- 1Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, Manipal College of Dental Sciences Mangalore, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Karnataka, Manipal, India

- 2Department of Periodontology, Manipal College of Dental Sciences Mangalore, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Karnataka, Manipal, India

- 3Head, Medical Education College of Medicine and Health Sciences, National University of Science and Technology, Muscat, Oman

- 4Department of Community Medicine, Kasturba Medical College Mangalore, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Karnataka, Manipal, India

Introduction: This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of a dental practice management education module developed through interprofessional collaboration.

Materials and methods: A dental practice management module was developed through need assessment, literature review, and interprofessional collaboration. The IP team included dental practitioners, dental educators, business expert, lawyer, bioethicist, engineer, and architects. Thirty interns were included in the study. Participants were assessed through pre-and post-test. Evaluation of the program was carried out by obtaining feedback from the students and dental practitioners who were invited to attend the program. The pre-and post-test results were compared by paired student t-test. p-value of <0.01 was considered significant. The content of the feedback forms was subjected to qualitative and descriptive analysis.

Results: Through the process of module preparation, pertinent competencies were identified and included in the program. There was a statistically significant increase in knowledge among students with respect to the domains included, as shown in the pre-post-test comparisons. The feedback obtained was positive. IP collaboration in module design and implementation was considered an important factor for dental practice management.

Conclusion: Practice management education can be made effective through IP collaborations.

1 Introduction

The prime focus of every dental curriculum is to develop clinical skills in students, i.e., to develop the ability to diagnose, treat, and prevent orofacial diseases (Verma et al., 2018). Excellence in clinical skills is the most basic requirement to be a successful dentist, but it is not the only essential criterion (Barber et al., 2011; Manakil et al., 2015). A dentist in practice set-up is required to be able to treat a patient in an ethical, comprehensive, and holistic manner, with sufficient knowledge of his or her legal responsibilities and liabilities (Barber et al., 2011; Engels et al., 2005; Fontana et al., 2017). In addition, they must be skilled in working in multidisciplinary teams, leadership, business management, finances, marketing, and supervise auxiliary staff without compromising the quality of care (Fontana et al., 2017; Koole et al., 2017). The curriculum should account for changing trends in the work environment; failing to do so will leave the student under-exposed to competency related to practice management (Dagli and Dagli, 2015; Priyaa et al., 2022).

In India, the dental curriculum for the five-year program is prescribed by the Dental Council of India (DCI) with approximately 26,549 students graduating annually from dental colleges with the undergraduate degree of “Bachelors in Dentistry (BDS).” The number of postgraduate seats available is around 6,228, leaving an abysmal proportion of 75% of the graduates without an opportunity to pursue their higher studies (Dagli and Dagli, 2015). In addition, the employment opportunities for a newly graduated dentist is limited. Around 5% of these graduates get employed in the government sector, and a few more find employment in dental institutions or corporate-run hospitals. Hence the majority of dental graduates usually are self-employed through the establishment of dental practice.

The syllabus outlined by DCI has included practice management education as a part of the subject Public health dentistry with 6 h of lecture sessions and an optional field report on practice management. The current curriculum does not deal with all the competencies required for practice management sufficiently (Priyaa et al., 2022; Kabra et al., 2023) This is further evident in the recent curricular reform proposal by the dental council of India (DCI 2022) which aims to introduce choice based curriculum which includes a competency on practice management (Kabra et al., 2023). However, the document does not outline curricular content for the same. Additionally, IPE is not systematically implemented with minimal formal interprofessional education involving dental students. Thus, the students miss out on collaborative competencies of team work and communication vital for practice management (Niranjane et al., 2023). Similar gaps in dental practice management have also been reported in dental schools despite having a separate dedicated course for practice management education (Kabra et al., 2023; Niranjane et al., 2023). Thus, there is a need to better the undergraduate dental practice management education curriculum and make it more relevant.

Overall, the project aimed to evaluate the existing dental curriculum for the tenets of practice management, identify gaps, and subsequently for the creation of a module that would address the deficiencies in practice management education. It was recognized that one of the ways to improve on this curriculum would be to collaborate interprofessionally, as several of the topics in practice management education (e.g., business management) can benefit from the expertise of a subject expert (e.g., financial expert). Thus, it was decided to implement a dental practice management program for the Interns, in collaboration with an interprofessional team (IP Team) and evaluate it. A brief experience report of this present project has been previously published in literature as a part of fellowship requirements of the first author (Sujir et al., 2020). This paper reports in detail about the process of module development and evaluation of this pilot project.

