajrayana practices integrate a variety of techniques in addition to mindfulness, including active imagery, mantra, ritual, music, yogic postures and movements, breathing exercises, cultivation of altruistic intentions, and resting in non-dual awareness (Wallace and Shapiro 2006). These practices, conducted under the guidance of an authorized instructor, aim to increase meta-awareness and undo experiential fusion with constraining or (Greer Dickson, 2019) invalid concepts of self in order to arrive at a non-dual state of awareness. The cognitive structures of distorted views of self/other considered the root of suffering in Buddhist philosophy, collapse in this state, and experiential knowledge of the nature of consciousness itself arises (Dahl et al., 2015; Schlosser et al., 2022).

In this paper, we explore an adaptation of one specific Vajrayana practice accessible to non-Buddhists and its ability to enhance wellbeing through the reappraisal and transformation of distressing experiences into greater acceptance, compassion, and meaningful insight. Feeding Your Demons (FYD) is a secular, imagery-based contemplative process developed by Buddhist teacher Lama Tsultrim Allione that draws from the Chöd practice of Vajrayana Buddhism and combines it with Depth and Gestalt psychology (Allione, 2008; Jung, 1970). FYD shares many elements with traditional Vajrayana practices including active imagery, embodiment of and interaction with imaginal figures, cultivation of compassion, and resting in awareness.

In the sections that follow, we present an overview of literature related to the development of the FYD practice, including its historical origins in 11th-century Tibet and contemporary scientific literature on meditation.

Traditional origins of FYD

The Vajrayana Buddhist practice of Chöd (Tibetan term which means “to sever”) was established by the 11th-century meditation master Machig Labdrön, one of the most renowned female teachers in Tibetan history (Allione, 2008). Understanding the core principle of selfless offering in Chöd is helpful to understand how FYD came about as a derivation of the original practice. In the Chöd practice, the meditator imagines consciousness moving out through the crown of the head, and becoming the deity Tröma Nagmo, the fierce blue-black ḍākinī, Sanskrit for “sky-traveler” which refers to a class of female deities who represent primordial wisdom. As Tröma Nagmo, the meditator imagines transforming her corpse into nectar and offering it to all sentient beings, satisfying their desires, purifying their illnesses and negativity, and guiding all to liberation.

The core aspect of the Chöd practice requires the practitioner to cultivate generosity through the imagined offering of that which we hold most dear, our own body. Allione adapted the main elements of Chöd practice into a more accessible and secular contemplative process (Sauer-Zavala et al., 2013).

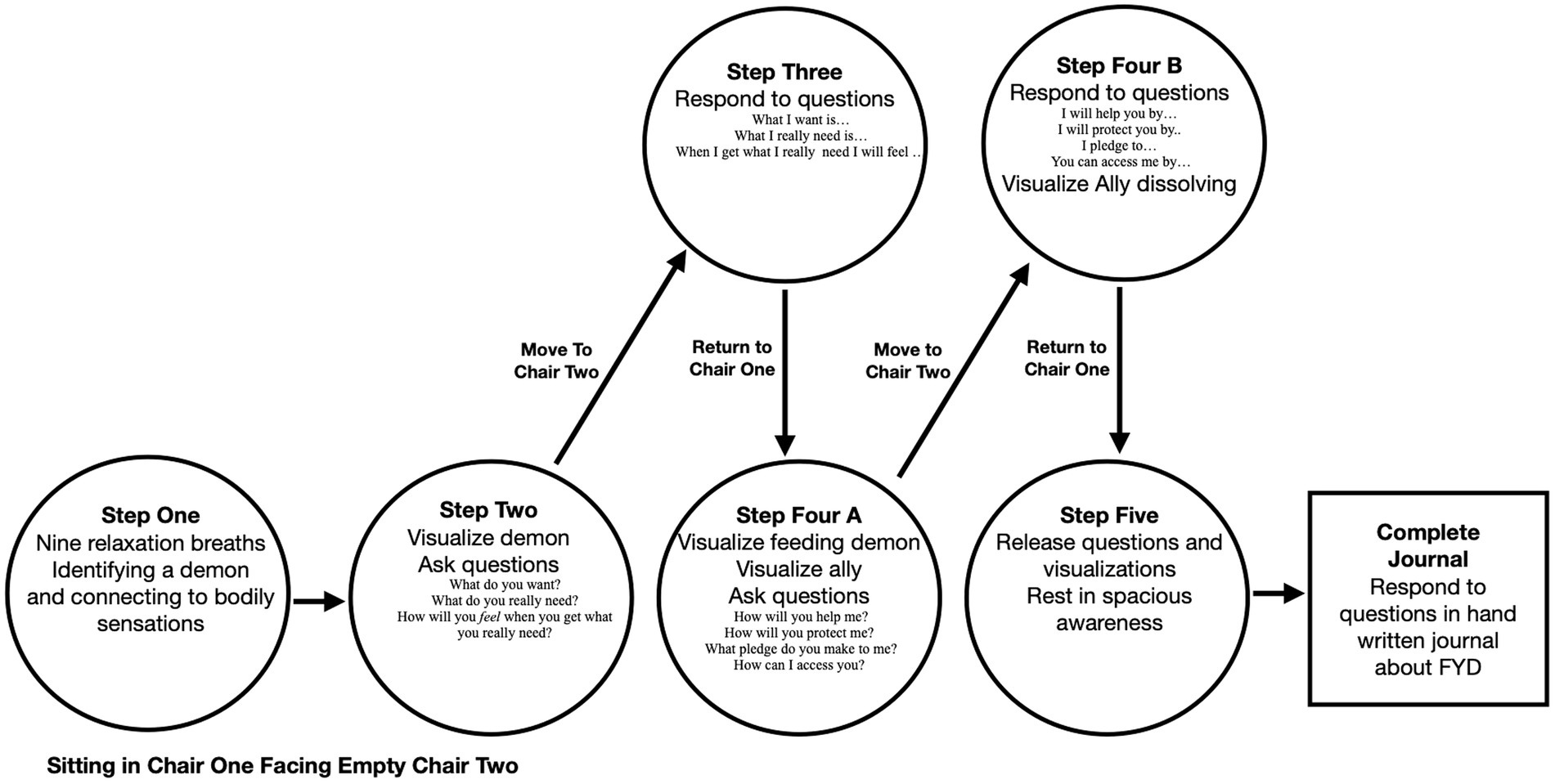

FYD is a structured and manualized five-part practice guided by a certified FYD teacher. The process involves personifying and dialoguing with bodily, cognitive, and emotional states of mind, and nourishing, rather than avoiding or suppressing, thoughts and feelings which are perceived as aversive. FYD is practiced using two chairs set up facing each other. A pracitioner moves between these chairs as she engages in different phases of imagery, inquiry, perspective-taking, and reappraisal. In this context, the nominal “demon” refers to emotions, thoughts, and physical sensations that cause distress and hinder an experience of liberation. Here, liberation is the relief from, or reduction of, distressing states of mind and emotions. FYD involves five distinct steps; the first four steps entail embodied self-reflection, imagery, perspective-taking, and dialoguing with distinct aspects of the self. The fifth step cultivates a non-dual mental state. A brief summary of the steps is provided here, a full description of the FYD steps is provided in the Methods section below and in Figure 1.

In step one, the guidance is to connect with the nine relaxation breaths and identify a demon and connect to bodily sensations. In step two visualize the demon and ask the following questions: What do you want? What do you really need? How will you feel when you get what you really need? In step three move chairs, continue to visualize the demon, and respond to these questions: What I want is… What I really need is …When I get what I want, I will feel … In step four A again move chairs and visualize feeding the demon to completion and then visualize the ally and ask these questions: How will you help me? How will you protect me? What pledge do you make to me? How can I access you? In step four B once again move chairs, and continue to visualize all and respond to the questions: I will you help by … I will you protect by … I pledge to… You can access me by… In step five again move chairs, release questions and visualizations, and rest in spacious awareness. Following step five respond to questions in hand written meditation diary about FYD.

