Abstract

The present study examined undergraduate EFL learners’ preferences for three different types of written corrective feedback: direct, indirect, and metalinguistic. The participants were undergraduate students from various colleges at Hail University. A mixed-methods approach was employed, with data collected through a questionnaire and semi-structured interviews. The researcher sought to investigate learners’ preferences for direct, indirect, or metalinguistic written corrective feedback and the reasons behind these preferences. The results showed that most learners preferred direct written corrective feedback because it helped them improve their writing skills and was easier to understand. While the quantitative findings indicated that learners were uncertain about metalinguistic written corrective feedback, the qualitative responses suggested a preference for it, as it was perceived as an interesting, memorable, and enjoyable learning experience that motivated them to learn. The findings also revealed that learners did not prefer indirect written corrective feedback. The current study involves learners’ preferences which acknowledges the importance of their opinion in the learning process, leading to more effective and personalized language learning experiences. Future research could explore students’ preferences for written corrective feedback in relation to how new technology might affect these preferences.

Introduction

This paper investigates undergraduate EFL learners’ preferences for different types of written corrective feedback (WCF): direct, indirect, and metalinguistic. According to Ellis (2009), direct corrective feedback involves correcting errors directly and providing the correct answer. Indirect corrective feedback indicates the presence of an error but does not provide the correction, whereas metalinguistic corrective feedback offers clues to help students identify the type of mistake without giving the answer (e.g., using the acronym “SV” to indicate an error in subject–verb agreement).

Many studies, such as those by Ghandi and Maghsoudi (2014) and Ferris and Roberts (2001), have examined the effects of WCF on students’ performance without considering their preferences. Although some studies have investigated learners’ preferences for WCF, they have not examined all three types—direct, indirect, and metalinguistic—together (Al-Hajiri and Al-Mahrooqi, 2013). Other studies have focused on the preferences of school students rather than undergraduates (e.g., Rasool et al., 2023). Additionally, Li and He (2017) compared students’ preferences with teachers’ practices but did not examine learners’ reflections or reasons for their choices. Further, Salami and Khadawardi (2022) examined students’ perceptions and preferences in the use of written corrective feedback (WCF) in foreign language L2 writing classrooms in Saudi Arabia context. However, this study focused only on online learning environments. They examined the written corrective feedback strategies that students preferred in online writing classrooms not typical classrooms as this current study examined. Salami and Khadawardi (2022) examined students’ preferences through quantitative methods, yet the current study employed both quantitative and qualitative approaches. Rasool et al. (2024) studied perceptions and preferences of the written corrective feedback of students that they received in high school in their home countries. The current study examined different group level which are university students’ preferences. As in Salami and Khadawardi (2022), Rasool et al. (2024) study examined these preferences only quantitatively. This paper aims to address these gaps by focusing on students’ preferences and the underlying reasons for their choices regarding WCF using mixed-method approach.

Significance of the study

This study is conducted to investigate undergraduate EFL learners’ preferences for different types of written corrective feedback: direct, indirect, and metalinguistic, and it is hoped that the findings of the study would contribute to the existing body of knowledge. The significance of this current study lies in its potential to enhance the teaching and learning of English as a foreign language. The key points that highlighting its importance are the following.

First, it would help instructors, instructional coordinators, academic program developers in understanding learners’ preferences of written corrective feedback so to choose the best kind that suit the learners’ needs. Knowing and using the best kind of corrective feedback would improve learners’ motivation and engagement. Second, it will help to improve learning outcomes, when educators know the best corrective feedback, they will use it and this can improve learners’ writing skills, grammar, and overall language proficiency since the study provides insights into which types of feedback learners prefer: direct, indirect, or metalinguistic. Third, Findings could guide teachers in choosing and implementing feedback strategies that align with best practices in language education in Hail University. The research encourages a more learner-centered approach, fostering a supportive learning environment. Further, EFL learners’ preferences might differ based on cultural, educational, and linguistic backgrounds. The study’s focus on undergraduate learners provides context-specific insights that are particularly relevant for similar educational settings. It also adds to the existing body of knowledge on written corrective feedback and its impact on language acquisition. Lastly, the study involves learners’ preferences, so this acknowledges the importance of their opinion in the learning process, leading to more effective and personalized language learning experiences. To conclude, this study would include pedagogical and practical value for EFL educators, researchers, and learners by shedding light on how written corrective feedback can be optimized for better learning outcomes.

Literature review

Written corrective feedback

Truscott’s (1996) argument against corrective feedback in writing classes, where he stated that feedback is not only ineffective for L2 students but also harmful, prompted L2 researchers to conduct numerous studies examining the effectiveness of WCF in second-language contexts. Most studies have concluded that WCF is beneficial for students and helps them improve their linguistic skills, awareness, and accuracy (Bitchener, 2008; Bitchener and Knoch, 2009; Evans et al., 2011; Van Beuningen et al., 2012). These studies have found WCF to be effective; however, certain factors (e.g., learners’ proficiency levels) may impact its effectiveness. For instance, Bitchener and Knoch’s (2009) study on advanced and lower-intermediate students revealed that the suitability of feedback varies by proficiency level. For this reason, it is essential to ask students which type of feedback they prefer, as this helps teachers provide appropriate feedback and supports students in improving their writing, as suggested by Al-Hajiri and Al-Mahrooqi (2013).

In this context, we focus on students’ preferences, as previous research has primarily examined the effectiveness of WCF based on students’ performance, while fewer studies have explored their preferences. Another factor influencing the effectiveness of feedback is the type of errors identified by teachers. Errors can be categorized into form-related errors, such as mechanics and grammar, and content-related errors, including organization and coherence. For instance, Blair et al. (2013) found that students preferred to receive WCF on form-related errors. Therefore, teachers’ practices are important in the effectiveness of WCF, as understanding their students’ needs enables them to use the most suitable type of feedback.

Sheen et al. (2009) reported that many researchers question whether teachers can provide sufficient and reliable feedback. Most importantly, there is uncertainty about whether students are willing to receive and respond to feedback. Nevertheless, both teachers and students generally recognize the importance of WCF and its significant effects (Montgomery and Baker, 2007). Hyland (2011) stated that students believe that feedback enhances their motivation, improves their grades, and helps them identify their strengths and weaknesses. Similarly, Elfiyanto and Fukazawa (2021) concluded that WCF supports students’ learning, although some benefit more from peer feedback, while others benefit more from teacher feedback.

If students realize the effectiveness of feedback and understand its advantages, they are better positioned to identify which types are most beneficial, which are effective, and which may not be helpful at all. Their perceptions of corrective feedback assist teachers in selecting the type of feedback that aligns with students’ preferences and uncovering the reasons behind these choices. Rasool et al. (2024) examined learners’ perceptions and preferences of the written corrective feedback that they received in high school in their home countries. The study concluded that students had positive perceptions toward WCF in their EFL classes without focusing attention on studying the difference between direct, indirect and metalinguistics feedback. The current study examined different group level which are university students’ preferences focusing on three different types of feedback. As mentioned earlier, students may prefer specific types of feedback due to their proficiency levels, the nature of the errors they make, or other individual factors. This paper examines these preferences and the reasons and motivations that lead them to favor one type of feedback over another.

