- Institute of Special Education, University of Debrecen, Hajdúböszörmény, Hungary

The present paper deals with the issues of teaching a second language to school-aged children in Hungary with mild intellectual disabilities. The frameworks for language teaching are described in the National Core Curriculum and the Frame Curriculum. In our research we conducted semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions featuring 11 language teachers, and asked for their experience in teaching a second language to children with mild intellectual disabilities. Moreover, our research involves a focus group discussion in spring 2023 featuring 8 children in Grade 7 with mild intellectual disabilities. We came to the conclusion that teachers pay attention to individual development and playful, communicative language teaching, even though it is challenging to teach English to children with such disabilities, as they often have difficulties in their mother tongue. The research has revealed there is a need for teachers to display creativity because these children require a lot of revision. The children asked do not encounter English at home and only a few of them listen to music in English. However, they all think learning English is important for their future, especially in the areas of work and travel. Our experience underlines that it is beneficial for learners with mild intellectual disabilities to get to know a foreign language, even though they will not be independent users of the language and might not use this knowledge in the future.

1 Introduction

Nowadays, thanks to the acceleration of technological progress and the constant flow of information from many directions, a basic knowledge of at least one foreign language is essential. This is why foreign language teaching in schools has become a priority worldwide, and why it must be made available to all, in the framework of equal opportunities. English is not only the lingua franca but is also the modern means to communicate, opening up job and career opportunities.

Teaching English is now inclusive in nature, which means everyone is involved and nobody is left behind. In addition to education, it is also vitally important that students learn the content effectively so that they can apply it in the future.

The European Commission has made foreign language education a priority and has made a commitment to foreign language teaching for children with disabilities. It believes that all children, regardless of the type of educational institution which they attend, have the right to learn a foreign language (European Commission, 2005). This field is really new in language pedagogy and, due to the students’ different abilities, an accepted, overarching methodology has yet to be developed (Coşkun, 2013; Pokrivčáková, 2015). However, not every strategy works with pupils with mild intellectual disabilities (MID), which is the main emphasis of this research. Due to the particular characteristics of pupils with MID, they are not as effective in learning as their peers in mainstream schools. In England, pupils aged 11–14 with MID have had the opportunity to learn a modern foreign language for over 20 years (Wilson, 2014 as cited in Meggyesné Hosszu, 2019). Nemes and Rózsa (2021) provides information about teaching German to students with MID within the Hungarian system and in an international context. The research involves an overview of several European countries (Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Romania, Poland, Russia, Estonia, and Italy). The authors contacted specific institutions in those countries and asked for their experiences of teaching a second language to children with MID. Also, English lessons are mandatory in the curriculum of Indonesian children with MID (Lestari et al., 2022).

The present paper deals with the issues of teaching a second language to school-aged children with MID, focusing on Hungary. Since Hungary’s accession to the European Union in 2004, foreign language teaching has assumed a prominent role in education. Aligning with the European Commission’s 2005 declaration of every child’s right to language learning, the European Union identified key competences, including foreign languages, as essential for the 21st century. The overarching aim of foreign language instruction is to equip children with age-appropriate and practical language skills. Act CXC of 2011 on Public Education mandates twice-weekly foreign language lessons for students with learning difficulties, commencing in Grade 7. English as a Foreign Language (EFL) generally means teaching English to non-native speakers in an environment where English is not the primary language. Teaching English involves the 4 basic language skills: speaking, listening, reading and writing. As for teaching English, there have been new and innovative methods and approaches to enhance overall language competence among students. Meggyesné Hosszu (2019) defines foreign languages as those not central to learners’ immediate lives but taught in guided settings such as schools.

In Hungary, based on the European Commission’s recommendation, from the 2015/2016 school year foreign language teaching has been compulsory for children with MID in segregated schools from the seventh grade onwards for 2 hours per week (144 h per year) (Meggyesné Hosszu, 2015). The segregated schools have been designed for learners with MID. Special Educators teach in the classes of which the size is small (maximum 10 children) to provide individual attention to each learners. The teaching process is usually supported by the help of a Teacher Assistant. Since the subject “Foreign Language” is not performance-oriented, the appropriate stress-free learning environment plays an important role in the success of language learning. For this purpose, visual reinforcement/support, repetition, breaking down the learning material into small parts and continuous praise and reward are important working methods.

The current research aims to explore the experience of Hungarian teachers concerning compulsory language teaching for children with MID. However, there has been no consensus among professionals, parents and language teachers on the teaching of languages to learners with MID.

Some stakeholders (local authorities, language teachers, Special Educators) express concerns that language learning may pose an unnecessary burden for students with MID, as their first language (L1) skills are limited and foreign language lessons are not necessary. Students quickly forget what they have learned in class, so there is little measurable progress, their vocabulary and grammar do not expand, and students do not become independent language users or real conversational partners. Others argue that success can also be achieved with this population. Some learners will be able to communicate at a basic level (A1), using simple language tools to make themselves understood on familiar topics. For learners with MID, the aim is not to pass language and school-leaving exams, but to build up a basic everyday vocabulary, to raise interest in the target language and to develop and maintain a positive attitude towards language learning (Meggyesné Hosszu, 2018a,b).

2 The threads in my head are tangled – characteristics of pupils with learning disabilities

In Hungary, the assessment of Special Educational Needs adheres to a multi-level expert examination process as mandated by Act CXC of 2011 on Public Education.1 The assessment of Special Educational Needs (SEN) necessitates a comprehensive evaluation conducted by a multidisciplinary team comprising medical professionals, psychologists, and educators. Students identified as having SEN are legally entitled to additional rights and support within public educational institutions. The legislation defines SEN broadly, encompassing a range of disabilities, including motor, sensory (visual and auditory), intellectual, speech, cumulative disabilities, autism spectrum disorder, and other mental development disorders such as severe learning, attention, or behavioral difficulties. This process incorporates a mechanism for parental appeal and potential referral to specialized services if disagreements arise concerning the diagnosis or procedural aspects. In the case of intellectual disability, the assessment unfolds at both the county and national levels. While parental cooperation is integral throughout the procedure, parents retain the right of appeal to the local Government Office should they disagree with the expert opinion or any procedural elements. Upon such an appeal, the assessment may be repeated, or the case may be referred to the ELTE National Pedagogical Service for further evaluation and adjudication.

