- Department of Political Science, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Despite greater responsibility being passed to local and regional tiers of government in many European countries, we still have limited understanding about what shapes citizens' support for such tiers of government. On the one hand we expect citizens to evaluate local government on its own merits, depending on the performance of local units. Yet in the context of multi-layered governance, we argue that local political support is likely to be at least partly a derivative of attitudes to the national level. The Dutch Local Election Study 2016 offers us the possibility to test these expectations. We show that local political support is mainly (in the case of local democratic satisfaction) or substantially (in the case of local political trust) related to national political support. To the extent that local support is shaped by local evaluations, appraisals of output performance are more important than appraisals of input or throughput performance. There is some evidence that these relations are conditional. Political sophistication increases citizens' sensitivity to local performance. Yet, local embeddedness only modestly reduces citizens' reliance on national-level evaluations.

Introduction

Devolution has become a common process across Europa and in the US (Jennings, 1998; John, 2001; Denters and Rose, 2005; Hooghe et al., 2010). The shift of political and administrative responsibilities from national governments to regional and local governments has increased the executive power at these lower levels. Yet, it is not evident that democratic accountability followed this transfer of political power. To what extent and under which conditions do local citizens evaluate their local government and evaluate local democracy on its own merits?

Citizens express more trust in and satisfaction with politics and democracy at the local level than at the national level (Jennings, 1998; Cole and Kincaid, 2000; Chang and Chu, 2006; Muñoz, 2017). But studies on the factors that help us understand these types of local political support are rather scarce. There is evidence that this support is at least partly driven by evaluations of local performances, services, and embeddedness, either objectively (Rahn and Rudolph, 2005) or subjectively (DeHoog et al., 1990; Denters, 2014; Fitzgerald and Wolak, 2016).

However, the literature on local political support has largely overlooked the relevance of the multilayered government structure in which municipalities are situated (Fitzgerald and Wolak, 2016; Muñoz, 2017). This is remarkable. Studies into support for supranational regimes such as the European Union have put strong emphasis on the importance of support for national government as a benchmark or source for supranational support, consistently finding strong effects (Anderson, 1998; Kritzinger, 2003; Hobolt, 2012; Armingeon and Ceka, 2014; Ares et al., 2017; Torcal and Christmann, 2018). As the nation state continues to be the focal point for democratic attitudes, local, and supranational political support cannot be seen in isolation from the multilevel structure in which it is embedded.

The literature thus suggests two rivaling plausible expectations about the locus of local political support. On the one hand, we would expect citizens to judge local democracy on its own merits, as an evaluation of institutional quality and policy output. On the other hand, there are reasons to expect local political support to be derivative of national political support. Only the first explanation would indicate that municipal responsibilities are directly embedded in a local democratic culture that is a precondition for local representation and local accountability.

This article pits these two lines of inquiry on local political support against each other, with measures of two middle-range indicators of political support: democratic satisfaction and political trust. Our analyses are not meant to identify causal directions, but rather to identify the locus of local political support via its (conditional) relations to local evaluations and national political support. We study the extent to which local political support is rooted in input, output, and throughput performance of local governments (Schmidt, 2013), next to the extent to which it simply reflects national political support (cf. Muñoz, 2017). Furthermore, we test to what extent the strength of these two rivaling interpretations differs by the extent to which citizens are (i) locally embedded and (ii) politically sophisticated.

We employ rich data from the Dutch Local Election Survey of 2016 that were collected for this specific purpose. With multilevel models to control for nesting in municipalities, we find that local political support is based mainly (local democratic satisfaction) or substantially (local political trust) rooted in national political support. To the extent that citizens evaluate local politics on their own merits, evaluation of output performance matters most. Furthermore, political sophistication increases citizens' sensitivity to local performance, while local embeddedness modestly decreases reliance on national political support.

Theory

Local Political Support as an Object-Specific Evaluation

The two interpretations of local political support derive from theoretical assumptions on the constitution of political support. In the first line of reasoning, local political support among citizens derives from local democracy's own merits. Here, local political support is understood to be relational and evaluative. A central paradigm reads that “A trust B do to X” (Hardin, 1999: 26). Citizens (A) evaluate the regime and its institutions (B) on a specific matter (X). Building on this paradigm, the institutional approach to political support focuses its attention to the performances and procedures of the object of support (cf. Martini and Quaranta, 2019).

We can further distinguish between three object-specific explanations of political support: input, throughput, and output, also referred to as government respectively of the people, with the people, and for the people (Schmidt, 2013). Input performance refers to the representative function of political institutions, namely to represent the views of all citizens. The relevance of input traits to political support is found at the macro level of proportional electoral rules (e.g., Aarts and Thomassen, 2008; Marien, 2011) and at the meso-level of citizens' assemblies (Werner, 2020). Output performance relates to (the effectiveness of) policy outcomes, often understood as economic performance (e.g., van Erkel and van der Meer, 2016). Finally, throughput points to “the practices that go on in the “black box” of governance”(Schmidt, 2013: 5). This is commonly summed up as the procedural quality of government, and includes accountability, transparency, and inclusiveness, or – inversely – corruption (Grimmelikhuijsen, 2012; Grimes, 2017; van der Meer, 2017). Input, output, and throughput may be studied via objective, exogenous indicators or via citizens' subjective perceptions and evaluations thereof (Mishler and Rose, 2001; Aarts and Thomassen, 2008). For the purpose of this study, we rely on the subjective perceptions as the minimal requirement for object-specific evaluations.

When we transpose this argument from the national level to local political support, the overarching hypothesis reads that political support at the local level is embedded in evaluations of local input, output, and throughput performance. In other words, citizens are expected to judge local democracy on its own merits. That would be visible in empirical research when local political support is related to local political evaluations.

The literature on local democracies offers some evidence on this relationship, albeit only for output evaluations. DeHoog et al. (1990) show that the perceived quality of city provisions stimulates satisfaction with local government. This is echoed in works by Fitzgerald and Wolak (2016) and Denters (2014). By contrast, input and throughput legitimacy are less well-studied. Nevertheless, a longstanding argument favoring local democracy states that municipalities offer better opportunities for the voice of citizens (Dahl, 1967). Indeed, research shows a negative effect of population size of cities on participation (Oliver, 2000) and trust in local government (Rahn and Rudolph, 2005; Montalvo, 2010; Hansen, 2015). Similarly, citizens mention the linkage function (encompassing representatives, accountability, responsiveness, and transparency) almost twice as often as a reason to trust local government compared to the state and federal government in the United States (Jennings, 1998). In other words, input and throughput legitimacy are likely to matter, particularly at the local level.

All in all, our first set of hypotheses reads:

H1. Local political support is rooted in citizens' positive evaluations of local political performance.

H1a. Local political support is rooted in citizens' positive evaluations of local input performance.

H1b. Local political support is rooted in citizens' positive evaluations of local throughput performance.

