- 1Department of Biochemistry and Biomedicine, School of Life Sciences, University of Sussex, Brighton, United Kingdom

- 2Department of Molecular Biosciences, The Wenner-Gren Institute, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden

COVID-19 has brought to light the systemic racism faced by ethnic minorities in the UK. During the pandemic, we saw an increase in anti-Asian hate crimes and a lack of support from the government given to both patients and healthcare workers from minority backgrounds on the front lines. This lack of support potentially contributed to the increased susceptibility of ethnic minorities to COVID-19 and also their hesitancy toward the vaccine, particularly the south Asian communities. In this paper we discuss potential reasons for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among south Asian groups. Additionally, we propose that introducing a decolonised curriculum in secondary school may enhance cultural awareness with historical context among the white British populations, allowing for more inclusion for south Asian communities. By exploring ways to decolonise specific subjects in the secondary curriculum, this paper aims to set out a guideline for teachers and education professionals on expanding secondary school pupils’ knowledge of racial issues and equality, to start the process of educating a new generation appropriately. We propose that decolonising the secondary school curriculum is a potential long-term solution to eradicating racism and discrimination.

1. Introduction

COVID-19 (Coronavirus disease 2019) is a disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, originating in Wuhan, China, with the first known case identified in December of 2019. Since then, this disease has spread worldwide and was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March of 2020. There have been over 251 million cases of COVID-19 worldwide and it has claimed the lives of over 5 million people to date with over 9 million of cases and approximately 143 thousand deaths in the UK (WHO, 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic has thus been a prevalent and ongoing event across the world and indeed the UK in the last 2 years as cases rose and fell through the first and second major waves. However, studies have shown that for south Asian communities in the United Kingdom in particular, the pandemic has been exceptionally taxing.

Public Health England (PHE) COVID-19 surveillance report presents cumulative data from 29 June 2020 to 29 September 2020 which states that 24.2% of all COVID-19 cases and 12.8% of all mortalities belonged to Asian/ Asian British people (PHE, 2020). Yet this group makes up only 7.5% of the total UK population, suggesting that the south Asian community in the UK has been disproportionally affected by this disease (Gov.uk, 2018). Furthermore, research has found that south Asian patients were 1.54 times as likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit as white ethnic patients even though they were on average younger in age. Additionally, the mortality rate of this population was 1.49 times higher than their white counterparts (Apea et al., 2021). The data is suggestive of major ethnic disparities which have been brought to light by COVID-19, these include biological factors, socio-economic conditions, educational and environmental factors. These factors contribute to the significant increased risk of infection and death faced by south Asian communities in the UK.

Compounding their increased susceptibility to COVID-19, south Asian communities in the UK currently face COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. The UK Household Longitudinal Study in 2020 showed that, after Black respondents with 71.8% unlikely to take up the vaccine, 42.3% of people from Pakistani and Bangladeshi (Asian or Asian British) backgrounds were unlikely or very unlikely to take the vaccine, whereas only 15.6% of white British people were hesitant (SAGE, 2020). With almost half of the south Asian population in the UK unwilling to take the vaccine, this paper will also consider the possible reasons for a collective reluctance of ethnic communities to have the COVID-19 vaccines, even though it could decrease cases and deaths. A major issue encompassing this vaccine hesitancy could potentially be the racism, xenophobia and prejudice faced by south Asian people both during recent events and throughout history (Corbie-Smith, 2021). Before and during the pandemic, ethnic communities have always been confronted with discrimination (Le et al., 2020). This systemic racism comes from a long history of colonialism and the resulting coloniality (Maldonado-Torres, 2007). However, surprisingly, the education system in the UK, particularly at secondary school level, does not teach the negative impacts of colonialism the British had worldwide. Therefore, it is important that in a multicultural society like the UK, the impacts that the colonial system had and continue to have today are taught. By having these taught, south Asian, and other minorities can develop trust in the system and white students can develop empathy and understanding of the south Asian experience. This paper will briefly explore how Britain’s history of colonialism, imperialism and expansionism has shaped its society today, and how a decolonised secondary school curriculum could ultimately reduce discrimination faced by the UK south Asian communities and build trust within the communities. These effects could augment future government-led intervention to improve national health such as vaccine uptake.

In this paper, we will be focusing on south Asian communities in the United Kingdom. The data provided by the UK Government on ethnicity facts and figures characterizes people of south Asian descent into the groups Bangladeshi, Indian and Pakistani with all other Asian statistics grouped as “Asian Other” (UK Government RDU, n.d.). This is reflected in the importance of the south Asian community as an immigrant group in the UK. Therefore, while many minority ethnicities have faced a history a racism and hardship in light of COVID-19, this paper will focus on south Asian communities in the UK.

2. Why are people from South Asian ethnic minorities more at risk of COVID-19 in the UK?

There are both biological and sociological factors that affect people of south Asian ethnicity’s susceptibility to COVID-19. The biological factors include lower vitamin D levels and higher rates of diabetes. These highlight the exceptional importance of vaccination in these communities. Whereas the sociological factors are much more varied and include careers, living conditions and access to health care.

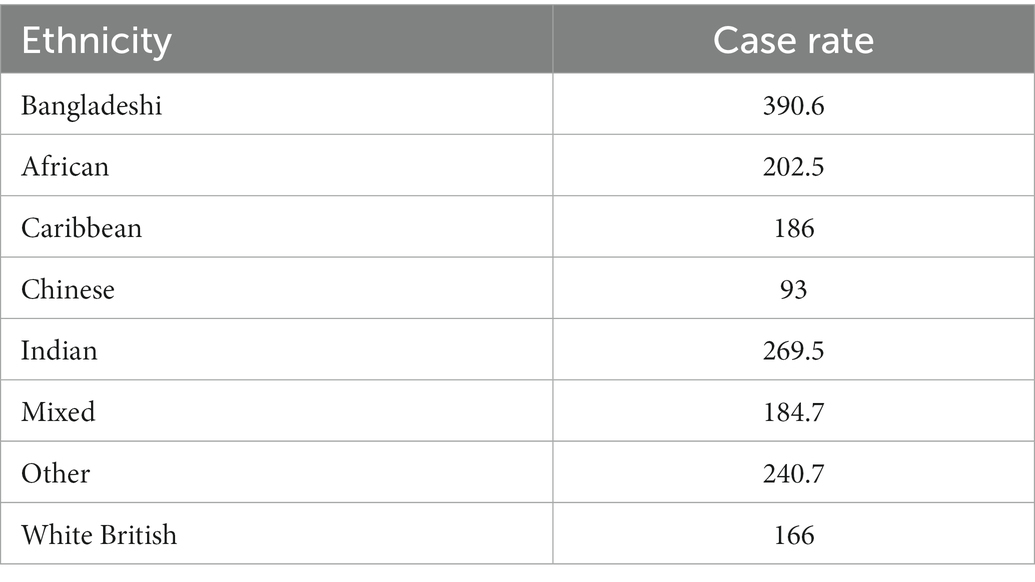

These risks are likely the cause of the significantly higher rate of COVID-19 case rate within the south Asian community (Table 1). People of Bangladeshi background had a 390.6 COVID-19 case rate per 100,000 people-weeks in the second wave of the pandemic and Indian ethnicity had 240.7 case rate. In comparison, people with white British backgrounds suffered a 166-case rate.

Table 1. COVID-19 case rates by ethnic group according to Public Health England categories in the second wave of the pandemic, England (case rate per 100,000 person-weeks) (Larsen et al., 2021).