2 Materials and methods

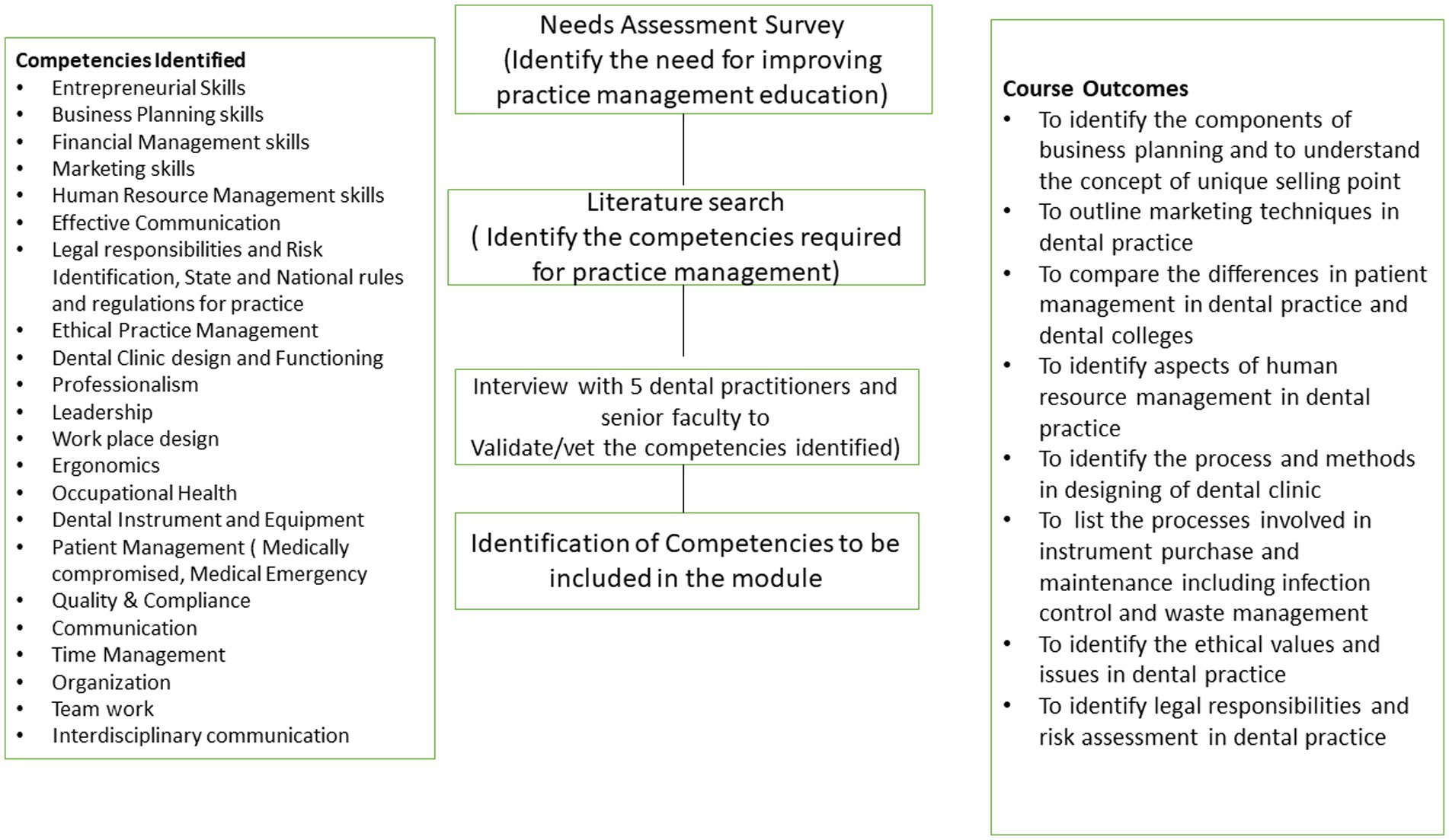

This project was implemented after obtaining approval from the institutional ethics committee (Approval Number 18052). A brief overview of the methodology has been depicted in Figure 1. First, a needs assessment activity was carried out through a survey among 151 dental practitioners to determine the need for introducing a separate dental practice education module into the curriculum. Also, a thorough literature review of the past 10 years (2008–2018) was done to identify the basic competencies in practice management education. The search terms General Practice, Practice Management, Dental Education, Students, Dental were utilized to search the “PubMed and Scopus” database. The relevant competencies were identified, as shown in Figure 1. These competencies were then vetted by five dental practitioners through an interview format using a semi structured questionnaire, which focused on “need to include the topics,” “suggestions related to content of the topic” and “identification of new topics” that may be incorporated. After the inputs from dental practitioners a final list of competencies to be included in the module was made in consultation with senior faculty members. Thus, first with the inputs from the dental practitioners and then senior faculty members the course outcomes were finalized. As the students undergo a rigorous clinical rotation involving all disciplines during their dental education, the focus of this module was restricted to relevant theoretical basics that involves starting and maintaining a dental practice. Following the development of course outcomes the IP team were selected based on the professional expertise required for each topic (for, e.g., topic on legal aspects would benefit the expertise of a lawyer). Considering the course outcomes the IP team members included were dental practitioners, business expert, lawyer, bioethicist, engineer, and architects. The IP team members were provided with the course outcomes, along with dental practice management literature references and feedback from practitioners. The IP team and the course coordinator prepared the module and the assessment test which included MCQs, essay test and case/scenario-based questions. The content of the module was validated by senior faculty members from Department of Prosthodontics, Conservative Dentistry and Public health dentistry, who also owned dental clinics. Thus, a total of 7 teaching units each of 2.5 h. duration, spread across a period of 6 months duration, were planned for the interns (Table 1).