H1c. Local political support is rooted in citizens' positive evaluations of local output performance.

Local Political Support as a Derivative of National Support

The rivaling perspective on local political support poses that it is not an object-specific evaluation, but rather derivative of a more diffuse attitude. Although local governments are embedded in a structure of multilevel government, this multilayered component tends to be overlooked when local political support is studied in a vacuum. Only few studies examined the influence of national politics on local political support (Fitzgerald and Wolak, 2016; Muñoz, 2017). These studies, next to a substantively more comprehensive literature on supranational support, propose two mechanisms in which local political support is primarily derived from more general, nationally-oriented political support.

The trust-as-syndrome mechanism (e.g., Harteveld et al., 2013) – also known as the “congruence” (Muñoz et al., 2011) or “equal assessment” model (Kritzinger, 2003) – states that people have a general attitude toward the political system that informs their attitude toward different polity levels (Anderson, 1998). This general attitude may itself be rooted in social (interpersonal) trust (Zmerli and Newton, 2017) or psychological predispositions (Harteveld et al., 2013; Ares et al., 2017).

The cue-taking mechanism suggests that people use their perceptions of national politics as a heuristic (cue, proxy) when they are asked about less salient levels of government. Anderson (1998: 576), for instance, argues about support for the European Union: “Citizens compensate for a gap in knowledge about the EU by construing a reality about it that fits their understanding of the political world. For most people, this means that they rely on what they know and think about domestic politics.” Many studies on the European Union have argued that citizens employ the national level as such a heuristic (Anderson, 1998; Rohrschneider, 2002; Kritzinger, 2003; Hobolt, 2012; Harteveld et al., 2013; Armingeon and Ceka, 2014; Torcal and Christmann, 2018).

The crucial – but in this paper untestable – difference between trust-as-syndrome and cue-taking, is that the latter assumes a hierarchical ordering of levels of government in public opinion. The national political level is the first-order polity in terms of the attention citizens pay to the political dynamics, and the knowledge they have about it. Other polity levels, such as the supranational and the municipal are secondary (De Blok et al., 2020), as has been long recognized in electoral research on local and regional elections (Heath et al., 1999; Rallings and Thrasher, 2007; Marien et al., 2015). Yet, both mechanisms suggest a strong relationship between national and local political support. Ultimately, both mechanisms lead to the same hypothesis:

H2. Local political support is rooted in citizens' national political support.

Building on the literature on support for the European Union (e.g., Harteveld et al., 2013; for an overview see Muñoz, 2017), we expect that local political support is related to national political support more strongly than in object-specific evaluations of local democracy's input, throughput, and output performance.

H3. Local political support has a stronger association with national political support than with evaluations of local political performance.

Conditional Effects of Local Embeddedness and Political Sophistication

Up to this point, we have introduced two rivaling interpretations of local political support, one arguing that it is object-specific and evaluative and the other that it is not. In a multilayered government structure, we should consider the conditions under which these interpretations are more or less likely to be valid.

First, in a context of multilevel government we may expect that the validity of the two interpretations depends on the extent to which people are embedded in their local democracy. Feeling part of the political community is the most fundamental, diffuse mode of political support (Easton, 1975; Norris, 2011). We may observe this local embedding in citizens' length of residence, their feelings of attachment to the municipality, their offline or online involvement in local political activities, and their support for local parties (rather than local chapters of national parties). Local embedding is likely to stimulate local political support (Denters, 2014; Fitzgerald and Wolak, 2016). More importantly, we expect that the locus of local political support is more likely to be local among citizens that are themselves more strongly embedded in their local political community: ceteris paribus, citizens are more likely to base their local political support on local, object-specific evaluations, and need to rely less on other cues or heuristics, when they feel part of the political community.

H4a. The association between local political support and evaluations of local political performance is stronger among residents who are more strongly embedded in their municipality.

H4b. The association between local political support and national political support is weaker among residents who are more strongly embedded in their municipality.

Second, political sophistication - a mixture of political interest, attentiveness and knowledge - plays a consistent role in public opinion research (Zaller, 1992). People are more likely to use heuristics when they have less knowledge of or interest in that object (Lupia, 1994; Kahneman, 2011). There is ample evidence for this conditional relationship regarding political support in multilevel settings. Within the European Union, higher levels of political knowledge, attention, and education decrease the degree to which national political considerations are used as a proxy for EU attitudes (Desmet et al., 2012; Hobolt, 2012; Armingeon and Ceka, 2014; Muñoz, 2017).

Education is an important discriminator between citizens with low vs. high levels of political sophistication. Most notably, the high educated are not only more likely more likely to have a better understanding of and interest in politics (Bovens and Wille, 2017); they are also more likely to respond to their governments' actual performance (Hakhverdian and Mayne, 2012; Mayne and Hakhverdian, 2017; van der Meer and Hakhverdian, 2017). This suggests that the association between local political support and local political performance is likely to be stronger among the higher than among the lower educated.

H5a. The association between local political support and evaluations of local political performance is stronger more sophisticated than among the less sophisticated.

H5b. The association between local political support and national political support is weaker among the more sophisticated than among the less sophisticated.

Although the theoretical approaches we build on differ in terms of the theorized causality, we restrict our theoretical assumptions and analyses to associational only. While the institutional approach theorizes input, output and throughput evaluations to be causes of political support, this applies primarily to objective indicators. Subjective indicators, that is, evaluations of performance, are potentially more endogenous to political support (e.g., De Blok et al., 2020). Furthermore, the multilayered approach does not focus on causality but the relationships between trust in different objects. Hence, this multilayered approach sees national and local support either as equals in one syndrome of trust, or national support as dominant and spilling over in local support (cue-taking). In this paper, we do not make any claims on causality, and instead investigate the associations between evaluations of local political performance, national political support, and local political support. In this way, we aim to assess the locus of local political support, namely the extent to which it is rooted in attitudes on local performance or national support, without any claim as to whether those roots are causes or associations.

Materials and Methods

Dutch Local Election Study 2016

To test these hypotheses, we need (1) data on political support (democratic satisfaction and/or political trust) at the local and national levels, (2) detailed evaluations of input, throughput, and output performance by local governments, and (3) information about the extent to which citizens are embedded in their municipality.

These demands are met by the first Dutch Local Election Study (DLES). The first round of the DLES was collected in the Spring of 2016, shortly after a decentralization process was implemented in the Netherlands and 2 years before nation-wide local elections would take place. DLES 2016 would serve as the baseline measurement for future editions. DLES 2016 is a national sample that uniquely contains a wide range of measures (on citizens' evaluations of their municipality's performance on input, throughput, and output, as well these citizens' political embedding in their municipality) that were collected for the purposes of this study.