Implicit and explicit corrective feedback

Various studies have analyzed different types of feedback through different lenses, often focusing on learners’ proficiency levels. These studies typically aim to examine the effectiveness of feedback at specific proficiency levels without considering other factors, such as age or gender. In their quasi-experimental study, Mekala and Ponmani (2017) examined the effectiveness of direct corrective feedback on 116 low-proficiency college learners. The authors’ goal was to determine whether direct feedback affects students’ writing and to explore both learners’ and teachers’ preferences. It was concluded that direct feedback significantly improved students’ writing and that both teachers and learners favored this approach, believing it to be beneficial.

According to Mekala and Ponmani (2017), learners’ errors often stem from incomplete knowledge of the L2. Therefore, the authors argued that teachers should provide corrections directly, as students would not make these errors if they had the requisite knowledge. Conversely, merely indicating the location of errors can be challenging for low-proficiency learners, who may struggle to determine the correct answers. Purnawarman (2011) corroborated these findings, demonstrating that direct feedback is particularly effective for beginners and low-proficiency learners when addressing errors that are difficult to self-correct or mistakes in word choice and sentence structure—issues that are often beyond the ability of L2 learners to resolve without assistance. Salami and Khadawardi (2022) showed that learners found some written corrective feedback strategies to be more helpful than other kinds. Most students preferred electronic feedback while the second most favorable strategy was unfocused feedback.

Older studies also support the use of direct corrective feedback for beginners and lower-level learners, concluding that this practice enhances writing proficiency. For example, Leki (1990) and Ferris (1999) found that direct feedback improved students’ writing skills. The provision of this type of WCF for beginners has been a topic of research for decades. However, language researchers continue to study this issue across various contexts and study designs to produce robust and valid results. Notably, Ferris (1999) study was among the first to counter Truscott’s (1996) conclusion that feedback is harmful. Truscott (1996) controversially argued that “grammar correction has no place in writing courses and should be abandoned.” Ferris (1999) criticized this stance and provided evidence supporting the value of corrective feedback in improving learners’ writing. These older studies focused on the feedback itself rather than on its different types. This focus led most researchers to use only direct feedback in their studies, as they aimed to confirm the general effectiveness of feedback.

Twelve years after Truscott’s (1996) initial work, Truscott and Hsu (2008) conducted a new study examining 47 EFL learners in Taiwan to test the effectiveness of feedback. The authors aimed to evaluate two aspects: the effect of feedback on students’ ability to revise their writing and its impact on writing accuracy. It was found that while feedback influenced students’ revision accuracy, it did not improve their overall writing accuracy. The results showed that the error rates were almost identical between the group that received feedback and the group that did not. According to Truscott and Hsu (2008), feedback is effective in improving revision accuracy, which aligns with Chandler’s (2003) findings. Some researchers argue that if feedback enhances revision accuracy, it could—with adequate training—lead to improvements in writing accuracy.

Regarding the types of feedback, Chandler (2003) concluded that direct feedback is the most effective for improving students’ proficiency. This aligns with the results of Bitchener and Knoch (2009). In their six-month study on ESL students, Bitchener and Knoch (2009) used three treatment groups, each subjected to four tests, to examine the effectiveness of different types of WCF. The authors concluded that direct feedback was highly effective and suggested that there was no need to use other types of feedback, which could be more time-consuming.

As mentioned earlier, not all studies have focused on students’ proficiency levels. Research on the effectiveness of different kinds of feedback on student writing focuses on specific linguistic forms, such as the use of articles (Bitchener and Knoch, 2009; Ellis et al., 2008; Sheen, 2007). Others have explored learners’ and teachers’ preferences and perceptions of different types of feedback (Li and He, 2017; Al-Hajiri and Al-Mahrooqi, 2013; Lizzio and Wilson, 2008). Most studies focusing on grammatical forms, such as articles, found that students who received direct feedback outperformed those who received indirect feedback, as shown in Ellis et al. (2008) and Sheen (2007). Furthermore, feedback can sometimes be measured by examining multiple linguistic features rather than focusing on a single grammatical form, as demonstrated in Bitchener et al.’s (2005) study.

Sometimes, examining multiple grammatical features in a single study helps uncover the reasons behind the effectiveness of feedback rather than focusing solely on one feature. Bitchener et al. (2005) examined the effectiveness of different types of direct feedback on students’ writing by analyzing three grammatical features: the simple past, prepositions, and definite articles. They examined the performance of ESL learners in New Zealand, focusing specifically on these grammatical features, which were selected based on the most frequent errors observed in the study’s pretest. The study lasted 3 months and included four writing tasks, with learners completing one task every 2 weeks, except during week six.

The participants were divided into three groups: two groups received two different types of direct feedback, while the third group received no feedback. The results showed that the writing accuracy of students in the direct feedback groups improved in using two features—the simple past and definite articles—but there was no improvement in prepositions. The researchers concluded that direct feedback is effective but not for all grammatical features, which Ferris (1999) categorized as “treatable” and “untreatable” errors.

Writing in a second language without any grammatical mistakes is challenging; however, language researchers have explored whether certain errors can be corrected and reduced. These treatable errors, as described by Ferris (1999), can be addressed with appropriate feedback to help minimize or prevent them. According to the nativist theory of language acquisition, second language acquisition is similar to first language acquisition, with grammatical competence acquired automatically. However, there is a consensus in the field of second language acquisition that first and second language acquisition do not fully overlap (Doughty, 2003). This distinction has led researchers to determine how feedback can specifically help L2 learners improve their writing in ways that differ from L1 writing. Consequently, previous studies have focused on treatable and untreatable errors (e.g., Bitchener et al., 2005; Ferris, 2006) so that these studies could contribute to language learning.

The effectiveness of feedback types can be measured based on these two types of errors. For instance, Ferris (2006) found that teachers tend to use implicit corrective feedback for treatable errors, such as verb tense mistakes, whereas they use explicit corrective feedback for untreatable errors, such as sentence structure and word choice issues. Language researchers have also studied the effectiveness of implicit feedback when used independently. Some studies have concluded that learners who received indirect feedback outperformed those who received direct feedback (e.g., Amiri Dehnoo and Yousefvand, 2013; Ghandi and Maghsoudi, 2014).

