94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Educ., 27 February 2025

Sec. Mental Health and Wellbeing in Education

Volume 10 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1522997

Background: Teachers are regarded as attachment-like figures, with positive and supportive teacher-student relationships (TSRs) being linked to improved academic performance and outcomes, while negative TSRs are associated with lower academic results. This systematic review aims to map the relational dimensions of the TSR and its impact on academic (dis)engagement, (under)achievement and early school leaving (ESL), focusing on Secure Base and Safe Haven attachment dimensions and the influence of vulnerability factors.

Methods: The review followed the PRISMA guidelines and included 45 empirical quantitative studies (2018–2022) sourced from Academic Search Complete, ERIC, Scopus and Web of Science. Inclusion criteria were English-written quantitative methodology studies, with TSR as the independent variable and academic outcomes as the dependent variable. Exclusion criteria included longitudinal designs, purely qualitative studies, correlational analyses, studies lacking key variables or presenting reversed relationships, those conducted in e-learning environments, university settings, extreme schooling conditions and non-English language studies. A descriptive and narrative style analysis was used to synthesize the results based on Safe Haven, Secure Base and Global dimensions.

Results and discussion: Key findings highlighted the significant role of TSR in influencing academic engagement, achievement, and ESL, particularly from vulnerable populations. The synthesis of results indicated that positive TSRs are associated with improved academic outcomes, while negative TSRs can exacerbate disengagement and underachievement. Limitations of the evidence included potential publication bias and the lack of quality control measures, as well as the exclusion of longitudinal and qualitative studies. The findings underscore the significance of a holistic understanding of the TSR in education, highlighting its multifaceted impact on student success and suggesting that future research should consider qualitative and longitudinal studies and expand the scope to studies in non-English language.

Poor educational outcomes in European countries have increasingly gained the attention of schools and policymakers. According to Eurostat, in 2022 < 50% of adults aged 25–74 had completed tertiary education across member states (Eurostat, 2022). Given the role of low educational attainment in perpetuating intergenerational exclusion (Mastekaasa and Birkelund, 2023), it is crucial to identify the relational factors associated with (dis)engagement, (under)achievement and Early School Leaving (ESL). Growing recognition of the importance of emotions and relationships in education has shed light on the critical role of teacher-student relationships (TSR) as a promoter of academic success (Helen Immordino-Yang et al., 2018).

Wubbels et al. (2014) described TSR as the interpersonal meaning both students and teachers assign to their interactions. TSR has been examined through different theoretical perspectives, such as attachment theory and self-determination theory, resulting in diverse instruments designed to measure it.

Bowlby's attachment theory (Ainsworth and Bowlby, 1991) is frequently employed to examine adult-child relationships and their influence on developmental outcomes like school adjustment (Pianta and Steinberg, 1992). Attachment theorists suggest that individuals, especially children, form close emotional bonds with primary caregivers, shaping their social and emotional development and academic engagement and achievement (Dias et al., 2024). A supportive TSR can thus provide students with a Safe Haven in times of distress, fostering their academic and personal growth, and a Secure Base to explore (Hamre and Pianta, 2001; Sabol and Pianta, 2012). In this context, Safe Haven responses refer to a teacher's ability to regulate a student's complex emotions, offering comfort and security. Secure Base responses involve supporting a student's autonomy, encouraging exploration, and providing praise for new achievements. Together, these attachment dimensions play a fundamental role in shaping educational outcomes.

The Self-determination theory (Ryan and Deci, 2000), starting from a different theoretical starting point, defends a similar fundamental idea, emphasizing TSR's role in fulfilling students' psychological needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. When teachers support autonomy, offer constructive feedback, and foster a sense of belonging, students' intrinsic motivation and academic engagement are enhanced (Niemiec and Ryan, 2009). In both theories, the TSR serves as a key determinant of students' emotional security and motivation and, thus, learning and achievement.

For disadvantaged students, such as those from low socioeconomic status (SES), migrant backgrounds or learning disabilities, positive TSRs offer unique opportunities for inclusion. Vulnerable populations often face additional barriers to academic success, including limited access to resources, social exclusion and emotional distress (Liu et al., 2024; Morton, 2015; Onsès-Segarra et al., 2023; Scanlon et al., 2019; Seynhaeve et al., 2024). Positive TSRs can play a crucial role in mitigating these challenges by providing emotional support, fostering a sense of belonging, and enhancing student engagement (Borgonovi and Ferrara, 2020). Studies have shown that strong adult-student relationships can mitigate social exclusion and improve academic outcomes for those students (Buyse et al., 2011; Jiang and Dong, 2020; Martin et al., 2017; Pérez-Salas et al., 2021; Sadoughi and Hejazi, 2023; Ungar et al., 2019; Zolkoski, 2019).

Given the TSR significance for student success (Ansari et al., 2020; Lei et al., 2023; McGrath and Van Bergen, 2015; Roorda et al., 2021), we aim to explore teachers' role as attachment-like figures (García-Rodríguez et al., 2023; Pianta and Steinberg, 1992; Riley, 2011; Verschueren and Koomen, 2012) and their influence on students' academic outcomes.

Previous reviews (Lei et al., 2023; Roorda et al., 2011) have highlighted the positive impact of TSR on (dis)engagement and (under)achievement, with stronger effects for disadvantaged students. However, gaps remain, particularly regarding the role of social vulnerabilities and the generalizability of results across different regions and contexts. Furthermore, prior studies have been limited in scope, focusing on English-speaking countries and mainland China (Lei et al., 2023; Roorda et al., 2011), respectively, and covering articles before 2016 (Quin, 2017; Roorda et al., 2017), which may limit their relevance to contemporary dynamics, as they do not account for recent educational trends, and the diverse sociocultural contexts present in other regions.

This systematic review seeks to address these limitations by mapping the latest evidence of TSR's role in academic (dis)engagement, (under)achievement, and ESL within an attachment-informed framework. It aims to categorize TSR variables into Safe Haven, Secure Base and Global dimensions, providing a more up-to-date and comprehensive analysis of TSR's influence on educational outcomes. Moreover, it seeks to understand how those dynamics work for vulnerable populations.

This research aims to map the relational dimensions of the TSR and the degree of relation with academic (under)achievement, academic (under)engagement and school dropout from an attachment theory perspective. To achieve this goal, two specific objectives have been delineated:

1. To identify and classify the aspects of the TSR that influence academic (dis)engagement, (under)achievement, and ESL within the framework of Secure Base and Safe Haven attachment dimensions.

