94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 04 November 2021

Sec. Teacher Education

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.774900

This article is part of the Research TopicTeaching History in the Era of Globalization: Epistemological and Methodological ChallengesView all 16 articles

A correction has been applied to this article in:

Corrigendum: Immigrant Students and the Swedish National Test in History

In Sweden, immigrant students with a non-European background perform worse in school than students from the majority group. Research has so far focused on language problems, and political investments have been concentrated around developing immigrant student’s language because it is hard to manage school without a functional language. However, social science in school also rests on cultural understanding, which is difficult if you are not a part of the culture. This is certainly true for the subject of history, which has a strong tradition of fostering a historical nationalistic canon. By analyzing the items in the national test in history relative to how the immigrant students perform, this study investigates whether there are certain types of items that, on the one hand, discriminate against them and, on the other hand, work to their advantage. This is important knowledge if we want to be able to make fair and just assessments.

2020 about two millions in Sweden were born in another country or both of their parents were born in another country, that is 19,7 per cent of the total population (SCB 2020a). From these about 600,000 are educated in compulsory education (SCB 2020b). Sweden has also for many decades received adolescents from countries outside Europe, and the biggest groups of migrants today come from Syria and Iraq. Migrant students are those students that are born outside Sweden or students with both their parents born outside Sweden (SCB 2020c). This means that students from neighbouring countries as Denmark and Norway counts as well. Nonetheless, knowledge of how to best educate migrant students in school is limited (Bunar, 2015). Consequently, Swedish research has shown that immigrant students feel excluded in regular education (Wigg, 2008; Skowronski, 2013; Nilsson, 2017; Sharif, 2017). At the same time, language difficulties make it hard for immigrant students to assimilate Swedish teaching (Cederberg, 2006; Gruber, 2007; Nilsson, 2017). Dveloping a functional language is of course an important factor for overall academic achievement (Collier and Thomas 2001; Clifford et al., 2013; Rhodes and Paxton 2013). Accordingly, teachers have low expectations of what immigrant students can learn and develop in school, and this, by extension, leads to a decreased motivation to do school work among immigrant students (Bunar, 2010). Meanwhile, their school results are getting worse (Grönqvist and Niknami, 2020).

Language difficulties play a major role in obstructing immigrant students from doing well in school (Hakuta et al., 2000). 1995 the course Swedish as a second language (SvA) was introduced in the curriculum for the compulsory school. Swedish as a second language is today the main way to integrate and give migrant students in Sweden equal opportunities in school. Swedish as a second language was introduced to give migrant students a Swedish language that were functional both in everyday life and to manage school and university studies. Students that have been in Sweden shorter than 4 years and that are born outside Europe are in majority in the group that follow the course Swedish as a second language. That said, some of the students are born in Sweden (Sahlée, 2017).

Nevertheless, except language problems, hegemonic cultural norms and expectations also make it difficult for migrant students to succeed in the Swedish school system (Hagström, 2018). Accordingly, immigrant student’s former experiences and knowledge should be considered as an asset in the teaching (Bouakaz and Taha, 2016; Lund and Lund, 2016). History didactic researchers have developed concepts that can help the history teacher to do this. Concepts such as historical culture, use of history, and historical consciousness can shed light on these processes (Alvén, 2021).

In this study, I analyze the type of items in the Swedish national test in history to investigate whether immigrant students perform better or worse on a certain type of items and, by extension, whether immigrant students have the same opportunity to show their historical knowledge as students from the majority group. To explain and define the problem, I use theories and results from the field of history didactics.

Rüsen (1988) claims that the experience of pluralism and multiculturalism in Europe has challenged the teaching of history in school in three ways. The first challenge is a crisis in national identity caused by the nation state no longer being the obvious starting point to identity as the EU-project continues to intensify and immigration from outside Europe continues to grow. The second challenge concerns cultural pluralism in the West due to globalism and long-distance immigration. Namely, the Other can today be your next door neighbor or your best friend in the class, and having alternative lifestyles so close may inspire or give you more choices of how to live your life and how to form your identity. Finally, a critique from other cultures and postmodern theories challenges what was earlier understood as Western ideals and held as truths and knowledge.

Altogether, these developments have presented a challenge to history teaching in the Western school because the subject has been used as a powerful instrument to shape patriotism and identification with the nation since the end of the 19th century (Berger and Lorenz, 2010; Carretero, 2011). From generation to generation, national narratives, legends, and myths have been transferred in school through history teaching. This has built up a cultural canon of important national themes, heroes, values, and expected behaviors (Barton and Levstik, 2004; Kessler and WongMing-Ji, 2009; Carretero, 2011). Via processes of justification and unjustification, this canon has legitimized the majority group’s identity and power. The Other has been described as alien to the nation and an illegitimate agent of nation-building (Korostelina, 2017). Thus, history has a strong tradition of constructing Us and Them.

When the nation-state is under question, as it often is today, the way history has usually been taught also becomes questioned (Rosa and Brescó, 2017). Seixas (2007) describes three different types of history teaching that can meet this challenge in the history classroom. The first is the collective memory approach, which transmits one national narrative without any competing perspectives. This is a strong way of forming a common identity; it corresponds with the traditional way of teaching history, even though the narrative’s message can be something other than nationalism, for example, democracy and solidarity. Another way of meeting the pluralistic history classroom is the disciplinary approach. In this approach, the students learn the historical method from the discipline of history and how to criticize history narratives; they also work with sources and evidence and are prepared to build their own historical accounts. The third approach is the postmodern one. This approach also contains different perspectives and narratives, but it goes one step further than just examining the trustworthiness for different narratives: it views and teaches history as something that serves different needs and purposes in the contemporary. Therefore, this approach brings a contemporary perspective in to the history classroom.