Psychological mechanisms of meditation

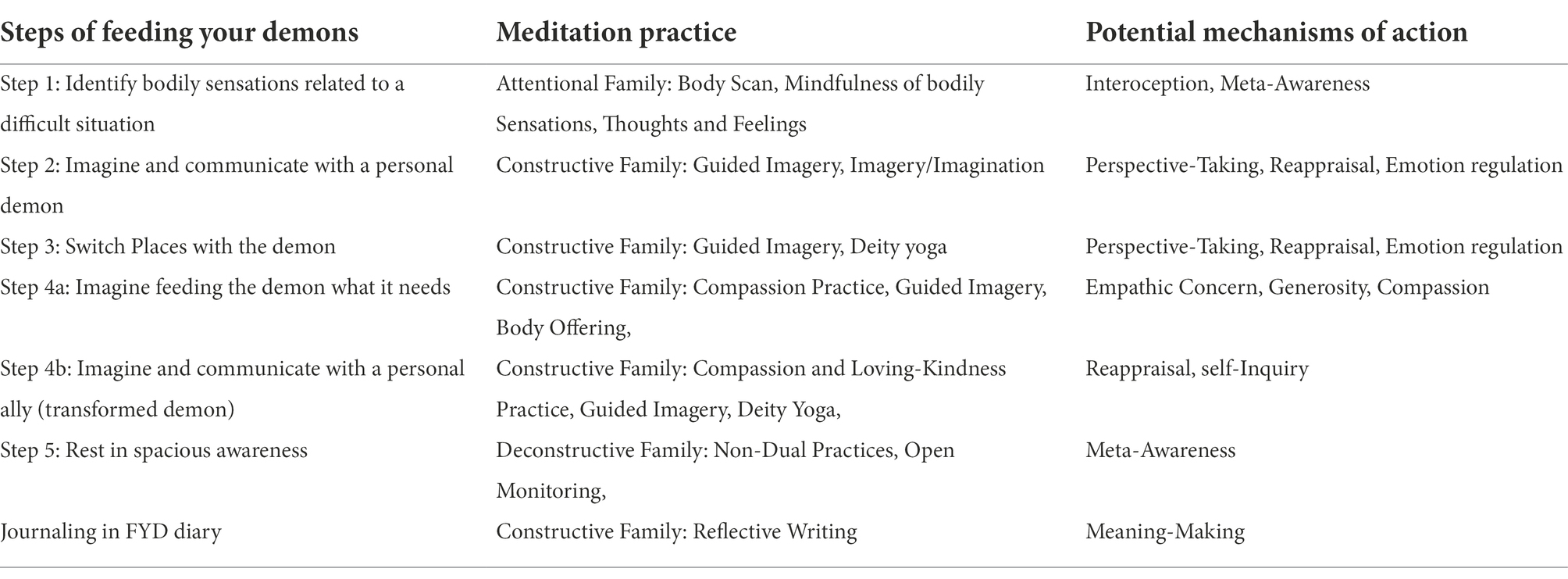

To better understand the distinct components of the FYD meditation process, we refer to a cognitive mechanisms framework of meditation practices proposed by Dahl and colleagues (Dahl et al., 2015). Their approach is based on cognitive and clinical scientific evidence that supports the classification of specific meditation practices (or techniques) into attentional, constructive, and deconstructive families. These three families of meditation practices are based on engagement with distinct psychological processes: (1) attention regulation and meta-awareness, (2) perspective-taking and reappraisal, and (3) self-inquiry. This framework suggests that the functional distinctions of each of the three families can be understood by their effects on three cognitive mechanisms associated with psychological inflexibility and mental distress: experiential fusion, maladaptive self-schema, and cognitive reification.

Before describing how the three families suggested by Dahl and colleagues relate to the steps of the FYD practice, we will define the mechanisms and examples of these practices here briefly. The attentional family addresses the process of attention regulation through meta-awareness including such practices as concentration and mindfulness-based practices (Dahl et al., 2015; Schlosser et al., 2022). Meta-awareness is awareness of what we are conscious of whether that is thinking, feeling, or perceiving, or as in non-dual states, awareness itself (Dahl et al., 2015). Strengthening meta-awareness increases the capacity to become aware of what is in awareness without being fully merged with it, for example, noticing thoughts, memories, and images but not being fully identified or experientially fused with them (Smallwood et al., 2007). Meta-awareness facilitates attention regulation and occurs during mindfulness practice the instant one become’s aware of being distracted, for example thinking about a past conversation instead of focusing attention on the sensation of breath at the nostrils, one then directs attention back to the breath. The constructive family of meditation practices develop perspective-taking and cognitive reappraisal and include forms of meditation which imagine and extend feelings of care such as practices of the “four immeasurables” as found in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition: loving-kindness, compassion, empathetic joy, and equanimity. Perspective-taking involves imagining the thoughts and feelings of others, while cognitive reappraisal formulates a new way of relating to or interpreting one’s own thoughts, feelings, contexts, and behaviors (Dahl et al., 2015; Schlosser et al., 2022). For example, cognitive reappraisal in a practice of compassion may involve shifting our mindset from a feeling of disheartenment to resilience by re-interpreting the meaning of a specific content and context. The deconstructive family of practices use self-inquiry to cultivate insights about interdependence and the changing nature of the phenomenal world, including ourselves. The practices in this family include analytical practices that investigate experience and consciousness and non-dual practices which can point to a direct experience of consciousness. Deconstructive practices interrogate beliefs and ideas about the self and the world which may usually be implicit and beneath the surface of our day-to-day consciousness. In Table 1, we outline each step of FYD and the related meditation practices, and potential mechanisms of action.

Examining mechanisms step one

The very first part of step one is engaging in what are called the nine relaxation breaths which use the breath to connect with bodily sensations; this is akin to a brief body scan, next the practitioner directs attention to bodily feelings associated with a personally salient or challenging situation. This first step addresses how the meditation practitioner is typically experientially “fused” or identified with the contents of the mind. The practitioner is guided to intentionally redirect attention to bodily sensations associated with thoughts and emotions related to the chosen situation. The act of observing sensations provides a basis for cultivating meta-awareness of when we become caught up in those thoughts and feelings (e.g., cognitive fusion with thoughts, memories, images, and sensations; Smallwood et al., 2007). The practices used in this first stage of FYD includes connecting with breath, and sensations in the body associated with a difficult experience, this difficult experience will be used as the demon through the five steps of the practice. This is similar, but not the same, as body scan and the mindful awareness of body sensations, thoughts, and feelings, as they shift and change which are included in Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction training (Khoury et al., 2015).

The process of sensing the physiological condition of the body is known as interoceptive awareness, which also involves incorporating sensations into higher-order cognitive functions, such as appraisal, emotion, and decision-making processes (e.g., Mehling et al., 2012; Farb et al., 2015; Khalsa et al., 2018; Daubenmier etr al., 2013). Mindfulness practices such as body scan practice and bringing close attention to breath are thought to increase the accuracy of interoceptive processes that enhance emotional awareness and emotion regulation (e.g., Farb et al., 2015; Fischer et al., 2017). A meta-analysis and recent review of the neurological mechanisms of mindfulness meditation found reliable activation of the insula, which processes interoceptive information, suggesting that enhancement of bodily awareness is a key mechanism of mindfulness meditation (Falcone and Jerram, 2018; Young et al., 2018). FYD includes a unique approach to bodily awareness starting with step 1, but also apparent through each step, as will be explained below, through its integration of emotional awareness and imagination-based practices.

Examining mechanisms steps two through four

As we see in Table 1, steps 2–4 of the FYD process can be classified as constructive contemplative processes that actively engage self-schemas to cultivate perspective-taking and reappraisal. Specifically, the practitioner allows the challenging situation-related bodily sensations to arise as a mental image of a demon in the space directly in front of the practitioner, to verbally interact with the demon, physically reposition oneself to take the demon’s perspective, then feed or nourish it such that it transforms into a mental image of an ally who provides support and encouragement and subsequently dissolves back into the practitioner. These mental images of demon and ally are the practitioner’s own creative and spontaneous mental projections of self-schemas.

Steps 2–4 entail intentionally and systematically altering thoughts and emotions via imagery, perspective-taking, and cognitive reappraisal. These steps share some resemblance to Loving-Kindness Meditation (LKM), compassion meditation, and guided imagery. LKM often includes the use of words or phrases of kindness that are silently directed toward oneself and others. Compassion practices engage with imagination to recall images of oneself and other people in moments of suffering and send compassion using images and verbal phrases. LKM and compassion meditations have been extensively investigated as stand-alone practices. LKM was found to enhance psychological wellbeing and improve positive affect (Fredrickson et al., 2008; Zeng et al., 2015); compassion practices have also been shown to increase empathy and modify neural circuitry related to caring (Lutz et al., 2008; Klimecki et al., 2014). FYD uniquely directs compassion and loving-kindness toward one self while engaging in a dynamic dialog with one’s difficulties personified as “demons” or “allies,” rather than repeating a static set of phrases directed toward one’s conventional sense of self or other as in other LKM and compassion practices.

