- 1Graduate School of Education, Akita University, Akita, Japan

- 2Department of Child Development, Takamatsu University, Takamatsu, Japan

- 3Kimitsu Special Needs School, Kimitsu, Japan

This study aims to clarify the content of leisure activity guidance recognized by special needs education teachers and identify gaps in recognition of these between teachers and vocational rehabilitation practitioners who collaborate in transition support. This study surveyed a total of 255 participants, comprising 129 special needs school teachers and 126 vocational rehabilitation practitioners. The participants responded to a survey on the importance of leisure activity guidance, which was developed through a literature review on leisure activity guidance in special needs education and interviews with special needs education teachers. Factor analysis identified four factors of leisure activity guidance: establishing a foundation for leisure implementation, expanding options for leisure activities, recognizing the value of leisure, and acquiring skills for leisure implementation. While special needs education teachers recognized the importance of leisure activity guidance, qualitative differences in perception were observed between them and the vocational rehabilitation practitioners. The study clarified the essential content of leisure activity guidance in special needs education. The findings are expected to contribute to the qualitative improvement of transition support from special needs education to broader society.

1 Introduction

Transition support from special needs education to broader society is crucial for individuals with disabilities. When transition support plans fail to align with the needs of individuals with disabilities, they can negatively affect outcomes such as employment and job retention (Snell-Rood et al., 2020). In the United States, inclusive education is promoted under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Individualized Education Plans (IEPs), tailored to each student’s needs, support continued education, vocational training, assisted employment, and the transition to independent living and social integration. For transition support to be effective, special needs education teachers and related organizations must collaborate (Povenmire-Kirk et al., 2018; Taylor et al., 2016). Such collaboration influences the achievement of students’ post-graduation goals (Scheef and McKnight-Lizotte, 2022; Wehman et al., 2015). In addition, initiatives such as the Special Olympics Unified Schools aim to involve both students with and without disabilities in inclusive sports. The aim is to promote healthy relationships between students by encouraging them to collaborate across their differences (Yin and Jodl, n.d.). Evidence-based initiatives such as these are already making a difference in promoting social participation for persons with disabilities.

In Japan, while special needs education promotes inclusive education based on the needs of students, guidance to alleviate difficulties in living and learning is provided not only through regular classes but also through specialized options at schools for students with disabilities. In this sense, Japan’s efforts in special needs schools represent a progressive approach to improving special needs education and promoting inclusive education. However, significant differences and challenges exist between Japanese and US approaches (Fujita, 2024; Nakao and Murata, 2019; Tsuzuki, 2008). The practices of special needs schools, where many children with disabilities attend, also require updates. This study focuses on special needs schools in Japan and aims to offer perspectives on promoting inclusive education and universal special needs education.

A critical issue arises when transition support between special needs education, which provides support during schooling, and vocational rehabilitation, which provides support after graduation, is poorly executed. In Japan, special support education and vocational rehabilitation do not effectively coordinate through IEPs. The government structure overseeing vocational rehabilitation operates separately from the educational administration, complicating the utilization and coordination of IEPs. Differences in attitudes toward support between special needs education teachers and vocational rehabilitation practitioners (Nota and Soresi, 2009), along with differences in experience and knowledge related to practice (Imai et al., 2023; Kim and Dymond, 2010), contribute to this issue. As a result, transition support for special education often occurs where these challenges are likely to surface.

For students with intellectual disabilities, special needs education must address not only current issues that arise during schooling but also future social participation after graduation. For individuals with disabilities, work is a meaningful goal (Trombly, 1995). Employment enhances personal self-esteem, social status, and community engagement (Frank, 2016). Community involvement depends on the opportunities and support available to persons with disabilities, making guidance in this area critical (Hall, 2016). Supporting work and experiencing success through work positively change individuals’ self-efficacy and self-concept (Strong, 1998). Additionally, work plays a significant role in maintaining the lives of individuals with disabilities and in shaping their identities (Dunn et al., 2008). In Japan, inclusive education is often misunderstood as simply integrating individuals into society. However, it goes beyond this to include persons with disabilities in their communities, taking on meaningful roles in community life (Institute on Community Integration, n.d.).

To improve the social participation of students with disabilities, educators must provide guidance not only on the soft skills necessary for maintaining relationships in the workplace but also on job performance during their schooling in special needs education. Research on employment continuation for individuals with disabilities highlights the need for support aimed at career development for transitioning to society (Roessler, 2002), a support system from families for employment continuation (Park, 2022; Park and Park, 2019), education focused on acquiring social and soft skills (Herrick et al., 2022), and training to develop self-determination skills (Thomas and Morgan, 2021).

Accordingly, the current study focuses on education related to leisure activities that support social life. Leisure activities are those performed during free time outside of essential life functions and labor, such as eating, sleeping, working, and housework. For individuals with disabilities, leisure activities significantly enhance their quality of life in society (Day and Alon, 1993). These activities are essential for rediscovering the meaning of daily life (Hammell, 2004). The stability of occupational life, including leisure, contributes to adaptation to work and employment continuation (McCarron et al., 1979; Nemoto, 2018; Wehman, 1977). Furthermore, individuals with disabilities who are unable to work for extended periods often experience an imbalance between work and leisure (Kvam et al., 2015). Hence, efforts to enrich life through leisure guidance are necessary (Kato, 2018; Yasukawa and Kobayashi, 2004). Leisure instruction is crucial for acquiring, enhancing, and maintaining leisure activities. However, reports indicate that students with disabilities may graduate without acquiring the necessary skills and support to work in the community, including adequate leisure education (Condon and Callahan, 2008). The ability to provide such education largely depends on teachers’ expertise, including their competency (Johnson, 2014) and knowledge of available resources (Smith, 2016).

Leisure education is implemented in special needs education to acquire, enrich, and maintain these leisure activities. Implementing leisure education in special needs education is useful in promoting social participation after graduation. However, establishing whether leisure education is provided during schooling from the perspective of transition support to society after graduation poses challenges. In other words, a gap exists between the leisure education provided by teachers and the leisure instruction required and demanded by vocational rehabilitation practitioners. Based on previous research, efforts must clarify the gaps in recognition of leisure guidance by special needs education teachers and vocational rehabilitation practitioners involved in transition support. Moreover, discussions must focus on the educational measures necessary to resolve these gaps. To address these requirements, this study aims to clarify the gaps in recognition of leisure guidance between special needs education teachers and vocational rehabilitation practitioners involved in transition support. Specifically, this study seeks to answer the following research questions:

RQ1: What content of leisure guidance do special needs education teachers recognize?

RQ2: Do special needs education teachers and vocational rehabilitation practitioners recognize leisure guidance differently?

RQ3: What challenges do special needs education teachers and vocational rehabilitation practitioners face in leisure guidance, and how do their experiences differ?

