- TrustGov Project, Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Southampton, Southampton, United Kingdom

Recent work has emphasised the need for greater nuance in qualifying both the presence and absence of political trust in different political systems. The concept of trust may thus be more effectively perceived and analysed as a family with trust, mistrust, and distrust as its members. Expanding to a family of trust means that new ways of capturing these attitudes in empirical survey work may be needed and a way of critically driving that exploration is to investigate how gender influences how they are understood. In this paper, we use insights from focus group discussions on a series of newly designed trust, mistrust and distrust questions to identify: 1) how citizens perceive these different concepts and 2) how gendered these perceptions are. We then draw on new survey data gathered through the TrustGov project to test how the focus group findings impact survey responses and thus identify: 3) which survey questions are more likely to effectively measure the three concepts. We show that the differences highlighted in our qualitative work underscore the need to develop a more systematic mixed methods research agenda on both the expanded family of political trust and gender. We emphasise that global comparative work to capture diverse gender effects across different political systems are the necessary next steps for the field.

Introduction

“Political trust thus functions as the glue that keeps the system together and as the oil that lubricates the policy machine. Mistrust, or rather political scepticism, plays an equally important role in representative democracy. Critical citizens are more likely to engage in political activities and to keep office-holders accountable. When mistrust turns into widespread distrust and cynicism, then the quality of democratic representation itself may change.” (van der Meer and Zmerli, 2017, p. 1)

Political trust has long been considered essential to the effective functioning of democracy (see for example, Levi and Stoker, 2000; Uslaner, 2017; van der Meer, 2017; Zmerli and van der Meer, 2017). Scholars and commentators often lament an apparent decline in political trust as a risk to democracy (Merkel, 2014). As Devine et al. (2020) argue, there is growing awareness, however, of a need for greater conceptual nuance to begin to address the nature (or even existence) of this change. Indeed, more recent reviews have qualified both the presence of trust and its absence (Sniderman, 2017; Citrin and Stoker, 2018; Karmis and Rocher, 2018). Trust may be sceptical for example, (Norris, 1999, 2011; Dalton and Welzel, 2014), and a lack of trust might lead to either a state of mistrust or distrust among citizens (Lenard, 2008; Citrin and Stoker, 2018). The concept of trust may thus be more effectively perceived and analysed as a family with trust, mistrust and distrust as members. This conceptual development demands empirical extension, with a particular focus on the measures needed to effectively capture these ideas.

At the same time, political attitudes, including trust, have been shown to vary by gender, often significantly (Campbell, 2012; see also Campbell and Winters, 2008). Studies have concluded that women have less political knowledge (Dow, 2009), show lower political interest (Burns, 2008), trust less (Alesina and La Ferrara, 2002) and participate less (Sartori, Tuorto and Ghigi, 2017). Whilst each of these findings has been disputed (Schoon and Cheng, 2011; Campbell, 2012; Fraile, 2014; Reinhardt, 2015), it still poses important questions on the nature of the gender gap. Some evidence points to the fact that women respond differently to surveys when compared to men. This may be due to womens’ increased risk aversion (Eckel and Grossman, 2008; Lizotte and Sidman, 2009), or increased time commitments that prevent participation (Sartori, Tuorto and Ghigi, 2017), but it may also be caused by differing interpretations of the question wording, which in itself can provoke a risk averse response and be a product of time constraints. We do not believe that women simply know less or are less interested in politics, therefore we examine this gender gap through the lens of question interpretation. This allows us to establish the strength of conceptual and measurement validity in our expansion of the trust family. As we ascribe to the argument that trust should vary between subgroups in society, we use gender as a first exploration of these variations, and a proof of concept for our definitions of trust, mistrust, and distrust.

Additionally, survey questions are the standard method of assessing a range of attitudes in political science, including trust. Whilst batteries are designed using best practice, they are rarely tested with other methodologies. Here we present unique data that a) furthers the new conceptual terms and their questions for the study of political trust, b) asks citizens to convey how they understand these concepts, and c) identifies the ramifications of these understandings for quantitative surveys. In this way, we are able to ascertain key challenges that exist for the future of political trust research. We use insights from focus group discussions on a series of newly designed trust, mistrust and distrust questions to show: 1) how citizens perceive these different concepts and 2) the extent to which these perceptions are gendered. We then draw on new survey data gathered through the TrustGov project to test how the focus group findings impact analyses of survey responses and thus identify: 3) which survey questions are more likely to effectively measure the three concepts. We show that the differences highlighted in our qualitative work underscore the need to develop a more systematic mixed methods research agenda on both the expanded family of political trust and gender, emphasising that global comparative work to capture diverse gender effects across different political systems are the necessary next steps for the field.

A “Family of Trust”

Traditionally, research in political trust sees trust as an essential part of the effective workings of the social, economic, and political aspects of our modern life. Social capital theorists see a large amount of horizontal, interpersonal, and generalised trust as a precondition for many normatively desired behaviors: it is required for positive social cooperation and the ability to solve collective problems, to foster community ties and engagement without the need to rely on legal or other institutional mechanisms (Putnam, 1993; Fukuyama, 1995). Similarly, economists emphasise the role of trust in the execution of contracts and investments, and to stimulate market growth (Gambetta, 2000; Zak and Knack, 2001). Finally, vertical political trust is seen as essential to civic engagement, respect for the rule of law and the legitimacy of the democratic system as a whole (Almond and Verba, 1963; Easton, 1975). It is unsurprising then that observed declines in social and political trust have caused periodic alarm to many political scientists. This has resulted in a recurrent debate on whether or not there is a “crisis of political trust”, and what its consequences may be if it exists (van der Meer, 2017).

Whilst there is little consensus on the debate of a crisis, the salience of trust is without question. In a recent speech, the UN Secretary General proclaimed that “four horsemen” make up the world’s greatest contemporary challenges, defining them as “looming threats that endanger 21st-century progress and imperil 21st-century possibilities”; alongside terrorism and climate change, “The third horseman is deep and growing global mistrust” (Gutteres, 2020). The change has received worldwide acknowledgement, and Antonio Gutteres specifically identifies mistrust as a challenge. Moreover, the Coronavirus pandemic has shed light on the continued importance of trust, including its expanded family. Using new comparative data collected in May 2020 in the United Kingdom, United States, Italy, and Australia, Jennings et al., 2021 (forthcoming) argue that the “concepts of distrust and mistrust provide a more complete understanding of how the public reacts to, and shapes, government action during crises”. This underscores the need for greater nuance in assessing levels of trust, mistrust and distrust, and how people make those judgements.

Indeed many now argue for the expansion of conceptualising trust into a family which also includes mistrust and distrust (Hardin, 2002; Lenard, 2008; Citrin and Stoker, 2018; Bertsou, 2019; Devine et al., 2020). It is acknowledged that political trust is not a dichotomy, nor a continuum, but three distinct positions. Lenard (2008, p. 313) for example, defines mistrust as “a cautious attitude toward others; a mistrustful person will approach interactions with others with a careful and questioning mindset” and distrust as “a suspicious or cynical attitude toward others”. Citrin and Stoker (2018, p. 50) define mistrust and distrust as follows: “mistrust reflects doubt or skepticism about the trustworthiness of the other, while distrust reflects a settled belief that the other is untrustworthy”. Bertsou (2018, p. 215) defines distrust as “a negative attitude held by an individual toward her political system or its institutions and agents”. The idea generally, as illustrated by the earlier quote from van der Meer and Zmerli (2017), is that political trust makes good governance possible: mistrust, in the right measure, supports good governance by driving accountability; distrust is viewed as a threat to good governance, as it risks disengagement and disorder. These considerations indicate a need for better understanding of how these concepts are interpreted and operationalised in political life. Empirically, most measures of the trust family aim to express the general orientations of citizens toward various political actors, institutions, or the system as a whole. Correctly quantifying them, therefore, is of utmost importance.