Direct, indirect, and metalinguistic written corrective feedback

The effects of different types of corrective feedback have been studied in numerous research projects. There are various arguments, opinions, and findings regarding the most effective type of feedback for students. One of the earliest studies, conducted by Lalande (1982), showed that indirect corrective feedback is more effective for learning German. Learners who received indirect WCF outperformed those who received direct WCF. Similarly, Ghandi and Maghsoudi (2014) found that Iranian EFL students who received indirect feedback outperformed those in the direct feedback group. Ferris (2006) also observed long-term benefits for indirectly corrected errors. His longitudinal study indicated that indirect feedback is preferable to direct feedback for both teachers and students.

Conversely, Ellis et al. (2008), Sheen (2007), Van Beuningen et al. (2008), and Bitchener and Knoch (2009) concluded that direct feedback positively impacts learners’ performance. For example, Ellis et al. (2008) and Sheen (2007) both examined article use by providing direct feedback to experimental groups, finding that learners who received direct feedback improved their results. In contrast, Ferris and Roberts (2001) found no significant differences between students who received direct feedback and those who received indirect feedback.

Bitchener and Knoch (2009) and Bitchener (2008) compared direct and metalinguistic corrective feedback, concluding that, unlike other groups, students who received direct WCF demonstrated greater accuracy. According to Ellis et al. (2008), metalinguistic WCF can help students understand their errors.

Based on the studies mentioned above, each type of feedback has its own benefits and effects. Direct WCF is perfect for helping students learn and address complex linguistic errors, as shown by Van Beuningen et al. (2012) and Hosseiny (2014). In contrast, indirect WCF helps students identify and understand their errors, leading to long-term improvement, as suggested by Hosseiny (2014) and Bitchener (2008). Similarly, metalinguistic WCF, as indicated by Ellis et al. (2008), benefits the teaching process by enhancing students’ cognitive abilities to understand and correct their errors.

Rasool et al. (2023) concluded that students dislike ambiguous feedback that confuses them about their errors. Their study showed that metalinguistic explanations and direct WCF facilitated writing proficiency and language knowledge. Zohra and Fatiha (2022) found that learners prefer their writing to be corrected with unfocused, direct feedback, whereas teachers tend to use indirect, focused feedback. Bal (2022) concluded that learners value the importance and usefulness of the feedback they receive. The authors reported that learners wanted all their mistakes in their written work to be corrected, regardless of how they felt. Reynolds and Zhang (2023) concluded that learners preferred WCF related to writing structure over content and mechanics. Students also preferred direct over indirect feedback for both writing content and structure.

Corrective feedback in students’ written work: Ellis’s (2009) typology

Ellis (2009) suggested that there are various methods teachers can use to correct students’ written work. He presented a typology of options, along with descriptions of each type, based on empirical studies in WCF and teachers’ handbooks. The following table, adapted from Ellis (2009), outlines the different types of implicit and explicit corrective feedback used in studies on WCF (Table 1).

Table 1

| Type of CF | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Direct CF | The teacher provides the student with the correct form. |

| 2. Indirect CF | The teacher indicates that an error exists but does not provide the correction. |

| Indication + location of the error | This takes the form of underlining and using cursors to show omissions in the student’s text. |

| Indication only | This involves marking the margin to indicate that an error or errors have occurred in a line of text. |

| 3. Metalinguistic CF | The teacher provides a metalinguistic clue about the nature of the error. |

| Use of error code | The teacher writes codes in the margin (e.g., ww = wrong word; art = article). |

| Brief grammatical descriptions | The teacher numbers errors in the text and writes a grammatical description for each numbered error at the bottom of the text. |

| 4. Focus of feedback | This concerns whether the teacher attempts to correct all (or most) of the students’ errors or selects one or two specific types of errors to correct. This distinction applies to each of the above options. |

| Unfocused CF | Unfocused CF is extensive. |

| Focused CF | Focused CF is intensive. |

| 5. Electronic feedback | The teacher indicates an error and provides a hyperlink to a concordance file that provides examples of correct usage. |

| 6. Reformulation | A native speaker reworks the student’s entire text to make the language as native-like as possible while preserving the original content. |

Types of teacher written corrective feedback (Ellis, 2009, p. 98).

Written corrective feedback and teaching

Feedback is an important element in the teaching process. Many researchers have studied feedback in teaching and concluded that errors are an integral part of the learning process. Students benefit from making errors, and teachers should correct these errors through corrective feedback. Bitchener and Ferris (2012) argued that learning occurs when students receive corrective feedback. Therefore, it is important for teachers to tailor their feedback styles to their students.

As corrective feedback helps students understand and correct their errors, thereby improving their skills, it becomes necessary to determine which type of corrective feedback they prefer. Using feedback that aligns with students’ preferences can help them improve various skills and facilitate L2 acquisition, as suggested by Bitchener and Ferris (2012). Corrective feedback is most effective when students prefer it, as this leads to a more effective learning process.

In the Arabic context, particularly in Oman, Al-Hajiri and Al-Mahrooqi (2013) found that teachers should adjust their feedback practices to meet students’ needs. Their study suggested that teachers must provide feedback that is comprehensible and preferred by students, as it plays a vital role in the learning process. Therefore, students’ perceptions of the type of WCF are important. Written corrective feedback has helped students improve their writing proficiency, and studies such as those by Lizzio and Wilson (2008) and Blair et al. (2013) found that learners often preferred specific types of WCF for their assignments, essays, and class activities to achieve their intended goals.

Teachers should understand students’ needs and use suitable feedback. Major (1988) stated that teachers’ understanding of students’ needs leads to successful corrections. Guénette (2007) reached similar conclusions, showing that knowing students’ preferences enables teachers to provide more effective feedback. This research aims to examine whether Saudi students receive their preferred type of feedback by comparing their preferences with those of their teachers. When teachers align their feedback practices with students’ preferences, they can create a successful teaching process and provide comprehensible input.

Methods

Research questions

Do undergraduate EFL students prefer direct, indirect, or metalinguistic WCF?

Why do undergraduate EFL students prefer direct, indirect, or metalinguistic WCF?

Research design

A mixed-methods approach was used in this study to examine undergraduate EFL learners’ preferences for different types of written corrective feedback: direct, indirect, and metalinguistic. By using a mixed-methods approach, the researcher tried to provide a complete, clear and comprehensive understanding of the research problem which is examining learners’ preferences for different types of feedback by using both deductive and inductive reasoning. A questionnaire was used to investigate learners’ preferences, along with a follow-up semi-structured interview.

Quantitative data gives a general result and a comprehensive explanation and of the research questions. While the rationale and reasons for all the results and findings qualitative data describes (Creswell and Clark, 2018). Guest and Fleming (2014) stated that combining more than one type of data source gives a more detailed and comprehensive understanding of a research problem than a single approach. Riazi and Farsani (2024) showed that mixed-methods research in the field of applied linguistics intends to benefit from the affordances of quantitative and qualitative methodologies in one single study. They also stated that together quantitative and qualitative analysis methods used to address the adversarial incompatibility of quantitative and qualitative approaches and also to help researchers produce more comprehensive inferences.