The level of decentralization in the Netherlands is about the average level EU wide, making it well-suited for an inquiry into the locus of local political support. The Netherlands is commonly classified as a decentralized unitary state: Municipalities have specifically delineated tasks, but are limited in taxation. This is reflected in OECD statistics on local government (which in these statistics also encompasses the provinces and the water authorities). The share of government expenditure that is local is above average (31% of total government expenditure), though considerably lower than in Nordic countries such as Sweden and Denmark. The decentralization process of the mid-2010s raised local expenditures by a few percentage points. By contrast, the share of local tax revenues is slightly below average (9% of total government tax revenues). This discrepancy is primarily because the execution of several costly government programmes – most notably education and welfare – is decentralized to the local level.

Our Dutch case faces two limitations with regard to generalizability, upon which we also reflect in the conclusion. First, in unitary countries with a proportional electoral systems such as the Netherlands, trust and satisfaction in local authorities is typically lower than in federal countries and/or countries with majoritarian systems (Fitzgerald and Wolak, 2016). Therefore, our findings are first and foremost generalizable to unitary countries with proportional electoral systems, and to a lesser extent to either federal countries or majoritarian systems, which have institutionally a stronger local dynamic. Second, although the dominant pattern of trust in local politics exceeding trust in national politics is found in the Netherlands, the average political trust levels are above European average (Muñoz, 2017). Because there are some indications that the gap in support between local and national is larger in countries with the very lowest national support (Muñoz, 2017: 73), the locus of local political support might be less affected by national dynamic in those countries.

Operationalization

Local Political Support

The literature on political support for democracy and its institutions has predominantly focused on two sets of middle-range indicators (Zmerli et al., 2006; Norris, 2017): satisfaction with democratic performance and trust in political institutions. The two are related but distinct. Conceptually, satisfaction with democracy (SWD) is a more diffuse mode of political support than political trust, referring to the functioning of respectively the democratic system, or the institutions in that system (Norris, 2017). Empirically, while many studies suggest that democratic satisfaction and political trust have similar sources, the latter may be more sensitive to the actual performance of the political body (van der Meer and Hakhverdian, 2017). Possibly, this reflects that political trust is talked about more commonly when citizens discuss politics than democratic satisfaction. For these reasons, we analyze democratic satisfaction and political trust separately.

The widely used measures of SWD and political trust are both challenged for their conceptual and cross-nationally empirical ambiguity (e.g., Canache et al., 2001; Linde and Ekman, 2003; Van der Meer and Ouattara, 2019). However, this paper focuses on within-person comparisons on these two dominant measures. Therefore, we are confident in the validity of our findings on these measures.

Local satisfaction with democracy is measured via the survey question “In general, how satisfied are you with the way democracy functions in your municipality?.” Respondents were able to answer on a 4-point scale ranging from “not at all satisfied” to “very satisfied.” High scores reflect a higher level of democratic satisfaction.

To measure trust in political institutions, we rely on measures in a question battery that reads “Would you, for each of the following institutions, indicate how much trust you have in them?.” As objects of trust the question battery covers the executive and the (main) legislature at both the local level and at the national level. At the local level the legislative is the municipal council, and the executive is the college of mayor and aldermen. We calculated the sum scores of trust in these two main local political institutions (each on a 4 point scale ranging from “none at all” to “a lot”) that are strongly correlated (0.8). High scores reflect high levels of trust.

National Political Support

We operationalized political support at the national level similarly to the measures at the local level. National democratic satisfaction is measured with the same question as local democratic satisfaction, exchanging “your municipality” for “the Netherlands.” National political trust is based on different but equivalent items from the same question battery. At the national level the main legislative power is the Second Chamber1 and the executive is the government. We again took the sum of these two political institutions (correlation: 0.8).

All tables show the results from the explanatory models of democratic satisfaction and political trust side by side.

Local Input, Throughput, and Output Evaluations

The DLES contains an extensive question battery that taps into respondents' evaluation of the extent to which a range of democratic ideals is realized in their municipality2, a battery on evaluations of the main local services, and a standard efficacy battery. Based on these question batteries, our data cover multiple input, throughput, and output evaluations. Note that we do not make assumptions about the extent to which input, throughput and output are single, uni-dimensional factors. That is the reason we make use of sheaf coefficients rather than data reduction analyses (see the Methods section below).

Input evaluation is measured via six statements. Three are derived from the battery on the realization of democratic ideals in one's municipality: (1) free and fair local elections; (2) the organization of public consultation evenings for residents; (3) the inclusion of all social groups in the municipal council; and (4) the provision of reliable news on local government by local media. These items range from 0 (does not apply at all) to 10 (applies in full). In addition, we include agreement with two statements on a 5-point Likert scale. The first reads “Members of the municipal council do not care about the opinion of people like me.” The second reads: “There are currently sufficient ways in which citizens can make clear what their opinion is on current affairs in this municipality.”

Throughput evaluation is based on four indicators from the battery on the realization of democratic ideals: (1) transparency by the local government on the way decisions are made; (2) equal treatment of all groups and individuals by local government; (3) taking minority positions into account by the municipality; (4) willingness to compromise by political parties in the municipal council. All items range from 0 (does not apply at all) to 10 (applies in full).

Finally, output evaluation encompasses six indicators. General satisfaction with services in the municipality ranges from 1 (very bad) to 10 (very good). Next to that, we measure satisfaction with a range of specific services (care; facilities for sports and play; public transport; green space; safety) on a scale from 0 (not at all satisfied) to 10 (completely satisfied).

Local Embeddedness

To capture local embeddedness, we rely on a range of indicators, attitudinal and behavioral, as well as social and political. Subjective feelings of attachment to the municipality ranges from “not at all attached” to “very attached” on a 4 point scale. Length of residence measures the self-reported number of years that respondents have continuously lived in their current municipality. While we report the absolute number of years, our findings are robust to the use of a log-transformed measure. Local political activism is measured dichotomously due to the highly skewed distribution3. Respondents who in the past 5 years participated in at least one of a range of 11 modes of local participation4 are coded as active (1); those who did not as inactive (0).

Political Sophistication

Political sophistication is measured in two ways. We assess local political interest on a three point scale (similar to the one used in the Dutch national election survey), ranging from not interested and quite interested to very interested. Level of education is based on the highest completed education according to the categories by Statistics Netherlands. It is an ordinal measure with six categories. We model it as a linear variable, as we found no evidence for substantive non-linearity.

Control Variables

Finally, all models control for gender, level of education (in models not already including education to test hypotheses on political sophistication), as well as satisfaction with one's personal finances and satisfaction with the national economy (as a rivaling indicator for general satisfaction), in line with the literature (e.g., Fitzgerald and Wolak, 2016). Table A in the Appendix shows the descriptive statistics of all variables used.