The program was offered to the dental students during their internship as an elective course. Dental intern students have competed 4 years of undergraduate training and are on compulsory rotating posting. The students have experience in all disciplines of dentistry and would have completed considerable clinical work with a good awareness of patient treatment processes. Detailed information about the program and recruitment was provided to the batch of interns (n = 93). They were then invited to participate in this program. Thirty interns who agreed to meet the course requirements and enroll for the study were included in the program as study participants. However, the sessions were kept open for all interns to attend. All required permissions were sought, and the timeline of the program was announced in advance so that the interns could schedule their patient work accordingly to attend the sessions. Assessments for the interns were carried out for each topic and done through pre-test and immediate post-test comparisons (n = 5 tests).

Each of these sessions was also attended by five dental practitioners on an invitation basis. The dental practitioners were identified through purposive sampling. These practitioners were asked to evaluate each session through a feedback form that contained open and closed-ended questions. The feedback forms were validated by expert review. The questions rated on a Likert scale explored (1) The need for including the topic in the practice management curriculum (2) The appropriateness of the content covered during each session, and (3) Need for IP collaboration for the session. The participants were also given open-ended questions to further express their opinions on the content of the sessions, new aspects learnt and aspects that did not contribute to the learning objectives of the session. Similarly, feedback from the participating interns was also obtained after each session through questionnaire.

2.1 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the collected data was done using SPSS version 2.5 (IBM SPSS® Statistics). The pre-and post-test results were compared by paired student t-test. p-value of <0.01 was considered significant. The content of the feedback forms was subjected to qualitative and descriptive analysis.

3 Results

3.1 Survey

Among the 151 practitioners, approximately 75% of the participants responded that the undergraduate curriculum was not adequate to prepare them for a dental practice. The majority of them indicated that several of the competencies for practice management were gained through experience and guidance of mentors. The survey showed a favorable response to the involvement of Interprofessional team in dental practice management education.

3.2 Literature review

A total of 2045 articles were listed after multiple searches, out of which 191articles were selected based on the title, and furthermore 61 articles were selected for final reference after evaluating the abstract. The relevant competencies were identified from the literature, as shown in Figure 1.

3.3 Vetting of the curriculum

The competencies were reviewed by five dental practitioners and senior faculties. They then narrowed down competencies best suited for this specific IP collaborative module to (1) Business management, (2) Finance, (3) Marketing, (4) Human resource management, (5) Patient management, (6) Instrument and equipment purchase and maintenance, (7) Clinic design, (8) Legal aspects, (9) Ethics. The practitioners also highlighted the important aspects that need to be included for each competency, which was utilized to frame course outcomes. The final course outcomes that were derived are summarized in Figure 1. The details of each module of the course are summarized in Table 1.

3.4 Program assessment (Pre and Post-Test)

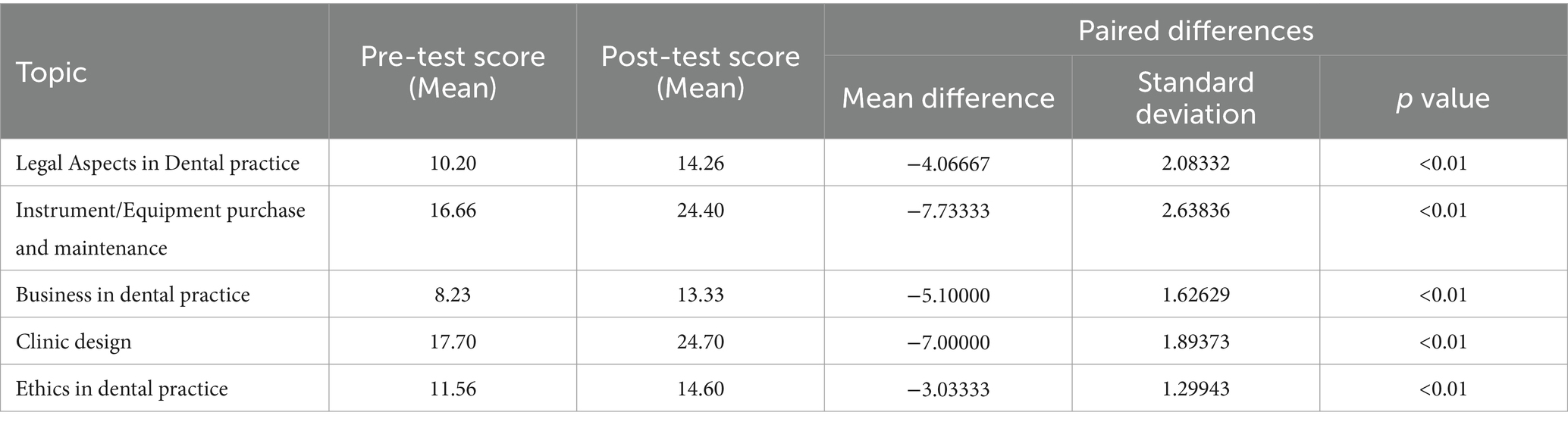

A total of 30 interns were included in the study. The mean age group was 23.4 ± 1.3, with 21 females and 7 males. The summary of the pre-test and post-test according to the topics has been summarized in Table 2. There was a statistically significant improvement in post-test scores in comparison to the pre-test.

