94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 26 April 2021

Sec. Political Participation

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.642236

This article is part of the Research TopicPolitical TrustView all 9 articles

A popular explanation for the recent success of right-wing populist candidates, parties and movements is that this is the “revenge of the places that don't matter”. Under this meso-level account, as economic development focuses on increasingly prosperous cities, voters in less dynamic and rural areas feel neglected by the political establishment, and back radical change. However, this premise is typically tested through the analysis of voting behavior rather than directly through citizens' feelings of political trust, and non-economic sources of grievance are not explored. We develop place-oriented measures of trust, perceived social marginality and perceived economic deprivation. We show that deprived and rural areas of Britain indeed lack trust in government. However, the accompanying sense of grievance for each type of area is different. Modeling these as separate outcomes, our analysis suggests that outside of cities, people lack trust because they feel socially marginal, whereas people in deprived areas lack trust owing to a combination of perceived economic deprivation and perceived social marginality. Our results speak to the need to recognize diversity among the “places that don't matter,” and that people in these areas may reach a similar outlook on politics for different reasons.

Political scientists often view electoral politics in geographical terms. However, a longstanding challenge for the discipline remains: understanding how the places where people live shape political attitudes and behaviors. Pronounced spatial patterns of voting in recent electoral events—Donald Trump's victory in the 2016 US presidential election and the UK's 2016 vote for Brexit to name just two—have re-energized the study of political geography. One key contribution has come from economic geographer Rodríguez-Pose (2018), who argues that as economic development focuses on increasingly prosperous cities, voters in declining and lagging-behind areas feel neglected by the political establishment, and back radical change. The causal chain—economic inequality breeds political distrust breeds populism—has proved an attractive and intuitive one. Its echoes can be felt in media narratives around these key political events, as well as in the response of policy communities, stressing the need to reduce spatial inequalities for the purpose of redressing grievances and thereby restoring political stability.

For political science, the argument has been a useful corrective to a tendency to see political attitudes and behaviors either as a response to individual-level or national-level factors, having less to say about the crucial “meso-level” of our experiences of the places we live our lives (Mutz and Mondak, 1997). However, the argument advanced by Rodríguez-Pose has three notable limitations.

The first is its reliance upon aggregate level voting patterns. The fundamental premise is explored through analysis of voting behavior, specifically the tendency in recent elections for more rural and economically deprived areas to vote for right-wing populists, as in the 2016 US (Monnat and Brown, 2017; Scala and Johnson, 2017) and Austrian (Gavenda and Umit, 2016) presidential elections, the 2017 German federal election (Schwander and Manow, 2017) and the 2017 French presidential election (Evans et al., 2019) and latterly Boris Johnson's success in flipping “Red Wall” seats at the 2019 UK general election (Cutts et al., 2020). The votes of those places for Brexit, a cause championed by right-wing populists and inflected with their concerns and rhetoric by the Vote Leave campaign, is also put forward as evidence for this claim (Becker et al., 2017).

Rodríguez-Pose cites several correlational studies and has since bolstered the case with further aggregate-level analyses of anti-EU voting across Europe as a whole (Dijkstra et al., 2020) and voting for Donald Trump in 2016 (Rodríguez-Pose et al., 2020). Further research has sought to determine whether these behaviors truly reflect contextual effects and if so, how those effects operate (Colantone and Stanig, 2018; Ansell and Adler, 2019; Carreras et al., 2019; Bolet, 2020). These studies demonstrate the plausibility of the claim that place matters to right-wing populist voting, although the magnitude of effects and their mechanisms require further inquiry.

It remains important to be wary of inferring a wider political discontent or distrust based on populist voting alone. Rooduijn (2018) argues that the voter bases of populist parties are highly inconsistent across countries and time points, including with respect to their levels of trust, while Geurkink et al. (2020) argues that populist voting can be misattributed to low levels of trust if populist attitudes are omitted from models. If our concern is to understand the effects of place on discontent and trust, then populist voting may be a blunt instrument. Surveys that directly measure feelings of discontent and distrust offer a potential alternative to obtain these insights.

Our study utilizes data from an original survey, designed to test contextual effects on a place-sensitive measure of political trust: how much people feel politicians care about their area. This speaks to the critical “intrinsic commitment” component of trust1, while also corresponding to the “left behind” worldview discussed by Rodríguez-Pose (2018). In the economic voting literature, judgments about and based on individual circumstances have been referred to as “egotropic,” while judgments about and based on local conditions have been referred to as “communotropic” (Rogers, 2014)2. In keeping, we call the measure used here “communotropic trust,” to reflect both the local focus of the trust judgment and its expected basis in the (real and perceived) local environment3.

The second main limitation of the “places that don't matter” thesis is its tendency to flatten the politics of place onto a single geographic axis between less-dense, economically unsuccessful areas on the one hand and denser, more prosperous areas on the other hand. After all, not all cities are economically vibrant and not all towns and villages are lagging. More importantly, Rodríguez-Pose's argument implies that different areas will politically polarize only to the extent that they economically polarize. A rich literature on the rural-urban or “density” divide (Wilkinson, 2019) suggests something different: a broader social conflict cutting across class and wealth gaps (Gimpel et al., 2020), which may also have consequences for trust. Our core research question stems from this: what effect do the deprivation and density divides have on trust? We argue that—separating out these spatial dimensions and including each as independent contextual predictors—more deprived areas and low-density rural areas will be lower in (communotropic) trust.

The insights from this literature bring us to the third (and critical) limitation: the need for a better model of the diversity of place-based grievances beyond the economic. Borrowing from both the populism literature, urban and rural politics literatures, and an important (if U.S.-centric) strand of research into rural resentment, we begin to flesh out such a model. The main feature of this is an extension to social grievances, specifically feelings that one's area is marginal to society. Alongside a measure of the area's perceived economic deprivation, our survey incorporates an adapted measure of an area's perceived “social marginality.” These are used in two ways: we explore the association between these place-based grievances and communotropic trust, and we model each grievance as an outcome of context. By doing so, we address another important question: what resentments are associated with feelings of distrust in the “places that don't matter”? We contend that there will be a difference in which resentments dominate: as people from economically lagging areas see their areas as both economically deprived and socially marginal, whereas people from rural areas will tend to focus on the social marginality of their area.

Our empirical analysis tests the effects of geographic contexts corresponding to the “places that don't matter.” At a highly localized level, we use population density to proxy rurality and the percentage of jobs in “routine” occupations to proxy economic deprivation (that is, the degree to which a local economy is reliant on low-skilled jobs, contra to the prevalence of high skill, professional jobs in the places that “do matter”). We find that both density and the proportion of routine jobs are linked to perceptions that one's area is not cared about by politicians. We then proceed to explore place-based resentments that are likely to be associated with lower trust. We find both subjective economic deprivation and feelings of social marginality predict lower trust, although we are cautious with regard to causal inference. As well as lower trust, population density predicts social marginality but not subjective economic deprivation, while routine jobs predict both subjective economic deprivation and social marginality. We find that the larger and more consistent effects, on both trust and the other outcomes, emerge from economic rather than urban-rural context.

Notwithstanding our concerns with his argument, our results support the focus of Rodríguez-Pose (2018) on the damaging effects of the unequal economic geography found in many countries. However, the “places that don't matter” manifest a multi-faceted sense of grievance, encompassing a sense of being at the margins of today's society. The response of political elites is liable to be more successful in increasing trust if it engages with this—not least because an economic response is unlikely to reduce rural distrust, which does not appear rooted in economic concerns. In our conclusion, we discuss what such a response might entail, and the pitfalls of current policy agendas, especially in the UK context.