Missing Values

The level of detail on these variables came at a cost in the shape of missing values, both on the dependent and independent variables. Respondents apparently found it easier to provide a substantive answer on the items that measure political trust (only 2% missing values on the national and local objects of political trust) than on the SDW items (6% missing values on national SWD and 10% missing values on local SWD). On some of the independent variables, the share of respondents with missing values surges to 10–20 percent of the sample. This is particularly prevalent among variables that seem to require a close, detailed understanding of local politics (see Appendix Table A for the number of cases of each variable). High levels of missing values are potentially problematic, particularly because the missingness does not seem to be at random.

Different strategies exist to deal with missing values. Listwise deletion of all respondents with at least one missing value would lead to a net loss of almost 60% of our sample in the full multivariate models. Missing value imputation has been presented as a superior and more efficient option (King et al., 2001; Lall, 2016). Yet, that only holds under the assumption that data are missing at random (MAR). If they are not missing at random (MNAR), multiple imputation might instead induce further bias whereas listwise deletion does not (Allison, 2014; Pepinsky, 2018). The suggestion that data on the DLES 2016 measures are missing at random is quite unlikely.

We dealt with the problem of missing data by testing the robustness of our models to different strategies of dealing with missing data. On the one extreme, we performed listwise deletion, eliminating all respondents with at least one missing value on at least one of the variables identified above. Full listwise deletion led to a net sample size of 1,100 respondents. On the other extreme, we performed missing value imputation on all missing data in our model. Full imputation led to a net sample size of 2,356 respondents. Additionally, we pursued two moderate strategies that would do more justice to our data and model. Partial listwise deletion entails the deletion of respondents except for those who only have missing values on non-significant components of the sheaf coefficient (see below). This led to a net sample of 1,400 respondents. The final moderate strategy is partial imputation. We first deleted respondents with missing data on more than a quarter of the variables in our model (assuming that the non-random element of missing data would be strongest there), before engaging in missing value imputation on the remainder of the respondents. Partial imputation led to a net sample of 1,995 respondents.

Given the number of missing values, and the relevance of the selection effect to the core hypotheses of this article, we argue that partial imputation is the best strategy and is used in all models presented in Tables 1–7. As a robustness check, we report on the findings of the various strategies at the end of the Result section. Although our findings on political trust do vary in aspect depending on the method chosen to deal with missing cases, these variations do not impact our substantive conclusions. We discuss this in the Result section.

Method

Multilevel Regression Analysis

Even though we do not include municipality level determinants, we need to take the multilevel structure of our data into account, as respondents are nested in these municipalities. Multilevel modeling allows us to correct for this clustering. Therefore, we employed multilevel analysis in Stata 15.1 using the mi and xtmixed commands. All in all, we end up with 1,995 respondents in 353 municipalities for satisfaction with democracy, and 1,931 respondents in 350 municipalities for political trust5. The intraclass correlation (0.18 for democratic satisfaction; 0.15 for political trust) in the empty model implies that a remarkably high share of variance is situated at the municipal level.

We estimate linear regression models. Although our two dependent variables are ultimately ordinal, the answer distributions are relatively normal. We checked the four conventional assumptions for linear regression analysis and found no strange aberrations. None of the variables included in the conditional models have been centered. As we do not estimate cross-level interaction effects we did not need to estimate random slope multilevel models (that allow the slopes of the individual level effects to vary at L2).

Sheaf Coefficient

Various hypotheses require us to compare the combined effects of a block of indicators (input/throughput/output; local vs. national considerations). We do so by employing Heise's sheaf coefficient (Whitt, 1986). The sheaf coefficient is a standardized summary of the combined effects of the variables that it integrates. The use of a sheaf coefficient does not transform the results from model, but presents them in a different way (Buis, 2010).

The value of sheaf coefficients for the aim of this paper is clear in light of the alternatives. On the one hand, a model with dozens of determinants is unruly. It would not easily allow us to assess the joint effect of a cluster of variables, nor allow us to test all theoretically relevant interaction effects simultaneously. On the other hand, standard data reduction techniques would lead to a loss of information. Calculating the mean score of this cluster of variables (even when standardized) would ignore the relative importance of each of the variables. Employing scaling techniques such as CFA or Mokken scales only works if the cluster of variables load empirically on a (single) underlying factor. While appropriate in many instances, that requirement is not necessary or even useful here, because we do not anticipate that a single factor exist in the distribution on each of the individual measures.

Sheaf coefficients, by contrast, allow us to summarize the statistical effect of a select cluster of variables without loss of data. A model with a sheaf coefficient is in every way the same as with only individual items, except that presentation of those individual items is replaced with a one summary sheaf coefficient, with can be interpreted as a normal regression coefficient. The sheaf coefficient will not affect the other parameters in the model. Hence, it suits the theoretical aims of our empirical analysis.

Results

Main Effects: Local Merits or National Derivative?

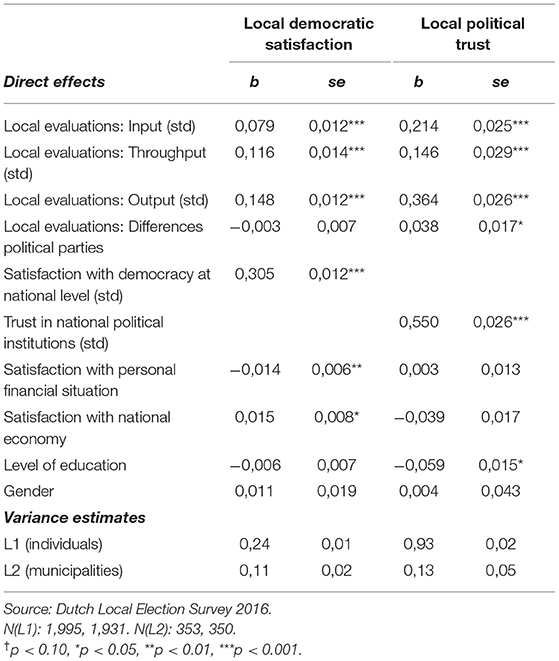

Table 1 offers a test of the first set of hypotheses. It displays the effects of input, throughput, and output evaluations that are summarized in sheaf coefficients. The full model, without the sheaf coefficients that combine the separate parameters, is reproduced in Appendix Table B. Together, the determinants explain ~31% of the individual variance in satisfaction with democracy and ~23% of the variance across municipalities. For political trust, these figures are respectively 27 and 40%.

We find that both local democratic satisfaction and local political trust are significantly related to local evaluations of political performance. This supports H1. In line with hypotheses H1a–H1c, input, throughput, and output evaluations all significantly relate to political support. Of these three types of evaluations, output evaluations have the largest standardized effect on democratic satisfaction (b = 0.15) and political trust (b = 0.36). Interestingly, input evaluations are least important to democratic satisfaction, while throughput evaluations are least important to political trust. This underlines an intuitive difference between the two middle-range indicators of political support. Democratic satisfaction is directed somewhat more toward the process of decision-making. By contrast, evaluations of responsiveness seem to have a relatively stronger effect on trust in political institutions.