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participants

This study aimed to compare the perceptions of leisure activity guidance between special needs education teachers and vocational rehabilitation practitioners. Therefore, participants from both professions were included in this study.

The participants consisted of 538 teachers from 10 special needs schools for students with intellectual disabilities in Prefecture A, a rural area in Japan. Unlike special needs classes in regular schools, special needs schools in Japan cater specifically to children with disabilities. These schools are designed to help students overcome challenges related to their disabilities and achieve independence while receiving education equivalent to that of elementary, junior high, and high schools. The participant schools provide specialized instruction delivered by highly trained teachers. Teachers affiliated with these special needs schools generally receive education and certification in special needs education from four-year colleges and universities.

The study also included practitioners involved in employment support from all 337 Centers for Employment and Living Support for Persons with Disabilities, a vocational rehabilitation institution in Japan. The Centers for Employment and Living Support for Persons with Disabilities represent the primary vocational rehabilitation agency in Japan. This institution is operated by the labor administration, rather than the Japanese educational administration, thus entrusting it to local social welfare institutions. As a result, these centers function as external institutions relative to the special needs school. However, after graduation, it can be challenging for school teachers to maintain contact with their students, so many graduates receive assistance from the Centers for Employment and Living Support for Persons with Disabilities. Employment supporters offer not only work-related support for individuals with disabilities but also a comprehensive range of lifestyle assistance, including financial management, physical health management, and leisure activities. In this study, the participants included both the teachers responsible for education during school and the employment supporters providing life support after graduation.

2.2 Procedure

From 21 October to 17 November 2023, a request letter containing a link to an online survey was sent via email to special needs education teachers from 10 special needs schools for students with intellectual disabilities. We facilitated the survey via email by making individual face-to-face requests to the principals of all 10 special needs schools and obtained their consent to participate. From 1 November to 30 November 2023, we sent another request letter containing a link to the online survey via postal mail to vocational rehabilitation practitioners from the 337 Centers for Employment and Living Support for Persons with Disabilities. For mailing addresses, we utilized a database published by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare on its website.

2.3 Survey items

2.3.1 Basic attributes

Participants were asked to provide information on their gender (male, female, other); highest educational attainment [high school, vocational school, junior college, university, graduate school (master’s/doctorate)]; age as of 31 March 2024; and years of support experience.

2.3.2 Items related to leisure activity guidance

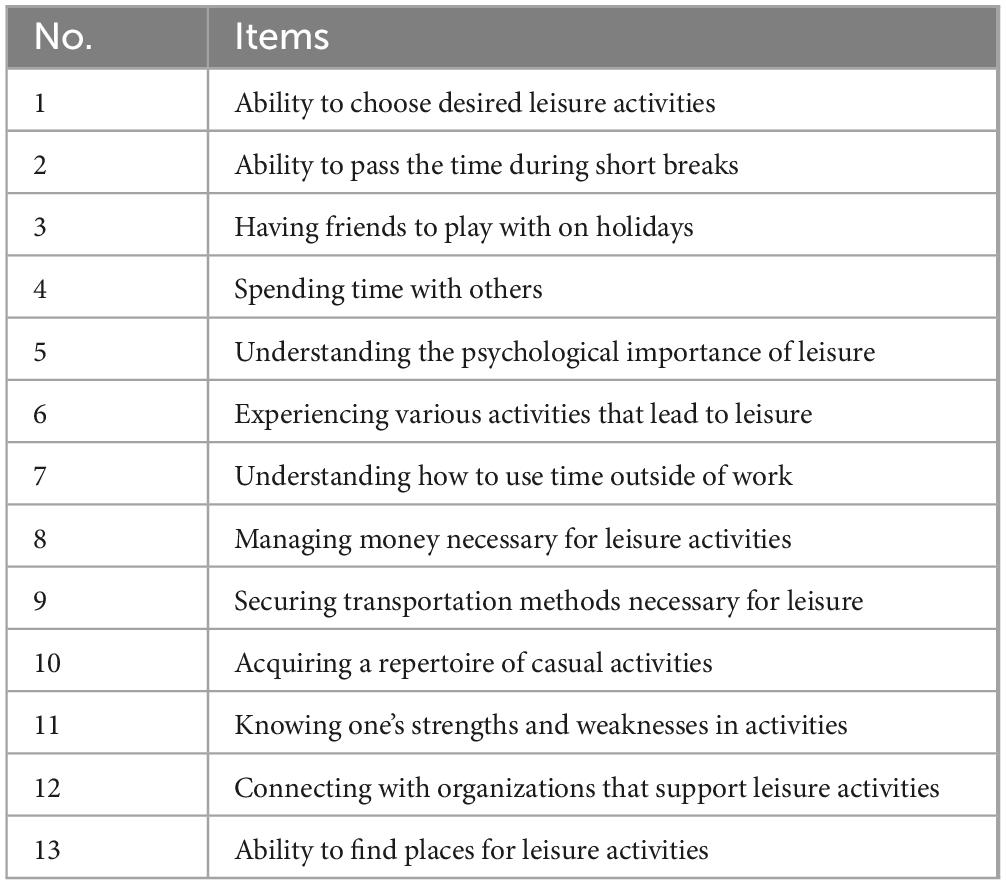

The 13 items related to leisure activity guidance that were investigated in this study are listed in Table 1.

This research derived leisure-related behaviors from guidance content obtained through a literature review on leisure guidance in Japan (Yamada and Maebara, 2023) and a qualitative analysis of interviews with high school teachers in special needs schools for students with intellectual disabilities. Five teachers, with an average of 14 years of teaching experience (ranging from a minimum of 3 years to a maximum of 29 years), participated in 60-min face-to-face interviews. During the interviews, the teachers discussed the content and issues surrounding leisure time education. We categorized these interview data into themes through content analysis based on semantic similarities. The six referenced themes were “abilities necessary for enriching leisure,” “student challenges,” “guidance content,” “challenges in school instruction,” “parent awareness,” and “perceptions of leisure,” which we originally created.

In this study, respondents evaluated the 13 items related to leisure instruction using a five-point scale (unimportant = 1, not very important = 2, undecided = 3, somewhat important = 4 and important = 5) to assess their perceived importance during various stages of school and after graduation. The survey questions for the 13 items were structured in the following two patterns:

During school: To what extent is it important to provide guidance in classes, school situations, etc., during school before graduation?

After graduation: To what extent is it important to provide guidance in social life situations after graduation from school?

2.3.3 Issues in leisure guidance

Participating teachers and practitioners provided free-text responses regarding issues in leisure guidance. The survey form included a section for these responses, allowing respondents to express their thoughts freely on issues and perceptions related to leisure instruction.

