95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 26 November 2019

Sec. Personality and Social Psychology

Volume 10 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02629

Evidence supports predictive roles of adult attachment orientations for the maintenance of social networking site (SNS) addiction, but the underlying mechanisms are mostly unknown. Based on attachment theory, this study explored whether online social support and the fear of missing out mediated the relationship between insecure attachment and social networking site addiction among 463 college students in China. A questionnaire was used to collect data using the Experience in Close Relationship Scale—Short Form, online social support scale, fear of missing out scale, and Chinese Social Media Addiction Scale. The results showed that online social support and fear of missing out mediated the relationship between anxious attachment and social networking site addiction in parallel paths and serially, and online social support negatively mediated the relationship between avoidant attachment and social networking site addiction. Theoretically, the present study contributes to the field by showing how insecure attachment is linked to SNS addiction. Practically, these findings could aid in future studies on SNS addiction prevention and interventions. Limitations of the present study were discussed.

A social networking site (SNS) has been defined as an online service platform or site that focuses on facilitating the building of social networks and social relations among people who share interests, activities, backgrounds, or real-life connections (Wikipedia, 2012). It enables us to communicate, send posts, comment, and other social interactions among close, intimate, acquaintances, and strangers. Although SNSs have considerable benefits, excessive use of SNS has been found to have detrimental effects on human behavior (Marino et al., 2018a). Therefore, many scholars have explored factors associated with SNS addiction, among which attachment has received much attention (Blackwell et al., 2017; Monacis et al., 2017; Flynn et al., 2018; Worsley et al., 2018a; Chen, 2019; D’Arienzo et al., 2019; Marino et al., 2019). However, the underlying mechanisms between attachment and SNS addiction remain unclear. The present study aimed to explore the possible mediating roles of online social support and “the fear of missing out” (FOMO) in the association between attachment and SNS addiction. Identifying the mechanism underlying this association may further aid researchers in understanding why some people develop problematic SNS use and help in the development of effective prevention and intervention measures for problematic SNS use.

SNS addiction has been defined as an excessive concern about social media, being driven by a motivation to use social media, and devoting so much time and effort to social media that it limits other social activities, studies, interpersonal relationships, mental health, and well-being (Kuss and Griffiths, 2011, 2017; Griffiths, 2013). Although it has not been acknowledged as a formal disorder, researchers have already made efforts to clarify this relatively new behavior. In the present study, we applied attachment theory to SNS addiction to explain why differences in adult attachment could contribute to this phenomenon.

Adult attachment theory posits that individual relationship in adulthood originates from social interactions in infancy experienced with primary caregivers. According to Bowlby, the earliest emotional bonds individuals formed their caregivers have a during impact that continues throughout life (Bowlby, 1969/1982, 1973, 1980). These experiences are the basis of the internal working model, which is the mental representation of the self and others. This model is relatively stable and carries into adulthood, thereby forming the basis of interpersonal relationships (Hazan and Shaver, 1987; Feeney and Noller, 1990; Bartholomew and Horowitz, 1991). When a caregiver is perceived as responsive, accessible, and trustworthy, an infant develops a secure attachment. However, when the primary caregiver is inconsistent, unavailable, and/or unresponsive, a negative internal working model and an insecure attachment can develop (Bretherton, 1987). While attachment orientations displayed in adulthood are not necessarily the same as those seen in infancy, research indicates that early attachments can have serious impacts on later relationships. There are two dimensions of insecure attachments in adults: attachment anxiety and avoidance (Brennan et al., 1998). Anxious attachment (i.e., having high attachment anxiety) is characterized by a hyperactivate attachment system, which leads to a constant need to seek support and comfort. Conversely, avoidant attachment is characterized by an underactive attachment system, which leads to continual inhibition of psychological and social relationship needs, excessive self-reliance, and a marked distance from others.

Prior studies found that anxious attachment dimension positively predicted SNS addiction, while avoidant attachment dimension negatively predicted SNS addiction (Blackwell et al., 2017; Worsley et al., 2018a). Such an association is reasonable. In essence, SNSs are platforms for establishing and maintaining social relationships in cyberspace. Individuals with high level of anxious attachment fear that they will be abandoned; thus, they use SNS excessively to seek attention and comfort. Avoidant attachment doubted the effectiveness of available support and believes that support from their partner will not help them feel better. Overly, they deny their desire for closeness and intimacy. To further understand, in light of differences in attachment, why some people use SNS problematically, it is necessary to consider some crucial mediating variables such as online social support and FOMO.

Based on the above analysis, we formed our first hypothesis: attachment anxiety positively predicts, while attachment avoidance negatively predicts, SNS addiction (H1).