While the “geography of discontent” (McCann, 2020) is widely referred to in discussions of contemporary politics, few studies directly or systematically test this thesis. Geographic divides are comparatively well-understood in some developing countries such as China, where despite a high trust baseline, urbanites tend to be more distrusting of government institutions (despite the greater affluence and education of city-dwellers), while ruralites trust the central government, but less so its local arms (e.g., Li, 2004; Wang and You, 2016).

In developed, democratic countries, examples of a rather sparser literature include Gidengil (1990), who finds significant regional variation in external efficacy in Canada, explained not by compositional factors but by “the region's location in the center-periphery system.” In “depressed” and “industrial” areas, people are lower in efficacy than in “centers” and “secondary centers.” Stein et al. (2019) similarly show that trust is lower in Norway's periphery than its center: yet this was not explained by any third variables such as economic performance (indeed, county-level GDP was not associated with greater trust)4. If there is a pattern to these results, it may be that at a local level economic performance and trust do not always march in lockstep.

However, highly unequal contexts (such as the US) may prime people to be more responsive to their economic environment. Studies concerning the relationship between inequality and political participation (e.g., Solt, 2008, 2010; Jaime-Castillo, 2009; Stockemer and Scruggs, 2012), explore the possibility that local context can reduce the willingness of individuals to participate. For example, Jacobs and Soss (2010) show that propensity to vote is substantially lower in low-income counties of the US, a finding which they interpret as reflecting a divide in “collective efficacy” including “beliefs in government responsiveness” between neighborhoods. Nonetheless, direct studies of these attitudes are lacking.

Another high-inequality context, the UK, is a modest exception in having more than one recent analysis of the “geography of discontent.” Jennings and Stoker (2016) identified two types of area, “cosmopolitan” and “backwater,” which they defined as having different levels of access to high-skilled jobs and connectedness to the global economy. More peripheral “backwaters,” perhaps surprisingly, were not higher in political discontent, measured by distrust in MPs/politicians and dissatisfaction with UK democracy, despite expressing higher levels of other grievances such as anti-immigration and Eurosceptic attitudes. According to this account the “places that don't matter” could be characterized by social conservatism, not political discontent. McKay (2019) follows a similar line of enquiry, finding that living in a lower-income area was associated with the belief that local people were not listened to, even controlling for individual economic circumstances and other demographics. Furthermore, McKay (2019) notes that low population density was also a significant predictor of discontent, reinforcing the importance of considering rurality and economic position independently. Given the discordance between the results of these alternative studies in the UK-context, and the relative lack of focus on urban-rural divides in political trust more generally, further investigation is needed. We address this gap by testing two key hypotheses relating to place and trust:

H1: The higher the proportion of routine jobs in an area, the lower the level of communotropic trust.

H2: The lower the population density of an area, the lower the level of communotropic trust.

We argue that these different place characteristics elicit a different mix of grievances, which may help us to understand the roots of their lack of trust. The next section explores the significance of social marginality to trust.

Although sparse, the empirical literature we have discussed suggests that economics and economic perceptions can only take us so far in understanding how context is related to trust attitudes. This leads us to a major point: we cannot understand geographic divisions in contemporary societies without a better model of the diversity of place-based grievances. The populism literature suggests one necessary extension; namely, understanding the social as well as the economic focus of grievances.

Weberian analysis draws attention to the “unequal award of social honor” to occupations or other social attributes, where we may observe differences between groups otherwise similar in their economic circumstances (Carella and Ford, 2020). The literature suggests that certain groups in society, defined along various axes, have developed a sense of status anxiety or threat. Two social trends are believed to have triggered anxieties. First, as Sandel (2020) and others have argued, status has become increasingly associated with merit—in turn, strongly associated with educational attainment (see e.g., Bovens and Wille, 2017). Those lacking in formal qualifications thus experience this anxiety or threat. Second, the growth of migration to Europe and North America from Africa, Asia and Latin America, and the challenges to “racial hierarchy” emerging from this, have been linked to anxiety or threat among white native majorities (e.g., Norris and Inglehart, 2019). Social marginality is thus closely linked to the concept of relative deprivation (Runciman, 1966): a social psychological concept which posits that “If comparisons to other people, groups, or even themselves at different points in time lead people to believe that they do not have what they deserve, they will be angry and resentful”—at least in some cases, directing their anger at the wider system (Smith et al., 2012)5.

These anxieties are associated with Brexit support (Antonucci et al., 2017) and, crucially, with political discontent. Gest et al. (2018) show that, for the UK and US, people feeling less socially central are also more likely to believe politicians don't care about people like them. Gidron and Hall (2020) find that, controlling for occupation, income, education and a variety of other factors, those lower in subjective social status were less satisfied with democracy and less trusting in politicians or parliament. In short, early indications are that attitudes around social status or centrality deserve more attention in political science, alongside perceptions of economic deprivation, whether these are understood as direct antecedents to (dis)trust or to develop alongside it.

In our view, it also seems clear that social status and significance is attached to places, as well as demographic groups. Moreover, this can evolve over time and these changes can evoke anxieties and threats of their own. Rodríguez-Pose uses Liverpool as an example of a place in economic decline, but it can also be noted for the rich social meanings attached to the city. Boland (2008) finds that locals were highly “sensitized to negative images that still cloud Liverpool in the national psyche,” from the “the unsavory behavior of local people (e.g., thieving ‘scallies’), place characteristics (e.g., violent, dirty, deprived), and a hangover from earlier decades (e.g., radicalism, riots).” This “territorial stigmatization” (Wacquant, 2008) is made apparent both in local-level interactions (Hall, 2003) and through the UK's national entertainment and news media environment, in which people are often confronted with the judgments of outsiders: since the 2000s, online “Crap Towns” surveys, where anyone can vote on and describe the worst places in Britain, have become fodder for bestselling books and the national news (Gilmore, 2013).

Political science research suggests that trust judgments are linked to these status threats as well as economic perceptions. However, these theories have not been extended to perceptions of place—even though people have an acute sense of their area's economic fortunes and position in society, as well as their own. Our next hypothesis tests this novel extension of the theory.

H3: The higher one's perceptions of economic deprivation and social marginality are, the lower the level of communotropic trust.

While the images and subjective status of places have long been a subject of urban development and management studies, they have rarely been considered in political science. While these literatures emphasize the local and specific, we are more interested in generalisable theory: what are the kinds of places in which people will tend to feel socially marginal, and why?

In many societies, social class is a powerful driver of how we see ourselves and others (Manstead, 2018). Loss of status among working-class people has been a major theme in academic discussions of political discontent and populist backlash. According to Gest (2017), his working-class interviewees in the outer London borough of Barking and Dagenham “sense a positional shift to the fringe of British society,” which is accompanied by the tendency for working-class individuals and groups to receive derogatory labels such as “chav” [also extensively discussed by Jones (2011)]. However, the Liverpool example points to how the (real and perceived) social marginalization of working-class people becomes a problem for places, also, as places are judged in large part through the image of their inhabitants.

For Hancock and Mooney (2013), “classed assumptions” are key to “territorial stigmatization in the contemporary UK.” In particular, the working-class council estate has played a role as a generic symbol of a low-status, “problem” area. This is again an example of where the meanings attached to places have changed over time: social housing in the UK became more “residualised” among low income groups since the 1970s (Farrall et al., 2016), facilitating a change toward negative perceptions around estates and their residents (Pearce and Vine, 2014) which are to some degree internalized by residents themselves (Pearce and Milne, 2010). This suggests that—whatever locally specific dynamics are at work–working-class spaces as a whole are liable to experience marginalization. The following hypothesis tests how this class dynamic structures not only economic experiences, but the sense of social marginality.