2. To understand how vulnerability factors shape the relationship between TSR and academic (dis)engagement, (under)achievement and ESL in vulnerable populations.

In this study, “vulnerable populations” refers to students with characteristics historically associated with educational exclusion, including those from migrant backgrounds, ethnic minorities, students with limited or no parental care, students with disabilities or learning difficulties, and students from low socio-economic status (SES) families. Additionally, the study will examine other factors that contribute to vulnerability, as well as those that help mitigate its effects.

The search was conducted in March 2023 on the following online databases: ERIC, Academic Search Complete, Scopus, and WoS. Table 1 shows the combination of the different terms used in the search. The terms of each axis were included with the “OR” nexus, and the combination of the four axes with the “AND” nexus. In this way, at least one word from each axis had to appear simultaneously in the search results. Please consider that the symbol “*” is used in database search syntax to indicate that all variations or combinations of a word (eg: bond“*” = bonding, bondings, bonds) are included in the search results. The search strategy was implemented through keyword research. Only academic journals in English from 2018 to 2022 have been selected.

The studies were chosen with the following eligibility criteria:

a) Quantitative methodology articles.

b) Articles with TSR as the independent variable and academic outcomes as the dependent variable.

The exclusion criteria were:

a) Articles with longitudinal designs. Given the methodological differences between longitudinal and cross-sectional studies, this decision maintains internal coherence. Longitudinal articles will be analyzed in a separate study to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon.

b) Articles that examined only correlational analysis between TSR and academic outcomes, as the focus of this review is on studies that explore causal relationships (or hypothesis), although in cross-sectional designs.

c) Lack of at least one of the key variables or reversed relationship between TSR and academic outcomes.

d) Studies conducted in e-learning, university contexts, extreme conditions (COVID-19, armed conflict, natural disaster, child hospitalization, food insecurity, etc.), health programs, or physical education outcomes.

e) Systematic reviews, meta-analysis, intervention design/evaluation, instrument validation papers and, purely qualitative studies.

The article selection process was conducted in three phases. First, titles and abstracts were screened, followed by a full-text review, and finally, all the necessary information for article analysis was gathered. Two researchers independently evaluated all articles across each phase using a double-blind process. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion until a consensus was reached.

The database search yielded 912 articles, which were reduced to 741 after duplicate removal. During abstract screening in Covidence systematic review software (http://www.covidence.org), articles unrelated to our independent and dependent variables were excluded, leaving 187 for full-text review. At this stage, 142 studies were excluded based on following criteria:

• 37 had longitudinal designs.

• 35 did not investigate academic outcomes.

• 16 had qualitative designs.

• 16 used non-causal statistical analysis (e.g., correlational analysis, PCA, cluster analysis, factor analysis, MCA).

• 12 did not have the TSR as the independent variable.

• 10 evaluated interventions.

• 7 aimed to validate instruments.

• 6 were meta-analyses and systematic reviews.

• 3 were not in English.

Next, 45 articles were included in the final analysis. Figure 1 illustrates the article selection process.

The extraction phase was conducted using Covidence, employing a structured template designed to collect information on article specifics (authors, publication year, DOI), socio-demographic characteristics (sample size, age, school level, country), theoretical framework, and the vulnerable population studied. Additional data points included informant type, study design, statistical techniques, and the effect size's coefficient predicting how TSRs impact outcomes, including mediators and moderators, as well as barriers and promoters. Effect sizes were classified following Cohen's (1988) guidelines, with only standardized Beta coefficients (β) greater than ±0.10 being considered, aligned with the objectives of the study to identify and map TSR dimensions previously related to school outcomes. The extracted data were then exported to Excel for further analysis.

The studies analyzed had sample sizes ranging from 137 to 17,000 students, with an average student age of 13.5 years (SD = 1.2), reflecting a focus on secondary schools (78%). Variables were categorized by informant type: child-reported, teacher-reported, or third parties (e.g., GPA or school registers). Most studies used child-reported questionnaires to assess the TSR and academic outcome, while fewer relied on teacher-reported questionnaires or objective measures like GPAs and school registries. Geographically, most of the studies were conducted in North America and Asia, with a small percentage conducted in Europe (20%). Detailed information on the article's descriptive data is provided in Table 2.

The variables identified in the analyzed articles are classified into two key attachment dimensions based on secure attachment theory: Safe Haven and Secure Base (Sabol and Pianta, 2012). The Safe Haven dimension refers to teachers providing emotional support, comfort, and protection, while Secure Base dimension involves teachers fostering autonomy and exploration. A broader “Global TSR” dimension was introduced to classify variables that encompass both Safe Haven and Secure Base elements, offering a holistic measure of TSR quality.

In total, 36 variables were identified: eight as Safe Haven, 10 as Secure Base and 18 as Global TSR (Table 3). The variables were classified by experienced authors, with positive and negative valence indicating their impact on TSR quality, based on the content of each variable's measurement instrument.

Among Safe Haven variables, two have a negative, and seven have a positive valence. Similarly, in the Secure Base dimension, two variables exhibit negative valence, and seven show positive valence. For Global TSR variables, 13 have a positive valence and five are negative. The variable “support” was classified into different dimensions depending on the authors' conceptualization: general support, reported as “autonomy, emotion and ability support”, in the Global TSR, emotional support in Safe Haven, and autonomy, behavioral, learning and positive support in Secure Base.

Outcome variables were categorized into three groups: (dis)engagement, (under)achievement, and ESL. School (dis)engagement was divided into behavioral (attendance, class participation), cognitive (interest, motivation), and emotional (affective responses such as motivation and enjoyment) (Archambault et al., 2009; Fredricks et al., 2004). (Under)achievement covered academic performance and self-reported skills in subjects like math, language, and science skills. Most studies focused on (dis)engagement outcomes, while a third considered (under)achievement, and only one study examined TSR's relationship with ESL (Noble et al., 2021) (Table 4).

A descriptive and narrative style analysis of the results was employed, useful for mapping the TSR dimensions and exploring their impact on academic outcomes. This approach enabled the integration of findings with the theoretical framework of attachment theory, offering a conceptual perspective on the results.