Guided imagery is considered a mind–body intervention with some resemblance to the FYD practice in its creative engagement of the imagination through the senses. Guided imagery is a modern practice created to alleviate psychological distress or reduce chronic pain. It uses audio guidance to generate imagined peaceful sensory experiences, which create stress-reducing calm scenes and situations for healing. In hospital-based settings, guided imagery of calm nature scenes has been used to treat symptoms of cancer and improve quality of life (Trakhtenberg, 2008). In contrast, imagery-based meditations used in Vajrayana Buddhism have a broader range of images infused with an understanding of emptiness (Śūnyatā in Sanskrit), the mental insight that validly realizes the absence of a mistaken view of phenomenon as permanent, isolated, and not dependent on other causes and conditions (Khyentse, 2007). In FYD practice, the demon and ally imageries are beyond the scope of traditional guided imagery, as the demon may even temporarily increase distress, although both include the use of imagination (Amihai and Kozhevnikov, 2014). In a study examining Vajrayana imagery-based meditation, researchers found that the process of imagining compassion was similar to a behavioral simulation of compassion in generating sensorimotor patterns in the brain that can lead to compassionate behavioral action (Wilson-Mendenhall et al., 2022). Thus, imagining oneself nourishing and satisfying the desires of another being may increase pro-social attitudes and compassionate behavior towards oneself and others in the non-imaginal, real world.

Examining mechanisms step five

The fifth and final step of the FYD meditation exemplifies the deconstructive family of contemplative practice. Specifically, the practitioner is guided to enter into a silent state of resting in openness without reifying a sense of self, in which non-dual experiences may arise. Dahl and colleagues use the term “open monitoring” to describe this practice which includes “awareness-oriented open monitoring,” a sustained recognition of the knowing quality of awareness itself, and “‘object-oriented open monitoring” which is awareness of thoughts, precepts, and sensations arising in awareness. Deconstructive practices can lead to “minimal phenomenal self.” This minimal phenomenal self emerges through deconstructive practices that reduce the dominance and intensity of cognitive-linguistic-sensory self-related processes which exist across various neural networks in the brain and contribute to maladaptive self-views such as self-criticism and negative ruminations (Dahl et al., 2015). Deconstructive non-dual practices aim to down-regulate and minimize cognitive activities that generate the self-view of an observer as separate from what is being observed (Lutz et al., 2008; Metzinger, 2010). In Buddhist traditions, non-dual practices are thought to scaffold insights into the nature of self-related views by helping to dissolve their primacy; instead of thinking negative thoughts are true, we may directly observe the insubstantial nature of thoughts themselves. Phenomenological research has explored the basis of this non-dual experience through the reports of participants whose felt experience of non-duality is more than a concept (Metzinger, 2010; Berkovich-Ohana et al., 2013). Non-dual practices can provide direct experiential insight into the ever-changing and interconnected nature of all living and non-living entities (Meling, 2022).

Immediately following the FYD practice is the use of a meditation diary which provides questions for structured reflection on what has occurred in each step in a meditation diary. This reflection happens after the guided meditation is complete and the meditation diary. This reflective process following the guided meditation is another interesting feature of the FYD practice, one which can also support the process of cognitive reappraisal. This reflective process following the guided meditation is another interesting feature of the FYD practice, one which can also support the process of reappraisal. As a stand-alone intervention, expressive writing through journaling about an emotional experience has been an intervention with demonstrated benefits for psychological wellbeing for three decades (Pennebaker, 2018). While not included explicitly in the model proposed by Dahl and colleagues, the process of personal meaning-making may also arise from self-inquiry, which are then consolidated in written reflections, which may, in turn, shift maladaptive self-schemas and facilitate coping with stressful events (Park, 2010; Martela and Steger, 2016).

Thus, the FYD meditation constitutes a complex sequence of practices that scaffold movement through meditation states associated with attentional, constructive, and deconstructive families within a single meditation session. Unlike other types of meditation practices associated with one of the three families of meditation classification proposed by Dahl and colleagues, the FYD process integrates features of attention regulation, emotion awareness, reappraisal, imagery, verbal interaction, and perspective-taking. However, these multifaceted and multidimensional types of meditation practice have not been extensively empirically studied in the context of cognitive and clinical science.

The current study

The current study is an analysis of a pilot, randomized waitlist-controlled trial examining the effects of the FYD meditation on psychological wellbeing (Goldin et al., in press). Results of the main study found that FYD practice over 1 month showed that compared to WL, FYD was associated with greater decreases in stress symptoms and increases in self-compassion among community practitioners with prior meditation experience. The goal of the current study is to explore qualitative, open-ended responses to two specific FYD meditation diary questions that probed how practitioners (1) made meaning of what occurred in each meditation session and (2) attempted to integrate insights into future intentions and actions in their everyday lives.

Materials and methods

Participants

We recruited a community sample of participants via Listservs, social media, and Buddhist meditation centers. Participants were required to have a minimum of 3 months of meditation experience and not have high levels of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms as assessed by the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale, a validated self-report tool (Lovibond and Lovibond, 1995). There were no other exclusion criteria. We were interested in FYD for participants who are regular meditators to see how this practice could be different from their usual practice. We defined regular practice as at least 3 times per week for 15 min per session. The DASS manual has cutoff scores to classify mild, moderate, and severe levels of symptoms of depression anxiety, and stress: mild 5–6; moderate 7–10 Anxiety: mild 4–5, moderate 6–7 Stress: mild 8–9, and moderate 10–12. We did not exclude people based on the DASS; participants reported a mild to moderate range of depression, anxiety, or stress symptoms; no one reported severe levels of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms.

From February to May 2018, 107 potential participants first provided informed consent and then completed an online screener to collect demographics and contact information. Potential participants were given a unique identification number to complete the quantitative measures of self-reported psychological functioning. The first 61 participants who completed the baseline assessments and met the inclusion criteria were then randomly assigned to either FYD (n = 30) or WL (n = 31) groups. Participants included 61 community adults (70% female, mean age = 44.05, SD = 11.20; 43.5% Caucasian, 39% Asian, 9.3% Hispanic, and 8.3% other). One participant dropped from FYD and one participant dropped from WL. There was no group difference, t(58) = 0.57, p = 0.57, 95% CI (−4.33, 2.46), in years of meditation experience between the FYD group, Mean = 7.56 years, SD = 5.73 (range: 0.25–18), and the WL group, Mean = 8.55 years, SD = 7.48 (range: 0.25–27).

Study design

In this randomized controlled study, qualitative data were collected via a structured meditation diary completed after each of up to 15 FYD meditation sessions completed during the 1 month of meditation practice. Quantitative data included validated self-report measures collected at baseline and after 1 month of the FYD meditation versus no training waitlist (WL) control groups. Participants were randomized into FYD meditation training and WL control groups with equal probability using a digital random number generator (random.org). After completing the waitlist control period, WL participants were offered the 1-month FYD meditation.

Procedure

After completing all baseline assessments, participants were randomly assigned to either FYD or WL. Participants completed the same self-report assessments again at post-FYD/WL. Participants received the FYD training at no cost. Participants who completed the post-WL assessments were offered FYD and were given diaries to use with the study. All participants provided informed consent prior to completing the online screener in accordance with the Institutional Review Board at UC Davis.

FYD contemplative process

As explained above, Allione (2008) created the FYD practice as a simplified and secularized version of the traditional Tibetan Buddhist Chöd meditation. What follows is a specific description of the five sequential steps of the FYD process as it would be experienced by the meditator. In step one, while seated the practitioner chooses a challenging issue they are experiencing like anger, pain, cancer, addiction, or anxiety, which is identified in the FYD process as a “demon.” The practitioner locates associated sensations of the demon in the body, and notices the texture, temperature, and color of the sensations. In step two, the practitioner allows the sensations to be personified visually as the demon and notices the demon’s color, size, character, eyes, emotional state, gender (if it has one), and other characteristics. The practitioner then asks the demon three questions: “What do you want? What do you really need? How will you feel when you get what you really need?” In step three, the meditator switches seats to the empty chair in front, inhabits the demon’s body, notices how their original self looks from the demon’s point of view, and answers the three questions from the perspective of the demon.