Social support is usually defined as help offered by someone with whom the recipient has an interpersonal relationship, including family members, friends, colleagues, or significant others (Zimet et al., 1988). Online social support refers to the support individuals who obtain through online settings. Online social support has become more important in the modern age of computers, especially since the emergency of SNS. Compared to offline social support, the online social support provided by SNS has several unique features. Examples of how emotional support is provided by SNS include “likes” and “favorites,” described as paralinguistic digital affordances (PDAs), which are “cues in social media that facilitate communication and interaction without specific language associated with their messages” (Kim, 2014; Hayes et al., 2016). In addition, it has been found that instrumental support, informational support, network management (Lin et al., 2016), perceived support (Lu and Hampton, 2016), and enacted support are all provided through SNS. Moreover, online social support provided through SNS is positively linked with the continued use of SNS and is also a significant predictor of SNS addiction (Lin et al., 2018; Liu and Ma, 2018b; Brailovskaia et al., 2019).

There is ample evidence that attachment affects individual differences in perceptions of social support in offline settings (Florian et al., 1995; Priel and Shamai, 1995; Anders and Tucker, 2000; Rholes et al., 2001). Adults with secure attachment are often confident that social support is available to them, and they are satisfied with the social support they receive. By contrast, adults with insecure attachment report receiving less social support and being less satisfied with the social support they do receive. However, the association between adult attachment orientations and perceptions of online social support may be different. Prior studies found that individuals with an anxious attachment attempt to seek social support and comfort online (Hart et al., 2015). They often worry that their friends will abandon them, and they try to be as emotionally close as possible to others. These individuals are, relatively, more sensitive to feedback and express more feedback-seeking behaviors on SNS than others (Hart et al., 2015). Individuals with an avoidant attachment dimension, however, generally deactivate their attachment systems to inhibit their psychological needs by expressing self-reliance, maintaining an emotional distance from others, and suppressing their needs for social support, such as likes, comments, and posts from others through SNS.

Based on our review of the relevant literature, we hypothesized that attachment anxiety would positively predict a need for online social support and a tendency toward SNS addiction, while attachment avoidance would negatively predict the need for online social support. In other words, the need for online social support mediated relationship between the insecure attachment and SNS addiction (H2).

FOMO is a recent phenomenon attracting scholarly attention as the prevalence of SNS increases. It refers to the feeling that others may be having rewarding experiences from which one is absent, characterized by the desire to stay connected with what others are doing (Przybylski et al., 2013). Thus, FOMO could act as both a predictor of social media engagement and addiction (Alt, 2015; Elhai et al., 2016) and a mediator between individual differences and SNS addiction (Beyens et al., 2016; Dempsey et al., 2019).

Indirect and direct evidence supports the idea that attachment differences may be correlated with FOMO. Studies have found that attachment is linked to psychological needs, which are correlated with FOMO. Specifically, both attachment anxiety and avoidance have been related to satisfying basic psychological needs (LaGuardia et al., 2000; Wei et al., 2005; Felton and Jowett, 2013; Miner et al., 2014). Other studies found that both anxious and avoidant attachment dimensions positively predicted basic psychological need satisfaction (Wei et al., 2005). That is the higher level of insecure attachment, the higher level of basic psychological needs frustration. Recently, a study conducted based on Facebook found that anxious attachment negatively correlated with the basic psychological need of “relatedness” (Lin, 2016; Chen, 2019). Furthermore, research showed that frustration with psychological needs led to FOMO (Przybylski et al., 2013; Xie et al., 2018). Self-determination theory proposes three intrinsic individual needs: competence, relatedness, and autonomy (Ryan and Deci, 2000). If these needs are not properly satisfied, it can develop maladaptive behaviors. In social media settings, individuals whose basic psychological needs are not satisfied are more likely to experience FOMO (Przybylski et al., 2013). Furthermore, a study found that both attachment anxiety and avoidance positively influenced FOMO (Blackwell et al., 2017), but this study did not address the reasons for those relationships. Overall, these studies indicate that the higher one’s level of attachment anxiety, the more one experiences FOMO.

Based on this analysis, we hypothesized that attachment anxiety and avoidance would positively predict FOMO, while the attachment anxiety would positively predict SNS addiction. In other words, FOMO mediates the relationship between insecure attachments and SNS addiction (H3).