According to the following important definition by Mesterházi (1997): “The group of children defined as educationally challenged includes those whose reduced functionality can be traced back to biological and/or genetic deficiencies in their nervous systems, or to the impact of environmental disadvantages leading to ongoing and persistent learning difficulties, expressed through inconsistent abilities in the processing and application of skills.” It is important to note that the Hungarian term “tanulásban akadályozott” (educationally challenged) is the equivalent of “mild educational disabilities”, as used in an international context. It is believed that 3–6% of the school-ages population in Hungary falls into the category of “tanulásban akadályozott” (educationally challenged).

A diagnosis of intellectual disability requires the existence of significant limitations in the areas of intellectual functioning and in adaptive behaviour (conceptual, social, practical adaptive skills) and a verification that the disability started in the early years, during the developmental period. The severity is classified as mild (with IQ range of 55 to 69), moderate (IQ range of 35 to 51), severe (IQ range of 20 to 35) and profound (IQ range 20) based on several indicators of functioning and clinical judgement. There are several characteristics of intellectual disability which affect learners’ academic and non-academic lives. For children with MID, it takes longer to learn to talk, but communicate well once they know how. It has an impact on the child’s ability to communicate at school and outside the classroom. A deficit in language skills can be seen as a characteristic that distinguishes children with intellectual disabilities (Lestari et al., 2022). According to the American Psychiatric Association, DSM-5 Task Force (2013), for children with MID, it can be seen that the social domains in the form of communication, conversation, and language are not in accordance with their actual age and there are difficulties in abstract thinking skills. They have memory and attention problems due to the delayed intellectual development. As for self-regulation, they may have symptoms such as self-harming behaviour, aggression and difficulty with sleep. Also, children find it difficult to control their emotions, which may cause problems in the classroom. However, they can be fully independent in self-care and home activities when they get older, though they show social immaturity. In later life, they experience increased difficulty with the responsibilities of marriage or parenting. People with MID are able to learn simple skills and enter the world of work where they usually get unskilled jobs. Their participation in education is highly important because if they get a job, they can become independent adults and can live without depending on others.

However, education must be based on their individual abilities and characteristics in order to develop. It is vital to develop language and social skills to be able to carry out social interactions, have self-confidence to interact and express opinions in their everyday lives. The learning process itself is impacted across multiple dimensions: perception, executive functions, and emotional well-being. Learners with MID have problems with reading and writing affecting academic achievements. Perceptual disturbances can affect visual, auditory, tactile-kinesthetic, and balance perception, as well as memory functions. Difficulties in shape-background discrimination, shape and space perception, tactile sensitivities (either heightened or diminished), and balance are common. Memory impairments may affect attention, working memory, and long-term recall. Executive function challenges are manifest in muscle weakness or stiffness, hindering both fine and gross motor skills. Additionally, emotional and social factors, such as shyness, anxiety, hyperactivity, lack of self-confidence and motivation, further impede the learning process (Czibere and Kisvári, 2006). Low learning motivation can be in connection with past experiences of failure and anxiety (Shree and Shukla, 2016). As a result, such children pay less attention during the learning and teaching activities.

3 The introduction of foreign language teaching for pupils with MID in Hungary

3.1 The principles of language teaching in the National curricula and the framework curricula

The National Core Curriculum (NAT)2 in Hungary serves as the foundational document governing the educational process, outlining the knowledge, skills, abilities, and objectives to be attained in various subjects. The National Core Curriculum forms the basis for the Framework Curriculum3, which acts as an intermediary between the National Core Curriculum and local curricula. The National Core Curriculum and Framework Curriculum establish the principles for teaching foreign languages to students with Special Educational Needs (SEN). Foreign language learning is mandatory from the seventh grade in segregated schools but can commence earlier for interested students, though participation cannot be enforced. The overarching goal is to tailor language learning to individual needs, reinforcing existing skills and fostering self-awareness and confidence. The Framework Curriculum emphasizes practical communication through playful, action-based learning activities such as dialogues, role-plays, and movement exercises. It prioritizes listening comprehension and speaking skills, building upon first language (L1) competence. The focus is on everyday topics and situations, utilizing simple vocabulary and structures.

The curriculum recommends developing auditory perception, speaking skills, attention, and verbal memory. This involves repetition and practice, leading to understanding and responding to simple questions in open dialogues. Reading and writing are less emphasized, and grammar is taught implicitly through contextualized usage rather than explicit rules. Hungarian language support is permitted throughout the teaching-learning process.

Group and cooperative learning activities are encouraged to enhance social competence alongside knowledge and intellectual skills. The primary aim is to facilitate the automatic use of essential vocabulary through engaging activities like movement and sorting tasks, word cards, and games. Assessment focuses on students’ willingness and motivation to communicate.

The curriculum does not prescribe specific language levels or output requirements, allowing for individualized pacing and adaptation to diverse learning abilities. It recommends six core thematic areas: human relations, family and social environment, the target country, the natural environment, shopping, and a healthy lifestyle.

Student motivation is influenced by various factors, including family environment, attitudes towards education, socio-economic status, school resources, and teacher qualities. Teachers play a crucial role in stimulating interest and providing a sense of achievement through differentiation and engaging activities. Additionally, learning about the target language culture and fostering intercultural competence contribute to motivation and overall language development.

Foreign language lessons can complement other subjects by providing opportunities for cross-curricular integration and expanding students’ knowledge in various domains. The use of technology, such as interactive whiteboards, tablets, and smartphones, further enriches the learning experience and promotes engagement.

3.2 The issue of which language to teach

In Hungary during the 1990s, Western languages, particularly English and German, gained prominence. Data from the Central Statistical Office (KSH) indicates English as the most studied foreign language across all school types, while German’s popularity has declined.4 The framework curriculum for students with mild intellectual disabilities does not stipulate a specific language, granting institutions autonomy in selecting among English, German, or Romani, contingent upon the availability of qualified staff.

English enjoys widespread appeal among young people due to its prevalence in popular culture, international communication, and the online sphere. Its vocabulary frequently infiltrates everyday language and appears in online platforms (e.g., play, join, error, accept, volume, download, power, leave, (dis)connect, close), brand names (e.g., Nivea Men, Magnum Almond), and even food or other packaging (e.g., salted, pepper, shampoo, body milk, shower gel, cream, invisible, strong, body, hair, face).

German, on the other hand, offers advantages such as easier letter-sound correspondence (e.g., Mutter, Kind, Vase), pronunciation-aligned spelling, and a phoneme system similar to Hungarian. Additionally, shared cultural elements and the presence of German companies (e.g., BMW, Einhell) in Hungary contribute to its relevance. However, challenges for learners include complex sentence structures, intricate grammar, and word order differences from Hungarian.

A Hungarian study on foreign language motivation among eighth-graders in mainstream schools revealed a preference for English as the first foreign language, driven by its use in music, social media, entertainment, and video games (Nikolov, 2011). Nevertheless, the question remains as to which foreign language best suits the specific needs of learners with MID.