H4: The higher the proportion of routine jobs in an area, the more likely people are to perceive that their areas are economically deprived and socially marginal.

Our discussion so far of place and “social marginality” is strongly informed by an urban politics literature that, by its nature, excludes the rural. As the empirical literature suggests—and we predict—that these are low trust areas, it is vital to understand them, and what might explain these trust gaps compared to more densely populated areas. From US studies, there is an emerging literature on rural resentment: Cramer (2016) conducted extensive fieldwork in rural areas of Wisconsin which would be considered “white working class.” Discussions showed that respondents “intertwined place and class” using categories that “convey a perception of relative wealth and power”: “rural folks” being the game's losers. On some level, this is understandable on a purely economic basis: in the US, there is more deprivation in rural than urban areas (e.g., Albrecht et al., 2000). However, this was integrated with a sense of being “misunderstood and disrespected by city folks,” reflecting divides beyond the economic.

Quantitative research has since carried these insights forward, addressing concerns about their generalisability. Munis (2020) conducts a nationwide US survey intended to measure place resentment among rural areas, suburbs and towns toward cities/urban areas, and among cities toward small towns/rural areas. Munis finds a highly asymmetric pattern of resentments, wherein other areas are more resentful of cities than cities are of them. Furthermore, resentment of cities was even higher in rural areas than suburbs and towns, indicating that, as population density decreases, stronger feelings of marginality are observed.

In the UK, concepts of rural resentment specifically, and place resentment more generally, have not been explored in this level of depth in political science. Research in rural studies has nonetheless debated whether similar resentments are felt by ruralites in the UK. With the lack of a clear economic divide (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 2019), a different divide—rooted in culture—has been more often discussed. The Countryside Alliance protests of the early 2000s constituted an “identity politics centered on locale,” pointedly marching on cities in defense of a “rural way of life” made concrete in the issue of fox hunting (Brooks, 2020). However, the notion that this reflected the concerns of rural people in general has been widely disputed (Anderson, 2006). Furthermore, people in Britain seem somewhat wary of a divide narrative: in a recent survey, when primed to think about whether they live in an urban or a rural area, more people stated that they had “most/some things in common” with people in the opposite setting than said they had “not much/nothing in common,” although strikingly few (10%) said “most things in common” (YouGov, 2017).

More broadly, British society is widely represented in culture and in political rhetoric as diverse, inclusive and comfortable with change: for example, the 2012 Olympics hinged on a “multicultural nationalism” linked to the diversity of London (Winter, 2013). However, rural areas are far more ethnically homogenous than urban areas (Office for National Statistics, 2013), with high social trust that is specific to their neighborhood in-group (Office for National Statistics, 2016). These aspects of their environment and worldview may leave them feeling less central in this vision of contemporary British society, even if they harbor no specific resentments toward urban Britain per se, while residents of densely populated, diverse cities may feel the opposite, compared to other rural areas and even many towns.

While these sentiments—a divide in cultural custom or outlook—may be less intensely felt than American rural resentment, it is an important empirical question whether social grievances accompany the political in the UK context. We therefore test the following hypothesis:

H5: The lower the population density of an area, the more likely people are to perceive that their area is socially marginal.

Our data is from a nationally representative online survey of 1,634 adults carried out by Sky Data in Britain (England, Wales and Scotland) between the 20th and 30th October, 20176. The core feature, for our purposes, is the inclusion of measures adapted from those used by Gest et al. (2018). The measures were originally developed by Gest and colleagues through extensive fieldwork in white working-class communities in the US and Britain, and sought to measure relative deprivation in economic, social and political domains. We undertake two key adaptations: our questions ask people about the relative deprivation of their area, as well as them individually, and we interpret the social and political measures as referring to slightly different concepts to those of Gest et al. (2018).

We begin by discussing our measures of political trust:

• Political Trust: “Using the 0–10 scale below, how much do you think politicians care about (your area/people like you)?”

Following the logic of the earlier discussion, the former (“your area”) can be considered to denote communotropic trust, while the latter (“people like you”) corresponds to egotropic trust.

These survey items are novel (as they relate to place), and require justification as to the degree to which they can be equated with trust judgments. We consider these as measures which tap trust in the intrinsic commitment or benevolence of politicians toward the individual and to their area, classically understood as a dimension of trust alongside competence and others (Van Elsas, 2015)7. Kasperson et al. (1992) labeled this component “care,” and this is helpfully reflected in the wording of the questions. To the extent that a summary trust judgment exists about any object of trust, such as “politicians,” this is strongly influenced by judgments of caring (Van der Meer, 2010). Our trust items share some phrasing with typical “external efficacy” (EE) measures, but there are important (if subtle) differences8. First, EE items concentrate on how much politicians care about people's wishes and views, not how much they care about people: a patrician government which looked after people's best interests without adapting to their policy preferences could be trusted but also make people less efficacious. Secondly, EE attitudes are outcome-focused (Esaiasson et al., 2015) but it is not necessary to expect favorable outcomes to trust that politicians care. Rather than EE or summary trust judgments, we believe our items are best interpreted as specific trust in politicians' benevolence.

The communotropic item has specific benefits for our purposes. As well as measuring trust in this sense, it closely approximates what it means to feel one's area does or doesn't matter politically: thereby tapping the place-based sentiments of discontent discussed by Rodríguez-Pose (2018).

We expect the content of communotropic and egotropic judgments to be different, not only in the different experiences they draw on (individual vs. individuals in their environment and community) but in the different, narrower range of considerations which are cognitively accessible for communotropic trust (as people are less equipped to assess, say, opinion-policy congruence between their area and government than between themselves and government). Given we have single-item measures of egotropic and communotropic trust, it is unfortunately not possible to conduct analysis of discriminant validity between the items. However, two-thirds of respondents placed themselves at a different point on the (identically scaled) egotropic and communotropic items, suggesting that most people responded to the particularities of the items despite the fact these were asked together. Our other key variables are as follows:

• Economic Deprivation: “Using the 0–10 scale below, how financially well off do you consider your area compared to other areas in the United Kingdom?” (reversed so that 10 = “much less well off,” 0 = “much more well off”).

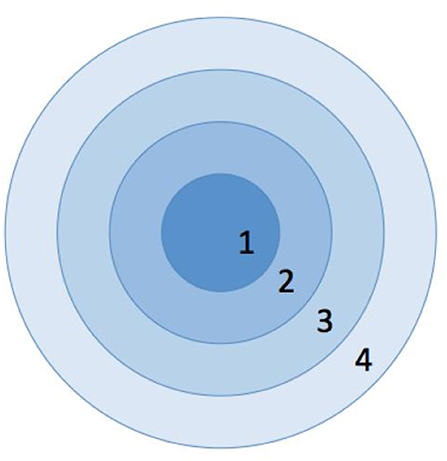

• Social Marginality: respondents were presented with a diagram of four concentric circles (see Figure A1 of the Appendix). The center circle was labeled with a “1” and the outer circle with a “4,” and respondents were told that the diagram depicted: “… how important particular areas are to your society. “1” represents those areas that are considered the most central and important to society, whereas “4” represents those areas that are considered the least central and important to society. Thinking about this, which group do you believe the area where you live belongs to?”9

Again, as a consequence of having single-item measures for these concepts, we cannot test discriminant validity between the communotropic measures of economic deprivation, social marginality and trust. For the purposes of transparency, we present a correlation matrix of these variables, and the egotropic trust variable, in Table A1 of the Appendix.