Vitamin D levels tend to be low in south Asian population which implicates a higher risk of diabetes, heart disease and tuberculosis (Shaw, 2002; Martineau et al., 2017; Pardhan et al., 2020; Jayawardena et al., 2021). More relevantly, low Vitamin D is also associated with an increased susceptibility to upper respiratory tract infections, similar to that of COVID-19 (Martineau et al., 2017; Mitchell, 2020). Vitamin D plays a significant role in supporting the fight against infection by the production of antimicrobial agents in the respiratory system and also its ability to reduce the inflammatory response to such infection (Mitchell, 2020). This has led researchers to suggest that there is a strong connection between vitamin D levels and COVID-19 susceptibility (Martineau and Forouhi, 2020). In the early 2000s, there was a resurgence of vitamin D deficiency reported in south Asian children all over the UK (Shaw, 2002). As a result of this, south Asian populations in the UK during the pandemic are substantially more vulnerable to COVID-19 than their white counterparts due partially to their vitamin D deficiency.

Additionally, a common comorbidity of COVID-19 is diabetes mellitus. Studies have shown that there is evidence of increased severity and incidence of COVID-19 in patients with pre-existing diabetes (Singh et al., 2020). Diabetes is more prevalent in south Asian men and women than in white people (Simmons et al., 1989), as diabetes tends to develop at a younger age in south Asian populations (Ramachandran et al., 2010). Furthermore, diabetes induces a more severe case of COVID-19 in patients and even doubles the mortality risk due to negative pulmonary and cardiac involvement (Peric and Stulnig, 2020). Hence, diabetes contributes to the growing list of factors that ultimately causes people of south Asian descent to be more at risk of COVID-19.

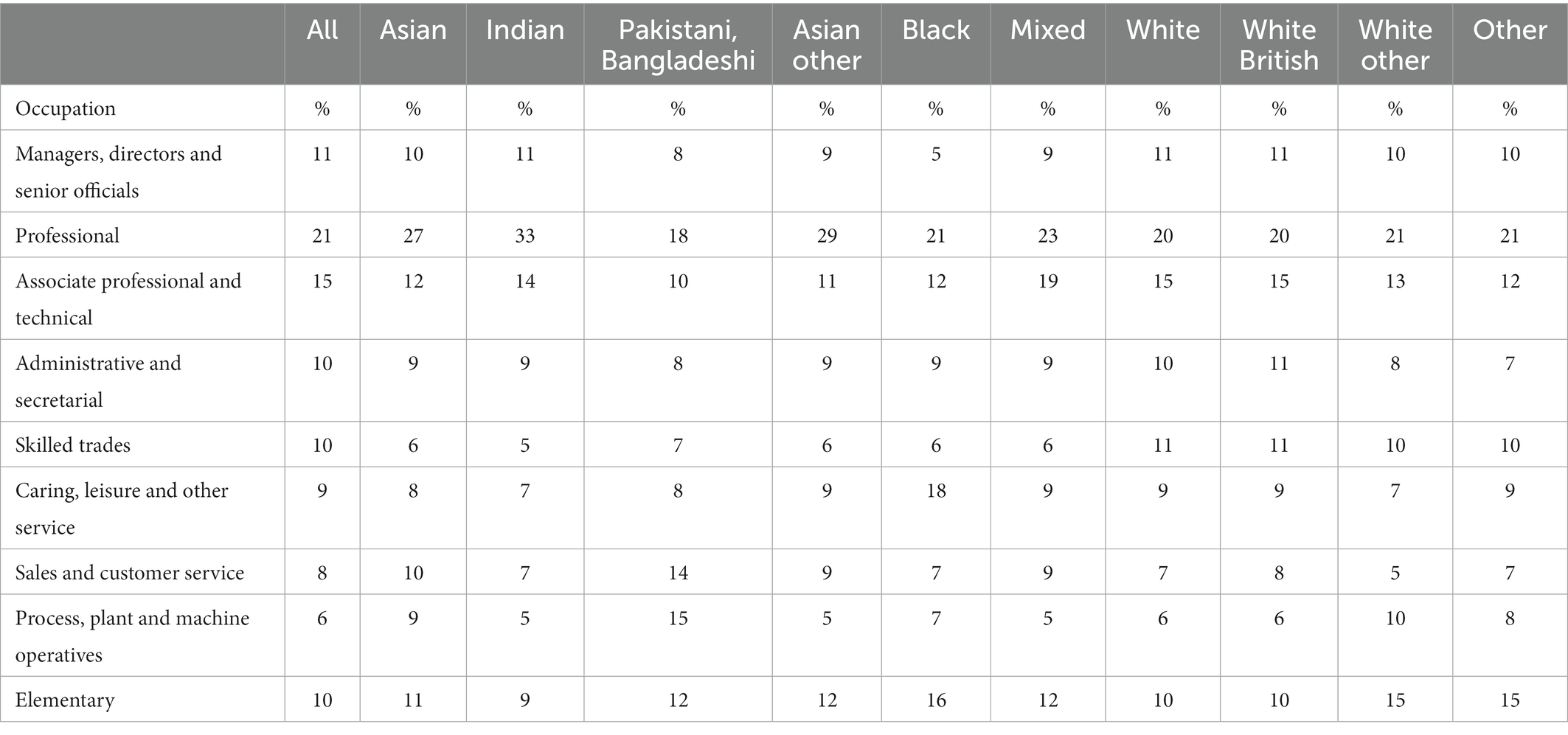

Although biological factors are significant in understanding south Asian people’s particularly high susceptibility to COVID-19, we must also consider the prevailing socio-economic conditions that surround and influence this topic. People of ethnic minorities tend to work in more “at-risk” jobs (Table 2) such as medical and dental practitioners, opticians, nurses and medical technicians (ONS, 2020a). For example, people from Asian backgrounds make up 27% of the professional workforce whereas white British accounts for 20%. Professional occupations include paramedics, nurses, and all kinds of health care professionals. Thus, especially in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, these occupations, especially medical practitioners, and nurses harbor the most risk of infection as they are to be in close contact with those who are infected every-day. These figures reflect that occupation had a drastic effect on the risk of contracting COVID-19 and that Asian people working in the frontlines were extremely at-risk.

Table 2. Percentage of workers in each ethnic group employed in different occupations UK, 2018 (Gov.uk, 2021a).