The fourth step of FYD actually has several components. Initially, the practitioner returns to the original chair, views the demon, and feeds it by mentally (a) creating an infinite amount of nectar that has the quality of the answer to the third question, “How will you feel when you get what you really need?,” or (b) dissolving the body and transforming it into the nectar that has the quality of feeding the demon what it would have when it gets what it really needs. This second option is more in line with the ancient Buddhist practice that FYD is based on. When the demon is satiated with the nectar, it transforms into the practitioner’s ally, a profound helper. The practitioner takes note of the color, size, character, eyes, and gender (if it has one), and asks, “How will you help me? How will you protect me? What pledge do you make to me? How can I access you?” Once again, the practitioner stands, switches chairs, becomes the ally, and answers the questions speaking as the ally, noticing how their normal self looks to the ally. When done answering, the meditator returns to the original chair.

In step five, the meditator initially receives the energy of the ally, and then the ally dissolves into the meditator. Once she has completely integrated the energy of the ally in their body, the meditator can choose either to rest in awareness or to visualize herself not identifying with any construct or visualization and then resting the mind in the space that follows. In both cases, the practitioner enters a state of mental spaciousness, described as resting in awareness of the present moment without projection, elaboration, or amplification. Following this final step, the meditator is cued to return to her body, taking particular note of any changes she feels in her body from before her FYD session. Having completed the practice, the meditator then fills out her meditation diary which invites a phenomenological recounting of the FYD process, for example asking about the color, shape, texture, and gender of the demon and ally and the words and phrases spoken by the demon and ally. In our study, we added two additional questions to the meditation diary inviting reflection on the overall experience of the FYD process and what might be learned from this. These additional questions invite the practitioner to re-integrate the new information from her FYD session on both an embodied and cognitive level.

FYD instruction and guidance

Lopön Chandra Easton was the primary meditation teacher in this study. She has completed an average of three meditation retreats per year since 1992, and has been a meditation teacher since 2001. She has taught FYD since 2010, after being trained and certified to teach FYD by Allione. Each of the four certified FYD facilitators had to complete at least 108 FYD sessions as part of their teacher training with Allione and Easton. Easton conducted an initial 2-h FYD orientation for all study participants and FYD facilitators, and also supervised each of the FYD facilitators during the study. To support the FYD practice, each participant was provided audio, video, and text-based instructions, the FYD book by Lama Tsultrim Allione, and three one-on-one FYD sessions with a single FYD facilitator.

Participants were asked to complete 15 sessions of FYD within 30 days. We gave each participant a paper diary to complete after each of the 15 FYD sessions. The diary asked participants to respond to questions about the FYD process and their understanding of the experience (see below in Measures).

Measures

This study focused on participants’ qualitative diary, which we used as the primary data, collected after each FYD meditation session. The diary entries included a total of 13 questions aimed to prime the participant to reflect on their experience immediately before and after each ~30 min meditation session; these questions were drawn from the standard reporting form of FYD which is used following the guided meditation of FYD. We adopted an Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (reference) approach for our content analysis of responses to two specific questions presented in the FYD meditation diary:

1. How do you make sense of this (e.g., the FYD meditation) experience? What was new? What was familiar?

2. What, if anything, would you like to carry forward into your life from this (FYD) session?

We chose responses to these two questions because they probe current insights and reflection on future integration of FYD meditation experiences. The decision to ask participants to complete a paper meditation diary to fill out was explicit. The research team wanted participants to have an intimate experience with writing, as is done in the standard teaching of the FYD meditation technique. Our hope was that this format would encourage a more faithful experience of personal processing of the meditation and encourage participants to feel more free and willing to share their experiences candidly.

Following completion of the study, participants returned their diaries to the meditation center or mailed the diaries to the research team for data entry. A team of transcribers manually entered the de-identified diaries to a secure online form that created an excel format for the data analysis. Missing entries were noted by transcribers, illegible words were noted, and additional notes were shared in the online form. Out of a total of 59 possible diaries, we found that 45 (75%) participants completed 10 or more FYD sessions, with 38 (63%) completing all 15 sessions within 30-days. The text from the diaries was each manually uploaded to Dedoose data management software (Dedoose Version 8.0.35, 2018) to conduct Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis-informed content analysis, iteratively develop codes from the data, and fashion themes from these codes and source diaries.

Data analysis

Using a standard reporting form as a meditation diary is a standard part of the FYD process, but as mentioned above, we focused our analysis on two additional questions added to the end of the diary that ask participants how they make sense of and carry forward insights from their session.

The structured diary questions were analyzed using an Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) informed approach to coding (Shinebourne, 2011; Wright-St Clair, 2014). IPA is commonly used for semi-structured interviews and diary-based studies. Our approach is IPA-informed, the format of the diaries is not conducted in the traditional IPA long form narrative interview or diary but is captured over many time points. IPA’s inductive, interpretive analysis fits our analysis goals through its emphasis on the participant’s perception of an event instead of an objective or purely phenomenological recounting of an event. The participants’ description is the driver for creating a theoretical understanding of IPA. Close examination of the participants’ reflection on how they make sense of their experience allows insight into what can be the intangible and at times the ineffable process of FYD. The phenomenological descriptions of demons and allies were not included in this study in order to focus more specifically upon the participant’s reflective process of meeting and dialoguing with complex emotional material. IPA seeks the essence, “the intuitive structure of meaning,” that can be built from individual descriptions of their experience (Creswell et al., 2007). IPA is particularly well suited to exploring how a participant makes sense of non-ordinary states of consciousness and transformation, and has been used in the analysis of participant experience of psychedelics (Agin-Liebes et al., 2021).

We used a typical case sampling technique, a type of purposeful sample that emphasizes cases that are not unusual, atypical, or extreme (Patton, 2001) by selecting five (out of a possible 15) responses per participant focusing on the two final questions from the meditation diary. The analysis of these responses was primarily driven by an IPA-informed conventional qualitative content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005), in which codes are inductively derived from the data. We applied an IPA approach when reflecting on and synthesizing the individual inductively derived themes into larger themes with an intention to use participant-driven descriptions of the meaning and value of their emotional experience to capture what is called in IPA literature the essence of the experience (Pope and Mays, 1995; Vaismoradi et al., 2013). The qualitative team (EE, CJK) used an iterative coding process with transcripts within Dedoose data management software (Dedoose Version 8.0.35, 2018). First, we developed an initial codebook based on an inductive review of ten transcripts each. We discussed our initial codes, combined them when appropriate, and retained unique codes. Following the initial phase of codebook development, we generated approximately 20 codes in total. Next, these authors divided the remaining participants and reviewed five random entries from participants who completed at least 10 diaries across the 30 days. We applied initial codes separately and generated new inductive codes when needed to capture the meaning of the meditation experiences in the data. This is a high number of participants and responses for IPA-influenced analysis; however, the responses were short and averaged from one to four clauses per entry. The coding team met regularly to discuss code application, code continuity, new inductive codes, collapsing/condensing redundant codes, and preliminary themes throughout the coding process.