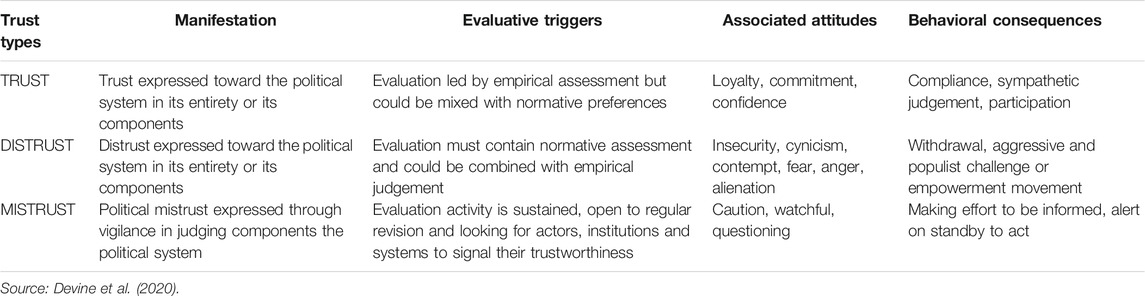

Devine et al. (2020) define the trust family as sharing the dynamic and contextual traits of a three-place formulation: A trusts/mistrust/distrusts B in domain X. When considering political trust, this often means citizen A mis-/dis-/trusting politician or institution B to serve the public in some way. In this paper, we focus on the relational link between A and B. As Table 1 shows, a defining feature of political trust is positive expectations toward politics or a part of it; a defining feature of distrust is negative expectations toward politics or a part of it; a defining feature of mistrust is one of vigilance. Whilst it has been demonstrated that these concepts can be distinguished empirically, some of the newly designed questions were indicative of both mistrust and distrust (Devine et al., 2020). This points to an argument that has been severely under-represented in political trust research: different demographic groups might understand and operationalise trust, mistrust or distrust positions in different ways. This seems particularly relevant in the effort to broaden the concept, and measures, of trust to its wider family and identify consistent ways of capturing the positions. Therefore, this paper explores interpretations of the concepts over genders as a first step in both conceptually and empirically improving the measurements of the trust family.

Gender, Survey Responses, and Trust

Exploring these themes through a gendered lens is a natural first step for identifying subgroup differences and more broadly testing equity of interpretations. Gender is something that everybody experiences, in almost all spheres of life. Social role theory explains how we are socialised into roles and behaviors based on our perceived genders. These roles are diffuse as well as specific, and impact personality traits, skill development and career choice, and also how politics is considered (Diekman and Schneider, 2010; Yavorsky, Dush and Schoppe-Sullivan, 2015; Katz, 2016; Schneider and Bos, 2019). In political systems, women are less represented because men are socialised into having characteristics we associate with politicians and leaders. Indeed, Schneider and Bos speak of this in the extremes when considering United States politics: “the same masculinized election space that tells women they are unwelcome also signals to voters that the presence of a female candidate threatens the gender hierarchy as women step outside their prescribed roles” (2019, p. 174; see also Rudman et al., 2012).

Women are purported to have less political knowledge than men, and to be less interested in politics. However, it has been shown that this is a function of how we ask the question: “Women say that they are less interested in politics than men, although this gap is reversed when they are asked how interested they are in specific policy areas such as education or health” (Campbell, 2012, p. 704; see also Campbell and Winters, 2008). It is also explained by women’s increased propensity to choose a “Don’t know” option in surveys rather than guess (Eckel and Grossman, 2008; Lizotte and Sidman, 2009; Campbell, 2012; Fortin-Rittberger, 2020). These observations highlight a difficulty in distinguishing between whether observed gender gaps represent an empirical difference in the attitude or behavior under consideration; or whether they are due to gendered interpretations of the way political scientists are asking the question that differ between men, women and other genders.

This can also be applied to the gendered study of political trust, which although less systematically researched displays mixed evidence. Some show differences in the causes of trust that are a product of socialisation (Schoon and Cheng, 2011), others relate those differences to representation as women exhibit high levels of trust when they live in areas with increased female politicians (Ulbig, 2007). However many papers find gender insignificant in their models, regardless of whether they are intended as an explanatory or control variable, and the only consistent finding is one of inconsistency. As Reinhardt describes: “Studies contrastingly find political trust to be higher among women (Christensen and Lægreid, 2005), lower among women (Alesina and La Ferrara, 2002), or either higher or lower depending on the target of trust (Reinhardt, 2015)” (2019, p. 2567). Nevertheless, what this points to is that an extension of the concept of trust into a family that includes mistrust and distrust is equally likely to result in observed gender differences empirically, and perhaps even conceptually. This paper aims to unpack the nature of any such gaps by focusing on both concept and question interpretation in order to establish the validity of our definitions of trust, mistrust and distrust, and the most effective ways of measuring them.

Materials and Methods

In order to identify whether citizens relate to and understand the expanded family of trust, and to test the efficacy of new questions, we need to not only be able to observe people’s responses, but also their reasonings and interpretations. Qualitative methods are particularly suited for this task. We use focus groups and design an exercise that identifies these understandings without directly asking participants what each concept means to them. Moreover, to explore how these interpretations are operationalised and manifest as responses, they are tested with quantitative survey responses. Before proceeding, it is important to note that there are issues in considering gender as binary (see Schneider and Bos, 2019), but unfortunately these were the only recruitment categories for the focus groups. In the quantitative survey, eight respondents did not identify with either pre-specified gender and their analysis is contained in the Appendix.

We ran a series of ten focus groups in towns and cities across England between 27th May and 16th July 2020 with between five and nine participants each. Our original intention had been to hold the groups face-to-face, touring the country to hear what Leave and Remain supporters in different places had to say about trust, mistrust and distrust, and how they made judgements about who to trust. However as the global crisis hit, we reformulated the group discussions to include trust in the context of COVID-19. Additionally, this meant the focus groups were eventually conducted online. Out of 75 participants, 39 were women and 36 were men. There was a balanced binary gender mix in each group, and as such the other demographic categories of age, social grade are equally represented in each gender.

For the focus group task we created three different personas that were identified using gender-neutral names—Alex, Chris, and Charlie. Each of these characters sees government in different ways, and although we did not provide our participants with this piece of information, represents a definition of trust, mistrust and distrust, respectively:

1. Alex believes the government will generally act on their behalf and in their interests (our definition of trust)

2. Chris believes the government may not act on their behalf and in their interests but will modify that judgement to confirm trust or otherwise according to information and context (our definition of mistrust)

3. Charlie believes that the government will not act on their behalf and will prioritize the interests of themselves or others (our definition of distrust)

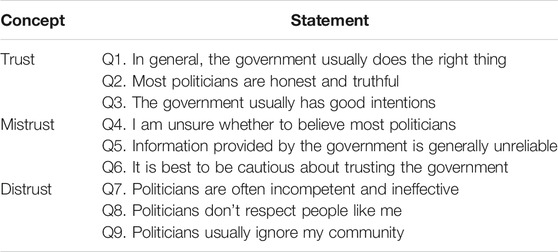

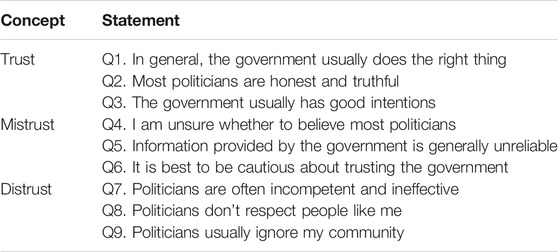

We then showed the participants a series of nine statements (Q1 through to Q9 in Table 2), which corresponded to survey questions used to assess levels of trust, mistrust, and distrust. We asked participants who they thought might have said each statement out of Alex, Chris or Charlie. The participants then picked one or more persona(s) and most of the time gave a justification, elaborating on their understanding of both the statement and personas. If the statements correctly capture each of the concepts, participants would attribute Q1-Q3 to Alex, Q4-Q6 to Chris and Q7-Q9 to Charlie. Interestingly, only two participants out of the 75 noted that these personas could be female, with most assuming they were men, which is reflected in the majority of the quotes presented below.