Table 1 also tests the extent to which local political support is embedded in its national equivalent. We find strong coefficients both for satisfaction with democracy (b = 0.30) and for political trust (b = 0.55). This supports H2.

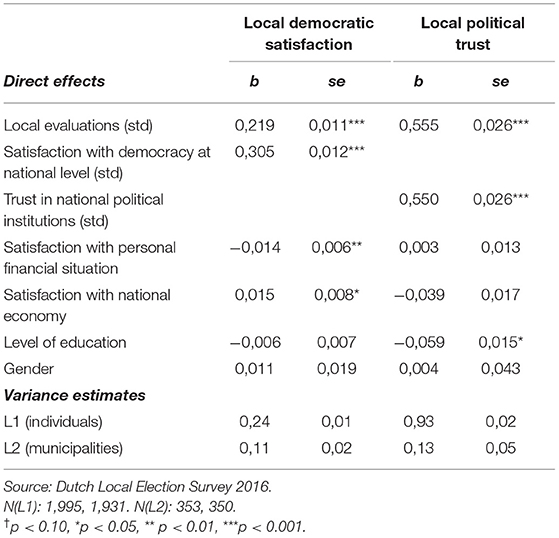

Table 2 combines all three types of local political evaluations (input, throughput, and output) in standardized sheaf coefficients. This enables us to determine whether local political support is embedded more strongly in national political support than in local political evaluations. The results are mixed. In line with H3, we find that local democratic satisfaction is more strongly related to national democratic satisfaction (b = 0.31) than to local evaluations (b = 0.22). This would suggest that the locus of local democratic satisfaction is primarily an aspect or derivation of a more general (national) attitude toward democracy. However, we do not find support for H3 on local political trust, where the standardized effect of national political trust (b = 0.55) and local evaluations (b = 0.56) are statistically indistinguishable.

Conditional Effects of Local Embeddedness

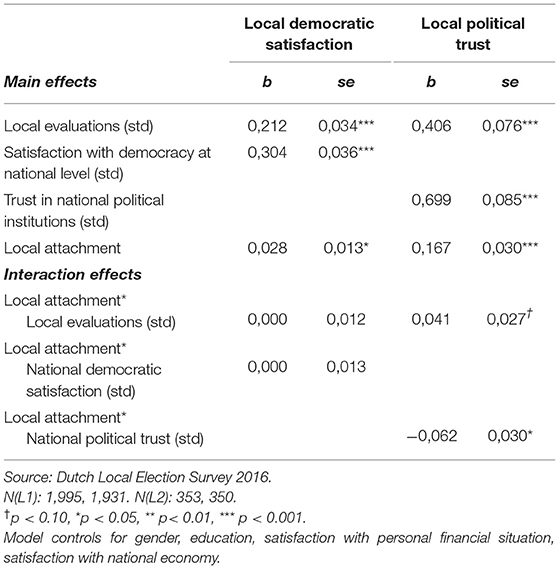

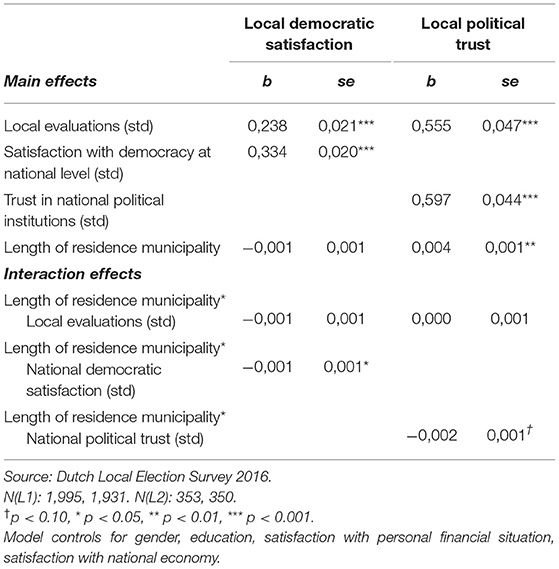

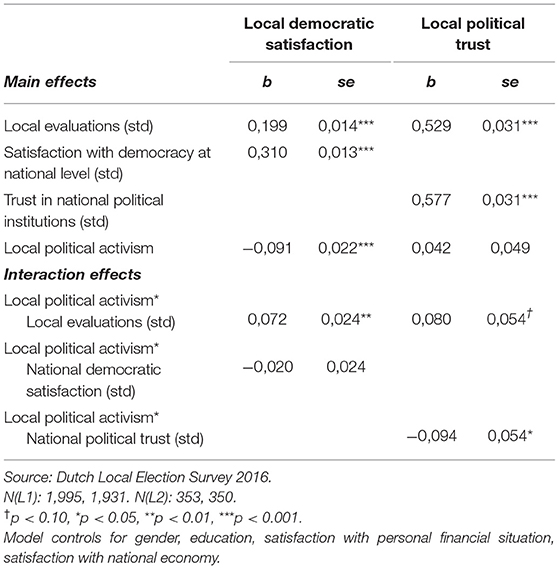

Tables 3–5 report the models that test whether local embeddedness moderates the effects of local evaluations and national political support, namely with local attachment, local residence, and local political activism.

Hypothesis 4a posited that local embeddedness enhances the effect of local political evaluations. This hypothesis finds little support. All conditional effects are non-significant, except for one: Table 5 shows that local evaluations have a significantly stronger effect on democratic satisfaction among citizens who are politically active in their municipality (b = 0.27) than among those who are not (b = 0.20). While this finding is in line with hypothesis 4a, this supporting evidence is found in only one single model.

Hypothesis 4b posited that local embeddedness mitigates the effect of national political support. We find different results for the two modes of political support. The relationship between national and local democratic satisfaction is slightly but significantly mitigated by length of residence, but not by other measures of local embeddedness. The longer the time span that people lived in their municipality, the weaker the correlation between national and local political support. Yet, the relationship is substantially so small, that even among the elderly the marginal statistical effect of national political support remains stronger than that of local political evaluations.

The relationship between trust in national and trust in local political institutions is significantly mitigated by subjective local attachment and by local political activism. These effects, too, are in line with the hypothesis. However, conditional effects are not very common.

Overall, our findings provide some weak indication that that local embeddedness can indeed enhance the sensitivity for political performance at the local level, and concurrently mitigate their reliance on their national political support. Yet, these effects are scarce and modest.