In order to undertake contextual analysis, respondents are matched at the postcode district level to official statistical measures. As a proxy for economic deprivation, we use data on the occupational composition of each area in 2011 (the date of the last census)10. The National Statistics Socio-economic classification (NS-SEC) breaks occupations down into eight analytic classes. We collapse the lower end of the NS-SEC scheme into a “routine jobs” measure that combines semi-routine occupations, routine-occupations and those who have never worked or are long-term unemployed. We then calculate this as a proportion of usual residents aged 16 to 74 in each postcode district. There is large geographic variation: in EC4A, a Central London location home to the headquarters of Goldman Sachs International, just 3% work in routine jobs, while in the Easterhouse area of Glasgow, 75% are classified as doing so11.

Second, owing to the lack of an official urban-rural indicator at the postcode district level (the most fine-grained areal unit within which we can locate respondents) we use a proxy measure for how rural or urban an area is. We do this by collecting data on the population density of each area, dividing its estimated total population (using mid-year population estimates at the time of the survey in 2017) by its area in hectares. Although the literature has noted certain problems with such a proxy, rural-urban classification by bodies such as the OECD and European Commission is still predominantly or solely based on the population density of areas (Pagliacci, 2017). This continuous measure also has the advantage of enhanced ability to detect a non-linear relationship between rural-urban context and the dependent variable(s). To reduce skew, for use in all analysis, we log-transform this measure after adding a constant of 1, such that near-zero values are transformed to near-zero on the logged scale and the scale runs to a maximum of 5.3.

In testing contextual effects, it is generally appropriate to use multilevel regression. We utilize multilevel models (with postcode districts at the level-2 unit) where the macro indicators are introduced as explanatory variables, and cluster standard errors where they are not. We establish for each of our outcomes that there is variation to be explained at the postcode district level before introducing macro-indicators. As there are a small number of observations per group (1.5), it could be questioned whether this approach is appropriate, though Bell et al. (2010) show that unbiased point estimates and standard errors can still be obtained with sparse data structures. We replicate our analysis with single-level models and find no substantive differences, increasing our confidence in our findings.

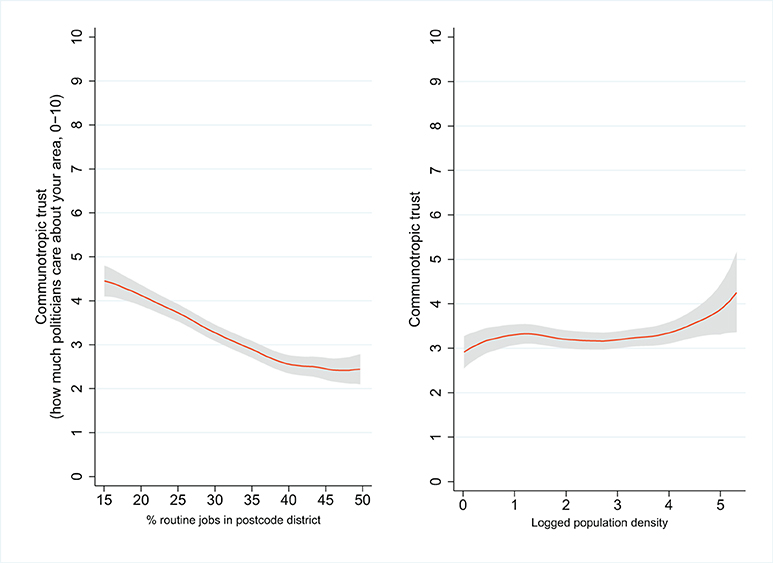

To begin to understand the relationship between objective context and our outcomes, we fit a series of local polynomial regressions. Firstly, we explore the relationship between the key outcome variable, what we call communotropic trust, and our two measures of context12. These results are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Graphs of local polynomial regressions of routine jobs and population density on communotropic trust.

This analysis shows that, as the proportion of routine jobs in an area increases, people tend to be lower in communotropic trust: although in the most deprived communities the effect may slightly diminish. Meanwhile, as population density increases, people's views are not quite so negative, with a marked increase in trust in the most densely populated postcode districts.

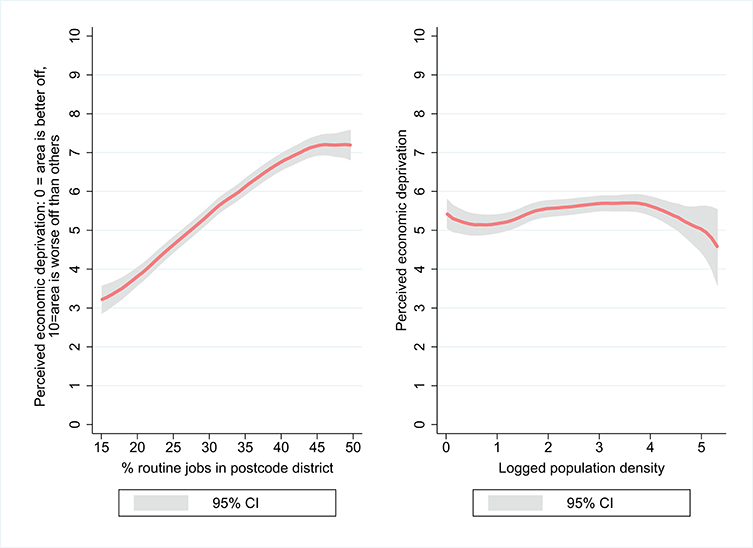

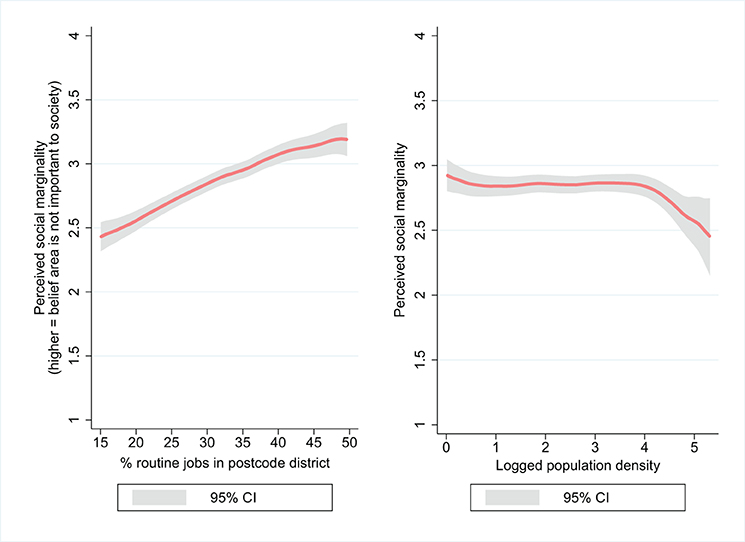

We can also explore the relationship between these contexts and perceptions of what we call “economic” and “social” deprivation. Figures 2, 3 apply the same method to these alternative measures.

Figure 2. Graphs of local polynomial regressions of routine jobs and population density on perceived economic deprivation.

Figure 3. Graphs of local polynomial regressions of routine jobs and population density on perceived social marginality.

As expected, communities with higher proportions of routine jobs have a strong tendency to view their area as worse off than others. Beyond this, they also have stronger feelings of social marginality. In contrast, less densely populated areas, often assumed to be “places that don't matter” in economic terms, are no more likely to perceive themselves as worse off compared to other areas. However, they do have a stronger sense of social marginality, feelings of social unimportance, than highly dense areas.