Table 2. Pre and post test scores of the Intern student participants (N = 30) for the individual modules.

3.5 Program evaluation

3.5.1 Student feedback

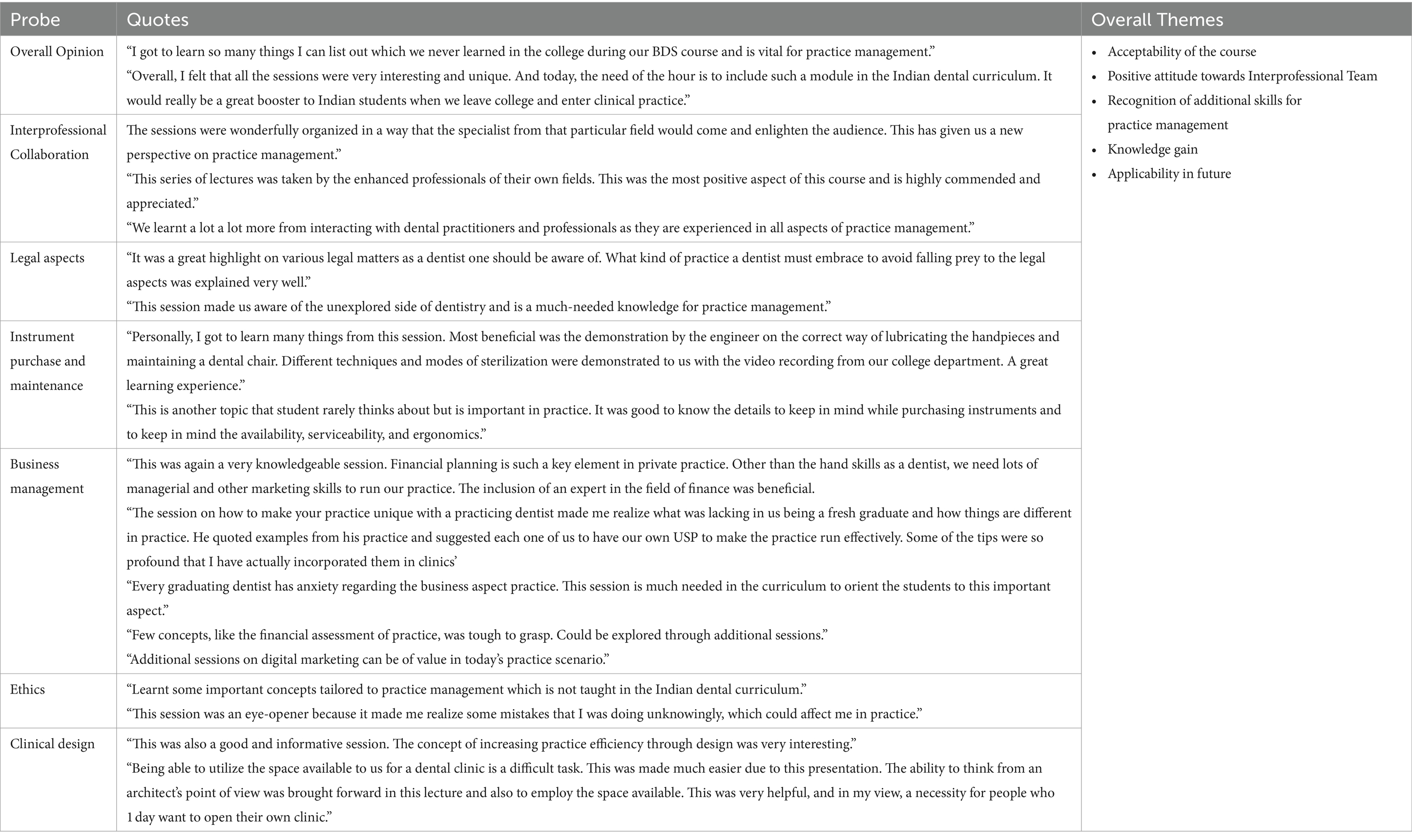

All the interns strongly agreed on the need for a dental practice management education program to be included in the curriculum. All participants strongly agreed that interprofessional collaboration was beneficial to the program. They noted that the concepts of business management and legal aspects as most challenging and suggested an increase in the time allotted for these topics. The students also wanted more content on digital marketing for a dental practice. The feedback given by students is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Excerpts of the Feedback from the student participants (n = 30) on the individual sessions of the module.