3.3 The issue of learning materials for pupils with learning disabilities

English lessons are provided for children with MID is many countries. However, based on the cognitive characteristics, the material is different from children at the same age attending mainstream schools (also Nemes and Rózsa, 2021). In Indonesia, for students with MID in senior high school, the teaching and learning material is equivalent to 6th grade elementary school English material. The adaptation of the material to the students’ needs and abilities is crucial. Furthermore, to promote academic achievement providing appropriate, sensory, hands-on experience is essential. Based on their observations, field notes and interviews, Lestari et al. (2022) states that children with MID in Indonesia are taught simple English nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs in daily use. Children are trained to combine 2–3 words to form sentences, take turns in a conversation and respond appropriately to simple questions. However, sometimes they face difficulty finding the English word they want to say.

Meggyesné Hosszu (2015) research in Hungary identified a prevalent use of self-created materials in language instruction for learners with MID, attributed to the scarcity of textbooks catering to their specific needs. However, a significant advancement was realized between 2018 and 2021 with the publication of the “Let us do it” foreign language textbook series, designed for grades 7–12 (e.g., Meggyesné Hosszu, 2018a,b; Sári, 2019). This comprehensive series encompasses textbooks, audio materials, workbooks, syllabi, and methodological manuals, all readily accessible online. An accompanying online smart book with interactive exercises further enriches the learning experience.5 The series comprehensively addresses the topics outlined in the framework curriculum, adopting a competence-based pedagogical approach that acknowledges the unique cognitive characteristics of the target student population. The “Let us do it” series incorporates age-appropriate illustrations, photographs, diagrams, maps, word and picture cards, and a sticker booklet to enhance engagement and facilitate learning. While the “Let us do it” series effectively addresses the demand for English language materials, there remains a notable gap in the availability of comparable high-quality, engaging, and accessible resources for German language instruction for adolescent learners with learning difficulties.

3.4 The issue of the teacher

Ideally, a teacher must have teaching qualifications that match the subject being taught as well as appropriate knowledge about children with Special Needs. In Indonesia the Decree of Minister of National Education Number 16 (2007) declared that teachers need to have a BA degree in English Language Teaching in order to teach in a school. However, when working with children with SEN, communication is an essential skill in terms of academic performance, psychological and physical development of the students (Sab’na et al., 2024). Moreover, strategies used in the classroom are very important. However, many teachers do not pay attention to the conditions of the learners. The authors underline that teachers who teach English to children with SEN need various and relevant training to know how to handle challenges during the teaching process.

In Hungary, the provision of this specialized instruction can be undertaken by either Special Educational Needs (SEN) teachers possessing advanced language certifications (C1 level) or language teachers, preferably with additional SEN qualifications to address the unique learning needs of this population. Language teachers must adapt their pedagogical approaches, prioritizing oral communication and positive reinforcement while minimizing reliance on written language instruction.

A pilot study in 2014 conducted by Meggyesné et al. revealed a discrepancy between the legal requirements for teacher qualifications and the actual qualifications of those providing foreign language instruction to students with learning difficulties (UNICEF, 2000). Of the 17 respondents, only five met the stipulated qualifications, highlighting a potential area for improvement in teacher training and professional development to ensure compliance with educational standards (Meggyesné Hosszu and Lesznyák, 2017).

4 Research methodology

The aim of this research study was to investigate the conditions under which students with MID acquire foreign language skills, as well as the teaching methods and tools employed in educational settings. We had the following research questions:

What specific, practical tasks work in the language lessons of MID learners?

What seems to retain and how to test MID learners’ language competence in class?