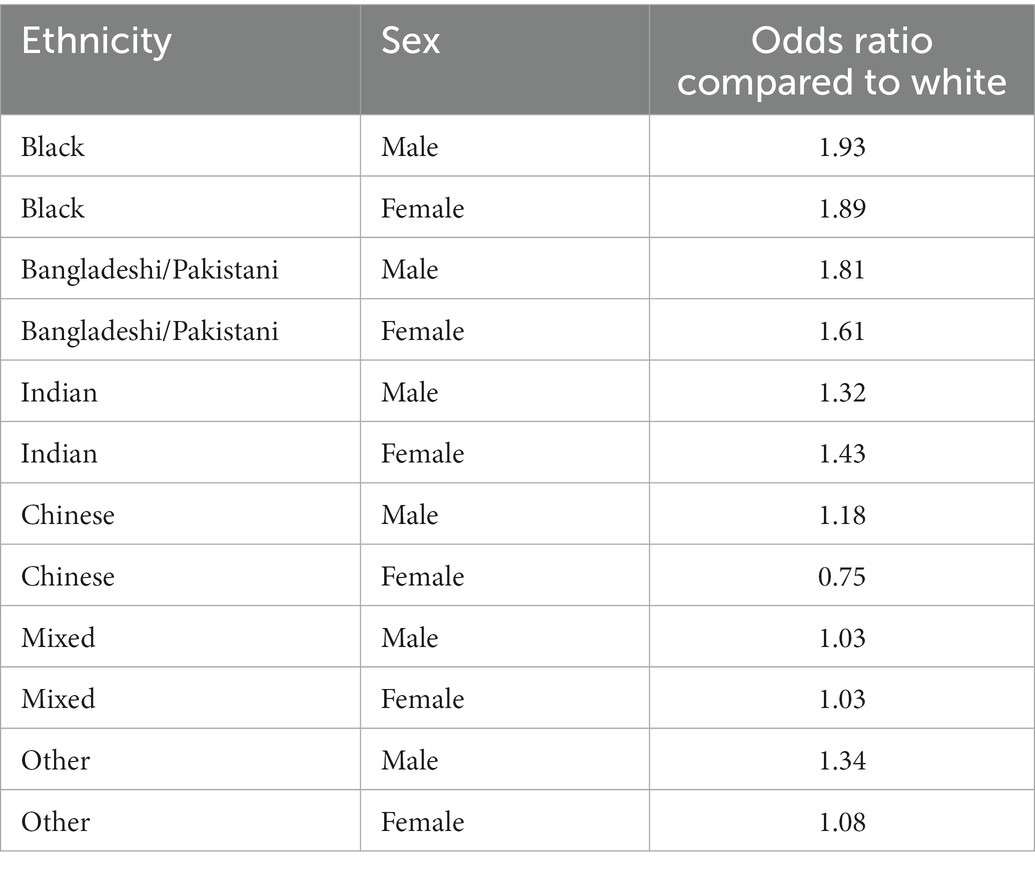

Another socio-economic factor that influences COVID-19 susceptibility are living conditions. Reports have shown that people over the age of 70 of south Asian descent are most likely to live in a multi-generational household (ONS, 2020b). During the UK national lockdown, vulnerable people such as those of old age were recommended to isolate. In south Asian multigenerational households, it would be more difficult to maintain isolation and uphold safety for those who are at risk, due to the combination of key workers and older vulnerable people living in close quarters. In the UK, ethnic communities are more likely to be based in urban, built up areas that are more deprived (ONS, 2018). This socio-economic factor has contributed to south Asian communities’ higher death rates from COVID-19 as reports have shown that COVID-19 has had a proportionally higher impact on the deprived areas of the UK (ONS, 2020c). This was also shown in Bangladesh where vaccine hesitancy was significantly high among unemployed population and people with lower or equal education level to high school (Ali and Hossain, 2021; Ali, 2022). Overall, socio-economic conditions play a significant part in increasing the likelihood of COVID-19 infection in south Asian people. In both their home and work environments, Asian communities are at a higher risk of contracting COVID-19. At home they face overcrowding, which hinders them from following social distancing guidelines. In the workplace, many have occupations in sectors such as caring, transportations, catering and security that cannot be performed at home meaning that they have to attend work, often on the front line, leading to an increased exposure to COVID-19 (PHE, 2020). Furthermore, as Table 3 shows, people of Asian descent are faced with a higher risk of death due to these various factors. People of Bangladeshi/Pakistani and Indian descent are on average 1.91 and 1.38 times, respectively, more likely to die of COVID-19 compared to those of white ethnicity. Biological, socio-economic, and environmental factors that influence the risk of COVID-19 infection and death in people of south Asian descent contribute to the health inequality faced by ethnic minorities in the UK.

Table 3. Risk of COVID-19 related death by ethnic group and sex in England and Wales (White and Nafilyan, 2021).

Furthermore, there is a concerning health gap in the UK for ethnic minorities (Szczepura, 2005). According to Raleigh and Holmes, people from ethnic minority groups in the UK are more likely to report poorer health and experiences using health services than their white counterparts (Raleigh and Holmes, 2021). This is further supported by statistics from the UK Government website for “Ethnicity facts and figures” where it is shown that east and south Asian ethnicities in particular had a lower-than-average percentage rate of reporting a positive experience for both primary care and hospital care (UK Government RDU, n.d.). This suggests that there could be unfair treatment of south Asian ethnic minorities and unequal access to health care in the UK for these people as in the same set of statistics, it was shown that they also had a lower-than-average percentage rate of reporting a positive experience making a GP appointment. If south Asian minorities are experiencing negative interactions while trying to access primary health care, it could be the cause of a significant health care gap in the UK. During COVID-19, this gap has become more prevalent, as many of the south Asian health care workers who contracted COVID-19 on the front lines could have been avoided. As senior clinicians in specialities from foreign countries such as countries in Asia have to temporarily work as junior front-line workers due to long approval times from the General Medical Council (GMC) to be registered (Chaudhry et al., 2020). Additionally, sources have stated that 64% of BAME (Black, Asian and minority ethnic) doctors in the UK have been pressured into working in the front line with inadequate PPE in comparison to 33% of white doctors (Cooper, 2020). This source has not provided a specific ethnic group breakdown. However, south Asian demographics are included in BAME groups. Therefore, a significant factor that contributes to an increased risk of COVID-19 in ethnic minorities such as south Asian is the systemic discrimination they are faced with. Having poorer access to health care as a patient and having unequal treatment as a health care worker is due to the ingrained racial prejudice in our society that could be the cause for them to be so at-risk in this pandemic.

3. Vaccine hesitancy and modern-day racism

Although the south Asian communities in the UK are one of the most at-risk ethnic groups for life long illnesses, they are the second most unwilling to be vaccinated in the UK (SAGE, 2020). Historically, ethnic minority groups are less likely to take vaccines in general in the UK (Razai et al., 2021). This is a significant issue especially during a global pandemic. The likely cause of such ethnic disparities in vaccine hesitancy is discrimination as well as both systemic and cultural racism (Razai et al., 2021). As COVID-19 originated in Wuhan, China, many individuals have placed the blame of the pandemic on those of East Asian origin. These individuals include people of significant power and influence such as Donald Trump who referred to COVID-19 as the “China virus” and “kung flu” (Jaworsky and Qiaoan, 2020; Jia and Lu, 2021). Often only epidemics and pandemics originating in non-white populated countries are proceeded by a period of extreme xenophobia. The Ebola epidemic in 2013 provides another example of disease being an excuse to augment existing racist and xenophobic views to the forefront of people’s minds (Kim et al., 2016).

People with political influence in the United States and Europe have promoted xenophobic expression in both verbal and the physical form. In 2020 there was a reported 300% increase in anti-Asian hate crime reports (Coates, 2020; Gover et al., 2020; Bahia, 2021; Gao and Sai, 2021; Haynes, 2021), with limited media coverage on this topic. Anti-Asian hate crime in the UK is perpetuated by a lack of action taken by the government and thus causes further distrust in the authorities by minority communities (Razai et al., 2021).

These patterns may extend a feeling of another generation of British-Asians feeling ostracized, unsafe, and underrepresented by their government. In light of this, how can these communities trust a vaccine program that is completely government run and controlled? The specific type of vaccine given to individuals is dictated by these government-led programs and is mostly dependent on accessibility, supply and region, which may contribute to inequalities (Campos-Matos et al., 2021). For instance, initially, UK National Health Service (NHS) national booking service, predominantly an online booking service available, was launched in English which meant that minority ethnic groups, particularly the first generation, may not have been able to access and book appointments (NHS, 2021; Watkinson et al., 2022). Although there were letters posted to patients and GPs inviting patients over telephone calls, the majority of vaccination appointments available were located in out of town in mass vaccination centers or hospital hubs, creating additional barriers to access the vaccines (Watkinson et al., 2022). When compared with seasonal flu vaccine uptake from 19/20, COVID-19 vaccine uptake was found to be significantly low among the most vulnerable Bangladeshi and Pakistani people living in the most deprived areas in the UK due to low trust and accessibility to the vaccination program, exacerbating pre-existing health inequalities in vaccine uptake (Watkinson et al., 2022).