2.4 Data analysis

In this study, we performed a simple tabulation of basic information. We evaluated teachers’ recognition of the importance of the items related to leisure activity guidance during schooling using factor analysis. Based on the factors obtained, we calculated the mean scores of the teachers’ and practitioners’ recognition of importance of the leisure activity guidance items during schooling and after graduation. Additionally, we calculated the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient to evaluate the internal consistency of the scores for each factor. The analysis compared differences in scores between special education teachers and vocational rehabilitation practitioners, as well as differences based on instructional content required during school and after graduation. The analysis excluded missing values and treated the remaining data statistically.

A two-way between-subjects analysis of the scores obtained from the factor analysis examined differences in recognition of importance based on participant type (teachers and practitioners) and guidance timing (during schooling and after graduation). The free-text responses regarding issues in leisure guidance underwent qualitative analysis and were categorized based on semantic similarities identified between the teachers and practitioners. We conducted the analysis using content analysis methodology.

This study adopted a mixed methods research design, integrating both the perceptions derived from the quantitative survey of survey items and the meanings extracted from the qualitative survey of open-ended responses. This approach aims to identify in detail the differences in perceptions related to leisure instruction between special education teachers and vocational rehabilitation practitioners.

2.5 Regarding the use of Gen AI

The article was translated into English by DeepL (https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator) and then proofread in English by editage (https://www.editage.jp/).

3 Results

3.1 Basic attributes

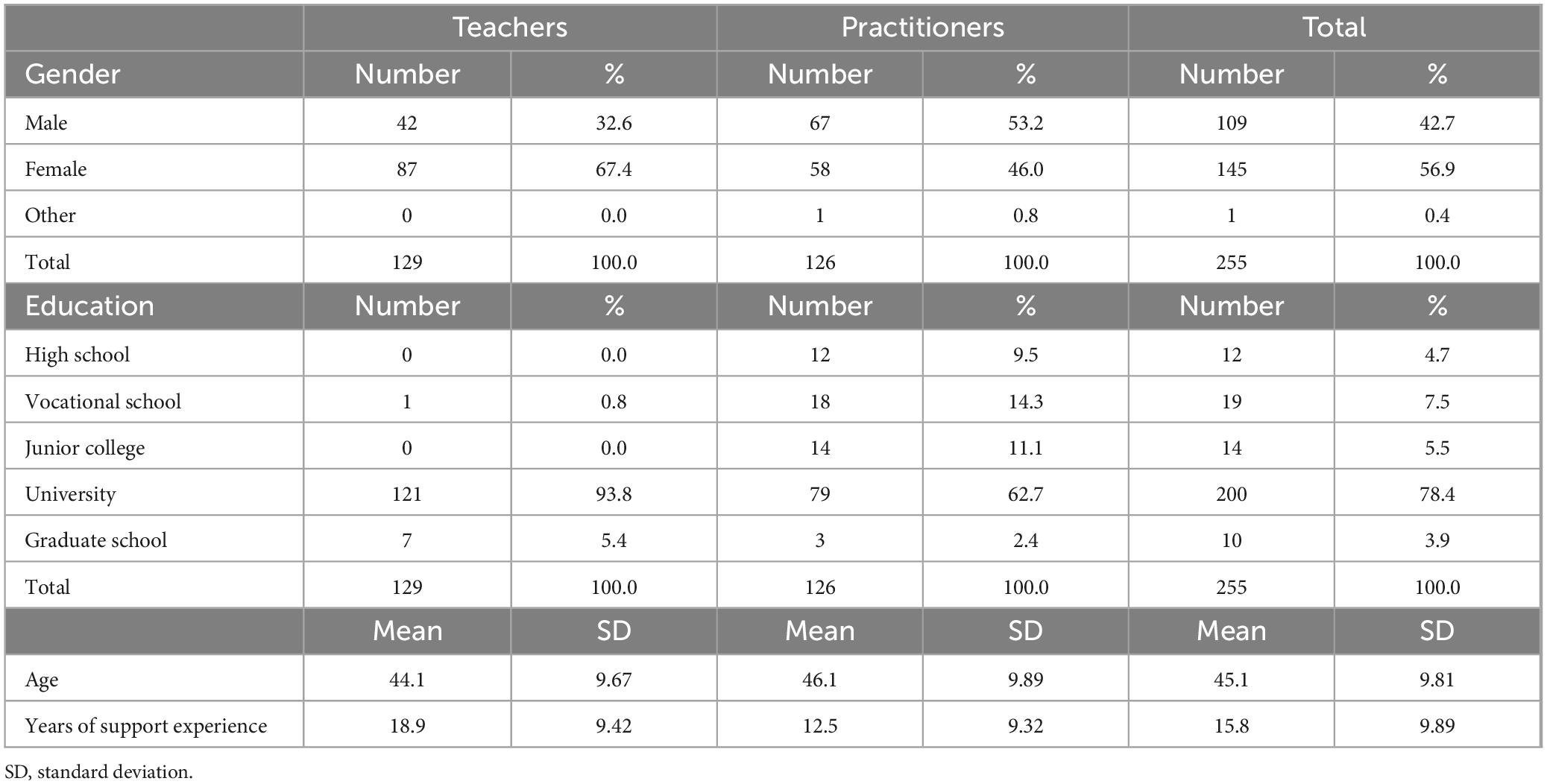

In this study, we obtained responses from 255 participants, consisting of 129 special needs school teachers and 126 vocational rehabilitation practitioners. The basic attributes of the participants are presented in Table 2. Most teachers held university graduates or higher, while approximately 60% of the practitioners were university graduates. The average age of the participants was approximately 45 years, and they averaged 15 years of support experience.