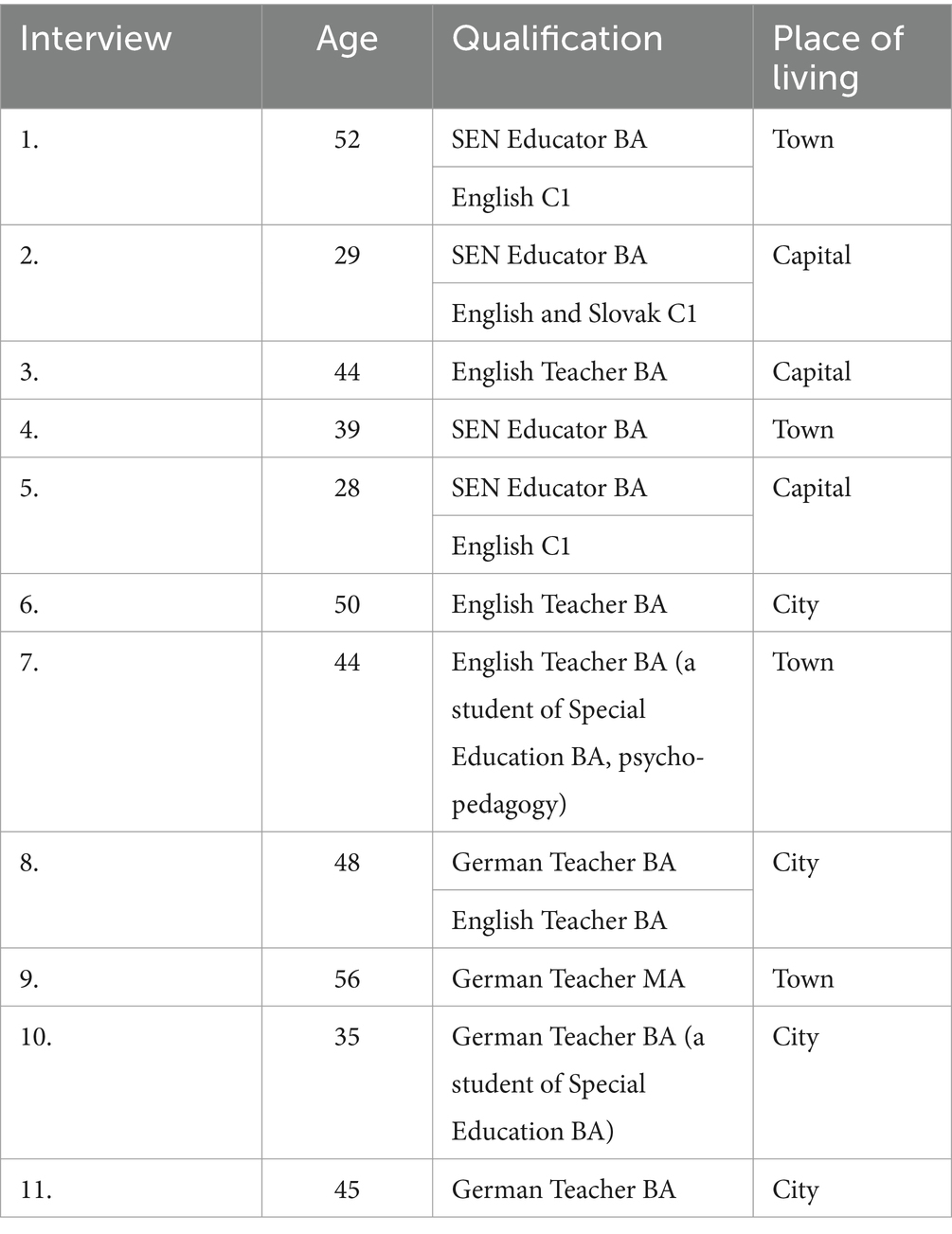

To achieve this aim, semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted with eleven SEN teachers and language teachers who instruct foreign languages to this specific student population. The eleven interviewed teachers represented a range of ages and geographical locations. Two teachers were between 20 and 30 years old, two between 30 and 40, five between 40 and 50, and two over 50. Regarding location, three resided in the capital city, four in other cities, and four in smaller towns. In terms of qualifications, four held degrees in special needs education, three of whom possessed C1-level foreign language certifications. The remaining four were language teachers, with one currently pursuing additional studies in special education specializing in MID and psycho-pedagogy (Table 1).

Data collection took place between January and March 2022, utilizing both online platforms (e.g., Google Meet, Facebook Messenger) and in-person meetings (face-to face interviews were conducted, usually in a school). A set of 25 questions, with minor variations as needed, guided the interviews. The first topics of the interview were qualifications and teaching experiences, teaching methods, strategies and dimensions of teaching. The researcher prepared the questions for the interview based on the specific information the researcher wanted to know: the challenges and solutions that occur during the English teaching process of children with learning disabilities. Researchers guided interviewees in the process whenever they strayed from the main topic and enquiries were made to enrich the data. To analyze the data, the researcher used the six-step thematic analysis of Braun and Clarke (2006): familiarizing with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining themes, writing the report. As the first step, we have read the transcript of the interviews and then coded them manually (e.g., learning games; retaining new material). Later on, we organised the codes into themes (e.g., traditional games, online games; spelling, listening, pronunciation, motivation; course material). After that we did some fine-tuning such as vocabulary based games, tactile games; influence of L1, classroom management. Later on, we did some more coding and refined our codes with the help of mindmaps looking for interesting and meaningful information. Finally, we started working on the text itself embedding vivid examples from the interviews.

A qualitative approach was considered to be useful to achieve the objectives of the study as it helps to explore data in-depth, analyze emerging phenomena and find meaningful values by understanding variables that arise in the process of research activities. When writing about our results, we have decided to add extracts from the interviews to illustrate the analytic claims.

In order to give a more complex picture about teaching English to MID learners, we carried out interviews in a focus group discussion in 2023 with 8 seventh-grade students, aged 13–15 in a segregated primary school in Eastern Hungary. We strongly believe the learners’ perspectives and attitudes provide important information about the learning process. In this particular case, we also had a research question:

According to the children, what is the practical usefulness of learning a foreign language?

When analyzing the transcript of the focus group interviews, we used the same flexible method that has been described earlier (codes, themes, and definitions).

The research adhered to ethical guidelines, with participants fully informed about the purpose of the study and their rights as participants. Before doing our research with underaged children, we asked and received parental consents as well as the approval from the head teacher of the school.

5 Results

5.1 Start and focus of foreign language instruction

While the 2011 National Act CXC mandates foreign language instruction for students with MID from the seventh grade onwards, this research explored the possibility of earlier initiation. Findings indicated that in integrated settings, nearly all students began foreign language learning before the legally required age, often as early as first or third grade. However, in segregated institutions, adherence to the legal mandate was the norm, with limited exceptions for students with autism or psychiatric developmental disorders. Barriers to earlier language instruction in segregated settings included insufficient teacher availability and lack of student interest.

Regarding the prioritization of language skills, all teachers emphasized the importance of developing communication skills and fostering the confidence to speak the foreign language. Listening comprehension was also highlighted, while reading and writing were generally viewed as secondary, reinforcing the primary oral skills. Some teachers emphasized vocabulary development and the role of language learning in enhancing cognitive skills like attention, memory, and logic.

5.2 Methods used for language teaching

The investigation into teachers’ approaches to introducing new content and transferring knowledge revealed a consistent emphasis on reviewing previously learned material before introducing new concepts. Vocabulary acquisition involves learning and storing words, including their meanings and usage in different context. Indonesian research also revealed the importance of repetition to ensure all students understand the material. The teacher involved in the research project used the drill method for repetition. Moreover, she mentioned the grill method which means repeating several times the most frequently used words such as the days of the week, greetings and numbers, either orally or in writing in every class (Sab’na et al., 2024; Bawa and Osei, 2018). Learning English vocabulary can be challenging for every learner. Some learners in Hungarian mainstream and segregated schools also have a vocabulary notebook where they write the new words in every class.

Furthermore, a near-unanimous preference for utilizing visual aids, playful exercises, and objects (e.g., word cards, realia, flashcards) emerged as a strategy to engage students and facilitate comprehension. According to Irfan et al. (2021), tangible, real objects or artifacts, serve as a bridge between abstract language concepts and everyday items, making the learning experience more engaging and effective for young learners (cited in Cando Yánez et al., 2024: p. 93). However, realia can be employed to teach vocabulary to learners with MID too. The Indonesian teacher participating in the research used fun methods to attract students’ attention and tried to connect the material to the students’ lives (Sab’na et al., 2024).

Many foreign language teachers use the Total Physical Response (TPR) method, e.g., in Ecuador (Cando Yánez et al., 2024) and in Hungary too. Total Physical Response (TPR) is a method or strategy which uses the connection between brain and muscle memory, combines physical movement with language acquisition. Also, the combination of TPR and using realia’s is beneficial as real-like objects enhance the learning process and provide better understanding. However, realia can take up too much space in the classroom, can be expensive and may get damaged over time.

Online resources such as videos and games were also incorporated into instruction in Hungary and Indonesia (Sab’na et al., 2024).

One Hungarian participant highlighted the importance of engaging multiple sensory modalities and experiences concurrently, stating, “It is very important to “attack” through as many sensory channels as possible, preferably at the same time! Let the child see, hear, say, and move throughout the entire lesson, if possible, in addition to writing it down” (Interview 7). It is interesting to note, that the four teachers involved in a research project in Ghana had knowledge about multiple intelligence theory, though did not use it due to the lack of resources and time (Bawa and Osei, 2018).