According to Cyr (2014), Cyr (2017), Cyr (2019), the main strength of focus groups as a social science method is in its ability to generate data at three levels of analysis: 1) at the individual level, most appropriate for triangulating other methods; 2) at the group level, most appropriate as a pre-test for assessing measurement validity; and 3) at the interactive level, most appropriate for exploration. In this paper we rely more specifically on the individual and group levels. We analysed the pseudonymised transcripts of all ten focus groups and coded answers using the NVivo software in two waves: a first wave followed our trust family framing in identifying which persona or concept was attributed to each statement. We then inductively collected every justification offered by the participants in this process and identified recurring themes and conceptualisations of the concepts of trust, mistrust, and distrust. The answers were then coded again using these new categories. Through this inductive analytical framework, we analysed the data along three main axes: we looked for areas of consensus within and across the groups around the themes that emerged in participants’ answers; we identified areas where men and women provided similar and diverging answers; we examined the constructions of trust positions and perspectives along the gender divide. The fact that gender differences were observed in mixed-gender focus groups strengthen our subsequent argument. Indeed this speaks to one criticism traditionally levelled at focus group research, ecological validity, or whether data is susceptible to the environment in which its collection takes place (Cyr 2019, p. 32–33). Focus groups can produce “situated accounts” in which participants are asked to consider questions in an artificial setting. Finally participants may face pressures or forces that can affect how they respond (may feel censored, groupthink, etc.) (Cyr 2017, p. 1038). Delli Carpini and Williams (1994) argue that the group setting is less natural than in true ethnographic approaches, that the amount of information gleaned from individual is not as deep as in individual interviews and that interpretations can be biased by the researcher’s expectations. However, there are ways to mitigate these weaknesses and characteristics that counter-balance them. Indeed bias can be mitigated by the fact that once questions are asked, participants talk to each other in their own language, rather than responding to the researcher’s (Delli Carpini and Williams 1994, p. 62). In this sense organizing gender-specific groups might have exacerbated differences, when those are evident even in spite of the diverging opinions within each group.

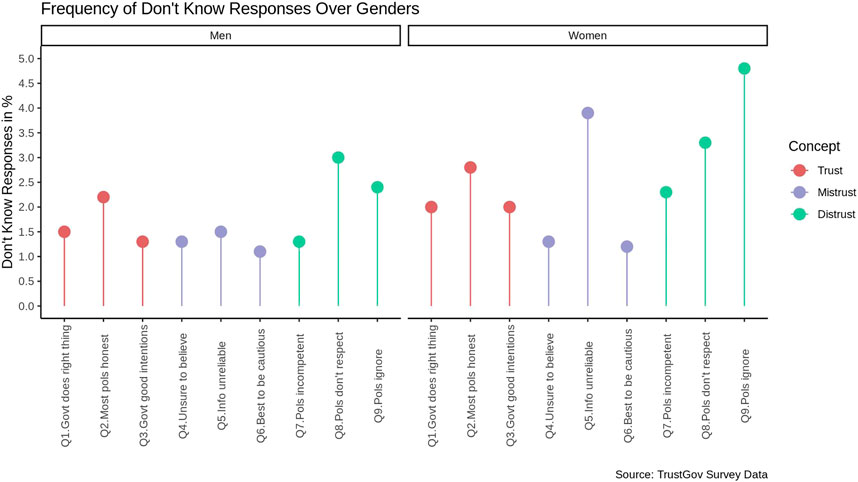

These statements presented in the focus groups were also asked as questions in a quantitative survey, fielded in the United Kingdom between 18 and 19th May 2020 using Ipsos MORI’s online panel. Responses from 1,167 adults were collected as part of a series of attitudinal questions on trust, political behaviors and the Coronavirus pandemic. For the particular battery relating to the concepts of trust, mistrust and distrust, responses were given on a five point scale with a Don’t Know option. The sample contains 52.5% women and eight people identified as non-binary. There is a normal distribution of age, ranging from 18 to 90 years old, and various socioeconomic grades are represented in the data.

We first compare the frequency of responses between binary genders across the nine statements using Camer’s V test of association in a contingency table and by plotting the proportion of Don’t know responses. This serves to highlight any disparities in understanding. We then empirically test whether these statements represent distinct factors by conducting exploratory factor analyses (EFAs), following Devine et al. (2020, see also Kim and Mueller, 1978; Gelman and Hill, 2006). However, we take a step further by also running EFAs separately for those who identify as male, and those who consider themselves female, respectively. If the statements correctly and consistently capture the concepts which they intend to, we should see three factors emerge from each analysis, and Don’t Know responses will not substantively vary.

We combine insights from both methods to draw on the strength of each and mitigate respective weaknesses. Findings from focus groups outline reasoning processes, choice justifications and a deeper look at participants’ judgement making. We then rely on findings from the surveys to operationalise our qualitative analysis and provide evidence of external validity for those findings. In this way, we are able to evaluate gendered conceptualisations using the qualitative data and gendered operationalisations using quantitative data.

Gendered Perceptions of Trust, Mistrust and Distrust in Focus Groups

Conceptualisations

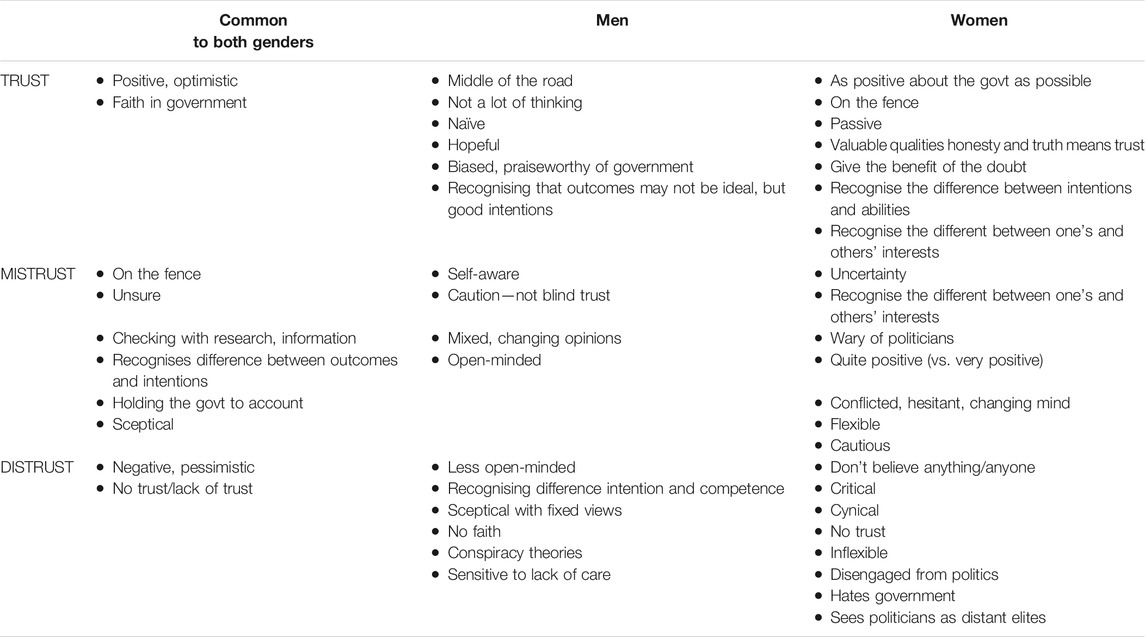

In this section, we present our findings in answer to our first research question: 1) how citizens perceive the concepts of trust, mistrust and distrust and how gendered these perceptions are. To do so, we present the results from our analysis of how focus groups participants perceive the different personas presented to them as part of the exercise: Alex, who is expressing trust in the government; Chris, who is expressing mistrust and Charlie, distrust. These conceptualisations are inferred from the justifications participants provided in the process of ascribing each of the statements to a persona. In other words each time we asked participants to identify a persona, we asked whether the statement signified an expression of trust, mistrust, or distrust. In this section we focus on the justifications participants offered of why a statement was attributed to Alex were coded as trust, and the same for Chris as mistrust, and Charlie as distrust. We focus on the matching of statements to personas in the following section. This enabled us to extract the conceptual associations that participants have with each concept beyond the persona. Table 3 shows a summary of the conceptualisations, for all participants, and by gender. Statements were often attributed to more than one persona and were therefore coded for both. When we combine all these mentions, we begin to get a picture of how these concepts were interpreted by the participants overall, and find some differences by gender.

For the concept of trust, for example, we see that it was mainly perceived as positive and optimistic, as having faith in the government by both men and women. However women were more likely to associate it with a notion of uncertainty, or “sitting on the fence”, as many pointed out during the group discussions. They also associate it with related conceptualisations of “giving the benefit of the doubt”, being cautious or sceptical, and wary of politicians. For instance:

MARTHA1: Well, the government usually has good intentions. I think with Alex, because yes, he generally will believe what the government are saying, and obviously act on their behalf, but it would be more in their interests. So, I think he’s a bit on the fence still, but kind of gives them the benefit of the doubt. (Female, FG7)

Overall, women were more likely to evaluate Alex positively, or as indicative of the right way to think about the government:

BELLA: Yes, if I had to pick one, I would say Alex, but I would say that all of them could say that, because regardless of what you think about the government, it is best to be cautious about them, whether you believe that they’ll act in your best interests, or you absolutely disagree with that and you don’t think they’re going to act in your best interests. (Female, FG7)

Men on the other hand were more likely to recognise a difference between various needs and interests across society. For example:

FINLEY: Basically, generally, they act in the majority of people’s best interests. During COVID, they’ve helped as many people as they possibly can. I’ve not been particularly well off because I’ve got a business that’s suffered dramatically, but in general, the vast, vast majority of people have had the support they needed. (Male, FG5)

Moreover, they were generally more likely to judge Alex as biased or naive.

