- Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership, University of Maryland, College Park, College Park, MD, United States

For Black girls, whose histories are often taught in schools through deficit-based narratives, the need to create and reauthor their personal and communal stories is a resistant act that gives their stories permanence in the present and the future. This article explores how Black girls leveraged creative expression to freedom dream in a virtual summer arts program. Theoretically grounded in Abolitionist Teaching and Critical Race Feminism, this study explored eight adolescent Black girls’ (co-researchers) experiences in Black Girls S.O.A.R. (scholarship, organizing, arts, and resistance), a program aimed to co-create a healing-centered space to engage artistic explorations of history, storytelling, Afrofuturism, and social justice with Black girls. The study utilizes performance ethnography to contend with the following research question: (1) How, if at all, do adolescent Black girls use arts-based practices (e.g., visual art, music, hair, and animation) to freedom dream? Analyses of the data revealed that co-researchers used arts-based practices to reclaim personal and historical narratives, dream new worlds, and use art as activism. In this, co-researchers created futures worthy of Black girl brilliance—futures where joy, creativity, equity, and love were at the center. I conclude with implications for how educators and researchers can employ creative, participatory, and arts-based practices and methodologies in encouraging and honoring Black girls’ storytelling and dream-making practices.

Introduction

Black is ignorance and it is laziness.

Black is a ghetto mess and a whole lot of trouble.

Blackness is a threat and it is something you should fear. To be Black is to be the worst version of a human being.

I’m sorry, I fear I was mistaken before.

To be Black is everything.

Blackness is power and knowledge.

It is beauty and strength.

To be Black is a blessing because Blackness is greatness.

I rewrote their story and you can too.

Be proud of your Blackness and all of its glory because Blackness is a part of you.

Olivia, Black Girls S.O.A.R co-researcher

The Zoom room grew quiet as Olivia unmuted herself. Her loved ones’ and peers’ faces filled the virtual tiles – a group of Black women and girls coming together in celebration of the artwork a team of Black girl co-researchers constructed over the span of a few months. Olivia’s voice reverberated as she boomed the first line of her original poem. With every line, she spat out the words until she got to the row, “I’m sorry, I fear I was mistaken before.” She cleared her throat and her tone changed. “I rewrote their story and you can, too.”

Olivia’s poem is an expression and enactment of how Black girls use art to write, create, and reclaim their stories. As science fiction author and ancestor Octavia Butler said, “Every story I create, creates me. I write to create myself.” Olivia illustrates what it means to craft a narrative about who she is, but also asserts who she is not. She rewrites a deficit-based narrative, but also poses a resounding call-to-action for educators, “You can, too.” She let that line linger in the air with a deep breath. She laid bare the hatred and fear tactics to evoke an emotional stir. Olivia makes it plain for anyone who will listen that these are the messages she receives from society and at school. As she sang her last line, the chatbox erupted with affirmations. The screen lit up with fire emojis and clapping emojis. She grinned and accepted the applause as she murmured, “Thank you for the love.” As part of the Black Girls S.O.A.R. (scholarship, organizing, arts, and resistance) virtual summer program, Olivia penned this powerfully lyrical piece.

What does it mean to center a liberatory curriculum where Black girls can refute harmful messages they have heard, and instead, posit their own narratives that highlight the brilliance, creativity, and freedom dreams that Black girls hold? How can we hold space for Black girls to rewrite the harmful stories they get told too often, and make their stories the definitive ones? How do we make it so Black girls do not have to rewrite, but simply create their own narratives? What new worlds are Black girls dreaming and building into existence? How can educators support those visions? These are the questions that guide me in this work.

Black girls are brilliant, creative, and intuitive. They are already dreaming new worlds through their artwork and creations, but also through their existence. Reynolds (2019) reminds us that “Black girls are curators, leaders, artists, freedom fighters, but most are Black girls – beautiful, complicated, magical, and survivors” (p. 11). However, “rarely is Black creativity centered in empirical literature or facilitated within educational environments” (Mims et al., 2022, p. 135). This article explores how Black girls leveraged creative expression to freedom dream their stories in both the present and the future by answering the question: “How, if at all, do adolescent Black girls use arts-based practices (e.g., visual art, music, hair, animation) to freedom dream?”

Theoretical framework

Abolitionist teaching

Freedom dreaming in education requires an abolitionist orientation. Abolition, in its most foundational definition, is about dismantling a structure, system, or institution. While historically applied to the abolishment of enslavement, current abolitionists apply the term to the praxis of eliminating imprisonment, policing, and surveillance, while creating alternatives committed to community-constructed safety (Critical Resistance, 2020). The prison industrial complex regards humans as disposable and as problems to be dealt with, rather than grappling with the failures of systems to provide necessary support for individuals and collectives to survive. Abolition is not solely about tearing down systems, like the prison industrial complex, but dreaming and enacting something new and more just in its place (Gilmore, 2021). Further, the new structures abolitionists are building center those who have been pushed to the margins. The call for abolition is not new, rather it is rooted in the work and love of Black, Brown, queer, and women revolutionaries who have always imagined and forged new horizons. In particular relevance to this study that explores Black girls’ art-making and freedom dreaming, Hartman (2020) described that Black feminist poetry has provided a roadmap for abolition. For example, Lorde (1984) named,

Poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action (p. 37).

This quote links the necessary nature of art to being able to not only dream new futures, but take action to craft them. Building on the legacy of abolition work, abolitionist teaching as a framework applies future dreaming to pedagogy and education. Love’s (2019) conceptualization of abolitionist teaching poses a call-to-action to dismantle current schooling structures and build more human-centered ones. The premise is that schools operate exactly how they were formed – to further colonization through conformity and obedience to maintain an inequitable system.

Institutions, such as schools, do not need to be reformed but instead replaced because they were built with harm at the center. As Stovall (2018) named, “school” abolition is about “teachers who dared to imagine another space for their students and engaged a process to build it” (p. 52). Abolitionist teaching and Stovall’s (2018) notion guided the decision to explore an out-of-school program to pose an opportunity to look beyond the current structure of schooling and create something outside of current confines of K-12. Through Black Girls S.O.A.R., I sought to create an alternative to traditional schooling spaces, where Black girls’ creativity was centered and truth-telling was a cornerstone of the curriculum.

Abolitionist teaching can take many forms. Love names that educators can create “safe space or homeplace in their classrooms, fight standardized testing, restore justice in their curriculum, or seek justice in their own communities.” Scholars have explored abolitionist teaching in a number of ways, including in civics education (Dozono, 2022), language arts and literacy in an urban school district (Hoffman and Martin, 2020), STEM (Jones and Melo, 2020; Louis and King, 2022), and teacher education (Faison and McArthur, 2020; Riley and Solic, 2021; Sabati et al., 2022). These studies helped me to think expansively about my role in the revolution as a striving practitioner of abolitionist teaching, as well as view abolitionist teaching from both a theoretical and conceptual lens. Rodríguez (2010) noted, abolition is a “perpetually creative and experimental pedagogy.” (p. 15). Love (2019) warned educators to not fall trap to gimmicks or quick fixes in education, but rather embed themselves in and be guided by the North Star that frameworks like Critical Race Theory (CRT) offer. To put abolitionist teaching into practice in this study, the program required a creative curriculum, but also creativity in how it was structured as to not simply reproduce in repackaged ways the same harms I sought to disrupt. It is in this vein that I incorporate Critical Race Feminism into the framework. Critical Race Feminism grounds abolitionist teaching, particularly in explicitly naming the need to abolish racist, sexist, heteropatriarchal systems, centering Black girls’ counter-stories, and ensuring intersectionality.

Critical race feminism

Critical Race Theory involves “a collection of activists and scholars interested in studying and transforming the relationship among race, racism, and power” (Delgado and Stefancic, 2001, p. 2). As a framework, it was coined in the 1970s by legal scholars and activists to acknowledge the permanence of racism in the United States (Bell, 1995). CRT acknowledges race as a socially constructed concept which works to maintain the dominance of whiteness to perpetuate social, economic, and legal inequality. It acknowledges that racism is more than individual bias and prejudice, but rather is embedded into the foundation of societal structures (Crenshaw, 1991). CRT allowed me to root this study in the salience of racism in education. Additionally, there are a few particular tenets that rest CRT in this study: the examination of intersectionality and the power of counter-storytelling as an act of freedom-dreaming and resistance.