Participants

This study involved 320 male and female Saudi undergraduate students from the University of Hail. These students were in their first year across various colleges, including sciences, business administration, engineering, medicine, nursing, arts, and education. The participants were enrolled in a required English course during their first semester, which provided the context for this study. A pilot study was conducted with a small number of participants to ensure the validity of the questionnaire and to identify any difficulties in understanding the items or completing the questionnaire.

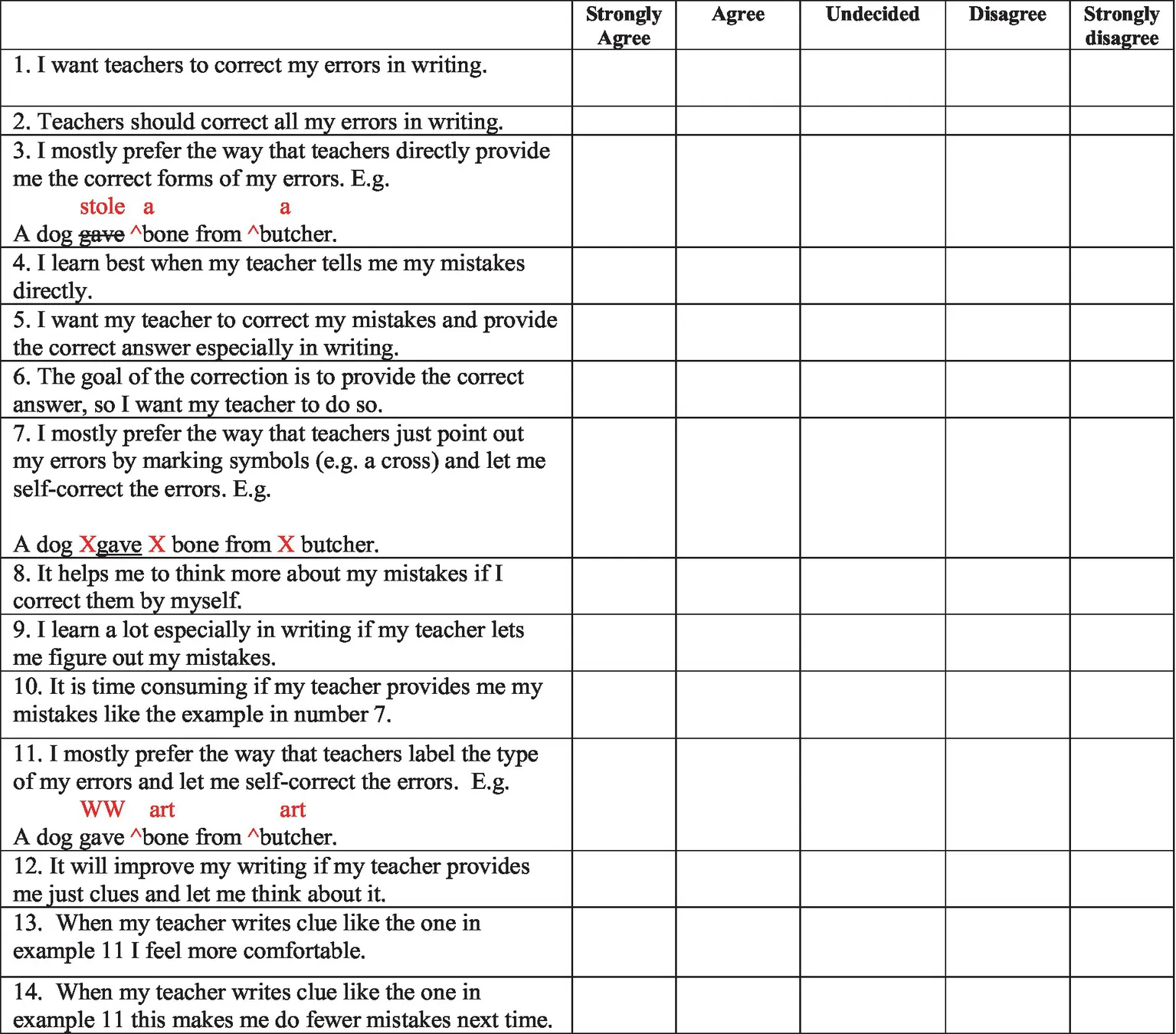

Instruments

A 5-point Likert scale questionnaire was used for data collection from students (see Appendix A). The questionnaire was adapted from Li and He (2017), with some items added and modified to align with the sample and research questions. It consisted of 14 items. The first two items examined students’ willingness to receive corrective feedback. The remaining 12 items were divided into three sections based on the types of WCF: direct, indirect, and metalinguistic. For each type, a direct question with an example was provided to ask students about their preferences, followed by more detailed items.

The second instrument was semi-structured interviews with students. A total of 16 voluntary participants were interviewed by the researcher. The purpose of the interviews was to validate the questionnaire results and gather additional reflections. The interview questions were validated by the same professors who reviewed the questionnaire. During the interviews, the students were asked about their thoughts on different types of WCF, their reasons for preferring certain types, and their teachers’ practices in providing written feedback for various types of writing, such as class tasks, exam essays, and others. The students were encouraged to speak freely on any points raised by the researcher.

Procedure

Data collection

The questionnaire was created and distributed online. The researcher visited the students in their classes to inform them about the study and encourage participation, emphasizing that it was completely optional. Students were also invited to volunteer for the interviews. The semi-structured interviews were conducted face-to-face in the researcher’s office. The participants were encouraged to express their thoughts openly and provide suggestions to help make more accurate inferences and implications. The interviews were recorded, thematically categorized, and manually analyzed.

Data analysis

The data obtained from the questionnaires were analyzed quantitatively using SPSS. The researcher performed numerical coding of the items and participants. Each scale was assigned numerical values: strongly agree = 1, agree = 2, undecided = 3, disagree = 4, and strongly disagree = 5. Means, percentages, standard deviations, and other relevant statistics were calculated using SPSS and included in the findings and discussion.

For qualitative analysis, the interview recordings were transcribed, coded, and categorized to facilitate discussion of the results. The researcher used thematic analysis to analyze the qualitative data, i.e., the semi-structured interview data by using careful reading and interpretation of the data gathered from the interviews. The researcher used theme analysis to understand students experiences directly by categorizing and examining their recurring ideas and concepts. Through this process, the researcher utilized the six-phase approach to thematic analysis that Braun and Clarke (2012) outlined and illustrated as follows:

outlined and illustrated using.

worked examples through.

Phase 1: Familiarizing yourself with the data.

Phase 2: Generating initial codes.

Phase 3: Searching for themes.

Phase 4: Reviewing potential themes.

Phase 5: Defining and naming themes.

Phase 6: Producing the report.