A total of 90, 895 racially and religiously aggravated offenses were recorded in 2020/21 year in the UK, a rise of 12% from 2019/20 (Gov.uk, 2021b). Schumann and Moore investigated on how COVID-19 has affected racially motivated hate crimes in the UK where they conducted a victimization survey which was completed by a total of 393 East Asian, South Asian, Caribbean, and African individuals in the UK. Participants were asked whether since the first of February 2020, if they had experienced hateful comments or behavior which was believed to be racially motivated. They were further asked to clarify how many times they had been victimized since that date. They were also asked to provide a more detailed account of the crime (s) or incident (s). Finally, the participants were asked whether they had reported the crime/incident to the police and where it had happened. This study assessed accounts occurring on 1 February 2020 (before lockdown), 24 March - 13 May 2020 (during lockdown), and since 14 May 2020 (after lockdown). Findings showed that after the outbreak of COVID-19, ethnic communities such as south Asians, experienced a higher likelihood of hate crime victimization (Schumann and Moore, 2021), which correlated with low uptake of vaccines among these populations in the UK (SAGE, 2020). For instance, media portrayal of the “Indian variant” increased an anti-Indian sentiment among the population (Bahia, 2021). Racial hate crime incidents in the UK increased exponentially during April of 2020, when COVID-19 lockdowns were extended (Schumann and Moore, 2021). This was likely due to the government implementing a national lockdown in March of that year and proceeded to extend lockdown in April (IFG, 2021). This unprecedented event likely came as a shock to the UK public, causing uninformed individuals to channel their fear and displeasure into south Asian communities such as Indian community in Britain (Bahia, 2021).

Although it may seem anti-Asian hate crimes would decrease during national lockdowns when there is less interaction between individuals, it actually increased after lockdown was initiated (Schumann and Moore, 2021). This is due to technology’s impact on today’s society, as Williams et al. (2019) states, online hate speech is now widely recognized as a major social problem and is likely the form of many of the racial hate crimes reported (Williams et al., 2019). Hate speech can now be released in the form of messages and comments on various social media platforms, leaving south Asian communities unable to escape from the hate they face due to COVID-19. Thus, this pandemic has aroused deeply ingrained racist and xenophobic beliefs in the western public. Historic beliefs still play a significant part in modern day society. For example, the connection between race and disease comes from the 1800’s where people believed that races were biologically distinct and racial minorities were biologically and socially inferior (Gee et al., 2020). The ease and rapidity of Chinese people becoming the scapegoats of this pandemic is a prime example of the deep-rooted racism in western society; without reformation of the government or the public, it is inevitable that even positive scientific contributions from the government such as vaccines with the aim to combat the pandemic, will be subsequently met with doubt and criticism from the wronged communities.

A history of racism in the UK has ultimately led to the eventual distrust of the government by south Asian communities. As recent Asian hate crime events have shown, racial prejudice is embedded into western society and to fully understand how this came to be, we must first explore these views’ link to an imperialistic history. For south Asia, one of the most prevalent historical events was the century of exploitation and unfair trade by the East India Company that acted on behalf of British imperialism in India (Lawson, 2014). This event has influenced India’s history, even until recently, as they became independent from the United Kingdom only in 1947 (Chandra, 2000). A critical influence Britain’s rule had on India was that their cultural development was put on hold as the progression was infiltrated by western influences for nearly a century.

As south Asian communities in the UK are made up of mainly first- and second-generation immigrants (Dustmann et al., 2010), they either have these memories of the colonial transgressions fresh in their memory or have had family of a different generation inform them on these significant historical events to their culture. As these events are not widely discussed in the UK’s media, history books and education curriculum, this influential part of the country’s history is seemingly unaddressed (Taylor et al., 2021). Therefore, it suggests that the UK government does not deem these actions important enough to properly address and take accountability for. Ultimately, the actions of the leaders of the UK both historically and currently contributes to build significant distrust. In order to achieve successful vaccine uptake from south Asian ethnic communities, the government must address past wrongdoings in an attempt to build trust, confidence, and faith from the people.

Overall, a history of imperialism and racial prejudice from the colonial past has been ingrained into the minds of south Asian communities in the UK, and a subsequent distrust in the government in these communities feeling like they need to fend for themselves in both social and medical environments. This is demonstrated by health disparities. One example is the severe underrepresentation of ethnic minorities in recent COVID-19 research. People of white descent constituted 74–91% of participants in UK COVID-19 studies, leaving 9–24% representation for all ethnic minorities and therefore even less for south Asian minorities (Etti et al., 2021). In the past, this underrepresentation was due to systemic racism and white people being considered the standard of medical research. However, researchers are now highlighting the difficulty in recruiting for diverse studies and trials. Even when researchers are willing to diversify, south Asians are now often reluctant to participate due to the fear of discrimination, stemming from the same systemic racism (Hussain-Gambles et al., 2004; Ioannidis et al., 2021).

How can south Asian communities feel assured that the government offered vaccine has the same positive effects on them as they do on white people when the government itself has failed to properly represent them in vaccine trials? Moreover, the ongoing racism which are highlighted in media does very little to encourage south Asian communities to uptake government-led vaccine interventions. Initiatives such as “grab-a-jab,” where participants were asked to be vaccinated in walk-in centers, have demonstrated improvements in vaccine uptake from ethnic minorities however, we believe that more substantial, systemic changes need introducing to change this perception and to eliminate distrust on government (NHS, 2021).

The concerning health gap in the UK is also a potential problem in regard to vaccine hesitancy in south Asian communities. Modern day discrimination in health care is clear as south Asian ethnic minorities experience less-than-average patient satisfaction in hospital and primary health care (UK Government RDU, n.d.). With this underlying negative view of the British health care system, south Asian communities are more inclined to dismiss the COVID-19 vaccine in fear of having a negative experience and not being treated equally by the system. Furthermore, during this pandemic, ethnic minorities have been overlooked. For example, the UK National Health Service recently warned that the pulse oximeter device which is used to measure oxygen levels in COVID-19 patients by beaming light through the skin may not be as effective on darker skin tones (Fierce Biotech, 2021).

The oversight of the government and health services on issues such as this proves how inadequate they were on securing the safety of ethnic minorities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Oversights such as these perpetuates distrust in the government, especially on COVID-19 related matters such as the vaccine programs. Additionally, only recently has the UK approved China-manufactured Sinovac and India-manufactured Covaxin vaccines (Duffy, 2021). Previously, only people with one of four vaccines have been approved to be considered as fully vaccinated for travel. These includes the Janssen vaccine from the Netherlands, Moderna and Pfizer from the US, and AstraZeneca from the UK. More relevantly, the Astra Zeneca vaccine produced in India was considered suspect by the EU and the British public (Fierce Pharma, 2021). Disapproving of vaccines manufactured in countries that are from developing countries could reinforce ingrained discrimination. They have set an example to south Asian communities in the UK of the distrust and fear of vaccines made by non-western nations.

To tackle vaccine hesitancy, crucial changes need to be introduced in a sector such as the secondary education system as a way to tackle a systemic racist belief to target the minds of pupils in early education. It is important to educate learners from a young age to shape their view of the ethnic minority communities that they live alongside for enhanced social integration. Educating secondary school pupils, who will become integral members of society (e.g., government policy makers), in equality, diversity and inclusion through a decolonised curriculum could potentially ensure that everyone is treated fairly and with respect regardless of their ethnic origin. Focusing on early education and decolonising the secondary school curriculum could be a long-term solution, more substantial to our societal problems regarding systemic racism.

4. Decolonising the UK secondary school curriculum to tackle racism- a potential solution

Decolonising the curriculum is to not only start teaching the history of colonialism and targeting academics and teachers but to open a dialog to all members of society to help create a space for people to both learn and think about cultures and diversity. Opening up an environment where people can respect each other can help begin to rebuild both an education system and a society where everyone is supported and understood equally.

In late 2020, an official UK government and Parliament petition was made to “Teach Britain’s colonial past as part of the UK’s compulsory curriculum” (Petition 324,092) (Long et al., 2021). As stated in the details of the petition, currently, it is not compulsory for primary or secondary schools in the UK to teach Britain’s colonial past. However, teaching such topics in school’s curriculum can help educate pupils at a young age of the truth behind Britain’s historical power. The education system now showcases Britain’s past of being a strong nation and yet does not delve deeply into the exact reasons and their consequences. The curriculum focuses on Britain’s vision throughout history, lacking perspective on the consequences of certain historical decisions and not addressing injustices imposed by Britain during those times (Parsons, 2020).