3.2 Factor analysis of items related to leisure activity guidance

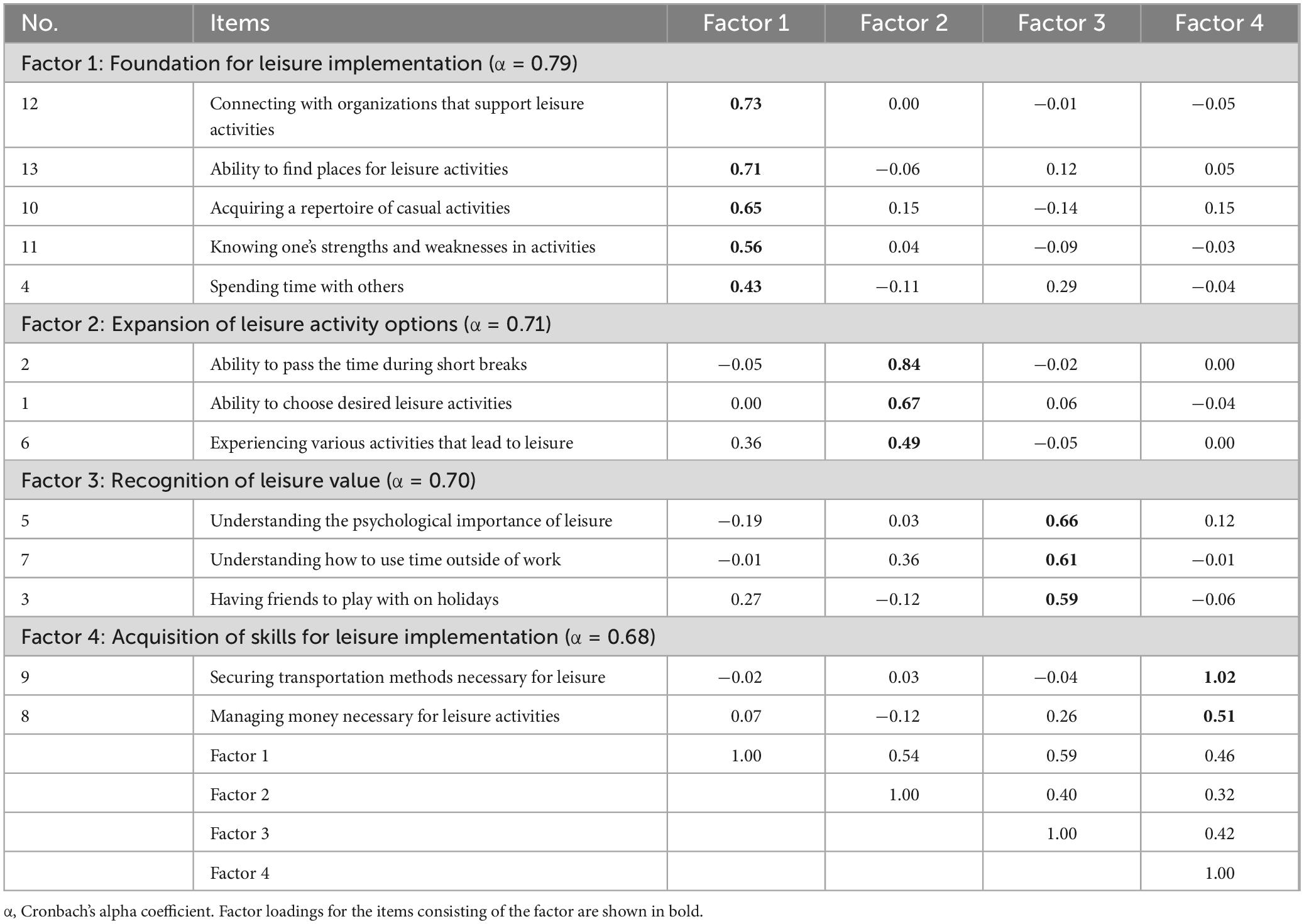

The items related to leisure activity guidance derived from interview surveys with teachers, who provided their perspectives on educational guidance in special needs schools. As this study focused on the nature of leisure guidance provided by teachers, we conducted exploratory factor analysis using maximum likelihood estimation with Promax rotation on the importance ratings that teachers assigned to the items related to leisure guidance during schooling. Based on eigenvalue decay and the interpretability of the factors, we considered a four-factor structure appropriate. The final factor pattern and inter-factor correlations after the rotation are listed in Table 3.

The first factor consisted of the items “connecting with organizations that support leisure activities,” “ability to find places for leisure activities,” “acquiring a repertoire of casual activities,” “knowing one’s strengths and weaknesses in activities,” and “spending time with others.” This factor was named “foundation for leisure implementation.” The second factor consisted of the items “ability to pass the time during short breaks,” “ability to choose desired leisure activities,” and “experiencing various activities that lead to leisure.” This factor was named “expansion of leisure activity options.” The third factor consisted of the items “understanding the psychological importance of leisure,” “understanding how to use time outside of work,” and “having friends to play with on holidays.” This factor was named “recognition of leisure value.” The fourth factor consisted of the items “securing transportation methods necessary for leisure” and “managing money necessary for leisure activities.” This factor was named “acquisition of skills for leisure implementation.”