Based on our literature review, we theorized that online social support and FOMO play mediating roles in the link between insecure attachment and SNS addiction. To yield further insights into the exact association between insecure attachment and SNS addiction among Chinese college students, this study adopted an integrated multiple mediation model capable of simultaneously examining multiple influencing mechanisms of insecure attachment on SNS addiction. It has been suggested that a multiple mediation model could explore the complex mechanisms of consequent variables, making the model a crucial tool for improving the accuracy and applicability of theories (Hayes, 2017). Under the sequential mediation model, online social support and FOMO may exert a sequential mediating effect on the link between attachment avoidance, anxiety, and SNS addiction, with avoidance and anxiety attachment first giving rise to higher FOMO, which in turn promotes a higher need for online social support. Thus, insecure attachment can be viewed as a predictor for SNS addiction. Existing research has provided indirect evidence for this sequential mediation model. Liu and Ma (2018b) found that FOMO positively correlated with the need for online social support. Thus, we hypothesized that FOMO could positively predict the need for online social support. That is, FOMO and online social support serial mediated the relationship between insecure attachment and SNS addiction (H4). The study’s conceptual model is shown in Figure 1.

A total of 463 college students in China (344 females) aged 17–24 years (M = 19.94, SD = 1.11) volunteered to participate in our study and completed a questionnaire. The questionnaire was designed to collect information on the dependent variable (SNS addiction), the key independent variables of experiences in close relationships (attachment dimensions), online social support, FOMO, and demographic characteristics. All materials and procedures used in the study were approved by the Ethics in Human Research Committee of Chongqing University of Posts and Telecommunications. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants who were told that their participation was voluntary and they could terminate their participation at any time. The participants received no form of reward.

Adult attachment orientation was measured using the Experience in Close Relationship Scale—Short Form (ECR-SV; Wei et al., 2007). The ECR-SV is a 12-item index on adult attachment orientations with responses rated on a seven-point Likert-type scale where 1 = strongly disagree through 7 = strongly agree. The 12 items are on two six-item subscales, one on anxious attachment and the other on avoidant attachment. The ECR-SV has demonstrated strong psychometric reliability and validity in Asian population samples (Lee and Shin, 2019, pp. 119–127). In the present study, Cronbach’s α = 0.84 for the anxious attachment items and α = 0.75 for the avoidant attachment items.

Online social support was measured using the Chinese online social support scale (Liu and Ma, 2018b), which was adapted from a Facebook-based measure of social support (McCloskey et al., 2015). The Chinese version comprises three dimensions with three items for each: perceived support, emotional support, and informational/instrumental support. Cronbach’s α for the whole scale was 0.80 in the present study.

FOMO was measured using 10 items with responses rated on a five-point Likert-type scale where 1 = not at all true of me through 5 = extremely true of me (Przybylski et al., 2013). The scores on the items were summed to create a composite measure of the extent to which the respondents feared that they were missing out on experiences and others were perceived to have. Cronbach’s α in the present study was 0.83.

The Chinese Social Media Addiction Scale (Liu and Ma, 2018a) was used to measure the extent of SNS addiction. It comprises 28 items divided into six dimensions: preference for online social interaction (6 items), mood alteration (5 items), negative consequences and continued use (5 items), compulsive use and withdrawal (6 items), salience (3 items), and relapse (3 items). Responses were rated on a Likert scale where 1 = strongly disagree through 5 = strongly agree and higher scores indicated more SNS addiction. In the present study, Cronbach’s α for the whole scale was 0.94.

All data collected in this study were recorded on a computer and processed using SPSS 18.0 and Mplus 7.4. Data processing was carried out in four steps, in accordance with recent literature on multiple mediation analyses. First, a factor analysis was performed to conduct a common variance analysis for testing common method biases. Second, scores from the four questionnaires were analyzed using descriptive statistics and correlation analysis. Third, Mplus 7.4 was used to evaluate the mediation effects of FOMO and online social support. The mediation model was estimated using the bootstrapping method to produce 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals of the effects from 5,000 samples of the data. Confidence intervals that did not include zero were interpreted as statistically significant effects at p ≤ 0.05. Before mediation analysis, a t test was conducted to explore whether there were gender differences concerning four variables in response to the gender imbalance in the present study. Before four-step formal analysis was performed, a K-means cluster analysis was conducted to explore how many participants displayed problematic SNS use.

K-means cluster analysis was used to identify participants’ levels of SNS addiction. Cluster analysis is a statistical method that allows participants to be divided into groups based on their similarities. To examine SNS addiction, a series of K-means cluster analyses were performed for the SNS addiction scores. The analysis resulted in participants being assigned to three groups: ordinary user, risky user, and problematic user (addictive user). The number of participants in each group was 104, 240, and 119, respectively; thus, the prevalence of SNS addiction in present study is 25.7%.