The review of global TSR was based on 25 articles, showing effects that ranged from small to large (Table 5). The majority of these studies focused on secondary school samples, while only six examined kindergarten and primary school populations. Several studies (Feng et al., 2019; Kang et al., 2021; Pham et al., 2022; Sethi and Scales, 2020; Teuscher and Makarova, 2018) highlighted a significant positive relationship between TSR quality and behavioral, cognitive and emotional engagement, while reducing behavioral disengagement.

Support variables were also critical. Peng et al. (2022) demonstrated that autonomy, emotion, and ability support had a significant effect on academic engagement (β = 0.47, p < 0.01) and perceived teacher support had a moderate effect on academic achievement (β = 0.43; p < 0.01), mediated by cognitive engagement. Social, emotional and behavioral support (Vargas-Madriz and Konishi, 2021; Saleh et al., 2019) showed moderate effects on engagement (β = 0.35, p < 0.001; β = 0.25, p < 0.001).

Trust was another key factor. Atik and Özer (2020) and Pham et al. (2022) identifying positive influence on engagement, while Atik and Özer (2020) noted trust reduced emotional and behavioral disengagement (β = −0.29, p < 0.05).

Negative TSR dimensions, such as conflict, had adverse effects on engagement (Kang et al., 2021; Pakarinen et al., 2021; Rhoad-Drogalis et al., 2018). Both Buzzai et al. (2022) and Pakarinen et al. (2021) reported inverse associations between negative TSR and academic achievement. Wu et al. (2022) linked negative TSR to lower academic achievement through the mediation of test anxiety.

One study examined TSR's role in ESL. Noble et al. (2021) found that positive TSR reduces students' self-reported dropout risk (B = −1.28; p > 0.001).

These findings collectively suggest that high-quality TSRs, defined by various forms of support and trust, play a crucial role in enhancing student engagement across behavioral, cognitive and emotional domains. Additionally, they help reduce disengagement and the risk of dropout. In contrast, negative TSRs have the opposite effect, undermining engagement and increasing the likelihood of disengagement and school dropout.

A total of 13 articles used the Safe Haven dimension's variables, with effects ranging from small to moderate (Table 5). Most of these studies focused on primary school populations, with only five specifically targeting secondary school students. Dever et al. (2022) found strong positive effects of teachers' caring attitudes on cognitive and behavioral engagement (β = 0.60; p < 0.001), while Enoch and Asogwa (2021) observed a link between teacher-student relatedness and improved academic achievement (β = 0.44; p < 0.05). Emotional trust and support also positively influenced engagement (β = 0.40; 0.41; 0.42; < 0.001) (Pham et al., 2022; Hong et al., 2020).

Negative associations were also identified, with greater teacher attachment reducing behavioral disengagement (β = −0.22; p < 0.001) (Williford et al., 2021). On the other hand, teacher discrimination had negative effects on academic achievement, as minority ethnic students who reported no perceived discrimination had significantly higher odds of achieving better grades (OR = 1.64; p < 0.05) compared to those experiencing discrimination (Bryan et al., 2022). Additionally, school bonding partially mitigated the adverse effects of teacher discrimination on academic outcomes (OR = 1.52; p < 0.05) (Bryan et al., 2022).

These findings collectively highlight that emotional support and caring attitudes from teachers are essential for enhancing student engagement and academic achievement, particularly among primary school students. Additionally, addressing discrimination is critical to fostering improved academic outcomes.

Ten studies examined Secure Base variables, with effects ranging from small to moderate (Table 5). In this case, nearly all the studies focused on secondary school students, with only one exception. Regarding support variables, Chen et al. (2022) observed direct and indirect effects of teachers' behavioral support on emotional engagement (β = 0.18, p < 0.001), also when mediated by psychological sushi—understood as an individual's psychological quality or resilience encompassing traits such as adaptability, self-regulation, social competence—and self-efficacy. Ayaz et al. (2021) found a significant direct effect of teachers' autonomy support on school attachment (β = 0.20; p < 0.001), with an additional indirect effect mediated by intrinsic motivation. Teacher praise was strongly linked to academic achievement (B = 1.58; p < 0.01; Tan et al., 2022).

Interestingly, Filippello et al. (2019) found a positive link between teacher-perceived psychological control (teachers engaging in psychological controlling tactics) and academic achievement (β = 0.56; p < 0.01), possibly influenced by mediating factors (see next section). Conversely, Cohen et al. (2020) noted a negative effect of teacher conditional negative regard on cognitive engagement (β = −0.26; p < 0.01; β = −0.26; p < 0.01).

These findings suggest that teacher support and praise are crucial for promoting emotional engagement and academic achievement. However, the use of controlling tactics may have mixed impacts, potentially influencing cognitive engagement and wellbeing in both positive and negative ways.

Several studies have explored how engagement mediates the link between TSR and academic achievement. For example, school alienation mediated the relationship between trust in teachers and academic achievement (Atik and Özer, 2020). Filippello et al. (2019) identified significant relationships between teachers' perceived autonomy support, psychological control and academic achievement, mediated by need satisfaction, need frustration, absences and school refusal, with the latter two seen as forms of disengagement. Specifically, their model revealed that teacher-perceived autonomy support positively influenced need satisfaction (β = 0.21) and negatively influenced need frustration (β = −0.36), while teacher-perceived psychological control negatively influenced need satisfaction (β = −0.15) and positively influenced need frustration (β = 0.31). Need satisfaction was linked to fewer absences (β = −0.17) and reduced school refusal (β = −0.08), whereas need frustration increased absences (β = 0.39) and school refusal (β = 0.40). Both absences and school refusal were negatively associated with academic achievement (β = −0.17 and β = −0.15, respectively). These findings underscore the complex interplay between teacher behaviors, student needs, and academic outcomes.

Emotional engagement also plays a mediating role, albeit with a small effect size (β = 0.04 to 0.10; Liu et al., 2024; Wu et al., 2022), while behavioral engagement, showed stronger effects, with coefficients ranging from β = 0.21 to β = 0.24 (Sethi and Scales, 2020). Cognitive engagement was similarly found to mediate the relationship between teacher support and academic achievement (Krauss et al., 2022).

In synthesis, emotional, behavioral, and cognitive engagement act as key mediators in the relationship between TSRs and academic achievement. The dynamic interaction between teacher behaviors, student needs, and academic outcomes underscores the critical role of fostering TSRs to promote overall student success.

The overarching pattern across these dimensions reveals that positive TSRs, defined by support, trust, and emotional care, are crucial for enhancing student engagement and academic achievement. Mitigating negative influences, such as discrimination and the use of controlling tactics, is essential to fully harness the benefits of TSRs. Furthermore, the mediating role of engagement emphasizes the interconnected nature of these relationships.