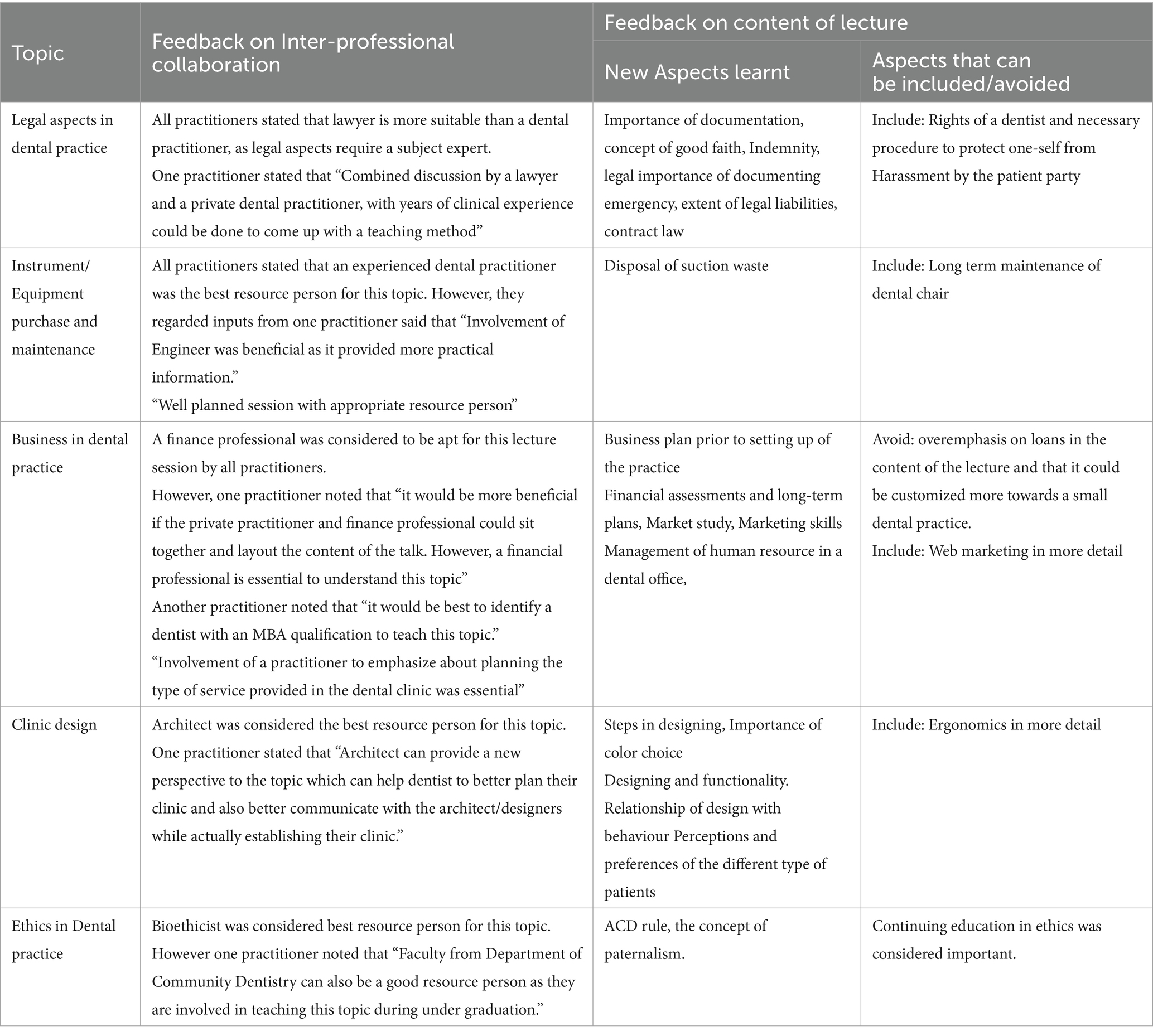

3.5.2 Feedback from practitioner

All the practitioners evaluating the lecture sessions strongly agreed that the topics included were important for dental practice management education, and the content of the sessions was appropriate. They also strongly agreed that IP collaboration was needed for the topics included. The practitioners suggested that the topic of Legal aspects, Business Management, Clinic Design, and Ethics should be introduced during the internship. Two practitioners felt that the topic of instrument purchasing and maintenance should be introduced during the third year of the undergraduate course, as the students would be introduced to clinics at that time and would be purchasing and handling instruments. The excerpts of the feedback provided by the practitioners on the individual modules are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Excerpts of the Feedback from the Dental practitioners (n = 5) on the individual sessions of the module.

4 Discussion

Dental practice management education is a challenging subject to be included in the curriculum as it includes varied topics that are far beyond the expertise of dental sciences and there have been no studies that have evaluated practice management education for the Indian context. Hence, our aim was to develop a program that included the competencies required for practice management, which were lacking in the Indian undergraduate dental curriculum. The problem areas of practice management education that are most often identified in these surveys are rooted in subjects that are beyond the domains of dental sciences. Our efforts were directed towards IP collaboration with subject experts to help bridge the gaps identified in dental practice management education, and through this study, IP collaboration has proven to be extremely beneficial. Similarly, the benefits of inviting a variety of professionals as guest lecturers for practice management courses in Canadian dental school has been identified by Schonwetter et al., as critical for the success of these courses as the professionals provide authentic learning material and also, it provides a forum for the students to interact with professionals, who could be consultants in their work environment (Schonwetter et al., 2018). The strength of this program is that the course outcomes were framed in collaboration with the IP partners. It would have been prudent for professionals as well as dental practitioners to meet and collaborate on the content prior to the program implementation. However, scheduling issues between the various professionals often posed challenges in organizing such meetings. We tried to overcome this limitation by two methods. Firstly, content for the program was set by consulting with the practitioners through an interview and presenting the findings to the IP team thereafter. The resource persons then formulated the educational objectives for the program based on these inputs and literature review. Secondly, dental practitioners were also invited to attend these sessions and to give their feedback. Literature shows that the teaching hours dedicated to this vast subject vary from 11.5 to 244 h (Willis, 2009). The total duration of our program was 17.5 h. This was scheduled considering the fact that the program was implemented during internship, during which the students have a busy clinical schedule.