Results

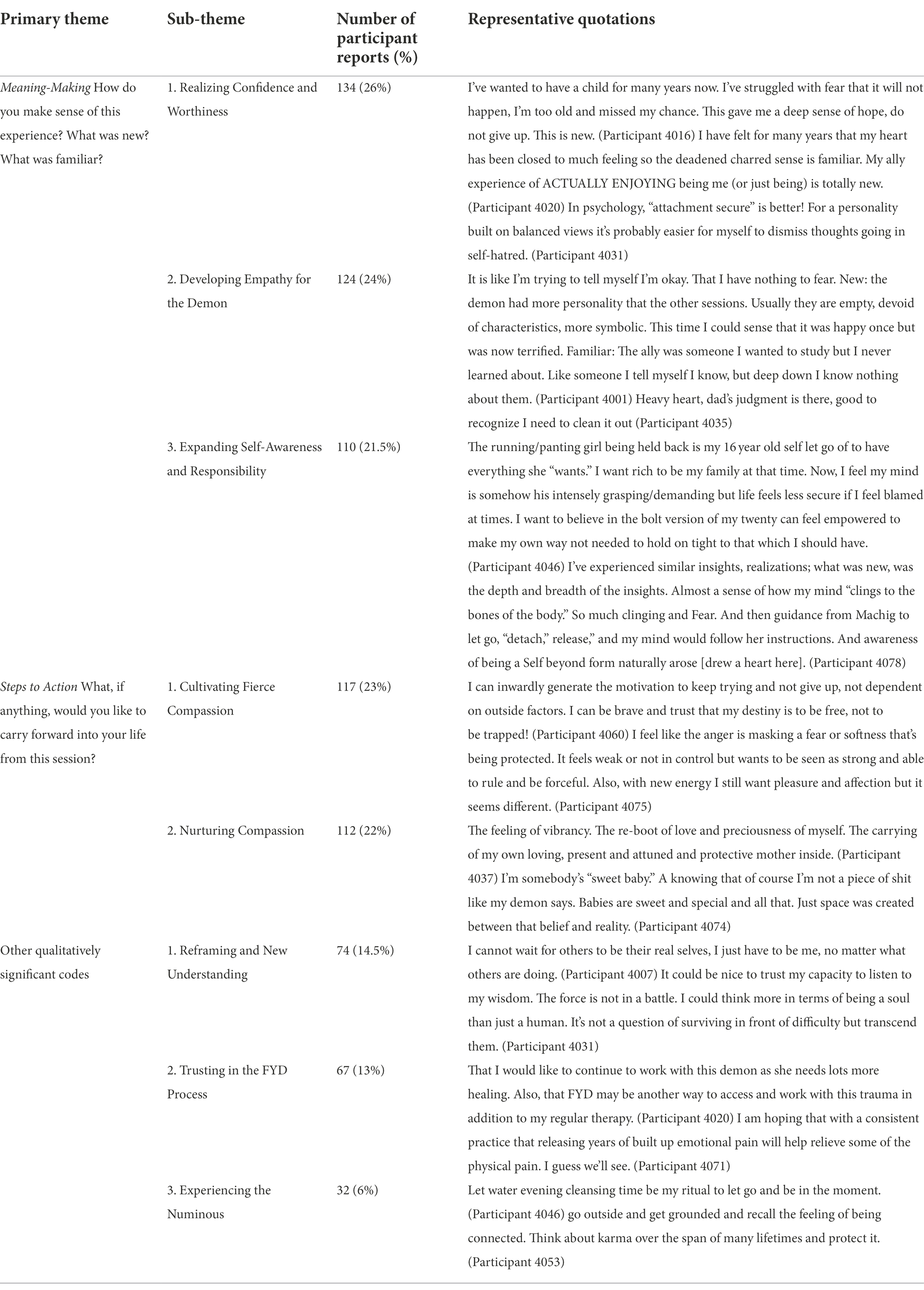

After the diary research team (EE, CJK) completed initial inductive coding and meta-level analysis of the diary entries we invited (KGD) a certified FYD facilitator and scholar to engage in an interpretive process. The IPA process generated three major thematic dimensions resulting in eight total thematic categories. Participant responses to the first question are described as Meaning-Making, and responses to the second question are described as Steps to Action. The additional thematic elements are described as other qualitatively significant dimensions. See Table 2. Primary Themes and Sub-Themes from Diary Entries.

Meaning-making: Putting the pieces together during the FYD meditation

In meaning-making, participants reflect on the experience they had and how to understand it in the context of this session, other sessions, and their life. The themes point to both self-understanding through connecting with confidence and worthiness, and an ability to turn toward and feel empathy and care with the difficult emotional material which arises in the FYD session.

Realizing Confidence and Worthiness (n = 134; 26% of diary entries)

The Confidence and Worthiness theme describes a common experience participants shared about an overall sense of validation. We built this larger theme from individual codes, including a feeling of strength being revealed, confidence in expression, an affirmation that my own experience is real and valuable, and recognizing my needs and desires as powerful. The thread connecting these codes is a growing self-evaluation of intrinsic value and capacity in participants’ lives more generally. As participants make sense of their FYD experience, they gain clarity about what they need, want, and feel empowered and/or deserving to have. Very often participants find what is needed is a loving presence. This is a quintessential learning of the entire FYD process. One participant reflected:

The little boy (that) the demon turned into reminded me of a happy and independent part of me that I am disconnected from. The nurturing woman actually came to check on him and admire his play happily. This I think is the part of me that is a caregiver to others but [the meditation helped me create the possibility] that I can also do the same for me (Participant 4010).

In this quotation, the participant emphasized that the transformation from demon to “little boy” ally helps them to recognize a part of themselves they feel they no longer have connection to in their everyday lives. The participant independently recognizes that every image is an intrinsic part of themselves, waiting to be discovered and mobilized to bolster internal confidence. For example, the recognizable “caregiver” checks in on the boy’s wellbeing and enjoys observing his happiness as a shared happiness. While the participant sees themselves in the caregiver, the meditation helps them to realize they can be their own caretaker, monitoring their own inner child’s safety and happiness. This affirms the participant’s sense that they have the intrinsic ability to caretake themselves and they can do so from the perspective of a benevolent caretaker, confident in their ability to nurture and worthy to benefit from loving attention.

One of the most common reflections in this theme was that participants were able to recognize an unwanted aspect of themselves that they did not previously see clearly and, as a result of recognizing that negation, expressed compassion for themselves. For example, one participant described an insight into their current state:

I get debilitated by seeking others’ approval and cannot speak up for myself or prioritize my needs for fear of losing that approval. I also see how ingrained this demon became when I was in an ongoing abusive relationship for 2 years as a teenager. It was new to feel the energy of belief and encouragement to move beyond—it’s hard for me to generate that from within. AND, I can! (Participant 4060).

This participant recognizes being “debilitated … and cannot speak up for myself and prioritize my needs” out of fear of others’ disapproval. The meditation helped to identify and acknowledge the core problem—seeking others’ approval in ways that serve to discourage their own voice. This characteristic was linked with the demon through an abusive relationship as a teenager that has calcified in their emotional lives. The process helped generate “energy of belief and encouragement” as an inner source of strength, validating their self-worth and confidence.

Participants similarly reflected that the demon and ally are both elements of one’s subconscious, and facing this duality can bring forth a sense that the hurt and the healing are both contained within. One participant described this dimension of worthiness as related to hedonic cravings coupled with moral judgment levied against themselves:

My victim demon is so dependent on outside indicators of care and really believes she is weak and perhaps undeserving of love, whereas the ally is inseparably connected with her strength and power and feels no need to make a show of that—just to use it to live. It was new to have confidence based on internal resources and not outside praise, and familiar to be desperate for care and concern from others (Participant 4060).

This reflection connects the “victim demon” that depends on external validation to counter the feelings of weakness and “perhaps undeserving of love.” By contrast, the ally “is inseparably connected with her strength and power” and has no need for external validation. For this participant, the demon and ally are two sides of the same coin, vying for existential validation, and both exist within the participant’s experience. The meditation process helped bolster confidence and reliance on “internal resources and not from outside praise.” Recognizing the demon’s emotional logic helps the participant generate a new self-confidence and regain a new sense of self-worth.

Developing empathy for the demon (n = 124; 24% of diary entries)

In making sense of the experience, Empathy for the Demon describes the participant’s experience of connecting to the demon with understanding and care. This theme synthesized the following individual codes: demon as a neglected part of the self, realizing the demon is something one can usefully work with, and realizing the demon wants recognition. The overall meaning of this theme is that through engaging with the FYD process, the participant first interacts with and subsequently comes to perceive the demon in a new way that is intrinsically associated with the participant’s own life experience. For example, creating a form for the demon can allow authentic communication and understanding between the participant and the demon, as the following quotation illustrates:

I’d connected with my inner child once or twice before and discovered similar themes, but I do not think I appreciated or examined the frightening, screechingly loud depth of it before. We’d never really TALKED like that and I’d never admitted before—to myself or anyone else—a truth I felt guilty for. She’s right, I’ve hid her and acted as though I hate her. (Participant 4061).