Common variance analysis was applied to the four questionnaires through factor analysis. The χ2 statistic of Bartlett’s test of Sphericity was significant. After principal component analysis, 12 eigenvalues greater than 1 were extracted. The first factor explained 26.9% of the total variance, which was less than the 40% required by the critical standard (Podsakoff et al., 2003), demonstrating that the questionnaires used in the current study had no significant issues related to common method biases.

Participants’ descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. Anxious attachment dimension was positively related to the need for online social support, FOMO, SNS addiction, and avoidant attachment (all p < 0.01). Moreover, anxious and avoidant attachment positively correlated with each other (p < 0.01), but the relationships between avoidant attachment and online social support, FOMO, and SNS addiction were not statistically significant.

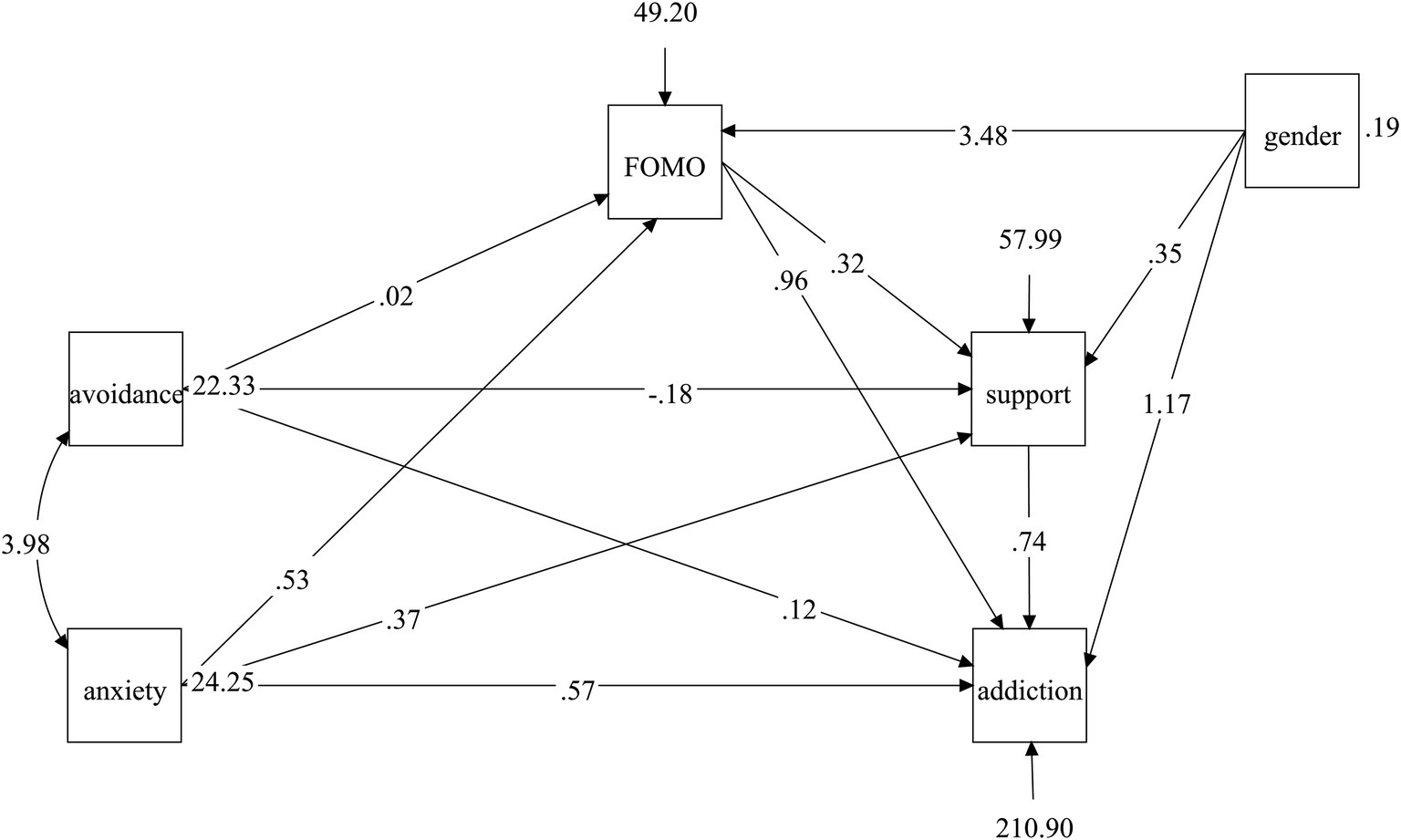

To explore gender differences relating to the variables, t tests showed gender differences for FOMO (Mmale = 24.79, Mfemale = 20.79, t = 5.01, p < 0.001), need for online social support (Mmale = 36.67, Mfemale = 34.68, t = 2.23, p < 0.05), and SNS addiction (Mmale = 83.03, Mfemale = 76, t = 3.45, p < 0.01), but not for attachment avoidance (Mmale = 21.85, Mfemale = 21.88, t = −0.06, p = 0.95) and anxious attachment (Mmale = 22.58, Mfemale = 21.60, t = 1.86, p = 0.06). Thus, when we performed a mediation analysis, gender was added as a control variable. In this model, gender significantly predicted FOMO (b = 3.48, p < 0.001) but not the need for online social support (b = 0.35, p = 0.71) or SNS addiction (b = 1.17, p = 0.46).