The interview findings were used to validate the questionnaire results, enrich the discussion, and provide additional insights that helped explore new ideas for improving WCF and, ultimately, enhancing language learning and acquisition.

Results

The results showed that most learners prefer direct written corrective feedback since it helped them to improve their writing skill and it is easier to understand. Learners in this current study are not sure about metalinguistics written corrective feedback in the quantitative result, however, the qualitative results showed that they preferred it since it is interesting, memorable and enjoyable learning experience and it motivated them for learning. The findings also showed that learners do not prefer indirect written corrective feedback. The following sections presents quantitative and qualitative results.

Quantitative results

The questionnaire was designed to elicit students’ preferences and beliefs regarding different types of WCF: direct, indirect, and metalinguistic. The participants were first asked about their general preferences for receiving corrections on their writing errors. Subsequently, they were specifically asked about the three different types of feedback. Examples of the questions included: “I mostly prefer the way that teachers directly provide me the correct forms of my errors,” “I mostly prefer the way that teachers just point out my errors by marking symbols,” “I learn a lot, especially in writing, if my teacher lets me figure out my mistakes,” and “I mostly prefer the way that teachers label the types of my errors and let me self-correct the errors.”

The questionnaire was divided into three sections corresponding to the three types of WCF: direct, indirect, and metalinguistic. A 5-point Likert scale was used, with weights assigned as follows: 5 (strongly agree), 4 (agree), 3 (undecided), 2 (disagree), and 1 (strongly disagree). Initially, the participants were asked about their general attitudes toward feedback in language learning to test their acceptance of feedback. Table 2 shows the frequencies and percentages of the students’ responses regarding their general acceptance of corrective feedback.

Table 2

| Would you like teachers to correct all your language mistakes? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | |

| Yes, to a great extent | 263 | 82.18 |

| Yes, somewhat | 43 | 13.43 |

| No, very little | 12 | 3.75 |

| No, not at all | 2 | 0.62 |

| Total | 320 | 100.0 |

Participants’ general perspectives about language feedback.

The participants were then asked about their views on feedback in writing. To provide a clearer understanding of their responses, the researcher combined the answers “strongly agree” and “agree” into a single category labeled “agreement” and “strongly disagree” and “disagree” into a category labeled “disagreement.”

As shown in Table 3, the majority of participants (97%) confirmed the importance of WCF and expressed that they wanted teachers to correct their writing errors. Approximately 1.9% disagreed, and 0.6% were undecided. Approximately 94% of the participants agreed that receiving feedback was essential.

Table 3

| Item | Strongly agree (%) | Agree (%) | Undecided (%) | Disagree (%) | Strongly disagree (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I want teachers to correct my errors in writing. | 257 (80.3) | 55 (17.1) | 2 (0.6) | 6 (1.87) | 0 |

| Teachers should correct all my errors in writing. | 203 (63.4) | 101 (31.5) | 5 (1.5) | 10 (3.1) | 1 (0.31) |

Participants’ general opinions about written corrective feedback.

As previously mentioned, to gain a deeper understanding of students’ preferences regarding the three types of feedback, we asked them to complete a questionnaire with three sections. The first section addressed direct feedback. Most participants expressed positive attitudes toward WCF, with 77% reporting that they preferred teachers to directly provide them with the correct forms of their errors, while about 21% disagreed, as shown in Table 4. The table also indicates that the participants believed they learned better when corrected directly, with approximately 74% agreeing and 24% disagreeing. Additionally, 75% of the participants agreed that they needed direct corrective feedback, especially in writing. Given that most participants held positive attitudes toward direct corrective feedback, it is unsurprising that the majority (93.7%) agreed that the goal of correction is to provide the correct answer and that they wanted teachers to do so.

Table 4

| Item | Strongly agree (%) | Agree (%) | Undecided (%) | Disagree (%) | Strongly disagree (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I mostly prefer the way that teachers directly provide me the correct forms of my errors. | 189 (59.0) | 58 (18.1) | 3 (0.9) | 68 (21.25) | 2 (0.6) |

| I learn best when my teacher tells me my mistakes directly. | 177 (55.3) | 61 (19.0) | 5 (1.5) | 71 (22.1) | 6 (1.8) |

| I want my teacher to correct my mistakes and provide the correct answer, especially in writing. | 162 (50.6) | 78 (24.3) | 11 (3.4) | 59 (18.4) | 10 (3.1) |

| The goal of the correction is to provide the correct answer, so I want my teacher to do so. | 201 (62.8) | 99 (30.9) | 16 (5) | 4 (1.25) | 0 |

Participants’ preferences for direct written corrective feedback.

Table 5 provides descriptive statistics for the four items examining the participants’ opinions about indirect feedback. About 74% of the participants disagreed with the idea that teachers should only point out errors using symbols, which refers to indirect feedback, whereas around 14% agreed. Furthermore, approximately 60% of the participants disagreed with the notion that correcting errors independently helps them think more about their mistakes. As shown in Table 5, more than half of the participants (66%) disagreed with the idea of being left to figure out their mistakes, and 84% agreed that it was time-consuming for teachers to provide indirect feedback.

Table 5

| Item | Strongly agree (%) | Agree (%) | Undecided (%) | Disagree (%) | Strongly disagree (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I mostly prefer that teachers just point out my errors using symbols. | 30 (9.3) | 18 (5.6) | 33 (10.3) | 182 (56.8) | 57 (17.8) |

| It helps me to think more about my mistakes if I correct them myself. | 54 (16.8) | 33 (10.3) | 38 (11.8) | 105 (32.8) | 90 (28.1) |

| I learn a lot, especially in writing, if my teacher lets me figure out my mistakes. | 72 (22.5) | 20 (6.2) | 12 (3.7) | 203 (63.4) | 13 (4) |

| It is time-consuming if my teacher corrects my mistakes like in example number 7. | 199 (62.1) | 73 (22.8) | 16 (5) | 14 (4.3) | 18 (5.6) |

Participants’ preferences for indirect written corrective feedback.

As shown in Table 6, there is no clear difference between the percentage of participants who agreed and those who disagreed about metalinguistic WCF, with agreement at 39% and disagreement at 47%. Approximately 44% of participants agreed that providing metalinguistic WCF could improve their writing, while about 45% disagreed, and 9.6% were undecided. About 41% of the participants reported that providing clues as a form of metalinguistic WCF made them feel more comfortable, whereas 53% disagreed. Additionally, 47% of the participants agreed that metalinguistic WCF helps reduce mistakes, while 38% disagreed.