Despite prior experience having “connected with my inner child” this participant recognized instead of similar visual and emotional motifs. Participants reported demons showing up in their imagery as forgotten and under-attended aspects of themselves, particularly in the past. However, within the meditative frame, the “once or twice” experience roars it’s significance to the participant, as she does not “think I appreciated or examined the frightening, screechingly loud depth of it before.” This suggests a previously unknown emotional salience of her inner child and, potentially, her own actual childhood. The meditation process asks participants not only to visualize the demon but also to interact first by asking a set of standardized questions and then to listen to the (lack of) answers. This participant suggests that she and the demon “never really TALKED like that.” In this instance, interaction with the demon helps create a direct connection with the neglected aspects of herself that the demon represents. Through this interaction, she was able to admit “a truth I felt guilty for,” a truth that “I’ve hid her and acted as though I hate her.” Interacting with the demon led to realization of a truth buried in the participant’s memory and created a psychologically safe space to encounter this forgotten part of herself, ultimately, an act of compassion for the demon and, by extension, herself.

The Developing Empathy for the Demon theme emphasizes that interaction with the demon within the frame of the meditation enables an opportunity to develop empathy for the demon and, by extension, themselves. One participant described empathy for the demon in the following ways:

I try to keep my sorrow small and contained but it accumulates in the tightness of my body and my perspective (usually worried, discontent). It was new to sit with the depth of my sorrow. (Participant 4012).

In this description, the participant shifts from deliberately “keeping my sorrow small and contained” in the body to becoming present with the difficulty by “sitting with it” to experience the depth of the sorrow. Affirming the demon’s experience helps participants turn toward their own difficult emotions, such as worry, sorrow as described above, and despair. Participants describe that the meditation provided a technique to literally look challenging emotions “in the eye.” Throughout their responses, participants describe a willingness to be with, and even appreciate challenging emotions, as the following quotation suggests:

I often have head, neck, arm pain on my left side to the point of needing PT [Physical Therapy], so I found it interesting to see what inner experience it may be linked to. This demon feels very linked to my “inner child” who underwent trauma. I was in therapy talking about her earlier today, so not surprised she made an appearance. (Participant 4020).

This participant describes that persistent pain throughout her body requires routine Physical Therapy. In this reflection, she reports using the FYD meditation to explore what parts of her inner world might be related to her pain. The demon “feels very linked to my ‘inner child’ who underwent trauma,” suggesting an association between prior trauma and, for her, manifesting in a physical expression of pain. Other participants also describe their projected visual images of the demon related to current psychological therapy and other therapeutic modalities in which they engage, such as acupuncture, massage, and yoga, among others.

Developing Empathy for the Demon is facilitated by the FYD process, which includes generating both an image and dialog with these neglected, difficult parts of oneself. The meditation process facilitates empathy building as a three-part process. First, to acknowledge the presence of challenging emotions in their lives, which they frequently report dis-attending. Second, to feel how those challenging emotions affected and continue to affect them personally in their emotional, physical, and social lives. Finally, to validate those emotions, transforming them into realizations about themselves and validating the presence of those emotions as a part of themselves that can be fed and nourished.

Expanding self-awareness and responsibility (n = 110; 21.5% of diary entries)

Participants described insights and understandings about themselves and encouraged a desire to shift and grow. This theme came from the codes: current and past self play role in current problems, the mind can amplify negative emotions, perspective taking-putting myself in other shoes, and realizing one’s own actions are harmful to both self and others. Together, these codes express the ability for self-awareness, empathy for self and others, and the responsibility of reflection for personal transformation. Participants described how the meditation helped expand their self-awareness, particularly with challenging emotions, like fear, anger, and addictive craving. In the following reflection, this participant describes an increased knowledge of the role of fear in his behavior:

I am seeing that I am driven numb out of fear. What was new was how quickly I could participate in re-framing, redirecting my experience, and changing my (addictive) craving into understanding. What was familiar was the initial experience of “this will not work.” (Participant 4014).

Displaying a deeper awareness of the experience of difficult emotions, in this case fear and addictive craving, as well as an ability to work with the difficulty instead of shutting down. What is notable is the shift from “the initial experience of ‘this will not work’” to a deeper understanding between the relationships of fear and craving as it operates in his life. As a result of his meditation session, he felt that understanding transform from a perceived negative state, craving, into a sense of increased self-awareness, in this case, understanding. Other participants similarly expressed increased personal responsibility for challenging emotions, as the following quotation illustrates:

Age 12 is when I started blaming my weight and looks for everything that went wrong, self-hate began. New, she was resilient, did her best, familiar, sadness, her weight, wanting to eat more to be fed (Participant 4036).

Starting at an early age, this participant describes her self-perception at age 12—weight and looks “for everything that went wrong,” that generated the beginning of her narrative that “self-hate began.” After this meditation session, the participant saw a new side of herself, rooted in that distant time, but now transformed into a new woman “resilient, did her best, familiar…wanting to eat more to be fed.” Reflecting on the meditation experience helped her articulate the roots of self-hate and take responsibility for the resilience that helped her re-shape her established narrative.

Some of the most powerful experiences participants describe include realizations about themselves including areas of their emotional lives that are difficult to bring awareness, either because of trauma or other mental health issues that are difficult to process. For example, in the following excerpt, the participant describes a destructive pattern with their daughter:

I have been suppressing my guilt and sorrow around my daughter’s alcoholism and her anger and blame toward me. The newness was actually pinpointing a moment that symbolizes the dysfunction in our relationship (Participant 4083).

The participant describes feeling “guilt and sorrow around my daughter’s alcoholism” and the resulting challenging behavior the daughter expresses toward her, namely “anger and blame.” The process of FYD offers an opportunity to reflect on difficult experiences and consider one’s role in their interpersonal relationship. Specifically, the meditation session enabled “pinpointing a moment that symbolizes the dysfunction,” enabling the relationship a new possibility. Participants describe their sessions as manifesting feelings of empowerment by taking responsibility for their part in these relationships instead of self-blame or feeling victimized.

The theme of Expanding Self-Awareness and Responsibility highlights how participants are empowered to see and become aware of the limits they place on themselves in their emotional and social lives. In their reflections, participants suggest taking responsibility for the roles they do and do not play is significant to expanding self-awareness. Because the FYD meditation process encourages both a literal and a metaphorical projection of difficulty as the demon, the sensory details of projecting, feeding, and transforming the demon may play a role in how participants report expanding their self-awareness.

Steps to action: Applying the FYD meditation to everyday life

In the steps to action, participants consider how they will use what they experienced going forward in their daily lives. The themes of compassion are very strong, both compassion for one’s experience that is caring for things and people as they are and compassion which wants change and confrontation for one’s less helpful habits and ways of thinking. Out of the coded data segments, we created two themes to synthesize participant’s perspectives. We synthesized these under the title “Steps to Action” because in these two themes participants expressed how they intended to apply their FYD meditations to their everyday lives.

Cultivating fierce compassion (n = 117; 23% of diary entries)

The theme of Fierce Compassion described a number of different reflections that centered around awareness and strength. The codes included in this theme are: snap out of it, build defense mechanisms, build self-confidence and self-reliance, I need to challenge myself, and I recognize my own strength. Fierce compassion is defined as being both loving and action-oriented, often with the quality of cutting through what is no longer serving, sometimes with force. The codes out of which we synthesized Cultivating Fierce Compassion provided insight into how participants not only recognized, but actually put their own inner strength to use for personal transformation.

When discussing how they imagined using their inner strength, participants frequently described apparently intractable interpersonal and family and sometimes social difficulties they felt held them back in some way. For many participants, they described specific techniques for how they imagined using their inner strength as well as the possible consequences of their actions, as the following excerpt shows:

I want to break down my views of family and see where they are coming from so I can cultivate compassion and equanimity. I want this weight and burden to be gone and I want to slow down my world to make sure I do not create bad karma with vengeful words that hurt (Participant 4053).

The technique this participant expresses to “break down my views of family and see where they are coming from” is part of the process they see as a next step for them after the meditation ends. They describe working with family dynamics and history as part of “this weight and burden” they carry inside, and an integral part “to slow down my world.” Moving from the meditation experience to enact concrete action—“so I can cultivate compassion and equanimity” and “not create bad karma with vengeful words that hurt” how they envision applying the FYD lessons to their life. The participant describes a clear, caring, and forceful determination to not only accept what has happened in the past but to commit to changing it in the future.