The postmodern approach can be fruitful in a pluralistic classroom where young people from minorities or with migrant backgrounds have experiences from both other historical cultures than the majority and other contemporary issues that are important to them (Virta, 2017). Moreover, substantial research indicates that student’s cultural background affects their understanding of history and what they perceive as important historical events. For example, Epstein (2000) shows that students with an African American background do not find school’s history teaching important to them, for they have other opinions about which historical events are relevant to them and their community. King (2019) even describes a certain black historical consciousness in the United States, with an ontology starting in black suffering and slavery. Barton and McCully (2005) report differences in how Protestant and Catholic students perceive the history of Northern Ireland. Another comparative study makes evident that students from minority groups in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Belgium find the history of religions more important than students from the majority groups (Grever et al., 2011). Nordgren (2006) and Lozic (2010) describe how students with immigrant backgrounds in Sweden sometimes feel excluded in history teaching and historical culture. Instead, minority students sometimes cultivate counter stories that break with the school’s narrative (Wertsch, 2000; Nordgren, 2006). Today, many researchers consider that a nationalist approach to teaching history belongs to the past—to a time when ethnically homogeneous nations were built with the help of a collective national master narrative (Carretero, 2017). In particular, this approach is criticized because it lacks cultural consciousness and multiple perspectives to understanding history, something that has led immigrant youth to experience difficulties fitting their own perspectives and experiences with those presented in the classroom (Gay, 2004). Metanarratives about a shared past can be strong among both majority and minority communities, but constructing narratives that can be shared by all is hard in a globalized and postmodern world (Grever, 2012).

The discipline of history evidently has its own problems when it comes to teaching pluralistic classrooms with a lot of immigrant students or students from minority groups. This complicates the process of assessing historical knowledge in the multicultural classroom. However, as Gay (2002) argues, to be effective and fair, assessment in such an environment should be based on the student’s ethnic identities, cultural orientations, and background experiences as much as possible. At the same time, (Stobart 2005, p. 282) states, There is no cultural neutrality in assessment or in the selection of what is to be assessed. This applies as much to mathematics as it does to history, and attempts to portray any assessment as acultural are a mistake.

I think Stobart is right; nevertheless, I argue that we cannot lean back and give up on striving for a fair and just assessment in pluralistic environments. If we believe history is closely connected to our identity and at the same time do not approve some historical perspectives because of another cultural starting point, by extension, this means that we deny certain identities. This is a much more severe problem than denying certain knowledge (in mathematics, for example), and it contradicts the effort to achieve a well-functioning pluralistic society.

Nonetheless, the problem of biased assessment is not isolated to history teaching. Malouff and Thorsteinsson (2016) meta-analysis, representing 20 studies and a total of 1,935 graders, reveals certain categories of students that are exposed to biased grading to a high degree. These categories mostly comprise students labeled with negative a negative behaviour, students who are already known to perform poorly, and students who are perceived as physically less attractive by the graders; however, students belonging to specific ethnic groups are also exposed to biased grading in a high degree. On the other hand, Fajardo (1985) shows that students from minorities may get both higher and lower grades than other students due to bias. Malouff and Thorsteinsson (2016) suggest that keeping students anonymous during grading may be a way to counteract bias in grading (see also Brennan, 2008; Kahneman, 2011). This can help when the bias stems from the student’s characteristics; however, it will not help if the bias is located in the student’s responses rather than in the students themselves.

Some researchers have investigated grading bias regarding content that impugns cultural values or cultural ontological starting points. For example, Davidson et al. (2000) present statistically significant results indicating that graders gave nonviolent content in essays higher grades than violent content, although neither were criteria for grading. Researchers using verbal protocol methodology and anonymous student responses have identified that graders show strong emotions while assessing student’s responses (Crisp, 2008, 2012; Alvén, 2017). Graders expressed feelings of pleasure, dislike, and sympathy, and in some cases, they talked to an imagined stereotyped student congruent to the student response. Further, research has been conducted that analyzes how historical content and values in student responses affects grading. This research indicates that responses containing perspectives and values that are not common in the majority historical culture both perplex the graders and are graded lower (Alvén, 2017; Alvén, 2019).