Critical Race Theory scholar Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality to describe the inequality that individuals experience at multiple levels in the intersections between their multiple, oppressed identities (Crenshaw, 1991). Black feminist scholars, such as Anna Julia Cooper, Patricia Hill Collins, and Barbara Smith also centered their work around the intersections of Blackness and womanhood. Anna Julia Cooper considered Black women are “doubly enslaved” because of their multiple, oppressed identities (Moody-Turner, 2009). Frances Beal coined the term “double jeopardy” in 1969 to describe these oppressions as being different from Black men or white women. Their “both/and” worldview from the lens of race, class, and gender creates new possibilities and solutions for dismantling oppressive structures and offers new insights about the potential of society when white, cisheteropatriarchy is not centered as the norm. Black feminism is centered in the present study to recognize the intersections of oppression that Black girls experience at the intersections of their multiple, oppressed identities.

Critical race feminism, rather than feminism, is used to acknowledge the troubled history Black women have with the feminist movement, which often rendered experiences of racism to the margins (Crenshaw, 1989; Collins, 1990; Evans-Winters and Esposito, 2010). Feminism has often been dominated by the interests of middle-class white women. Critical race feminism attends to how Black women have experiences at the intersections of racism and sexism, and other forms of oppression.

To more fully understand the complexities and nuances of Black girls’ dreaming practices that are impacted by these intersections, counter-storytelling offers an opportunity for Black girls to not only name the harms of structures and systems of oppression, but speak back to them. Counter-storytelling has been used as a method of centering the stories of those whose knowledge has not been privileged and as a mechanism for challenging white supremacy (Solórzano and Yosso, 2002). The practice of counter-storytelling, “strengthen(s) traditions of social, political, and cultural survival and resistance” (Solórzano and Yosso, 2002). African women have long used storytelling to preserve cultural knowledge and give voice as a form of counter-narrative in and of itself, as it offers a counter to their present reality.

Taken together, abolitionist teaching and Critical Race Feminism acknowledge that racism is ingrained in structures and systems, namely the schooling process. For Black girls to be able to freedom dream, we must acknowledge why they must freedom dream in the first place. Also, we must reckon with what needs to be abolished, as understanding structural and systemic oppression is critical to activism. We cannot push back against what we do not know constrains us. Black girls use art to confront the truths of their experiences, but they also use art to tell stories of a world anew.

Literature review

Afrofuturism

In 1993, cultural critic Mark Dery coined the term Afrofuturism to speak to how the erasure of Black history is tied to how Black people aim to make sense of the Black political present by imagining alternate worlds. Specifically, Afrofuturism contends with the possibility of Black communities being able to imagine futures amid white violence and erasure. The legacy of enslavement lives through state-sanctioned violence, particularly against Black bodies, minds, and spirits (Warren and Coles, 2020). We see this happen through the “spirit murdering” of Black children in schools in the form of whitewashed curricula and pedagogy, the presence of police in schools, and policing policies and practices (Love, 2016). However, in Ohito’s (2020) words, “Yet we breathe life into this place, having manufactured methods to refuse elimination from the white world” (p. 193). In that vein, 20 years ago, the Dark Matter anthology was published, which was the first anthology that highlighted Black writers in sci-fi. Black writers and artists have always created new possibilities, alongside new worlds. Art-making and freedom-dreaming practices are refusals of being eliminated – we breathe life through artwork.

While this violence continues to occur at multiple levels in society, theorists of Black Livingness (McKittrick, 2021; Quashie, 2021) point us to something that counters erasure – Black aliveness as antithetical to Black inhumanity, which highlights freedom dreams, joy, and a future where Black people can simply exist. I join the scholars who do not limit Black girls’ lives to survival, but orient our hearts to engaging in Afrofuturistic visioning.

Black women artists have leveraged Afrofuturism in their work as a means of writing themselves and their existence into the future. To see Black girls and women in the future is an act of resistance. Particularly, using art as a form of not only defiance but as a tool for creating new ways of understanding the world subverts how oppressive structures and systems enact violence as a form of erasure on Black girls. As Toliver (2021a) wrote, “Afrofuturism can act as an experiential portal that guides readers to reflect on the current state of the world and to challenge any possible future or realm that attempts to ignore the existence of Black people.” (p. 2). To illustrate how Afrofuturism acts as a portal, Janelle Monáe’s albums introduce fans to the land of Metropolis, where androids work to escape enslavement from humans. Monáe’s alter-ego, Android 57821, otherwise known as Cindi Mayweather, runs from hunters after breaking the ultimate law, falling in love with a human. However, Mayweather was born to incite a rebellion and uses the underground as a place for rebellious expression where music and dance free android’s souls (Romano, 2018). Through the process of creating the story, Monáe creates herself by tapping into the history of her ancestors and reclaiming her power to seize freedom for the future. This type of “radical speculation enables us to imagine futures, reclaim histories, and create alternate realities” (Gunn, 2019, p. 16). Visual storytelling like this depict Black people in a fantasy realm and evoke the supernatural. It shows how Black people name historical harms and design alternate futures.

As illustrated through Monáe’s work, art is a portal through which Black people “imagine and develop their futures” (Boyd Acuff, 2020, p. 15). Toliver’s (2021b) work directly shows how Black girls do this. The Black girl writers in the study use agitation literacies, or literacies that directly disturb racism and other oppressions, as a strategy to resist and incite action from others (Muhammad, 2019). Some girls write how their characters do not engage in retaliation and violence because they have had enough, while others write their characters as engaging coalition-building to facilitate widespread social change. By employing Afrofuturistic fiction, Black girls merge reality, dreams, and action.

Black girls have long used art to name and construct their freedom dreams. Historically, Black women have used art as blues singers, poets, artists, and storytellers to express the truth of their inner lives, discuss the struggles of the Black community, but also to give voice to Black women’s creativity and survival (Berry and Gross, 2020). Through the work of literary Black women titans Zora Neale Hurston, Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, Maya Angelou, and so many more, they tell Black girls’ stories, not only making society see Black girls’ existence and their presence, but the fullness of their humanity. As an example, in Ntozake Shange’s (1975) monumental choreopoem, for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf, the women engage in joyful, childlike wonder and play as they chant, “mama’s little baby likes shortnin, shortnin,” and “little sally walker, sittin in a saucer.” They dance across the stage, letting the rhythmic melody serenade them as they get lost in the moment. While the choreopoem tackles the heaviness and violence of racism, patriarchy, abuse, and assault, they reclaim their joy through music, dance, and friendship. They (re)write their stories by centering their dreams of freedom and they weave the “strength and sadness” (Nunn, 2018) with the joy that society tries to rob from them. They engage in the practice of Black feminist futurity, a “performance of a future that hasn’t yet happened but must” (Campt, 2017, p. 34). Black girls seize their joy as a future-making process.

As part of a legacy of Black women writers and artists, Black girls use writing, journaling, social media, movement, music, hair, and dress as arts-based practices to understand their own identities, and to tell their stories and counteract the negative stereotypes that confine them (e.g., Gaunt, 2006; Winn, 2011; Muhammad, 2012; Brown, 2013; Muhammad and Haddix, 2016; Muhammad and Womack, 2015; Evans-Winters and Girls for Gender Equity., 2017; Lu and Steele, 2019). When Black girls take up space and express themselves in places not built for them, they resist the oppressive forces that often take away the joy and fun of learning.

Annamma (2017) called for a “pedagogy of resistance” which includes arts-based curriculum such as dance, art, and poetry (p. 145). This resistance shows up in the form of dismantling stereotypes by sharing their own truths. Language, specifically spoken word, can help Black students resist dehumanization (Desai, 2017). As an example, Jacobs (2016) explored how Black girls in grades 9–12 enacted “oppositional gaze” (i.e., speaking back to negative narratives; hooks, 1990) using forms of media. One girl made a poster that said “Black girls rock!” to push back on dehumanizing narratives using an affirmation. In another study, Muhammad and McArthur, 2015 found that Black girls felt that the media judged them by their hair, personality, and how vocal they were. In order to talk back to these negative stereotypes, the participants wrote about their own experiences to reveal their truest selves. One participant, Dahlia, noted, “…Who can tell our stories best but us?” (Muhammad and McArthur, 2015, p. 137). In this naming practice, Black girls (re)member the legacy in which they come from, as well as their creative resistance in telling their own stories (Dillard, 2012).