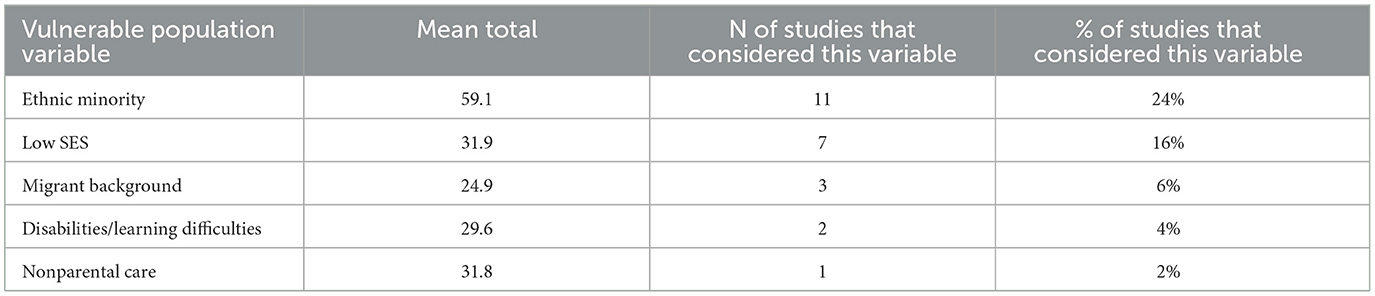

Less than 30% of the examined articles considered the effect of the TSR on the academic outcomes of vulnerable populations (see Table 6). The percentages presented in the fourth column reflect the proportion of the total 45 studies included in the systematic review that considered vulnerability populations in their studies. As it shows, fewer than half of the studies addressed vulnerable populations, and some of these studies examined multiple vulnerability variables, though not always in an intersectional manner. For instance, Bryan et al. (2022) included populations characterized by ethnic minority status, migrant background, and low socioeconomic status (SES), but analyzed the impact of each variable on academic achievement separately.

Table 6. Total mean, number and % of studies that consider the vulnerable population in the research.

As shown in Table 6, the most frequently studied vulnerable population was students from ethnic minority backgrounds, with fewer studies addressing other groups.

Although most articles treated male students as a demographic variable, they are often perceived as facing greater academic challenges than their female counterparts (Alexander et al., 1997). Therefore, we considered gender a potentially significant variable, particularly when authors distinguished between outcomes for boys and girls to identify any disadvantages faced by either group (Gini et al., 2018).

In the following sections, we explore how vulnerability characteristics act as barriers or promoters of the TSR, or moderate the TSR's influence on academic outcomes.

Bryan et al. (2022) found that belonging to an ethnic minority can be a barrier to TSR, with discriminatory attitudes from teachers negatively affecting the academic achievement of urban Caribbean Black and African American adolescents (OR = 1.64; p < 0.05).

SES and language proficiency also influence TSR. Xuan et al. (2019) identified SES as a significant predictor of TSR, with higher SES positively influencing TSR (β = 0.11; p < 0.01), suggesting that lower SES may serve as a barrier, particularly in relationships with math teachers. However, no significant effect was found on the relationship with language teachers. Atalan Ergin and Akgül (2023) highlights that high language proficiency significantly improves the perception of teacher support (β = 0.17, p < 0.05), suggesting that language skills play a critical role in fostering positive TSR among war-affected immigrant students.

Concerning gender, Romano et al. (2021) revealed that male students perceived greater levels of teacher emotional support compared to their female counterparts (β = 0.26, p < 0.001).

Bottiani et al. (2020) demonstrated that culturally responsive teachers can moderate the impact of discrimination on academic disengagement of ethnic minority students (β = 0.19, p < 0.001).

Sengul et al. (2019) revealed how students living with two parents tend to achieve higher academically when reporting positive TSRs, while students living with guardian(s) or a single parent showed lower academic achievement, even with positive TSRs (γ = −0.65; p < 0.05). Pham et al. (2022) and Rhoad-Drogalis et al. (2018) found that having a caring and communicative teacher whom they can trust significantly improves the academic engagement of students with disabilities or learning difficulties (β = 0.17, p < 0.05, β = 0.30, p < 0.001 and β = 0.40, p < 0.001 respectively).

Concerning gender, Gini et al. (2018) found that perceived teacher unfairness has higher effects on girls (β = −0.60, p < 0.001) and high school students (β = −0.55, p < 0.001) than on boys (β = −0.47, p < 0.001) and middle school students (β = −0.47, p < 0.001), influencing overall school satisfaction.

These findings suggest that vulnerability factors, including ethnicity, SES, migrant backgrounds, and family structure, can significantly influence TSRs either hindering or enhancing them. Culturally responsive teaching and emotional support are critical in mitigating the negative effects of these factors, fostering stronger TSRs, and promoting academic engagement and achievement.

The first aim of this systematic review is to identify and classify aspects of TSR that influence students' academic outcomes within the attachment framework, building on previous systematic reviews (Lei et al., 2023; Quin, 2017; Roorda et al., 2017). By applying the attachment framework, the review provides a richer understanding of relational dynamics in education and offers the potential to design targeted interventions. Notably, 55% of the reviewed articles used Global TSR variables, lacking a clear theoretical foundation or adopting alternative frameworks like the Self-determination theory (SDT). This trend likely reflects a focus on secondary education, where SDT is widely used (Howard et al., 2021), while attachment theory is more prevalent in studies on younger students (García-Rodríguez et al., 2023), particularly concerning the Safe Haven dimension.

TSR-related variables linked to attachment theory were classified into Safe Haven and Secure Base dimensions. Safe Haven variables showed moderate effects on students' (dis)engagement and (under)achievement, underscoring teachers' roles in providing emotional support and regulation. Secure Base variables, particularly teacher praise, demonstrated strong effects on academic achievement, suggesting that constructive feedback encourages student effort. These results align with García-Rodríguez et al.'s (2023) systematic review, which highlighted the role of teacher's closeness, conflict and dependence on primary school students' academic outcomes. Notably, only one study focused on ESL, likely due to the inclusion of cross-sectional studies, as ESL is typically studied longitudinally (Archambault et al., 2009; Henry et al., 2012). A forthcoming review will focus on longitudinal studies to complement these findings.