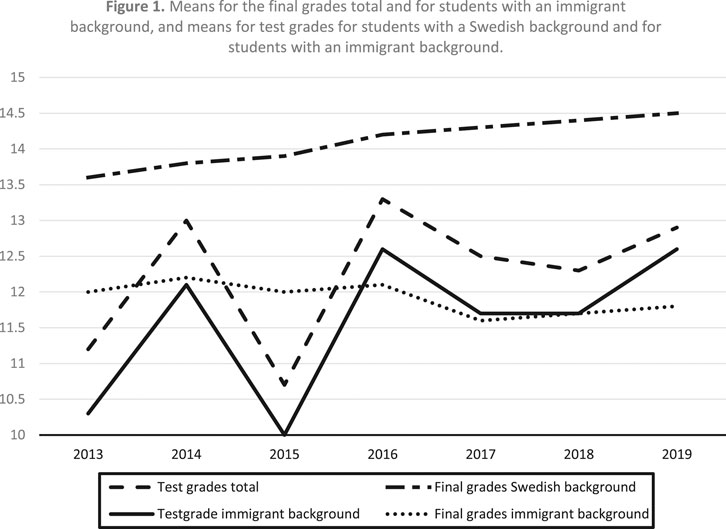

How do immigrant students manage the subject of history in the Swedish school then? The statistical data base SiRiS at The National Agency for Education in Sweden has been used to construct Figure 1. Each grade renders points in the data base: A is 20, B is 17.5, C is 15, D is 12.5, E is 10, and F (not approved) is 0. The value for each year, 2013–2019, is the mean for the final grades and the results of the national test in history for students with an immigrant background and students with a Swedish background. The national test in history is written during the last term of the compulsory school and is supposed to support the final grade. Figure 1 shows a striking picture. When it comes to history in the compulsory school in Sweden, students with a Swedish background have received better final grades than immigrant students in the examined period. This confirms previous research. The results for the national test in history show the same tendency. However, for the immigrant students, the difference between the results of the national test in history and the final grades is much less than for the other group. Students with a Swedish background have much higher final grades than national test results for the whole period, 2013–2019. This is congruent with other national tests in Sweden. However, this is not the case for students with an immigrant background. From 2016 onward, immigrant students have had better national test grades than final grades. Nonetheless, they perform worse in the national test in history than the students with a Swedish background. This study investigates whether there is something in the national test items themselves that can help us understand the connection between assessment, bias, and immigrant student’s performances in history. The findings may also give us clues about how to assess history knowledge with less bias against students with an immigrant background.

FIGURE 1. Means for the final grades total and for students with an immigrant background, and means for test grades for students with a Swedish background and for students with an immigrant background.

There is solid research showing that language difficulties impede students with an immigrant background from performing well in school generally and in history specifically (Schleppegrell, 2001; Bernhardt, 2003; Coffin, 2006). Some research about school performance in history nuances this picture. For instance, De La Paz’ (2005) research shows small differences between first and second language students in the ability to construct texts in the subject of history. In a Swedish context, Olvegård (2014) had a similar result when studying the students’ reading abilities. Meanwhile, Alvén (2011) shows possible ways of assessing historical knowledge true to the curriculum, where students with an immigrant background perform on the same level as students with a Swedish background, or even better in some cases. Such results call for research that tries to find other explanations than language difficulties for why immigrant students perform much worse in school in the subject of history.

The empirical material in the study is the Swedish national test in history. The test is performed during the last term in compulsory school, when the students are 15–16 years old. The test is constructed with the syllabus in history for the compulsory school as a starting point. According to the syllabus four abilities are supposed to be developed in the history classes. These are the students’ ability to:

• use a historical frame of reference that incorporates different interpretations of time periods, events, notable figures, cultural meetings and development trends,

• critically examine, interpret and evaluate sources as a basis for creating historical knowledge,

• reflect over their own and other’s use of history in different contexts and from different perspectives, and

• use historical concepts to analyse how historical knowledge is organised, created and used.

For each ability there is knowledge requirements in three qualitative steps as a help to grade the student’s knowledge. The progression to assess the ability for source critiscism for example looks as follows in ninth grade:

• Pupils can use historical source material to draw simple and to some extent informed reasoning about people’s living conditions, and apply simple and to some extent informed reasoning about the credibility and relevance of sources.

• Pupils can use historical source material to draw developed and relatively well informed conclusions about people’s living conditions, and apply developed and relatively well informed reasoning about the credibility and relevance of their sources.

• Pupils can use historical source material to draw well developed and well informed conclusions about people’s living conditions, and apply well developed and well informed reasoning about the credibility and relevance of various sources.

In the syllabus there is also a core content. For the students aged 13–16 the headlines in the core content are these:

• Ancient civilisations, from prehistory to around 1700

• Industrialisation, social change and leading ideas about 1700–1900

• Imperialism and world wars about 1800–1950

• Democratisation, the post-war period and globalisation, from around 1900 to the present

• How history and historical concepts are used (Skolverket, 2011)

Each year, Malmö University, where the test also is constructed, collects data from the test results on a platform. The sample contains the results of every student born on a certain date. Approximately 25,000 students take the test in history every year. The sample collected each year comprises the results of about 1,500–2,000 students, about six to eight percent of the total population (see Table 1). The sample is also randomized and considered representative. The statistical data collected with the sample show the student’s results for each item in the test, their test grade, their gender, and whether they take the standard Swedish course or the course for Swedish as a second language. Students that have a language other than Swedish as their first language can take the course Swedish as a Second Language, SvA. The principal at each school decides whether a student should take this course or not. The principal can also decide whether the student has a language level that allows him or her to take the national test. Accordingly, new arrivals are not likely to take the test. Students who take the course SvA and have taken the national test in history have thus been assessed as having a language level good enough to take the test.

TABLE 1. Number of collected results and the distribution between students taking the course Swedish and Swedish A, SvA.

There is no information about who is taking the course Swedish as a Second Language, SvA. There are indications however that the majority of students taking the course have a non-European background, including those born both in and outside Sweden (Sahlée, 2017).

