- Science news

- Featured news

- Molecular changes in white blood cells can help us diagnose ‘the bends’ earlier in divers

Molecular changes in white blood cells can help us diagnose ‘the bends’ earlier in divers

By Conn Hastings, science writer

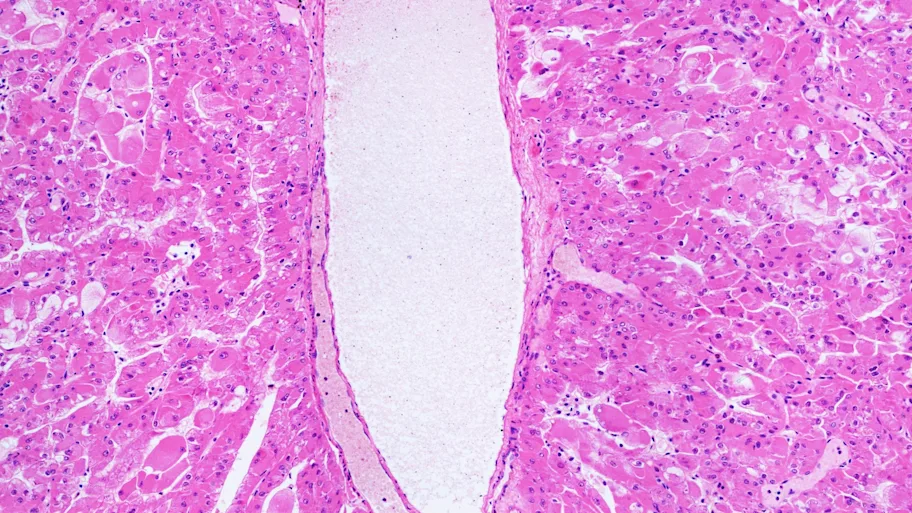

Image credit: unterwegs / Shutterstock.com

Despite knowing about decompression sickness – or ‘the bends’ – for more than a century, researchers are still mystified about how this condition occurs. A new study published by the open access journal Frontiers is the first to explore the genetic changes that occur in humans with the bends. It reveals that genes involved in white blood cell activation and inflammation are upregulated in divers with this condition. The results may pave the way for tests that allow doctors to diagnose decompression sickness more easily.

For more than a century, researchers have known about ‘the bends’, a serious condition affecting scuba divers. However, we still know relatively little about its physiological basis. Doctors do not yet have a definitive test for the bends, instead relying on symptoms to diagnose it.

A new study in Frontiers in Physiology is the first to investigate genetic changes in divers with this condition, finding that genes involved in inflammation and white blood cell activity are upregulated. The findings cast light on the processes underlying the bends, and may lead to biomarkers that will help doctors to diagnose the condition more precisely.

The bends, more formally known as decompression sickness, is a potentially lethal condition that can affect divers. Symptoms include joint pain, a skin rash, and visual disturbances. In some patients the condition can be severe, potentially leading to paralysis and death.

A paper published in 1908 correctly hypothesized that it involves bubbles of gas forming in the blood and tissue because of a decrease in pressure. However, researchers do not yet fully understand the precise mechanisms underlying the condition. Animal studies have suggested that inflammatory processes may have a role in decompression sickness, but no-one had studied this in humans.

► Read original article► Download original article (pdf)

Divers have developed methods to reduce the risk of the bends, including controlled ascents from the depths, and it is now relatively rare. However, for suspected cases, doctors have no way to test for the condition. Instead they rely on observing symptoms and seeing whether patients respond to hyperbaric oxygen therapy, which involves breathing oxygen at high pressures.

To investigate the basis of decompression sickness, the researchers behind this new study took blood samples from divers who had been diagnosed with decompression sickness and divers who had completed a dive without developing the condition. The researchers took blood samples at two distinct times: within eight hours of the divers emerging from the water, and 48 hours afterwards, when the divers with decompression sickness had undergone hyperbaric oxygen treatment. They performed RNA sequencing analysis to measure gene expression changes in white blood cells.

Interesting discovery

“We showed that decompression sickness activates genes involved in white blood cell activity, inflammation and the generation of inflammatory proteins called cytokines,” explains Dr Nikolai Pace of the University of Malta, a researcher involved in the study. “Basically, decompression sickness activates some of the most primitive body defense mechanisms that are carried out by certain white blood cells.”

Interestingly, these genetic changes had diminished in samples taken at 48 hours after the dive, after the patients had been treated with hyperbaric oxygen therapy. The findings provide a first step towards potentially developing a diagnostic test for decompression sickness, and may also reveal new treatment targets.

“We hope that our findings can aid the development of a blood-based biomarker test for human decompression sickness that can facilitate diagnosis or monitoring of treatment response,” says Prof Ingrid Eftedal of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, who was also involved in the project. “This will require further evaluation and replication in larger groups of patients.”

REPUBLISHING GUIDELINES: Open access and sharing research is part of Frontiers’ mission. Unless otherwise noted, you can republish articles posted in the Frontiers news site — as long as you include a link back to the original research. Selling the articles is not allowed.