- Science news

- Featured news

- What do you think ‘guilty’ sounds like? Scientists find accent stereotypes influence beliefs about who commits crimes

What do you think ‘guilty’ sounds like? Scientists find accent stereotypes influence beliefs about who commits crimes

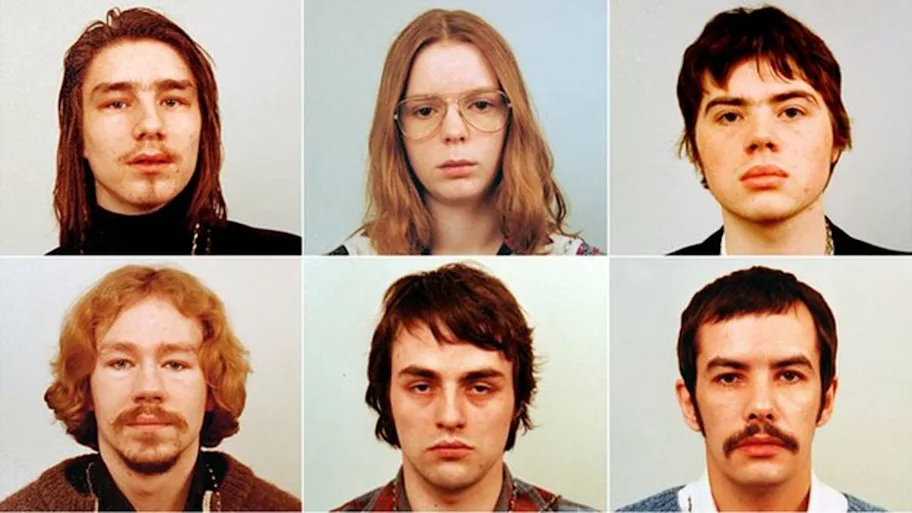

Scientists studying the dynamics involved in voice identity parades show that the accent-based assumptions people make about behaviors or values also translate into assumptions about how likely a person is to have committed a crime. Accents accorded higher status were rated less likely to have committed crimes. If these biases are repeated in real-life voice identity parades and other interactions with the justice system, this could negatively affect defendants’ chances of a fair trial. However, some positive assumptions were also made about accents associated with specific criminal or ambiguous behaviors, while some negative assumptions were made about prestigious accents.

The way you talk says a lot about you — but what people think it says may not be true. While no accent is better than any other, people use accents as markers for identifying and stereotyping social groups. In the justice system, these accent stereotypes could influence perceptions of guilt, leading to discrimination. Scientists collaborating on the Improving Voice Identification Procedures project explored this by testing participants’ perceptions of ten different accents heard around the UK. They found that speakers with accents considered lower-status were considered more likely to have committed crimes.

“We found a strong link between perceived social status and the perceived likelihood of committing crimes,” said Alice Paver of the University of Cambridge, lead author of the study in Frontiers in Communication. “This link was more important than how trustworthy, kind or honest someone was perceived to be. This shows that perceived social class, as judged from a speaker’s accent, is an important predictor of UK listeners’ expectations about behavior, and this might have serious implications in the criminal justice system.”

Anti-social accents?

Paver and her colleagues — Dr David Wright, Professor Natalie Braber, and Dr Nikolas Pautz of Nottingham Trent University — recruited 180 participants from all over the UK and assigned them to one of two surveys. The first asked participants to rate voices according to 10 social traits, while the second asked participants to rate how likely the voices were to have performed 10 behaviors — five different crimes and five moral behaviors, like defending a victim of harassment or cheating on your partner.

The scientists created 30-second collages from recordings of men speaking English in 10 accents: Belfast, Birmingham, Bradford, Bristol, Cardiff, Glasgow, Liverpool, London, Newcastle, and Standard Southern British English (SSBE). To minimize outside influences, the scientists removed names and standardized the collages for speed, pitch, and intensity of speech. The samples were also reviewed by phoneticians to ensure they accurately reflected how most people with these accents speak.

The scientists then analyzed the participants’ responses to look for patterns. They found two major clusters of traits, which they named ‘solidarity’ — traits like kindness — versus ‘status’ — traits like wealth — as well as two minor clusters, labelled ‘confident’ and ‘working class’. The last cluster was the exact opposite of the ‘status’ cluster. SSBE was most highly rated on ‘status’ traits, as well as the ‘confident’ cluster, and the lowest rated in the ‘working class’ cluster.

Read and download the original article

All the crimes, except for sexual assault, clustered together. The higher an accent was rated for status, the lower it was rated for criminal acts. Sexual assault clustered with negative behaviors which weren’t necessarily illegal, so the authors labelled this cluster of behaviors as ‘morally bad’. The London and Liverpool speakers rated as likely, and the Glasgow and Belfast speakers as unlikely, to display morally bad behaviors.

However, while participants might assume someone is unlikely to commit a crime based on their accent, that assumption may not imply positive, prosocial behavior. For instance, the SSBE speaker, unlike the Liverpool speaker, was considered less likely to defend a victim of harassment.

“We didn’t see a strong link between how criminal someone’s voice sounded, and how kind or trustworthy they sounded,” said Paver. “Instead, there was a much more important link between how criminal a voice sounds and how working-class a voice sounds.”

Additionally, although the SSBE accent was rated less likely to have committed most crimes, that didn’t apply to the sexual assault. This could indicate that the image of people who commit sexual assault has moved away from historical assumptions implicating working-class men, unlike other types of crime.

Talking sense

The authors emphasized that more research, including more voices — particularly women’s voices — and investigating how accent strength affects assumptions, is needed to capture a fuller picture of accent biases. Additionally, they couldn’t rule out that vocal characteristics they couldn’t control for might have influenced their participants’ judgements.

“The team are currently drafting new guidelines for the implementation of voice line-ups,” said Paver. “We support the use of pre-testing to screen for voice bias. We also hope that anyone encountering voice evidence in the criminal justice system is warned against letting voice- or accent-based prejudice influence their decisions. These stereotypes could have real-life legal consequences.”

REPUBLISHING GUIDELINES: Open access and sharing research is part of Frontiers’ mission. Unless otherwise noted, you can republish articles posted in the Frontiers news site — as long as you include a link back to the original research. Selling the articles is not allowed.