In the national test in history, students do not collect points but proof of quality for each item. There are knowledge requirements in the Swedish curriculum for compulsory school to help teachers assess the students. The knowledge requirements comprise three levels describing different qualities; these levels correspond to the grades E, C, and A, where A is the best grade. In the statistical material collected for this studt, the proof of quality for each item receives zero points if not approved, one point for the first level, two points for the second, and three for the best level. This means a student can never have more than three points on an item, which corresponds to the highest level for the knowledge requirements (i.e., grade A).

Figure 1 already shows that the students taking the course Swedish as a Second Language, SvA, perform worse on the national test in history and also have worse final grades in history from the compulsory school than the majority group. However, the difference in the national test results between the two groups of students is smaller than the difference in the final grades. It also seems that the gap in national test results of the two groups has gotten smaller at the end of the studied period, 2013–2019. These conditions make the following research questions relevant:

• Are there types of test items that make immigrant students (those taking SvA) perform better or worse?

• If so, are there some common patterns in these items?

This study uses a differential item functioning (DIF) analysis to identify those test items for which different groups of students perform differently. It encompasses a set of approaches for comparing the performance of groups on individual items while simultaneously considering the students’ potential to score well on the test. Hence, a DIF analysis is more useful than comparing total scores for identifying differences between groups taking a test (Martinková et al., 2017). It can identify differences that are not revealed when comparing total scores. However, a DIF analysis can be interpreted in different ways, and this study employs the categories that the Educational Testing Service (ETS) uses (see Zwick, 2012).

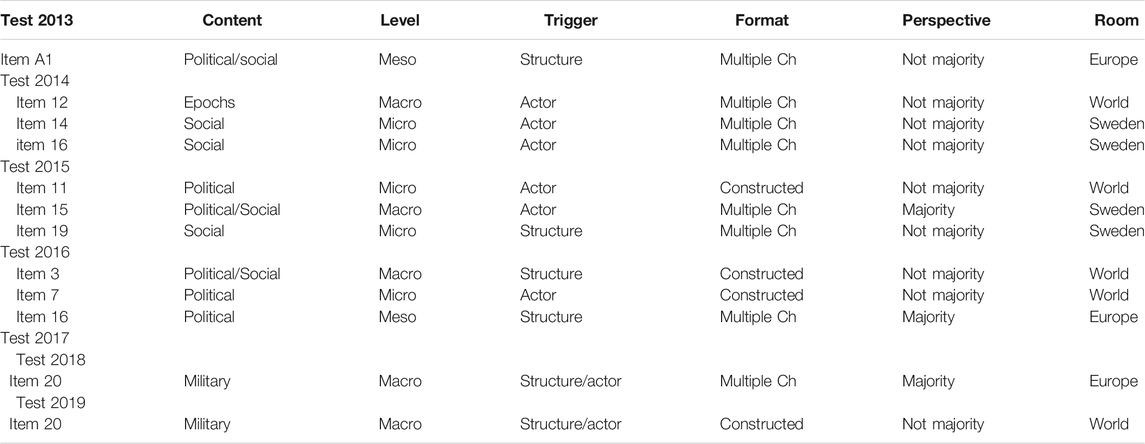

After identifying test items where immigrant students performed better, the items were analyzed. The professors in history didactics Ammert and Eliasson (2019) have evaluated the content and form of national history tests between the years 2013 and 2017 using a specific model. This study uses the categories from their model but with some additions (see Table 2). The category Content includes political/ideological, military, or social history and knowledge about epochs. In the category Level, “macro” refers to history with consequences for several countries, “meso” for regions, and “micro” for local places. The category Trigger is about what forces history to become, actors or structures? Format is either multiple-choice questions or constructed responses. Two categories are added to Ammert’s and Eliasson’s model: Perspective and Room. Research indicates that minorities often feel that history taught in school is the history of the national majority’s canon (Epstein 2000, 2007). The category Perspective determines whether the item is understood as history from the majority’s canon or not; namely, does a certain item contain relevant perspectives for students not belonging to the majority group? On the other hand, it is hard to define a canon. Seixas (2007) sees it as national heroes and “a widely shared, coherent narrative, generally revolving around nation-building and social, economic and political progress” (p. 19). It is a narrative acknowledged by the majority of a community to represent its common past. However, migration, globalization, and post-colonization today challenge the canon and history education, and the nation-state is no longer the obvious foundation for history education (Grever and Stuurman, 2007). Hence, if an item assumes a national or Western perspective that immigrant groups do not self-evidently share with the majority, the item is categorized as having a majority perspective. On the other hand, if an item addresses a history topic from a minority perspective or permits different perspectives, it is categorized as a non-majority perspective. Research has also shown that immigrant students call for history from other places than Sweden and Europe (Lozic, 2010; Johansson, 2012). The category Room helps identify whether the item contains history from Sweden, Europe, or somewhere else in the world.

Unfortunately, the tests are confidential for 5 years, which makes it hard to discuss the specific items in detail. However, the study can and will address items in the tests performed in 2013 and 2014.