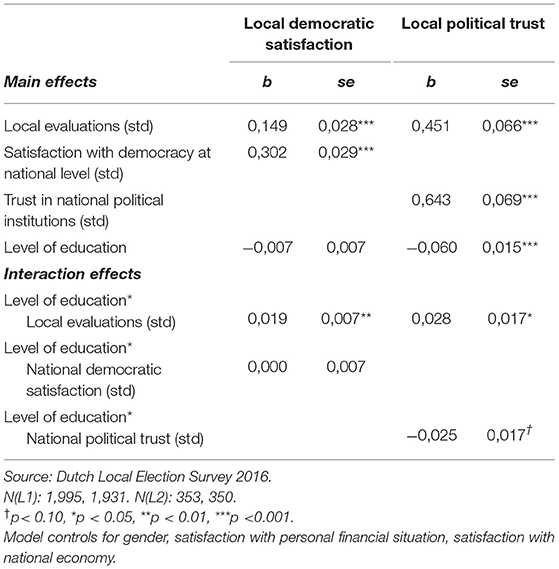

Conditional Effects of Political Sophistication

Finally, Tables 6, 7 show the moderation effects of political sophistication. The tables provide unequivocal support for H5a. Among those with higher levels of political interest and/or a higher level of education, local democratic satisfaction, and local political trust are more strongly embedded in local political evaluations. This suggests that political sophistication makes people's local political support more sensitive to the performance of local democracy.

Hypothesis H5b finds less consistent support. Among residents with high levels of interest in local politics, levels of trust in local political institutions tends to be significantly less derivative of their trust in national politics. Yet, other moderating effects of political sophistication on the relationship between national and local political support are not significant. All in all, evidence that the locus of local political support depends on local embeddedness and political sophistication remains tentative.

Robustness Checks

We performed two sets of robustness checks. First, we analyzed whether our findings hold when we model the significant interaction effects from the previous tables simultaneously. The conditional effects on SWD are highly robust: All significant effects in Tables 3–7 remain significant when estimated in a single model.

Second, we checked the robustness of our main findings under different strategies of dealing with missing data. Table C of the Appendix reflects Table 2 in the main text. We find that the models on SWD are highly robust, regardless whether we employ full listwise deletion, full imputation, or a partial strategy. However, the models on political trust are less robust. Under a strategy of full listwise deletion political trust is more strongly tied to local performance evaluation than to national political support, whereas the two were statistically tied under the strategy of partial imputation we employed in our main analyses. Yet, our substantive conclusion on hypothesis 3 remains the same (supported for SWD, rejected for political trust)6. The interactive models are also highly robust for SWD, but less robust for political trust.

Discussion

In response to the increasing executive responsibilities of local governments (Hooghe et al., 2010), this article aimed to examine to what extent citizens' local political support is best understood as (i) an evaluation of local governments on their own merits, or (ii) as an aspect of more general, multilayered trust attitude.

Our findings show that local political performance matters for local political support. Comparing output performance directly with input and throughput performance furthermore indicates that output outperforms the other two. This is good news, for those who consider that increasing responsibilities of local government should be balanced by a process of local accountability.

That does not mean to say that local politics is primarily evaluated on its own merits. Instead, a measure based on a comprehensive set of local performance evaluations is outperformed by national political support (local democratic satisfaction) or at best of equal importance (local political trust). This means that indeed local political support is also related to a more general attitude toward politics. This balance between local merits and national influence is affected by political sophistication - and to a lesser extent by local embeddedness - in different ways. Political sophistication increases citizens' sensitivity to local performance, while local embeddedness modestly mitigates reliance on more general (national) orientations of political support.

Our data do not enable us to further examine the mechanism behind the influence of national political support. The two theoretical explanations in the literature, trust-as-syndrome (assuming a more general trusting attitude, regardless of the object) vs. cue-taking (assuming an hierarchical ordering of levels of government in public opinion) are both worth examining in future research. Testing these rival mechanisms would provide another test of the importance of local political dynamics and of a local democracy culture.

We find notable differences between the two middle-range indicators for political support, democratic satisfaction and political trust. First, while evaluations of output performance are the most important local driver of political support for both measures, evaluations of throughput matter more for local democratic satisfaction, evaluations of input more for local political trust. This result is different to the findings of cross-national studies that suggest that input institutions have a stronger effect on (national) democratic satisfaction than on (national) political trust (cf. van der Meer and Hakhverdian, 2017).

Second, local democratic satisfaction is rooted more strongly in national democratic satisfaction than in local evaluations, whereas local political trust is rooted in both equivalently. Our analyses cannot offer firm conclusions why this is the case. We can only speculate that local political trust is an easier concept for citizens, as trust is used more commonly in political discussions. By contrast, satisfaction with democracy is a more abstract concept, inherently more reflective of the system as a whole, and harder to assess locally. This is also reflected in the non-response to these indicators. Whereas, 2% of the respondents reports that they do not know whether they trust both national and local political institutions, this share is much higher for satisfaction with democracy at the national level (6% does not know) and local level (10% does not know). These results all underline previous calls for more research, especially of a qualitative type, into the meaning and measurement of these concepts (Canache et al., 2001; Linde and Ekman, 2003; van Ham et al., 2017; Citrin and Stoker, 2018).

Despite its rather average level of decentralization, turnout, and local political trust, the Netherlands faces two limitations in terms of generalizability. First, levels of trust in and satisfaction with local (rather than national) authorities tends to be lower in systems with proportional representation such as the Netherlands (Fitzgerald and Wolak, 2016). Therefore, our findings are first and foremost generalizable to unitary countries with proportional electoral systems. Both federal countries and majoritarian systems might ensure a stronger local dynamic, which is beyond the scope of this paper. Second, while Dutch trust in local political institutions is close to the European average, trust in national political institutions is above that average (Muñoz, 2017). This might affect the national dynamic in local political support (cf. Muñoz, 2017: 73).

Devolution might be a process that changes the relationship we laid bare in this paper. On the one hand, the assignment of administrative and political responsibilities to the local level might strengthen the role of local performance evaluations. On the other hand, the process itself might complicate matters. At least in the short run, it will be difficult for citizens to correctly assess the quality of and responsibilities for services and policies (Lowery et al., 1990; Escobar-Lemmon and Ross, 2014; De Blok et al., 2020). Particularly, moderate decentralization processes make it difficult for people to correctly pinpoint these responsibilities (León, 2011), so that specific evaluations of political performance may be assigned to the national rather than the local level (De Blok et al., 2020).

This only underpins the core finding of this paper, namely the necessity for scholars of democratic satisfaction and political trust to take account of the multilayered government structure, particularly when they study objects of support that are sub- or supranational (Fitzgerald and Wolak, 2016; Muñoz, 2017). Regardless of whether it finds its roots in local evaluations or in a more general syndrome of support, local political support will be important to the functioning of local democracy in general, and the process of local democratic accountability in particular.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.dataarchive.lissdata.nl/study_units/view/749.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors had an equal contribution in the theoretical and methodological design of this paper.

Funding

This work was supported by the Dutch Science Foundation NWO (Grant Number 452-16-001, 2016).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.642356/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^The First Chamber (or Senate) is the much weaker and less central house in the Dutch bicameral system.

2. ^It is rather similar in setup to a battery in the European Social Survey 2012 (Ferrín and Kriesi, 2016).