The second objective is to understand how vulnerability factors shape the relationship between TSR and academic outcomes in vulnerable populations. The review reveals a substantial gap since < 30% of the studies considered vulnerability factors. Situational factors like ethnic minority status, migrant background and low SES negatively affected TSR and subsequently academic outcomes, though vulnerable students may also be responsive to positive teacher relationships. The review's findings echo Muller's (2001) research, which identifies teachers' care and support as a key factor in mitigating underachievement in ethnic minority and low SES students. In line with the literature on underperforming youth (O'Malley et al., 2015), it also reveals that vulnerability factors like living with guardians or single parents negatively impact academic achievement. Additionally, a teacher's sense of purpose emerged to strengthen TSRs, likely through fostering emotional availability, as suggested by Lavy and Bocker (2018). While gender was often treated as a demographic factor, it was included in the vulnerability analysis differences between boys and girls were noted. However, no studies explored the intersection of gender with other vulnerabilities, suggesting this is an area for future research.

The main findings emphasize the significance of fostering positive and secure TSRs to enhance student engagement and achievement, in line with previous research (García-Rodríguez et al., 2023; Lei et al., 2023; Quin, 2017; Roorda et al., 2017). Teachers act as attachment-like figures, providing both a Safe Haven for emotional regulation and a Secure Base for exploration (Hamre and Pianta, 2001; Pianta and Steinberg, 1992; García-Rodríguez et al., 2023). This review also confirms the mediating role of academic engagement in the TSR-academic outcomes relationship, as shown in previous reviews (Quin, 2017; Roorda et al., 2017).

Interpreting these findings requires consideration of the cultural and national contexts of the reviewed samples. Most studies were conducted in North America and Asia, with limited representation from other contexts. Educational norms in collectivistic countries like China, where teacher-student roles are hierarchical more defined (Jin and Cortazzi, 2006), contrast with individualistic countries like the USA and Canada, where students play a more active role in learning (Staub and Stern, 2002). Cultural factors such as psychological suzhi also shape resilience across contexts, underscoring the need to expand TSR research in diverse settings for a more comprehensive understanding of these dynamics.

These findings have practical implications for understanding how schools and teachers can enhance student engagement and, subsequently, achievement, particularly for those from vulnerable contexts. For example, incorporating active learning strategies and providing opportunities for student-centered approaches can help create a positive and inclusive learning environment. Additionally, fostering a shared vision that prioritizes students' well-being and academic success is crucial. Encouraging teachers to work collaboratively and assume joint responsibility for students' care can further support these goals.

The findings of this systematic literature review should be interpreted considering limitations. First, there is the possibility of publication bias, as articles with minimal or no significant effects are often underrepresented in publications. Second, our review was limited to peer-reviewed, quantitative cross-sectional studies, excluding qualitative and longitudinal studies, although the latter will be explored in a future publication. It would be beneficial to explore studies employing alternative research designs. Third, the absence of comparable measures across studies poses challenges in synthesizing and understanding how sample size variability influences results. Additionally, while this review is not a meta-analysis, the disregard for non-significant results and the lack of a formal quality appraisal of the included studies may partially influence the reliability of the findings. Furthermore, the articles in this systematic review did not analyze the impacts of COVID-19 on the relationship between students and teachers, nor how these impacts influenced academic outcomes. This omission is considered a limitation, as COVID-19 significantly disrupted the academic experiences of many children worldwide, with ongoing consequences that continue to be studied (Mazrekaj and De Witte, 2024; Pokhrel and Chhetri, 2021). Finally, this review did not fully address how global TSR variables may influence academic outcomes across different age groups.

Likewise, future research should consider the role of barriers and promoters of TSR more thoroughly within search strategy. Vulnerable populations, in particular, should be a primary focus to unravel the complex interactions between TSR, vulnerability and academic outcomes. A deeper exploration of these populations will shed light on how various ecological factors influence resilience and academic success among students at risk of social exclusion. Moreover, future research should also consider the impact of COVID-19, particularly in articles published from 2022 onwards, and also explore the influence of online digital dynamics on learning outcomes, as these factors were not addressed in the current review due to the timing of data collection and specific exclusion criteria. Finally, it should further examine the global TSR variables to provide more specific insights into their age-dependent effects.

This study contributes to the expanding body of literature on the influence of TSR on academic outcomes. Despite certain limitations, the findings offer crucial insights for developing evidence-based interventions that strengthen TSR from an attachment-focused perspective. Such interventions could enhance student engagement, improve academic achievement, and reduce ESL rates, especially among those students at heightened risk of social exclusion.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

GD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AH: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. AB: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. AC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. CP: Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This article has been elaborated within the research project Let's Care: Building Safe and Caring Schools to Foster Educational Inclusion and School Achievement, funded by the European Commission under the Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Programme, Contract No: 101059425.

We express our heartfelt gratitude to all the researchers at Comillas Pontifical University who are involved in the project “Let's Care”.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1522997/full#supplementary-material

Ainsworth, M. S., and Bowlby, J. (1991). An ethological approach to personality development. Am. Psychol. 46, 333–341. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.46.4.333

Alexander, K. L., Entwisle, D. R., and Horsey, C. S. (1997). From first grade forward: Early foundations of high school dropout. Sociol. Educ. 70, 87–107. doi: 10.2307/2673158

Alnawasreh, R. I., Norb, M. Y. M., Sulimanc, A., Ismeil, R., Yusoff, M., and Nor, M. (2019). Promulgating factors influencing students' academic achievement: unveiling the international high schools setting. Int. J. Innov. Creat. Change 7, 109–127.