Among the topics included insights into selecting, purchasing, and maintaining the dental instruments and material is recognized to be one of the most important aspects in practice management as this would be the foundation for all services provided at a dental clinic (Kalenderian et al., 2010). Also, the importance of a good ergonomically designed dental clinic and its role in facilitating increased work efficiency and prevention of occupational hazards is well known. The session on clinic design also highlighted the influence of design in patient management and satisfaction. The inclusion of legal aspects and ethics was considered necessary by experts and an interprofessional approach greatly contributed to the quality of the sessions. Legislature and laws change with time, and legal outcomes change with precedent. A lawyer is in the best position to be aware of these changing legal trends. The inclusion of a lawyer in formulating the program has helped identify additional aspects such as privacy laws and possible liabilities. Situations in dental practice often require not only legal but also ethical considerations. The case-based discussions on ethics tailored to practice management included in this program proved beneficial and is a necessary addition in the dental practice management curriculum. A qualified expert provided credibility to these discussions. Ethics is a continuous learning process, and the students should be made aware of available resources for future reference.

Business management of dental practice is included by some universities in their practice management courses, while many others, e.g., in India and Germany (Heitkamp et al., 2018) do not include this topic in the undergraduate curriculum. Van der Berg-Cloete et al. (2016) in their study, have highlighted the need to strengthen management training in South African dental schools. This was considered as an essential component in the program and the IP collaboration for the implementation of this session was much appreciated.

In a similar project, a two-day dental practice management module with similar learning objectives as the present module was implemented by Safi et al. (2015), for practicing dentists as a continuing dental education program. The course was found to be beneficial with the participants indicating the need for training in non-clinical domains for dental practice. Literature and our present experiences positively indicate the need to train dentists in the varied non-clinical aspects of practice management. It is important to start laying the foundation in the undergraduate curriculum as it is intrinsic to the vocational demands of a dental practice, and the new graduate is better prepared to embark on the daunting and stressful task of managing a dental practice.

Proficiency in this topic can be expected only through curricula innovation such as that described by Pousson and McDonald (2004), to inculcate business management and teamwork skills. Case-based discussion, simulations, mentorship, reflective practices, unique clinical practice models can also help to improve practice management education. Changes in the dental practice management curriculum should also keep abreast with changing practice trends over time (Karimbux, 2015). Presently, in the context of the Indian dental curriculum, competencies such as leadership aspects with communication, teamwork, conflict management, cultural awareness, are learnt in an unstructured format, and an organized attempt to deliberately include this in the curriculum is lacking. Additionally, introduction of interprofessional education can further strengthen the dental practice curriculum (Ramprasad et al., 2018).

A dedicated assessment framework for these extremely important competencies needs to be established. Feedback from the graduating students is key to curriculum revisions (Nicolas et al., 2009). This has been well document by the AEDA survey, which has seen improvement in the perceived appropriateness of time allotted to practice management among the students over time (Garrison et al., 2014).

Assessment employed during this course focused on knowledge (MCQ) and analytical skills (Case based discussion). This can be accompanied by including experiential learning methods for practice management. Practice management modelled clinical set-up (Karimbux, 2015) supplemented by work shadowing dental practitioners (Heitkamp et al., 2018) has shown to increase confidence, inculcate higher professionalism, with significant improvement in specialized skills, communication, and social competencies (Heitkamp et al., 2018). Comprehensive clinical set-up can further contribute to practice management education (Karuveettil et al., 2021). However, recreating a vocational situation within the protected confines of an academic setting can be challenging. Through the deliberations during this program, it was suggested that an ideal way to simulate the vocational environment might be to post the students in a dental clinic under the preview of the parent college in a location away from the academic settings. The responsibility to run these clinics can be largely expected to be taken up by the students with minimum supervision by faculty. Students could be posted during the final phase of their academic program so that they are well equipped to manage the patients (Sujir et al., 2020). Furthermore, considering the varied aspirations of graduating students, additional education in dental practice may be made optional similar to that of a vocational training program in UK (Bartlett et al., 2001).