As Black girls construct their identities, they posit their dreams alongside their examinations of the structures and systems of oppression. For instance, Turner and Griffin (2020) conducted a case study of twin sisters engaged in multimodal artwork to share their career aspirations. The sisters created boards of their future careers and life goals and critiqued the underrepresentation of Black career women images on Google. In this study, Black girls used multiliteracies, including professional literacies (e.g., presenting career dreams), aspirational auditory (e.g., music), and life literacies (e.g., help Black girls navigate the world). Further, in another study by Griffin and Turner (2021), they explored how middle and elementary school students identified Black futures in their multimodal renderings of responses to the police murder of Michael Brown case. Students challenged anti-Blackness and reimagined futures where anti-Blackness does not exist. Black girls grapple with truthful accounts of history in order to dream new futures both in their personal aspirations and in the world.

Freedom dreaming for Black girls is a radical act of resistance as it asserts their presence in a future in a society that has desperately aim to erase their existence through policing, control, and punishment. Kelley (2003) said, “progressive social movements do not simply produce statistics and narratives of oppression; rather, the best ones do what great poetry always does: transport us to another place, compel us to relive horrors, and, more importantly, enable us to imagine a new society” (p. 13). As Kelley (2003) directly names what great poetry does, I am reminded of the power of art in creating and sustaining social movements. This is freedom dreaming – believing in and pouring life into a world that does not exist yet (adrienne maree brown, as cited in Love, 2019). I am also re-prompted to think about how freedom dreaming and Afrofuturism make us confront the past as we orient our gaze forward. Research shows how Kelley’s (2003) conceptualization of freedom dreaming shows up in practice and this study adds to the scholarship while providing arts-based, participatory methodology as possibilities for deepening our understandings of freedom dreaming in out-of-school spaces.

Arts education

Bettina Love (2019) noted that art frees up space for creativity, which is necessary in imagining and creating a more just world. However, arts education is not accessible or equitable in today’s public schools. A study conducted by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (2009) found that schools that cut time and resources for arts education are in predominantly Black and Brown communities, and are often designated as “in need of academic improvement” (as referenced in Cratsley, 2017). When schools are marked in this way, funds are often shifted from creative opportunities to test-based accountability reforms, which promotes control and conformity rather than imagination (Yee, 2014). I argue that this is a strategic effort to deny Black students the space to dream and create in schools to stifle protest and social movement.

Not only is art education stratified, but when Black and Brown students do have access to arts education, there are very few policies in place that ensure that arts educational experiences are culturally affirming (Kraehe et al., 2016). To illustrate, Charland’s (2010) study showed that Black students discussed remembering artwork they did at home more than artwork they created at school. The art they were most proud of represented their communities and told their life stories, while the art they made at school were given good grades for simply following directions. This contributes to the importance of out-of-school art-making, where students are able to bring their culture and life experiences into their art and were proud of that art.

Art educators have traditionally rewarded technically talented individuals and students that follow directions; however, art education should be regarded as “social and aesthetic studies, intended for all, and as socio-cultural necessities” (Desai and Chalmers, 2007, p. 9.) For students who often do not see their cultural arts practices being taught or highlighted in either content course curriculum or in arts classes, it is difficult to see and engage in art as an avenue for expression at school. However, as evidenced by Charland’s (2010) study, students are already creating art outside of schools that gets policed inside of schools through rigid grading practices.

Scholars have argued for a more expansive arts education that centers futuristic counter-narratives without subscribing to the liberal multiculturalism that exoticizes the African diaspora (David, 2007; Boyd Acuff, 2020). As an example of this work in practice, Dando et al. (2019) studied the ReMixing Wakanda Project, where students engaged in design practices to create medallions as an artifact that detailed their personal histories and then were put together to make a collective artifact. Additionally, in a systematic review of 155 publications, Mims et al. (2022) found that research and practice often confines Black creativity and neglects Black brilliance. Thus, they call for more support for fugitive spaces that center creative expression and education, particularly because many of the spaces where Black children engaged in effective creative educational experiences were outside of traditional schooling spaces (Mims et al., 2022). To carry forth their framing of Black creative educational experiences and to explicitly be more inclusive of the many ways that Black girls express themselves, I use the term arts-based practices, rather than art. While “traditional” art education has long been a rigid practice of conformity, I am inspired and grounded by the work of Black women who explore Black girl literacies that build on the monumental work of our literary and artivist (i.e., artist-activist) foremothers. This study adds to the body of empirical literature that looks at creativity, specifically Black creativity, in an expansive way that does not limit Black brilliance.

Out-of-school spaces

Out-of-school spaces can be fugitive spaces. Jarvis Givens (2021) described Black education as a “fugitive project from its inception – outlawed and defined as a criminal act…the pursuit of literacy in secret places” (p. 3). While fugitive spaces can occur in schooling spaces, Black girls often experience formal educational spaces as sites of oppression, which is evidenced through school policies, curriculum, and pedagogical practices that work to suppress their cultures and languages (Paris and Alim, 2014; Hines-Datiri and Carter Andrews, 2017). Community-based programs can serve as potential sites where liberatory pedagogy can be further developed, enacted, and sustained. These spaces can encourage “Black children to imagine, dream, create, resist, take up space, and be […] [and] to define themselves on their own terms, free from interruption and prescriptive identity markers placed on Black folx” (Dunn and Love, 2020, p. 191). While the K-12 curriculum is often constrained by standards and high-stakes testing, out-of-school spaces provide flexibility to explore creative endeavors without the bureaucracy and politics of K-12 policies and standards.

To fill the curricular gap that does not amplify Black people’s stories, out-of-school programming must connect Black girls “to their unique histories and their Blackness” (Nyachae, 2016, p. 799). While programs may connect Black girls to one another, it is critically important to also examine historical context and build critical consciousness. Programs that promote “empowerment” (Brown, 2013) or push for certain ways for how Black girls should act (Nyachae and Ohito, 2019) can be harmful spaces that reproduce respectability politics and further constrain Black girls’ identities (Cooper, 2017). For an example of the importance of moving beyond the empowerment frame, the Saving Our Lives, Hear Our Truths (SOLHOT) program invited Black girls to be part of a revolutionary space where they could determine and envision Black girlhood on their own terms (Brown, 2013). Other studies have also explicitly used Black feminist pedagogy in after-school programming. One study showed that Black girls who participated in the program deepened their critical consciousness and developed a stronger sense of self-esteem that resisted negative stereotypes, as compared to girls who did not participate (Lane, 2017). Liberatory pedagogical models help Black girls see beyond the one-dimensional narratives they learn in school to what could be possible in the future.

To think expansively about the fusion of arts-based and participatory action research, I also looked outside of empirical research to better understand how freedom dreaming showed up in out-of-school settings. Choreographer and dancer Camille A. Brown used Gaunt’s (2006)1 work as a framework to build a program entitled Black Girl Spectrum (BGS). In this program, she used participatory action research with adolescent Black girls. The research informed a production they crafted called BLACK GIRL: Linguistic Play, which used dance, double dutch, music, and hand game traditions from West and Sub-Saharan African cultures to highlight scenes that performed Black girlhood and womanhood. The production gave performers a space to come into their “identity from childhood innocence to girlhood awareness to maturity—all the while shaped by their environments, the bonds of sisterhood, and society at large” (Brown, 2015, para. 2). Communal spaces, like the creation of BLACK GIRL: Linguistic Play, establish spaces for self-affirmation, growth, and healing (hooks, 1990). These spaces also serve as “homeplaces” or “homespaces,” where Black girls can come together to celebrate themselves and each other (hooks, 1990; Jacobs, 2016). Brown (2015) explored what a homeplace could look like onstage for Black girls to support one another as they process through their development. This participatory research fused with performance theory informed the construction of the Black Girls S.O.A.R program. While Brown’s (2013) and Brown’s (2015) work provide both the infrastructure and vision for this study, I sought to add to the body of work that centers participatory, arts-based research in the field of education. This article and work rests in a legacy of Black women critical literacies scholars, fugitive Black education scholarship, and arts-based practice literature.

Materials and methods

Black Girls S.O.A.R.

The program, Black Girls S.O.A.R., aimed to co-create a healing-centered (Ginwright, 2014) space to engage artistic explorations of history, storytelling, Afrofuturism, and social justice with eight Black girls. The study took place from July 2020-September 2020 in a fully virtual format on Zoom.2 In addition to artistic exercises, co-researchers participated in research training, collected and analyzed data, and took themes from the data to create artwork they presented in a community arts showcase to their loved ones.