We estimated the indirect effects of the need for online social support and FOMO on the relationships between insecure attachment and SNS addiction. The results showed that all the paths were significant, except the path from avoidant attachment to FOMO and SNS addiction (b = 0.02, p = 0.77 and b = 0.12, p = 0.55, respectively). The whole model showed excellent fit indices [χ2 = 3.63, p of χ2 = 0.16, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.04, 95% CI = (0.00, 0.11), SRMR = 0.02]. Specifically, avoidant attachment negatively predicted the need for online social support (b = −0.18, p < 0.05), while the latter positively predicted SNS addiction (b = 0.74, p < 0.001). An anxious attachment dimension positively predicted the need for online social support (b = 0.37, p < 0.001), FOMO (b = 0.53, p < 0.001), and SNS addiction (b = 0.57, p < 0.01). Moreover, FOMO positively predicted the need for online social support (b = 0.32, p < 0.001). Unstandardized coefficients of the model are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The unstandardized coefficients of the model. All the paths were significant, except the path from avoidant attachment to FOMO and SNS addiction. Gender was added as a control variable.

The indirect effects of needing online social support and FOMO are shown in Table 2, which indicates that needing online social support negatively mediated the relationship between avoidant attachment and SNS addiction, whereas FOMO, as well as needing online social support, serially and in parallel mediated the relationship between anxious attachment and SNS addiction.

The present study aimed to explore the association between insecure attachment and SNS addiction and test whether both the online social support and FOMO mediate their relationship. We hypothesized that an attachment anxiety would positively predict SNS addiction, while an attachment avoidance would be negatively correlated with SNS addiction. Additionally, we hypothesized that both the need for online social support and FOMO would mediate this association both in parallel and serially. Our results partially supported our hypotheses. Specifically, an anxious attachment dimension positively correlated with SNS addiction, but the link between an avoidant attachment dimension and SNS addiction was not significant. Furthermore, the need for online social support and FOMO mediated the association both in parallel and serially for attachment anxiety, while only online social support mediated this association for an attachment avoidance.

An anxious attachment orientation is characterized by devoting much time to relationships concerns and a lack of belonging. This can be satisfied by using SNS, which, in turn, may develop into SNS addiction. Conversely, an avoidant attachment dimension is linked with refusal of intimacy and keeping emotional distance in relationships; therefore, individuals with this attachment may use SNS less than other people. As a new type of behavioral addiction, SNS addiction has received much scholarly attention globally in recent years, and there are numerous studies exploring the risk factors linked to SNS addiction (Marino et al., 2018a,b). Prior studies found that attachment, especially insecure attachment, is closely related to SNS general use and addiction (Blackwell et al., 2017; Monacis et al., 2017; Flynn et al., 2018; Worsley et al., 2018a,b; Chen, 2019; D’Arienzo et al., 2019; Marino et al., 2019). Our results are consistent with prior findings. For example, individuals with high attachment anxiety used Facebook more frequently were more likely to use it when feeling negative emotions and were more concerned about how others perceived them on Facebook. While attachment anxiety predicted more feedback seeking and general Facebook activity, attachment avoidance predicted less, and feedback sensitivity mediated the effect of attachment anxiety on Facebook activity (Hart et al., 2015).

Beyond examining the association between insecure attachment and SNS addiction, we further tested whether online social support and FOMO mediated this connection. For anxiety attachment, both the need for online social support and FOMO mediate the association in parallel and serially. That is, the more attachment anxiety one feels, the higher his or her FOMO and need for online social support, which, in turn, can lead to a higher level of SNS addiction. This correlation between attachment and FOMO coincided with findings in a previous study (Blackwell et al., 2017). This study also found that FOMO and anxiety attachment were significantly correlated. We hypothesize that it is a basic human desire to have our psychological needs met that links an anxious attachment with FOMO. High attachment anxiety stems from negative interactions in childhood with an unavailable and unresponsive caregiver, in which an individual’s basic psychological needs were neglected and not satisfied. According to the source review of FOMO (Przybylski et al., 2013), if an individual’s need is not satisfied, they can develop FOMO, which can lead to excessive use of SNS. However, the present study did not consider the variable of basic psychological need satisfaction, and future studies could test this assumption. Moreover, an anxious attachment dimension predicted a high level of online social support. Previous studies confirmed the association between anxiety attachment and both perception and provision of social support in offline settings (Collins and Feeney, 2004). The present study added to the current body of literature by showing that individuals with an anxious attachment dimension may also seek support and comfort through SNS to the point of overuse. The present study also found that FOMO positively predicted the need for online social support. Thus, FOMO and the need for online social support serially mediate the relationship between anxious attachment and SNS addiction.