Table 6

| Item | Strongly agree (%) | Agree (%) | Undecided (%) | Disagree (%) | Strongly disagree (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I mostly prefer that teachers label the types of my errors and let me self-correct them. | 17 (5.3) | 108 (33.7) | 42 (13.1) | 96 (30) | 57 (17.8) |

| It will improve my writing if my teacher provides me just clues and lets me think about my mistakes. | 43 (13.4) | 99 (30.9) | 31 (9.6) | 101 (31.5) | 46 (14.3) |

| When my teacher writes a clue, such as the one in example 11, I feel more comfortable. | 76 (23.7) | 56 (17.5) | 15 (4.6) | 99 (30.9) | 74 (23.1) |

| When my teacher writes a clue, such as the one in example 11, it helps me make fewer mistakes next time. | 33 (10.3) | 119 (37.1) | 45 (14) | 99 (30.9) | 24 (7.5) |

Participants’ preferences for metalinguistic written corrective feedback.

Qualitative results

This section presents the findings of the semi-structured interviews. The data gathered during the interviews were transcribed and coded using thematic analysis. Fifteen students volunteered to participate in individual interviews. After transcribing and coding the data and considering the research questions, the researcher identified three main themes, each with two categories:

1 Direct corrective written feedback

a Improving learners’ writing skills

b Easier to understand

2 Metalinguistic corrective written feedback

a Interesting, memorable, and enjoyable learning experience

b Motivating

3 Indirect corrective written feedback

a Unclear

b Time-consuming

The participants were asked about their preferences and thoughts regarding the three types of WCF. Some argued that the best type of feedback is direct feedback, while others preferred metalinguistic feedback. The participants expressed uncertainty about indirect WCF. Consequently, they could be divided into three main groups based on their responses: those with a positive attitude toward direct WCF, those with a positive attitude toward metalinguistic WCF, and those unsure about indirect WCF. The group with a positive attitude toward direct WCF argued that they preferred it because it was clear and straightforward. They mentioned that it was easy to understand and apply the corrections. The participants explained that direct WCF helps them improve their writing because it provides the correct answer without requiring additional time to think or find it. One participant stated that in writing, “we need direct correction; in speaking, maybe not, but in writing, I really need my teacher to show me the correct answer.” The participants also noted that direct feedback improved their writing skills, including word choice, grammar, and spelling. One participant said, “In writing paragraphs, the teacher corrects me directly and improves my grammar mistakes.” Another participant remarked, “I believe I need my teacher to correct me as directly as possible. I remember my teacher suggested better words for my essay… it helped me a lot.” Another participant explicitly stated, “Teachers should clearly correct using red pens. This is especially helpful in spelling and correcting the main ideas in essays.” They emphasized the importance of direct WCF for making corrections easier to understand, with one participant commenting, “I guess that it is easy for me to be corrected directly. Why should I need to think in order to find the answer?”

The second group, which had a positive attitude toward metalinguistic WCF, mentioned that correcting their errors using linguistic clues was very engaging and provided them with a meaningful learning experience by allowing them to guess the corrections based on the teacher’s clues. One participant shared, “I really like one of my teachers from when I studied at a center. She provided clues for me, and I tried to correct them, like marking ‘Past Tense’ for a mistake in the verb past tense form. I thought about it, searched, and corrected it. I believe this will keep it in my mind, and I will not forget it.” Another participant commented, “I really like it… I did not know about this before, but when you explain it, I guess it will help me understand my mistakes and memorize them.”

The participants also expressed that receiving clues motivated them to learn. One learner mentioned, “I like when one of my teachers gave me hints when she corrected my writing. I felt more comfortable, and this encouraged me to learn more.” Another stated, “You should tell teachers to use this method—it is great… I feel this makes me love writing.”

Some participants argued that indirect corrective feedback is time-consuming and does not provide them with the necessary information, thereby negatively affecting the learning process. One participant stated, “I do not know why the teacher did not tell me the correct answer… why should I have to ask or search? It would save time if she told me, and it would make me learn quickly and easily.” Another participant argued that indirect WCF could lead to an insufficient learning process, saying, “I remember one of my teachers who corrected this way… this did not benefit me at all because I could not know the correct answer, and I did not know how to find it.” The participants also mentioned that indirect feedback is unclear to them, and they often do not understand their errors or how to correct them. One participant stated, “Oh… my teacher wrote me an error sign without telling me why, and to this day, I do not know the correct answer.” Another said, “It is hard to receive a comment just saying that something is wrong without a clear correction… as a student, who else can tell me? I tried to search, but I think my answer is wrong, too.”

Discussion

This mixed-methods study investigated students’ preferences for three types of WCF—direct, indirect, and metalinguistic—and the reasons behind these preferences. The previous section presented the quantitative results from a questionnaire and the qualitative results from semi-structured interviews.

The first research question focused on the type of feedback preferred by undergraduate EFL students. To answer this question, the participants’ questionnaire responses were analyzed and supported by insights from the interviews. Overall, the students appeared to have a positive attitude toward WCF. As shown in Table 3, 97% of the participants confirmed the importance of WCF and expressed a desire for teachers to correct their writing errors. As suggested by Elfiyanto and Fukazawa (2021), WCF is crucial for students. Further, learners in Salami and Khadawardi (2022) found that WCF helpful tool to improve their writing.

The results revealed that most participants (77%) preferred that teachers directly provided them with the correct forms of their errors, while about 21% disagreed. Additionally, 74% of participants believed they learned better when corrected directly, compared to 24% who disagreed. Approximately 75% of the participants agreed that they needed direct corrective feedback, especially in writing. Given these findings, it is unsurprising that most of the participants (93.7%) agreed that the goal of correction is to provide the correct answer, and they expressed a preference for teachers to correct them directly. These results align with those of Zohra and Fatiha (2022), who found that learners preferred that their writing be corrected using unfocused, direct feedback. Learners found it clearer and more effective for their learning process to be corrected directly. Whether the error pertained to content, grammar, or structure, approximately 74% of the participants agreed with the statement, “I want my teacher to correct my mistakes and provide the correct answer, especially in writing.” As concluded by Reynolds and Zhang (2023), learners preferred direct feedback over indirect feedback for both writing content and structure. Participants who favored direct WCF argued that they preferred it because it was clear and straightforward. They mentioned that it was easy to understand and implement the corrections. The participants also stated that direct WCF helps them improve their writing because it provides the correct answer without requiring additional time to think and search for it. Ellis et al. (2008), Sheen (2007), Van Beuningen et al. (2008), and Bitchener and Knoch (2009) similarly concluded that direct feedback has a positive effect on learners’ performance. Rasool et al. (2024) results showed that most students have positive attitudes regarding WCF perceptions and the study concluded that the most preferred types are direct and unfocused WCF.

The findings of the current study revealed that most participants did not prefer indirect WCF. They disagreed with the idea that teachers should simply point out errors using symbols. Furthermore, around 60% of the participants disagreed that correcting their mistakes independently helped them reflect on their errors. More than half of the participants (66%) disagreed with the idea of being left to figure out their mistakes, and 84% agreed that indirect feedback is time-consuming. As Rasool et al. (2023) concluded, learners dislike ambiguous feedback that confuses them about their errors. Their study found that students preferred metalinguistic explanations and direct WCF, which facilitated both writing proficiency and language knowledge. In the current study, the participants argued that indirect corrective feedback is time-consuming and does not provide the necessary information, thereby negatively affecting the learning process.