This study was a pilot project implemented in a single institute. The education module was piloted to explore the feasibility and acceptance of the program. The main barriers faced during implementation of this project were scheduling difficulties in introducing a new course. Considering the academic schedule, requirements of the course which includes, mandatory attendance during multiple sessions and submission of assessment, students were invited to volunteer for enrolment to ensure compliance for the study requirements. Thus, this study included a sample of 30 students. The sample size is small and thus generalizability of the study findings is limited. Similar education modules can be implemented in other dental schools for generalizability of the outcomes. As discussed previously scheduling conflicts and time requirements hindered bringing together various members of the IP team and the dental practitioners for brainstorming a session. Bringing together diverse experts from diverse backgrounds is an essential step in interprofessional projects and would require long term planning for logistics, incentives and methods of communication. Additionally, the study reports short term outcomes of the education module, which was within the feasible scope of the study. The Indian dental curriculum is at the cusp of reforms and as rightly recognized by the DCI (2022) (Kabra et al., 2023) practice management education is an essential component that has been considered to be a part of the revised curriculum. The feasibility and acceptability of this pilot project hold promise as it provides key information to expand the program and aligning it to the recommended reforms in dental education. Feedback obtained will be incorporated in future iterations of the course and possibilities for hybrid learning will be explored. The course will also be incorporated into the academic curriculum. The future directions for this initiative would include expanding the elective course to other healthcare disciplines, integrating practice management into the core curricula, and planning longitudinal studies to assess its impact on professional performance and health outcomes. In addition, meaningful collaborations with industry partners would ensure that the curriculum remains dynamic and aligned with real-world needs thereby evolving with the changing landscape of healthcare practice management.

5 Conclusion

The dental practice management curriculum implemented here is a first of its kind program in the Indian academic setting, and the inclusion of the IP team makes this pilot program unique. Short term outcome of the program has shown learning among students and the advantages of interprofessional collaboration for module preparation. Also, the students were extremely interested in participating in this project. Future plans will include follow-up and obtaining feedback from the trained cohort for the assessment of long-term outcomes, which must be considered as a part of program evaluation. “This initiative serves as a catalyst for change by presenting an innovative and experiential approach to practice management education tailored for students in care professions. The paper outlines the successful implementation of this approach as an elective course within the dental curriculum, offering a proof of concept that highlights its effectiveness and its potential for broader application in healthcare education. By equipping future care professionals with essential management skills, this educational model not only enhances their ability to efficiently run their practice but also contribute towards improved health outcomes through more effective and patient-centred care delivery.”

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

This study involving humans was approved by Institutional Ethics Committee, Manipal College of Dental Sciences Mangalore (Approval number 18052). This study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

NS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CM: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AU: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the support of the faculty of MAHE-FAIMER International Institute, Dr Ashwin Rao (Associate Professor, Department of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry, MCODS, Mangalore), Dr Arvind Shenoy (Professor, Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Bapuji Dental College and Hospital, Davangere), Dr Savitha Shelly (Associate Professor, School of Management, Manipal Academy of Higher Education). Dr. Nandineni Rama Devi (Associate Director, Research & Collaborations,Faculty of Architecture, Manipal Academy of Higher Education), Ms Sonali Walimbe (Professor, Faculty of Architecture),Mr Prajosh (Architect) Mr Maheshchandra Nayak (Associate Professor,SDM Law College, Affiliated to Karnataka State Law University), Mr Ashok (Sr. Engineer, MCODS, Mangalore), Dr Shobha Rodriguez, (Professor, Department of Prosthodontics and Crown & Bridge, MCODS, Mangalore), Dr Puneeth Hegde (Associate Professor, Department of Prosthodontics and Crown & Bridge, MCODS, Mangalore), Dr Karthik Shetty (Professor and Head, Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Manipal College of Dental Sciences Mangalore), Dr Rekha Baliga (Dental Practitioner), Dr Anindita Saha (Dental Practitioner) and Dr Naveen Alva (Dental Practitioner), Dr Deepika (Dental Practitioner), Dr Pujan Kamath (Dental Practitioner), Dr Lakshmi Shetty (Dental Practitioner) for their valuable inputs for their contribution for in implementing this program.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1432823/full#supplementary-material

References

Barber, M., Wiesen, R., Arnold, S., Taichman, R. S., and Taichman, L. S. (2011). Perceptions of business skill development by graduates of the University of Michigan Dental School. J. Dent. Educ. 75, 505–517. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2011.75.4.tb05074.x

Bartlett, D. W., Coward, P. Y., Wilson, R., Goodsman, D., and Darby, J. (2001). Experiences and perceptions of vocational training reported by the 1999 cohort of vocational dental practitioners and their trainers in England and Wales. Br. Dent. J. 191, 265–270. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801159a

Dagli, N., and Dagli, R. (2015). Increasing unemployment among Indian dental graduates-high time to control dental manpower. J. Int. Oral Health 7, i–ii

Engels, Y., Campbell, S., Dautzenberg, M., van den Hombergh, P., Brinkmann, H., Szécsényi, J., et al. (2005). Developing a framework of, and quality indicators for, general practice management in Europe. Fam. Pract. 22, 215–222. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi002

Fontana, M., González-Cabezas, C., de Peralta, T., and Johnsen, D. C. (2017). Dental education required for the changing health care environment. J. Dent. Educ. 81:eS153-eS161. doi: 10.21815/JDE.017.022

Garrison, G. E., Lucas-Perry, E., McAllister, D. E., Anderson, E. L., and Valachovic, R. W. (2014). Annual ADEA survey of dental school seniors: 2013 graduating class. J. Dent. Educ. 78, 1214–1236. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2014.78.8.tb05793.x