Another Hungarian teacher emphasized that methodological choices should be tailored to individual learners’ needs, often drawing insights from colleagues who teach core subjects to ascertain effective learning strategies. This teacher specifically highlighted the efficacy of the MIM-MEM (Mimicry-Memorization) method (Interview 9). The MIM-MEM method, originally developed for language acquisition by soldiers during World War II, involves mimicking and memorizing phrases and sentences in the target language (Tulus and Rihanatul, 2021). The teacher provides a model, and students practice through repetition, initially in small groups or pairs to minimize errors (Ahyatul, 2021). The method focuses on oral communication, emphasizing listening comprehension, speaking skills, and memorization. Grammar instruction is embedded within pre-selected example sentences, and activities often involve discussion or dramatization.

5.3 Motivating learners

When questioned about strategies and tools for motivating students with MID in foreign language learning situations, teachers frequently cited the use of information and communication technology (ICT) tools and online games and exercises. Specific platforms mentioned included Kahoot, Wordwall, Quizlet, PurposeGames, and LearningApps. One participant emphasized that Kahoot games were an indispensable component of every lesson (Interview 2), while another highlighted the effectiveness of online memory games across age groups (Interview 5). Students with MID tend to forget easily the previous material due to their low concentration and memory span as a result they need a lot of repetition in varied forms. Activities involving the use of realia can be fun and engaging resulting in a more positive learning environment and reduced anxiety level (Cando Yánez et al., 2024). Videos embedded within the curriculum were also noted as motivational tools (Interview 6).

Beyond digital resources, teachers identified several non-technological motivators. In one classroom, earning a top grade through the accumulation of points was found to be effective (Interview 1). Positive feedback, praise, and the sharing of experiences were also cited as key factors. One teacher elaborated, stating, “They do not care about marks. [Motivation comes] with praise, with immediate feedback. Little sweets if you are very clever. With giving an experience. If something is going well, they go down to the canteen and cook” (Interview 4).

5.4 Games and toys in the language classroom

Teachers employed a variety of games and toys to enhance student engagement and learning. These ranged from traditional activities like crossword puzzles, word searches and quizzes, to digital platforms like Baamboozle, an online platform offering a range of customizable games for language learning. Teachers also designed unique vocabulary-based activities, such as letter-search exercises, and incorporated movement through games like “pacing” and “Simon says”.

Tactile learning was facilitated through activities involving objects hidden in a bag, which students had to identify through touch. The use of sensory experiences, realia and instructional materials is crucial as they help to attract and sustain pupils’ attention and facilitate their active participation in the class (Cando Yánez et al., 2024). Children with MID may have attention deficit disorder, hyperactivity, mood swings or temper tantrums (American Psychiatric Association, DSM-5 Task Force, 2013) which are reflected in low attention span, an inability to sit still and unpredictable outbursts during the class. To sum up, teachers have to deal with mental and/or emotional challenges as well during their English lessons. Nonetheless, interesting, engaging and appealing teaching materials may ease the situation for both parties.

Some teachers tailored games to students’ specific interests, such as using pictures of Roma musicians to introduce new vocabulary. Memory games, BINGO, LOTTO, pairing games, true/false games, torpedo, solo dancing, object identification, ball throwing, and role-playing were also commonly utilized. One teacher even incorporated the classic arcade game Pac-Man into the classroom environment.

5.5 Grading and evaluation of assessment

Teachers’ approaches to assessing student knowledge and assigning grades varied. Some preferred oral assessments (Interviews 1, 4), with one teacher emphasizing the use of alternative tasks for written assessments, such as matching exercises or drawing/coloring activities (Interview 4).

Many teachers aimed to provide students with equal opportunities to demonstrate their knowledge through both oral and written assessments, while also considering their classroom performance. However, one teacher expressed a preference for written assessment, reserving oral evaluations for infrequent occasions (Interview 5).

The assessment of classroom activity was highlighted by several teachers as a means of encouraging active participation. One teacher described using the electronic record system (KRÉTA) to assign grades for classroom work, believing this fostered discipline and motivation due to perceived fairness (Interview 6). Conversely, another teacher reported that students were not motivated by grades for classwork but were deterred by penalties for missed homework (Interview 4).

A different approach involved awarding “small marks” for completed homework assignments or sub-tasks, with five such marks accumulating to a “big mark” in KRÉTA (Interview 8). Similarly, oral vocabulary test scores were averaged across three word lists to produce a single grade. Several teachers also emphasized the importance of positive feedback and a sense of achievement, allowing students to revisit previously mastered worksheets (Interview 3).

5.6 Perceived importance of language learning for students with mild intellectual disability

The majority of interviewed teachers affirmed the importance of foreign language learning for students with mild intellectual disability, citing a variety of justifications. Two teachers emphasized the potential for future travel or work opportunities abroad, arguing that even basic foreign language proficiency could prove invaluable in such situations (Interviews 1, 2). Others highlighted the potential for foreign language learning to foster development in other areas, such as time management and social skills (Interviews 4, 7, 8). Learning a foreign language, even at a basic level, can help students with mild intellectual disabilities navigate an increasingly interconnected world, especially with additional support during their secondary education.

The interview findings highlight the potential benefits of introducing foreign language learning to students with MID. Teachers predominantly expressed a positive outlook, citing advantages such as enhanced self-confidence, increased ability to navigate a globalized world, and the acquisition of practical vocabulary applicable to everyday situations.

The benefits extend beyond immediate academic applications. Early exposure to foreign language learning can foster a sense of accomplishment and self-efficacy in students, promoting personal development and potentially sparking future interests or pursuits. While some teachers believed that students with MID might not pursue careers requiring foreign language skills, others emphasized that early exposure could be beneficial for future learning or personal interests. The process of learning a new language can boost learners’ self-confidence and sense of accomplishment.

Additionally, basic vocabulary acquisition can aid in understanding foreign terms encountered in various contexts, such as online gaming or travel, thus enriching their engagement with the wider world. However, it might be difficult to find new and inviting material for the learners who are 13–16 years old since the materials focusing on the basics and simple sentences (e.g., numbers 1–100, food and drinks, means of transport, colours, clothes; I like/I dislike) are generally for young learners. The teenage learners find the materials and worksheets designed for pre-teens childish and do not take them seriously.