However, for avoidant attachment dimension, only the online social support negatively mediated the avoidance-SNS addiction relationship; the serial mediating effect of FOMO and the need for online social support was not significant. Avoidant attachment is characterized by excessive self-reliance, an inhibition of needs, and avoiding intimacy. Thus, individuals with this attachment may regard online social support as useless, as they believe that there is nobody who would provide help. Moreover, attachment avoidance did not predict FOMO. Although there is evidence that attachment avoidance is correlated with the extent to which basic psychological need is satisfied (Wei et al., 2005), the present study found that attachment avoidance is not correlated with FOMO. These findings indicate that FOMO may stem from attachment anxiety rather than avoidance. Therefore, SNS may not be a useful platform for them to rely on, to keep an eye on what others is doing, and consequently, avoidant attachment is not positively associated with SNS addiction.

The present study has both theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, the present study contributes to the field by showing how insecure attachment is linked to SNS addiction. Although there are several existing studies exploring the association between attachment and SNS addiction, the present study examined the role of online social support and FOMO in this association. In the era of SNS, online social support such as likes, comments, posts, and reposts is so common that its fundamental characteristics are not fully understood. We found that online social support is indeed a risk factor for SNS addiction. Moreover, FOMO has been consistently found to be a predictor of SNS addiction. In the present study, we provide evidence that SNS addiction is correlated with insecure attachment, especially anxious attachment dimension. Practically, these findings could aid in future studies on SNS addiction prevention and interventions. It has been documented that attachment security priming is an effective procedure to reduce attachment anxiety (Gillath and Karantzas, 2019). It entails exposing individuals to stimuli designed to activate a sense of love, comfort, and safety. Attachment security priming may have beneficial effects, especially for those whose attachment involves hypervigilance to threats. Consequently, such a technique could be a potential choice when considering an intervention of SNS addiction. Furthermore, offline social support is important to individuals. If the need for this support is satisfied, they may not turn to SNS for online social support, consequently leading to less SNS use.

The present study is not without limitations. First, this study’s population sample mostly included females (74%), and although we controlled for the effects of gender, this lack of gender balance should be avoided in future research. Second, the study’s cross-sectional design prevented the ability to make causal inferences. Third, the self-report data might threaten the accuracy of the statistical relationships between variables. Last, it is suggested that FOMO may be one dimension of SNS addiction (Kuss and Griffiths, 2017). Thus, future study should test this assumption. However, despite its limitations, the present study demonstrated that attachment theory is useful for explaining addictive behavior relating to SNS. Different from general internet addiction, SNS addiction is a relationship-centered disorder. There are still many variables associated with attachment that need to be further tested in future studies, such as security, emotion regulation strategies and efficacy, psychological distress, and reassurance.

While an attachment anxiety was significantly and positively correlated with SNS addiction, attachment avoidance was not significantly linked with SNS addiction. FOMO and online social support, in parallel and serially, mediated the relationship between anxiety attachment and SNS addiction, and the need for online social support negatively mediated the relationship between an attachment avoidance and SNS addiction.

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendation of the University’s Human Research Ethics Committee with written informed consent from all subjects. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the University’s Human Research Ethics Committee.

CL designed the study and collected and analyzed the data. J-LM wrote the manuscript.

The present study was supported by the humanities and social science research project of the Chongqing Education Committee (17SKG192, 16SKGH054) and the key social science program of Chongqing University of Posts and Telecommunications (2017KZD08).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Alt, D. (2015). College students’ academic motivation, media engagement and fear of missing out. Comput. Hum. Behav. 49, 111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.02.057

Anders, S. L., and Tucker, J. S. (2000). Adult attachment orientation, interpersonal communication competence, and social support. Pers. Relat. 7, 379–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2000.tb00023.x

Bartholomew, K., and Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 61, 226–244. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.61.2.226

Beyens, I., Frison, E., and Eggermont, S. (2016). “I don’t want to miss a thing”: adolescents’ fear of missing out and its relationship to adolescents’ social needs, Facebook use, and Facebook related stress. Comput. Hum. Behav. 64, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.083

Blackwell, D., Leaman, C., Tramposch, R., Osborne, C., and Liss, M. (2017). Extraversion, neuroticism, attachment style and fear of missing out as predictors of social media use and addiction. Pers. Individ. Differ. 116, 69–72. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.039

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation: Anxiety and anger. New York: Basic Books.