Table 3 shows each test item that has benefited students taking the course Swedish as a Second Language, SvA. For most of the analysis categories, there are no obvious similarities between the items. Regarding the content of the items, it differs between political, social, and military. The levels micro, meso, and macro are also all represented in the tests. What triggers historical events in these items are actors, structures, and actors acting inside structures. The format of the items is both constructed and multiple choice, but the majority are multiple-choice questions. If students with a Swedish background performed better on constructed responses, we could understand the other group’s struggle as a language problem, but that is not the case. When it comes to the room category, referring to the geographical location of the history topic in the item, Sweden, Europe, and the world are all well represented. However, one of the categories, perspective, shows similarities between almost all of the items, favoring the immigrant students. Nine out of twelve of the items in this category have a perspective that is not easily understood as a natural part of the Swedish historical canon.

TABLE 3. Tests and items with a DIF that favors the students taking the course Swedish as a second language, Sva.

As mentioned before, only the items from the 2013 and 2014 tests can be presented here due to confidentiality reasons. Item A1 from the test year 2013 addresses democracy in ancient Athens. What makes the item understandable from a different perspective is the explicit emphasis that a lot of people were not included in the Athenian democratic society, among them immigrant non-citizens. Item 12 from the test year 2014 discusses the Cold War, and the text in the item does not take a stand or present the perspective of either side of the war. Items 14 and 16 in the test from 2014 ask the students to identify stereotypes and discrimination against the Romani people in Sweden during the 19th and 20th centuries.

Let us have a closer look at item 14 from the test performed in 2014 (see Figure 2). The students are supposed to read an excerpt from an old Swedish novel from 1847. Using the excerpt as a historical source, they are supposed to see that the position in the public cultural debate regarding the Romani people was very different from today and that it was not strange to describe Romani people as thieves. The perspective of course shows a vulnerable minority, a commonality in many of the items that the immigrant students perform well on. Another interesting aspect is the format: the students must not only read a text from a novel, they must also be able to both handle a text genre from another field (i.e., literature) than the typical historical and interpret and see inferences in this text. It is a fairly linguistic ability that the immigrant students are able to use, so they perform better on this item than many others, which challenges the conclusion that it always is poor language that explains immigrant students’ poor results in school.

Table 4 shows every item that has benefited students taking the course Swedish in each test. For most of the categories, there are no obvious similarities between these items. When it comes to the content of the items, it differs between political, social, and military. The levels micro, meso, and macro are all represented. What triggers historical events in these items are both actors and structures. The format of the items is both constructed and multiple-choice questions, but with a majority of multiple-choice questions. When it comes to the room, all three sub-categories (Sweden, Europe, and the world) are well represented, but items taking place in the world are fewer than items taking place in Sweden and Europe. In the perspective category, there are similarities between almost all of the items favoring the students taking the Swedish course. Most of the items (22 out of 24) reflect a majority perspective or can be perceived as a natural part of a Swedish historical canon.

When analyzing the items that favor the majority group some categories stand out. Items A10, A12, and B7 from the test year 2013 and item 6 from the test year 2014 ask for knowledge about a topic within the traditional canon of the Western world or Sweden. Industrialization and the emergence of the Swedish welfare society figure in these items. Items B1, B4, and B9 in the test from the year 2013 and items 1 and 8 in the test from 2014 all demand knowledge about a typical Swedish identity, today and in the past. All of them ask the students to understand that what was once considered as normal in Swedish society no longer is. Such items assume qualified knowledge about the nation’s social and cultural history, a knowledge hard to acquire without having grown up or lived a long time in the country. Figure 3 shows item 8 from the test year 2014. The picture shows a man looking at a woman flogging a child, which was a normal thing to do a hundred years ago in Sweden. The students have three alternatives of what the man is saying to the woman flogging the child, and they have to choose the most reasonable one. Two alternatives are typical of Swedish values today and one representing a value from a hundred years ago. Implicitly, the item contrasts a past opinion to the opinion that dominates in Sweden today: we do not flog children. However, this is not an opinion that dominates all cultures in the world, which of course makes the question harder to understand for non-Swedish students. This means that the item requires the students to understand the world as a typical native Swedish student would.

Today schools in Europe, not least in Sweden, face a big challenge when it comes to educating students with a non-European immigrant background. It is an urgent societal concern, as a big ethnic community is failing in school and cannot compete for jobs with high status and good wage. Nevertheless, our knowledge about how to educate these students is modest (Bunar, 2015). One apparent key to success is language: you must master the majority language to perform well in school (Hakuta et al., 2000). So far, much political investment has centered on language development for immigrant students. Moreover, most of the research has focused on how to develop these students’ language ability.

At the same time the subject of social studies in school has been especially criticized for not dealing with knowledge differences between students from the majority group and immigrant and minority students (Ladson-Billings, 2003; Nelson and Pang, 2006). These problems are made visible in a lack of stories, perspectives, and voices from immigrant students in the teaching of social studies (Salinas et al., 2007), as well as ignorance of cultural and ethnic consciousness and differences in the curricula (Banks, 2007). This is said to drive immigrant students to perceive social studies learning as meaningless and irrelevant to their own lives (Almarza, 2001; Halagao, 2004). Social studies in school are even accused of reinforcing White and Eurocentric standpoints (Bolgatz, 2005). However, we know very little of how the immigrant background affects these students’ learning and how social studies can better serve their needs (Salinas, 2006; Subedi, 2008; Bunar, 2015). According to Shulman (1986), pedagogical content knowledge is a fruitful starting point. This means more than understanding a subject from an academic discipline perspective. Instead, we must understand that a school subject is a unique construction that must take into account, on the one hand, the academic discipline that the school subject is derived from and, on the other, the learning theories and the school’s mission to both develop knowledge and foster citizens.