The first session explored the history of the Black Freedom Struggle as we learned about Black women activists and artists. In the second session, we discussed the meaning of self and community care. With an emphasis on self, we crafted artwork that showed our counter-stories, and explored the counter-storytelling tenet of C CRT. During the third session, we discussed Afrofuturism and what it means to write ourselves into the stories of the present and the future, with inspiration by Octavia Butler, Janelle Monáe, and N. K. Jemisin. During this session, we also learned about qualitative coding and engaged in group coding of the transcripts from our first three sessions. During our fourth session, we wrote our own Ten Point Program based on the Black Panther Party’s program to show how we could demand the world we deserve. At the end of the program, the co-researchers put together a Community Arts Showcase for their loved ones to highlight the artwork they crafted that told the story of the data.

Co-researchers and recruitment

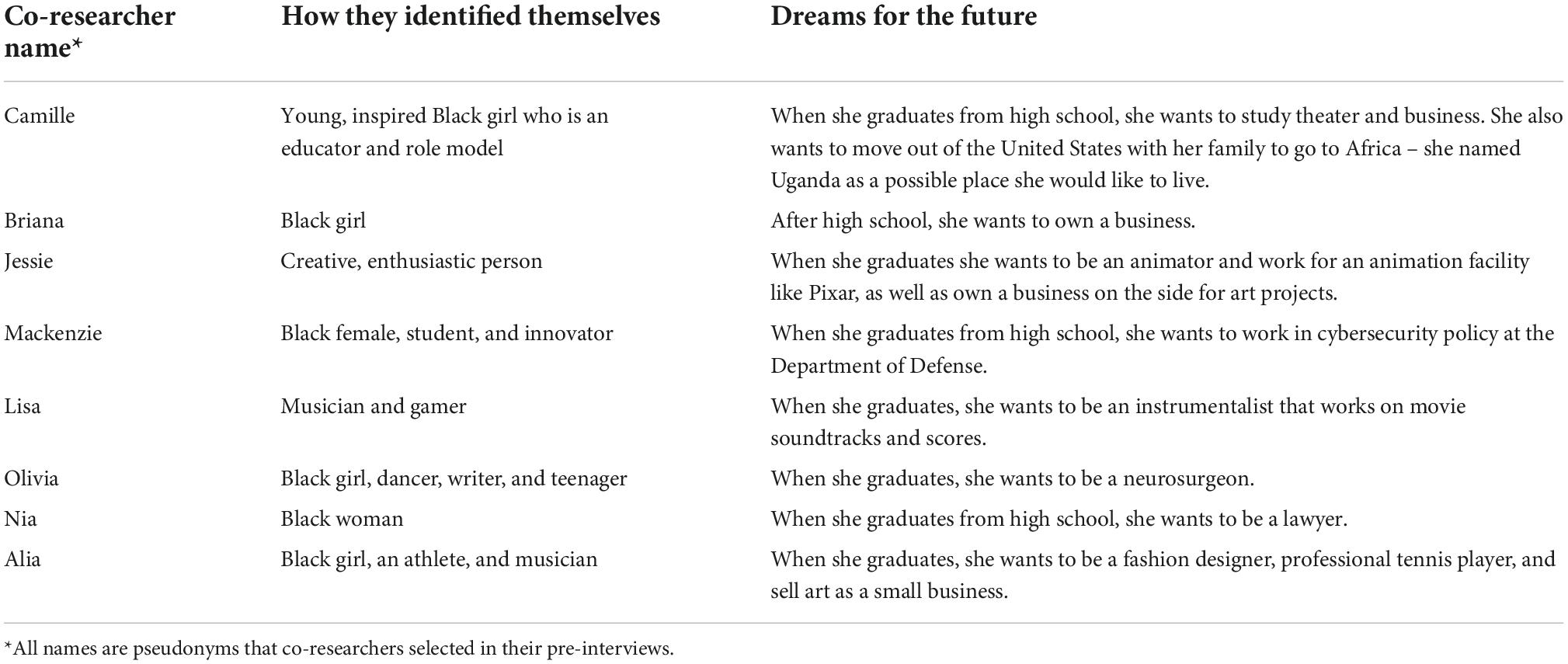

The co-researcher team included eight Black adolescents who identify as girls. The co-research team consisted of high school students ages 14–17. Co-researchers were recruited from a dance studio where I regularly teach and also through snowball sampling. I created a two-page Black Girls S.O.A.R. recruitment sheet with information (e.g., goals of the program, dates, and times), and an outline of the sessions, which the dance studio shared via e-blast. Three middle and high school teachers in Washington, D.C. also shared the recruitment sheet with their Black girl students. I introduce the co-researchers in the ways they identified themselves in the pre-interview, as well as the way they described their dreams for the future (Table 1). The descriptions are all in their own words to privilege how they are “naming themselves for themselves.”

Throughout the program, we determined that we wanted to use the term “co-researcher” to describe how we participated in and contributed to the study. With inspiration from Toliver (2021b), I recognize that “freedom dreaming requires intergenerational imagining.” In the spirit of abolitionist values – creativity, determination, rebellious spirit, subversiveness, love, and freedom – I invited the co-researchers to dream alongside me about how schools and society could look and feel if they were centered on love and community (Love, 2019). We researched together, and we also created artwork together. Performance ethnography lends itself to participatory methodology and the larger study from which this data comes from included the co-researchers engaging in research training about data collection and analysis. In the larger study, they collected data (e.g., oral history testimonies from loved ones) and analyzed the oral histories and the transcripts from our conversations to create artwork to share in a showcase for their loved ones.

Positionality

The study was conducted from the perspective of the author, who ran the virtual Black Girls S.O.A.R program. I am a millennial Black and Filipina cisgender woman who has long called the eastern coast of the United States home. I have taught dance and movement classes to Black and Brown girls in both the D.C. Metro Area and rural and suburban New Jersey for over ten years at the time of writing this. As a dancer, a choreographer, and an artist, I frequently engage in art-making practices that allow me to “attend to the inner-child work, desire-checking, and a commitment to creating fugitive spaces for Black girls” (Young, 2021, p. 15). I am an on-going student of abolition. This also shapes my dedication to arts-based work, as I have witnessed how it has guided my self-concept and dreaming practices, as well as that of the young people I work with.

Research design

I used performance ethnography (Denzin, 2003; Soyini Madison, 2006) to contend with the following research question: How, if at all, do adolescent Black girls use arts-based practices (e.g., visual art, music, hair, and animation) to freedom dream? This approach centered the co-researchers’ perspectives, particularly as it was expressed through art in the program. Performance ethnography brings together ethnographic methods, with its foundation in cultural anthropology, and theory from performance studies (Soyini Madison, 2006; Denzin, 2009). Performance as a method of inquiry allowed me to consider how Black girls perform multiple, layered, and nuanced identities, acts of resistance against structural and systemic oppression, and dreams for the future. In essence, constructing and performing acts of resistance and freedom dreams helps us to better understand and make visible these aspects of self, as well becomes a modality for remembering and re-representing who they are. Taken with CRT at its helm, performance can be questioned in this case as performing for whom and for what? In this study, I wondered: How can we seek to move away from performing for the white gaze or the male gaze? This guided the decision to center a Black girl space.

Further, performance ethnography takes the data collected and turns it into a performance accessible to audiences outside of the academy. We collectively coded the transcripts to develop a list of inductive codes after participating in an interactive research training, which the co-researchers then determined how they would individually and collectively turn the themes from the data into artwork. The method utilizes arts-based practices to explore the multiple and varied expressions of Black girlhood. A multiple methods approach is needed to understand and access Black girls’ innermost thoughts and feelings (Neal-Jackson, 2018). The “overreliance on oral and written communication” fails to fully capture the ways that individuals comprehend themselves, the world, and the relationship between the two (Kortegast et al., 2019, p. 503). This concept is enacted through the decision to collect and analyze the artwork the co-researchers created throughout the program and presented at the Community Arts Showcase. Additionally, it was not about creating art for the product, but for process. Art encouraged further dialogue and discussion.

To study how Black girls’ use arts-based practices to resist oppression and dream, Black girls are central to examining what they are resisting, how, and what they hope to build instead. For example, during the pre-interviews, one of the questions on the interview protocol was, “If you were leading a program for Black girls, what would you and your girls do?” Their answers informed and shaped the curriculum for the program. To illustrate, Nia said, “We would learn history about ourselves first.” When I brought this to the group, they said they wanted to learn about their family’s stories by interviewing them. They also named that they wanted to learn about Black women and girl activists and artists. We engaged in a mixer lesson developed by Teaching for Change called Resistance 101, where they read and did research on the lives of Black women and girls such as Judith Jamison, Ella Baker, and Destiny Watford. Each co-researcher shared in their interview that they wanted to create art, so many of the activities we did involved an artistic element and guided the usage of performance ethnography as methodology.

