- Science News

- Featured news

- Microalgae could be the future of sustainable superfood in a rapidly changing world, study finds

Microalgae could be the future of sustainable superfood in a rapidly changing world, study finds

By Peter Rejcek, science writer

The global population recently hit eight billion people. Yet climate change and human environmental impacts threaten our long-term food security. Researchers at the University of California, San Diego, recently published a scientific review demonstrating that microalgae and other microscopic, plant-like organisms could help feed the world’s growing population more sustainably than current agricultural systems.

Algae. It’s what’s for dinner.

This variation on the iconic US advertising slogan from the beef industry may sound funny, but it’s no joke that the current agriculture system is a major source of greenhouse gas emissions and environmental pollution. In turn, the climate crisis and ecosystem degradation threaten long-term food security for billions of people around the world.

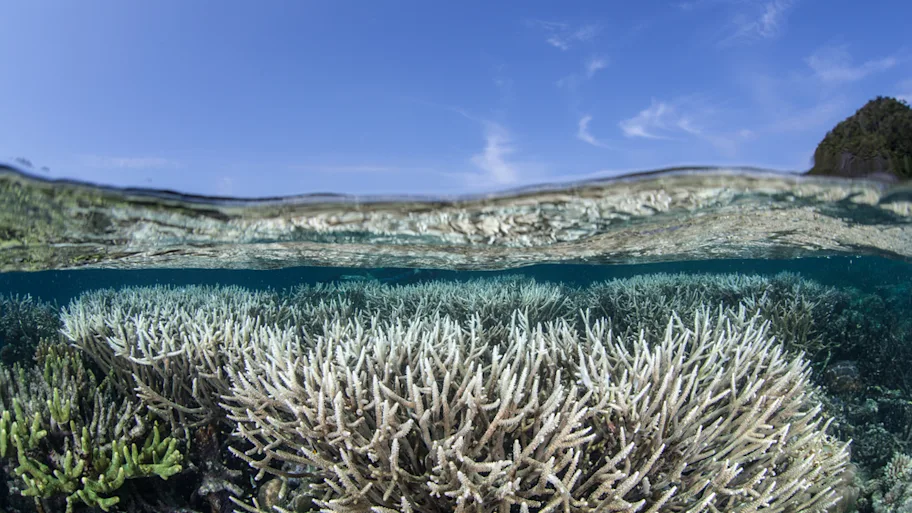

Researchers at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), believe algae could be a new kind of superfood thanks to its high protein and nutrition content. They make their case in a paper recently published in the journal Frontiers in Nutrition that examines the current scientific literature on microalgae, a catch-all term for the thousands of microscopic algal species and other photosynthetic organisms like cyanobacteria found in various aquatic environments.

A more efficient food source

The review highlights the current technologies for commercially developing and growing microalgae, as well as the scientific and economic challenges to scaling production. While long studied as a source of biofuel thanks to their high lipid or fat content, algae are also attracting interest from researchers because of their potential to be a more efficient food source.

“Many of us have known the potential of algae for food for years, and have been working on it as a food source, but now, with climate change, deforestation, and a population of eight billion people, most everyone realizes that the world simply has to become more efficient in protein production,” said co-author Dr Stephen Mayfield, a professor of biology at UCSD and director of the California Center for Algae Biotechnology.

For instance, a 2014 study cited in the current paper by Mayfield and his team found that algae can produce 167 times more useful biomass than corn annually while using the same amount of land. Other models predict that existing algae strains could potentially replace 25% of European protein consumption and 50% of the total vegetable oil consumption when grown on available land that is not currently used for traditional crops.

Download original article (pdf)

“The biggest advantage is the protein production per acre,” Mayfield noted. “Algae simply dwarf the current gold standard of soybean by at least 10 times, maybe 20 times, more production per acre.”

In addition, some algal species can be grown in brackish or salty water – and, in at least one case, wastewater from a dairy operation – meaning freshwater can be reserved for other needs. Nutritionally, many algal species are rich in vitamins, minerals and especially macronutrients essential to the human diet, such as amino acids and omega-3 fatty acids.

Creating the best algal strain for humans

Challenges still remain, starting with finding or developing algal strains that check all of the boxes: high biomass yields, high protein content, full nutrition profile, and the most efficient growing conditions in terms of land use, water requirements, and nutrient inputs.

In the paper, the UCSD authors describe the various scientific tools available to produce the most desirable traits for a commercially viable algal product. For example, one previously published experiment described enhancing astaxanthin, an antioxidant pigment that has been shown to have various health benefits, through targeted genetic mutations. Another mutagenic experiment was able to increase both biomass yield and protein content for a different algal strain, particularly when grown in a simple, low-cost sweet sorghum juice.

Mayfield said the most likely approaches for commercial development of a superior algal crop would involve a combination of traditional breeding with molecular engineering. “This is the way modern crops are being developed, so this is the way algae will be developed,” he said. “They are both plants – one terrestrial and one aquatic.”

Nutrition and yield aren’t the only considerations. Some tweaking of color, taste, and decreasing that characteristic fishy smell may be needed to convert some consumers. Other experiments have already demonstrated the ability to modify these organoleptic traits while boosting protein content in new strains of algae.

The need to feed a growing population

Indeed, the biggest challenge for commercial development, Mayfield added, isn’t necessarily scientific, technical or aesthetic. It’s the ability to scale production globally.

“You just can’t know all the challenges of going to world scale, until you do,” he said, “But the world has done this [with] smartphones, computers, photovoltaic panels, and electric cars – all of these had challenges, and we overcame them to take these ‘new’ technologies to world scale, so we know we can do it with algae.”

Mayfield said the need for alternative food systems has never been more urgent, as the human population swells, pushing resources and systems to the breaking point. “The only way to avoid a really bleak future is to start transitioning now to a much more sustainable future, and algae as food is one of those transitions that we need to make,” he said.

REPUBLISHING GUIDELINES: Open access and sharing research is part of Frontiers’ mission. Unless otherwise noted, you can republish articles posted in the Frontiers news site — as long as you include a link back to the original research. Selling the articles is not allowed.