3.3 Recognition of the importance of leisure activity guidance

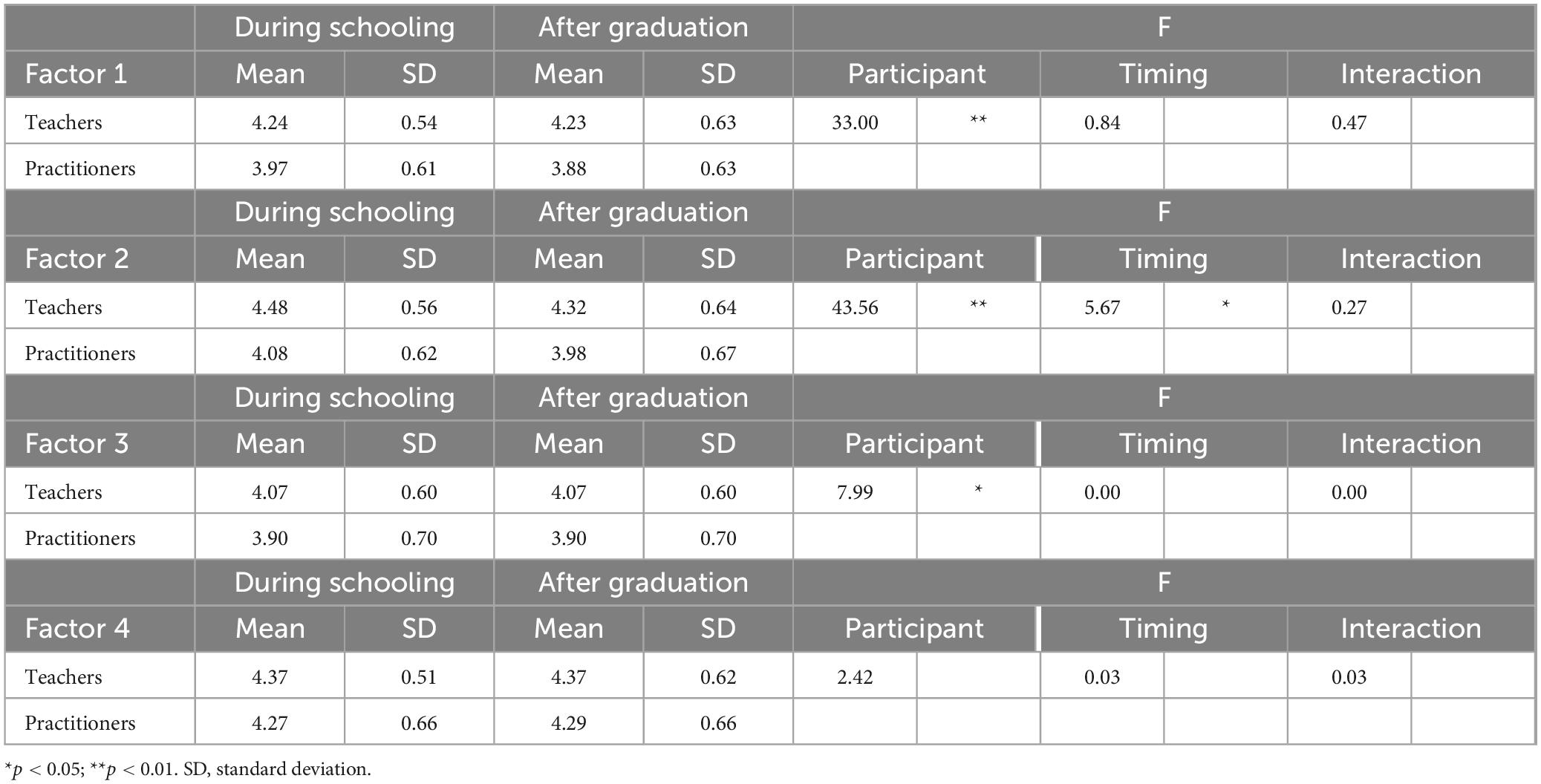

Next, we compared the importance levels of the four factors obtained through the factor analysis in terms of participant type (teachers and practitioners) and guidance timing (during schooling and after graduation) (Table 4).

For Factor 1, “foundation for leisure implementation,” participant type had a main effect [F(1, 506) = 33.00, p < 0.01]. The special needs school teachers recognized the importance of guidance related to this factor more strongly than the vocational rehabilitation practitioners. For Factor 2, “expansion of leisure activity options,” both participant type [F(1, 506) = 43.56, p < 0.01] and guidance timing [F(1, 506) = 5.67, p < 0.05] showed main effects. The special needs school teachers recognized the importance of guidance related to this factor more strongly than the vocational rehabilitation practitioners. Additionally, the guidance related to Factor 2 was perceived as more important during schooling. For Factor 3, “recognition of leisure value,” participant type showed a main effect [F(1, 506) = 7.99, p < 0.05]. The special needs school teachers recognized the importance of guidance related to this factor more strongly than the vocational rehabilitation practitioners. For Factor 4, “acquisition of skills for leisure implementation,” we found no significant differences in any of the comparisons.

3.4 Qualitative analysis of issues in leisure guidance

We conducted a qualitative analysis to evaluate the issues related to leisure guidance as perceived by both groups of participants. The results of the analysis of the teachers’ perceived issues are shown in Table 5. We obtained 40 text responses concerning these issues from the teachers. We then categorized these responses into subcategories based on the similarity of meaning, and further grouped the subcategories into categories. The categorized issues identified are as follows:

The category “expansion of options” comprised 19 text responses. This category encompassed issues such as the need to increase leisure options and opportunities for interaction with people other than family members. It also covered the importance of creating an environment that respects an individual’s leisure needs.

The category “development of social environment” comprised 11 text responses. This category covered issues such as the lack of social resources for leisure and the insufficiency of the transportation means necessary for engaging in leisure activities.

The category “foundation for leisure” comprised 4 text responses. This category covered issues related to maintaining a balance between leisure activities and employment.

The category “skills for leisure implementation” comprised 3 text responses. This category encompassed issues such as the challenges related to managing the finances necessary to engage in leisure activities.

The category “methods of leisure support” comprised 3 text responses. This category addressed issues such as the difficulty in resolving personal problems that arise alongside leisure activities and the challenge of accommodating individual preferences in leisure guidance.