Changes to the curriculum could involve alternative perspective accounts of historical events (Parsons, 2020). This can teach pupils to empathize with the ever-broadening multi-cultural side of history instead of learning to dehumanize ethnic minorities following the current curriculum. Learning to treat people of other races as equals at a young age is an important step to decreasing deeply conditioned racial prejudice in adult life. As we strive for eradicating racism and therefore hopefully making people of south Asian ethnic minorities feel safe enough to consider the vaccine program, we must start with education.

In regard to decolonising the secondary curriculum in the UK, having a secondary school curriculum that glorifies Britain’s past of colonialism and imperialism can be very damaging toward south Asian-British pupils’ perceptions of themselves. Knowledge of the real history behind their own countries and the struggle with Britain’s past imperialism tend to come from parents and family educating these learners. Having it overlooked in the UK history syllabus creates an unnecessary sense of divide between their country of origin and their country of residence from a young age. This perpetuates the idea that the UK must be somehow against them and their family, as these south Asian-British pupils are told by the curriculum that real hardships faced by their family/ancestors were not significant in British history. It is vital that the secondary school curriculum is targeted in particular as learners are beginning to learn about detailed parts of British history in which colonialism plays a significant part (DoE, 2013). If at this learning stage, the past actions of the British Empire are “white-washed,” there is a risk of normalizing racial prejudice at a young age.

To decolonise the curriculum is to teach Britain’s history in full, without skipping over the major events of colonialism and imperialism that had built up the British Empire. Furthermore, these events must be taught from a factual point of view, to recognize that the power Britain had often stemmed from oppression of others.

The Department of Education’s history key stage 3 (secondary school year 7 to 9) national curriculum in England states to aim to “gain and deploy a historically grounded understanding of abstract terms such as ‘empire’, ‘civilisation’, ‘parliament’ and ‘peasantry’” (DoE, 2013). A crucial step in aiding the curriculum is to add terms such as ‘colonialism’ into the syllabus alongside ‘empire’. The education system needs to open the usage of key words such as ‘colonialism’ to start the discussion of the morals and ethics surrounding Britain’s actions in history rather than glorifying them. Being open with Britain’s past, such as the events discussed in this paper, and considering the effects and outcome for the south Asian people in the curriculum can help promote empathy in learners. Whereas the current curriculum strongly depicts a sense of divide between Britain and Asian countries and also promotes a lack of empathy within white students, ultimately leading to many learners growing up internalizing the idea that systemic racism is acceptable.

It is clear that racism is a problem from a young age. From 2016 to 2021, UK schools reported more than 60,000 racist incidents (Batty and Parveen, 2021). Additionally, teachers of black and minority ethnic backgrounds also reported racism is a contributory factor to the underrepresentation in position of leadership in schools in England (Elonga Mboyo, 2017). Therefore, it seems necessary to start educating learners in these important historical events early in secondary education as well as embedding decolonisation in teachers’ training. Furthermore, it is important to represent every race in the classroom. As this source states, pupils of ethnic backgrounds are often taught about their own heritage by their parents and when their true versions of history they know clash with that of the school curriculum, it causes distress (BBC, 2020). By decolonising the curriculum, we are attempting to look at history from the viewpoint of other ethnic groups. This way of teaching may help represent pupils with minority ethnic backgrounds in the classroom and encourage them to learn accurate History of the interacting with non-Western cultures.

Another secondary subject that should be targeted in this curriculum change is geography. As Puttick and Murrey state, the word ‘race’ does not appear once in the Key stage 3 or GCSE geography curriculum (Anderson, 2021; Puttick and Murrey, 2021). As a subject that revolves around human activity such as anthropology, countries and therefore race, the absence of the word ‘race’ is shocking. Geography emerged as the science of European imperialism, in regards to exploration and colonial geography (De Rugy, 2020). Implicit racism can come from the observation in class that Europeans “discovered” lands and naming it their territory, without regard for the native inhabitants (Beck, 2021). The curriculum makes no effort to delve deeper into the ethics and consequences of this. In geography as well as history, the key to decolonising the curriculum is to teach from other perspectives and viewpoints.

Although there is a very little room in the secondary science curriculum to include topics on race and equality, many improvements could be adopted elsewhere to positively impact learners’ views on STEM subjects. For example, modules in history such as History of Medicine can promote learners’ understanding of the revolution of science and ethical aspects of medicine in different countries in the world and different cultural backgrounds. Currently, the syllabus consists of mainly Western medicine such as inoculations developed by Edward Jenner and the importance of Louis Pasteur (AQA, 2019). Modules such as this is a significant opportunity to teach about unethical science applied by westerners onto minority ethnic groups from their home countries. For example, secondary school students could be taught how discoveries of drugs and vaccines were trialed unethically on ethnic minorities. This is not only from history, such as the injection of asbestos into black prisoners by Pfizer in the 1970s, which recently came to light, but also more recent events. A prominent example is Pfizer’s unapproved trailing of an antibiotic trovafloxacin during a 1996 meningitis epidemic in Nigeria (Lenzer, 2006). These examples of recent historical events in medicine and science could allow for inclusion, empathy, and integration among pupils.

Another subject that can integrate the decolonisation of science is citizenship, which can help tackle the modern-day racial issues surrounding science. The specification of the current citizenship syllabus underlines the need for students to learn “the human, moral, legal and political rights and the duties, equalities and freedoms of citizens” (AQA, 2022). This subject can become a space for discussion to talk about current racial issues to both make ethnic minority students feel represented and heard and to educate sympathy and compassion in other students. These discussions and inclusion of the history of science is important as the science subjects are so full of facts and impartial information that racial issues get looked over.

This is a conundrum as science focused on major discoveries, which have occurred in the past, when the overwhelming majority of scientists were white males. For example, all pupils are taught in biology that Watson and Crick discovered the DNA helix, however there is no mention of James Watson’s racist and misogynistic viewpoints (Klug, 1968). Another key component that could be taught is eugenics and its influence within the education and societal systems. According to Galton, Eugenics is “the science which deals with all influences that improve the inborn qualities of a race; also with those that develop them to the utmost advantage”(Atherton and Steels, 2015). The effect of eugenics is ongoing and impacts our societal systems and educational policies (reviewed in (Lowe, 1998; Bessant, 2016)), which should be taught at secondary school. These views promoted by influential white males who dominate the British society still persist in today’s education system which need to be addressed and dismantled. Therefore, it can be other subjects such as history or citizenship that brings to light these racial issues in science, so that pupils can understand the underlying unfounded biases that men such as Watson exemplify.

The English literature subject can also be decolonised. As the current curriculum has mainly books and poems by white authors, there is room for literature by authors of other ethnicities and also to demonstrate the systematic system of oppression of non-Western peoples, whether it be in the colonial era or for their descendants who live in the United Kingdom today. However, even literature depicting day to day lives of south Asian or British south Asian people can be beneficial for students to learn about, as being able to see people of other ethnicities in normal stories at school can improve learners’ understanding of other cultures and how they live day to day life. This example can also be encouraged in areas outside of English literature, as in subjects such as citizenship and history where case studies are used to improve learning, these case studies can benefit by including a wider range of ethnicities. Reading and learning about a diverse range of perspectives in English can be extremely beneficial to learners as it opens up their minds to other points of view. This extends to the media that is used in English lessons, movies made by ethnic minorities or made about racial topics and historical events can also be advantageous as it is a great opportunity to introduce pupils to these concepts in an engaging format.