Brailovskaia, J., Rohmann, E., Bierhoff, H. W., Schillack, H., and Margraf, J. (2019). The relationship between daily stress, social support and Facebook addiction disorder. Psychiatry Res. 276, 167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.05.014

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., and Shaver, P. R. (1998). “Self-report measurement of adult attachment: an integrative overview” in Attachment theory and close relationships. eds. J. A. Simpson and W. S. Rholes (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 46–76.

Bretherton, I. (1987). “New perspectives on attachment relations: security, communication, and internal working models” in Wiley series on personality processes handbook of infant development. ed. J. D. Osofsky (Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons), 1061–1100.

Chen, A. (2019). From attachment to addiction: the mediating role of need satisfaction on social networking sites. Comput. Hum. Behav. 98, 80–92. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.03.034

Collins, N. L., and Feeney, B. C. (2004). Working models of attachment shape perceptions of social support: evidence from experimental and observational studies. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 87, 363–383. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.363

D’Arienzo, M. C., Boursier, V., and Griffiths, M. D. (2019). Addiction to social media and attachment styles: a systematic literature review. Int. J. Ment. Heal. Addict. 17, 1094–1118. doi: 10.1007/s11469-019-00082-5

Dempsey, A. E., O'Brien, K. D., Tiamiyu, M. F., and Elhai, J. D. (2019). Fear of missing out (FoMO) and rumination mediate relations between social anxiety and problematic Facebook use. Addict. Behav. Rep. 9:100150. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2018.100150

Elhai, J. D., Levine, J. C., Dvorak, R. D., and Hall, B. J. (2016). Fear of missing out, need for touch, anxiety and depression are related to problematic smartphone use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 63, 509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.079

Feeney, J. A., and Noller, P. (1990). Attachment style as a predictor of adult romantic relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 58, 281–291. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.58.2.281

Felton, L., and Jowett, S. (2013). Attachment and well-being: the mediating effects of psychological needs satisfaction within the coach–athlete and parent–athlete relational contexts. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 14, 57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.07.006

Florian, V., Mikulincer, M., and Bucholtz, I. (1995). Effects of adult attachment style on the perception and search for social support. J. Psychol. 129, 665–679. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1995.9914937

Flynn, S., Noone, C., and Sarma, K. M. (2018). An exploration of the link between adult attachment and problematic Facebook use. BMC Psychol. 6:34. doi: 10.1186/s40359-018-0245-0

Gillath, O., and Karantzas, G. (2019). Attachment security priming: a systematic review. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 25, 86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.03.001

Griffiths, M. D. (2013). Social networking addiction: emerging themes and issues. J. Addict. Res. Ther. 4:e118. doi: 10.4172/2155-6105.1000e118

Hart, J., Nailling, E., Bizer, G. Y., and Collins, C. K. (2015). Attachment theory as a framework for explaining engagement with Facebook. Pers. Individ. Differ. 77, 33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.12.016

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Publications.

Hayes, R. A., Carr, C. T., and Wohn, D. Y. (2016). One click, many meanings: interpreting paralinguistic digital affordances in social media. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 60, 171–187. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2015.1127248

Hazan, C., and Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 52, 511–524. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.52.3.511

Kim, H. (2014). Enacted social support on social media and subjective well-being. Int. J. Commun. 8, 2340–2342. doi: 10.4324/9781351231879-12

Kuss, D. J., and Griffiths, M. D. (2011). Online social networking and addiction—a review of the psychological literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 8, 3528–3552. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8093528

Kuss, D. J., and Griffiths, M. D. (2017). Social networking sites and addiction: ten lessons learned. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14:E311. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14030311

LaGuardia, J. G., Ryan, R. M., Couchman, C. E., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Within-person variation in security of attachment: a self-determination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfillment, and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 79, 367–384. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.3.367

Lee, J. Y., and Shin, Y. J. (2019). Experience in close relationships scale–short version (ECR–S) validation with Korean college students. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 52, 119–127. doi: 10.1080/07481756.2018.1497431

Lin, J. H. (2016). Need for relatedness: a self-determination approach to examining attachment styles, Facebook use, and psychological well-being. Asian J. Commun. 26, 153–173. doi: 10.1080/01292986.2015.1126749