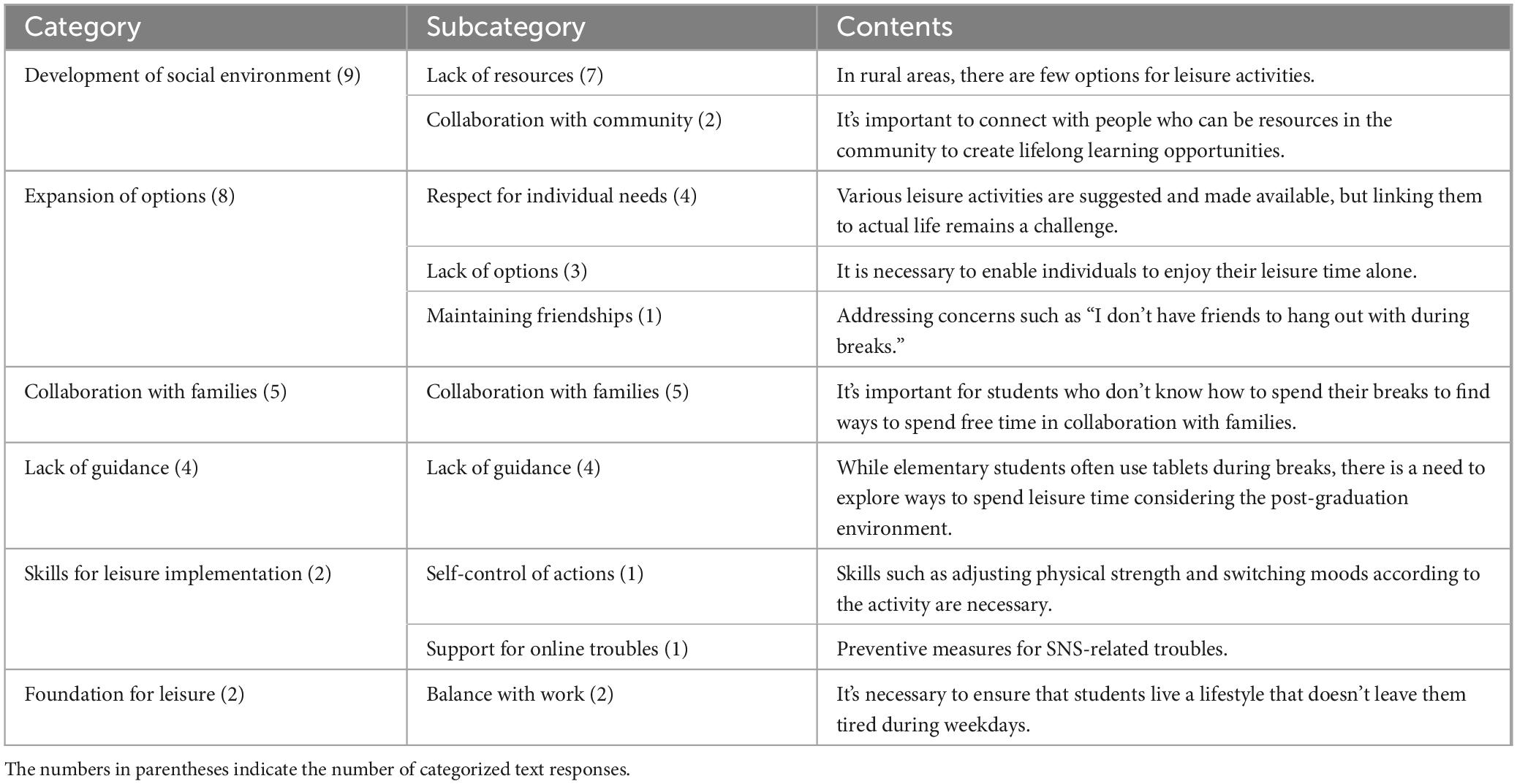

The results of the analysis of the issues in leisure guidance as recognized by practitioners are shown in Table 6. We obtained 30 text responses concerning issues from the practitioners. We then categorized these responses based on the similarity of meaning, and further grouped the subcategories into categories. The categorized issues identified are as follows:

The category “social environment development” comprised 9 text responses. This category covered issues such as the lack of social resources for leisure activities and the need for collaboration with the community to enhance leisure activities.

The category “expansion of options” comprised 8 text responses. This category highlighted the need to increase leisure options similar to those provided by special needs education teachers, the importance of increasing opportunities for interaction with people other than family members, and the need to create an environment that respects individuals’ leisure needs.

The category “collaboration with families” comprised 5 text responses. This emphasizes the necessity for family cooperation in leisure activities.

The category “lack of guidance” comprised 4 text responses. This category highlighted the need for guidance in imagining social life after graduation.

The category “skills for executing leisure activities” comprised 2 text responses. This category covered issues such as the need for self-control guidance to balance leisure activities and employment, which differed from the issue recognized by the special needs education teachers, and the need for guidance to prevent potential internet problems, such as those arising from social networking services.

The category “foundation building for leisure” comprised 2 text responses. This category encompassed issues related to maintaining a balance between leisure activities and employment, which are similar to the challenges recognized by special needs education teachers.

4 Discussion

Leisure activities serve as the fundamental basis for the social participation of people with disabilities after they graduate from special education. Existing literature suggests that creating a conducive environment and acquiring skills for leisure activities promote positive social interactions (Heinlein et al., 1998). It is crucial to identify the content of leisure guidance that vocational rehabilitation practitioners deemed important, as they provide support for social participation after graduation. Subsequently, incorporating these insights into special education is essential for shaping effective educational practices.

This study identified leisure guidance content in special education and clarified the perceptions of special education teachers and vocational rehabilitation practitioners regarding leisure guidance. In addition, we highlighted the challenges associated with providing leisure guidance.

4.1 Perceptions of leisure guidance by special education teachers

Through factor analysis, we categorized the responses of special education teachers regarding the importance of leisure guidance during schooling. The results revealed that the leisure guidance includes establishing a foundation for leisure implementation, expanding leisure activity options, recognizing the value of leisure, and acquiring skills for leisure implementation. This finding has two significant implications.

First, the finding reaffirms the value of leisure guidance in promoting social participation. Viewing leisure merely as a non-directed use of time can be meaningless and may ultimately lead to deteriorating health conditions for people with disabilities (Scanlan et al., 2011). By providing leisure guidance, educators help individuals maintain their health and contribute to their communities (Kvam et al., 2013). The four content areas not only represent soft skills essential for maintaining employment but also life skills beneficial for inclusive living in society. Teaching leisure time is not sufficient only for leisure education by teachers in schools. To achieve this, the community must also be well utilized. This will not only improve the life skills of people with disabilities, but will also lead to development regarding community inclusion.

Second, the finding emphasizes that leisure guidance content extends beyond providing education; it also involves options for leisure activities that lead to potential experiences. Special education teachers report making efforts to expand leisure activity options, including leisure guidance in special education schools (Hatakeyama and Kuno, 2011; Hatakeyama and Kuno, 2012; Hosoya et al., 2017) and implementing educational practices related to leisure activities (Enomoto, 2013; Kishida, 2010; Matsushita and Sonoyama, 2008; Okabe and Watanabe, 2006; Okamoto, 2009; Wada, 2009). The results of our study provide new perspectives on delivering leisure guidance. The data is fundamental in providing a perspective not only on education, but also on vocational rehabilitation and further community development.

4.2 Gap in perceptions between special education and vocational rehabilitation

This study explored the gaps in the perceptions between special education teachers and vocational rehabilitation practitioners. The results indicated that teachers placed more importance on guidance related to establishing a foundation for leisure implementation, expanding leisure activity options, and recognizing the value of leisure compared to practitioners. Furthermore, teachers strongly recognized the importance of providing guidance in expanding leisure activity options during schooling. However, we found no significant gap between the teachers’ and practitioners’ perspectives on acquiring skills for leisure implementation.

The finding that special education teachers perceive guidance as more important reflects the current situation and seems to align with the needs of vocational rehabilitation practitioners who provide post-graduation support. However, the analysis of the challenges in providing leisure guidance suggested that this alignment may be superficial. Essentially, we noted a gap in the perceptions of the teachers and practitioners. Practitioners recognized issues such as a lack of collaboration with families, insufficient guidance on leisure, and the inability to maintain self-control for leisure activities. In some cases, despite participating in leisure activities post-transition from special education to vocational rehabilitation, individuals continue to face social exclusion because of a lack of interaction with peers without disabilities (Dusseljee et al., 2011). Additionally, practitioners noted that a lack of guidance during school years contributes to poor work-life balance (Maebara, 2022). These findings suggest a fundamental misalignment between teachers’ and practitioners’ perspectives on leisure guidance. Recognizing this perceptual gap is crucial for fostering effective communication and collaboration between teachers and practitioners, which leads to better transition support. Although further evidence is considered necessary, the following may be considered Traditionally, the need for leisure education to reflect the views of vocational rehabilitation practitioners, who are responsible for supporting post-social participation, would have been pointed out. However, perhaps it may also be necessary to approach policy in such a way that the perspective of leisure education in schools is communicated to vocational rehabilitation practitioners and the practice of vocational rehabilitation is expanded.

4.3 Limitations of the study

Despite the new discoveries and practical insights from this study, researchers should consider several limitations when interpreting the results. First, we recruited special education teachers and vocational rehabilitation practitioners from rural schools in Japan. Therefore, applying these findings to other cultures or generalizing them to all of Japan poses challenges. Future research should include data from urban areas with more social resources and better access to transportation to provide broader implications. Second, the study highlighted a perceptual difference in the concept of leisure between special education teachers and vocational rehabilitation practitioners. This difference may have contributed to the recognized gap in perceptions. Further exploratory research is needed to understand the fundamental perceptions of leisure. Finally, this study focused on special education teachers and vocational rehabilitation practitioners who support students with disabilities. However, regarding leisure activities, it is essential to consider the preferences and intentions of the students with disabilities themselves, along with the involvement of their families. The perspectives of students with disabilities themselves and their families have not been investigated, indicating a need for future research in this area.