Encouragement of ethnic minority pupils into STEM fields and higher education is also important. This can be done by increasing funding for outreach programs for disadvantaged students and deprived areas. The University of Manchester operates a Black, Asian and minority ethnic program with the aim to reduce barriers between black and minority ethnic students and higher education (UoM, n.d.). This project also partners with schools, colleges, and community groups to inspire learners and celebrate black and minority ethnic achievements. More funding for programs such as this and more access to them for minority ethnic students can provide them with opportunities. To ensure this we can incorporate these programs with the secondary curriculum so that all ethnic minority pupils can have access to this. Overall, the new curriculum should teach students about both the history of ethnic minorities in different subjects and also their current affairs and achievements. This allows for inclusion, proper representation in the curriculum for students of ethnic minority backgrounds and also gives them access to programs to further develop themselves.

Decolonising the curriculum, education of learners in various subjects and actively promoting anti-racism in schools, leading to more adults supporting racial equality could have potentially saved south Asian people from harassment and hate-crime during this pandemic, which reinforced alienation from the broader British public. Furthermore, if immigrant south Asian communities were not faced with discrimination and received more support and recognition from the government and associated services, perhaps they would be more confident in up taking the COVID-19 vaccine. Decolonising the secondary school curriculum can help ensure that people of ethnic minorities in the UK will rest assured that their peers in the workplace, school and society are sufficiently educated in racial history. Furthermore, future members of the government can benefit from learning about ethnicities other than white from a young age, leading, potentially, to a government that promotes racial equality. From COVID-19 we have learnt how important government and social support for Asian ethnic minorities are. With this reform in secondary education, the aim is to ensure than in the event of another pandemic, ethnic minorities are supported by the government and society rather than racially targeted and blamed, allowing them to feel safe and trust necessary government-led schemes such as the COVID-19 vaccines.

More than just education, decolonisation is a means to end the cycle of prejudice and marginalization faced by ethnic minorities. For example, although the Tuskegee syphilis study, ended well before the 21st century, the underlying issue of treating ethnic minorities as ‘lesser’ people is still just as prevalent. Even though times have changed, and the scenarios ethnic minorities find themselves in are different throughout history, the underlying issues they face and the discrimination they must overcome in their lives remain. The racial disparities caused by unethical medical testing in history as well as present day racial discrimination has led to mistrust in present day medical research. For instance, Pfizer, a western pharmaceutical company, conducted a drug trial during meningitis outbreak in Nigeria in 1996 which resulted in numerous deaths (Lenzer, 2007). The trial was concluded illegal in a report leaked to the Washington Post in May 2006. As shown by a study conducted by Devlin et al., which concluded that racial discrimination while seeking medical care lowered the likelihood of patients’ participation in clinical trials (Devlin et al., 2020). Therefore, confirming that racial discrimination is still an ongoing and prevalent issue within the medical research sector. Furthermore, its effect on medical testing participation results in less ethnic minority representation in crucial modern-day clinical trials, which in turn causes a cycle of discrimination, as ethnic minority communities are then less likely to trust even a beneficial drug or vaccine that has little to no representation of their own race.

To decolonise is to create a society that no longer treats ethnic minorities as less valued members, where they can live free of the discrimination that were faced by their ancestors. We must overcome the idea that just because the situations and crimes are less extreme, that they are still just as prevalent in the eyes of the people who face them and should be taken seriously.

Decolonisation should be seen and treated as reaching equity rather than an extra step for the benefit of the minority. It’s a voice for the people who have been marginalized and should be viewed as the bare minimum to achieve true equality in society. As Gillborn’s analysis concludes, “the most dangerous form of ‘white supremacy’ is not the most obvious and extreme fascist posturing of small neo-Nazi groups, but rather the taken-for-granted routine privileging of white interests that goes unremarked in the political mainstream” (Gillborn, 2005).

Ultimately, decolonisation can undeniably benefit the lives of ethnic minorities, however, the true goal of decolonisation and achieving equality is to also enhance the knowledge and empathy of everyone in society and expose how colonialism has shaped the global south and impacted British society today. We can stride toward creating an environment where learners of different ethnicities can grow up with equal opportunities and not be pushed into a box, having their futures decided by their ethnic background. This society can also further reach true equality by first taking this first step of being inclusive of difference. We can already see the younger generations strong desire for this change. Meda brings to light university student’s demand for a decolonised curriculum, the study found that student’s views on decolonisation were “distinct, congruent and unambiguous” (Meda, 2020). This further emphasizes that society is ready to take on this challenge for change and that decolonisation is not a distant goal but something that can be achieved now.

However, there is resistance toward the decolonisation movement, as Hall et al. (2021) argue, institutions such as some universities in the UK still reinforce whiteness and dissipates radical energy (Hall et al., 2021). This also applies to secondary school where teachers are predominantly white (Lander, 2014; Katsha, 2022). This means that the systemic implementation of the decolonisation concept into education will be a long and trying process, however, this also implicates that the suggestion of facing this issue by targeting the young generation in hopes of invoking change in society as a whole may be the only solution. As learners notice race from a young age and the absence of dialog about race can allow stereotypes, biases, and racism to be reinforced (Lingras, 2021). Therefore, if the education system were to be reformed to adequately teach them about race and racism at this crucial age, the future generation will already have successfully implemented decolonisation into their society.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, COVID-19 has brought to light the systemic racism that is present against south Asian communities in today’s society. From the racial hate crimes due to fear of COVID-19 to the vaccine hesitancy among south Asian communities in the UK, there is a clear problem with the way ethnic minorities are perceived by both the public and the UK government. Decolonising the secondary curriculum can be the first step to achieving a racially equal society in the UK as it allows for early learning on cultural awareness. Although this will take a long time, it can enhance integration and compassion between white and black, asian and minority ethnic pupils from a young age and eventually lead to a society that is safe and understanding for all races. Further research into the exact curriculum changes needs to take place to fully restructure the secondary syllabus to include thorough representation of ethnic minorities in all taught subjects.

Author contributions

AH drafted the paper. TN critically reviewed and revised the paper. MP conceptualized, supervised, revised and critically reviewed the paper. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from Vetenskapsrådet (The Swedish Research Council) 2017–04663.

Acknowledgments

Dedicated to the memory of Stephen Hare, Structural biologist at the University of Sussex who was passionate about racial equality and diversity in science. We would also like to thank Daniel Akinbosede for our numerous ongoing discussion on this topic.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ali, M. (2022). What is driving unwillingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine in adult Bangladeshi after one year of vaccine rollout? Analysis of observational data. IJID Reg. 3, 177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ijregi.2022.03.022

Ali, M., and Hossain, A. (2021). What is the extent of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Bangladesh? A cross-sectional rapid national survey. BMJ Open 11:e050303. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050303

Anderson, N.. (2021). Decolonise Geography. Available at: https://decolonisegeography.com/blog/2021/02/why-do-we-need-to-decolonise-geography/

Apea, V. J., Wan, Y. I., Dhairyawan, R., Puthucheary, Z. A., Pearse, R. M., Orkin, C. M., et al. (2021). Ethnicity and outcomes in patients hospitalised with COVID-19 infection in East London: an observational cohort study. BMJ Open 11:e042140. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042140

AQA. (2022). Life in Modern Britain. Manchester, United Kingdom: AQA. Available at: https://www.aqa.org.uk/subjects/citizenship/gcse/citizenship-studies-8100/subject-content/life-in-modern-britain

AQA. (2019). Shaping the Nation: AA Britain: Health and the People: C1000 to the Present Day. Available at: https://www.aqa.org.uk/subjects/history/gcse/history-8145/subject-content/shaping-the-nation

Atherton, H. L., and Steels, S. L. (2015). A hidden history. J. Intellect. Disabil. 20, 371–385. doi: 10.1177/1744629515619253

Bahia, J. (2021). Indian Variant and Travel Bans: COVID-19 Warnings Should be Rooted in Science, not Anti-South Asian Racism: The Conversation. Available at: https://theconversation.com/indian-variant-and-travel-bans-covid-19-warnings-should-be-rooted-in-science-not-anti-south-asian-racism-160072

Batty, D., and Parveen, N.. (2021). UK Schools Record more than 60,000 Racist Incidents in Five Years. Race in Education.