Lin, M. P., Wu, J. Y. W., You, J., Chang, K. M., Hu, W. H., and Xu, S. (2018). Association between online and offline social support and internet addiction in a representative sample of senior high school students in Taiwan: the mediating role of self-esteem. Comput. Hum. Behav. 84, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.007

Lin, X., Zhang, D., and Li, Y. (2016). Delineating the dimensions of social support on social networking sites and their effects: a comparative model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 58, 421–430. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.01.017

Liu, C., and Ma, J. (2018a). Development and validation of the Chinese social media addiction scale. Personal. Individ. Differ. 134, 55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.05.046

Liu, C., and Ma, J. (2018b). Social support through online social networking sites and addiction among college students: the mediating roles of fear of missing out and problematic smartphone use. J. Curr. Psychol. (in press). doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-0075-5

Lu, W., and Hampton, K. N. (2016). Beyond the power of networks: differentiating network structure from social media affordances for perceived social support. New Media Soc. 19, 861–879. doi: 10.1177/1461444815621514

Marino, C., Gini, G., Vieno, A., and Spada, M. M. (2018a). The associations between problematic Facebook use, psychological distress and well-being among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 226, 274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.10.007

Marino, C., Gini, G., Vieno, A., and Spada, M. M. (2018b). A comprehensive meta-analysis on problematic Facebook use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 83, 262–277. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.009

Marino, C., Marci, T., Ferrante, L., Altoè, G., Vieno, A., Simonelli, A., et al. (2019). Attachment and problematic Facebook use in adolescents: the mediating role of metacognitions. J. Behav. Addict. 8, 63–78. doi: 10.1556/2006.8.2019.07

McCloskey, W., Iwanicki, S., Lauterbach, D., Giammittorio, D. M., and Maxwell, K. (2015). Are Facebook “friends” helpful? Development of a Facebook-based measure of social support and examination of relationships among depression, quality of life, and social support. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 18, 499–505. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2014.0538

Miner, M., Dowson, M., and Malone, K. (2014). Attachment to God, psychological need satisfaction, and psychological well-being among Christians. J. Psychol. Theol. 42, 326–342. doi: 10.1177/009164711404200402

Monacis, L., de Palo, V., Griffiths, M. D., and Sinatra, M. (2017). Social networking addiction, attachment style, and validation of the Italian version of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale. J. Behav. Addict. 6, 178–186. doi: 10.1556/2006.6.2017.023

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Priel, B., and Shamai, D. (1995). Attachment d perceived social support: effects on affect regulation. Pers. Individ. Differ. 19, 235–241. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(95)91936-T

Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R., and Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Comput. Hum. Behav. 29, 1841–1848. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.014

Rholes, W. S., Simpson, J. A., Campbell, L., and Grich, J. (2001). Adult attachment and the transition to parenthood. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 81, 421–435. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.81.3.421

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Wei, M., Russell, D. W., Mallinckrodt, B., and Vogel, D. L. (2007). The experiences in close relationship scale (ECR)-short form: reliability, validity, and factor structure. J. Pers. Assess. 88, 187–204. doi: 10.1080/00223890701268041

Wei, M., Shaffer, P. A., Young, S. K., and Zakalik, R. A. (2005). Adult attachment, shame, depression, and loneliness: the mediation role of basic psychological needs satisfaction. J. Couns. Psychol. 52, 591–601. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.4.591

Wikipedia (2012). List of social networking websites. Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_social_networking_websites (Accessed September 19, 2012).

Worsley, J. D., Mansfield, R., and Corcoran, R. (2018a). Attachment anxiety and problematic social media use: the mediating role of well-being. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 21, 563–568. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2017.0555

Worsley, J. D., McIntyre, J. C., Bentall, R. P., and Corcoran, R. (2018b). Childhood maltreatment and problematic social media use: the role of attachment and depression. Psychiatry Res. 267, 88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.05.023

Xie, X., Wang, Y., Wang, P., Zhao, F., and Lei, L. (2018). Basic psychological needs satisfaction and fear of missing out: friend support moderated the mediating effect of individual relative deprivation. Psychiatry Res. 268, 223–228. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.07.025

Keywords: adult attachment, anxious attachment, fear of missing out, online social support, social networking site addiction

Citation: Liu C and Ma J-L (2019) Adult Attachment Orientations and Social Networking Site Addiction: The Mediating Effects of Online Social Support and the Fear of Missing Out. Front. Psychol. 10:2629. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02629

Received: 01 June 2019; Accepted: 07 November 2019;

Published: 26 November 2019.

Edited by:

Nicholas Furl, Royal Holloway, University of London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Abira Reizer, Ariel University, IsraelCopyright © 2019 Liu and Ma. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jian-Ling Ma, jianling_ma@163.com

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.