5 Conclusion

This study investigated the perceptions of leisure guidance contributing to transition support by analyzing data from special education teachers and vocational rehabilitation practitioners in Japan. We identified the specific components necessary for leisure guidance and the perceptual gap between teachers and practitioners. The findings of this study provide valuable insights for special education teachers as they offer education aimed at facilitating societal transition.

Transition support, which spans various fields such as special education and vocational rehabilitation, faces challenges owing to its interdisciplinary nature. Our research aims to bridge this gap and contribute to better educational practices for special education teachers. Teachers should hold themselves accountable for their educational practices aimed at transition support and leverage their expertise as professionals. This study aims to promote solutions to practical challenges in providing leisure guidance.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

In conducting this survey, we explained the protection of personal information on the front page of the questionnaire and obtained consent from the participants. Additionally, we obtained approval from the Research Ethics Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects at the Akita University Tegata Campus (Approval No. 5-37, dated 11 October 2023).

Author contributions

KM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. AY: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing – review and editing, Supervision. YY: Investigation, Writing – review and editing, Formal analysis.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the FY2023 Japan Vocational Rehabilitation Society Startup Grant.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants who supported this study. The article was translated into English by DeepL (https://www.deepl.com/en/translator) and then proofread in English by editage (https://www.editage.jp/).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Condon, E., and Callahan, M. (2008). Individualized career planning for students with significant support needs utilizing the discovery and vocational profile process, cross-agency collaborative funding and social security work incentives. J. Vocat. Rehabil. 28, 85–96.

Day, H., and Alon, E. (1993). Work, leisure, and quality of life of vocational rehabilitation consumers. Can. J. Rehabil. 7, 119–125.

Dunn, E. C., Wewiorski, N. J., and Rogers, E. S. (2008). The meaning and importance of employment to people in recovery from serious mental illness: results of a qualitative study. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 32, 59–62. doi: 10.2975/32.1.2008.59.62

Dusseljee, J. C. E., Rijken, P. M., Cardol, M., Curfs, L. M. G., and Groenewegen, P. P. (2011). Participation in daytime activities among people with mild or moderate intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 55, 4–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01342.x

Enomoto, T. (2013). Home-based cooperative behavioral support with mother: support to the behavioral problem by child with pervasive developmental disorders [in Japanese]. Jpn. J. Study Support Syst. Dev. Disabil. 12, 55–63.

Frank, A. (2016). Vocational rehabilitation: supporting ill or disabled individuals in (to) work: a UK perspective. Healthcare 4:46. doi: 10.3390/healthcare4030046

Fujita, M. (2024). Comparative verification on individualized education program in Japan and America [in Japanese]. Bull. Graduate Schl Educ. Waseda Univ. 31, 37–47.

Hall, S. A. (2016). Community involvement of young adults with intellectual disabilities: their experiences and perspectives on inclusion. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 30, 859–871. doi: 10.1111/jar.12276

Hammell, K. W. (2004). Dimensions of meaning in the occupations of daily life. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 71, 296–305. doi: 10.1177/000841740407100509

Hatakeyama, F., and Kuno, T. (2011). A trial of the kids football on Saturday for an attached special support elementary school for children with intellectual disorders (1) [in Japanese]. J. Stud. Educ. Pract. 28, 323–341.

Hatakeyama, F., and Kuno, T. (2012). A trial of the kids football on Saturday for an attached special support elementary school for children with intellectual disorders (2): from a view point of career education [in Japanese]. J. Stud. Educ. Pract. 29, 127–144.

Heinlein, K. B., Campbell, E. M., Fortune, J., Fortune, B., Moore, K. S., and Laird, E. (1998). Hitting the moving target of program choice. Res. Dev. Disabil. 19, 27–38. doi: 10.1016/S0891-4222(97)00027-9

Herrick, S. J., Lu, W., Oursler, J., Beninato, J., Gbadamosi, S., Durante, A., et al. (2022). Soft skills for success for job seekers with autism spectrum disorder. J. Vocat. Rehabil. 57, 113–126. doi: 10.3233/JVR-221203

Hosoya, K., Kitamura, H., Igarashi, Y., Hirohata, K., and Okayama, T. (2017). A study of leisure-time support for children in the during the long vacation: summer school in HAKODATE [in Japanese]. J. Hokkaido Univ. Educ. 67, 77–84. doi: 10.32150/00006513

Imai, A., Maebara, K., and Yaeda, J. (2023). Efforts and effectiveness in improving knowledge and skills of vocational assessment for teachers supporting career decisions of students with intellectual disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabl. Diagn. Treat. 11, 167–175. doi: 10.6000/2292-2598.2023.11.04.1

Institute on Community Integration (n.d.). Institute on Community Integration (ICI). University of Minnesota. Available online at: https://ici.umn.edu/ (accessed November 16, 2024).

Johnson, T. L. (2014). Transition Competencies: Secondary Special Education Teachers’ Perceptions of Their Frequency of Performance [Doctoral Dissertation]. Statesboro, GA: Georgia Southern University.

Kato, K. (2018). “Leisure activity support [in Japanese],” in Developmental Science of Autism Spectrum: Developmental Science Handbook 10, ed. Japan Society of Developmental Psychology, (Tokyo: Shin-yo-sya), 220–229.

Kim, R., and Dymond, S. K. (2010). Special education teachers’ perceptions of benefits, barriers, and components of community-based vocational instruction. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 48, 313–329. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-48.5.313

Kishida, T. (2010). Using “Otona No Nurie” to teach leisure skills to mentally challenged youth and an examination of the influence that an improvement skills has on the subjects and their families [in Japanese]. Bull. Educ. Res. Setsunan Univ. 6, 47–64.

Kvam, L., Eide, A. H., and Vik, K. (2013). Understanding experiences of participation among men and women with chronic musculoskeletal pain in vocational rehabilitation. Work 45, 161–174. doi: 10.3233/WOR-121534

Kvam, L., Vik, K., and Eide, A. H. (2015). Importance of participation in major life areas matters for return to work. J. Occup. Rehabil. 25, 368–377. doi: 10.1007/s10926-014-9545-2

Maebara, K. (2022). Case study on the employment of person with intellectual disability in childcare work in Japan. J. Intellect. Disabl. Diagn. Treat. 10, 122–129. doi: 10.6000/2292-2598.2022.10.03.1

Matsushita, H., and Sonoyama, S. (2008). A case study on the effects of using activity schedules in leisure activities for children with autism [in Japanese]. Jpn. J. Spec. Educ. 46, 253–263. doi: 10.6033/tokkyou.46.253

McCarron, L., Kern, W., and Wolf, C. S. (1979). Use of leisure time activities for work adjustment training. Ment. Retard. 17, 159–160.