Ansari, A., Hofkens, T. L., and Pianta, R. C. (2020). Teacher-student relationships across the first seven years of education and adolescent outcomes. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 71:101200. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2020.101200

Archambault, I., Janosz, M., Morizot, J., and Pagani, L. (2009). Adolescent behavioral, affective, and cognitive engagement in school: relationship to dropout. J. School Health 79, 408–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00428.x

Atalan Ergin, D., and Akgül, G. (2023). Academic well-being of immigrants with pre-migration war traumas: the role of parents, teachers and language proficiency. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 51, 491–511. doi: 10.1080/01926187.2021.2015724

Atik, S., and Özer, N. (2020). The direct and indirect role of school attitude alienation to school and school burnout in the relation between the trust in teacher and academic achievements of students. Ted Egitim Ve Bilim 45, 441–458. doi: 10.15390/EB.2020.8500

Ayaz, A., Tomar, I. H., Can, G., and Satici, S. A. (2021). Autonomy support and children's school attachment: motivation as a Mediator | Özerklik Destegi ve Çocuklarin Okula Bagliligi: Motivasyonun Aracilik Rolü. Turk. Psychol. Counsel. Guidance J. 11, 591–602. doi: 10.17066/tpdrd.1051702

Borgonovi, F., and Ferrara, A. (2020). Academic achievement and sense of belonging among non-native-speaking immigrant students: the role of linguistic distance. Learn. Individ. Differ. 81:101911. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2020.101911

Bottiani, J. H. H., McDaniel, H. L. L., Henderson, L., Castillo, J. E. E., and Bradshaw, C. P. P. (2020). Buffering effects of racial discrimination on school engagement: the role of culturally responsive teachers and caring school police. J. Sch. Health 90, 1019–1029. doi: 10.1111/josh.12967

Bryan, J., Williams, J. M., Kim, J., Morrison, S. S., and Caldwell, C. H. (2022). Perceived teacher discrimination and academic achievement among urban Caribbean Black and African American youth: school bonding and family support as protective factors. Urban Educ. 57, 1487–1510. doi: 10.1177/0042085918806959

Buyse, E., Verschueren, K., and Doumen, S. (2011). Preschoolers' attachment to mother and risk for adjustment problems in kindergarten: can teachers make a difference? Soc. Dev. 20, 33–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00555.x

Buzzai, C., Filippello, P., Caparello, C., and Sorrenti, L. (2022). Need-supportive and need-thwarting interpersonal behaviors by teachers and classmates in adolescence: the mediating role of basic psychological needs on school alienation and academic achievement. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 25, 881–902. doi: 10.1007/s11218-022-09711-9

Chen, X., Zhao, H., and Zhang, D. (2022). Effect of teacher support on adolescents' positive academic emotion in china: mediating role of psychological suzhi and general self-efficacy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:16635. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192416635

Civitillo, S., Göbel, K., Preusche, Z., and Jugert, P. (2021). Disentangling the effects of perceived personal and group ethnic discrimination among secondary school students: the protective role of teacher-student relationship quality and school climate. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 177, 77–99. doi: 10.1002/cad.20415

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cohen, R., Moed, A., Shoshani, A., Roth, G., and Kanat-Maymon, Y. (2020). Teachers' conditional regard and students' need satisfaction and agentic engagement: a multilevel motivation mediation model. J. Youth Adolesc. 49, 790–803. doi: 10.1007/s10964-019-01114-y

Demirtaş-Zorbaz, S., and Ergene, T. (2019). School adjustment of first-grade primary school students: effects of family involvement, externalizing behavior, teacher and peer relations. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 101, 307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.04.019

Dever, B. V., Lathrop, J., Turner, M., Younis, D., and Hochbein, C. D. (2022). The mediational effect of achievement goals in the association between teacher-student relationships and behavioral/emotional risk. School Ment. Health 14, 880–890. doi: 10.1007/s12310-022-09527-0

Dias, P., Veríssimo, L., Carneiro, A., and Duarte, R. (2024). The role of socio-emotional security on school engagement and academic achievement: systematic literature review. Front. Educ. 9:1437297. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1437297

Dolapcloglu, S. (2019). Teacher support for a classroom setting that promotes thinking skills: an analysis on the level of academic achievement of middle school students. Cukurova Univ. Facult. Educ. J. 48, 1429–1454. doi: 10.14812/cufej.557616

Enoch, J. U., and Asogwa, V. C. (2021). Teacher-student relationship and attitude as correlates of students' academic achievement in agricultural science in senior secondary schools. African Educ. Res. J. 9, 600–605. doi: 10.30918/AERJ.92.20.019

Eurostat (2022). Educational Attainment Statistics. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Educational_attainment_statistics#The_populations_in_the_EU_Member_States_have_different_educational_attainment_levels_in_2022 (accessed November 5, 2024).

Feng, X., Xie, K., Gong, S., Gao, L., and Cao, Y. (2019). Effects of parental autonomy support and teacher support on middle school students' homework effort: homework autonomous motivation as mediator. Front. Psychol. 10:612. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00612

Filippello, P., Buzzai, C., Costa, S., and Sorrenti, L. (2019). School refusal and absenteeism: perception of teacher behaviors, psychological basic needs, and academic achievement. Front. Psychol. 10:1471. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01471

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., and Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 74, 59–109. doi: 10.3102/00346543074001059

García-Rodríguez, L., Iriarte Redín, C., and Reparaz Abaitua, C. (2023). Teacher-student attachment relationship, variables associated, and measurement: a systematic review. Educ. Res. Rev. 38:100488. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100488

Gini, G., Marino, C., Pozzoli, T., and Holt, M. (2018). Associations between peer victimization, perceived teacher unfairness, and adolescents' adjustment and well-being. J. Sch. Psychol. 67, 56–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2017.09.005

Hamre, B. K., and Pianta, R. C. (2001). Early teacher–child relationships and the trajectory of children's school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Dev. 72, 625–638. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00301

Helen Immordino-Yang, M., Darling-Hammond, L., and Krone, C. (2018). The Brain Basis for Integrated Social, Emotional, and Academic Development How Emotions and Social Relationships Drive Learning. Washington, DC: The Aspen Institute. National Commission on Social, Emotional & Academic Development.

Henry, K. L., Knight, K. E., and Thornberry, T. P. (2012). School disengagement as a predictor of dropout, delinquency, and problem substance use during adolescence and early adulthood. J. Youth Adolesc. 41, 156–166. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9665-3

Herrero Romero, R., Hall, J., and Cluver, L. (2019). Exposure to violence, teacher support, and school delay amongst adolescents in South Africa. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 89, 1–21. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12212

Hong, J. S., Lee, J., Thornberg, R., Peguero, A. A., Washington, T., and Voisin, D. R. (2020). Social-ecological pathways to school motivation and future orientation of African American adolescents in Chicago. J. Educ. Res. 113, 384–395. doi: 10.1080/00220671.2020.1838408

Howard, J. L., Bureau, J., Guay, F., Chong, J. X. Y., and Ryan, R. M. (2021). Student motivation and associated outcomes: a meta-analysis from self-determination theory. Persp. Psychological Sci. 16, 1300–1323. doi: 10.1177/1745691620966789