3. ^Empirically, only 75% of respondents reports at least one out of 11 modes of participation, but <6% reports three or more. The most popular modes of activism are employed by merely 8% of the voters. Theoretically, the most important distinction is between people who engage in no activities vs. people who engage in a single activity (rather than people who engage in one vs. two or more activities). Hence, we dichotomized the scale.

4. ^Contacting a member of the municipal council, alderman, mayor, or local civil servant; visiting a meeting of the municipal council; visiting a municipal consultation evening; membership of a political party; active participation in a local action group; participation in a citizens initiative in the neighborhood; signing a petition on a local issue (online or offline), contacting a local or regional newspaper, radio, or television; contacting a political party in the municipality; commenting on municipal affairs on social media; sharing messages on political affairs in the municipality on social media.

5. ^As can be expected from a national sample, the distribution of respondents over municipalities in in line with the size of these municipalities. No municipality in our data set contains more than 3% of the voters.

6. ^This interesting result tentatively underlines H5a. Listwise deletion is likely to reduce the share of politically unsophisticated citizens. This, by itself, may explain the larger role of local performance evaluations in the full listwise model on political trust. At the very least, it also emphasizes that some “don't know” answers are meaningful in their own way (Laurison, 2015).

References

Aarts, K., and Thomassen, J. (2008). Satisfaction with democracy: do institutions matter? Elect. Stud. 27, 5–18. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2007.11.005

Anderson, C. J. (1998). When in doubt, use proxies: attitudes toward domestic politics and support for European integration. Comp. Polit. Stud. 31, 569–601. doi: 10.1177/0010414098031005002

Ares, M., Ceka, B., and Kriesi, H. (2017). Diffuse support for the European Union: spillover effects of the politicization of the European integration process at the domestic level. J. Eur. Pub. Policy 24, 1091–1115. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2016.1191525

Armingeon, K., and Ceka, B. (2014). The loss of trust in the European Union during the great recession since 2007: the role of heuristics from the national political system. Eur. Union Polit. 15, 82–107. doi: 10.1177/1465116513495595

Bovens, M., and Wille, A. (2017). Diploma Democracy: The Rise of Political Meritocracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198790631.001.0001

Buis, M. (2010). Sheafcoef: Stata module to compute sheaf coefficients. Available online at: https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:boc:bocode:s456995 (accessed September 1, 2020).

Canache, D., Mondak, J. J., and Seligson, M. A. (2001). Meaning and measurement in cross-national research on satisfaction with democracy. Public Opin. Q. 65, 506–528. doi: 10.1086/323576

Chang, E. C., and Chu, Y. (2006). Corruption and trust: exceptionalism in Asian democracies? J. Polit. 68, 259–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00404.x

Citrin, J., and Stoker, L. (2018). Political trust in a Cynical Age. Ann. Rev. Polit. Sci. 21, 49–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-050316-092550

Cole, R. L., and Kincaid, J. (2000). Public opinion and American federalism: perspectives on taxes, spending, and trust—An ACIR update. Publius 30, 189–201. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubjof.a030060

Dahl, R. A. (1967). The city in the future of democracy. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 61, 953–970. doi: 10.2307/1953398

De Blok, L., van der Meer, T. W. G., and van der Brug, W. (2020). Policy evaluations, perceptions of responsibility, and political trust: a novel application of the REWB model to testing evaluation-based political trust. J. Elect. Public Opin. Parties. doi: 10.1080/17457289.2020.1780433

DeHoog, R. H., Lowery, D., and Lyons, W. E. (1990). Citizen satisfaction with local governance: a test of individual, jurisdictional, and city-specific explanations. J. Polit. 52, 807–837. doi: 10.2307/2131828

Denters, B. (2014). Beyond ‘What do I get?' Functional and procedural sources of Dutch citizens' satisfaction with local democracy. Urban Res. Pract. 7, 153–168. doi: 10.1080/17535069.2014.910921

Denters, B., and Rose, L. E. (2005). Comparing Local Governance. Trends and Developments. New York, NY: Palgrave Mac Millan. doi: 10.1007/978-0-230-21242-8

Desmet, P., Van Spanje, J., and de Vreese, C. (2012). ‘Second-order' institutions: national institutional quality as a yardstick for EU evaluation. J. Eur. Public Policy 19, 1071–1088. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2011.650983

Easton, D. (1975). A re-assessment of the concept of political support. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 5, 435–457. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400008309

Escobar-Lemmon, M., and Ross, A. D. (2014). Does decentralization improve perceptions of accountability? Attitudinal evidence from Colombia. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 58, 175–188. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12043

Ferrín, M., and Kriesi, H., (eds.). (2016). How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fitzgerald, J., and Wolak, J. (2016). The roots of trust in local government in western Europe. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 37, 130–146. doi: 10.1177/0192512114545119

Grimes, M. (2017). “Procedural justice and political trust,” in Handbook on Political Trust, eds S. Zmerli and T. W. G. van der Meer (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar), 256–269. doi: 10.4337/9781782545118.00027

Grimmelikhuijsen, S. (2012). Linking transparency, knowledge and citizen trust in government: an experiment. Int. Rev. Administr. Sci. 78, 50–73. doi: 10.1177/0020852311429667

Hakhverdian, A., and Mayne, Q. (2012). Institutional trust, education, and corruption: a micro-macro interactive approach. J. Polit. 74, 739–750. doi: 10.1017/S0022381612000412

Hansen, S. W. (2015). The democratic costs of size: how increasing size affects citizen satisfaction with local government. Polit. Stud. 63, 373–389. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12096

Hardin, R. (1999). “Do we want trust in government?,” in Democracy and Trust, ed M. E. Warren (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 22–41. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511659959.002

Harteveld, E., van der Meer, T. W. G., and de Vries, C. E. (2013). In Europe we trust? Exploring three logics of trust in the European Union. Eur. Union Polit. 14, 542–565. doi: 10.1177/1465116513491018

Heath, A., McLean, I., Taylor, B., and Curtice, J. (1999). Between first and second order: a comparison of voting behaviour in European and local elections in Britain. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 35, 389–414. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.00454

Hobolt, S. B. (2012). Citizen satisfaction with democracy in the European Union. J. Common Market Stud. 50, 88–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5965.2011.02229.x

Hooghe, L., Marks, G. N., and Schakel, A. H. (2010). The Rise of Regional Authority: A Comparative Study of 42 Democracies. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203852170

Jennings, M. K. (1998). “Political trust and the roots of devolution,” in Russell Sage Foundation Series on Trust, Vol. 1, eds V. Braithwaite and M. Levi (New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation New York), 218–244.