BBC. (2020). Decolonising the Curriculum. BBC Bitesize. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/articles/z7g66v4

Beck, L. (2021). Euro-settler place naming practices for North America through a gendered and racialized lens. Terrae Incognitae 53, 5–25. doi: 10.1080/00822884.2021.1893046

Bessant, J. (2016). Tracing bio-political and eugenic connections in education and treatment of ‘youth problems’. Aust. J. Educ. 39, 249–264. doi: 10.1177/000494419503900303

Campos-Matos, I., Mandal, S., Yates, J., Ramsay, M., Wilson, J., and Lim, W. S. (2021). Maximising benefit, reducing inequalities and ensuring deliverability: prioritisation of COVID-19 vaccination in the UK. Lancet Reg. Health Europe 2:100021. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100021

Chaudhry, F. B., Raza, S., Raja, K. Z., and Ahmad, U. (2020). COVID 19 and BAME health care staff: wrong place at the wrong time. J. Glob. Health 10. doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.020358

Cooper, K. (2020). BAME Doctors Hit Worse by Lack of PPE. Tavistock Square, London: British Medical Association. Available at: https://www.bma.org.uk/news-and-opinion/bame-doctors-hit-worse-by-lack-of-ppe2020

Corbie-Smith, G. (2021). Vaccine hesitancy is a scapegoat for structural racism. JAMA Health Forum 2:e210434. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.0434

De Rugy, M. (2020). Geography in the Colonial Contex. Encyclopédie D'histoire Numérique de l'Europe. Available at: https://ehne.fr/en/encyclopedia/themes/europe-europeans-and-world/colonial-expansion-and-imperialisms/geography-in-colonial-contex

Devlin, A., Gonzalez, E., Ramsey, F., Esnaola, N., and Fisher, S. (2020). The effect of discrimination on likelihood of participation in a clinical trial. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 7, 1124–1129. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00735-5

DoE. (2013). History Programmes of Study: Key Stage 3. Department for Education. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/239075/SECONDARY_national_curriculum_-_History.pdf

Duffy, N. (2021). UK Travel Restrictions: Tourists with India and China-made Covid Vaccines no Longer have to Isolate on Arrival. News.

Dustmann, C., Frattini, T., and Theodoropoulos, N.. (2010). Ethnicity and Second Generation Immigrants in Britain. CReAM Discussion Paper No 04/10.

Elonga Mboyo, J. P. (2017). School leadership and black and minority ethnic career prospects in England: the choice between being a group prototype or deviant head teacher. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 47, 110–128. doi: 10.1177/1741143217725326

Etti, M., Fofie, H., Razai, M., Crawshaw, A. F., Hargreaves, S., and Goldsmith, L. P. (2021). Ethnic minority and migrant underrepresentation in Covid-19 research: causes and solutions. EClinicalMedicine 36:100903. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100903

Fierce Biotech. (2021). UK Launches Review of Racial, Gender Biases in Medical Devices, Sparked by Disproportionate COVID Deaths. Newton, MA: Fierce Biotech. https://www.fiercebiotech.com/medtech/uk-launches-review-racial-gender-bias-medical-devices-sparked-by-disproportionate-covid

Fierce Pharma. (2021). AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 Vaccine Faces Distrust in Europe, Even as it Gets Rave Reviews in Neighboring U.K., Survey Finds. Fierce Pharma. Available at: https://www.fiercepharma.com/marketing/yougov-poll-finds-distrust-astrazeneca-vaccine-europe

Gao, G., and Sai, L. (2021). Opposing the toxic apartheid: the painted veil of the COVID-19 pandemic, race and racism. Gend. Work Organ. 28, 183–189. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12523

Gee, G. C., Ro, M. J., and Rimoin, A. W. (2020). Seven reasons to care about racism and COVID-19 and seven things to do to stop it. Am. J. Public Health 110, 954–955. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305712

Gillborn, D. (2005). Education policy as an act of white supremacy: whiteness, critical race theory and education reform. J. Educ. Policy 20, 485–505. doi: 10.1080/02680930500132346

Gov.uk. (2018). Population of England and Wales. Available at: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/uk-population-by-ethnicity/national-and-regional-populations/population-of-england-and-wales/latest

Gov.uk. (2021a). Employment by Occupation. Office for National Statistics. Available at: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/work-pay-and-benefits/employment/employment-by-occupation/latest

Gov.uk. (2021b). Official Statistics. Hate Crime, England and Wales, 2020 to 2021. Crime JaL, Home Office. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/hate-crime-england-and-wales-2020-to-2021/hate-crime-england-and-wales-2020-to-2021

Gover, A. R., Harper, S. B., and Langton, L. (2020). Anti-Asian hate crime during the COVID-19 pandemic: exploring the reproduction of inequality. Am. J. Crim. Justice 45, 647–667. doi: 10.1007/s12103-020-09545-1

Hall, R., Ansley, L., Connolly, P., Loonat, S., Patel, K., and Whitham, B. (2021). Struggling for the anti-racist university: learning from an institution-wide response to curriculum decolonisation. Teach. High. Educ. 26, 902–919. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2021.1911987

Haynes, S. (2021). ‘This Isn't just a Problem for North America. The Atlanta Shooting Highlights the Painful Reality of Rising Anti-Asian Violence around the World, Race. TIME Newsletter.

Hussain-Gambles, M., Leese, B., Atkin, K., Brown, J., Mason, S., and Tovey, P. (2004). Involving south Asian patients in clinical trials. Health Technol. Assess. 8, 1–109. doi: 10.3310/hta8420

IFG. (2021). Timeline of UK Government Coronavirus Lockdowns and Measures, March 2020 to December 2021. Institute for Government. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/charts/uk-government-coronavirus-lockdowns

Ioannidis, J. P., Powe, N. R., and Yancy, C. (2021). Recalibrating the use of race in medical research. JAMA 325, 623–624. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.0003

Jaworsky, B. N., and Qiaoan, R. (2020). The politics of blaming: the narrative Battle between China and the US over COVID-19. J. Chin. Polit. Sci. 26, 295–315. doi: 10.1007/s11366-020-09690-8

Jayawardena, R., Jeyakumar, D. T., Francis, T. V., and Misra, A. (2021). Impact of the vitamin D deficiency on COVID-19 infection and mortality in Asian countries. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 15, 757–764. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.03.006

Jia, W., and Lu, F. (2021). US media’s coverage of China’s handling of COVID-19: playing the role of the fourth branch of government or the fourth estate? Glob. Media China 6, 8–23. doi: 10.1177/2059436421994003

Katsha, H. (2022). Most English School Kids will only ever be taught by White Teachers. New York: The Huffingtonpost.

Kim, H. S., Sherman, D. K., and Updegraff, J. A. (2016). Fear of Ebola. Psychol. Sci. 27, 935–944. doi: 10.1177/0956797616642596

Klug, A. (1968). Rosalind Franklin and the discovery of the structure of DNA. Nature 219, 808–810. doi: 10.1038/219808a0

Lander, V. (2014). “Initial teacher education: the practice of whiteness” in Advancing Race and Ethnicity in Education. eds. C. Schmidt and J. Chneider (Berlin: Springer), 93–110.