Data collection

Co-researchers and I collected our conversation transcripts from the sessions, which we collectively coded and analyzed to understand themes. Data collection was “two-tiered.” The first tier was the data the co-researchers and I collected together, including transcripts from our conversations during the first three sessions. The second tier was my simultaneous collection of pre-interviews, field notes, artifacts (artwork), the transcript from the final session and Community Arts Showcase, and my reflections after each session. The second tier allowed me to gain a sense of co-researchers’ thoughts, perspectives, and feedback on the program. This article focuses on analysis of the pre-interviews, transcript data, and artwork from the session and the showcase.

Throughout data collection, the choice to center art was guided by the theoretical framework’s emphasis on art to dream and build. A few components of abolitionist teaching are rebellious spirit and subversiveness, which include tackling and disrupting myths and dominant narratives we learned in school as part of the curriculum. Additionally, during the pre-interviews, the interview protocol included questions such as, “What are your dreams for the future?” to encourage co-researchers to engage in future-casting as part of the curriculum and research process.

Data analysis

Data analysis involved collaborative coding with co-researchers during the program and coding I did on my own. I used inductive and deductive approaches to privilege the co-researchers’ direct quotes, while also examining the data in light of the research questions and the framework. Data analysis was conducted in three stages. In the first stage, I prepared the data, specifically the pre-interview transcripts and transcripts from the first three sessions. I transcribed the pre-interviews before the program began, so that I could prepare the activities and topics from the co-researchers interests and feedback. Then, mid-way through the program, I transcribed the first three sessions and de-identified transcripts to share with the co-researchers to conduct the second stage.

In the second stage, the co-researchers and I collectively coded the de-identified transcript data during the third workshop session using in vivo coding (Saldaña, 2009) with my guidance and assistance. I included a coding training portion in the third session of the program. This meant inviting co-researchers into the process of seeing their own words on paper in the form of a typed transcript so they could hype each other up, as well as bear witness to their own brilliance on paper as a self-love practice. The initial codes they highlighted included: history, resistance, narratives, school, and care. Some of these codes, such as narratives, were collapsed for a more specific code from other codes including stories and communication. From the codes, co-researchers discussed the emerging themes and defined these codes from reading the transcript data.

The permanence of seeing their thoughts on paper as “commensurate with other ‘data’ they will learn in school” gave way to futurity (Morris, 2019, p. 127). They saw both their past selves through their ideas on paper, as well as their future selves because of its permanence. Further, putting Black joy and love at the center of practice meant engaging in member checking to ensure I was representing the co-researchers’ thoughts and perspectives during two critical moments: (1) during week three and four of the program, where participants coded and analyzed transcript data from the program discussions and (2) when the first draft of the findings section was written.

In the third stage, I deductively coded in light of the theoretical framework (e.g., creativity, rebellious spirit, racism) and research question (e.g., freedom dream). To code the artwork created throughout the program, I used Turner and Griffin’s (2020) adaptation of Serafini’s (2014) framework to create coding sheets for the visual artwork.3 First, I used the coding sheet to write down who/what was represented (perceptual dimension); the relationships between the visual elements (structural dimension); ways the images represented aspects of freedom and resistance (ideological dimension); and how the co-researcher discussed the meaning of their artwork (Turner and Griffin, 2020; Table 2). I recognized that “the meaning ascribed to images are socially constructed” (Kelly and Kortegast, 2017, p. 7). Since my goal was to ensure that I accurately reflected the co-researchers’ meaning behind the artwork, I encouraged them to describe what the image meant to them in their own words.

Findings

Analyses of the data revealed that co-researchers used arts-based practices to freedom dream in three ways: to reclaim stories, to pose Afrofuturistic visions, and use art as activism to create action steps toward those visions.

Reclaim stories

Throughout the program, the co-researchers used art to rewrite history and recreate historical narratives they learned in school. In their pre-interviews, many of the co-researchers discussed wanting to learn about “their” history, meaning Black history. During the first session of the program, I asked the co-researchers what they learned about Black history in school, at home, or in their community. They expressed that the only topics they covered in regards to Black history at school were enslavement, Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycotts, and Martin Luther King, Jr. In essence, the girls reported learned very little about Black history, only focused on a few figures, and learned about Black trauma by mostly seeing their ancestors depicted as enslaved in textbooks without learning about how enslaved people resisted. By only highlighting false narratives of Black subservience, the standard curriculum communicated to them and their classmates that Black peoples’ history began at enslavement and ended with the Civil Rights Movement. Lisa, a 17-year-old musician and gamer, shared,

I also think that they [teachers and textbooks] should explain that Black history isn’t full of suffering and that they should explain a lot more of the successes that are in our history and that make us who we are because there is and not everything is suffering for us. There are a lot of artists and things that we don’t learn about (Session 1).

Lisa points out how the narrative of suffering, especially when that narrative fails to share stories about Black success and joy, affects how society views Black people. Lisa followed up by mentioning that the way textbooks told the stories of Black history made it seem like this history was not still being made,

I also want to say I was thinking about something that I saw on a post and someone was like, “You guys can’t keep blaming what happened to your ancestors on us.” The comment under it was, “It wasn’t our ancestors. You mean our grandparents and our great-grandparents?” In the way it’s written in textbooks it seems like this happened so long ago, but it wasn’t. It was not that long ago (Session 1).

The idea that we live in a post-racial society absolves individuals of dismantling the very systems that continue to privilege and oppress. It perpetuates a false narrative that keeps people apathetic and subverts social movements.