LIAM: I just think, you know, clearly this person is-, well, no, that actually was probably slightly unfair and slightly harsh of me, but this person clearly has a positive view of government, positive view, and doesn’t bother to ask questions, so is quite trusting. So, you want to go, “Bless,” and pat them on the head. (Male, FG6)

RORY: [justifying an answer of Alex to the statement “most politicians are honest and truthful”] I think Chris seems the most objective and unbiased out of all of these. And that statement there is not from someone who is unbiased and objective. I think the person that said that is more likely to kind of be... to say anything generally positive about the government. (Male, FG2)

For the concept of mistrust, the idea of sitting on the fence, being unsure or undecided was the most prevalent for both men and women. However, women were far more likely to equate the persona of Chris (who was indeed designed to express mistrust in the government) with this perspective:

SIENNA: No, I was saying I think the statement has some sort of uncertainty about it, and Charlie is definitely certain about what he is saying, whereas Chris believes that the government may not, but he could change his mind, so there is that uncertainty with him or her. (Female, FG4)

Women presented a wide range of conceptualisations related to uncertainty, such as being hesitant, wary of politicians, having changing opinions. They highlighted the fact that the idea of mistrust has a dynamic, iterative element that is perhaps more difficult to capture. Many women answered as though this process signified uncertainty, whereas more men perceived it as a sound strategy when thinking or talking about politics, emphasising the need to check with information:

JACOB: Yes, exactly the same, really. In terms of modifying, yes, I think that seems, sort of, like taking things reasonably. So, sort of, checking the government, which, yes, is what you want to do, I think. Of the three, I’m probably Chris, but I know that’s not the question. (Male, FG3b)

Men also were more likely to emphasise the discrepancies between intentions and outcomes, and cautious scepticism meant as understanding how the government works:

HARRY: I’m a bit on the fence as well, on this one, because if it’s a specific politician, some of them do have your best interests, but they get kiboshed down by everybody else, so it’s not like it’s the government as a whole. (Male, FG1b)

For the concept of distrust, both men and women saw it as negative, but more women were disparaging of the Charlie persona, as expressed in the following exchange or the various statements by IVY:

FLORENCE: I just think it’s negative ninny again.

Moderator: What, Charlie’s negative ninny?

FLORENCE: Yes. (Female, FG5)

---

IVY: Doesn’t seem like he trusts anyone does he? He’s a bit of a cynic our Charlie.

IVY: Well it’s our cynic again isn’t it? He doesn’t believe anyone. I don’t want to meet Charlie. (Female, FG1)

In this sense, this perceived lack of trust, or faith even, was understood as very negative and perhaps not desirable. A smaller number of women however emphasised that it illustrated a belief that politicians are not like them:

BELLA: Again, I don’t feel like he’s got any trust in the government whatsoever. It’s as if he feels like it’s not filtering down to the little people like us. The politicians don’t know. It’s like somebody said before, the politicians have never had a normal job, they’ve gone into politics from the age of nineteen, so how can they respect our opinions, if they’ve never lived our lives? So, I feel like Charlie would be the type of person to say something like that. (Female, FG7)

Women were also more likely to associate the Charlie persona with uncertainty, although this seems mainly due to the qualifiers used in some of the questions, as considered in the wider discussion below. Men on the other hand were more likely to identify with this persona.

LOGAN: I started off as Chris I think, but I think I’m getting dragged into Charlie. (Male, FG6)

DYLAN: I think just through experience of what I’ve seen, the “in it for themselves” attitude that I’ve seen from them. It’s a difficult one, because I know it’s a negative opinion and I’d like to be a lot more hopeful in the government, it’s just that they seem to go from, excuse me, one shitshow to another. (Male, FG7)

Measuring the Trust Family

Next we turn to the analysis of the second component of the exercise to evaluate the validity of our survey questions as effective measures of the family of trust. Recall, an effective measure is one which captures each of the relevant concepts across genders in a consistent way.

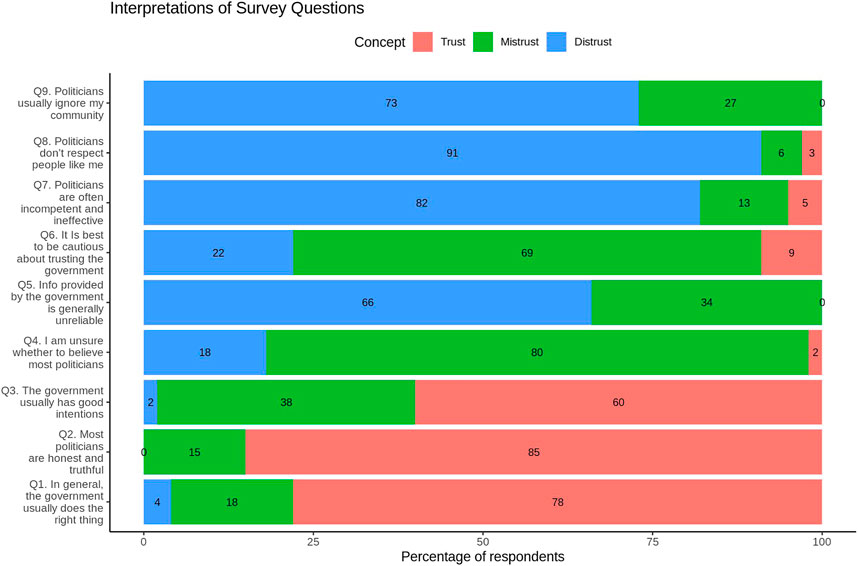

Whilst it can be debated what constitutes an acceptable amount of error, overall the concepts appear to perform quite well when considering the whole focus group population as in Figure 1. Q1-3, designed to measure trust, are correctly assigned by 78, 85 ,and 60% of participants, respectively. Q7-9, intended to measure distrust, are correctly assigned by 82, 91, and 73% of the participants respectively. Mistrust is correctly identified from Q4 and Q6 by 80 and 69% of the participants. Apart from the case of Q5, the majority of respondents therefore correctly assign the statement to the persona.

Some of the gendered differences around mistrust more specifically seen when comparing interpretations in Figure 2, however, are masked when pooling respondents this way. Indeed, all of the mistrust statements demonstrate substantive differences in interpretation between men and women, up to 29 percentage points with an average of 18% difference in this concept.

The emboldened statements Q1, 4, 5, and 6 in Table 4 are those where we observed significant gender differences in interpretation. We develop our reflections on those in more detail below.

The Q5 statement highlighted in grey in Table 4 was considered an indicator of mistrust when designed but interpreted overall as a sign of distrust by participants. However, it is interesting to note that men overwhelmingly ascribed the notion of distrust to this question whereas women were far more split, with a very small majority identifying it as an indicator of distrust.