This initial analysis begins to indicate support for our hypotheses around contextual effects (H1-H2, H4-H5). However, to explore this properly, we must control for individual-level demographics and political attitudes.

We next run a series of regression models, including a range of individual-level controls which we keep consistent across the models.

Firstly, we control for which of the UK's constituent nations the respondent lives in, as these are correlated with both the contextual variables and plausibly with economic, social and political grievances.

Next, we control for a number of demographic predictors based on the existing studies of economic, social and political discontent and grievances (Inglehart and Norris, 2016). We include gender, as men are thought to be more inclined to believe they are losing status in today's society and to be leading the “backlash” against a political order which enables this loss. We include a dummy for ethnicity (white vs. non-white), as white people appear more inclined to a similar set of beliefs, perhaps as a direct consequence of rising numbers and perceived socio-political importance of ethnic minorities. In addition, we include an age variable, measured continuously in years, as older people are widely perceived to feel more discomfited by these changes.

We also control for the vote intention of respondents, as an approximation of both their level of political engagement and their underlying partisan preferences. Less engaged voters may be precisely those most inclined to the grievances measured here: voters for the radical right UKIP party have been noted for their greater social, economic and political deprivation (Gest et al., 2018), while there is a well-known “winner-loser effect” wherein major party supporters are more politically dissatisfied when their party is out of power (Anderson et al., 2005). We also control for the respondent's Leave/Remain vote in the 2016 EU referendum. The relationship between economic, social and political grievances and people's 2016 votes is widely debated (see Sobolewska and Ford, 2020, for a summary). However, the fact that this study took place in a context where the referendum was the last salient electoral event in voters' minds means that Remainers could behave like typical political “losers” and show greater dissatisfaction. Voting at elections is heavily geographically polarized in the UK context, and this extended to the EU referendum, so correlations with the contextual variables are also likely.

The output for each model, including these various controls, is displayed in Table 1. Below, we discuss these results one-by-one.

Model 1 tests the effects of each contextual variable on communotropic trust. The coefficient of routine jobs is negative and highly statistically significant, meaning that the more routine jobs in a postcode district, the less likely people are to believe politicians care about the area. Meanwhile, the coefficient for (logged) population density is positive: in less dense areas, communotropic trust is therefore lower. These results conform with the bivariate correlations shown above, and further support Hypotheses 1 and 2.

Model 2 adds a control for egotropic trust the sense that politicians care about people individually. It is important that the contextual effects should survive the addition of this variable because the theory is that people develop a distinctive sense of their place not mattering. Furthermore, we are conscious that our models do not include other demographics key to the “left-behind” story, principally education and social class, which may be correlated with contextual factors but were not collected as part of the survey. These demographics should only be associated with the DV through egotropic trust, so controlling for egotropic trust also minimizes omitted variable bias that might occur due to absent individual-level demographic factors.

We observe in column 2 that these effects are resilient, increasing our confidence in rejecting the null for both Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2. This model provides the best grounds for evaluating the substantive size of contextual effects. A one standard deviation increase in routine jobs is associated with an 0.19 standard deviation decrease in communtropic trust, while a one standard deviation increase in (logged) population density is associated with a 0.08 standard deviation increase in communotropic trust. Therefore, while both make a meaningful contribution to perceptions, the effect of economic rather than urban-rural context appears more substantial on how much people feel politicians care about their area.

Interestingly, effects of election/referendum voting behaviors in Model (1) are by contrast attenuated or eliminated, suggesting that effects observed in Model (1) are a spill-over of their effects on egocentric trust. By contrast, we find that an age effect emerges whereby older people are more likely to be low in communotropic trust when egocentric trust is held constant.

In Model 3, we test for an effect of perceived economic deprivation and social marginality on communotropic trust, controlling for other factors. Our theory, as set out by Hypothesis 3, is that each of these will be associated with lower communotropic trust, though we must reiterate that this is not a causal claim. We find, in column 3, that this is indeed the case. However, the (standardized) effect of economic deprivation is more than twice that of social marginality. Among our control variables, the coefficients for nation are worth noting. Controlling for economic deprivation and social marginality, communotropic trust is higher in Wales and lower in Scotland than would be expected.

In Models 4 and 5, we use perceived economic deprivation and social marginality as outcomes. As our earlier analysis suggested, column 4 indicates that the proportion of routine jobs in an area is a strong predictor of feelings of economic deprivation, but population density is not a predictor. For social marginality, both contextual variables are predictors. Together, these results support Hypotheses 4 and 5. For these significant effects, the effect sizes are large. A one standard deviation increase in the share of routine jobs in an area is associated with an 0.47 standard deviation increase in perceived economic deprivation and a 0.26 standard deviation increase in perceived social marginality. Meanwhile, a one standard deviation increase in population density, while not associated with perceived economic deprivation, is associated with a 0.08 standard deviation decrease in perceived social marginality.

Among our control variables, the patterns of partisan support and referendum voting that are linked to low communtropic trust are also linked to social and economic deprivation. Namely, these are voting Labour, UKIP and Leave, but the greater dissatisfaction is also observed among undecided voters and non-voters.

Note that across all models, individual-level demographics have virtually zero capacity to predict the belief that one's area is ignored, or perceptions of social marginality. This is intriguing, in that particular demographic groups have been widely believed to be hotbeds of political and social discontent more generally. Namely, older white men are often considered to constitute a “left-behind” cohort whose dissatisfaction with a changing social and political order has, in many countries, found expression in voting for the radical right (Inglehart and Norris, 2016). Yet neither gender nor ethnicity are significant in even one model, while age is significant in just one. However, it could be the case that our models do not include other demographics key to the left-behind story, principally education and social class. We must therefore be cautious: we cannot say that these attitudes are entirely about places not people, but our analysis gives stronger support to the former, owing to strong and consistent effects of context on perceptions of the economic, social and political standing of one's area.

Political events of recent years have drawn attention to the relationship between geography and political attitudes and behaviors. In many studies, broad claims are made with direct relevance to the role of political trust (and discontent), yet the links between geography and trust are still poorly understood. We focus on Rodríguez-Pose (2018), both as an influential study in its own right and one indicative of broader strains in analysis and commentary. We have three concerns relating to most existing studies that relate to this topic: inferring attitudes from voting behaviors (since not all populist right voters are discontented voters); assuming a single axis of geographic division (since not all cities are economically vibrant, and not all towns are lagging); and the neglect of place-based grievances other than the economic (since we must also consider people's sense of being at society's fringes). This article addresses these concerns through an enhanced theoretical framework, and an empirical analysis testing the attitudinal component of the framework.

We offer novel and original survey data that asks questions about place to tap multiple sources of grievance (economic, social, political) which are important to our framework, and allows us to analyse the effects of different contexts on these grievances. Our results speak to the need to unpick the “places which don't matter.” These are a diverse group of places in their own right, reaching a similar (discontented) outlook on politics for different reasons. To recap our results, we find that economically worse-off areas and more rural areas, as measured according to our proxies, are significantly lower in communotropic trust—that is, less likely to believe that politicians care about their area. These results hold controlling for various individual-level demographics and political characteristics, and holding constant egotropic trust, or a personal sense of being uncared for by politicians. People who see their areas as more economically and socially deprived are also lower in communotropic trust. This could suggest that these perceptions are a relevant basis for trust judgments, although observational data does not allow us to be certain in making this causal inference. In turn, in line with expectations, population density predicts feelings of social marginality but not subjective economic deprivation, while the proportion of routine jobs in an area predicts both subjective economic deprivation and social marginality. These results are consistent with each of our five hypotheses.