Heitkamp, S. J., Rüttermann, S., and Gerhardt-Szép, S. (2018). Work shadowing in dental teaching practices: evaluation results of a collaborative study between university and general dental practices. BMC Med. Educ. 18, 99–14. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1220-4

Kabra, L., Santhosh, V. N., Sequeira, R. N., Ankola, A. V., and Coutinho, D. (2023). Dental curriculum reform in India: undergraduate students' awareness and perception on the newly proposed choice based credit system. J. Oral Biol. Craniofacial Res. 13, 630–635. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2023.08.003

Kalenderian, E., Skoulas, A., Timothe, P., and Friedland, B. (2010). Integrating leadership into a practice management curriculum for dental students. J. Dent. Educ. 74, 464–471. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2010.74.5.tb04892.x

Karimbux, N. Y. (2015). Teaching dental practice Management in a Time of change. J. Dent. Educ. 79, 463–464. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2015.79.5.tb05904.x

Karuveettil, V., Janakiram, C., Krishnan, V., Mathew, A., Venkitachalam, R., and Varma, B. (2021). Perceptions of a comprehensive dental care teaching clinic among stakeholders in a dental teaching hospital in South India: a baseline assessment. Med. J. Armed Forces India 77, S195–S201. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2020.12.032

Koole, S., Van Den Brulle, S., Christiaens, V., Jacquet, W., Cosyn, J., and De Bruyn, H. (2017). Competence profiles in undergraduate dental education: a comparison between theory and reality. BMC Oral Health 17:109. doi: 10.1186/s12903-017-0403-4

Manakil, J., Rihani, S., and George, R. (2015). Preparedness and practice management skills of graduating dental students entering the work force. Educ. Res. Int. 2015, 1–8. doi: 10.1155/2015/976124

Nicolas, E., Baptiste, M., and Roger-Leroi, V. (2009). Clermont-Ferrand dental school’ curriculum: an appraisal by last-year students and graduates. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 13, 93–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2008.00547.x

Niranjane, P. P., Mishra, V. P., Daigavane, P., and Lakhe, P. (2023). Perceptions of academic deans regarding interprofessional education and its implementation in dental colleges in India: results of a national survey. J. Interprof. Care 37, 932–937. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2023.2174091

Pousson, R. G., and McDonald, G. T. (2004). A model for increasing senior dental student production using private practice principles. J. Dent. Educ. 68, 1272–1277. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2004.68.12.tb03877.x

Priyaa, N. P., Jeevanandan, G., and Govindaraju, L. (2022). Practice management in undergraduate dental program: the need among dental students. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 13, S594–S598. doi: 10.4103/japtr.japtr_295_22

Ramprasad, V. P., Mansingh, P., and Gupta, K. (2018). Inter-professional education and collaboration in dentistry–current issues and concerns, in India: a narrative review. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 9, 261–265. doi: 10.5958/0976-5506.2018.01352.9

Safi, Y., Khami, M. R., Razeghi, S., Shamloo, N., Soroush, M., Akhgari, E., et al. (2015). Designing and implementation of a course on successful dental practice for dentists. J. Dent. 12, 447–455

Schonwetter, D. J., and Schwartz, B. (2018). Comparing practice management courses in Canadian dental schools. J. Dent. Educ. 82, 501–509. doi: 10.21815/JDE.018.055

Sujir, N, Naik, D, Jain, A, Uppor, A, Mohammed, C A, and Ahmed, J. (2020). Interprofessional collaboration for dental practice management education: is there a need?. The Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice. Available at: https://www.thejcdp.com/journal/aop/JCDP/1#

Van der Berg-Cloete, S. E., Snyman, L., Postma, T. C., and White, J. G. (2016). South African dental students' perceptions of most important non-clinical skills according to medical leadership competency framework. J. Dent. Educ. 80, 1357–1367. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2016.80.11.tb06221.x

Verma, M., Mohanty, V., and Talwar, S. (2018). D-CAST: enhancing communication skills among dental students. Med. Educ. 52:557. doi: 10.1111/medu.13551

Keywords: general practice dental, interprofessional education, practice management, curriculum, education dental

Citation: Sujir N, Naik DG, Mohammed CA, Jain A and Uppoor A (2024) Introducing dental practice management in the undergraduate curriculum through an interprofessional module: experience from an Indian dental school. Front. Educ. 9:1432823. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1432823

Edited by:

Nahla A. Gomaa, University of Alberta, CanadaReviewed by:

Huda Tawfik, Central Michigan University, United StatesDiane H. Quinn, Saint Joseph’s University, United States

Copyright © 2024 Sujir, Naik, Mohammed, Jain and Uppoor. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ciraj Ali Mohammed, Y2lyYWpAbnUuZWR1Lm9t

Nanditha Sujir

Nanditha Sujir Dilip G. Naik2

Dilip G. Naik2 Ciraj Ali Mohammed

Ciraj Ali Mohammed Animesh Jain

Animesh Jain Ashita Uppoor

Ashita Uppoor