The quantitative results regarding metalinguistic WCF were mixed, with 39% of the participants expressing agreement and 47% expressing disagreement. Approximately 44% agreed that providing metalinguistic WCF could improve their writing, while about 45% disagreed, and 9.6% were undecided. About 41% of the participants reported that being provided clues as a form of metalinguistic WCF made them feel more comfortable, whereas 53% disagreed. Additionally, 47% of the participants agreed that metalinguistic WCF helped reduce mistakes, while 38% disagreed. However, the qualitative findings showed that all participants expressed a preference for metalinguistic WCF. The participants stated that receiving clues motivated them to learn and made feedback more engaging and interesting. The qualitative findings show that the students preferred direct and metalinguistic WCF over indirect feedback. The group with a positive attitude toward direct WCF argued that they preferred it because it was clear and straightforward. They mentioned that it was easy to understand and facilitated the implementation of the corrections. The participants stated that direct WCF helped them improve their writing because it provided the correct answer without requiring additional time to think or search for it. Bitchener and Knoch (2009) and Bitchener (2008) examined the differences between direct and metalinguistic corrective feedback and concluded that students who received direct WCF showed greater accuracy than the other groups. The participants in the current study also stated that direct feedback helped them improve their writing. As noted by Van Beuningen et al. (2012) and Hosseiny (2014), direct WCF is particularly effective in helping students learn and understand complex linguistic errors.

Future implication

The results of this study about undergraduate EFL learners’ preferences for three different types of written corrective feedback: direct, indirect, and metalinguistic can guide L2 instructors in developing effective feedback strategies and help instructional and academic program coordinators in choosing the effective feedback. For example, students’ support for WCF reflects their preference for delegating the responsibility of error correction to teachers. This help instructors and developers to think of the best kind of feedback to help in equipping learners with strategies that could enhance the accuracy of their own writing which leads to improving their general language proficiency. Further research is necessary to identify the best approaches for addressing the differences between teachers’ practices and students’ expectations.

Pedagogically, it is essential for teachers to clearly explain the purpose of WCF and ensure that students understand and accept their role in the error correction process and providing them the suitable feedback. At the same time, teachers need to consider students’ attitudes and beliefs, as mismatches between their perspectives can diminish the effectiveness of feedback. Therefore, teachers should actively engage students in discussions about corrective feedback practices, adjust WCF types and strategies to promote language learning, and take students’ preferences into account to motivate and empower them in the language learning process.

Conclusion

This study was conducted to examine undergraduate students’ preferences for three different types of WCF: direct, indirect, and metalinguistic. The participants were undergraduate students from various colleges at Hail University. A mixed-methods approach was employed, with data collected through a questionnaire and semi-structured interviews. We sought to answer two primary research questions: the first examined students’ preferences among the three types of WCF, and the second explored the reasons underlying their preferences.

The results indicated that students clearly preferred direct WCF because it helped them improve their writing skills and was easy to understand. The quantitative results suggested that the students appeared uncertain about metalinguistic WCF. However, the qualitative results revealed strong support and preference for metalinguistic feedback, as the participants found it a motivating, interesting, enjoyable, and memorable learning experience. Regarding indirect WCF, the participants did not prefer it, as shown in both the quantitative and qualitative findings, describing it as unclear and time-consuming. As Rasool et al. (2023) concluded, learners dislike ambiguous feedback that confuses them about their errors, preferring metalinguistic explanations and direct WCF, which facilitate writing proficiency and language knowledge.

Limitations of the current study is that it did not examine the participants’ overall language proficiency. Learners’ proficiency levels might provide additional insights and enrich the findings, offering further understanding of the reasons behind their preferences for one type of feedback over another. Further, a larger sample size could provide a basis for more practical generalizations of the findings. Future research could also explore the relationship between students’ preferences for WCF and their language proficiency. For a more detailed understanding of learners’ preferences of WCF, future studies could include observations and data analysis of students’ assignments and examining actual students’ performance and its relation to the preferred kind of feedback Additionally, further studies are needed to identify the potential effects of new technology on language learners’ preferences regarding WCF.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Al-HajiriF.Al-MahrooqiR. (2013). Student perceptions and preferences concerning instructors’ corrective feedback. Asian EFL J.70, 28–53.

2

Amiri DehnooM.YousefvandG. (2013). The effect of direct feedback on students’ spelling errors. ELT Voices-India3, 23–26.

3

BalN. G. (2022). EFL students’ perceptions of the effectiveness of corrective feedback on their written tasks. Hacettepe Univ. J. Educ.37, 1–14. doi: 10.16986/HUJE.2021068382

4

BitchenerJ. (2008). Evidence in support of written corrective feedback. J. Second. Lang. Writ.17, 102–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2007.11.004

5

BitchenerJ.FerrisD. (2012). Written corrective feedback in second language acquisition and writing. New York: Routledge.

6

BitchenerJ.KnochU. (2009). The relative effectiveness of different types of direct written corrective feedback. System37, 322–329. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2008.12.006

7

BitchenerJ.YoungS.CameronD. (2005). The effect of different types of corrective feedback on ESL student writing. J. Second Lang. Writ.14, 191–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2005.08.001

8

BlairA.CurtisS.GoodwinM.ShieldsS. (2013). What feedback do students want?Politics33, 66–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9256.2012.01446.x

9

BraunV.ClarkeV. (2012). “Thematic analysis” in APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2. Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). eds. CooperH.CamicP. M.LongD. L.PanterA. T.RindskopfD.SherK. J. (Washington DC: American Psychological Association).

10

ChandlerJ. (2003). The efficacy of various kinds of error feedback for improvement in the accuracy and fluency of L2 student writing. J. Second. Lang. Writ.12, 267–296. doi: 10.1016/S1060-3743(03)00038-9

11

CreswellJ. W.ClarkV. L. P. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

12

DoughtyC. J. (2003). “Instructed SLA: constraints, compensation, and enhancement” in Handbook of second language acquisition. eds. DoughtyC. J.LongM. H. (Oxford: Blackwell).

