- Science News

- Neuroscience

- Setting free the words trapped in our heads

Setting free the words trapped in our heads

By Mônica Favre, Ph.D., Frontiers Science Writer

Neuroscientists are on their way to turn a person’s thoughts into speech producible by a device, to help victims of stroke and others with speech paralysis to communicate with their loved ones.

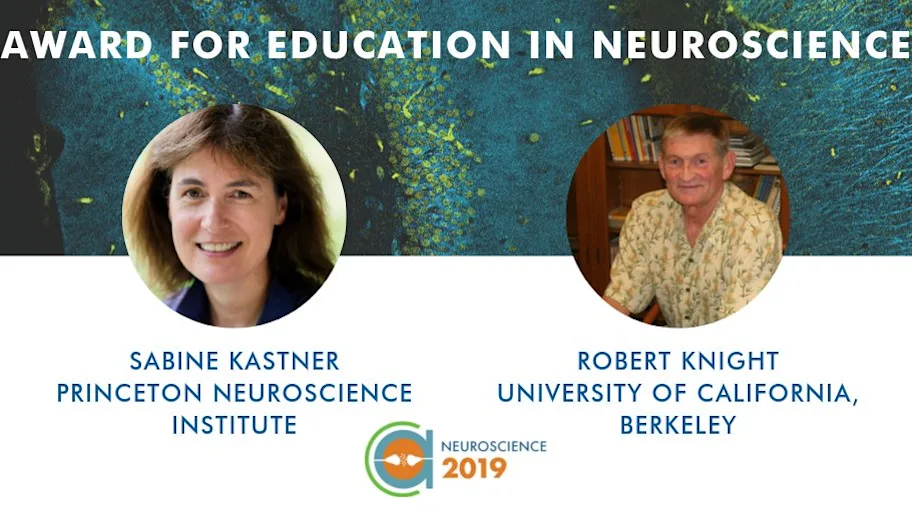

Professor Robert T. Knight, M.D., and his team at UC Berkeley are working on finding a way to decode speech imagined in the human brain. “We learned that hearing words, speaking out loud or imagining words involves mechanisms and brain areas that overlap. Now, the challenge is to reproduce comprehensible speech from direct brain recordings done while a person imagines a word they would like to say,” said Knight, who is also the Founding Editor of Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.

Knight says the goal of the device is to help people affected by motor disease, such as paralysis and Lou Gehrig’s Disease. “There are many neurological disorders that limit speech despite patients being fully aware of what they want to say,” Knight said. “We want to develop an implantable device that decodes the signals that occur in the brain when we think about a word, then turn these signals into a sound file that can be reproduced by a speech device.”

Such a novel device would communicate people’s intended thoughts via an electronic speaker or writing device, but the team still has a lot more research to conduct. They have been able to reproduce a word a person has just heard on a machine, by monitoring temporal lobe activity in a neurosurgical setting. Using high density electrodes positioned on the surface of the language areas of the brain of awake patients, they monitored the pattern of electrical responses of brain cells during perceived speech. The scientists then created a computational model that could match spoken sounds to these signals.

“We recorded electrical signals directly from the human language areas when a person heard words. We then decoded these electrical signals and were able to turn them into sound files that reflected what the person heard, with remarkable accuracy,” Knight explained.

Remarkably, the team was then able to decode speech when a person thinks of a specific word, from direct brain recordings. “The new techniques and mathematical processing of the brain signals got us closer to the details we need to extract the signals that are relevant for reproducing speech,” he said.

The researchers took a clever approach to overcome some important limitations by accounting for example, for the natural differences in sound timing when one is producing the same word twice, such as when thinking of the word then by uttering it. “We applied a temporal realignment procedure that improved our accuracy in classifying words that are spoken or imagined,” Knight explained.

The team’s approach is based on evidence that the brain evolved to sense the physical properties of the sounds produced by human voice, and then process them into meaningful elements of language, such as words, despite their high variability. “Our work showed us it is possible to capture the brain signals that represent an intended word,” he said.

Such substantial progress brings the team closer to building an effective prosthetic device, but the work must continue. “Better understanding of language organization and better recording devices will allow us to achieve useful implantable, wireless and battery-powered speech prosthesis,” said Knight.

So far, the work is based on rare data collected from patients that have been scheduled for neurosurgery for a non-related reason, such as to treat epilepsy. “Our ultimate goal is to create a small device that can be used in everyday life,” he said.

Further author biography and related research articles available via Loop