History didactics can help us understand how the subject works in the pluralistic history classroom—in terms of both understanding history teaching as a cultural phenomenon (Rüsen, 1988; Alvén, 2021) and learning how to deal with this fact in the multicultural classroom (Nordgren and Johansson, 2015; Nordgren 2017). Such changes in history teaching must also include how we, in a just and fair way, assess and grade history in school. If not, the problem of an excluded group of students based on ethnicity will continue. This study has shown that immigrant students perform better when they are assessed on history topics that open up for several perspectives and on a history that is not closed to a national canon. This is important knowledge if we want to include these students in history teaching. Meeting this need is not impossible if our goal is to actually develop the students’ historical abilities, and not a declarative knowledge that asks them to repeat and embrace a national story. Indeed, seeing different perspectives, interpreting historical events and sources with the help of second-order concepts, and reasoning about the use of history are not bound to a Western historical canon.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Grant PID2020-113453RB-I00 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033. HistoryLab Project. Reference: 2020-1-ES01-KA226-HE-095430. Fund entity: Erasmus + KA226. National Project: La enseñanza y el aprendizaje de competencias históricas en bachillerato: un reto para lograr una ciudadanía crítica y democrática. Reference: PID 2020-113453RB-I00. Fund entitiy: Agencia Estatal de Investigación, Spain, and Fair assessment in the national test in history. Subsidized by the Crafoord Foundation, Sweden.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Almarza, D. J. (2001). Contexts Shaping Minority Language Students' Perceptions of American History. J. Soc. Stud. Res. 25 (2), 4–22.

A. Lund, and S. Lund (Editors) (2016). Skolframgång I Det Mångkulturella Samhället (Lund: Studentlitteratur).

Alvén, F. (2019). Bias in Teachers´ Assements of Students´ Historical Narratives. Hist. Edu. Res. J. 16 (2), 306–321. doi:10.18546/herj.16.2.10

Alvén, F. (2011). Historiemedvetande På Prov. En Analys Av Elevers Svar På Uppgifter Som Prövar Strävansmålen I Kursplanen För Historia. Lund: Lunds Universitet/Malmö Högskola.

Alvén, F. (2021). Opening or Closing Pandora's Box? - Third-Order Concepts in History Education for Powerful Knowledge. FdP 12, 245–263. doi:10.14201/fdp202112245263

Alvén, F. (2017). Tänka Rätt Och Tycka Lämpligt: Historieämnet I Skärningspunkten Mellan Att Fostra Kulturbärare Och Förbereda Kulturbyggare. Malmö: Malmö Högskola.

Ammert, N., and Eliasson, P. (2019). Externa Historieprov. En Studie Av Validitetsfrågor. Malmö: Malmö Universitet.

Banks, J. A. (2007). Educating Citizens in a Multicultural Society. New York: Teachers College Press.

Barton, K. C., and Levstik, L. S. (2004). Teaching History for the Common Good. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Barton, K. C., and McCully, A. W. (2005). History, Identity, and the School Curriculum in Northern Ireland: an Empirical Study of Secondary Students' Ideas and Perspectives. J. Curriculum Stud. 37, 85–116. doi:10.1080/0022027032000266070

Bernhardt, E. (2003). Challenges to reading Research from a Multilingual World. Reading Res. Q. 38 (1), 112–117.

Bolgatz, J. (2005). Revolutionary Talk: Elementary Teacher and Students Discuss Race in a Social Studies Class. Soc. Stud. 96 (6), 259–264. doi:10.3200/tsss.96.6.259-264

Bouakaz, L., and Taha, R. (2016). “Kampen om att bli en elev,” in Skolframgång I Det Mångkulturella Samhället. Editors A. Lund, and S. Lund (Lund: Studentlitteratur), 85–102.

Brennan, D. J. (2008). University Student Anonymity in the Summative Assessment of Written Work. Higher Edu. Res. Develop. 27 (1), 43–54. doi:10.1080/07294360701658724

Bunar, N. (2010). The Geographies of Education and Relationships in a Multicultural City. Acta Sociologica 53 (2), 141–159. doi:10.1177/0001699310365732

Carretero, M. (2011). Constructing Patriotism. Teaching History and Memories in Global Worlds. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Carretero, M. (2017). “Teaching History Master Narratives: Fostering Imagi-Nations,” in Palgrave Handbook of Research in Historical Culture and Education. Editors M. Carretero, S. Berger, and M. Grever (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 511–528. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-52908-4_27

Cederberg, M. (2006). Utifrån Sett – Inifrån Upplevt: Några Unga Kvinnor Som Kom till Sverige I Tonåren Och Deras Möte Med Den Svenska Skolan. Malmö: Malmö Högskola.

Clifford, V., Rhodes, A., and Paxton, G. (2013). Learning Difficulties or Learning English Difficulties? Additional Language Acquisition: An Update for Paediatricians. J. Paediatr. Child. Health 50 (3), 175–181. doi:10.1111/jpc.12396

Coffin, C. (2006). Learning the Language of School History: The Role of Linguistics in Mapping the Writing Demands of the Secondary School Curriculum. J. Curriculum Stud. 38 (4), 413–429. doi:10.1080/00220270500508810

Collier, V. P., and Thomas, W. P. (2001). Educating Linguistically and Culturally Diverse Students in Correctional Settings. J. Correctional Edu. 52 (2), 68–73. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23292219.