While some participants point to seemingly intractable personal and social issues as the source inspiring transformation of emotional challenges, including addictive craving, other participants point to inner courage. Looking their demons directly in the eye without backing down requires courage, as the following excerpts illustrate:

Keep addressing this demon to get to the root as it seems to feed many aspects of my life and I have the sense of confrontation around this at every turn (Participant 4083).

I have not relayed my anger to the person I’m feeling it at because she is extremely delusional. I’m holding it in huge fists and fury of the demon. What I did not see is how hurt I am by her actions and how much I need to set boundaries of compassion and for myself. This relationship is for finding true wisdom in common—the wisdom is internal (Participant 4052).

The first participant points to dual persistence: the presence of the demon who he “sense(s) … confrontation around … every turn” and to the necessity of persistence to consistently face that demon in his life. The second participant describes the intensity of anger she feels through the demon who is “holding it in huge fists and fury.” However, when mustering courage to face that fury, she realizes “how hurt I am” by the other person’s actions. In fact, when staring down the demon, she realizes some possible solutions: “I need to set boundaries of compassion and for myself” of a valued personal relationship in which she might still “find true wisdom in common” with the other person. Setting compassionate boundaries is made possible for this participant by seeing clearly the repressed anger which manifested through the demon. Facing that demon creates an understanding of their own wisdom.

Overall, the theme Cultivating Fierce Compassion illustrates how participants create internal courage needed to “stare down” the demon sitting across from them. Looking their demons directly in the eye without backing down requires courage and persistence, which the meditation process helps them safely achieve. While creating internal resources out of thin air may seem impossible, participants describe meeting adversity where it finds them. Through their meditations, participants discover they are stronger and more resourceful than they initially imagined.

Nurturing compassion (n = 112; 22% of diary entries)

Compassion has many manifestations. As the prior theme suggests, one form compassion can take is the forceful energy of fierce compassion. However, participants also described a softer, more gentle form of compassion rooted in quiet acceptance and the embrace of vulnerability. We call this theme “Nurturing Compassion” because it is composed from the individual codes self-love and compassion, a renewed belief in self, vulnerability to others as strength. The thread connecting these codes is the vulnerable compassion grounded in self-affirmation, self-acceptance, and self-love. Together, these ideas combine to form a second form of compassion infused throughout the diaries and exemplified by the following participant’s reflection:

I can be happy on my own and love and care for myself without feeling so left out. I can include my different parts in my wholeness and let them nourish one another (Participant 4010).

As a result of the meditation session, this participant affirms their ability to “be happy on my own and love and care for myself” as an individual “without being left out” of normative social gatherings. This participant describes strong feelings of love directed toward the “wholeness” of oneself—this is done not by ‘getting rid’ of the demon, but “I can include my different parts in my wholeness and let them nourish one another. By including all the parts, this participant suggests an integrated view of self.

In their post-meditation reflections, participants often emphasized that they, themselves, were the source of nourishment, instead of an exterior source. For many participants, the source of feeling “cut off” from their own self-love from formative years of their childhood or young adulthood, as the following excerpt shows:

That I can generate those feelings of love and belonging myself. I can now know that I had these experiences as an infant, but I can repair them. And that I can access these positive emotions by looking into my heart to draw forth my love and strength. (Participant 4014).

The meditation session enables this participant the ability to “generate those feelings of love and belonging myself.” Traveling back in time to their infancy, they seem to be sending a message to their infant self that “I can now know that I had these experiences,” thereby affirming the fullness of nurturing experience, even one in the distant past. Visiting the past supports a feeling of confidence and strength in the present to heal past wounds is another aspect of nurturing compassion. Through the meditation process, they can hold the experiences of the past in a loving container in the present. This allows for the possibility of re-integrating past memories or trauma, as in memory reconsolidation.

Other participants described demons as embodying challenging people in their past or current lives. In these cases, Nurturing Compassion helped, at minimum, to lower negative affect toward these individuals and, at maximum, to begin an internal process of healing from social rifts. In the following excerpt, the participant’s meditation session generated the demon as a Father figure with whom the participant experienced abuse:

Felt as I was feeding my “father” that I was also feeding his father. Huge compassion came for my father as I felt the abuse from his father, also from feeling how hard it felt to be “him” and yet, so much love available, letting go of anger (Participant 4016).

During the feeding activity of the meditation, this participant expresses she was “feeding my ‘father’… I was feeding his father.” This cross-generational event generated “Huge compassion” because while feeding her father, “I felt the abuse from his father” and “feeling how hard it felt to be ‘him’.” The idea that this participant could generate compassion in a linked, cross-generational cycle of abuse points not only to a re-framing of the experience she had as an abused child, but to the need to nurture the wounded child that was once her father. Compassion for past hurt and abuse creates space for new understanding, insights, and letting go. Finding ways to release the emotional pain of past hurts is a critical area in FYD.

The theme Nurturing Compassion helps to coalesce the gentler side of compassion rooted in acceptance and self-love. Strikingly, many of the descriptions participants use to describe their experiences with this theme suggest challenging and traumatic events from their past and present. This suggests that rather than something that is “soft,” Nurturing Compassion is, in fact, itself a challenging activity to bring compassion and understanding to neglected aspects of the self that have experienced trauma, abuse, and exclusion sometimes from an early age. Overall, the theme of Nurturing Compassion helps balance with its more aggressive form to create a more balanced approach to taking action in participant’s personal lives as a result of the FYD meditations.

Other qualitatively significant dimensions

While the quantity of similar codes can be a good indicator for qualitative trends across a dataset, quantity alone is not necessarily the only way to gauge significance. Participants’ diaries included a smaller number of qualitatively significant ideas that, while fewer in number, were still meaningful to include because they offer insight into the range of experience participants describe during and after the FYD meditation experience. While these codes are insufficient to construct themes themselves, four qualitatively significant categories include Reframe, Trust in the Process, The Numinous, and reflections on the FYD Meditation Process itself.

Reframing and new understanding (n = 74; 14.5% of diary entries)

The FYD process creates a deliberate process for finding a new perspective to look at and reflect on painful or challenging experiences. The codes included in this theme are forgiveness to others, a shift in how I understand my problems, body as a source of wisdom, and being present with difficult emotions. The thread connecting these codes is that something present in participants’ everyday lives—their body, their emotions, their difficulties—are reframed. Rather than something intractable, physical, emotional, and interpersonal experiences are cast in a new light with new opportunities. In the following excerpt, the participant describes his capacity for self-reliance as something newly discovered:

It could be nice to trust my capacity to listen to my wisdom. The force is not in a battle. I could think more in terms of being a soul than just a human. It is not a question of surviving in front of difficulty but transcend[ing] them. (Participant 4030).

Reframing current challenges, he suggests the “force is not in a battle,” where the force is his way of describing his internal wisdom. Rather than a battle metaphor, he imagines it “more in terms of being a soul” with a life of its own with its own ability to “transcend” difficulties. This participant shares the simple wisdom of being able to look at one’s experience without aggression or denial and move beyond survival. Similarly, another participant describes how she wants to “adjust my mindset” in the following excerpt:

The soft openness of a cuddly new bear cub, I want to meet my life experiences with that, and to adjust my mindset that I have to avoid feeling weak or else I am weak, let that fear go knowing that fully embracing and allowing my feelings helps me to be strong. (Participant 4064).

She visualized the ally as the “soft openness of a cuddly new bear cub” as a new way to meet life experiences. Instead of having to “avoid feeling weak,” she reframes the idea of weakness as directly related to her fear “knowing that fully embracing and allowing my feelings helps me to be strong.” The insight and reframing often includes a willingness to be with emotions, to be open, this exemplifies a feeling of acceptance.

The theme Reframing and New Understanding illustrates the result of the process, a calm mind after the FYD meditation can be as transformative as the actual imagining process itself. Reflection on lessons learned and how those lessons can help inform one’s life is how the FYD meditation facilitates inner transformation.

Trust in the FYD process (n = 67; 13% of diary entries)

Participants described feeling supported by the process and encouraged to let the FYD work continue. The codes included in this theme are dedication to continuing the process, considering next steps, trust in the ally to guide us to help us. The thread connecting these codes is dedication to learning the FYD process as a salve for their wounded inner lives. Participants discussed persistence to practicing the meditation techniques, promising regular practice, as well as compassion for inner demons and healing from transformed allies. Many participants described their trust in the process with pithy aphorisms to help them remember general lessons learned from the meditation process, as the following excerpts show:

Being ok with myself when I feel like I do not have a plan or agenda, relaxing into the unknown, and know I am protected by my inner ally. (Participant 4010).