Trust: Q1. In General, the Government Usually Does the Right Thing

For this question, 87% of women across the focus groups found it to be an indication of trust, but only 67% of men did. Conversely, 25% of men interpreted it as mistrust. The largest discrepancy revolves around the fact that more women see this as a positive, optimistic statement supportive of the government:

ROSIE: Because Alex believes the government will generally act on his behalf, so he thinks, in general, the government usually does the right thing because I think he’s quite optimistic about government competency. (Female, FG3b)

BELLA: Yes, I just think that Alex has got a positive opinion of the government, so he believes that usually they do the right thing. (Female, FG7)

Men are more likely to see it as evidence of an understanding that the “right thing” might be for other groups in society, a reflection of how the government functions:

MYLES: So, I think, if you’re quite self aware, you might realise that acting on your behalf isn’t always the best thing in general, so you might not always come out on top... You might not always win, but it still might be the right thing to do in the context. I think if you’re quite moderate, you can see that and understand that and accept that, and realise that sometimes you become the winner and sometimes you’re less of a winner. (Male, FG8)

Mistrust: Q6. It Is Best to Be Cautious About trusting the Government

Three quarters of the men equated this question with distrust, but only just under two thirds of the women did. This is mainly because a greater number of women equated a position of uncertainty with trust:

AMELIA: Yes, I was. Yes, I was going to think that, because actually, there could potentially be some sort of positivity in that statement because it’s, like, you’re saying it’s best to be cautious. So, you’re not saying, like, you don’t trust the government, but just saying to people, you know, it’s best to be cautious, and that almost suggests that you research or that you consider other points of view, rather than being a really negative statement. So, yes, I flitted between Alex and Chris for that reason. (Female, FG1b)

Although other women associated this statement with mistrust, also in terms of caution, or the need to be wary of politicians:

DARCIE: I’m just reading through, it believes the government may not act on-, you see, the fact that it says, “May not act on their behalf,” which has a trust issue, and “in their interests”. So, I think from Chris’s statement, I think he’s actually saying we need to be more cautious of them. He isn’t dismissing them totally, he’s just saying we need to be cautious, and that, from Chris’s statement, that’s what I feel. (Female, FG5)

ISABEL: Yes, I just think because he’s saying you kind of need to be a bit wary of it, but he’s not definitely saying that they’re not going to do what you want. You just have to kind of take it with a pinch of salt, really. (Female, FG2b)

Men were more likely to highlight mistrust and the need to check with one’s own information, which seems closer to an original view of mistrust as vigilance, or suspending of belief until further information:

LENNY: Yeah, I think if I tie the words caution and what Chris believes he is sitting on the fence, and therefore he might need to go off and do his own research and work out what’s right for him. (Male, FG1)

LIAM: Again, it’s that analysis, so it is, that he obviously looks at politics and analyses and questions further. He’s not fixed. (Male, FG6)

Mistrust: Q4. I am Unsure Whether to Believe Most Politicians

Almost 90% of the women in our focus groups identified this as an expression of mistrust, but only 70% of the men did, as the remaining 30% viewed is as illustrating distrust. It would seem that men across the groups viewed this position as rather negative, representing an absence of faith, trust or optimism:

LEO: Again, it’s super negative, isn’t it? Like, you know, “I’m unsure whether to believe most of the guys I’m sitting with right now.” It’s not a party I want to be a part of. So, again, they’re putting themselves first. It’s just, you know, it’s like a bunch of lies, okay, great. (Male, FG2b)

MYLES: I just think that you’re brazenly saying you don’t think most politicians are believable. I suppose it’s where I’m separating a politician and the government, so like, he’s saying on the whole, the government isn’t trustworthy, so he’s saying most politicians won’t be trustworthy really, in my eyes. (Male, FG8)

Whereas women emphasised the uncertainty of the position:

SIENNA: No, I was saying I think the statement has some sort of uncertainty about it, and Charlie is definitely certain about what he is saying, whereas Chris believes that the government may not, but he could change his mind, so there is that uncertainty with him or her. (Female, FG4)

Mistrust: Q5. Information Provided by the Government Is Generally Unreliable

This is one of the questions that split most of the participants along gender lines. 82% of men associated the statement with distrust, but only 52% of the women did. This was primarily due to the negative connotation of the word “unreliable” which was interpreted in similar ways across genders, although far more often by the male participants:

LEO: Again, it’s quite a negative statement, that, isn’t it? “Information provided by the government is generally unreliable,” which doesn’t sound-, I mean, obviously it’s just negative, you know? It’s like imagine me going to meet my mate and he’s probably not going to show. I’m not going to go, am I? Charlie’s the most negative one there, and to me, that’s a really negative statement, so it just fits hand in hand with Charlie, in my opinion. (Male, FG2b)

AMELIA: Again, you know, it’s quite, it sounds relatively negative, doesn’t it? “Unreliable”, and yes, he doesn’t think the government’s going to act on his behalf, so “generally unreliable”? Yes, I mean, I could have leaned a bit towards Chris, I guess, but no, to make a-, yes, Charlie. Yes, I would make the decision with Charlie. (Female, FG1b)

As mentioned previously, 48% of women associated it with mistrust and the notion of checking with additional information, or the notion of flexibility:

GEORGIA: He sounds well versed, he sounds like he’s done his research, because he says the government may not act on their behalf, but he modifies it by the information and context, which sounds like he looks into it or he’s invested in it. So, he sounds like he makes decisions based on what information he gets, rather than just his feelings. (Female, FG7)

PENNY: So where she said he’s saying, “Generally unreliable,” so, generally meaning most of the time, but sometimes he’s flexible with that according to maybe what he believes in or what he stands for. (Female, FG8)

Qualifiers in the Question

One theme which emerged that can explain these gendered differences is the interpretation of qualifiers as part of the statement. When men noted the qualifiers in the questions, “usually” and “generally” were mostly interpreted as “all the time”:

GEORGE: Because it uses the word “usually”, so maybe they think their viewpoint from the past or so forth is that they don’t follow through, so that's why it says “usually has good intentions”. You can see it as a passing remark. (Male, FG1b)

NATHAN: Yes, I think that you can kind of dwell on the “usually”, but I think if you just go, “Yes, people usually ignore my community,” then that’s just a straight-up no. You know, it’s more like a 100%, “We never get a look in,” type thing and that, for me, is just a straight Charlie thing to say. (Male, FG2b)

LEON: For me, the clue’s in the wording, you know, “in general” and “will generally” and “usually”. These are all terms for, like, most of the time, which is what Alex believes in. He’s definitely a glass half full kind of person when it comes to the government. (Male, FG8)

LENNY: Yeah... I think it’s the word “usually”. So I think he’s sitting on the fence. Sometimes he might think that he might be able to get someone out of a politician that relates to his particular area and sometimes he may not.... something. that’s my opinion … I thought too quickly. When I heard “usually” - well has “usually” good intentions... that’s more 60–40 or 70–30... hence why I thought hold on... that’s probably sounds more like Alex than Chris where Chris is probably more 50–50. or is 60 in the middle? (Male, FG1)

A minority saw them as an indication of uncertainty or doubt:

JACK: Chris is in the middle, you know, he basically doesn’t have full trust in the government, he’s, like, in the middle, kind of thing. So, again, “politicians usually ignore my community”, so again, it’s in the middle. Like, politicians could always ignore my community, politicians sometimes or usually. So, he’s in the middle, kind of, “usually”, and he’s kind of in the middle, so he kind of matches those two criteria. (Male, FG1b)

Whereas most of the women interpreted these qualifiers as an indication of doubt:

VIOLET: I mean, the largest thing is that, obviously, the “general” and the “generally” link together, but it’s a very optimistic statement, but it also at the same time, even though it’s optimistic in believing the government most of the time will do the right thing, because of the words “general” and “usually” it still leaves room for the possibility that the government won't always do the right thing. There is still that little possibility, and Alex also agrees with that because the word “generally”, he's saying there is still space for errors. (Female, FG2b)

ALICE: The “may not”, and he’s used the word “usually”, so there’s a chance. He’s also used the word, he could “modify”, but I think it’s Chris, that. (Female, FG6)

ELIZA: Just, like, “usually”, “generally”. “In general, the government usually does the right thing.” It’s still like he's unsure. So, I just think it sits with both Alex and Chris because Alex, it says, “Will generally act on their behalf,” and then Chris believes that the government may not, but if he does his research, he’ll confirm whether he trusts them. (Female, FG7)

SOPHIA: Yeah I did as well... erm... same as LENNY. The “usually”... again on the fence. Right down the middle. (Female, FG1)

And a small minority interpreted it as most of the time.