Crisp, V. (2012). An Investigation of Rater Cognition in the Assessment of Projects. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 31 (3), 10–20. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3992.2012.00239.x

Crisp, V. (2008). Exploring the Nature of Examiner Thinking during the Process of Examination Marking. Cambridge J. Edu. 38 (2), 247–264. doi:10.1080/03057640802063486

Davidson, M., Howell, K. W., and Hoekema, P. (2000). Effects of Ethnicity and Violent Content on Rubric Scores in Writing Samples. J. Educ. Res. 93 (6), 367–373.

De La Paz, S. (2005). Effects of Historical Reasoning Instruction and Writing Strategy Mastery in Culturally and Academically Diverse Middle School Classrooms. J. Educ. Psychol. 97 (2), 139–146. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.97.2.139

E. H. Kessler, and D. J. WongMing-Ji (Editors) (2009). Cultural Mythologyand Global Leadership (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar).

Epstein, T. (2000). Adolescents' Perspectives on Racial Diversity in U.S. History: Case Studies from an Urban Classroom. Am. Educ. Res. J. 37, 185–214. doi:10.3102/00028312037001185

Epstein, T. (2007). The Effects of Family/community and School Discourses on Children’s and Adolescents’ Interpretations of United States History. Int. J. Hist. Learn. Teach. Res. 6, 1–9. doi:10.18546/HERJ.06.0.04

Fajardo, D. M. (1985). Author Race, Essay Quality, and Reverse Discrimination. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 15 (3), 255–268. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1985.tb00900.x

Gay, G. (2002). Culturally Responsive Teaching in Special Education for Ethnically Diverse Students: Setting the Stage. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Edu. 15 (6), 613–629. doi:10.1080/0951839022000014349

Gay, G. (2004). “Social Studies Teacher Education for Urban Classrooms,” in Critical Issues in Social Studies Teacher Education. Editor S. Adler (Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

G. Ladson-Billings (Editor) (2003). Critical Race Theory Perspectives on Social Studies: The Profession, Policies and Curriculum (Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing).

Grever, M. (2012). “Dilemmas of Common and Plural History. Reflections on History Education and Heritage in a Globalizing World,” in History Education and the Construction of National Identities. Charlotte: IAP. Editors M. Carretero, M. Asensio, and M. Rodrigues-Monea.

Grever, M., Pelzer, B., and Haydn, T. (2011). High School Students' Views on History. J. Curriculum Stud. 43 (2), 207–229. doi:10.1080/00220272.2010.542832

Grönqvist, H., and Niknami, S. (2020). Studiegapet Mellan Inrikes Och Utrikes Födda Elever. Stockholm: SNS Förlag.

Gruber, S. (2007). Skolan Gör Skillnad: Etnicitet Och Institutionell Praktik. Linköping: Linköpings universitet.

Hagström, M. (2018). Raka Spår, Sidospår, Stopp: Vägen Genom Gymnasieskolans Språkintroduktion Som Ung Och Ny I Sverige. Linköping: Linköpings universitet.

Hakuta, K., Butler, G. Y., and Witt, D. (2000). How Long Does it Take English Learners to Attain Prociency? Policy Report 2000-1. Irvine, CA: University of California, Linguistic Minority Research Institute.

Halagao, P. E. (2004). Holding up the Mirror: The Complexity of Seeing Your Ethnic Self in History. Theor. Res. Soc. Edu. 32 (4), 459–483. doi:10.1080/00933104.2004.10473265

Johansson, M. (2012). Historieundervisning Och Interkulturell Kompetens. Karlstad: Karlstads universitet.

King, L. G. J. (2019). “What Is Black Historical Consciousness?,” in Contemplating Historical Consciousness. Notes from the Field. Editor A. C. L. ClarkPeck (New York: Berghahn).

Korostelina, K. V. (2017). Constructing Identity and Power in History Education in Ukraine: Approaches to Formation of Peace Culture. Editors M. Carretero, S. Berger, and M. Grever (London: Palgrave MacMillan).

Lozic, V. (2010). I Historiekanons Skugga: Historieämne Och Identifikationsformering I 2000-talets Mångkulturella Samhälle. Malmö: Lunds universitet.

Malouff, J. M., and Thorsteinsson, E. B. (2016). Bias in Grading: A Meta-Analysis of Experimental Research Findings. Aust. J. Edu. 60 (3), 245–256. doi:10.1177/0004944116664618

Martinková, P., Drabinová, A., Liaw, Y. L., Sanders, E. A., McFarland, J. L., and Price, R. M. (2017). Checking Equity: Why Differential Item Functioning Analysis Should Be a Routine Part of Developing Conceptual Assessments. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 16 (2), 2017. doi:10.1187/cbe.16-10-0307

M. Grever, and S. Stuurman (Editors) (2007). Beyond the Canon. History for the Twenty-First Century (New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Nelson, W., and Pang, V. O. (2006). “Racism, Prejudice, and the Social Studies Curriculum,” in The Social Studies Curriculum: Purposes, Problems, and Possibilities. Editor E. W. Ross (Albany: State University of New York Press), 115–136.