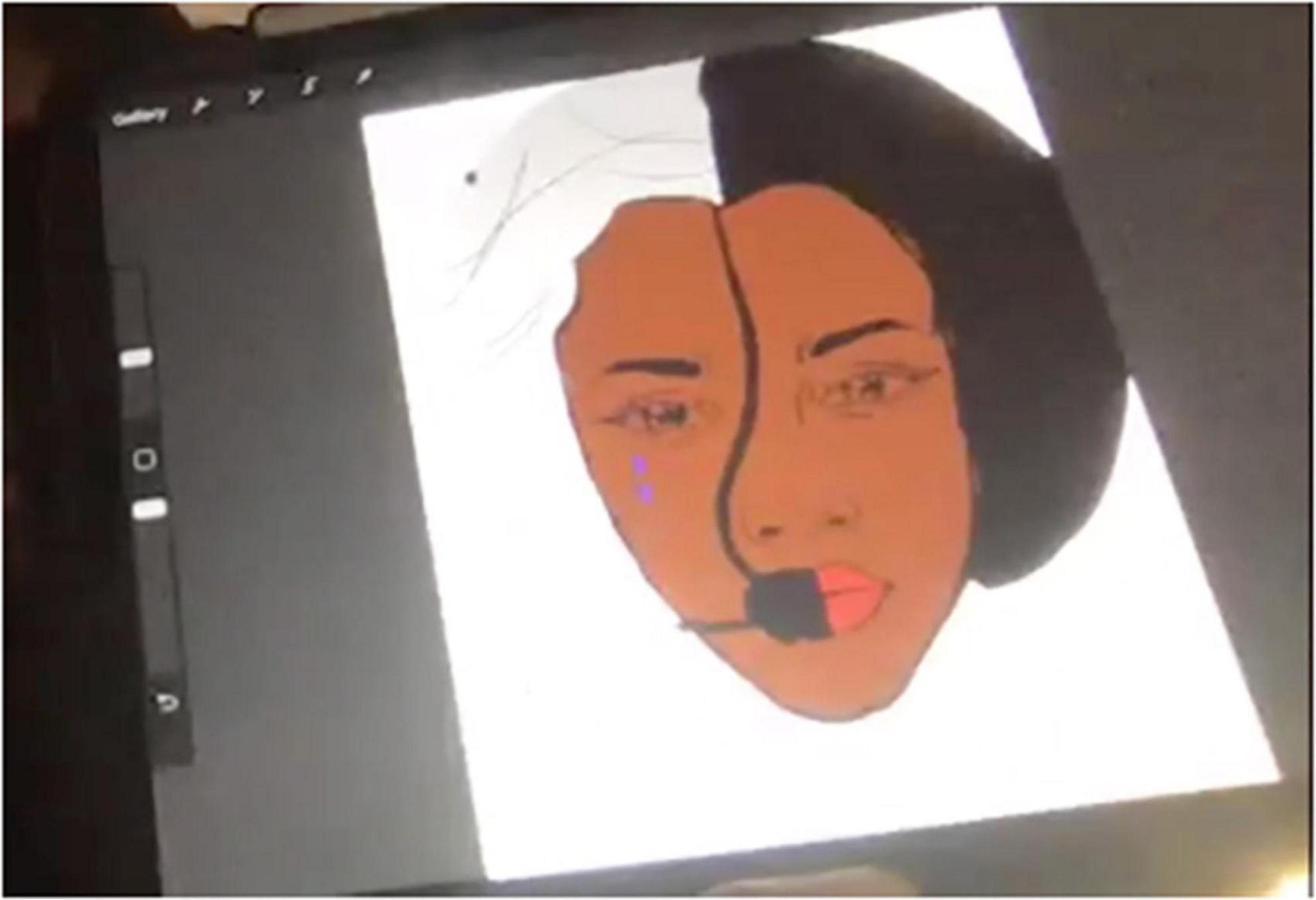

The co-researcher’s artwork also emphasized how narrowly presented Black history is in schools. Mackenzie, a 15-year-old innovator, presented a drawing that illustrated a Black woman with an Afro with a tear streaming down her face (Figure 1). Mackenzie shared her artwork at the Community Arts Showcase,

I wanted to highlight the Afro like when we talked about the Black Panthers and how female Black Panthers wore their hair naturally. That’s what I was trying to highlight there. Then, I also drew tears on the narrative that we’re told because I feel like that’s usually how we see Black people in our textbooks and things like that. They’re always sad and crying, but in reality, we are powerful, even though we’ve gone through some rough Things (Session 5).

One half of the face had lightened hair to contrast with what Mackenzie drew as an Afro that symbolized the Black Panthers’ resistance. The Afro was a symbol of strength and resistance to Mackenzie. The other side of the face has a muzzle over the mouth. In Mackenzie’s explanation, she noted that this is the side that is typically depicted in textbooks, which communicates that Black people are not only shown as in pain, but lacking voice because they are absent or only shown in confined, minimal ways.

Not only did the co-researchers rewrite the history they see in textbooks, but they reclaimed their own stories. Nia, a 14-year-old future lawyer, shared a powerful counter-narrative during the Community Arts Showcase. She drew a heart with her name and wrote words that described her positive attributes. She stated she drew “bad things that people say” about her on the outside of the heart, which were “crossed out and faded.” The words that were closest to the heart with her name, such as “best friend” and “determined,” were “believable because they’re the good ones” (Session 2). By having the positive qualities, the qualities that she saw in herself, close to her, she represented what it would look like to hold these aspects of her identity close, while physically separating herself from the negative feedback. The co-researchers used art as counter-narrative and to perform a future that can and must exist. To emphasize, Jessie, a 14-year-old self-described creative animator, shared,

I would say specifically when I make art, I use it to define a story and get words out and go against what other people maybe think, or their perception of other people, how they perceive people and how they think they are. I go against that (Session 4).

Jessie highlighted the importance of art to reclaim stories. She goes against that by telling her own story.

Dream new worlds

When asked in the pre-interviews their dreams for the future, many of them regarded the future as their plans for when they graduate. They shared aspirations such as becoming a neurosurgeon, lawyer, entrepreneur, and animator. Co-researchers also expressed their desires to move out of the country, continue on with their art, and hold multiple roles (e.g., photographer and cybersecurity analyst). They put no limit on their individual life dreams. However, they began to think of their hopes more expansively as the program went on, particularly how their own visions related to dreams they had for the future of society.

During the third session, the co-research team and I discussed Afrofuturism and what our dreams were for a better world. After defining the term Afrofuturism, we watched a clip of Black Panther that detailed the Wakanda origin story. After viewing the clip Mackenzie, 15-year-old innovator, named the contradictions she observed. “It frustrates me that in the movie they pin African people against Black people. If we’re thinking about new worlds, I wouldn’t want that to be the case” (Session 3). Mackenzie was already naming her freedom dreams before we introduced the dreaming activity.

We drew our own Afrofuturistic worlds with these prompts guiding us: If you could design a new world, what would it be like? Where would it be? What resources would it have? Who would be in leadership, if anyone at all? The answers to these questions inspired the co-researchers’ dreams of a world where equity, justice, love, and joy were at the forefront. Many of the Afrofuturistic worlds the co-researchers imagined addressed some of the current problems they see in society. For instance, Olivia, a 17-year-old self-described dancer and writer with aspirations to be a neurosurgeon, discussed her world,

My Afrofuturistic world would be an all-inclusive society. There is no hatred towards one another. There is love. We welcome all people. That was the main value, that everybody is just kind to one another. We had to talk about the things that we would have there. I wanted community facilities. There was a place where people who weren’t from here could come for sanctuary or for permanent citizenship (Session 3).

Olivia imagined her world as welcoming and inclusive, but it also provides community care supports. Her world would not only welcome those who are part of the community, but also others who are in need of community. She recognized the power in supporting one another. In Olivia’s case, she was offering subtle commentary about how the United States weaponizes policy to keep Black and Brown people out of the country. She made clear that she opposed keeping people out.

As another example of an inclusive world, Camille, a 15-year-old young, a self-described inspired Black girl shared that “Everybody takes care of each other. We don’t have a president or higher power. We’re all equal in this [world]” (Session 3). The co-researchers dreamed of a world that was not governed by one person, but rather all people working collectively. She was making a statement about her observations of different forms of government. In her drawing, the community is surrounded by nature represented by “string lights,” which hang from the trees and gave an ethereal feel to the scene. It was illuminating the future of a society that is truly equal. Camille noted, “my world is not here” (Session 3). By “here” Camille was referring to the United States. By saying that her world was not here, it reinforced how she viewed the United States as a place that is not equal.

In a previous session, Camille also shared that she wished that she and her loved ones could move to a different country where there were “more people that looked like” them (Session 2). She also mentioned wanting to move to another country in her pre-interview – a resounding theme. In her drawing, she used darker colors to illustrate the beautiful skin tones of the community members. This underscored, in many ways, how the co-researchers felt that they were being failed by United States society in its lack of providing the structural support needed for them to feel affirmed and valued in this country.

Even in their frustration, the co-researchers offered moving visions for what could be possible. Some of their worlds even bridged the past with ideas they had for the future. For example, Jessie, a 14-year-old creative animator, shared an idea of how she envisioned aligning technology and nature (Figure 2),

One of the main things that I would want was the house in my drawing to be powered by the waterfall in the background so that it would be connected to nature but still be technology-based [powered by the waterfall]. I drew a house that looked similar to the ones I’146;ve seen in pictures my family has shared from Ghana (Session 3).

Jessie’s weaving of nature and technology exemplifies the possibilities of the future when situated in the visionary inventiveness of Black girls. As Jessie illustrated, the house resembled a hut on stilts that raised it above the water. Rather than choose a house that looked like one in her community, she chose to recreate one from what she had seen in a picture from Ghana. The waterfall behind the house offered an energy source to power the home, which reflected Jessie’s commitment to efficient, clean energy and climate justice. It is also an example of how many of the co-researchers, including Jessie and Camille, chose to depict nature in their drawings, rather than cities or suburbs.

They valued their relationship with nature by having it be a highlight of their artwork.

Art as activism

The week after our session on Afrofuturism, we focused our conversations on activism, specifically art as activism. We discussed activism in light of the worlds we crafted to collectively brainstorm how we could use our actions to actually build these dream worlds in our everyday work. We recognized that in order to see the changes we wanted, activism was necessary to bring about those changes. The co-researchers talked about what activism means to them,

Alia: I’m thinking you have to be bold and be able to speak up all the time and care for others, but also care for yourself as well.

Briana: I just think that that means that you’re very passionate in who you are and inspire others to feel great about who they are too.

Jessie: Personally, I feel like activism can come in a lot of different ways, not just we, when we think of an activist, we do think of someone who’s out there doing things. I feel that’s a really good example, but when you talk about how do you personally see yourself as an activist, I feel like you can be a small-scale activist and just be an activist within your friend group or within your community. Just boiling down to it, it’s just speaking out for what you believe in. I feel like that’s just what it is.

Camille: There are going to be so many people in this world that silence you and tell you that your voice doesn’t matter, but it does. Activism is also resistance, and it’s taking a lead and showing an example to people who are younger than you, older than you, just really being, I guess, like a teacher and spreading the word about what you know is right or what you believe in. That’s what activism is to me.