Nakao, S., and Murata, K. (2019). Comparative verification on individual education plan in Japan and New York City [in Japanese]. Stud. Educ. 12, 11–20.

Nemoto, M. (2018). “Retention support [in Japanese],” in Keywords for Persons with Disabilities and Employment Support: Vocational Rehabilitation Glossary, ed. Japan Society for Vocational Rehabilitation (Saitama: Yadokari Publishing), 134–135.

Nota, L., and Soresi, S. (2009). Ideas and thoughts of Italian teachers on the professional future of persons with disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 53, 65–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01129.x

Okabe, I., and Watanabe, M. (2006). Instruction for the spontaneous initiation of leisure activities by students with developmental disabilities: through the transformation of recess time in schools for the students with intellectual disabilities [in Japanese]. Jpn. J. Spec. Educ. 44, 229–242. doi: 10.6033/tokkyou.44.229

Okamoto, K. (2009). Support that respects the will of a child with autism with intellectual disabilities who finds it difficult to participate in school life [in Japanese]. Jpn. J. Spec. Educ. 47, 129–138. doi: 10.6033/tokkyou.47.129

Park, E. Y. (2022). Factors affecting labour market transitions, sustained employment and sustained unemployment in individuals with intellectual disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 35, 271–279. doi: 10.1111/jar.12946

Park, J. Y., and Park, E. Y. (2019). Factors affecting the acquisition and retention of employment among individuals with intellectual disabilities. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 67, 188–201. doi: 10.1080/20473869.2019.1633166

Povenmire-Kirk, T. C., Test, D. W., Flowers, C. P., Diegelmann, K. M., Bunch-Crump, K., Kemp-Inman, A., et al. (2018). CIRCLES: building an interagency network for transition planning. J. Vocat. Rehabil. 49, 45–57. doi: 10.3233/JVR-180953

Roessler, R. T. (2002). Improving job tenure outcomes for people with disabilities: the 3M model. Rehabil. Couns. Bull. 45, 207–212. doi: 10.1177/00343552020450040301

Scanlan, J. N., Bundy, A. C., and Matthews, L. R. (2011). Promoting wellbeing in young unemployed adults: the importance of identifying meaningful patterns of time use. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 58, 111–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2010.00879.x

Scheef, A. R., and McKnight-Lizotte, M. (2022). Utilizing vocational rehabilitation to support post-school transition for students with learning disabilities. Interv. Sch. Clin. 57, 316–321. doi: 10.1177/10534512211032604

Smith, K. M. (2016). Investigating Transition Process for Students with Special Needs [Masters Thesis]. Fort Wayne, IN: Indiana University-Purdue University Fort Wayne.

Snell-Rood, C., Ruble, L., Kleinert, H., McGrew, J. H., Adams, M., Rodgers, A., et al. (2020). Stakeholder perspectives on transition planning, implementation, and outcomes for students with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 24, 1164–1176. doi: 10.1177/1362361319894827

Strong, S. (1998). Meaningful work in supportive environments: experiences with the recovery process. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 52, 31–38. doi: 10.5014/ajot.52.1.31

Taylor, D. L., Morgan, R. L., and Callow-Heusser, C. A. (2016). A survey of vocational rehabilitation counselors and special education teachers on collaboration in transition planning. J. Vocat. Rehabil. 44, 163–173. doi: 10.3233/JVR-150788

Thomas, F., and Morgan, R. L. (2021). Evidence-based job retention interventions for people with disabilities: a narrative literature review. J. Vocat. Rehabil. 54, 89–101. doi: 10.3233/JVR-201122

Trombly, C. A. (1995). Occupation: purposefulness and meaningfulness as therapeutic mechanisms. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 49, 960–972. doi: 10.5014/ajot.49.10.960

Tsuzuki, S. (2008). Consideration on administration policy for the disabled in the U.S.A. [in Japanese]. Bull. Aichi Univ. Educ. Educ. Sci. 57, 17–27.

Wada, S. (2009). Support for A with mental and right hand handicap to play an instrument: a case study of playing the single hand ocarina [in Japanese]. Bull. Kansai Soc. Musicol. 26, 1–20.

Wehman, P. (1977). Research on leisure time and the severely developmentally disabled. Rehabil. Lit. 38, 98–105.

Wehman, P., Sima, A. P., Ketchum, J., West, M. D., Chan, F., and Luecking, R. (2015). Predictors of successful transition from school to employment for youth with disabilities. J. Occup. Rehabil. 25, 323–334. doi: 10.1007/s10926-014-9541-6

Yamada, Y., and Maebara, K. (2023). A literature review on leisure education for persons with intellectual disabilities: focusing on leisure education practices [in Japanese]. Mem. Fac. Educ. Hum. Stud. Akita Univ. Educ. Sci. 78, 97–103. doi: 10.20569/00006350

2Yasukawa, N., and Kobayashi, S. (2004). Practice of leisure guidance for children with autism: guidance on “going swimming alone” through individual education plans [in Japanese]. Jpn. J. Spec. Educ. 42, 123–132. doi: 10.6033/tokkyou.42.123

Yin, M., and Jodl, J. (n.d.). Social Inclusion of Students with Intellectual Disabilities: Global Evidence from Special Olympics Unified Schools. Available online at: https://resources.specialolympics.org/community-building/youth-and-school/unified-champion-schools/social-inclusion-of-students-with-intellectual-disabilities-global-evidence-from-special-olympics-unified-schools#endnotes (accessed November 16, 2024).

Keywords: leisure activities, employment continuation, vocational rehabilitation, special needs education, transition support

Citation: Maebara K, Yamaguchi A and Yamada Y (2024) Content of leisure activity guidance recognized as necessary in special needs education. Front. Educ. 9:1477102. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1477102

Received: 07 August 2024; Accepted: 28 November 2024;

Published: 11 December 2024.

Edited by:

Gloria K. Lee, Michigan State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Mikhail Karganov, Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, RussiaRosa Santamaria, University of Burgos, Spain

Renata Ticha, University of Minnesota Twin Cities, United States

Copyright © 2024 Maebara, Yamaguchi and Yamada. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kazuaki Maebara, bWFlYmFyYS1rYXp1YWtpQGVkLmFraXRhLXUuYWMuanA=

Kazuaki Maebara

Kazuaki Maebara Asuka Yamaguchi2

Asuka Yamaguchi2