Our claims must be clearly qualified here, for several reasons. First, our original constructs are tapped by single items and were not fielded with any conventional trust items, making it difficult to ascertain an attitude of communotropic trust and its precise relationship to broader trust judgments. The wording of the items encourage a focus on perceptions of benevolence over other dimensions of trustworthiness, such as competence and integrity and it is possible to believe that politicians care for one's community while thinking that they cannot be trusted to deliver for it. However, this study opens the door for further research (both quantitative and qualitative) on how people trust X to do Y for Z—Z being their community or other relevant in-group.

We must also note that our empirical analysis is bound to a specific place and time. While other research (e.g., Rodríguez-Pose, 2018) suggests the UK is indicative of wider trends, the theories here should be tested in other countries and regions. We expect that the specific geographical predictors could change in different country-contexts, and researchers should be sensitive how the same types of places might be experienced differently in these varied contexts. For example, studies suggest that in the developing world trust may be higher in rural than in urban areas (Brinkerhoff et al., 2018; Carreras and Bowler, 2019): this contrast with studies such as ours and the US rural resentment literature is a compelling puzzle for future investigation. Temporally, our opinion data was collected at a snapshot in time (October 2017) during a turbulent period in British politics. Many accounts, including Rodríguez-Pose (2018) posit a long-term geographical polarization, which we cannot speak to. If such a polarization has taken place, however, our analysis leads us to expect that the changing status attached to places might be as important as economic change.

The attitudes we explore here have come to the fore owing to significant disruptions to mainstream politics, but their effects on political behavior remain to be demonstrated. Rodríguez-Pose (2018) argues that right-wing populists have been the beneficiaries of loss of trust among people in the “places that don't matter.” We consider this to be plausible: political distrust is often though not always linked to radical right voting (Rooduijn, 2018). Furthermore, right-wing populists may be effective at capitalizing on underlying place based-grievances both economic and socio-cultural. For example, Trump's promise to bring back the mines to places such as Minnesota's “Iron Range” combined an economic message with an appeal to the masculinity associated with the industry framed in opposition to “elite urban environmentalists” (Kojola, 2019). However, other possibilities should be explored by researchers, including whether radical left parties can benefit, whether people simply disengage (Soss and Jacobs, 2009), or indeed, whether mainstream parties can adapt to these challenges and secure voter loyalty. To understand why mainstream parties lose diffuse support in particular places will also involve engaging with party images: how do parties become associated with places and types of places in the minds of voters? And, through local campaigning or political communication and messaging, can parties reshape these images?

Despite these unresolved puzzles, we join the literature in arguing that geographic divides present a problem for mainstream politics in two respects: risking loss of (certain forms of) trust in political systems and potentially eroding support for mainstream parties. However, we should not ignore the efforts that mainstream parties and politicians have made, and are currently making, to (re)connect with the places that are said not to matter. Returning to the example of Liverpool, the Conservative Michael Heseltine was made “minister for Merseyside” in the 1980s and presided over a programme of urban regeneration, while New Labour showed “commitment to regional policy” focused on “pockets” of deprivation (Dalingwater, 2011). Likewise, the incumbent Conservative government, as of 2021, has made much of its agenda for “leveling up” areas of the country that have experienced less economic growth. Our study, like Rodríguez-Pose (2018), suggests that this focus on economic grievance is valuable. However, it has been widely questioned whether these policies will deliver effective outcomes or follow impartial and transparent processes, both of which are typically understood as critical for trust (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, 2001). Any genuine process for healing divides must give the impression of the “care” which, based on our data, people plainly believe is lacking.

As evidenced by our findings, politicians must also recognize that these are areas that, beyond their economic grievances, feel pushed to the margins of contemporary society (indeed, in rural areas, only the latter grievance appears relevant). We have discussed this social marginality as a perception of being judged (negatively) by outsiders, a problem for which there is no obvious policy prescription. However, these grievances connect with trust because the key image of government in people's lives is a national government consisting of outsiders. People express higher trust the more localized the institution that they are asked about (Gerring and Veenendaal, 2020), partly because the political actors involved are “like us” not “like them,” and expected to be more sympathetic to and knowledgeable about their constituents. Decentralization may thus curb the damaging effects of place-based grievances on national politics.

To conclude, we regard the increasing focus on place and politics as a clear positive, and have added to the growing body of knowledge on the topic. We have shown that, in a country held up as indicative of geographic divides, different local contexts are associated with different kinds of grievance, and this appears to have consequences for political trust. We have pointed out certain pitfalls to avoid in subsequent research, and pointed the way to a research agenda that might produce vital knowledge and even inform policy debates. If the “places that don't matter” truly matter to political scientists, then we must make every effort to develop our understanding of them.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

This research was conducted as part of the Trust and Trustworthiness in National and Global Governance (TrustGov)' project, supported by Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) award ES/S009809/1.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. ^As discussed in section Data and Method.

2. ^According to Rogers (2014), communotropic considerations are conceptually distinguished from egotropic considerations by being “other-regarding”—but the “others” are those in your geographic community (however the individual defines this) who you are more likely to consider your in-group than others outside it. Rogers goes on to show that “communotropic” perceptions of the economy are predicted by objective economic conditions in the area, but egotropic perceptions are not—thus they are distinguished at an empirical as well as conceptual level. He further finds that “communtropic” economic perceptions, controlling for national and personal (egotropic) perceptions, contribute to approval of the president and of Congress, showing that people weigh communotropic considerations in making judgments about political actors.

3. ^For the purposes of clarity, “communotropic trust” does not refer to the tendency to trust people within one's community: i.e., it is not a form of social trust, but a form of political trust.

4. ^Gidengil (1990) and Stein et al. (2019) frame and interpret their results with regard to center-periphery divides. However, while we agree that such divides could be significant, they are distinct from the divides centered by Rodríguez-Pose (2018) and therefore we do not pursue the study of their effects. These papers are discussed to give a full account of the literature of the geography of discontent.

5. ^Despite this conceptual link, we choose not to frame our contribution in terms of relative deprivation primarily because our items do not demand that respondents make comparisons between their ingroup and other (specific) reference groups (which is the core analytical approach of relative deprivation theory), but to offer their sense of its status within society as a whole. It remains unclear which intergroup comparisons are likely to be consequential for anti-system attitudes such as distrust as opposed to prejudice against the outgroup (Smith et al., 2012).

6. ^Sky Data is a member of the British Polling Council.

7. ^We understand this as identical to benevolence, which is a widely-used term in trust studies.

8. ^e.g., the American National Election Study uses two items, “People like me don't have any say about what the government does” (NOSAY); and “I don't think public officials care much what people like me think” (NOCARE). The reliability and validity of external efficacy items was notably discussed by Craig et al. (1990), who also show that “External efficacy is distinguished from political trust”.

9. ^The dataset contains equivalent “egotropic” measures of economic deprivation and social centrality, but these are not used in the analysis.

10. ^We use a proxy due to the somewhat unintuitive nature of the official deprivation statistics in the UK. These measure deprivation in a deliberately multidimensional way according to whether households meet one or more of four conditions relating to employment, education, health and disability and housing. Using such a measure in a regression would mean that the “moving part” driving the relationship would be hard to pin down. We confirm that at the postcode district level, our proxy measure correlates very highly with multidimensional deprivation: for example, at .9 with deprivation measured in two dimensions.