Mackenzie: I think being a Black girl activist means talking about the injustice that you have seen. Not being complicit in all the racism going around, but just actually talking about your experiences, because, I guess, it’s easy to see a statistic. That doesn’t really have a ton of meaning. It’s just a number. But when you tell your story, then that’s someone’s Life.

Alia, Jessie, Camille, and Mackenzie all mentioned concepts of “speaking up,” telling your story, and how activism can happen at many levels (e.g., with yourself, your friends/community, and the world). Together, we talked about how, as activists, we stand up for what we believe, but how we also have the power to use our art, our strengths, our gifts, and our talents to influence, create, and fight for the world we dream of. To dig deeper into activism and organizing, we used the Zinn Education Project’s lesson, “What We Want, What We Believe”: Teaching with the Black Panthers’ Ten Point Program. We reviewed the Black Panther Party’s Ten Point Program to relate what the Black Panthers were demanding in the 1960’s to what we are still demanding today.

After reading the Ten Point Program, we discussed the similarities and differences between the Black Panthers’ demands and current injustices. Specifically, we noted how the end to police brutality is something we are still fighting for. We also offered other thoughts and insights about the language the Black Panthers used to detail their 10 points. For example, Mackenzie, 15-year-old innovator, raised a critical point,

I can’t remember if anyone [one of the other co-researchers] said this. Of the first six ones, something that was a common theme [in the Ten Point Program], was decent housing and decent education. I don’t know. I just think it’s interesting that what they were pushing for was just decent and not equal because I feel like decent has the connotation of the bare minimum. I guess that is your right, is to have the basic whatever, or basic anything. I think that they should have been pushing for something other than just decent (Session 4).

Mackenzie’s point encouraged the team to think about what we would demand in our Ten Point Program. We reflected on what the Black Panthers may have grappled over while discussing the Ten Point Program and how they may have struggled over what words they wanted to use.

Specifically, the co-researchers wanted to make sure they accurately and vividly reflected their dreams for what the world could be by being intentional with their language. Mackenzie pushed us to think about how to demand justice and go beyond just decent. Using the Ten Point Program, the co-researchers developed their own demands.

Black Girls S.O.A.R. Ten Point Party Program

We want…

1. A fixed justice system

2. Equality in race, gender, and religion

3. We want to have free rights to believe what we choose, to follow who we want to follow and speak our minds

4. Officers involved in shootings of Black people held accountable and charged

5. We want to ban conversion therapy, the KKK, and other organizations/groups that cause harm

6. We want an immediate end to workplace and school discrimination for the hair choices of Black people

7. We want to end private prisons/for profit prisons

8. We want an end to the over-policing in Black neighborhoods

9. We want to replace police in Black schools with counselors

10. We want to incorporate the teaching of Black history as a required course in the school system (2020).

Much of what we outlined in our Ten Point Program highlighted how oppressive systems continue to police and punish Black people, including police in schools and neighborhoods, hate groups like the KKK, and also the carceral state of prisons. We were also concerned with ensuring equity, equality, and justice for all people, including LGBTQ+ communities and other oppressed groups. Along with the demands for society, we also detailed our demands for schools, including teaching Black history, hiring more counselors, and ending hair discrimination. Through our demands, the co-researchers offered a roadmap for not only creating a world where Black girls feel safe and affirmed, but where all people, specifically oppressed communities, could experience freedom and liberation. Black girls’ freedom dreams are inclusive.

Discussion

I approached the analysis of the findings by weaving together connections to illuminate major themes and considerations in the data. I specifically focused on emphasizing the linkage between language and art – how both communicate the “inner lives” (Simmons, 2015; Berry and Gross, 2020) of Black girls to help us understand their experiences beyond the surface of the raw data.

For co-researchers in the Black Girls S.O.A.R. virtual summer art program, our time together illustrated the Ghanaian principle of Sankofa (“it is not taboo to fetch what is at risk of being left behind”). Sankofa teaches us that we must (re)member our roots, or our past, in order to move forward and reimagine a future rooted in Black epistemologies (Dillard, 2012). The symbol of Sankofa is represented by a mythical bird with its body faced forward and its head turned backwards to retrieve an egg from its back. This embodies the idea that we must honor the teachings of the past and those who have paved the way in order to carry us forward. The co-researchers were on a quest for knowledge – knowledge of self, knowledge of community, and knowledge of ancestry. In this quest, they came to uncover stories about Black history and in the process, they realized stories about themselves.

While some stories emphasized Black struggle, all of the stories offered a duality of pain and power. Nia’s drawing showed how the negative feedback never touched her, while Mackenzie’s portrait juxtaposed pain (i.e., the tear) with power (i.e., the Afro). Even Olivia’s poem, which opens this article, has a physical split to emphasize the two distinct stories that are told and can be told about Blackness. This is aligned with Nunn’s (2018) “strength and sadness” conceptualization which was applied to younger Black girls and for older Black girls, this showed that their version was pain and power. Through this naming, the co-researchers showed their full humanity on paper, which is an essential part of freedom dreaming in a society that seeks to rob Black people’s humanity (Desai, 2017). It carried on the work of Black women literary titans to assert Black girls’ presence by placing their personhood on paper, so it could not be erased.

Art was how they made sense of, solidified, and presented their identities and stories. Art laminated their freedom dreams. In other words, Black girls seeing their identity and dreams on paper or another medium through writing or art makes it so that they can see and speak back to it (Muhammad, 2012; Muhammad and McArthur, 2015). For example, many of the co-researchers voiced their career dreams for the future when asked (Turner and Griffin, 2020), but also provided more broad ideas for their dreams for the world, such as being governed by the people or letting all people be a part of the community. In a society that strives to push them out of spaces, like schools, their art is a visible reminder of their presence in the present and the future. They used art to tell the stories of their experiences and speak back to negative narratives, which supports previous studies that have found that Black girls use critical media literacy to create counter-narratives and analyze the messages they receive (McArthur, 2015; Muhammad and McArthur, 2015; Jacobs, 2016). The co-researchers looked back, in a sense, at stereotypes, in order to look forward. Additionally, they engaged in a practice of (re)writing. The prefix re- means to do again. As Dillard (2012) discussed the concept of (re)membering, the co-researchers already knew their stories, but schooling served to make them forget who they are. This study highlights the importance of creative expression for Black girls in fugitive spaces to affirm their multi-layered identities and see those identities in the future. Black girls need to see that their identities and stories are, literally and figuratively, works of art.

Abolitionist teaching, in this program, looked like bridging the past with the future through counter-narratives. They drew themselves into history, specifically they told historical stories that emphasized Black people’s creative resistance. Richard Delgado (1989) reminded us that “oppressed groups have known instinctively that stories are an essential tool to their own survival and liberation” (p. 2436). They critiqued dominant narratives they learned, while mentioning how telling their stories is a form of activism. Art was their tool for sustaining their cultures and making sure asset-based stories about Black people survived in the future. This supports scholars’ work that showed how storytelling is “one of the most powerful” practices Black girls’ employ to “convey their special knowledge” (Richardson, 2003, p. 82).

In Jessie’s Afrofuturistic drawing, she bridged the past with both the present and the future by interweaving technology powered by a waterfall. In many of their freedom dreams, co-researchers created items that were familiar to them, but also served a futuristic purpose to make society more just. In adrienne maree brown’s words, “We are imagining a world free of injustice, a world that doesn’t yet exist” (as cited in Love, 2019, p. 100). The results from this study support previous research that showed that a Black feminist curriculum builds critical consciousness (Lane, 2017). Abolitionist teaching also surfaced as how the co-researchers not only expressed what should be changed, but also what should be built in its place. It is through this creativity that activist and organizing demands are birthed and realized. The work the co-researchers did around Afrofuturism allowed us to reflect on what a world could look like if it were equitable and just. Through artwork, they are performing the future. Coupled with writing demands based on the Black Panther Party’s Ten Point Party Program, they began to draw and fight for worlds that are possible.

Specifically, they named how speaking up and sharing their stories are integral parts of how they will work to create new worlds. Similar to Toliver’s (2021b) finding that Black girls engaged in agitation literacies, literacies that agitate racism and oppression (Muhammad, 2019), the Black Girls S.O.A.R co-researchers named the importance of coalition-building to resist injustice, and even further, they centered intersectionality in their framing. They described their Afrofuturistic worlds as “all-inclusive” and that they welcome all people. In their 10-Point Demands, they modeled what that could look like by stating their desire to ban groups and ideologies that cause harm and oppression. This study adds to the growing body of literature that explores what abolitionist teaching looks like in practice by creating space to examine radical wonderings of the past and find themselves and freer futures through dreaming.