ISABEL: Yes, I feel like he said that they’ll, like, kind of, generally act in their interests, and in the statement it’s saying “usually does the right thing”, so I just think they link together and they’re more positive than some of the other ones. (Female, FG2b)

Quantitative Analysis

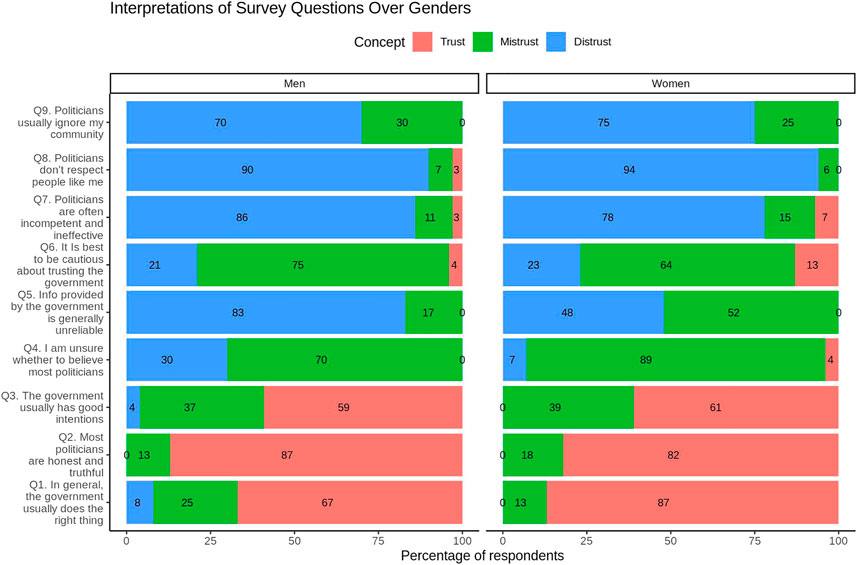

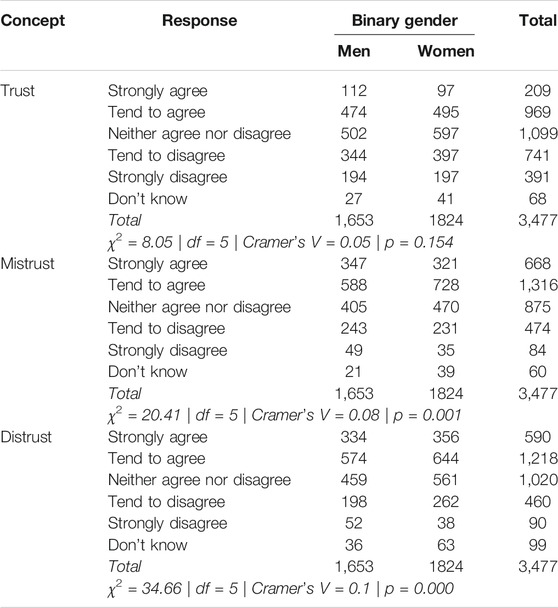

We begin with a summary of responses to these questions by binary gender in the quantitative survey. Please see the Appendix for those who did not identify with either male or female. Table 5 displays contingency tables for responses to each of the three concepts over binary gender. For the concept of trust, the test of association is insignificant and there are roughly equal response frequencies over genders and a normal distribution across the Likert scale. However for the concept of mistrust there is a statistically significant very weak association, indicating that there are gender differences in responses. Women more often agree with the mistrust statements and more commonly answer Don’t know. There is also a weak association across genders for the concept of distrust, where again women more frequently choose the Don’t know option and tend to give less extreme answers than men.

Figure 3 displays the proportion of Don’t Know responses for each question as an indicator of participants’ uncertainty. Reassuringly, the rates are within expected ranges of Don’t Know responses for survey questions, suggesting that participants understood the questions sufficiently. However there are distinguishable gender differences. As is consistent with the literature and the above tests of association, women are more likely to answer Don’t Know overall (Lizotte and Sidman, 2009), but this is particularly true for two of the questions. The first is Q5, which has already been identified as unequally interpreted, and the second is Q9. Interestingly both of these questions include qualifiers, which are “generally” and “usually”, respectively.

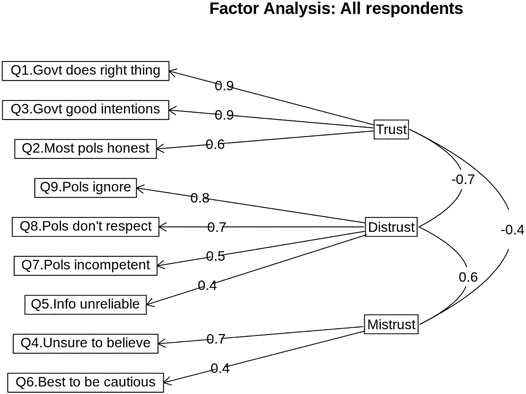

As a final test, we employ EFAs, which use hierarchical regression modelling techniques to identify how many concepts exist in a series of observed variables, in this case a battery of survey response items (see, for example, Kim and Mueller, 1978; Gelman and Hill, 2006). The choice was made to use exploratory rather than confirmatory factor analyses due to expecting gender differences, yet aiming to identify where these exist. First an EFA was run with respondents of all genders, the results of which are displayed in Figure 4. Three concepts are identified, as intended, however one of the mistrust questions loads onto the distrust factor. This is Q5, which corroborates the focus group findings and that of Devine et al. (2020). In addition, this analysis shows that trust is the factor with the strongest loadings, which was also the easiest concept to identify in the personas exercise. Moreover, distrust and mistrust are moderately positively correlated, indicating that they share similarities.

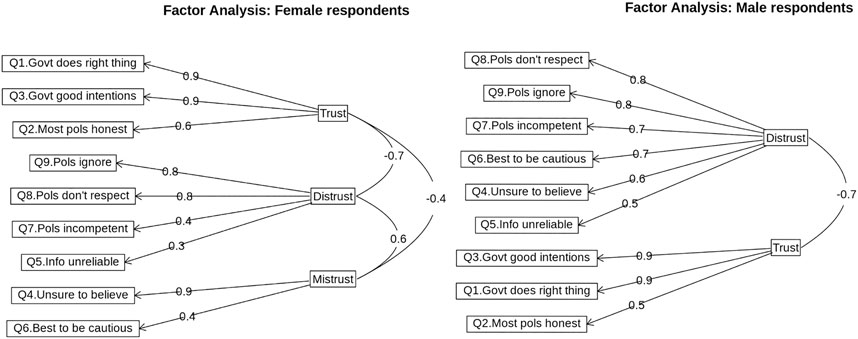

As displayed in Figure 5, we also separate the sample by binary gender and run EFAs. On the left the women’s path graph shows similar results to the analysis of all respondents. Again Q5 weakly loads onto the distrust factor, which is strongly negatively correlated with trust but moderately correlated with mistrust. Surprisingly, however, the men’s EFA identifies only two latent concepts: trust and distrust, meaning mistrust appears not to exist for male respondents. Moreover they load with moderate to strong loadings, indicating this is a non-trivial association, and a robustness test of a male EFA with three factors was unsuccessful.

Discussion

The analysis presented in this paper shows evidence that the concepts of trust, mistrust and distrust are qualitatively different from one another, in answer to our first research question. This confirms previous results (Bertsou 2019; Devine et al., 2020) and adds further credence to the argument that trust requires greater conceptual nuance. Overall trust tends to be interpreted as positive or optimistic, and this concept also had the strongest loadings in all the EFAs; distrust on the other hand is perceived as pessimism, or lack of faith. For both the trust and distrust concepts, our analysis supports the expectations outlined in Table 1. Mistrust however seemed to be less clearly understood, with the main divergence along gender lines. Indeed mistrust was both conceptualised as scepticism, per our original framework, as well as uncertainty. That respondents varied in their agreeing or disagreeing to statements for each concept, and the strength of this agreement, further demonstrates their distinctiveness. When pooling all respondents and performing an EFA, three latent concepts emerge from the survey items.

Additionally, and in answer to our second research question, the analysis shows evidence of gender differences in the understanding and operationalising of the family of trust. Whereas trust tends to be interpreted across the board as positive or optimistic, women are more likely to see it as requiring caution, and men as a naïve judgement. And if distrust is perceived as pessimism or lack of faith across genders, women are more likely to relate it to alienation from politics or politicians, but also express disparaging views of a distrusting attitude, branding it cynical, perhaps unhelpful. Men however are more likely to assess distrust in a positive light and identify with a distrusting attitude. This is corroborated in quantitative responses to survey items, where there appear to be no gender differences in trust, some differences in distrust but the most pronounced differences appear in mistrust.

As indicated above, mistrust seemed to present the deepest split between genders, and away from expectations. Indeed men seem more likely to express the notion of “watchful, questioning caution”, yet across genders the interpretation that occurred most frequently was that of uncertainty or sitting on the fence. This is consistent with existing literature on gender differences in political interest or attitudes whereby women respond differently depending on how the question is asked. It appears that female participants recognised the difference between being questioning and being cynical, which is also reflected in their three factor EFA. However, results from the EFA seemed to indicate that male respondents are more likely equate mistrust and distrust, and perceive them as the same latent concept. In the focus groups however, male participants were more likely to offer the interpretation of mistrust as intended in much of the literature on critical citizenship (Norris, 1999) and sceptical trust of checking facts and information and as such holding the government to account. We return to this apparent inconsistency later in the discussion.