11. ^Easterhouse is, notably, the neighborhood which, in 2002, was identified by former Conservative leader Iain Duncan Smith as an example of an area that had been failed by previous Conservative governments (Collins, 2002).

12. ^For the “routine jobs” variable, the graphs below do not use the whole range of data due to large confidence intervals at each extreme: only the 5–95 percentile range is used.

Albrecht, D. E., Albrecht, C. M., and Albrecht, S. L. (2000). Poverty in nonmetropolitan America : impacts of industrial, employment, and family structure variables. Rural Soc. 65, 87–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-0831.2000.tb00344.x

Anderson, A. (2006). Spinning the rural agenda: the countryside alliance, fox hunting and social policy. Soc. Policy Adm. 40, 722–738. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9515.2006.00529.x

Anderson, C., Blais, A., Bowler, S., Donovan, T., and Listhaug, O. (2005). Loser's Consent. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ansell, B., and Adler, D. (2019), Brexit and the politics of housing in Britain. Polit. Q. 90, 105–116. doi: 10.1111/1467-923X.12621

Antonucci, L., Horvath, L., Kutiyski, Y., and Krouwel, A. (2017). The malaise of the squeezed middle: challenging the narrative of the “left behind” brexiter. Compet. Change 21, 211–229. doi: 10.1177/1024529417704135

Becker, S. O., Fetzer, T., and Novy, D. (2017). Who voted for Brexit? A comprehensive district-level analysis. Econ. Policy 32, 601–650. doi: 10.1093/epolic/eix012

Bell, B. A., Morgan, G. B., Kromrey, J. D., and Ferron, J. M. (2010). The impact of small cluster size on multilevel models: a Monte Carlo examination of two-level models with binary and continuous predictors. JSM Proc. 1, 4057–4067. Available online at: http://www.asasrms.org/Proceedings/y2010/Files/308112_60089.pdf

Boland, P. (2008). The construction of images of people and place: labelling Liverpool and stereotyping scousers. Cities 25, 355–369. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2008.09.003

Bolet, D. (2020). Local labour market competition and radical right voting: evidence from France. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 59, 817–841. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12378

Bovens, M., and Wille, A. (2017). Diploma Democracy. The Rise of Political Meritocracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198790631.001.0001

Brinkerhoff, D. W., Wetterberg, A., and Wibbels, E. (2018). Distance, services, and citizen perceptions of the state in rural Africa. Governance 31, 103–124. doi: 10.1111/gove.12271

Brooks, S. (2020). Brexit and the politics of the rural. Sociol. Ruralis. 60, 790–809. doi: 10.1111/soru.12281

Carella, L., and Ford, R. (2020). The status stratification of radical right support: reconsidering the occupational profile of UKIP's electorate. Electoral Stud. 67:102214. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102214

Carreras, M., and Bowler, S. (2019). Community size, social capital, and political participation in Latin America. Polit. Behav. 41, 723–745. doi: 10.1007/s11109-018-9470-8

Carreras, M., Irepoglu Carreras, Y., and Bowler, S. (2019). Long-term economic distress, cultural backlash, and support for brexit. Comp. Polit. Stud. 52, 1396–1424. doi: 10.1177/0010414019830714

Colantone, I., and Stanig, P. (2018). Global competition and brexit. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 112, 201–218. doi: 10.1017/S0003055417000685

Collins, V. (2002, March 23). How Iain Duncan Smith came to easterhouse and left with a new vision for the tory party. The Herald.

Craig, S. C., Niemi, R. G., and Silver, G. E. (1990). Political efficacy and trust: a report on the NES pilot study items. Polit. Behav. 12, 289–314. doi: 10.1007/BF00992337

Cramer, K. J. (2016). The Politics of Resentment. Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226349251.001.0001

Cutts, D., Goodwin, M., Heath, O., and Surridge, P. (2020). Brexit, the 2019 general election and the realignment of British politics. Polit. Q. 91, 7–23. doi: 10.1111/1467-923X.12815

Dalingwater, L. (2011). Regional performance in the UK under new labour. Observatoire de la société Britannique 10, 115–136. doi: 10.4000/osb.1151

Department for Environment Food Rural Affairs. (2019). Rural Poverty—to 2017/18. London: Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/rural-poverty (accessed January 12, 2020).

Dijkstra, L., Poelman, H., and Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2020). The geography of EU discontent. Reg. Stud. 54, 737–753. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2019.1654603

Esaiasson, P., Kölln, A. K., and Turper, S. (2015). External efficacy and perceived responsiveness—similar but distinct concepts. Int. J. Publ. Opin. Res. 27, 432–445. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edv003

Evans, J., Norman, P., Gould, H., Ivaldi, G., Dutozia, J., Arzheimer, K., et al. (2019). Sub-national context and radical right support in Europe: policy brief. University of Nice. Available online at: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02088993 (accessed December 15, 2020).

Farrall, S., Hay, C., Jennings, W., and Gray, E. (2016). Thatcherite ideology, housing tenure and crime: the socio-spatial consequences of the right to buy for domestic property crime. Br. J. Criminol. 56, 1235–1252. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azv088

Gavenda, M., and Umit, R. (2016). The 2016 Austrian presidential election: a tale of three divides. Reg. Federal Stud. 26, 419–432. doi: 10.1080/13597566.2016.1206528

Gerring, J., and Veenendaal, W. (2020). Population and Politics: The Impact of Scale. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781108657099

Gest, J. (2017). The New Minority: White Working Class Politics in an Age of Immigration and Inequality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gest, J., Reny, T., and Mayer, J. (2018). Roots of the radical right: nostalgic deprivation in the United States and Britain. Comp. Polit. Stud. 51, 1694–1719. doi: 10.1177/0010414017720705

Geurkink, B., Zaslove, A., Sluiter, R., and Jacobs, K. (2020). Populist attitudes, political trust, and external political efficacy: old wine in new bottles? Polit. Stud. 68, 247–267. doi: 10.1177/0032321719842768

Gidengil, E. (1990). Centres and peripheries: the political culture of dependency*. Can. Rev. Sociol. 27, 23–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-618X.1990.tb00443.x

Gidron, N., and Hall, P. A. (2020). Populism as a problem of social integration. Comp. Polit. Stud. 53, 1027–1059. doi: 10.1177/0010414019879947

Gilmore, A. (2013). Cold spots, crap towns and cultural deserts: the role of place and geography in cultural participation and creative place-making. Cult. Trends 22, 86–96. doi: 10.1080/09548963.2013.783174

Gimpel, J. G., Lovin, N., Moy, B., and Reeves, A. (2020). The Urban–rural gulf in American political behavior. Polit. Behav. 42, 1343–1368. doi: 10.1007/s11109-020-09601-w

Hall, D. . (2003). “Images of the city,” in Reinventing the City?: Liverpool in Comparative Perspective, ed R. Munck (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press), 191–210. doi: 10.5949/liverpool/9780853237976.003.0011

Hancock, L., and Mooney, G. (2013). “Welfare Ghettos” and the “broken society”: territorial stigmatization in the contemporary UK. Housing Theory Soc. 30, 46–64. doi: 10.1080/14036096.2012.683294

Hibbing, J. R., and Theiss-Morse, E. (2001). Process preferences and American politics: what the people want government to be. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 95, 145–153. doi: 10.1017/S0003055401000107

Inglehart, R., and Norris, P. (2016). Trump, Brexit, and the Rise of Populism: Economic Have-Nots and Cultural Backlash. HKS Working Paper No. RWP16-026. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2818659

Jacobs, L. R., and Soss, J. (2010). The politics of inequality in America: a political economy framework. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 13, 341–364. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.041608.140134