Implications

The literature that uses performance ethnography with Black girls in K-12 education continues to grow. Brown’s (2013) work offered a framework for using performance ethnography in research and programming with Black girls, and this study examines performance ethnography with Black girls in education research, which has implications for pedagogy and curriculum. While education literature on Black girls’ experiences incorporates art, specifically through the lens of literacy, there are more studies needed that use arts-based approaches as methodology. For example, many Black girl literacy studies incorporate artwork as literacy (Muhammad, 2012; Jacobs, 2016; Turner and Griffin, 2020), and this study adds to that body of work by using arts-based methodology to study art-making.

The co-researchers acknowledged the “curricular violence” (Jones, 2020) that occurs at school. Through their art, they depicted sadness, tears, and hurt, which is how they made meaning of the images they saw in school and in their textbooks. This is consistent with previous research that has shown that Black history curriculum is often only about enslavement (Mims and Williams, 2020), or a few figures, like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks, whose stories are depoliticized (Wineburg and Monte-Sano, 2008). In the co-researchers’ Ten Point Program (modeled after the Black Panther Party), they explicitly named their demand for curriculum, “We want to incorporate the teaching of Black history as a required course in the school system.” During a time where 42 states (and counting) have introduced or passed legislation that bans critical conversations about racism and oppression in schools, it is even more imperative that educators, administrators, and co-conspirators organize to ensure that Black history is taught in its entirety, including Black joy, Black creativity, and Black resistance.

Abolitionist teaching as a praxis centers Black joy and also provides space for students to disrupt the educational process and name what is not working for them. This study contributes to the growing body of literature that seeks to move abolitionist teaching from a theoretical concept to an empirical and practice-focused one. While abolitionist teaching has been applied to studies on civics education (Dozono, 2022), language arts and literacy in an urban school district (Hoffman and Martin, 2020), STEM (Jones, 2021; Louis and King, 2022), and teacher education (Faison and McArthur, 2020; Riley and Solic, 2021; Sabati et al., 2022), this study focused on Black girls and abolitionist teaching in an out-of-school setting. Because the out-of-school space is one not burdened by the bureaucracy of K-12 educational standards, it can serve as a site of the creative pedagogical experimentation that Rodríguez, 2010 named. In practice, abolitionist teaching could be seen as an embodiment of Sankofa. The literature underscores the need to examine Black girls’ arts-based practicesthrough a historical lens (Muhammad, 2012), through critical consciousness-building (Jacobs, 2016), and through dreaming imagined futures (Turner and Griffin, 2020; Toliver, 2021c). This study bridged these three areas together (i.e., past, present, and future) as abolitionist teaching in practice to create a curriculum aimed at Black girls negotiating and building their multi-layered identities while simultaneously crafting Black futures. Abolition and Afrofuturism, taken together, make us contend with the past to dream forward the future to then build coalition and incite action in the present.

Art and storytelling should be used in the classroom to invent new futures and take action toward ensuring those futures, as they are critical elements of abolitionist teaching. As Mims et al. (2022) warned, when using art, we cannot constrict Black art-making practices in rigid ways. Rather, we must invite them to engage in art-making practices that they gravitate toward. For example, Olivia chose poetry, while Camille and Mackenzie chose to draw with paper and coloring utensils and Jessie drew on her iPad. For Black girls, whose histories are often taught in schools through deficit-based narratives (Mims and Williams, 2020), the need to create and reauthor their personal and communal stories is an act of future-casting. To this end, Hill (2019) argued, “Those of us invested in Black girls’ livelihood must ask what they are experiencing and create space for them to tell us what they know about their lives, as well as what they need from us as educators, elders, activists and advocates” (p. 281).

Conclusion

We must support space for Black girls to explore and determine the fullness of their freedom dreams – from examining history, to refuting stereotypes, to creating their identities, to thinking about future aspirations, to dreaming a new world into existence, to developing demands to enact those futures. We also must not solely listen, but act in service of those demands. As Olivia wrote in the poem that opens this article, “I rewrote their story and you can, too.” She is asking educators to tell more fuller, nuanced stories of Black communities, as well as let Black girls write their own stories. She is asking for education to stop erasing, whitewashing, and misconstruing narratives to maintain hierarchies of oppression. This study provides an example of how curriculum can weave together history, present, and the future to ensure a full(er) examination of Black girls’ freedom dreams.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University of Maryland, College Park. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

This research was supported by funding from the Support Program for Advancing Research and Collaboration (SPARC) from the College of Education at the University of Maryland.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ Kyra Gaunt’s book The Games Black Girls Play (2006) explored Black and biracial adolescent girls’ experiences in a Michigan summer writing workshop. Gaunt (2006) argued how the games that Black girls learn when they are young (e.g., hands games and double dutch) are at the heart of historical and current Black music making. Hand games and double dutch are particularly important in understanding the arts-based practices of Black girls from a historical context.

- ^ Zoom is a video technology system where people can videochat in groups.

- ^ Serafini (2014) created a framework for interpreting visual images and multimodal ensembles. Turner and Griffin (2020) added intersectionality and participant interpretation to their analysis in a study that explored Black girls’ career dreams through multimodal compositions.

References

Annamma, S. A. (2017). The Pedagogy of Pathologization: Dis/abled girls of Color in the School-Prison Nexus. Milton Park: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315523057

Bell, D. A. (1995). Who’s Afraid of Critical Race Theory. U. Ill. L. Rev. Champaign: University of Illinois law Review.

Berry, D. R., and Gross, K. N. (2020). A Black Women’s History of the United States (Vol. 5). ReVisioning American History. Boston: Beacon Press.

Boyd Acuff, J. (2020). Afrofuturism: Reimagining art curricula for Black existence. Art Educ. 73, 13–21. doi: 10.1080/00043125.2020.1717910

Brown, C. A. (2015). BLACK GIRL: Linguistic play. Camille A. Brown. Available online at: http://www.camilleabrown.org/repertory/black-girl (accessed June 10, 2022).

Brown, R. N. (2013). Hear Our Truths: The Creative Potential of Black Girlhood. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. doi: 10.5406/illinois/9780252037979.001.0001

Charland, W. (2010). African American youth and the artist’s identity: Cultural models and aspirational foreclosure. Stud. Art Educ. 51, 115–133.

Collins, P. H. (1990). “Black Feminist thought in the Matrix of Domination,” in Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment, ed. P. H. Collins (Boston: Unwin Hyman), 221–238. doi: 10.1080/00393541.2010.11518796

Cooper, B. C. (2017). Beyond Respectability: The Intellectual Thought of Race Women. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. doi: 10.5406/illinois/9780252040993.001.0001

Cratsley (2017). Access to Arts Education: An Overlooked Tool for Social-Emotional Learning and Positive School Climate. Washington, DC: Every Student Succeeds Act.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critiqueof Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics Feministlegal Theory. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.2307/1229039

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 43, 1241–1299.

Critical Resistance (2020). Our Communities, our Solutions: An Organizer’s Toolkit for Developing Campaigns to Abolish Policing. New York, NY: Critical Resistance

Dando, M. B., Holbert, N., and Correa, I. (2019). “Remixing Wakanda: Envisioning critical Afrofuturist design pedagogies,” in Proceedings of FabLearn 2019, (Minnesota: St. Cloud State University), 156–159. doi: 10.1145/3311890.3311915

David, M. (2007). Afrofuturism and post-soul possibility in Black popular music. African Am. Rev. 41, 695–707. doi: 10.2307/25426985

Delgado, R. (1989). Storytelling for oppositionists and others: A plea for narrative. Michigan Law Rev. 87, 2411–2441. doi: 10.2307/1289308

Delgado, R., and Stefancic, J. (2001). Critical Race Theory: An Introduction. New York, NY: New York University Press. doi: 10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.51089

Denzin, N. K. (2003). Performance Ethnography: Critical Pedagogy and the Politics of Culture. California: Sage. doi: 10.4135/9781412985390

Denzin, N. K. (2009). A critical performance pedagogy that matters. Ethnogr. Educ. 4, 255–270. doi: 10.1080/17457820903170085

Desai, D., and Chalmers, G. (2007). Notes for a dialogue on art education in critical times. Art Educ. 60, 6–12. doi: 10.1080/00043125.2007.11651118