While some teachers acknowledged the potential challenges associated with language acquisition for students with MID, the overall consensus emphasized the importance of providing individualized support and adapting instruction to meet the specific needs of each learner. Collaboration with special education professionals can ensure that these students receive the necessary scaffolding to participate fully and reap the rewards of foreign language learning. Additional support from special education professionals may be necessary to ensure that students with MID are able to successfully participate in and benefit from foreign language learning.

Overall, the findings suggest that introducing foreign language learning to students with MID can have a positive impact on their personal development, self-confidence, and ability to engage with the wider world. Also, learning English can help to widen the world for MID learners as they hear about different and new sports, hobbies (such as darts), customs (e.g., drinking tea with milk), school life and way of living in general.

In terms of teaching strategies, the instructional approach has to move from a teacher-centred to a learner-centred one because this facilitates easy understanding of concepts as pupils construct meanings on their own by participating fully in the lesson (Bawa and Osei, 2018). UNICEF also underlines that a teacher has to be skillful enough to control any class using different methods in order to facilitate quality education of the child (UNICEF, 2000). According to Hungarian respondents, by tailoring instruction and providing appropriate support, educators can unlock the potential of these learners and equip them with valuable skills for navigating an increasingly interconnected world. The specific needs and abilities of individual students should be taken into account when designing foreign language instruction for learners with MID.

In conclusion, the introduction of foreign language learning to students with MID holds promise for fostering personal growth, enhancing self-confidence, and promoting engagement with a globalized society.

5.7 Teachers’ experiences of joy and success

The majority of teachers derived a sense of professional fulfillment and accomplishment from witnessing the tangible impact of their instruction on students’ language development and overall well-being. For some, this manifested as the superior performance of their former students in higher grades compared to peers from other schools (Interview 1). Others found gratification in observing students spontaneously applying their language skills in real-world contexts (Interview 4). Success was also perceived in smaller, everyday victories, such as unexpected recall of previously learned material or active participation in classroom activities (Interview 5).

A recurring theme among the teachers was the profound satisfaction gained from witnessing students’ enjoyment of language lessons, their enthusiasm for participation, and their active engagement in the learning process. This was exemplified by one teacher’s account of a collaborative effort between the language and music teachers, culminating in a successful student performance of a song in English at a school event. This anecdote underscores the power of language learning to foster not only linguistic competence but also a sense of community and shared accomplishment.

5.8 Difficulties in teaching languages to students with learning difficulties

Teachers identify several challenges in teaching foreign languages to students with learning difficulties. Utami et al. (2021) conducted some research about teachers’ problems and solutions in teaching English to students with ID involving interviews with five teachers in Indonesia. The teachers were uncertain about what methods to use and lack of memory and lack of confidence to speak of the students were also problems. The teachers came up with different solutions to overcome the problems. First, they explained the material in details and used videos and smartphones to provide examples of the right pronunciation. Also, they used drills, handmade posters and smartphone applications to explain the material and to help students remember the vocabulary. Moreover, songs and realia were used for better understanding (cited in Sab’na et al., 2024).

Another piece of research undertaken by Fazira in Indonesia in 2023 found problems in four different areas: curriculum, attitudes and behaviour of students, material and learning models and media. The teachers did not have the necessary experience and found it difficult to attract the focus of their students. Also, the teachers had difficulties when teaching reading and writing. Finally, they experienced the lack of learning support media. According to the author, to overcome these problems, the government needs to provide the right training for the teachers. Also, teachers must be very patient and understand the characteristics of their students. Teachers must reduce the material and modify their teaching techniques (cited in Sab’na et al., 2024).

As for student-related challenges in Hungary, teachers mentioned the difficulty in retaining new material, necessitating frequent repetition (Interviews 1, 2, 4, 5). Sab’na et al. (2024) asked an English teacher in an Indonesian middle school asking about differences experienced when teaching English to students with MID. After conducting the interview and the observation, they found five challenges: classroom management, students’ lack of general cognition, lack of focus, students’ short memory and English pronunciation, e.g., the learners pronounced the same English word several times in an inaccurate way. The teacher decided to provide pronunciation of words very slowly or per syllable, later repeating them or using the grill method. Hungarian teachers also experience challenges with pronunciation and spelling, particularly in English, often attributed to difficulties with the native language (Interviews 1, 2, 7). As Shree and Shukla (2016) points out, this is in connection with delayed language development and comprehension difficulties.

Students have difficulties interpreting foreign language texts, despite understanding individual words (Interview 5) and they have difficulties transferring language structures to new contexts (Interview 9) due to an inability or problems with abstract thinking. Absenteeism, hindering progress and classroom integration were also mentioned (Interviews 2, 4, 5) as well as the lack of motivation or negative self-beliefs about language learning ability (Interview 11). The issue of truancy on the part of pupils and general discipline problems affecting learning English were raised in research in Ghana too (Bawa and Osei, 2018). The researchers observed that pupils’ participation in English lessons was very poor: they did not pay attention or participate actively in the lessons.

The influence of native language skills on foreign language acquisition was a point of contention among Hungarian teachers. While the majority acknowledged a negative impact, citing issues with speech understanding, listening, inductive reasoning, vocabulary, and mental lexicon stability, two teachers argued for the independence of the two processes (Interviews 6, 7). One attributed potential difficulties to heightened expectations for students proficient in their first language (L1), while the other emphasized fundamental differences between first and second language acquisition processes.

We could also observe teacher-related challenges such as frustration due to the perceived mechanical nature of student learning and lack of visible progress (Interview 2). Our respondents also mentioned challenges in differentiating instruction to address varying student needs and absences (Interview 4). Another issue was the lack of preparation time and prior knowledge about students, particularly in new teaching situations (Interview 5). The results of Sab’na et al. (2024) raise the issue of classroom management, since some students can be very active, while others are passive, or else students disturb each other, which can lead to disruption of the class. Sometimes the English teacher needs to deal with conflicts occurring between the students in the class. The solution of the teacher in question was to diagnose the abilities of each student in order to choose the appropriate learning model for the student. One of the Hungarian participants also mentioned initial difficulties with classroom management and adapting teaching methods (Interview 6). A respondent added the limited time to build rapport with challenging students (Interview 7). Also, socio-cultural disparities among students and a limited support from teaching assistants who may not understand the target language (Interview 1) is a challenge in the classroom.

When analyzing our data, we could find resource and systemic challenges too. One German language teacher cited the lack of appropriate teaching materials, digital resources, and a foreign language curriculum specific to students with MID as hindrances to effective instruction. This sentiment was echoed by other German language teachers who relied on supplementary materials from various sources to differentiate instruction. However, the collection and adaptation of these materials were time-consuming and highlighted the need for specialized textbooks with accompanying workbooks and audio resources. Both German teachers added the increased workload due to the need to collect and adapt materials (e.g., Kotzné Havas and Szendy, 2009; Krulak-Kempisty et al., 2014; Angeli et al., 2017) to address diverse student abilities and interests (Interviews 10, 11).