Jiang, S., and Dong, L. (2020). The effects of teacher discrimination on depression among migrant adolescents: mediated by school engagement and moderated by poverty status. J. Affect. Disord. 275, 260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.029

Jin, L., and Cortazzi, M. (2006). Changing practices in chinese cultures of learning. Lang. Cult. Curricul. 19, 5–20. doi: 10.1080/07908310608668751

Kang, D., Stough, L. M., Yoon, M., and Liew, J. (2021). The structural association between teacher-student relationships and school engagement: types and informants. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2:100072. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedro.2021.100072

Krauss, S., Wong, E. J. Y., Zeldin, S., Kunasegaran, M., Nga Lay Hui, J., Ma'arof, A. M., et al. (2022). Positive school climate and emotional engagement: a mixed methods study of chinese students as ethnocultural minorities in malaysian secondary schools. J. Adolesc. Res. 39, 1154–1192. doi: 10.1177/07435584221107431

Lavy, S., and Bocker, S. (2018). A path to teacher happiness? A sense of meaning affects teacher–student relationships, which affect job satisfaction. J. Happin. Stud. 19, 1485–1503. doi: 10.1007/s10902-017-9883-9

Lavy, S., and Naama-Ghanayim, E. (2020). Why care about caring? Linking teachers' caring and sense of meaning at work with students' self-esteem, well-being, and school engagement. Teach. Teach. Educ. 91:103046. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2020.103046

Lei, H., Wang, X., Chiu, M. M., Du, M., and Xie, T. (2023). Teacher-student relationship and academic achievement in China: evidence from a three-level meta-analysis. Sch. Psychol. Int. 44, 68–101. doi: 10.1177/01430343221122453

Liu, Y., Maltais, N. S., Milner-Bolotin, M., and Chachashvili-Bolotin, S. (2024). Investigating adolescent psychological wellbeing in an educational context using PISA 2018 Canadian data. Front. Psychol. 15:1416631. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1416631

Longobardi, C., Settanni, M., Lin, S., and Fabris, M. A. (2021). Student-teacher relationship quality and prosocial behaviour: the mediating role of academic achievement and a positive attitude towards school. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 91, 547–562. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12378

Martin, A. J., Cumming, T. M., O'Neill, S. C., and Strnadová, I. (2017). “Social and emotional competence and at-risk children's well-being: the roles of personal and interpersonal agency for children with adhd, emotional and behavioral disorder, learning disability, and developmental disability,” in Social and Emotional Learning in Australia and the Asia-Pacific, eds. R. J. C. E. Frydenberg, A. J. Martin (Singapore: Springer Singapore), 123–145.

Martin-Storey, A., Santo, J., Recchia, H. E., Chilliak, S., Caetano Nardi, H., and Moreira Da Cunha, J. (2021). Gender minoritized students and academic engagement in Brazilian adolescents: risk and protective factors. J. Sch. Psychol. 86, 120–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2021.03.001

Mastekaasa, A., and Birkelund, G. E. (2023). The intergenerational transmission of social advantage and disadvantage: comprehensive evidence on the association of parents' and children's educational attainments, class, earnings, and status. Europ. Soc. 25, 66–86. doi: 10.1080/14616696.2022.2059542

Mazrekaj, D., and De Witte, K. (2024). The impact of school closures on learning and mental health of children: lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Persp. Psychol. Sci. 19, 686–693. doi: 10.1177/17456916231181108

McGrath, K. F., and Van Bergen, P. (2015). Who, when, why and to what end? Students at risk of negative student-teacher relationships and their outcomes. Educ. Res. Rev. 14, 1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2014.12.001

Morton, B. M. (2015). Barriers to academic achievement for foster youth: the story behind the statistics. J. Res. Childh. Educ. 29, 476–491. doi: 10.1080/02568543.2015.1073817

Muller, C. (2001). The role of caring in the teacher-student relationship for at-risk students. Soc. Inq. 71, 241–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-682X.2001.tb01110.x

Nakamura-Thomas, H., Sano, N., and Maciver, D. (2021). Determinants of school attendance in elementary school students in Japan: a structural equation model. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 15, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13034-021-00391-5

Niemiec, C. P., and Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom: applying self-determination theory to educational practice. Theory Res. Educ. 7, 133–144. doi: 10.1177/1477878509104318

Noble, R. N., Heath, N., Krause, A., and Rogers, M. (2021). Teacher-student relationships and high school drop-out: applying a working alliance framework. Can. J. School Psychol. 36, 221–234. doi: 10.1177/0829573520972558

O'Malley, M., Voight, A., Renshaw, T. L., and Eklund, K. (2015). School climate, family structure, and academic achievement: A study of moderation effects. School Psychol. Quart. 30, 142–157. doi: 10.1037/spq0000076

Onsès-Segarra, J., Carrasco-Segovia, S., and Sancho-Gil, J. M. (2023). Migrant families and Children's inclusion in culturally diverse educational contexts in Spain. Front. Educ. 8, 1–13. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1013071

Pakarinen, E., Lerkkanen, M.-K., Viljaranta, J., and von Suchodoletz, A. (2021). Investigating bidirectional links between the quality of teacher–child relationships and children's interest and pre-academic skills in literacy and math. child development. 92, 388–407. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13431

Peng, X., Sun, X., and He, Z. (2022). Influence mechanism of teacher support and parent support on the academic achievement of secondary vocational students. Front. Psychol. 13:863740. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.863740

Pérez-Salas, C. P., Parra, V., Sáez-Delgado, F., and Olivares, H. (2021). Influence of teacher-student relationships and special educational needs on student engagement and disengagement: a correlational study. Front. Psychol. 12:708157. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.708157

Pham, Y. K., Murray, C., and Gau, J. (2022). The inventory of teacher-student relationships: factor structure and associations with school engagement among high-risk youth. Psychol. Sch. 59, 413–429. doi: 10.1002/pits.22617

Pianta, R. C., and Steinberg, M. (1992). Teacher-child relationships and the process of adjusting to school. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 1992, 61–80. doi: 10.1002/cd.23219925706

Pokhrel, S., and Chhetri, R. (2021). A literature review on impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. Higher Educ. Future 8, 133–141. doi: 10.1177/2347631120983481

Quin, D. (2017). Longitudinal and contextual associations between teacher–student relationships and student engagement: a systematic review. Rev. Educ. Res. 87, 345–387. doi: 10.3102/0034654316669434

Rhoad-Drogalis, A., Justice, L. M., Sawyer, B. E., and O'Connell, A. A. (2018). Teacher–child relationships and classroom-learning behaviours of children with developmental language disorders. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 53, 324–338. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12351

Riley, P. (2011). Attachment Theory and the Teacher – Student Relationship, A Practical Guide for Teachers, Teacher Educators and School Leaders (First edit). London: Routledge.