In terms of measurements, and to address our final research question, gender differences were also evident in the interpretations of the questions, particularly in the interpretation of qualifying terms in the question. The focus groups elucidate peoples’ reasoning in their choices and we found that women ascribed certain statements to the mistrusting persona due to perceiving “generally” as implying doubt. Whereas men interpreted the same word as indicative of describing most of the time. This was shown to have ramifications for quantitative analyses, whereby the two questions with the highest rates of Don’t Know responses in women included the qualifiers “usually” and “generally”. Men’s Don’t Know responses did not substantively vary, corroborating their greater propensity to guess (Fortin-Rittberger, 2020).

These subtle language changes play out in the quantitative analysis of the survey. The trust loadings are strong, particularly for describing politicians as “good” or “doing the right thing” -- people intuitively and collectively know what this means; on the other hand, being “honest” is a weaker indicator, or in some way subjectively different. The terms “ignoring” and “not respecting” are universal communicators of distrust. Yet being “unsure’ and “cautious” is identified as mistrust for women, but not for men where it is the same latent concept as “ignoring”; it could be that men instead pick up on the word “believe” in Q4’s statement instead and associate it with being truthful. Particularly in Q5 Information provided by the government is generally unreliable there is something about the combination of “generally” as a qualifier and “unreliable” as an adjective which confuses participants and makes them more likely to associate the statement with distrust. If nothing else, this question needs removing from the battery, but it is clear that individual words have powerful implications for research.

We can identify three possible explanations for the findings of this research. The first is that there are real behavioral differences between genders. It may be the case that women really are more cautious, especially about politics or politicians in a system where they do not see themselves represented as often, or that values characteristics that are different to theirs. Moreover, it could be that men are less likely to be mistrusting and therefore find the concept difficult to recognise. However this is not supported by the qualitative analysis presented above. So, when genders interpret differently, as demonstrated in the focus groups, we cannot be sure that observed survey response differences are due to gendered attitudes or behaviors. That is, there may not be a gender gap in trust, knowledge, or some other political phenomena; instead there may be a gender gap in the interpretation of the meaning behind the question asked.

Indeed, the second explanation could be one of measurement problems. The results, particularly considering the qualifiers in statements and subtle differences in wording, seem to indicate that men and women do interpret these measures rather differently. We suggest further work is needed to manipulate these qualifiers, for example, substituting “usually” for “sometimes”, to test whether this more accurately conveys mistrust as a temporary or occasional disposition. It would also be interesting to follow work in other gendered perspectives on survey methodology (Fortin-Rittberger, 2020) and experiment with the treatment of Don’t Know responses; removing the propensity to guess may mitigate some of the problems highlighted here.

Finally, and the most difficult to address, our findings may be indicative of a conceptual problem. The concept of mistrust, as we have defined and measured it, appears the most elusive to capture effectively. It may be the case that mistrust is not a predisposition and instead is a process by which one eventually arrives at trust or distrust; or it may be somehow substantively different from trust and distrust in another way. The fact that participants systematically distinguished three different constructs suggest some of the conceptual framing outlined in Table 1 holds—the trust family has more than two members. But the focus group data and gendered EFAs point to the need for further work to establish a more robust definition of mistrust. Perhaps the latter concept is more dependent upon context, and therefore requires this context in order to be identified, meaning qualifiers such as “generally” do not work for this concept that is so situationally dependent. Indeed, it may be that mistrust has two separate dimensions. Our analysis shows that it is sometimes interpreted as caution or uncertainty, yet other times it is scepticism or suspicion; whilst Citrin and Stoker (2018) equate these two dimensions, it may be the case that a larger battery and expanded conceptual framework are able to demonstrate these as further members of the trust family. In any case, a reflexive conceptual discourse is required to address this issue.

Conclusion

In this paper we have shown evidence of a possible gender gap in political trust, mistrust, and distrust. Our findings demonstrate qualitative differences that are also replicated in comparable quantitative analysis. We confirm the conceptual validity of the expanded trust family. However, our analysis also highlights important gender differences in the understandings and operationalisation of these three concepts, which may stem from three distinct sources: 1) the existence of real attitudinal and behavioral differences between men and women in their political trust, mistrust or distrust judgements; 2) measurement issues resulting in differing interpretations of survey questions across genders; 3) conceptual issues with the framing of the trust family. Indeed it remains unclear whether the concept of mistrust can be defined as an attitude or a judgement, or whether it should be understood as more of a process intended to reach such a position.

There are however some limitations to our analysis, as well as scope to expand this work in the future. First the focus group participants almost unanimously perceived the personas in the exercise as male; this may have impacted the reasoning processes of the men and women in the groups, and as such the results. This is mitigated by the fact that the same amount of women identified with one of the personas as the men when asked during the discussion. Another limitation of this research is that the data relates to the United Kingdom only, and thus reflect culturally specific perceptions. This may indeed explain in part the different findings of the gendered EFAs from Devine et al. (2020) who use comparative World Values Survey Data for a range of countries. Despite these limitations, our findings offer important contributions to the existing literatures on political trust, and on gender and politics. They highlight the value of such disaggregated exploration of concepts and measures, which could be broadened to include a wider range of characteristics such as age, education, partisanship. One of these is the validation of our call to develop a more systematic mixed methods research agenda on both the expanded family of political trust and gender, emphasising that global comparative work to capture diverse gender effects across different political systems are the necessary next steps for the field.

As the opening quotation to this article indicates, trust scholars are beginning to recognise the idea of a trust family, stretching from trust, through mistrust to distrust. Our work has first been about exploring how to measure these different elements of the trust family; it tests the extent to which they reveal insights about a gendered dimension of to understand how citizens understand the dynamic of trust. Our goal has been to provide building blocks to a broader project, namely to address the question: if a trust family can be detected among citizen attitudes, what are the implications for the operation of (particularly) democratic political systems? The established adage that effective democratic governance and policymaking needs citizens that trust their governors cannot be scratched, but it would seem appropriate to ask whether it needs to be joined by other options. Both mistrust and distrust among citizens can perform positive functions for a polity. Mistrust or more broadly scepticism would seem a highly democratic virtue as it enables citizens to ask tough questions and hold rulers to account and, in some instances, make their own informed judgements about whether to follow their rules. Trust as a value for democratic governance is, as Levi (1998) argues, only the basis for contingent consent and compliance and its withdrawal could serve as much of a benefit as its maintenance, given the underlying issue is not whether citizens trust but whether their governance is in their view trustworthy. Even distrust is a more beneficial than damaging to democracies if its presence reflects a failure of the part of governors to act in a trustworthy way. An effective system of democratic governance then might require some mix of mobilised trust, mistrust and distrust to function in a way that broadens the interests it serves.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because The data from both the focus groups and quantitative survey are part of the ongoing TrustGov project. The project plans to deposit data with the United Kingdom Data Archive upon its completion. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to www.trustgov.net.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Southampton. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This research was supported by an award from the ESRC’s United Kingdom in a Changing Europe programme and by the ESRC grant “Trust and Trustworthiness in National and Global Governance” (ES/S009809/1).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Paul Carroll, Holly Day, Glenn Gottfried and Liv Bailey of Ipsos MORI for their organisation and facilitation of the focus groups.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.642129/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1All the names of focus groups participants have been pseudonymised.

References

Alesina, A., and La Ferrara, E. (2002). Who Trusts Others? J. Public Econ. 85 (2), 207–234. doi:10.1016/S0047-2727(01)00084-6

Almond, G. A., and Verba, S. (1963). The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. Princeton: Princeton University Press. doi:10.1515/9781400874569Available at: (Accessed December 14, 2019).