Being able to access the feeling of security I got when an ally seeks love, protection from me. (Participant 4049).

With calm, we see truths of life. (Participant 4031).

Many participants describe a sense of protection from the ally which can be used after the meditation session and in life provides participants with confidence and ease. Feelings generated from the ally themselves or as a result of the ally’s presence are frequently described. Many participants described trust in the FYD process through what they want to remember as a result of the meditation:

The light. Bright wisdom my ally. The understanding that I do not need to keep trying to get something, it can just be given if I step back and be still (Participant 4067).

Heart connection, remembering the words and advice from the ally. (Participant 4015).

One participant emphasizes “The light. Bright wisdom my ally,” while another participant emphasizes “Heart connection, remember the words and advice” as meaningful results of the meditation session. These participants describe feeling a sense of insight gained from the ally that can be taken with them into the rest of their life. Together, the codes and excerpts assembled to create the theme Trust in the FYD Process characterizes aspects of the meditation process and its result that participants find particularly meaningful to carry into their lives.

Experiencing the numinous (n = 32; 6% of diary entries)

Throughout the data, participants describe the FYD meditation as a source of ludic activity and the numinous, defined as the mysterious awe-inspiring mystery of being alive, generated as a result of the meditation process. Meditators recounted a range of beings, creatures, and objects taking various natural forms, including eagles, snakes, flowers, and crystals, as well as more imaginative forms, including angels, fluffy-feathered balls, and winged horses. The essence of these responses included the awe inspired by nature as a source of healing and the inspiration generated by wonder and play. The range of these responses included both natural and supernatural elements. Some meditators combined natural elements with their body or from their imagined body’s perspective:

How gorgeous I felt to be a swan. And how simple the transformation was once I recognized what I really need (Participant 4064).

View of the sea from a whale’s body had a vastness in quality (Participant 4030).

Adopting natural forms helped participants see new things about themselves and their situation, which was refreshed by association with actual animals they know, such as a swan and a whale, and perhaps even see in everyday life. Imagining oneself occupying the graceful body of a swan or a whale transforms one’s limited sense of self into something new. Other participants recounted imagined, supernatural beings:

How great it was to be the winged horse. How beautiful and bright and fun it was. The idea that all of that can be mine (Participant 4064).

How absurd it is to be jealous. That even being small and green does not make you unloveable. (Participant drew a smiley face to accompany this comment) (Participant 4072).

Participants imagined themselves magically transformed into figurative creatures symbolizing forms of being well beyond the confines of their usual everyday lives. Horses with sweeping wings helped participants imagine “all that can be mine” from the air and on the ground “being small and green” helped them imagine jealousy as a loveable absurdity. These playful images created new perspectives and opportunities to see everyday problems—the demons—in a new light by offering figurative opportunities for being out-of-the-ordinary as a result of the FYD meditation practice.

Participants also experienced nature as a source of healing and inspiration. Participants expressed their fears, desires, and insights as enacted by or facilitated through metaphors and similes of nature, the natural world, and its various processes. Through these images, participants compared their experiences of past limiting ideas, challenging emotions, and protective tools for healing, cleansing, and a new sense of being-in-the-world. For example, in the following quotations, participants relate their experiences during the FYD meditation as helping to facilitate healing processes they want to cultivate outside of the meditation:

The volcano breaking open is like my heart opening. I’d like to carry forward that remaining open, teachable, and compassionate [as] imperative to my recovery (Participant 4036).

Remember to use the protection tool I know, psychic, auric protection is key. Crystals are my tools and little helpers (Participant 4045).

For many participants, the natural world served as a model for transformation of the emotions through physical means. Invoking earth and fire, crystal, air, and water, participants expanded their awareness beyond their physical senses to envision their bodies intimately connected with natural processes and structures. These images suggest that participants’ mental and emotional health internally are directly supported by the natural, external environment present around them, literally or figuratively, suggesting an incipient ecopsychology (Vakoch and Castrillón, 2014) in which the multiple relationships between humans and the natural worlds are inextricably interrelated.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to examine the experience of the FYD meditation process using written diary responses to two specific questions: how participants understand and make meaning from their FYD meditation experience, and what insights participants might carry forward into their everyday lives. Participants answered these questions having just completed the FYD meditation, which makes them a particularly rich source for reflections on the meditation. Participants reported significant shifts in how they perceived their “demons” both during (Meaning-Making) and after (Steps to Action) the FYD meditation practice, transforming the relationship to their difficulties by reframing those challenging experiences in new, often unexpected ways. This process converges with the Dahl framework presented in the introduction as participants made their way through the steps engaging in attention regulation and meta-awareness, perspective-taking and reappraisal, and self-inquiry. Overall, the qualitative analysis explores the insights associated with the transformation of difficulties through the FYD meditation process.

Reflective writing

Methodologically, our study suggests that completing a meditation diary may be a potential part of any benefit in the practice. Journaling and expressive writing about difficult emotional experiences has been found to improve both subjective and objective measures of health and wellbeing (Park, 2010). A written phenomenal recounting of the FYD meditation is part of the FYD practice, however the two reflective study questions added at the end may have combined FYD with the benefits which the process of written emotional expression about the FYD meditation (Pennebaker, 2018). When we designed the study, we had not considered that journaling after the meditation may, itself, have been part of the potential mechanism for change. However, in reading the powerful written reflections it is plausible, even likely, that the writing about FYD may potentiate the meaning-making of the experience (Park, 2010; Martela and Steger, 2016). The written responses to the summative questions: How do you make sense of this experience? What was new? What was familiar? revealed compelling narratives of newly found confidence, empathy, and self-awareness.

Completing the post-meditation diary gave participants an opportunity to potentially shift how they narrate and create the meaning of their demon after the end of the meditation (Lichtenthal and Neimeyer, 2012). The demons are drawn from autobiographical memories which are not fixed but can shift and change over time. It is through a narrative telling of salient autobiographical experiences that one can engage in the process of making meaning (Fivush et al., 2017). While we cannot claim that the response to the second question (What, if anything, would you like to carry forward into your life from this [FYD] session?) will translate to day-to-day behavioral shifts, writing as a reflective process supports a skills transfer of action in the world. The study of reflective inquiry shows that the practitioner’s ability to learn and access former knowledge is greatly increased by personal reflection (Bolton, 2006). This closely resembles the quote by education and psychology pioneer John Bugg (1934) “We do not learn from an experience, we learn by reflecting on an experience.”

Writing in the diary possibly supported a shift in the emotional tone, and attitude toward demons which may be a step toward not only managing the emotional discomfort of the experience but lead to more fundamental shifts in how participants find meaning and relate to themselves, others, and the world. In this light, it is not surprising that these questions offered an opportunity for the rich new insights that were shared in this paper.

Perspective-taking and reappraisal

In responses to the question on meaning-making, we discovered that participants substantially reframed the needs, and wants of their demons and often experienced an empathy for these demons. Imagining and conversing with the demon can allow the space to be curious about the experience of the demon and give rise to feelings of care instead of distress or overwhelm (Lamm et al., 2007). The participant’s difficult emotions may be regulated through both an ability to create a distance between oneself and the demon, a self-other distinction, and new way of relating to the demon through perspective-taking and reappraisal (McRae and Gross, 2020).

The maladaptive self-schema of feeling bad and wrong about the demon can be shifted through personifying and dialoguing with the demon. The imagery process involved in these meditation steps was a catalyst for a new appraisal of the demon as deserving of care which helps regulate the difficult emotions associated with the demon (Lamm et al., 2007; Ekman and Halpern, 2015). Although what the demon represents (e.g., broken relationships, addiction, past trauma) remains real, the emotional difficulty around the demon can shift.

A significant number of participants made meaning of their experience by reporting a feeling of new confidence and worthiness as they reappraised their needs and desires as fundamentally worthy. When caught in a negative rumination about difficulties, individuals may not have easy access to this rich and fresh process. Negative rumination is a considered a transdiagnostic aspect of psychological distress, depression, and anxiety (McLaughlin and Nolen-Hoeksema, 2011). Perspective-taking through visualization of a demon is an interesting area to continue to explore in the study of FYD.

Compassion flexibility