Larsen, T., Bosworth, M., and Nafilyan, V.. (2021). Coronavirus (COVID-19) Case Rates by socio-demographic characteristics, England: 1 September 2020 to 25 July 2021. Office for National Statistics. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/coronaviruscovid19caseratesbysociodemographiccharacteristicsengland/1september2020to25july2021

Le, T. K., Cha, L., Han, H.-R., and Tseng, W. (2020). Anti-Asian xenophobia and Asian American COVID-19 disparities. Am. J. Public Health 110, 1371–1373. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305846

Lenzer, J. (2006). Secret report surfaces showing that Pfizer was at fault in Nigerian drug tests. BMJ 332:1233. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7552.1233-a

Lenzer, J. (2007). Nigeria files criminal charges against Pfizer. BMJ 334:1181. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39237.658171.DB

Lingras, K. A. (2021). Talking with children about race and racism. J. Health Serv. Psychol. 47, 9–16. doi: 10.1007/s42843-021-00027-4

Long, R., Roberts, N., and Kulakiewicz, A.. (2021). Black History and Cultural Diversity of the Curriculum. House of Commons Library. Available at: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CDP-2021-0102/CDP-2021-0102.pdf

Lowe, R. (1998). The educational impact of the eugenics movement. Int. J. Educ. Res. 27, 647–660. doi: 10.1016/S0883-0355(98)00003-2

Maldonado-Torres, N. (2007). On the coloniality of being: contributions to the development of a concept. Cult. Stud. 21, 240–270. doi: 10.1080/09502380601162548

Martineau, A. R., and Forouhi, N. G. (2020). Vitamin D for COVID-19: a case to answer? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 8, 735–736. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30268-0

Martineau, A. R., Jolliffe, D. A., Hooper, R. L., Greenberg, L., Aloia, J. F., Bergman, P., et al. (2017). Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory tract infections: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ 356:i6583. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6583

Meda, L. (2020). Decolonising the curriculum: Students' perspectives. Afr. Educ. Rev. 17, 88–103. doi: 10.1080/18146627.2018.1519372

Mitchell, F. (2020). Vitamin-D and COVID-19: do deficient risk a poorer outcome? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 8:570. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30183-2

NHS. (2021). Book or Manage a Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccination. United Kingdom: National Health Service: National Health Service. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronavirus-covid-19/coronavirus-vaccination/book-coronavirus-vaccination/

NHS. (2021). NHS COVID “Grab-a-Jab” Initiative Boosts Ethnic Minority Vaccinations NHS England. England: NHS England. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/2021/08/nhs-covid-grab-a-jab-initiative-boosts-ethnic-minority-vaccinations/

ONS. (2018). Regional Ethnic Diversity. United Kingdom: Office for National Statistics. Available at: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/uk-population-by-ethnicity/national-and-regional-populations/regional-ethnic-diversity/latest

ONS. (2020a). Why have Black and South Asian People been Hit Hardest by COVID-19? Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/articles/whyhaveblackandsouthasianpeoplebeenhithardestbycovid19/2020-12-14

ONS. (2020b). Coronavirus (COVID-19) Roundup, 13 to 17 July 2020. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/articles/coronaviruscovid19roundup13to17july2020/2020-07-17#multigenerational-households

ONS. (2020c). Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection Survey: Characteristics of People Testing Positive for COVID-19 in England: October 2020. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/articles/coronaviruscovid19infectionsinthecommunityinengland/october2020

Pardhan, S., Smith, L., and Sapkota, R. P. (2020). Vitamin D deficiency as an important biomarker for the increased risk of coronavirus (COVID-19) in people from black and Asian ethnic minority groups. Front. Public Health 8:613462. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.613462

Parsons, C. (2020). A curriculum to think with: British colonialism, corporate kleptocracy, enduring white privilege and locating mechanisms for change. J. Crit. Educ. Policy Stud. 18, 196–226.

Peric, S., and Stulnig, T. M. (2020). Diabetes and COVID-19. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 132, 356–361. doi: 10.1007/s00508-020-01672-3

PHE. (2020). The Weekly Surveillance Report in England. Weekly Data: 23 September 2020 to 29 September 2020. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/923665/COVID19_Weekly_Report_30_September_2020.pdf

PHE. (2020). Disparities in the Risk and Outcomes of COVID-19. England: Public Health England. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/908434/Disparities_in_the_risk_and_outcomes_of_COVID_August_2020_update.pdf

Puttick, S., and Murrey, A. (2021). Confronting the deafening silence on race in geography education in England: learning from anti-racist, decolonial and black geographies. Geography 105, 126–134. doi: 10.1080/00167487.2020.12106474

Raleigh, V., and Holmes, J. (2021). The Health of People from Ethnic Minority Groups in England. The Kings Fund. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/health-people-ethnic-minority-groups-england

Ramachandran, A., Wan Ma, R. C., and Snehalatha, C. (2010). Diabetes in Asia. Lancet 375, 408–418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60937-5

Razai, M. S., Osama, T., McKechnie, D. G. J., and Majeed, A. (2021). Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy among ethnic minority groups. BMJ 372:n513. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1138

SAGE. (2020). Factors Influencing COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake among Minority Ethnic Groups. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/factors-influencing-covid-19-vaccine-uptake-among-minority-ethnic-groups-17-december-2020

Schumann, S., and Moore, Y.. (2021). The COVID-19 outbreak as a trigger event for sinophobic hate crimes in the United Kingdom. Br. J. Criminol. 2022:azac015. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azac015

Shaw, N. J. (2002). Vitamin D deficiency in UK Asian families: activating a new concern. Arch. Dis. Child. 86, 147–149. doi: 10.1136/adc.86.3.147

Simmons, D., Williams, D. R., and Powell, M. J. (1989). Prevalence of diabetes in a predominantly Asian community: preliminary findings of the Coventry diabetes study. BMJ 298, 18–21. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6665.18

Singh, A. K., Gupta, R., Ghosh, A., and Misra, A. (2020). Diabetes in COVID-19: prevalence, pathophysiology, prognosis and practical considerations. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 14, 303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.004

Szczepura, A. (2005). Access to health care for ethnic minority populations. Postgrad. Med. J. 81, 141–147. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.026237

Taylor, M., Hung, J., Che, T. E., Akinbosede, D., Petherick, K. J., and Pranjol, M. Z. I. (2021). Laying the groundwork to investigate diversity of life sciences Reading lists in higher education and its link to awarding gaps. Educ. Sci. 11:359. doi: 10.3390/educsci11070359

UK Government RDU. (n.d.). Health, Ethnicity Facts and Figures. Available at: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/health

UoM. (n.d.). The Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Programme. The University of Manchester. Available at: https://www.manchester.ac.uk/connect/teachers/students/widening-participation/bame-programme

Watkinson, R. E., Williams, R., Gillibrand, S., Sanders, C., and Sutton, M. (2022). Ethnic inequalities in COVID-19 vaccine uptake and comparison to seasonal influenza vaccine uptake in greater Manchester, UK: a cohort study. PLoS Med. 19:e1003932. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003932

White, C., and Nafilyan, V.. (2021). Coronavirus (COVID-19) Related Deaths by Ethnic Group, England and Wales: 2 march 2020 to 10 April 2020. Office for National Statistics. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/articles/coronavirusrelateddeathsbyethnicgroupenglandandwales/2march2020to10april2020

WHO. (2021). Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Geneva: World Healyth Organization. Available at: https://covid19.who.int/table2021

Keywords: vaccine hesitancy, racism, discrimination, decolonisation, secondary school curriculum

Citation: Hu A, Nissan T and Pranjol MZI (2023) Reflecting on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among South Asian communities in the UK: A learning curve to decolonising the secondary school curriculum. Front. Educ. 8:979544. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.979544

Edited by:

Zhiwen Hu, Zhejiang Gongshang University, ChinaReviewed by:

Mohammad Ali, La Trobe University, AustraliaRonicka Mudaly, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Copyright © 2023 Hu, Nissan and Pranjol. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tracy Nissan,  tracy.nissan@su.se; Md Zahidul Islam Pranjol,

tracy.nissan@su.se; Md Zahidul Islam Pranjol,  z.pranjol@sussex.ac.uk

z.pranjol@sussex.ac.uk

Anqi Hu

Anqi Hu