Nilsson, F. J. (2017). Lived Transitions: Experiences of Learning and Inclusion Among Newly Arrived Students. Stockholm: Stockholms universitet.

Nordgren, K., and Johansson, M. (2015). Intercultural Historical Learning: a Conceptual Framework. J. Curriculum Stud. 47 (1), 1–25. doi:10.1080/00220272.2014.956795

Nordgren, K. (2017). Powerful Knowledge, Intercultural Learning and History Education. J. Curriculum Stud. 49 (5), 663–682. doi:10.1080/00220272.2017.1320430

Nordgren, K. (2006). Vems Är Historien? Historia Som Medvetande, Kultur Och Handling I Det Mångkulturella Sverige. Umeå: Karlstad Universitet.

Olvegård, C. (2014). Herravälde. Är Det Bara Killar Eller? Andraspråksläsare Möter Lärobokstexter I Historia För Gymnasieskolan. Göteborg: Göteborgs Universitet.

Rosa, A., and Brescó, I. (2017). “What to Teach in History Education when the Social Pact Shakes,” in Palgrave Handbook of Research in Historical Culture and Education. Editors M. Carretero, S. Berger, and M. Grever (London: Palgrave MacMillan).

Rüsen, J. (1988). Functions of Historical Narration. Proposals for a Strategy Og Legitimating History in School. Malmö: Lärarhögskolan i Malmö.

Sahlée, A. (2017). Språket Och Skolämnet Svenska Som Andraspråk. Om Elevers Språk Och Skolans Språksyn. Uppsala: Uppsala Universitet.

Salinas, C. (2006). Educating Late Arrival High School Immigrant Students: A Call for a More Democratic Curriculum. Multicultural Perspect. 8 (1), 20–27. doi:10.1207/s15327892mcp0801_4

Salinas, C., Sullivan, C., and Wacker, T. (2007). Curriculum Considerations for Late-Arrival High School Immigrant Students: Developing a Critically Conscious World Geography Studies Approach to Citizenship Education. J. Border Educ. Res. 6 (2), 55–67.

S. Berger, and C. Lorenz (Editors) (2010). Nationalizing the Past. Historians as Nation Builders in Modern Europe (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan).

Scb (2020a). Statistiska Centralbyran (SCB). Available at: https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/sverige-i-siffror/manniskorna-i-sverige/utrikes-fodda/2021-10-18.

Scb (2020b). Statistiska Centralbyran (SCB). Available at: http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/START__BE__BE0101__BE0101Q/UtlSv BakgFin/table/tableViewLayout1/2021-10-18.

Scb (2020c). Statistiska Centralbyran (SCB). Available at: https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/sverige-i-siffror/manniskorna-i-sverige/utrikes-fodda/2021-10-18.

Schleppegrell, M. J. (2001). Linguistic Features of the Language of Schooling. Linguistics Educ. 12 (4), 431–459. doi:10.1016/s0898-5898(01)00073-0

Seixas, P. (2007). “Who Needs a Canon?,” in Beyond the Canon. History for the Twenty-First Century. Editors M. Grever, and S. Stuurman (New York: Palgrave MacMillan).

Sharif, H. (2017). Här I Sverige Måste Man Gå I Skolan För Att Få Respekt – Nyanlända Ungdomar I Den Svenska Gymnasieskolans Introduktionsutbildning. Uppsala: Uppsala universitet.

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those Who Understand: Knowledge Growth in Teaching. Educ. Res. 15 (2), 4–14. doi:10.3102/0013189x015002004

Skolverket (2011). Läroplan För Grundskolan, Förskoleklassen Och Fritidshemmet 2011. Stockholm: Skolverket.

Skowronski, E. (2013). Skola med fördröjning: nyanlända ungdomars sociala spelrum i ”en skola för alla”. Lund: Lunds universitet.

Stobart, G. (2005). Fairness in Multicultural Assessment Systems. Assess. Educ. Principles Pol. Pract. 12 (3), 275–287. doi:10.1080/09695940500337249

Subedi, B. (2008). Fostering Critical Dialogue across Cultural Differences: A Study of Immigrant Teachers' Interventions in Diverse Schools. Theor. Res. Soc. Edu. 36 (4), 413–440. doi:10.1080/00933104.2008.10473382

Wertsch, J. V. (2000). “Is it Possible to Teach Beliefs, as Well as Knowledge about History?,” in Knowing, Teaching, and Learning History: National and International Perspectives. Editors P. N. Stearns, P. Seixas, and S. Wineburg (New York: New York University Press), 38–50.

Wigg, U. (2008). Bryta Upp Och Börja Om: Berättelser Om Flyktingskap, Skolgång Och Identitet. Linköping: Linköpings universitet. Malmö.

Keywords: history teaching, national test, assessment, grading, multicultural teaching

Citation: Alvén F (2021) Immigrant Students and the Swedish National Test in History. Front. Educ. 6:774900. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.774900

Received: 13 September 2021; Accepted: 22 October 2021;

Published: 04 November 2021.

Edited by:

Pilar Rivero, University of Zaragoza, SpainReviewed by:

Pedro Paulo Funari, State University of Campinas, BrazilCopyright © 2021 Alvén. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fredrik Alvén, ZnJlZHJpay5hbHZlbkBtYXUuc2U=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.