Romano, L., Angelini, G., Consiglio, P., and Fiorilli, C. (2021). Academic resilience and engagement in high school students: the mediating role of perceived teacher emotional support. Eur. J. Investig. Health, Psychol. Educ. 11, 334–344. doi: 10.3390/ejihpe11020025

Roorda, D., Jak, S., Zee, M., Oort, F., and Koomen, H. (2017). Affective teacher-student relationships and students' engagement and achievement: a meta-analytic update and test of the mediating role of engagement. School Psych. Rev. 46, 239–261. doi: 10.17105/SPR-2017-0035.V46-3

Roorda, D., Koomen, H. M. Y., Spilt, J. L., and Oort, F. J. (2011). The influence of affective teacher-student relationships on students' school engagement and achievement: a meta-analytic approach. Rev. Educ. Res. 81, 493–529. doi: 10.3102/0034654311421793

Roorda, D., Zee, M., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2021). Don't forget student-teacher dependency! A Meta-analysis on associations with students' school adjustment and the moderating role of student and teacher characteristics. Attachm. Human Dev. 23, 490–503. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2020.1751987

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Sabol, T. J., and Pianta, R. C. (2012). Recent trends in research on teacher-child relationships. Attachm. Human Dev. 14, 213–231. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2012.672262

Sadoughi, M., and Hejazi, S. Y. (2023). Teacher support, growth language mindset, and academic engagement: the mediating role of L2 grit. Stud. Educ. Eval. 77:101251. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2023.101251

Saleh, M. Y., Shaheen, A. M., Nassar, O. S., and Arabiat, D. (2019). Predictors of school satisfaction among adolescents in Jordan: a cross-sectional study exploring the role of school-related variables and student demographics. J. Multidiscipl. Healthc. 12, 621–631. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S204557

Sasic, S. S., Simunic, A., and Klarin, M. (2021). The mediating role of teacher-pupil interaction in the relationship of pupil temperament to self-esteem and school success. Drustvena Istrazivanja 30, 509–531. doi: 10.5559/di.30.3.03

Scanlon, M., Jenkinson, H., Leahy, P., Powell, F., and Byrne, O. (2019). ‘How are we going to do it?' An exploration of the barriers to access to higher education amongst young people from disadvantaged communities. Irish Educ. Stud. 38, 343–357. doi: 10.1080/03323315.2019.1611467

Sengul, O., Zhang, X., and Leroux, A. J. (2019). A multi-level analysis of students' teacher and family relationships on academic achievement in schools. Int. J. Educ. Methodol. 5, 117–133. doi: 10.12973/ijem.5.1.131

Sethi, J., and Scales, P. C. (2020). Developmental relationships and school success: how teachers, parents, and friends affect educational outcomes and what actions students say matter most. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 63:101904. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101904

Seynhaeve, S., Vanbuel, M., Kavadias, D., and Deygers, B. (2024). Equitable education for migrant students? Investigating the educational success of newly arrived migrants in Flanders. Front. Educ. 9:1431289. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1431289

Staub, F. C., and Stern, E. (2002). The nature of teachers' pedagogical content beliefs matters for students' achievement gains: Quasi-experimental evidence from elementary mathematics. J. Educ. Psychol. 94, 344–355. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.94.2.344

Tan, M., Cai, L., and Bodovski, K. (2022). An active investment in cultural capital: structured extracurricular activities and educational success in China. J. Youth Stud. 25, 1072–1087. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2021.1939284

Teuscher, S., and Makarova, E. (2018). Students' school engagement and their truant behavior: do relationships with classmates and teachers matter? J. Educ. Learn. 7:124. doi: 10.5539/jel.v7n6p124

Ungar, M., Connelly, G., Liebenberg, L., and Theron, L. (2019). How schools enhance the development of young people's resilience. Soc. Indic. Res. 145, 615–627. doi: 10.1007/s11205-017-1728-8

Vargas-Madriz, L. F., and Konishi, C. (2021). The relationship between social support and student academic involvement: the mediating role of school belonging. Can. J. School Psychol. 36, 290–303. doi: 10.1177/08295735211034713

Verschueren, K., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2012). Teacher-child relationships from an attachment perspective. Attach. Hum. Dev. 14, 205–211. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2012.672260

Williford, A., Fite, P., Diaz, K., and Singh, M. (2021). Associations between different forms of peer victimization and school absences: the moderating role of teacher attachment and perceived school safety. Psychol. Sch. 58, 185–202. doi: 10.1002/pits.22438

Wu, F., Jiang, Y., Liu, D., Konorova, E., and Yang, X. (2022). The role of perceived teacher and peer relationships in adolescent students' academic motivation and educational outcomes. Educ. Psychol. 42, 439–458. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2022.2042488

Wubbels, T., Brekelmans, M., Pj, B., Wijsman, L., Mainhard, T., and Tartwijk, J. (2014). “Teacher-student relationships and classroom management,” in Handbook of Classroom Management, eds. E. J. S. Edmund Emmer (London: Routledge).

Xuan, X., Xue, Y., Zhang, C., Luo, Y., Jiang, W., Qi, M., et al. (2019). Relationship among school socioeconomic status, teacher-student relationship, and middle school students' academic achievement in China: Using the multilevel mediation model. PLoS ONE 14:e213783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213783

Keywords: teacher-student relationship, engagement, achievement, early school leaving, systematic review

Citation: Di Lisio G, Milá Roa A, Halty A, Berástegui A, Couso Losada A and Pitillas C (2025) Nurturing bonds that empower learning: a systematic review of the significance of teacher-student relationship in education. Front. Educ. 10:1522997. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1522997

Received: 05 November 2024; Accepted: 05 February 2025;

Published: 27 February 2025.

Edited by:

Darren Moore, University of Exeter, United KingdomReviewed by:

Eduardo Hernández-Padilla, Autonomous University of the State of Morelos, MexicoCopyright © 2025 Di Lisio, Milá Roa, Halty, Berástegui, Couso Losada and Pitillas. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Giulia Di Lisio, Z2RpbGlzaW9AY29taWxsYXMuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.