Overall, these findings align with previous research by Meggyesné Hosszu (2015), indicating that existing German language textbooks for special schools are often misaligned with the interests and developmental needs of older students with learning difficulties.

6 Opinion of learners with MID about learning a foreign language

In terms of implementing a case study design, a focus group discussion took place in 2023 with 8 seventh-grade Hungarian students with MID. This specific case study offered an opportunity to reveal a nuanced and more complex picture of the situation, specifically from the English learners’ perspectives. The research was conducted in a segregated primary school in Eastern Hungary because the school provides learning services for children with MID. The group consisted of four boys and four girls with MID, aged between 13 and 15. The conversations were audio-recorded with the written consent of the head teacher and parents. The instrument used in this part of the study provided learners’ actual words, offering new views on the study topic. The next step after collecting the data from the learners was to analyze it. In this research, the data were analyzed qualitatively consisting of data reduction, data display and concluding.

During the conversation, students mentioned several foreign languages: English, German, Romanian, Russian, Ukrainian, Japanese and Chinese. The students acknowledged the potential benefits of English for future employment and travel, recognizing its practical applications in daily life: ‘If we go to work somewhere else, we should understand that language. You can make friends. If we go on a trip, we can understand what they say; we can ask about jobs, like delivery or whatever’. Referring to computers and everyday language, one student mentioned English terms such as Welcome, support, pink, telephone, dislike, and then added I can always see “milk” on milk. However, they also identified challenges related to vocabulary acquisition, grammar, and pronunciation because “you have to learn the words and how to write and count in another language” and “you have to learn to speak, read, write and count in English”.

Opinions regarding the frequency and timing of English lessons were mixed, with some students expressing a desire for more frequent or earlier instruction. Some children say it would be good to start learning languages earlier, even in fifth grade. Another student said that it would be better to have English lessons in the morning rather than in the afternoon, because they would not be tired.

Engagement with English outside of school was limited, primarily consisting of listening to English music for a few students. Unlike the majority of children, they do not watch English language videos, films and TV series. Only one pupil mentioned that he watches films in Hungarian with English subtitles. This student says “Good morning” to his family in the morning, or when I go to shower in the morning, I say “go to shower”.

The findings suggest a complex interplay between the perceived value of English and the challenges inherent in language learning for students with MID. While these students recognize the potential advantages of acquiring English proficiency, their learning needs and preferences may not be fully met by current instructional practices.

7 Summary

Teachers in Hungary perceive foreign language learning as an avenue for students with learning disabilities to develop holistically, fostering personal growth, social skills, and self-confidence. They emphasize cross-curricular connections and the cultivation of intercultural competence. However, the diverse range of abilities and interests among students necessitates differentiated instruction, prompting teachers to focus on positive reinforcement and encouragement. The integration of technology, such as interactive whiteboards and mobile devices, allows for the incorporation of varied and engaging activities into lessons.

In Hungary, foreign language instruction for students with MID is characterized by institutional autonomy and a nascent pedagogical approach. Educators adapt teaching the English content to align with societal expectations and individual student needs, often employing playful and engaging activities to enhance motivation. One of the most important challenges is that learners with MID not only require extra time and patience, but also, they demand specific educational strategies in a well-structured, specific learning environment and strategies that increase their motivation for learning. Sometimes teachers feel it is a boring and unpromising job. However, it is important to note that these learners are also able to learn, though need different instructions and methods.

The limited availability of specialized teaching materials necessitates teacher creativity and resourcefulness, often leading to the adaptation of materials designed for mainstream education. Experiential learning and playful exercises are employed to maintain student engagement, with board games being particularly effective for promoting cooperation and tolerance.

The primary objective of foreign language instruction for students with MID is not solely linguistic proficiency, but also the enhancement of motivation, self-awareness, and self-esteem. Learning a language can help learners with MID to navigate in a globalized world. Moreover, basic vocabulary can aid students in understanding foreign terms encountered in everyday life, such as those found in internet games or while traveling.

Teaching foreign languages to students with learning disabilities presents both challenges and opportunities for educators. Teachers identified a range of challenges in their practice, including.

student-related challenges, teacher-related challenges, resource and systemic challenges as well as linguistic challenges. However, teachers involved in the research strive to create enjoyable and stimulating lessons that foster personal growth and push students beyond their perceived limitations. Teachers prioritize repetition and practice over error correction, recognizing that language learning contributes to overall cognitive development and increased self-confidence. Therefore, multiple sensory experiences must be used to support encoding information with vision, hearing and/or movement as we remember best when multiple brains functions are stimulated. Using real objects can increase motivation, reduce anxiety and facilitate a more effective and meaningful learning environment.

By focusing on positive reinforcement and individualized instruction, teachers can empower students with learning disabilities to overcome challenges and develop valuable language skills.

This study highlights the importance of tailoring foreign language instruction to the specific needs of students with MID. Incorporating engaging activities, leveraging their interests, and providing opportunities for real-world application could enhance motivation and facilitate language acquisition. However, as intellectual disability has an impact on communication and social behaviour, sincere support from the family and the wider community, including employers, are still needed. Additionally, fostering exposure to English through music, media, or other extracurricular activities may cultivate a more positive attitude towards language learning, thereby increasing the likelihood of long-term success.

It has become clear to us from a focus group discussion that students acknowledge the importance of language learning and generally enjoy the lessons, they encounter difficulties due to linguistic differences between their native and target languages. In language lessons, children enjoy talking, playing games and listening to songs. Children want to learn English because it can be useful for working and traveling (e.g., shopping) in the future: “I want to go to Russia because it’s good there.” They enjoy movement activities (e.g., Simon says) rather less.

Our research has its limits in terms of the number of teachers and learners involved in the research. Further research is still required to explore effective pedagogical approaches and strategies for teaching foreign languages to students with learning disabilities. Only by understanding their unique learning profiles and addressing their specific challenges, educators can unlock their potential and empower them to become functioning foreign language users.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MN: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^2011. évi CXC. törvény a nemzeti köznevelésről https://net.jogtar.hu/jogszabaly?docid=a1100190.tv (2023. február 4).

2. ^https://www.oktatas2030.hu/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/nat2020-5-2020.-korm.-rendelet.pdf

3. ^51/2012. (XII.21.) számú EMMI rendelet 11. melléklete Kerettantervek a sajátos nevelési igényű tanulókat oktató nevelési-oktatási intézmények számára- Kerettantervek az enyhén értelmi fogyatékos gyermekek számára (1–8. évfolyam)- Idegen nyelv. Web. http://kerettan terv.ofi.hu/11_melleklet_sni/enyhe/index_sni_ enyhe.html Downloaded: 2019.10.15.