13

ElfiyantoS.FukazawaS. (2021). Three written corrective feedback sources in improving Indonesian and Japanese students’ writing achievement. Int. J. Instr.14, 433–450. doi: 10.29333/iji.2021.14325a

14

EllisR. (2009). A typology of written corrective feedback types. ELT J.63, 97–107. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccn023

15

EllisR.SheenY.MurakamiM.TakashimaH. (2008). The effects of focused and unfocused written corrective feedback in an English as a foreign language context. System36, 353–371. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2008.02.001

16

EvansN. W.HartshornK.Strong-KrauseD. (2011). The efficacy of dynamic written corrective feedback for university-matriculated ESL learners. J. Second. Lang. Writ.39, 229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2011.04.012

17

FerrisD. (1999). The case for grammar correction in L2 writing classes: a response to Truscott (1996). J. Second. Lang. Writ.8, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/S1060-3743(99)80110-6

18

FerrisD. R. (2006). “Does error feedback help student writers? New evidence on the short-and long-term effects of written error correction” in Feedback in second language writing: Contexts and issues. eds. HylandK.HylandF. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University), 81–104.

19

FerrisD.RobertsB. (2001). Error feedback in L2 writing classes: how explicit does it need to be?J. Second. Lang. Writ.10, 161–184. doi: 10.1016/S1060-3743(01)00039-X

20

GhandiM.MaghsoudiM. (2014). The effect of direct and indirect corrective feedback on Iranian EFL learners’ spelling errors. Engl. Lang. Teach.7, 53–61. doi: 10.5539/elt.v7n8p53

21

GuénetteD. (2007). Is feedback pedagogically correct? Research design issues in studies of feedback on writing. J. Second. Lang. Writ.16, 40–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2007.01.001

22

GuestG.FlemingP. J. (2014). “Mixed methods research” in Public Health Research methods. eds. GuestG.NameyE. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage).

23

HosseinyM. (2014). The role of direct and indirect written corrective feedback in improving Iranian EFL students’ writing skill. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci.98, 668–674. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.466

24

HylandF. (2011). “The language learning potential of form-focused feedback on writing: students’ and teachers’ perceptions” in Learning to write and writing to learn in an additional language. ed. ManchónR. M. (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 159–179.

25

LalandeJ. F. (1982). Reducing composition errors: an experiment. Mod. Lang. J.66, 140–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1982.tb06973.x

26

LekiI. (1990). “Coaching from the margins: issues in written response” in Second language writing: Research insights for the classroom. ed. KrollB. F. (New York: Cambridge University Press), 57–68.

27

LiH.HeQ. (2017). Chinese secondary EFL learners’ and teachers’ preferences for types of written corrective feedback. Engl. Lang. Teach.10, 63–73. doi: 10.5539/elt.v10n3p63

28

LizzioA.WilsonK. (2008). Feedback on assessment: students’ perceptions of quality and effectiveness. Assess. Eval. High. Educ.33, 263–275. doi: 10.1080/02602930701292548

29

MajorR. C. (1988). Balancing form and function. Int. Rev. Appl. Linguist. Lang. Teach.26, 81–100. doi: 10.1515/iral.1988.26.2.81

30

MekalaS.PonmaniM. (2017). The impact of direct written corrective feedback on low proficiency ESL learners’ writing ability. IUP J. Soft Skills11, 23–54.

31

MontgomeryJ.BakerW. (2007). Teacher-written feedback: students perceptions, teachers self-assessment, and actual teacher performance. J. Second. Lang. Writ.16, 82–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2007.04.002

32

PurnawarmanP. (2011). Impacts of different types of teacher’s corrective feedback in reducing grammatical errors on ESL/EFL students’ writing [doctoral dissertation, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University]. VTechWorks. Available at: https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/bitstream/handle/10919/30067/Purnawarman_P_Dissertation_2011.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (Accessed January 31, 2025).

33

RasoolU.MahmoodR.AslamM. Z.BarzaniS. H. H.QianJ. (2023). Perceptions and preferences of senior high school students about written corrective feedback in Pakistan. SAGE Open13. doi: 10.1177/21582440231187612

34

RasoolU.QianJ.AslamM. Z. (2024). Understanding the significance of EFL students’ perceptions and preferences of written corrective feedback. SAGE Open14. doi: 10.1177/21582440241256562

35

ReynoldsB. L.ZhangX. (2023). Medical school students’ preferences for and perceptions of teacher written corrective feedback on English as a second language academic writing: an intrinsic case study. Behav. Sci.13:13. doi: 10.3390/bs13010013

36

RiaziA. M.FarsaniM. A. (2024). Mixed-methods research in applied linguistics: charting the progress through the second decade of the twenty-first century. Lang. Teach.57, 143–182. doi: 10.1017/S0261444823000332

37

SalamiF. A.KhadawardiH. A. (2022). Written corrective feedback in online writing classrooms: EFL students’ perceptions and preferences. (2022). Int. J. English Lang. Teach.10, 12–35. doi: 10.37745/ijelt.13/vol10no1pp.12-35

38

SheenY. (2007). The effect of focused written corrective feedback and language aptitude on ESL learners’ acquisition of articles. TESOL Q.41, 255–283. doi: 10.1002/j.1545-7249.2007.tb00059.x

39

SheenY.WrightD.MoldawaA. (2009). Differential effects of focused and unfocused written correction on the accurate use of grammatical forms by adult ESL learners. J. Second. Lang. Writ.37, 556–569. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2009.09.002

40

TruscottJ. (1996). The case against grammar correction in L2 writing classes. Lang. Learn.46, 327–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1996.tb01238.x

41

TruscottJ.HsuA. Y.-P. (2008). Error correction, revision and learning. J. Second. Lang. Writ.17, 292–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2008.05.003

42

Van BeuningenG.De JongH.KuikenF. (2008). The effect of direct and indirect corrective feedback on L2 learners’ written accuracy. ITL Int. J. Appl. Linguist.156, 279–296. doi: 10.2143/ITL.156.0.2034439

43

Van BeuningenG.De JongN.KuikenF. (2012). Evidence on the effectiveness of comprehensive error correction in second language writing. Lang. Learn.62, 1–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9922.2011.00674.x

44

ZohraR. F.FatihaH. (2022). Exploring learners’ and teachers’ preferences regarding written corrective feedback types in improving learners’ writing skill. Arab World English J.13, 117–128. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol13no1.8

Appendix A

Questionnaire

College: sciences college—business administration college—engineering college—medicine college—nursing college—arts college—education college.

Gender: female–male.

Would you like that teachers correct all your mistakes in language?

Yes, to a great extent Yes, somewhat No, very little No, not at all.

|

Summary

Keywords

written corrective feedback, language learning, learners’ preferences, feedback, foreign language learning

Citation

Almohawes M (2025) Undergraduate EFL learners’ preferences for three different types of written corrective feedback. Front. Educ. 10:1532729. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1532729

Received

22 November 2024

Accepted

28 January 2025

Published

10 February 2025

Volume

10 - 2025

Edited by

Muhammad Zammad Aslam, University of Science Malaysia (USM), Malaysia

Reviewed by

Ushba Rasool, Zhengzhou University, China

Sami Barzani, Tishk International University (TIU), Iraq

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Almohawes.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Monera Almohawes, m.almohawes@uoh.edu.sa

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.