Jaime-Castillo, A. M. (2009). “Economic inequality and electoral participation: a cross-country evaluation,” in Comparative Study Of The Electoral Systems (CSES) Conference (Toronto, ON). doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1515905

Jennings, W., and Stoker, G. (2016). The bifurcation of politics: two Englands. Polit. Q. 87, 372–382. doi: 10.1111/1467-923X.12228

Kasperson, R. E., Golding, D., and Tuler, S. (1992). Social distrust as a factor in siting hazardous facilities and communicating risks. J. Soc. Issues 48, 161–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1992.tb01950.x

Kojola, E. (2019). Bringing back the mines and a way of life: populism and the politics of extraction. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 109, 371–381. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2018.1506695

Li, L. (2004). Political trust in rural China. Mod. China 30, 228–258. doi: 10.1177/0097700403261824

Manstead, A. S. (2018). The psychology of social class: how socioeconomic status impacts thought, feelings, and behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 57, 267–291. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12251

McCann, P. (2020). Perceptions of regional inequality and the geography of discontent: insights from the UK. Reg. Stud. 54, 256–267. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2019.1619928

McKay, L. (2019). ‘Left behind’ people, or places? The role of local economies in perceived community representation. Electoral Stud. 60:102046. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.010

Monnat, S. M., and Brown, D. L. (2017). More than a rural revolt: landscapes of despair and the 2016 Presidential election. J. Rural Stud. 55, 227–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.08.010

Munis, B. K. (2020). Us over here versus them over there…literally: measuring place resentment in American politics. Polit. Behav. 1–22. doi: 10.1007/s11109-020-09641-2

Mutz, D. C., and Mondak, J. J. (1997). Dimensions of sociotropic behavior: group-based judgements of fairness and well-being. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 41, 284–308. doi: 10.2307/2111717

Norris, P., and Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781108595841

Office for National Statistics (2013). 2011 Census Analysis - Comparing Rural and Urban Areas of England and Wales. London: Office for National Statistics. Available online at: https://www.basw.co.uk/system/files/resources/basw_41648-6_0.pdf (accessed December 15, 2020).

Office for National Statistics (2016). Social Capital Across the UK: 2011 to 2012. London: Office for National Statistics. Available online at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/articles/socialcapitalacrosstheuk/2011to2012 (accessed December 15, 2020).

Pagliacci, F. (2017). Measuring EU urban-rural continuum through fuzzy logic. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 108, 157–174. doi: 10.1111/tesg.12201

Pearce, J., and Milne, E. J. (2010). Participation and Community on Bradford's Traditionally White Estates: A Community Project, York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Pearce, J., and Vine, J. (2014). Quantifying residualisation: the changing nature of social housing in the UK. J. Housing Built Environ. 29, 657–675. doi: 10.1007/s10901-013-9372-3

Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2018). The revenge of the places that don't matter (and what to do about it). Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 11, 189–209. doi: 10.1093/cjres/rsx024

Rodríguez-Pose, A., Lee, N., and Lipp, C. (2020). Golfing with Trump: social capital, decline, inequality, and the rise of populism in the US. LSE Research Online Documents on Economics 106530, London School of Economics and Political Science, LSE Library.

Rogers, J. (2014). A communotropic theory of economic voting. Electoral Stud. 36, 107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2014.08.004

Rooduijn, M. (2018). What unites the voter bases of populist parties? Comparing the electorates of 15 populist parties. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev. 10, 351–368. doi: 10.1017/S1755773917000145

Runciman, W. G. (1966). Relative Deprivation and Social Justice: A Study of Attitudes to Social Inequality in Twentieth-Century England. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Sandel, M. (2020). The Tyranny of Merit: What's Become of the Common Good? New York, NY: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Scala, D. J., and Johnson, K. M. (2017). Political polarization along the rural-urban continuum? The geography of the presidential vote, 2000–2016. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 672, 162–184. doi: 10.1177/0002716217712696

Schwander, H., and Manow, P. (2017). It's not the economy, stupid! Explaining the electoral success of the German right-wing populist AfD Explaining the electoral success of the German right-wing populist AfD. CIS Working Paper 94, University of Zurich. Available online at: https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/143147/ (accessed December 15, 2020).

Smith, H. J., Pettigrew, T. F., Pippin, G. M., and Bialosiewicz, S. (2012). Relative deprivation: a theoretical and meta-analytic review. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 16, 203–232. doi: 10.1177/1088868311430825

Sobolewska, M., and Ford, R. (2020). Brexitland: identity, diversity and the reshaping of British politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781108562485

Solt, F. (2008). Economic inequality and democratic political engagement. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 52, 48–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00298.x

Solt, F. (2010). Does economic inequality depress electoral participation? Testing the Schattschneider hypothesis. Polit. Behav. 32, 285–301. doi: 10.1007/s11109-010-9106-0

Soss, J., and Jacobs, L. R. (2009). The place of inequality: Non-participation in the American polity. Political Science Quarterly. 124, 95–125.

Stein, J., Buck, M., and Bjørnå, H. (2019). The centre–periphery dimension and trust in politicians: the case of Norway. Territory Polit. Governance. 1–19. doi: 10.1080/21622671.2019.1624191

Stockemer, D., and Scruggs, L. (2012). Income inequality, development and electoral turnout–new evidence on a burgeoning debate. Electoral Stud. 31, 764–773. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2012.06.006

Van der Meer, T. (2010). In what we trust? A multi-level study into trust in parliament as an evaluation of state characteristics. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 76, 517–536. doi: 10.1177/0020852310372450

Van Elsas, E. (2015). Political trust as a rational attitude: a comparison of the nature of political trust across different levels of education. Polit. Stud. 63, 1158–1178. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12148

Wacquant, L. (2008). Urban Outcasts: A Comparative Sociology of Advanced Marginality. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Wang, Z., and You, Y. (2016). The arrival of critical citizens: decline of political trust and shifting public priorities in China. Int. Rev. Sociol. 26, 105–124. doi: 10.1080/03906701.2015.1103054

Wilkinson, W. (2019). The Density Divide: Urbanization, Polarization, and Populist Backlash. Research paper. Washington, DC: Niskanen Center.

Winter, A. (2013). Race, multiculturalism and the ‘progressive’ politics of London 2012: passing the ‘Boyle test.’ Sociol. Res. Online 18, 137–143. doi: 10.5153/sro.3069

YouGov (2017). Daily Question: Arts and Culture. Available online at: https://yougov.co.uk/topics/arts/survey-results/daily/2017/05/10/7f020/2 (accessed January 1, 2020).

Figure A1. Social centrality question. Above is a diagram which represents how central and important particular areas are to your society. “1” represents those areas that are considered the most central and important to society, whereas “4” represents those areas that are considered the least central and important to society. Thinking about this, which group do you believe the area where you live belongs to?

• 1 “Most important/central” (1)

• 2 (2)

• 3 (3)

• 4—”Least important/central” (4)

Keywords: political trust, political geography, economic inequality in democracies, urban-rural divide, British politics

Citation: McKay L, Jennings W and Stoker G (2021) Political Trust in the “Places That Don't Matter”. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:642236. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.642236

Received: 15 December 2020; Accepted: 26 March 2021;

Published: 26 April 2021.

Edited by:

James Weinberg, The University of Sheffield, United KingdomReviewed by:

Reinhard Heinisch, University of Salzburg, AustriaCopyright © 2021 McKay, Jennings and Stoker. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lawrence McKay, bC5hLm1ja2F5QHNvdG9uLmFjLnVr

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.