References

Ahyatul, U. (2021): The influence of using mimicry memorization method towards students’ vocabulary mastery at the eighth grade of SMP N 1Cukuh Balak at the first semester in the academic year of 2020/2021. Available at: http://repository.radenintan.ac.id/14899/2/PUSAT%20BAB%201%202.pdf. (accessed April 22, 2023)

American Psychiatric Association, DSM-5 Task Force. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™ (5th ed.). Washinton DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Bawa, A., and Osei, M. (2018). English language education and children with intellectual disabilities. Int. J. Dev. Sustain. 7, 2704–2715.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Cando Yánez, R. E., Andrade Morán, J. I., and Cando Guanoluisa, F. S. (2024). Using realia in teaching English vocabulary to a mildly intellectually disabled student. Revista Científica De Innovación Educativa Y Sociedad Actual "ALCON" 4, 91–104. doi: 10.62305/alcon.v4i4.210

Coşkun, A. (2013). Teaching English to non-native learners of English with mild cognitive impairment. Mod. J. Lang. Teach. Methods 3, 8–16.

Czibere, C., and Kisvári, A. (2006). Inkluzív nevelés. Ajánlások tanulásban akadályozott gyermekek, tanulók kompetencia alapú fejlesztéséhez. Budapest: SuliNova Közoktatás-fejlesztési és Pedagógus-továbbképzési Kht.

European Commission (2005). Special educational needs in Europe. The teaching and learning of languages. Insights and innovation. Teaching languages to learners with special needs. Available at: https://incpill.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/eudxamfl.pdf

Irfan, F., Awan, T. H., Bashir, T., and Ahmed, H. R. (2021). Using realia to improve English vocabulary at primary level. Multicult. Educ. 7, 340–354. doi: 10.5281/ZENODO.4647933

Krulak-Kempisty, E., Reitzig, L., Erndt, E., Sárvári, T., and Gyuris, E. (2014). Hallo, Max 1. Budapest: Klett. Kiadó.

Lestari, Z. W., Koeriah, N., and Nur’aeni, N. (2022). English language learning for mild intellectual disability students during pandemic. J. Engl. Educ. Teach. 6, 89–102. doi: 10.33369/jeet.6.1.89-102

Meggyesné Hosszu, T. (2015). A tanulásban akadályozott gyermekek idegen nyelv tanításának kérdései. Szeged: Szegedi Tudomány Egyetem JGYPK Gyógypedagógus-képző Intézet.

Meggyesné Hosszu, T. (2019): Enyhén értelmi fogyatékos tanulók idegennyelv-tanulási motivációja az eltérő tantervű általános iskolák 8. osztályában (PhD dissertation). Manuscript. Available at: https://pea.lib.pte.hu/bitstream/handle/pea/23486/meggyesne-hosszu-timea-phd-2020.pdf.

Meggyesné Hosszu, T. (2018a). Esélyt nyújtunk vagy túlterheljük az enyhén értelmi fogyatékos a kötelező idegennyelv-tanulással? in Gyógypedagógia – dialógusban Fogyatékossággal élő gyermekek, fiatalok és felnőttek egyéni megsegítésének lehetőségei. ed. B. Rita, 357–366. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/121259598/Gy%C3%B3gypedag%C3%B3gia_dial%C3%B3gusban_Fogyat%C3%A9koss%C3%A1ggal_%C3%A9l%C5%91_gyermekek_fiatalok_%C3%A9s_feln%C5%91ttek_egy%C3%A9ni_megseg%C3%ADt%C3%A9s%C3%A9nek_lehet%C5%91s%C3%A9gei (accessed April 22, 2023)

Meggyesné Hosszu, T., and Lesznyák, M. (2017). Az idegen nyelvet tanító pedagógusok módszertani repertoárja a tanulásban akadályozott gyermekek iskoláiban. Modern Nyelvoktatás 23, 22–42.

Mesterházi, Zs. (1997). “Tanulási akadályozottság” in Pedagógiai Lexikon III. eds. Z. Báthory and I. Falus (Budapest: Keraban Könyvkiadó), 17–20.

Nemes, M., and Rózsa, H. (2021). A tanulásban akadályozott tanulók német nyelvoktatásának helyzete – hazai és nemzetközi kitekintés. Különleges Bánásmód 7, 55–67. doi: 10.18458/KB.2021.4.55

Pokrivčáková, S. (2015). Foreign language education of learners with special educational needs in Slovakia. Int. J. Arts Commer. 2, 115–126. doi: 10.17846/SEN.2015.7-28

Sab’na, S., Nasrullah, N., and Rosalina, E. (2024). English Teacher’s challenges and solutions in teaching intellectual disability students: case study. Interaction 11, 116–128. doi: 10.36232/jurnalpendidikanbahasa.v11i1.6130

Shree, A., and Shukla, P. C. (2016). Intellectual disability: definition, classification, causes and characteristics. Learn. Community Int. J. Educ. Soc. Dev. 7, 9–20. doi: 10.5958/2231-458X.2016.00002.6

Tulus, M., and Rihanatul, F. (2021). Arabic phonological interventions with mimicry-memorization learning method: a review on evidence-based treatment. J. Pendidikan 6, 96–102. doi: 10.17977/jptpp.v6i1.14396

UNICEF (2000). Quality in education: A paper presented by UNICEF at the meeting of the. Italy: International Working Group on Education Florence.

Utami, R. P., Suhardi, K. P., and Astuti, U. P. (2021). EFL teachers’ problems and solutions in teaching English to students with intellectual and developmental disability. Indones. J. Appl. Linguist. 6, 173–188. doi: 10.21093/ijeltal.v6i1.912

Keywords: English, individual abilities, teachers’ perspectives, methodological approach, learning experiences of students with mild intellectual disabilities, motivation, personal factors, creativity

Citation: Nemes M (2024) Teaching a second language to learners with mild intellectual disabilities – a Hungarian case study. Front. Educ. 9:1450095. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1450095

Edited by:

Jitka Sedláčková, Masaryk University, CzechiaReviewed by:

Jana Chocholata, Masaryk University, CzechiaSilvia Pokrivcakova, University of Trnava, Slovakia

Copyright © 2024 Nemes. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Magdolna Nemes, bmVtZXNtQHBlZC51bmlkZWIuaHU=

Magdolna Nemes

Magdolna Nemes