King, G., Honaker, J., Joseph, A., and Scheve, K. (2001). Analyzing incomplete political science data: an alternative algorithm for multiple imputation. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 95, 49–69. doi: 10.1017/S0003055401000235

Kritzinger, S. (2003). The influence of the nation-state on individual support for the European Union. Eur. Union Polit. 4, 219–241. doi: 10.1177/1465116503004002004

Lall, R. (2016). How multiple imputation makes a difference. Polit. Anal. 24, 414–433. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpw020

Laurison, D. (2015). The willingness to state an opinion: inequality, don't know responses, and political participation. Sociol. Forum 30, 925–948. doi: 10.1111/socf.12202

León, S. (2011). Who is responsible for what? Clarity of responsibilities in multilevel states: The case of Spain. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 50, 80–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2010.01921.x

Linde, J., and Ekman, J. (2003). Satisfaction with democracy: a note on a frequently used indicator in comparative politics. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 42, 391–408. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.00089

Lowery, D., Lyons, W. E., and DeHoog, R. H. (1990). Institutionally-induced attribution errors: their composition and impact on citizen satisfaction with local government services. Am. Polit. Q. 18, 169–196. doi: 10.1177/1532673X8001800204

Lupia, A. (1994). Shortcuts versus encyclopedias: information and voting behavior in California insurance reform elections. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 88, 63–76. doi: 10.2307/2944882

Marien, S. (2011). The effect of electoral outcomes on political trust: a multi–level analysis of 23 countries. Elect. Stud. 30, 712–726. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2011.06.015

Marien, S., Dassonneville, R., and Hooghe, M. (2015). How second order are local elections? Voting motives and party preferences in Belgian municipal elections. Local Govern. Stud. 41, 898–916. doi: 10.1080/03003930.2015.1048230

Martini, S., and Quaranta, M. (2019). Citizens and Democracy in Europe: Contexts, Changes and Political Support. Houndsmills: Palgrave. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-21633-7

Mayne, Q., and Hakhverdian, A. (2017). “Education, socialization, and political trust,” in Handbook on Political Trust, eds S. Zmerli and T. W. G. van der Meer (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar), 176–196. doi: 10.4337/9781782545118.00022

Mishler, W., and Rose, R. (2001). What are the origins of political trust? Testing institutional and cultural theories in post-communist societies. Comp. Polit. Stud. 34, 30–62. doi: 10.1177/0010414001034001002

Montalvo, D. (2010). Understanding Trust in Municipal Governments. AmericasBarometer Insights 35. United States Agency for International Development, Washington, DC, United States.

Muñoz, J. (2017). “Political trust and multilevel government,” in Handbook on Political Trust, eds S. Zmerli and T. W. G. van der Meer (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar), 69–88. doi: 10.4337/9781782545118.00015

Muñoz, J., Torcal, M., and Bonet, E. (2011). Institutional trust and multilevel government in the European Union: congruence or compensation? Eur. Union Polit. 12, 551–574. doi: 10.1177/1465116511419250

Norris, P. (2011). Democratic Deficits: Critical Citizens Revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511973383

Norris, P. (2017). “The conceptual framework of political support,” in Handbook on Political Trust, eds S. Zmerli and T. W. G. van der Meer (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar), 19–32. doi: 10.4337/9781782545118.00012

Oliver, J. E. (2000). City size and civic involvement in metropolitan America. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 94, 361–373. doi: 10.2307/2586017

Pepinsky, T. B. (2018). A note on listwise deletion versus multiple imputation. Polit. Anal. 26, 480–488. doi: 10.1017/pan.2018.18

Rahn, W. M., and Rudolph, T. J. (2005). A tale of political trust in American cities. Public Opin. Q. 69, 530–560. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfi056

Rallings, C., and Thrasher, M. (2007). The turnout “gap” and the costs of voting–a comparison of participation at the 2001 general and 2002 local elections in England. Public Choice 131, 333–344. doi: 10.1007/s11127-006-9118-9

Rohrschneider, R. (2002). The democracy deficit and mass support for an EU-wide government. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 46, 463–475. doi: 10.2307/3088389

Schmidt, V. A. (2013). Democracy and legitimacy in the European Union revisited: input, output and ‘throughput'. Polit. Stud. 61, 2–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00962.x

Torcal, M., and Christmann, P. (2018). Congruence, national context and trust in European institutions. J. Eur. Public Policy 26, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2018.1551922

van der Meer, T. W. G. (2017). “Dissecting the causal chain from quality of government to political support,” in Myth and Reality of the Legitimacy Crisis: Explaining Trends and Cross-National Differences in Established Democracies, eds C. van Ham, J. Thomassen, K. Aarts, and R. B. Andeweg (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 136–155.

van der Meer, T. W. G., and Hakhverdian, A. (2017). Political trust as the evaluation of process and performance: a cross-national study of 42 European countries. Polit. Stud. 65, 81–102. doi: 10.1177/0032321715607514

Van der Meer, T. W. G., and Ouattara, E. (2019). Putting ‘political' back in political trust: an IRT test of the unidimensionality and cross-national equivalence of political trust measures. Qual. Quant. 53, 2983–3002. doi: 10.1007/s11135-019-00913-6

van Erkel, P., and van der Meer, T. W. G. (2016). Macroeconomic performance, political trust and the Great Recession: a multilevel analysis of the effects of within-country fluctuations in macroeconomic performance on political trust in 15 EU countries, 1999–2011. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 55, 177–197. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12115

van Ham, C., Thomassen, J., Aarts, K., and Andeweg, R. (2017). Myth and Reality of the Legitimacy Crisis:Explaining Trends and Cross-National Differences in Established Democracies. Oxford: Oxford UniversityPress. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198793717.001.0001

Werner, H. (2020). Pragmatic citizens: A bottom-up perspective on participatory politics. Dissertation. University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Whitt, H. P. (1986). The sheaf coefficient: a simplified and expanded approach. Soc. Sci. Res. 15, 174–189. doi: 10.1016/0049-089X(86)90014-1

Zaller, J. (1992). The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511818691

Zmerli, S., and Newton, K. (2017). “Objects of political and social trust: scales and hierarchies,” in Handbook on Political Trust, eds S. Zmerli and T. W. G. van der Meer (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar), 104–124. doi: 10.4337/9781782545118.00017

Keywords: democratic satisfaction, political trust, local democracy, multi-level government, local embeddedness

Citation: Steenvoorden EH and van der Meer TWG (2021) National Inspired or Locally Earned? The Locus of Local Political Support in a Multilevel Context. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:642356. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.642356

Received: 15 December 2020; Accepted: 06 April 2021;

Published: 10 May 2021.

Edited by:

Ben Seyd, University of Kent, United KingdomReviewed by:

Camille Bedock, UMR5116 Centre Émile durkheim Science Politique et Sociologie Comparatives, FranceMitchel Herian, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, United States

Copyright © 2021 Steenvoorden and van der Meer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eefje H. Steenvoorden, ZS5oLnN0ZWVudm9vcmRlbkB1dmEubmw=

Eefje H. Steenvoorden

Eefje H. Steenvoorden Tom W. G. van der Meer

Tom W. G. van der Meer