Bertsou, E. (2019). Rethinking Political Distrust. Eur. Pol. Sci. Rev. 11 (02), 213–230. doi:10.1017/S1755773919000080

Burns, N. (2008). “Gender in the Aggregate, Gender in the Individual, Gender and Political Action,” in Political Women and American Democracy. Editors C. Wolbrecht, K. Beckwith, and L. Baldez (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 50–63. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511790621.006

Campbell, R. (2012). What Do WeReallyKnow about Women Voters? Gender, Elections and Public Opinion. Polit. Q., 83 (4), 703–710. doi:10.1111/j.1467-923X.2012.02367.x

Campbell, R., and Kristi, W. (2008). Understanding Men's and Women's Political Interests: Evidence from a Study of Gendered Political Attitudes. J. Elect. Public Opin. Parties 18 (1), 53–74. doi:10.1080/17457280701858623

Christensen, T., and Lægreid, P. (2005). Trust in Government: The Relative Importance of Service Satisfaction, Political Factors, and Demography. Public Perform. Manage. Rev. 28 (4), 487–511. doi:10.1080/15309576.2005.11051848

Citrin, J., and Stoker, L. (2018). Political Trust in a Cynical Age. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 21 (1), 49–70. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-050316-092550

Cyr, J. (2014). The Pitfalls and Promise of Focus Groups as a Data Collection Method. Sociol. Methods Res. 45 (2), 231–259. doi:10.1177/0049124115570065

Cyr, J. (2017). The Unique Utility of Focus Groups for Mixed-Methods Research. Apsc 50 (4), 1038–1042. doi:10.1017/S104909651700124X

Cyr, J. (2019). Focus Groups for the Social Science Researcher. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781316987124

Dalton, R. J., and Welzel, C. (2014) The Civic Culture Transformed: From Allegiant to Assertive Citizens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139600002

Delli Carpini, M. X., and Williams, B. (1994). The Method Is the Message: Focus Groups as a Method of Social, Psychological, and Political Inquiry. Res. Micropolitics 4, 57–85.

Devine, D., Gaskell, J., Jennings, W., and Stoker, G. (2020). Exploring Trust, Mistrust and Distrust. (Accessed November 10, 2020).

Diekman, A. B., and Schneider, M. C. (2010). A Social Role Theory Perspective on Gender Gaps in Political Attitudes. Psychol. Women Q. 34 (4), 486–497. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2010.01598.x

Dow, J. K. (2009). Gender Differences in Political Knowledge: Distinguishing Characteristics-Based and Returns-Based Differences. Polit. Behav. 31 (1), 117–136. doi:10.1007/s11109-008-9059-8

Easton, D. (1975). A Re-assessment of the Concept of Political Support. Br. J. Polit. Sci 5 (4), 435–457. doi:10.1017/S0007123400008309

Eckel, C. C., and Grossman, P. J. (2008). “Chapter 113 Men, Women and Risk Aversion: Experimental Evidence,” in Handbook of Experimental Economics Results. Editors C. R. Plott, and V. L. Smith (New York, NY: Elsevier), 1061–1073. doi:10.1016/S1574-0722(07)00113-8

Fortin-Rittberger, J. (2020). Political Knowledge: Assessing the Stability of Gender Gaps Cross-Nationally. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 32 (1), 46–65. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edz005

Fraile, M. (2014). Do Women Know Less about Politics Than Men? the Gender Gap in Political Knowledge in Europe. Soc. Polit. Int. Stud. Gend. State. Soc. 21 (2), 261–289. doi:10.1093/sp/jxu006

Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The New Foundations of Global Prosperity. 28th ed. edition. New York: Free Press.

Gambetta, D. (2000). “Can We Trust Trust?,” in Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations (Oxford: Blackwell).

Gelman, A., and Hill, J. (2006). Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511790942

Gutteres, A. (2020). Remarks to the General Assembly on the Secretary-General’s Priorities for 2020, United Nations Secretary-General. Available at: https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/speeches/2020-01-22/remarks-general-assembly-priorities-for-2020 (Accessed December 14, 2020).

Jennings, W., Stoker, G., Valgardsson, V., Devine, D., and Gaskell, J. (2021). How Trust, Mistrust and Distrust Shape the Governance of the COVID-19 Crisis. J. Eur. Public Policy 1–23. doi:10.1080/13501763.2021.1942151

Karmis, D., and Rocher, F. (2018). Trust, Distrust, and Mistrust in Multinational Democracies: Comparative Perspectives. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press. Available at: (Accessed December 14, 2020).

Katz, J. (2016). Man Enough?: Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton, and the Politics of Presidential Masculinity. Northampton, United Kingdom: Interlink Books.

Kim, J., and Mueller, C. (1978). Factor Analysis: Statistical Methods and Practical Issues. India: SAGE Publications. doi:10.4135/9781412984256

Lenard, P. T. (2008). Trust Your Compatriots, but Count Your Change: The Roles of Trust, Mistrust and Distrust in Democracy. Polit. Stud. 56 (2), 312–332. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00693.x

Levi, M., and Stoker, L. (2000). Political Trust and Trustworthiness. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 3 (1), 475–507. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.475

Levi, M. (1998). “A State of Trust,” in Trust and Governance. Editors V. Braithwaite, and M. Levi (New York: Russell Sage Found), 77–101.

Lizotte, M.-K., and Sidman, A. H. (2009). Explaining the Gender Gap in Political Knowledge. Pol. Gend. 5 (2), 127–151. doi:10.1017/S1743923X09000130

Merkel, W. (2014). Is There a Crisis of Democracy? Democratic Theor. 1 (2), 11–25. doi:10.3167/dt.2014.010202

Norris, P. (1999). Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government, Critical Citizens. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available at: (Accessed December 14, 2020). doi:10.1093/0198295685.001.0001

Norris, P. (2011). Democratic Deficit: Critical Citizens Revisited. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511973383

Putnam, R. D. (1993). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Shuster. Available at: (Accessed December 17, 2019).

Reinhardt, G. Y. (2015). First-Hand Experience and Second-Hand Information: Changing Trust across Three Levels of Government. Rev. Pol. Res., 32(3), 345–364. doi:10.1111/ropr.12123

Rudman, L. A., Moss-Racusin, C. A., Phelan, J. E., and Nauts, S. (2012). Status Incongruity and Backlash Effects: Defending the Gender Hierarchy Motivates Prejudice against Female Leaders. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 48 (1), 165–179. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2011.10.008

Sartori, L., Tuorto, D., and Ghigi, R. (2017). The Social Roots of the Gender Gap in Political Participation: The Role of Situational and Cultural Constraints in Italy. State. Soc. 24 (3), 221–247. doi:10.1093/sp/jxx008

Schneider, M. C., and Bos, A. L. (2019). The Application of Social Role Theory to the Study of Gender in Politics. Polit. Psychol., 40 (S1), 173–213. doi:10.1111/pops.12573

Schoon, I., and Cheng, H. (2011). Determinants of Political Trust: A Lifetime Learning Model. Dev. Psychol. 47 (3), 619–631. doi:10.1037/a0021817

Sniderman, P. (2017). The Democratic Faith: Essays on Democratic Citizenship. London, United Kingdom: Yale University Pres. doi:10.23943/princeton/9780691154145.003.0005

Ulbig, S. G. (2007). Gendering Municipal Government: Female Descriptive Representation and Feelings of Political Trust. Social Sci. Q 88 (5), 1106–1123. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6237.2007.00494.x

Uslaner, E. M. (2017). “The Study of Trust,” in The Study of Trust. Editor E. M. Uslaner (Oxford University Press). doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190274801.013.39

van der Meer, T. W. G., and Zmerli, S. (2017). “The Deeply Rooted Concern with Political Trust,” in Handbook on Political Trust (Edward Elgar Publishing). Available at: https://doi.org/10.4337/9781782545118.00010 (Accessed December 5, 2020)

van der Meer, T. W. G. (2017). ‘Political Trust and the “Crisis of Democracy”’. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.77 (Accessed November 06, 2020)

Yavorsky, J. E., Kamp Dush, C. M., and Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J. (2015). The Production of Inequality: The Gender Division of Labor across the Transition to Parenthood. Fam. Relat., 77 (3), 662–679. doi:10.1111/jomf.12189

Keywords: political trust, gender, question interpretation, mixed methods, political mistrust, political distrust, focus groups

Citation: Bunting H, Gaskell J and Stoker G (2021) Trust, Mistrust and Distrust: A Gendered Perspective on Meanings and Measurements. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:642129. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.642129

Received: 15 December 2020; Accepted: 22 June 2021;

Published: 06 July 2021.

Edited by:

Andrea De Angelis, University of Lucerne, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Jasmine Lorenzini, Université de Genève, SwitzerlandEmily Rainsford, Newcastle University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2021 Bunting, Gaskell and Stoker. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hannah Bunting, aC5qLmIud2lsbGlzQHNvdG9uLmFjLnVr

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Hannah Bunting

Hannah Bunting Jennifer Gaskell

Jennifer Gaskell Gerry Stoker

Gerry Stoker